Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

Contributor Disclosures

Please read the Disclaimer at the end of this page.

INTRODUCTION

There are many methods available to help prevent pregnancy, with some of the most popular including condoms and birth control pills. Deciding which method is right can be tough because there are many issues to consider, including costs, future pregnancy plans, side effects, and others.

This article reviews all methods of birth control. More detailed discussions of hormonal, long-term, and barrier birth control methods are available separately. (See "Patient education: Long-acting methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" and "Patient education: Barrier and pericoital methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" and "Patient education: Hormonal methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" .)

EFFECTIVENESS OF BIRTH CONTROL

Birth control methods vary widely with respect to their effectiveness. Contraceptives can fail for a number of reasons, including incorrect use and failure of the medication, device, or method itself.

Certain birth control methods, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and the implant have the lowest risk of failure (pregnancy). This is because they are the easiest to use properly. You should consider these methods if you want the lowest chance of a mistake or failure, which could lead to pregnancy. (See "Patient education: Long-acting methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" .)

Overall, birth control methods that are designed for use at or near the time of sex (eg, condoms, diaphragm) are generally less effective than other birth control methods (eg, the IUD, the implant, and birth control pills).

If you forget to use birth control or if your method fails, there are options to reduce your risk of becoming pregnant for up to five days after you have sex. This is known as emergency contraception. (See "Patient education: Emergency contraception (Beyond the Basics)" .)

CHOOSING A BIRTH CONTROL METHOD

It can be difficult to decide which birth control method is best because of the wide variety of options available. The best method is one that you will use consistently, is acceptable to you and your partner, and does not cause bothersome side effects. Other factors to consider include:

● How effective is the method?

● Is it convenient? Do I have to remember to use it? If so, will I remember to use it?

● Do I have to use/take it every day?

● Is this method reversible? Can I get pregnant immediately after stopping it?

● Will this method cause me to bleed more or less? Will the bleeding I have while using the method be predictable or not predictable?

● Are there side effects or potential complications?

● Is this method affordable?

● Does this method protect against sexually transmitted diseases?

● Will it be difficult to discontinue this method if I choose to do so?

You should also consider how easy it is to get your birth control. For some forms, you need to see a doctor for a prescription. But there may be other options; for example, in some areas, you can get birth control pills online through services such as Nurx (www.nurx.com) or PRJKT RUBY (www.prjktruby.com). There are other online resources available as well.

No method of birth control is perfect. You must balance the advantages and disadvantages of each method and then choose the method that you will be able to use consistently and correctly.

INTRAUTERINE DEVICES (IUD)

IUDs are placed by a health care provider through the vagina and cervix, into the uterus. The currently available IUDs are safe and effective. These devices include:

● Copper-containing IUD – The Copper-containing IUD remains effective for at least 10 years, but can be removed at any time. The Copper IUD does not contain any hormones. Some people have heavier or longer bleeding during their period while using a copper IUD.

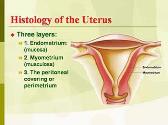

● Levonorgestrel-releasing IUD – The levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (which is available in different sizes and doses) releases a hormone, levonorgestrel, which thickens the cervical mucus and thins the endometrium (the lining of the uterus). This IUD also decreases the amount you bleed during your period and decreases pain associated with periods. These hormone-containing IUDs can be left in place for up to three to eight years (depending on the type of IUD chosen) but can be removed at any time. They are highly effective in preventing pregnancy. Some people stop having menstrual periods entirely; this effect is reversed when the IUD is removed.

BIRTH CONTROL IMPLANT

A single-rod progestin implant, Nexplanon, is available in the United States and elsewhere. It is inserted by a health care provider into your arm and is highly effective in preventing pregnancy. While it prevents pregnancy for at least 3 years as the hormone is slowly absorbed into the body, it can be removed at any time. It is effective within 7 days following insertion. Irregular bleeding is the most bothersome side effect. Fertility returns quickly after the rod is removed. (See "Patient education: Hormonal methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" .)

INJECTABLE BIRTH CONTROL

The only injectable method of birth control currently available in the United States is medroxyprogesterone acetate or DMPA (Depo-Provera). This is a progestin hormone, which is long-lasting. DMPA is injected deep into a muscle, such as the buttock or upper arm, once every three months. A version that is given under the skin is also available.

DMPA is very effective, when used consistently. A full discussion is available separately. (See "Patient education: Hormonal methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" .)

Side effects — The most common side effects of DMPA are irregular or prolonged vaginal bleeding and spotting, particularly during the first three to six months. Up to 50 percent of people completely stop having menstrual periods after using DMPA for one year. Although ovulation and menstrual periods generally return within six months of the last DMPA injection, it can take up to a year and a half for ovulation and cycles to return. For this reason, DMPA should be used only by people who do not wish to become pregnant in the next year or longer.

BIRTH CONTROL PILLS

Most birth control pills, also referred to as "the pill," contain a combination of two female hormones. A full discussion of birth control pills is available separately. (See "Patient education: Hormonal methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" .)

How well do they work? — When taken properly, birth control pills are effective. In general, if you miss one pill, you should take it as soon as possible. If you miss two or more pills, continue to take one pill per day and use a back-up method of birth control (eg, a condom) for seven days. If you miss two or more pills, you should also consider taking the morning after (emergency contraception) pill. (See "Patient education: Emergency contraception (Beyond the Basics)" .)

Side effects — Side effects of the pill include:

● Nausea, breast tenderness, bloating, and mood changes, which typically improve after two to three months.

● Irregular vaginal spotting or bleeding. This is particularly common during the first few months. Forgetting a pill can also cause irregular bleeding.

Progestin-only pills — Unlike traditional birth control pills, the progestin-only pill, also called the mini pill, does not contain estrogen. It does contain progestin, a hormone that is similar to the female hormone, progesterone. This type of pill is useful for people who cannot or should not take estrogen.

Progestin-only pills are as effective as combination pills if they are taken at the same time every day. However, the norethindrone progestin-only pill becomes less effective if you are more than three hours late in taking it, in which case, emergency contraceptives may be considered. This concern does not apply to a newer progestin-only pill that contains drospirenone.

SKIN PATCHES

Birth control skin patches contain two hormones, estrogen and progestin, similar to birth control pills, and may be preferred by some people because you do not have to take them every day. Although birth control skin patches are as effective as birth control pills in people who are categorized as "normal weight" based on their body mass index (BMI), they are less effective in those who fall into the overweight category.

One of the skin patch birth control methods available in the United States is sold under the brand name Xulane. A newer skin patch (brand name: Twirla) releases a lower amount of estrogen than Xulane. You wear the patch for one week on the upper arm, shoulder, upper back, or hip. After one week, you remove the old patch and apply a new patch; you repeat this for three weeks. During the fourth week, you do not wear a patch and withdrawal bleeding occurs during this week. Each new patch should be started on the same day of the week.

The risks and side effects of the patch are similar to those of a birth control pill, although there may be a slightly higher risk of developing a blood clot. Because obesity (having a BMI of 30 kg/m 2 or greater) alone is a risk factor for developing a blood clot, people who fall into this category should not use birth control skin patches.

VAGINAL RING

A flexible plastic vaginal ring contains estrogen and a progestin. You insert the ring in your vagina, where hormones are slowly absorbed into your body. You wear the ring inside the vagina for three weeks, followed by one week when you do not wear the ring; bleeding occurs during the fourth week. With one type of ring (sample brand names: NuvaRing, EluRyng), a new ring is placed each four weeks. With the other type (brand name: Annovera), the same ring is used for up to one year (13 28-day cycles). The vaginal ring prevents pregnancy similarly to the birth control pill, and the risks and side effects are similar. More information about the vaginal ring is available separately. (See "Patient education: Hormonal methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" .)

BARRIER METHODS

Barrier contraceptives prevent sperm from entering the uterus. Barrier contraceptives include the condom, diaphragm, and cervical cap. A full discussion of barrier methods of birth control is available separately. (See "Patient education: Barrier and pericoital methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics)" .)

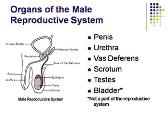

External condom — The external (formerly male) condom is a thin, flexible sheath placed over the penis to prevent semen from entering the partner's body. To be effective, it is important to carefully follow instructions when using condoms, and to use them every time you have sex. Many people who choose another method of birth control (eg, pills) also use condoms to decrease their risk of getting a sexually transmitted infection (STI). External condoms can also be used during anal sex to lower the risk of STIs.

Internal condom — The internal (formerly female) condom is worn inside the vagina to prevent semen from entering. It is a sheath made of polyurethane and is prelubricated. One ring-shaped part of this method remains inside the vagina while a second ring-shaped part remains outside the vagina.

Diaphragm/cervical cap — The diaphragm and cervical cap fit over the cervix, preventing sperm from entering the uterus. These devices are available in latex (the Prentif cap) or silicone rubber (FemCap) in multiple sizes, and require fitting by a clinician. These devices must be used with a spermicide and left in place for six to eight hours after sex. The diaphragm must be removed after this period. However, the cervical cap can remain in place for up to 24 hours.

Spermicide — Spermicides are chemical substances that destroy sperm. They are available in most pharmacies without a prescription. Spermicides are available in a variety of forms including gel, foam, cream, film, sponge, suppository, and tablet.

PERMANENT BIRTH CONTROL

This is a procedure that permanently prevents you from becoming pregnant or getting a partner pregnant. Tubal ligation and vasectomy are the two most common permanent birth control procedures. These procedures are permanent, and should only be considered after you discuss all available options with a health care provider and if you are certain you wish to permanently prevent pregnancy. (See "Patient education: Permanent birth control for women (Beyond the Basics)" and "Patient education: Vasectomy (Beyond the Basics)" .)

Tubal ligation — Tubal ligation is a procedure that surgically cuts, blocks, seals or removes the fallopian tubes to prevent pregnancy. The procedure is usually done in an operating room as a day surgery. Tubal ligation can be performed at the time of cesarean birth ("c-section"), or in the hospital following vaginal delivery. The procedure may be done at another time as well. This is discussed in more detail separately. (See "Patient education: Permanent birth control for women (Beyond the Basics)" .)

Vasectomy — Vasectomy is a procedure that cuts or blocks the vas deferens, the tubes that carry sperm from the testes. It is a safe, highly effective procedure that can be performed in a doctor's office under local anesthesia. Following vasectomy, you must use another method of birth control (eg, condoms) for approximately three months, until testing confirms that no sperm are present in the semen. This is discussed in more detail separately. (See "Patient education: Vasectomy (Beyond the Basics)" .)

OTHER BIRTH CONTROL METHODS

Some people cannot or choose not to use the birth control methods mentioned above due to religious, cultural, or personal reasons. Fertility-awareness based methods for preventing pregnancy are based upon the physiological changes during the menstrual cycle. These methods, also called "natural family planning," involve identifying the fertile days of the menstrual cycle using a combination of cycle length and physical manifestations of ovulation (change in cervical secretions, basal body temperature) and then avoiding vaginal sex or using barrier methods on those days. Smartphone apps are available that may help with tracking cycles.

The effectiveness of fertility-awareness methods in preventing pregnancy is lower than for the methods detailed above.

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION

Emergency contraception refers to the use of medication after unprotected sex to prevent pregnancy. Types of emergency contraception include the levonorgestrel or copper intrauterine device (IUD) or pills. You can use emergency contraception if you forget to take your birth control pill, if a condom breaks during sex, or if you have unprotected sex for other reasons (including victims of sexual assault). An IUD can be inserted for use as emergency contraception and is much more effective at preventing a pregnancy than pills. It is the best choice for emergency contraception, and you can continue to use it as your ongoing method of birth control. The other options are morning after pills, which may be hormonal (eg, Plan B One-Step, which is available without a prescription) or nonhormonal (eg, Ella, available only by prescription). Detailed information on emergency contraception is available separately. (See "Patient education: Emergency contraception (Beyond the Basics)" .)

WHERE TO GET MORE INFORMATION

Your health care provider is the best source of information for questions and concerns related to your medical problem. An excellent website to help you choose a method of birth control is www.bedsider.org .

This article will be updated as needed on our website ( www.uptodate.com/patients ). Related topics for patients, as well as selected articles written for health care professionals, are also available. Some of the most relevant are listed below.

Patient level information — UpToDate offers two types of patient education materials.

The Basics — The Basics patient education pieces answer the four or five key questions a patient might have about a given condition. These articles are best for patients who want a general overview and who prefer short, easy-to-read materials.

Patient education: Choosing birth control (The Basics) Patient education: Long-acting methods of birth control (The Basics) Patient education: Hormonal birth control (The Basics) Patient education: Permanent birth control for women (The Basics) Patient education: Barrier methods of birth control (The Basics) Patient education: Intrauterine devices (IUDs) (The Basics) Patient education: IUD insertion (The Basics) Patient education: IUD removal (The Basics)

Beyond the Basics — Beyond the Basics patient education pieces are longer, more sophisticated, and more detailed. These articles are best for patients who want in-depth information and are comfortable with some medical jargon.

Patient education: Long-acting methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics) Patient education: Barrier and pericoital methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics) Patient education: Hormonal methods of birth control (Beyond the Basics) Patient education: Emergency contraception (Beyond the Basics) Patient education: Permanent birth control for women (Beyond the Basics) Patient education: Vasectomy (Beyond the Basics) Patient education: Health and nutrition during breastfeeding (Beyond the Basics)

Professional level information — Professional level articles are designed to keep doctors and other health professionals up-to-date on the latest medical findings. These articles are thorough, long, and complex, and they contain multiple references to the research on which they are based. Professional level articles are best for people who are comfortable with a lot of medical terminology and who want to read the same materials their doctors are reading.

Intrauterine contraception: Candidates and device selection Contraception: Counseling for females with obesity Contraception: Counseling for women with inherited thrombophilias Contraception: Issues specific to adolescents Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA): Formulations, patient selection and drug administration Emergency contraception Internal (formerly female) condoms Fertility awareness-based methods of pregnancy prevention Hormonal contraception for menstrual suppression Pericoital (on demand) contraception: Diaphragm, cervical cap, spermicides, and sponge Hysteroscopic female permanent contraception Contraception: Etonogestrel implant External (formerly male) condoms Intrauterine contraception: Management of side effects and complications Evaluation and management of unscheduled bleeding in individuals using hormonal contraception Contraception: Counseling and selection Combined estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives: Patient selection, counseling, and use Contraception: Postpartum counseling and methods Contraception: Progestin-only pills (POPs) Combined estrogen-progestin contraception: Side effects and health concerns Female interval permanent contraception: Procedures Contraception: Transdermal contraceptive patches Vasectomy

The following organizations also provide reliable health information.

● National Library of Medicine

( www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/birthcontrol.html , available in Spanish)

● Planned Parenthood Federation of America

Phone: (212) 541-7800

( https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control )

● Bedsider – A site that provides information on birth control for people ages 18 to 29 years run by the nonprofit Power to Decide

( http://bedsider.org )

● Center for Young Women's Health – A site by Boston Children's Hospital that provides general and sexual health information for teens and young adults

( http://youngwomenshealth.org )

CDC Contraceptive Method Guidance: Slide Sets for Health Care Providers

Target audience.

Certified health education specialist, certified health educator, doctor of osteopathic medicine, epidemiologists, licensed practical and vocational nurses, medical doctors, medical assistants, medical students, nurse practitioners, nurse technicians, other health educators, pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, physician assistants, program managers, and registered nurses.

- U.S Medical Eligibility Criteria

- U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations

- Teen Pregnancy Prevention

U.S. MEDICAL ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR CONTRACEPTIVE USE, 2016

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION: The purpose of this activity is to enhance health care provider knowledge about the US MEC which is an evidence-based source of clinical guidance for the safe use of contraceptive methods by women and men with various characteristics and medical conditions. The goal is for the audience to apply what they learn from the training to their practice as they counsel women, men, and couples about contraceptive method choice. This activity is designed to provide latest evidenced-based information to healthcare providers that would address misconceptions regarding who can safely use contraception, which would remove unnecessary medical barriers, thereby improving access and quality of care in family planning. The activity will cover how the US MEC was developed, how to use the US MEC document, and show how to apply the US MEC in clinical settings. The recommendations presented in this activity remain up-to-date and based on the best available scientific evidence. The presentation and speaker notes can also be used or adapted to give presentations on the US MEC. This material is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated. Powerpoint presentation available in ppt or pdf formats.

OBJECTIVES:

At the conclusion of the session, the participant will be able to:

- Describe the U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016 (U.S. MEC)

- Identify intended use and target audience

- Explain how to use the U.S. MEC

- Discuss the guidance in specific situations, based on clinical scenarios

- Provide clinical preventive services to improve outcomes and quality of life

FACULTY/CREDENTIALS: Kathryn Curtis, PhD, Health Scientist, CDC Yokabed Ermias, MPH, ASPPH Fellow, CDC Tara Jatlaoui, MD, MPH, Medical Epidemiologist/Medical Officer, CDC Jamie Krashin, MD, MSCR, Guest Researcher/Assistant Research Professor, University of North Carolina School of Medicine H. Pamela Pagano, DrPH, MPH, CPH, Public Health Advisor, CDC Katherine Simmons, MD, MPH, Guest Researcher, CDC Naomi Tepper, MD, MPH, Medical Officer, CDC

Continuing education credits are no longer available for this activity.

Download Presentation

[PPT – 9 MB] | [PDF – 2 MB]

U.S. SELECTED PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CONTRACEPTIVE USE, 2016

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION: The purpose of this activity is to enhance health-care provider knowledge about the US SPR which provides evidence-based recommendations for common, yet controversial contraceptive management questions. The goal is for the audience to apply what they learn from the training to their practice as they counsel patients about contraceptive method use as well as management of certain concerns or problems with contraceptive use. The presentation and speaker notes can also be used or adapted to give presentations on the US MEC. This material is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated. Powerpoint presentation available in ppt or pdf formats.

- Describe the US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use or US SPR

- Identify the intended use of this document and the target audience for the guidance

- Describe how to use the US SPR guidance

- Discuss the guidance in specific clinical scenarios

FACULTY/CREDENTIALS: Kathryn Curtis, PhD, Health Scientist, CDC Yokabed Ermias, MPH, ASPPH Fellow, CDC Tara Jatlaoui, MD, MPH, Medical Officer, CDC Jamie Krashin, MD, MSCR, Guest Researcher, CDC H. Pamela Pagano, DrPH, MPH, CPH, Public Health Advisor, CDC Katherine Simmons, MD, MPH, Guest Researcher, CDC Naomi Tepper, MD, MPH, Medical Officer, CDC

[PPT – 4 MB] | [PDF – 2 MB]

TEEN PREGNANCY PREVENTION: APPLICATION OF CDC’S EVIDENCE-BASED CONTRACEPTION GUIDANCE

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION: The purpose of this activity is to provide an overview of the current trends in teen pregnancy as well as the efforts health care providers can make among teens to increase use of effective contraception according to the CDC’s Evidence-Based Contraception Guidance. This activity is designed to provide latest evidenced-based information to healthcare providers that would address misconceptions regarding who can safely use contraception, which would remove unnecessary medical barriers, thereby improving access and quality of care in family planning. This activity would also assist CDC in expanding our reach and communication activities with healthcare providers. The activity will describe the current trends in teen pregnancy, discuss the types of contraception that are safe for teens, describe the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016 (US MEC) and US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016 (US SPR) guidance, and show how to apply the guidance in clinical settings. The recommendations presented in this activity remain up-to-date and based on the best available scientific evidence. The presentation and speaker notes can also be used or adapted to give presentations on the US MEC. This material is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated. Powerpoint presentation available in ppt or pdf formats.

- Review the trends in teen pregnancy, sexual behavior and contraceptive use

- Describe current contraceptive methods available to teens

- Describe the current evidence-based recommendations about the safety and effectiveness of contraceptive methods for teens

- Discuss clinical preventive services to improve outcomes and quality of life

[PPT – 14 MB] | [PDF – 6 MB]

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Upload Ppt Presentation

- Upload Pdf Presentation

- Upload Infographics

- User Presentation

- Related Presentations

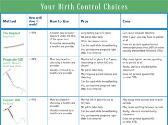

Your Birth Control Choices

By: neerajk Views: 624

Birth Control Methods-Frequently Asked Questions

By: neerajk Views: 647

Emergency Contraceptive Pills

By: neerajk Views: 473

IMAP Statement on emergency contraception

By: neerajk Views: 439

Birth Control Method Comparison Chart

By: neerajk Views: 479

The Human Body-The Reproductive System

By: medhelp Views: 511

Contraceptive Methods - Combined Hormonal Contraceptives

By: bharatind Views: 476

Physiotherapy Management of Female Sexual Dysfunction-FSD

By: KhushbuSG Views: 460

Antenatal Care

By: hsilmiz Views: 1559

ANATOMY OF THE FEMALE GENITAL SYSTEM

By: JenniferDwayne Views: 2400

- Occupation :

- Specialty :

HEALTH A TO Z

- Eye Disease

- Heart Attack

- Medications

- Children's Health

Contraception

Contraception (birth control) prevents pregnancy by interfering with the normal process of ovulation, fertilization, and implantation. There are different kinds of birth control that act at different points in the process.

Every month a woman's body begins the process that can potentially lead to pregnancy. An egg (ovum) matures, the mucus that is secreted by the cervix (a cylindrical-shaped organ at the lower end of the uterus) changes to be more inviting to sperm, and the lining of the uterus grows in preparation for receiving a fertilized egg. Any woman who wants to prevent pregnancy must use a reliable form of birth control. Birth control (contraception) is designed to interfere with the normal process and prevent the pregnancy that could result. There are different kinds of birth control that act at different points in the process, from ovulation through fertilization to implantation. Each method has its own side effects and risks. Some methods are more reliable than others.

Although there are many different types of birth control, they can be divided into a few groups based on how they work. These groups include:

- Hormonal methods: These use medications (hormones) to prevent ovulation. Hormonal methods include birth control pills ( oral contraceptives ), Depo Provera injections, and Norplant.

- Barrier methods: These methods work by preventing the sperm from getting to and fertilizing the egg. Barrier methods include male condom and female condom, diaphragm, and cervical cap. The condom is the only form of birth control that also protects against sexually transmitted diseases , including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

- Spermicides: These medications kill sperm on contact. Most spermicides contain nonoxynyl-9. Spermicides come in many different forms such as jelly, foam, tablets, and even a transparent film. All are placed in the vagina. Spermicides work best when they are used at the same time as a barrier method.

- Intrauterine devices (IUDs): These devices are inserted into the uterus, where they stay from one to ten years. An IUD prevents the fertilized egg from implanting in the lining of the uterus and may have other effects as well.

- Tubal ligation: This medical procedure is a permanent form of contraception for women. Each fallopian tube is either tied or burned closed. The sperm cannot reach the egg, and the egg cannot travel to the uterus.

- Vasectomy: This medical procedure is a the male form of sterilization and should be considered permanent. In vasectomy, the vas defrens, the tiny tubes that carry the sperm into the semen, are cut and tied off.

Unfortunately, there is no perfect form of birth control. Only abstinence (not having sexual intercourse) protects against unwanted pregnancy with 100 percent reliability. The failure rates, or the rates at which pregnancy occurs, for most forms of birth control are quite low. However, some forms of birth control are more difficult or inconvenient to use than others. In actual practice, the birth control methods that are more difficult or inconvenient have much higher failure rates, because they are not used faithfully.

Description

All forms of birth control have one feature in common. They are only effective if used faithfully. Birth control pills work only if taken every day; the diaphragm is effective only if used during every episode of sexual intercourse. The same is true for condoms and the cervical cap. Some methods are automatically working every day, no matter what. These methods include Depo Provera, Norplant, the IUD, and tubal sterilization.

There are many different ways to use birth control. They can be divided into several groups:

- By mouth (oral): Birth control pills must be taken by mouth every day.

- Injected: Depo Provera is a hormonal medication that is given by injection every three months.

- Implanted: Norplant is a long-acting hormonal form of birth control that is implanted under the skin of the upper arm.

- Vaginal: Spermicides and barrier methods work in the vagina.

- Intra-uterine: The IUD is inserted into the uterus.

- Surgical: Tubal sterilization is a form of surgery. A doctor must perform the procedure in a hospital or surgical clinic. Many women need general anesthesia.

The methods of birth control differ from each other regarding when they are used. Some methods of birth control must be used specifically at the time of sexual intercourse (condoms, diaphragm, cervical cap, spermicides). All other methods of birth control must be working all the time to provide protection (hormonal methods, IUDs, tubal sterilization).

Condoms and spermicides

Condoms are about 85 percent effective in preventing pregnancies. That means that out of 100 females whose partners use condoms, 15 will still become pregnant during the first year of use, according to the nonprofit advocacy group Planned Parenthood. Unwanted pregnancies usually occur because the condom is not attached or used properly or breaks during intercourse. More protection against pregnancy is possible if a spermicide is used along with a condom. Spermicide is a pharmaceutical substance used to kill sperm, especially in conjunction with a birth-control device such as a condom or diaphragm. Spermicides come in foam, cream, gel, suppository, or as a thin film. The most common spermicide is called nonoxynol-9, and many condoms come with it already applied as a lubricant. However, spermicides do not kill HIV or other sexually transmitted viruses and do not prevent the spread of HIV and other STDs. Also, nonoxynol-9 can irritate vaginal tissue and thus increase the risk of getting an STD. In anal sex, especially between two males, spermicides also can irritate the rectum, increasing the risk of getting HIV. Spermicides are specifically discouraged for use by gay or bisexual males for anal sex.

Latex condoms are also recommended over condoms made from other materials, especially lambskin, because they are thicker and stronger and have less risk of breakage during sex. Non-latex condoms do not prevent the spread of STDs, including HIV, and should not be used by gay or bisexual men or men who have HIV or other sexually transmitted diseases. Condoms are available over-the-counter, meaning they do not require a prescription, and there are no age restrictions on purchasing condoms. They are available at a variety of locations, including drug stores, convenience stores, supermarkets, and family planning clinics. They are also available for purchase on the Internet.

FEMALE CONDOM The female condom is a seven-inch polyurethane pouch that fits into the vagina. It collects semen before, during, and after ejaculation, keeping semen from entering the uterus through the cervix and thus protecting against pregnancy. In one year of use, it is 79 percent effective in preventing pregnancies. It also reduces the risk of many STDs, including HIV. There is a flexible ring at the closed end of the thin, soft pouch of the female condom. A slightly larger ring is at the open end. The ring at the closed end holds the condom in place in the vagina. The ring at the open end rests outside the vagina. When the condom is in place during sexual intercourse, there is no contact of the vagina and cervix with the skin of the penis or with secretions from the penis. It can be inserted up to eight hours before sex.

Precautions

There are risks associated with some forms of birth control. Some of the risks of each method are:

- Birth control pills: The hormone (estrogen) in birth control pills can increase the risk of heart attack in women over forty who smoke.

- Tubal sterilization: "Tying the tubes" is a surgical procedure and has all the risks of any other surgery, including the risks of anesthesia, infection, and bleeding.

- Condom: The most common problems associated with condoms are breakage during use and improper technique in using condoms. These can lead to pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, especially HIV.

Preparation

No specific preparation is needed before using contraception. However, a woman must be sure that she is not already pregnant before using a hormonal method or having an IUD placed.

Many methods of birth control have side effects. Knowing the side effects can help a woman to determine which method of birth control is right for her. There is no perfect form of birth control. Every method has a small failure rate and side effects. Some methods carry additional risks. However, every method of birth control has fewer risks than pregnancy. The risks include:

- Hormonal methods: The hormones in birth control pills, Depo Provera, and Norplant can cause changes in menstrual periods, changes in mood, weight gain, acne , and headaches. In addition, once a woman stops using Depo Provera or Norplant, she may go many months before she begins ovulating again.

- Barrier methods: A woman must insert the diaphragm in just the right way to be sure that it works properly. Some women get more urinary tract infections if they use a diaphragm because the diaphragm can press against the urethra, the tube that connects the bladder to the outside.

- Spermicides: Some women and men are allergic to spermicides or find them irritating to the skin.

- IUD: The device is a foreign object that stays inside the uterus, and the uterus tries to get it out. A woman may have heavier menstrual periods and more menstrual cramping with an IUD in place.

- Tubal ligation: Some women report increased menstrual discomfort after this surgery. It is not known if this side effect is related to the tubal ligation itself.

Parental concerns

Nearly 60 percent of sexually active girls under age 18 would discontinue at least some reproductive health services if their parents were informed that they were seeking contraceptive services, according to a study published in the August 14, 2002 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). If parental notification would cause the majority of minor girls to stop seeking reproductive health services or to use less effective methods of contraception, the rates of teen pregnancies and STD infections would substantially increase, Carol Ford of the Adolescent Medicine Program at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill and Abigail English of the Center for Adolescent Health & the Law state in an accompanying JAMA editorial. Although there is widespread consensus that communication between adolescents and their parents about sexual decision-making is important, there is no reason that confidential reproductive health care and efforts to improve communication between parents and their adolescent children cannot occur simultaneously, these authors suggest.

Parents of adolescents often are concerned that distribution of contraceptives leads to increased sexual activity. However, a study of 4,100 high school students published in the June 2003 issue of the American Journal of Public Health found that students who had access at school to condoms and instructions on their proper use were no more likely to have sexual intercourse than students at schools without condom distribution programs.

Fallopian tubes —The pair of narrow tubes leading from a woman's ovaries to the uterus. After an egg is released from the ovary during ovulation, fertilization (the union of sperm and egg) normally occurs in the fallopian tubes.

Fertilization —The joining of the sperm and the egg; conception.

Implantation —The process in which the fertilized egg embeds itself in the wall of the uterus.

Ovulation —The monthly process by which an ovarian follicle ruptures releasing a mature egg cell.

See also Condom .

Birth Control Pills: A Medical Dictionary, Bibliography, and Annotated Research Guide to Internet References. San Diego, CA: Icon Health Publications, 2003.

Peacock, Judith. Birth Control and Protection: Choices for Teens. Santa Rosa, CA: LifeMatters, 2000.

Whitney, Leon Fradley. Birth Control Today: A Practical Approach to Intelligent Family Planning. Temecula, CA: Textbook Publishers, 2003.

PERIODICALS

"Give Teens More Info to Bridge Information Gap." Contraceptive Technology Update 25(September 2004): 106–07.

Sullivan, Michele G. "Teens View Hormonal Contraception as Unsafe." Internal Medicine News 37 (July 15, 2004): 24.

"Teens Face Obstacles When Obtaining EC (Emergency Contraceptives)." Contraceptive Technology Update 25 (April 2004): 41–2.

Tucker, Miriam E. "Newer Contraceptives Give Teens More Options." OB GYN News 38 (August 1, 2003): 9.

ORGANIZATIONS

Advocates for Youth. 2000 M St. NW, Suite 750, Washington, DC 20036. Web site http://www.advocatesforyouth.org.

Planned Parenthood Federation of America Inc. 434 W. 33rd St., New York, NY 10001. Web site: http://www.plannedparenthood.org.

"Teens and Condoms." Avert.org , August 13, 2004. Available online at http://www.avert.org/teencondoms.htm (accessed November 23, 2004).

Amy B. Tuteur Ken R. Wells

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

- Biology Article

Contraception

Table of Contents

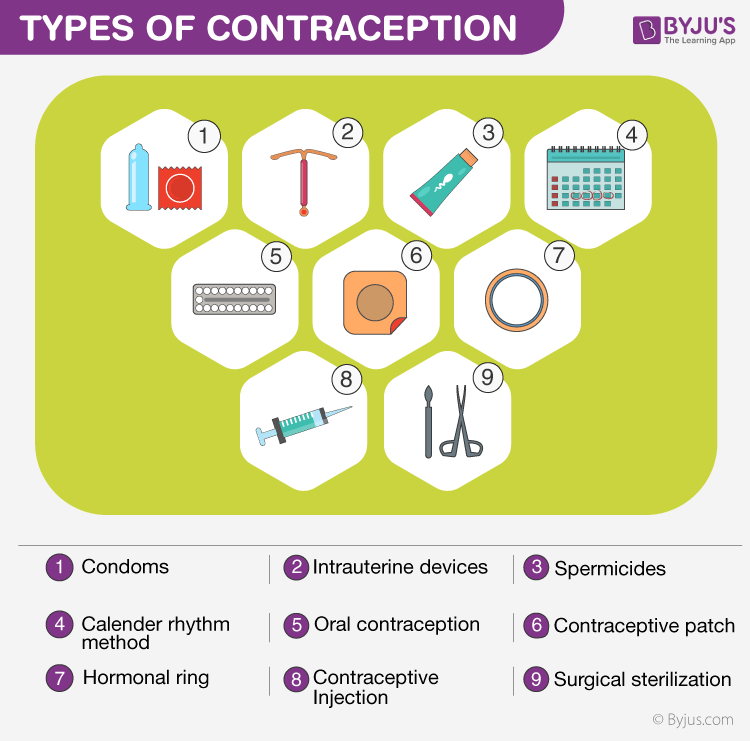

What is contraception, types of contraception.

Contraception is an artificial method or technique, mainly used to prevent pregnancy as a consequence of sexual intercourse. When a sperm reaches the ova in a woman, she may become pregnant. Contraception is a method that prevents this phenomenon by:

- Stopping egg production.

- Keeping the egg distinct from the sperm.

- By stopping the fertilized egg from attaching to the lining of the womb.

There are around fifteen to twenty different types or methods of contraception. Here, let us learn about the safest 3 methods of contraception.

Hormonal Contraception

It is a birth control method that acts on an endocrine system. It is composed of steroid hormones that comprise both oral and injectable methods. It is proved to be highly effective when taken on a prescribed schedule. The methods that are available currently can be used only by women. Some of the different methods of hormonal contraception include patches, IUD, implants, oral pills, injections and a vaginal ring.

There are two types of oral birth control pills. The progestogen: is only pills and the combined oral contraceptive pills. Both pills help to prevent fertilization. It is prevented mainly by thickening cervical mucus and inhibiting ovulation. If any of the pills are taken during pregnancy, there would be no miscarriages or cause any kind of birth defects.

Barrier contraceptives are devices that are used to prevent pregnancy by blocking sperm from entering the uterus. Some of them include female condoms, male condoms, contraceptive sponges with spermicide, diaphragms and cervical caps. Among them the most common birth control methods are condoms. They help in protecting against HIV and sexually transmitted diseases . Most modern condoms are made up of latex.

Contraceptive sponges with spermicide give the best barrier protection method. The spermicide kills most of the sperm entering the vagina. Then the remaining sperms are blocked from passing through the cervix to fertilize an egg.

Emergency Contraceptive

Emergency contraceptive is medications that primarily prevent fertilization or ovulation. There are lots of options namely mifepristone, ulipristal, levonorgestrel and high dosage control pills. Well, these methods do not affect the rates of sexually transmitted diseases, condom use, sexual risk-taking behaviour and pregnancy rates. All methods consist of minimum side effects.

Stay tuned with BYJU’S to know more in detail about contraception.

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click ‘Start Quiz’ to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the “Finish” button Check your score and answers at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU’S for all Biology related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Committee on Population. Contraception and Reproduction: Health Consequences for Women and Children in the Developing World. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1989.

Contraception and Reproduction: Health Consequences for Women and Children in the Developing World.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

7 Conclusions

Since World War II, there have been major improvements in the health of women and children in most developing countries. These improvements, however, have been unevenly distributed: they have been dramatic in some countries, moderate in others, and small in many countries, particularly the poorest countries of Africa and South Asia. Overall, the incidence of poor health and of infant, child, and maternal mortality remains unacceptably high throughout the developing world. Many developing countries have also experienced significant declines in fertility over the last 40 years. Other countries with the highest rates of infant, child, and maternal mortality also have high fertility rates. This report has examined the relationship between fertility and health during the course of this transition in fertility and mortality and has assessed the impact of changes in reproductive patterns on the health of women and children.

As discussed throughout the report, assessing the health effects of reproductive patterns and changes in them is not a straightforward task. First, as outlined in Chapter 2 , the relationships between fertility and health are very complex. For this evaluation, we have focused on what we term direct effects , a subset of the possible associations between reproductive patterns and women's and children's health. For example, we hypothesize that child spacing directly affects child mortality through mechanisms such as maternal depletion. By contrast, an indirect effect could occur if mothers who space their children more closely were less likely to be able to work for pay and thus improve the economic status of their family. Other indirect relationships between fertility and health may be as important as the direct effects.

Second, the data on which studies cited in this report are based are often seriously deficient. For example, data on maternal health and mortality are scarce, and research examining the relationship between birth spacing and maternal mortality in developing countries has yet to be carried out. Most studies of contraceptive risks and benefits are based on data from industrialized countries, and conclusions about the safety of contraceptive use in developing countries must in part be made by extrapolation. Information on gestational age, birth-weight, and maternal and infant nutritional status, which is necessary to sort out the association between birth spacing and child health, has been difficult to collect in developing countries. Furthermore, most data on which analyses of maternal and child health are based come from observational rather than experimental studies, a situation that complicates analytic designs, making it more difficult to draw inferences about causality.

Third, the limitations of the analytic strategies of many studies make firm conclusions difficult to draw. Many studies have not adequately considered alternative factors that may account for the observed relationships. Problems such as relevant, unmeasured influences and the joint operation of causal factors affect many studies of human behavior, but may be particularly troublesome in the associations discussed in this report because fertility and health are complex, interrelated processes. Few of the studies on which this report is based have attempted to deal with these issues in a comprehensive manner.

While the shortcomings of the evidence are clear and should be kept in mind, we believe that the available evidence is sufficient to draw important conclusions about how reproductive patterns affect women's and children's health.

- Reproductive Patterns and Women's Health: Risks for Individual Women

Maternal mortality has declined significantly in this century in the developed world. Some developing countries have also witnessed declines in maternal mortality because of improvements in prenatal care, better midwifery, widespread use of aseptic delivery procedures, the introduction of antibiotics, improvements in the provision of health services, and overall advances in women's social position and standard of living. These experiences provide unequivocal evidence that mortality and morbidity due to reproductive causes can be reduced. What role can changes in reproductive patterns play in this process?

It is clear that reductions in the number of pregnancies women have in their lifetimes and in the incidence of high-risk pregnancies will substantially reduce the risk of maternal mortality and morbidity for individual women. Furthermore, the positive effects of lower fertility and reductions in the frequency of high-risk pregnancies on women's health are likely to be greatest in populations in which fertility rates are high, health facilities are poor or unavailable, and the incidence of reproductive morbidity is high.

Each time they become pregnant, women face a risk of morbidity and mortality, and these risks are higher in societies in which health conditions are poor. A reduction in the number of times a woman becomes pregnant during her life will reduce her lifetime risk of dying from reproductive causes. If, in addition to reducing the total number of pregnancies she has, a woman uses contraception to avoid high-risk pregnancies, the beneficial effect will be reinforced. Pregnancies that are particularly high risks for women include those that occur when a woman has a previous gynecological or obstetrical illness or problem, such as postpartum hemorrhage, or has a preexisting health problem, such as diabetes, while she is pregnant.

In addition, pregnancies to very young and older women, and first-and higher-order pregnancies (fifth and higher-order) appear to be riskier than others. While first births cannot, of course, be avoided if a woman chooses to have children, the risks appear to be attenuated if the first birth is delayed beyond the high-risk early teenage years.

Risks Associated With Induced Abortion

Unsafe induced abortion is an important cause of reproductive morbidity and mortality. As noted in Chapter 3 , unsafe induced abortion is a primary cause of maternal mortality. Family planning services have the potential to reduce abortion-related health problems by reducing unwanted pregnancies. Countries in which safe abortion is not available have the greatest obligation to provide all needed contraceptive and medical services to reduce unintended pregnancy and to treat the complications of unsafe abortion.

Contraceptive Risks and Benefits

According to a United Nations (1989) estimate, over 400 million women in developing countries are using some form of contraception. This diffusion of modern contraceptives has facilitated widespread regulation of fertility. The most important conclusion to be drawn from the extensive literature examining the noncontraceptive health risks and benefits of contraception is that risks associated with contraceptive use are significantly less than the risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth. This conclusion is especially true in many countries in the developing world where childbirth and pregnancy risks are high.

Although contraception in general is safer than pregnancy, it is nonetheless important to consider contraceptive risks and benefits in relation to the characteristics of different women. For example, to recall Chapter 4 , decisions to use oral contraceptives should consider factors such as age and whether a woman smokes cigarettes, and decisions to use an intrauterine device should consider a woman's pattern of sexual activity. Both contraceptive needs and the risk-benefit profiles of women change over the course of their reproductive lives. Information about risks and benefits, including information on contraceptive efficacy, at different life-cycle stages is necessary for informed decision making and for safer, more effective contraceptive practice.

An ongoing program to evaluate the health risks and benefits of contraception use is needed in both developing and developed countries. Such research will help scientists to understand the effects of specific methods under different conditions of use. Such studies would be especially useful in the case of oral contraceptives and other steroid or hormonal methods because the evolution of methods (e.g., changes in dosages in oral contraceptives) and long latency period of potential health problems (e.g., cancer) means that potential risks and benefits can be understood only through long-term studies. Ongoing evaluation of oral contraceptives and other methods is also needed in both developing and developed countries to provide the depth of knowledge necessary for the refinement and improvement of contraceptive methods and guidelines for their use.

- Reproductive Risks and Children's Health: Risks for Individual Children

Parents can maximize the chances of survival and good health for each of their children by lengthening the intervals between births, avoiding pregnancies at very young and older ages, and avoiding higher-parity pregnancies. Firstborn children also appear to have higher risks of morbidity and mortality. However, parents obviously cannot increase their children's chances of survival by avoiding having a first birth, although they may be able to improve their firstborn's survival chances by delaying the birth until their early twenties and having their second child more than two years after their first.

The association between birth spacing and child survival has been observed in developing countries, in high-mortality historical populations, and in contemporary industrialized countries. In this wide range of historical and contemporary populations, children born after short birth intervals have higher mortality than children born after longer intervals. Furthermore, the relationship remains important in studies that hold some of the potentially confounding factors constant. However, when potentially confounding factors are held constant, it appears that the detrimental effects of older maternal age and higher birth order on children's health are less important than previously thought.

Our understanding of the mechanisms affecting the observed associations between health and birth spacing as well as for maternal age, birth order, and family size remains incomplete. While a relationship between close birth spacing and higher infant and child mortality is widely observed, we do not yet know whether this relationship is due to birthweight or gestational age or some other factor. In contemporary developing countries, families who use contraception to space their births may also be more likely to use health services when their children are ill. Until further research has been completed, caution is necessary when drawing conclusions about the amount of improvement in children's survival that may result from changes in reproductive patterns. Nonetheless, given the breadth of the available evidence—as well as the likelihood that there are important indirect benefits of lower fertility on family health and well-being—we believe that parents who wish to improve their children's chances of survival should avoid short birth intervals, births at very young and at older ages, and higher-order births. The effects of this strategy are likely to be greater where living standards are poor, the incidence of disease is high, and parents do not have access to adequate health care.

Given the strength of the observed relationship between short birth intervals and infant and child health, policy makers, health and family planning program managers, and concerned citizens in developing countries can improve children's health by encouraging both breastfeeding and contraceptive use in order to lengthen birth intervals. With this approach the beneficial effects of breastfeeding for children's health are reinforced by the contraceptive effect of breastfeeding in delaying the next birth. In many developing countries, breastfeeding has declined during the course of development, and many mothers apparently decide to discontinue breastfeeding when they adopt contraception. It also appears that some family planning programs may discourage breastfeeding for women adopting contraception out of concern about the effects of hormonal contraception on breast milk. While more research is needed on the relationship between contraceptive use and breastfeeding and, in particular, on the extent to which women substitute one for the other, programs designed to encourage both breastfeeding and contraceptive use for birth spacing are likely to have important benefits for the health of children.

Because of the clear relationship between a reduction in the number of pregnancies a woman has and reduction in her lifetime risk of dying from reproductive causes, another potential health benefit of lower fertility for children is a reduced risk of losing their mother to illness or death. Documentation of the effects of maternal mortality on the health and well-being of children in developing countries is mostly anecdotal. However, since women remain primary caretakers for children in most countries, maternal death or illness almost certainly has severe consequences for the health and survival of young children.

- Aggregate-Level Effects

Reducing fertility and avoiding high-risk pregnancies are important strategies to reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity for individual women and children. Determining the implication of widespread individual changes in reproductive patterns on aggregate measures of health, such as the infant mortality rate, however, is complex and has been the subject of considerable debate (see Trussell and Pebley, 1984; Winikoff, 1983; Bongaarts, 1988; Trussell, 1988; Palloni, 1988).

There are at least two reasons to believe that a reduction in fertility will bring about an unambiguous decline in mortality rates and an improvement in the health of a population. First, maternal mortality rates, which measure the frequency of death due to reproductive causes, are likely to decline as a consequence of a fertility decline, because women will be exposed to risks associated with pregnancy less often. In other words, if fertility rates decline, there will be fewer pregnancies, and thus fewer women exposed to the risk of dying from reproductive causes each year.

Second, at a given level of funding for health care, lower fertility rates are likely to mean better health care for each pregnant woman and child because more resources per capita will be available. As a consequence of better health care, maternal and child morbidity and mortality would be expected to decline.

Measuring the impact of change in the level and pattern of childbearing for a society is complicated by the fact that mortality rates reflect in part the distribution of pregnancies and births among high-risk and low-risk groups in the population. A change in reproductive patterns is likely to change this distribution of pregnancies and births in several ways at the same time. The end result, in some populations, may be that there is relatively little change in mortality rates as a direct consequence of change in reproductive patterns, even though the rates for specific groups may decline. Insofar as these changing patterns of reproduction are associated with lower levels of fertility, they will also be associated with lower numbers of infant deaths.

As shown in Chapter 6 , one of the major effects of a fertility decline is to reduce the proportion of births to high-parity women in a population and, at the same time, to increase the proportion of first births. Currently available evidence indicates that infant mortality rates are higher for first births as well as for higher-order births. Since both first births and higher-order births have elevated risks of mortality, the effect of a fertility decline, if everything else remains the same, may be small or neutral. Because the available data indicate maternal mortality ratios are higher for first pregnancies as well as for higher-order pregnancies, this argument also applies to maternal mortality ratios, which measure the average risk of death for women associated with each pregnancy in a population.

Another type of distributional change may mean that, holding everything else constant, mortality rates might actually increase somewhat during the early part of a fertility decline. The reason is that it is often women who are at relatively low risk for infant, child, or maternal mortality who first adopt contraception as a means of reducing fertility. Thus, a larger proportion of pregnancies and births would occur to women who were at higher risk in the initial period of the fertility decline than had been the case before the decline began.

The potential scope for improving health at the societal level through changes in reproductive patterns also depends on the distribution of pregnancies and births among high-and low-risk groups in a society. In South Asia and some African countries, for example, many births occur to very young women. There is, therefore, considerable potential for improving the health of women and children by delaying the onset of childbearing. The potential for improving child health through changes in patterns of birth spacing patterns is likely to be larger in Latin American countries than in other areas of the developing world because of the high proportion of short birth intervals. The current scope for improvements in child health through birth spacing is considerably more limited in South Asian and sub-Saharan African countries because short birth intervals are relatively rare. A central concern for policy makers in South Asian and sub-Saharan African countries is that birth intervals may become shorter during the course of modernization because of the decline in breastfeeding and postpartum abstinence. If such changes occur, the effect may be to slow the pace of infant and child mortality decline relative to the pace that would be achieved if longer birth spacing had been maintained.

In reality, fertility declines and changes in reproductive patterns do not occur in isolation. They are accompanied by (and brought about by) a variety of other important social and economic changes as well as by governmental policy initiatives. These changes themselves are likely to have major effects on health and mortality independent of their relation to fertility, and declines in fertility may in part be responsive to these improvements in health and mortality conditions. In fact, most countries have experienced fairly continuous mortality declines while undergoing fertility transitions, and interruptions in the mortality decline have generally been due to natural disasters, economic calamity, or major epidemics.

- Indirect Effects of Reproductive Change on the Health of Women and Children

Lower fertility and changing reproductive patterns may also have important indirect effects on the health of women and children. These effects include shifting attitudes away from fatalism, making it feasible for women to develop roles independent of motherhood, and increasing the resources available for each member of the family because of smaller family sizes. These indirect effects are difficult to document, but in the long run they may be equally or more significant than the direct effects of changing reproductive patterns.

Considerable work remains before we have a clear understanding of the indirect effects of changing reproductive patterns on maternal and child health. There is particular need to understand how family structure and the process of family decision making in developing countries adjusts to changing economic, social, and demographic situations. Seemingly minor changes in one element of reproductive patterns may have long-term consequences that may improve the health and well-being of all family members. For example, Ryder (1976) argues that delaying the age at which women in developing countries have their first birth is of particular importance to these societies because it allows time for women to participate in other, nonfamilial social roles, such as that of a student or worker.

Exposure to modern medical services may also have significant long-term consequences on the attitudes of women and children beyond the immediate effects of treatment. For example, women may be more likely to continue treatment if their first exposure to modern medicine produces positive results. Increasing our understanding of how attitudes and family health care are influenced by exposure to modern health care, including family planning services, is crucial to policy makers.

- Family Planning and the Health of Women and Children

One aim of this report is to evaluate the potential for family planning to bring about additional improvements in the health of women and children. At several points, we have emphasized the complexity of the relationships involved, but the implications of the available evidence are clear. Maternal, infant, and child mortality and morbidity remain important problems throughout the developing world and are clearly related to reproductive patterns. Although there is a great deal of variation in the effect that reproduction has on the health of individuals, families, and countries, the reduction of high-risk pregnancies typically would have a positive impact on the health of mothers and children throughout the developing world.

Contraceptive use and controlled fertility are safer than unregulated childbearing. Unsafe abortions are a significant cause of maternal mortality in many developing countries, a finding that must be considered by countries debating the merits of making safe abortions available. Greater control of reproduction would improve maternal and child health by reducing births, especially high-parity births, and by reducing closely spaced pregnancies. Easy access to contraceptive services should be encouraged, particularly in conjunction with efforts to increase prenatal care, to improve breastfeeding practices, and to advance other health services. Efforts to increase education, especially female literacy, and to improve nutritional status may act synergistically with family planning and health services to improve maternal and child health.

It should also be clear from this report that additional research is needed in many areas before we understand adequately the causal linkages between reproduction and women's and children's health. While this research is being carded out, however, government officials, policy makers, public health practitioners, and individuals everywhere must make decisions about the best ways to improve the health of individuals and families. Family planning activities have an important potential role as a component of health programs directed toward improving the health of women and children.

- Cite this Page National Research Council (US) Committee on Population. Contraception and Reproduction: Health Consequences for Women and Children in the Developing World. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1989. 7, Conclusions.

- PDF version of this title (1.1M)

In this Page

Recent activity.

- Conclusions - Contraception and Reproduction Conclusions - Contraception and Reproduction

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Courses on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research 2021 Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Weekly schedule

- Participants

- Course files

- Assignments

- Course evaluation report

- General information

- Application form

- Course guide

- Assignment guide

- Web statistics

- End of course meeting

Contraceptive Methods

June 21, 2021 - Geneva

Please provide the following information for your country.

- Fertility rate

- Number of unintended pregnancies

- Contraceptive prevalence rate for (a) all methods and (b) modern methods of contraception

- Unmet need for modern methods of contraception

- Demand satisfied with a modern contraceptive method

- Which contraceptive methods are available?

- Which contraceptive methods are commonly used (a) by all women (b) married women (c) unmarried women, (d) adolescents (e) postpartum women and (f) women with HIV?

Please indicate the source(s) of your information. Answers without a reference will not be considered valid.

Sources of information

You can find answers to these questions in your country’s Population surveys such as the Demographic Health survey (DHS), Performance Monitoring and Accountability 2020 (PMA2020) Surveys, Reproductive Health Survey (RHS), Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and other nationally representative surveys or from websites of international organizations like the United Nations Population Fund ( https://www.unfpa.org/ ) and the United Nations Development Programme ( https://www.undp.org/ ).

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Typical use failure rate: 0.1%. 1. Injection or "shot" —Women get shots of the hormone progestin in the buttocks or arm every three months from their doctor. Typical use failure rate: 4%. 1. Combined oral contraceptives —Also called "the pill," combined oral contraceptives contain the hormones estrogen and progestin. It is ...

Contraception Relationships and Sex Education lesson plan - for use with Contraception Choices website www.contraceptionchoices.org This lesson plan has been designed as a 1 hour class for use with students to provide detailed information about contraceptive methods and practical considerations when considering starting or switching contraception.

Key facts. Among the 1.9 billion women of reproductive age group (15-49 years) worldwide in 2021, 1.1 billion have a need for family planning; of these, 874 million are using modern contraceptive methods, and 164 million have an unmet need for contraception (1).; The proportion of the need for family planning satisfied by modern methods, Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) indicator 3.7.1 ...

3 It is a birth control method used in preventing pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD's) among others. 4,5 The major form of contraception is the barrier methods of which the ...

The only injectable method of birth control currently available in the United States is medroxyprogesterone acetate or DMPA (Depo-Provera). This is a progestin hormone, which is long-lasting. DMPA is injected deep into a muscle, such as the buttock or upper arm, once every three months.

The clear, up-to-date information and advice in the handbook enables family planning providers to meet clients' needs, inform their choices, and support their use of contraception across different contexts and settings. The current edition launched in 2022 is available in English, French, Spanish and Russian.

Methods: We conducted a cluster randomized controlled trial of contraceptive counseling with My Birth Control compared with usual care at 4 clinics serving low-income, racially/ethnically diverse populations in the San Francisco Bay Area. Participating providers (nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, physician assistants, and health educators) were randomized to the tool or to usual care.

pregnancy protection. Therefore, "dual method use"—using a condom and another effective contraceptive method at the same time—provides strong protection against both pregnancy and STIs, compared with using only one method. However, the proportion of high school students who report dual method use is low: less than 10 percent of those

Forty-six percent of women had not used a contraceptive method in the month they conceived, mainly because of perceived low risk of pregnancy and concerns about contraception (cited by 33% and 32% ...

U.S. MEDICAL ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR CONTRACEPTIVE USE, 2016. PROGRAM DESCRIPTION: The purpose of this activity is to enhance health care provider knowledge about the US MEC which is an evidence-based source of clinical guidance for the safe use of contraceptive methods by women and men with various characteristics and medical conditions. The goal is for the audience to apply what they learn ...

May 20, 2015 • Download as PPT, PDF •. 474 likes • 269,946 views. Dr Nilesh Kate. CONTRACEPTIVE METHODS. Health & Medicine. 1 of 50. Download now. CONTRACEPTIVE METHODS. CONTRACEPTIVE METHODS - Download as a PDF or view online for free.

Contraceptive methods Part 2 - Progestogen-only contraceptives. Contraceptive methods Part 3. Contraceptive methods Part 4. B. Assignment. Complete and submit your answers to the multiple-choice questions (MCQs) for the module. You will receive the link to the MCQs by email. Complete and submit the short paperwork assignment.

Oral Contraceptive Pills. The combined pill consists of two hormones: estrogen and progesterone. This is to be taken everyday orally by the woman. The pill works by preventing the release of the egg, thickening of cervical mucus and by altering tubal motility. It is to be prescribed after a medical check-up.

Contraceptive Methods Chart 5 points 3 points 1 point Provides information on all areas of chart where appropriate; information is correct and relevant to contraceptive method Information placed on the contraceptive methods chart is accurate but some sections are incomplete.

Improving birth control use with programs based on theory. ... Programs addressed the use of one or more birth control methods. The reports showed that the theory or model was part of the program design. ... and the number of clusters ranged from 20 to 35. The effective sample sizes would be smaller due to the assignment of groups rather than ...

Estimated proportions of contraceptive users among women of reproductive age (15-49 years) using permanent or long-acting modern methods, short-acting modern methods and traditional methods in 2019, by country and region - I Contraceptive use by method 20 Contraceptive Use by Method 2019: Data Booklet (ST/ESA/SER.A/435). United Nations; 2019.

Birth control (contraception) is designed to interfere with the normal process and prevent the pregnancy that could result. There are different kinds of birth control that act at different points in the process, from ovulation through fertilization to implantation. Each method has its own side effects and risks.

Some of the different methods of hormonal contraception include patches, IUD, implants, oral pills, injections and a vaginal ring. There are two types of oral birth control pills. The progestogen: is only pills and the combined oral contraceptive pills. Both pills help to prevent fertilization. It is prevented mainly by thickening cervical ...

Assignment. type of birth control it is effective how it works not engaging in any sexual activity sexual abstinence considered as natural contraception ... Theyare about 85% effective — that means about 15 out of 100 people who use condoms as their only birth control method will get. Condoms are small, thin pouches made of latex , plastic ...

Conclusions. Since World War II, there have been major improvements in the health of women and children in most developing countries. These improvements, however, have been unevenly distributed: they have been dramatic in some countries, moderate in others, and small in many countries, particularly the poorest countries of Africa and South Asia.

Contraceptive Methods. Module 2. Contraceptive Methods. Assignment. June 21, 2021 - Geneva. Please provide the following information for your country. Fertility rate; Number of unintended pregnancies; Contraceptive prevalence rate for (a) all methods and (b) modern methods of contraception ; Unmet need for modern methods of contraception

Laboratory 20 Assignment - Contraceptive Method In this assignment you will explore some details concerning Contracepti assignment is in no way an endorsement of any specific method. nor is exhaustive analysis of all methods, nor is it a suggestion to use contraception to access the following website to complete this assignment: www.plannedpa there, click on the Learn Tab, then Birth Control.

Assignment On Contraceptive Method | MSN | Bsc nursing 2nd year #assignment #contraceptive #nursingassignment on contraceptive methodassignment on contracept...