Recommended pages

- Undergraduate open days

- Postgraduate open days

- Accommodation

- Information for teachers

- Maps and directions

- Sport and fitness

The ethics of warfare: Is it ever morally right to kill on a massive scale

War has been puzzling philosophers for centuries, and it isn’t hard to see why. What could be more intuitive or ethical than the belief that it is morally wrong to kill on a massive scale?

However, many would argue that there are times when war is morally permissible, and even obligatory. The most famous way of ethically assessing war is to use ‘Just War Theory’; a tradition going back to St. Augustine in the 5th Century and St. Thomas in the 13th Century. Just War theory considers the reasons for going to war (Jus ad bellum) and the conduct of war (Jus in bello). This distinction is important. A war might be ethical but the means unethical, for instance, using landmines, torture, chemicals and current debate is concerned with drones.

Just War theory sets out principles for a war to be ethical. The war must be:

- Waged by a legitimate authority (usually interpreted as states)

- In a just cause

- Waged with right intention

- Have a strong probability of success

- Be a last resort

- Be proportional

In addition, there are three principles for conduct in war:

- Discrimination (distinguishing between enemy combatants and non-combatants)

- Proportionality (the harms must be proportional to the gains)

- Actions must be militarily necessary

When attempting to apply and interpret these principles considerable disagreement arises, as evidenced by the – still ongoing – debate about the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq. Just war principles are used to address the question of whether the war lacked legitimate authority without a UN Resolution.

Legitimate authority is at issue in all conflicts, including those considered to be acts of terrorism or insurgency. Think about recent uprisings such as the 2011 ousting of Gaddafi's regime in Libya and the other movements loosely termed the Arab Spring; and most timely the current debate about whether to arm the ‘rebels’ in Syria. Are these legitimate authorities? And does legitimate authority make sense anymore?

Establishing ‘just cause’ is also problematic, for example, self-defence is widely recognised, and the UN Charter grants states a right to defend themselves. However, other ‘just causes’ are more difficult to defend. Particularly controversial is humanitarian intervention, even though it is sometimes seen as obligatory and indeed, the most ethical reason for war. It was for humanitarian reasons that NATO intervened in Kosovo in 1999, but, there are other instances where humanitarian disasters are left (perhaps most controversially the failure to intervene in the Rwandan genocide in 1994).

All criteria are problematic and hard to meet. Think about ‘right intention’ with regard to the 2003 Iraq war and discussions about the ‘real’ motives of Bush and Blair. And when we come to proportionality, the contemporary debate is particularly fraught. Can it ever be proportional to use drones where there is no risk to life on one side and risk to many lives (including civilian lives) on the other? And when battles are fought in villages and homes by those with no uniforms, how can the principle of discrimination ever be respected – and indeed should it be?

The character of war is changing fast and the ethics needs to keep pace with that change. These particular principles might well need revision. But we should not imagine the fundamental ethical issues have changed. It is still the case that in a sense war is inherently unethical. To be justified, significant ethical reasons are required and although imperfect Just War theory continues to be one way to seek such reasons.

Heather Widdows, Professor of Global Ethics, Department of Philosophy, Co-Leader of Saving Humans IAS theme

Home — Essay Samples — Science — Rat — Is War Justified? An Examination of Ethical and Pragmatic Considerations

Is War Justified? an Examination of Ethical and Pragmatic Considerations

- Categories: Rat

About this sample

Words: 766 |

Published: Jun 13, 2024

Words: 766 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, body paragraph 1: ethical considerations, body paragraph 2: legal and political dimensions, body paragraph 3: pragmatic considerations.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Science

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 388 words

1 pages / 499 words

1 pages / 564 words

5 pages / 2147 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Rat

Hunger, a condition characterized by a severe lack of food, is a pervasive issue that affects millions of individuals worldwide. Despite global advancements in agriculture, technology, and economic development, hunger remains a [...]

Island hopping, a term often associated with military strategy in the Pacific Theater during World War II, also encapsulates a broader narrative of exploration, cultural exchange, and ecological impact. The concept involves [...]

Advanced literature, encompassing classical texts, modernist works, and postmodern narratives, holds a pivotal place in the educational, cultural, and intellectual spheres of society. It serves not only as a repository of human [...]

Hair is more than just a physical attribute; it is a symbol of identity, culture, and personal expression. The journey with my hair has been a compelling narrative that intertwines with my growth, self-perception, and [...]

Templeton the Rat is a character from E.B. White's beloved children's book, "Charlotte's Web." While often overshadowed by the more famous characters of Charlotte the spider and Wilbur the pig, Templeton plays a crucial role in [...]

Naguib Mahfouz, a pioneering Arabic author, expresses his frustration with government through themes of individual freedoms in society and the ineffectiveness of government within his short story, The Norwegian Rat. Born on [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Senior Fellows

- Research Fellows

- Submission Guidelines

- Media Inquiries

- Commentary & Analysis

Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- October 2021 War Studies Conference

- November 2020 War Studies Conference

- November 2018 War Studies Conference

- March 2018 War Studies Conference

- November 2016 War Studies Conference

- Class of 1974 MWI Podcast

- Urban Warfare Project Podcast

- Social Science of War

- Urban Warfare Project

- Project 6633

- Shield Notes

- Rethinking Civ-Mil

- Book Reviews

Select Page

Does the “Good Fight” Exist? Ethics and the Future of War

Nicholas Romanow | 04.07.22

Samuel Moyn, Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War (Macmillan, 2021)

Can a “humane” war ever be fought? Or is such a question doomed to irrelevance by an innate contradiction in its terms? These are two of the driving questions in Samuel Moyn’s Humane , a polemic against the US-led march into an era of endless war.

Moyn’s exploration of these question leads him to conclude, in part, that efforts to make warfighting more ethical and less cruel have in turn made war more common and long-lasting. Moyn also sets his sights on the military establishment, castigating it for a long succession of abuses, cover-ups, and manipulations. Published as the US military continues its transition from the post-9/11 wars to an era of great power competition, Moyn’s book is a thought-provoking reflection on the evolution of ethical and legal considerations in the use of military force. Still, it poorly anticipates the ethical dilemmas that military officers will face today and tomorrow.

Moyn’s central thesis (while seemingly paradoxical) is relatively intuitive. If war becomes less brutal, both decision makers and the public will raise fewer objections to going to war. If fewer people object to war, then wars will become easier to initiate and harder to terminate. Moyn traces this logic from the nineteenth century, through both world wars and the Cold War, and into the post–Cold War period. He highlights a fissure that emerged between peace advocates who oppose war of any kind, for any reason, and humanitarians who work to mitigate the worst effects of inevitable conflict. In effect, Moyn suggests, the efforts of the humanitarian camp actually contribute to making war more likely by reducing some of the most catastrophic impacts of war.

Throughout the book, Moyn maintains a caustic tone directed at those who have strived to constrain the use of force and hold the military to a high standard of accountability and self-control. This derision is off-putting for junior officers who hold their military mentors, and their efforts to apply violence in ways that limit any unnecessary harm, in high esteem. In his memoir, Call Sign Chaos , retired General and former Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis wrote that “the need for lethality must be the measuring stick against which we evaluate the efficacy of our military.” Yet in the very same book, he observed that “rules of engagement are what separate principled militaries from barbarians and terrorists.” Moyn dismisses concepts such as strict rules of engagement and civilian casualty reporting as mere public relations tactics the military uses to avoid bad press.

The refinement of military ethics is a task without end; as long as war causes unnecessary damage and suffering, the task can and must continue. But the author overlooks ongoing efforts within the joint force to develop, refine, and enforce a robust set of military ethics—a defining feature of the military as a profession. Mentors and role models who embrace and pass on this professional obligation help establish a virtuous cycle where, at its best, each generation of new officers is cultivated to hold itself to an ever higher standard.

Consider such unforgivable abuses of military force such as the treatment of detainees at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. This episode and those like it are rightfully remembered as scandals in American military history. That’s why it’s important that they remain well-discussed, not just in American public discourse but in professional military education, as well. These are exceptions rather than the rule in American military affairs—unacceptable exceptions, but exceptions nonetheless. Efforts to ensure these cases are not only remembered institutionally within the military, but used to develop ethical leaders, are therefore vital. Black Hearts —a book about the brutal rape of an Iraqi girl and murder of her family by US soldiers—is required reading for every West Point cadet and a case study based on it forms the centerpiece of the academy’s capstone officership course. This and other efforts to develop ethical leaders matters in ways Moyn’s book fails to recognize.

The military justice system enshrined in the Uniform Code of Military Justice and upheld by the judge advocate general’s corps in every service is not just a publicity stunt. Rather, the concept of legality in warfighting is integrated in the daily routines of every servicemember. Conducting military operations ethically, morally, and legally is not an afterthought meant to massage the military’s public image. For junior officers who have recently completed their indoctrination training, including the wide range of legal briefings this entails, the implication that for a professional military the law of armed conflict is simply a farce does not align with actual experiences.

Moyn’s book was published last fall, within days of the withdrawal of US and allied forces from Afghanistan. But its analysis ends with the post-9/11 wars and counterterrorism mission, which are presented as an example of a dystopian end state wherein hyper-precise strike warfare against high-value targets has allowed the military to morph into some kind of global police force. This is a worthy discussion, but only part of a complete and current one, which limits its utility. There is no discussion on the impacts on military ethics of the raging debate in security circles on strategic competition, gray zone conflict, or the Thucydides Trap and tensions between the United States and China. While counterterrorism operations, stability operations, and irregular warfare will persist, these are no longer the raison d’etre for the armed services in the way they were for the better part of the previous two decades. Instead, competing in ambiguous situations that sit in the challenging middle ground between armed conflict and peace will require leaders who can confront murky ethical conundrums. Today’s officers can learn from the moral shortcomings that Moyn chronicles, but they must do so while deliberately planning for the challenges ahead.

This is the key for military readers of Humane , especially junior officers who will spend the years and even decades to come confronting new ethical challenges. Exploring whether wars can ever be fought humanely is a worthy endeavor. Tracing efforts to do so—and questioning whether they unintentionally expand the likelihood of war—is equally so. One of Moyn’s central contentions—that technology reduces risks in ways that can prolong wars—is convincing, at least to a degree. The use of unmanned aerial vehicles seems to have finally defeated General William T. Sherman’s adage that “every attempt to make war easy and safe will result in humiliation and disaster.” Strikes by unmanned platforms controlled by aviators sometimes thousands of miles away have virtually eliminated the risk associated with manned aircraft missions, enabling such operations to continue in perpetuity because public resistance to military activity is most often tied to the casualties of American servicemembers. However, members of the military profession cannot reach that conclusion and stop there, but must look forward to future ethical challenges. As drone use proliferates globally, it is possible that this technology will one day be used against American servicemembers, either by an adversarial state or a terrorist group. How do the ethics of unmanned platforms—their development, what weapons they carry, whether artificial intelligence can and should be incorporated into them, and ultimately their employment—change in such a shifting environment?

Technology is an important motif throughout the book, especially its role shaping the laws and ethics of war. The advent of aerial bombardment and nuclear weapons made warfare far more destructive long before it became more precise. This history, which Moyn charts well, should inform ongoing debates over whether autonomous weapons, digital technology, and other emerging advances will pull warfare in the direction of more precision or more destruction.

No domain of warfare is as inadequately covered by the current body of law governing conflict as the domain of cyber. The deniability of cyberattacks allows them to skirt the traditional dichotomy of jus ad bellum and jus in bello . Cyberattacks may be referred to as acts of war in policy discourse, but no cyberattack has escalated into a full-blown war. Meanwhile, many cyberattacks occur in the absence of a state of war, such as last year’s Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack . Attacks like these also blatantly violate noncombatant immunity and often target critical infrastructure or private firms. Cyberattacks can also be perpetrated for a variety of purposes other than mere destruction, such as for espionage, extortion, or terrorism.

At the same time, we have yet to experience the “ cyber Pearl Harbor ” that would prove that a cyber weapon can be used to inflict casualties on an enemy. Despite the abundance of ink spilled on enshrining cyber norms and the need for a “ Digital Geneva Convention ,” cyberspace remains an unregulated battleground. While events like the Colonial Pipeline attack prove the possible effects of a coordinated cyber offensive, there are no clear boundaries on how far such a campaign may go before it is considered an overt act of war. At what point will cyberattacks trigger kinetic responses? How much certainty in the hacker’s identity will be needed to justify a response? Will the United States and other major powers accept constraints on their own cyber capabilities to avoid more and more devastating attacks? Is it even possible for these constraints to be enforced and verified? Perhaps both the legal aspects and the ethics of cyberwarfare were beyond the scope of Moyn’s book, but military professionals have no choice but to contend with these issues.

Moyn’s work is a thoroughly researched piece of intellectual history. Junior military professionals should read Humane and will find it useful, but should consider the ways in which the book’s utility is limited. Ultimately, they should take away from it a reinvigorated commitment to confronting head on the arduous ethical and moral dilemmas that a military officer will undoubtedly face throughout his or her career.

Ensign Nicholas Romanow ( @nickromanow ) is a cryptologic warfare officer in the US Navy stationed in the Washington, DC area. He holds a BA in international relations and global studies from the University of Texas at Austin, where he was also an undergraduate fellow at the Clements Center for National Security.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense., or that of any organization the author is affiliated with, including the United States Navy.

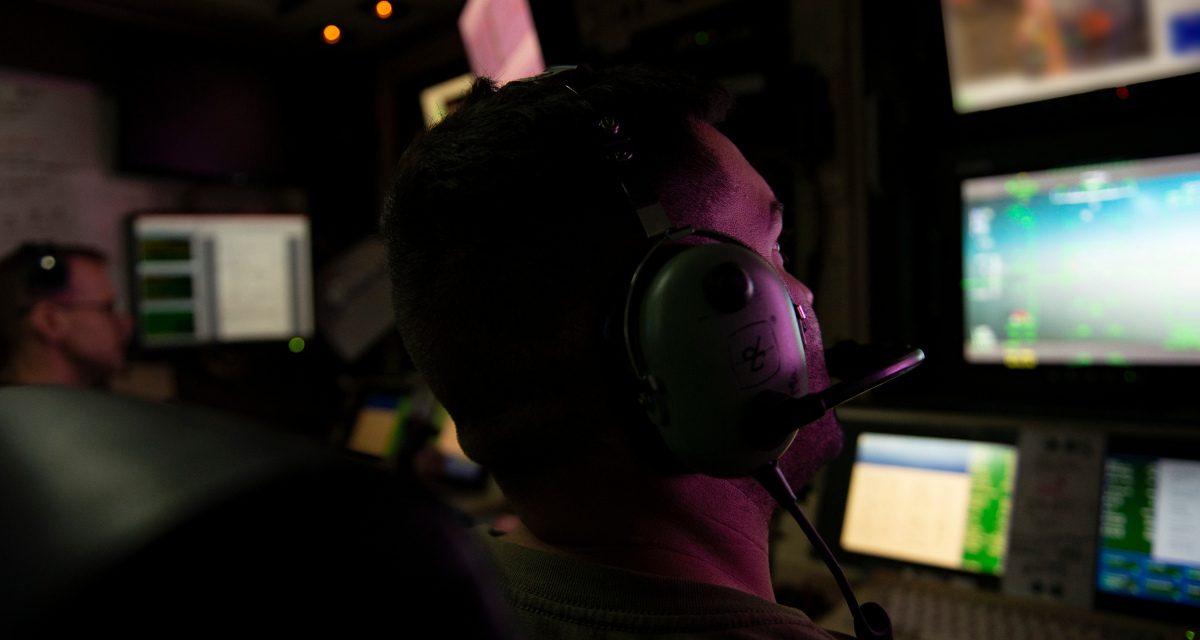

Image credit: Senior Airman Helena Owens, US Air Force

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The articles and other content which appear on the Modern War Institute website are unofficial expressions of opinion. The views expressed are those of the authors, and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

The Modern War Institute does not screen articles to fit a particular editorial agenda, nor endorse or advocate material that is published. Rather, the Modern War Institute provides a forum for professionals to share opinions and cultivate ideas. Comments will be moderated before posting to ensure logical, professional, and courteous application to article content.

Announcements

- Announcing the Modern War Institute’s 2024–2025 Research Fellows

- We’re Looking for Officers to Join the Modern War Institute and the Defense and Strategic Studies Program!

- Call for Applications: MWI’s 2024–25 Research Fellows Program

- Join Us Friday, April 26 for a Livestream of the 2024 Hagel Lecture, Featuring Secretary Chuck Hagel and Secretary Jeh Johnson

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Despite its prevalence throughout history, war is a phenomenon that should never be considered morally or ethically justifiable. In this essay, I shall explore the ethical and practical...

If the outcome of war brings more good than harm, war can be justified; even if the actual reason for war is not a morally acceptable one. Anything that, on a worldwide scale, improves the quality of life for the majority is acceptable.

War has been puzzling philosophers for centuries, and it isn’t hard to see why. What could be more intuitive or ethical than the belief that it is morally wrong to kill on a massive scale? However, many would argue that there are times when war is morally permissible, and even obligatory.

According to Just War Theory, war can be justified if it meets certain conditions such as having a just cause, being declared by a legitimate authority, possessing the right intention, and being a last resort.

Both just war theory and the law distinguished between the justification for the resort to war (jus ad bellum) and justified conduct in war (jus in bello). In most presentations of the theory of the just war there are six principles of jus ad bellum, each with its own label: just cause,

Can war ever be morally justifiable? Defining what war is requires determining the entities that are allowed to begin and engage in war. And a person’s definition of war often expresses the person’s broader political philosophy, such as limiting war to a conflict between nations or state.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine brings up a vexing philosophical question: when is war morally defensible? A small but ancient part of political philosophy is known as “just war theory.”

A just war must be fought only as self-defense against armed attack or to redress a wrong; There must be a reasonable chance of success; deaths and injury that result from a hopeless cause cannot be morally justified; The consequences of the war must be better than the situation that would exist had the war not taken place;

Can war be justified? For those who spend their lives working to prevent and end wars, whether and how war itself can be justified must be an urgent question.

Can a “humane” war ever be fought? Or is such a question doomed to irrelevance by an innate contradiction in its terms? These are two of the driving questions in Samuel Moyn’s Humane, a polemic against the US-led march into an era of endless war.