- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Making Small Farms More Sustainable — and Profitable

- Lino Miguel Dias,

- Robert S. Kaplan,

- Harmanpreet Singh

A case study of Better Life Farming, an innovative public-private partnership in India, Indonesia, and Bangladesh.

Smallholder farms provide a large proportion of food supply in developing economies, but 40% of these farmers live on less than U.S.$2/day. With a rapidly growing global population it is imperative to improve the productivity and security of farmers making up this sector. This article presents the results of Better Life Farming, an ecosystem that connects smallholder farmers in India, Indonesia, and Bangladesh to the capabilities, products, and services of corporations and NGOs.

More than 2 billion people currently live on about 550 million small farms, with 40% of them on incomes of less than U.S. $2 per day. Despite high rates of poverty and malnutrition, these smallholders produce food for more than 50% of the population in low-and middle-income countries, and they have to be part of any solution for achieving the 50% higher food production required to feed the world’s projected 2050 population of nearly 10 billion people.

- LD Lino Miguel Dias is Vice-President Smallholder Farming in the Crop Science Division at Bayer AG, a global pharmaceuticals and life sciences company based in Germany, and Invited Professor at University of Lisbon, Portugal.

- Robert S. Kaplan is a senior fellow and the Marvin Bower Professor of Leadership Development emeritus at Harvard Business School. He coauthored the McKinsey Award–winning HBR article “ Accounting for Climate Change ” (November–December 2021).

- HS Harmanpreet Singh is Smallholder Partnerships Lead for the Asia Pacific region at Bayer AG, a global pharmaceutical and life Sciences company.

Partner Center

Natural Farming: A Sustainable Approach to Agriculture and Environmental Conservation | Sociology UPSC | Triumph IAS

Table of Contents

Natural Farming

(relevant for geography section of general studies paper prelims/mains).

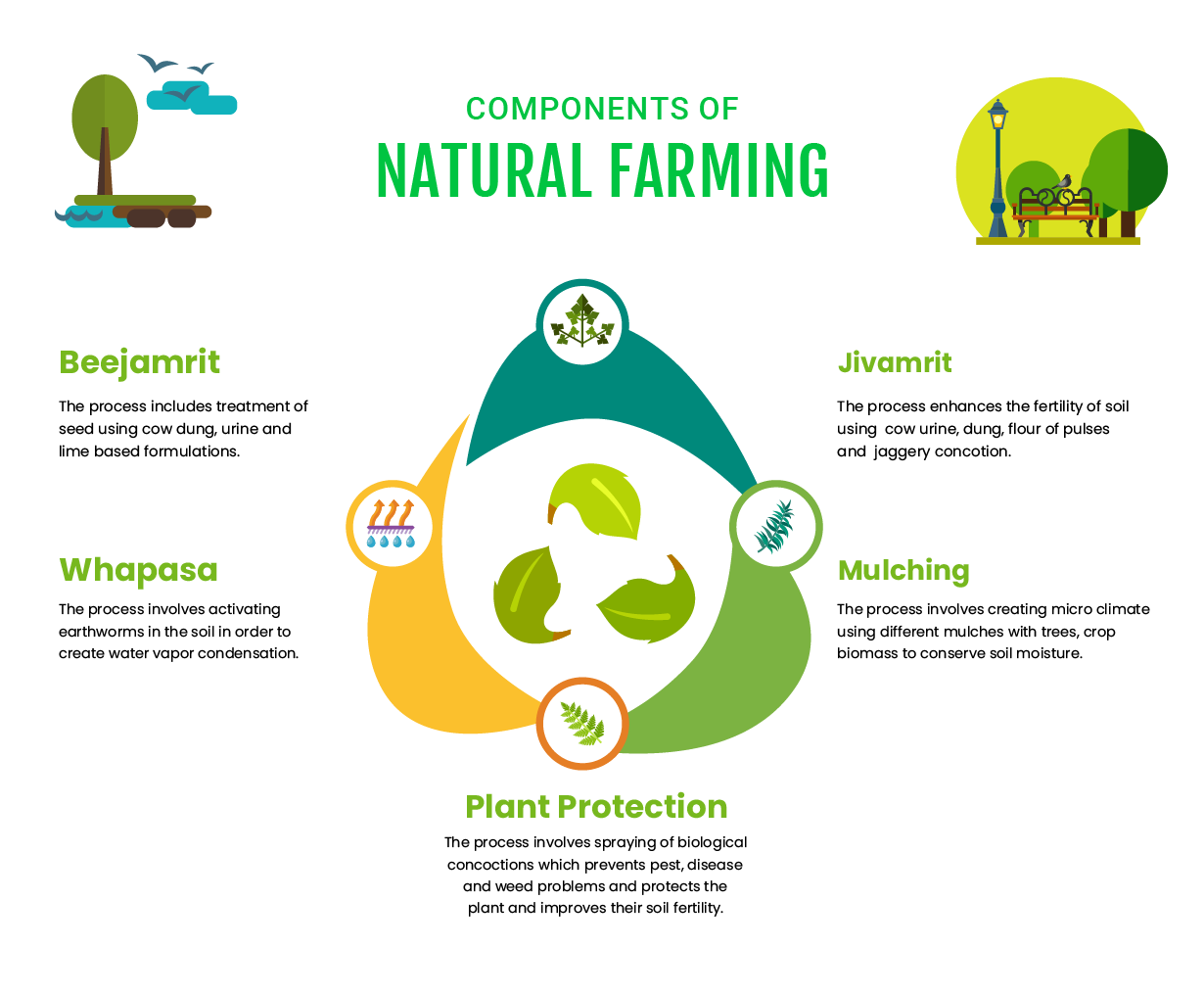

Natural Farming is both an art and a practice, and it’s progressively becoming a scientific endeavor focused on harmonizing with nature to attain higher outcomes with fewer resources. Nonetheless, this approach has often been linked to reduced crop yields and limited improvements in farmers’ incomes.

This agricultural approach was introduced by Masanobu Fukuoka, a Japanese farmer and philosopher, in his 1975 book ‘The One-Straw Revolution.’

It represents a diverse farming system that integrates crops, trees, and livestock, facilitating the optimal utilization of functional biodiversity.

Globally, Natural Farming is recognized as a type of regenerative agriculture, a prominent strategy for environmental conservation.

It offers the potential to not only increase farmers’ income but also contribute to soil fertility restoration, environmental well-being, and the mitigation or reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

This approach has the capability to effectively manage land practices and sequester carbon from the atmosphere into soils and plants, where it can be highly beneficial.

Several initiatives have been launched in this context:

- Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY)

- Sub-mission on AgroForestry (SMAF)

- National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA)

- Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yoj

Measures that can be taken to scale up Natural Farming

- Expanding Beyond the Ganga Basin: The focus should extend to the promotion of natural farming in rainfed regions beyond the Gangetic basin.

- Rainfed areas utilize only one-third of the fertilizers per hectare compared to irrigated regions, making the transition to chemical-free farming more feasible.

- Moreover, farmers in these regions can benefit significantly as current crop yields are comparatively low.

- Mitigating Risks for a Smooth Transition: To facilitate a seamless shift to chemical-free farming, farmers transitioning should be automatically enrolled in the government’s crop insurance scheme, PM Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY).

- Any change in agricultural practices, such as crop diversification or altered farming methods, introduces additional risks for farmers. Addressing these risks could encourage more farmers to embrace the transition.

- Supporting Agricultural Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (Agri MSMEs): The government should extend support to microenterprises that produce inputs for chemical-free agriculture.

- To tackle the challenge of the limited availability of natural inputs, the promotion of natural farming should go hand in hand with the establishment of village-level input preparation and sales shops. With two such shops in every village nationwide, it could provide livelihood opportunities for at least five million youth and women.

- Inspiration from Fellow Farmers: NGOs and exemplary farmers who have championed sustainable agriculture practices across the country can serve as inspirational figures.

- According to research by CEEW (Council on Energy, Environment, and Water) , approximately five million farmers are already engaged in some form of sustainable agriculture, with numerous NGOs actively promoting these practices.

- Learning from peers, especially exemplary farmers, through on-field demonstrations has proven highly effective in scaling up chemical-free agriculture in Andhra Pradesh.

- Leveraging Community-Based Institutions: Community institutions can play a pivotal role in raising awareness, inspiring others, and providing social support.

- The government should foster an environment where farmers can learn from and support each other during the transition.

- Beyond revising the curriculum in agricultural universities, there is a pressing need to enhance the skills of agricultural extension workers in sustainable farming practices.

Sample Question for UPSC Sociology Optional Paper:

Question 1 : What is the sociocultural impact of transitioning from conventional to Natural Farming ? Short Answer : The transition from conventional to Natural Farming can have a profound sociocultural impact by reinforcing traditional agricultural wisdom and community bonds, leading to a more sustainable and ecologically conscious society.

Question 2 : How does Natural Farming intersect with the concept of social capital? Short Answer : Natural Farming often involves community cooperation and shared knowledge, thereby enriching social capital by fostering community ties, trust, and mutual assistance.

Question 3 : What role do NGOs play in the promotion and scaling of Natural Farming in India? Short Answer : NGOs play a critical role in awareness-raising, training, and providing resources for Natural Farming, thereby serving as catalysts for its adoption and scalability.

Question 4 : Discuss the gender dimensions of Natural Farming . Short Answer : Natural Farming can empower women by involving them in decision-making processes and offering them opportunities in agricultural microenterprises, thereby improving gender equality in the sector.

Question 5 : How does Natural Farming contribute to rural development? Short Answer : Natural Farming can spur rural development by increasing farmers’ incomes, improving food security, restoring soil health, and generating employment opportunities, especially through Agri MSMEs.

To master these intricacies and fare well in the Sociology Optional Syllabus , aspiring sociologists might benefit from guidance by the Best Sociology Optional Teacher and participation in the Best Sociology Optional Coaching . These avenues provide comprehensive assistance, ensuring a solid understanding of sociology’s diverse methodologies and techniques.

Natural Farming, Sustainable Agriculture, Masanobu Fukuoka, Regenerative Agriculture, Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana, Sub-mission on AgroForestry, National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture, Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yoj, Soil Fertility, Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Rainfed Regions, Chemical-Free Farming, Agri MSMEs

Choose T he Best Sociology Optional Teacher for IAS Preparation?

At the beginning of the journey for Civil Services Examination preparation, many students face a pivotal decision – selecting their optional subject. Questions such as “ which optional subject is the best? ” and “ which optional subject is the most scoring? ” frequently come to mind. Choosing the right optional subject, like choosing the best sociology optional teacher , is a subjective yet vital step that requires a thoughtful decision based on facts. A misstep in this crucial decision can indeed prove disastrous.

Ever since the exam pattern was revamped in 2013, the UPSC has eliminated the need for a second optional subject. Now, candidates have to choose only one optional subject for the UPSC Mains , which has two papers of 250 marks each. One of the compelling choices for many has been the sociology optional. However, it’s strongly advised to decide on your optional subject for mains well ahead of time to get sufficient time to complete the syllabus. After all, most students score similarly in General Studies Papers; it’s the score in the optional subject & essay that contributes significantly to the final selection.

“ A sound strategy does not rely solely on the popular Opinion of toppers or famous YouTubers cum teachers. ”

It requires understanding one’s ability, interest, and the relevance of the subject, not just for the exam but also for life in general. Hence, when selecting the best sociology teacher, one must consider the usefulness of sociology optional coaching in General Studies, Essay, and Personality Test.

The choice of the optional subject should be based on objective criteria, such as the nature, scope, and size of the syllabus, uniformity and stability in the question pattern, relevance of the syllabic content in daily life in society, and the availability of study material and guidance. For example, choosing the best sociology optional coaching can ensure access to top-quality study materials and experienced teachers. Always remember, the approach of the UPSC optional subject differs from your academic studies of subjects. Therefore, before settling for sociology optional , you need to analyze the syllabus, previous years’ pattern, subject requirements (be it ideal, visionary, numerical, conceptual theoretical), and your comfort level with the subject.

This decision marks a critical point in your UPSC – CSE journey , potentially determining your success in a career in IAS/Civil Services. Therefore, it’s crucial to choose wisely, whether it’s the optional subject or the best sociology optional teacher . Always base your decision on accurate facts, and never let your emotional biases guide your choices. After all, the search for the best sociology optional coaching is about finding the perfect fit for your unique academic needs and aspirations.

To master these intricacies and fare well in the Sociology Optional Syllabus , aspiring sociologists might benefit from guidance by the Best Sociology Optional Teacher and participation in the Best Sociology Optional Coaching . These avenues provide comprehensive assistance, ensuring a solid understanding of sociology’s diverse methodologies and techniques. Sociology, Social theory, Best Sociology Optional Teacher, Best Sociology Optional Coaching, Sociology Optional Syllabus. Best Sociology Optional Teacher, Sociology Syllabus, Sociology Optional, Sociology Optional Coaching, Best Sociology Optional Coaching, Best Sociology Teacher, Sociology Course, Sociology Teacher, Sociology Foundation, Sociology Foundation Course, Sociology Optional UPSC, Sociology for IAS,

Follow us :

🔎 https://www.instagram.com/triumphias

🔎 www.triumphias.com

🔎https://www.youtube.com/c/TriumphIAS

https://t.me/VikashRanjanSociology

Find More Blogs

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 20 January 2020

Potential yield challenges to scale-up of zero budget natural farming

- Jo Smith ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6984-6766 1 ,

- Jagadeesh Yeluripati 2 ,

- Pete Smith ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3784-1124 1 &

- Dali Rani Nayak 1

Nature Sustainability volume 3 , pages 247–252 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

2311 Accesses

24 Citations

26 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Agriculture

- Developing world

- Environmental sciences

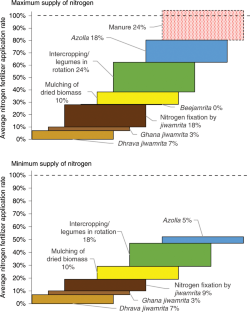

Under current trends, 60% of India’s population (>10% of people on Earth) will experience severe food deficiencies by 2050. Increased production is urgently needed, but high costs and volatile prices are driving farmers into debt. Zero budget natural farming (ZBNF) is a grassroots movement that aims to improve farm viability by reducing costs. In Andhra Pradesh alone, 523,000 farmers have converted 13% of productive agricultural area to ZBNF. However, sustainability of ZBNF is questioned because external nutrient inputs are limited, which could cause a crash in food production. Here, we show that ZBNF is likely to reduce soil degradation and could provide yield benefits for low-input farmers. Nitrogen fixation, either by free-living nitrogen fixers in soil or symbiotic nitrogen fixers in legumes, is likely to provide the major portion of nitrogen available to crops. However, even with maximum potential nitrogen fixation and release, only 52–80% of the national average nitrogen applied as fertilizer is expected to be supplied. Therefore, in higher-input systems, yield penalties are likely. Since biological fixation from the atmosphere is possible only with nitrogen, ZBNF could limit the supply of other nutrients. Further research is needed in higher-input systems to ensure that mass conversion to ZBNF does not limit India’s capacity to feed itself.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Optimal nitrogen rate strategy for sustainable rice production in China

Spatially differentiated nitrogen supply is key in a global food–fertilizer price crisis

Sustainability transition for Indian agriculture

Data availability.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. This is an analysis of existing data. All data were collated from literature sources as cited.

Code availability

The ORATOR model has been described and published previously (see Supplementary Information ) and will be made available from the corresponding author on request.

Foley, J. A. et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 478 , 337–342 (2011).

Article CAS Google Scholar

India Population Live (Worldometers, 2019); https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/india-population/

World Population Prospects, the 2012 Revision (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2013); https://go.nature.com/37N2olc

Ritchie, H., Reay, D. & Higgins, P. Sustainable food security in India—domestic production and macronutrient availability. PLoS ONE 13 , e0193766 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

Bruinsma, J. (ed.) World Agriculture: Towards 2015/2030. An FAO Perspective (Earthscan, 2003).

Agoramoorthy, G. Can India meet the increasing food demand by 2020? Futures 40 , 503–506 (2008).

Smith, P. Delivering food security without increasing pressure on land. Glob. Food Secur. 2 , 18–23 (2013).

Ray, D. K. et al. Climate change has likely already affected global food production. PLoS ONE 14 , e0217148 (2019).

Bhattacharyya, R. et al. Soil degradation in India: challenges and potential solutions. Sustainability 7 , 3528–3570 (2015).

Mythili, G. & Goedecke, J. in Economics of Land Degradation and Improvement—A Global Assessment for Sustainable Development (eds Nkonya, E. et al.) 431–469 (Springer, 2016); https://go.nature.com/2FERCkZ

United Nations Decade of Family Farming 2019–2028. Global Action Plan (FAO and IFAD, 2019); https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ca4672en.pdf

52 Profiles on Agroecology: Z ero Budget Natural Farming in India (FAO, 2019); http://www.fao.org/3/a-bl990e.pdf

Govt. should stop promoting zero budget natural farming pending proof: scientists. The Hindu (11 September 2019); https://go.nature.com/2FrKSH1

Sitharaman, N. Budget 2019–2020 speech. India Ministry of Finance (5 July 2019); https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budgetspeech.php

Sanhati Collective Farmer Suicides in India: A Policy-induced Disaster of Epic Proportions http://sanhati.com/excerpted/4504/ (2012).

Patel, V. et al. Suicide mortality in India: a nationally representative survey. Lancet 379 , 2343–2351 (2012).

Kennedy, J. & King, L. The political economy of farmers’ suicides in India: indebted cash-crop farmers with marginal landholdings explain state-level variation in suicide rates. Glob. Health 10 , 16 (2014).

Abhilash, P. C. & Singh, N. Pesticide use and application: an Indian scenario. J. Hazard. Mater. 165 , 1–12 (2009).

Kumari, S. & Sharma, H. The impact of pesticides on farmer’s health: a case study of fruit bowl of Himachal Pradesh. Int. J. Sci. Res. 3 , 144–148 (2012).

Google Scholar

Zero Budget Natural Farming http://apzbnf.in (RySS, Government of Andhra Pradesh, 2018).

Khadse, A. & Rosset, P. M. Zero budget natural farming in India—from inception to institutionalization. Agroecol. Sust. Food 43 , 848–871 (2019).

Statistical Abstract Andhra Pradesh 2015 (Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Government of Andhra Pradesh, 2016); https://desap.cgg.gov.in/jsp/website/gallery/Statistical%20Abstract%202015.pdf

RySS Zero Budget Natural Farming as A Nature-based Solution for Climate Action (UNEP, 2019); https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/28895?show=full

Report of the Global Environment Facility to the Fourteenth Session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (GEF, 2019); https://go.nature.com/2tzvntM

Patra, A. M. Accounting methane and nitrous oxide emissions, and carbon footprints of livestock food products in different states of India. J. Clean. Prod. 162 , 678–686 (2017).

Kumar, V. India—innovations in agroecology. Engineering transformation through zero budget natural farming (ZBNF). In Scaling Up Agroecology to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Proc. 2nd FAO International Symposium 250–251 (FAO, 2019) http://www.fao.org/3/BU710EN/bu710en.pdf

Palekar, S. Zero Budget Spiritual Farming http://palekarzerobudgetspiritualfarming.org (2019).

Ram, R. A., Singha, A. & Vaish, S. Microbial characterization of on-farm produced bio-enhancers used in organic farming. Indian J. Agr. Sci. 88 , 35–40 (2018).

CAS Google Scholar

App, A. A. et al. Nonsymbiotic nitrogen fixation associated with the rice plant in flooded soils. Soil Sci. 130 , 283–289 (1980).

Sreenivasa, M. N., Naik, N. & Bhat, S. N. Beejamrutha : a source for beneficial bacteria. Karnataka J. Agric. Sci. 22 , 1038–1040 (2009).

Rao, S. C. & Dao, T. H. Fertilizer placement and tillage effects of nitrogen assimilation by wheat. Agron. J. 84 , 1028–1032 (1992).

Erenstein, O. & Laxmi, V. Zero tillage impacts in India’s rice–wheat systems: a review. Soil Till. Res. 100 , 1–14 (2008).

Singh, A., Phogat, V. K., Dahiya, R. & Batra, S. D. Impact of long-term zero till wheat on soil physical properties and wheat productivity under rice–wheat cropping system. Soil Till. Res. 140 , 98–105 (2014).

Ram, A. R. Innovations in organic production of fruits and vegetables. Shodh Chintan 11 , 85–98 (2019).

National Crop Statistics (FAOSTAT, 2019); http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC

Fertilizer Use by Crop in India (FAO, 2005); http://www.fao.org/tempref/agl/agll/docs/fertuseindia.pdf

Hamshere, P., Sheng, Y., Moir, B., Gunning-Trant, C. & Mobsby, D. What India Wants: Analysis of India’s Food Demand to 2050 Report No. 14.16 (ABARES, 2014); http://agriculture.gov.au/abares/publications

Montanarella, L., Scholes, R. & Brainich, A. (eds) The IPBES Assessment Report on Land Degradation and Restoration (IPBES, 2018); www.ipbes.net

Hati, K. M., Swarup, A., Dwivedi, A. K., Misra, A. K. & Bandyopadhyay, K. K. Changes in soil physical properties and organic carbon status at the topsoil horizon of a vertisol of central India after 28 years of continuous cropping, fertilization and manuring. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 119 , 127–134 (2006).

Smith, J. et al. Treatment of organic resources before soil incorporation in semi-arid regions improves resilience to El Niño, and increases crop production and economic returns. Environ. Res. Lett. 14 , 085004 (2019).

Guidelines for Sustainable Manure Management in Asian Livestock Production Systems IAEA-TECDOC-1582 (IAEA, 2008); https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/TE_1582_web.pdf

Bradbury, N. J., Whitmore, A. P., Hart, P. B. S. & Jenkinson, D. S. Modelling the fate of nitrogen in crop and soil in the years following application of 15 N-labelled fertilizer to winter wheat. J. Agric. Sci. 121 , 363–379 (1993).

Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration in India. Climatic Change 65 , 277–296 (2004).

FAO World Development Indicators. Agricultural Land (% of Land Area)—India (World Bank, 2019); https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.ZS?locations=IN

Aggarwal, G. C. & Singh, N. T. Energy and economic returns from cattle dung manure as fuel. Energy 9 , 87–90 (1984).

Saxena, K. L. & Sewak, R. Livestock waste and its impact on human health. Int. J. Agric. Sci. 6 , 1084–1099 (2016).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Kumar, Z. Hussain and R. Nalavade of RySS for information, support while visiting sites and discussions. Funding for this work was provided by the Newton Bhabha Virtual Centre on Nitrogen Efficiency in Whole Cropping Systems (NEWS) project no. NEC 05724, the DFID-NERC El Niño programme in project NE P004830, ‘Building Resilience in Ethiopia’s Awassa Region to Drought’ (BREAD), the ESRC NEXUS programme in project IEAS/POO2501/1, ‘Improving Organic Resource Use in Rural Ethiopia’ (IPORE), and the GCRF South Asian Nitrogen Hub (NE/S009019/1). J.Y. was supported by the Scottish Government’s Rural and Environment Research and Analysis Directorate under the current Strategic Research Programme (2016–2021): Research Deliverable 1.1.3: Soils and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. The input of P.S. contributes to the UKRI-funded projects DEVIL (NE/M021327/1), Soils-R-GRREAT (NE/P019455/1) and N-Circle (BB/N013484/1), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme projects CIRCASA (grant agreement no. 774378) and UNISECO (grant agreement no. 773901), and the Wellcome Trust-funded project Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems (SHEFS).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Biological Science, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK

Jo Smith, Pete Smith & Dali Rani Nayak

Information and Computational Sciences, James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, UK

Jagadeesh Yeluripati

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

J.S. was primarily responsible for the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and the drafting of the manuscript. J.Y., P.S. and D.R.N. contributed towards the conception and design of the work and revision of the manuscript. D.R.N. also contributed to the creation of software used in the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jo Smith .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary notes 1–8, Tables 1–9, Figs. 1 and 2 and refs. 1–147.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Smith, J., Yeluripati, J., Smith, P. et al. Potential yield challenges to scale-up of zero budget natural farming. Nat Sustain 3 , 247–252 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0469-x

Download citation

Received : 04 October 2019

Accepted : 17 December 2019

Published : 20 January 2020

Issue Date : March 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0469-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Power-law productivity of highly biodiverse agroecosystems supports land recovery and climate resilience.

- Masatoshi Funabashi

npj Sustainable Agriculture (2024)

Microbial interactions shape cheese flavour formation

- Chrats Melkonian

- Francisco Zorrilla

- Ahmad A. Zeidan

Nature Communications (2023)

Shaping a resilient future in response to COVID-19

- Johan Rockström

- Albert V. Norström

Nature Sustainability (2023)

Natural farming improves crop yield in SE India when compared to conventional or organic systems by enhancing soil quality

- Sarah Duddigan

- Liz J. Shaw

- Chris D. Collins

Agronomy for Sustainable Development (2023)

Sustainable options for fertilizer management in agriculture to prevent water contamination: a review

- Arun Lal Srivastav

- Naveen Patel

- Vinod Kumar Chaudhary

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Anthropocene newsletter — what matters in anthropocene research, free to your inbox weekly.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, impact of natural farming cropping system on rural households—evidence from solan district of himachal pradesh, india.

- 1 Department of Social Sciences, Dr. YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Solan, India

- 2 Department of Seed Science and Technology, Dr. YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Solan, India

- 3 Department of Basic Sciences, Dr. YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Solan, India

- 4 Directorate of Research, Dr. YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Nauni, India

- 5 State Project Implementation Unit (SPIU), Shimla, India

- 6 Department of Biotechnology, Amity University, Noida, India

Natural farming, popularly known as zero budget natural farming, is an innovative farming approach. It is low input based, climate resilient, and low cost farming system because all the inputs (insect repellents, fungicides, and pesticides) are made up of natural herbs and locally available inputs, thereby reducing the use of artificial fertilizers and industrial pesticides. It is becoming increasingly popular among the smallholder farmers of Himachal Pradesh. Under the natural farming system, 3 to 12 crops are cultivated together on the same area, along with leguminous crops as intercrop in order to ensure that no piece of land is wasted and utilized properly. This article focuses mainly on the different cropping systems of natural farming and comparing the economics of natural farming (NF) with conventional farming (CF) systems. Study shows that farmers adopted five major crop combinations under natural farming system, i.e., vegetables-based cropping system (e.g., tomato + beans + cucumber and cauliflower + pea + radish), vegetables-cereals-based cropping system, and other three more cropping systems discussed in this article. The results indicated that a vegetable-based cropping system has 19.68% more net return in Kharif season and 24.64% more net return in Rabi season as compared to conventional farming vegetable-based monocropping system. NF maximizes land use and reduces the chance of crop yield loss. NF has resulted in increased returns especially in the vegetable cropping system where reduction in cost was 30.73 per cent (kharif) and 11.88 per cent (rabi) across all crop combinations in comparison to CF. It is found in study that NF was cost savings from not using chemical fertilizers and pesticides, as well as higher benefit from intercrops.

Introduction

For around 58% of India's population, agriculture is their major source of income. Agriculture, forestry, and fishery had a gross value added of Rs 19.48 lac crore (US$ 276.37 billion) in fiscal year 2020. In fiscal year (FY) 2020, agricultural and allied industries accounted for 17.8% of India's gross value added (GVA) at current prices. Consumer expenditure in India would increase by as much as 6.6% in 2021. India's share in world agricultural exports increased to 2.1% in 2019 from 1.71% in 2010 ( Ministry of Commerce, 2021 ).

The country achieved its remarkable agricultural growth in the 1960s, after the emergence of the Green Revolution. India marked a new era in Indian agricultural history. The Green Revolution technology aimed to increase agricultural production mainly by substituting typically hardy plant varieties with high-response varieties and hybrids, the use of fertilizers and plant protection chemicals, irrigating more cultivated land by investing heavily on large irrigation systems, and consolidation of agricultural holdings ( Sebby, 2010 ). India has gained its outstanding position in food production, but it is also facing a poor ranking in the hunger index ( Menon et al., 2008 ). The Green Revolution left its harmful footprints on Indian agriculture. The monocropping system, increased and frequent use of fertilizers and pesticides caused considerable damage to the soil's biological operation, crop diversity, increased cost of cultivation, deterioration of groundwater, loss of flora-fauna, increased human diseases, malnutrition, and decreased soil fertility, which have almost left it barren in large areas. As a consequence, farmers with small farms invest in these costly inputs, which are exposed to high monetary risks and push them in the debt cycle ( Eliazer et al., 2019 ). With pesticides' obvious environmental and ecological effects, it is no surprise that government laws have been strengthened ( Carrington, 2019 ). Furthermore, the possible health implications of pesticide residue have terrified many of us into choosing pesticide-free items. Even though rules exist to assure legal maximum residual levels that have been considered scientifically acceptable for food, the campaign to eliminate pesticides has gained traction. Restoring soil health by reverting to non-chemical agriculture has assumed great importance in achieving sustainability in production.

In India, a chemical-free and climate-resilient method of farming given by a scientist Subhash Palekar, during 2006 in Maharashtra to end the problems arising after the Green Revolution by introducing natural farming. His methods popularized when farmers started adopting his methods. After that, many researchers and scientists claimed that natural farming is a good alternative to chemical farming that directly or indirectly impacts sustainable development positively ( Tripathi and Tauseef, 2018 ). The aim of natural farming is to reduce the cost of production to almost zero and to come back to the “pre-Green Revolution” style of agriculture ( Khadse et al., 2017 ). This would seem to lead growers out of loans by putting a stop to agricultural chemicals practices. The central government has implemented a policy to encourage farming methods throughout India. The state governments of Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Kerala, and Karnataka asked Subhash Palekar to educate their farmers for natural farming ( Khadse and Rosset, 2019a , b ).

In order to promote natural farming in Himachal Pradesh, a scheme “Prakritik Kheti Khushhal Kisan” was initiated with a budget allocation of Rs 35 crore (2019–2020). Under this scheme, peasants will be supported with training, the required machinery, to achieve the objective of sustainable farming doubling farmers' incomes, improved soil fertility, and low input costs ( Vashishat et al., 2021 ). Though the search for a better alternative shall always remain, right now natural farming is a credible alternative itself ( Mishra, 2018 ).

Natural farming is a special form of agriculture that does not requires any financial expenditure to purchase the essential inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, and plant protection chemicals from the market. Natural farming, though in its preliminary stages, is showing increased positive results and is being adopted by farmers in good faith. It is even cited by farmers that labor and production costs have drastically reduced 14–45% ( Chandel et al., 2021 ).

The cropping system of natural farming focuses mainly on traditional Indian practices based on agroecology; natural farming absolutely requires no monetary investment for purchase of key inputs at all ( Palekar, 2005 ). Due to its simplicity, adaptiveness, and huge reduction in cost of cultivation to know the impact of the cropping system of natural farming on the small and marginal farmers, this study was conducted.

The objectives of this study will be:

i) To study the socioeconomic status of the farmers.

ii) To study the comparative economics of natural farming vis-à-vis conventional farming.

iii) To identify the constraints of natural farming.

Methodology

Selection of the study area and respondents.

Solan district of Himachal Pradesh was purposely selected for this study. The district comprises five development blocks, i.e., Dharampur, Kandaghat, Nalagarh, Solan, and Kunihar. Out of these, three blocks were selected randomly and a list of farmers practicing both the Subhash Palekar Natural Farming (SPNF) and conventional farming were procured from the Project Director ATMA, Solan. From the list, 20 farmers each from the three selected blocks were selected randomly. Thus, total samples of 60 farmers were selected for this study. The primary data were collected from the farmers practicing both the natural farming and conventional farming systems by survey method using a well-structured and pre-tested schedule (questionnaire).

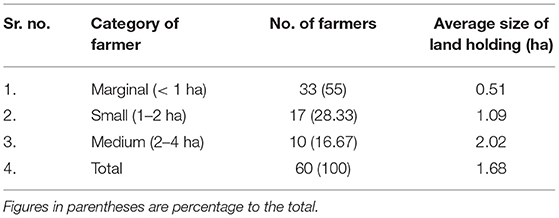

Distribution of Sampled Farmers Practicing Natural Farming According to Their Size of Landholding

For the analysis of data, the total respondents were divided according to the size of their landholdings into three classes, viz., marginal (<1 ha), small (1–2 ha), and medium (2–4 ha). The distribution of the sampled farmers is given in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Distribution of sampled households according to their landholdings.

Analytical Framework

To fulfill the above specified objectives of this study, based on the nature and extent of availability of data, the following analytical tools and techniques have been employed for the analysis of the data.

Tabular Analysis

Simple tabular analysis was used to examine socioeconomic status, resource structure, income and expenditure pattern, and farmers' opinions about the production and marketing problems under natural farming. Simple statistical tools such as averages and percentages were used to compare, contrast, and interpret the results. The sex ratio, literacy rate, and index were calculated using the following formulae:

W i = Weights (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) for illiterate, primary, middle, metric, secondary, and graduate and above, respectively.

X i = Number of persons in respective category.

Costs and Returns Analysis

Commission for agricultural costs and prices cost concepts.

Cost A 1 includes:

i) Cost of planting material cost

ii) Cost of manures, fertilizers, and plant protections

iii) Cost of hired human labor

iv) Cost of owned and hired machinery

v) Irrigation charges

vi) Depreciation on implements, farm buildings, and irrigation structures

vii) Land revenue

viii) Interest on owned working capital

ix) Other miscellaneous charges.

• Cost A 2 : Cost A 1 + rent paid for leased-in land

• Cost B 1 : Cost A 1 + interest on the fixed capital assets excluding land

• Cost B 2 : Cost B 1 + rental value of owned land

• Cost C 1 : Cost B 1 + imputed value of family labor

• Cost C 2 : Cost B 2 + imputed value of family labor

• Cost C 3 : Cost C 2 + 10% of cost C 2 on account of managerial function performed by the farmer.

Crop Equivalent Yield

In natural farming system, many types of crops were cultivated in a multiple or mixed cropping. So, it was very difficult to compare the economics of multiple crops with a single crop. Francis (1986) described crop equivalent yield (CEY) to the sum of equivalent principal and intercrop yields. The differing yield intercrops were transformed into the equivalent yield of any crop depending on the commodity price. So, a comparison was made based on economic returns and crop equivalent yield (CEY) of multiple cropping sequences was calculated by converting the yield of different intercrops/crops into equivalent yield of any one crop based on price of the produce. Mathematically, the CEY is represented as:

C Y = Yields of the main crop

P 0 = Price of the main crop

(C y1 , C y2 , C y3….. C yn ) = Yields of intercrop, which are to be converted to equivalent of main crop yield

(P 1 , P 2 , P 3 … P n ) = Price of the respective intercrops.

Relative Economic Efficiency

Farrell (1957) distinguished three types of efficiency, namely, technical efficiency, price or allocative efficiency, and economic efficiency (which is a combination of the first two). Economic efficiency is distinct from the other two efficiencies, even though it is the product of technical and allocative efficiencies. Relative economic efficiency, which is a comparative measure of economic gains, can be calculated by:

Statistical Analysis

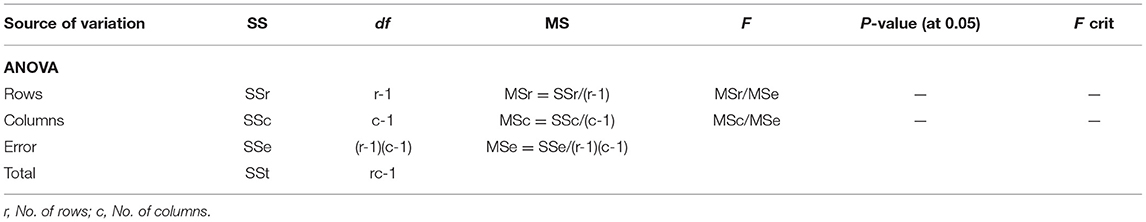

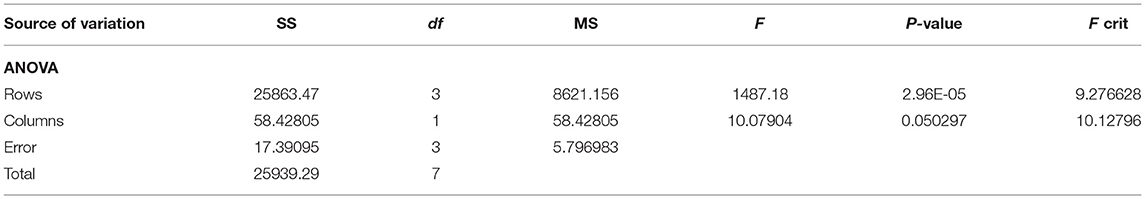

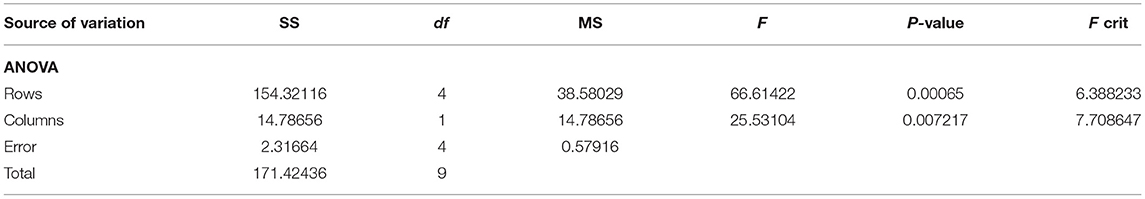

The comparative economics was statistically analyzed as per the procedure given by Gomez and Gomez (1984) . The ANOVA was carried out based on the model in Table 2 .

Table 2 . ANOVA (two-rowed without replication) layout.

Production and Marketing Problems

To study the various problems associated with the production and marketing of natural farming, it was assumed that the extent of a particular problem varies from place to place and farmer to farmer. The multiple responses of producers reporting various problems were taken into consideration for analysis.

Garrett's Ranking Technique

The Garrett's ranking technique ( Garrett and Woodworth, 1969 ) was used for examination of constraints. It is important to note here that these constraints were focused on the response of all the sample farmers. The respondents were asked to rank the problems in turmeric and cotton production, processing, and marketing. In the Garrett's ranking technique, these ranks were converted into percent position by using the formula:

R ij = Ranking given to the ith attribute by the jth individual

N j = Number of attributes ranked by the jth individual.

By referring to the Garrett's table, the percentage positions estimated were converted into scores. Thus, for each factor, the scores of the various respondents were added and the mean values were estimated. The mean values, thus, obtained for each of the attributes were arranged in descending order. The attributes with the highest mean value were considered as the most important one and the others followed in that order.

Chi-Squared Test

To test whether there was any significant difference among marginal, small and medium farms of Solan for the problems faced by them, chi-square test ( Pearson, 1900 ) in (m × n) contingency table was applied where m and n are the number of marketing problems faced by the farmers of natural farming in Solan district. The detail of approximate chi-squared test is given as under:

O = Observed values

E = Expected values

K = Number of problems

L = Number of the farm size groups.

Results and Discussion: Socio-Economic Characteristics of Sampled Households

Size and structure of the sampled households in the study area.

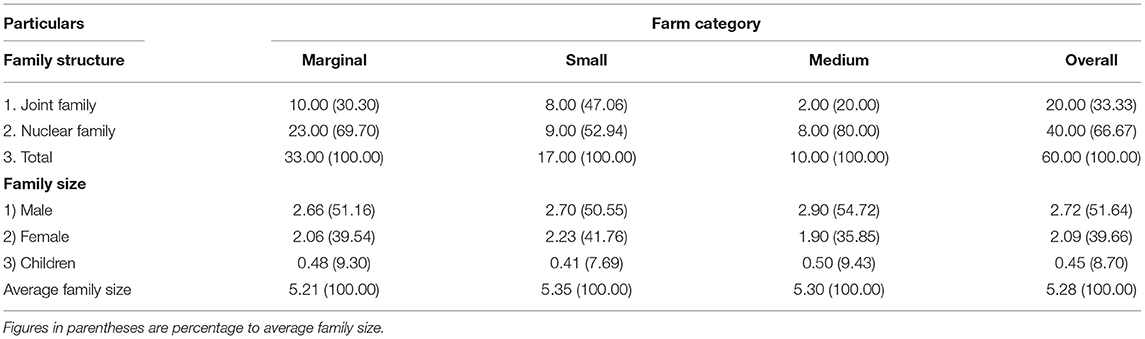

The size and structure of the family play an important part in influencing crop production. The size and structure of the sampled households in the study area are given in Table 3 . At an overall level, the average family size was 5.28 out of which 51.64% were males, 39.66% were females, and 8.70% were children. The average family size ranged from 5.21 to 5.35 and was observed highest in the small farmers (5.35) followed by medium farmers (5.30) and marginal farmers (5.21). The results indicated that the dominant family structure in the area under study was the nuclear family (66.67%). It was highest in small farms (47.06%) followed by marginal (30.30%) and medium farm categories (20%).

Table 3 . Demographic profile of sampled households in the study area (No.).

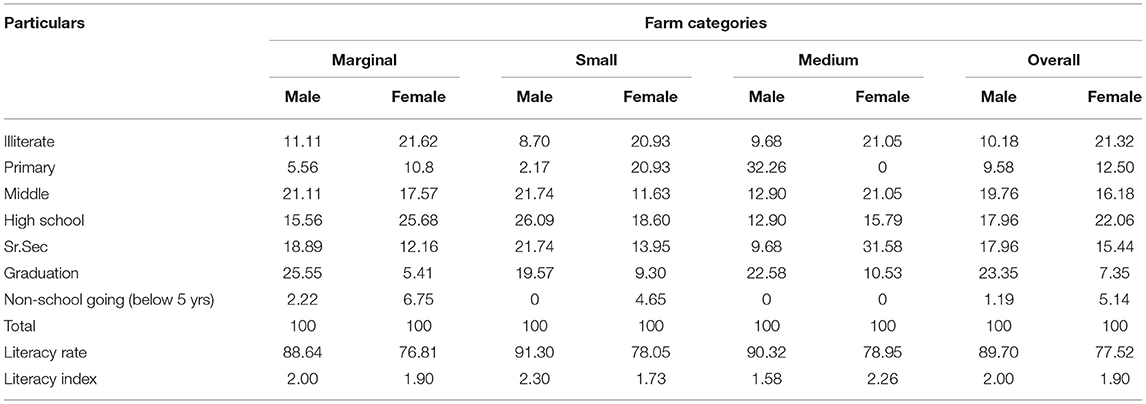

Literacy Status of the Sampled Households

Literacy is an indicator of an individual's educational status and level of education enabling him/her to engage and participate in enhancing and improving the social and economic well-being of the surroundings. Good literacy skills open up doors for education and jobs, so people can avoid poverty and underemployment. The rate of literacy is a reflection of good human capital. Higher literacy leads to a higher level of awareness, interaction with new inventions and technologies, etc. The literacy status of the sampled households is given in Table 4 . It is revealed from Table 4 that the overall literacy rate was 89.70% in males and 77.52% in females and the highest literacy rate was observed in the small farm category with 91.30% in males and 78.05% in females. Table 4 shows that 23.55% males and 7.35% females had education level upto graduation and above. The literacy index varied from 1.58 to 2.30 in males among different farm categories, while the literacy index varied from 1.73 to 2.26 in females among different farm categories, which clearly show the poor quality of education. As the level of education increases, nowadays people understand the importance of better healthcare and due to that many farmers have started to focus more on natural farming and have no adverse impact on human health.

Table 4 . Farm category-wise literacy status of sampled households (%).

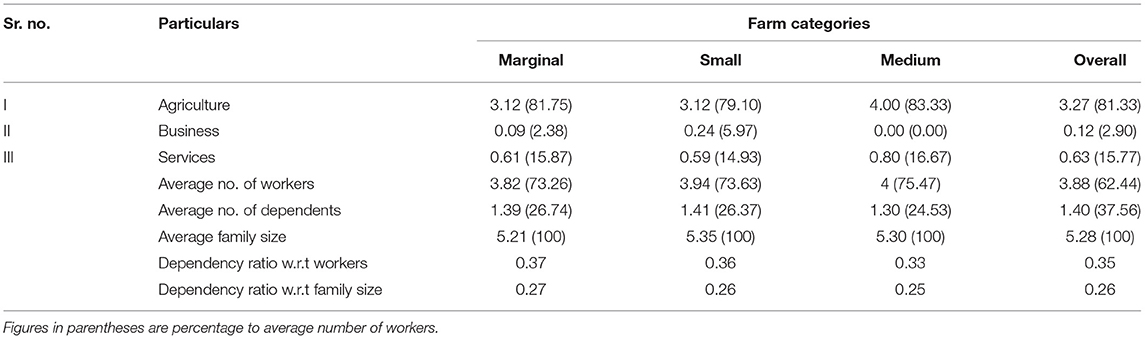

Occupational Distribution of the Sampled Households

The occupational patterns play a very significant role in ascertaining the economic status of the family. In this way, we know about the households engaged in various activities such as agriculture, business, and government or private services. In developing countries, the majority of the population are still engaged in agricultural activities and other primary activities. When the area is more developed, the employment patterns will be more diversified and household incomes will also increase. Development and progress of employment are very much linked to economic development. The occupational structure, allocation of workers, and number of dependents are shown in Table 5 .

Table 5 . Farm category-wise occupational distribution of the sampled households (No.).

The workforce reflects the distribution of members of the household making a contribution to the household economy. A family with more working people will be much more precise in terms of their livelihood strategies. Table 5 concludes that 81.33% of the households are engaged in agriculture, which means that agriculture being the main occupation in the study area. With the growing importance of natural farming, farmers have become more aware of the importance of health benefits and, hence, the percentage of farmers engaged in this sector is coming out highest as compared to business and services. On an average, 2.90 per worker were engaged in business and public/private sector (15.77%), respectively.

The largest proportion of productive agricultural workers was observed in the medium farm category with 83.33% followed by the marginal (81.75%) and small farm categories (70.10%). So, as far as the average number of dependents is concerned, the highest percentage was observed in the marginal farm (26.74%) followed by the small farm (26.37%) and lowest in the medium farm category (24.53%). At the overall level, productive workers were 3.88 and varied from 3.82 to 4.00 in the marginal to medium farm categories. The overall dependency ratio with respect to workers was (1:0.35) and among the different categories, the highest was observed in marginal category (1:0.37), followed by small (1:0.36) and medium farm categories (1:0.33). Dependency result illustrates that on average, one worker has to support less than one member of the family in the sampled household.

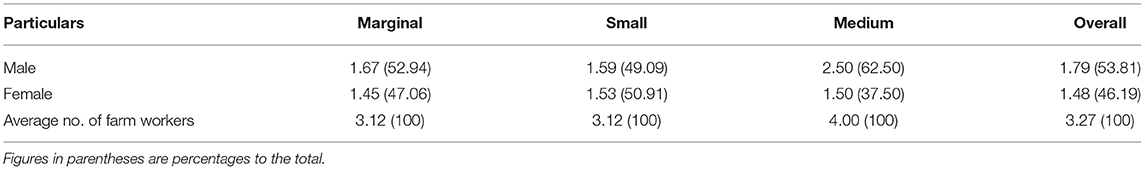

Table 6 reveals that the majority of the workforce were the males (53.81 %), while the female workers constituted 46.19%. The percentage of the male workers was the highest in medium farm category (62.50%) followed by marginal (52.94%) and small farm categories (49.09%). The proportion of female workers was considered to be the highest (50.91%) in the small farm category followed closely by the marginal (47.06%) and medium-farm categories (37.50%).

Table 6 . Gender-wise distribution of the farm workers in the sampled households (No.).

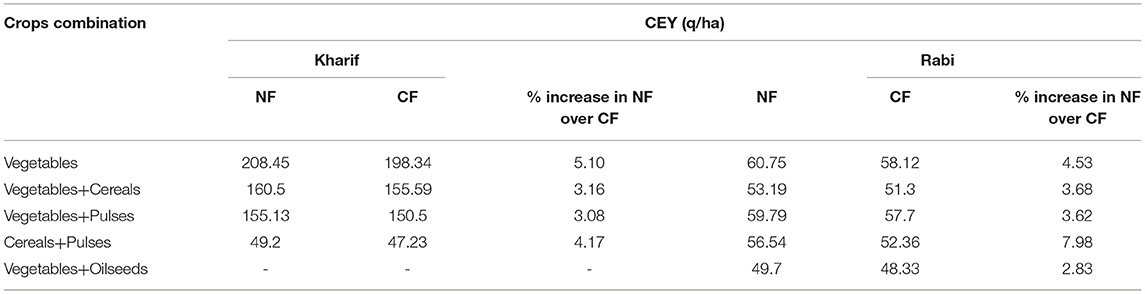

Season-Wise Major Crop Combinations Under Natural Farming System

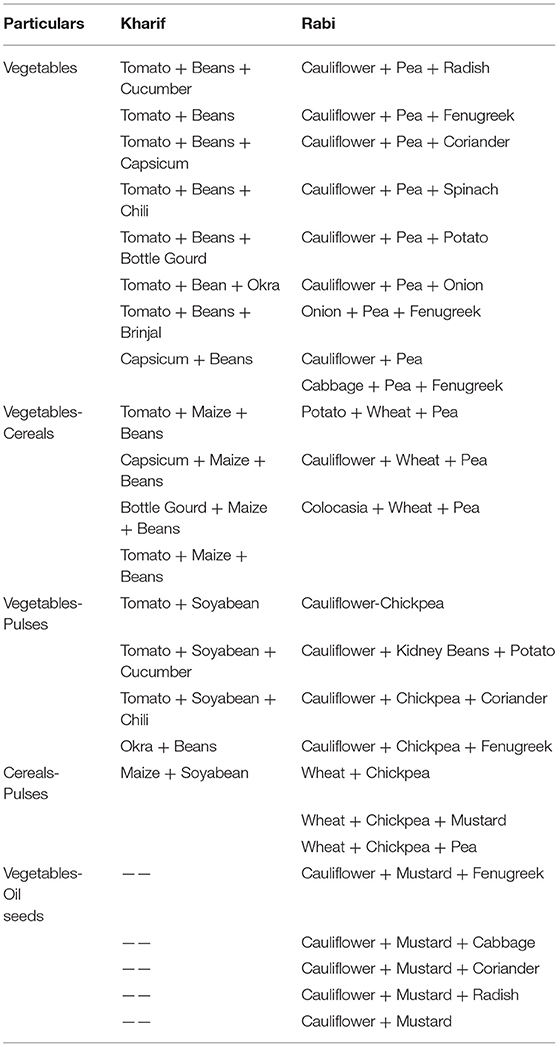

Under natural farming system, three to four crops are cultivated or grown together on the same area, along with leguminous crops as intercrop in order to ensure that no piece of land is wasted and utilized properly. These combinations during the growing season were established to encourage interaction between them and are based on the idea that complementarities exist between the plants. Intercropping with leguminous crops is considered as one of the most important components of natural farming as it increases crop productivity and soil fertility through the atmospheric nitrogen fixation. These complementarities between crops increase soil and its nutrients. It also involves diversification and improves profits by growing and selling various types of cereals, vegetables, legumes, fruit, and even medicinal plants. The multiple cropping systems substantially enhance income. This system maximizes land use and reduces the chance of crop yield loss. This study found that farmers grow different crops under different crop combinations in the study area. The major crop combinations adopted by the selected farmers were categorized as: (i) vegetables, (ii) vegetables-cereals, (iii) vegetables-pulses, (iv) cereals-pulses, and (v) vegetables-oilseeds crops. From Table 7 , it was observed that in Kharif season, the major vegetable being grown in the study area was tomato and the other crops included were capsicum, cucumber, bottle gourd, chili, okra, brinjal, etc. The main intercrops (leguminous) in the study area include French bean and soybean. The major cereals and pulses include maize, beans, soybean, etc. While in Rabi season, cauliflower is the major vegetable followed by wheat, pea, and chickpea as the major cereals and pulses grown in the study area. The other crop includes radish, fenugreek, coriander, spinach, potato, onion, garlic, etc. Mustard was being grouped under as major oilseeds crops. The main leguminous crops (intercrops) in Rabi season were pea, chickpea, and kidney beans.

Table 7 . Season-wise major crop combinations under natural farming (NF) system.

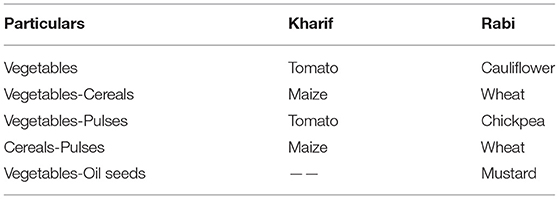

Now, in conventional farming, as opposed to natural farming, solo cropping is practiced. From Table 8 , it was observed that the main crops grown by the farmers were tomato and maize in the Kharif season and in Rabi season, the main crops grown were cauliflower, wheat, chickpea, and mustard.

Table 8 . Season-wise major crop combinations under conventional farming (CF) system.

So, in order to compare within these two systems, one main crop is kept common between the two systems. For example, from Table 1 , in the Kharif season, in natural farming, in vegetables crop combination, it was observed that tomato is the main crop and it was being planted along with several crops. Similarly, in Table 8 , under conventional farming, it was seen under the vegetables section (Kharif season) that the main crop is tomato. So, in order to compare these two systems, a comparison was made based on economic returns and, henceforth, crop equivalent yield (CEY) of multiple cropping sequences was calculated by converting the differing yields of intercrops into the equivalent yield of the main crop, i.e., tomato (in case of vegetables crop combination for both the systems) depending on price of the produce. Similarly, CEY of other crop combinations was also calculated by using this same method mentioned above.

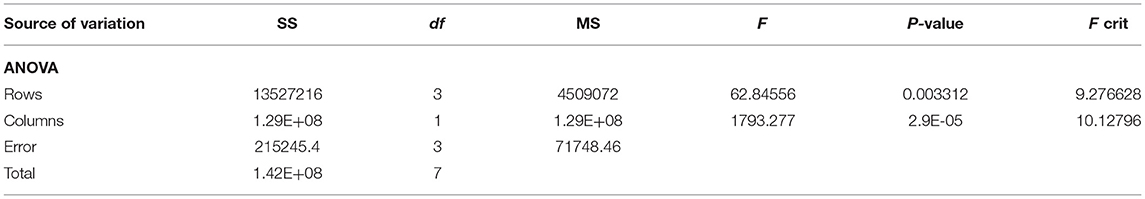

Comparative Analysis of Natural Farming System and Conventional Farming System

Under natural farming system, two or three crops are cultivated on the same farmland. Because different crop types were grown in a multiple or mixed crop system, it was hard to equate NFs economic produce with CF. So, to compare the yield, the crop equivalent yield (CEY) concept was used for a mixed cropping system. In the statistical analysis shown in Tables 9 , 10 , we can observe that, along the rows, all the crop combinations have significantly higher yields under NF as compared to CF in both the seasons. Now, from Table 11 , it was observed that, for all the crop combinations, the yield in the NF system was found to be higher than the CF system and it varied from 49.20 to 208.45 q/ha. The maximum yield was observed in vegetables 208.45 q/ha for the Kharif season. In the case of the Rabi season, it ranged from 48.33 to 58.12 q/ha. Same results were found like Kharif season, i.e., yield in all the crop combinations under NF was more than of CF. The maximum yield was observed in vegetables crop combination (58.12 q/ha). From Table 11 , it was observed that CEY of the NF system was found to be greater than that of those of the CF system. All the NF crop combinations show an average increase in yield over the CF system. In the Kharif season, the increase in the yield under NF system over CF system varied from 3.08 to 5.10%, while in Rabi season, it ranged from 2.83 to 7.98% in all the crop combinations. In Kharif season, the maximum increase in yield under NF was observed in vegetables and cereals-pulses in Rabi season. The above results were supported by Tripathi and Tauseef (2018) , which stated that the average of zero budget natural farming (ZBNF) groundnut farmers was 23% higher than their counterparts outside the ZBNF. On average ZBNF, paddy farmers had a 6% higher yield. These increments are the result of sustainable farming practices, which also improve farmers' capacity to adapt to climate change. Also, another study observed an increase in CEY under cereals-pulses combination (17.22%). This higher increase can be attributed to the comparative remunerative prices of pulses and symbiotic effect of pulses on cereal crop yield ( Chandel et al., 2021 ).

Table 9 . Statistical analysis of Kharif season from Table 11 .

Table 10 . Statistical analysis of Rabi season from Table 11 .

Table 11 . Crop equivalent yield (CEY) of various crop combinations under NF and conventional farming (CF) systems.

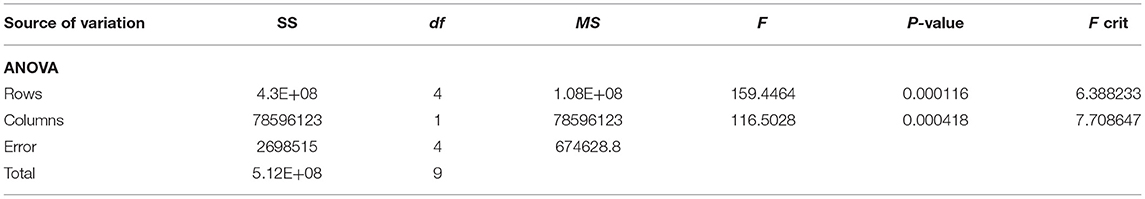

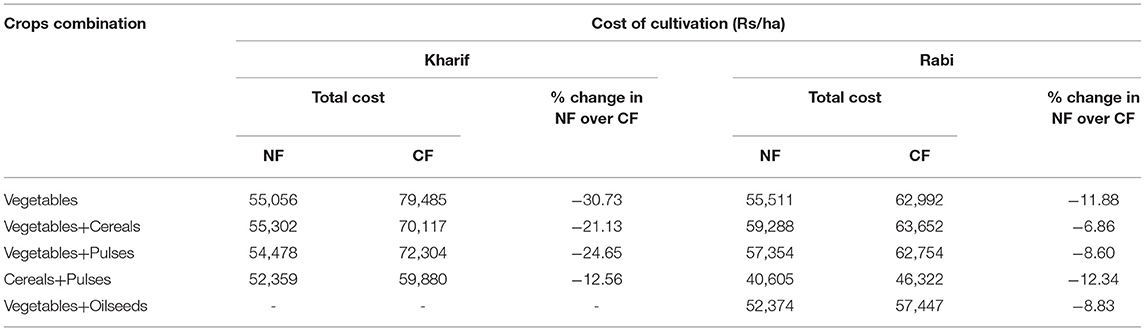

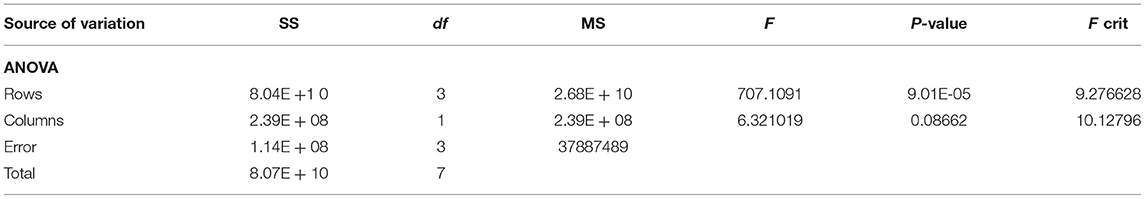

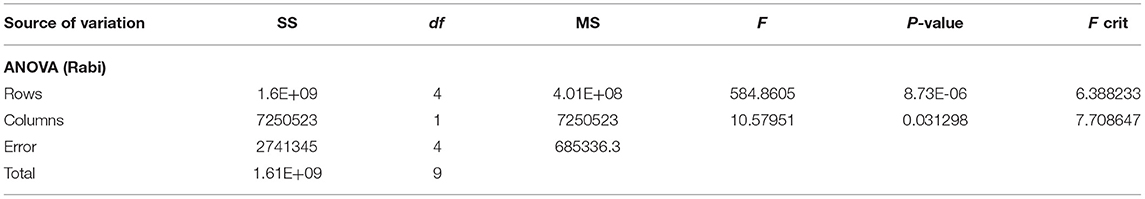

Cost of Cultivation

One of the key cost components for the production of cash crops such as fruits and vegetables under the CF system in the state is chemical inputs. This continuous farming activity has contributed to higher costs and eventually reduced incomes for farmers. A substantial decrease in the cost of growing these crops has occurred with the use of NF technology. Tables 12 , 13 indicate the statistical analysis of the cost of cultivation where we can observe that, along the rows, all the crop combinations have significantly lower costs under NF as compared to CF in both the seasons. Table 14 presents a comparison of cost of cultivation between NF and CF systems. It has been observed that the total cost of all the crop combinations in NF systems during the cultivation process was substantially reduced. In the Kharif season, the percentage reduction in NF cultivation costs over the CF system ranged from 12.56 to 30.73%, while in the Rabi season it ranged from 6.86 to 12.34%. In Kharif season, maximum reduction in cost was observed in vegetables crop combination, whereas in case of Rabi season, the maximum reduction was observed in cereal-pulses crop combination. This indicates that the NF method lowers the costs of farmers as it uses non-synthetic inputs locally in contrast to CF capital intensive inputs. Similar findings have been published, which revealed that, after converting into ZBNF, farmers had a decreased cost of cultivation for all the crops and, most significantly, farmers were able to increase their income from natural agricultural practices by increasing the number of crops ( Mishra, 2018 ). In another study, it was observed that the total cost of cultivation was reduced across all the crop combinations. The total expenditure in fruit-based cropping sequences showed a marked decline from Rs. 2,40,638 to Rs. 1,31,023 per ha., which indicate that the SPNF system reduces farmers' direct costs, boosting yields, and promotes the use of locally sourced non-synthetic inputs, compared to capital intensive CF ( Chandel et al., 2021 ).

Table 12 . Statistical analysis of Kharif season from Table 14 .

Table 13 . Statistical analysis of Rabi season from Table 14 .

Table 14 . Cost of cultivation of various crop combinations under NF and CF systems.

Conventional farming currently faces numerous challenges such as decreasing factor productivity, inappropriate and imbalanced use of nutrients, poor water and nutrient quality, depletion of natural resources, and increased input costs. Different crop combinations have clearly demonstrated that chemical-based farming technologies are highly capital intensive.

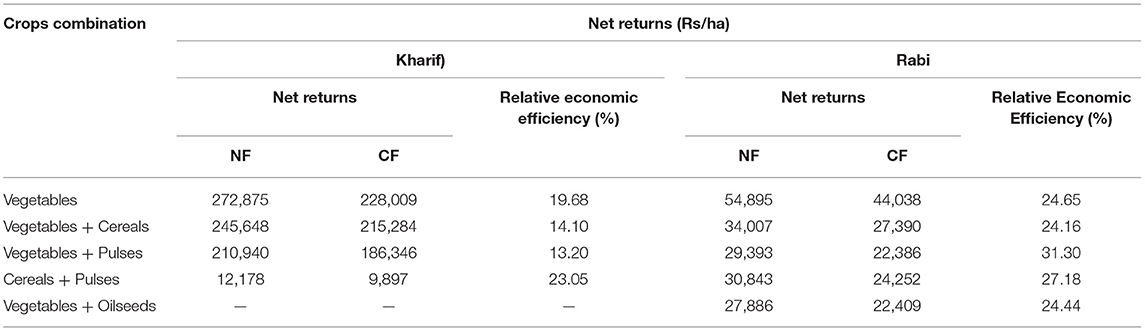

Net Returns

The profits and losses of a farm are reflected through its net income. It constitutes gross returns from the business after deduction of total cost incurred. In NF, input costs are highly diminished due to the abstinence from pesticides, insecticides, and adoption of natural inputs such as jivamrit, bijamrit, ghanjivamrit , and neemastra . NF inputs and other natural preparations have a major impact due to reduced expenditure on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The statistical analysis for net returns under NF and CF is shown in Tables 15 , 16 . Here, it is very apparent that, along the rows, all the crop combinations have significantly higher net returns under NF as compared to CF in both the seasons. Furthermore, Table 17 reveals that net returns in NF were higher than CF across all the crop combinations. The relative economic efficiency (REE), the comparative measure of economic gain in NF over the CF in all the crop combinations in the Kharif season, was 13.20 to 23.05% higher, while in the Rabi season, it was 24.16 to 31.30% higher in all the crop combinations. Maximum relative economic efficiency was observed in the cereals-pulses crop combination in the Kharif season and in Rabi season, the maximum relative economic efficiency was observed in the vegetables-pulses crop combination. Increased NF returns can be attributed to expenditure savings due to local inputs and additional revenue from intercrops. Mixed cropping helped to make more efficient use of the farm area than solo crop cultivation to further increase the net profit, in addition to increasing the variety of available crops at different times during the growing season. The results were supported by the same study undertaken by Chandel et al. (2021) which stated that the REE was 11.80 to 21.55% higher in all the crop combination under the SPNF as compared to the CF system.

Table 15 . Statistical analysis of Kharif season from Table 17 .

Table 16 . Statistical analysis of Rabi season from Table 17 .

Table 17 . Crop combination-wise net returns under NF and CF systems.

Problems Faced by the Natural Farmers

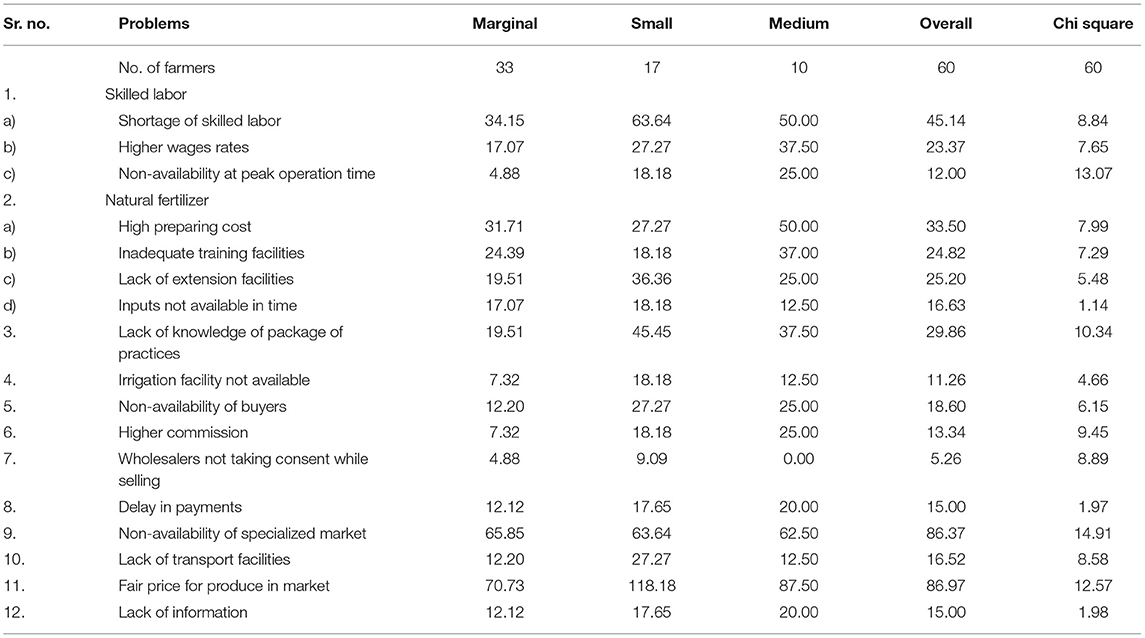

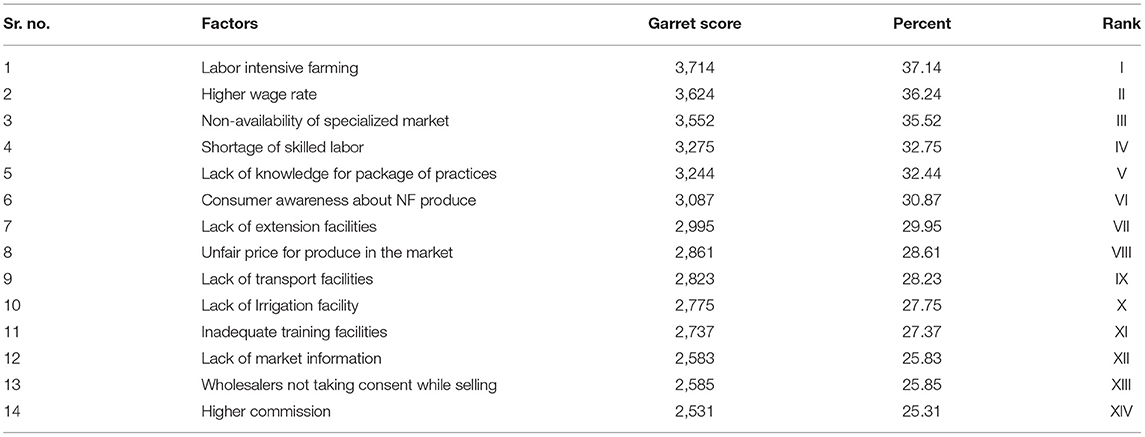

There are constraints when it comes to any development process. Likewise, there are several constraints regarding natural farming, which were faced by the concerned natural farmers of Solan district. Some of the main constraints include unfair price in the market, irrigation facilities, lack of specialized markets for the produce, high wage rates, lack of training facilities, etc. For examination of constraints, the Garrett's ranking technique was used. It must also be noted that these limitations have been aimed at the response of all the sample farmers. Table 18 shows the constraints faced by various farm categories.

Table 18 . Farm category-wise problem faced by natural farming producer in study area (Multiple response, %).

An effort was made to examine the problems between different farm categories in the field of production and marketing. The chi-squared tests have been performed to check if the problems are specified by farm category or are independent of the farm category. As prices differ greatly, producers have had problems with production and marketing due to high wage levels, lack of technical awareness, lack of safe plant material, and lack of irrigation and storage facilities. These concerns were categorized in two subgroups: production issues and marketing issues.

It was observed from Table 18 that among the production problems, shortage of skilled labor, higher wage rate, non-availability at peak operation time, and inadequate training facilities were found statistically significant. It showed significant differences between the different farm categories. In case of marketing problems, non-availability of specialized markets, lack of transport facility, and fair price in the market were found statistically significant. It showed that these problems were faced by all the farm categories.

The various problems faced by the farmers are shown in Table 19 .

Table 19 . Farmers' perceptions and problems faced by NF growers in the study area.

The Garrett's ranking system was used in this analysis, using the ranks attained by each problem to assess the most serious and the least serious problems. The major problems faced by the farmers were labor intensive (I) followed by higher wage rate (II), non-availability of specialized market (III), shortage of skilled labor (IV), knowledge of package of practices (V), consumer awareness about NF produce (VI), lack of extension facilities (VII), unfair price for produce in the market (VIII), etc. Other common problems include lack of transport facilities, lack of irrigation facilities, etc.

Intercropping with leguminous crops is considered as one of the most important components of natural farming as it increases crop productivity and soil fertility through the atmospheric nitrogen fixation. The results revealed that farmers witnessed a drop in per hectare cost of production and profitable yield for their crops as well. The farmers were pleased that natural farming is both environmentally friendly and extremely cost-effective. The crop equivalent yield (CEY) under natural farming was highest in all the crop combinations as compared to conventional farming and ranged from 3.08 to 5.10% in Kharif season and 2.83 to 7.98% in all the crop combinations in Rabi season. In Kharif season, the percentage reduction in cost of cultivation under NF over the CF system ranged from 12.56 to 30.73, while in Rabi season, it ranged from 6.86 to 12.34. The gross returns under NF systems were highest in all the crop combinations as compared to CF systems. The maximum increase in gross returns was in vegetables crop combination in both the seasons. The relative economic efficiency (REE) was highest in all the crop combinations under NF over CF system. Among the problems studied, shortage of skilled labor, higher wage rate, non-availability at peak operation time, inadequate training facilities, non-availability of specialized markets, lack of transport facility, and fair price in the market were found statistically significant. It showed significant differences between the different farm categories. The analysis showed that the natural farming system provides relatively higher returns per hectare than the conventional farming system. Also, it was observed that the major problems faced by the farmers were labor intensive (I) followed by higher wage rate (II), non-availability of specialized market (III), shortage of skilled labor (IV), knowledge of package of practices (V), consumer awareness about NF produce (VI), lack of extension facilities (VII), unfair price for produce in the market (VIII), etc. Other common problems include lack of transport facilities, lack of irrigation facilities, etc. So, there is a need for the Department of Agriculture to take up effective measures to encourage natural farming through campaigns by educating the farmers about its importance. The government should also encourage higher premium prices and channels of green marketing for the boosting of natural crops. The farmers should focus more on the full application of the NF model on their farm fields and should know the best way to use these products, i.e., proper mulching techniques (acchadan), application of jivamrit, ghanjivamrit, bijamrit, astras , etc., in order to enhance productivity.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Carrington, D.. (2019). EU Bans UK's Most-Used Pesticide Over Health and Environment Fears . London: The Guardian.

Google Scholar

Chandel, R. S., Gupta, M., Sharma, S., Sharma, P. L., Verma, S., and Chandel, A. (2021). Impact of Palekar's natural farming on farmers' economy in Himachal Pradesh. Indian J. Ecol. 48, 873–878.

Eliazer, N. A. R. L., Ravichandran, K., and Antony, U. (2019). The impact of the Green Revolution on indigenous crops of India. J. Ethn. Food 6, 1–11 doi: 10.1186/s42779-019-0011-9

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Farrell, M. J.. (1957). The measurement of productivity efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser . 120, 153–290. doi: 10.2307/2343100

Francis, C. A.. (1986). Distribution and importance of multiple cropping. Agric. Syst. 25, 238–240. doi: 10.1016/0308-521X(87)90024-2

Garrett, E. H., and Woodworth, R. S. (1969). Statistics in Psychology and Education . Vakils, Feffer and Simons Pvt. Ltd., Bombay.

Gomez, K. A., and Gomez, A. A. (1984). Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research, 2nd Edn . New York, NY: John Wlley and Sons.

Khadse, A., and Rosset, P. M. (2019a). Zero Budget Natural Farming in India-from inception to institutionalization. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 8, 21–35. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2019.1608349

Khadse, A., and Rosset, P. M. (2019b). Zero budget natural farming in India from inception to institutionalization. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 4, 5–6.

Khadse, A., Rosset, P. M., Morales, H., and Ferguson, B. G. (2017). Taking agroecology to scale: the zero budget natural farming peasant movement in Karnataka, India. J. Peasant Stud . 45, 9–12. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1276450

Menon, P., Deolalikar, A., and Bhaskar, A. (2008). Comparisons of Hunger across States: India State Hunger Index . International Food Policy Research Institute.

Ministry of Commerce (2021). Agriculture in India: Information about Indian Agriculture and Its Importance . Available online at: https://www.ibef.org/industry/agriculture-india .

Mishra, S.. (2018). Zero Budget Natural Farming: Are This and Similar Practices The Answers . Nabakrushna Choudhury Centre for Development Studies, Bhubaneswar.

Palekar (2005). The Philosophy of Spiritual Farming Amravati: Zero Budget Natural Farming Research, Development and Extension Movement . Amravati.

Pearson, K.. (1900). On the Criterion that a given system of deviation from the probable in the case of a co-related system of variables is such that it can be reasonably suppose to have arisen from random sampling. Philos. Mag. Ser. 50, 157–175. doi: 10.1080/14786440009463897

Sebby, K.. (2010). The Green Revolution of the (1960)'s and Its Impact on Small Farmers in India. Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Thesis . Available online at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses/10

Tripathi, S., and Tauseef, S. (2018). Zero Budget Natural Farming, for the Sustainable Development Goals . Andhra Pradesh.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Vashishat, R. K., Laishram, C., and Sharma, S. (2021). Problems and factors affecting adoption of natural farming in Sirmaur District of Himachal Pradesh. Indian J. Ecol. 48, 944–949.

Keywords: natural farming, sustainability, crop combinations, intercropping, Himachal Pradesh

Citation: Laishram C, Vashishat RK, Sharma S, Rajkumari B, Mishra N, Barwal P, Vaidya MK, Sharma R, Chandel RS, Chandel A, Gupta RK and Sharma N (2022) Impact of Natural Farming Cropping System on Rural Households—Evidence From Solan District of Himachal Pradesh, India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:878015. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.878015

Received: 17 February 2022; Accepted: 08 April 2022; Published: 31 May 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Laishram, Vashishat, Sharma, Rajkumari, Mishra, Barwal, Vaidya, Sharma, Chandel, Chandel, Gupta and Sharma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chinglembi Laishram, chinglaish@gmail.com

This article is part of the Research Topic

Socio-Economic Evaluation of Cropping Systems for Smallholder Farmers – Challenges and Options

Fukuoka, Natural Farming, and the Developing World

Buddhism and agriculture - part 3.

In his later life, Masanobu Fukuoka became very concerned with using natural farming to solve real-world problems. This was reflected in the progression of ideas in his writings. In his first book, The One-Straw Revolution , Fukuoka (1978/2009) outlined the philosophy and practice of natural farming. In his final book, Sowing Seeds in the Desert (Fukuoka, 1996/2012), he provided a more concrete manifesto of how natural farming can provide solutions to some of the world’s most pressing challenges. This includes a strong focus on some of the major issues affecting farming communities in developing countries.

In my first article in this series , I explored the philosophy of Masanobu Fukuoka and his system of natural farming, drawing mostly on The One-Straw Revolution . In the second article , I reported on my visit to Fukuoka-sensei’s farm in Iyo and how things have changed there since he passed away in 2008. In this post, I would like to make some general reflections on whether the philosophy and methodology of natural farming (as defined by Fukuoka-sensei) can offer benefits to poor farmers in developing countries. This post provides only some initial reflections – much more work needs to be done to document and evaluate Fukuoka’s impact in the developing world. I would, therefore, invite you to read this post and engage by leaving your thoughts in the comments section, below.

Healing the World

In Sowing Seeds in the Desert , Fukuoka (2012) treats the problems of developing societies as part of a generalised sickness afflicting all of the modern world. The symptoms of this sickness appear in the form of desertification, overpopulation, hunger and other malaises. Parts of the world – the deserts, the slums, the mountains of waste and the hollowed-out mines – are crying out for healing. According to Fukuoka, however, the road to recovery must be holistic. To illustrate this, he draws on the distinction between Western medicine – which focuses on the localised treatment of sickness – with Eastern medicine – which concerns itself with the holistic conditions of health. In so doing, he makes note that Eastern medicine’s concern with holistic health has become difficult, as we have all become so estranged from the conditions of true health (i.e., a healthy natural environment and lifestyle) that we have lost sight of what health means.

Whether the disease is in an individual body or at the level of societies or ecosystems, the path to healing lies in reconsidering the relationship between humanity and nature. As such, it is clearly not as simple as attempting to fix specific problems with a new technological intervention. The Green Revolution demonstrates clearly enough that producing more food has not had the effect of reducing hunger (see Rosset, 2000; Vanhaute, 2011). Healing occurs in relations of love, care, and joy, which bring the organism back into its condition of integration with the natural world.

When it comes to social problems like poverty and environmental destruction, the modern mentality tends to assume that the solution will lie in more ‘rational’ modern interventions: through a new efficiency measure, new technology, new development program and so on. We hope that the problem of poverty can be solved through more consumption, without recognising the extent to which consumption is part of the problem. Fukuoka steps back and observes how many of our problems relate to the simple fact that we have lent value to material possessions. If we allowed ourselves to place value on things other than ownership, many of our problems would drop away. Returning to nature by way of agriculture would allow us to live simple lives where the need for endlessly expanding consumption would be far less. Unfortunately, global agri-business has removed access to agriculture for the many of us. This begins to get closer to the root cause of the systemic illness: alienation from agriculture and, by implication, alienation from the natural world. Fukuoka points out that modern consumer societies like Japan and most Western nations have become very vulnerable, as their estrangement from agriculture means that people will lack a means of survival in the (inevitable) event of an economic collapse.

When Fukuoka looks to poorer countries, he almost seems more hopeful. He suggests that many Asian and African countries have retained a “proud agrarian ethic” and that for them, a shift towards more urbanisation in the manner of Japan and the West would be highly destructive. In saying this, he retains the somewhat romantic notion that agrarian populations would rather not be a part of modern society, citing an Ethiopian nomad who once told him that accumulating material possessions was a degrading way to live. He suggests that most of the world’s farmers see skyscrapers as ‘tombstones of the human race’ (Fukuoka, 2012: 56). 1

Fukuoka provides an insightful analysis of how post-colonial states came to lose their biodiversity and farmers’ self-sufficiency. Referring specifically to Eastern Africa, he suggests that the initial disruption to natural farming in the region came with the colonial imposition of monocultures, which killed off the forests and native varieties of cereals and vegetables. Ultimately, this left farmers in a position in which they lacked access to the seeds necessary for basic self-sufficiency. Furthermore, they drew up boundaries and imposed national parks on the people, unsettling the grazing patterns of nomads, which had occurred in a sustainable, cyclical fashion for centuries, forcing them into ever-more inconvenient arrangements and ultimately leading them to conflict amongst themselves. All of this was compounded by the fact that postcolonial states have tended to promote cash-cropping and urbanisation at the expense of rural self-sufficiency. Indeed, Fukuoka claims that on travelling to Somalia, he was requested by authorities not to promote farmer self-sufficiency too much by providing them with seeds.

In short, Fukuoka sees the colonial intervention, the imposition of modernity, and our alienation from nature as the source of the ‘disease’. The ‘cure’ can only be to rebuild the rural self-sufficiency that colonialism pulled away. This implies revegetation of lands damaged by decades and centuries of intensive cultivation, re-building agri-biodiversity and a re-establishing a healthy relationship with the earth. This is the pathway towards healing the world and healing ourselves.

Natural Farming to Revegetate the World’s Deserts

In the final quarter of his life, revegetating deserts and deforested areas in developing countries became one of Fukuoka-sensei’s chief interests. In doing this, he followed the same basic principles as he had in formulating his methods of natural farming. His guiding assumption was that the trouble of desertification was misguided human interventions into nature, and that the solution lay in removing these interventions and allowing nature to run its course.

The mainstream solution to desertification has been irrigation. The assumption is that more water will allow dried-out areas to be cropped once again. In Sowing Seeds in the Desert , Fukuoka (2012) argues against this approach, as it relies on the construction of harmful dams or the tapping of finite ground water reserves and may ultimately lead to the salinisation of soils. Instead, he promotes minimal use of water and the careful broadcasting of diverse seeds. One must sow ground-covers and grasses to cool the soil and create a mulch; trees to provide shade and bring water up from underground; poisonous plants to keep away goats; legumes to promote the proliferation of micro-organisms in the soil; and densely growing plants such as bamboo to prevent erosion along riverbanks. In this way, he deployed the methods of natural farming to address desertification and claimed some success in this endeavour in Eastern Africa and India.

Ideally, Fukuoka argued that the best approach to revegetation was to broadcast a diverse variety of seeds across the desert in clay pellets. The pellets would provide the seeds protection, moisture and sustenance and allow them to remain dormant for long periods. From there, one could leave the process up to nature. When rain finally came, suitable seeds would germinate and begin a process of rebuilding a natural ecosystem. Though most of the plants would not survive the desert conditions, even those that died might remain in the soil as mulch, nourishing other plants and cooling the soil. Trees would take root and bring up water from beneath the ground, simultaneously hydrating and cooling. Soon enough, animals would return, and a chain reaction of greening would be initiated.

In spreading these seeds, Fukuoka cared little for whether the seeds were native or not. Certainly, having some local varieties would be important, as plants from arid regions would be most suitable to the dry, hot, occasionally salty conditions of desertified lands. Nonetheless, Fukuoka insists that the movement of organisms has already become globalised and there is no point in imposing limits on which plants to sow. What’s more, the global environment has changed so much that there is no guarantee that the native varieties are, any more, the best suited to rebuild the deserts. As such, he suggested suggests:

I think we should mix all the species together and scatter them worldwide, completely doing away with their uneven distribution. This would give nature a full palette to work with as it establishes a new balance given the current conditions. I call this the Second Genesis. (Fukuoka, 2012, p. 95)

Initiating this ‘Second Genesis,’ however, proved challenging. As I described in a previous article in this series, Fukuoka was ultimately very disappointed with the limited global impact of his work. This was especially true of his efforts to combat desertification. During our visit to the farm in November, his grandson Hiroki-san informed us that Fukuoka-sensei felt disappointed that despite the tremendous potential of his plans to revegetate deserts, they were only being practiced on small tracts of land.

Fukuoka in India