- Media Center

Are We Innately Selfish? What the Science Has to Say

One of the key reasons for the unparalleled success of our species is our ability to cooperate. In the modern age, we are able to travel to any continent, feed the billions of people on our planet, and negotiate massive international trade agreements—all amazing accomplishments that would not be possible without cooperation on a massive scale.

Behavioral Science, Democratized

We make 35,000 decisions each day, often in environments that aren’t conducive to making sound choices. At TDL, we work with organizations in the public and private sectors—from new startups, to governments, to established players like the Gates Foundation—to debias decision-making and create better outcomes for everyone.

While intra-species cooperation is not a uniquely human ability, one of the reasons why our cooperative behavior is so different from that of other animals is because of our willingness to cooperate with those outside our social group. 1 In general, we readily trust strangers for advice, work together with new people, and are willing to look out for and protect people we don’t know—even though there are no incentives for us to do so.

However, while much of our success can be attributed to cooperation, the underlying motivations behind this unique ability are yet to be understood. Although it is clear that we often display cooperative and pro-social tendencies, is cooperation something that we are naturally hardwired to do? Or is it that our first instincts are inherently selfish, and it is only through the conscious repression of our selfish urges that we are able to cooperate with others?

Indeed, these questions have been debated by philosophers for millennia. For the longest time, the pervasive view was one of pessimism towards our species—that is, that we are innately selfish.

Plato compared the human soul to a chariot being pulled by two opposing horses: one horse is majestic, representing our nobility and our pure heartedness, while the other is evil, representing our passions and base desires. Human behavior can be described as an eternal tug-of-war between these two horses, where we desperately try to keep our evil horse under control. 2

The moral philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer argued for a similar perspective, writing that “Man is at bottom a dreadful wild animal. We know this wild animal only in the tamed state called civilization and we are therefore shocked by occasional outbreaks of its true nature; but if and when the bolts and bars of the legal order once fall apart and anarchy supervenes it reveals itself for what it is.” 3

Adam Smith, the father of economics, also echoed this view, famously writing in The Wealth of Nations : “It is not the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” 4

These philosophical beliefs about our selfish human nature inspired many of the teachings we encounter in everyday life. For instance, in Christianity, the Seven Deadly Sins and The Golden Rule teach us to repress our innermost selfish desires in order to think about others. Another example is in economics, where the very foundation of neoclassical economics is the idea that we are selfish, rational decision-makers.

You may be inclined to agree with these ideas. Everyone has heard of stories of cheating, lying, and stealing—all of which display the worst of our human nature, where our selfish impulses reveal themselves.

But despite the legacy of these beliefs carrying on into modern times, the idea of our innate selfishness is being increasingly challenged. Insights from the behavioral sciences are beginning to suggest that we have a cooperative instinct, and that our selfish behavior only emerges when we have the time and ability to form strategies about our decisions.

The interaction of System 1 and System 2

Anyone remotely interested in psychology or economics has probably heard of the dual-systems theory of decision-making: the idea that our decisions are governed by two opposing cognitive “systems.” System 1 is the automatic and emotional part of our brain, and System 2, the slow and deliberative part. 5

These two systems are very much related, and their interaction and relative levels of activation can determine our behavior. This means that certain stimuli can enhance or inhibit the influence of one system’s functioning in the decision-making process. For instance, making a decision when feeling overwhelmed with multiple tasks, time pressure, or mental and physical exhaustion can weaken an individual’s System 2 thinking and make them more reliant on their System 1 judgments. 6

This should be unsurprising: when you’re mentally overwhelmed, you probably aren’t thinking things through, and you’re going to make decisions by impulse! In a similar fashion, facilitating System 2 thinking by giving people time to make decisions, or incentivizing people to think about things deeply, can suppress System 1 and enhance System 2 thinking.

Through this lens of the interaction between System 1 and System 2, researchers in psychology and economics have found a new way to answer this age-old question. By manipulating elements such as time pressure to enhance impulsivity in some subjects and promote deliberation in others, researchers have been able to differentiate the effects of System 1 and System 2 on our behavior to see whether we truly are instinctively selfish or cooperative.

The cooperative instinct

Experiments that require cooperation between participants are used to investigate instinctive versus calculated greed. Take the public goods game, for instance. In this game, players are placed in groups and given an endowment (typically around $10). They are asked to donate a certain amount of their endowment for a “public good,” where their donations will be doubled and subsequently split between the players. You should be able to spot an interesting dynamic in this game: by cooperating and contributing more to the public good, everyone will benefit. But by acting selfishly, you alone will benefit at the expense of the group.

What happens when you are asked to make this contribution to the public good when you are solely under the influence of System 1 (i.e. when System 2 is under stress from some form of cognitive strain)? It turns out, when required to make a decision within 10 seconds, participants in experimental groups acted more cooperatively. Participants who acted on impulse contributed more to the public good than those who had time to think about their contributions. 7

What was also fascinating from this study was that, when participants were given time and encouraged to think about their decisions, participants opted to be greedier. Apparently, when relying on instinct, we are willing to cooperate, but when we are given a chance to think about the costs and benefits of our decisions, we think more about our own outcomes than those of others.

These findings also held true for the prisoner’s dilemma game, another activity that involves a cooperative dynamic (if you’re from the UK, this game is analogous to the “split-or-steal” situation in the game show “Golden Balls”). Similar results were also found when conducting these experiments in person rather than through a computer program.

These findings are certainly fascinating, but you might be thinking that behavior in a lab experiment may not be replicable in real life. Let’s say, for example, someone approached you on the street and asked you to contribute to a charity, and you had no time to make a decision (perhaps you’re late for work). Do you think you would donate? Perhaps more field research is necessary to confirm these findings in real-world scenarios.

Another approach to studying our cooperative instincts is to examine the behavior of babies. Intuitively speaking, babies should represent humankind in our most primal state, where we are most reliant on instincts to make our decisions. From a biological perspective, babies have underdeveloped brains and are extremely helpless at birth, which explains why we take a much longer time to mature in comparison to other animals. (We evolved this way because if our heads got any bigger, we would struggle to get out of our mother’s womb.) 8 So, investigating the cooperative/selfish tendencies of babies should theoretically reflect our true human nature.

And indeed, researchers have found that babies display a strong tendency to cooperate. Toddlers as young as 14-18 months are willing to pick up and hand you an object you accidentally dropped without any praise or recognition; they are willing to share with others; and they are also willing to inform others of things that will benefit them, even if it brings no benefit to the toddler themselves. 9 This is in contrast to chimpanzee babies, who do not display the same amount of cooperative tendencies at a young age. This showcases that perhaps it is a uniquely human ability to be instinctively cooperative.

Why are we instinctively cooperative?

So it seems that it’s possible the great thinkers of our history may have been wrong—perhaps we are not as selfishly wired as we think. The findings from the public goods game study and infant studies suggest that we may be actually instinctively cooperative rather than selfish. But what are the possible explanations for this?

From an evolutionary biology perspective, it could be that cooperative genes were selected for, because it was the best survival strategy. Those who were more innately cooperative were able to experience more advantageous outcomes and survive long enough to pass on their genes to their offspring. 10

But there are also many instances where our first impulse is to not cooperate, and many instances where, after much deliberation, we still decide to cooperate. We’ve all met people who simply seem less trustworthy, and we can all think of times where we ended up trusting somebody after having a long time to think about our decision—for example, after contemplating a business deal, or purchasing something expensive from someone else.

The social-heuristics hypothesis (SHH) aims to tie these ideas together. This theory predicts that variation in our intuitive and cooperative responses largely depends on our individual differences as well as the context we are in. 11

Our intuitive responses are largely shaped by behaviors that proved advantageous in the past. For instance, imagine you’re playing for a basketball team. If you realize that working together with your teammates is advantageous for winning matches, you will gradually start to develop instinctive responses to cooperate with your teammates in order to continue winning games. But if you start to recognize that you are carrying the team and that trusting your teammates is actually hindering the team’s results, you will start to develop more instinctively selfish behaviors and not pass to them as frequently.

With this perspective, our instinctive responses all depend on which strategy—cooperation or selfishness—worked for us in the past. This can explain why most participants in the public goods game chose to cooperate: cooperative behaviors are typically advantageous in our daily lives. 12

In our modern age, our lives are more interconnected than ever. There are over 7 billion of us now, where our experiences are easily shareable on social media and our businesses require close collaboration with partners in order to mutually benefit. Behaving in accordance with social norms 13 is more important than ever, where we frequently require cooperation with others in our daily life and any self-serving behavior often leads to social criticism and damage to one’s reputation. We quickly learn to cooperate and adapt to these social norms, and this, in turn, hardwires our instincts towards more cooperative behaviors.

On the other hand, deliberation allows us to adjust to specific situations and override our intuitive responses if that intuitive response is not actually beneficial in the present context. In other words, deliberation allows us to strategize and suppress our individual instinctive desires in order to choose the most optimal choice, whether this be cooperation or noncooperation. When there are no future consequences, such as in the public goods game experiment, even though our instincts may be cooperative, deliberation will likely skew towards selfish behavior as we realize that strategic selfishness will make us better off and that we won’t be punished for free-riding.

However, when there are future consequences, deliberation will favor cooperation or noncooperation depending on the individual’s beliefs about which behavior will be more strategically advantageous. Take the star basketball player example again: although his instinctive response is to go at it alone, given that his selfish behavior could lead to potential future consequences (e.g. unhappiness from his teammates, criticism from observers, being dropped by the coach), he may override his initial impulses and work with his team, since it would be strategically advantageous to do so. Our System 2 processes allow us to stop and think about our intuitions, and strategize accordingly.

Concluding remarks

So, there is compelling evidence against an idea that has shaped our teachings for millennia. The evidence seems to point to the conclusion that, in general, we have an innate desire to cooperate, and in fact, it is only when there are opportunities to be strategically selfish that we reveal our more undesirable tendencies.

Understanding our instinctive human tendencies will be essential as our species encounters some of the biggest challenges that we will have ever encountered. Climate change, political tensions, and inequality are issues that threaten the very existence of our species, and can only be resolved through cooperation on a global scale. Within us, there lies an instinctive desire to cooperate. Knowledge of this fact could inspire new and creative solutions, in order to rally people into tackling these challenges together.

- Melis, A. P., & Semmann, D. (2010). How is human cooperation different?. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences , 365 (1553), 2663–2674. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0157

- Plato. (1972). Plato: Phaedrus (R. Hackforth, Ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316036396

- Schopenhauer, A. (1851). On reading and books. Parerga and Paralipomena .

- Smith, A. (1937). The wealth of nations [1776].

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Loewenstein, G. (1996). Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes , 65 (3), 272-292.

- Rand, D. G., Greene, J. D., & Nowak, M. A. (2012). Spontaneous giving and calculated greed. Nature , 489 (7416), 427-430.

- Knight, M. (2018, June 22). Helpless at birth: Why human babies are different than other animals. Retrieved from: https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2018/06/22/helpless-at-birth-why-human-babies-are-different-than-other-animals/

- Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2006). Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science , 311 (5765), 1301-1303.

- Robison, M. (2014, September 1). Are People Naturally Inclined to Cooperate or Be Selfish? Retrieved from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/are-people-naturally-inclined-to-cooperate-or-be-selfish/

- Rand, D. G. (2016). Cooperation, fast and slow: Meta-analytic evidence for a theory of social heuristics and self-interested deliberation. Psychological science , 27 (9), 1192-1206.

- Rand, D. G., & Nowak, M. A. (2013). Human cooperation. Trends in cognitive sciences , 17 (8), 413-425.

- https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/anthropology/social-norm/

About the Author

Tony Jiang is a Staff Writer at the Decision Lab. He is highly curious about understanding human behavior through the perspectives of economics, psychology, and biology. Through his writing, he aspires to help individuals and organizations better understand the potential that behavioral insights can have. Tony holds an MSc (Distinction) in Behavioral Economics from the University of Nottingham and a BA in Economics from Skidmore College, New York.

Selfish Altruism: A Win-Win?

Many of those who go out of their way to assist others are motivated by something more than just providing social support.

How To Motivate Volunteers With Behavioral Science

Volunteering is often thought as the ultimate act of altruism. Yet there is some evidence that volunteering has many benefits for the mental and physical health of the person who is volunteering their time and energy.

Can Borrowing Bring Us Together?

Dr. Straeter and Jessica Exton sit down with The Decision Lab to discuss the perks and pitfalls of lending for friendships.

Eager to learn about how behavioral science can help your organization?

Get new behavioral science insights in your inbox every month..

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Altruism Articles & More

Debunking the myth of human selfishness, two new books explore the far-reaching science of cooperation..

Are humans inherently and universally selfish? When and why do we cooperate?

Two recent books, both by Harvard professors, seek answers to these timeless and essential questions, though they approach them from different perspectives. In SuperCooperators , Martin Nowak, a professor of biology and mathematics, and acclaimed science writer Roger Highfield argue that cooperation is an indispensable part of our evolutionary legacy, drawing on mathematical models to make their case.

In The Penguin and the Leviathan , on the other hand, law professor Yochai Benkler uses examples from the business world and the social sciences to argue that we ultimately profit more through cooperation than we do by pursuing our own self-interest.

Taken together, the books provide strong and complementary accounts of the far-reaching science of cooperation.

SuperCooperators is an overview of Nowak’s ambitious, groundbreaking research challenging a traditional take on the story of evolution—namely, that it’s one of relentless competition in a dog-eat-dog world. Rather, he proposes that cooperation is the third principle of evolution, after mutation and selection. Sure, mutations generate genetic diversity and selection picks the individuals best adapted to their environment. Yet it is only cooperation, according to Nowak, that can explain the creative, constructive side of evolution—the one that led from cells to multicellular creatures to humans to villages to cities.

Life, his research suggests, is characterized by an extraordinary level of cooperation between molecules. Indeed, Nowak devotes one chapter to cancer, which is nothing less than a deadly breakdown of cooperation on the cellular level.

So how has cooperation been so important to our survival? The first half of SuperCooperators answers this question as Nowak and Highfield outline five ways that cooperators maintain an evolutionary edge: through direct reciprocity (“I scratch your back, you scratch mine”), indirect reciprocity/reputation (“I scratch your back, somebody else will scratch mine”), spatial selection (clusters of cooperators can prevail!), group selection (groups comprised of cooperators can prevail!), and “kin selection” (close genetic relatives help each other).

SuperCooperators not only chronicles what Nowak has discovered during his exciting academic journey but the journey itself—it is his scientific autobiography, as well as a biography of the field and its most pre-eminent characters. For the uninitiated in math and the natural sciences, the book might feel a bit technical in a few places. Yet it is a readable and stimulating book overall, particularly rewarding for readers interested in the evolutionary roots of cooperation or an insider’s view of the world of science.

In The Penguin and the Leviathan , Benkler also reviews research at the intersection of evolution and cooperation, citing Nowak’s work at times. Yet Benkler draws more heavily on research from the social and behavioral sciences—namely history, technology, law, and business.

The title of the book comes from Tux the Penguin, the logo of the free, open-source operating system software Linux. Tux symbolizes the inherently cooperative, collaborative, and generous aspects of the human spirit, and according to Benkler “is beginning to nibble away at the grim view of humanity that breathed life into Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan.” The book aims to debunk “the myth of universal selfishness” and drive home the point that cooperation trumps self-interest—maybe not all the time and not for everyone, but far more consistently than we have long thought.

Benkler recounts that in any given experiment where participants have to make a choice between behaving selfishly and behaving altruistically, only about 30 percent of people behave selfishly, and in virtually no human society studied to date have the majority of people consistently behaved selfishly. Furthermore, as he points out, the cues in a situation can be more powerful than personality traits in predicting cooperation: In one study where participants played a game in which they could cooperate or compete, only 33 percent of them cooperated when the game was called the “Wall Street Game,” whereas 70 percent did so when it was called the “Community Game.”

In an easy-flowing, conversational style, Benkler elaborates on the key ingredients that make successful cooperation possible, such as communication, empathy, social norms, fairness, and trust. We learn, for example, that when study participants play a game in which they can cooperate or compete, levels of cooperation rise by a dramatic 45 percent when they are allowed to communicate face-to-face. The research on social norms is especially compelling: When taxpayers are told that their fellow citizens pay their fair share of taxes, or that the majority of taxpayers regard overclaiming tax deductions as wrong, they declare higher income on their taxes.

But Benkler doesn’t just limit the book to reviewing scientific studies. He also provides plenty of real-world examples that bring the science to life, making the book read like a handy guide to designing cooperative human systems. From kiva.org to Toyota to Wikipedia to CouchSurfing.org and Zipcar, he shows how organizations relying on cooperation—instead of incentives or hierarchical control—can be extraordinarily effective.

Neither Nowak nor Benkler are naïve about the prospects for cooperation. They remind us that there will always be selfish people, and that the cycles of cooperation will perpetually wax and wane. Besides, being “good” and “cooperative” are not necessarily synonymous—unspeakably cruel, inhumane acts have been committed by people who were deeply “cooperative” (think of Nazi Germany, the USSR, the Rwandan genocide).

Yet both authors are optimistic about the power and promise of cooperation, and agree that the world needs cooperation now more than ever: The gravest problems of our era—such as climate change, natural resource depletion, and hunger—can only be solved when people set self-interest aside and work together. Both SuperCooperators and The Penguin and the Leviathan leave us with an appreciation for the centrality of cooperation to life—and should inspire us to try to harness the science of cooperation for the greater good.

About the Author

Pelin Kesebir

Pelin Kesebir, Ph.D. , has a degree in Social Psychology and Personality and works as an assistant scientist at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. She studies happiness and virtues, and the different ways in which well-being can be improved.

You May Also Enjoy

Very timely releases, but I won’t be holding my breath waiting for the world to change. The global oligarchy that has the rest of humanity and the ecosystem by the throat is not going to let go voluntarily. We live in an age of cooperation, alright: cooperation among apex predators extracting as much wealth as possible from the global economy, irrespective of long-term social and environmental costs.

Don’t believe me? The governance and economics of the United States provide a perfect illustration. Wall Street bankers walked away from the wreckage of the global economy, their personal portfolios fattened by fabulous bonuses for a job well done, and need have no fear of ever being prosecuted for the most severe and systematic financial fraud ever perpetrated. The government that they captured set in place a legislative framework and lax regulatory environment that allowed them to turn the world into a private casino. And that government continues to give them special tax breaks, makes sure that even the states can’t prosecute them for mortgage fraud, and continues to prop up an ever-more concentrated financial sector with supportive monetary policies.

Sorry about the rant, but this is the reality of human cooperation in our time. The people who need to read these books - to have the message seared into their prefrontal cortex - are spitting out their champagne in laughter.

Higher Plane | 8:33 am, September 14, 2011 | Link

Higher Plane is critical of contemporary American society, but his critique is not directly relevant to the issue. The underlying issue is whether life on our planet is the human species’ DESTINY, or merely our species’ TESTING-GROUND preparatory to the Afterlife. The latter view may strike some readers as absurd, but those who think it is absurd have not read the traditional religious literature on the topic; and do not realize the extent to which this literature dominates the thinking of a large segment of the morally-concerned population. The first item of awareness, for those concerned about the condition of our planet as a human habitat, is to discover the continuing predominance of regarding the Afterlife central, and life on Earth peripheral, in global religious doctrine.

Observe/Reflect | 4:05 pm, September 27, 2011 | Link

Observe/Reflect - If your point is that religious fundamentalists are ignoring environmental degradation here on earth because they are far more interested in passing through the pearly gates, then your critique and mine are more closely related than you might think. (I say “if” because it is not entirely clear whether you approve or disapprove of this tendency, and I hasten to add that one does not have to be religious to be moral.)

As Kevin Phillips explained at great length in “American Theocracy,” the child-like belief of evangelical Christians that God will make everything alright in some final reckoning leads them to look askance at the environmental movement. This plays right into the hands of the greedy corporations for whom heaven is a bulging bottom line. The presidential candidacy of Michele Bachmann embodies this alliance with breathtaking clarity and ugliness.

Does this unholy alliance of interests represent cooperation? Absolutely, unless we want to split hairs about the extent to which all parties are consciously aware of their choices. The religious fundamentalists may not be thinking about the political or economic consequences of their beliefs (though Republican primary voters might well be). When politics is the primary avenue through which human beings cooperate in the attainment of social goals, and when so much is at stake, the political arena is a superb testing ground for any hypothesis about human selfishness or altruism.

Higher Plane | 5:50 pm, September 27, 2011 | Link

Higher Plane, There is indeed a synergy between the forces of the profit-focused corporate executives and of the Afterlife-focused religious traditionalists. One helps the other achieve their short-term goals, at the expense of the global viability of our species. Between the lines of both our messages is the need for an action program beyond feeling good about human cooperativeness, an action program to break up the synergy described above. Perhaps other readers here can reflect on the steps involved in such an action program—a program that should be the focus of a constructive response to the problem.

Observe/Reflect | 9:47 pm, September 27, 2011 | Link

This was a very timely topic. This week I unwittingly turned to a conservative talk radio station, they were asking people to say how they used denial to deal with unpaid bills. The bit was hillarious! Of course I was disgusted when I realized they were a right-wing station, but I then thought what a shame they are normally hostile. They could use their obvious humor to get both “sides” talking. This is indeed a complex topic.

I think it’s a mistake to start out with a comparison to the natural world. For one, “survival of the fittest” is being seriously modified, and even if it’s valid, the comparison to humans is a bit of useless anthropomorphizing.

Here’s why - wildlife are not just cute things running around. They are part of the biosphere - a layer of Earth just like the atmosphere or lithosphere.

“Cooperation” of molecules is more like chemical reaction. It’s also about ecological niche - what fits.

Human pack mentality (the fact that we naturally want to belong to a group and are social animals) could be compared to wolves or dogs, but not really to molecules or the biosphere. Those things work together mostly because of chance and chemical reactions.

Emmy | 6:58 pm, September 29, 2011 | Link

interesting review it worth reading

Asala mp3 | 11:11 am, November 11, 2011 | Link

quite an interesting review, well worth the read.

Easytether | 12:32 pm, December 5, 2011 | Link

Good stuff. I love it! Thanks for the information.

Jesus Pictures | 4:11 pm, January 4, 2012 | Link

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

When It's OK to Be Selfish

A new scale for measuring healthy selfishness..

Posted November 7, 2022 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

- Society has a taboo of selfishness.

- It's important to distinguish between healthy selfishness and unhealthy selfishness.

- We created the Healthy Selfishness Scale (HSS) to investigate the correlates of healthy selfishness in the real world.

- Healthy selfishness is correlated with higher levels of well-being, life satisfaction, and genuine motives for helping others.

“Modern culture is pervaded by a taboo on selfishness,” wrote Erich Fromm in his 1939 essay " Selfishness and Self-Love ." "It teaches that to be selfish is sinful and that to love others is virtuous." Fromm notes that this cultural taboo has had the unfortunate consequence of making people feel guilty for showing themselves healthy self-love and has even caused people to become ashamed of experiencing pleasure, health, and personal growth.

What if the way we are socially conditioned to think about selfishness is misguided? What if there is great value in cultivating healthy selfishness? Inspired by Fromm's essay, the humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow argued for the need to distinguish between healthy selfishness , which is rooted in psychological abundance, and unhealthy selfishness , which is rooted in psychological poverty, neuroticism , and greed.

“For our part, we must not prejudge the case," notes Maslow. "We must not assume that selfish or unselfish behavior is either good or bad until we actually determine where the truth exists. It may be that at certain times, selfish behavior is good, and at other times, it is bad. It also may be that unselfish behavior is sometimes good and at other times bad.”

Both Maslow and Fromm held that healthy self-love requires a healthy respect for oneself and one’s boundaries , and affirmation of the importance of one’s own health, growth, happiness , joy, and freedom. Self-actualizing people have healthy boundaries, self-care, and the capacity to enjoy themselves.

Drawing on both Fromm and Maslow's writings, I was inspired to create a " Healthy Selfishness Scale " (HSS) and investigate its correlates in the real world. I defined healthy selfishness as having a healthy respect for your own health, growth, happiness, joy, and freedom. Here are the items on the Healthy Selfishness Scale

- I have healthy boundaries.

- I have a lot of self-care.

- I have a healthy dose of self-respect and don’t let people take advantage of me.

- I balance my own needs with the needs of others.

- I advocate for my own needs.

- I have a healthy form of selfishness (e.g., meditation , eating healthy, exercising, etc.) that does not hurt others.

- Even though I give a lot to others, I know when to recharge.

- I give myself permission to enjoy myself, even if it doesn’t necessarily help others.

- I take good care of myself.

- I prioritize my own personal projects over the demands of others.

Our findings may surprise you. They definitely go against the grain of the cultural narrative that all forms of selfishness are necessarily bad. In terms of benefits to self, we found that healthy selfishness was a strong positive predictor of high self-worth , well-being, and life satisfaction, and was a strong negative predictor of depression . We found that the Healthy Selfishness Scale predicted adaptive psychological functioning above and beyond other personality traits that have traditionally been studied in psychology (e.g., the Big Five personality traits ).

Healthy selfishness was positively related to a sense of self-competence (the perception that one is reaching one's goals in life) and authentic pride for one's accomplishments. Healthy selfishness was not correlated with hubristic pride , or a motivation to aggressively dominate others on the way to the top.

Along similar lines, healthy selfishness was negatively correlated with unhealthy selfishness , which we defined as a strong motivation to exploit others for your own personal gain, and healthy selfishness was negatively correlated with vulnerable narcissism and toxic altruism (the tendency to help others for one's own selfish gain). It’s clear that healthy selfishness can be distinguished from pathological self-love and even pathological self-sacrifice.

Interestingly, we found that healthy selfishness was negatively related to intrusive and overbearing child-rearing practices. Perhaps healthy selfishness develops as the result of being able to express one's needs as a child in a healthy manner.

Individuals with high levels of healthy selfishness also tended to show themselves greater self-compassion . We are often so cold to ourselves, and self-compassion offers a valuable tool to help free ourselves from ourselves. As Fromm put it , “People are their own slave drivers; instead of being the slaves of a master outside of themselves, they have put the master within.”

Finally, it may seem paradoxical, but we also found that people who scored higher in healthy selfishness were more likely to care about others and report genuine motives for helping others ("I like helping others because it genuinely makes me feel good to help others grow"). Healthy selfishness was negatively related to more neurotic motives for helping others ("A major reason why I help people is to gain approval from them"; "I often give to others to avoid rejection").

Erich Fromm conceptualized love as an attitude , a way of being in the world where you have a healthy respect for the health, growth, happiness, joy, and freedom of others. Our research suggests that the light of love can shine in any direction— outside to others but also inside to help develop one's own self.

Love is love. Full stop.

Facebook image: Hitdelight/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: JLco Julia Amaral/Shutterstock

Kaufman, S.B., & Jauk, E. (2020). Healthy Selfishness and Pathological Altruism: Measuring Two Paradoxical Forms of Selfishness . Frontiers in Psychology .

You can take the test here and see how your results compare to others who have taken the test.

Scott Barry Kaufman is a humanistic psychologist exploring the depths of human potential.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Healthy selfishness and pathological altruism: measuring two paradoxical forms of selfishness.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

- 2 Clinical Psychology and Behavioral Neuroscience, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany

- 3 Department of Psychology, University of Graz, Graz, Austria

Selfishness is often regarded as an undesirable or even immoral characteristic, whereas altruism is typically considered universally desirable and virtuous. However, human history as well as the works of humanistic and psychodynamic psychologists point to a more complex picture: not all selfishness is necessarily bad, and not all altruism is necessarily good. Based on these writings, we introduce new scales for the assessment of individual differences in two paradoxical forms of selfishness that have lacked measurement in the field – healthy selfishness (HS) and pathological altruism (PA). In two studies ( N 1 = 370, N 2 = 891), we constructed and validated the HS and PA scales. The scales showed good internal consistency and a clear two-dimensional structure across both studies. HS was related to higher levels of psychological well-being and adaptive psychological functioning as well as a genuine prosocial orientation. PA was associated with maladaptive psychological outcomes, vulnerable narcissism, and selfish motivations for helping others. These results underpin the paradoxical nature of both constructs. We discuss the implications for future research, including clinical implications.

“ Any pleasure that does no harm to other people is to be valued. ”– Russell (1930)

“ What we value so much, the altruistic ‘good’ side of human nature, can also have a dark side. Altruism can be the back door to hell. ” – Oakley et al. (2012)

Introduction

We tend to think of altruism as unselfish and beneficial, with minimal tradeoffs, and selfishness as generally bad and glutinous, negatively impacting on others. Reality points to a much more complex story. There are many examples across human history of the unintended negative consequences of altruism on the self and others, despite the best intentions. Oakley et al. (2012) refer to this as “pathological altruism” and note that “some of human history’s most horrific episodes have risen from people’s well-meaning altruistic tendencies” (p. 3). They use the example of Oliver Wendell Holmes, a well-respected American Supreme Court justice, whose well-intentioned rhetoric supported eugenic forced sterilization. On the flip side, Maslow (1943/1996) noted that “healthy selfishness”— a healthy respect for one’s own health, growth, happiness, joy, and freedom— can have a positive impact both on the self and on others.

While there has been some theory and indirect evidence (e.g., vignettes and historical examples) of these paradoxical forms of selfishness, there is a dearth of empirical evidence systematically investigating individual differences in healthy selfishness and pathological altruism. We believe this is due, in large part, to the lack of reliable and valid scales to capture these constructs. In the current study, we present new scales of both healthy selfishness and pathological altruism and distinguish them from related constructs in the field. By doing so, we hope to add more nuance to both the concepts of “selfishness” and “altruism” and offer new research tools for researchers to further investigate individual differences in these understudied topics, which have important societal and clinical implications.

Healthy Selfishness

In his 1939 essay “Selfishness and Self-Love,” Erich Fromm opened by declaring that “Modern culture is pervaded by a taboo on selfishness. It teaches that to be selfish is sinful and that to love others is virtuous.” In his essay, Fromm argues that this cultural taboo has had the unfortunate consequence of making people feel guilty to show themselves healthy self-love, which he defines as the passionate affirmation and respect for one’s own happiness, growth, and freedom.

Fromm argues that the form of selfishness that society decries— an interest only in oneself and the inability to give with pleasure and respect the dignity and integrity of others— is actually the opposite of self-love. To Fromm, love is an attitude that is indiscriminate of whether it is directed outward or inward. In contrast, Fromm argued that selfishness is a kind of greediness: “Like all greediness, it contains an instability, as a consequence of which there is never any real satisfaction. Greed is a bottomless pit which exhausts the person in an endless effort to satisfy the need without ever reaching satisfaction” ( Fromm, 1939 ).

Inspired by Fromm’s essay, Maslow (1943/1996) wrote an essay in which he argued for the need to clearly distinguish “healthy selfishness” from unhealthy selfishness, as well as the importance of distinguishing healthy and unhealthy motivations for one’s seemingly selfish behavior.

Defining selfishness as any behavior that brings any pleasure or benefit to the individual, Maslow argued that: “For our part, we must not prejudge the case. We must not assume that selfish or unselfish behavior is either good or bad until we actually determine where the truth exists. It may be that at certain times, selfish behavior is good, and at other times, it is bad. It also may be that unselfish behavior is sometimes good and at other times bad.” Maslow goes on to note that “a good deal of what appears to be unselfish behavior may come out of forces that are psychopathological and that originates in selfish motivation” (p. 110).

Calling for the need for a new vocabulary that incorporates the notion of healthy selfishness, Maslow noted that in the process of psychotherapy it is sometimes necessary to teach people at certain times to engage in a “healthfully selfish manner”— to have a healthy respect for one’s self that stems from abundance and need gratification— that “comes out of inner riches rather than inner poverty” (p. 110).

A recent meta-analysis of the literature on communion supports these early ideas. Le et al. (2018) found that communally motivated people who care for the welfare of others and their close relationship partners experience greater relationship well-being. However, personal well-being was maximized only to the extent that people were not self-neglecting in their communal care . Therefore, while the health and relationship benefits of promoting the well-being of others has been well-documented ( Crocker and Canevello, 2008 , 2018 ), the role of healthy selfishness in contributing to well-being and relationships may have been neglected in the literature.

Pathological Altruism

According to Crocker and Canevello (2008 , 2018) , humans evolved two systems: an “egosystem” that is motivated by a desire for positive impressions from others, and an “ecosystem,” which is motivated by the promotion of the well-being of others by fostering their thriving and avoiding harm to them. Critically, Crocker and Canevello (2018) argue that sometimes people who are motivated by the egosystem can act in prosocial ways “not because they genuinely care about others’ well-being and want to be constructive and supportive, but instead as a strategy to manage others’ impressions” (p. 52).

While intriguing, this idea has not been tested extensively in the psychological literature. The study of altruism has mostly focused on the positive benefits of altruism, and how humans are wired to care for the welfare and suffering of others ( Keltner, 2009 ; Vaillant, 2009 ; Ricard, 2013 ). However, as Bachner-Melman and Oakley (2016) note, “Western societies have become so focused on its benefits that its flip side has been virtually ignored” (p. 92). Examples of pathological altruism range widely from genocide, suicide martyrdom, to codependency ( Oakley et al., 2012 ).

Early psychoanalytical writings focused on the dark side of altruism, and the selfish motives that can underlie it. Anna Freud introduced the concept of altruistic surrender to describe a situation in which a person who is unable to achieve direct gratification of instinctual wishes can achieve vicarious gratification through a proxy ( Freud, 1946 ). Anna Freud saw a prime illustration of altruistic surrender in the drama character of Cyrano de Bergerac; a poet of exceptional talent, but unblessed in physical appearance. Cyrano is in love with his beautiful cousin Roxane, but afraid of her rejection, and thus surrenders his own desires to another man, helping him to win Roxanes’ heart by writing love letters.

While Anna Freud thought of altruism as mostly synonymous with altruistic surrender, later work in psychoanalytic theory acknowledged the healthy functions of altruism. Vaillant (1977) argued that altruism is one of the healthiest defense mechanisms and found that it predicted lifelong positive relationships and personal fulfillment. Nevertheless, Vaillant’s clinical examples of altruism were similar to Anna Freud’s description of altruistic surrender, a compromise of need deprivation resulting in finding a proxy in whom to satisfy one’s own impulses and fantasies ( Seelig and Rosof, 2001 ).

More recent psychoanalytic theory has more carefully and explicitly distinguished between healthy altruism and pathological altruism ( Seelig and Rosof, 2001 ). Presenting a more comprehensive system of classification, Seelig and Rosof (2001) argued that mature and healthy altruism —“the ability to experience sustained and relatively conflict-free pleasure from contributing to the welfare of others” can be distinguished from pathological altruism , “a need to sacrifice oneself for the benefit of others.” They argue that the individual with healthy altruism can gratify their needs directly, regulate their affect, and also enjoy enhancing the good of others.

A big boon to the understanding of the science of pathological altruism came with the publication of the edited volume “Pathological Altruism” in 2012 ( Oakley et al., 2012 ). In this book and a subsequent article ( Oakley, 2013 ), the authors make a call to subject altruism to more systematic scientific inquiry. Oakley et al. (2012) brought a wide variety of perspectives to bear on pathological altruism, from sociology to evolutionary biology to clinical psychology. As Oakley (2013) put it, “it is time for dispassionate exploration of how altruism and empathy themselves can inadvertently bias our efforts to create truly co-operative modern, complex societies.” (p. 2)

In a later book chapter, Bachner-Melman and Oakley (2016) defined pathological altruism as “the willingness of a person to irrationally place another’s perceived needs above his or her own in a way that causes self-harm” (p. 92). They argued that major motivations in healthy altruism are openness to new experiences and a desire for personal growth, whereas the major motivation for individuals with pathological altruism is to please others, gain approval, and avoid criticism and rejection. They gave examples of individuals with eating disorders, codependency in relationships, political extremism, and even cancer caregiving (“those whose care for cancer patients reaches self-harming extremes turn out, interestingly, to be unable to comfortably receive care themselves”, p. 93).

Bachner-Melman and Oakley (2016) also linked pathological altruism to narcissism, arguing that “narcissism and altruism may in fact represent two sides of the same coin” (p. 99). In particular, they linked pathological altruism to “hypervigilant narcissism” (more commonly referred to in the modern scientific literature as vulnerable narcissism; see Kaufman et al., 2018 ). According to the researchers, at the core of the inner world of those with pathological altruism is a deep sense of shame related to their secret wish to display themselves and their needs in a grandiose manner. Stemming from a lack of a sense of self, attention is continually directed toward others, reading, anticipating, or attempting to guess others’ needs and giving them priority over their own real needs.

Developmentally, Bachner-Melman and Oakley (2016) drew on the work of Heinz Kohut, who argued that healthy development requires having one’s needs appreciated or “mirrored” in the eyes of significant others. Kohut argued that if such mirroring is not met early in life, an exaggerated need for responsiveness from others develops, and a healthy sense of self-esteem is less likely to be established ( Kohut, 1971 ). Such children may grow ashamed of their desire to be seen and valued, and ashamed of their dependence on others for support. They may attempt to lighten that burden and shame by being as undemanding as possible and a brittle facade of self-sufficiency sets in as a result. Underneath the facade, however, often lies anger, frustration, and resentment at having to sacrifice so much and receive so little in return.

It’s an interesting and open question whether a reliable and valid scale of pathological altruism would show strong correlations with vulnerable narcissism as well as with the early developmental experience of having to substitute one’s own needs for the needs of others.

Current Studies

To construct new scales of pathological altruism and healthy selfishness, we mined descriptions of these concepts from Fromm (1939) , Maslow (1943/1996) , Oakley et al. (2012) , Oakley (2013) , and Bachner-Melman and Oakley (2016) . Based on the theoretical arguments of these writers, we could make some predictions.

In terms of healthy selfishness, we expected healthy selfishness to show moderately negative correlations with pathological altruism, but to not simply be the opposite of pathological altruism. In particular, we predicted that healthy selfishness would be more strongly tied to sociality, positive relationships, and other dimensions of well-being than pathological altruism. To highlight the paradoxical nature of healthy selfishness, we also predicted that healthy selfishness would be positively correlated with prosocial traits (e.g., the light triad; see Kaufman et al., 2019 ) and prosocial motivations (a genuine satisfaction for helping others), and to be distinct from other forms of unmitigated agency (overdominance and control over others; Helgeson and Fritz, 1999 ) such as measures of narcissism and other forms of unhealthy selfishness.

We expected pathological altruism to be fundamentally motivated by selfish concerns, but for those selfish concerns to be primarily about a fear or rejection and fear of losing emotional intimacy stemming from low self-esteem rather than the more grandiose narcissistic motives for exploitation, power, and control over others. In particular, we predicted that pathological altruism would be correlated with low self-esteem and high vulnerable narcissism as well as higher levels of communally oriented aspects of narcissism including self-sacrificing self-enhancement ( Pincus et al., 2009 ) and communal narcissism ( Gebauer et al., 2012 ), but show weaker correlations with grandiose narcissism overall and more exploitative selfish motivations (which we refer to as “unhealthy selfishness”). Due to the pathological nature of the construct, we also expected pathological altruism to be more strongly tied to negative outcomes such as depression than the abundance of well-being.

Finally, we expected both healthy selfishness and pathological altruism to show ties to unmitigated communion ( Helgeson, 1994 ; Fritz and Helgeson, 1998 ; Helgeson and Fritz, 1999 ). Fritz and Helgeson (1998) demonstrated that unmitigated communion—over-involvement in the problems and suffering of others— is distinct from communion in terms of a negative view of the self, turning to others for self-evaluative information, and psychological distress. They found that those scoring higher in unmitigated communion tended to show higher levels of psychological distress due to their reliance on others for self-esteem and validation, which led to overinvolvement with others and a neglect of the self. They also found that those scoring high in unmitigated communion scored higher in intrusive thoughts about the problems of others, pointing to a compulsive nature of unmitigated communion.

Considering that the Unmitigated Communion Scale includes a mix of items relating to self-neglect (“I always place the need of others above my own”) and an overconcern with the problems of others (“I worry about how other people get along without me when I am not there”; Fritz and Helgeson, 1998 , p. 140), we expected that pathological altruism would show a strong positive correlation with unmitigated communion and healthy selfishness would show a moderate negative correlation with unmitigated communion. However, we expected that pathological altruism and healthy selfishness would predict important outcomes above and beyond unmitigated communion.

One criticism of the Unmitigated Communion Scale is that it does not adequately differentiate between different underlying motives for self-sacrifice ( Bassett and Aubé, 2013 ). Indeed, Helgeson and Fritz (1999) admit this when they write that “some unmitigated communion individuals’ involvement in other people’s problems may be motivated by a need to have control over relationships, as relationships can be a source of self-esteem” (p. 155). Bassett and Aubé (2013) attempted to distinguish between self-sacrifice that is motivated by concern for others versus self-sacrifice that is motivated by concern for the self. They gave participants the Unmitigated Communion Scale and then asked them to rate their underlying motive for their answer to each item. They showed that it is possible to score high in unmitigated communion for different reasons: it’s possible to score high in unmitigated communion for self-oriented reasons (being motivated by a desire to feel affirmed or valued by others) or score high in unmitigated communion for other-oriented reasons (being motivated by a genuine care and concern for the well-being of others). They found that other-oriented motives for unmitigated communion predicted higher levels of secure attachment whereas self-oriented motives for unmitigated communion were related to a preoccupied attachment style (which consists of negative views of the self and a positive view of others) and shame.

Their study highlighted the importance of considering the motivation underlying behavior rather than just the behavior itself. In the current study, we expected that pathological altruism would be more clearly related to selfish motivations for helping others as well as maladaptive psychological adjustment (e.g., fear, depression) than unmitigated communion, and that healthy selfishness would be more clearly tied to prosocial motivations for helping others as well as healthy sociality and overall psychological adjustment (including positive relationships and life satisfaction) than unmitigated communion.

Study 1: Scale Development

The aim of Study 1 was the item selection and initial validation of the healthy selfishness (HS) and pathological altruism (PA) scales, especially concerning measures that are closely conceptually related. We selected items on the basis of conceptual considerations, psychometric characteristic, and exploratory factor analysis. Validity was assessed with respect to conceptually related constructs, particularly unmitigated communion, and indicators of adaptive and maladaptive psychological adjustment (low levels of life satisfaction and high levels of depression).

Participants and Procedure

An online sample of N = 370 (171 female) English-speaking participants was acquired via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform. Data from participants who failed our attention checks were removed from further analysis. The large majority of participants (76%) reported residing in the United States during the time of testing. The mean age was 37.67 years ( SD = 12.29). Among the full sample, 70.3 % self-identified as Caucasian, 8.1% as Hispanic, and 4.9% as African American; the rest did not disclose their ethnical origin. Concerning educational status, one participant (0.30%) did not complete high school, 27.80% of participants completed high school, 71.80% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Participants gave written informed consent to the study, took part on a voluntary basis, and received monetary compensation. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

The main aim of Study 1 was item selection for the HS and PA scales. For this, we administered an initial pool of 16 candidate items designated to assess HS, and candidate 19 items for the assessment of PA. The items were constructed by the first author on the basis of conceptual considerations outlined in the introduction section. Participants answered the items on a five-point scale ranging from “Disagree strongly” to “Agree strongly.”

Additionally, participants completed measures of unmitigated communion (original 8-item unmitigated communion scale; Helgeson, 1993 ), the light triad of personality (12-item scale assessing Kantianism, Humanism, and Faith in Humanity which can be scored as a general light triad factor; Kaufman et al., 2019 ), life satisfaction (5-item The Satisfaction with Life Scale; Diener et al., 1985 ), and depression (20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale, CES-D ( Radloff, 1977 ). We used those latter two scales as proxies for adaptive and maladaptive psychological adjustment, paralleling the more comprehensive analyses in Study 2 (see below).

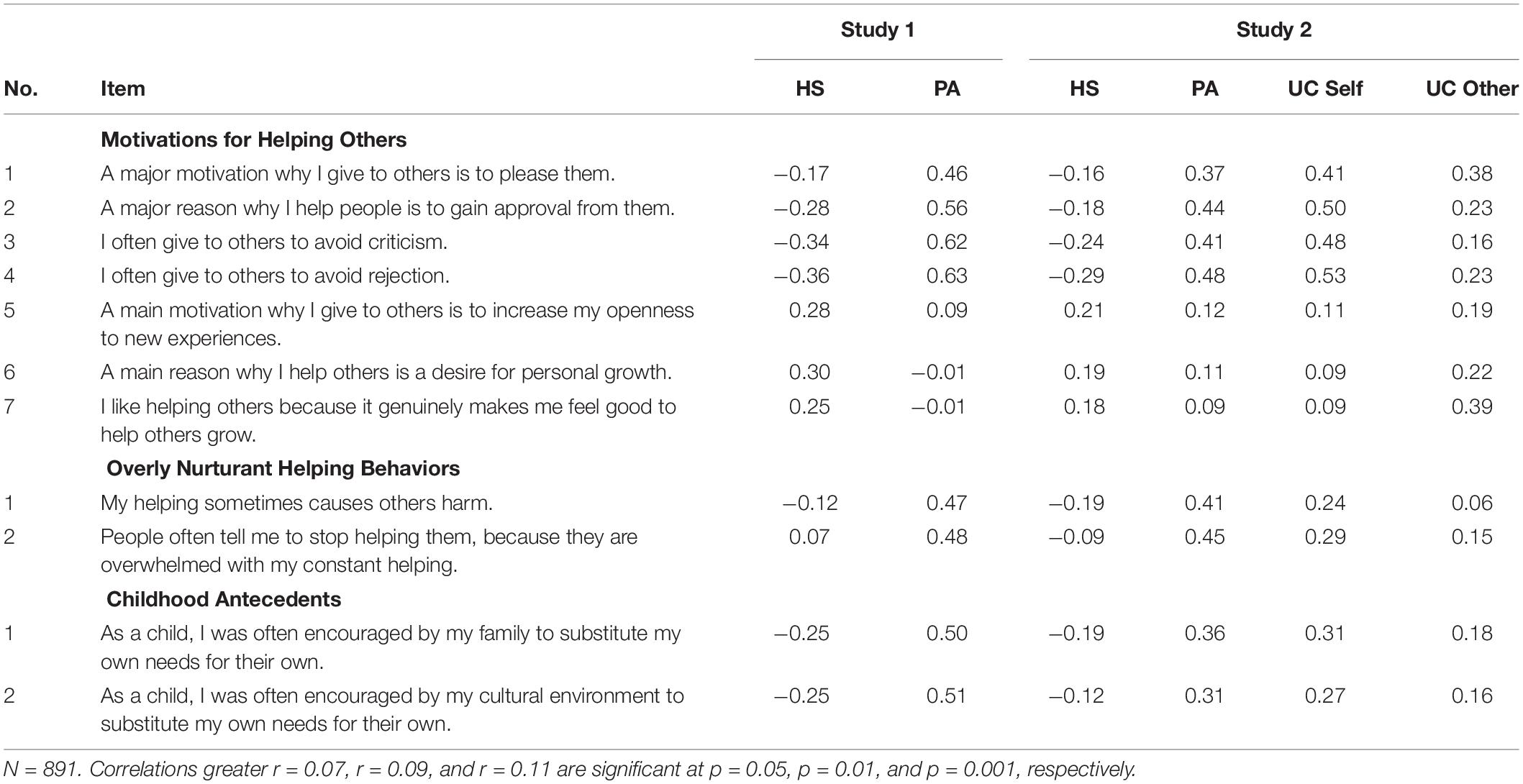

Additionally, we also administered seven newly devised items measuring underlying motivations for helping others (e.g., “A major reason why I help people is to gain approval from them”) and two newly devised items assessing possible childhood antecedents that might differentiate between HS and PA (e.g., “As a child, I was often encouraged by my family to substitute my own needs for their own”). The percentage of missing data in this pilot study was low, not exceeding 1% on any single variable.

Item Selection

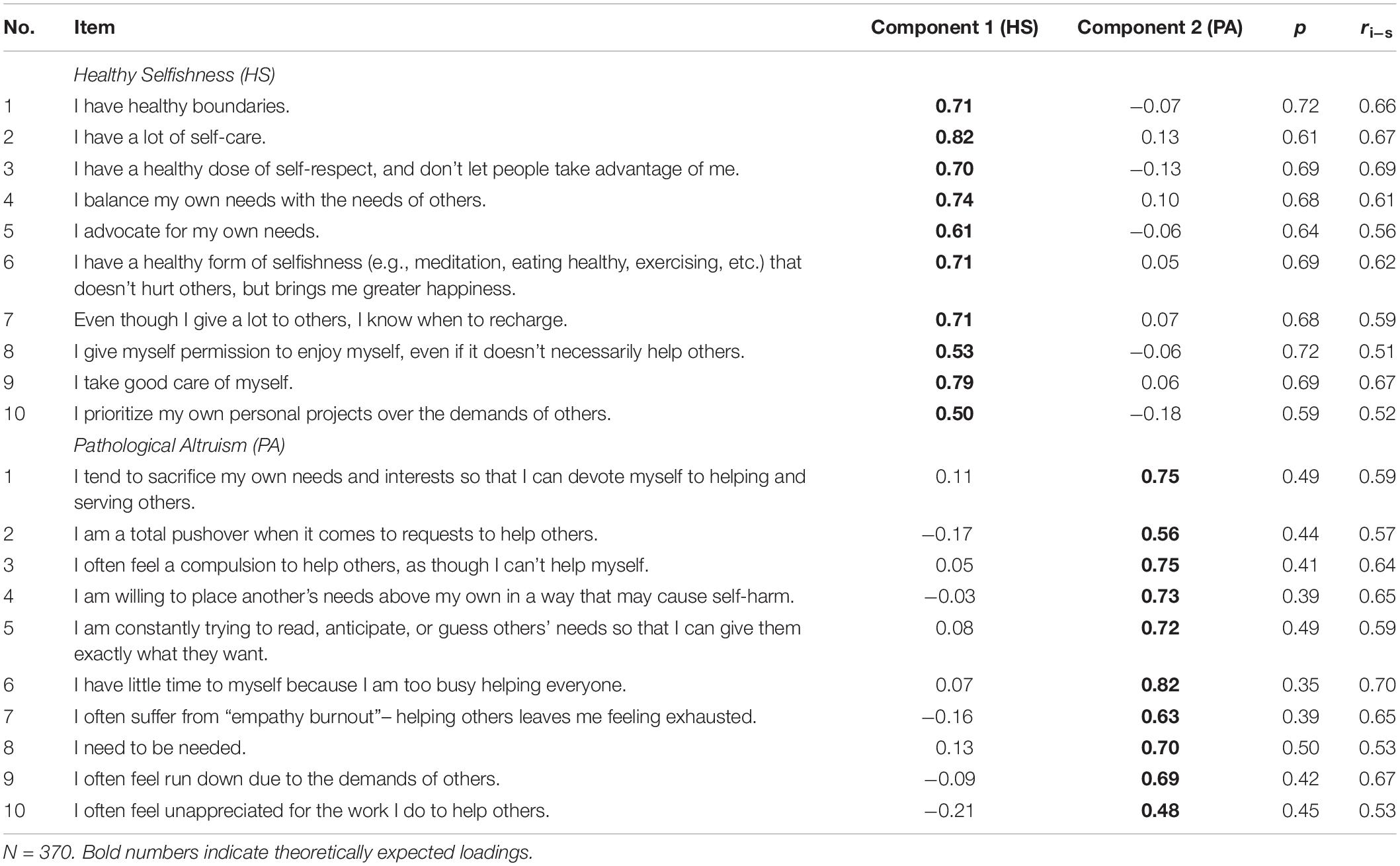

Almost all items from the initial HS and PA item pool displayed psychometrically satisfactory difficulty between p = 0.20 and 0.80 (0.21 < p < 0.74; see Table 1 ); we excluded one PA item which did not meet this criterion ( p = 0.19; “my helping sometimes causes others harm”).

Table 1. Principal component analysis and item-level statistics of the Healthy Selfishness and Pathological Altruism scales in Study 1.

The HS items displayed high initial item-scale correlations (0.43 < r i–s < 0.68), with the exception of one item ( r = 0.37; “I notice when there are problems in my relationships and I try to fix the situation”), which we excluded. We further excluded five items which were conceptually less clear and distinctive than the others (e.g., “I ask for help when I’m feeling low” or “I look after myself so that I can better help others”). The remaining item-scale correlations were 0.51 < r i–s < 0.69 (see Table 1 ). The internal consistency of the 10-item scale was α = 0.88. The scale skewness indicated a long left tail ( z = −5.34, p < 0.001), which means that a greater number of people show higher than lower HS in the present scale. The scale kurtosis conformed to a normal distribution ( z = 1.72, p = 0.08).

Among the PA items, item-scale correlations were also high (0.49 < r i–s < 0.71). Again, we excluded items that were conceptually less clearly related to PA, albeit correlated (e.g., “I try very hard to look attractive, even if I have to sacrifice my own health to do so”). After exclusion of eight items, the final 10-item scale (paralleling the length of the HS scale) displayed item-scale correlations between 0.53 < r i–s < 0.70 (see Table 1 ), similar to the HS scale. The overall internal consistency was α = 0.88, just like the HS scale. The scale skewness conformed to normality ( z = −1.97, p = 0.05), and scale kurtosis indicated a platykurtic distribution ( z = −3.45, p < 0.001).

Factor Structure

We conducted a principal components analysis to validate the intended factor number of the HS and PA scales. Velicer’s (1976) original and revised ( Velicer et al., 2000 ) MAP test indicated a two-factor solution. The first principal component accounted for 35.82% of variance, the second for 13.30%. The component correlation after Promax rotation was r = −0.45, indicating that the components underlying HS and PA are moderately anticorrelated. The components clearly distinguished HS and PA items, with intended loadings ≥ 0.48 and cross-loadings ≤ 0.21 (see Table 1 ). Thus, the analysis clearly confirms the intended two-factor structure of the HS and PA scales (a further confirmatory analysis is provided in Study 2).

External Validity

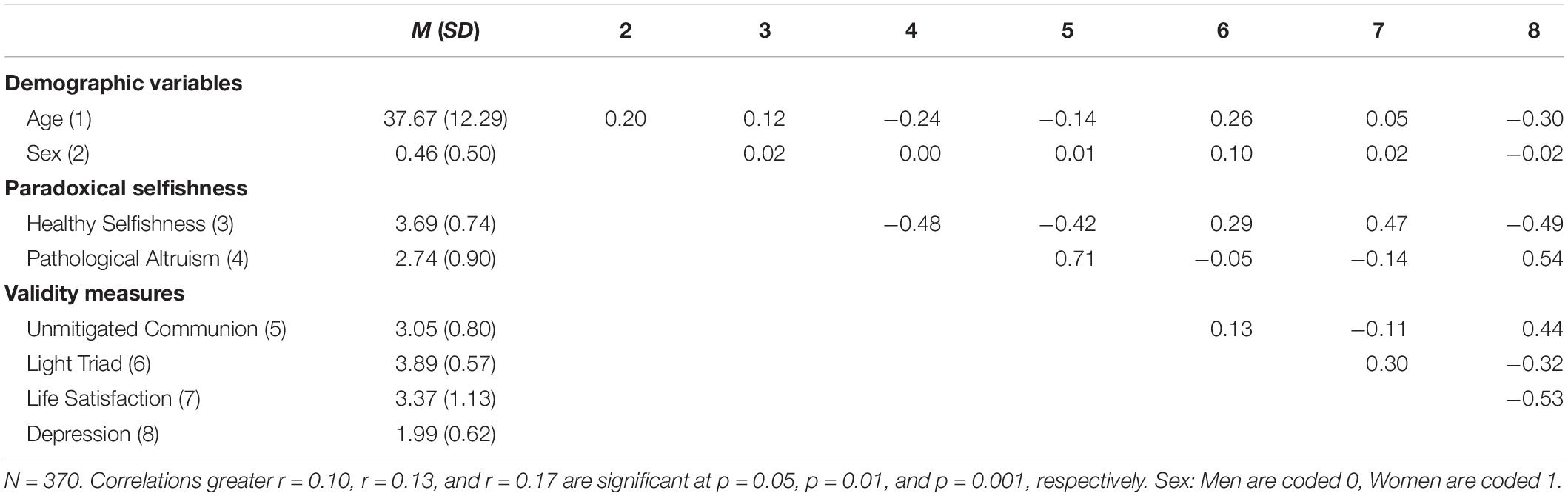

Table 2 displays the correlations between HS and PA, demographical variables, and other variables assessed in this study. HS displayed a slight positive association with participants’ age, PA displayed a negative association. None of the two forms of paradoxical selfishness were associated with participants’ sex.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations of Study 1 variables.

HS and PA were moderately negatively correlated, paralleling the principal components correlation reported above. We expected PA to be positively correlated with unmitigated communion, whereas HS should be negatively related. HS and PA should further display opposing relationships with the light triad, life satisfaction, and depression. As expected, PA displayed a high positive correlation with unmitigated communion, while HS displayed a negative relationship. HS was further positively correlated with the light triad, highly positively correlated with life satisfaction, and highly negatively related to depression. PA displayed a slight negative association with life satisfaction, and a rather strong positive association with depression.

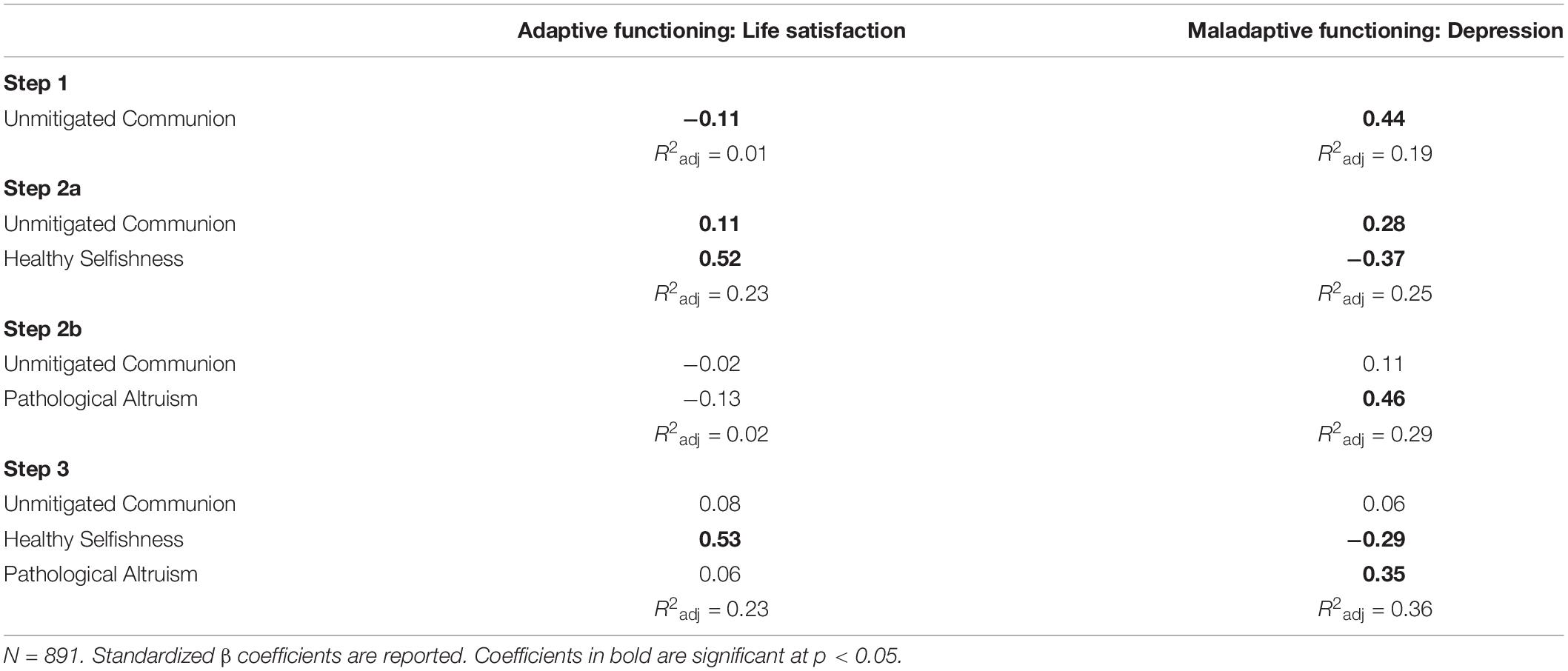

We had a-priori interest in the predictive power of the HS and PA scales on measures of adaptive and maladaptive psychological adjustment (in Study 1: life satisfaction and depression). To investigate the incremental validity of the HS and PA scales beyond unmitigated communion, we conducted hierarchical multiple regression models for the prediction of life satisfaction as an indicator of adaptive psychological functioning, and depression as an indicator of maladaptive functioning. We used unmitigated communion and HS/PA as predictor variables and investigated the effects of unmitigated communion alone (step 1: equals zero-order correlations from Table 2 ), steps 2a, b: unmitigated communion and HS/PA, and step 3: unmitigated communion, HS, and PA).

Table 3 displays the results. In step 1, unmitigated communion displayed a slight negative relationship with life satisfaction and a strong positive association with depression. When we entered HS in step 2a, we found HS to be a strong predictor of life satisfaction and depression, and the effects of unmitigated communion were still significant. When entering PA in step 2b, we observed no significant effects on life satisfaction. PA was the only significant predictor of depression. This pattern was reflected in step 3, which shows that when all variables are considered simultaneously, HS is the only predictor of life satisfaction, and PA is the strongest predictor of depression (though HS is also a strong predictor, although in the opposite direction).

Table 3. Hierarchical multiple regression models for the prediction of psychological functioning indicators in Study 1.

These results demonstrate first evidence for the incremental validity of (HS and) PA above and beyond unmitigated communion, which is important as these are conceptually and empirically related. While these results yield first evidence for convergent and discriminant validity, Study 2 will consider a larger set of external validity measures, more finely differentiating the motives associated with HS and PA.

Study 2: Scale Validation

The aim of Study 2 was to validate the structure of the newly devised HS and PA scales using confirmatory factor analysis as well as external validity measures in a large sample. To this end, we included a manifold of conceptually related variables to test convergent and discriminant validity. Findings from Study 1 were replicated using more fine-grained measures of the respective constructs. Moving beyond Study 1, we also included an interpersonal circumplex measure to assess the relations of HS and PA with agentic and communal orientations and included a broader array of criterion measures for adaptive psychological adjustment (a multidimensional scale of well-being in addition to life satisfaction) and maladaptive adjustment (a multidimensional scale of fears in addition to depression).

We acquired an online sample of N = 891 (472 female, 2 non gender-identified) participants via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Data from participants who failed our attention checks were removed from further analysis. The large majority of participants (89%) resided in the United States during the time of testing. The mean age was 37.12 ( SD = 11.30) years; 0.80% (seven participants) did not complete high school, 42.30% completed high school, 56.90% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. The research reported here is part of a larger project on personality; part of the data were previously published and the study procedure was described in greater detail ( Jauk and Kaufman, 2018 ). The study was carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The protocol was approved by the Ethics committee of the University of Pennsylvania. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants received monetary compensation.

We used the same pool of HS and PA items as in Study 1. Analyses are based on the item selection of Study 1 resulting in 10 items per scale (see Table 1 ). As in Study 1, we assessed life satisfaction (The Satisfaction with Life Scale; Diener et al., 1985 ), a modified scale of unmitigated communion that distinguishes self- and other-oriented unmitigated communion (18-item Two-Dimensional Unmitigated Communion Scale, TUCS; Bassett and Aubé, 2013 ), and depression (CES-D; Radloff, 1977 ). Additionally, the validation study encompassed a brief measure of the Big Five (Ten-Item Personality Inventory, TIPI; Gosling et al., 2003 ), a measure of self-esteem (16-item Self-Liking/Self-Competence Scale-Revised Version SLCS-R; Tafarodi and Swann, 2001 ), pathological selfishness (Selfishness Questionnaire, SQ; Raine and Uh, 2018 ), the Light Triad (Light Triad Scale; Kaufman et al., 2019 ), grandiose and vulnerable narcissism (Five Factor Narcissism Inventory Short Form FFNI-SF; Sherman et al., 2015 ), the Self-Sacrificing Self-Enhancement subscale of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI; Pincus et al., 2009 ), communal narcissism ( Gebauer et al., 2012 ), the core motives of achievement, power, affiliation, and intimacy (Unified Motive Scales UMS; Schönbrodt and Gerstenberg, 2012 ), authentic and hubristic pride ( Tracy and Robins, 2007 ), psychological well-being (42-item version of Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale; see for instance Abbott et al., 2006 ), and fear (fear of failure, rejection, losing control, losing emotional contact, and losing reputation from the Unified Motive Scales UMS, which can be aggregated to a composite index; Schönbrodt and Gerstenberg, 2012 ). We assessed the interpersonal circumplex scales using the International Personality Item Pool–Interpersonal Circumplex (IPIP-IC; Markey and Markey, 2009 ). Lastly, as in Study 1, we administered the same set of items assessing motivation for helping others and childhood antecedents of HS and PA.

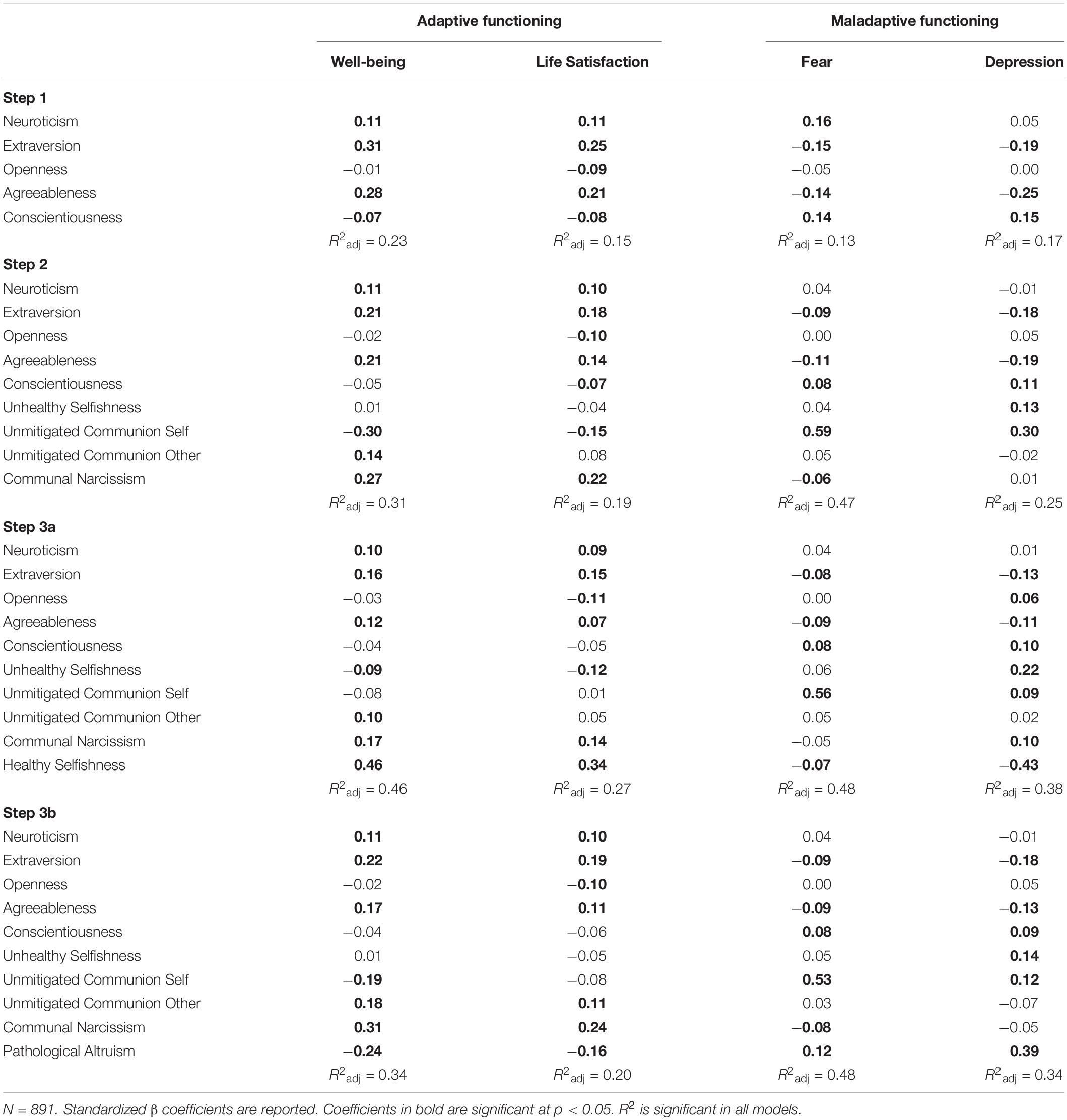

Data-Analytical Strategy

We first re-assessed the factor structure of the HS and PA scales using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We then examined correlations to validity measures and to the Interpersonal Circumplex. As the sample is large and almost all correlations are significant at conventional levels, we focus on effect sizes rather than significance levels in the interpretation of results. Next, we investigated the validity of the HS and PA scales on measures of adaptive psychological adjustment (psychological well-being, life satisfaction) and maladaptive adjustment. To this end, we tested the incremental validity of the HS and PA scales above and beyond the Big Five and conceptually related constructs, namely unhealthy selfishness, unmitigated communion (self- and other-directed), and communal narcissism, on the criterion variables psychological well-being, life satisfaction, fear, and depression. These criterion measures tap into the positive and negative poles of general psychological functioning.

We expected that that HS scale would be more predictive of positive psychological adjustment (well-being, life satisfaction), whereas the PA scale would be indicative of psychological maladjustment (fear, depression). Lastly, we investigated the relations between motivation for helping others and the childhood antecedents of HS and PA across both studies.

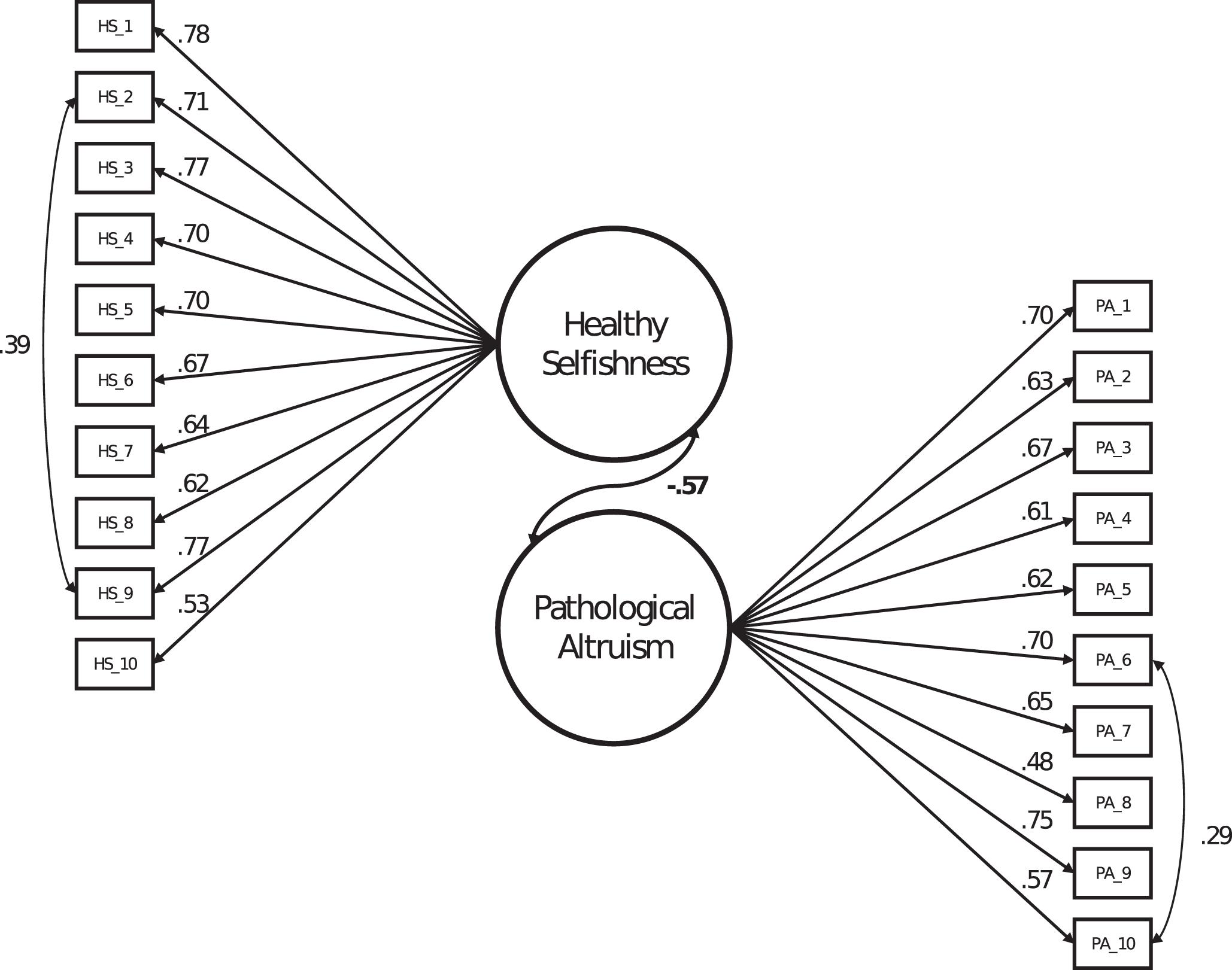

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

We conducted CFAs separately for the HS and PA scales and jointly for both scales. Since the results for the single models and the joint model were very similar, we only present the joint CFA of both scales here. The model converged to an admissible solution and displayed acceptable fit to the data (χ 2 (167) = 850.38, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.82; SRMR = 0.05). While the χ 2 test was significant, which might be due to its high sensitivity in large samples, the other indices can be deemed acceptable 1 . As Figure 1 shows, factor loadings were high and consistent. The explained variance in the single indicators was significant for each item ( p < 0.001). We specified one residual correlation per scale to account for unique variance between the items. Importantly, there were no substantial cross-loadings of items or residual correlations between scales (i.e., specifying such effects would not have improved model fit substantially). This confirms the EFA results of Study 1. The latent correlation between the HS and PA factors was r = −0.57, also conforming to the result of Study 1.

Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis model of the Healthy Selfishness and Pathological Altruism scales. Error variables are not displayed.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

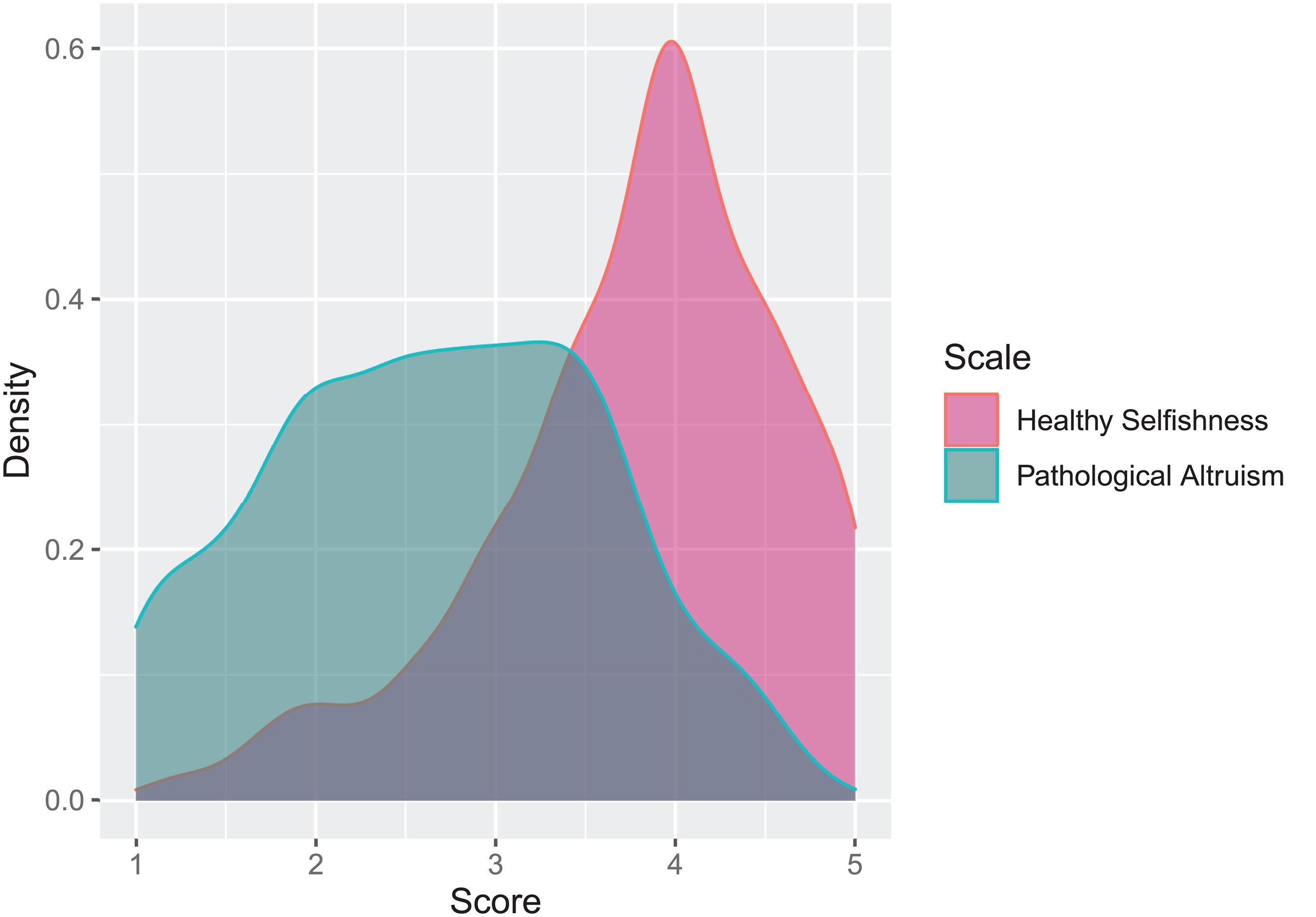

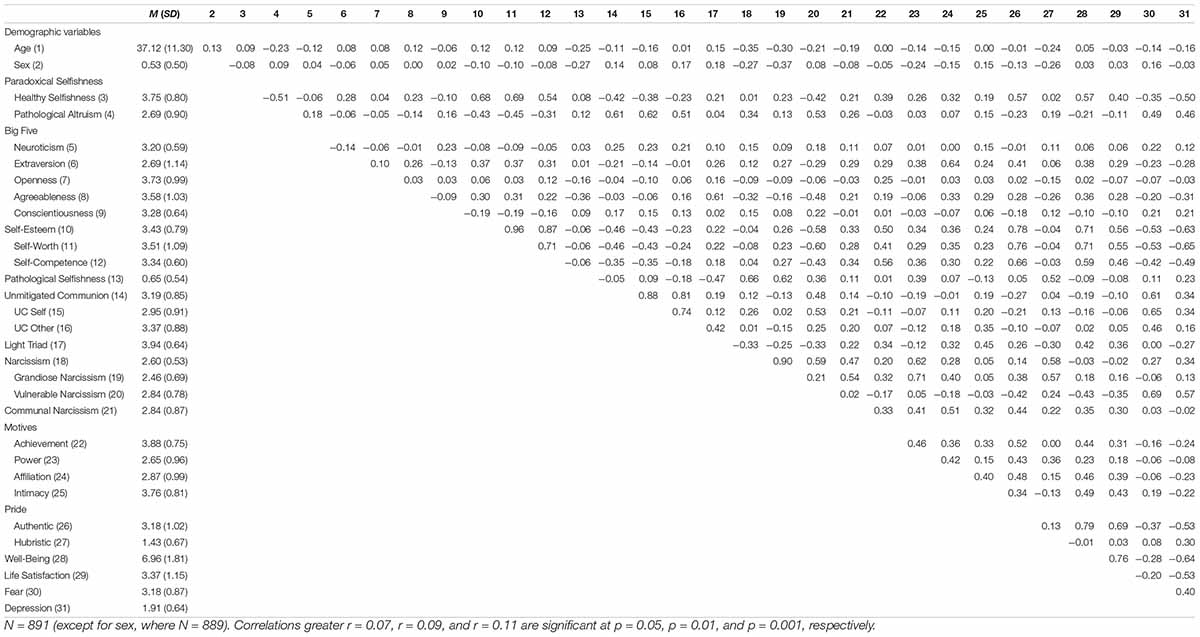

Figure 2 displays the distributions of the HS and PA scales. As in study 1, the HS scale displayed a long left tail, indicating that the majority of participants displayed higher rather than lower HS. The PA scale, also as in Study 1, displayed a platykurtic distribution. Table 4 displays the descriptive statistics and correlations between the HS and PA scales with demographic variables, Big Five personality dimensions, conceptually related personality constructs, and indicators of adaptive and less adaptive psychological functioning. The means and SD s of the HS and PA scales were almost identical to Study 1. Also, the correlations to age and sex, unmitigated communion (overall), life satisfaction, and depression were highly similar to those obtained in Study 1. Among the Big Five personality traits, HS was positively associated with extraversion and agreeableness, whereas PA was, albeit to a lesser extent, associated with neuroticism and disagreeableness. Both showed weak associations with conscientiousness in opposing directions.

Figure 2. Density distributions of the Healthy Selfishness and Pathological Altruism scales in Study 2. N = 891.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics and correlations of Study 2 variables.

Among the further effects displayed in Table 4 , it is interesting to note that HS was substantially positively related to self-esteem (particularly the self-liking facet) whereas PA was negatively related to both facets of self-esteem (self-liking and self-competence). Neither HS nor PA were markedly associated with pathological selfishness, suggesting that HS and PA are both independent from an exploitative form of selfishness.

Also as expected, PA was strongly related to unmitigated communion (somewhat stronger with self-oriented unmitigated communion), whereas HS was negatively related to both self-oriented and other-oriented motivations underlying unmitigated communion. To further disentangle these effects, we conducted complemental regression analyses using self- and other-oriented unmitigated communion as predictors of HS and PA. These show that when both motivations underlying unmitigated communion are considered simultaneously, there was a strong negative effect of self-oriented unmitigated communion on HS (β = −0.45, p < 0.001), whereas other-oriented unmitigated communion had only a weak effect (β = 0.10, p = 0.03). A similar picture emerged for PA, where self-related unmitigated communion was a strong positive predictor (β = 0.55, p < 0.001), whereas other-oriented unmitigated communion was not (β = 0.10, p = 0.011). The predictive validity of PA and unmitigated communion will be evaluated below.

As in Study 1, HS was correlated with the Light Triad Scale, whereas PA was not. HS was not related to overall narcissism and only weakly correlated with grandiose narcissism, which provides evidence for its conceptual distinctiveness, and, as expected, was negatively correlated with vulnerable narcissism. On the contrary, PA was moderately related to overall narcissism, which was mainly due to the strong correlation with vulnerable narcissism. This is in line with the correlations of PA with neuroticism and disagreeableness (antagonism) observed among the Big Five. However, as we did not expect the correlation between PA and vulnerable narcissism to be so high, we conducted an exploratory analysis between PA and the 15 FFNI subscales. The highest correlations emerged between PA and the subscales Need for Admiration ( r = 0.53, p < 0.001), Shame ( r = 0.47, p < 0.001), and Entitlement ( r = 0.36, p < 0.001). Of note, PA was weakly negatively correlated with a Lack of Empathy (r = −0.10, p < 0.001). PA was also substantially correlated with the Self-Sacrificing Self-Enhancement Scale ( r = 0.45, p < 0.001) of the PNI ( Pincus et al., 2009 ). Further, HS and PA were both significantly related to communal narcissism ( r HS, communal = 0.21, p < 0.001; r PA, communal = 0.29, p < 0.001). Taken together, the pattern of correlations shows that PA taps more into vulnerable narcissism and communal-oriented aspects of narcissism than overall grandiose narcissism, while HS is negatively related to vulnerable narcissism and only slightly positively related to more grandiose forms of narcissism.

Among the core motives, HS was moderately positively associated with achievement, power, and affiliation, whereas PA displayed no pronounced associations with the core motives. Paralleling the finding of an independence of HS from narcissism, HS was strongly associated with authentic pride, but not with hubristic pride. In contrast (and also in line with the narcissism findings), PA was negatively related to authentic pride and even displayed a small positive association with hubristic pride.

Concerning indicators of psychological functioning, as expected, HS was positively related to adaptive functioning in terms of psychological well-being and self-esteem, whereas PA was negatively related to those indicators. PA was, instead, positively associated with indicators of maladaptive functioning in terms of fear and depression. Complemental facet-level analyses for fear yielded largely homogeneous correlations with HS and PA. When we controlled for the shared variance among the different fears using multiple regression models, HS displayed a negative relationship with fear of rejection (β = −0.39, p < 0.001), and, to a lesser extent, failure (β = −0.17, p < 0.001), and losing control (β = −0.10, p = 0.02), whereas it was positively associated with fear of losing reputation (β = 0.20, p < 0.001). PA displayed positive associations with fear of losing control (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), losing emotional contact (β = 0.20, p < 0.001), and rejection (β = 0.15, p < 0.001). Incremental validity of the HS and PA scales on measures of adaptive and maladaptive functioning beyond other personality constructs will be tested below.

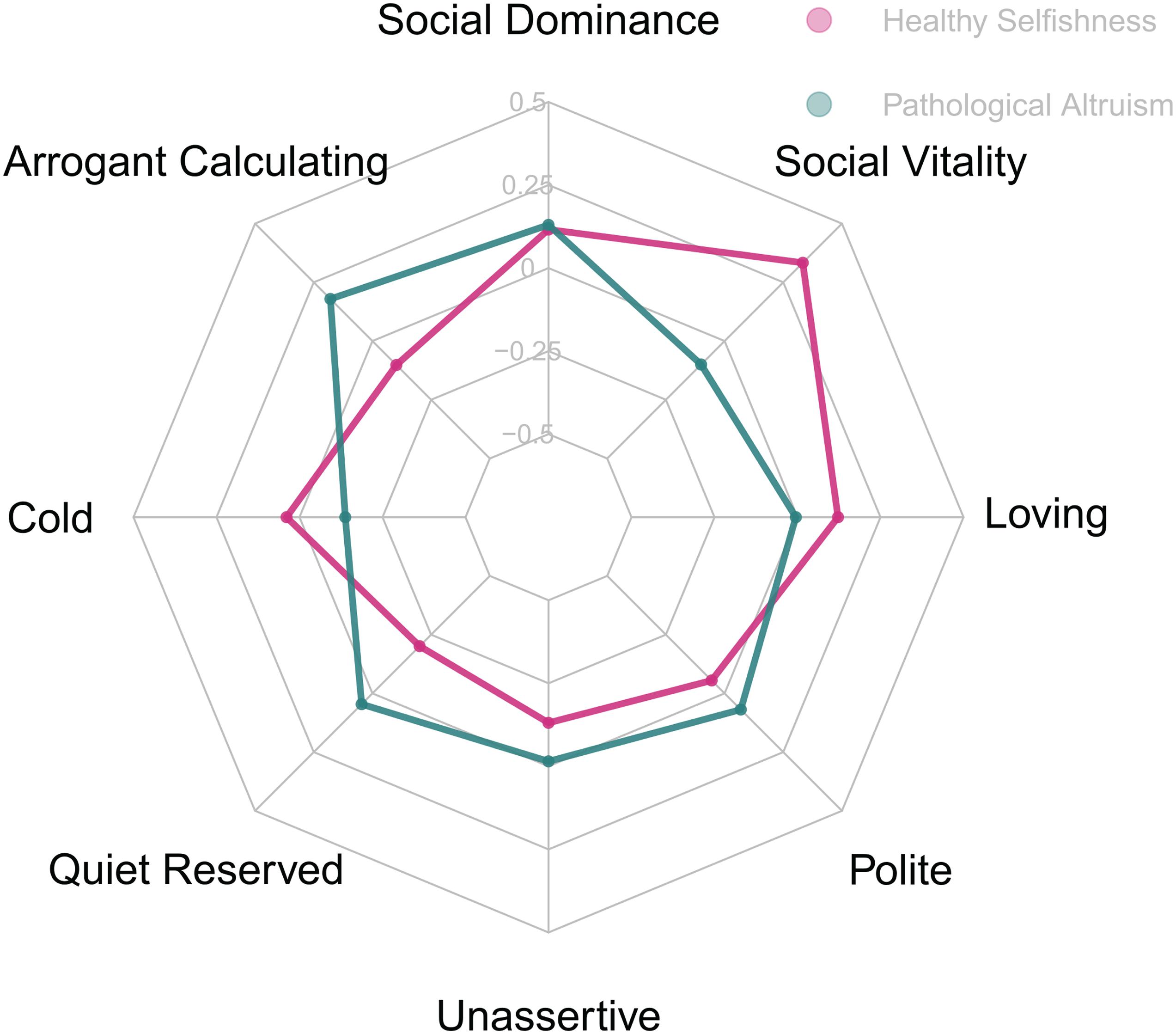

Interpersonal Circumplex

Figure 3 displays the associations between HS and PA and the scales of the interpersonal circumplex. The HS scale displayed the strongest associations with social vitality ( r = 0.33), and, negatively, quietness and reservedness ( r = −0.20). HS was thus associated with a friendly assertive interpersonal style. PA was less clearly associated with a particular interpersonal style. Consistent with the paradoxical nature of PA, we observed the strongest positive associations with arrogant/calculating ( r = 0.18) and social dominance ( r = 0.13), and the strongest negative association with cold-heartedness ( r = −0.14). However, note that all of these associations were rather weak. Taken together, it can be concluded that HS is associated with a friendly assertive interpersonal style, whereas PA was less clearly linked to the interpersonal circumplex.