Research Paper: A step-by-step guide: 9. Writing Your Research Paper

- 1. Getting Started

- 2. Topic Ideas

- 3. Thesis Statement & Outline

- 4. Appropriate Sources

- 5. Search Techniques

- 6. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- 7. Evaluating Sources

- 8. Citations & Plagiarism

- 9. Writing Your Research Paper

From draft to finish

Writing your paper.

Often the actual writing is the hardest part of a research paper. How do you put all of your ideas together in a cohesive and understandable fashion? Hopefully this guide has helped lead you to this point, but if you need help, go back and review the steps you may need more help with.

You should now have the following items that will help you start your paper:

- Notes and a list of references from valid and reliable sources. When you create your list of works cited, you will only need to include the citations for the sources you refer to in your paper.

- An outline to guide you through your paper with main points and supporting evidence.

- A start on a thesis statement. You may find that your original idea isn’t supported by the research, or your thesis may evolve and change as you write. Revisiting your thesis throughout the research process is normal and a good idea.

Reviewing what makes a good research paper will help keep you on track as you write your paper. Here are the main points from step one of this guide:

- A strong and focused thesis statement

- Logically organized arguments and main points

- Each main point is supported by persuasive facts and examples

- Opposing viewpoints are included and rebutted, showing why the author's argument is more valid

- The paper shows the author's understanding of the topic and the material

- The work is original, not plagiarized

- Every source is correctly documented and credited in a recognized citation style

- The paper is written in clear language in a style suitable for college research

Finishing Touches and Final Draft First drafts can be messy and that is ok. Revising and editing your paper may take as much time, or longer, than writing the first draft. Here are some tips to help you through the process.

- Take a break. Hopefully you gave yourself plenty of time to work on your paper and are not rushed to finish. Taking a break will clear your head, focusing your attention on sections of your paper that might need revision.

- Double check the facts and numbers. Add supporting arguments as needed.

- Check for grammatical and spelling errors. Omit needless words and repetitious ideas.

- Check your citations (in-text citation and reference list) and paper format (header, page number, margins, etc.) to make sure sources are properly cited and the format is correct.

- Ask someone to read over your paper as they may be able to spot the mistakes you overlooked.

- Another way to check for mistakes, omissions, or awkward word construction is to read your paper out loud to yourself.

Tips to Help You Start Writing

To see some quick tips to help you write your paper, watch the following short video:

Need More Help?

Get your paper and citations checked at the Center for Academic Success (CAS).

- CAS Tutoring

- NetTutor You can access 24/7 online tutoring through Canvas.

- << Previous: 8. Citations & Plagiarism

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2023 12:12 PM

- URL: https://butte.libguides.com/ResearchPaper

The Secret(s) to Getting Through Long Papers

By Sophie, a Writing Center Coach

It’s the beginning of the semester—meaning, as a graduate student, it’s time for me to get back into the groove of planning and writing long papers. For me, the hardest part of approaching a paper is coming up with a topic that will stay interesting to me throughout the research and writing process. A good example of this is from the end of last semester, when I found myself dreading the final paper for my archives class. We covered so many interesting topics in the class, it was hard to decide which one to choose.

In my experience, a bad topic can make the writing process feel infinitely longer and more stressful. As I thought about my archives paper, I worried about finding something that I could focus on for 12 pages. So many of the topics in my class felt interwoven, and I was afraid it would be hard to pick out one thread. If I try to start a long paper without planning, I’ll end up staring at the same sentence or paragraph for hours, trying to figure out what I could possibly say next.

So, when I finally had to commit to a topic, I decided to break down the process into a few fun steps. Dividing it up helped take away some of my worries and made the process easier because I only had to do one step at a time. Here’s how I got started:

1) Create a real brainstorming session

First, I decided to meet up with a few of my friends who were also in the class. We went to a coffee shop we all like, and we brought our notes and readings from the class. None of us had a concrete idea about what to write; we just wanted to throw some possibilities out to see how other people would react to them.

We started by talking about some of the things we found funny or interesting in previous class discussions. As we talked, we found natural points of disagreement and interest. I took notes about points that stuck out to me. At the end of the conversation, I had a document full of questions and arguments that I wanted to explore further.

My friends also thought of topics, but they arrived at their ideas in different ways. One of my friends kept coming back to a short paper she had already written, and by talking about it, she discovered that she had much more to say. Another friend talked about something that he felt was conspicuously missing from our class discussions, so he decided that this paper would be a good opportunity to learn more.

All three of us came out of the session with inspiration and initial feedback. This step reminded me of the value of talking through my ideas, especially since my peers could push me to think more deeply about particular questions. Plus, connecting with my classmates through discussion helped me get excited about writing.

Alternatively, I know that, for some people, meeting with friends isn’t always effective; there are also other ways to brainstorm. Sometimes, it helps to talk to someone who doesn’t know about the class or topic—like a Writing Center coach ! For others, the note-taking part could be like having a conversation with yourself, which might be all you need. The Writing and Learning Centers also have some great tools for brainstorming if you prefer to work independently.

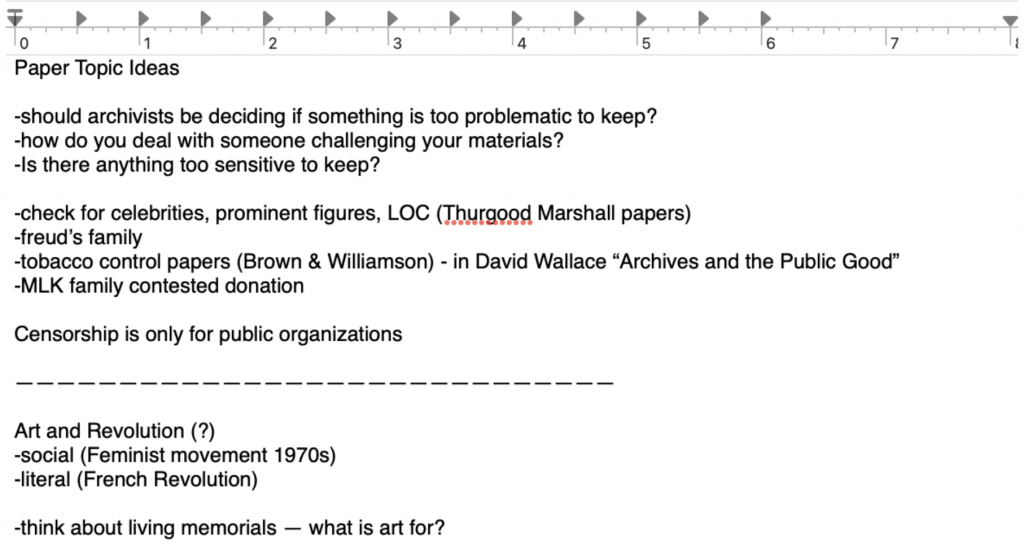

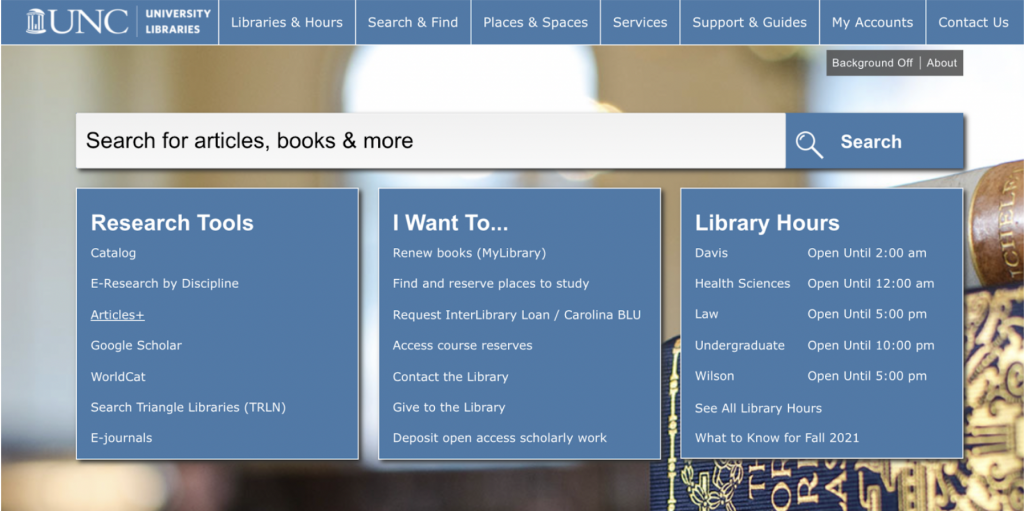

2) Conduct some initial research

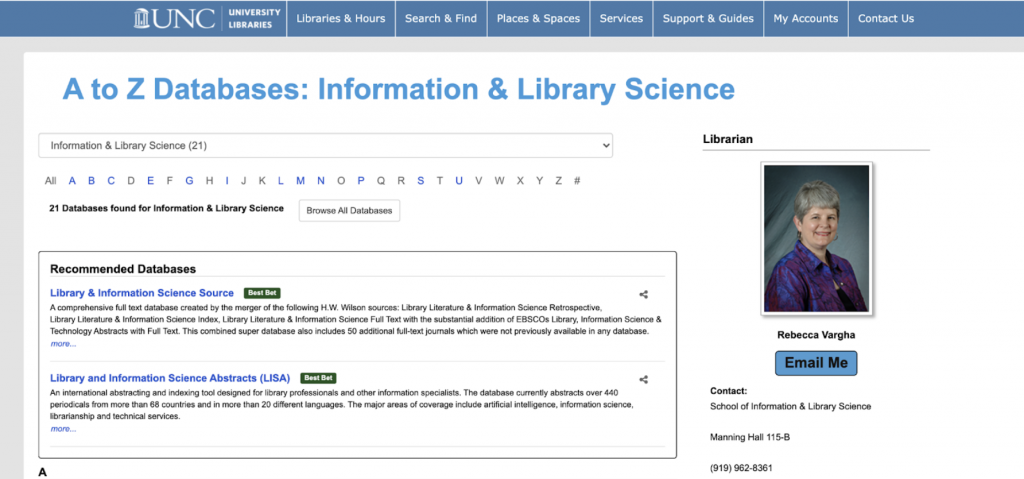

Once I had the beginnings of an idea, I decided to look for sources that could help me narrow my topic. The first place I go to find scholarly articles is the UNC Libraries’ page with “Resource Tools.” At this phase, I like to do keyword searches with Articles+. When you open the advanced search options, you can limit your results to be really specific by choosing a discipline, language, date the material was published, and whether the source needs to be scholarly/peer reviewed. In this case, I used “AND” to limit my results to articles with all of my desired keywords, like: “Sexual material” AND “Archives.” There’s another great article that explains the logic behind this kind of search, which uses Boolean logic.

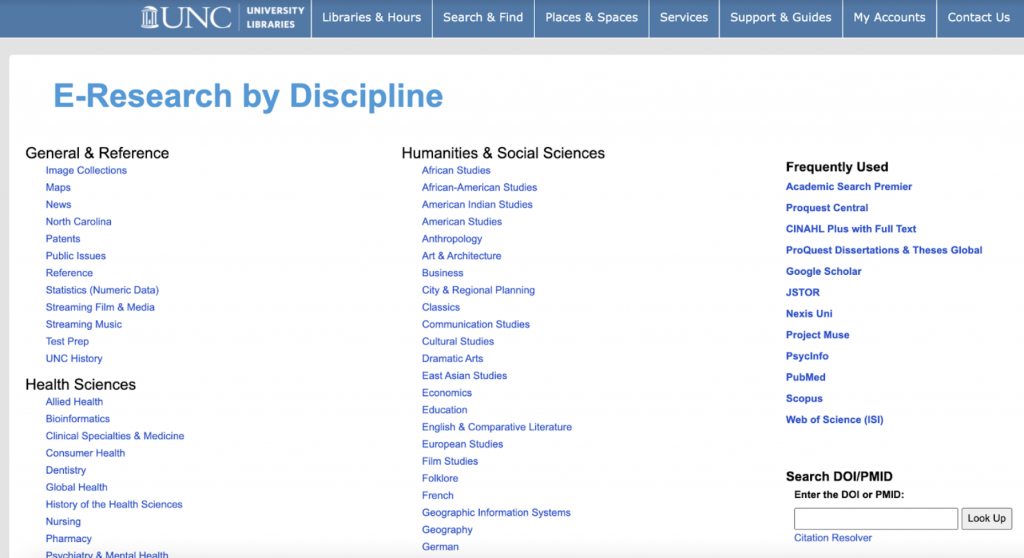

After I’ve combed through relevant results for one search, I’ll usually adjust my keywords to see if anything new pops up. I’ll also see if the best articles (the ones that feel most related to my topic) have been cited by anyone else and whether those articles have something to offer me. I also repeat this process with Google Scholar and with the “E-research by Discipline” option, which will lead me to specific databases for my field.

In this case, I used the Information and Library Science option, which took me to the best databases for journals in my discipline. Searching within a discipline allows me to think more carefully about my keywords; I might not have to include “archives,” or “libraries,” for example, because many of the articles are already about archives.

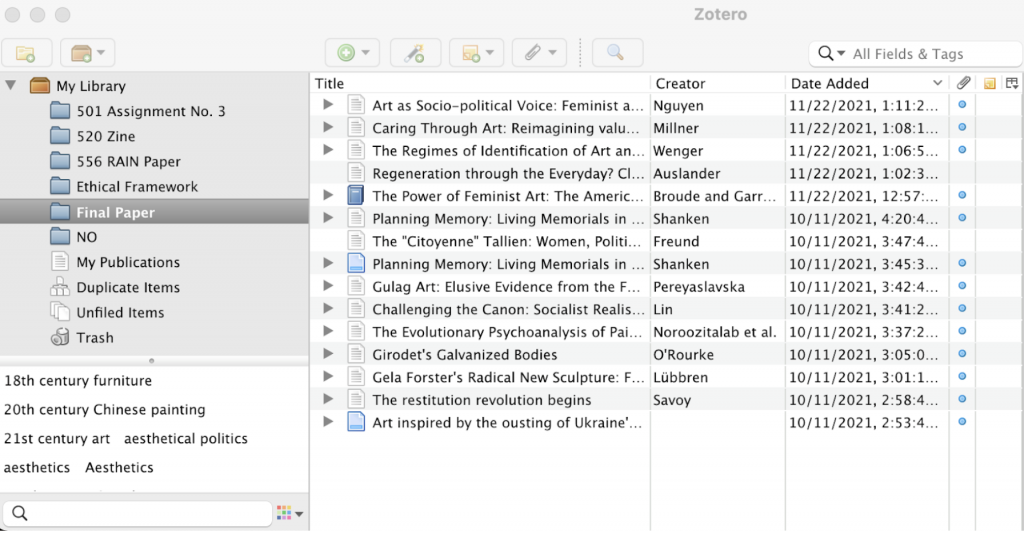

As I’m going along, I like to save any articles that I find in Zotero, a citation manager that I downloaded from the library’s website. Within Zotero, I make a folder for the assignment (“Final Paper”), and it automatically saves all the information I need to quickly go back to the article if I need it. (Note: I first learned about using Zotero from a helpful university librarian, so if you’re new to citation managers, it might be helpful to have a librarian give you a tutorial. You can also read another blog article on using Zotero .)

At the end of this process, I usually have a file full of “maybe” sources that I could come back to later. This helps give me an idea of what people have already said about this topic and where I might be able to add to the conversation.

3) Meet with your professor

After I came up with an idea and did some preliminary research, I thought it would be a good idea to check in with my professor during office hours. Since my professor is an expert in the field, I knew she would have a better sense of the context surrounding my research question.

(Note: Sometimes I like to go to office hours before I do any research; getting some expertise at the beginning can make the search process even faster. In this case, my professor encouraged us to find what we could before checking in with her.)

Before the meeting, I read through the abstracts of the sources I had already found in my preliminary research (those were saved in my Zotero library). Based on those, I wrote down some questions that I had about the topic. I met with my professor for about 15 minutes, and in that time, I pitched my question and told her what I had already found. She was able to direct me to some additional books and cases to look at, and I wrote those down to research later.

My professor also encouraged me to post my topic in our class’ Sakai forum. She created a discussion page specifically for final topic ideas so that my other classmates could provide feedback. Often, she said, students with similar topics will find sources that are helpful to each other, so the forum is a good place to share resources. I left the meeting with a strong sense of direction of what I needed to begin the actual writing.

After going through these steps, I felt like I had a good idea of what I wanted to write about and some evidence that could support my argument. Still, because it was such a long paper, I felt like I needed help to get started on the outline and the actual writing process. So, I decided to make a Writing Center Appointment to get my ideas in order and to make a plan for finishing the paper on time. Again, since I’m a person who likes to talk through my ideas, it was helpful to hear another person’s reaction to my topic so far. It also gave me a self-imposed deadline to complete these initial steps.

Breaking down the first few steps of writing my research paper helped me think of it as a list of small tasks to check off instead of one giant, frustrating project. It felt good to accomplish little things that I knew would add up to finishing the whole thing. This process also led me to a topic that really excited and engaged me, so when it was time to do the final step (the actual writing), I was happy to get started.

This blog showcases the perspectives of UNC Chapel Hill community members learning and writing online. If you want to talk to a Writing and Learning Center coach about implementing strategies described in the blog, make an appointment with a writing coach , a peer tutor , or an academic coach today. Have an idea for a blog post about how you are learning and writing remotely? Contact us here .

- Student Notebook

The Difficulties of Scientific Writing

As an undergraduate, I typically spent one week or less on writing assignments, regardless of how much time my instructor gave me. It was my natural ability — or so I thought at the time — that made me adept at writing so well in such a short time. When I arrived at graduate school, I thought that my natural writing skills would help me rise to the challenge of scientific writing. The goal of this article is to suggest that natural writing skills get far too much credit in scientific writing. In other words, writing is hard for everyone. In what follows, I detail some of the struggles of my early scientific writing experience while offering valuable lessons that I found helpful.

Everyone Struggles

Writing a research manuscript is difficult on many levels. The structure of a scientific manuscript differs from undergraduate writing, and this structure takes time to learn. Beyond this, data analysis can be challenging, particularly when results between studies are slightly inconsistent or if your current results show patterns that differ from patterns reported in the literature. Citing the work of others is also a challenge; knowing which articles are the most appropriate to reference in your given field requires experience. Finally, identifying your unique contribution to the literature can be challenging given all the previous research likely done on topics related to your manuscript. In light of all these considerations, it is easy for graduate students to feel overwhelmed, under-qualified, and in need of an advisor.

Every graduate student battles with these writing challenges, and others have written at length about ways to improve (e.g., Roediger, 2007). In my own experience, I have taken the behaviorist approach of B. F. Skinner (1954). For example, I tend to write in the same place and at the same time every day of each week. In Skinner’s language, the time and context reinforces the writing behavior. I find that being in a writing frame of mind helps me rise to the challenge and minimizes long spells spent staring at a blinking cursor. Taking a second lesson from behaviorism, the rats in Skinner’s experiments developed associations between behaviors and rewards after many consecutive trials. In writing, my greatest improvements have come from practice and rehearsal, not epiphany or revelation.

Embrace Criticism

Science improves through critical review, but even knowing that, I could not help but take some of the criticism I have received personally. Given the time spent on a research project from start to finish, taking critical comments personally is a natural reaction but not a helpful one. Criticism is so important for improving one’s writing, and there are many opportunities to seek out reviews from peers. I have relied on lab meetings to solicit comments from my fellow graduate students for manuscripts I am preparing. In addition to these meetings, I joined a writing group with several fellow students to continue receiving critical reviews of my writing. I also enrolled (twice) in a graduate-level writing course taught by a psychology professor. The students enrolled in this course provided feedback that helped me improve my arguments and develop a writing style based on techniques that worked for me. Any criticism, especially that which is directed at your research, stings. What helped me was getting used to the notion that criticism helps build a stronger manuscript.

Reviews Do Not Determine Writing Success

Having manuscripts rejected from journals remains a painful experience for me. At my most unhappy moments, I think about all the work that went into the paper and all the time spent writing it, ultimately to receive a rejection letter boiled down to three, two, or even one main problem with the paper. Although I have yet to learn how to be unaffected by rejections from journal editors, I have decided instead to celebrate the submission of a manuscript to journals. Submitting an article for review means that you have reached a point where you and your colleagues believe the manuscript makes a contribution to psychological science, and that is an accomplishment worth celebrating. It is important to celebrate one’s writing independent of reviewer critiques. I find that this celebration takes some of the sting off of the inevitable negative reviews.

Enjoy Writing

One of the faculty members in our department often says that “words are your ambassadors.” Although I am unsure about the origins of this statement, its message is clear: One impacts the field of psychology through writing. The purpose of research is to enhance our understanding of the social world through communicating ideas and discoveries. Writing is at the core of any research field, and as such, it helps to enjoy it. As others have noted (Preacher, 2003), writing should be fun for you, and if it is not, then try and make it more bearable. I relish certain parts of writing, such as formulating ideas and framing research implications. These portions help me get through the tedious bits (for me, the methods section).

In my time as a graduate student, I have come to the revelation that writing is hard for everyone. Knowing this, I hope that, as a researcher/writer, you will be equal parts patient with yourself and dedicated to your improvement as you continue to hone your writing skills.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Author

Michael W. Kraus is a social-personality PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley, studying the dynamics of social class and power, transference and close relationships, and nonverbal styles of communication. E-mail: [email protected]

Student Notebook: Finding Your Path in Psychological Science

Feeling unsure or overwhelmed as an early-career psychology student? Second-year graduate student Mariel Barnett shares advice to quell uncertainties.

Student Notebook: Doing Research With Your Community, for Your Community

Scientific findings can be difficult to apply to real-life scenarios. Fifth-year clinical psychology student Gabrielle Lynch gives advice on working with communities, building relationships, and overcoming research hurdles.

Student Notebook: Tips for Navigating the Demands of Graduate School

Understanding the science of stress can help graduate students manage the uncertainties and demands they face, says PhD student Kyle LaFollette.

Privacy Overview

- How It Works

- Prices & Discounts

We Asked 10 College Students What the Most Difficult Part of Writing an Essay Is

Table of contents

Essay writing is an important part of academic life in college. Writing a good essay involves several steps that require a lot of effort, time, and focus. It's not surprising that writing essays isn't exactly something college students enjoy doing.

But what is the most difficult part of writing an essay? From battling writer's block and struggling with the research process to organizing thoughts and meeting word count requirements, the list is endless.

To better understand this common difficulty, we asked 10 college students with different academic backgrounds about the toughest parts of writing an essay.

1. Understanding the essay prompt and topic

One of the most difficult parts of essay writing is understanding the prompt and topic of the essay.

Ellen agrees as she says, “ The hardest part was always trying to grasp the essay topic. It felt like a puzzle I had to solve before even putting words on paper. Once I could truly understand what the question was asking, everything else fell into place. "

It requires analytical skills to comprehend what the task requires. Many students often fail at the first step of understanding the prompt and submit an irrelevant essay. This mostly happens during the last-minute rush .

Get inspired: View our expert-written samples

To overcome this challenge, it's necessary to read the prompt carefully and analyze it critically. Identify critical elements like the main topic, the purpose, and the intended audience.

Also, take note of other specifications like the essay length, citations, and formatting. If you still have a challenge understanding all the instructions, discuss it with your professor or classmates before writing your essay.

2. Brainstorming

Brainstorming is the process of generating ideas for an essay. This step can be challenging since it requires creativity and critical thinking. It often requires you to think outside the box and come up with fresh and original ideas.

“The initial brainstorming phase always gets me stuck and takes me the longest time. Sometimes my mind goes blank, and I struggle to come up with relevant and engaging points to support my thesis,” says Trevor.

To overcome this challenge, you can use different techniques like freewriting— writing without a prescribed structure in mind. This can help you capture your thoughts and ideas so you won’t experience writer’s block when you start writing.

3. Structuring the essay

Some students find it hard to create a structure that flows logically from the introduction to the conclusion while maintaining focus throughout the essay. This often results in an unorganized essay that’s difficult to follow.

“The hardest part for me is definitely figuring out how to structure the essay. I often find myself wondering how I should organize my thoughts in a logical and coherent manner. Once I find that sweet spot where my ideas flow smoothly from one section to another, I know the tough part is over,” says Miles.

To overcome this challenge, create an outline before you start writing the essay . Divide it into essential parts such as the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Ensure that each paragraph is concise and focuses on one specific idea.

This will help you logically organize your ideas and thoughts and help you produce a well-structured essay.

4. Research process

Research is another crucial stage in essay writing. It’s the process of gathering information and evidence to support the arguments made in the essay.

Students often find it challenging to conduct research, especially when limited by time or resources. It can also be hard to find credible and relevant sources , especially when dealing with a topic that has yet to be widely explored.

“I often find myself overwhelmed with sources, wondering which ones are reliable and relevant. It's a constant battle of sifting through articles, books, and websites, trying to extract the most valuable insights,” explains Hannah.

What’s the solution? Take it step by step – start by developing various research questions related to the essay topic. Once you have your research questions, identify relevant sources like academic journals, books, and online resources related to your research question.

Read through them carefully, take notes, and highlight important points you can use as evidence to support your arguments.

5. Writing the thesis statement

For Tereza, it’s the thesis statement. “Writing the thesis statement is like condensing all my thoughts and arguments into one concise and powerful sentence. It needs to set the tone for the entire paper, and I want it to be strong and captivating,” she says.

The thesis statement is the backbone of any essay. It’s a sentence that presents your argument and tells the reader what to expect in your essay. Writing a strong thesis statement can be challenging since you’re required to capture the essence of the whole essay in a single sentence.

To overcome this challenge, start by identifying the central theme of your essay. Then, craft a statement that directly relates to the theme but reflects your own point of view. Make it clear, concise, and specific to avoid confusion.

6. Starting the essay

Another challenging part of writing an essay is getting started from a blank page. Writer’s block can make it difficult to put your thoughts into words, and the pressure to create the perfect opening can overwhelm you.

“For me, it’s about actually getting started. It's like staring at a blank screen, feeling the pressure to come up with a captivating introduction that hooks the reader from the get-go. It’s terrifying!” exclaims Peter.

You can also try freewriting to create a rough draft of the introduction. Set a timer for 10 minutes and write anything that comes to your mind. Don't worry about grammar, spelling, or sentence structure. This will help you organize your thoughts and get started.

Another trick that helps is to start with the main points and write the introduction last. You’ll often have a clear idea of what to write in the introduction once you’ve discussed your main points.

If all else fails, you can turn to an essay writing service like Writers Per Hour. In addition to writing, our expert essay writers can help you with topic selection, research, and citing sources. We also share a plagiarism report for free to guarantee 100% original and high-quality essays.

7. Writing an impactful conclusion

While Peter struggles with the introduction, Alanna has trouble ending the essay.

“Writing the conclusion is like tying everything together with a powerful and thought-provoking ending. I often find myself wondering how I can summarize the pain points without sounding repetitive,” she says.

It can be challenging to find the right words to wrap up your essay. Many students dread writing the conclusion since they fear that they will repeat information or be too vague.

To overcome this challenge, review your introduction and pick the main points you made throughout your essay. Then, use those points to craft a powerful conclusion that embodies the essence of your essay.

A good conclusion will restate your thesis statement and summarize your main points. You can also use the conclusion to suggest further research or to offer your honest opinion on the topic.

8. Make essays original and interesting

Writing original and interesting essays is essential to stand out from the crowd. You want to avoid plagiarism and write in a unique voice. Being unique and standing out is a challenge that most students battle with.

“For me, it’s the pressure of making essays engaging and interesting to read. It’s a battle to find that unique angle or storytelling element that grabs the reader's interest,” says Tanay.

To overcome this challenge, choose a topic that interests you and brainstorm unique perspectives or angles.

You can make your essay original by adding stories, anecdotes, examples, and personal experiences to illustrate your points. You can also use active voice, imagery, and transitions to keep your reader's interest.

What is the longest part of an essay?

The longest part of an essay is typically the body. This is where you present your arguments and provide supporting evidence. Once you've got your arguments in place, the body should be fairly straightforward to write. The key is to ensure you only present information that supports your argument and does get sidetracked with unnecessary details.

What is the most difficult thing about essay writing?

For many students, the most difficult thing about writing is simply getting started. Overcoming writer's block can be the biggest hurdle when trying to write an essay. Sometimes, the best way to overcome this obstacle is to simply write anything that comes to mind without worrying about perfection. This can help get the creative juices flowing and often leads to breakthroughs.

9. Writing in an academic style

How does one write academically in a world full of slang and social-media lingo?

An academic essay requires you to write in formal language and present arguments in an objective and analytical style. You can use technical vocabulary and clear sentences and avoid contractions.

“I’m always questioning whether I’m using the right vocabulary, adhering to academic standards, and expressing my ideas clearly,” says Yohan.

Reading academic essays or research papers can help you get a more in-depth idea of how to write in an academic style.

You can also consult with your professor and read examples of high-quality academic writing online to get an idea of what academic writing looks like. When researching, use academic sources only from approved academic journals and avoid informal sources like Wikipedia.

10. Citing sources correctly

Giving credit to other authors for their work is important in an essay. However, citing sources can be difficult and time-consuming, especially since different disciplines may require different citation styles.

“All the writing aside, what really gets me when it comes to writing essays in colleges is citing sources. It's like trying to navigate through this maze of rules and formats, making sure I give credit where it's due,” adds Debbie.

To cite correctly, read the citation manual provided by your professor and identify the citation style required in your essay. You can also use online citation generators like EasyBib or Citation Machine to generate correctly formatted citations automatically.

There are several challenges involved in writing an essay, and what may look difficult to one student may be a walk in the park for another. This means there’s no one definite thing that’s difficult about writing an essay since it all depends on a student’s unique skills and abilities.

With consistent focus and practice, you can build your confidence and be able to ace any part of the essay writing process with less hassle! If you’re still struggling, don’t hesitate to buy an essay from Writers Per Hour so you can focus on other important tasks at hand!

Share this article

Achieve Academic Success with Expert Assistance!

Crafted from Scratch for You.

Ensuring Your Work’s Originality.

Transform Your Draft into Excellence.

Perfecting Your Paper’s Grammar, Style, and Format (APA, MLA, etc.).

Calculate the cost of your paper

Get ideas for your essay

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE : Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 11:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

June 19, 2013

What's So Hard about Research?

By Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters

This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

We are told that the students that we teach are “digital natives.” This term implies that from the time they were born, technology has played such a large part in students’ lives that they know no other way. Also, it has been noted that digital natives have an aptitude for technology that is significantly different from the older generations (who have been dubbed “digital immigrants”); the joke goes that if you give a digital native and a digital immigrant a new digital camera, the native will be taking pictures before the immigrant has finished reading page two of the manual. The assumption is that this new generation is simply better than us at technology.

However, as we wrote about in another article for Scientific American , just because students are digital natives, does not mean that they have skills to figure out all technology, or to use technology in a purposeful way. We noticed that, though these digital natives have the world of information at their fingertips, for some reason they are often unable to take basic problem-solving skills and apply them to simple online research. They had no problem figuring out how to work the newest update to Facebook, but when asked to find out any information that required the smallest amount of critical thinking, students were hampered. The best example we have of this is when we asked students what the most important causes of the Revolutionary War were—we heard a student ask Siri: “What are the most important causes of the Revolutionary War?” When Siri did not know the answer, the student said, “I don’t know, I can’t find it.”

Students can find out basic names, dates, and facts through online research. If we ask them what year the Declaration of Independence was signed, they will Google that exact question, and most of the time, produce the right answer. But when asked to research a question that does not have one “right” answer, the room quickly dissolves into a chorus of “I don’t get it” and “I need help” and “I can’t find it.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In this article we will attempt to answer this question that we have posed and discussed often here at Scientific American:

What about online research is challenging to students?

Through observation of our students, we have come up with five hypotheses as to why this may be:

· Students today are accustomed to instant gratification, and therefore can be overwhelmed by tasks that require time-consuming research.

There are very few things in life that our students have to wait for today. Information they need to know is posted instantly online, they can connect with their friends through social media without needing to wait for school the next day, and Googling a question will give them a quick answer to any fact they want to know. However, research isn’t actually easy--in fact, it’s quite deceptive how the Internet makes it seem easy. In reality, research requires students to read, interpret, and analyze new information, reshape their research question, and start again. This kind of sustained focus on a challenging task is very hard for most students to hold. Here is an exchange that exemplifies this facet of the issue:

Student: “I can’t find anything about the buildings of the South during Reconstruction.”

Teacher: “Ok, show me what sites you’ve used.”

(Student pulls up an article from the History Channel)

Teacher: “Well, I see a good starting place right here. It says that much of the South was destroyed during Sherman’s March to the Sea during the Civil War. Why don’t you find out what areas his march destroyed, and then look up those cities to see what kind of destruction they faced?”

Student: (while pouting and walking back to his desk) “But that’s going to take forever !”

What the student meant to tell the teacher was, “ I can’t find anything easily about the buildings of the South during Reconstruction.” It isn’t true that, as a whole, these students have a difficult time with sustained attention. They do not stop researching and begin another activity because they got distracted; in our experience, they are more likely to spin themselves in circles making no progress for an entire class period because they do not want to go through a cognitive process that will take “forever.”

· When researching online, students unsuccessfully scan pages of text as opposed to reading those pages of text for comprehension. Therefore, they cannot tell whether or not the source they are looking at is applicable to their research question.

There are many techniques one can use to quickly locate information on an Internet page. For example, CTRL + F will bring up a “find” tool that will allow you to highlight all instances of a particular word or phrase on a page. Students use this tool quite frequently; when one student needed to find out what President Polk thought about U.S. expansion, she found an article about expansion, hit CTRL + F, and searched for “Polk.” All of the results on the page linked Polk to legislation that was passed, and land that was acquired during his term, but nowhere on the page could she find a sentence that said that President Polk thought that expansion was ________. Instead of reading the article and using inductive reasoning to figure out that President Polk was probably in favor of expansion, she told us that she couldn’t find the answer.

There are a few factors that we believe are at work here. It is faster to CRTL + F a keyword than it is to read an article, so perhaps some of hypothesis number 1 is at work, here: students want to take the fastest and quickest route. However, there are also issues of monitoring reading comprehension. The problem is not necessarily that the language of the article was too sophisticated for this student; the real problem is that she never stopped to ask herself the question, “Do I understand what this means?”

· When students are given a research prompt by their teacher, students often do not care enough about the topic to really persevere. Therefore, when they find that answers are not immediately apparent, they do not have the motivation necessary to fuel their sustained attention.

We have noticed that when students look up information we tell them to look up, they ask us many questions during a class period. Most are interested in making sure they have the “right answers”, and checking that their assignment is “long enough”. When students conduct research about a topic they have interest in, they have a much stronger sense of purpose. While some do still ask us questions in which they seek our approval, it is more often for approval about their thoughts pertaining to content than for approval of the length of their assignment. They seem to take more ownership of the material, and think about it on a higher level.

· Because there is so much information online, and not all of it is credible, Internet search results can be overwhelming to students. Therefore, the amount of information paralyzes rather than empowers students.

It seems counter-intuitive that a student could pull up 500,000 search results and still tell her teacher that she can’t find anything (just like flipping through a billion channels on cable, but finding that nothing is on)-- but students do often feel that way. The best way to illustrate this is to describe the difference in student responses when they were researching using a search engine other than Google.

Dulcinea Media came up with a search engine designed for students called SweetSearch . It works similarly to Google, in that there is a database of files that one can search by typing keywords into a search bar. What is different about SweetSearch is that the database only contains 30,000 documents, all of which have been previously vetted for academic reliability. For a particular project, the only Internet search engine we allowed the students to use was SweetSearch.

When they researched in class using Google, five to ten students per class period would say they were unable to find what they needed. When they researched in class using SweetSearch, there was not a single student who told us that they could not find any information about their topic. So whether students liked using SweetSearch or not, it is clear that it helped them be more successful when conducting their research.

· Developmentally, middle school students are just beginning to be able to think critically, but they seem programmed to look for “the” answer, and do not have a strong sense of self-efficacy when presented with open-ended questions.

Some of our unit assessments are structured in the style of Project Based Learning where students can present their findings in any form, as long as it answers the inquiry-based prompt. Many students were very uncomfortable with the idea that they would be making the decision about what form their project will take, and continually tried to get a stamp of approval. Questions like, “Do you think it will be okay if we make a movie?” Or “Will it be good if we make a poster?” were all answered with some version of, “It doesn’t matter what we think. What do you think?” We could see the frustration in their faces when they did not get the answer they wanted, but our goal here was for them to realize that their opinions were the ones that mattered.

Students also asked for their teachers’ opinions about their research findings. Students felt unsure about their authority, and wanted us to tell them that they had found the right answer. It takes the responsibility off of them; however, we wanted the students to take ownership of the information, and unless they were historically inaccurate in their findings (which almost never happened), we answered all of these questions in the same manner as the questions about their projects: “It doesn’t matter what I think. What do you think?”

Now that we know students struggle with research, now that we’ve discussed why that might be so, what steps can we take to help improve the situation? The next frontier for us will be to design curricular interventions that help students overcome some of these challenges they face, and to provide opportunities--like our Project Based Learning research unit assessment-- for students to research in more productive ways. SweetSearch and critical thinking are just the beginning. This question of research will only be more acute in the coming years as information in this age is becoming even more accessible and available to students. It is our job as their teachers to help students understand and be able to use this information that they discover.

- TMLC Support

- Training Calendar

What Makes Writing So Hard?

MAY 9, 2022

Many students struggle with writing—but what makes it so hard? And why do so many students hate to write? Writing is a task with a very high cognitive load. Giving students meaningful practice and clear structures for writing helps them move their thoughts out of their heads and onto the page.

Who Needs to Write? Everyone.

Based on the most recent NAEP writing assessment , only about one in four students at any grade level is proficient in writing—and that number hasn’t shifted meaningfully in decades. One in five students scored at the lowest proficiency level, Below Basic, at each tested grade level. Clearly, the traditional English Language Arts (ELA) programs used to teach writing are not, on their own, enough to move the needle for most students.

At the same time, writing is more important than ever in our knowledge economy. Writing is a “gatekeeper” skill for many higher-paying professions. Most white-collar and technical jobs require at least basic writing skills, whether for creating formal reports or simply communicating through email. In blue-collar and service jobs, people are often expected to be able to write clearly to communicate with customers. And writing will almost certainly be required to advance beyond the entry levels. In fact, a survey of business leaders put written communication skills at the top of the list of sought-after attributes.

Beyond the workforce, writing, like reading, is a skill that enables full participation in our modern world. Good writing skills allow people to participate in democracy by writing letters to the editor or expressing their views to a representative. Writing also allows people to participate in, rather than simply watch, all of the discourse and entertainment happening online. Writing can empower people to self-advocate in a variety of contexts, from healthcare to consumer interactions to legal proceedings. Writing skills are essential for anyone who wants a seat at the table in today’s complex political, consumer and personal realms.

The High Cognitive Load of Writing

By some metrics, today’s kids and teens are writing more than ever—that is, if you count texting, commenting on online content, and interacting in multiplayer games. But these interactions do not rise to the level of writing required to be successful on state assessments, college assignments, or workplace tasks. When students are faced with an authentic writing task—such as responding to a piece of text, writing a research paper, or developing an original narrative—the majority struggle.

In part, that may be because students don’t have much practice with formal writing, especially in extended form. There is some evidence that students today spend less time on writing than in the past, especially on argumentative writing and writing in the content areas. The Institute of Educational Sciences (IES) recommends that students have 60 minutes of writing time each school day , including a mix of direct writing instruction and writing assignments that span different purposes and content areas. However, only about 25% of middle schoolers and 30% of high schoolers meet the standard, and many students are only spending about 15 minutes each day on writing.

But even with ample time and instruction, writing is hard —in fact, it is arguably the hardest thing we ask our students to do. Natalie Wexler, the author of The Knowledge Gap , explains that writing has an even higher cognitive load than reading . That’s because, in addition to processing information, students also have to figure out how to get their own thoughts on the page.

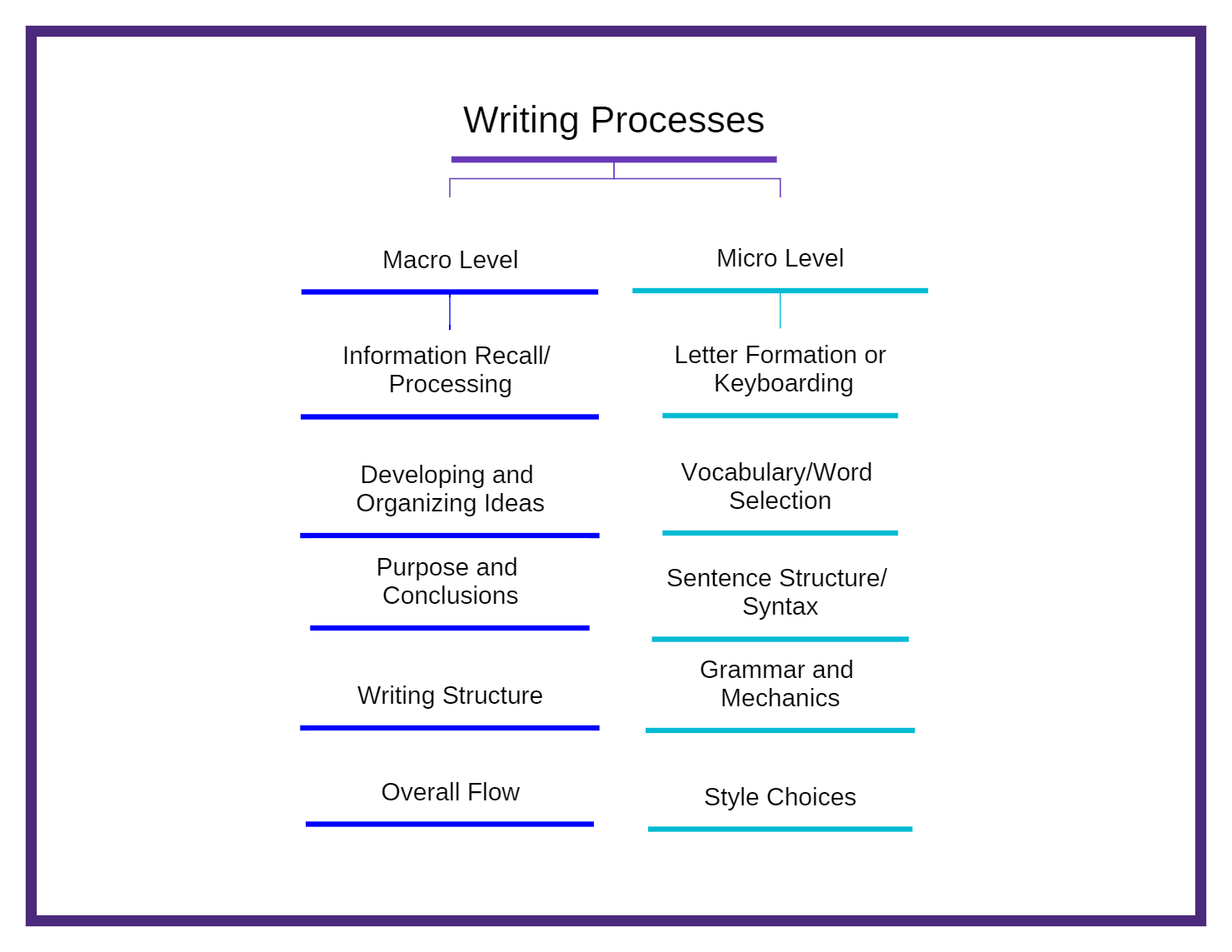

Writing is a highly complex skill that involves many discrete sub-skills at both the “macro” and “micro” levels.

- At the “macro” level, students have to figure out what to say: what is the point they are trying to make or the story they are trying to tell? What is the best way to organize their ideas and structure their piece? What are the big ideas and conclusions they want to get across? What kind of supporting evidence or details are needed?

- At the “micro” level, students must apply a myriad of foundational writing skills, from the motor skills involved with keyboarding or handwriting to decisions about word choice, syntax and grammar.

All of these writing processes are happening at the same time , adding to the overall cognitive load of the task. To lower the cognitive load, students must achieve proficiency and fluency at both the macro and micro levels. When students struggle with foundational skills such as letter formation and word selection, they may not have enough cognitive resources left to focus on the “big picture” of what they want to say. On the flip side, students who don’t know how to organize their ideas will not have much energy to focus on developing their writing style and editing and polishing their work.

The Hardest Part of Writing is Thinking

For most students, the hardest part of writing isn’t writing out individual words or forming a complete sentence. It is simply figuring out what to say . In fact, the Writing Center of Princeton says:

Writing is ninety-nine percent thinking, one percent writing. In other words, when you know what you want to say and how you want to say it, writing becomes easier and more successful.

Writing is, fundamentally, thinking made visible. If you can’t think, you can’t write. One of the best ways of lowering the cognitive load of writing is to give students a structure for organizing their ideas and thinking through the flow and structure of their piece.

That’s where Thinking Maps come in. Thinking Maps provide the structure for thinking through a writing task and organizing ideas prior to writing.

It starts with understanding the task itself. Students in a Thinking Maps school learn to use “signal words” that indicate what kind of thinking is required for a task. Then, they know what kind of Map to use to start their thinking process. For example, if the prompt asks them to explain the similarities and differences between two historical eras, they know immediately that this will be a “compare-and-contrast” task. The Double Bubble Map provides the structure they need to organize their ideas, whether from their existing knowledge, in-depth research, or a text provided with the prompt. Once they have fleshed out their ideas, students can use a writing Flow Map to develop their piece section by section. Having this kind of structure helps students move through the planning and organizing phases of writing more quickly so they have more time to spend on other parts of the writing process, including revising and editing. It also leads to clearer, more organized writing.

At Pace Brantley Preparatory, a Florida school serving students with learning disabilities in grades 1-12, adding some dedicated Thinking Maps planning time prior to writing led to better writing products on their benchmark assessments. Read the Pace Brantley story .

In our Write from the Beginning…and Beyond training , teachers learn how writing develops across the grade levels and how to use Thinking Maps to support student writing, including using the Maps to process thinking before writing and using the writing Flow Map to plan writing. Advanced training includes specific strategies for different genres, including Narrative, Expository/Informative, Argumentative, and Response to Text.

When students can think, they are ready to write. And when students can write, they are ready for anything.

Want to know more about Thinking Maps and writing?

- Download the recording: Building a Deep Structure for Writing

Continue Reading

April 15, 2024

Scientific thinking empowers students to ask good questions about the world around them, become flexible and adaptable problem solvers, and engage in effective decision making in a variety of domains. Thinking Maps can help teachers nurture a scientific mindset in students and support mastery of important STEM skills and content.

February 15, 2024

A majority of teachers believe that students are finally catching up from pandemic learning losses. But those gains are far from evenly distributed—and too many students were already behind before the pandemic. To close these achievement gaps, schools and districts need to focus on the underlying issue: the critical thinking gap.

January 16, 2024

Student engagement is a critical factor in the learning process and has a significant impact on educational outcomes. Thinking Maps enhance engagement by encouraging active participation in the learning process, facilitating collaboration, and providing students with structure and support for academic success.

November 15, 2023

Project-based learning (PBL) immerses students in engaging, real-world challenges and problems. Thinking Maps can give students a framework for thinking, planning and organizing their ideas in the PBL classroom.

Advertisement

Supported by

What Is the Hardest Part of Writing?

A cartoonist gets down to the crux of what makes putting pen to paper so difficult.

- Share full article

By Grant Snider

Grant Snider is a cartoonist, author and illustrator. His most recent book is “I Will Judge You by Your Bookshelf.”

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram , sign up for our newsletter or our literary calendar . And listen to us on the Book Review podcast .

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

“Real Americans,” a new novel by Rachel Khong , follows three generations of Chinese Americans as they all fight for self-determination in their own way .

“The Chocolate War,” published 50 years ago, became one of the most challenged books in the United States. Its author, Robert Cormier, spent years fighting attempts to ban it .

Joan Didion’s distinctive prose and sharp eye were tuned to an outsider’s frequency, telling us about ourselves in essays that are almost reflexively skeptical. Here are her essential works .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Kallestinova, E. D. (2011) How to write your first research paper, ... In your opinion, what is the easiest and hardest part in its writing in a scientific research or thesis?: ...

I think doing research and adhering to proper formatting is the most difficult part. However, today due to such tools as case converter and many other useful apps it became much easier. These lyrics from Chicago's 25 or 6 to 4 describe the hardest part for me: 36 votes, 45 comments.

Harvard College Writing Center 2 Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt When you receive a paper assignment, your first step should be to read the assignment prompt carefully to make sure you understand what you are being asked to do. Sometimes your assignment will be open-ended ("write a paper about anything in the course that interests you").

Take your time with the planning process. "It's worth consulting other researchers, doing a pilot study to test it, before you go out spending the time, money, and energy to do the big study," Crawford says. "Because once you begin the study, you can't stop.". Challenge: Assembling a Research Team.

Writing Your Paper. Often the actual writing is the hardest part of a research paper. How do you put all of your ideas together in a cohesive and understandable fashion? Hopefully this guide has helped lead you to this point, but if you need help, go back and review the steps you may need more help with.

It's the beginning of the semester—meaning, as a graduate student, it's time for me to get back into the groove of planning and writing long papers. For me, the hardest part of approaching a paper is coming up with a topic that will stay interesting to me throughout the research and writing process. A good example of this is from the end of last semester, when I found myself dreading the ...

After you get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to, the process of real writing begins. Copy your outline into a separate file and expand on each of the points, adding data and elaborating on the details. When you create the first draft, do not succumb to the temptation of editing.

1. Lack of motivation or focus. A lot of hard work and patience are needed to write a research paper. It can be hard to stay motivated during the process, and many problems may arise. You might have trouble focusing on the task, not have enough time because of other commitments or distractions, put it off, worry about finding reliable sources ...

In other words, writing is hard for everyone. In what follows, I detail some of the struggles of my early scientific writing experience while offering valuable lessons that I found helpful. Everyone Struggles. Writing a research manuscript is difficult on many levels. The structure of a scientific manuscript differs from undergraduate writing ...

Create a research paper outline. Write a first draft of the research paper. Write the introduction. Write a compelling body of text. Write the conclusion. The second draft. The revision process. Research paper checklist. Free lecture slides.

Then, writing the paper and getting it ready for submission may take me 3 to 6 months. I like separating the writing into three phases. The results and the methods go first, as this is where I write what was done and how, and what the outcomes were. In a second phase, I tackle the introduction and refine the results section with input from my ...

1. Understanding the essay prompt and topic. One of the most difficult parts of essay writing is understanding the prompt and topic of the essay. Ellen agrees as she says, " The hardest part was always trying to grasp the essay topic. It felt like a puzzle I had to solve before even putting words on paper.

Abstract. Writing qualitative research is a complex activity. Yet there is relatively little research about novices' experiences in learning to write this genre. The purpose of this multiple case study is to explore the challenges students face when they first encounter the qualitative research paradigm. Drawing upon interviews with students ...

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly ...

What's So Hard about Research? By Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters on June 19, 2013. We are told that the students that we teach are "digital natives.". This term implies that from the time ...

The Hardest Part of Writing Is Restarting. By Rebecca Schuman. February 15, 2019. iStock. Editor's Note: This is the fourth in a new series, "Are You Writing?". Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part ...

Not a phd student, but have published papers. In my opinion, finding the balance between explaining too much and not explaining is the most difficult task. You have to make sure that you are giving enough details. But you also have to be sure that you are not writing so much that you are going off topic. 5.

According to Faryadi (2012), writing a conclusion is as difficult as writing the introduction; meanwhile, Holewa states that writing the conclusion is the hardest part of the writing process. As the last part of a research paper format, the conclusion is the point where the writer has already exhausted his or her intellectual resources ...

The Hardest Part of Writing is Thinking. For most students, the hardest part of writing isn't writing out individual words or forming a complete sentence. It is simply figuring out what to say. In fact, the Writing Center of Princeton says: Writing is ninety-nine percent thinking, one percent writing. In other words, when you know what you ...

Often, the hardest part about writing is organizing the content in a logical way. Depriving students of this struggle leads to cookie-cutter papers that nobody actually wants to read. ... If you must assign a research paper, write your requirements in a way that rewards unique arguments and doesn't allow students to use sources as a way to ...

The research abstract is a short summary of your completed research or project, or a specific development of practice that you would like to share with others. 2 The abstract needs to be coherent, concise, and understandable; this is usually the only part of the paper the reader can see when searching through electronic databases. In addition ...

What Is the Hardest Part of Writing? A cartoonist gets down to the crux of what makes putting pen to paper so difficult. Share full article. By Grant Snider. July 10, 2020. Image. Image. Image. Image.

Dissertation is the research paper submitted by the candidate aspiring for a doctorate in a particular field of study. It is an extensive… 2 min read · Oct 15, 2019