How to Write a Long Essay

How to Write a One Page Essay

Writing an essay as part of a school assignment or a project can be a very tedious task, especially if that essay needs to be long. Even the most confident writers may have no trouble writing a few pages for an assignment but may find it challenging to extend that word count as much as possible. If you're assigned a long essay for one of your classes, there's no reason to worry. With some useful tips at your disposal, you can stretch that essay out without making it sound repetitive or boring the reader with an influx of irrelevant information.

What Is a Long Essay?

A long essay is any essay that tends to be longer than three pages or 3,000 words or more. Of course, the definition of a long essay will differ from one classroom to another, depending on the age and level of the students. And even if you're a college student, you may have some professors who consider a five-page essay to be the average, while another teacher considers five pages to be too much. Therefore, it's important to check with your teacher, though they'll usually clarify this when giving the assignment.

Sometimes, the term "long" applies to how many pages, and sometimes it applies to how many paragraphs or words need to be in the essay. Again, this all depends on your teacher, your school's requirements and the nature of the assignment. Either way, hearing your teacher say that you must write a long essay for your next assignment can certainly cause a lot of stress. The good news is that writing a long essay can be much easier than writing a short essay, especially if you're given some meaningful advice.

Why Would You Be Required to Write a Long Essay?

There are many reasons why teachers would assign a long essay to their students. First of all, writing a long essay is an opportunity for a student to really put his or her writing skills to the test. By the time students get to college, they already have an idea as to how to write a decent paper, but perhaps it's within limits. College professors need to make sure that students are able to write well, because eventually, these students may need to write a thesis or dissertation, and there really is no longer essay than that.

So even though you may think of writing a long essay as a torturous assignment, it's actually a great opportunity to practice a very specific skill that will definitely come in handy in other areas of your life. And, if you build up the right mindset for yourself, writing that long essay shouldn't be any more difficult than any other assignment you've been required to complete.

What Is the Standard Essay Format?

There's a standard essay format understood by most English students around the world. This is how essay writing can be taught in a universal way so that students are successful at writing essays no matter where they're studying. A standard essay format typically includes an introduction, three body paragraphs and a conclusion. Of course, the older a student gets and the more experience they have in school, their essays will gradually get longer and will need to require more detail and features (for instance, citing sources) in order to meet the requirements set by the teacher.

When you need to write a long essay, you can and should still base your writing off of this standard essay format. The only difference is that instead of having three body paragraphs, you're going to have a lot more in order to reach the word count or page requirement that you need to meet. This isn't as hard as it sounds. Instead of squeezing your main idea into one paragraph, try to add more examples and details to make it longer. Also, try to think of other key points that support your essay's theme that might not be so obvious at first.

Start Ahead of Time

The best way to relieve the stress that comes with having to write a long essay is to start ahead of time. Too many college students (and high school students) wait until the last possible minute to write an essay. Though some students may certainly be able to get away with this, it'll be a lot harder when it comes to writing a longer essay. Therefore, make sure you give yourself plenty of time to complete the assignment. It may work better for some people to do a little bit each day until they reach their goal. For instance, if you're required to write 3,000 words for your long essay, then you may feel better writing just 500 words a day over a couple of days instead of trying to bang it all out at once.

How to Write a 3,000 Word Essay in a Day

Some students rather get the hard work out of the way, instead of letting it drag out over a week. Writing a long essay of 3,000 words can be done in a day if you just put your mind to it. Do the following:

- Don't schedule any other appointments or assignments for the day.

- Put away any potential distractions, like your phone or the TV.

- Stay off of social media.

- Work somewhere quiet, like the library or a calm cafe.

- Take breaks every few paragraphs.

- Set a timer for ten minutes and try to work the entire time without stopping.

Create Your Essay Structure

Once you've decided whether or not you're going to write the essay over a couple of days or in just one day, it's time to start writing the actual essay. Like with any writing assignment, the first thing you should do is create an outline and organize your overall essay structure. If you need to write around five pages, which makes sense for a long essay, then you should make an outline that will support that. Take a look at an essay format example to get an idea of how yours should be:

- Introduction (more than two paragraphs)

- A starter question (something for the reader to consider)

- Body "paragraph/idea" one (four paragraphs on average)

- Body "paragraph/idea" two (four paragraphs on average]

- Body "paragraph/idea" three (four paragraphs on average)

- A conclusion

If you're wondering how on earth you're going to create a body section that's four paragraphs long, try to think of one main idea and three examples that tie together with it. For instance, if your long essay is an argumentative piece about "The Importance of Waiting Until You're Financially Stable to Have Children" you can think of at least four key reasons why:

- You won't have to struggle to pay for their needs.

- You can give them more opportunities.

- You can travel as a family.

- You can put away money for their college tuition.

For the first idea, you can talk about this point in very general terms. Then, you can write three more paragraphs underneath that, with each paragraph discussing a specific example. The second paragraph, for example, can be about paying for things like diapers, clothes, formula, etc., and how much each item costs. The second example can be about paying for things when the child gets a little older, like their food, their school supplies, etc. Lastly, the third example (and the fourth paragraph in this section) can discuss paying for things that the child will need as a teenager, such as more clothes, sports uniforms, dental work, etc.

Did You Answer All the Questions?

After you feel like you've exhausted all examples, but you're still under word count or page count, go back and make sure you've answered all the questions. These questions may have been questions in the rubric or the writing prompt that your teacher provided, or they may be questions that you've thought of on your own. In fact, when you start thinking of what to write about, you should brainstorm some questions that a reader may want to find the answer to about the topic, and you should try to answer these throughout your essay. Creating more potential questions can help you reach your word count faster.

Can You Change Words?

If you're close to reaching your word count but you're still not quite there, then go back and see if you can change any of the language in your essay to make it longer. For example, if you have a lot of contractions in your paper (can't, won't, isn't, they're) go back and make them two words instead of contractions, and do this throughout the entire essay. This is a great solution because it won't take away from the readership of your essay, and while this won't extend the word count too much, it will definitely help a bit.

Think of Additional Details You Can Add

In addition to changing contractions, you can also think of other details you can add to elongate your essay. There are always more examples you can add or more information you can research that will not only resonate with the reader but increase your overall word count or page count.

For example, if you're talking about how parents who decide to have children once they're financially stable will have the opportunity to put more money toward their child's tuition, then you can go back and add plenty of detail supporting this argument. Did you give an example of how much tuition costs? Did you add details about what parents can do with the money if their children decide not to go to college? What about the different types of college funds that exist? These are all details you can add that will increase the length of your essay, while also adding value.

However, when you do this, keep in mind that you want to be very careful not to add too much "fluff." Fluff is when you add information or details that simply aren't valuable to the writing itself. It makes the reader (who in most cases is your teacher and the one grading the assignment) want to skim over your piece, and this can lead to him or her giving you a lower grade.

Edit, Edit, Edit

Last but not least, in order to write a long essay, you must have the capacity to edit your work. Editing not only helps to ensure your paper is long enough, reads well, and is free from grammatical errors, but it will also give you an opportunity to add in more information here and there. To edit, you should always read out loud to yourself, and take a break from your work, so you can revisit it with a fresh pair of eyes. You can easily check if you've reached the length requirements by clicking on "word count" or counting the number of pages yourself, though your document will reveal this as you scroll down.

Related Articles

How to Write an Advantages and Disadvantages Essay

How to Make an Essay Longer

How to Write an Essay Fast

Problems That Students Encounter With Essay Writing

How to Write a 3,000 Word Essay

Personal Statement for scholarship: How to Write One, How long Does ...

College Essay Ideas

10 Good Transitions for a Conclusion Paragraph

- Save the Student: How to Write a 3,000 Word Essay in a Day

- International Student: General Essay Writing Tips

- You may want to have a friend read through your essay. He may catch mistakes that you have missed.

Hana LaRock is a freelance content writer from New York, currently living in Mexico. Before becoming a writer, Hana worked as a teacher for several years in the U.S. and around the world. She has her teaching certification in Elementary Education and Special Education, as well as a TESOL certification. Please visit her website, www.hanalarockwriting.com, to learn more.

12 Essay Features: Read Me!

Things you should already know.

Here are a few key highlights that you have already read about, or should have. To make sure you have a solid foundation, you should review this chapter before every essay. You do not need to complete the activities in this chapter, they are meant as a refresher.

It’s important to remember that there are certain features that all of these styles or methods have in common:

- A clear thesis statement usually provided at the beginning of the essay

- Clear and logical transitions

- Focused body paragraphs with evidence and support

- Appropriate format and style if you use source material

- A conclusion that expands upon your thesis and summarizes evidence

- Clear writing that follows standard conventions for things like grammar , punctuation , and spelling.

Stating Your Thesis

Most traditional research essays will require some kind of explicitly stated thesis. This means you should state your thesis clearly and directly for your readers. A thesis is a statement of purpose, one to two sentences long, about your research, that is often presented at the beginning of your essay to prepare your audience for the content of your whole research paper. Your thesis is often presented at the end of your introductory paragraph or paragraphs.

Your thesis statement should state your topic and, in a persuasive research essay, state your assertion about that topic. You should avoid simply “announcing” your thesis and should work to make it engaging. A good thesis will answer the “so what?” question your audience might have about your research paper. A good thesis statement will tell your readers what your research paper will be about and, specifically, why it is important.

You should avoid thesis statements that simply announce your purpose. For example, in a research paper on health care reform, you should avoid a thesis statement like this:

Instead, a good thesis statement on health care reform in the United States would be more specific and make a point that will help establish a clear purpose and focus for your essay. It might look something like this:

Implying Your Thesis

If you’re unsure about whether you should use an explicit thesis or simply maintain a clear focus without an explicit thesis, be sure to ask your instructor. In English 101, you should use an explicit thesis statement to make it clear you know how to use one.

Placement of Thesis Statements

A thesis statement is usually the last sentence of the first paragraph of a paper. It is also customary to restate the main idea of your paper in the conclusion so that the paper leaves a clear impression on the reader.

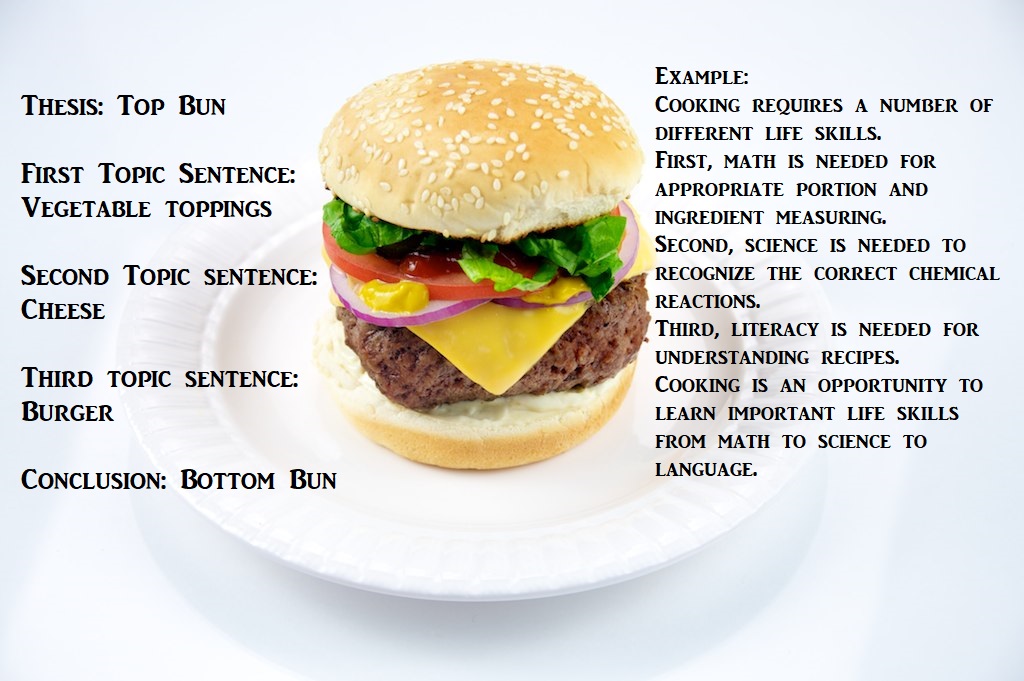

Topic Sentences

So, thesis statements tell us the goals of the entire writing assignment and topic sentences tell us the goal of a particular paragraph. Essentially, the CEO is the thesis statement and the topic sentences are the managers. Let’s use a quick cheeseburger method to see how topic sentences work:

Linking Paragraphs: Transitions

Transitions are words or phrases that indicate linkages in ideas. When writing, you need to lead your readers from one idea to the next, showing how those ideas are logically linked. Transition words and phrases help you keep your paragraphs and groups of paragraphs logically connected for a reader. Writers often check their transitions during the revising stage of the writing process.

Here are some example transition words to help as you transition both within paragraphs and from one paragraph to the next.

Paragraphing: MEAL Plan

When it’s time to draft your essay and bring your content together for your audience, you will be working to build strong paragraphs. Your paragraphs in a research paper will focus on presenting the information you found in your source material and commenting on or analyzing that information. It’s not enough to simply present the information in your body paragraphs and move on. You want to give that information a purpose and connect it to your main idea or thesis statement.

Duke University coined a term called the “MEAL Plan” that provides an effective structure for paragraphs in an academic research paper. Select the pluses to learn what each letter stands for.

Here are the same terms with examples:

MLA Formatting: The Basics

Papers constructed according to MLA guidelines should adhere to the following elements:

- Double-space all of the text of your paper, and use a clear font, such as Times New Roman or Courier 12-point font.

- Use one-inch margins on all sides, and indent the first line of a paragraph one half-inch from the left margin.

- List your name, your instructor’s name, the course, and the date in the upper left-hand corner of the first page. This is your heading . There is no cover page.

- Type a header in the upper right-hand corner with your last name, a space, and then a page number. Pages should be numbered consecutively with Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, etc.), one-half inch from the top and flush with the right margin.

- Provide in-text citations for all quoted, paraphrased, and summarized information in your paper.

- Include a Works Cited page at the end of your paper that gives full bibliographic information for each item cited in your paper.

- If you use endnotes, include them on a separate page before your Works Cited page

- Your Works Cited page at the end of your project should line up with the in-text citations in the body of your essay.

If you need more information, check the chapter on MLA Style.

Conclusions

A satisfying conclusion allows your reader to finish your paper with a clear understanding of the points you made and possibly even a new perspective on the topic.

Any single paper might have a number of conclusions, but as the writer, you must consider who the reader is and the conclusion you want them to reach. For example, is your reader relatively new to your topic? If so, you may want to restate your main points for emphasis as a way of starting the conclusion. (Don’t literally use the same sentence(s) as in your introduction but come up with a comparable way of restating your thesis.) You’ll want to smoothly conclude by showing the judgment you have reached is, in fact, reasonable.

Just restating your thesis isn’t enough. Ideally, you have just taken your reader through a strong, clear argument in which you have provided evidence for your perspective. You want to conclude by pointing out the importance or worthiness of your topic and argument. You could describe how the world would be different, or people’s lives changed if they ascribed to your perspective, plan, or idea.

You might also point out the limitations of the present understanding of your topic, suggest or recommend future action , study, or research that needs to be done.

If you have written a persuasive paper, hopefully, your readers will be convinced by what you have had to say!

20 Most Common Grammar Errors

The link below will take you outside of our book.

Thanks to some excellent research from Andrea Lunsford and her colleagues, every few years, we get a list of the “ 20 Most Common Errors ” beginning writers in the United States make. Every few years, Lunsford and her team of researchers examine thousands of student essays and survey hundreds of writing teachers in order to give us this list.

The good news is that most of the errors on this list are mistakes that we make when we are tired, in a hurry, and just not being good editors. So, they are easy fixes.

Once you finish reading through the 20 most common errors, you can come back here to complete the activity.

After completing this activity, you may download or print a completion report that summarizes your results.

Punctuation

Maybe you have heard the story about how punctuation saves lives. Clearly, there is a difference between

In addition to saving lives, using punctuation properly will help your writing be clean and clear and help you build your credibility as a writer.

The following link will provide you with an overview of the basic rules regarding punctuation and will give you a chance to practice using the information you have learned.

Putting It All Together

It is time to write your essay Keep this list of things to remember handy and put that paper together. You got this!

ATTRIBUTIONS

- Content Adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL). (2020). Excelsior College. Retrieved from https://owl.excelsior.edu/ licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License .

- Original Content by Christine Jones. (2021). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License .

English 101: Journey Into Open Copyright © 2021 by Christine Jones is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- If you are writing in a new discipline, you should always make sure to ask about conventions and expectations for introductions, just as you would for any other aspect of the essay. For example, while it may be acceptable to write a two-paragraph (or longer) introduction for your papers in some courses, instructors in other disciplines, such as those in some Government courses, may expect a shorter introduction that includes a preview of the argument that will follow.

- In some disciplines (Government, Economics, and others), it’s common to offer an overview in the introduction of what points you will make in your essay. In other disciplines, you will not be expected to provide this overview in your introduction.

- Avoid writing a very general opening sentence. While it may be true that “Since the dawn of time, people have been telling love stories,” it won’t help you explain what’s interesting about your topic.

- Avoid writing a “funnel” introduction in which you begin with a very broad statement about a topic and move to a narrow statement about that topic. Broad generalizations about a topic will not add to your readers’ understanding of your specific essay topic.

- Avoid beginning with a dictionary definition of a term or concept you will be writing about. If the concept is complicated or unfamiliar to your readers, you will need to define it in detail later in your essay. If it’s not complicated, you can assume your readers already know the definition.

- Avoid offering too much detail in your introduction that a reader could better understand later in the paper.

- picture_as_pdf Introductions

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Is a long essay always a good essay the effect of text length on writing assessment.

- 1 Department of Educational Research and Educational Psychology, Leibniz Institute for Science and Mathematics Education, Kiel, Germany

- 2 Institute for Psychology of Learning and Instruction, Kiel University, Kiel, Germany

- 3 School of Education, Institute of Secondary Education, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland, Brugg, Switzerland

The assessment of text quality is a transdisciplinary issue concerning the research areas of educational assessment, language technology, and classroom instruction. Text length has been found to strongly influence human judgment of text quality. The question of whether text length is a construct-relevant aspect of writing competence or a source of judgment bias has been discussed controversially. This paper used both a correlational and an experimental approach to investigate this question. Secondary analyses were performed on a large-scale dataset with highly trained raters, showing an effect of text length beyond language proficiency. Furthermore, an experimental study found that pre-service teachers tended to undervalue text length when compared to professional ratings. The findings are discussed with respect to the role of training and context in writing assessment.

Introduction

Judgments of students’ writing are influenced by a variety of text characteristics, including text length. The relationship between such (superficial) aspects of written responses and the assessment of text quality has been a controversial issue in different areas of educational research. Both in the area of educational measurement and of language technology, text length has been shown to strongly influence text ratings by trained human raters as well as computer algorithms used to score texts automatically ( Chodorow and Burstein, 2004 ; Powers, 2005 ; Kobrin et al., 2011 ; Guo et al., 2013 ). In the context of classroom language learning and instruction, studies have found effects of text length on teachers’ diagnostic judgments (e.g., grades; Marshall, 1967 ; Osnes, 1995 ; Birkel and Birkel, 2002 ; Pohlmann-Rother et al., 2016 ). In all these contexts, the underlying question is a similar one: Should text length be considered when judging students’ writing – or is it a source of judgment bias? The objective of this paper is to investigate to what degree text length is a construct-relevant aspect of writing competence, or to what extent it erroneously influences judgments.

Powers (2005) recommends both correlational and experimental approaches for establishing the relevance of response length in the evaluation of written responses: “the former for ruling out response length (and various other factors) as causes of response quality (by virtue of their lack of relationship) and the latter for establishing more definitive causal links” (p. 7). This paper draws on data from both recommended approaches: A correlational analysis of a large-scale dataset [MEWS; funded by the German Research Foundation (Grant Nr. CO 1513/12-1) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant Nr. 100019L_162675)] based on expert text quality ratings on the one hand, and an experimental study with untrained pre-service teachers on the other. It thereby incorporates the measurement perspective with the classroom perspective. In the past, (language) assessment research has been conducted within different disciplines that rarely acknowledged each other. While some assessment issues are relevant for standardized testing in large-scale contexts only, others pertain to research on teaching and classroom instruction as well. Even though their assessments may serve different functions (e.g., formative vs. summative or low vs. high stakes), teachers need to be able to assess students’ performance accurately, just as well as professional raters in standardized texts. Thus, combining these different disciplinary angles and looking at the issue of text length from a transdisciplinary perspective can be an advantage for all the disciplines involved. Overall, this paper aims to present a comprehensive picture of the role of essay length in human and automated essay scoring, which ultimately amounts to a discussion of the elusive “gold standard” in writing assessment.

Theoretical Background

Writing assessment is about identifying and evaluating features of a written response that indicate writing quality. Overall, previous research has demonstrated clear and consistent associations between linguistic features on the one hand, and writing quality and development on the other. In a recent literature review, Crossley (2020) showed that higher rated essays typically include more sophisticated lexical items, more complex syntactic features, and greater cohesion. Developing writers also show movements toward using more sophisticated words and more complex syntactic structures. The studies presented by Crossley (2020) provide strong indications that linguistic features in texts can afford important insights into writing quality and development. Whereas linguistic features are generally considered to be construct-relevant when it comes to assessing writing quality, there are other textual features whose relevance to the construct is debatable. The validity of the assessment of students’ competences is negatively affected by construct-irrelevant factors that influence judgments ( Rezaei and Lovorn, 2010 ). This holds true for professional raters in the context of large-scale standardized writing assessment as well as for teacher judgments in classroom writing assessment (both formative or summative). Assigning scores to students’ written responses is a challenging task as different text-inherent factors influence the accuracy of the raters’ or teachers’ judgments (e.g., handwriting, spelling: Graham et al., 2011 ; length, lexical diversity: Wolfe et al., 2016 ). Depending on the construct to be assessed, the influence of these aspects can be considered judgment bias. One of the most relevant and well-researched text-inherent factors influencing human judgments is text length. Crossley (2020) points out that his review does “not consider text length as a linguistic feature while acknowledging that text length is likely the strongest predictor of writing development and quality.” Multiple studies have found a positive relationship between text length and human ratings of text quality, even when controlling for language proficiency ( Chenoweth and Hayes, 2001 ; McCutchen et al., 2008 ; McNamara et al., 2015 ). It is still unclear, however, whether the relation between text length and human scores reflects a true relation between text length and text quality (appropriate heuristic assumption) or whether it stems from a bias in human judgments (judgment bias assumption). The former suggests that text length is a construct-relevant factor and that a certain length is needed to effectively develop a point of view on the issue presented in the essay prompt, and this is one of the aspects taken into account in the scoring ( Kobrin et al., 2007 ; Quinlan et al., 2009 ). The latter claims that text length is either completely or partly irrelevant to the construct of writing proficiency and that the strong effect it has on human judgment can be considered a bias ( Powers, 2005 ). In the context of large-scale writing assessment, prompt-based essay tasks are often used to measure students’ writing competence ( Guo et al., 2013 ). These essays are typically scored by professionally trained raters. These human ratings have been shown to be strongly correlated with essay length, even if this criterion is not represented in the assessment rubric ( Chodorow and Burstein, 2004 ; Kobrin et al., 2011 ). In a review of selected studies addressing the relation between length and quality of constructed responses, Powers (2005) showed that most studies found correlations within the range of r = 0.50 to r = 0.70. For example, he criticized the SAT essay for encouraging wordiness as longer essays tend to score higher. Kobrin et al. (2007) found the number of words to explain 39% of the variance in the SAT essay score. The authors argue that essay length is one of the aspects taken into account in the scoring as it takes a certain length to develop an argument. Similarly, Deane (2013) argues in favor of regarding writing fluency a construct-relevant factor (also see Shermis, 2014 ; McNamara et al., 2015 ). In an analytical rating of text quality, Hachmeister (2019) could showed that longer texts typically contain more cohesive devices, which has a positive impact on ratings of text quality. In the context of writing assessment in primary school, Pohlmann-Rother et al. (2016) found strong correlations between text length and holistic ratings of text quality ( r = 0.62) as well as the semantic-pragmatic analytical dimension ( r = 0.62). However, they found no meaningful relationship between text length and language mechanics (i.e., grammatical and orthographical correctness; r = 0.09).

Text length may be considered especially construct-relevant when it comes to writing in a foreign language. Because of the constraints of limited language knowledge, writing in a foreign language may be hampered because of the need to focus on language rather than content ( Weigle, 2003 ). Silva (1993) , in a review of differences between writing in a first and second language, found that writing in a second language tends to be “more constrained, more difficult, and less effective” (p. 668) than writing in a first language. The necessity of devoting cognitive resources to issues of language may mean that not as much attention can be given to higher order issues such as content or organization (for details of this debate, see Weigle, 2003 , p. 36 f.). In that context, the ability of writing longer texts may be legitimately considered as indicative of higher competence in a foreign language, making text length a viable factor of assessment. For example, Ruegg and Sugiyama (2010) showed that the main predictors of the content score in English foreign language essays were first, organization and second, essay length.

The relevance of this issue has further increased as systems of automated essay scoring (AES) have become more widely used in writing assessment. These systems offer a promising way to complement human ratings in judging text quality ( Deane, 2013 ). However, as the automated scoring algorithms are typically modeled after human ratings, they are also affected by human judgment bias. Moreover, it has been criticized that, at this point, automated scoring systems mainly count words when computing writing scores ( Perelman, 2014 ). Chodorow and Burstein (2004) , for example, showed that 53% of the variance in human ratings can be explained by automated scoring models that use only the number of words and the number of words squared as predictors. Ben-Simon and Bennett (2007) provided evidence from National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) writing test data that standard, statistically created e-rater models weighed essay length even more strongly than human raters (also see Perelman, 2014 ).

Bejar (2011) suggests that a possible tendency to reward longer texts could be minimized through the training of raters with responses at each score level that vary in length. However, Barkaoui (2010) and Attali (2016) both compared the holistic scoring of experienced vs. novice raters and – contrary to expectations – found that the correlation between essay length and scores was slightly stronger for the experienced group. Thus, the question of whether professional experience and training counteract or even reinforce the tendency to overvalue text length in scoring remains open.

Compared to the amount of research on the role of essay length in human and automated scoring in large-scale high-stakes contexts, little attention has been paid to the relation of text length and quality in formative or summative assessment by teachers. This is surprising considering the relevance of the issue for teachers’ professional competence: In order to assess the quality of students’ writing, teachers must either configure various aspects of text quality in a holistic assessment or hold them apart in an analytic assessment. Thus, they need to have a concept of writing quality appropriate for the task and they need to be aware of the construct-relevant and -irrelevant criteria (cf. the lens model; Brunswik, 1955 ). To our knowledge, only two studies have investigated the effect of text length on holistic teacher judgments, both of which found that longer texts receive higher grades. Birkel and Birkel (2002) found significant main effects of text length (long, medium, short) and spelling errors (many, few) on holistic teacher judgments. Osnes (1995) reported effects of handwriting quality and text length on grades.

Whereas research on the text length effect on classroom writing assessment is scarce, a considerable body of research has investigated how other text characteristics influence teachers’ assessment of student texts. It is well-demonstrated, for example, that pre-service and experienced teachers assign lower grades to essays containing mechanical errors ( Scannell and Marshall, 1966 ; Marshall, 1967 ; Cumming et al., 2002 ; Rezaei and Lovorn, 2010 ). Scannell and Marshall (1966) found that pre-service teachers’ judgments were affected by errors in punctuation, grammar and spelling, even though they were explicitly instructed to grade on content alone. More recently, Rezaei and Lovorn (2010) showed that high quality essays containing more structural, mechanical, spelling, and grammatical errors were assigned lower scores than texts without errors even in criteria relating solely to content. Teachers failed to distinguish between formal errors and the independent quality of content in a student essay. Similarly, Vögelin et al. (2018 , 2019) found that lexical features and spelling influenced not only holistic teacher judgments of students’ writing in English as a second or foreign language, but also their assessment of other analytical criteria (e.g., grammar). Even though these studies do not consider text length as a potential source of bias, they do show that construct-irrelevant aspects influence judgments of teachers.

This Research

Against this research background, it remains essential to investigate whether the relation between essay length and text quality represents a true relationship or a bias on the part of the rater or teacher ( Wolfe et al., 2016 ). First, findings of correlational studies can give us an indication of the effect of text length on human ratings above and beyond language proficiency variables. Second, going beyond correlational findings, there is a need for experimental research that examines essay responses on the same topic differing only in length in order to establish causal relationships ( Kobrin et al., 2007 ). The present research brings together both of these approaches.

This paper comprises two studies investigating the role of essay length in foreign language assessment using an interdisciplinary perspective including the fields of foreign language education, computer linguistics, educational research, and psychometrics. Study 1 presents a secondary analysis of a large-scale dataset with N = 2,722 upper secondary school students in Germany and Switzerland who wrote essays in response to “independent writing” prompts of the internet-based Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL iBT). It investigates the question of how several indicators of students’ English proficiency (English grade, reading and listening comprehension, self-concept) are related to the length of their essays (word count). It further investigates whether or not essay length accounts for variance in text quality scores (expert ratings) even when controlling for English language proficiency and other variables (e.g., country, gender, cognitive ability). A weak relationship of proficiency and length as well as a large proportion of variance in text quality explained by length beyond proficiency would be in favor of the judgment bias assumption.

Study 2 focused on possible essay length bias in an experimental setting, investigating the effect of essay length on text quality ratings when there was (per design) no relation between essay length and text quality score. Essays from Study 1 were rated by N = 84 untrained pre-service teachers, using the same TOEFL iBT rubric as the expert raters. As text quality scores were held constant within all essay length conditions, any significant effect of essay length would indicate a judgment bias. Both studies are described in more detail in the following sections.

This study investigates the question of judgment bias assumption vs. appropriate heuristic assumption in a large-scale context with professional human raters. A weak relationship between text length and language proficiency would be indicative of the former assumption, whereas a strong relationship would support the latter. Moreover, if the impact of text length on human ratings was significant and substantial beyond language proficiency, this might indicate a bias on the part of the rater rather than an appropriate heuristic. Thus, Study 1 aims to answer the following research questions:

(1) How is essay length related to language proficiency?

(2) Does text length still account for variance in text quality when English language proficiency is statistically controlled for?

Materials and Methods

Sample and procedure.

The sample consisted of N = 2,722 upper secondary students (11th grade; 58.1% female) in Germany ( n = 894) and Switzerland ( n = 1828) from the interdisciplinary and international research project Measuring English Writing at Secondary Level (MEWS; for an overview see Keller et al., 2020 ). The target population were students attending the academic track of general education grammar schools (ISCED level 3a) in the German federal state Schleswig-Holstein as well as in seven Swiss cantons (Aargau, Basel Stadt, Basel Land, Luzern, St. Gallen, Schwyz, Zurich). In a repeated-measures design, students were assessed at the beginning (T1: August/September 2016; M age = 17.34; SD age = 0.87) and at the end of the school year (T2: May/June 2017; M age = 18.04; SD age = 0.87). The students completed computer-based tests on writing, reading and listening skills, as well as general cognitive ability. Furthermore, they completed a questionnaire measuring background variables and individual characteristics.

Writing prompt

All students answered two independent and two integrated essay writing prompts of the internet-based Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL iBT ® ) that is administered by the Educational Testing Service (ETS) in Princeton. The task instruction was as follows: “In the writing task below you will find a question on a controversial topic. Answer the question in an essay in English. List arguments and counter-arguments, explain them and finally make it clear what your own opinion on the topic is. Your text will be judged on different qualities. These include the presentation of your ideas, the organization of the essay and the linguistic quality and accuracy. You have 30 min to do this. Try to use all of this time as much as possible.” This task instruction was followed by the essay prompt. The maximum writing time was 30 min according to the official TOEFL iBT ® assessment procedure. The essays were scored by trained human raters on the TOEFL 6-point rating scale at ETS. In addition to two human ratings per essay, ETS also provided scores from their automated essay scoring system (e-rater ® ; Burstein et al., 2013 ). For a more detailed description of the scoring procedure and the writing prompts see Rupp et al. (2019) and Keller et al. (2020) . For the purpose of this study, we selected the student responses to the TOEFL iBT independent writing prompt “Teachers,” which showed good measurement qualities (see Rupp et al., 2019 ). Taken together, data collections at T1 and T2 yielded N = 2,389 valid written responses to the following prompt: “A teacher’s ability to relate well with students is more important than excellent knowledge of the subject being taught.”

Text quality and length

The rating of text quality via human and machine scoring was done by ETS. All essays were scored by highly experienced human raters on the operational holistic TOEFL iBT rubric from 0 to 5 ( Chodorow and Burstein, 2004 ). Essays were scored high if they were well-organized and individual ideas were well-developed, if they used specific examples and support to express learners’ opinion on the subject, and if the English language was used accurately to express learners’ ideas. Essays were assigned a score of 0 if they were written in another language, were generally incomprehensible, or if no text was entered.

Each essay received independent ratings by two trained human raters. If the two ratings showed a deviation of 1, the mean of the two scores was used; if they showed a deviation of 2 or more, a third rater (adjudicator) was consulted. Inter-rater agreement, as measured by quadratic weighted kappa (QWK), was satisfying for the prompt “Teachers” at both time points (QWK = 0.67; Hayes and Hatch, 1999 ; see Rupp et al., 2019 for further details). The mean text quality score was M = 3.35 ( SD = 0.72).

Word count was used to measure the length of the essays. The number of words was calculated by the e-Rater scoring engine. The mean word count was M = 311.19 ( SD = 81.91) and the number of words ranged from 41 to 727. We used the number of words rather than other measures of text length (e.g., number of letters) as it is the measure which is most frequently used in the literature: 9 out of 10 studies in the research review by Powers (2005) used word count as the criterion (also see Kobrin et al., 2007 , 2011 ; Crossley and McNamara, 2009 ; Barkaoui, 2010 ; Attali, 2016 ; Wolfe et al., 2016 ; Wind et al., 2017 ). This approach ensures that our analyses can be compared with previous research.

English language proficiency and control variables

Proficiency was operationalized by a combination of different variables: English grade, English writing self-concept, reading and listening comprehension in English. The listening and reading skills were measured with a subset of items from the German National Assessment ( Köller et al., 2010 ). The tasks require a detailed understanding of long, complex reading and listening texts including idiomatic expressions and different linguistic registers. The tests consisted of a total of 133 items for reading, and 118 items for listening that were administered in a multi-matrix-design. Each student was assessed with two rotated 15-min blocks per domain. Item parameters were estimated using longitudinal multidimensional two-parameter item response models in M plus version 8 ( Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2012 ). Student abilities were estimated using 15 plausible values (PVs) per person. The PV reliabilities were 0.92 (T1) and 0.76 (T2) for reading comprehension, and 0.85 (T1) and 0.72 (T2) for listening comprehension. For a more detailed description of the scaling procedure see Köller et al. (2019) .

General cognitive ability was assessed at T1 using the subtests on figural reasoning (N2; 25 items) and on verbal reasoning (V3; 20 items) of the Cognitive Ability Test (KFT 4–12 + R; Heller and Perleth, 2000 ). For each scale 15 PVs were drawn in a two-dimensional item response model. For the purpose of this study, the two PVs were combined to 15 overall PV scores with a reliability of 0.86.

The English writing self-concept was measured with a scale consisting of five items (e.g., “I have always been good at writing in English”; Eccles and Wigfield, 2002 ; Trautwein et al., 2012 ; α = 0.90). Furthermore, country (Germany = 0/Switzerland = 1), gender (male = 0/female = 1) and time of measurement (T1 = 0; T2 = 1) were used as control variables.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted in M plus version 8 ( Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2012 ) based on the 15PV data sets using robust maximum likelihood estimation to account for a hierarchical data structure (i.e., students clustered in classes; type = complex). Full-information maximum likelihood was used to estimate missing values in background variables. Due to the use of 15PVs, all analyses were run 15 times and then averaged (see Rubin, 1987 ).

Confirmatory factor analysis was used to specify a latent proficiency factor. All four proficiency variables showed substantial loadings in a single-factor measurement model (English grade: 0.67; writing self-concept: 0.73; reading comprehension: 0.42; listening comprehension: 0.51). As reading and listening comprehension were measured within the same assessment framework and could thus be expected to share mutual variance beyond the latent factor, their residuals were allowed to correlate. The analyses yielded an acceptable model fit: χ 2 (1) = 3.65, p = 0.06; CFI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.031, SRMR = 0.006.

The relationship between text length and other independent variables was explored with correlational analysis. Multiple regression analysis with latent and manifest predictors was used to investigate the relations between text length, proficiency, and text quality.

The correlation of the latent proficiency factor and text length (word count) was moderately positive: r = 0.36, p < 0.01. This indicates that more proficient students tended to write longer texts. Significant correlations with other variables showed that students tended to write longer texts at T1 ( r = -0.08, p < 0.01), girls wrote longer texts than boys ( r = 0.11, p < 0.01), and higher cognitive ability was associated with longer texts ( r = 0.07, p < 0.01). However, all of these correlations were very weak as a general rule. The association of country and text length was not statistically significant ( r = -0.06, p = 0.10).

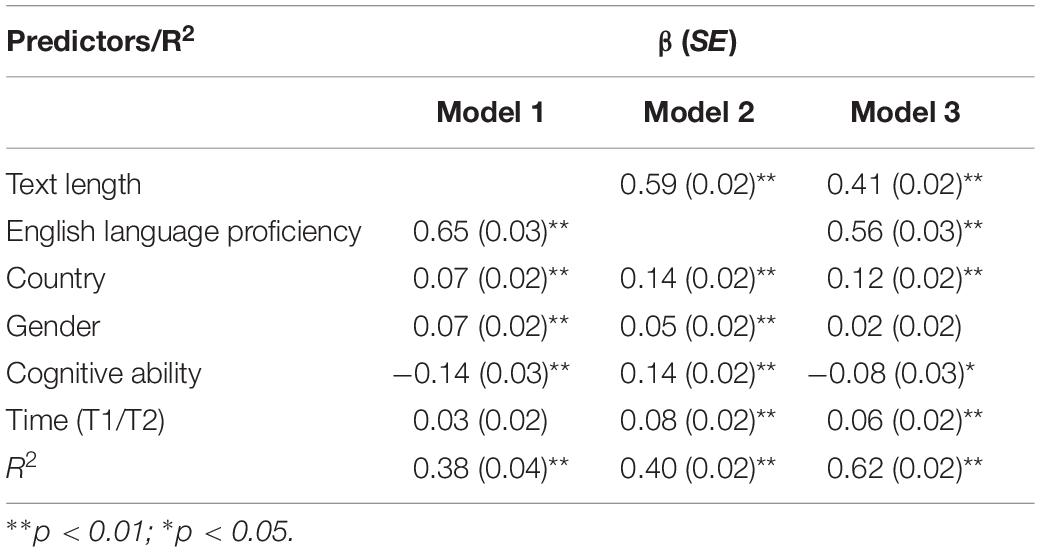

Table 1 presents the results of the multiple linear regression of text quality on text length, proficiency and control variables. The analysis showed that proficiency and the covariates alone explained 38 percent of the variance in text quality ratings, with the latent proficiency factor being by far the strongest predictor (Model 1). The effect of text length on the text quality score was equally strong when including the control variables but not proficiency in the model (Model 2). When both the latent proficiency factor and text length were entered into the regression model (Model 3), the coefficient of text length was reduced but remained significant and substantial, explaining an additional 24% of the variance (ΔR 2 = 0.24 from Model 1 to Model 3). Thus, text length had an incremental effect on text quality beyond a latent English language proficiency factor.

Table 1. Linear regression of text quality on text length, English language proficiency, and control variables: standardized regression coefficients (β) and standard errors (SE).

Study 1 approached the issue of text length by operationalizing the construct of English language proficiency and investigating how it affects the relationship of text length and text quality. This can give us an idea of how text length may influence human judgments even though it is not considered relevant to the construct of writing competence. These secondary analyses of an existing large-scale dataset yielded two central findings: First, text length was only moderately associated with language proficiency. Second, text length strongly influenced writing performance beyond proficiency. Thus, it had an impact on the assigned score that was not captured by the construct of proficiency. These findings could be interpreted in favor of the judgment bias assumption as text length may include both construct-irrelevant and construct-relevant information.

The strengths of this study were the large sample of essays on the same topic and the vast amount of background information that was collected on the student writers (proficiency and control variables). However, there were three major limitations: First, the proficiency construct captured different aspects of English language competence (reading and listening comprehension, writing self-concept, grade), but that operationalization was not comprehensive. Thus, the additional variance explained by text length may still have been due to other aspects that could not be included in the analyses as they were not in the data. Further research with a similar design (primary or secondary analyses) should use additional variables such as grammar/vocabulary knowledge or writing performance in the first language.

The second limitation was the correlational design, which does not allow a causal investigation of the effect of text length on text quality ratings. Drawing inferences which are causal in nature would require an experimental environment in which, for example, text quality is kept constant for texts of different lengths. For that reason, Study 2 was conducted exactly in such a research design.

Last but not least, the question of transferability of these findings remains open. Going beyond standardized large-scale assessment, interdisciplinary research requires us to look at the issue from different perspectives. Findings pertaining to professional raters may not be transferable to teachers, who are required to assess students’ writing in a classroom context. Thus, Study 2 drew on a sample of preservice English teachers and took a closer look at how their ratings were impacted by text length.

Research Questions

In Study 2, we investigated the judgment bias assumption vs. the appropriate heuristic assumption of preservice teachers. As recommended by Powers (2005) , we conducted an experimental study in addition to the correlational design used in Study 1. As text quality scores were held constant within all essay length conditions, any significant effect of essay length would be in favor of the judgment bias assumption. The objective of this study was to answer the following research questions:

(1) How do ratings of pre-service teachers correspond to expert ratings?

(2) Is there an effect of text length on the text quality ratings of preservice English teachers, when there is (per design) no relation between text length and text quality (main effect)?

(3) Does the effect differ for different levels of writing performance (interaction effect)?

Participants and Procedure

The experiment was conducted with N = 84 pre-service teachers ( M Age = 23 years; 80% female), currently enrolled in a higher education teacher training program at a university in Northern Germany. They had no prior rating experience of this type of learner texts. The experiment was administered with the Student Inventory ASSET ( Jansen et al., 2019 ), an online tool to assess students’ texts within an experimental environment. Participants were asked to rate essays from the MEWS project (see Study 1) on the holistic rubric used by the human raters at ETS (0–5; https://www.ets.org/s/toefl/pdf/toefl_writing_rubrics.pdf ). Every participant had to rate 9 out of 45 essays in randomized order, representing all possible combinations of text quality and text length. Before the rating process began, participants were given information about essay writing in the context of the MEWS study (school type; school year; students’ average age; instructional text) and they were presented the TOEFL writing rubric as the basis for their judgments. They had 15 min to get an overview of all nine texts before they were asked to rate each text on the rubric. Throughout the rating process, they were allowed to highlight parts of the texts.

The operationalization of text quality and text length as categorical variables as well as the procedure of selecting an appropriate essay sample for the study is explained in the following.

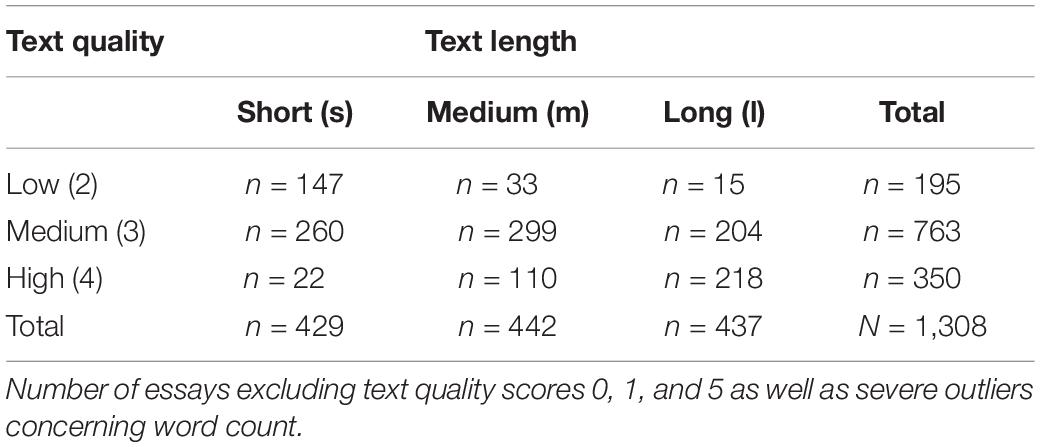

Text Length and Text Quality

The essays used in the experiment were selected on the basis of the following procedure, which took both text quality and text length as independent variables into account. The first independent variable of the essay (overall text quality) was operationalized via scores assigned by two trained human raters from ETS on a holistic six-point scale (0–5; see Study 1 and Appendix A). In order to measure the variable as precisely as possible, we only included essays for which both human raters had assigned the same score, resulting in a sample of N = 1,333 essays. As a result, three gradations of text quality were considered in the current study: lower quality (score 2), medium quality (score 3) and higher quality (score 4). The corpus included only few texts (10.4%) with the extreme scores of 0, 1, and 5; these were therefore excluded from the essay pool. We thus realized a 3 × 3 factorial within-subjects design. The second independent variable text length was measured via the word count of the essays, calculated by the e-rater (c) scoring engine. As with text quality, this variable was subdivided in three levels: rather short texts (s), medium-length texts (m), and long texts (l). All available texts were analyzed regarding their word count distribution. Severe outliers were excluded. The remaining N = 1308 essays were split in three even groups: the lower (=261 words), middle (262–318 words) and upper third (=319 words). Table 2 shows the distribution of essays for the resulting combinations of text length and text score.

Table 2. Distribution of essays in the sample contingent on text quality and text length groupings.

Selection of Essays

For each text length group (s, m, and l), the mean word count across all three score groups was calculated. Then, the score group (2, 3, or 4) with the smallest number of essays in a text length group was taken as reference (e.g., n = 22 short texts of high quality or n = 15 long texts of low quality). Within each text length group, the five essays being – word count-wise – closest to the mean of the reference were chosen for the study. This was possible with mostly no or only minor deviations. In case of multiple possible matches, the essay was selected at random. This selection procedure resulted in a total sample of 45 essays, with five essays for each combination of score group (2, 3, 4) and length group (s, m, l).

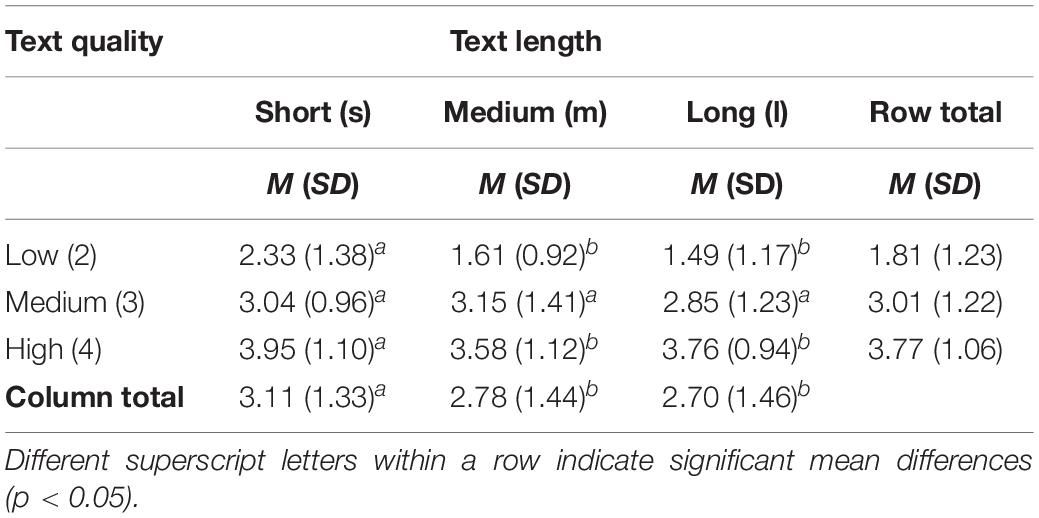

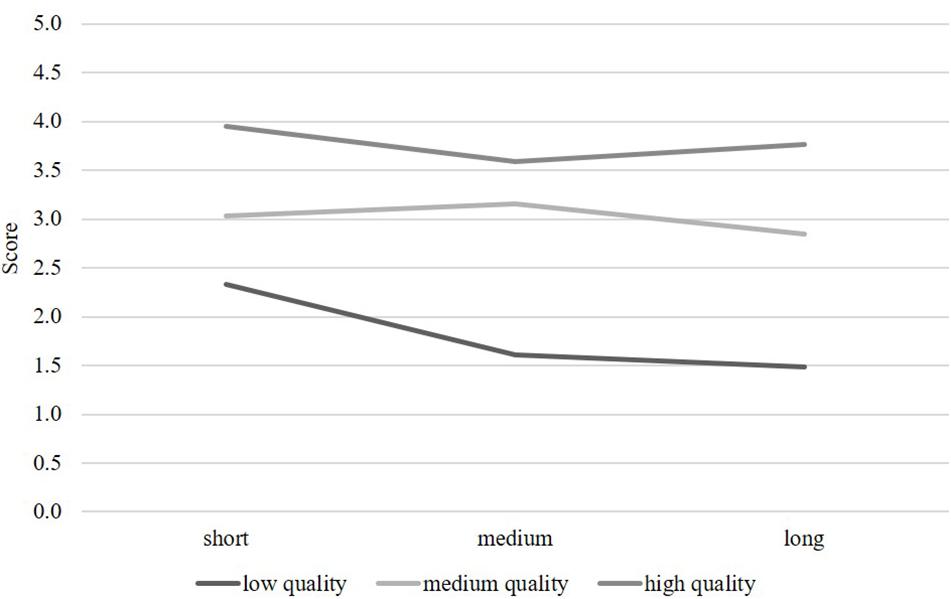

A repeated-measures ANOVA with two independent variables (text quality and text length) was conducted to test the two main effects and their interaction on participants’ ratings (see Table 3 ). Essay ratings were treated as a within-subject factor, accounting for dependencies of the ratings nested within raters. The main effect of text quality scores on participants’ ratings showed significant differences between the three text quality conditions ( low , medium , high ) that corresponded to expert ratings; F (2, 82) = 209.04, p < 0.001, d = 4.52. There was also a significant main effect for the three essay length conditions ( short , medium , long ); F (2, 82) = 9.14, p < 0.001, d = 0.94. Contrary to expectations, essay length was negatively related to participants’ ratings, meaning that shorter texts received higher scores than longer texts. The interaction of text quality and text length also had a significant effect; F (4, 80) = 3.93, p < 0.01, d = 0.89. Post-hoc tests revealed that texts of low quality were especially impacted by essay length in a negative way (see Figure 1 ).

Table 3. Participants’ ratings of text quality: means (M) and standard deviations (SD).

Figure 1. Visualization of the interaction between text length and text quality.

The experiment conducted in Study 2 found a very strong significant main effect for text quality, indicating a high correspondence of pre-service teachers’ ratings with the expert ratings of text quality. The main effect of text length was also significant, but was qualified by a significant interaction effect text quality x text length, indicating that low quality texts were rated even more negative the longer they were. This negative effect of text length was contrary to expectations: The pre-service teachers generally tended to assign higher scores to shorter texts. Thus, they seemed to value shorter texts over longer texts. However, this was mainly true for texts of low quality.

These findings were surprising against the research background that would suggest that longer texts are typically associated with higher scores of text quality, particularly in the context of second language writing. Therefore, it is even more important to discuss the limitations of the design before interpreting the results: First, the sample included relatively inexperienced pre-service teachers. Further research is needed to show whether these findings are transferable to in-service teachers with reasonable experience in judging students’ writing. Moreover, further studies could use assessment rubrics that teachers are more familiar with, such as the CEFR ( Council of Europe, 2001 ; also see Fleckenstein et al., 2020 ). Second, the selection process of essays may have reduced the ecological validity of the experiment. As there were only few long texts of low quality and few short texts of high quality in the actual sample (see Table 2 ), the selection of texts in the experimental design was – to some degree – artificial. This could also have influenced the frame of reference for the pre-service teachers as the distribution of the nine texts was different from what one would find naturally in an EFL classroom. Third, the most important limitation of this study is the question of the reference norm, a point which applies to studies of writing assessment in general. In our study, writing quality was operationalized using expert ratings, which have been shown to be influenced by text length in many investigations as well as in Study 1. If the expert ratings are biased themselves, the findings of this study may also be interpreted as pre-service teachers (unlike expert raters) not showing a text length bias at all: shorter texts should receive higher scores than longer ones if the quality assigned by the expert raters is held constant. We discuss these issues concerning the reference norm in more detail in the next section.

All three limitations may have affected ratings in a way that could have reinforced a negative effect of text length on text quality ratings. However, as research on the effect of text length on teachers’ judgments is scarce, we should consider the possibility that the effect is actually different from the (positive) one typically found for professional human raters. There are a number of reasons to assume differences in the rating processes that are discussed in more detail in the following section. Furthermore, we will discuss what this means in terms of the validity of the gold standard in writing assessment.

General Discussion

Combining the results of both studies, we have reason to assume that (a) text length induces judgment bias and (b) the effect of text length largely depends on the rater and/or the rating context. More specifically, the findings of the two studies can be summarized as follows: Professional human raters tend to reward longer texts beyond the relationship of text length and proficiency. Compared to this standard, inexperienced EFL teachers tend to undervalue text length, meaning that they sanction longer texts especially when text quality is low. This in turn may be based on an implicit expectation deeply ingrained in the minds of many EFL teachers: that writing in a foreign language is primarily about avoiding mistakes, and that longer texts typically contain more of them than shorter ones ( Keller, 2016 ). Preservice teachers might be particularly afflicted with this view of writing as they would have experienced it as learners up-close and personal, not too long ago. Both findings point toward the judgment bias assumption, but with opposite directions. These seemingly contradictory findings lead to interesting and novel research questions – both in the field of standardized writing assessment and in the field of teachers’ diagnostic competence.

Only if we take professional human ratings as reliable benchmark scores can we infer that teachers’ ratings are biased (in a negative way). If we consider professional human ratings to be biased themselves (in a positive way), then the preservice teachers’ judgments might appear to be unbiased. However, it would be implausible to assume that inexperienced teachers’ judgments are less biased than those of highly trained expert raters. Even if professional human ratings are flawed themselves, they are the best possible measure of writing quality, serving as a reference even for NLP tools ( Crossley, 2020 ). It thus makes much more sense to consider the positive impact of text length on professional human ratings – at least to a degree – an appropriate heuristic. This means that teachers’ judgments would generally benefit from applying the same heuristic when assessing students’ writing, as long as it does not become a bias.

In his literature review, Crossley (2020) sees the nature of the writing task to be among the central limitations when it comes to generalizing findings in the context of writing assessment. Written responses to standardized tests (such as the TOEFL) may produce linguistic features that differ from writing samples produced in the classroom or in other, more authentic writing environments. Moreover, linguistic differences may also occur depending on a writing sample being timed or untimed. Timed samples provide fewer opportunities for planning, revising, and development of ideas as compared to untimed samples, where students are more likely to plan, reflect, and revise their writing. These differences may surface in timed writing in such a way that it would be less cohesive and less complex both lexically and syntactically.

In the present research, such differences may account for the finding that pre-service teachers undervalue text length compared to professional raters. Even though the participants in Study 2 were informed about the context in which the writing samples were collected, they may have underestimated the challenges of a timed writing task in an unfamiliar format. In the context of their own classrooms, students rarely have strict time limitations when working on complex writing tasks. If they do, in an exam consisting of an argumentative essay, for example, it is usually closer to 90 min than to 30 min (at least in the case of the German pre-service teachers who participated in this study). Thus, text length may not be a good indicator of writing quality in the classroom. On the contrary, professional raters may value length as a construct-relevant feature of writing quality in a timed task, for example as an indicator of writing fluency (see Peng et al., 2020 ).

Furthermore, text length as a criterion of quality cannot be generalized over different text types at random. The genres which are taught in EFL courses, or assessed in EFL exams, differ considerably with respect to expected length. In five paragraph essays, for example, developing an argument requires a certain scope and attention to detail, so that text length is a highly salient feature for overall text quality. The same might not be true for e-mail writing, a genre frequently taught in EFL classrooms ( Fleckenstein et al., in press ). E-mails are usually expected to be concise and to the point, so that longer texts might seem prolix, or rambling. Such task-specific demands need to be taken into account when it comes to interpreting our findings. The professional raters employed in our study were schooled extensively for rating five-paragraph essays, which included a keen appreciation of text length as a salient criterion of text quality. The same might not be said of classroom teachers, who encounter a much wider range of genres in their everyday teaching and might therefore be less inclined to consider text length as a relevant feature. Further research should consider different writing tasks in order to investigate whether text length is particularly important to the genre of the argumentative essay.

Our results underscore the importance of considering whether or not text length should be taken into account for different contexts of writing assessment. This holds true for classroom assessment, where teachers should make their expectations regarding text length explicit, as well as future studies with professional raters. Crossley (2020) draws attention to the transdisciplinary perspective of the field as a source for complications: “The complications arise from the interdisciplinary nature of this type of research which often combines writing, linguistics, statistics, and computer science fields. With so many fields involved, it is often easy to overlook confounding factors” (p. 428). The present research shows how the answer to one and the same research question – How does text length influence human judgment? – can be very different from different perspectives and within different areas of educational research. Depending on the population (professional raters vs. pre-service teachers) and the methodology (correlational analysis vs. experimental design), our findings illustrate a broad range of possible investigations and outcomes. Thus, it is a paramount example of why interdisciplinary research in education is not only desirable but imperative. Without an interdisciplinary approach, our view of the text length effect would be uni-dimensional and fragmentary. Only the combination of different perspectives and methods can live up to the demands of a complex issue such as writing assessment, identify research gaps, and challenge research traditions. Further research is needed to investigate the determinants of the strength and the direction of the bias. It is necessary to take a closer look at the rating processes of (untrained) teachers and (trained) raters, respectively, in order to investigate similarities and differences. Research pertaining to judgment heuristics/biases can be relevant for both teacher and rater training. However, the individual concerns and characteristics of the two groups need to be taken into account. This could be done, for example, by directly comparing the two groups in an experimental study. Both in teacher education and in text assessment studies, we should have a vigorous discussion about how appropriate heuristics of expert raters can find their way into the training of novice teachers and inexperienced raters in an effort to reduce judgement bias.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ministry of Education, Science and Cultural Affairs of the German federal state Schleswig-Holstein. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

JF analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. TJ and JM collected the experimental data for Study 2 and supported the data analysis. SK and OK provided the dataset for Study 1. TJ, JM, SK, and OK provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Attali, Y. (2016). A comparison of newly-trained and experienced raters on a standardized writing assessment. Lang. Test. 33, 99–115. doi: 10.1177/0265532215582283

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barkaoui, K. (2010). Explaining ESL essay holistic scores: a multilevel modeling approach. Lang. Test. 27, 515–535. doi: 10.1177/0265532210368717

Bejar, I. I. (2011). A validity-based approach to quality control and assurance of automated scoring. Assess. Educ. 18, 319–341. doi: 10.1080/0969594x.2011.555329

Ben-Simon, A., and Bennett, R. E. (2007). Toward more substantively meaningful automated essay scoring. J. Technol. Learn. Asses. 6, [Epub ahead of print].

Google Scholar

Birkel, P., and Birkel, C. (2002). Wie einig sind sich Lehrer bei der Aufsatzbeurteilung? Eine Replikationsstudie zur Untersuchung von Rudolf Weiss. Psychol. Erzieh. Unterr. 49, 219–224.

Brunswik, E. (1955). Representative design and probabilistic theory in a functional psychology. Psychol. Rev. 62, 193–217. doi: 10.1037/h0047470

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Burstein, J., Tetreault, J., and Madnani, N. (2013). “The E-rater ® automated essay scoring system,” in Handbook of Automated Essay Evaluation , eds M. D. Shermis and J. Burstein (Abingdon: Routledge), 77–89.

Chenoweth, N. A., and Hayes, J. R. (2001). Fluency in writing: generating text in L1 and L2. Written Commun. 18, 80–98. doi: 10.1177/0741088301018001004

Chodorow, M., and Burstein, J. (2004). Beyond essay length: evaluating e-rater ® ’s performance on toefl ® essays. ETS Res. Rep. 2004, i–38. doi: 10.1002/j.2333-8504.2004.tb01931.x

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching and Assessment. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Crossley, S. (2020). Linguistic features in writing quality and development: an overview. J. Writ. Res. 11, 415–443. doi: 10.17239/jowr-2020.11.03.01

Crossley, S. A., and McNamara, D. S. (2009). Computational assessment of lexical differences in L1 and L2 writing. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 18, 119–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2009.02.002

Cumming, A., Kantor, R., and Powers, D. E. (2002). Decision making while rating ESL/EFL writing tasks: a descriptive framework. Modern Lang. J. 86, 67–96. doi: 10.1111/1540-4781.00137

Deane, P. (2013). On the relation between automated essay scoring and modern views of the writing construct. Assess. Writ. 18, 7–24. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2012.10.002

Eccles, J. S., and Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev.Psychol. 53, 109–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Fleckenstein, J., Keller, S., Krüger, M., Tannenbaum, R. J., and Köller, O. (2020). Linking TOEFL iBT ® writing scores and validity evidence from a standard setting study. Assess. Writ. 43:100420. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2019.100420

Fleckenstein, J., Meyer, J., Jansen, T., Reble, R., Krüger, M., Raubach, E., et al. (in press). “Was macht Feedback effektiv? Computerbasierte Leistungsrückmeldung anhand eines Rubrics beim Schreiben in der Fremdsprache Englisch,” in Tagungsband Bildung, Schule und Digitalisierung , eds K. Kaspar, M. Becker-Mrotzek, S. Hofhues, J. König, and D. Schmeinck (Münster: Waxmann

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., and Hebert, M. (2011). It is more than just the message: presentation effects in scoring writing. Focus Except. Child. 44, 1–12.

Guo, L., Crossley, S. A., and McNamara, D. S. (2013). Predicting human judgments of essay quality in both integrated and independent second language writing samples: a comparison study. Assess. Writ. 18, 218–238. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2013.05.002

Hachmeister, S. (2019). “Messung von Textqualität in Ereignisberichten,” in Schreibkompetenzen Messen, Beurteilen und Fördern (6. Aufl) , eds I. Kaplan and I. Petersen (Münster: Waxmann Verlag), 79–99.

Hayes, J. R., and Hatch, J. A. (1999). Issues in measuring reliability: Correlation versus percentage of agreement. Writt. Commun. 16, 354–367. doi: 10.1177/0741088399016003004

Heller, K. A., and Perleth, C. (2000). KFT 4-12+ R Kognitiver Fähigkeitstest für 4. Bis 12. Klassen, Revision. Göttingen: Beltz Test.

Jansen, T., Vögelin, C., Machts, N., Keller, S. D., and Möller, J. (2019). Das Schülerinventar ASSET zur Beurteilung von Schülerarbeiten im Fach Englisch: Drei experimentelle Studien zu Effekten der Textqualität und der Schülernamen. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht 66, 303–315. doi: 10.2378/peu2019.art21d

Keller, S. (2016). Measuring Writing at Secondary Level (MEWS). Eine binationale Studie. Babylonia 3, 46–48.

Keller, S. D., Fleckenstein, J., Krüger, M., Köller, O., and Rupp, A. A. (2020). English writing skills of students in upper secondary education: results from an empirical study in Switzerland and Germany. J. Second Lang. Writ. 48:100700. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2019.100700

Kobrin, J. L., Deng, H., and Shaw, E. J. (2007). Does quantity equal quality? the relationship between length of response and scores on the SAT essay. J. Appl. Test. Technol. 8, 1–15. doi: 10.1097/nne.0b013e318276dee0

Kobrin, J. L., Deng, H., and Shaw, E. J. (2011). The association between SAT prompt characteristics, response features, and essay scores. Assess. Writ. 16, 154–169. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2011.01.001

Köller, O., Fleckenstein, J., Meyer, J., Paeske, A. L., Krüger, M., Rupp, A. A., et al. (2019). Schreibkompetenzen im Fach Englisch in der gymnasialen Oberstufe. Z. Erziehungswiss. 22, 1281–1312. doi: 10.1007/s11618-019-00910-3

Köller, O. Knigge, M. and Tesch B. (eds.) (2010). Sprachliche Kompetenzen im Ländervergleich. Germany: Waxmann.

Marshall, J. C. (1967). Composition errors and essay examination grades re-examined. Am. Educ. Res. J. 4, 375–385. doi: 10.3102/00028312004004375

McCutchen, D., Teske, P., and Bankston, C. (2008). “Writing and cognition: implications of the cognitive architecture for learning to write and writing to learn,” in Handbook of research on Writing: History, Society, School, Individual, Text , ed. C. Bazerman (Milton Park: Taylor & Francis Group), 451–470.

McNamara, D. S., Crossley, S. A., Roscoe, R. D., Allen, L. K., and Dai, J. (2015). A hierarchical classification approach to automated essay scoring. Assess. Writ. 23, 35–59. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2014.09.002

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Osnes, J. (1995). “Der Einflus von Handschrift und Fehlern auf die Aufsatzbeurteilung,” in Die Fragwürdigkeit der Zensurengebung (9. Aufl., S) , ed. K. Ingenkamp (Göttingen: Beltz), 131–147.

Peng, J., Wang, C., and Lu, X. (2020). Effect of the linguistic complexity of the input text on alignment, writing fluency, and writing accuracy in the continuation task. Langu. Teach. Res. 24, 364–381. doi: 10.1177/1362168818783341

Perelman, L. (2014). When “the state of the art” is counting words. Assess. Writ. 21, 104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2014.05.001

Pohlmann-Rother, S., Schoreit, E., and Kürzinger, A. (2016). Schreibkompetenzen von Erstklässlern quantitativ-empirisch erfassen-Herausforderungen und Zugewinn eines analytisch-kriterialen Vorgehens gegenüber einer holistischen Bewertung. J. Educ. Res. Online 8, 107–135.

Powers, D. E. (2005). Wordiness”: a selective review of its influence, and suggestions for investigating its relevance in tests requiring extended written responses. ETS Res. Rep. i–14.

Quinlan, T., Higgins, D., and Wolff, S. (2009). Evaluating the construct-coverage of the e-rater ® scoring engine. ETS Res. Rep. 2009, i–35. doi: 10.1002/j.2333-8504.2009.tb02158.x

Rezaei, A. R., and Lovorn, M. (2010). Reliability and validity of rubrics for assessment through writing. Assess. Writ. 15, 18–39. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2010.01.003

Rubin, D. B. (1987). The calculation of posterior distributions by data augmentation: comment: a noniterative sampling/importance resampling alternative to the data augmentation algorithm for creating a few imputations when fractions of missing information are modest: the SIR algorithm. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 82, 543–546. doi: 10.2307/2289460

Ruegg, R., and Sugiyama, Y. (2010). Do analytic measures of content predict scores assigned for content in timed writing? Melbourne Papers in Language Testing 15, 70–91.

Rupp, A. A., Casabianca, J. M., Krüger, M., Keller, S., and Köller, O. (2019). Automated essay scoring at scale: a case study in Switzerland and Germany. ETS Res. Rep. Ser. 2019, 1–23. doi: 10.1002/ets2.12249

Scannell, D. P., and Marshall, J. C. (1966). The effect of selected composition errors on grades assigned to essay examinations. Am. Educ. Res. J. 3, 125–130. doi: 10.3102/00028312003002125

Shermis, M. D. (2014). The challenges of emulating human behavior in writing assessment. Assess. Writ. 22, 91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2014.07.002

Silva, T. (1993). Toward an understanding of the distinct nature of L2 writing: the ESL research and its implications. TESOL Q. 27, 657–77. doi: 10.2307/3587400