Teachers Workshop

A Duke TIP Blog

Body Biographies: Deepen Character Analysis in English and History Class

September 25, 2018 By Mandy Perret 5 Comments

What is a Body Biography?

How can we get gifted and talented students to deepen their understanding of literary and historical characters? How can we bring together isolated facts and help students visualize and analyze the impact of a person on a story or a time period? A Body Biography is a way students can use images and writing to express that analytical and conceptual understanding of characters. Gifted youth are ready for the rigor of digging deep into concepts, metaphors, and high-level interpretations. This differentiated lesson activity provides a way for gifted students to get to the higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

This assessment can be used in multiple classes such as social studies, history, government/civics, English Language Arts, science, and religious studies, to name a few. This task allows groups of students to select key samples of text and use symbolic visuals to show their understanding of the person’s words, feelings, beliefs, and impact. The goal of a body biography is not only to illustrate the literal looks of a person, but to also make a thorough visual representation, using symbols, colors, quotations, and a body outline. As students choose the best words and images to explain the person, they must analyze how to represent the historical or thematic impact of this individual with a symbolic representation of the body.

How do you get gifted students to analyze historical figures or literary characters in depth?

Share with us below!

How do students make a Body Biography?

To create the image outline, students can

- use butcher paper and outline a fellow student

- use a premade outline provided by you, the teacher

- or use digital tools to develop the image.

Each part of the body represents something.

- The spine represents the person’s values and beliefs

- The heart represents what they love or what means a lot to them

- The hands represent what they literally hold or what they hold dear

- Their feet represent where they came from and where they are going

- Their brain represents what they are thinking

- The mouth will speak quotes that represent the person’s typical speech as well as any other spoken aspects that students find important

- A mirror can be included to represent how the person sees themselves or how others see them (a mask can also be used)

- Ears show what others say about them

- Eyes show what they see or want to see

- Text–quotes from historical documents or literary documents–can be integrated in multiple places on the image, and not just presented near the mouth in speech bubbles. They can be integrated throughout the body outline and parts.

- a stomach to represent worries they have or worries others have about their choices

- the front to back to represent what is behind them and what lies in front of them

- literal or figurative objects from the person’s life

- clothing items that are typical of or symbolically representative of the person’s qualities

- any other body parts that help show a detailed understanding of the person and the role they play in history or in the text.

- Students should think about colors and what they represent

What is the person’s role?

This activity has two phases: a Planning Research Sheet , and Image Development, designed to help students understand why this person matters to history or the story. Through research and note-taking, followed by group conversations, gifted youth can get to the “big ideas” of a person’s impact by being selective about the details they share within the image. Gifted youth can develop a thesis, or Essential Understanding, about this individual.

Therefore students do not have to address every item listed above. What is key is ensuring that the details that students do choose are meaningful, cohesive, and connected to a larger understanding of the person’s role in history or in the story. View the first category of the rubric , Quotes: Role in Story or History, to think about the Essential Question students are answering: What is the person’s role in history or the story?

As they answer that driving question, students can gather facts about the person from various textual sources, whether primary or secondary historical sources, or from a literary text or secondary sources/literary criticism about that text. Students should share the research task within a group and each come to the task with a few pieces of evidence to discuss, and then have a discussion using each element of the body outline to see which evidence best fits each element.The combination of analysis of the person from multiple viewpoints as well as evaluating the sources to create words and visuals takes isolated facts and allows students to visualize and analyze the person throughout the story or time period.

How do you set up the assignment?

This project can be used for all students in a regular classroom or a gifted self-contained classroom. Group work or independent work is possible with this assignment. Students who need deeper challenge can research certain themes, impacts, or patterns/trends with their character and use additional body parts or visual and textual elements to render a deeper understanding.

You might assign students their person at the beginning of the unit so they can begin gathering ideas and information. This project works best in groups to develop deeper understanding and to compare/contrast what information each group member provides, in order to choose which words/images the group will use in the final product.

Materials for the Lesson

Here are some materials for assignment set-up.

- Planning Research Sheet . This document gets students researching and brainstorming. Students can complete this individually or in a group.

- Note that there is space for you to set requirements for number of quotes, body parts, and symbols to be included.

- Image Outline . If you don’t have time for students to create their own outline, use this one.

- My teacher resource book, Challenging Common Core Language Arts Lessons Grade 8 , Lesson 2.4 also offers additional resources you can use.

How can it be used as an assessment?

An assessment such as this one can close a unit of literary or historical study unit to evaluate student learning utilizing benchmarks and standards, depending on your location. This assignment can be connected to standards related to citing evidence from primary and secondary sources and evaluate their roles in events. This assessment also highlights the C-3 curriculum concepts of gathering and evaluating sources and communicating and critiquing conclusions. It allows students to use words and images to show their complete evaluative and analytical analysis of their person or character. Rigor is increased with the use of individual resources, extended primary/secondary sources, and the creation of additional body parts or interpretation. It allows students to use creative learning while challenging their higher-order thinking skills. You may wish to use this as a formative assessment as well.

Let’s take a gallery walk

The use of a gallery walk is a great way for students share this information and for the class to ask what the Essential Understanding is about the person and their role in history or the story. Body Biographies can be placed around the room with a number. Students in their groups will spend a few minutes viewing the other body biographies and making notes and creating questions to ask the other groups about their body biographies. (I use note cards for each viewing).

After students have viewed all Body Biographies in a rotation, each group will have a chance to present to the class key details from the image as well as the Essential Understanding. The goal of other students listening can be to help presenters better articulate Essential Understandings, by asking questions. The rubric can be used as a guide for conversation if this task is formative, and it can also be used as the rubric for determining a final evaluation if you choose the task to be summative.

By the close of this assignment, students should see a whole cast of characters or historical individuals who made significant impacts within a narrative, whether fictional or historical.

How do you get gifted students to analyze historical figures or literary characters in depth? Share with us below!

About Mandy Perret

Mandy Perret has taught middle and high school students for 16 years and is a mother of three children. She is the author of Challenging Common Core Language Arts Lessons: Activities and Extensions for Gifted and Advanced Learners in Grade 8. The last 10 years she has served in special education/gifted education. Her role as gifted teacher is to take learning outside the textbook and expand and enrich high school curriculum. She loves teaching the ways history connects with other subjects such as the arts and literature. She follows the philosophy that in order to help one’s students grow, the teacher must continue to learn. She holds three degrees from LSU, including an Education Specialist degree. She enjoys working with gifted students to prepare for their futures. Her motto is the words of Albert Einstein, “It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy of creative expression and knowledge.”

September 26, 2018 at 12:58 am

Absolutely love this and not just for gifted students. I’m going to do it across my KS3 and try with bottom set year 10s for use with understanding the characters from An Inspector Calls. Thank you for the inspiration! Will share with colleagues and promote your book

September 26, 2018 at 9:04 am

Elaine- Thank you so much for your kind words. Having to teach multiple grade levels each year, I love lesson ideas that can be adapted for all grades and interests. I am so excited you have a plan to use the body biographies with your class text.

December 1, 2019 at 5:29 am

Just stumbled across this. I love the idea and think it would be great for both GT and regular ed kids. Looking forward to adding it into an upcoming unit. Thanks!

[…] Body Biography […]

[…] Body Biography, The human body is a wonder of intricacy and excellence, including a wide exhibit of frameworks and organs that work amicably to support life. From the complicated organization of veins to the entrancing brain associations in the cerebrum, the human body has been a subject of interest and investigation for a really long time. In this article, we dive into the spellbinding universe of the body memoir, an exceptional and convincing approach to understanding and portraying the human structure. […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Conversation

- Kailey on Architecture: Discover, Dream, Design

- Earnestine on 5 Ways to Ignite Gifted Kids’ Curiosity

- From Objective to Assessment: Aligning Your Lesson Plans - TeachEDX on Making a PBL Mystery: Build Those Bones

- Zearlene Roberts on 5 Ways to Ignite Gifted Kids’ Curiosity

- Franck on 5 Ways to Ignite Gifted Kids’ Curiosity

Find Your Content

404 Not found

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Top 10 books about the body

Stories are lived in bodies, and made in them, and these books – from memoir to fiction, poetry and beyond – illuminate a central part of human experience

I n some ways, every book is about the body. No one lives apart from theirs, and so no writer, speaker or character exists fully removed from the simultaneously fragile and indispensable fact of a corporeal existence. Stories are lived in bodies and made in them; language itself is created in breathing and muscle, in gesture, contraction, release. I could list hundreds of books that draw on rich traditions of writing about illness; disability; gender; race; desire, politics; parenthood; daughterhood; living; and dying, all of them anchored in our bodies.

But instead, here are 10, across genres, and styles, and periods, that influenced the writing of my book Places I’ve Taken My Body and the living that led to it. Every list inevitably leaves something out, but I trust that these 10 books will lead you to a thousand more.

1. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley When Victor Frankenstein’s mother dies, he goes to university occupied with the “deepest mysteries of creation”, intent on learning how to make a living being, so that he might combat loss, death and decay. He sutures a man from salvaged parts, then animates the body he’s made. But the Creature, wonderful in theory, horrifies him once it is alive. The devastation that this wreaks for both creator and his Creature is without end. This is a dark and indispensable book about both building and having a body.

2. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World by Elaine Scarry An analysis of physical suffering that spans arenas from philosophy to medicine, religion to literature, and art, The Body in Pain is a reckoning with the foundational, inexpressible and inescapable nature of pain. A nuanced and expansive study of the ways that, throughout history, human beings have both inflicted and faced pain, and worked to articulate it, and to live with and through it. This book is one I return to again and again.

3. The Giant’s House by Elizabeth McCracken This tender, extraordinary novel about a small-town librarian named Peggy Court and the “over-tall” James Carlson Sweatt – who is six feet by age 11, then seven, and then eight – is a love story above all else. But it’s also an examination of the profound ways a body can both other and connect you, and of how you can love a body even as it fails you, or fails someone you love. It is both glorious and painful to be alive: this book knows both things in equal measure.

4. Poster Child by Emily Rapp Black At the most basic level, this is a memoir about growing up as an amputee. Rapp Black’s left foot was amputated at the age of four as the result of a congenital defect, and the title refers to the time she spent as a poster child for the US nonprofit March of Dimes. But the book is really a look at what it means to come of age in a culture that impels you to despise yourself. Sharp and smart, this book has been essential company for me in both adolescence and adulthood.

5. Inseminating the Elephant by Lucia Perillo The poems in this collection are endlessly inventive. Beautiful and funny, surprising and searching and wry, they rebuff your expectations the same way a mortal, changing, and changeable body does. Perillo had multiple sclerosis, and these poems are informed both obliquely and explicitly by her particular experiences of disability and embodiment. They’re also an extraordinary record of loving the world despite its darkness, and of singular and sparing epiphanies: “How immense the drowning when you’re the boy who drowns.”

6. The Two Kinds of Decay by Sarah Manguso Slender, strange, and lyric, this book turns the “illness narrative” inside out. A record of the years she spent with a rare and profoundly unpredictable blood disorder, the book articulates an experience of illness not from the temporal or linguistic remove of recovery, but in the language, shape, and timescale of sickness itself. This is a difficult, beautiful and absolutely singular book.

7. A Guidebook to Relative Strangers by Camille T Dungy Dungy is a poet, and this collection of essays – travelogue, memoir, and cultural study – proceeds with a poet’s exacting attention as it ranges across history and landscapes to explore motherhood, womanhood, writing, and the natural world. Concerned with the particular vulnerability and power of living in a black body, it is a masterclass in grappling with the many ways our bodies shape and attend us everywhere.

8. The Carrying by Ada Limon A collection of poems about daughterhood and infertility, ageing and grief, the rapture and rupture of the body and the brutal, ecstatic, animal force of wanting, this book is crystalline and clear, and beautiful enough to break your heart: “Fine then, / I’ll take it … I’ll take it all.”

9. Heavy: An American Memoir by Kiese Laymon There are all kinds of ways to characterise this book. A memoir about race and health, devotion and abuse. A story of growing up the black son of a single mother in Jackson, Mississippi. A book that unflinchingly interrogates the intersections between systemic and individual violence. A love letter. A bloodletting. An invocation, apology and rebuke. All of them are true, and all of them insufficient. Heavy is a gorgeous, difficult engagement with the weight(s) our bodies carry, conjure, wield and resist.

10. Teratology by Susannah Nevison A poetry collection rooted in a series of birth defects that affect the author’s legs and feet, and in a lifetime of surgical interventions, Nevison’s book is an act of myth-making, meaning-making and survival. “If your daughter is born / and her legs aren’t made / for standing,” the collection begins – and a whole, extraordinary world unfurls.

Places I’ve Taken My Body by Molly McCully Brown is published by Faber. To order a copy, go to guardianbookshop.com .

- Autobiography and memoir

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

404 Not found

Creative ELA Book Clubs are HERE Learn More

Create a Body Biography | Play with Characterization

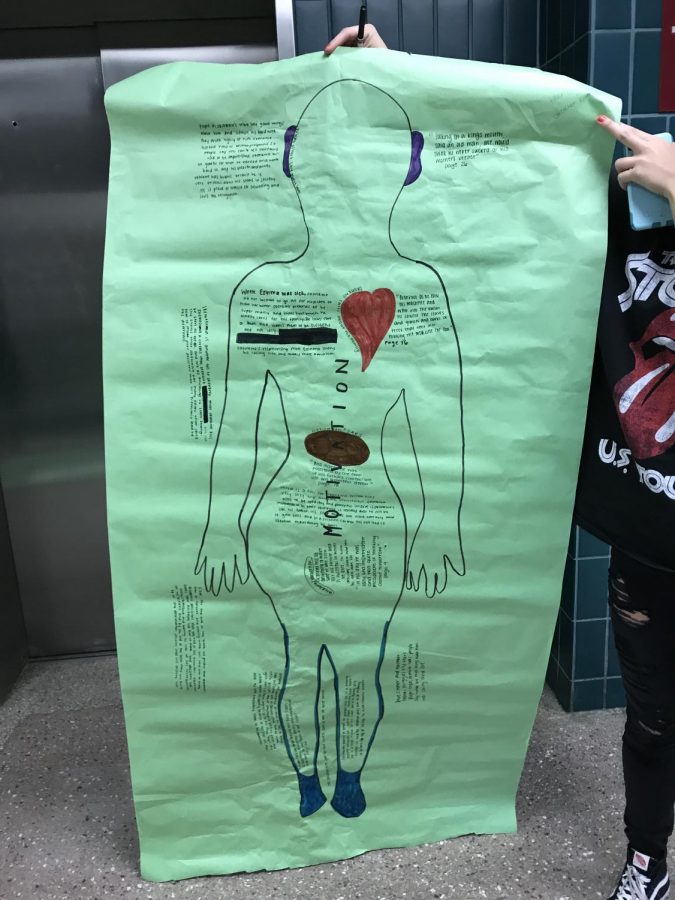

Spread out on the floor, large pieces of paper and markers between them, my students traced each other and turned their silhouettes into Greek Gods. Perfecting the look of the chiton and peplos, they also combed the Odyssey’s text for clues.

Who were these gods, goddesses, monsters, and tragic heroes? What did they look like?

What symbols represented the characters? What setting held their stories?

Not only did my students dig deep into characterization, they might have told you they enjoyed it.

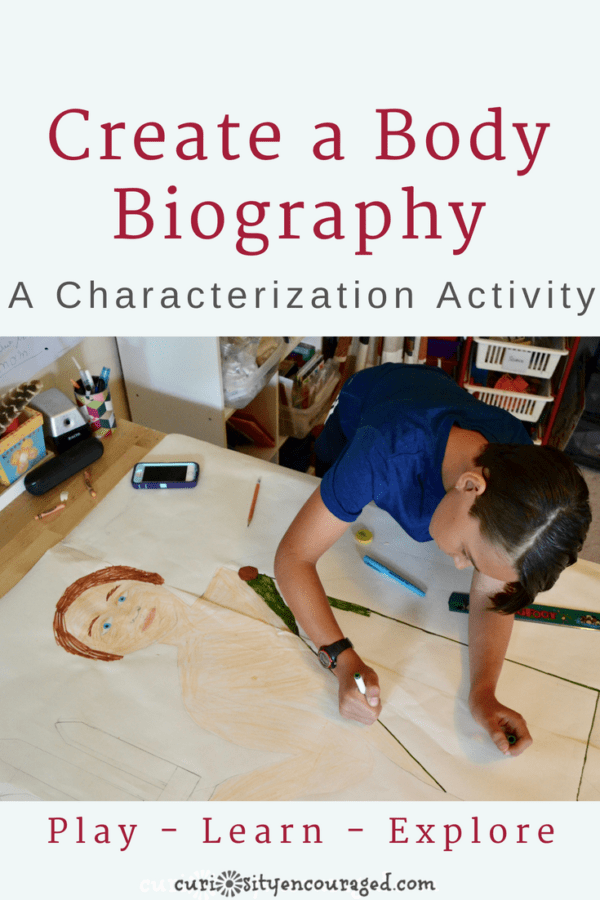

Fast forward a few years. After finishing up another book on Greek Mythology, I mentioned this project to my children.

Once again, spread across the floor, I watched children play with characterization. They thought about how Poseidon might stand, what Athena would

be holding, what each character would wear, and what objects or symbols best represented them.

We did some research, recalled what we’d learned in the different books and movies we recently experienced and spent a good part of the day immersed in our character’s body biography.

My eleven-year-old worked on his god for hours. He has plans to create a couple more and proudly hung the giant sea god in his room. My daughter’s Medusa head was an important part of her Athena biography. Drawing snake hair is pretty fun.

A body biography is a project a child or teen can create for any character in any story. It invites students to find and recall clues about who a character is. Add in a little research or more books and movies, and watch their findings come together life-sized.

Want to give it a try?

How to Create a Body Biography ~

A Body Biography is a life-sized representation of a fictional or nonfictional character. Use it as a post-reading activity, group project, or create one just for fun.

Materials: • Long, wide paper (taping two pieces together works fine) • Pencil, eraser, markers, crayons (work well for big areas) • Someone to trace • Books or websites to gather facts • Graphic Organizer-subscribe to my newsletter and you’ll have access to this free printable

Directions :

Choose a character., using the graphic organizer, brainstorm about the character- what symbols represent them, what could they be holding, wearing, what expression might be on their face, do a little research, if needed, to find out more about your character., lay down a piece of paper a little longer than the person who will be traced. tape two pieces together, if necessary, so the paper is wide enough., have the person being traced lie down (shoes get the paper really dirty so be careful) and decide how you want to position their body., trace your partner in pencil. have them sit up and trace their own thighs and mid-section. once traced, you’ll probably need to fix a few parts of the body., now begin to create your character, add- objects, symbols, words, other characters, a setting, colors, clothes, weapons- anything that helps make the character come to life..

*Note- these are a little addicting. Be sure to have lots of paper on hand!

My Resource Library has a free printable version of this activity. Not a subscriber? No worries. At the end of this post, subscribe to my newsletter, and you’ll have access to this activity AND every free printable I create.

If you’re interested in facilitating a unit study on The Odyssey , I’ve put my favorite activities together. Filled with pre, during, and post activities, links, and resources, this unit is everything you need to help your children or students engage and learn.

I’d love to see how your children’s characters turn out! Be sure to take a picture and tag me on Instagram or leave a comment below to let me know what character your children/students choose to create.

Share this:

About Kelly Sage

6 comments on “ create a body biography | play with characterization ”.

Pingback: Choosing a Homeschool Curriculum for 4th, 5th, and 6th Graders

Pingback: A Third Grade Interest-Led Curriculum - Curiosity Encouraged

Pingback: Greek Mythology- Books and Movies Your Kids Will Love -

Pingback: Family Activities at Home: Boredom Busters, Educational Projects, and Fun for All Ages - Humility and Doxology

Pingback: Choosing a Homeschool Curriculum- Early Elementary -

Pingback: Simple & Fun | Things to Do With Kids When You're Home All Day -

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Find a Resource

Hi, I’m Kelly. Curiosity Encouraged is where I share my passion for helping kids love to learn. It’s where I share the many things I’ve learned as a teacher, homeschooler, mother, and writer. Thank you for being here!

Create a Homeschool Journal

Create a Family Rhythm

Shop My Store

Curiosity Encouraged is now affiliated with Bookshop ! We love how they support small businesses.

Stay Connected:

- Custom Link

Your cart is currently empty!

- Close Menu Search

- Literary Arts

- pollsarchive

- Towson Athletic’s Twitter

The Talisman

Our mission is to work as a team to provide relevant and contemporary content that connects the Towson community, one story at a time.

- School News

Body Bios: An Inventive Analysis

Helen Logan , Staff Writer | November 7, 2017

Photo via Helen Logan, Staff Writer

This school year, a creative way of analyzing text has been implemented throughout select English classes. Teachers have been using body biographies as a way of understanding the deeper meanings located in the assigned books for this year.

You are probably asking yourself, what in the world is a body biography? They may sound a tad kooky but they are remarkably effective when used to analyze books. To start your body biography, you should lay down on a very large sheet of paper and trace your body to construct the base of the project. After building your base you can add whatever information and analysis you please.

The body biographies include abundant aspects of character analysis including components of a tragic hero, character foils and most importantly a solid connection of the character’s inner feelings to parts of the body. An example of one of these connections could be a nurturing character and the human heart which embodies love.

For English 10, I have Mr. Alford. His classes have been employing this technique for two years, while Ms. Nash’s classes have adopted this method of analysis for numerous years. Mr. Alford along with students enjoy the change of pace for novel analysis. When I asked Mr. Alford about his feelings towards the engaging, unconventional project, he claims he finds the project interesting because “the creative side appeals to some students” and “it gives students an alternative way to express their understanding of a character.”

The students appreciate the contemporary approach when discovering deeper feelings in a character. Junior Alyssa Sabellano recognizes that the project “prepares the students for the analysis of the entire novel.” She relishes the fact that body bios “follow the journey of the characters from start to finish.”

Sophomore Madeline Roberge concludes that body bios “are effective because it really helps analyze specific characters.” As you can probably tell, the body biographies are student approved.

Generally speaking, the body biographies seem like a favorable approach to looking at the text with a fresh pair of eyes. Now that you know how a body biography works, go out and make your own!

Faculty Basketball Game!

The Blood Drive at Towson High School

Towson’s Asian Student Union

Social Eligibility

INSIDE: Towson’s Forensics Elective Class

Morgan’s Message

The New Advisory 2023

Tradition in Creation: Composting at Towson High School

AP Classes & Exams

- Student Life

- Science & Technology

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Writing the Body: Trauma, Illness, Sexuality, and Beyond

Eileen myles, ruth ozeki, porochista khakpour, anna march & alexandra kleeman.

In September, Michele Filgate’s quarterly Red Ink Series—focused on women writers, past and present—brought together Eileen Myles, Ruth Ozeki, Porochista Khakpour, Anna March, and Alexandra Kleeman for a wide-ranging discussion about writing the body, from health to gender, sexuality, and beyond. The next Red Ink event, “ Writing About Depression ,” will take place at BookCourt this Thursday, 12/8.

Michele Filgate: I wanted to start out by reading a quote from Rene Gladman’s new book Calamity that Leads Books just published. I really recommend it. She says, “I began the day trying to say the word ‘body’ as many times as I could, for myself and for everyone in the room. I wanted to exchange the word with all my correspondents. I wanted to say ‘body’ to them: How is your body, or Write through the body, or How does the body activate objects in the room. I hoped to say ‘body’ and see a change come over your face: inside your body, the edge of the body, your body split. (I split you.) I hoped to reach a point in speaking where when it was time to say ‘body’ I could go silent instead. I’d pause and everyone in the room would sound the word within themselves. I’d go, ‘Every time you put a hole in the _____,’ and demur. Lower my head like a 40-watt bulb, look solemn. Or say, ‘We all carry something in our _____,’ and the collective internal silent hum would overwhelm my senses. This would be real communication: something you started in your _____ would finish in mine.”

So I put together this panel because I think it’s so important to talk about bodies, about women and bodies. Some of these questions may be directed to individual authors but I encourage anyone to answer or chime in whenever they want.

Ruth, in The Face: A Time Code , you sat in front of the mirror for three hours and wrote about your face. How did this mirror change the way you think about your body and your writing, and can you also tell us what your Zen is?

Ruth Ozeki: Sure, well mirror Zen, it turns out, is actually a practice, though I didn’t realize that at the time I came up with this idea to sit in front of a mirror for three hours and observe my face. The reason I did this was really kind of practical. I needed to write this commission for Restless Books—an essay about my face—and when I actually thought about sitting down to do this, it was just so appalling to me that I needed some kind of device that would get me through. Being a Zen practitioner, and certainly being a Zen writer, the way I approach these things is to sit with whatever it is that I’m writing. So in this case I thought, “Well I’ll just put a mirror up, and I’ll sit with my face for three hours”—which seemed like a suitably painful length of time—”and something will happen, right? Something will happen.”

It was interesting because after I did this, and in fact after I wrote the essay, I discovered that there is really a practice called mirror Zen. It started in Kamakura, at a temple called Tōkei-ji. It was a nunnery, and it was the only place in Japan during, you know the, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th centuries—around that time—where a woman could get a divorce. Women who were trying to escape abusive marriages, or who wanted to be divorced, would come to the nunnery, and they would throw their shoes over the nunnery gate, and that would gain them admittance. Then they would sit for three years and study their reflections in a mirror—they would sit zazen in front of a mirror—and the idea is that, by doing so, you start to understand your attachments and your aversions to your face. It’s a way of reclaiming your image.

So, I think that’s kind of what happened during those three years—three hours. It felt like three years. By sitting there, what I started to realize was that these were all stories that I had—that the face is just filled with stories, and the body is filled with stories. That was an interesting realization, and I think that the most sort of profound part of that was really at the end of three hours, when I walked out of the apartment, and I looked around, and it was astonishing because everyone had faces. Everyone has this complex relationship with—and sort of embedded stories in—their faces, and of course we can’t really see that in each other’s faces. But just the practice of sitting there for three hours opened up this world. So that was really wonderful.

MF: That sounds terrifying and amazing at the same time. Have any of you ever spent that much time looking at the mirror?

Eileen Myles: I just want to chime in that the phrase “the Zen writer” is amazing, an amazing pair of words I’ve never heard together like that. It’s really exciting.

MF: Eileen, I read an interview with you in Rookie mag where you said, “In some way I want my writing to take care of me. I want to live in my worlds. I want to carry my world with me like a shell. I want a home.” Do you think of your body as a home? And do you feel more comfortable with your body on or off the page?

EM: I sort of feel like writing creates the body, in a way. When I really think about how I felt when I was a kid—I mean, when I was a kid I guess I wrote somewhat, but I drew more, you know. That somehow delivered me into dreams and into some awkward state; it was some way to bear the present, or school, or whatever. But when I stop to think about it, when I really began to have a pretty frequent practice of setting words down, I started to exist. I started to exist on the page. It was almost like until I was out there, I couldn’t be in here, you know? I absolutely don’t say—I could never say—that I feel at home in my body, but I think that my writing created a safe place for it. Putting it out there created an account, or relay, which is kind of the world and my position in it. It’s really literal because so many of us have gotten to our identities through our writing, like it or not. Then you can feel kind of weighed down by that identity. But it started there and I still—I mean, the practice of keeping a journal is not constant in my life, but it’s important because then I’m very aware of when I’m not writing stuff in my journal. When I do, I know there’s a sort of presence, and it’s different from poetry and different from a writing project. It’s all very similar to the way you were describing looking at your face in the mirror and dropping those words on the page. The journal is a self-created image that starts to make it be that I’m here.

RO: It’s a reflection, too.

EM: Absolutely. Yeah.

Anna March: The thing that’s interesting to me about Eileen talking about getting your identity from writing—and I got a lot of this as a young women from her writing, actually—is how you get a lot of your identity from the identity marker of being a woman in society. So you don’t escape that, or you don’t live beyond that—a lot of times it determines the way culture looks at you, the way the world looks at you. So as much as I don’t want to go all Heidegger, I’m thinking about the way that you enter the space by dwelling in the space. I entered the space of feminism, and I entered the space of my body, by writing in it, but also the world enters me through that space of my body, for better or worse, and through the writing as well. So I think that’s kind of what were here about—how were at home in it and how we are not at home in it and alienated from it.

EM: So often they’ll say “she’s there,” but that doesn’t mean that I’m there. They start talking to “her,” and that’s not me. There’s a whole way of, you know, you start as an absence and then you have to write yourself into another thing.

AM: When you start all that caught up identity of “her,” who’s “her”?

Porochista Khakpour: For me, I’ve never felt that my personality matches me physically, so I’ve always felt out of place. I said at some event last year that I felt uncomfortable in every environment I’ve ever been in. I constantly feel uncomfortable. Everybody makes me uncomfortable: my family, my friends, lovers. Everybody I meet I’m not at ease. So I can try to write from a man’s perspective. I’ve written from the perspective of people with no sexuality. I’ve written from magical perspectives. It’s like an endless quest because, for me, the body is not a temple, and nature is not benevolent. I happen to be somebody who is ill with a pretty seriously chronic illness, so what I get really uncomfortable about is when women—I feel like there’s this goddess culture, right? Loving your body. I mean, I was a yoga teacher at one point, and I was the worst yoga teacher. But it was so violent for me because I don’t like super-feminine identity stuff. I’m wearing a dress tonight, and I know what I might look like, but I find it to be really uncomfortable and hypersexualizing. So I’m still trying to escape the body. Writing for me is my escape from it. It’s kind of like what Eileen is saying: it’s a way for me to multiply my identity so that I’m not trapped in this one.

Alexandra Kleeman: I just wanted to second what you said, about never feeling like you’re clean, or matching your external appearance. I remember going through puberty and having this experience that people were finding messages in my body that I never placed there. I have no way to rewrite them, but taking them to the page is a way to create reality, or specifically, recreate reality, as a way of taking that back.

MF: Porochista, you mentioned earlier that you’re chronically ill. You have a memoir coming out called Sick about dealing with late-stage Lyme disease, and you experienced a relapse while you were writing about it. I’m curious—Virginia Woolf wrote in her essay on being ill, “Illness is the great confessional . . . Things are said. Truths blurted out which the cautious respectability of health conceals.” Did you find that to be true while working on your book, and now that you’ve finished the book, do you feel differently about your body?

PK: The book that I sold, I thought I was going to be well—that I’d gotten cured from late-stage Lyme and cured of all my addictions. So I sold the book as really cheerful, like “Yay, I’m a survivor!” Actually, it was going to be a really shitty book, I think because there was all this false promise of, “You too can be strong like me and in the world.” But then I got hit by a car, an 18 wheeler, and I had this horrible Lyme relapse last winter where it threatened me daily. It threatened my writing life daily. So I actually couldn’t write it. To my editor, I was like, “Hey, do you think I can have some extra time because I heard writers always get extra on books.” They were like, “No,” and I was like, “I’m in the hospital, and there’s no reading of my liver, and they think I might be dying.” They said, “We’ll see if we can . . . maybe give it to us by May.” I was like “Okay, this is fucked up.”

I just somehow did it, but it was really dark, and the thing that helped me a lot was actually social media and writing to strangers. Maybe sort of like what Virginia Woolf was saying—I don’t know if she would be on social media a lot—but I was sharing a lot of inappropriate things. People were writing me like, “I kind of feel like you’re crossing some lines; it’s kind of gross. Did they really need to know about all the blood and all of that?” I had a lot of Miss Manners writing to me on Facebook, and I was like, “Go fuck yourself. First of all I’ve never been someone who’s that pristine or good.” But I was desperate, and my own friends and family were the least helpful people. People in the illness community—there’s a whole underworld there, and it appealed to me in a way that punk rock appealed to me. It’s this other world of invisible people who are all desperate and all there, coming up with crazy solutions. So Sick became a very different book, and I’m still finishing edits now. I resent saying illness is a teacher. I hate that stuff. But in a way it was, I guess.

MF: I have a question for you, Anna. In a piece you wrote for Literary Orphans called “What’s In a Name,” you say, “To rewrite our own redemption by telling ourselves our own true stories.” And you wrote a really terrific short story on angels this year called “Sometimes the Angel Has Dreadlocks and Talks Dirty to You.” Yes, we’re getting into the sex portion of the writing about bodies. I’m wondering—there are some really vivid and spectacular sex scenes in that story. When you write about sex, are you writing so you can inhabit your own body more, even if the body is fictional? I’m asking this of all of you.

AM: No, I’m not writing to inhabit my own body more, but I’m want to talk about another thing related to that question. First, though, I want to talk about what Porochista said about the policing. I write monthly for Salon ; I’ve written a lot about my body. I was a part of the Body Parts section of Salon for a while. There’s very little about my body that I haven’t published somewhere. But I live part-time in this town of 500 people . . . 500 people. I just want to say again, 500 people , and if you come up to me after I’ll tell you all of their names and all of their dogs. So I’m 48, I’m a raw feminist, a feminist killjoy, and I’m totally in your face about it, but I won’t buy tampons in my town. Because I’m 48, but I’m 14, right? I don’t want to get Charlie, who hands me my turkey sandwich four days a week to ask me questions about my period. I just don’t.

So I wrote this piece in Salon about how feminists need to not tolerate men. Feminism has a men’s problem. Forty percent of progressive men identify as feminist vs. eighty percent of progressive women. That is some bullshit. So, Eileen Myles comes over on my page and tells people to blow me when they’re giving me a hard time about Salon. Now I’m feeling all empowered, right? So I decide to go buy tampons. I get the tampons, and Charlie says, “Do you need Advil? Are ya’ feeling all right?” And I’m like, “Can I just get my tampons?” But he’s really sweet, and he’d say the same thing if I was buying Orajel. He’d be like, “Do you have a toothache?” So, a month later I go back and buy more tampons from Charlie. And he goes, “Didn’t you just have your period two weeks ago?” And I’m kind of pissed off. I shouldn’t have been, really. But I’m kind of pissed off, so I say that there’s an app—that you can track your period on the app. So Charlie, who is like 73 and the nicest person, who gives me half a pound of turkey on my sandwich, says, “I’d like to have that app so I can slip some chocolates in your bag for when you’re having PMS.” So here I am, this big bitch.

I go home, and do what I do because I live in a town of 500 people —did I mention that?—and I post it on Facebook. Right away a very important feminist—like, if you Google “very important feminist,” her name is the first one—she writes me, and she says, “You know, Annie, you really shouldn’t let people talk about your body that way.” I’m only trying to tell this nice story about how I live in this town, and how I’m 14 even though I’m not, and how I’m trying to do this thing, and here’s this guy who’s just totally not weird about it. What does feminist mean? It means living in your body out loud. But then I get policed, and people start sharing it, and there’s this full discussion going on about how it’s not okay. So I’m the one that has to deal with this story about inhabiting my body.

I don’t know if I write fiction that way, but it’s certainly true of my nonfiction that I write to inhabit my body more and also to hold myself to what I’m calling for or trying to call for in the world, which is to be more integrated, and to stop being ashamed of your body. I go out and have these talks around the country about shame in your body and all this stuff, and then I won’t buy tampons? No. So I’m trying to integrate that more. In terms of my fiction, though, I write what I like, and what I want to like, and I try to stay true to my characters.

MF: Back to sex. Why is it so difficult to write about sex? There are awards for bad sex writing, but there aren’t really awards, as far as I know, for bad food writing or bad nature writing, even those can be tough to write about too. So I’m wondering, why sex? What’s difficult about it?

AM: I think there’s a lot of policing. I participated in a talk for PEN this year called “Beyond Lolita”—which Michele curated or moderated, one of them. It was about writers writing. We had Steve Almond over there saying you should never do these nine things. Then we had Cheryl Strayed saying you should always do these nine things in your writing. I think there are two things: One, a lot of sex writing ignores that women have bodies, and have periods, and buy tampons, and have breasts, and have orgasms, and have them in different ways than men. We have this whole canon of literature where none of that is brought forth. So then when women start writing about that, or men write that about women, it’s like, “Ew, what’s going on?” Lidia Yuknavitch talked about this. Cheryl talked about how she had to fight for the four sex scenes that are in her memoir. I think there’s this sort of notion of “we don’t do that.” Scott Spencer, who wrote Endless Love , which is a horrible movie but a beautiful book, has some of the best—Jonathan Yardley, who hated everything said, “For a few hours of my life it broke my heart. It had some of the most magical, dazzling sex scenes.” He has this 13 page sex scene where Jade has her period, and they’re having sex, and there’s blood everywhere.

I think a lot of this is gendered, and I think also a lot of it is about comfort. There’s also this perception that less is more, and I don’t understand less is more. Why is less more? Why is that? Because Toni Morrison said that once in a Paris Review interview? Alyssa and I have had that fight on panels about this topic. She’s like, “Well, I think less is more,” but why? We can have 20 pages about people sitting at the dining room table which we’re supposed to keep. But then they fuck for, like, one sentence? I don’t get it. And now I won’t talk anymore.

RO: I was just going to say that we have to parse out this difference between bad sex and bad writing. So there’s bad sex, there’s bad writing, and then there’s bad writing about bad sex. I think these are distinctions that are worth naming. Probably the reason that there are no awards for bad food writing or bad nature writing is that food and nature aren’t really funny in the way that sex is funny, especially when it’s written about badly. I was hanging out with a group of writer friends of mine when Fifty Shades of Grey first came out, and I did an interpretive reading of the first two chapters. In the first two chapters of Fifty Shades of Grey there is very little sex. There’s just a lot of implying that there will be, but it’s so much fun to read out loud. Anyway, I think that there is something to be said for bad writing about bad sex. There’s a virtue there.

PK: Wait, where can we hear Ruth Ozeki read Fifty Shades of Grey ? [ Laughter. ]

MF: That will be the next event.

RO: It was a wonderful group of women. It was Karen Joy Fowler, Jane Hamilton, Dorothy Allison, and we were all living it up.

EM: Isn’t all porn bad? I don’t mean like gnarly bad, but what I mean is almost anybody I know who likes porn likes certain kinds of bad—they’re like, “I love bad 70s porn.” It’s sort of like the off register is the register.

AM: And if it’s true to character, is it bad? If your character is weird about sex and awkward, and can’t talk dirty in bed, and then tries to, then you should write that. You should be true to your characters no matter who they are. If you’re writing fiction, then you should be true to yourself and honest as much as the piece requires just like you would about anything else in nonfiction, right? I don’t think it’s that complicated. I think we make it complicated.

PK: I think it goes back to that idea about being honest. That’s where the humor comes in; that’s why we like awkward sex because my guess is that most people mostly have awkward sex. I don’t know, maybe I do. I think that we haven’t been honest throughout history; women’s bodies have been overly idealized and porno always presents this type of ideal. So we just haven’t been ourselves as human beings a lot. This is something my gynecologist said to me that’s so tragic. Many women don’t realize until much later in life what ovulation looks like or what it is, and they come and say they have yeast infections or something. Nobody ever told me about ovulation when I was in school. I didn’t even know what that was supposed to feel like. We don’t know these things. We are constantly disassociated from our bodies, our own physical realities, so we either go into the realm of the purple—which is like the overly idealized or that sort of porn thing—or it’s clinical, and there’s no in-between. I think this is a good time to be alive because we’re just approaching a sort of raw honesty.

EM: Have you guys seen the new drawings of the clit?

RO: Oh, yeah . . .

EM: It’s all over the media because they have 3D models now and never drawings. The thing that’s really weird is that they had these drawings several centuries ago, and they got suppressed for one or two hundred years because it was disturbing. It’s like the grotto, the dirty. Because it was too systemic and complicated; there was so much more than there was supposed to be.

AK: I want to second what Porochista was saying about learning about your body from sources that you should have been learning about these things, like in school or in a more professional way. I learned that the vagina can tear during childbirth from a set of poems by a Japanese poet. Then I immediately was like, “Let me look this up on the internet. Let me read more about it.” This should have been basic knowledge. It’s a bad surprise to spring on someone. [ Laughs ] But one of my personal answers as to why writing about sex is so limited right now is that I feel like we’re taking as our model a lot of film images, or images of sex, and those images are flattened in some way. They don’t have viscera; there is no mass to those bodies. I think that good sex writing would be writing that mass back in, and writing in all the parts of the body that have been sort of excluded from the sex act in descriptions. The digestive tract, the skin, the imperfections in the skin, what they mean, how it feels. I think what gives sex so much gravity is that you’re negotiating your body with another person. It’s not that you’re one, and that’s so wonderful, it’s that you’re actually doing this with another person and they don’t always do what you want them to do. And there’s friction, and it fails sometimes, and then it starts working later, or it fails for moments. That’s what’s bad for me.

EM: I just want to add that what was dirty about you reading Fifty Shades of Grey , Ruth, is that you were the wrong body. I think if you take the text and put it over the right body, then it becomes another type of writing, another type of porn, another kind of permission to hear it. It’s almost like the text doesn’t matter.

AM: I wrote a whole novel about a 16-year-old girl who really wants to have good sex, and women I knew were like, “Oh, man, hot.” I went through so much of that when I was a teenage girl myself, and men sometimes were like, “Teenage girls don’t want that. Teenage girls don’t think that way.” I mean progressive, good guys, were like, “Really?” I think sometimes writing gets called bad writing, untrue writing because it’s not heteronormative, it’s not the male gaze: it’s queer sex, it’s disabled sex, it’s not Philip Roth. Thank god for that.

PK: A lot of what we’re talking about here, I think, is, from the perspective of this moment, and a lot of that is being dominated by white women too. So there are a lot of cultural factors at play, where I sometimes want to be like, “Okay, rad white feminists. This a great moment for you, and I’m with you mostly.” I’m sorry to even go here in a way because I know there are other people of color here—thank god, for once. But it’s also like, this conversation, when it just goes to white women, it becomes dangerous for a lot of the world. I’m watching people I really like on social media going off about the burkini, right? And it’s so hideous. Eileen, you have a great twitter essay about this, and you were literally the only white person I saw talk about the burkini in a sophisticated way. That to me is a major issue about women and the body right now, that we’re telling women half the time that they’re not wearing enough clothes, or they’re wanting to be covered up and then we tell them, no, you have to take it off—which, like Eileen was saying, it’s violence. So I always want these conversations to include other cultures as well because it’s different.

MF: Me too, and this actually leads me to my next question about that. I want to talk about bodies that ignorant people try to silence. I’m thinking of many different categories of women: transgender people, disabled women, aging women, women of color, women who have been raped or sexually assaulted or abused, women of all body sizes, women with eating disorders, women who have strong opinions, women who are too scared to share their opinions, women who run for the presidency of the United States, mothers, child-free or childless women. How can we amplify all of the bodies this society tries to make invisible?

AM: Well, we can write them. Is it a trick question? We can write them, right? We can write them. We can read them. That’s the other thing; we can’t just write them. We have to buy and support independent booksellers, and the fiction and nonfiction that we want to read. It’s great to say we want literary fiction, but we have to go to our independent bookseller to buy those books. So we can write them, we can buy them, we can read them, and we can promote them. I think that’s how we amplify them. And we call out; we say, I don’t care that anyone loves this book by so and so, I think that the sex is heteronormative and white and not all that. I think we should do that as critics sometimes.

EM: I’m having a hard time summing up what I’m trying to say. But I feel like part of the problem with—I don’t mean the question exactly—but when we talk about all these different bodies, the problem is the stillness of the question, or the stillness of the subject of identity, as if this is about a transgender person, and this is about an Asian person. We’re always kind of writing about books or thinking about books or text as if subject matter is this static frontal thing that’s squared in the center. I think the problem with the way so many bodies are written about is that they’re always not in passing. They’re being dissected and held still. Is this the real world in which people come onstage and offstage? I mean like, why isn’t there a minor despicable transgender character—just because that person exists rather—than those questions of is this a correct novel about a transgender person by a correct transgender author, you know what I mean? I think that we just live in this much more moving way which isn’t reflected in our text at all. I’m only starting to scrape the surface of it, but it’s framing; it’s like our conceptual frames are fucked up. That goes directly into the writing and the books are sold that way, are written about that way. And then the inadequacies of the writer are shown up in a particular way rather than the fact that the whole world is not true.

MF: I think that’s so right, and I think we’re putting people into boxes too much, which is basically what you’re saying. We’re trying to say, this is the box they go in, and that’s bullshit.

EM: The subject matter is a fiction.

AM: For three and a half years I’ve had a partner who is a complete paraplegic, and I cannot tell you how writers—how editors, rather—wanted me to write about the complications of our sex life. And I was like, “Well, really there aren’t any.” And editors were like “No, no, no. We want to pay you a lot of money. We don’t want to pay you for these other things. We want to pay you a lot of money to write about this because we want to hear this story, because we thought here’s this frame, here’s this story of the disabled sex . . . ”

EM: That’s exactly the other disabled sex story I know of from another writer who was telling me that she had written this book all about her incredible sex life, and they were like, “This is not possible.”

AM: They wanted me to write that. That’s what they wanted me to write.

EM: Hers was “too much.” It gets back to the clothes issue. It’s sort of like policing sex. It’s always this “too much.” It’s the wrong person having sex.

AM: And the grappling. They wanted to do all this grappling. I told them, “Dude, that was 20 minutes over beer. We haven’t talked about it since.” What you’re saying, though, about the wrong person: it’s like we want women to be virginal and not have these desires, teenage girls don’t do this, and then all of a sudden we expect them to be these sex maidens when they’re 30. I don’t know how we expect them to get there. But we’ve sort of have been writing: teenage girls do this, women in their early 20s do this, and then in their 30s they do this, and then at 40 they stop having sex. [ Laughs ]

PK: I think this stuff comes into a fever pitch, though, at times. I’m looking at this from a slightly different angle. It happens when we’re in times of extreme misogyny, or homophobia, or transphobia, or racism. Writing becomes this model minority trap where before I can write about, say, a Muslim woman who’s wearing a veil, she’s got to be presented as—I’m not saying she has to be—but my instinct would be, in this climate that we’re in today, to make that person a really good person instead of a bad person. Every fucking day I feel like I’m assaulted by this other message. It becomes very challenging to write completely freely when you’re in this environment that we’re in today. This election has just been, like: everything’s out there. It’s not like any of this got created by the election, but it’s really laid it bare, and it’s worse than I thought it was. It’s kind of hard to think of how to create within that.

MF: Yeah, absolutely. Alexandra, you talked about the strangeness of the body, of writing about all of the body when you’re writing about sex. You said in an interview for Electric Lit, “Eating is something we do almost without thinking about it, but within that act is the crushing-up of another thing’s life structures with your own teeth, the pre-digestion inside the mouth, the genuine digestion in the stomach, the continual death on a large scale of bacteria living within us.” Aren’t you guys hungry right now? [ Laughs ] “We need it in order to get nutrients from food-material. It’s violent and amazing, and looking microscopically at this quotidian activity shows us something about how messy our lives are, whether we perceive it or not.” I feel like a lot of writers shy away from writing about bodily functions. Bodies are strangers, you remind us. And I wonder whether writing about this strangeness has made you feel it more acutely. Is that acknowledgement of our body’s strangeness liberating in itself, since recognizing it forces us to maybe suspend our ideals of cleanliness, perfection, or a narrow definition of health?

AK: That’s a lot of questions. [ Laughs ] I came to writing about the body when I already had a writing practice going on, but I realized that I was treating my body like an impediment to writing. I was trying to sort of tamp it down when I got hungry, or when I got tried, or when I ate, or needed sleep. I was moving further away from my body and also being very unhealthy. And so part of what I wanted to do was take my body out of this obscure zone, or out of this sort of transparency zone where it seemed ignored or like someone had sent out an alarm. But then I don’t think that writing about my body at all was what brought me closer to it because I think there’s one way of focusing on the body that makes it almost dysmorphic to me. When you search up pathologies it becomes a constant source of pathology, and you can’t accept the perception of the fairly normal process in your body for a fairly normal process. Not every signal is an alarm, right? I started thinking about auscultation, an obsolete medical practice of listening to the body to try to assess what’s wrong with it, and working sort of on spending time—I don’t want to call it meditation because I’m not a professional—but listening to my body, and trying to pay more attention to it, and appreciate the signals it sends for what they are, I guess.

For me, the way back into my body was more thinking about these unseen processes, processes that I have to believe are going on but I can’t see traces of. And also thinking how they connect me to the world because the number one thing about my body, for me, is that it is my interface with the world. Without it there’s nothing for my mind to do. Although sometimes when your mind is really active you can almost believe it will go on by itself. But it doesn’t. It relies on the outside world. I feel like thinking about these processes, thinking about the bacteria, thinking about myself as an ecosystem actually makes me feel much more alive and much more in touch with what’s out there.

RO: I think that really is a definition of meditation. It’s being a body. I mean, you’re sitting, you’re being a body, you’re paying attention to the signals. It is exactly that. It’s becoming aware of the body as an interface with the world, that there’s this interdependency that’s happening. It’s interesting because I think that when I’m teaching writing I always have my students sit first. They sit in silence first, and we do a body scan and just sort of settle and spend five minutes just being bodies, and then move from there into writing. It seems to me that literature works because we are all bodies, because we have bodies with which we respond to the world. Our readers do too. So when that experience is translated and evoked on the page, readers respond to it precisely because they do have bodies. If readers did not have bodies, we would not have literature. So the tie there between body and words is a really important one.

AK: I used to work in cognitive science. We were testing body cognition in the language labs, so what we were exploring was this effect that when you hear the word hammer, you can actually see activation in the motor center; you can see a change in the muscles that use the hammer. It’s this sort of knowledge of the world that would be really hard to represent logically, or as a proposition, or to define. Like what is a hammer? It is an object. How do you use it? You can write pages on that. But words connect to the body in this really deep way and immediately.

MF: I want to talk about gender and vulnerability. Eileen, you said in an interview with Slutever that when a man writes about his own experiences, he’s seen as vulnerable, but when a woman does it, she is criticized. And the word confessional is often used in a condescending tone to talk about women’s writing. So how do we get around that? How do we use our bodies on the page to fight that notion?

EM: I think it’s more that it’s the same old thing. I think there are ideas of how women are and how men are. When men do certain things they’re supposedly being incredibly different and fresh. Like if a man writes in a personal way, or writes in an abject way, or writes about what a loser he is, or writes about how vulnerable . . . I mean it’s such a rage in the new kind of loser-guy film. It’s like, “Oh my god he’s so funny. He’s naked and he’s dancing. His girlfriend comes in and breaks up with him. That’s amazing.” But what female would be framed that way? That’s just what some sad, slutty girl would be doing and just getting dumped because girls always get dumped. So It’s sort of like we go through these ages of . . . I remember the first time I read in some magazine that different eras had a certain nose; all movie stars were supposed to have the 1930s nose and so on. I think that just in literature—in the 80s you were supposed to be a kind of postfeminist; every female narrator or even writer was the utter top. We really wanted the top female writer because there was no position, no area for masochism. I just feel I don’t identify as a body, but I definitely identify as a masochist, and masochistic storytelling being not so much, you know, constructing a story out of what’s there and dominating the material so much as not having an agenda before I go into it and start and what I find and then rearranging it accordingly. I know that as a female, I’m supposed to write this story and writing the story that I have instead is like gender action in a way.

MF: I interviewed the incredible writer, who I think a lot of us on this panel really admire, Lidia Yuknavitch who writes about the body all the time and in fact has a class she teaches called Corporeal Writing. She said in the interview, “To my knowledge, no one’s corporeal experience is limited to the novelistic plot points I see supersaturating the market. We are more contradictory than that sexually. Our sexuality is far in excess of those puny stories. Our sexualities deserve better representation than traditional narrative has allowed. But I’m not doing anything new . Walt Whitman. Or Sappho. Or Duras. Or Acker. I mean, Jesus. Let the body go. Let it rise inside language and shatter the story.” How can you let the body go like Lidia suggests?

EM: By not dying. [ Laughs ]

RO: By not dying? I would say by dying. [ Laughs ]

AM: I mean one thing I heard—and, Michele, you probably heard this too, I think you heard this that night when we did “Beyond Lolita”—one thing I heard from all the women who did the panel who write fiction is that there’s always this thing where people think you’re writing about yourself. I mean, I’ll tell you it’s a real thing. I can’t tell you how many men this year have said to me, “So, I read about Daisy in that story.” And it’s like, “Really?” They assume that it’s you and that’s what you want to do in bed. I’m going to write what’s true to the character. I’m going to write the character I want to write. I’m going to give the character the sex I want to give the character and not worry about that. But I heard from all of the women fiction writers, “Oh, where are all the people going to fit?” I heard from none of the men who were writing fiction but from all of the women fiction writers like Cheryl said when she wrote Torch, “I thought, oh, I want to have kids. What are the kids’ teachers going to think about these sex scenes I wrote?”

EM: I sort of disagree in a way. I feel like everything you write is you. I just think it’s my choices. It’s not like, this is an illustration of the philosophy of Eileen, or my literal existence, but it’s my pornography. It’s the color I want to be with for chapters and chapters, it’s the period of history. The thing that’s weird, I think is, when somebody is overly excited and appropriative about your choice. I mean, every time a man does something to me that I feel like that’s fucked up. It’s like I’m passing through a hallway and somebody just touches my hip a little bit, because isn’t that appropriate? To make a little room around a gal? Like what the fuck! Don’t be an asshole. I think around that same remark . . . it sort of presupposes that you’re sexually available to this person, and that these are appropriate gestures—like you’re there in their field of vision, and this may be done.

AM: Absolutely and, you know, there’s Judy Bloom. We don’t always think about Judy Bloom, but Judy Bloom talks about this really eloquently because she wrote Wifey, where she has all this really hot sex going on, in the 70s, at the same time she was publishing Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret and all that. She talks about giving your characters that stuff and not letting people appropriate you. Also, if you haven’t read Wifey yet, I suggest you all go do read it. That’s some good sex writing

RO: I was just thinking of Virginia Woolf’s idea about killing the angel in the house. It was a lecture, actually, that she gave, but there’s this idea that in order to let the body go that the necessary step is to kill the angel in the house. And there are many ways of doing that, I think. But personally, it was very much about letting my father’s surname go. Ozeki is a pen name. I only started using it when my first novel was about to be published. It was fascinating. My father was dying at the time, and he’d been raised as a Christian fundamentalist. He had family who was still alive, and he was very proud of the fact that I was publishing a book. He knew that I always wanted to. But I could tell that there was something really disturbing him about it. And finally I just said, “I mean, yeah, there’s sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll in the book. Is this going to bother you that I’m publishing it under your name?” And he burst into tears and said, yes, he was afraid that his sister would find it because she was still a fundamentalist Christian, and that she would be ashamed. So it was like , ugh. It was a blow. But I decided at that point to publish under a pseudonym, and it was the most amazing thing because I did the edit of that book knowing that I was going to be publishing under Ozeki. It was literally a feeling of letting the body go. All the crampedness, the restriction, it just disappeared. So I was able to edit it with the kind of freedom that I had never had in my writing before. It was really wonderful. The problem is now, of course, Ozeki is my name. So now I need another pseudonym if I’m going to start publishing Fifty Shades of Grey.

PK: I think that’s really interesting because I think personally, as creators, it’s really important for us to let go. The thing of being a writer is you’re also a reader; you’re a consumer of art as well. What I like about this period, what I like about my students or the people that I’m around, is that they’re thinking more about the body, and how to approach different bodies, and how they should address bodies. So maybe that’s like what these politicians talk about as being politically correct. I see so much disdain around the word “consent,” a concept I think is really radical and really helpful and has saved lives. I think that I don’t really want to let go because I don’t think were there yet societally. We haven’t faced certain bodies. We haven’t thought of certain possibilities. How is it that we’re just now having discussions around trans people? How is it that a whole group has been invisible for so long? For the first time in my life, just in the last two years, we’re talking about what pronoun we want to use. I hear that being made fun of on late night TV or something, and it’s like, what’s so funny? Trans people were committing suicide. It’s too much work for you to use the right gender pronoun? It’s just really shocking to me, so I actually think that one of the right things about the internet—which has been in my head a lot in this panel—is that it does create a safe space for us to sit back and think a little bit, get information, and be exposed to different people without just projecting our selfhood onto different types of people. I think that thinking and moving slowly and holding on are also important.

MF: I like that. Is the body related to empathy? The root of the word path, which means feeling or disease, would lead us to believe so. Empathy is such a buzz word these days, but what does it have to do with writing about bodies?

RF: I think literature works because we have the ability to empathize. We have the ability to imagine, to inhabit other bodies, and so a writer who is doing her work well is creating an empathetic site, a site of empathy where you can lead your way into it somehow. You can write your way into it. You can read your way into it.

EM: I think reading is empathetic. My decision about whether to keep reading a book or not is utterly an empathetic thing. I don’t just mean I feel for these characters, but it’s a question of the pace and the rhythm: Can I take this into my body and not resist? If I have to read that paragraph over and over again, am I enjoying this process? And then of course there is the fact of the things literally in this book. Are these things I want to have in my head and be in the room that I’m sitting in? I think empathetic is a word I’m really excited by.

AK: I think that the body empathizes first. I think when you see someone, you can’t help but empathize with them. That’s part of why people react so strongly against people they don’t want to empathize with. They feel the feeling, and they reject it. I think it’s not that they see that person and see they have nothing in common with them; I think they don’t like being made to feel in common with them. The dumb example is if someone is biting their fingernails in the subway or something, it’s not that the sound annoys you or pushes you away, it’s that you’re thinking “I wouldn’t do that.” You’re imposing yourself on them. You’re pushing them away.

AM: I think that’s also true with the confessional thing. I think that a lot of what we hear about confessional writing, and a lot of the reason that standard is considered to be different is because women have a lot of experiences commonly that a lot of men don’t have. Dramatically more women are sexually assaulted than men, so it’s like this whole other thing from what men are experiencing. It becomes this othered thing because of how it’s defined by men in a patriarchal culture. I think that the whole failure of empathy is the failure to reject the patriarchy. I think that when we don’t do that we fail to have empathy in what we’re approaching as both writers and readers, not to steal your line.

EM: Confessional is such a weird word, as is the rise of it. It didn’t occur to me to look at who coined it when and in what fucking review and for what purpose. Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath in poetry. Or if you think about en plein air painting, it was a big weird thing when people suddenly decided not to write about the gods, or to sit out in the world and paint and use real things, use more peasant subject matter, and so on. It’s sort of like in poetry when people suddenly used life like yours. Whether you’re Robert Lowell or Sylvia Plath or whoever is doing it, it’s sort of disturbing the order of poetry and allowing the wrong thing in. Suddenly it’s almost like photography. I think with confessional . . . it’s so funny to think of such a private term erected, very phallically, to negate a whole practice that is actually the absolute opposite. It’s all about allowing. You make it be about denying.

PK: When I think back to confessional breakthroughs, I was just telling my students this, the two things that for me were confessional breakthroughs in my life were, one, telling a room full of strangers that I’d been sexually assaulted. That was a big one. I think a lot of people share that. The other one was telling people that I had a mustache growing up. That was somehow harder than talking about being raped. I just remember the first time I decided to blurt it, I think it was when my first novel came out, I just sort of said it, and I looked everybody in the eye in the audience like, “Okay, what do you want to say? Look at me now.” I didn’t even know what I was doing. I was trying to be like, “But I look good, right?” I don’t even know what I was trying to say. I was just like, “Why don’t we talk about the fact that some women have mustaches. It’s totally normal. Who cares?” [ Laughs ] But it’s sad to me that I went home feeling like I got a trophy for that because it was this confessional breakthrough for me. It felt like I released something, that I could go on. But it feels like we have these things which we’re not allowed to say.

EM: I remember a million years ago with a poem I suddenly just put in, “I’m not a bad looking woman, I suppose,” and it was so fucking radical to say that because I knew in that moment I would be reading out loud, that people were looking at me. They would be thinking about what I was thinking about myself, and how I look, and I am a little vain. I mean, I was like 30, and I just thought, I’m fucking saying that I think I’m kind of hot . And then of course it was wrong on so many levels, even for me personally, who I thought of myself as. But that is art and poetry: just make the wrong move and feel all the light kind of shift.

RO: And you’re still using the double negative. “I’m not a bad looking woman.”

MF: I want to ask a question about body and trauma, and I’m going to ask the question by quoting the wonderful Claudia Rankine from Citizen . “How to care for the injured body, the kind of body that can’t hold the content it is living? And where is the safest place when that place must be someplace other than in the body?”

EM: That’s a complicated one.

PK: That’s hard to disassociate from the context of Citizen , especially given even just this week’s news, that you can have a black man just reading a book or leaving a music appreciation class and get shot. To me, it’s almost impossible to divorce that quote specifically from race. Of course you can apply it to different types of identity. But then I think, that’s the dilemma of a lot of what we’re talking about in this panel, too, because the problem is that we’re so visual as people, right? I think that’s our dominant sense. I take that for granted because I learned everything from hearing mostly, and I’m not that visual. But we are as a culture, and so with that comes all sorts of wrongseeing and then hopefully not wrongdoing, but it’s sort of the basis of all sorts of sickening prejudices.

EM: I think you have to disable the text in some way to deal with difference and disability. I always think of Jonathan Franzen. I read The Corrections by accident. I lost something at the airport, and I kept going back to the lost and found, and they finally just let me all the way in the back room to the big gray chest and said, “Well, take whatever you want. There are a lot of notebooks and books here.” I saw The Corrections , and I thought, “Why not?” I thought it wasn’t bad. It was a good read, but what was really weird is when you got to the part where the father was having hallucinations, he couldn’t write that. I thought that’s so weird he can’t . . . he’s such a straight dude that he can’t imagine an altered state. I thought, any poet could write this scene. Anybody could do seeing shit, hallucinating. He couldn’t do that. I thought there was so much about ability of this. I don’t mean to take him out. He’s not a bad guy. But just as an example of something that was an alteration that couldn’t be written and that was somebody else’s cup of tea.