- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Tuskegee Experiment: The Infamous Syphilis Study

By: Elizabeth Nix

Updated: June 13, 2023 | Original: May 16, 2017

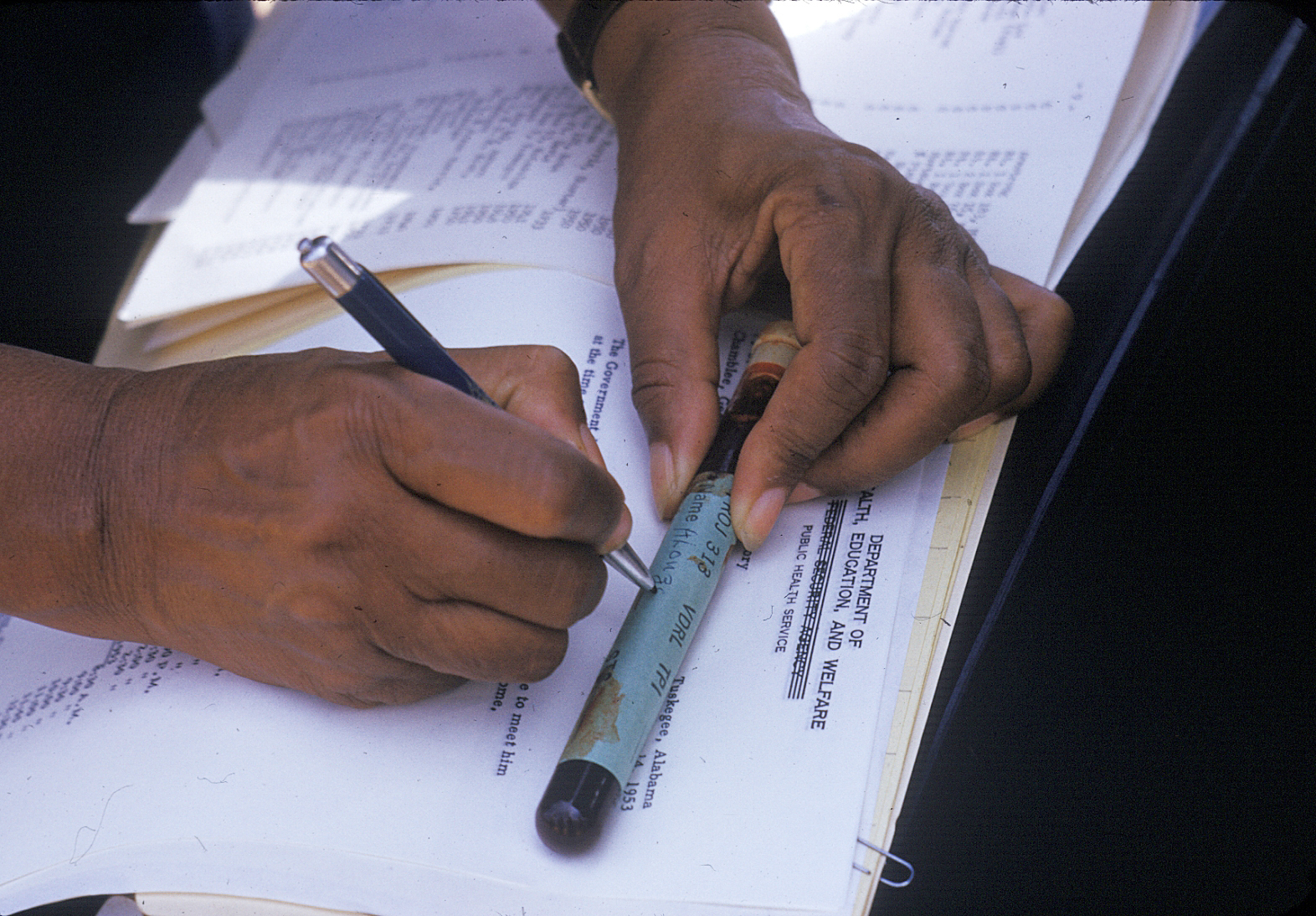

The Tuskegee experiment began in 1932, at a time when there was no known cure for syphilis, a contagious venereal disease. After being recruited by the promise of free medical care, 600 African American men in Macon County, Alabama were enrolled in the project, which aimed to study the full progression of the disease.

The participants were primarily sharecroppers, and many had never before visited a doctor. Doctors from the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS), which was running the study, informed the participants—399 men with latent syphilis and a control group of 201 others who were free of the disease—they were being treated for bad blood, a term commonly used in the area at the time to refer to a variety of ailments.

The men were monitored by health workers but only given placebos such as aspirin and mineral supplements, despite the fact that penicillin became the recommended treatment for syphilis in 1947, some 15 years into the study. PHS researchers convinced local physicians in Macon County not to treat the participants, and instead, research was done at the Tuskegee Institute. (Now called Tuskegee University, the school was founded in 1881 with Booker T. Washington as its first teacher.)

In order to track the disease’s full progression, researchers provided no effective care as the men died, went blind or insane or experienced other severe health problems due to their untreated syphilis.

In the mid-1960s, a PHS venereal disease investigator in San Francisco named Peter Buxton found out about the Tuskegee study and expressed his concerns to his superiors that it was unethical. In response, PHS officials formed a committee to review the study but ultimately opted to continue it—with the goal of tracking the participants until all had died, autopsies were performed and the project data could be analyzed.

Buxton then leaked the story to a reporter friend, who passed it on to a fellow reporter, Jean Heller of the Associated Press. Heller broke the story in July 1972, prompting public outrage and forcing the study to finally shut down.

By that time, 28 participants had perished from syphilis, 100 more had passed away from related complications, at least 40 spouses had been diagnosed with it and the disease had been passed to 19 children at birth.

In 1973, Congress held hearings on the Tuskegee experiments, and the following year the study’s surviving participants, along with the heirs of those who died, received a $10 million out-of-court settlement. Additionally, new guidelines were issued to protect human subjects in U.S. government-funded research projects.

As a result of the Tuskegee experiment, many African Americans developed a lingering, deep mistrust of public health officials and vaccines. In part to foster racial healing, President Bill Clinton issued a 1997 apology, stating, “The United States government did something that was wrong—deeply, profoundly, morally wrong… It is not only in remembering that shameful past that we can make amends and repair our nation, but it is in remembering that past that we can build a better present and a better future.”

During his apology, Clinton announced plans for the establishment of Tuskegee University’s National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care .

The final study participant passed away in 2004.

Tuskegee wasn't the first unethical syphilis study. In 2010, then- President Barack Obama and other federal officials apologized for another U.S.-sponsored experiment, conducted decades earlier in Guatemala. In that study, from 1946 to 1948, nearly 700 men and women—prisoners, soldiers and mental patients—were intentionally infected with syphilis (hundreds more people were exposed to other sexually transmitted diseases as part of the study) without their knowledge or consent.

The purpose of the study was to determine whether penicillin could prevent, not just cure, syphilis infection. Some of those who became infected never received medical treatment. The results of the study, which took place with the cooperation of Guatemalan government officials, were never published. The American public health researcher in charge of the project, Dr. John Cutler, went on to become a lead researcher in the Tuskegee experiments.

Following Cutler’s death in 2003, historian Susan Reverby uncovered the records of the Guatemala experiments while doing research related to the Tuskegee study. She shared her findings with U.S. government officials in 2010. Soon afterward, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius issued an apology for the STD study and President Obama called the Guatemalan president to apologize for the experiments.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Site Search

- How to Search

- Advisory Group

- Editorial Board

- OEC Fellows

- History and Funding

- Using OEC Materials

- Collections

- Research Ethics Resources

- Ethics Projects

- Communities of Practice

- Get Involved

- Submit Content

- Open Access Membership

- Become a Partner

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study

This is one of six cases from Michael Pritchard and Theodore Golding's instructor guide, " Ethics in the Science Classroom ." that provide background and some discussion guidelines around the historical Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

Categories Illustrated by This Case: Issues related to experimentation on human subjects.

1. Introduction

Although experimentation on human subjects has long been understood to be fraught with serious ethical concerns, little was done to develop national and international guidelines and regulations with regard to such research until the end of World War II. Populations that were frequently victimized by involuntary or coerced participation in potentially dangerous experiments included prisoners and insane asylum inmates. Due to popular recognition of the need to test new medical treatments, defenders of the rights of such powerless individuals found little political interest in outlawing these practices. However, the atrocities committed by Nazi doctors in the name of medical experimentation, as revealed during the Nuremberg war crimes trials, raised international consciousness about the need for an acceptable code for medical research.

The result was the promulgation in 1947 of the Nuremberg Code. This document was drafted by an international panel of experts on medical research, human rights, and ethics. It focused on the requirement for voluntary consent of the human subject and the weighing of the anticipated potential humanitarian benefits of a proposed experiment against the risks to the participant. The Code served as the initial model for those few public and private research and professional organizations that voluntary chose to adopt guidelines or rules for research involving human subjects.

In the ensuing years occasional media publicity called attention to continuing questionable biomedical and behavioral research practices. In 1972 the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, described in the case study below, became a cause celebre due to the thorough and dramatic Associate Press story written by reporter Jean Heller. Congressional hearings took place in 1973 and the following year Congress passed legislation creating the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Commissioners included prominent experts and scholars in the fields of medicine, psychology, civil rights, the law, ethics and religion. In 1979 they published Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, which is commonly referred to as "The Belmont Report." This document presents a well-developed ethical framework for the exploration of the issues associated with the use of human beings as the subjects of research. More comprehensive than the Nuremberg Code, it defined the boundary between accepted therapeutic practice and experimental research, and proposed the following three basic principles to guide in the evaluation of the ethics of research involving human subjects.

- Respect for Persons - This principle incorporates the convictions that individual research subjects should be treated as autonomous agents, and that persons with diminished autonomy (such as prisoners or inmates of mental institutions) are entitled to protection.

- Beneficence - Research involving human subjects should do no intentional harm, while maximizing possible benefits and minimizing possible harms, both to the individuals involved and to society at large.

- Justice - Attention needs to be paid to the equitable distribution within human society of benefits and burdens of research involving human subjects. In particular, those participants chosen for such research should not be inequitably selected from groups unlikely to benefit from the work.

The Belmont report has greatly influenced the codes and regulations regarding human subjects research that have since been established in the United States by federal and many state governments, universities, professional organizations and by private research institutions, as well as similar codes and regulations elsewhere in the world.

2. Background

Syphilis was a widespread but poorly-understood disease until shortly after the turn of the century. Two of the principal steps forward were the isolation of the bacterium associated with syphilis in 1905, and shortly thereafter, the development of the Wasserman reaction to detect the presence of syphilis through a blood test.

Still, much about the disease and its progress remained unknown. Due to this lack of understanding many cases were incorrectly diagnosed as syphilis, while in other cases patients who would now be recognized as victims of the disease were missed. As the etiology of the disease was better understood, it became increasingly urgent to understand its long-term effects. The early treatments that predated the discovery of penicillin involving the use of such poisons as arsenic and mercury were dangerous, and sometimes even fatal. Thus, it was vital to learn about the likelihood that the disease itself would result in serious physical or mental disability in order to make sure that the potential benefits of treatment exceeded the risks.

One long-term study had been carried out in Oslo, Norway. This had been a retrospective study, going over the past case histories of syphilis victims then undergoing treatment, and had been undertaken on an exclusively white population.

In the early 1930s, the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) began a program aimed at controlling venereal disease in the rural South. The Julius Rosenwald Fund - a philanthropic organization that was interested in promoting the welfare of African-Americans, provided the funds for a two-year demonstration study in Macon County, Alabama where 82% of the residents were African-Americans, most of whom lived in poverty and had never seen a doctor. A principal aim of this study was to determine the incidence of the disease in the local population, while training both white and African-American physicians and nurses in its treatment. When the results revealed that 36% of the Macon County African-Americans had syphilis, which was far higher than the national rate, the Rosenwald Fund, concerned about the racial implications of this finding, refused requests to support a follow-up project.

The discovery of the fact that the incidence of the disease was higher among African-Americans than among whites was attributed by some to social and economic factors, but by others to a possible difference in susceptibility between whites and non-whites. Indeed one Public Health Service consultant, Dr Joseph E. Moore of Johns Hopkins University School of medicine proposed that "Syphilis in the negro is in many respects a different disease from syphilis in whites. "

3. The Case

In 1932 the PHS decided to proceed with a follow-up study in Macon County. Unlike the project supported by the Rosenwald Fund, the specific goal of the new study was to examine the progression of untreated syphilis in Afro-Americans. Permission was obtained for the use of the excellent medical facilities at the teaching hospital of the Tuskegee Institute and human subjects were recruited by spreading the word among Black people in the county that volunteers would be given free tests for "bad blood," a term used locally to refer to a wide variety of ailments. Thus began what evolved into "The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male," a project that would continue for forty years. The subject group was composed of 616 Afro-American men, 412 of whom had been diagnosed as having syphilis, and 204 controls.

The participants were never explained the true nature of the study. Not only were the syphilitics among them not treated for the disease -- a key aspect of the study design that was retained even after 1943 when penicillin became available as a safe, highly effective cure -- but those few who recognized their condition and attempted to seek help from PHS syphilis treament clinics were prevented from doing so.

Eunice Rivers, an Afro-American PHS nurse assigned to monitor the study, soon became a highly trusted authority figure within the subject community. She was largely responsible for assuring the cooperation of the participants throughout the duration of the study. She was aware of the goals and requirements of the study, including the failure to fully inform the participants of their condition and to deny treatment for syphilis. It was her firm conviction that the men in the study were better off because they received superior medical care for ailments other than syphilis than the vast majority of Afro-Americans in Macon County.

The nature of the Study was certainly not withheld from the nation's medical community. Many venereal disease experts were specifically contacted for advice and opinions. Most of them expressed support for the project. In 1965, 33 years after the Study's initiation, Dr. Irwin Schatz became the first medical professional to formally object to the Study on moral grounds. The PHS simply ignored his complaint. The following year, Peter Buxtin, a venereal disease investigator for the PHS began a prolonged questioning of the morality of the Study. A panel of prominent physicians was convened by the PHS in 1969 to review the Tuskegee study. The panel included neither Afro-Americans nor medical ethicists. Ignoring the fact that it clearly violated the human experimentation guidelines adopted by the PHS in 1966, the panel's recommendation that the Study continue without significant modification was accepted.

By 1972, Buxtin had resigned from the PHS and entered law school. Still bothered by the failure of the agency to take his objections seriously, he contacted the Associated Press, which assigned reporter Jean Heller to the story. On July 25, 1972 the results of her journalist investigation of the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male were published. The response to Heller's revelations was broad-based public outrage, which finally brought the Study to an immediate end.

4. Readings and Resources

A good, detailed case study of the Tuskegee Syphilis Project, with background material and suggestions about teaching the case, written for undergraduate college students is:

- "Bad Blood - A Case Study of the Tuskegee Syphilis", by Ann W . Fourtner, Charles R. Fourtner, and Clyde F. Herreid, Journal of College Science Teaching , March/April 1994, pp 277-285.

An excellent dramatization of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study story, available as a 60-minute video recording is:

- "The Deadly Deception," a Nova video written, produced and directed by Denisce Di Anni, WGBH Boston, 1993 production. [This video is owned by many libraries and is currently distributed by Films for the Humanities and Sciences, P.O. Box 205, Princeton, NJ 08543-2053.]

For a medical report on the Study summarizing the first thirty years of subject observation see:

- "The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis: the 30 th year of observation," by D.H. Rockwell et al., Arch. Intern. Med. , 144, pp 792-798, 1964.

Recent books about the Tuskegee Study include:

- The Tuskegee Syphilis Study , by Fred D. Gray (Montgomery, AL: Black Belt Press, 1998).

- Bad Blood. The Tuskegee Experiment , by J. H. Jones (: Free Press, 1993).

For more information on the ethics of experimentation on human subjects read:

- "The Belmont Report," by The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, OPPR Reports, NIH, PHS, HHS , April , 1979.

- The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code , by G. Annas and M. Grodin, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

For a report on recent revelations concerning unethical experiments that exposed many human subjects to nuclear radiation see:

- "Radiation: Balancing the Record," by Charles C. Mann, Science , 263, pp 470-473, January 28, 1994.

For an excellent treatment of the history of syphilis, which raises many other interesting questions about the nature of scientific research see:

- Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact , by Ludwick Fleck, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979).

5. The Issues

Significant questions of ethics and values raised by this case:

- An explicit requirement of the Tuskegee study was that the subjects not receive available treatment for a debilitating disease, a clear violation of normal medical practice. Would any study involving human subjects that violated normal medical practice necessarily be unethical?

- The Tuskegee victims were not informed -- in fact they were deliberately misinformed -- about the nature of the study in which they were participants. A basic guideline for human subject research, specified in both the Nuremberg Code and the Belmont Report is the requirement of informed consent. What would have constituted informed consent in the case of the Tuskegee Study? If such informed consent had been obtained from the subjects, would this remove all questions about whether the Study was ethical?

- In what sense were the premises and the practices of the Tuskegee study racist? An important question to explore when examining accusations of human rights violations or of prejudicial behavior is whether the standards being applied are those of the time the action took place, and if not, whether this should affect any judgement about the ethics of the situation. (Conforming to official social standards does not necessarily imply that you are behaving in an ethical manner. Most people would consider the medical experiments of the Nazi Doctors to be unethical even though they conformed to the principles spelled out in the Nazi ideology imposed on Germany by the Third Reich.)

- Eunice Rivers, the African-American nurse who played a vital role by befriending the Tuskegee Study participants and assuring their cooperation has justified her support for the project in terms of the fact that the attention that she and the other medical staff gave to the men was more than a non-enrolled, poor, Macon County resident was likely to receive. If you had been in her place, do you think you would have come to the same conclusion with regard to the ethical choices available to you.

- Ordinarily, one would not think of the media as the proper instrument for enforcing public morality. They had that role here, but should they have?

- The political reaction to the Tuskegee revelations was largely responsible for establishing the committee that wrote the Belmont report, which set guidelines for experimentation on human subjects. These guidelines have been the basis for regulations, usually enforced by human subjects research panels, at most public and private institutions that conduct such research. Is this likely to assure that all future research on human subjects will be conducted in a manner that raises no ethical concerns?

- The Belmont Report proposes three criteria for the evaluation of human subjects research, respect for persons , beneficence and justice , as described above in the introductory section. In what ways does the Tuskegee Study fail to conform to each of these criteria.

- In experiments on infants, it is obviously impossible to obtain the informed consent of the subject. This is also true in experiments on senile individuals. Does this mean that ethical considerations preclude using such subjects in any experiment?

Related Resources

Submit Content to the OEC Donate

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. 2055332. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.4 A Case Study – The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

There are different examples in the literature of unethical research that have been conducted in the past. Let’s review one of the studies .

One of the most famous pieces of unethical research undertaken in the United States was the Tuskegee Syphilis study. Officially known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study – An American medical research study called Study of Untreated Syphilis gained attention for its unethical testing on African American patients in the rural South. 12 The U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) experiment, which ran from 1932 through 1972, looked at the untreated syphilis natural course among African American men. 12 The study aimed to find out if the natural course of syphilis in black males differed considerably from that in whites and to see if cardiovascular damage was more common from syphilis than neurological impairment. The participants were not informed that they had syphilis or that sexual activity may spread the illness. Instead, they were informed that they had “bad blood,” a phrase used locally to describe a variety of ailments. Informed consent was not collected from the participants. 12 Some patients received arsenic, bismuth, and mercury as part of the study’s initial treatment phase. However, when the initial research could not yield any valuable information, it was decided to keep track of the participants until they passed away and stop all therapy. 12 After penicillin became available in the middle of the 1940s, the sick men were refused medication; this was still the case 25 years later, in clear contravention of government regulations that required the treatment of venereal disease. More than 100 of the subjects are thought to have passed away from tertiary syphilis. 12

Watch the YouTube video below which briefly describes this study.

Let’s now consider this research in relation to the key principles of research ethics.

Research merit and integrity: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment violated the principle of merit and integrity because it lacked scientific merit. The study was based on outdated and flawed scientific assumptions and failed to contribute to the advancement of scientific knowledge. The study also lacked integrity because the researchers did not adhere to scientific standards of ethical conduct, including obtaining informed consent from the participants.

Respect: The experiment also violated the principle of respect for persons because the researchers did not respect the autonomy of the study participants. The participants were not informed of the nature of the experiment, and they were not given the option to refuse participation. The researchers also failed to respect the dignity and worth of the participants by denying them proper medical treatment.

Beneficence: The experiment violated the principle of beneficence because the researchers failed to maximize benefits and minimize harms to the participants. The participants were denied effective medical treatment, which caused them to suffer needless pain and suffering. The researchers also failed to provide the participants with adequate medical care, even when it became clear that they had contracted syphilis.

Non-maleficence: The men were subjected to invasive, painful procedures, including spinal taps. The men were not informed about their disease, leaving their spouses and other family members vulnerable to catching the disease from them. The study violated the principle of non-maleficence because the researchers did not take steps to avoid causing harm to the participants. The researchers knowingly withheld effective medical treatment from the participants, which caused them to suffer from severe health complications, including blindness, paralysis, and death.

Justice: The study violated the principle of justice because it treated the participants unfairly. The study was conducted exclusively on African American men from a state in the south of the United States, who represented a very vulnerable population and they were denied proper medical treatment. The study also failed to provide compensation or medical care to the participants after the experiment ended.

Overall, the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment is a significant violation of research ethics. The experiment lacked scientific merit, failed to respect the autonomy of the participants, caused needless harm, violated the principle of non-maleficence, and treated the participants unfairly. The experiment highlights the need for ethical guidelines in research to protect the rights and welfare of research participants.

In Australia, the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research was enacted to ensure the ethical conduct of human research. The National Statement was developed jointly by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and Universities Australia. Researchers must adhere to the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, which provides guidelines for ethical research practices. This includes ensuring that the research is culturally sensitive, respectful, and acknowledges the rights of Indigenous participants. The National Statement provides guidelines for researchers, Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) and others conducting an ethical review of research. It also emphasises institutions’ responsibilities for the quality, safety and ethical acceptability of research that they sponsor or permit to be carried out under their auspices. 8

The National Statement is intended for use by:

- any researcher conducting research with human participants;

- any member of an ethical review body reviewing that research;

- those involved in research governance; and

- potential research participants

Before conducting a study, researchers must obtain ethics clearance from all relevant ethics governance bodies, including university bodies and medical institutions. When conducting human research, it is important to abide by the following requirements:

- An individual’s decision to participate in research must be voluntary and based on a well-informed and reasonable understanding of both the proposed research and the implications of participating in it.

- Voluntary and informed participation requires a proper understanding of research objectives, methods, requirements, risks and potential benefits.

- This information should be presented in a manner appropriate to each participant.

- The process of providing information to participants and obtaining their consent should not be just a matter of meeting formal requirements. Participants can ask questions and discuss information and decisions as needed.

- Consent can be expressed orally, in writing, or by other means (eg, survey or action reply implying implied consent).

- It is generally reasonable to reimburse participants for research participation costs such as travel, lodging, and parking. Participants may also be paid for their time. However, payments disproportionate to the time involved or other incentives designed to encourage participants to take risks are ethically unacceptable.

Now identify the ethical issues that may arise in the case scenario presented in the Padlet below

An Introduction to Research Methods for Undergraduate Health Profession Students Copyright © 2023 by Faith Alele and Bunmi Malau-Aduli is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

How the Public Learned About the Infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study

A s the fight over reforms to the American health-care system continues this week, Tuesday marks the 45th anniversary of a grim milestone in the history of health care in the U.S.

On July 25, 1972, the public learned that, over the course of the previous 40 years, a government medical experiment conducted in the Tuskegee, Ala., area had allowed hundreds of African-American men with syphilis to go untreated so that scientists could study the effects of the disease.

“Of about 600 Alabama black men who originally took part in the study, 200 or so were allowed to suffer the disease and its side effects without treatment, even after penicillin was discovered as a cure for syphilis,” the Associated Press reported , breaking the story. “[U.S. Public Health Service officials] contend that survivors of the experiment are now too old to treat for syphilis, but add that PHS doctors are giving the men thorough physical examinations every two years and are treating them for whatever other ailments and diseases they have developed.”

By the time the bombshell report came out, seven men involved had died of syphilis and more than 150 of heart failure that may or may not have been linked to syphilis. Seventy-four participants were still alive, but the government health officials who started the study had already retired. And, because of the study’s length and the way treatment options had evolved in the intervening years, it was hard to pin the blame on an individual — though easy to see that it was wrong, as TIME explained in the Aug. 7, 1972, issue:

At the time the test began, treatment for syphilis was uncertain at best, and involved a lifelong series of risky injections of such toxic substances as bismuth, arsenic and mercury. But in the years following World War II, the PHS’s test became a matter of medical morality. Penicillin had been found to be almost totally effective against syphilis, and by war’s end it had become generally available. But the PHS did not use the drug on those participating in the study unless the patients asked for it. Such a failure seems almost beyond belief, or human compassion. Recent reviews of 125 cases by the PHS’S Center for Disease Control in Atlanta found that half had syphilitic heart valve damage. Twenty-eight had died of cardiovascular or central nervous system problems that were complications of syphilis. The study’s findings on the effects of untreated syphilis have been reported periodically in medical journals for years. Last week’s shock came when an alert A.P. correspondent noticed and reported that the lack of treatment was intentional.

About three months later, the study was terminated, and the families of victims reached a $10 million settlement in 1974 (the terms of which are still being negotiated today by descendants). The last study participant passed away in 2004.

Tuskegee was chosen because it had the highest syphilis rate in the country at the time the study was started. As TIME made clear with a 1940 profile of government efforts to improve the health of African Americans, concern about that statistic had drawn the attention of the federal government and the national media. Surgeon General Thomas Parran boasted that in Macon County, Ala., where Tuskegee is located, the syphilis rate among the African-American population had been nearly 40% in 1929 but had shrunk to 10% by 1939. Serious efforts were being devoted to the cause, the story explained, though the magazine clearly missed the full story of what was going on:

In three years, experts predict, the disease will be wiped out. To root syphilis out of Macon County, the U. S. Public Health Service, the Rosenwald Fund and Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute all joined forces. Leader of the campaign is a white man, the county health officer, a former Georgia farm boy who drove a flivver through fields of mud, 36 miles a day to medical school. Last month, deep-eyed, sunburned Dr. Murray Smith began his tenth year in Macon County. “There’s not much in this job,” said he, “but the love and thanks of the people.” At first the Negroes used to gather in the gloomy courthouse in Tuskegee, while Dr. Smith in the judge’s chambers gave them tests and treatment. Later he set up weekly clinics in old churches or schoolhouses, deep in the parched cotton fields. Last fall the U. S. Public Health Service gave him a streamlined clinic truck. The truck, which has a laboratory with sink and sterilizer, a treatment nook with table and couch, is manned by two young Negro doctors and two nurses. Five days a week it rumbles over the red loam roads. At every crossroads it stops. At the toot of its horn, through the fields come men on muleback, women carrying infants, eager to be first, proud to have a blood test. Some young boys even sneak in to get a second or third test, and many come around to the truck long after they have been cured. One woman who had had six miscarriages got her syphilis cured by Dr. Smith with neoarsphenamine. Proudly she named her first plump baby Neo.

In the years following the disclosure, the Tuskegee study became a byword for the long and complicated history of medical research of African Americans without their consent. In 1997, President Bill Clinton apologized to eight of the survivors. “You did nothing wrong, but you were grievously wronged,” he said. “I apologize and I am sorry that this apology has been so long in coming.” As Clinton noted, African-American participation in medical research and organ donation remained low decades after the 1972 news broke, a fact that has often been attributed to post-Tuskegee wariness.

In 2016, a National Bureau of Economic Research paper argued that after the disclosure of the 1972 study, “life expectancy at age 45 for black men fell by up to 1.5 years in response to the disclosure, accounting for approximately 35% of the 1980 life expectancy gap between black and white men and 25% of the gap between black men and women.” However, many experts argue that the discrepancy has more to do with racial bias in the medical profession.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at [email protected]

Quick Links

Current Courses Don Berkich: PHIL 2306.001: Intro to Ethics PHIL 2306.003: Intro to Ethics Minds and Machines Resources Reading Philosophy Writing Philosophy

- This Semester

- Next Semester

- Past Semesters

- Descriptions

- Two-Year Rotation

- Double-Major

- Don Berkich

- Stefan Sencerz

- Glenn Tiller

- Administration

- Philosophy Club

- Finding Philosophy

- Reading Philosophy

- Writing Philosophy

- Philosophy Discussions

- The McClellan Award

- Undergraduate Journals

- Undergraduate Conferences

"Bad Blood": A Case Study of the Tuskegee Syphilis Project

by A.W. Fourtner, C.R. Fourtner and C.F. Herreid University at Buffalo, State University of New York

mirrored from http://ublib.buffalo.edu/libraries/projects/cases/blood.htm

THE DISEASE

Syphilis is a venereal disease spread during sexual intercourse. It can also be passed from mother to child during pregnancy. It is caused by a corkscrew-shaped bacterium called a spirochete, Treponema pallidum . This microscopic organism resides in many organs of the body but causes sores or ulcers (called chancres) to appear on the skin of the penis, vagina, mouth, and occasionally in the rectum, or on the tongue, lips, or breast. During sex the bacteria leave the sores of one person and enter the moist membranes of their partner's penis. vagina, mouth, or rectum.

Once the spirochetes wiggle inside a victim, they begin to multiple at an amazing rate. (Some bacteria have a doubling rate of 30 minutes. You may want to consider how many bacteria you might have in 12 hours if one bacterium entered your body doubling at that rate.) The spirochetes then enter the lymph circulation, which carries them to nearby lymph glands that may swell in response to the infection.

This first stage of the disease (called primary syphilis) lasts only a few weeks and usually causes hard red sores or ulcers to develop on the genitals of the victim, who can then pass the disease on to someone else. During this primary stage, a blood test will not reveal the disease but the bacteria can be scraped from the sores. The sores soon heal and some people may recover entirely without treatment.

Secondary syphilis develops two to six weeks after the sores heal. Then flu-like symptoms appear with fever, headache, eye inflammation, malaise, and joint pain, along with a skin rash and mouth and genital sores. These symptoms are a clear sign that the spirochetes have traveled throughout the body by way of the lymph and blood systems, where they now can be readily detected by a blood test (e.g., the Wassermann test). Scalp hair may drop out to give a "moth-eaten" look to the head. This secondary stage ends in a few weeks as the sores heal.

Signs of the disease may never reappear even though the bacteria continue to live in the person. However, in about 25% of those originally infected, symptoms will flare up again in a late or tertiary stage syphilis.

Almost any organ can be attacked, such as the cardiovascular system, producing leaking heart valves and aneurysms--balloon-like bulges in the aorta that may burst, leading to instant death. Gummy or rubbery tumors filled with spirochetes and covered by a dried crust of pus may develop on the skin. The bones may deteriorate as in osteomyelitis or tuberculosis and may produce disfiguring facial mutilations as nasal and palate bones are eaten away. If the nervous system is infected, a stumbling foot-slapping gait may occur or, more severely, paralysis, senility, blindness, and insanity.

THE HEALTH PROGRAM

The cause of syphilis, the stages of the disease's development, and the complications that can result from untreated syphilis were all known to medical science in the early 1900s. In 1905, German scientists Hoffman and Schaudinn isolated the bacterium that causes syphilis. In 1907, the Wassermann blood test was developed, enabling physicians to diagnose the disease. Three years later, German scientist Paul Ehrlich created an arsenic compound called salvarsan to treat syphilis. Together with mercury, it was either injected or rubbed onto the skin and often produced serious and occasionally fatal reactions in patients. Treatment was painful and usually required more than a year to complete.

In 1908, Congress established the Division of Venereal Diseases in the United States Public Health Service. Within a year, 44 states had organized separate bureaus for venereal disease control. Unfortunately, free treatment clinics operated only in urban areas for many years. Data collected in a survey begun in 1926 of 25 communities across the United States indicated that the incidence of syphilis among patients under observation was "4.05 cases per 1,000 population, the rate for whites being 4 per 1,000, and that for Negroes 7.2 per 1,000."

In 1929, Dr. Hugh S. Cumming, the Surgeon General of the United States Public Health Service (PHS), asked the Julius Rosenwald Fund for financial support to study the control of venereal disease in the rural South. The Rosenwald Fund was a philanthropic organization that played a key role in promoting the welfare of African-Americans. The Fund agreed to help the PHS in developing health programs for southern African-Americans.

One of the Fund's major goals was to encourage their grantees to use black personnel whenever possible as a means to promote professional integration. Thus, the mission of the Fund seemed to fit well with the plans of the PHS. Macon County, Alabama, was selected as one of five syphilis-control demonstration programs in February 1930. The local Tuskegee Institute endorsed the program. The Institute and its John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital were staffed and administered entirely by African-American physicians and nurses: "The demonstrations would provide training for private physicians, white and colored, in the elements of venereal disease treatments and the more extensive distribution of antisyphilitic drugs and the promotion of wider use of state diagnostic laboratory facilities."

In 1930, Macon County had 27,000 residents, 82 percent of whom were African-Americans, most living in rural poverty in shacks with dirt floors, no plumbing, and poor sanitation. This was the target population, people who "had never in their lives been treated by a doctor." Public health officials arriving on the scene announced they had come to test people for "bad blood." The term included a host of maladies and later surveys suggest that few people connected that term with syphilis.

The syphilis control study in Macon County turned up the alarming news that 36 percent of the African-American population had syphilis. The medical director of the Rosenwald Fund was concerned about the racial connotations of the findings, saying "There is bound to be danger that the impression will be given that syphilis in the South is a Negro problem rather than one of both races." The PHS officer assured the Fund and the Tuskegee Institute that demonstrations would not be used to attack the images of black Americans. He argued that the high syphilis rates were not due to "inherent racial susceptibility" but could be explained by "differences in their respective social and economic status." However, the PHS failed to persuade the Fund that more work could break the cycle of poverty and disease in Macon County. So when the PHS officers suggested a larger scale extension of the work, the Rosenwald Fund trustees voted against the new project.

Building on what had been learned during the Rosenwald Fund demonstrations and the four other sites, the PHS covered the nation with the Wassermann tests. Both blacks and whites were reached with extensive testing, and in some areas mobile treatment clinics were available.

THE EXPERIMENT

As the PHS officers analyzed the data for the final Rosenwald Fund report in September of 1932, and realizing that funding for the project would be discontinued, the idea for a new study evolved into the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male. The idea was to convert the original treatment program into a nontherapeutic human experiment aimed at compiling data on the progression of the disease on untreated African-American males.

There was precedence for such a study. One had been conducted in Oslo, Norway, at the turn of the century on a population of white males and females. An impressive amount of information had been gathered from these patients concerning the progression of the disease. However, questions of manifestation and progression of syphilis in individuals of African descent had not been studied. In light of the discovery that African natives had some rather unique diseases (for example, sick cell anemia--a disease of red blood cells), a study of a population of African males could reveal biological differences during the course of the disease. (Later, the argument that supported continuation of the study may even have been reinforced in the early 1950s when it was suggested that native Africans with the sickle cell trait were less susceptible to the ravages of malaria.)

In fact, Dr. Joseph Earle Moore of the Venereal Disease Clinic of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine stated when consulted, "Syphilis in the Negro is in many respects almost a different disease from syphilis in the white." The PHS doctors felt that this study would emphasize and delineate these differences. Moreover, whereas the Oslo study was retrospective (looking back at old cases), the Macon Study would be a better prospective study, following the progress of the disease through time.

It was estimated that of the 1,400 patients in Macon County admitted to treatment under the Rosenwald Fund, not one had received the full course of medication prescribed as standard therapy for syphilis. The PHS officials decided that these men could be considered untreated because they had not received enough treatment to cure them. In the county there was a well-equipped teaching hospital (the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital at the Tuskegee Institute) that could be used for scientific purposes.

Over the next months in 1932, cooperation was insured from the Alabama State Board of Health, the Macon County Health Department, and the Tuskegee Institute. However, Dr. J.N. Baker, the state health officer, received one important concession in exchange for his approval. Everyone found to have syphilis would have to be treated. Although this would not cure them--the nine-month study was too short--it would keep them non-infectious. Dr. Baker also argued that local physicians be involved.

Dr. Raymond Vonderlehr was chosen for the field work that began in October 1932. Dr. Vonderlehr began his work in Alabama by spreading the word that a new syphilis control demonstration was beginning and that government doctors were giving free blood tests. Black people came to schoolhouses and churches for examination--most had never before seen a doctor. Several hundred men over 25 years old were identified as Wassermann-positive who had not been treated for "bad blood" and had been infected for over five years. Cardiovascular problems seemed particularly evident in this population in the early days, reaffirming that Negroes might be different in their response. But nervous system involvement was not evident.

As Dr. Vonderlehr approached the end of his few months of study, he suggested to his superior, Dr. Clark, that the work continue for five to 10 years because "many interesting facts could be learned regarding the course and complications of untreated syphilis." Dr. Clark retired a few months later and in June 1933 Dr. Vonderlehr was promoted to director of the Division of Venereal Diseases of the PHS.

This promotion began a bureaucratic pattern over the next four decades that saw the position of director go to a physician who had worked on the Tuskegee Study. Dr. Vonderlehr spent much of the summer of 1933 working out the study's logistics, which would enable the PHS to follow the men's health through their lifetime. This included gaining permission from the men and their families to perform an autopsy at the time of their death, thus providing the scientific community with a detailed microscopic description of the diseased organs.

Neither the syphilitics nor the controls (those men free of syphilis who were added to the project) were informed of the study's true objective. These men knew only that they were receiving treatment for "bad blood" and money for burial. Burial stipends began in 1935 funded by the Milbank Memorial Fund.

The skill of the African-American nurse, Eunice Rivers, and the cooperation of the local health providers (most of them white males), were essential in this project. They understood the project details and the fact that the patients' available medical care (other than valid treatment for syphilis) was far better than that for most African-Americans in Macon County. The local draft board agreed to exclude the men in the study from medical treatment when that became an issue during the early 1940s. State health officials also cooperated.

The study was not kept secret from the national medical community in general. Dr. Vonderlehr in 1933 contacted a large number of experts in the field of venereal disease and related medical complications. Most responded with support for the study. The American Heart Association asked for clarification of the scientific validity, then subsequently expressed great doubt and criticism concerning the tests and procedures. Dr. Vonderlehr remained convinced that the study was valid and would prove that syphilis affected African-Americans differently than those of European descent. As director of the PHS Venereal Disease Division, he controlled the funds necessary to conduct the study, as did his successors.

Key to the cooperation of the men in the Tuskegee Study was the African-American PHS nurse assigned to monitor them. She quickly gained their trust. She dealt with their problems. The physicians came to respect her ability to deal with the men. She not only attempted to keep the men in the study, many times she prevented them from receiving medical care from the PHS treatment clinics offering neoarsphenamine and bismuth (the treatment for syphilis) during the late 1930s and early 1940s. She never advocated treating the men. She knew these treatment drugs had side affects. As a nurse, she had been trained to follow doctor's orders. By the time penicillin became available for the treatment of syphilis, not treating these men had become a routine procedure, which she did not question. She truly felt that these men were better off because of the routine medical examinations, distribution of aspirin pink pills that relieved aches and pains, and personal nursing care. She never thought of the men as victims; she was aware of the Oslo study: "This is the way I saw it: that they were studying the Negro, just like they were studying the white man, see, making a comparison." She retired from active nursing in 1965, but assisted during the annual checkups until the experiment ended.

By 1943, when the Division of Venereal Diseases began treating syphilitic patients nationwide with penicillin, the men in the Tuskegee study were not considered patients. They were viewed as experimental subjects and were denied antibiotic treatment. The PHS officials insisted that the Study offered even more of an opportunity to study these men as a "control against which to project not only the results obtained with the rapid schedules of therapy for syphilis but also the costs involved in finding and placing under treatment the infected individuals." There is no evidence that the study had ever been discussed in the light of the Nuremberg Code, a set of ethical principles for human experimentation developed during the trials of Nazi physicians in the aftermath of World War II. Again, the study had become routine.

In 1951, Dr. Trygve Gjustland, then the current director of the Oslo Study, joined the Tuskegee group to review the experiment. He offered suggestions on updating records and reviewing criteria. No one questioned the issue of contamination (men with partial treatment) or ethics. In 1952, the study began to focus on the study of aging, as well as heart disease, because of the long-term data that had been accumulated on the men. It became clear that syphilis generally shortened the lifespan of its victims and that the tissue damage began while the young men were in the second stage of the disease (see tables in Appendix A).

In June 1965, Dr. Irwin J. Schatz became the first medical professional to object to the study. He suggested a need for PHS to reevaluate their moral judgments. The PHS did not respond to his letter. In November 1966 Peter Buxtin, a PHS venereal disease interviewer and investigator, expressed his moral concerns about the study. He continued to question the study within the PHS network.

In February of 1969, the PHS called together a blue ribbon panel to discuss the Tuskegee study. The participants were all physicians, none of whom had training in medical ethics. In addiiton, none of them were of African descent. At no point during the discussions did anyone remind the panel of PHS's own guidelines on human experimentation (established in February 1966). According to records, the original study had been composed of 412 men with syphilis and 204 controls. In 1969, 56 syphilitic subjects and 36 controls were known to be living. A total of 373 men in both groups were known to be dead. The rest were unaccounted for. The age of the survivors ranged from 59 to 85, one claiming to be 102. The outcome of this meeting was that the study would continue. The doctors convinced themselves that the syphilis in the Tuskegee men was too far along to be effectively treated by penicillin and that the men might actually suffer severe complications from such therapy. Even the Macon County Medical Society, now made up of mostly African-American physicians, agreed to assist the PHS. Each was given a list of subjects,

In the late 1960s, PHS physician, Dr. James Lucas, stated in a memorandum that the Tuskegee study was "bad science" because it had been contaminated by treatment. PHS continued to put a positive spin on the experiment by noting that the study had been keeping laboratories supplied with blood samples for evaluating new blood tests for syphilis.

Peter Buxtin, who had left the PHS for law school, bothered by the study and the no-change attitude of the PHS, contacted the Associated Press. Jean Heller, the reporter assigned to the story, did extensive research into the Tuskegee experiment. When interviewed by her, the PHS officials provided her with much of her information. They were men who had nothing to hide. The story broke on July 25, 1972. The study immediately stopped.

The following are a variety of data sets compiled from later publications of the Tuskegee study.

Table 1. 1963 viability data of Tuskegee group

from: Rockwell, et al. (1964)

Table 2. Abnormal findings in 90 syphilitics and 65 controls

Table 3. aortic arch and myocardial abnormalities at autopsy.

from: Caldwell et al. (1973)

Annas, G., and M. Grodin, eds. 1992. The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code . Oxford: Oxford University Press. Barber, B. 1976. The Ethics of Experimentation with Human Subjects. Scientific American 234(2):25-31. Caldwell, J.G. et al. 1973. Aortic regurgitation in the Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis. J. Chronic Dis. 26: 187-199. Jones, J.H. 1993. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Experiment . New York: Free Press. Rockwell, D.H. et al. 1964. The Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis: the 30th year of observation. Arch. Inter. Med. 144: 792-798.

- College of Liberal Arts

- Bell Library

- Academic Calendar

- Mobile Site

- Staff Directory

- Advertise with Ars

Filter by topic

- Biz & IT

- Gaming & Culture

Front page layout

A question of informed consent —

50 years on, the lessons of the tuskegee syphilis study still reverberate, for 40 years, researchers deceived test subjects about the true purpose of the study..

Jennifer Ouellette - May 5, 2022 11:20 am UTC

This year marks the 50th anniversary of The New York Times' exposé of the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study, thanks to a frustrated social worker who tipped off the press. By the time the story broke in 1972, experiments had been conducted on unsuspecting Black men in the area surrounding Tuskegee, Alabama, for 40 years. All 400 or so of the male subjects had contracted syphilis, and all had been told they were receiving treatment for the disease—except they were not.

The researchers in charge of the study instead deliberately withheld treatment in order to monitor the progression of the disease as it advanced unchecked. The study's exposure led to a public outcry and heated debate over informed consent, ultimately giving rise to a number of regulations to prevent such an ethical lapse in the future. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study has since become a vital case study in bioethics, but public awareness of its existence is spotty at best. A new paper published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine seeks to remedy that, and it argues that federal regulation is not enough to prevent similar unethical research.

"Citizens have an obligation to remember the victims of any major catastrophe, as people do with 9/11," the paper's author, Martin Tobin, told Ars. "The men in Tuskegee suffered major injury, including death, at the hands of the premier health arm of the US government. A failure to remember what happened to these men is to add another layer of injury to what they already endured."

Tobin, a professor of medicine at the Hines Veteran Hospital and Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, wanted to ensure that the remembrance didn't get ignored in favor of another 50-year milestone this year—that of the Watergate scandal , which dominated national headlines in 1972 and ultimately led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon two years later. There have been a number of prior academic articles about the Tuskegee study penned by historians or ethicists. But over 45 years of practice, Tobin has conducted his share of research on patients, and he felt that experience gave him a unique vantage point.

Tobin is also a teacher who understands the power of a good story to convey fundamental principles. "Paradoxical though it may seem, scandals provide powerful instruction about research ethics because scandals put a human face on the abstract principles that are being transgressed," said Tobin. "Everything that a medical investigator needs to know about research ethics is contained in the Tuskegee story—and it is more instructive than getting handouts about informed consent and abstract concepts."

The scourge of syphilis

Unlike many ethically questionable research projects, the Tuskegee study was notable because it wasn't done in secret. It had the full support of many prominent leaders in the medical profession. The idea originated in 1932 with Taliaferro Clark, then director of the Venereal Disease division of the Public Health Service (PHS), the precursor to today's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clark read about a 1928 study with white men conducted in Oslo, Norway. He thought it would be a grand idea to conduct similar research using impoverished Black sharecroppers in Macon County, Alabama, many of whom had contracted the disease. At the time, syphilis was a significant health concern, and the effects of the disease were believed to depend on the patient's race.

Subjects were recruited with the help of a Black nurse named Eunice Rivers; her involvement was key to gaining the sharecroppers' trust. In exchange for their participation, subjects were promised free physical examinations, free transportation to and from the clinic, hot meals on those days, and free treatment for any minor ailments. Rivers was also able to convince many families to agree to an autopsy in exchange for funeral benefits—a major concern for the project's leaders. "If the colored population become aware that accepting free hospital care means a post-mortem, every darkey will leave Macon County," one of the doctors on the project wrote to a colleague.

However, the researchers lied to the men about their condition; they told them they were being treated for "bad blood" rather than syphilis. They also lied about the "treatments"; the men were given dummy pills, even after penicillin was found to be effective against syphilis and became widely available. And they lied about the need for painful lumbar punctures to check for neurosyphilis, telling the subjects they were therapeutic rather than purely diagnostic.

A couple of doctors did express concerns about the ethics of the study in 1955 and 1965, but their warnings were ignored. In December 1965, a Czech-born social worker named Peter Buxton joined what was by then the CDC to interview patients with venereal disease. He soon wrote to the CDC expressing "grave moral concerns" about the Tuskegee study. When the CDC invited him to a meeting in Atlanta to discuss the matter, Buxton was berated by CDC physician John Charles Cutler, who clearly "thought I was a lunatic." Undeterred, Buxton again wrote to the CDC in November 1968, and this time, the director, David Sencer, established a Blue Ribbon Panel the following February to discuss the ethical issues.

When the panel decided that the men should not be treated—they deemed the study too important to science—Buxton contacted the press. The Washington Star broke the story on July 25, 1972, and it landed on the front page of The New York Times the following day. The public outcry led an ad hoc advisory panel to investigate further, and the study was finally terminated in October 1972. By then, 28 of the subjects had died from syphilis, 100 had died from related complications, 40 of the subjects' wives had been infected, and 19 children had been born with congenital syphilis.

reader comments

Channel ars technica.

Close this Alert

- Academic Calendar

- Campus Directory

- Campus Labs

- Course Catalog

- Events Calendar

- Golden Tiger Gear

- Golden Tiger Health Check

- Golden Tiger Network

- NAVIGATE (EAB)

Quick Links

- Academic Affairs - Provost

- ADA 504 Accommodations - Accessibility

- Administration

- Advancement and Development

- Air Force ROTC

- Alumni & Friends

- Anonymous Reporting

- Bioethics Center

- Board of Trustees

- Campus Tours

- Career Center

- Colleges & Schools

- Cooperative Extension

- Dean of Students and Student Conduct

- E-Learning (ODEOL)

- Environmental Health & Safety

- Facilities Services Requests

- Faculty Senate

- Financial Aid

- General Counsel and External Affairs

- Graduate School

- HEERF - CARES Act Emergency Funds

- Housing and Residence Life

- Human Resources

- Information Technology

- Institutional Effectiveness

- Integrative Biosciences

- Office of the President

- Online Degree Admissions

- Police Department - TU

- Presidential Search

- Research and Sponsored Programs

- ROTC at Tuskegee University

- Scholarships

- Staff Senate

- Strategic Plan

- Student Affairs

- Student Complaints

- Student Handbook

- Student Health Center

- Student Life and Development

- Tuskegee Scholarly Publications

- Tuition and Fees

- Tuskegee University Global Office

- TU Help Desk Service Portal

- TU Office of Undergraduate Research

- University Audit and Risk Management

Tuskegee University

- Current Trustees

- Board Communications

- Board Meeting Dates

- Campus Master Plan

About the USPHS Syphilis Study

Where the Study Took Place

The study took place in Macon County, Alabama, the county seat of Tuskegee referred to as the "Black Belt" because of its rich soil and vast number of black sharecroppers who were the economic backbone of the region. The research itself took place on the campus of Tuskegee Institute.

What it Was Designed to Find Out

The intent of the study was to record the natural history of syphilis in Black people. The study was called the "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male." When the study was initiated there were no proven treatments for the disease. Researchers told the men participating in the study that they were to be treated for "bad blood." This term was used locally by people to describe a host of diagnosable ailments including but not limited to anemia, fatigue, and syphilis.

Who Were the Participants

A total of 600 men were enrolled in the study. Of this group 399, who had syphilis were a part of the experimental group and 201 were control subjects. Most of the men were poor and illiterate sharecroppers from the county.

What the Men Received in Exchange for Participation

The men were offered what most Negroes could only dream of in terms of medical care and survivors insurance. They were enticed and enrolled in the study with incentives including: medical exams, rides to and from the clinics, meals on examination days, free treatment for minor ailments and guarantees that provisions would be made after their deaths in terms of burial stipends paid to their survivors.

Treatment Withheld

There were no proven treatments for syphilis when the study began. When penicillin became the standard treatment for the disease in 1947 the medicine was withheld as a part of the treatment for both the experimental group and control group.

How/Why the Study Ended

On July 25, 1972 Jean Heller of the Associated Press broke the story that appeared simultaneously both in New York and Washington, that there had been a 40-year nontherapeutic experiment called "a study" on the effects of untreated syphilis on Black men in the rural south.

Between the start of the study in 1932 and 1947, the date when penicillin was determined as a cure for the disease, dozens of men had died and their wives, children and untold number of others had been infected. This set into motion international public outcry and a series of actions initiated by U.S. federal agencies. The Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs appointed an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, comprised of nine members from the fields of health administration, medicine, law, religion, education, etc. to review the study.

While the panel concluded that the men participated in the study freely, agreeing to the examinations and treatments, there was evidence that scientific research protocol routinely applied to human subjects was either ignored or deeply flawed to ensure the safety and well-being of the men involved. Specifically, the men were never told about or offered the research procedure called informed consent. Researchers had not informed the men of the actual name of the study, i.e. "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male," its purpose, and potential consequences of the treatment or non-treatment that they would receive during the study. The men never knew of the debilitating and life threatening consequences of the treatments they were to receive, the impact on their wives, girlfriends, and children they may have conceived once involved in the research. The panel also concluded that there were no choices given to the participants to quit the study when penicillin became available as a treatment and cure for syphilis.

Reviewing the results of the research the panel concluded that the study was "ethically unjustified." The panel articulated all of the above findings in October of 1972 and then one month later the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs officially declared the end of the Tuskegee Study.

Class-Action Suit

In the summer of 1973, Attorney Fred Gray filed a class-action suit on behalf of the men in the study, their wives, children and families. It ended a settlement giving more than $9 million to the study participants.

The Role of the US Public Health Service

In the beginning of the 20th Century, the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) was entrusted with the responsibility to monitor, identify trends in the heath of the citizenry, and develop interventions to treat disease, ailments and negative trends adversely impacting the health and wellness of Americans. It was organized into sections and divisions including one devoted to venereal diseases. All sections of the PHS conducted scientific research involving human beings. The research standards were for their times adequate, by comparison to today's standards dramatically different and influenced by the professional and personal biases of the people leading the PHS. Scientists believed that few people outside of the scientific community could comprehend the complexities of research from the nature of the scientific experiments to the consent involved in becoming a research subject. These sentiments were particularly true about the poor and uneducated Black community.

The PHS began working with Tuskegee Institute in 1932 to study hundreds of black men with syphilis from Macon County, Alabama.

Compensation for Participants

As part of the class-action suit settlement, the U.S. government promised to provide a range of free services to the survivors of the study, their wives, widows, and children. All living participants became immediately entitled to free medical and burial services. These services were provided by the Tuskegee Health Benefit Program, which was and continues to be administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in their National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention.

1996 Tuskegee Legacy Committee

In February of 1994 at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library in Charlottesville, VA, a symposium was held entitled "Doing Bad in the Name of Good?: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Its Legacy." Resulting from this gathering was the creation of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee which met for the first time in January 18th & 19th of 1996. The committee had two goals; (1) to persuade President Clinton to apologize on behalf of the government for the atrocities of the study and (2) to develop a strategy to address the damages of the study to the psyche of African-Americans and others about the ethical behavior of government-led research; rebuilding the reputation of Tuskegee through public education about the study, developing a clearinghouse on the ethics of scientific research and scholarship and assembling training programs for health care providers. After intensive discussions, the Committee's final report in May of 1996 urged President Clinton to apologize for the emotional, medical, research and psychological damage of the study. On May 16th at a White House ceremony attended by the men, members of the Legacy Committee and others representing the medical and research communities, the apology was delivered to the surviving participants of the study and families of the deceased.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Bad Blood:" A Case Study of the Tuskegee Syphilis Project

Related Papers

sukayana 10

Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved

DhananJAYa Arekere PhD MPH

Health Education & Behavior

This report explores the level of detailed knowledge about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (TSS) among 848 Blacks and Whites in three U.S. cities across an array of demographic variables. The Tuskegee Legacy Project (TLP) Questionnaire was used, which was designed to explore the willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical studies. A component of the TLP Questionnaire, the TSS Facts & Myths Quiz, consisting of seven yes/no factual questions, was used to establish respondents’ level of detailed knowledge on the TSS. Both Blacks and Whites had similar very low mean quiz score on the 7-point scale, with Blacks’ scores being slightly higher than Whites (1.2 vs. 0.9, p = .003). When analyzing the level of knowledge between racial groups by various demographic variables, several patterns emerged: (a) higher education levels were associated with higher levels of detailed knowledge and (b) for both Blacks and Whites, 30 to 59 years old knew the most about TSS compared with younger and...

The Hastings Center Report

Allan Brandt

American Journal of Public Health

Vanessa Northington Gamble

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study continues to cast its long shadow on the contemporary relationship between African Americans and the biomedical community. Numerous reports have argued that the Tuskegee Syphilis Study is the most important reason why many African Americans distrust the institutions of medicine and public health. Such an interpretation neglects a critical historical point: the mistrust predated public revelations about the Tuskegee study. This paper places the syphilis study within a broader historical and social context to demonstrate that several factors have influenced--and continue to influence--African American's attitudes toward the biomedical community.

HARRIET A . WASHINGTON

Online Journal of Health Ethics

Leonard Vernon

The words "human medical experimentation" conjure up visions of Nazi medicine, which has come to exemplify the worst evils in the history of humankind. Places like Auschwitz and Dachau, where human life was cheap and test subjects plentiful were used as laboratories. In 2010 the US government apologized to Guatemala for allowing U.S. doctors to infect Guatemalan prisoners and mental patients with syphilis 65 years earlier, while acknowledging dozens of similar experiments in the United States. These included studies that often involved making healthy people sick. such as in the Tuskegee syphilis study. These experiments were often life threatening and took place with the direct approval and/or supervision of some of the country's most prestigious research institutions and some of the leading medical researchers. Among these was the prestigious cancer research center in New York City, Sloan Kettering Hospital and its director of cancer research Chester Southam, MD.

Matthew Gambino

Syphilis occupies a unique position in the history of U.S. medicine and medical ethics. Given its widespread prevalence and variable presentation, syphilis was a major professional concern among late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century physicians. Syphilis was also at the center of perhaps the most famous example of medical racism in our history, the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, in which officials followed the natural history of the disease in a cohort of black men for forty years without offering treatment, even once penicillin became available. In this essay, I call attention to a less well-known aspect of syphilis and its history. I examine one of the disease's most dreaded manifestations, neurosyphilis (also known as general paresis or general paralysis of the insane), and its treatment via malarial inoculation from the 1920s into the 1950s. The goal of this treatment, dramatic even to observers at the time, was to produce spiking fevers that would kill the syphilitic spirochete and arrest the disease process. My focus will be on developments at St. Elizabeths Hospital, a large-scale federal psychiatric facility in the District of Columbia that served the city's residents and members of the U.S. military. Physicians at St. Elizabeths were the first in the United States to experiment with malarial fever therapy, treating their initial cohort of patients in December of 1922. Malarial fever therapy raised a host of ethical questions, rendered all the more complex from today's vantage point by efforts to understand them within the context of the time. What sorts of risks, both from malaria and via indirect exposure, might be deemed acceptable in the treatment of a devastating and almost invariably fatal disease? How ought researchers and clinicians to have approached the question of consent, itself an evolving concept in the early decades of the twentieth century, when the disease they were targeting impaired a patient's ability to reason effectively? Finally, at a time when segregated and inferior care for black Americans was the norm and when the black community bore a disproportionate burden of disease, who would have had access to malarial fever therapy, and at what cost?

Harriet Washington

A second watershed involved AMA-promoted educational reforms, including the 1910 Flexner report. Straightforwardly applied, the report's population-based criterion for determining the need for physicians would have recommended increased training of African American physicians to serve the approximately 9 million African Americans in the segregated south.

Esteban González-López , Esther Cuerda

Even after the Nuremberg code was published, research on syphilis often continued to fall far short of ethical standards. We review post-World War II research on this disease, focusing on the work carried out in Guatemala and Tuskegee. Over a thousand adults were deliberately inoculated with infectious material for syphilis, chancroid, and gonorrhea between 1946 and 1948 in Guatemala, and thousands of serologies were performed in individuals belonging to indigenous populations or sheltered in orphanages. The Tuskegee syphilis study, conducted by the US Public Health Service, took place between 1932 and 1972 with the aim of following the natural history of the disease when left untreated. The subjects belonged to a rural black population and the study was not halted when effective treatment for syphilis became available in 1945.

RELATED PAPERS

IOSR Journals

athraa azeez

The Journal of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences

leila dehghankar

Ana Clavería

Abhishek Borpujari

Science and Technology for the Built Environment

Risto Kosonen

Accounting Forum

Vanisha Oogarah-Hanuman

Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment

Shay Be'er

Víctor Yepes

International Association for Development of the Information Society

Jenny S Wakefield

Journal of investigational allergology & clinical immunology