All Training Courses

Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) – Certified Tier 1 Training

The CPS approach focuses on building helping relationships and teaching at-risk kids the skills they need to succeed across a variety of different settings. It is a strengths-based, neurobiologically-grounded approach that provides concrete guideposts so as to operationalize trauma-informed care and empower youth and family voice.

- Course Information

- Download Course PDF.

Description

Collaborative Problem Solving is an evidence-based approach to understanding and helping children and adolescents with a wide range of social, emotional, and behavioural challenges.

Participants learn to advance their skills in applying the model through a combination of didactic lectures, role-playing, videotape examples, case presentations, and breakout groups with topics of specific interest to clinicians and educators. Participants receive personal attention and individualized feedback during breakout sessions from Think:Kids trainers while also benefiting from opportunities for networking.

Participants must attend all days to be considered for certification. Completion of the training is also a requirement of the professional certification program.

Additional Topics Include:

- Strategies for when a child refuses or has difficulty expressing his/her concerns.

- Dealing with common resistances to the approach.

- Troubleshooting other barriers to implementation in systems.

- Integrating with other models (i.e. Positive Behavioural Supports).

- Implementation in groups such as classrooms and transforming system-wide disciplinary policies.

Learning Outcomes

- Gain in-depth exposure to both the assessment and intervention components.

- Practice drilling down to identify specific problems to be solved.

- Practice identifying the specific cognitive skill deficits contributing to challenging behaviour.

- Learn how to solve problems and train skills using the collaborative problem-solving process.

- Practice indirect skills training with personalized feedback from trainers.

- Develop the skills for troubleshooting Plan B.

Who Should Attend

This course is suitable for mental health front-line staff, clinicians and educators interested in becoming proficient in Collaborative Problem Solving.

Course Dates & Format

There are no scheduled dates for this course at this time, however in-service is available.

This is a 14-hour training. This course is delivered virtually over 4 half days. Attendance is required each day.

Instructors:

Michael Hone

Since 1988, Michael Hone has worked in a variety of settings including child welfare, youth justice, education and child and youth mental health. Currently he is the Executive Director of a Children’s Mental Health Centre in Ottawa, Canada. Michael is one of 2 Master trainers in Canada for Collaborative Problem Solving and is involved with the Advisory Council of Think:Kids at Massachusetts General Hospital. Michael has been committed to implementing the Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) approach across Ontario, and to date has trained approximately 8,000 people in Ontario.

Natasha Tatartcheff-Quesnel

Natasha has worked in child and adolescent services since 1991 in a variety of settings including residential services, secure treatment, youth justice, education, substance abuse, child and youth mental health, as well as in the private sector. She is a bilingual Certified Master Trainer and Consultant for Think:Kids and completed her fellowship for her Master’s in Social Work at Think:Kids in the department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital. She is committed to implementing the CPS approach in Canada and the United States and has trained and provided implementation support to numerous sites. She has also reviewed child and youth mental health systems internationally using the SOCPR and presented on the topic at numerous conferences.

Training Fee

Group Registration: Save 20% off individual fees with a group registration of 4 or more participants. Download the group registration form HERE .

Continuing Education Information

Continuing education credits are offered at no extra cost through Think:Kids, Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Psychiatry.

Licensing boards and professional organizations will grant Continuing Education credits for attendance at their discretion when participants submit the course outline and certificate.

In-Service

This is available as an in-person or virtual in-service training and customized to suit your needs.

Search Courses

Course categories.

- Dual Diagnosis

- Health and Well Being

- Respite Learning Portal

- Sociocultural Perspectives

- Therapeutic Crisis Intervention

- Trauma Assessment & Treatment

- Trauma Focused Intervention

- Trauma-Informed Practice

- Treating Trauma Effects

- Uncategorized

Related Courses

Trauma Informed Care: Supporting Individuals with Developmental Disabilities

Working with Clinically Complex Children and Families, Case-based Consultation

Embrace Trauma-Informed Care with Children and Youth

Jump to content

Psychiatry Academy

Bookmark/search this post.

You are here

Parenting, teaching and treating challenging kids: the collaborative problem solving approach.

- CE Information

- Register/Take course

Think:Kids and the Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital are pleased to offer an online training program featuring Dr. J. Stuart Ablon. This introductory training provides a foundation for professionals and parents interested in learning the evidence-based approach to understanding and helping children and adolescents with behavioral challenges called Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS). This online training serves as the prerequisite for our professional intensive training.

The CPS approach provides a way of understanding and helping kids who struggle with behavioral challenges. Challenging behavior is thought of as willful and goal oriented which has led to approaches that focus on motivating better behavior using reward and punishment programs. If you’ve tried these strategies and they haven’t worked, this online training is for you! At Think:Kids we have some very different ideas about why these kids struggle. Research over the past 30 years demonstrates that for the majority of these kids, their challenges result from a lack of crucial thinking skills when it comes to things like problem solving, frustration tolerance and flexibility. The CPS approach, therefore, focuses on helping adults teach the skills these children lack while resolving the chronic problems that tend to precipitate challenging behavior.

This training is designed to allow you to learn at your own pace. You must complete the modules sequentially, but you can take your time with the content as your schedule allows. Additional resources for each module provide you with the opportunity for further development. Discussion boards for each module allow you to discuss concepts and your own experiences with other participants. Faculty from the Think:Kids program monitor the boards and offer their point of view.

Registrants will have access to course materials from the date of their registration through the course expiration date.

All care Providers: $149 Due to COVID-19, we are offering this course at the reduced rate of $99 for a limited time.

NOTE: If you are paying for your registration via Purchase Order, please send the PO to [email protected] . Our customer service agent will respond with further instructions.

Cancellation Policy

Refunds will be issued for requests received within 10 business days of purchase, but an administrative fee of $35 will be deducted from your refund. No refunds will be made thereafter. Additionally, no refunds will be made for individuals who claim CME or credit, regardless of when they request a refund.

Through the duration of the course, the faculty moderator will respond to any clinical questions that are submitted to the interactive discussion board. The faculty moderator for this course will be:

J. Stuart Ablon, PhD

*** Please note that discussion boards are reviewed on a regular basis, and responses to all questions will be posted within one week of receipt. ***

Target Audience

This program is intended for: Parents, clinicians, educators, allied mental health professionals, and direct care staff.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this program, participants will be able to:

- Shift thinking and approach to foster positive relationships with children

- Reduce challenging behavior

- Foster proactive, rather than reactive interventions

- Teach skills related to self-regulation, communication and problem solving

MaMHCA, and its agent, MMCEP has been designated by the Board of Allied Mental Health and Human Service Professions to approve sponsors of continuing education for licensed mental health counselors in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for licensure renewal, in accordance with the requirements of 262 CMR 3.00.

This program has been approved for 3.00 CE credit for Licensed Mental Health Counselors MaMHCA.

Authorization number: 17-0490

The Collaborative of NASW, Boston College, and Simmons College Schools of Social Work authorizes social work continuing education credits for courses, workshops, and educational programs that meet the criteria outlined in 258 CMR of the Massachusetts Board of Registration of Social Workers

This program has been approved for 3.00 Social Work Continuing Education hours for relicensure, in accordance with 258 CMR. Collaborative of NASW and the Boston College and Simmons Schools of Social Work Authorization Number D 61675-E

This course allows other providers to claim a Participation Certificate upon successful completion of this course.

Participation Certificates will specify the title, location, type of activity, date of activity, and number of AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ associated with the activity. Providers should check with their regulatory agencies to determine ways in which AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ may or may not fulfill continuing education requirements. Providers should also consider saving copies of brochures, agenda, and other supporting documents.

The Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Psychiatry is approved by the American Psychological Association to sponsor continuing education for psychologists. The Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Psychiatry maintains responsibility for this program and its content.

This offering meets the criteria for 3.00 Continuing Education (CE) credits per presentation for psychologists.

Stuart Ablon, PhD

Available credit.

- Online Degree Explore Bachelor’s & Master’s degrees

- MasterTrack™ Earn credit towards a Master’s degree

- University Certificates Advance your career with graduate-level learning

- Top Courses

- Join for Free

Cross Functional Collaboration

Taught in English

Financial aid available

Gain insight into a topic and learn the fundamentals

Instructor: Hector Sandoval

Included with Coursera Plus

Recommended experience

Intermediate level

Should have 3-5 years of experience in roles that require leading, supervising, and managing people and critical processes within organizations.

What you'll learn

Identify challenges, overcome barriers, foster teamwork, and leverage diverse perspectives for effective cross-functional collaboration.

Learn techniques to enhance communication, establish clear channels, and promote active listening and feedback within cross-functional teams.

Strengthen problem-solving skills, analyze different perspectives, and make informed decisions within collaborative efforts.

Utilize techniques for collaborative problem-solving, decision-making, consensus-building, and informed choices as a team.

Skills you'll gain

- conflict resolution

- Communication Enhancement

- Problem-Solving through Collaboration

- Collaborative Strategies

- Teamwork and Cooperation

Details to know

Add to your LinkedIn profile

5 quizzes, 1 assignment

See how employees at top companies are mastering in-demand skills

Earn a career certificate

Add this credential to your LinkedIn profile, resume, or CV

Share it on social media and in your performance review

There is 1 module in this course

Welcome to the "Cross-Functional Collaboration" course! This course focuses on the principles and strategies for collaborating effectively with colleagues from different functional areas. Through this course, you will learn techniques to overcome challenges, foster teamwork, and leverage diverse perspectives to achieve common goals. The course emphasizes the importance of building a culture of trust and cooperation among team members and covers various techniques to improve communication, manage conflicts, and make informed decisions through collaborative efforts.

This course is designed for front-line, junior to mid-level supervisors and manager roles who are responsible for leading teams, projects, and processes in a diverse range of organizations. By the end of the course, you will be equipped with the necessary skills to collaborate successfully with colleagues from different backgrounds and functional areas, leading to enhanced productivity and overall organizational success. To enroll in this course, participants should have 3-5 years of experience in roles that require leading, supervising, and managing people and critical processes within organizations. Join us in developing your collaborative skills and becoming a more effective leader in your organization.

Cross-Functional Collaboration

This course focuses on the principles and strategies for collaborating effectively with colleagues from different functional areas. Students will learn to overcome challenges, foster teamwork, and leverage diverse perspectives to achieve common goals. The course covers various techniques to improve communication and information sharing across departments and develop strategies for managing conflict and resolving disputes. Through case studies and group exercises, students will enhance their problem-solving skills and learn how to make informed decisions through collaborative efforts. The course also emphasizes the importance of building a culture of trust and cooperation among team members. By the end of the course, students will be equipped with the necessary skills to collaborate successfully with colleagues from different backgrounds and functional areas, leading to enhanced productivity and overall organizational success.

What's included

26 videos 2 readings 5 quizzes 1 assignment

26 videos • Total 51 minutes

- Introduction to the course and instructor • 1 minute • Preview module

- Learning objectives and outcomes • 0 minutes

- Overview of different functional areas within organizations • 1 minute

- Common challenges and barriers to cross-functional collaboration • 2 minutes

- Specific examples highlighting real-world collaboration obstacles • 1 minute

- Identifying the role of entry-level supervisors and managers in fostering collaboration • 3 minutes

- Strategies for creating a culture of trust and cooperation • 1 minute

- Creating the right environment • 1 minute

- Techniques for clear and concise communication • 2 minutes

- Active listening and empathy in cross-functional settings • 2 minutes

- Selecting appropriate communication channels • 1 minute

- Leveraging technology for seamless information sharing • 1 minute

- Recognizing sources of conflict in cross-functional teams • 1 minute

- Strategies for managing and resolving conflicts constructively • 2 minutes

- Developing negotiation and problem-solving skills • 2 minutes

- Analytical thinking and critical decision-making in collaborative settings • 1 minute

- Brainstorming techniques for cross-functional teams • 1 minute

- Evaluating potential solutions and making informed decisions • 1 minute

- Recognizing the value of diverse perspectives in cross-functional teams • 1 minute

- Creating an inclusive environment for diverse viewpoints • 0 minutes

- Encouraging creativity and innovation through diverse thinking • 2 minutes

- Techniques for integrating different perspectives for better outcomes • 2 minutes

- Strategies for fostering teamwork and collaboration • 1 minute

- Promoting a sense of shared purpose and goals • 2 minutes

- Recognizing and rewarding collaborative achievements • 3 minutes

- Recap of key takeaways • 2 minutes

2 readings • Total 20 minutes

- Welcome to the course • 10 minutes

- Additional resources • 10 minutes

5 quizzes • Total 150 minutes

- Understanding functional areas and challenges • 30 minutes

- Effective communication and information sharing • 30 minutes

- Managing conflict and problem solving • 30 minutes

- Leveraging diverse perspectives • 30 minutes

- Cultivating effective teamwork • 30 minutes

1 assignment • Total 180 minutes

- Final Assessment • 180 minutes

Our purpose at Starweaver is to empower individuals and organizations with practical knowledge and skills for a rapidly transforming world. By collaborating with an extensive, global network of proven expert educators, we deliver engaging, information-rich learning experiences that work to revolutionize lives and careers. Committed to our belief that people are the most valuable asset, we focus on building capabilities to navigate ever evolving challenges in technology, business, and design.

Recommended if you're interested in Business Essentials

Alfaisal University | KLD

الاعتراف بالإيراد | Revenue Recognition

تقييم واستحواذ الشركات | Valuing and Acquiring a Business

نماذج الاستراتيجيات والمؤسسات

Google Cloud

Introduction to Image Generation - 简体中文

Why people choose coursera for their career.

New to Business Essentials? Start here.

Open new doors with Coursera Plus

Unlimited access to 7,000+ world-class courses, hands-on projects, and job-ready certificate programs - all included in your subscription

Advance your career with an online degree

Earn a degree from world-class universities - 100% online

Join over 3,400 global companies that choose Coursera for Business

Upskill your employees to excel in the digital economy

Frequently asked questions

When will i have access to the lectures and assignments.

Access to lectures and assignments depends on your type of enrollment. If you take a course in audit mode, you will be able to see most course materials for free. To access graded assignments and to earn a Certificate, you will need to purchase the Certificate experience, during or after your audit. If you don't see the audit option:

The course may not offer an audit option. You can try a Free Trial instead, or apply for Financial Aid.

The course may offer 'Full Course, No Certificate' instead. This option lets you see all course materials, submit required assessments, and get a final grade. This also means that you will not be able to purchase a Certificate experience.

What will I get if I purchase the Certificate?

When you purchase a Certificate you get access to all course materials, including graded assignments. Upon completing the course, your electronic Certificate will be added to your Accomplishments page - from there, you can print your Certificate or add it to your LinkedIn profile. If you only want to read and view the course content, you can audit the course for free.

What is the refund policy?

You will be eligible for a full refund until two weeks after your payment date, or (for courses that have just launched) until two weeks after the first session of the course begins, whichever is later. You cannot receive a refund once you’ve earned a Course Certificate, even if you complete the course within the two-week refund period. See our full refund policy Opens in a new tab .

Is financial aid available?

Yes. In select learning programs, you can apply for financial aid or a scholarship if you can’t afford the enrollment fee. If fin aid or scholarship is available for your learning program selection, you’ll find a link to apply on the description page.

More questions

The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare

- Contact the CEBC

- Sign up for The CEBC Connection

- Topic Areas

- Rating Scales

- Implementation-Specific Tools & Resources

- Implementation Guide

- Implementation Examples

Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS)

About this program.

Target Population: Children and adolescents (ages 3-21) with a variety of behavioral challenges, including both externalizing (e.g., aggression, defiance, tantrums) and internalizing (e.g., implosions, shutdowns, withdrawal) who may carry a variety of related psychiatric diagnoses, and their parents/caregivers, unless not age appropriate (e.g. young adult or transition age youth)

For children/adolescents ages: 3 – 21

For parents/caregivers of children ages: 3 – 21

Program Overview

Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) is an approach to understanding and helping children with behavioral challenges who may carry a variety of psychiatric diagnoses, including oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, mood disorders, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, etc. CPS uses a structured problem solving process to help adults pursue their expectations while reducing challenging behavior and building helping relationships and thinking skills. Specifically, the CPS approach focuses on teaching the neurocognitive skills that challenging kids lack related to problem solving, flexibility, and frustration tolerance. Unlike traditional models of discipline, this approach avoids the use of power, control, and motivational procedures and instead focuses on teaching at-risk kids the skills they need to succeed. CPS provides a common philosophy, language and process with clear guideposts that can be used across settings. In addition, CPS operationalizes principles of trauma-informed care.

Program Goals

The goals of Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) are:

- Reduction in externalizing and internalizing behaviors

- Reduction in use of restrictive interventions (restraint, seclusion)

- Reduction in caregiver/teacher stress

- Increase in neurocognitive skills in youth and caregivers

- Increase in family involvement

- Increase in parent-child relationships

- Increase in program cost savings

Logic Model

The program representative did not provide information about a Logic Model for Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) .

Essential Components

The essential components of Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) include:

- Three different types of intervention delivery to parents and/or children/adolescents depending on the personal situation:

- Family therapy sessions (conducted both with and without the youth) which typically take place weekly for approximately 10-12 weeks

- 4- and 8-week parent training curricula that teach the basics of the model to parents in a group format (maximum group size = 12 participants)

- Direct delivery to youth in treatment or educational settings in planned sessions or in a milieu

- In the family sessions or parent training sessions, parents receive:

- An overarching philosophy to guide the practice of the approach ("kids do well if they can")

- A specific assessment process and measures to identify challenging behaviors, predictable precipitants, and specific thinking skill deficits. Lagging thinking skills are identified in five primary domains:

- Language and Communication Skills

- Attention and Working Memory Skills

- Emotion and Self-Regulation Skills

- Cognitive Flexibility Skills

- Social Thinking Skills

- A specific planning process that helps adults prioritize behavioral goals and decide how to respond to predictable difficulties using 3 simple options based upon the goals they are trying to pursue:

- Plan A – Imposition of adult will

- Plan B – Solve the problem collaboratively

- Plan C – Drop the expectation (for now, at least)

- A specific problem solving process (operationalizing "Plan B") with three core ingredients that is used to collaborate with the youth to solve problems durably, pursue adult expectations, reduce challenging behaviors, teach skills, and create or restore a helping relationship.

- When directly working with the youth in treatment or education settings, providers engage youth with:

Program Delivery

Child/adolescent services.

Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) directly provides services to children/adolescents and addresses the following:

- A range of internalizing and externalizing behaviors, including (but not limited to) physical and verbal aggression, destruction of property, self-harm, substance abuse, tantrums, meltdowns, explosions, implosive behaviors (shutting down), crying, pouting, whining, withdrawal, defiance, and oppositionality

Parent/Caregiver Services

Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) directly provides services to parents/caregivers and addresses the following:

- Child with internalizing and/or externalizing behaviors, difficulty effectively problem solving with their child

Services Involve Family/Support Structures:

This program involves the family or other support systems in the individual's treatment: Any caregivers, educators, and other supports are essential to the success of the approach. Caregivers, teachers and other adult supporters are taught to use the approach with the child outside the context of the clinical setting. School and clinical staff typically learn the model via single or multi-day workshops and through follow-up training and coaching.

Recommended Intensity:

Typically family therapy (in which the youth is the identified patient, but the parents are heavily involved in the sessions so that they can get better at using the approach with their child on their own) occurs once per week for approximately 1 hour. The approach can also be delivered in the home with greater frequency/intensity, such as twice a week for 90 minutes. Parent training group sessions occur once a week for 90 minutes over the course of 4 or 8 weeks. The approach can also be delivered by direct care staff in a treatment setting and/or educators in a school system, in which case delivery is not limited to scheduled sessions, but occurs in the context of regular contact in a residence or classroom.

Recommended Duration:

Family therapy: 8-12 weeks; In-home therapy: 8-12 weeks; Parent training groups: 4-8 weeks

Delivery Settings

This program is typically conducted in a(n):

- Adoptive Home

- Birth Family Home

- Foster / Kinship Care

- Outpatient Clinic

- Community-based Agency / Organization / Provider

- Group or Residential Care

- Justice Setting (Juvenile Detention, Jail, Prison, Courtroom, etc.)

- School Setting (Including: Day Care, Day Treatment Programs, etc.)

Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) includes a homework component:

Identifying specific precipitants, prioritizing behavioral goals, and practicing the problem solving process are expected to be completed by the caregiver and youth between sessions.

Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) has materials available in languages other than English :

Chinese, French, Spanish

For information on which materials are available in these languages, please check on the program's website or contact the program representative ( contact information is listed at the bottom of this page).

Resources Needed to Run Program

The typical resources for implementing the program are:

Trained personnel. If being delivered as parent group training, it requires a room big enough to hold the number of families (anywhere from a couple of parents up to 12 participants), as well as A/V equipment or printed materials for delivery of material in training curriculum.

Manuals and Training

Prerequisite/minimum provider qualifications.

Service providers and supervisors must be certified in CPS . There is no minimum educational level required before certification process can begin.

Manual Information

There is a manual that describes how to deliver this program.

Program Manual(s)

Treatment Manual: Greene, R. W., & Ablon, J. S. (2005). Treating explosive kids: The Collaborative Problem Solving approach . Guilford Press.

Training Information

There is training available for this program.

Training Contact:

- Think: Kids at Massachusetts General Hospital [email protected] phone: (617) 643-6300

Training Type/Location:

Training can be obtained onsite, at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, at trainings hosted in other locations, online (introductory training only), or via video/phone training and coaching.

Number of days/hours:

Ranges from a 2-hour exposure training to more intensive (2.5 day) advanced sessions as well as hourly coaching:

- Exposure/Introductory training: These in-person and online trainings typically last from 2–6 hours and provide a general overview exposure of the model including the overarching philosophy, the assessment , planning and intervention process. Training can accommodate an unlimited number of participants.

- Two-and-a-half day intensive trainings that provide participants in-depth exposure to all aspects of the model using didactic training, video demonstration, role play and breakout group practice. Tier 1 training is limited to 150 participants. Tier 2 training is limited to 75 participants.

- Coaching sessions for up to 12 participants that provide ongoing support and troubleshooting in the model

Additional Resources:

There currently are additional qualified resources for training:

There are many certified trainers throughout North America who teach the model as well as well as systems that use the approach. The list is available at https://thinkkids.org/our-communities

Implementation Information

Pre-implementation materials.

There are pre-implementation materials to measure organizational or provider readiness for Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) as listed below:

A CPS Organizational Readiness Assessment measure has been developed that is available for systems interested in implementing the model. It can be obtained by contacting the Director of Research and Evaluation, Dr. Alisha Pollastri, at [email protected].

Formal Support for Implementation

There is formal support available for implementation of Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) as listed below:

Think:Kids provides implementation support in the form of ongoing coaching and fidelity and outcome monitoring. There is a Director of Implementation who oversees these activities.

Fidelity Measures

There are fidelity measures for Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) as listed below:

Self Study of CPS Sustainability, Updated 06/2019 : A guide for systems to assess the degree to which they are have put the structures in place to implement CPS with fidelity . Can be obtained by contacting the Director of Research and Evaluation, Dr. Alisha Pollastri, at [email protected].

CPS Manualized Expert-Rated Integrity Coding System (CPS-MEtRICS) and Treatment Integrity Rating Form-Short (CPS-TIRFS) : Fidelity tools to help measure the degree to which CPS is being practiced with fidelity in a specific encounter. Can be obtained by contacting the Director of Research and Evaluation, Dr. Alisha Pollastri, at [email protected].

Implementation Guides or Manuals

There are implementation guides or manuals for Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) as listed below:

Clinician Session Guide : Guides the clinician in all aspects of the treatment, from initial assessment to ongoing work. Can be obtained by contacting the Director of Research and Evaluation, Dr. Alisha Pollastri, at [email protected].

CPS Coaching Guide : A guide specifically geared towards trainer individuals who are helping caregivers to implement the model over time. Available to certified trainers.

Research on How to Implement the Program

Research has been conducted on how to implement Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) as listed below:

Ercole-Fricke, E., Fritz, P., Hill, L. E., & Snelders, J. (2016). Effects of a Collaborative Problem Solving approach on an inpatient adolescent psychiatric unit. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 29 (3), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12149

Pollastri, A. R., Boldt, S., Lieberman, R., & Ablon, J. S. (2016). Minimizing seclusion and restraint in youth residential and day treatment through site-wide implementation of Collaborative Problem Solving. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33 (3-4), 186–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2016.1188340

Pollastri, A. R., Ablon, J. S., & Hone, M. J. (Eds.). (2019). Collaborative Problem Solving: An evidence-based approach to implementation and practice. Springer.

Pollastri, A. R., Wang, L., Youn, S. J., Ablon, J. S., & Marques, L. (2020). The value of implementation frameworks: Using the active implementation frameworks to guide system-wide implementation of Collaborative Problem Solving. Journal of Community Psychology , 48 (4), 1114–1131. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22325

Relevant Published, Peer-Reviewed Research

Child Welfare Outcome: Child/Family Well-Being

Greene, R. W., Ablon J. S., Goring, J. C., Raezer-Blakely, L., Markey, J., Monuteaux, M. C., Henin, A, Edwards, G., & Rabbitt, S. (2004). Effectiveness of Collaborative Problem Solving in affectively dysregulated children with oppositional defiant disorder: Initial findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72 (6), 1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1157

Type of Study: Randomized controlled trial Number of Participants: 47

Population:

- Age — 4–12 years

- Race/Ethnicity — Not specified

- Gender — 32 Male and 15 Female

- Status — Participants were parents and their children with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD).

Location/Institution: Massachusetts

Summary: (To include basic study design, measures, results, and notable limitations) The purpose of the study was to examine the efficacy of Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) in affectively dysregulated children with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Participants were randomized to either the parent training version of CPS or parent training (PT). Measures utilized include the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic version (K-SADS–E), the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Revised, the Parent–Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI), the Parenting Stress Index (PSI), the Oppositional Defiant Disorder Rating Scale (ODDRS), and the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement (CGI-I) . Results indicate that CPS produced significant improvements across multiple domains of functioning at posttreatment and at 4-month follow-up. Limitations include small sample size and length of follow-up.

Length of controlled postintervention follow-up: 4 months.

Pollastri, A. R., Boldt, S., Lieberman, R., & Ablon, J. S. (2016). Pollastri, A. R., Boldt, S., Lieberman, R., & Ablon, J. S. (2016). Minimizing seclusion and restraint in youth residential and day treatment through site-wide implementation of Collaborative Problem Solving. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 33 (3–4), 186–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2016.1188340

Type of Study: Pretest–posttest study with a nonequivalent control group (Quasi-experimental) Number of Participants: Not specified

- Age — Not specified

- Gender — Not specified

- Status — Participants were in residential and day treatment and included youth in foster care and child welfare.

Location/Institution: Oregon

Summary: (To include basic study design, measures, results, and notable limitations) The purpose of the study was to describe the results of one agency’s experience implementing the Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) approach organization-wide and its effect on reducing seclusion and restraint (S/R) rates. Participants were grouped into the CPS intervention at a residential or day treatment facility. Measures utilized include the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS) and the Child and Adolescent Needs Assessment (CANS) . Results indicate that during the time studied, frequency of restrictive events in the residential facility decreased from an average of 25.5 per week to 2.5 per week, and restrictive events in the day treatment facility decreased from an average of 2.8 per week to 7 per year. Limitations include lack of randomization of participants, and lack of follow-up.

Length of controlled postintervention follow-up: None.

Additional References

Greene, R. W., & Ablon, J. S. (2005). Treating explosive kids: The Collaborative Problem Solving approach . Guilford Press.

Greene, R. W., Ablon, J. S., Goring, J. C., Fazio, V., & Morse, L. R. (2003). Treatment of oppositional defiant disorder in children and adolescents. In P. Barrett & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), Handbook of Interventions that work with children and adolescents: Prevention and treatment. John Wiley & Sons.

Pollastri, A. R., Epstein, L. D., Heath, G. H., & Ablon, J. S. (2013). The Collaborative Problem Solving approach: Outcomes across settings. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 21 (4), 188–199. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0b013e3182961017

Contact Information

Date Research Evidence Last Reviewed by CEBC: July 2023

Date Program Content Last Reviewed by Program Staff: March 2020

Date Program Originally Loaded onto CEBC: May 2017

Glossary | Sitemap | Limitations & Disclosures

The CEBC is funded by the California Department of Social Services’ (CDSS’) Office of Child Abuse Prevention and is one of their targeted efforts to improve the lives of children and families served within child welfare system.

© copyright 2006-2024 The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare www.cebc4cw.org

Collaborative Problem Solving: What It Is and How to Do It

What is collaborative problem solving, how to solve problems as a team, celebrating success as a team.

Problems arise. That's a well-known fact of life and business. When they do, it may seem more straightforward to take individual ownership of the problem and immediately run with trying to solve it. However, the most effective problem-solving solutions often come through collaborative problem solving.

As defined by Webster's Dictionary , the word collaborate is to work jointly with others or together, especially in an intellectual endeavor. Therefore, collaborative problem solving (CPS) is essentially solving problems by working together as a team. While problems can and are solved individually, CPS often brings about the best resolution to a problem while also developing a team atmosphere and encouraging creative thinking.

Because collaborative problem solving involves multiple people and ideas, there are some techniques that can help you stay on track, engage efficiently, and communicate effectively during collaboration.

- Set Expectations. From the very beginning, expectations for openness and respect must be established for CPS to be effective. Everyone participating should feel that their ideas will be heard and valued.

- Provide Variety. Another way of providing variety can be by eliciting individuals outside the organization but affected by the problem. This may mean involving various levels of leadership from the ground floor to the top of the organization. It may be that you involve someone from bookkeeping in a marketing problem-solving session. A perspective from someone not involved in the day-to-day of the problem can often provide valuable insight.

- Communicate Clearly. If the problem is not well-defined, the solution can't be. By clearly defining the problem, the framework for collaborative problem solving is narrowed and more effective.

- Expand the Possibilities. Think beyond what is offered. Take a discarded idea and expand upon it. Turn it upside down and inside out. What is good about it? What needs improvement? Sometimes the best ideas are those that have been discarded rather than reworked.

- Encourage Creativity. Out-of-the-box thinking is one of the great benefits of collaborative problem-solving. This may mean that solutions are proposed that have no way of working, but a small nugget makes its way from that creative thought to evolution into the perfect solution.

- Provide Positive Feedback. There are many reasons participants may hold back in a collaborative problem-solving meeting. Fear of performance evaluation, lack of confidence, lack of clarity, and hierarchy concerns are just a few of the reasons people may not initially participate in a meeting. Positive public feedback early on in the meeting will eliminate some of these concerns and create more participation and more possible solutions.

- Consider Solutions. Once several possible ideas have been identified, discuss the advantages and drawbacks of each one until a consensus is made.

- Assign Tasks. A problem identified and a solution selected is not a problem solved. Once a solution is determined, assign tasks to work towards a resolution. A team that has been invested in the creation of the solution will be invested in its resolution. The best time to act is now.

- Evaluate the Solution. Reconnect as a team once the solution is implemented and the problem is solved. What went well? What didn't? Why? Collaboration doesn't necessarily end when the problem is solved. The solution to the problem is often the next step towards a new collaboration.

The burden that is lifted when a problem is solved is enough victory for some. However, a team that plays together should celebrate together. It's not only collaboration that brings unity to a team. It's also the combined celebration of a unified victory—the moment you look around and realize the collectiveness of your success.

We can help

Check out MindManager to learn more about how you can ignite teamwork and innovation by providing a clearer perspective on the big picture with a suite of sharing options and collaborative tools.

Need to Download MindManager?

Try the full version of mindmanager free for 30 days.

- CPS With Kids (and Adults)

- Trauma-Informed FBA

- HeartMath Services

- Our Clients

Our Mission: Bowman Consulting Group is dedicated to partnering with organizations, agencies, communities and systems to provide collaborative problem solving training, trauma-informed care, coaching, consultation and support to staff serving children, youth and adults who struggle as a result of trauma, neurodiversity, developmental differences, or mental health challenges.

We have had the privilege of working with Rick and Doris for over a year, both as a school and now a school district. To say this work has been transformative is an understatement. It has changed the way we work with students, improved our school culture and provided steps to build durable, life-long skills in our students. Collaborative Problem Solving has become necessary training for EVERY educator in our building. We have worked exclusively with Rick and Doris as their expertise, experience and presentation skills are second to none. CPS has helped us find our vision for how we want to work with our children, Rick and Doris have provided the stepping stones to get there.

Our Vision: We envision a future in which every child, youth & adult, regardless of trauma history, neuro-developmental differences or mental health diagnoses will receive the neurobiologically and developmentally appropriate education, treatment & services that will enable them to grow, develop and reach their potential as an individual and member of their community, AND that every Adult serving them will receive the neurobiologically grounded training & support needed to enable them to generate and sustain their own optimal wellness & resilience.

Learn more about who we are and what our team brings to the table. Read what others have said about our trainings and our work with them.

Find connection, support and next-level resilience & self-care/wellness training for YOU or YOUR STAFF in our Connected Community!

We offer consultation, coaching, observation, and team-building. Find out how we can partner with you on your important journey of serving children, youth or adults.

Rick and Doris are experienced practitioners that can speak to the daily challenges student serving professionals face. Their trainings provide a sense of validation and help us make sense of what we are experiencing with our students and in ourselves. No we aren’t crazy and this is why! Their solid understanding of the neurobiology of trauma puts them on the leading edge of how best to work with students, families and coworkers most impacted by trauma.

HBCC has been hosting trainings with Rick and Doris Bowman since 2016 and we receive exceptional feedback! Parents, teachers and service providers report back immediate results in their homes, classrooms and practices due to what they learned at a Bowman Consulting training. HBCC is continually asked to schedule more of their trainings from participants in our community. As the founder of HBCC, it is always pleasurable to work with the Bowmans’ high standards and willingness to go above and beyond, delivering powerful, effective and expert training and consultation!

Why Bowman Consulting Group?

Conventional wisdom isn’t working!! If it were going to work, it would have done so a lonnng time ago!

Kids in our schools or treatment centers, people in our communities, employees in our organizations… ALL matter, ALL need support, and ALL WANT TO DO WELL!

You understand, as do we, that commitment to the long-term is crucial! You also understand that system-wide change is hard! We aren’t showing up with a magic wand… We’re going to deliver solid, research-based training, followed by coaching, consultation & support that will GUARANTEE RESULTS!!

Presentation was great – practicality, humor and organization!

Thank you so much! It was 100% worth my time!

CONTACT US NOW FOR TRAUMA-INFORMED CARE, RESILIENCE & SELF-REGULATION, OR COLLABORATIVE PROBLEM SOLVING TRAINING

Founding Members of the Resilience Coalition

Bowman Consulting Group is proud to have been selected as one of the founding members of the Resilience Coalition led by the Resilient Educator .

Bowman Consulting Group, along with 11 other members of the coalition, are serving in an advisory and partnership capacity with Resilient Educator, as well as with fellow coalition partners which include:

- The Urban Assembly

- Columbia College, South Carolina

- The Zamperini Foundation

- Attachment and Trauma Network

- Case Western University

- Jim Sporleder, former Principal, Lincoln HS

- Thriving Schools, Kaiser Permanente

- Jody Johnson, Associate Professor, ECE

- Creighton University

- Alliant University International

- Northcentral University

TRAININGS OF ALL SHAPES AND SIZES FOR CAREGIVERS OF ALL STRIPES

So there’s definitely something for you, your school, or your treatment facility.

- CONFERENCES

- SCHOOLS & FACILITIES

- CLINICIANS & EDUCATORS

WORKSHOPS & TRAINING

Whether you’re a clinician, educator, or parent, if you’re seeking additional exposure to and expertise in the Collaborative & Proactive Solutions model, there’s a training option to meet your needs, including virtual trainings, annual conferences, trainings specific to schools and facilities, trainings for individual clinicians and educators, and on-demand programming. All of these options are described in detail below. (And there are additional trainings are listed on a different website… click here .) If you’re having trouble deciding which training is best for you or your school or treatment facility, contact us…we’d be happy to help you out.

ANNUAL CONFERENCES

What a day! Our 2024 Annual Summit on Collaborative & Proactive Solutions was held on April 12th, and over 4000 people were registered. This year’s theme was Voices of the Neurodivergent Community , and we had some amazing keynote speakers, including Alex Kimmel, Kristy Forbes, Meghan Ashburn, Jules Edward, and Jenny Hunt , along with fantastic breakout groups for parents, educators, and mental health clinicians at various points in their journey with the CPS model. We’ll be streaming highlights here as soon as we get the film edited! If you didn’t register but would still like to watch all the presentations, contact us .

Hope – Solutions – Action was the tagline for our 2023 Children’s Mental Health Advocacy Conference , which was held on October 27th, 2023 . Over 3000 people registered for the conference. The hope is in the legislation and policy changes that tell us that punitive, exclusionary disciplinary practices won’t be around forever. The solutions can be found in innovative, collaborative, proactive interventions like Collaborative & Proactive Solutions that are proven to dramatically reduce or eliminate discipline referrals, suspensions, restraints, and seclusions. And the action …there are lots of things you to can do to move things in the right direction, starting with signing up to be a Lives in the Balance Advocator. As always, the conference was free. If you missed it, couldn’t stay for all of it, or want to see it again, you can watch the conference in its entirety he re . And we’ll be posting the dates of our 2024 Conference here soon.

VIRTUAL TRAININGS

Our next live, virtual, 2-day combined introductory and advanced training on Collaborative & Proactive Solutions with Dr. Greene is on May 30 & 31, 2024 . If you can’t join in live, your registration gives you access to the recording. Registration is now open!

If you don’t want to wait — or if those dates don’t work for you — our last 2-day training is available with a pay-per-view option.

CONSULTATION AND TRAINING FOR SCHOOLS AND THERAPEUTIC FACILITIES

HALF AND FULL-DAY WORKSHOPS If you or your staff are relatively new to the CPS model, Lives in the Balance offers half- and full-day workshops, which provide a general overview of the CPS model (key themes, use of assessment instrumentation, and solving problems collaboratively), and can be provided either on-site or by webinar.

TWO-DAY ON-SITE INTRODUCTORY TRAININGS For a more intensive introductory experience, we provide a two-day introductory training, either on-site or by webinar . The addition of the second day allows for presenting video examples of the CPS model, along with greater opportunity for practice, processing, discussion, and questions.

PROFICIENCY TRAININGS These trainings have a new format for 2024. The goal, as always, is to help a cadre of staff become proficient in using the assessment tool (the ASUP) and problem-solving process (Plan B) and then model these facets for other staff, thereby facilitating the spread of CPS through a school or facility. The training now begins with a brief school climate questionnaire and a free introductory video (to make sure school leadership understands what’s involved in the training before committing). Then 3-4 members of your implementation team – the key folks that are spearheading the change – will view two video modules and complete readiness checks to set the stage for what’s to come. Then, a “core group” of 8-10 staff — including the implementation team members — will view an overview video describing the CPS model. (The core group is typically comprised of a cross-section of administrators and classroom teachers/line staff.) Then the core group works with a Lives in the Balance trainer for 8-10 teleconference sessions to become proficient in using the ASUP and Plan B, by submitting work samples and receiving feedback. Key prerequisites for participants are (a) an open mind, (b) a willingness to practice the model between sessions, and (c) the courage to receive feedback in a group format.

CONSULTATION AND TRAINING ON REDUCING/ELIMINATING RESTRAINT AND SECLUSION No, we’re not going to teach staff how to recognize that a student is becoming escalated (staff already know when a student is becoming escalated…and, by the time a student is becoming escalated, you’re in crisis management mode). And we’re not going to teach staff how to safely restrain and seclude students (also crisis management). We’re going to help staff become almost totally proactive in identifying the expectations students are having difficulty meeting (known in the CPS model as unsolved problems), and we’re going to help staff learn how to solve those problems collaboratively and proactively. Along the way, we’re going to help with the logistical factors that so often set the stage for restraint and seclusion (e.g. lack of awareness of student medication changes, the belief that restraint and seclusion are necessary and promote safety, placing expectations on students that it’s quite clear they can’t meet). Then we’re going to watch your rates of restraints and seclusions plummet.

If you want to discuss any of these options or the needs of your school or facility with a real human being, CONTACT Lives in the Balance and we’ll make sure you get what you need. Trainings are available in English, Swedish, Danish, German, Finnish, Norwegian, and French.

TRAININGS FOR INDIVIDUAL EDUCATORS AND CLINICIANS

2-DAY TRAININGS Our 2-day trainings (described above) provide participants with additional exposure to and instruction in key facets of the CPS model, video examples of its application, and model updates. These trainings are offered in various locations throughout the world, and also via webinar . The advanced trainings are for those who have had some prior exposure to the model, often through attendance at one of Dr. Greene’s one-day introductory trainings (see below), as well as for those who have already attended a prior 2-day training and have been actively applying the model in clinical work or in a treatment or education setting. All 2-day trainings are taught by Dr. Greene. Many are posted on a different website .

CERTIFICATION TRAININGS Certification trainings are designed for individual clinicians, educators, and other providers interested in developing proficiency in the application of the CPS model and training others. The training provides supervised practice and feedback in 24 weekly, 60-90 minute Zoom supervision sessions. The first ten weeks focuses on use of the Assessment of Skills and Unsolved Problems [ASUP] and Plan B. Participants who demonstrate proficiency in these two components are eligible to participate in the subsequent 14-weeks of training, in which skills related to explaining the model, demonstrating it, and coaching it are the focal point. Each supervision group is limited to six participants, and we typically run multiple groups simultaneously. Submission of weekly work samples are required, so access to a sufficient number of kids and families/teachers is necessary. Upon successful completion of this training, participants are eligible to provide demonstration, coaching, and feedback to staff in their schools and provide the CPS model in their outpatient setting or therapeutic facility. Certified providers are also eligible to begin receiving training in speaking on the CPS model and providing consultation, supervision, and coaching to train others outside of their setting. These trainings take place all year on rolling admission. In addition to English, the certification training is offered in Swedish, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and French. You can submit your application here. In general, we encourage some prior experience in using the model before applying for this training. If you still have questions, please read our FAQs and/or contact us at [email protected] .

SKILL ENHANCEMENT TRAININGS These trainings are an alternative to the lengthier, more intensive 24-week certification trainings (see below). Over the course of five 60-minute group Zoom sessions, participants receive coaching and feedback from certified providers in CPS to increase their skills in the application of the CPS model. The first 1-2 sessions are focused on the use of the Assessment of Skills and Unsolved Problems (ASUP). The remaining sessions are focused on Plan B, and involve having participants audiotape their use of Plan B with actual kids and their caregivers so as to receive highly individualized coaching and feedback. Registration is limited to six participants per training. Trainings are available in English, Swedish, Danish, and French. New sessions will be added soon! If you have questions, email us at [email protected] .

TRAINING FOR PARENTS

We’re in the midst of revising and refreshing our training options for parents. Please visit this section again soon to see what we’ve cooked up!

ON-DEMAND PROGRAMMING

2-Day Training on Collaborative & Proactive Solutions with Dr. Ross Greene

Infusing Collaborative & Proactive Solutions Into PBIS with assistant principal Kelly Sarah and school psychologist Rachel Polacek (FREE!)

Addressing Disproportionality in School Discipline with Collaborative & Proactive Solutions with Dr. Stacy Haynes (FREE!)

School Implementation of CPS: Building leadership density & a positive culture with Principal Ryan Gleason (FREE!)

CPS & the Neurodivergent Student with Dr. Stacy Haynes (FREE!)

If you’re interested in learning more about any of the above options, just use the Contact form on this website.

15 Main Street, Suite 200, Freeport, Maine 04032

Lives In the Balance All Rights Reserved. Privacy Policy Disclaimer Gift Acceptance Policy

Sign up for our Newsletter CPS Methodology Podcasts about the CPS Model Connect with our Community Research

Why We’re Here Meet the Team Our Board of Directors Higher Ed Advisory Board

Get in Touch Make a Donation

- PARENTS & FAMILIES

- EDUCATORS & SCHOOLS

- PEDIATRICIANS & FAMILY PHYSICIANS

- CPS WITH YOUNG KIDS

- WORKSHOPS & TRAININGS

- CPS PAPERWORK

- WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

- PUBLIC AWARENESS

- SCHOLARSHIPS

- BECOME AN ADVOCATOR

- RESOURCES FOR ADVOCATORS

- TAKE ACTION

What Is Collaborative Problem Solving?

Imagine collaborative problem solving as a symphony where each instrument plays an important part in creating harmony.

As you explore the intricacies of this method, you'll uncover the intricate dance of minds working together to unravel complex issues.

The beauty lies in the synergy of diverse perspectives, the orchestration of communication, and the finesse of teamwork.

But how does this symphony truly come together, and what are the secrets behind its success?

Stay tuned to unravel the mysteries and open the potential of collaborative problem solving.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Collaborative problem solving enhances efficiency and innovation through diverse perspectives.

- Core principles guide the process for effective outcomes and improved team dynamics.

- Effective communication strategies, like active listening, foster a collaborative problem-solving environment.

- Conflict resolution skills and creativity are essential for successful collaborative problem solving.

Benefits of Collaborative Problem Solving

Collaborative problem solving enhances efficiency and fosters innovative solutions through collective expertise and diverse perspectives. Team synergy plays an important role in this process, as individuals bring forth unique insights that contribute to a thorough understanding of the issue at hand. By leveraging the combined problem-solving strategies of team members, collaborative innovation flourishes, leading to more effective outcomes.

One of the key advantages of collaborative problem solving is the ability to tap into a diverse range of perspectives when making decisions. This diversity allows for a more detailed exploration of potential solutions, as individuals with varying backgrounds and experiences offer fresh insights that one person alone may not have considered. Additionally, the collaborative nature of problem solving fosters a sense of ownership among team members, increasing their commitment to implementing the chosen solution effectively.

Key Elements of CPS Process

When engaging in collaborative problem solving, it's important to understand the core CPS principles that guide the process.

Effective communication strategies play an essential role in ensuring that all team members are on the same page and can contribute their insights.

Collaborative decision-making is key to reaching solutions that consider diverse perspectives and foster a sense of ownership among participants.

Core CPS Principles

Effective problem solving in collaborative settings depends on adherence to the core principles that underpin the CPS process. The core principles encompass a set of guidelines that form the foundation for successful problem-solving techniques within a collaborative framework.

These principles emphasize the importance of active listening, open-mindedness, and mutual respect among team members. By embracing these core principles, individuals can enhance their ability to generate innovative solutions, leverage diverse perspectives, and foster a supportive team environment.

Additionally, these principles highlight the significance of maintaining a solution-focused mindset, promoting constructive feedback, and valuing contributions from all team members. Overall, integrating these core principles into collaborative problem-solving endeavors can lead to more effective outcomes and improved team dynamics.

Effective Communication Strategies

Adherence to the core principles of Collaborative Problem Solving lays the groundwork for implementing Effective Communication Strategies essential to the Key Elements of the CPS Process. Active listening, a fundamental component of effective communication, involves fully concentrating, understanding, responding, and remembering what's being said.

By actively listening, you show respect, build trust, and foster a collaborative environment conducive to problem-solving. Additionally, importance training plays a critical role in communication within the CPS framework. Importance training helps individuals express their needs, thoughts, and feelings in a direct and honest manner while respecting the perspectives of others.

This skill enables effective communication by promoting clarity, openness, and constructive dialogue in addressing conflicts and finding solutions collaboratively.

Collaborative Decision-Making

To achieve successful collaborative decision-making within the CPS process, understanding and integrating the key elements is essential. Group decision making plays an important role in the problem-solving process, ensuring that diverse perspectives are considered.

Collective problem resolution is achieved through a team approach, where individuals contribute their unique insights and expertise to reach a consensus. Effective collaborative decision-making requires active participation from all team members, open communication channels, and a shared commitment to the common goal.

Importance of Team Dynamics

Team dynamics play an important role in determining the success of collaborative problem-solving efforts. Team cohesion, which refers to the ability of a group to work together effectively and harmoniously, is vital in achieving shared goals. When group dynamics are positive, team members are more likely to trust each other, communicate openly, and support each other. Collaboration strategies that focus on enhancing team cohesion can lead to improved problem-solving outcomes. For instance, implementing team-building activities, establishing clear roles and responsibilities, and fostering a culture of respect and inclusivity are all ways to strengthen team dynamics.

Effective group dynamics can help teams navigate challenges, adapt to changing circumstances, and capitalize on diverse perspectives. By valuing each member's contributions and leveraging individual strengths, teams can enhance their problem-solving capabilities. When team members feel connected and engaged, they're more motivated to work collaboratively towards finding innovative solutions. Therefore, investing time and effort into nurturing positive team dynamics is essential for achieving successful collaborative problem-solving outcomes.

Role of Communication in CPS

Effective communication plays a crucial role in collaborative problem solving, facilitating the exchange of ideas and information among team members to drive successful outcomes. In the domain of Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS), effective communication strategies are essential for ensuring that the team functions cohesively and efficiently. Here are some key points highlighting the importance of communication in CPS:

- Clear and Transparent Communication : Ensuring that all team members are on the same page regarding goals and progress.

- Active Listening : Encouraging active listening amongst team members to comprehend diverse perspectives and ideas effectively.

- Feedback Mechanisms : Establishing feedback loops to provide constructive criticism and improve solutions iteratively.

- Non-Verbal Communication : Understanding the significance of body language and other non-verbal cues in enhancing communication.

- Conflict Resolution Skills : Developing techniques to address conflicts constructively and maintain a positive team environment.

Strategies for Effective Collaboration

To effectively collaborate, employ clear communication techniques to make sure all team members are on the same page.

Utilize conflict resolution skills to address any disagreements or disputes that may arise during the problem-solving process.

These strategies are crucial for fostering a productive and harmonious collaborative environment.

Clear Communication Techniques

In successful collaborative problem-solving endeavors, employing clear and concise communication techniques is paramount for fostering productive interactions and achieving common goals. To enhance your collaborative communication skills, consider the following strategies:

- Practice active listening to demonstrate your attentiveness and understanding.

- Pay attention to nonverbal cues such as body language and facial expressions for deeper insights.

- Use open-ended questions to encourage discussion and gather diverse perspectives.

- Clarify any uncertainties promptly to avoid misunderstandings or confusion.

- Summarize key points to make certain alignment and reinforce shared understanding.

Conflict Resolution Skills

Developing proficient conflict resolution skills is essential for ensuring smooth and successful collaboration among team members. Conflict resolution involves addressing disagreements or disputes in a constructive manner to reach a mutually agreeable solution.

Effective conflict resolution requires active listening, empathy, and the ability to remain calm under pressure. Utilizing negotiation skills is important in finding compromises and resolving conflicts amicably.

Team members should focus on understanding the root causes of conflicts and work together to find solutions that benefit all parties involved. By fostering an environment that encourages open communication and respectful dialogue, teams can navigate conflicts productively and strengthen their collaborative efforts.

Conflict resolution skills are important for maintaining positive relationships and achieving shared goals within a team.

Enhancing Creativity Through Collaboration

Enhancing creativity through collaborative problem-solving techniques can yield innovative solutions that transcend individual contributions. When individuals come together to solve problems collectively, creativity flourishes, leading to groundbreaking ideas and outcomes. Here are key ways collaboration enhances creativity:

- Innovation Exploration : Collaborating allows for the exploration of innovative ideas that may not have been possible individually.

- Group Brainstorming : Brainstorming as a group fosters a diverse range of ideas and perspectives, fueling creativity.

- Team Synergy : Working together harnesses the collective strengths of team members, boosting creativity and problem-solving abilities.

- Creative Problem Solving : Collaboration enables the application of different problem-solving approaches, resulting in unique solutions.

- Cross-Pollination of Ideas : Sharing and building upon each other's ideas can lead to the creation of novel and inventive solutions.

Leveraging Diverse Perspectives

Collaborative problem-solving thrives on the ability to leverage diverse perspectives, which play a pivotal role in enhancing the innovative potential of a team. By incorporating various viewpoints and approaches, teams can tap into a wealth of creativity and expertise, acting as innovation catalysts and problem-solving synergy engines. Embracing solution diversity leads to collaborative excellence, where different team members bring unique skills and experiences to the table, enriching the problem-solving process.

To illustrate the significance of leveraging diverse perspectives, consider the following table:

Each row exemplifies how diverse perspectives contribute to collaborative problem-solving by fostering creativity, aiding in decision-making, sparking innovation, broadening problem-solving capabilities, and strengthening team dynamics. Fundamentally, embracing diversity is crucial to achieving collaborative excellence in problem-solving endeavors.

Implementing CPS in Various Settings

Implementing Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) in various settings requires a meticulous understanding of the context and specific needs of the team or organization. When applying CPS, consider the following:

- Workplace applications: CPS can enhance teamwork, communication, and innovation in a corporate setting, leading to more effective problem-solving and decision-making processes.

- Community engagement: Utilizing CPS in community projects fosters collaboration, empowers stakeholders, and guarantees sustainable solutions to local challenges.

- Educational settings: Implementing CPS in schools promotes critical thinking, creativity, and teamwork among students, preparing them for future challenges in the workforce.

- Healthcare industry: CPS can improve patient care by encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration, addressing complex medical issues, and enhancing overall healthcare delivery.

- Tailored approaches: Customizing CPS methods to fit the unique demands of each environment maximizes its effectiveness and ensures successful outcomes.

Overcoming Challenges in Group Problem Solving

To effectively navigate group problem-solving challenges, it's imperative to acknowledge and address potential obstacles that may hinder productive collaboration and decision-making. Group dynamics play an essential role in the success of collaborative problem-solving efforts. Understanding how individuals interact within the group, recognizing communication patterns, and being aware of potential conflicts are essential for overcoming challenges.

One common obstacle in group problem solving is the presence of dominant personalities that may overshadow others' contributions. Implementing strategies to guarantee equal participation, such as setting time limits for each member to speak or using anonymous idea generation techniques, can help mitigate this issue. Additionally, differing problem-solving strategies among group members can lead to inefficiencies. Encouraging open dialogue to discuss and combine diverse approaches can enhance the overall problem-solving process.

Measuring Success in Collaborative Teams

To measure success in collaborative teams, it's essential to focus on team performance metrics and assess goal attainment. These metrics provide concrete data to evaluate the effectiveness of teamwork strategies and the overall performance of the team.

Team Performance Metrics

How can you effectively measure the success of collaborative teams through team performance metrics? Team performance metrics play an important role in evaluating the effectiveness of collaborative efforts.

To gauge the performance of your team, consider implementing the following strategies:

- Conduct team satisfaction surveys to gather feedback on team dynamics.

- Utilize performance evaluations to assess individual contributions to the team.

- Encourage peer feedback to understand how team members perceive each other's contributions.

- Measure team cohesion by evaluating how well members work together towards common goals.

- Track key performance indicators relevant to the project to make sure progress aligns with objectives.

Goal Attainment Assessment

Evaluating goal attainment is a key aspect of evaluating the success of collaborative teams, providing concrete evidence of achievement in working towards shared objectives. To assess goal attainment effectively, start by setting clear, specific, and measurable goals that align with the team's overarching objectives.

Utilize problem-solving techniques like brainstorming, root cause analysis, and action planning to address obstacles hindering goal achievement. Regularly monitor progress towards these goals through data tracking, milestone checkpoints, and progress reports.

Engage team members in reflective discussions to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies employed and make necessary adjustments. By focusing on goal setting and employing structured problem-solving techniques, collaborative teams can track their progress accurately and enhance their overall performance.

As you navigate the intricate web of collaborative problem solving, remember that each team member is a unique puzzle piece contributing to the bigger picture.

Just as a symphony orchestra harmonizes individual instruments to create a beautiful melody, your team must work together in perfect synchronization to overcome challenges and achieve success.

Embrace the diversity of perspectives, communicate effectively, and leverage each member's strengths to reveal the true potential of collaborative problem solving.

It's the key to revealing greatness.

The eSoft Editorial Team, a blend of experienced professionals, leaders, and academics, specializes in soft skills, leadership, management, and personal and professional development. Committed to delivering thoroughly researched, high-quality, and reliable content, they abide by strict editorial guidelines ensuring accuracy and currency. Each article crafted is not merely informative but serves as a catalyst for growth, empowering individuals and organizations. As enablers, their trusted insights shape the leaders and organizations of tomorrow.

View all posts

Similar Posts

What Is Entrepreneurial Thinking?

Open your mind to the possibilities of entrepreneurial thinking and uncover how it can revolutionize your approach to life's challenges.

What is Learning Orientation?

Explore the concept of Learning Orientation, its significance, and how it can profoundly impact personal growth and educational success.

What is Personal Branding?

Discover the essence of Personal Branding, its significance, and how to effectively cultivate your unique professional identity online.

Synonyms of Experienced

Dive deeper into the world of synonyms for 'experienced' and discover the perfect word to elevate your expertise – the journey awaits!

Synonyms of Seriously

Feeling the need for a more impactful expression? Explore synonyms of 'seriously' beginning with the letter 'F' and elevate your communication skills.

What Is Emotional Regulation?

Knead the art of emotional regulation to sail smoothly through life's ups and downs – discover the key to mastering your emotions.

ORPARC Training - An Introduction to Collaborative Problem Solving®

Thursday, january 21, 2021 – 6:00pm, 6:00pm - 7:00pm.

Please join Swindells Resource Center and certified trainers Marcus Saraceno and Paul Kammerzelt from Watershed Problem Solving LLC, for an introduction to Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS).

- The Collaborative Problem Solving® approach

- Skills used for solving problems

- Interventions used in the Collaborative Problem Solving® model

- What to do next?

Download Flyer here

Swindells Online Webinar

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 22 April 2024

The design and evaluation of gamified online role-play as a telehealth training strategy in dental education: an explanatory sequential mixed-methods study

- Chayanid Teerawongpairoj 1 ,

- Chanita Tantipoj 1 &

- Kawin Sipiyaruk 2

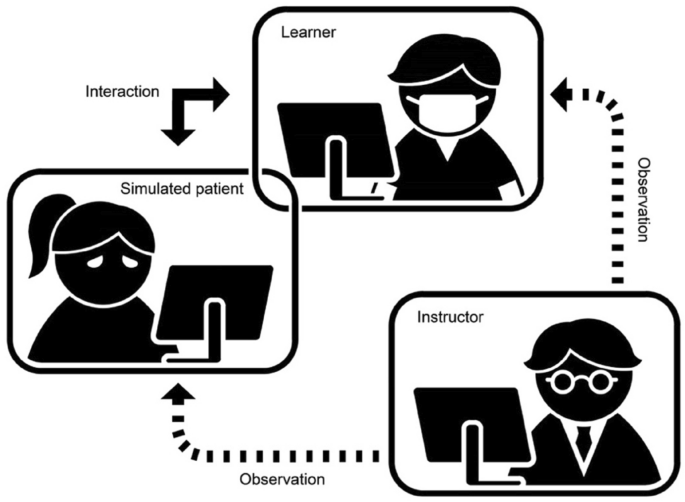

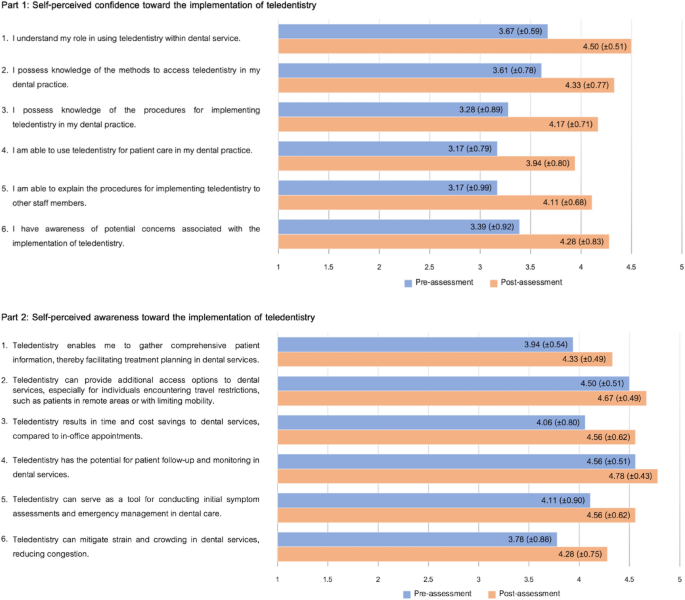

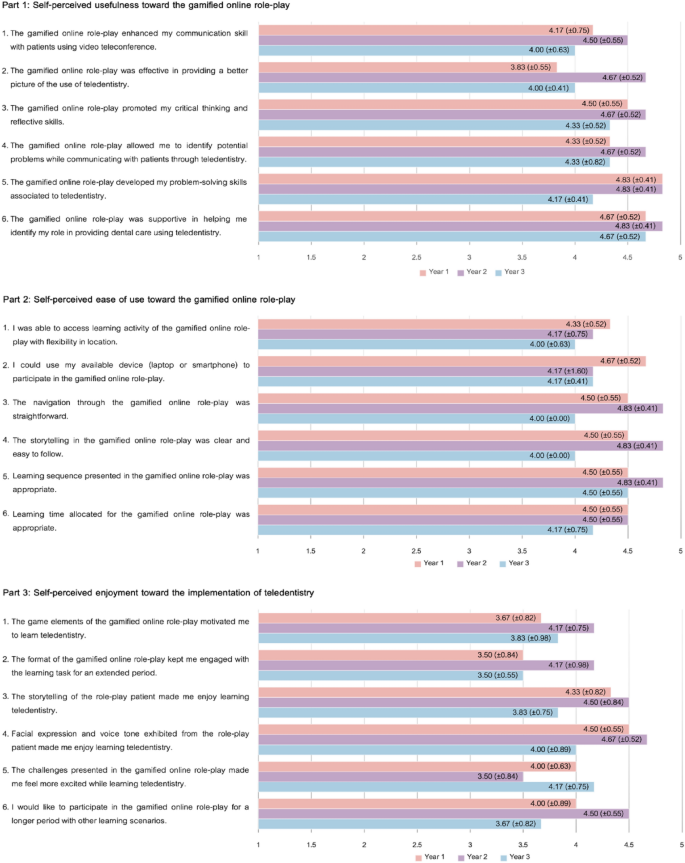

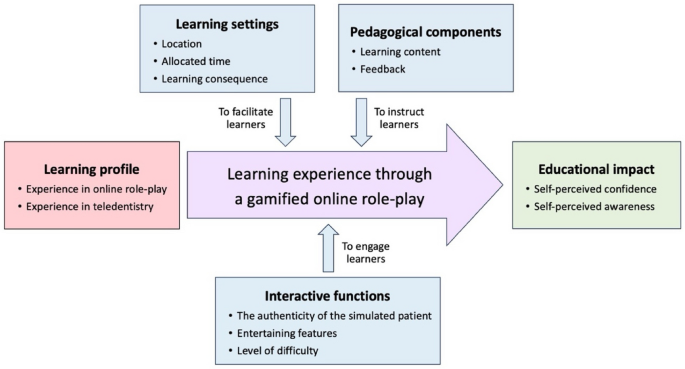

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 9216 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details