Peer Recognized

Make a name in academia

How to Write a Research Paper: the LEAP approach (+cheat sheet)

In this article I will show you how to write a research paper using the four LEAP writing steps. The LEAP academic writing approach is a step-by-step method for turning research results into a published paper .

The LEAP writing approach has been the cornerstone of the 70 + research papers that I have authored and the 3700+ citations these paper have accumulated within 9 years since the completion of my PhD. I hope the LEAP approach will help you just as much as it has helped me to make an real, tangible impact with my research.

What is the LEAP research paper writing approach?

I designed the LEAP writing approach not only for merely writing the papers. My goal with the writing system was to show young scientists how to first think about research results and then how to efficiently write each section of the research paper.

In other words, you will see how to write a research paper by first analyzing the results and then building a logical, persuasive arguments. In this way, instead of being afraid of writing research paper, you will be able to rely on the paper writing process to help you with what is the most demanding task in getting published – thinking.

The four research paper writing steps according to the LEAP approach:

I will show each of these steps in detail. And you will be able to download the LEAP cheat sheet for using with every paper you write.

But before I tell you how to efficiently write a research paper, I want to show you what is the problem with the way scientists typically write a research paper and why the LEAP approach is more efficient.

How scientists typically write a research paper (and why it isn’t efficient)

Writing a research paper can be tough, especially for a young scientist. Your reasoning needs to be persuasive and thorough enough to convince readers of your arguments. The description has to be derived from research evidence, from prior art, and from your own judgment. This is a tough feat to accomplish.

The figure below shows the sequence of the different parts of a typical research paper. Depending on the scientific journal, some sections might be merged or nonexistent, but the general outline of a research paper will remain very similar.

Here is the problem: Most people make the mistake of writing in this same sequence.

While the structure of scientific articles is designed to help the reader follow the research, it does little to help the scientist write the paper. This is because the layout of research articles starts with the broad (introduction) and narrows down to the specifics (results). See in the figure below how the research paper is structured in terms of the breath of information that each section entails.

How to write a research paper according to the LEAP approach

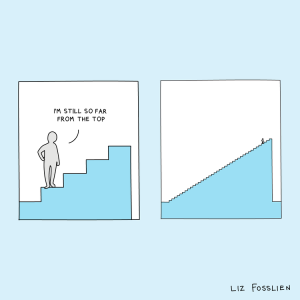

For a scientist, it is much easier to start writing a research paper with laying out the facts in the narrow sections (i.e. results), step back to describe them (i.e. write the discussion), and step back again to explain the broader picture in the introduction.

For example, it might feel intimidating to start writing a research paper by explaining your research’s global significance in the introduction, while it is easy to plot the figures in the results. When plotting the results, there is not much room for wiggle: the results are what they are.

Starting to write a research papers from the results is also more fun because you finally get to see and understand the complete picture of the research that you have worked on.

Most importantly, following the LEAP approach will help you first make sense of the results yourself and then clearly communicate them to the readers. That is because the sequence of writing allows you to slowly understand the meaning of the results and then develop arguments for presenting to your readers.

I have personally been able to write and submit a research article in three short days using this method.

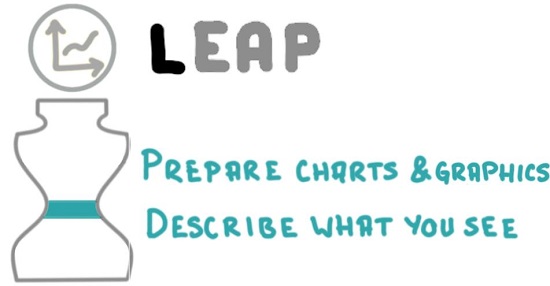

Step 1: Lay Out the Facts

You have worked long hours on a research project that has produced results and are no doubt curious to determine what they exactly mean. There is no better way to do this than by preparing figures, graphics and tables. This is what the first LEAP step is focused on – diving into the results.

How to p repare charts and tables for a research paper

Your first task is to try out different ways of visually demonstrating the research results. In many fields, the central items of a journal paper will be charts that are based on the data generated during research. In other fields, these might be conceptual diagrams, microscopy images, schematics and a number of other types of scientific graphics which should visually communicate the research study and its results to the readers. If you have reasonably small number of data points, data tables might be useful as well.

Tips for preparing charts and tables

- Try multiple chart types but in the finished paper only use the one that best conveys the message you want to present to the readers

- Follow the eight chart design progressions for selecting and refining a data chart for your paper: https://peerrecognized.com/chart-progressions

- Prepare scientific graphics and visualizations for your paper using the scientific graphic design cheat sheet: https://peerrecognized.com/tools-for-creating-scientific-illustrations/

How to describe the results of your research

Now that you have your data charts, graphics and tables laid out in front of you – describe what you see in them. Seek to answer the question: What have I found? Your statements should progress in a logical sequence and be backed by the visual information. Since, at this point, you are simply explaining what everyone should be able to see for themselves, you can use a declarative tone: The figure X demonstrates that…

Tips for describing the research results :

- Answer the question: “ What have I found? “

- Use declarative tone since you are simply describing observations

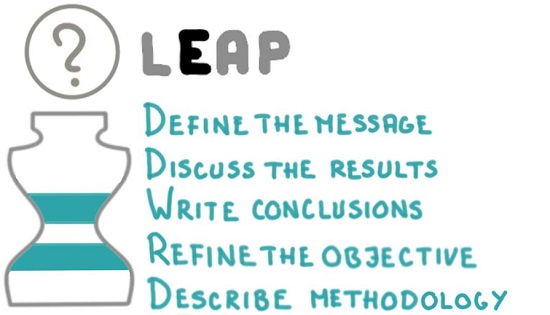

Step 2: Explain the results

The core aspect of your research paper is not actually the results; it is the explanation of their meaning. In the second LEAP step, you will do some heavy lifting by guiding the readers through the results using logic backed by previous scientific research.

How to define the Message of a research paper

To define the central message of your research paper, imagine how you would explain your research to a colleague in 20 seconds . If you succeed in effectively communicating your paper’s message, a reader should be able to recount your findings in a similarly concise way even a year after reading it. This clarity will increase the chances that someone uses the knowledge you generated, which in turn raises the likelihood of citations to your research paper.

Tips for defining the paper’s central message :

- Write the paper’s core message in a single sentence or two bullet points

- Write the core message in the header of the research paper manuscript

How to write the Discussion section of a research paper

In the discussion section you have to demonstrate why your research paper is worthy of publishing. In other words, you must now answer the all-important So what? question . How well you do so will ultimately define the success of your research paper.

Here are three steps to get started with writing the discussion section:

- Write bullet points of the things that convey the central message of the research article (these may evolve into subheadings later on).

- Make a list with the arguments or observations that support each idea.

- Finally, expand on each point to make full sentences and paragraphs.

Tips for writing the discussion section:

- What is the meaning of the results?

- Was the hypothesis confirmed?

- Write bullet points that support the core message

- List logical arguments for each bullet point, group them into sections

- Instead of repeating research timeline, use a presentation sequence that best supports your logic

- Convert arguments to full paragraphs; be confident but do not overhype

- Refer to both supportive and contradicting research papers for maximum credibility

How to write the Conclusions of a research paper

Since some readers might just skim through your research paper and turn directly to the conclusions, it is a good idea to make conclusion a standalone piece. In the first few sentences of the conclusions, briefly summarize the methodology and try to avoid using abbreviations (if you do, explain what they mean).

After this introduction, summarize the findings from the discussion section. Either paragraph style or bullet-point style conclusions can be used. I prefer the bullet-point style because it clearly separates the different conclusions and provides an easy-to-digest overview for the casual browser. It also forces me to be more succinct.

Tips for writing the conclusion section :

- Summarize the key findings, starting with the most important one

- Make conclusions standalone (short summary, avoid abbreviations)

- Add an optional take-home message and suggest future research in the last paragraph

How to refine the Objective of a research paper

The objective is a short, clear statement defining the paper’s research goals. It can be included either in the final paragraph of the introduction, or as a separate subsection after the introduction. Avoid writing long paragraphs with in-depth reasoning, references, and explanation of methodology since these belong in other sections. The paper’s objective can often be written in a single crisp sentence.

Tips for writing the objective section :

- The objective should ask the question that is answered by the central message of the research paper

- The research objective should be clear long before writing a paper. At this point, you are simply refining it to make sure it is addressed in the body of the paper.

How to write the Methodology section of your research paper

When writing the methodology section, aim for a depth of explanation that will allow readers to reproduce the study . This means that if you are using a novel method, you will have to describe it thoroughly. If, on the other hand, you applied a standardized method, or used an approach from another paper, it will be enough to briefly describe it with reference to the detailed original source.

Remember to also detail the research population, mention how you ensured representative sampling, and elaborate on what statistical methods you used to analyze the results.

Tips for writing the methodology section :

- Include enough detail to allow reproducing the research

- Provide references if the methods are known

- Create a methodology flow chart to add clarity

- Describe the research population, sampling methodology, statistical methods for result analysis

- Describe what methodology, test methods, materials, and sample groups were used in the research.

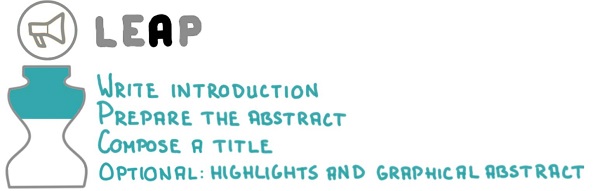

Step 3: Advertize the research

Step 3 of the LEAP writing approach is designed to entice the casual browser into reading your research paper. This advertising can be done with an informative title, an intriguing abstract, as well as a thorough explanation of the underlying need for doing the research within the introduction.

How to write the Introduction of a research paper

The introduction section should leave no doubt in the mind of the reader that what you are doing is important and that this work could push scientific knowledge forward. To do this convincingly, you will need to have a good knowledge of what is state-of-the-art in your field. You also need be able to see the bigger picture in order to demonstrate the potential impacts of your research work.

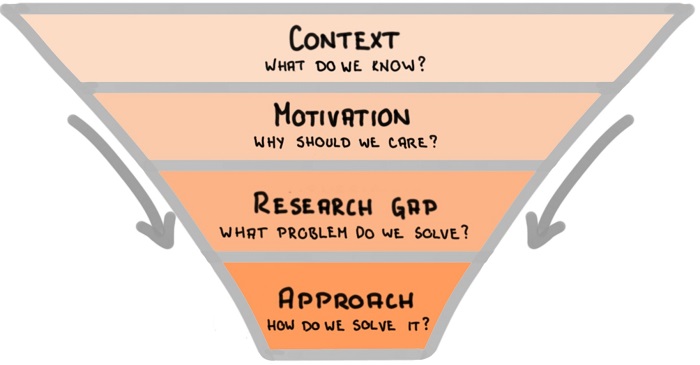

Think of the introduction as a funnel, going from wide to narrow, as shown in the figure below:

- Start with a brief context to explain what do we already know,

- Follow with the motivation for the research study and explain why should we care about it,

- Explain the research gap you are going to bridge within this research paper,

- Describe the approach you will take to solve the problem.

Tips for writing the introduction section :

- Follow the Context – Motivation – Research gap – Approach funnel for writing the introduction

- Explain how others tried and how you plan to solve the research problem

- Do a thorough literature review before writing the introduction

- Start writing the introduction by using your own words, then add references from the literature

How to prepare the Abstract of a research paper

The abstract acts as your paper’s elevator pitch and is therefore best written only after the main text is finished. In this one short paragraph you must convince someone to take on the time-consuming task of reading your whole research article. So, make the paper easy to read, intriguing, and self-explanatory; avoid jargon and abbreviations.

How to structure the abstract of a research paper:

- The abstract is a single paragraph that follows this structure:

- Problem: why did we research this

- Methodology: typically starts with the words “Here we…” that signal the start of own contribution.

- Results: what we found from the research.

- Conclusions: show why are the findings important

How to compose a research paper Title

The title is the ultimate summary of a research paper. It must therefore entice someone looking for information to click on a link to it and continue reading the article. A title is also used for indexing purposes in scientific databases, so a representative and optimized title will play large role in determining if your research paper appears in search results at all.

Tips for coming up with a research paper title:

- Capture curiosity of potential readers using a clear and descriptive title

- Include broad terms that are often searched

- Add details that uniquely identify the researched subject of your research paper

- Avoid jargon and abbreviations

- Use keywords as title extension (instead of duplicating the words) to increase the chance of appearing in search results

How to prepare Highlights and Graphical Abstract

Highlights are three to five short bullet-point style statements that convey the core findings of the research paper. Notice that the focus is on the findings, not on the process of getting there.

A graphical abstract placed next to the textual abstract visually summarizes the entire research paper in a single, easy-to-follow figure. I show how to create a graphical abstract in my book Research Data Visualization and Scientific Graphics.

Tips for preparing highlights and graphical abstract:

- In highlights show core findings of the research paper (instead of what you did in the study).

- In graphical abstract show take-home message or methodology of the research paper. Learn more about creating a graphical abstract in this article.

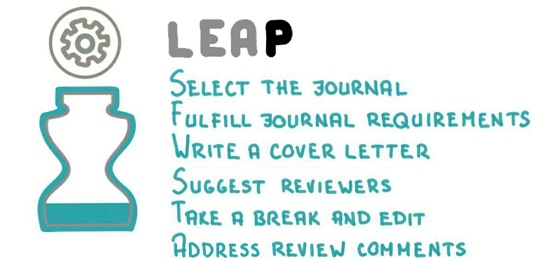

Step 4: Prepare for submission

Sometimes it seems that nuclear fusion will stop on the star closest to us (read: the sun will stop to shine) before a submitted manuscript is published in a scientific journal. The publication process routinely takes a long time, and after submitting the manuscript you have very little control over what happens. To increase the chances of a quick publication, you must do your homework before submitting the manuscript. In the fourth LEAP step, you make sure that your research paper is published in the most appropriate journal as quickly and painlessly as possible.

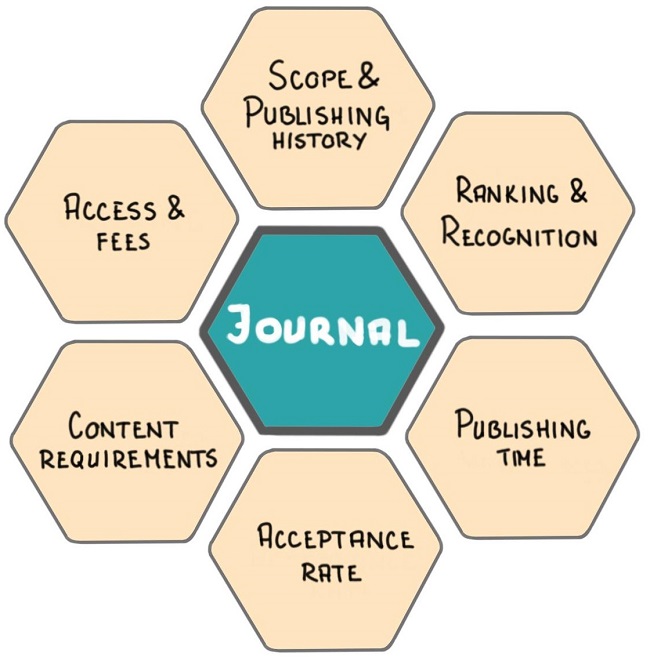

How to select a scientific Journal for your research paper

The best way to find a journal for your research paper is it to review which journals you used while preparing your manuscript. This source listing should provide some assurance that your own research paper, once published, will be among similar articles and, thus, among your field’s trusted sources.

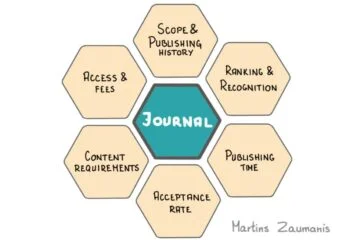

After this initial selection of hand-full of scientific journals, consider the following six parameters for selecting the most appropriate journal for your research paper (read this article to review each step in detail):

- Scope and publishing history

- Ranking and Recognition

- Publishing time

- Acceptance rate

- Content requirements

- Access and Fees

How to select a journal for your research paper:

- Use the six parameters to select the most appropriate scientific journal for your research paper

- Use the following tools for journal selection: https://peerrecognized.com/journals

- Follow the journal’s “Authors guide” formatting requirements

How to Edit you manuscript

No one can write a finished research paper on their first attempt. Before submitting, make sure to take a break from your work for a couple of days, or even weeks. Try not to think about the manuscript during this time. Once it has faded from your memory, it is time to return and edit. The pause will allow you to read the manuscript from a fresh perspective and make edits as necessary.

I have summarized the most useful research paper editing tools in this article.

Tips for editing a research paper:

- Take time away from the research paper to forget about it; then returning to edit,

- Start by editing the content: structure, headings, paragraphs, logic, figures

- Continue by editing the grammar and language; perform a thorough language check using academic writing tools

- Read the entire paper out loud and correct what sounds weird

How to write a compelling Cover Letter for your paper

Begin the cover letter by stating the paper’s title and the type of paper you are submitting (review paper, research paper, short communication). Next, concisely explain why your study was performed, what was done, and what the key findings are. State why the results are important and what impact they might have in the field. Make sure you mention how your approach and findings relate to the scope of the journal in order to show why the article would be of interest to the journal’s readers.

I wrote a separate article that explains what to include in a cover letter here. You can also download a cover letter template from the article.

Tips for writing a cover letter:

- Explain how the findings of your research relate to journal’s scope

- Tell what impact the research results will have

- Show why the research paper will interest the journal’s audience

- Add any legal statements as required in journal’s guide for authors

How to Answer the Reviewers

Reviewers will often ask for new experiments, extended discussion, additional details on the experimental setup, and so forth. In principle, your primary winning tactic will be to agree with the reviewers and follow their suggestions whenever possible. After all, you must earn their blessing in order to get your paper published.

Be sure to answer each review query and stick to the point. In the response to the reviewers document write exactly where in the paper you have made any changes. In the paper itself, highlight the changes using a different color. This way the reviewers are less likely to re-read the entire article and suggest new edits.

In cases when you don’t agree with the reviewers, it makes sense to answer more thoroughly. Reviewers are scientifically minded people and so, with enough logical and supported argument, they will eventually be willing to see things your way.

Tips for answering the reviewers:

- Agree with most review comments, but if you don’t, thoroughly explain why

- Highlight changes in the manuscript

- Do not take the comments personally and cool down before answering

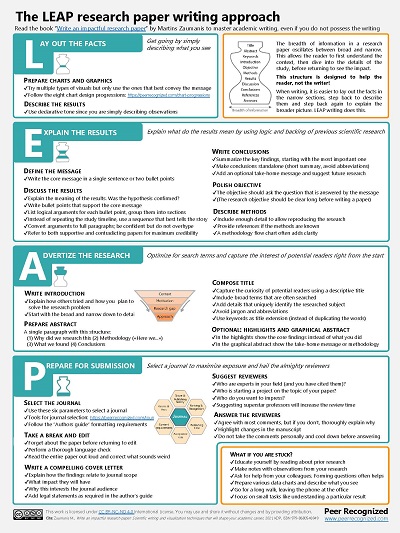

The LEAP research paper writing cheat sheet

Imagine that you are back in grad school and preparing to take an exam on the topic: “How to write a research paper”. As an exemplary student, you would, most naturally, create a cheat sheet summarizing the subject… Well, I did it for you.

This one-page summary of the LEAP research paper writing technique will remind you of the key research paper writing steps. Print it out and stick it to a wall in your office so that you can review it whenever you are writing a new research paper.

Now that we have gone through the four LEAP research paper writing steps, I hope you have a good idea of how to write a research paper. It can be an enjoyable process and once you get the hang of it, the four LEAP writing steps should even help you think about and interpret the research results. This process should enable you to write a well-structured, concise, and compelling research paper.

Have fund with writing your next research paper. I hope it will turn out great!

Learn writing papers that get cited

The LEAP writing approach is a blueprint for writing research papers. But to be efficient and write papers that get cited, you need more than that.

My name is Martins Zaumanis and in my interactive course Research Paper Writing Masterclass I will show you how to visualize your research results, frame a message that convinces your readers, and write each section of the paper. Step-by-step.

And of course – you will learn to respond the infamous Reviewer No.2.

Hey! My name is Martins Zaumanis and I am a materials scientist in Switzerland ( Google Scholar ). As the first person in my family with a PhD, I have first-hand experience of the challenges starting scientists face in academia. With this blog, I want to help young researchers succeed in academia. I call the blog “Peer Recognized”, because peer recognition is what lifts academic careers and pushes science forward.

Besides this blog, I have written the Peer Recognized book series and created the Peer Recognized Academy offering interactive online courses.

Related articles:

One comment

- Pingback: Research Paper Outline with Key Sentence Skeleton (+Paper Template)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

I want to join the Peer Recognized newsletter!

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Copyright © 2024 Martins Zaumanis

Contacts: [email protected]

Privacy Policy

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

Can you help me with a full paper template for this Abstract:

Background: Energy and sports drinks have gained popularity among diverse demographic groups, including adolescents, athletes, workers, and college students. While often used interchangeably, these beverages serve distinct purposes, with energy drinks aiming to boost energy and cognitive performance, and sports drinks designed to prevent dehydration and replenish electrolytes and carbohydrates lost during physical exertion.

Objective: To assess the nutritional quality of energy and sports drinks in Egypt.

Material and Methods: A cross-sectional study assessed the nutrient contents, including energy, sugar, electrolytes, vitamins, and caffeine, of sports and energy drinks available in major supermarkets in Cairo, Alexandria, and Giza, Egypt. Data collection involved photographing all relevant product labels and recording nutritional information. Descriptive statistics and appropriate statistical tests were employed to analyze and compare the nutritional values of energy and sports drinks.

Results: The study analyzed 38 sports drinks and 42 energy drinks. Sports drinks were significantly more expensive than energy drinks, with higher net content and elevated magnesium, potassium, and vitamin C. Energy drinks contained higher concentrations of caffeine, sugars, and vitamins B2, B3, and B6.

Conclusion: Significant nutritional differences exist between sports and energy drinks, reflecting their intended uses. However, these beverages’ high sugar content and calorie loads raise health concerns. Proper labeling, public awareness, and responsible marketing are essential to guide safe consumption practices in Egypt.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Writing a Research Paper

This page lists some of the stages involved in writing a library-based research paper.

Although this list suggests that there is a simple, linear process to writing such a paper, the actual process of writing a research paper is often a messy and recursive one, so please use this outline as a flexible guide.

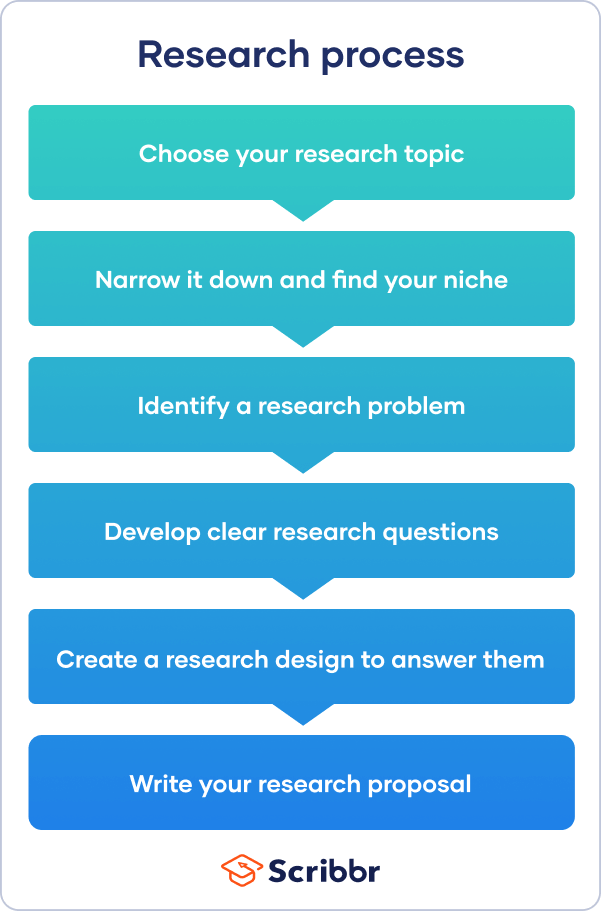

Discovering, Narrowing, and Focusing a Researchable Topic

- Try to find a topic that truly interests you

- Try writing your way to a topic

- Talk with your course instructor and classmates about your topic

- Pose your topic as a question to be answered or a problem to be solved

Finding, Selecting, and Reading Sources

You will need to look at the following types of sources:

- library catalog, periodical indexes, bibliographies, suggestions from your instructor

- primary vs. secondary sources

- journals, books, other documents

Grouping, Sequencing, and Documenting Information

The following systems will help keep you organized:

- a system for noting sources on bibliography cards

- a system for organizing material according to its relative importance

- a system for taking notes

Writing an Outline and a Prospectus for Yourself

Consider the following questions:

- What is the topic?

- Why is it significant?

- What background material is relevant?

- What is my thesis or purpose statement?

- What organizational plan will best support my purpose?

Writing the Introduction

In the introduction you will need to do the following things:

- present relevant background or contextual material

- define terms or concepts when necessary

- explain the focus of the paper and your specific purpose

- reveal your plan of organization

Writing the Body

- Use your outline and prospectus as flexible guides

- Build your essay around points you want to make (i.e., don’t let your sources organize your paper)

- Integrate your sources into your discussion

- Summarize, analyze, explain, and evaluate published work rather than merely reporting it

- Move up and down the “ladder of abstraction” from generalization to varying levels of detail back to generalization

Writing the Conclusion

- If the argument or point of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to add your points up, to explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction.

- Perhaps suggest what about this topic needs further research.

Revising the Final Draft

- Check overall organization : logical flow of introduction, coherence and depth of discussion in body, effectiveness of conclusion.

- Paragraph level concerns : topic sentences, sequence of ideas within paragraphs, use of details to support generalizations, summary sentences where necessary, use of transitions within and between paragraphs.

- Sentence level concerns: sentence structure, word choices, punctuation, spelling.

- Documentation: consistent use of one system, citation of all material not considered common knowledge, appropriate use of endnotes or footnotes, accuracy of list of works cited.

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

- How to write a research paper

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

With proper planning, knowledge, and framework, completing a research paper can be a fulfilling and exciting experience.

Though it might initially sound slightly intimidating, this guide will help you embrace the challenge.

By documenting your findings, you can inspire others and make a difference in your field. Here's how you can make your research paper unique and comprehensive.

- What is a research paper?

Research papers allow you to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a particular topic. These papers are usually lengthier and more detailed than typical essays, requiring deeper insight into the chosen topic.

To write a research paper, you must first choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field of study. Once you’ve selected your topic, gathering as many relevant resources as possible, including books, scholarly articles, credible websites, and other academic materials, is essential. You must then read and analyze these sources, summarizing their key points and identifying gaps in the current research.

You can formulate your ideas and opinions once you thoroughly understand the existing research. To get there might involve conducting original research, gathering data, or analyzing existing data sets. It could also involve presenting an original argument or interpretation of the existing research.

Writing a successful research paper involves presenting your findings clearly and engagingly, which might involve using charts, graphs, or other visual aids to present your data and using concise language to explain your findings. You must also ensure your paper adheres to relevant academic formatting guidelines, including proper citations and references.

Overall, writing a research paper requires a significant amount of time, effort, and attention to detail. However, it is also an enriching experience that allows you to delve deeply into a subject that interests you and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in your chosen field.

- How long should a research paper be?

Research papers are deep dives into a topic. Therefore, they tend to be longer pieces of work than essays or opinion pieces.

However, a suitable length depends on the complexity of the topic and your level of expertise. For instance, are you a first-year college student or an experienced professional?

Also, remember that the best research papers provide valuable information for the benefit of others. Therefore, the quality of information matters most, not necessarily the length. Being concise is valuable.

Following these best practice steps will help keep your process simple and productive:

1. Gaining a deep understanding of any expectations

Before diving into your intended topic or beginning the research phase, take some time to orient yourself. Suppose there’s a specific topic assigned to you. In that case, it’s essential to deeply understand the question and organize your planning and approach in response. Pay attention to the key requirements and ensure you align your writing accordingly.

This preparation step entails

Deeply understanding the task or assignment

Being clear about the expected format and length

Familiarizing yourself with the citation and referencing requirements

Understanding any defined limits for your research contribution

Where applicable, speaking to your professor or research supervisor for further clarification

2. Choose your research topic

Select a research topic that aligns with both your interests and available resources. Ideally, focus on a field where you possess significant experience and analytical skills. In crafting your research paper, it's crucial to go beyond summarizing existing data and contribute fresh insights to the chosen area.

Consider narrowing your focus to a specific aspect of the topic. For example, if exploring the link between technology and mental health, delve into how social media use during the pandemic impacts the well-being of college students. Conducting interviews and surveys with students could provide firsthand data and unique perspectives, adding substantial value to the existing knowledge.

When finalizing your topic, adhere to legal and ethical norms in the relevant area (this ensures the integrity of your research, protects participants' rights, upholds intellectual property standards, and ensures transparency and accountability). Following these principles not only maintains the credibility of your work but also builds trust within your academic or professional community.

For instance, in writing about medical research, consider legal and ethical norms , including patient confidentiality laws and informed consent requirements. Similarly, if analyzing user data on social media platforms, be mindful of data privacy regulations, ensuring compliance with laws governing personal information collection and use. Aligning with legal and ethical standards not only avoids potential issues but also underscores the responsible conduct of your research.

3. Gather preliminary research

Once you’ve landed on your topic, it’s time to explore it further. You’ll want to discover more about available resources and existing research relevant to your assignment at this stage.

This exploratory phase is vital as you may discover issues with your original idea or realize you have insufficient resources to explore the topic effectively. This key bit of groundwork allows you to redirect your research topic in a different, more feasible, or more relevant direction if necessary.

Spending ample time at this stage ensures you gather everything you need, learn as much as you can about the topic, and discover gaps where the topic has yet to be sufficiently covered, offering an opportunity to research it further.

4. Define your research question

To produce a well-structured and focused paper, it is imperative to formulate a clear and precise research question that will guide your work. Your research question must be informed by the existing literature and tailored to the scope and objectives of your project. By refining your focus, you can produce a thoughtful and engaging paper that effectively communicates your ideas to your readers.

5. Write a thesis statement

A thesis statement is a one-to-two-sentence summary of your research paper's main argument or direction. It serves as an overall guide to summarize the overall intent of the research paper for you and anyone wanting to know more about the research.

A strong thesis statement is:

Concise and clear: Explain your case in simple sentences (avoid covering multiple ideas). It might help to think of this section as an elevator pitch.

Specific: Ensure that there is no ambiguity in your statement and that your summary covers the points argued in the paper.

Debatable: A thesis statement puts forward a specific argument––it is not merely a statement but a debatable point that can be analyzed and discussed.

Here are three thesis statement examples from different disciplines:

Psychology thesis example: "We're studying adults aged 25-40 to see if taking short breaks for mindfulness can help with stress. Our goal is to find practical ways to manage anxiety better."

Environmental science thesis example: "This research paper looks into how having more city parks might make the air cleaner and keep people healthier. I want to find out if more green spaces means breathing fewer carcinogens in big cities."

UX research thesis example: "This study focuses on improving mobile banking for older adults using ethnographic research, eye-tracking analysis, and interactive prototyping. We investigate the usefulness of eye-tracking analysis with older individuals, aiming to spark debate and offer fresh perspectives on UX design and digital inclusivity for the aging population."

6. Conduct in-depth research

A research paper doesn’t just include research that you’ve uncovered from other papers and studies but your fresh insights, too. You will seek to become an expert on your topic––understanding the nuances in the current leading theories. You will analyze existing research and add your thinking and discoveries. It's crucial to conduct well-designed research that is rigorous, robust, and based on reliable sources. Suppose a research paper lacks evidence or is biased. In that case, it won't benefit the academic community or the general public. Therefore, examining the topic thoroughly and furthering its understanding through high-quality research is essential. That usually means conducting new research. Depending on the area under investigation, you may conduct surveys, interviews, diary studies , or observational research to uncover new insights or bolster current claims.

7. Determine supporting evidence

Not every piece of research you’ve discovered will be relevant to your research paper. It’s important to categorize the most meaningful evidence to include alongside your discoveries. It's important to include evidence that doesn't support your claims to avoid exclusion bias and ensure a fair research paper.

8. Write a research paper outline

Before diving in and writing the whole paper, start with an outline. It will help you to see if more research is needed, and it will provide a framework by which to write a more compelling paper. Your supervisor may even request an outline to approve before beginning to write the first draft of the full paper. An outline will include your topic, thesis statement, key headings, short summaries of the research, and your arguments.

9. Write your first draft

Once you feel confident about your outline and sources, it’s time to write your first draft. While penning a long piece of content can be intimidating, if you’ve laid the groundwork, you will have a structure to help you move steadily through each section. To keep up motivation and inspiration, it’s often best to keep the pace quick. Stopping for long periods can interrupt your flow and make jumping back in harder than writing when things are fresh in your mind.

10. Cite your sources correctly

It's always a good practice to give credit where it's due, and the same goes for citing any works that have influenced your paper. Building your arguments on credible references adds value and authenticity to your research. In the formatting guidelines section, you’ll find an overview of different citation styles (MLA, CMOS, or APA), which will help you meet any publishing or academic requirements and strengthen your paper's credibility. It is essential to follow the guidelines provided by your school or the publication you are submitting to ensure the accuracy and relevance of your citations.

11. Ensure your work is original

It is crucial to ensure the originality of your paper, as plagiarism can lead to serious consequences. To avoid plagiarism, you should use proper paraphrasing and quoting techniques. Paraphrasing is rewriting a text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. Quoting involves directly citing the source. Giving credit to the original author or source is essential whenever you borrow their ideas or words. You can also use plagiarism detection tools such as Scribbr or Grammarly to check the originality of your paper. These tools compare your draft writing to a vast database of online sources. If you find any accidental plagiarism, you should correct it immediately by rephrasing or citing the source.

12. Revise, edit, and proofread

One of the essential qualities of excellent writers is their ability to understand the importance of editing and proofreading. Even though it's tempting to call it a day once you've finished your writing, editing your work can significantly improve its quality. It's natural to overlook the weaker areas when you've just finished writing a paper. Therefore, it's best to take a break of a day or two, or even up to a week, to refresh your mind. This way, you can return to your work with a new perspective. After some breathing room, you can spot any inconsistencies, spelling and grammar errors, typos, or missing citations and correct them.

- The best research paper format

The format of your research paper should align with the requirements set forth by your college, school, or target publication.

There is no one “best” format, per se. Depending on the stated requirements, you may need to include the following elements:

Title page: The title page of a research paper typically includes the title, author's name, and institutional affiliation and may include additional information such as a course name or instructor's name.

Table of contents: Include a table of contents to make it easy for readers to find specific sections of your paper.

Abstract: The abstract is a summary of the purpose of the paper.

Methods : In this section, describe the research methods used. This may include collecting data , conducting interviews, or doing field research .

Results: Summarize the conclusions you drew from your research in this section.

Discussion: In this section, discuss the implications of your research . Be sure to mention any significant limitations to your approach and suggest areas for further research.

Tables, charts, and illustrations: Use tables, charts, and illustrations to help convey your research findings and make them easier to understand.

Works cited or reference page: Include a works cited or reference page to give credit to the sources that you used to conduct your research.

Bibliography: Provide a list of all the sources you consulted while conducting your research.

Dedication and acknowledgments : Optionally, you may include a dedication and acknowledgments section to thank individuals who helped you with your research.

- General style and formatting guidelines

Formatting your research paper means you can submit it to your college, journal, or other publications in compliance with their criteria.

Research papers tend to follow the American Psychological Association (APA), Modern Language Association (MLA), or Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) guidelines.

Here’s how each style guide is typically used:

Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS):

CMOS is a versatile style guide used for various types of writing. It's known for its flexibility and use in the humanities. CMOS provides guidelines for citations, formatting, and overall writing style. It allows for both footnotes and in-text citations, giving writers options based on their preferences or publication requirements.

American Psychological Association (APA):

APA is common in the social sciences. It’s hailed for its clarity and emphasis on precision. It has specific rules for citing sources, creating references, and formatting papers. APA style uses in-text citations with an accompanying reference list. It's designed to convey information efficiently and is widely used in academic and scientific writing.

Modern Language Association (MLA):

MLA is widely used in the humanities, especially literature and language studies. It emphasizes the author-page format for in-text citations and provides guidelines for creating a "Works Cited" page. MLA is known for its focus on the author's name and the literary works cited. It’s frequently used in disciplines that prioritize literary analysis and critical thinking.

To confirm you're using the latest style guide, check the official website or publisher's site for updates, consult academic resources, and verify the guide's publication date. Online platforms and educational resources may also provide summaries and alerts about any revisions or additions to the style guide.

Citing sources

When working on your research paper, it's important to cite the sources you used properly. Your citation style will guide you through this process. Generally, there are three parts to citing sources in your research paper:

First, provide a brief citation in the body of your essay. This is also known as a parenthetical or in-text citation.

Second, include a full citation in the Reference list at the end of your paper. Different types of citations include in-text citations, footnotes, and reference lists.

In-text citations include the author's surname and the date of the citation.

Footnotes appear at the bottom of each page of your research paper. They may also be summarized within a reference list at the end of the paper.

A reference list includes all of the research used within the paper at the end of the document. It should include the author, date, paper title, and publisher listed in the order that aligns with your citation style.

10 research paper writing tips:

Following some best practices is essential to writing a research paper that contributes to your field of study and creates a positive impact.

These tactics will help you structure your argument effectively and ensure your work benefits others:

Clear and precise language: Ensure your language is unambiguous. Use academic language appropriately, but keep it simple. Also, provide clear takeaways for your audience.

Effective idea separation: Organize the vast amount of information and sources in your paper with paragraphs and titles. Create easily digestible sections for your readers to navigate through.

Compelling intro: Craft an engaging introduction that captures your reader's interest. Hook your audience and motivate them to continue reading.

Thorough revision and editing: Take the time to review and edit your paper comprehensively. Use tools like Grammarly to detect and correct small, overlooked errors.

Thesis precision: Develop a clear and concise thesis statement that guides your paper. Ensure that your thesis aligns with your research's overall purpose and contribution.

Logical flow of ideas: Maintain a logical progression throughout the paper. Use transitions effectively to connect different sections and maintain coherence.

Critical evaluation of sources: Evaluate and critically assess the relevance and reliability of your sources. Ensure that your research is based on credible and up-to-date information.

Thematic consistency: Maintain a consistent theme throughout the paper. Ensure that all sections contribute cohesively to the overall argument.

Relevant supporting evidence: Provide concise and relevant evidence to support your arguments. Avoid unnecessary details that may distract from the main points.

Embrace counterarguments: Acknowledge and address opposing views to strengthen your position. Show that you have considered alternative arguments in your field.

7 research tips

If you want your paper to not only be well-written but also contribute to the progress of human knowledge, consider these tips to take your paper to the next level:

Selecting the appropriate topic: The topic you select should align with your area of expertise, comply with the requirements of your project, and have sufficient resources for a comprehensive investigation.

Use academic databases: Academic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and JSTOR offer a wealth of research papers that can help you discover everything you need to know about your chosen topic.

Critically evaluate sources: It is important not to accept research findings at face value. Instead, it is crucial to critically analyze the information to avoid jumping to conclusions or overlooking important details. A well-written research paper requires a critical analysis with thorough reasoning to support claims.

Diversify your sources: Expand your research horizons by exploring a variety of sources beyond the standard databases. Utilize books, conference proceedings, and interviews to gather diverse perspectives and enrich your understanding of the topic.

Take detailed notes: Detailed note-taking is crucial during research and can help you form the outline and body of your paper.

Stay up on trends: Keep abreast of the latest developments in your field by regularly checking for recent publications. Subscribe to newsletters, follow relevant journals, and attend conferences to stay informed about emerging trends and advancements.

Engage in peer review: Seek feedback from peers or mentors to ensure the rigor and validity of your research . Peer review helps identify potential weaknesses in your methodology and strengthens the overall credibility of your findings.

- The real-world impact of research papers

Writing a research paper is more than an academic or business exercise. The experience provides an opportunity to explore a subject in-depth, broaden one's understanding, and arrive at meaningful conclusions. With careful planning, dedication, and hard work, writing a research paper can be a fulfilling and enriching experience contributing to advancing knowledge.

How do I publish my research paper?

Many academics wish to publish their research papers. While challenging, your paper might get traction if it covers new and well-written information. To publish your research paper, find a target publication, thoroughly read their guidelines, format your paper accordingly, and send it to them per their instructions. You may need to include a cover letter, too. After submission, your paper may be peer-reviewed by experts to assess its legitimacy, quality, originality, and methodology. Following review, you will be informed by the publication whether they have accepted or rejected your paper.

What is a good opening sentence for a research paper?

Beginning your research paper with a compelling introduction can ensure readers are interested in going further. A relevant quote, a compelling statistic, or a bold argument can start the paper and hook your reader. Remember, though, that the most important aspect of a research paper is the quality of the information––not necessarily your ability to storytell, so ensure anything you write aligns with your goals.

Research paper vs. a research proposal—what’s the difference?

While some may confuse research papers and proposals, they are different documents.

A research proposal comes before a research paper. It is a detailed document that outlines an intended area of exploration. It includes the research topic, methodology, timeline, sources, and potential conclusions. Research proposals are often required when seeking approval to conduct research.

A research paper is a summary of research findings. A research paper follows a structured format to present those findings and construct an argument or conclusion.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

- 10 research paper

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Research Paper

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Research Paper

There will come a time in most students' careers when they are assigned a research paper. Such an assignment often creates a great deal of unneeded anxiety in the student, which may result in procrastination and a feeling of confusion and inadequacy. This anxiety frequently stems from the fact that many students are unfamiliar and inexperienced with this genre of writing. Never fear—inexperience and unfamiliarity are situations you can change through practice! Writing a research paper is an essential aspect of academics and should not be avoided on account of one's anxiety. In fact, the process of writing a research paper can be one of the more rewarding experiences one may encounter in academics. What is more, many students will continue to do research throughout their careers, which is one of the reasons this topic is so important.

Becoming an experienced researcher and writer in any field or discipline takes a great deal of practice. There are few individuals for whom this process comes naturally. Remember, even the most seasoned academic veterans have had to learn how to write a research paper at some point in their career. Therefore, with diligence, organization, practice, a willingness to learn (and to make mistakes!), and, perhaps most important of all, patience, students will find that they can achieve great things through their research and writing.

The pages in this section cover the following topic areas related to the process of writing a research paper:

- Genre - This section will provide an overview for understanding the difference between an analytical and argumentative research paper.

- Choosing a Topic - This section will guide the student through the process of choosing topics, whether the topic be one that is assigned or one that the student chooses themselves.

- Identifying an Audience - This section will help the student understand the often times confusing topic of audience by offering some basic guidelines for the process.

- Where Do I Begin - This section concludes the handout by offering several links to resources at Purdue, and also provides an overview of the final stages of writing a research paper.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Writing your research paper

How to start your research paper [step-by-step guide]

All research papers have pretty much the same structure. If you can write one type of research paper, you can write another. Learn the steps to start and complete your research paper in our guide.

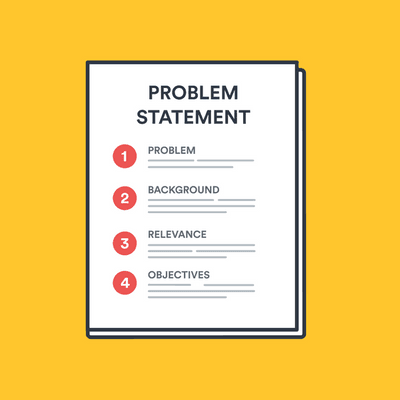

How to write a problem statement

What is a problem statement and how do you write one? This guide answers all your questions and includes an example of a problem statement.

How to write a research paper outline

Structuring the outline of your research paper early on is important. Read on to learn how to structure a research paper outline and to see examples, including an outline template.

How to write a research proposal

What is a research proposal and what should you use it for? This step-by-step guide teaches you how to structure and write a research proposal.

How to write an abstract

Not sure how to write an abstract for your paper? Clear your doubts with this guide, follow our tips, and start writing your abstract!

What are the different types of research papers?

Learn all you need to know about research papers, what differentiates a research paper from a thesis, and what types of research papers there are.

What is a research paper?

Are you confused about what a research paper actually is and what differentiates it from a thesis? Clarify it once and for all with our guide.

What is an appendix in a paper

Not sure what an appendix in a paper is? This guides defines what an appendix is and how to format one.

What is the abstract of a paper?

Not sure what the abstract of a paper is? Learn the definition of an abstract and how to format one in this guide with resources.

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

How to Write a Research Paper

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Research Paper Fundamentals

How to choose a topic or question, how to create a working hypothesis or thesis, common research paper methodologies, how to gather and organize evidence , how to write an outline for your research paper, how to write a rough draft, how to revise your draft, how to produce a final draft, resources for teachers .

It is not fair to say that no one writes anymore. Just about everyone writes text messages, brief emails, or social media posts every single day. Yet, most people don't have a lot of practice with the formal, organized writing required for a good academic research paper. This guide contains links to a variety of resources that can help demystify the process. Some of these resources are intended for teachers; they contain exercises, activities, and teaching strategies. Other resources are intended for direct use by students who are struggling to write papers, or are looking for tips to make the process go more smoothly.

The resources in this section are designed to help students understand the different types of research papers, the general research process, and how to manage their time. Below, you'll find links from university writing centers, the trusted Purdue Online Writing Lab, and more.

What is an Academic Research Paper?

"Genre and the Research Paper" (Purdue OWL)

There are different types of research papers. Different types of scholarly questions will lend themselves to one format or another. This is a brief introduction to the two main genres of research paper: analytic and argumentative.

"7 Most Popular Types of Research Papers" (Personal-writer.com)

This resource discusses formats that high school students commonly encounter, such as the compare and contrast essay and the definitional essay. Please note that the inclusion of this link is not an endorsement of this company's paid service.

How to Prepare and Plan Out Writing a Research Paper

Teachers can give their students a step-by-step guide like these to help them understand the different steps of the research paper process. These guides can be combined with the time management tools in the next subsection to help students come up with customized calendars for completing their papers.

"Ten Steps for Writing Research Papers" (American University)

This resource from American University is a comprehensive guide to the research paper writing process, and includes examples of proper research questions and thesis topics.

"Steps in Writing a Research Paper" (SUNY Empire State College)

This guide breaks the research paper process into 11 steps. Each "step" links to a separate page, which describes the work entailed in completing it.

How to Manage Time Effectively

The links below will help students determine how much time is necessary to complete a paper. If your sources are not available online or at your local library, you'll need to leave extra time for the Interlibrary Loan process. Remember that, even if you do not need to consult secondary sources, you'll still need to leave yourself ample time to organize your thoughts.

"Research Paper Planner: Timeline" (Baylor University)

This interactive resource from Baylor University creates a suggested writing schedule based on how much time a student has to work on the assignment.

"Research Paper Planner" (UCLA)

UCLA's library offers this step-by-step guide to the research paper writing process, which also includes a suggested planning calendar.

There's a reason teachers spend a long time talking about choosing a good topic. Without a good topic and a well-formulated research question, it is almost impossible to write a clear and organized paper. The resources below will help you generate ideas and formulate precise questions.

"How to Select a Research Topic" (Univ. of Michigan-Flint)

This resource is designed for college students who are struggling to come up with an appropriate topic. A student who uses this resource and still feels unsure about his or her topic should consult the course instructor for further personalized assistance.

"25 Interesting Research Paper Topics to Get You Started" (Kibin)

This resource, which is probably most appropriate for high school students, provides a list of specific topics to help get students started. It is broken into subsections, such as "paper topics on local issues."

"Writing a Good Research Question" (Grand Canyon University)

This introduction to research questions includes some embedded videos, as well as links to scholarly articles on research questions. This resource would be most appropriate for teachers who are planning lessons on research paper fundamentals.

"How to Write a Research Question the Right Way" (Kibin)

This student-focused resource provides more detail on writing research questions. The language is accessible, and there are embedded videos and examples of good and bad questions.

It is important to have a rough hypothesis or thesis in mind at the beginning of the research process. People who have a sense of what they want to say will have an easier time sorting through scholarly sources and other information. The key, of course, is not to become too wedded to the draft hypothesis or thesis. Just about every working thesis gets changed during the research process.

CrashCourse Video: "Sociology Research Methods" (YouTube)

Although this video is tailored to sociology students, it is applicable to students in a variety of social science disciplines. This video does a good job demonstrating the connection between the brainstorming that goes into selecting a research question and the formulation of a working hypothesis.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Analytical Essay" (YouTube)

Students writing analytical essays will not develop the same type of working hypothesis as students who are writing research papers in other disciplines. For these students, developing the working thesis may happen as a part of the rough draft (see the relevant section below).

"Research Hypothesis" (Oakland Univ.)