Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Words to Use in an Essay: 300 Essay Words

Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

Words to use in the essay introduction, words to use in the body of the essay, words to use in your essay conclusion, how to improve your essay writing vocabulary.

It’s not easy to write an academic essay .

Many students struggle to word their arguments in a logical and concise way.

To make matters worse, academic essays need to adhere to a certain level of formality, so we can’t always use the same word choices in essay writing that we would use in daily life.

If you’re struggling to choose the right words for your essay, don’t worry—you’ve come to the right place!

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay.

The introduction is one of the hardest parts of an essay to write.

You have only one chance to make a first impression, and you want to hook your reader. If the introduction isn’t effective, the reader might not even bother to read the rest of the essay.

That’s why it’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate with the words you choose at the beginning of your essay.

Many students use a quote in the introductory paragraph to establish credibility and set the tone for the rest of the essay.

When you’re referencing another author or speaker, try using some of these phrases:

To use the words of X

According to X

As X states

Example: To use the words of Hillary Clinton, “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health.”

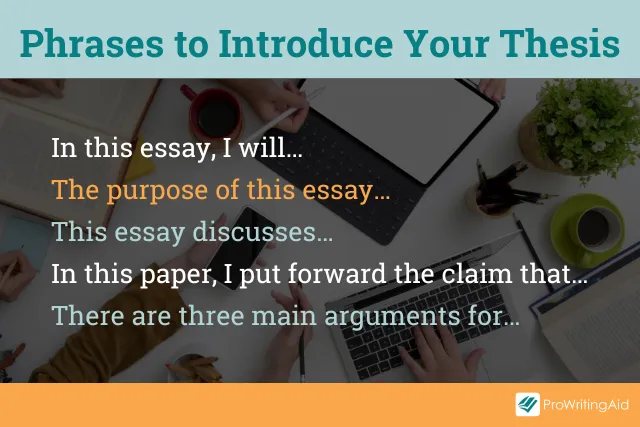

Near the end of the introduction, you should state the thesis to explain the central point of your paper.

If you’re not sure how to introduce your thesis, try using some of these phrases:

In this essay, I will…

The purpose of this essay…

This essay discusses…

In this paper, I put forward the claim that…

There are three main arguments for…

Example: In this essay, I will explain why dress codes in public schools are detrimental to students.

After you’ve stated your thesis, it’s time to start presenting the arguments you’ll use to back up that central idea.

When you’re introducing the first of a series of arguments, you can use the following words:

First and foremost

First of all

To begin with

Example: First , consider the effects that this new social security policy would have on low-income taxpayers.

All these words and phrases will help you create a more successful introduction and convince your audience to read on.

The body of your essay is where you’ll explain your core arguments and present your evidence.

It’s important to choose words and phrases for the body of your essay that will help the reader understand your position and convince them you’ve done your research.

Let’s look at some different types of words and phrases that you can use in the body of your essay, as well as some examples of what these words look like in a sentence.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitioning from one argument to another is crucial for a good essay.

It’s important to guide your reader from one idea to the next so they don’t get lost or feel like you’re jumping around at random.

Transition phrases and linking words show your reader you’re about to move from one argument to the next, smoothing out their reading experience. They also make your writing look more professional.

The simplest transition involves moving from one idea to a separate one that supports the same overall argument. Try using these phrases when you want to introduce a second correlating idea:

Additionally

In addition

Furthermore

Another key thing to remember

In the same way

Correspondingly

Example: Additionally , public parks increase property value because home buyers prefer houses that are located close to green, open spaces.

Another type of transition involves restating. It’s often useful to restate complex ideas in simpler terms to help the reader digest them. When you’re restating an idea, you can use the following words:

In other words

To put it another way

That is to say

To put it more simply

Example: “The research showed that 53% of students surveyed expressed a mild or strong preference for more on-campus housing. In other words , over half the students wanted more dormitory options.”

Often, you’ll need to provide examples to illustrate your point more clearly for the reader. When you’re about to give an example of something you just said, you can use the following words:

For instance

To give an illustration of

To exemplify

To demonstrate

As evidence

Example: Humans have long tried to exert control over our natural environment. For instance , engineers reversed the Chicago River in 1900, causing it to permanently flow backward.

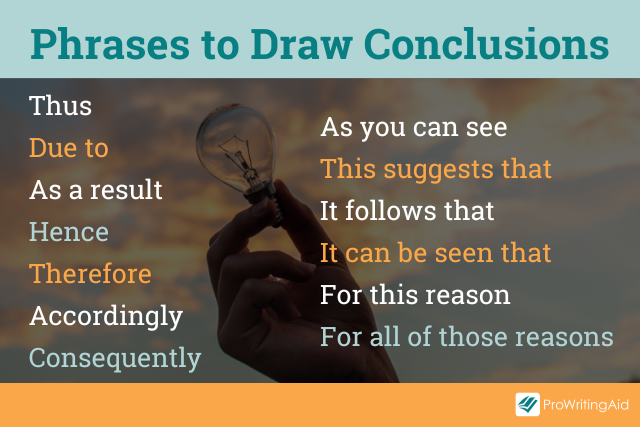

Sometimes, you’ll need to explain the impact or consequence of something you’ve just said.

When you’re drawing a conclusion from evidence you’ve presented, try using the following words:

As a result

Accordingly

As you can see

This suggests that

It follows that

It can be seen that

For this reason

For all of those reasons

Consequently

Example: “There wasn’t enough government funding to support the rest of the physics experiment. Thus , the team was forced to shut down their experiment in 1996.”

When introducing an idea that bolsters one you’ve already stated, or adds another important aspect to that same argument, you can use the following words:

What’s more

Not only…but also

Not to mention

To say nothing of

Another key point

Example: The volcanic eruption disrupted hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover , it impacted the local flora and fauna as well, causing nearly a hundred species to go extinct.

Often, you'll want to present two sides of the same argument. When you need to compare and contrast ideas, you can use the following words:

On the one hand / on the other hand

Alternatively

In contrast to

On the contrary

By contrast

In comparison

Example: On the one hand , the Black Death was undoubtedly a tragedy because it killed millions of Europeans. On the other hand , it created better living conditions for the peasants who survived.

Finally, when you’re introducing a new angle that contradicts your previous idea, you can use the following phrases:

Having said that

Differing from

In spite of

With this in mind

Provided that

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

Notwithstanding

Example: Shakespearean plays are classic works of literature that have stood the test of time. Having said that , I would argue that Shakespeare isn’t the most accessible form of literature to teach students in the twenty-first century.

Good essays include multiple types of logic. You can use a combination of the transitions above to create a strong, clear structure throughout the body of your essay.

Strong Verbs for Academic Writing

Verbs are especially important for writing clear essays. Often, you can convey a nuanced meaning simply by choosing the right verb.

You should use strong verbs that are precise and dynamic. Whenever possible, you should use an unambiguous verb, rather than a generic verb.

For example, alter and fluctuate are stronger verbs than change , because they give the reader more descriptive detail.

Here are some useful verbs that will help make your essay shine.

Verbs that show change:

Accommodate

Verbs that relate to causing or impacting something:

Verbs that show increase:

Verbs that show decrease:

Deteriorate

Verbs that relate to parts of a whole:

Comprises of

Is composed of

Constitutes

Encompasses

Incorporates

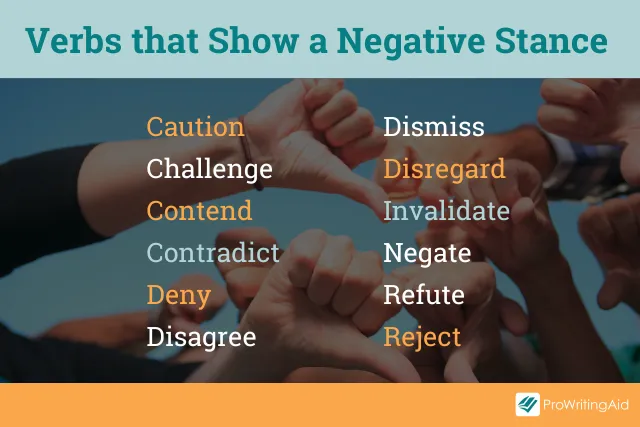

Verbs that show a negative stance:

Misconstrue

Verbs that show a positive stance:

Substantiate

Verbs that relate to drawing conclusions from evidence:

Corroborate

Demonstrate

Verbs that relate to thinking and analysis:

Contemplate

Hypothesize

Investigate

Verbs that relate to showing information in a visual format:

Useful Adjectives and Adverbs for Academic Essays

You should use adjectives and adverbs more sparingly than verbs when writing essays, since they sometimes add unnecessary fluff to sentences.

However, choosing the right adjectives and adverbs can help add detail and sophistication to your essay.

Sometimes you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is useful and should be taken seriously. Here are some adjectives that create positive emphasis:

Significant

Other times, you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is harmful or ineffective. Here are some adjectives that create a negative emphasis:

Controversial

Insignificant

Questionable

Unnecessary

Unrealistic

Finally, you might need to use an adverb to lend nuance to a sentence, or to express a specific degree of certainty. Here are some examples of adverbs that are often used in essays:

Comprehensively

Exhaustively

Extensively

Respectively

Surprisingly

Using these words will help you successfully convey the key points you want to express. Once you’ve nailed the body of your essay, it’s time to move on to the conclusion.

The conclusion of your paper is important for synthesizing the arguments you’ve laid out and restating your thesis.

In your concluding paragraph, try using some of these essay words:

In conclusion

To summarize

In a nutshell

Given the above

As described

All things considered

Example: In conclusion , it’s imperative that we take action to address climate change before we lose our coral reefs forever.

In addition to simply summarizing the key points from the body of your essay, you should also add some final takeaways. Give the reader your final opinion and a bit of a food for thought.

To place emphasis on a certain point or a key fact, use these essay words:

Unquestionably

Undoubtedly

Particularly

Importantly

Conclusively

It should be noted

On the whole

Example: Ada Lovelace is unquestionably a powerful role model for young girls around the world, and more of our public school curricula should include her as a historical figure.

These concluding phrases will help you finish writing your essay in a strong, confident way.

There are many useful essay words out there that we didn't include in this article, because they are specific to certain topics.

If you're writing about biology, for example, you will need to use different terminology than if you're writing about literature.

So how do you improve your vocabulary skills?

The vocabulary you use in your academic writing is a toolkit you can build up over time, as long as you take the time to learn new words.

One way to increase your vocabulary is by looking up words you don’t know when you’re reading.

Try reading more books and academic articles in the field you’re writing about and jotting down all the new words you find. You can use these words to bolster your own essays.

You can also consult a dictionary or a thesaurus. When you’re using a word you’re not confident about, researching its meaning and common synonyms can help you make sure it belongs in your essay.

Don't be afraid of using simpler words. Good essay writing boils down to choosing the best word to convey what you need to say, not the fanciest word possible.

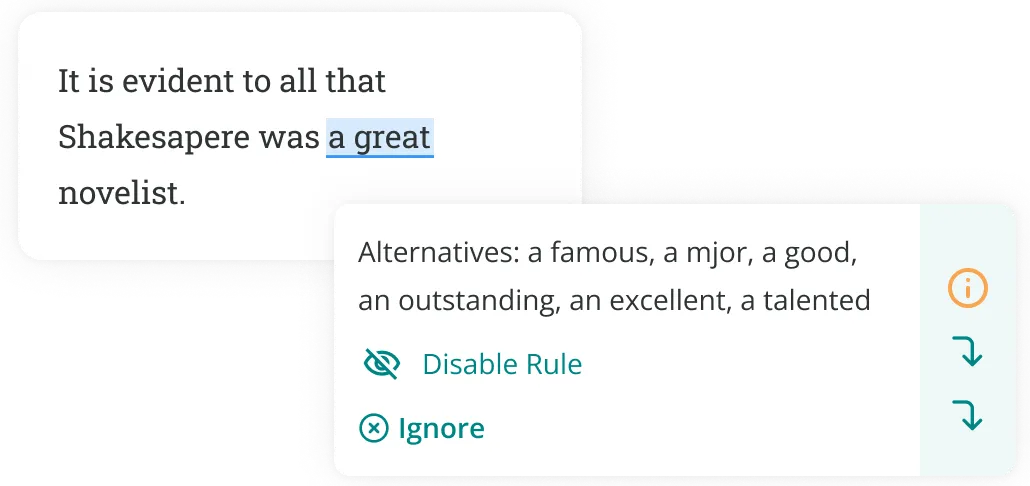

Finally, you can use ProWritingAid’s synonym tool or essay checker to find more precise and sophisticated vocabulary. Click on weak words in your essay to find stronger alternatives.

There you have it: our compilation of the best words and phrases to use in your next essay . Good luck!

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Thesis and Purpose Statements

Use the guidelines below to learn the differences between thesis and purpose statements.

In the first stages of writing, thesis or purpose statements are usually rough or ill-formed and are useful primarily as planning tools.

A thesis statement or purpose statement will emerge as you think and write about a topic. The statement can be restricted or clarified and eventually worked into an introduction.

As you revise your paper, try to phrase your thesis or purpose statement in a precise way so that it matches the content and organization of your paper.

Thesis statements

A thesis statement is a sentence that makes an assertion about a topic and predicts how the topic will be developed. It does not simply announce a topic: it says something about the topic.

Good: X has made a significant impact on the teenage population due to its . . . Bad: In this paper, I will discuss X.

A thesis statement makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of the paper. It summarizes the conclusions that the writer has reached about the topic.

A thesis statement is generally located near the end of the introduction. Sometimes in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or an entire paragraph.

A thesis statement is focused and specific enough to be proven within the boundaries of the paper. Key words (nouns and verbs) should be specific, accurate, and indicative of the range of research, thrust of the argument or analysis, and the organization of supporting information.

Purpose statements

A purpose statement announces the purpose, scope, and direction of the paper. It tells the reader what to expect in a paper and what the specific focus will be.

Common beginnings include:

“This paper examines . . .,” “The aim of this paper is to . . .,” and “The purpose of this essay is to . . .”

A purpose statement makes a promise to the reader about the development of the argument but does not preview the particular conclusions that the writer has drawn.

A purpose statement usually appears toward the end of the introduction. The purpose statement may be expressed in several sentences or even an entire paragraph.

A purpose statement is specific enough to satisfy the requirements of the assignment. Purpose statements are common in research papers in some academic disciplines, while in other disciplines they are considered too blunt or direct. If you are unsure about using a purpose statement, ask your instructor.

This paper will examine the ecological destruction of the Sahel preceding the drought and the causes of this disintegration of the land. The focus will be on the economic, political, and social relationships which brought about the environmental problems in the Sahel.

Sample purpose and thesis statements

The following example combines a purpose statement and a thesis statement (bold).

The goal of this paper is to examine the effects of Chile’s agrarian reform on the lives of rural peasants. The nature of the topic dictates the use of both a chronological and a comparative analysis of peasant lives at various points during the reform period. . . The Chilean reform example provides evidence that land distribution is an essential component of both the improvement of peasant conditions and the development of a democratic society. More extensive and enduring reforms would likely have allowed Chile the opportunity to further expand these horizons.

For more tips about writing thesis statements, take a look at our new handout on Developing a Thesis Statement.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

How to Write a Statement of Purpose for Graduate School

Congrats! You’ve chosen a graduate program , read up on tips for applying to grad school , and even wrote a focused grad school resumé . But if you’re like many students, you’ve left the most daunting part of the application process for last—writing a statement of purpose. The good news is, the task doesn’t have to feel so overwhelming, as long as you break the process down into simple, actionable steps. Below, learn how to write a strong, unique statement of purpose that will impress admissions committees and increase your chances of getting into your dream school.

What is a statement of purpose?

A statement of purpose (SOP), sometimes referred to as a personal statement, is a critical piece of a graduate school application that tells admissions committees who you are, what your academic and professional interests are, and how you’ll add value to the graduate program you’re applying to.

Jared Pierce, associate director of enrollment services at Northeastern University, says a strong statement of purpose can be the deciding factor in a graduate student’s admission.

“Your statement of purpose is where you tell your story about who you are and why you deserve to be a part of the [university’s] community. It gives the admissions committee the chance to get to know you and understand how you’ll add value to the classroom,” he says.

How long should a statement of purpose be?

“A statement of purpose should be between 500 and 1,000 words,” Pierce says, noting that it should typically not exceed a single page. He advises that students use a traditional font at a readable size (11- or 12-pt) and leave enough whitespace in the margins to make the statement easy-to-read. Make sure to double-space the statement if the university has requested it, he adds.

Interested in learning more about Northeastern’s graduate programs?

Get your questions answered by our enrollment team.

REQUEST INFORMATION

How to Write a Statement of Purpose: A Step-by-Step Guide

Now that you understand how to format a statement of purpose, you can begin drafting your own. Getting started can feel daunting, but Pierce suggests making the process more manageable by breaking down the writing process into four easy steps.

1. Brainstorm your ideas.

First, he says, try to reframe the task at hand and get excited for the opportunity to write your statement of purpose. He explains:

“Throughout the application process, you’re afforded few opportunities to address the committee directly. Here is your chance to truly speak directly to them. Each student arrives at this process with a unique story, including prior jobs, volunteer experience, or undergraduate studies. Think about what makes you you and start outlining.”

When writing your statement of purpose, he suggests asking yourself these key questions:

- Why do I want this degree?

- What are my expectations for this degree?

- What courses or program features excite me the most?

- Where do I want this degree to take me, professionally and personally?

- How will my unique professional and personal experiences add value to the program?

Jot these responses down to get your initial thoughts on paper. This will act as your starting point that you’ll use to create an outline and your first draft.

2. Develop an outline.

Next, you’ll want to take the ideas that you’ve identified during the brainstorming process and plug them into an outline that will guide your writing.

An effective outline for your statement of purpose might look something like this:

- An attention-grabbing hook

- A brief introduction of yourself and your background as it relates to your motivation behind applying to graduate school

- Your professional goals as they relate to the program you’re applying to

- Why you’re interested in the specific school and what you can bring to the table

- A brief summary of the information presented in the body that emphasizes your qualifications and compatibility with the school

An outline like the one above will give you a roadmap to follow so that your statement of purpose is well-organized and concise.

3. Write the first draft.

Your statement of purpose should communicate who you are and why you are interested in a particular program, but it also needs to be positioned in a way that differentiates you from other applicants.

Admissions professionals already have your transcripts, resumé, and test scores; the statement of purpose is your chance to tell your story in your own words.

When you begin drafting content, make sure to:

- Provide insight into what drives you , whether that’s professional advancement, personal growth, or both.

- Demonstrate your interest in the school by addressing the unique features of the program that interest you most. For Northeastern, he says, maybe it’s experiential learning; you’re excited to tackle real-world projects in your desired industry. Or perhaps it’s learning from faculty who are experts in your field of study.

- Be yourself. It helps to keep your audience in mind while writing, but don’t forget to let your personality shine through. It’s important to be authentic when writing your statement to show the admissions committee who you are and why your unique perspective will add value to the program.

4. Edit and refine your work.

Before you submit your statement of purpose:

- Make sure you’ve followed all directions thoroughly , including requirements about margins, spacing, and font size.

- Proofread carefully for grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

- Remember that a statement of purpose should be between 500 and 1,000 words. If you’ve written far more than this, read through your statement again and edit for clarity and conciseness. Less is often more; articulate your main points strongly and get rid of any “clutter.”

- Walk away and come back later with a fresh set of eyes. Sometimes your best ideas come when you’re not sitting and staring at your computer.

- Ask someone you trust to read your statement before you submit it.

Making a Lasting Impression

Your statement of purpose can leave a lasting impression if done well, Pierce says. It provides you with the opportunity to highlight your unique background and skills so that admissions professionals understand why you’re the ideal candidate for the program that you’re applying to. If nothing else, stay focused on what you uniquely bring to the classroom, the program, and the campus community. If you do that, you’ll excel.

To learn more tricks and tips for submitting an impressive graduate school application, explore our related Grad School Success articles .

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in March 2017. It has since been updated for thoroughness and accuracy.

Subscribe below to receive future content from the Graduate Programs Blog.

About shayna joubert, related articles.

Why Earn a Professional Doctoral Degree?

5 Tips to Get the Most out of Grad School

Is Earning a Graduate Certificate Worth It?

Did you know.

Advanced degree holders earn a salary an average 25% higher than bachelor's degree holders. (Economic Policy Institute, 2021)

Northeastern University Graduate Programs

Explore our 200+ industry-aligned graduate degree and certificate programs.

Most Popular:

Tips for taking online classes: 8 strategies for success, public health careers: what can you do with an mph, 7 international business careers that are in high demand, edd vs. phd in education: what’s the difference, 7 must-have skills for data analysts, in-demand biotechnology careers shaping our future, the benefits of online learning: 8 advantages of online degrees, the best of our graduate blog—right to your inbox.

Stay up to date on our latest posts and university events. Plus receive relevant career tips and grad school advice.

By providing us with your email, you agree to the terms of our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

Keep Reading:

The 8 Highest-Paying Master’s Degrees in 2024

Graduate School Application Tips & Advice

How To Get a Job in Emergency Management

Join Us at Northeastern’s Virtual Graduate Open House | March 5–7, 2024

Understanding Your Purpose

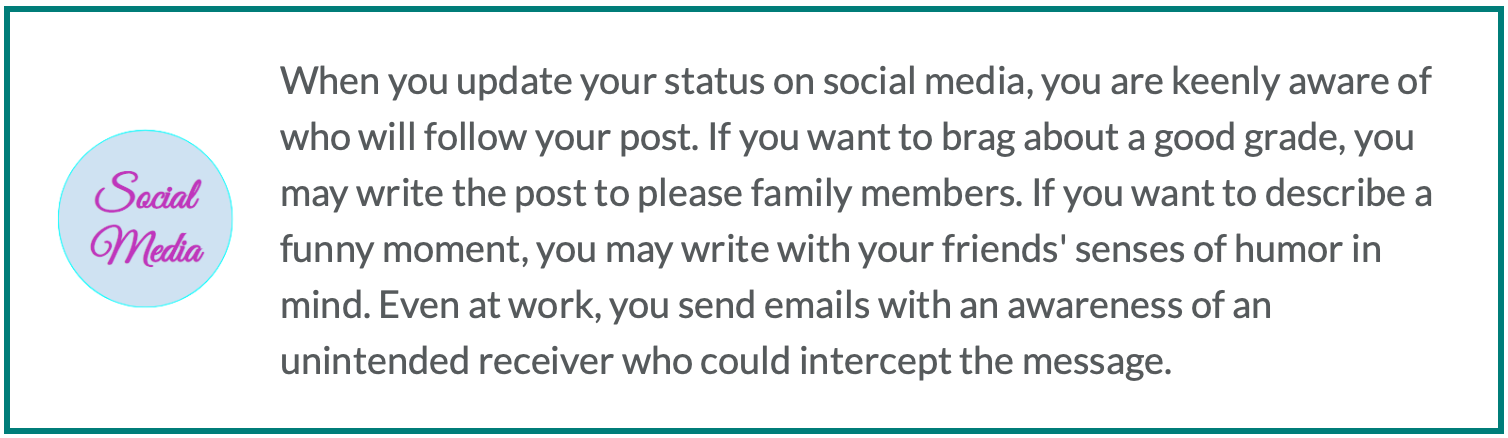

The first question for any writer should be, "Why am I writing?" "What is my goal or my purpose for writing?" For many writing contexts, your immediate purpose may be to complete an assignment or get a good grade. But the long-range purpose of writing is to communicate to a particular audience. In order to communicate successfully to your audience, understanding your purpose for writing will make you a better writer.

A Definition of Purpose

Purpose is the reason why you are writing . You may write a grocery list in order to remember what you need to buy. You may write a laboratory report in order to carefully describe a chemistry experiment. You may write an argumentative essay in order to persuade someone to change the parking rules on campus. You may write a letter to a friend to express your excitement about her new job.

Notice that selecting the form for your writing (list, report, essay, letter) is one of your choices that helps you achieve your purpose. You also have choices about style, organization, kinds of evidence that help you achieve your purpose

Focusing on your purpose as you begin writing helps you know what form to choose, how to focus and organize your writing, what kinds of evidence to cite, how formal or informal your style should be, and how much you should write.

Types of Purpose

Don Zimmerman, Journalism and Technical Communication Department I look at most scientific and technical writing as being either informational or instructional in purpose. A third category is documentation for legal purposes. Most writing can be organized in one of these three ways. For example, an informational purpose is frequently used to make decisions. Memos, in most circles, carry key information.

When we communicate with other people, we are usually guided by some purpose, goal, or aim. We may want to express our feelings. We may want simply to explore an idea or perhaps entertain or amuse our listeners or readers. We may wish to inform people or explain an idea. We may wish to argue for or against an idea in order to persuade others to believe or act in a certain way. We make special kinds of arguments when we are evaluating or problem solving . Finally, we may wish to mediate or negotiate a solution in a tense or difficult situation.

Remember, however, that often writers combine purposes in a single piece of writing. Thus, we may, in a business report, begin by informing readers of the economic facts before we try to persuade them to take a certain course of action.

In expressive writing, the writer's purpose or goal is to put thoughts and feelings on the page. Expressive writing is personal writing. We are often just writing for ourselves or for close friends. Usually, expressive writing is informal, not intended for outside readers. Journal writing, for example, is usually expressive writing.

However, we may write expressively for other readers when we write poetry (although not all poetry is expressive writing). We may write expressively in a letter, or we may include some expressive sentences in a formal essay intended for other readers.

Entertaining

As a purpose or goal of writing, entertaining is often used with some other purpose--to explain, argue, or inform in a humorous way. Sometimes, however, entertaining others with humor is our main goal. Entertaining may take the form of a brief joke, a newspaper column, a television script or an Internet home page tidbit, but its goal is to relax our reader and share some story of human foibles or surprising actions.

Writing to inform is one of the most common purposes for writing. Most journalistic writing fits this purpose. A journalist uncovers the facts about some incident and then reports those facts, as objectively as possible, to his or her readers. Of course, some bias or point-of-view is always present, but the purpose of informational or reportorial writing is to convey information as accurately and objectively as possible. Other examples of writing to inform include laboratory reports, economic reports, and business reports.

Writing to explain, or expository writing, is the most common of the writing purposes. The writer's purpose is to gather facts and information, combine them with his or her own knowledge and experience, and clarify for some audience who or what something is , how it happened or should happen, and/or why something happened .

Explaining the whos, whats, hows, whys, and wherefores requires that the writer analyze the subject (divide it into its important parts) and show the relationship of those parts. Thus, writing to explain relies heavily on definition, process analysis, cause/effect analysis, and synthesis.

Explaining versus Informing : So how does explaining differ from informing? Explaining goes one step beyond informing or reporting. A reporter merely reports what his or her sources say or the data indicate. An expository writer adds his or her particular understanding, interpretation, or thesis to that information. An expository writer says this is the best or most accurate definition of literacy, or the right way to make lasagne, or the most relevant causes of an accident.

An arguing essay attempts to convince its audience to believe or act in a certain way. Written arguments have several key features:

- A debatable claim or thesis . The issue must have some reasonable arguments on both (or several) sides.

- A focus on one or more of the four types of claims : Claim of fact , claim of cause and effect , claim of value , and/or claim of policy (problem solving).

- A fair representation of opposing arguments combined with arguments against the opposition and for the overall claim.

- An argument based on evidence presented in a reasonable tone . Although appeals to character and to emotion may be used, the primary appeal should be to the reader's logic and reason.

Although the terms argument and persuasion are often used interchangeably, the terms do have slightly different meanings. Argument is a special kind of persuasion that follows certain ground rules. Those rules are that opposing positions will be presented accurately and fairly, and that appeals to logic and reason will be the primary means of persuasion. Persuasive writing may, if it wishes, ignore those rules and try any strategy that might work. Advertisements are a good example of persuasive writing. They usually don't fairly represent the competing product, and they appeal to image, to emotion, to character, or to anything except logic and the facts--unless those facts are in the product's favor.

Writing to evaluate a person, product, thing, or policy is a frequent purpose for writing. An evaluation is really a specific kind of argument: it argues for the merits of the subject and presents evidence to support the claim. A claim of value --the thesis in an evaluation--must be supported by criteria (the appropriate standards of judgment) and supporting evidence (the facts, statistics, examples, or testimonials).

Writers often use a three-column log to set up criteria for their subject, collect relevant evidence, and reach judgments that support an overall claim of value. Writing a three-column log is an excellent way to organize an evaluative essay. First, think about your possible criteria. Remember: criteria are the standards of judgment (the ideal case) against which you will measure your particular subject. Choose criteria which your readers will find valid, fair, and appropriate . Then, collect evidence for each of your selected criteria. Consider the following example of a restaurant evaluation:

Overall claim of value : This Chinese restaurant provides a high quality dining experience.

Problem Solving

Problem solving is a special kind of arguing essay: the writer's purpose is to persuade his audience to adopt a solution to a particular problem. Often called "policy" essays because they recommend the readers adopt a policy to resolve a problem, problem-solving essays have two main components: a description of a serious problem and an argument for specific recommendations that will solve the problem .

The thesis of a problem-solving essay becomes a claim of policy : If the audience follows the suggested recommendations, the problem will be reduced or eliminated. The essay must support the policy claim by persuading readers that the recommendations are feasible, cost-effective, efficient, relevant to the situation, and better than other possible alternative solutions.

Traditional argument , like a debate, is confrontational. The argument often becomes a kind of "war" in which the writer attempts to "defeat" the arguments of the opposition.

Non-traditional kinds of argument use a variety of strategies to reduce the confrontation and threat in order to open up the debate.

- Mediated argument follows a plan used successfully in labor negotiations to bring opposing parties to agreement. The writer of a mediated argument provides a middle position that helps negotiate the differences of the opposing positions.

- Rogerian argumen t also wishes to reduce confrontation by encouraging mutual understanding and working toward common ground and a compromise solution.

- Feminist argument tries to avoid the patriarchal conventions in traditional argument by emphasizing personal communication, exploration, and true understanding.

Combining Purposes

Often, writers use multiple purposes in a single piece of writing. An essay about illiteracy in America may begin by expressing your feelings on the topic. Then it may report the current facts about illiteracy. Finally, it may argue for a solution that might correct some of the social conditions that cause illiteracy. The ultimate purpose of the paper is to argue for the solution, but the writer uses these other purposes along the way.

Similarly, a scientific paper about gene therapy may begin by reporting the current state of gene therapy research. It may then explain how a gene therapy works in a medical situation. Finally, it may argue that we need to increase funding for primary research into gene therapy.

Purposes and Strategies

A purpose is the aim or goal of the writer or the written product; a strategy is a means of achieving that purpose. For example, our purpose may be to explain something, but we may use definitions, examples, descriptions, and analysis in order to make our explanation clearer. A variety of strategies are available for writers to help them find ways to achieve their purpose(s).

Writers often use definition for key terms of ideas in their essays. A formal definition , the basis of most dictionary definitions, has three parts: the term to be defined, the class to which the term belongs, and the features that distinguish this term from other terms in the class.

Look at your own topic. Would definition help you analyze and explain your subject?

Illustration and Example

Examples and illustrations are a basic kind of evidence and support in expository and argumentative writing.

In her essay about anorexia nervosa, student writer Nancie Brosseau uses several examples to develop a paragraph:

Another problem, lying, occurred most often when my parents tried to force me to eat. Because I was at the gym until around eight o'clock every night, I told my mother not to save me dinner. I would come home and make a sandwich and feed it to my dog. I lied to my parents every day about eating lunch at school. For example, I would bring a sack lunch and sell it to someone and use the money to buy diet pills. I always told my parents that I ate my own lunch.

Look at your own topic. What examples and illustrations would help explain your subject?

Classification

Classification is a form of analyzing a subject into types. We might classify automobiles by types: Trucks, Sport Utilities, Sedans, Sport Cars. We can (and do) classify college classes by type: Science, Social Science, Humanities, Business, Agriculture, etc.

Look at your own topic. Would classification help you analyze and explain your subject?

Comparison and Contrast

Comparison and contrast can be used to organize an essay. Consider whether either of the following two outlines would help you organize your comparison essay.

Block Comparison of A and B

- Intro and Thesis

- Description of A

- Description of B (and how B is similar to/different from A)

Alternating Comparison of A and B

- Aspect One: Comparison/contrast of A and B

- Aspect Two: Comparison/contrast of A and B

- Aspect Three: Comparison/contrast of A and B

Look at your own topic. Would comparison/contrast help you organize and explain your subject?

Analysis is simply dividing some whole into its parts. A library has distinct parts: stacks, electronic catalog, reserve desk, government documents section, interlibrary loan desk, etc. If you are writing about a library, you may need to know all the parts that exist in that library.

Look at your own topic. Would analysis of the parts help you understand and explain your subject?

Description

Although we usually think of description as visual, we may also use other senses--hearing, touch, feeling, smell-- in our attempt to describe something for our readers.

Notice how student writer Stephen White uses multiple senses to describe Anasazi Indian ruins at Mesa Verde:

I awoke this morning with a sense of unexplainable anticipation gnawing away at the back of my mind, that this chilly, leaden day at Mesa Verde would bring something new . . . . They are a haunting sight, these broken houses, clustered together down in the gloom of the canyon. The silence is broken only by the rush of the wind in the trees and the trickling of a tiny stream of melting snow springing from ledge to ledge. This small, abandoned village of tiny houses seems almost as the Indians left it, reduced by the passage of nearly a thousand years to piles of rubble through which protrude broken red adobe walls surrounding ghostly jet black openings, undisturbed by modern man.

Look at your own topic. Would description help you explain your subject?

Process Analysis

Process analysis is analyzing the chronological steps in any operation. A recipe contains process analysis. First, sift the flour. Next, mix the eggs, milk, and oil. Then fold in the flour with the eggs, milk and oil. Then add baking soda, salt and spices. Finally, pour the pancake batter onto the griddle.

Look at your own topic. Would process analysis help you analyze and explain your subject?

Narration is possibly the most effective strategy essay writers can use. Readers are quickly caught up in reading any story, no matter how short it is. Writers of exposition and argument should consider where a short narrative might enliven their essay. Typically, this narrative can relate some of your own experiences with the subject of your essay. Look at your own topic. Where might a short narrative help you explain your subject?

Cause/Effect Analysis

In cause and effect analysis, you map out possible causes and effects. Two patterns for doing cause/effect analysis are as follows:

Several causes leading to single effect: Cause 1 + Cause 2 + Cause 3 . . . => Effect

One cause leading to multiple effects: Cause => Effect 1 + Effect 2 + Effect 3 ...

Look at your own topic. Would cause/effect analysis help you understand and explain your subject?

How Audience and Focus Affect Purpose

All readers have expectations. They assume what they read will meet their expectations. As a writer, your job is to make sure those expectations are met, while at the same time, fulfilling the purpose of your writing.

Once you have determined what type of purpose best conveys your motivations, you will then need to examine how this will affect your readers. Perhaps you are explaining your topic when you really should be convincing readers to see your point. Writers and readers may approach a topic with conflicting purposes. Your job, as a writer, is to make sure both are being met.

Purpose and Audience

Often your audience will help you determine your purpose. The beliefs they hold will tell you whether or not they agree with what you have to say. Suppose, for example, you are writing to persuade readers against Internet censorship. Your purpose will differ depending on the audience who will read your writing.

Audience One: Internet Users

If your audience is computer users who surf the net daily, you could appear foolish trying to persuade them to react against Internet censorship. It's likely they are already against such a movement. Instead, they might expect more information on the topic.

Audience Two: Parents

If your audience is parents who don't want their small children surfing the net, you'll need to convince them that censorship is not the solution to the problem. You should persuade this audience to consider other options.

Purpose and Focus

Your focus (otherwise known as thesis, claim, main idea, or problem statement) is a reflection of your purpose. If these two do not agree, you will not accomplish what you set out to do. Consider the following examples below:

Focus One: Informing

Suppose your purpose is to inform readers about relationships between Type A personalities and heart attacks. Your focus could then be: Type A personalities do not have an abnormally high risk of suffering heart attacks.

Focus Two: Persuading

Suppose your purpose is to persuade readers not to quarantine AIDS victims. Your focus could then be: Children afflicted with AIDS should not be prevented from attending school.

Writer and Reader Goals

Kate Kiefer, English Department Readers and writers both have goals when they engage in reading and writing. Writers typically define their goals in several categories-to inform, persuade, entertain, explore. When writers and readers have mutually fulfilling goals-to inform and to look for information-then writing and reading are most efficient. At times, these goals overlap one another. Many readers of science essays are looking for science information when they often get science philosophy. This mismatch of goals tends to leave readers frustrated, and if they communicate that frustration to the writer, then the writer feels misunderstood or unsuccessful.

Donna Lecourt, English Department Whatever reality you are writing within, whatever you chose to write about, implies a certain audience as well as your purpose for writing. You decide you have something to write about, or something you care about, then purpose determines audience.

Writer Versus Reader Purposes

Steve Reid, English Department A general definition of purpose relates to motivation. For instance, "I'm angry, and that's why I'm writing this." Purposes, in academic writing, are intentions the writer hopes to accomplish with a particular audience. Often, readers discover their own purpose within a text. While the writer may have intended one thing, the text actually does another, according to its readers.

Purpose and Writing Assignments

Instructors often state the purpose of a writing assignment on the assignment sheet. By carefully examining what it is you are asked to do, you can determine what your writing's purpose is.

Most assignment sheets ask you to perform a specific task. Key words listed on the assignment can help you determine why you are writing. If your instructor has not provided an assignment sheet, consider asking what the purpose of the assignment is.

Read over your assignment sheet. Make a note of words asking you to follow a specific task. For example, words such as:

These words require you to write about a topic in a specific way. Once you know the purpose of your writing, you can begin planning what information is necessary for that purpose.

Example Assignment

Imagine you are an administrator for the school district. In light of the Columbus controversy, you have been assigned to write a set of guidelines for teaching about Columbus in the district's elementary and junior high schools. These guidelines will explain official policy to parents and teachers in teaching children about Columbus and the significance of his voyages. They will also draw on arguments made on both sides of the controversy, as well as historical facts on which both sides agree.

The purpose of this assignment is to explain the official policy about teaching Columbus' voyages to parents and teachers.

Steve Reid, English Department Keywords in writing assignments give teachers and students direction about why we are writing. For instance, many assignments ask students to "describe" something. The word "describe" specifically indicated the writer is supposed to describe something visually. This is very general. Often, assignments are looking for something more specific. Maybe there is an argument the instructor intends be formulated. Maybe there is an implied thesis, but often teachers use general words such as "Write about" or "Describe" something, when they should use more specific words like, "Define" or "Explain" or "Argue" or "Persuade."

Purpose and Thesis

Writers choose from a variety of purposes for writing. They may write to express their thoughts in a personal letter, to explain concepts in a physics class, to explore ideas in a philosophy class, or to argue a point in a political science class.

Once they have their purpose in mind (and an audience for whom they are writing), writers may more clearly formulate their thesis. The thesis , claim , or main idea of an essay is related to the purpose. It is the sentence or sentences that fulfill the purpose and that state the exact point of the essay.

For example, if a writer wants to argue that high schools should strengthen foreign language training, her thesis sentence might be as follows:

"Because Americans are so culturally isolated, we need a national policy that supports increased foreign language instruction in elementary and secondary schools."

How Thesis is Related to Purpose

The following examples illustrate how subject, purpose and thesis are related. The subject is the most general statement of the topic. The purpose narrows the focus by indicating whether the writer wishes to express or explore ideas or actually explain or argue about the topic. The thesis sentence, claim, or main idea narrows the focus even farther. It is the sentence or sentences which focuses the topic for the writer and the reader.

Reid, Stephen, & Dawn Kowalski. (1995). Understanding Your Purpose. Writing@CSU . https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=94

How to Write a Purpose Statement (Templates, Examples)

By Status.net Editorial Team on September 30, 2023 — 15 minutes to read

- Key Elements of a Purpose Statement Part 1

- How to Write a Purpose Statement Step-by-Step Part 2

- Identifying Your Goals Part 3

- Defining Your Audience Part 4

- Outlining Your Methods Part 5

- Stating the Expected Outcomes Part 6

- Purpose Statement Example for a Research Paper Part 7

- Purpose Statement Example For Personal Goals Part 8

- Purpose Statement Example For Business Objectives Part 9

- Purpose Statement Example For an Essay Part 10

- Purpose Statement Example For a Proposal Part 11

- Purpose Statement Example For a Report Part 12

- Purpose Statement Example For a Project Part 13

- Purpose Statement Templates Part 14

A purpose statement is a vital component of any project, as it sets the tone for the entire piece of work. It tells the reader what the project is about, why it’s important, and what the writer hopes to achieve.

Part 1 Key Elements of a Purpose Statement

When writing a purpose statement, there are several key elements that you should keep in mind. These elements will help you to create a clear, concise, and effective statement that accurately reflects your goals and objectives.

1. The Problem or Opportunity

The first element of a purpose statement is the problem or opportunity that you are addressing. This should be a clear and specific description of the issue that you are trying to solve or the opportunity that you are pursuing.

2. The Target Audience

The second element is the target audience for your purpose statement. This should be a clear and specific description of the group of people who will benefit from your work.

3. The Solution

The third element is the solution that you are proposing. This should be a clear and specific description of the action that you will take to address the problem or pursue the opportunity.

4. The Benefits

The fourth element is the benefits that your solution will provide. This should be a clear and specific description of the positive outcomes that your work will achieve.

5. The Action Plan

The fifth element is the action plan that you will follow to implement your solution. This should be a clear and specific description of the steps that you will take to achieve your goals.

Part 2 How to Write a Purpose Statement Step-by-Step

Writing a purpose statement is an essential part of any research project. It helps to clarify the purpose of your study and provides direction for your research. Here are some steps to follow when writing a purpose statement:

- Start with a clear research question: The first step in writing a purpose statement is to have a clear research question. This question should be specific and focused on the topic you want to research.

- Identify the scope of your study: Once you have a clear research question, you need to identify the scope of your study. This involves determining what you will and will not include in your research.

- Define your research objectives: Your research objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. They should also be aligned with your research question and the scope of your study.

- Determine your research design: Your research design will depend on the nature of your research question and the scope of your study. You may choose to use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods approach.

- Write your purpose statement: Your purpose statement should be a clear and concise statement that summarizes the purpose of your study. It should include your research question, the scope of your study, your research objectives, and your research design.

Research question: What are the effects of social media on teenage mental health?

Scope of study: This study will focus on teenagers aged 13-18 in the United States.

Research objectives: To determine the prevalence of social media use among teenagers, to identify the types of social media used by teenagers, to explore the relationship between social media use and mental health, and to provide recommendations for parents, educators, and mental health professionals.

Research design: This study will use a mixed-methods approach, including a survey and interviews with teenagers and mental health professionals.

Purpose statement: The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of social media on teenage mental health among teenagers aged 13-18 in the United States. The study will use a mixed-methods approach, including a survey and interviews with teenagers and mental health professionals. The research objectives are to determine the prevalence of social media use among teenagers, to identify the types of social media used by teenagers, to explore the relationship between social media use and mental health, and to provide recommendations for parents, educators, and mental health professionals.

Part 3 Section 1: Identifying Your Goals

Before you start writing your purpose statement, it’s important to identify your goals. To do this, ask yourself the following questions:

- What do I want to achieve?

- What problem do I want to solve?

- What impact do I want to make?

Once you have a clear idea of your goals, you can start crafting your purpose statement. Your purpose statement should be a clear and concise statement that outlines the purpose of your work.

For example, if you’re writing a purpose statement for a business, your statement might look something like this:

“Our purpose is to provide high-quality products and services that improve the lives of our customers and contribute to the growth and success of our company.”

If you’re writing a purpose statement for a non-profit organization, your statement might look something like this:

“Our purpose is to improve the lives of underserved communities by providing access to education, healthcare, and other essential services.”

Remember, your purpose statement should be specific, measurable, and achievable. It should also be aligned with your values and goals, and it should inspire and motivate you to take action.

Part 4 Section 2: Defining Your Audience

Once you have established the purpose of your statement, it’s important to consider who your audience is. The audience for your purpose statement will depend on the context in which it will be used. For example, if you’re writing a purpose statement for a research paper, your audience will likely be your professor or academic peers. If you’re writing a purpose statement for a business proposal, your audience may be potential investors or clients.

Defining your audience is important because it will help you tailor your purpose statement to the specific needs and interests of your readers. You want to make sure that your statement is clear, concise, and relevant to your audience.

To define your audience, consider the following questions:

- Who will be reading your purpose statement?

- What is their level of knowledge or expertise on the topic?

- What are their needs and interests?

- What do they hope to gain from reading your purpose statement?

Once you have a clear understanding of your audience, you can begin to craft your purpose statement with their needs and interests in mind. This will help ensure that your statement is effective in communicating your goals and objectives to your readers.

For example, if you’re writing a purpose statement for a research paper on the effects of climate change on agriculture, your audience may be fellow researchers in the field of environmental science. In this case, you would want to make sure that your purpose statement is written in a way that is clear and concise, using technical language that is familiar to your audience.

Or, if you’re writing a purpose statement for a business proposal to potential investors, your audience may be less familiar with the technical aspects of your project. In this case, you would want to make sure that your purpose statement is written in a way that is easy to understand, using clear and concise language that highlights the benefits of your proposal.

The key to defining your audience is to put yourself in their shoes and consider what they need and want from your purpose statement.

Part 5 Section 3: Outlining Your Methods

After you have identified the purpose of your statement, it is time to outline your methods. This section should describe how you plan to achieve your goal and the steps you will take to get there. Here are a few tips to help you outline your methods effectively:

- Start with a general overview: Begin by providing a brief overview of the methods you plan to use. This will give your readers a sense of what to expect in the following paragraphs.

- Break down your methods: Break your methods down into smaller, more manageable steps. This will make it easier for you to stay organized and for your readers to follow along.

- Use bullet points: Bullet points can help you organize your ideas and make your methods easier to read. Use them to list the steps you will take to achieve your goal.

- Be specific: Make sure you are specific about the methods you plan to use. This will help your readers understand exactly what you are doing and why.

- Provide examples: Use examples to illustrate your methods. This will make it easier for your readers to understand what you are trying to accomplish.

Part 6 Section 4: Stating the Expected Outcomes

After defining the problem and the purpose of your research, it’s time to state the expected outcomes. This is where you describe what you hope to achieve by conducting your research. The expected outcomes should be specific and measurable, so you can determine if you have achieved your goals.

It’s important to be realistic when stating your expected outcomes. Don’t make exaggerated or false claims, and don’t promise something that you can’t deliver. Your expected outcomes should be based on your research question and the purpose of your study.

Here are some examples of expected outcomes:

- To identify the factors that contribute to employee turnover in the company.

- To develop a new marketing strategy that will increase sales by 20% within the next year.

- To evaluate the effectiveness of a new training program for improving customer service.

- To determine the impact of social media on consumer behavior.

When stating your expected outcomes, make sure they align with your research question and purpose statement. This will help you stay focused on your goals and ensure that your research is relevant and meaningful.

In addition to stating your expected outcomes, you should also describe how you will measure them. This could involve collecting data through surveys, interviews, or experiments, or analyzing existing data from sources such as government reports or industry publications.

Part 7 Purpose Statement Example for a Research Paper

If you are writing a research paper, your purpose statement should clearly state the objective of your study. Here is an example of a purpose statement for a research paper:

The purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of social media on the mental health of teenagers in the United States.

This purpose statement clearly states the objective of the study and provides a specific focus for the research.

Part 8 Purpose Statement Example For Personal Goals

When writing a purpose statement for your personal goals, it’s important to clearly define what you want to achieve and why. Here’s a template that can help you get started:

“I want to [goal] so that [reason]. I will achieve this by [action].”

Example: “I want to lose 10 pounds so that I can feel more confident in my body. I will achieve this by going to the gym three times a week and cutting out sugary snacks.”

Remember to be specific and realistic when setting your goals and actions, and to regularly review and adjust your purpose statement as needed.

Part 9 Purpose Statement Example For Business Objectives

If you’re writing a purpose statement for a business objective, this template can help you get started:

[Objective] [Action verb] [Target audience] [Outcome or benefit]

Here’s an example using this template:

Increase online sales by creating a more user-friendly website for millennial shoppers.

This purpose statement is clear and concise. It identifies the objective (increase online sales), the action verb (creating), the target audience (millennial shoppers), and the outcome or benefit (a more user-friendly website).

Part 10 Purpose Statement Example For an Essay

“The purpose of this essay is to examine the causes and consequences of climate change, with a focus on the role of human activities, and to propose solutions that can mitigate its impact on the environment and future generations.”

This purpose statement clearly states the subject of the essay (climate change), what aspects will be explored (causes, consequences, human activities), and the intended outcome (proposing solutions). It provides a clear roadmap for the reader and sets the direction for the essay.

Part 11 Purpose Statement Example For a Proposal

“The purpose of this proposal is to secure funding and support for the establishment of a community garden in [Location], aimed at promoting sustainable urban agriculture, fostering community engagement, and improving local access to fresh, healthy produce.”

Why this purpose statement is effective:

- The subject of the proposal is clear: the establishment of a community garden.

- The specific goals of the project are outlined: promoting sustainable urban agriculture, fostering community engagement, and improving local access to fresh produce.

- The overall objective of the proposal is evident: securing funding and support.

Part 12 Purpose Statement Example For a Report

“The purpose of this report is to analyze current market trends in the electric vehicle (EV) industry, assess consumer preferences and buying behaviors, and provide strategic recommendations to guide [Company Name] in entering this growing market segment.”

- The subject of the report is provided: market trends in the electric vehicle industry.

- The specific goals of the report are analysis of market trends, assessment of consumer preferences, and strategic recommendations.

- The overall objective of the report is clear: providing guidance for the company’s entry into the EV market.

Part 13 Purpose Statement Example For a Project

“The purpose of this project is to design and implement a new employee wellness program that promotes physical and mental wellbeing in the workplace.”

This purpose statement clearly outlines the objective of the project, which is to create a new employee wellness program. The program is designed to promote physical and mental wellbeing in the workplace, which is a key concern for many employers. By implementing this program, the company aims to improve employee health, reduce absenteeism, and increase productivity. The purpose statement is concise and specific, providing a clear direction for the project team to follow. It highlights the importance of the project and its potential benefits for the company and its employees.

Part 14 Purpose Statement Templates

When writing a purpose statement, it can be helpful to use a template to ensure that you cover all the necessary components:

Template 1: To [action] [target audience] in order to [outcome]

This template is a straightforward way to outline your purpose statement. Simply fill in the blanks with the appropriate information:

- The purpose of […] is

- To [action]: What action do you want to take?

- [Target audience]: Who is your target audience?

- In order to [outcome]: What outcome do you hope to achieve?

For example:

- The purpose of our marketing campaign is to increase brand awareness among young adults in urban areas, in order to drive sales and revenue growth.

- The purpose of our employee training program is to improve customer service skills among our frontline staff, in order to enhance customer satisfaction and loyalty.

- The purpose of our new product launch is to expand our market share in the healthcare industry, by offering a unique solution to the needs of elderly patients with chronic conditions.

Template 2: This [project/product] is designed to [action] [target audience] by [method] in order to [outcome].