The Aruna Shanbaug case which changed euthanasia laws in India

A landmark verdict

The Supreme Court on March 9 ruled that individuals had a right to die with dignity, allowing passive euthanasia with guidelines. The need to change euthanasia laws was triggered by the famous Aruna Shanbaug case. The top court in 2011 had recognised passive euthanasia in Aruna Shanbaug case by which it had permitted withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment from patients not in a position to make an informed decision.

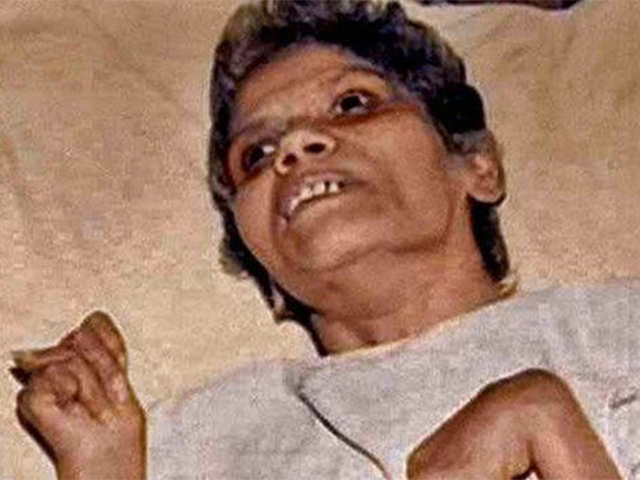

Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug was a nurse in the King Edwards Memorial Hospital in Mumbai. In November 1973, she was assaulted by ward boy, Sohanlal Bhartha Valmiki, of the same hospital while changing her clothes in the hospital basement. Valmiki strangulated Shanbaug with a dog chain around her neck.

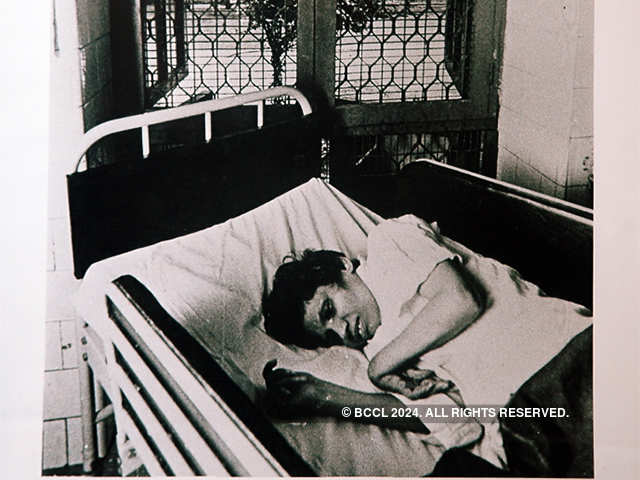

Living in a coma

The attack cut off oxygen supply from her brain leaving her blind, deaf, paralysed and in a vegetative state for the next 42 years. From the day of the assault till the day she died on May 18, 2015, Aruna could only survive on mashed food. She could not move her hands or legs, could not talk or perform the basic functions of a human being.

What happened to Valmiki

In 1974, Valmiki was charged with attempted murder and for robbing Aruna's earrings, but not for rape. The police did not take into account that she was sodomized. A trial court sentenced Valmiki seven years imprisonment. This was reduced to six years because he had already served a year in lock up. Valmiki walked out of jail in 1980 and still claims he did not rape Shanbaug.

Facing opposition

The Supreme Court accepted the petition and constituted a medical board to report back on Aruna's health and medical condition. The medical board, comprising three eminent doctors, reported that the patient was not brain dead and responded to some situations in her own way. They felt that there was no need for euthanasia in the case. The staff at KEM Hospital and the Bombay Municipal Corporation filed their counter-petitions in the case, opposing euthanasia for Aruna. The nurses at KEM Hospital were quite happy to look after the patient and they had been doing that for years before petitioner Pinky Virani emerged on the scene.

Finally at peace

On May 18, 2015, Shanbaug then 66, died of severe pneumonia. She was on ventilator support in KEM's acute care unit.

To post this comment you must

Log In/Connect with:

Fill in your details:

Will be displayed

Will not be displayed

Share this Comment:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ind Psychiatry J

- v.32(1); Jan-Jun 2023

- PMC10236687

Euthanasia – Review and update through the lens of a psychiatrist

Anindya k. gupta.

Department of Psychiatry, Army College of Medical Sciences and Base Hospital, Delhi Cantt, Delhi, India

Deepali Bansal

Euthanasia is not infrequent in the modern practice of medicine. Active euthanasia is legal in seven countries worldwide and passive euthanasia has recently been legalized in India by the Supreme Court. In India, physicians and nurses generally have a favorable attitude towards euthanasia but lack in adequate training to deal with such requests. The role of a psychiatrist is very important in evaluation of request for euthanasia on medical as well as psychiatric grounds. Among patients with end-stage medical illnesses who make a request for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide, many may have underlying untreated depression. In the complex backdrop of long-term chronic medical illnesses, depression can be very difficult to diagnose and treat. Patients with dementia and other neuropsychiatric illnesses have the issue of consent and capacity. Legalizing euthanasia in these patients can heave dire moral implications. There is clear need of adequate training, formulation of guidelines, and supportive pathway for clarity of clinicians regarding euthanasia in India.

Death – it affects all of us including physicians. We all have to die, and we all have an interest in the idea of a good death. So, unlike other bioethical issues, decision-making regarding end-of-life is a particularly challenging discussion for all of us. Post-World War II, science has made ample progress to prolong the life span of an average human by almost 20 years. We have great palliative care measures in the face of terminal illnesses, but when it comes to the ultimate question of choosing death over life, most of the physicians dither.

DEFINITIONS

The word euthanasia, with its origin in Greek words “eu” and “thanatos” means a “good death.” Euthanasia means compassionately allowing, hastening, or causing the death of another. Generally, someone resorts to euthanasia to relieve suffering, maintain dignity or shorten the course of dying when death is inevitable. The concept of euthanasia has multiple dimensions. Active euthanasia means giving something to cause death, while passive euthanasia means withdrawing the supportive measures. Euthanasia can be voluntary if the patient has requested it, non-voluntary if the decision is made without the patient’s consent, or involuntary if the decision is made against the patient’s wishes. Many a times it’s difficult to distinguish between euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide (PAS), because both have a desire to end life and consequently assisted death.[ 1 ] To distinguish between the two one must look at the last act resulting in the death of the patient. If the patient himself performs the last act, for example death resulting from ingesting the pills prescribed by the physician is PAS, while a doctor giving lethal injection would be euthanasia.

INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT AND INDIAN LEGISLATIONS

Internationally, as of March 2021, active euthanasia is legal in seven countries worldwide. Most notable are Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Canada, and Spain. PAS is legalized in Germany, Switzerland and few US states like Oregon, California, Washington, and District of Columbia. Passive euthanasia is allowed in many countries across the world, India being one of them. The debate on euthanasia has been particularly puzzling in Indian context as according to Indian Penal Code (IPC) the attempt to commit suicide as well as abetment to suicide are punishable under section 309 and 306, respectively.[ 2 ] In the legal context, in 1986 M.S. Dubal vs. State of Maharashtra[ 3 ] was the first case in the subsequent long path that led to legalization of passive euthanasia in India. Maruti Sripathi Dubal was a police constable with psychiatric illness who tried to commit suicide and was tried under section 309 of IPC. In the decision, the Bombay High Court held that “right to life” under article 21 of the Indian Constitution includes “right to die” as well. On the other hand, in Chenna Jagadeeswar vs. State of AP,[ 4 ] the Andhra Pradesh High Court ruled that “right to die” is not a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution . In this case accused was a doctor who attempted to commit suicide along with his wife after killing his four children. He was convicted for murder as well as tried under section 309. Another case P. Rathinam’s vs. Union of India,[ 5 ] accused was tried for attempting suicide following unruly circumstances. The Supreme Court of India observed that the “right to live” includes “right not to live” i.e., right to die or to terminate one’s life. In this ruling, Supreme court also held section 309 unconstitutional. The supreme court noted that section 309 may result in punishing the person doubly and is irrational and cruel. In Gian Kaur vs. State of Punjab,[ 6 ] a five-member bench overruled the P. Rathainam’s case and held that right to life under Article 21 does not include Right to die or the right to be killed. The court held that Article 21 is a provision guaranteeing protection of life and personal liberty and by no stretch of imagination can extinction of life be read into it. In this case, Smt Gian Kaur and her husband were convicted by the court for abetting suicide of their daughter in law, by pouring kerosene over her. The most discussed and highlighted case on the debate of euthanasia in India is the Aruna Shanbaug case. Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug was a former nurse from Haldipur, Karnataka. In 1973, while working as a junior nurse at King Edward Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, she was sexually assaulted by a ward boy and was left in a vegetative state since the assault. After 37 years of being in vegetative state, on 24 th January, 2011, the Supreme Court of India responded to the plea for euthanasia filed by activist Pinki Virani. The mercy killing petition was rejected as the hospital staff taking care of Aruna requested against it. However, in its benchmark judgment, the Supreme Court allowed passive euthanasia in India.[ 7 ] The court issued guidelines for passive euthanasia stating that the decision to withdraw treatment, nutrition, or water must be taken by spouse, parents, or a close relative, or in absence of them by a next friend after court’s approval. In 2018, a five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court[ 8 ] declared that the government of India would honor the living wills of patients in vegetative state or the ones suffering from terminal illness, thus, legalizing passive euthanasia in India.

NEED OF THE DISCUSSION

The statistics suggest that PAS is not a rare event. Telling results have been reported globally in various surveys and studies. Surveys done worldwide indicate that almost all physicians involved in taking care of terminal illnesses like AIDS receive requests for PAS or euthanasia at least once in their practice. In response to a hypothetical case vignette, almost half of the practicing physicians indicated they were likely to grant such requests.[ 9 ] There is also evidence to show increasing acceptance of PAS and euthanasia among treating physicians and critical care nurses.[ 10 , 11 ]

In Netherlands, euthanasia was granted legal status in 1984 after a Dutch Supreme Court decision authorized this practice. Few years later, it was reported in that in 1995 euthanasia was responsible for nearly 5% of all deaths in Netherlands as compared to 2.7% in 1990.[ 12 ] Supporters of PAS point to data from Netherlands as evidence that legalization has not led to widespread abuse or overuse of euthanasia or PAS. However, critics suggest that almost 75% increase in deaths involving euthanasia or PAS (from 2.7 to 5%) demonstrates a growing tendency toward their more frequent use and thus a greater number of potentially inappropriate cases of euthanasia. In Southern India, a survey[ 13 ] conducted in a tertiary care hospital in Manipal, showed euthanasia to be an acceptable concept to majority of doctors (69%). Most common reason cited by these doctors was to relieve unbearable pain and suffering. Another study from New Delhi[ 14 ] found that withholding or withdrawal of treatment was acceptable to majority of palliative care physicians and nurses. There are other factors like gender, medical specialty, religious affiliation which have a role in determining one’s attitude towards euthanasia, but nevertheless, these data indicate that requests for assistance in dying are clearly not rare events and physicians not so uncommonly grant such requests despite legal prohibitions.

The role of a psychiatrist carries distinctive importance in the debate as well as the practice of euthanasia. Psychiatrists can help in dealing with issues ranging from presence of depression or suicidal ideations in the terminally ill requesting for euthanasia to the ultimate question of capacity to give consent for the same.

EUTHANASIA ON MEDICAL GROUNDS-ROLE OF A PSYCHIATRIST

Out of all the patients with end stage medical illnesses who make a request for euthanasia or PAS, many may have underlying untreated depression. According to World Health Organization,[ 15 ] suicidal thoughts or acts are among the core symptoms of depression. Almost always there are feelings of hopelessness, helplessness and worthlessness associated with major depression, which may present itself in the form of a patient requesting for help in ending one’s life.[ 16 ] Also, depression can be very difficult to diagnose in the backdrop of long term chronic medical illnesses. Most of these patients are under the care of physicians who may be ill equipped to diagnose and treat depression in such complex scenarios.

Depression is highly prevalent amongst people with chronic terminal medical illnesses like AIDS, cancer etc.[ 17 , 18 ] In these patients with terminal illnesses, depression is highly correlated with hopelessness and desire for hastened death.[ 16 ] This further necessitates the need of a psychiatric consult in patients with medical illnesses who request for PAS or euthanasia. The proposed guidelines offered till date have all suggested that psychiatric evaluation must be included in the critical assessment of a patient’s request for PAS. If PAS or euthanasia (active or passive) is to be legalized in any country, the role of mental health professional becomes even more important. Despite the apparent importance of a mental health professional’s evaluation in assessing the requests for PAS, very little research has been conducted in this area. Only 2% physicians seek mental health consultation for patients who request for euthanasia.[ 19 ] Psychiatric evaluation for these patients can result in better decision making and improvement in quality of end-of-life care for medically ill patients.

EUTHANASIA IN PSYCHIATRIC PATIENTS

There are legitimate clinical and ethical concerns when a patient with mental illness makes a request for euthanasia or PAS. The hopelessness found so commonly in patients of severe depression can lead to a request for euthanasia or PAS. However, people in favor of the legalization put forth the argument, that chronic severe mental illnesses cause intense suffering to the patient for which a solution might not always be available.[ 20 ] A few of the diagnoses in question are dementia, treatment resistant depression etc., Various reasons for requesting for euthanasia or PAS in these patients may include absence of improvement, feeling of loss of dignity and burden on the significant others. Although majority of such requests are denied but there are few isolated incidents wherein euthanasia has been granted to mentally ill patients. In 2017, the incidence of assisted death for psychiatric reasons was found to be 1.1% of all assisted deaths in Belgium and 1.3% in Netherlands.[ 21 ] In such cases psychiatrist is usually the treating doctor and has to be the one granting euthanasia. In a survey only 6% psychiatrists felt confident that they could assess in a single assessment whether mental illness was influencing a person’s decision for requesting PAS.[ 22 ] The euthanasia training modules in various countries like Support a Consultation for Euthanasia in the Netherlands and Life End Information Forum in Belgium, do not have provision for assessment by a psychiatrist. There is evidence that exploration of psychological issues can lead to withdrawal of request for euthanasia.[ 23 ] Few experts have also raised the question whether the exclusion of psychiatric patients from PAS legislation is discriminatory.[ 24 ] Their argument is based on two assumptions – that not all psychiatric patients either have impaired decision-making ability or are effectively curable. But by erasing the distinction between medical and psychiatric disorders, there is fear of implication that PAS should be available to all patients (whether medical or psychiatric) for all reasons or, ultimately no reason.[ 25 ] There is a genuine risk of strengthening the link between PAS/euthanasia and organ donation as psychiatric patients are much more likely to be a source of reusable healthy organs. In Indian context, with the implementation of Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 there is a further convoluted situation with respect to the provision for advance directive and nominated representatives for patients with psychiatric illness. Moral implications can be many for geriatric healthcare delivery, wherein someone else can decide whether an elderly with dementia wants to live or die.

The strongest arguments by the proponents of euthanasia are based on right to self-determination and dignified death. They suggest that not all pain can be relieved or cured in cases of long term mental or physical illness and death can be slow and miserable for these patients. In such scenario, the role of compassionate and skillful training for end-of-life palliative care cannot be denied. The provision of active euthanasia can be considered as an act of killing, which must never be sanctioned to doctors. There is already a growing sense of mistrust regarding doctors in general public and legalization of active euthanasia may further weaken this bond. There is a risk that euthanasia will not only be limited to people who are terminally ill and may become non-voluntary for people who are dependents on others for care. It also carries the risk of becoming a tool for healthcare cost containment by caretakers as well as medical practitioners. As of present day, passive euthanasia has been granted legal status in India by supreme court, but the clear lack of any guidelines or supportive pathway for clarity of clinicians is evident. This is even more difficult for patients with psychiatric illnesses, thus calling for the need of further research and discussions regarding euthanasia in India.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Euthanasia: Global Scenario and Its Status in India

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, India. [email protected].

- 2 Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, India.

- 3 Department of Forensic Medicine, Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal, India.

- 4 Department of Anthropology, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India.

- PMID: 28726026

- DOI: 10.1007/s11948-017-9946-7

The legal and moral validity of euthanasia has been questioned in different situations. In India, the status of euthanasia is no different. It was the Aruna Ramachandra Shanbaug case that got significant public attention and led the Supreme Court of India to initiate detailed deliberations on the long ignored issue of euthanasia. Realising the importance of this issue and considering the ongoing and pending litigation before the different courts in this regard, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India issued a public notice on May 2016 that invited opinions from the citizens and the concerned stakeholders on the proposed draft bill entitled The Medical Treatment of Terminally Ill Patients (Protection of Patients and Medical Practitioners) Bill. Globally, only a few countries have legislation with discreet and unambiguous guidelines on euthanasia. The ongoing developments have raised a hope of India getting a discreet law on euthanasia in the future.

Keywords: Aruna Shanbaug; Euthanasia; Indian law; Physician-assisted suicide (PAS).

Publication types

- Euthanasia / ethics

- Euthanasia / legislation & jurisprudence*

- Legislation, Medical*

- Patient Rights / legislation & jurisprudence*

- Suicide, Assisted / ethics

- Suicide, Assisted / legislation & jurisprudence*

- Freedom To Die: A Look At Active...

Freedom To Die: A Look At Active Euthanasia's Position In The Indian Legal System

Lavanya gupta.

8 Sep 2021 11:46 AM GMT

Active euthanasia or voluntary euthanasia, sometimes also known as aggressive euthanasia is the act of voluntarily administering substances by a physician with the patient's consent which is capable of ending the patient's life thereby putting an end to their suffering which has led them to the decision to die in the first place. While passive euthanasia is seen as a much...

A ctive euthanasia or voluntary euthanasia, sometimes also known as aggressive euthanasia is the act of voluntarily administering substances by a physician with the patient's consent which is capable of ending the patient's life thereby putting an end to their suffering which has led them to the decision to die in the first place. While passive euthanasia is seen as a much more acceptable form of physician-assisted suicide as it includes the withdrawal of life support to critically ill patients resulting in their death, active euthanasia is still frowned upon.

Pain is the most visible sign of suffering and often times prolonged periods of pain often snatch the will to live in a person. The topic of Active euthanasia focuses mainly on people who are facing a chronic disease and are in a state of constant pain and are suffering and therefore want to end their life. While it does sound reasonable that a person who has a right to live should also have a right to die at their own volition, however, may doctors see it as a form of murder and the ethics involved in this process has what has mired it in controversy.

On one side it is seen that a competent adult with a sound mind and a thorough understanding of the situation should be allowed to make a choice that they deem fit even if it is to die. This should be solely their discretion and will. Many close members of the patient often see them in a constant state of pain and suffering and they believe that when all hope of an improvement and treatment is lost and steady deterioration of the state of the patient is theonly option available, the patient should be legally allowed to not prolong their suffering and find peace. This will also provide relief to the patient's loved ones who mentally suffer along with the patient on seeing their state. One must realize that the resources which are spent on such critical patients are expensive and can be put to save the life of a person who wants to live and not one who has given up hopes to live and is waiting for death.

On the other side of this conundrum lies the argument of the competence of the patient, because a state of pain or suffering is often known to cloud one's judgement add to that, the atmosphere of a hospital and the prospect of being confined to bed for a long period of time and constantly depending on others often makes the person prone to several psychological issues and a feeling of guilt for being a burden on their loved ones. Decisions taken in such conditions are often out of desperation and the feeling of losing all hope and will power to live due to the depressing atmosphere around them. A person with an undetected psychological problem like depression is often known to consent to die. Also, the fact that often such patients might be pressured into consenting by their families citing financial constraints due to their treatment should also be noted. They are prone to being manipulated into consenting even if it is not what they really want. Most medical professionals are often unwilling to allow the patient to undergo this process citing ethical and moral reasons as well as the Hippocratic oath taken by them, arguments like these are further bolstered by religious notions of certain communities where taking one's own life either by suicide or such consent is considered sin.

While both these sides are correct in their apprehensions, let us take a look at what the law has to say before arriving at a conclusion.

Laws Of Other Countries Allowing Active Euthanasia

The trend observed in countries that allow Active euthanasia is that most of them like Netherlands, Luxembourg, Canada (except Quebec) insist on the condition of the patient to be critical with no hope of recovery like those who are terminally ill certain cases like that of [1] Netherlands does not require this suffering to be physical, there are other countries that have a process in place to screen such patients by the means of a month long waiting period (Belgium), confirmation from an independent committee or doctor other than the one the patient is consulting (Netherlands).

[2] In fact, the model followed by [3] Switzerland is surprising in the sense that it allows Active Euthanasia only with the patient's consent and not Euthanasia for the mere reason that Active consent is not involved, Active Euthanasia is also not allowed if it may be driven by selfish motives like Inheritance of property by the relatives or their unwillingness to pay for the care of the patient which is quite opposite to that followed by the rest of the world. The Swiss model promotes the fact that the right to die is indeed the active choice of the patient and not something which can be made on their behalf which in a sense is more agreeable towards the Idea of freedom to choose death.

Position Of India

The Ideal of Right to die with dignity was incorporated under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution on 9 th March 2018 in the landmark Supreme Court judgement in the case of Common Cause vs Union of India which legalized the practice of Passive Euthanasia in India. The same judgement allowed the concept of 'living will' which means directions given by a person in advance regarding future medical treatment also including their express consent to remove lifesaving equipment in case they are incapable of giving consent at that time. The Indian perspective on Euthanasia is that 'withdrawal' or 'stoppage' of life saving treatments in such cases is not playing an active role in the death and thus morally acceptable whereas 'administering' substances which will cause cessation of life are morally unacceptable and in the present scenario would invite Section 309 of Attempt to Suicide under Indian Penal Code towards the Patient and if successful would attract Section 306 of Abetment of Suicide and Section 300 of Murder under the Indian Penal Code towards the person administering such treatment.

The current debate around euthanasia in India revolves around Active Euthanasia with one side considering it morally and religiously wrong along with suicide, at the same time the [5] report of the 42 nd law commission in 1971 referred to Manu's code and stated that people should have a right to end their suffering if they were living in miserable conditions, pain, or were diseased. [6] The 210 th law commission also supported this belief by calling for decriminalization of Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code. A step was taken in the positive direction with the Mental Healthcare Act,2017 with the Section 115 of the Act decriminalizing the same, however, whether the attempt to suicide is a criminal offence or not is still mired in controversy with two opposing laws applying to the same situation.

Though decriminalizing suicide is a step in the direction towards approval of active euthanasia, it nowhere guarantees for the same to be allowed in the near future, with the emphasis and recognition now being placed on Mental Health, Freedom of Choice in matter of life and death, the climb towards legalizing of Active euthanasia though uphill is bound to become a lot easier.

India should consider allowing Active Euthanasia as a solution for patients who wish to end their life, However, taking in the valid points raised by the opposition like determination of consent etc. safeguards for the same should be placed. There should be a proper way of determining the validity of the consent with conditions like the permission from an independent medical practitioner, or in the presence of a public officer in order to verify that the patient while giving such consent was indeed coherent and fully understood the implications of the same. There should also be a waiting period of a month involved so that the patient has the time to mull over the decision and withdraw their consent in case they change their mind. Distinction should be made on compassionate grounds to allow only those patients who have no option but to suffer from a pain or a disease and the best for them would be to end their life if they so choose. Care should be taken to not let the legalization of Active Euthanasia to be used by anyone as an easy way out of life. It is important to implement such humanistic remedies with utmost sensitivity with an ironclad system of filtering out genuine cases as remedies like these are often prone to being misused.

Views are personal.

[1] Penny Lewis, "Assisted Dying: What does the law in different Countries say?", BBC News, 6 October 2015, Available at < https://www.bbc.com/news/world-34445715 > (last visited on 5 September 2021)

[2] Samia A Hurst, Alex Mauron, "Assisted suicide and euthanasia in Switzerland : allowing a role for non-physicians", The British Medical Journal, 1 February 2003, Available at < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1125125/ > (last visited on 4 September 2021)

[3] James Ashford, "Countries where Euthanasia is legal", The Week, 28 August 2019, Available at < https://www.theweek.co.uk/102978/countries-where-euthanasia-is-legal > (last visited on 5 September 2021)

[4] Law Commission of India, "42 nd Law Commission Report – The Indian Penal Code" (2 June 1971) Available at < https://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/1-50/report42.pdf >

[5] Law Commission of India, "210 th Law Commission Report – Humanization and Decriminalization of Attempt to commit suicide" (17 October 2008) Available at < https://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/report210.pdf >

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,845,334 articles, preprints and more)

- Available from publisher site using DOI. A subscription may be required. Full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Euthanasia: Global Scenario and Its Status in India.

Author information, affiliations.

- Shekhawat RS 1

- Kanchan T 1

- Krishan K 3

ORCIDs linked to this article

- Krishan K | 0000-0001-5321-0958

- Atreya A | 0000-0001-6657-7871

- Shekhawat RS | 0000-0002-4253-8541

- Kanchan T | 0000-0003-0346-1075

Science and Engineering Ethics , 19 Jul 2017 , 24(2): 349-360 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9946-7 PMID: 28726026

Abstract

Full text links .

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9946-7

References

Articles referenced by this article (39)

Bbc.co.uk. (2009). BBC—Religions—Hinduism: Euthanasia, assisted dying and suicide. Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/hinduism/hinduethics/euthanasia.shtml .

Bbc.co.uk. (2012). bbc—religions—islam: euthanasia, assisted dying, medical ethics and suicide. retrieved june 29, 2017, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/islamethics/euthanasia.shtml ., bma.org.uk. (2017). bma—end-of-life care and physician-assisted dying. retrieved june 29, 2017, from https://www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/policy-and-research/ethics/end-of-life-care ., reporting of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the netherlands: descriptive study..

Buiting H , van Delden J , Onwuteaka-Philpsen B , Rietjens J , Rurup M , van Tol D , Gevers J , van der Maas P , van der Heide A

BMC Med Ethics, 18 2009

MED: 19860873

Castro, M., Antunes, G., Marcon, L., Andrade, L., Rückl, S., & Andrade, V. (2017). Euthanasia and assisted suicide in western countries: A systematic review. Revista Bioética, 24, 355–367.

Euthanasia in legal limbo in colombia..

Lancet, (9609):290-291 2008

MED: 18300377

Does legal physician-assisted dying impede development of palliative care? The Belgian and Benelux experience.

Chambaere K , Bernheim JL

J Med Ethics, (8):657-660 2015

MED: 25648645

Chavan, P. (2017). Should euthanasia be allowed in India? Ministry of Health & Family Welfare wants your opinion. Retrieved June 28, 2017, from http://www.thehealthsite.com/news/should-euthanasia-be-allowed-in-india-ministry-of-health-family-welfare-wants-your-opinion-po0516/ .

First do no harm: euthanasia of patients with dementia in belgium..

Cohen-Almagor R

J Med Philos, (1):74-89 2015

MED: 26661050

Daily News & Analysis. (2011). The hits and misses of the Aruna Shanbaug verdict. Retrieved June 29, 2017, from http://www.dnaindia.com/india/analysis-the-hits-and-misses-of-the-aruna-shanbaug-verdict-1517522 .

Citations & impact , impact metrics, citations of article over time, alternative metrics.

Article citations

Knowledge, attitude and practices (kap) of medical professionals on euthanasia: a study from a tertiary care centre in india..

Shekhawat RS , Kanchan T , Saraf A , Ateriya N , Meshram VP , Setia P , Rathore M

Cureus , 15(2):e34788, 08 Feb 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36915850 | PMCID: PMC10006483

Interface of Law and Psychiatric Problems in the Elderly.

Sivakumar PT , Mukku SSR , Tiwari SC , Varghese M , Gupta S , Rathi L

Indian J Psychiatry , 64(suppl 1):S163-S175, 22 Mar 2022

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 35599664 | PMCID: PMC9122138

Right to Life or Right to Die in Advanced Dementia: Physician-Assisted Dying.

Jakhar J , Ambreen S , Prasad S

Front Psychiatry , 11:622446, 21 Jan 2021

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 33551882 | PMCID: PMC7858261

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

New developments in India concerning the policy of passive euthanasia.

Kanniyakonil S

Dev World Bioeth , 18(2):190-197, 15 Feb 2018

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 29446214

Aruna Shanbaug: Is Her Demise the End of the Road for Legislation on Euthanasia in India?

Kanchan T , Atreya A , Krishan K

Sci Eng Ethics , 22(4):1251-1253, 15 Aug 2015

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 26276161

Controversies surrounding continuous deep sedation at the end of life: the parliamentary and societal debates in France.

Raus K , Chambaere K , Sterckx S

BMC Med Ethics , 17(1):36, 29 Jun 2016

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 27357285 | PMCID: PMC4928322

The end of life decisions -- should physicians aid their patients in dying?

J Clin Forensic Med , 11(3):133-140, 01 Jun 2004

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 15260998

Moral dimensions.

BMJ , 331(7518):689-691, 01 Sep 2005

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 16179707 | PMCID: PMC1226257

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

- THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

- Prospective Students

- Search Search

- bioethics euthanasia india past and present

The Bioethics of Euthanasia in India: Past and Present

Hinduism’s response to the question of euthanasia

By Purushottama Bilimoria | December 18, 2014

The Los Angeles Times carried an article (January 2013) on the elderly citizens of the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, who, perhaps ailing and suffering from debilitating pain, are being quietly sent off to their deaths, often with the use of a potion known as thalaikoothal. But what is Hinduism’s response to the question of euthanasia? How have the majority of Hindus been dealing with this issue? This becomes a critical question especially when confronted with, on the one hand, the availability of technologically advanced medical treatment regimes and, on the other hand, a significant lack of resources for the palliative care of a the subcontinent’s rapidly aging population of 1.1 billion. Surveys of ancient scriptural sources on the issue yield several ambiguities and contradictions. Hindu legalistic prohibitions against taking one's own life appear in Manusmriti , II. 90-91, V. 89; Yajnavalkyasmrti III.253, among other corpus known as Dharma Shastras Manusmriti also mentions fasting in order to draw attention to an injustice in a situation, human or cosmic, which might lead to one's death. These sources constitute the classical pronouncements on temporal law for Hindus, and are considered to be authoritative even today. Ancient Brahmanic-Hindu lawmakers (attributed with authorship of the aforementioned shastric texts) made self-killing an exception for a lower-caste man guilty of the murder of a Brahmin, who may thus throw himself into a fire ( Manu XI.73: Yajna . III.248) as well as for those who committed other heinous crimes against themselves (like taking liquor) or against others (e.g. adulterous relationships with higher caste members, incest, theft, perjury, etc.). Might there be limits and other sanctions, however, for a conditional intervention in circumstances which call for the swift release of the soul of the dreadfully injured individual, marking a turning point in the individual’s karmic cycle? Or, is the reverence for life balanced by the principle of dignified death, an implication derived from the inevitable decay of all creatures? For answers scholars often turn to historical instances and recorded practices, such as ascetic atmaghata or jauhar (mass suicide in the face of impending calamity, natural or human-made), the controversial sati ("suttee," though more needs to be said about the element of involuntary homicide involved here), fasting to death (that Mahatma Gandhi adopted as a political strategy and that Vinoba Bhave used to find release from his incapacitating illness). Instructively, there are parallel practices in India’s Jaina religious tradition such as sallekhana, prayovesana, santhara (voluntary fasting to death). Secular Hindus—Hindus and Jains who are less committed to their religion than to the culture and to the political ideal of India as Hindu, hence, like Gandhi, “secular” in Charles Taylor's sense of secularity—often cite the Jaina practice as evidence of a humanist approach toward empathic care for the severely ill, or toward those who are deprived of their "fundamental rights" to work, to a living wage, to equality and to the decent standard of life decreed in the Indian Constitution (articles 14-21). Secular Hindus argue that from the latter juridical rule a negative entailment can be derived (as indeed Indian courts have argued). To whit: when one of these basic rights is not forthcoming or abrogated by the state, the aggrieved citizen may exercise the right to die or resort to non-culpable auto-homicide. In recent times cases involving attempted suicide have come before the secular courts. A landmark case was of a vendor whose licence to sell vegetables on a street-side stall was revoked by the city administration; he there-upon took the drastic step of setting himself on fire in public, only to be arrested and charged by the police with criminal offence under section 309 of the Indian Penal Code. It is interesting that the state’s High Courts and, in at least two instances, the nation's Apex Court have compared such acts of attempted suicide to euthanasia (in the medical context) and adjudged the former to be constitutionally defensible–even though euthanasia is not yet protected under the law, and the analogical reasoning might therefore be a trifle over-determined. All of these considerations suggest a preparedness on the part of Hindus and of a large number of secular Indians to adopt an open (though cautious) attitude toward euthanasia based on the particularity of the case. Hindu and non-Hindu Indians alike ask whether euthanasia is, in a given situation, a humane means of minimizing the sufferer's immense pain and continuing harm to her potential good hereafter—rather than bend to an the ideology of deterrence inscribed in the outmoded colonial penal system still prevalent in India. Sources : Magnier, Mark. “In southern India, relatives sometimes quietly kill their elders.” Los Angeles Times , January 13, 2013, News. http://articles.latimes.com/2013/jan/15/world/la-fg-india-mercy-killings-20130116 . Bilimoria, P. “Jaina ethic of voluntary death, A Report from India.” Bioethics 331-355 (October 1992), Vol 6 No 4, pp. 331-355. Bilimoria, P. “Legal Rulings on Suicide in India and Implications for the Rights to Die.” Asian Philosophy (Nottingham) Autumn 1995, Vol 5, No 2. pp. 159-180.83. Bilimoria, P. “The Debate on Euthanasia in India.” Indian Ethics . Volume II. Edited by P. Bilimoria, Renuka Sharma, J. Prabhu, Amy Rayner. Indian Ethics vol II Gender, Justice and Ecology. Dordrecht: Springer; New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2015. Image Credit: Zuhair A. Al-Traifi / flickr creative commons. Managing Editor, Myriam Renaud To subscribe to Sightings and receive it by email every Monday and Thursday, please click here .

Author, Purushottama Bilimoria, is Honorary Professor of Philosophy and Comparative Studies at Deakin University in Australia and Senior Fellow, University of Melbourne, Visiting Scholar and Lecturer at University of California, Berkeley and Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, and Shivadasani Fellow of Oxford University. His research focuses on classical Indian philosophy and comparative ethics, Continental thought, cross-cultural philosophy of religion, diaspora studies, bioethics, and personal law in India. Recent publications are Indian Ethics I (Ashgate 2007, OUP 2008), Sabdapramana: Word and Knowledge (Testimony) in Indian Philosophy (revised reprint, Delhi: DK PrintWorld, 2008); Emotions In Indian-Thought Systems (with A. Wenta) (Routledge 2015), and Indian Ethics Vol II ( Springer 2015).

Purushottama Bilimoria

See All Articles by Purushottama Bilimoria

- International

- Today’s Paper

- Lok Sabha Polls

- Premium Stories

- Express Shorts

- Health & Wellness

- Board Exam Results

What is a living will, and the new Supreme Court order for simplifying passive euthanasia procedure?

Sc has relaxed the guidelines for ‘advance medical directive’ that it issued in its 2018 judgment by which it had legalised passive euthanasia under certain circumstances. there is a long legal history to the matter..

On Tuesday, a five-judge Bench of the Supreme Court headed by Justice K M Joseph agreed to significantly ease the procedure for passive euthanasia in the country by altering the existing guidelines for ‘living wills’, as laid down in its 2018 judgment in Common Cause vs. Union of India & Anr, which allowed passive euthanasia.

What is the legal history of this matter, and the issues involved?

First, what is euthanasia, and what is a living will?

Euthanasia refers to the practice of an individual deliberately ending their life, oftentimes to get relief from an incurable condition, or intolerable pain and suffering. Euthanasia, which can be administered only by a physician, can be either ‘active’ or ‘passive’.

Active euthanasia involves an active intervention to end a person’s life with substances or external force, such as administering a lethal injection. Passive euthanasia refers to withdrawing life support or treatment that is essential to keep a terminally ill person alive.

Passive euthanasia was legalised in India by the Supreme Court in 2018, contingent upon the person having a ‘living will’ or a written document that specifies what actions should be taken if the person is unable to make their own medical decisions in the future.

In case a person does not have a living will, members of their family can make a plea before the High Court to seek permission for passive euthanasia.

What did the SC rule in 2018?

The Supreme Court allowed passive euthanasia while recognising the living wills of terminally-ill patients who could go into a permanent vegetative state, and issued guidelines regulating this procedure.

A five-judge Constitution Bench headed by then Chief Justice of India (CJI) Dipak Misra said that the guidelines would be in force until Parliament passed legislation on this. However, this has not happened, and the absence of a law on this subject has rendered the 2018 judgment the last conclusive set of directions on euthanasia.

The guidelines pertained to questions such as who would execute the living will, and the process by which approval could be granted by the medical board. “We declare that an adult human being having mental capacity to take an informed decision has right to refuse medical treatment including withdrawal from life-saving devices,” the court said in the 2018 ruling.

- Kerala govt goes to SC over Governor withholding assent to Bills: The issues and the law

- Why Good Friday is observed, why its date change every year

- With less than 150 Great Indian Bustards remaining in the wild, what's driving their extinction?

And what was the situation before 2018?

In 1994, in a case challenging the constitutional validity of Section 309 of the IPC — which mandates up to one year in prison for attempt to suicide — the Supreme Court deemed the section to be a “cruel and irrational provision” that deserved to be removed from the statute book to “humanise our penal laws”. An act of suicide “cannot be said to be against religion, morality, or public policy, and an act of attempted suicide has no baneful effect on society”, the court said. (P Rathinam vs Union Of India)

However, two years later, a five-judge Bench of the court overturned the decision in P Rathinam, saying that the right to life under Article 21 did not include the right to die, and only legislation could permit euthanasia. (Smt. Gian Kaur vs The State Of Punjab, 1996)

In 2011, the SC allowed passive euthanasia for Aruna Shanbaug , a nurse who had been sexually assaulted in Mumbai in 1973, and had been in a vegetative state since then. The court made a distinction between ‘active’ and ‘passive’, and allowed the latter in “certain situations”. (Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug vs Union Of India & Ors)

Earlier, in 2006, the Law Commission of India in its 196th Report titled ‘Medical Treatment to Terminally Ill Patients (Protection of Patients and Medical Practitioners)’ had said that “a doctor who obeys the instructions of a competent patient to withhold or withdraw medical treatment does not commit a breach of professional duty and the omission to treat will not be an offence.” It had also recognised the patient’s decision to not receive medical treatment, and said it did not constitute an attempt to commit suicide under Section 309 IPC.

Again, in 2008, the Law Commission’s ‘241st Report On Passive Euthanasia: A Relook’ proposed legislation on ‘passive euthanasia’, and also prepared a draft Bill.

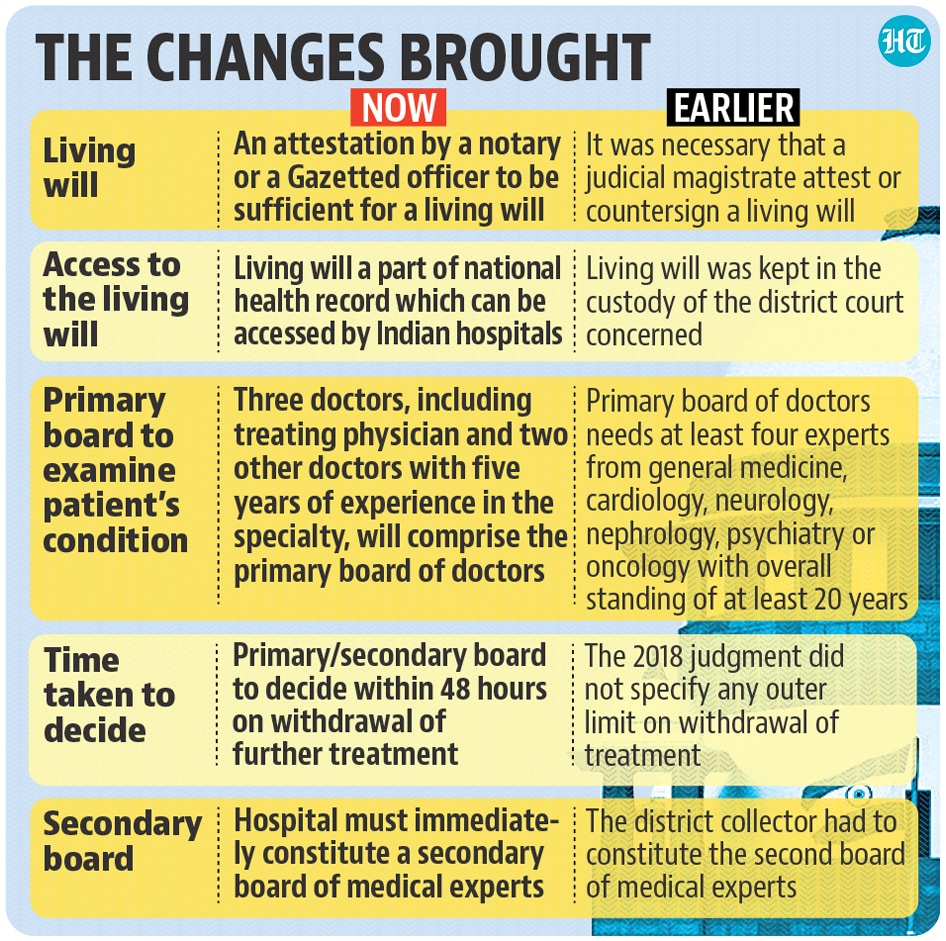

What changes after the SC’s order this week?

The petition was filed by a nonprofit association that submitted that the 2018 guidelines on living wills were “unworkable”. Though the detailed judgement is yet to be released, the Court dictated a part of their order in open court.

As per 2018 guidelines, a living will was required to be signed by an executor (the individual seeking euthanasia) in the presence of two attesting witnesses, preferably independent, and to be further countersigned by a Judicial Magistrate of First Class (JMFC).

Also, the treating physician was required to constitute a board comprising three expert medical practitioners from specific but varied fields of medicine, with at least 20 years of experience, who would decide whether to carry out the living will or not. If the medical board granted permission, the will had to be forwarded to the District Collector for his approval.

The Collector was to then form another medical board of three expert doctors, including the Chief District Medical Officer. Only if this second board agreed with the hospital board’s findings would the decision be forwarded to the JMFC, who would then visit the patient and examine whether to accord approval.

This cumbersome process will now become easier.

Instead of the hospital and Collector forming the two medical boards, both boards will now be formed by the hospital. The requirement of 20 years of experience for the doctors has been relaxed to five years. The requirement for the Magistrate’s approval has been replaced by an intimation to the Magistrate. The medical board must communicate its decision within 48 hours; the earlier guidelines specified no time limit.

The 2018 guidelines required two witnesses and a signature by the Magistrate; now a notary or gazetted officer can sign the living will in the presence of two witnesses instead of the Magistrate’s countersign. In case the medical boards set up by the hospital refuses permission, it will now be open to the kin to approach the High Court which will form a fresh medical team.

Different countries, different laws

NETHERLANDS, LUXEMBOURG, BELGIUM allow both euthanasia and assisted suicide for anyone who faces “unbearable suffering” that has no chance of improvement.

SWITZERLAND bans euthanasia but allows assisted dying in the presence of a doctor or physician.

CANADA had announced that euthanasia and assisted dying would be allowed for mentally ill patients by March 2023; however, the decision has been widely criticised, and the move may be delayed.

UNITED STATES has different laws in different states. Euthanasia is allowed in some states like Washington, Oregon, and Montana.

UNITED KINGDOM considers it illegal and equivalent to manslaughter.

With dogs, do size and breed matter? Subscriber Only

Kareena, Tabu's Crew washes away stench of recent Bollywood duds

How digital ads are becoming conversation starters Subscriber Only

What’s in a name? Subscriber Only

Can the world of food expand beyond chef whites and Subscriber Only

Pop faith Subscriber Only

Knox Goes Away is an engaging crime thriller

How can we create a healthier work environment?

3 Indian restaurants secure top spots in Asia's 50 Best

- Express Explained

- Express Premium

- passive euthanasia

Denied a ticket by the BJP, Varun Gandhi on Thursday released a letter to the voters of the Pilibhit Lok Sabha seat, which he won in 2019. He talked about visiting the constituency for the first time in 1983 as “a three-year-old child... holding my mother’s hand”, and ended with a promise, “not as an MP but as a son”, to serve it “all my life”.

More Explained

Best of Express

EXPRESS OPINION

Mar 29: Latest News

- 01 You’re incompetent to the core: Delhi HC slams MCD over delayed employee dues

- 02 Will act against those intimidating others: Ashoka University warns protesting students

- 03 In a first, Reliance buys 26% stake in Adani Power’s unit

- 04 Child panel issues transport safety guidelines for all schools

- 05 Congress complains against state BJP chief for alleged MCC violation

- Elections 2024

- Political Pulse

- Entertainment

- Movie Review

- Newsletters

- Gold Rate Today

- Silver Rate Today

- Petrol Rate Today

- Diesel Rate Today

- Web Stories

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Why I decided to...

Re: Why I decided to provide assisted dying: it is truly patient centred care

Rapid response to:

Why I decided to provide assisted dying: it is truly patient centred care

Linked articles.

How the Canadian Medical Association found a third way to support all its members on assisted dying

The courts should judge applications for assisted suicide, sparing the doctor-patient relationship

Religious and non-religious people share objections to assisted suicide

The Royal College of GPs and Royal College of Physicians have an opportunity to learn from mistakes of the past

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

The author in this article tries to explain the patient side of the story with regard to euthanasia and the dilemma a physician had while coping with the introduction of voluntary euthanasia in Canada in June 2016.

Voluntary Euthanasia represents a fundamental shift in the medical profession’s role and understanding of the role of doctor to end a patient’s suffering. Euthanasia is categorized in different ways, which include voluntary (conducted with the consent of the patient), non-voluntary (conducted when the consent of the patient is unavailable), or involuntary (conducted against the will of the patient). It can also be categorized into Active and Passive euthanasia. Passive euthanasia (known as "pulling the plug") is legal under some circumstances in many countries such as India. Active euthanasia, however, is legal in only a handful of countries (e.g. Belgium, Canada, Switzerland) and is limited to specific circumstances and the approval of councillors and doctors or other specialists. Some physicians prefer palliative care over euthanasia. This option helps to relieve patients’ pain while allowing them to fulfil their natural life span. (Reference1)

The scenario of euthanasia in India is no different than from other countries where euthanasia is illegal. However on 7th March 2011 a paradigm shift happened as a result of the Indian Supreme Court’s judgement on involuntary passive euthanasia. On 9 March 2018 the Supreme Court of India legalised passive euthanasia by means of the withdrawal of life support to patients in a permanent vegetative state. The decision was made as part of the verdict in a case involving Aruna Shanbaug, who had been in a Persistent Vegetative State (PVS) until her death in 2015 due to pneumonia after pulling the plug. The Law Commission of India gave certain recommendations on euthanasia. (Reference 2)

On 9 March 2018, the Supreme Court of India passed a historic judgement-law permitting Passive Euthanasia in the country. This judgment was passed in wake of Pinki Virani's plea in the Supreme court in December 2009 under the Constitutional provision of “Next Friend”. It is a landmark law which places the power of choice in the hands of the individual, over government, medical or religious control which sees all suffering as “destiny”. The Supreme Court specified two irreversible conditions to permit Passive Euthanasia Law in its 2011 Law: (I) Those who are brain-dead for whom the ventilator can be switched off and (II) Those in a Persistent Vegetative State (PVS) for whom the feed can be tapered out and pain-managing palliatives be added, according to laid-down international specifications. The same judgement-law also asked for the scrapping of IPC 309, the code which penalises those who survive suicide-attempts. In December 2014, the government of India declared its intention to do so.

In May 2016, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare issued a draft bill for public comment in order to create a conscientious decision. The Indian public are divided on this issue. While the majority of the scientific community welcomes it, others who have religious beliefs oppose it. Some believe that legalizing euthanasia would damage the foundation of society's value of respect for human life. (Reference 3)

We realise that Euthanasia can be considered as a boon for patients who are terminally ill or bed ridden for whom doing small daily things become a task. It provides a respectful death instead of a life dependent on others and self pity. Euthanasia provides the ending of the suffering in a peaceful and dignified way, surrounded by the loved ones of the patient. It also ends the psychological, physical and monetary stress the patient’s family undergoes while attending to such patients. Arguments for and against are discussed widely. (Reference 4,5 and 6)

It may have a negative impact on a few patients who do not have the will power to fight a disease. They may think it is an easy route to escape the hardships of life. Laws need to be more stringent to rule out malpractices. Psychological evaluation of a patient needs to be assessed.

References: 1. Ref. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/172264/10/10_chapter%2... CHAPTER- IV EUTHANASIA IN INDIA: LEGAL AND JUDICIAL PERSPECTIVE 2. Ref. http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/172264/10/10_chapter%2... CHAPTER- IV EUTHANASIA IN INDIA: LEGAL AND JUDICIAL PERSPECTIVE 3. F.no. S12011/5/2011-Ms (pt. I) 4. Rattan Singh in “Right to life and personal liberty: Some arguments with special reference to Euthanasia” in Journal of legal studies; page no-87 5.AIR 1995Ibid; page no-84Id 17 6. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aruna_Shanbaug_case )

Competing interests: No competing interests

India: Supreme Court Decides On The Issue Of Euthanasia ‘Once Again'

Contrary to popular belief, the recent judgment of the Supreme Court in the case of Common Cause (registered society) v Union of India & Anr 1 (Common Cause) , is not the first time that the Supreme Court has grappled with the issue of Euthanasia or has declared in its favour albeit partly. The Division Bench of the Supreme Court in the case of Aruna Ramachandra Shanbaug v Union of India and Ors. 2 had recognised passive euthanasia in 2011 and had even laid down elaborate procedures to execute the same. However, the judgment was far from satisfactory for the three judge Bench of the Supreme Court, who referred the matter to the Constitutional Bench, stating "considering the important question of law involved which needs to be reflected in the light of social, legal, medical and constitutional perspectives, it becomes extremely important to have a clear enunciation of law" and which in the words of the reference order was for the benefit of humanity as a whole.

The present judgment was delivered by a Constitutional Bench comprising of 5 Judges of which, the Chief Justice rendered the leading decision along with A M Khanwilkar, J. The other three judges concurred with the findings of the Chief Justice but passed three separate judgments on the issue. The present article discusses the views expressed by the Chief Justice in the leading judgment.

The Chief Justice opens the judgement by taking us through a philosophical journey with quotes on life and death ranging from those by Lord Alfred Tennyson to Dylan Thomas and the ancient Greek philosopher, Epicurus who understood death when he said,

"Why should I fear death? If I am, then death is not. If death is, then I am not. Why should I fear that which can only exist when I do not?"

The philosophical prologue given by the Chief Justice highlights the entire underlying theme of the judgment and the issue of Euthanasia which revolves around the fight to have the "right to die with dignity" included as a fundamental right within the fold of "right to live with dignity" guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. The issue first started with the case of P Rathinam v Union of India & Anr. 3 , wherein, a two judge bench of the Supreme Court while dealing with the challenge to section 309 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) (attempt to commit suicide) as being violative of Article 14 and 19 of the Constitution, held that fundamental rights have positive and negative aspects. Accordingly, right to live must include the right to die, hence, it concluded by saying that the right to live, which Article 21 speaks of can be said to bring in its trail the right not to live a forced life.

However, this decision did not stay a precedent for long and a constitutional bench in Gian Kaur v State of Punjab 4 overturned the decision in the P. Raithnam case to hold that the right to life did not include the right to die as understood under Article 21. The constitutional bench in that case was faced with the challenge to section 306 of the IPC relating to abetment of suicide which sought to rely on the earlier ruling in P. Raithnam case which had held section 309 of the IPC as being unconstitutional. The constitutional bench held that the "Right to Life" is a natural right embodied in Article 21 but suicide is an unnatural termination or extinction of life and, therefore, incompatible and inconsistent with the concept of right to life. The constitutional bench further stated that the earlier decision had failed to make a distinction between negative aspect of the right that was involved for which no positive or overt act was to be done. While dwelling into this debate, the constitutional bench tried to explain that sanctity of life or the right to live with dignity is of no assistance to determine the scope of Article 21 for deciding whether the guarantee of right to life therein includes the right to die and was thus, invariably drawn into the discussion of Euthanasia though it tried hard to distance itself from the same. The bench tried to clarify that the right to die with dignity at the end of life is not to be confused or equated with the right to die an unnatural death curtailing the natural span of life. While dealing with this issue the Court cited the English case of Airedale NHS Trust v Bland 5 , wherein, it was held that Euthanasia can be made lawful through legislation.

Relying on the Gian Kaur case, a two judge bench of the Supreme Court in the Aruna Shanbaug case upheld the validity of passive euthanasia which entails withdrawing of life support measures or withholding of medical treatment for continuance of life and for which no positive act is required as opposed to active euthanasia entailing the use of lethal substances or forces to cause the intentional death of a person by direct intervention, which as per the three Judge bench which referred the matter to the present constitutional bench was based on 'the wrong premise that the Constitution Bench in Gian Kaur had upheld the same'.

The Supreme Court analysed in length the various decisions of the Supreme Court in Gian Kaur and Aruna Shanbaug case and the international position in various jurisdictions relating to Euthanasia. The Supreme Court has clarified that the judgement in Gian Kaur case cannot be understood to have stated that passive euthanasia can only be introduced through legislation. It further held that in Gian Kaur, the word "life" in Article 21 has been construed as life with human dignity and it takes within its ambit the "right to die with dignity" being part of the "right to live with dignity". The sequitur of this exposition is that a dying man who is terminally ill or in a persistent vegetative state can make a choice of premature extinction of his life as being a facet of Article 21 of the Constitution. If that choice is guaranteed being part of Article 21, there is no necessity of any legislation for effectuating that fundamental right and more so his natural human right. Indeed, that right cannot be an absolute right but subject to regulatory measures to be prescribed by a suitable legislation which, however, must be reasonable restrictions and in the interest of the general public. The Court thus, clarified that Article 21 covers within its ambit only passive euthanasia and not active euthanasia.

Finally, the Court goes on to say that the right to live with dignity also includes the smoothening of the process of dying in case of a terminally ill patient or a person in permanent vegetative state with no hope of recovery and that is why it also recognises Advance Directives akin to a 'living Will' through which persons of sound mind and in a position to communicate can indicate the decision relating to the circumstances in which withholding or withdrawal of medical treatment can be resorted to. Elaborate procedure and safeguards for executing such Advance Directives have been provided in the judgment with the essential ingredients being that the treating physician of a terminally ill or patient undergoing prolonged medical treatment shall refer the matter to a Medical Board consisting of the Head of the Treating Department and at least three experts from the fields of general medicine, cardiology, neurology, nephrology, psychiatry or oncology with experience in critical care and with overall standing in the medical profession. The decision of the Medical Board shall be communicated to the jurisdictional Collector who shall then constitute a Medical Board comprising the Chief District Medical Officer of the concerned district as the Chairman and three expert doctors in the same field mentioned above. The Chairman of the Medical Board shall after taking consent of the executor of the Advance Directive or the guardian named therein, shall communicate his decision to the jurisdictional Judicial Magistrate First Class who shall then authorise the implementation of the decision of the Medical Board. The Court has also laid down the procedure for altering the Advance Directive and for cases where there is no Advance Directive. Thus, the Supreme Court has finally ruled that the interest of the patient shall override the interest of the State in protecting the life of its citizens and that right to live with dignity attaches throughout the life of the individual.

The clamor for Euthanasia has fallen short again with the Supreme Court holding that Article 21 embodies within itself only the right to 'Passive Euthanasia' and not 'Active Euthanasia'. Despite all the rhetoric of individual freedom of choice and the right to life being akin to right to die with dignity, the Supreme Court could not escape from the prejudice that Euthanasia can be used as a tool by unscrupulous relatives and subject to abuse. The Supreme Court noted that society has fallen to such levels of depredation that these rights cannot be made absolute and must be subject to regulatory mechanisms. In the end it is stated that it is the duty of the Courts to prevent the abuse of the process of law but the Courts would have fared better if individual freedom was not sacrificed at the altar of past bias. Nevertheless, it is a step in the right direction and one must embrace it with the hope that the Courts and law makers would one day realise that the word "Euthanasia" when translated from Greek means "good death".

1. W.P. (Civil) 215 of 2005

2. (2011)4 SCC 454

3. (1994) 3 SCC 394

4. (1996) 2 SCC 648

5. (1993) 1 All ER 821

The content of this document do not necessarily reflect the views/position of Khaitan & Co but remain solely those of the author(s). For any further queries or follow up please contact Khaitan & Co at [email protected]

© Mondaq® Ltd 1994 - 2024. All Rights Reserved .

Login to Mondaq.com

Password Passwords are Case Sensitive

Forgot your password?

Why Register with Mondaq

Free, unlimited access to more than half a million articles (one-article limit removed) from the diverse perspectives of 5,000 leading law, accountancy and advisory firms

Articles tailored to your interests and optional alerts about important changes

Receive priority invitations to relevant webinars and events

You’ll only need to do it once, and readership information is just for authors and is never sold to third parties.

Your Organisation

We need this to enable us to match you with other users from the same organisation. It is also part of the information that we share to our content providers ("Contributors") who contribute Content for free for your use.

Subscribe Now! Get features like

- Latest News

- Entertainment

- Real Estate

- RCB vs KKR Live Score

- Mukhtar Ansari Death News Live

- Election Schedule 2024

- IPL 2024 Schedule

- Bihar Board Results

- The Interview

- Web Stories

- Virat Kohli

- IPL Points Table

- IPL Purple Cap

- IPL Orange Cap

- Mumbai News

- Bengaluru News

- Daily Digest

SC eases norms for passive euthanasia

The supreme court on tuesday revamped the “cumbersome” procedure impeding the execution of passive euthanasia, laying down a definite timeline for medical experts, and cutting the red tape involved in the preparation of a living will by those who want withdrawal of treatment essential to life when they become terminally ill.

The Supreme Court on Tuesday revamped the “cumbersome” procedure impeding the execution of passive euthanasia, laying down a definite timeline for medical experts, and cutting the red tape involved in the preparation of a living will by those who want withdrawal of treatment essential to life when they become terminally ill.

A Constitution bench, headed by justice KM Joseph, paved the way for major changes in the guidelines prescribed by the 2018 judgment of the top court, making steps in the process timebound and less complex in recognition of the right to die with dignity.

The bench, also comprising justices Ajay Rastogi, Aniruddha Bose, Hrishikesh Roy and CT Ravikumar, tweaked the previous judgment to do away with the necessity of a judicial magistrate to attest or countersign a living will, and held that an attestation by a notary or a gazetted officer would be sufficient for a person to make a valid living will.

Also read: ‘PIL filed only to make Page 1’: SC junks plea against CM Adityanath

Instead of the living will being in the custody of the district court concerned — as directed by the court in 2018 — the bench said that the document will be a part of the national health digital record which can be accessed by hospitals and doctors from any part of the country.

Another crucial change brought about by the bench pertained to the constitution of the primary and secondary board of doctors who would examine the condition of the patient to take a decision whether the instructions given in the advanced directive should be carried out.

While the 2018 judgment said that the primary board should comprise at least four experts from the fields of general medicine, cardiology, neurology, nephrology, psychiatry or oncology — with overall standing in the profession for at least 20 years — the bench on Tuesday said that a team of three doctors, including the treating physician and two other doctors with five years of experience in the concerned specialty will comprise the primary board.

The primary board will preferably decide within 48 hours on the withdrawal of further treatment, noted the bench. The 2018 judgment did not lay down any outer limit for a decision by the primary board on executing the living will.

If the primary medical board certifies that the treatment should be withdrawn in terms of the instructions contained in the living will, the hospital shall immediately constitute a secondary medical board comprising a doctor nominated by the chief medical officer of the district concerned and two subject experts of the relevant specialty with minimum five years’ standing who were not part of the primary board. Under the 2018 judgment, the district collector concerned had to constitute the second board of medical experts.

“This board will also decide preferably within 48 hours... They may also need to reflect on the conditions or consult others,” said the bench, adding a 48 hour-deadline appears to be reasonable in such cases. There was no timeline specified secondary medical board in the 2018 judgment.

After both the boards approve the execution of the living will, the jurisdictional magistrate will be immediately intimated about the decision, said the bench.

If the hospital’s medical board denies permission to withdraw medical treatment, the family members of the patient can approach the relevant high court, which forms a fresh board of medical experts to enable the court take a final call.

While those making the living will specify the executors of their will for the consent on the behalf of the terminally ill patients, the family members of other terminally ill patients can also make a decision on withdrawal of treatment subject to the safeguards and the procedure mentioned for those who did not ready advanced directives.

The bench said that its order with the new guidelines should be sent to all the high courts for the framing of appropriate rules regarding storage of digital records of the living wills as well as to the health secretaries of states and Union territories for communicating it to chief medical officers of all districts.

The bench dictated a part of the judgment in the open court even as it approved the changes jointly suggested by Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine , the applicant in the case which wanted modifications in the 2018 judgment, and the Union government. The detailed judgment will be released later.

Last week, the Centre told the bench that it would not enact a legislation on passive euthanasia, adding that the anxiety to take someone’s life must not outweigh the requirement of essential safeguards. The government said that the top court’s 2018 judgment on allowing passive euthanasia after complying with certain safeguards sufficiently occupies the field and that there is no need for a specific law on the subject matter.

Also read: 'Laudatory...': PM praises Chief Justice over SC judgments in regional languages

The Centre’s response was to a query from the bench about the status of a new law since the 2018 judgment said that the guidelines laid down by the court shall remain in force till a legislation is brought on the issue.

The court was considering a plea, argued by senior counsel Arvind Datar and advocate Prashant Bhushan on behalf of the petitioners, who said that the three-step process encompassing onerous conditions has made the entire judgment nugatory, and that there has not been a single case where someone desirous of exercising the right to passive euthanasia could finally comply with the procedural requirements.

While hearing the case last week, the bench acknowledged that the 2018 judgment needed a “little tweaking” to make it workable.

In March 2018, a Constitution bench recognised a person’s right to die with dignity, saying that a terminally ill person can opt for passive euthanasia and execute a living will to refuse medical treatment. It permitted an individual to draft a living will specifying that she or he will not be put on life support if they slip into an incurable coma.

The five-judge bench in 2018 included the present CJI Dhananjaya Y Chandrachud, who, in his separate judgment, said: “Dignity in the process of dying is as much a part of the right to life under Article 21. To deprive an individual of dignity towards the end of life is to deprive the individual of a meaningful existence.”

- Supreme Court

Join Hindustan Times

Create free account and unlock exciting features like.

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

- Weather Today

- HT Newsletters

- Subscription

- Print Ad Rates

- Code of Ethics

- Elections 2024

- India vs England

- T20 World Cup 2024 Schedule

- IPL 2024 Auctions

- T20 World Cup 2024

- Cricket Players

- ICC Rankings

- Cricket Schedule

- Other Cities

- Income Tax Calculator

- Budget 2024

- Petrol Prices

- Diesel Prices

- Silver Rate

- Relationships

- Art and Culture

- Telugu Cinema

- Tamil Cinema

- Exam Results

- Competitive Exams

- Board Exams

- BBA Colleges

- Engineering Colleges

- Medical Colleges

- BCA Colleges

- Medical Exams

- Engineering Exams

- Horoscope 2024

- Festive Calendar 2024

- Compatibility Calculator

- The Economist Articles

- Explainer Video

- On The Record

- Vikram Chandra Daily Wrap

- PBKS vs DC Live Score

- KKR vs SRH Live Score

- EPL 2023-24

- ISL 2023-24

- Asian Games 2023

- Public Health

- Economic Policy

- International Affairs

- Climate Change

- Gender Equality

- future tech

- Daily Sudoku

- Daily Crossword

- Daily Word Jumble

- HT Friday Finance

- Explore Hindustan Times

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Subscription - Terms of Use

Explainer: Why did the Baltimore bridge collapse and what is the death toll?

What is the death toll so far, when did the baltimore bridge collapse, why did the bridge collapse, who will pay for the damage and how much will the bridge cost.

HOW LONG WILL IT TAKE TO REBUILD THE BRIDGE?

What ship hit the baltimore bridge, what do we know about the bridge that collapsed.

HOW WILL THE BRIDGE COLLAPSE IMPACT THE BALTIMORE PORT?

Get weekly news and analysis on the U.S. elections and how it matters to the world with the newsletter On the Campaign Trail. Sign up here.

Reporting by Lisa Shumaker; Writing by Lisa Shumaker; Editing by Daniel Wallis, Josie Kao and Tom Hogue

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Thomson Reuters

Lisa's journalism career spans two decades, and she currently serves as the Americas Day Editor for the Global News Desk. She played a pivotal role in tracking the COVID pandemic and leading initiatives in speed, headline writing and multimedia. She has worked closely with the finance and company news teams on major stories, such as the departures of Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and significant developments at Apple, Alphabet, Facebook and Tesla. Her dedication and hard work have been recognized with the 2010 Desk Editor of the Year award and a Journalist of the Year nomination in 2020. Lisa is passionate about visual and long-form storytelling. She holds a degree in both psychology and journalism from Penn State University.

Massive Russian missile and drone attacks hit thermal and hydro power plants in central and western Ukraine overnight, officials said on Friday, in the latest barrage targeting the country's already damaged power infrastructure.

A Russian court has remanded journalist Antonina Favorskaya in custody for two months after she was charged with participation in an extremist organisation, the Moscow court service said.