How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 5 min read

Using the Scientific Method to Solve Problems

How the scientific method and reasoning can help simplify processes and solve problems.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

The processes of problem-solving and decision-making can be complicated and drawn out. In this article we look at how the scientific method, along with deductive and inductive reasoning can help simplify these processes.

‘It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has information. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit our theories, instead of theories to suit facts.’ Sherlock Holmes

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is a process used to explore observations and answer questions. Originally used by scientists looking to prove new theories, its use has spread into many other areas, including that of problem-solving and decision-making.

The scientific method is designed to eliminate the influences of bias, prejudice and personal beliefs when testing a hypothesis or theory. It has developed alongside science itself, with origins going back to the 13th century. The scientific method is generally described as a series of steps.

- observations/theory

- explanation/conclusion

The first step is to develop a theory about the particular area of interest. A theory, in the context of logic or problem-solving, is a conjecture or speculation about something that is not necessarily fact, often based on a series of observations.

Once a theory has been devised, it can be questioned and refined into more specific hypotheses that can be tested. The hypotheses are potential explanations for the theory.

The testing, and subsequent analysis, of these hypotheses will eventually lead to a conclus ion which can prove or disprove the original theory.

Applying the Scientific Method to Problem-Solving

How can the scientific method be used to solve a problem, such as the color printer is not working?

1. Use observations to develop a theory.

In order to solve the problem, it must first be clear what the problem is. Observations made about the problem should be used to develop a theory. In this particular problem the theory might be that the color printer has run out of ink. This theory is developed as the result of observing the increasingly faded output from the printer.

2. Form a hypothesis.

Note down all the possible reasons for the problem. In this situation they might include:

- The printer is set up as the default printer for all 40 people in the department and so is used more frequently than necessary.

- There has been increased usage of the printer due to non-work related printing.

- In an attempt to reduce costs, poor quality ink cartridges with limited amounts of ink in them have been purchased.

- The printer is faulty.

All these possible reasons are hypotheses.

3. Test the hypothesis.

Once as many hypotheses (or reasons) as possible have been thought of, then each one can be tested to discern if it is the cause of the problem. An appropriate test needs to be devised for each hypothesis. For example, it is fairly quick to ask everyone to check the default settings of the printer on each PC, or to check if the cartridge supplier has changed.

4. Analyze the test results.

Once all the hypotheses have been tested, the results can be analyzed. The type and depth of analysis will be dependant on each individual problem, and the tests appropriate to it. In many cases the analysis will be a very quick thought process. In others, where considerable information has been collated, a more structured approach, such as the use of graphs, tables or spreadsheets, may be required.

5. Draw a conclusion.

Based on the results of the tests, a conclusion can then be drawn about exactly what is causing the problem. The appropriate remedial action can then be taken, such as asking everyone to amend their default print settings, or changing the cartridge supplier.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

The scientific method involves the use of two basic types of reasoning, inductive and deductive.

Inductive reasoning makes a conclusion based on a set of empirical results. Empirical results are the product of the collection of evidence from observations. For example:

‘Every time it rains the pavement gets wet, therefore rain must be water’.

There has been no scientific determination in the hypothesis that rain is water, it is purely based on observation. The formation of a hypothesis in this manner is sometimes referred to as an educated guess. An educated guess, whilst not based on hard facts, must still be plausible, and consistent with what we already know, in order to present a reasonable argument.

Deductive reasoning can be thought of most simply in terms of ‘If A and B, then C’. For example:

- if the window is above the desk, and

- the desk is above the floor, then

- the window must be above the floor

It works by building on a series of conclusions, which results in one final answer.

Social Sciences and the Scientific Method

The scientific method can be used to address any situation or problem where a theory can be developed. Although more often associated with natural sciences, it can also be used to develop theories in social sciences (such as psychology, sociology and linguistics), using both quantitative and qualitative methods.

Quantitative information is information that can be measured, and tends to focus on numbers and frequencies. Typically quantitative information might be gathered by experiments, questionnaires or psychometric tests. Qualitative information, on the other hand, is based on information describing meaning, such as human behavior, and the reasons behind it. Qualitative information is gathered by way of interviews and case studies, which are possibly not as statistically accurate as quantitative methods, but provide a more in-depth and rich description.

The resultant information can then be used to prove, or disprove, a hypothesis. Using a mix of quantitative and qualitative information is more likely to produce a rounded result based on the factual, quantitative information enriched and backed up by actual experience and qualitative information.

In terms of problem-solving or decision-making, for example, the qualitative information is that gained by looking at the ‘how’ and ‘why’ , whereas quantitative information would come from the ‘where’, ‘what’ and ‘when’.

It may seem easy to come up with a brilliant idea, or to suspect what the cause of a problem may be. However things can get more complicated when the idea needs to be evaluated, or when there may be more than one potential cause of a problem. In these situations, the use of the scientific method, and its associated reasoning, can help the user come to a decision, or reach a solution, secure in the knowledge that all options have been considered.

Join Mind Tools and get access to exclusive content.

This resource is only available to Mind Tools members.

Already a member? Please Login here

Try Mind Tools for FREE

Get unlimited access to all our career-boosting content and member benefits with our 7-day free trial.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

What Is Gibbs' Reflective Cycle?

Team Briefings

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Onboarding with steps.

Helping New Employees to Thrive

NEW! Pain Points Podcast - Perfectionism

Why Am I Such a Perfectionist?

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

The long game.

Dorie Clark

Expert Interviews

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the 6 scientific method steps and how to use them.

General Education

When you’re faced with a scientific problem, solving it can seem like an impossible prospect. There are so many possible explanations for everything we see and experience—how can you possibly make sense of them all? Science has a simple answer: the scientific method.

The scientific method is a method of asking and answering questions about the world. These guiding principles give scientists a model to work through when trying to understand the world, but where did that model come from, and how does it work?

In this article, we’ll define the scientific method, discuss its long history, and cover each of the scientific method steps in detail.

What Is the Scientific Method?

At its most basic, the scientific method is a procedure for conducting scientific experiments. It’s a set model that scientists in a variety of fields can follow, going from initial observation to conclusion in a loose but concrete format.

The number of steps varies, but the process begins with an observation, progresses through an experiment, and concludes with analysis and sharing data. One of the most important pieces to the scientific method is skepticism —the goal is to find truth, not to confirm a particular thought. That requires reevaluation and repeated experimentation, as well as examining your thinking through rigorous study.

There are in fact multiple scientific methods, as the basic structure can be easily modified. The one we typically learn about in school is the basic method, based in logic and problem solving, typically used in “hard” science fields like biology, chemistry, and physics. It may vary in other fields, such as psychology, but the basic premise of making observations, testing, and continuing to improve a theory from the results remain the same.

The History of the Scientific Method

The scientific method as we know it today is based on thousands of years of scientific study. Its development goes all the way back to ancient Mesopotamia, Greece, and India.

The Ancient World

In ancient Greece, Aristotle devised an inductive-deductive process , which weighs broad generalizations from data against conclusions reached by narrowing down possibilities from a general statement. However, he favored deductive reasoning, as it identifies causes, which he saw as more important.

Aristotle wrote a great deal about logic and many of his ideas about reasoning echo those found in the modern scientific method, such as ignoring circular evidence and limiting the number of middle terms between the beginning of an experiment and the end. Though his model isn’t the one that we use today, the reliance on logic and thorough testing are still key parts of science today.

The Middle Ages

The next big step toward the development of the modern scientific method came in the Middle Ages, particularly in the Islamic world. Ibn al-Haytham, a physicist from what we now know as Iraq, developed a method of testing, observing, and deducing for his research on vision. al-Haytham was critical of Aristotle’s lack of inductive reasoning, which played an important role in his own research.

Other scientists, including Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, Ibn Sina, and Robert Grosseteste also developed models of scientific reasoning to test their own theories. Though they frequently disagreed with one another and Aristotle, those disagreements and refinements of their methods led to the scientific method we have today.

Following those major developments, particularly Grosseteste’s work, Roger Bacon developed his own cycle of observation (seeing that something occurs), hypothesis (making a guess about why that thing occurs), experimentation (testing that the thing occurs), and verification (an outside person ensuring that the result of the experiment is consistent).

After joining the Franciscan Order, Bacon was granted a special commission to write about science; typically, Friars were not allowed to write books or pamphlets. With this commission, Bacon outlined important tenets of the scientific method, including causes of error, methods of knowledge, and the differences between speculative and experimental science. He also used his own principles to investigate the causes of a rainbow, demonstrating the method’s effectiveness.

Scientific Revolution

Throughout the Renaissance, more great thinkers became involved in devising a thorough, rigorous method of scientific study. Francis Bacon brought inductive reasoning further into the method, whereas Descartes argued that the laws of the universe meant that deductive reasoning was sufficient. Galileo’s research was also inductive reasoning-heavy, as he believed that researchers could not account for every possible variable; therefore, repetition was necessary to eliminate faulty hypotheses and experiments.

All of this led to the birth of the Scientific Revolution , which took place during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In 1660, a group of philosophers and physicians joined together to work on scientific advancement. After approval from England’s crown , the group became known as the Royal Society, which helped create a thriving scientific community and an early academic journal to help introduce rigorous study and peer review.

Previous generations of scientists had touched on the importance of induction and deduction, but Sir Isaac Newton proposed that both were equally important. This contribution helped establish the importance of multiple kinds of reasoning, leading to more rigorous study.

As science began to splinter into separate areas of study, it became necessary to define different methods for different fields. Karl Popper was a leader in this area—he established that science could be subject to error, sometimes intentionally. This was particularly tricky for “soft” sciences like psychology and social sciences, which require different methods. Popper’s theories furthered the divide between sciences like psychology and “hard” sciences like chemistry or physics.

Paul Feyerabend argued that Popper’s methods were too restrictive for certain fields, and followed a less restrictive method hinged on “anything goes,” as great scientists had made discoveries without the Scientific Method. Feyerabend suggested that throughout history scientists had adapted their methods as necessary, and that sometimes it would be necessary to break the rules. This approach suited social and behavioral scientists particularly well, leading to a more diverse range of models for scientists in multiple fields to use.

The Scientific Method Steps

Though different fields may have variations on the model, the basic scientific method is as follows:

#1: Make Observations

Notice something, such as the air temperature during the winter, what happens when ice cream melts, or how your plants behave when you forget to water them.

#2: Ask a Question

Turn your observation into a question. Why is the temperature lower during the winter? Why does my ice cream melt? Why does my toast always fall butter-side down?

This step can also include doing some research. You may be able to find answers to these questions already, but you can still test them!

#3: Make a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an educated guess of the answer to your question. Why does your toast always fall butter-side down? Maybe it’s because the butter makes that side of the bread heavier.

A good hypothesis leads to a prediction that you can test, phrased as an if/then statement. In this case, we can pick something like, “If toast is buttered, then it will hit the ground butter-first.”

#4: Experiment

Your experiment is designed to test whether your predication about what will happen is true. A good experiment will test one variable at a time —for example, we’re trying to test whether butter weighs down one side of toast, making it more likely to hit the ground first.

The unbuttered toast is our control variable. If we determine the chance that a slice of unbuttered toast, marked with a dot, will hit the ground on a particular side, we can compare those results to our buttered toast to see if there’s a correlation between the presence of butter and which way the toast falls.

If we decided not to toast the bread, that would be introducing a new question—whether or not toasting the bread has any impact on how it falls. Since that’s not part of our test, we’ll stick with determining whether the presence of butter has any impact on which side hits the ground first.

#5: Analyze Data

After our experiment, we discover that both buttered toast and unbuttered toast have a 50/50 chance of hitting the ground on the buttered or marked side when dropped from a consistent height, straight down. It looks like our hypothesis was incorrect—it’s not the butter that makes the toast hit the ground in a particular way, so it must be something else.

Since we didn’t get the desired result, it’s back to the drawing board. Our hypothesis wasn’t correct, so we’ll need to start fresh. Now that you think about it, your toast seems to hit the ground butter-first when it slides off your plate, not when you drop it from a consistent height. That can be the basis for your new experiment.

#6: Communicate Your Results

Good science needs verification. Your experiment should be replicable by other people, so you can put together a report about how you ran your experiment to see if other peoples’ findings are consistent with yours.

This may be useful for class or a science fair. Professional scientists may publish their findings in scientific journals, where other scientists can read and attempt their own versions of the same experiments. Being part of a scientific community helps your experiments be stronger because other people can see if there are flaws in your approach—such as if you tested with different kinds of bread, or sometimes used peanut butter instead of butter—that can lead you closer to a good answer.

A Scientific Method Example: Falling Toast

We’ve run through a quick recap of the scientific method steps, but let’s look a little deeper by trying again to figure out why toast so often falls butter side down.

#1: Make Observations

At the end of our last experiment, where we learned that butter doesn’t actually make toast more likely to hit the ground on that side, we remembered that the times when our toast hits the ground butter side first are usually when it’s falling off a plate.

The easiest question we can ask is, “Why is that?”

We can actually search this online and find a pretty detailed answer as to why this is true. But we’re budding scientists—we want to see it in action and verify it for ourselves! After all, good science should be replicable, and we have all the tools we need to test out what’s really going on.

Why do we think that buttered toast hits the ground butter-first? We know it’s not because it’s heavier, so we can strike that out. Maybe it’s because of the shape of our plate?

That’s something we can test. We’ll phrase our hypothesis as, “If my toast slides off my plate, then it will fall butter-side down.”

Just seeing that toast falls off a plate butter-side down isn’t enough for us. We want to know why, so we’re going to take things a step further—we’ll set up a slow-motion camera to capture what happens as the toast slides off the plate.

We’ll run the test ten times, each time tilting the same plate until the toast slides off. We’ll make note of each time the butter side lands first and see what’s happening on the video so we can see what’s going on.

When we review the footage, we’ll likely notice that the bread starts to flip when it slides off the edge, changing how it falls in a way that didn’t happen when we dropped it ourselves.

That answers our question, but it’s not the complete picture —how do other plates affect how often toast hits the ground butter-first? What if the toast is already butter-side down when it falls? These are things we can test in further experiments with new hypotheses!

Now that we have results, we can share them with others who can verify our results. As mentioned above, being part of the scientific community can lead to better results. If your results were wildly different from the established thinking about buttered toast, that might be cause for reevaluation. If they’re the same, they might lead others to make new discoveries about buttered toast. At the very least, you have a cool experiment you can share with your friends!

Key Scientific Method Tips

Though science can be complex, the benefit of the scientific method is that it gives you an easy-to-follow means of thinking about why and how things happen. To use it effectively, keep these things in mind!

Don’t Worry About Proving Your Hypothesis

One of the important things to remember about the scientific method is that it’s not necessarily meant to prove your hypothesis right. It’s great if you do manage to guess the reason for something right the first time, but the ultimate goal of an experiment is to find the true reason for your observation to occur, not to prove your hypothesis right.

Good science sometimes means that you’re wrong. That’s not a bad thing—a well-designed experiment with an unanticipated result can be just as revealing, if not more, than an experiment that confirms your hypothesis.

Be Prepared to Try Again

If the data from your experiment doesn’t match your hypothesis, that’s not a bad thing. You’ve eliminated one possible explanation, which brings you one step closer to discovering the truth.

The scientific method isn’t something you’re meant to do exactly once to prove a point. It’s meant to be repeated and adapted to bring you closer to a solution. Even if you can demonstrate truth in your hypothesis, a good scientist will run an experiment again to be sure that the results are replicable. You can even tweak a successful hypothesis to test another factor, such as if we redid our buttered toast experiment to find out whether different kinds of plates affect whether or not the toast falls butter-first. The more we test our hypothesis, the stronger it becomes!

What’s Next?

Want to learn more about the scientific method? These important high school science classes will no doubt cover it in a variety of different contexts.

Test your ability to follow the scientific method using these at-home science experiments for kids !

Need some proof that science is fun? Try making slime

Melissa Brinks graduated from the University of Washington in 2014 with a Bachelor's in English with a creative writing emphasis. She has spent several years tutoring K-12 students in many subjects, including in SAT prep, to help them prepare for their college education.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Chapter 6: Scientific Problem Solving

If you prefer a video, click this button:

Scientific Problem Solving Video

Science is a method to discover empirical truths and patterns. Roughly speaking, the scientific method consists of

1) Observing

2) Forming a hypothesis

3) Testing the hypothesis and

4) Interpreting the data to confirm or disconfirm the hypothesis.

The beauty of science is that any scientific claim can be tested if you have the proper knowledge and equipment.

You can also use the scientific method to solve everyday problems: 1) Observe and clearly define the problem, 2) Form a hypothesis, 3) Test it, and 4) Confirm the hypothesis... or disconfirm it and start over.

So, the next time you are cursing in traffic or emotionally reacting to a problem, take a few deep breaths and then use this rational and scientific approach. Slow down, observe, hypothesize, and test.

Explain how you would solve these problems using the four steps of the scientific process.

Example: The fire alarm is not working.

1) Observe/Define the problem: it does not beep when I push the button.

2) Hypothesis: it is caused by a dead battery.

3) Test: try a new battery.

4) Confirm/Disconfirm: the alarm now works. If it does not work, start over by testing another hypothesis like “it has a loose wire.”

- My car will not start.

- My child is having problems reading.

- I owe $20,000, but only make $10 an hour.

- My boss is mean. I want him/her to stop using rude language towards me.

- My significant other is lazy. I want him/her to help out more.

6-8. Identify three problems where you can apply the scientific method.

*Answers will vary.

Application and Value

Science is more of a process than a body of knowledge. In our daily lives, we often emotionally react and jump to quick solutions when faced with problems, but following the four steps of the scientific process can help us slow down and discover more intelligent solutions.

In your study of philosophy, you will explore deeper questions about science. For example, are there any forms of knowledge that are nonscientific? Can science tell us what we ought to do? Can logical and mathematical truths be proven in a scientific way? Does introspection give knowledge even though I cannot scientifically observe your introspective thoughts? Is science truly objective? These are challenging questions that should help you discover the scope of science without diminishing its awesome power.

But the first step in answering these questions is knowing what science is, and this chapter clarifies its essence. Again, Science is not so much a body of knowledge as it is a method of observing, hypothesizing, and testing. This method is what all the sciences have in common.

Perhaps too science should involve falsifiability, which is a concept explored in the next chapter.

Return to Logic Home Next (Chapter 7, Falsifiability)

Click on my affiliate link above (Logic Book Image) to explore the most popular introduction to logic. If you purchase it, I recommend buying a less expensive older edition.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Mechanics (Essentials) - Class 11th

Course: mechanics (essentials) - class 11th > unit 2.

- Introduction to physics

- What is physics?

The scientific method

- Models and Approximations in Physics

Introduction

- Make an observation.

- Ask a question.

- Form a hypothesis , or testable explanation.

- Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

- Test the prediction.

- Iterate: use the results to make new hypotheses or predictions.

Scientific method example: Failure to toast

1. make an observation..

- Observation: the toaster won't toast.

2. Ask a question.

- Question: Why won't my toaster toast?

3. Propose a hypothesis.

- Hypothesis: Maybe the outlet is broken.

4. Make predictions.

- Prediction: If I plug the toaster into a different outlet, then it will toast the bread.

5. Test the predictions.

- Test of prediction: Plug the toaster into a different outlet and try again.

- If the toaster does toast, then the hypothesis is supported—likely correct.

- If the toaster doesn't toast, then the hypothesis is not supported—likely wrong.

Logical possibility

Practical possibility, building a body of evidence, 6. iterate..

- Iteration time!

- If the hypothesis was supported, we might do additional tests to confirm it, or revise it to be more specific. For instance, we might investigate why the outlet is broken.

- If the hypothesis was not supported, we would come up with a new hypothesis. For instance, the next hypothesis might be that there's a broken wire in the toaster.

Want to join the conversation?

- News/Events

- Arts and Sciences

- Design and the Arts

- Engineering

- Global Futures

- Health Solutions

- Nursing and Health Innovation

- Public Service and Community Solutions

- University College

- Thunderbird School of Global Management

- Polytechnic

- Downtown Phoenix

- Online and Extended

- Lake Havasu

- Research Park

- Washington D.C.

- Biology Bits

- Bird Finder

- Coloring Pages

- Experiments and Activities

- Games and Simulations

- Quizzes in Other Languages

- Virtual Reality (VR)

- World of Biology

- Meet Our Biologists

- Listen and Watch

- PLOSable Biology

- All About Autism

- Xs and Ys: How Our Sex Is Decided

- When Blood Types Shouldn’t Mix: Rh and Pregnancy

- What Is the Menstrual Cycle?

- Understanding Intersex

- The Mysterious Case of the Missing Periods

- Summarizing Sex Traits

- Shedding Light on Endometriosis

- Periods: What Should You Expect?

- Menstruation Matters

- Investigating In Vitro Fertilization

- Introducing the IUD

- How Fast Do Embryos Grow?

- Helpful Sex Hormones

- Getting to Know the Germ Layers

- Gender versus Biological Sex: What’s the Difference?

- Gender Identities and Expression

- Focusing on Female Infertility

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Pregnancy

- Ectopic Pregnancy: An Unexpected Path

- Creating Chimeras

- Confronting Human Chimerism

- Cells, Frozen in Time

- EvMed Edits

- Stories in Other Languages

- Virtual Reality

- Zoom Gallery

- Ugly Bug Galleries

- Ask a Question

- Top Questions

- Question Guidelines

- Permissions

- Information Collected

- Author and Artist Notes

- Share Ask A Biologist

- Articles & News

- Our Volunteers

- Teacher Toolbox

show/hide words to know

Biased: when someone presents only one viewpoint. Biased articles do not give all the facts and often mislead the reader.

Conclusion: what a person decides based on information they get through research including experiments.

Method: following a certain set of steps to make something, or find an answer to a question. Like baking a pie or fixing the tire on a bicycle.

Research: looking for answers to questions using tools like the scientific method.

What is the Scientific Method?

If you have ever seen something going on and wondered why or how it happened, you have started down the road to discovery. If you continue your journey, you are likely to guess at some of your own answers for your question. Even further along the road you might think of ways to find out if your answers are correct. At this point, whether you know it or not, you are following a path that scientists call the scientific method. If you do some experiments to see if your answer is correct and write down what you learn in a report, you have pretty much completed everything a scientist might do in a laboratory or out in the field when doing research. In fact, the scientific method works well for many things that don’t usually seem so scientific.

The Flashlight Mystery...

Like a crime detective, you can use the elements of the scientific method to find the answer to everyday problems. For example you pick up a flashlight and turn it on, but the light does not work. You have observed that the light does not work. You ask the question, Why doesn't it work? With what you already know about flashlights, you might guess (hypothesize) that the batteries are dead. You say to yourself, if I buy new batteries and replace the old ones in the flashlight, the light should work. To test this prediction you replace the old batteries with new ones from the store. You click the switch on. Does the flashlight work? No?

What else could be the answer? You go back and hypothesize that it might be a broken light bulb. Your new prediction is if you replace the broken light bulb the flashlight will work. It’s time to go back to the store and buy a new light bulb. Now you test this new hypothesis and prediction by replacing the bulb in the flashlight. You flip the switch again. The flashlight lights up. Success!

If this were a scientific project, you would also have written down the results of your tests and a conclusion of your experiments. The results of only the light bulb hypothesis stood up to the test, and we had to reject the battery hypothesis. You would also communicate what you learned to others with a published report, article, or scientific paper.

More to the Mystery...

Not all questions can be answered with only two experiments. It can often take a lot more work and tests to find an answer. Even when you find an answer it may not always be the only answer to the question. This is one reason that different scientists will work on the same question and do their own experiments.

In our flashlight example, you might never get the light to turn on. This probably means you haven’t made enough different guesses (hypotheses) to test the problem. Were the new batteries in the right way? Was the switch rusty, or maybe a wire is broken. Think of all the possible guesses you could test.

No matter what the question, you can use the scientific method to guide you towards an answer. Even those questions that do not seem to be scientific can be solved using this process. Like with the flashlight, you might need to repeat several of the elements of the scientific method to find an answer. No matter how complex the diagram, the scientific method will include the following pieces in order to be complete.

The elements of the scientific method can be used by anyone to help answer questions. Even though these elements can be used in an ordered manner, they do not have to follow the same order. It is better to think of the scientific method as fluid process that can take different paths depending on the situation. Just be sure to incorporate all of the elements when seeking unbiased answers. You may also need to go back a few steps (or a few times) to test several different hypotheses before you come to a conclusion. Click on the image to see other versions of the scientific method.

- Observation – seeing, hearing, touching…

- Asking a question – why or how?

- Hypothesis – a fancy name for an educated guess about what causes something to happen.

- Prediction – what you think will happen if…

- Testing – this is where you get to experiment and be creative.

- Conclusion – decide how your test results relate to your predictions.

- Communicate – share your results so others can learn from your work.

Other Parts of the Scientific Method…

Now that you have an idea of how the scientific method works there are a few other things to learn so that you will be able test out your new skills and test your hypotheses.

- Control - A group that is similar to other groups but is left alone so that it can be compared to see what happened to the other groups that are tested.

- Data - the numbers and measurements you get from the test in a scientific experiment.

- Independent variable - a variable that you change as part of your experiment. It is important to only change one independent variable for each experiment.

- Dependent variable - a variable that changes when the independent variable is changed.

- Controlled Variable - these are variables that you never change in your experiment.

Practicing Observations and Wondering How and Why...

It is really hard not to notice things around us and wonder about them. This is how the scientific method begins, by observing and wondering why and how. Why do leaves on trees in many parts of the world turn from green to red, orange, or yellow and fall to the ground when winter comes? How does a spider move around their web without getting stuck like its victims? Both of these questions start with observing something and asking questions. The next time you see something and ask yourself, “I wonder why that does that, or how can it do that?” try out your new detective skills, and see what answer you can find.

Try Out Your Detective Skills

Now that you have the basics of the scientific method, why not test your skills? The Science Detectives Training Room will test your problem solving ability. Step inside and see if you can escape the room. While you are there, look around and see what other interesting things might be waiting. We think you find this game a great way to learn the scientific method. In fact, we bet you will discover that you already use the scientific method and didn't even know it.

After you've learned the basics of being a detective, practice those skills in The Case of the Mystery Images . While you are there, pay attention to what's around you as you figure out just what is happening in the mystery photos that surround you.

Ready for your next challenge? Try Science Detectives: Case of the Mystery Images for even more mysteries to solve. Take your scientific abilities one step further by making observations and formulating hypothesis about the mysterious images you find within.

Acknowledgements:

We thank John Alcock for his feedback and suggestions on this article.

Science Detectives - Mystery Room Escape was produced in partnership with the Arizona Science Education Collaborative (ASEC) and funded by ASU Women & Philanthropy.

Flashlight image via Wikimedia Commons - The Oxygen Team

Read more about: Using the Scientific Method to Solve Mysteries

View citation, bibliographic details:.

- Article: Using the Scientific Method to Solve Mysteries

- Author(s): CJ Kazilek and David Pearson

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: October 8, 2009

- Date accessed: April 17, 2024

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/scientific-method

CJ Kazilek and David Pearson. (2009, October 08). Using the Scientific Method to Solve Mysteries . ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved April 17, 2024 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/scientific-method

Chicago Manual of Style

CJ Kazilek and David Pearson. "Using the Scientific Method to Solve Mysteries ". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 08 October, 2009. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/scientific-method

MLA 2017 Style

CJ Kazilek and David Pearson. "Using the Scientific Method to Solve Mysteries ". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 08 Oct 2009. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 17 Apr 2024. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/scientific-method

Do you think you can escape our Science Detectives Training Room ?

Using the Scientific Method to Solve Mysteries

Be part of ask a biologist.

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.

Share to Google Classroom

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: The Scientific Method - How Chemists Think

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 47444

Learning Objectives

- Identify the components of the scientific method.

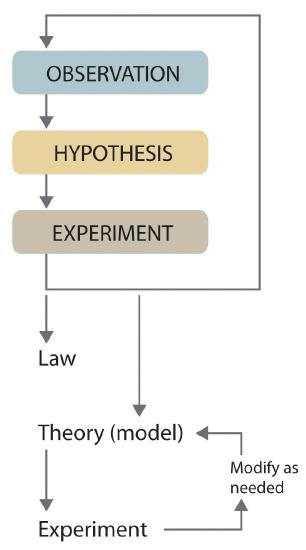

Scientists search for answers to questions and solutions to problems by using a procedure called the scientific method. This procedure consists of making observations, formulating hypotheses, and designing experiments; which leads to additional observations, hypotheses, and experiments in repeated cycles (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Step 1: Make observations

Observations can be qualitative or quantitative. Qualitative observations describe properties or occurrences in ways that do not rely on numbers. Examples of qualitative observations include the following: "the outside air temperature is cooler during the winter season," "table salt is a crystalline solid," "sulfur crystals are yellow," and "dissolving a penny in dilute nitric acid forms a blue solution and a brown gas." Quantitative observations are measurements, which by definition consist of both a number and a unit. Examples of quantitative observations include the following: "the melting point of crystalline sulfur is 115.21° Celsius," and "35.9 grams of table salt—the chemical name of which is sodium chloride—dissolve in 100 grams of water at 20° Celsius." For the question of the dinosaurs’ extinction, the initial observation was quantitative: iridium concentrations in sediments dating to 66 million years ago were 20–160 times higher than normal.

Step 2: Formulate a hypothesis

After deciding to learn more about an observation or a set of observations, scientists generally begin an investigation by forming a hypothesis, a tentative explanation for the observation(s). The hypothesis may not be correct, but it puts the scientist’s understanding of the system being studied into a form that can be tested. For example, the observation that we experience alternating periods of light and darkness corresponding to observed movements of the sun, moon, clouds, and shadows is consistent with either one of two hypotheses:

- Earth rotates on its axis every 24 hours, alternately exposing one side to the sun.

- The sun revolves around Earth every 24 hours.

Suitable experiments can be designed to choose between these two alternatives. For the disappearance of the dinosaurs, the hypothesis was that the impact of a large extraterrestrial object caused their extinction. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), this hypothesis does not lend itself to direct testing by any obvious experiment, but scientists can collect additional data that either support or refute it.

Step 3: Design and perform experiments

After a hypothesis has been formed, scientists conduct experiments to test its validity. Experiments are systematic observations or measurements, preferably made under controlled conditions—that is—under conditions in which a single variable changes.

Step 4: Accept or modify the hypothesis

A properly designed and executed experiment enables a scientist to determine whether or not the original hypothesis is valid. If the hypothesis is valid, the scientist can proceed to step 5. In other cases, experiments often demonstrate that the hypothesis is incorrect or that it must be modified and requires further experimentation.

Step 5: Development into a law and/or theory

More experimental data are then collected and analyzed, at which point a scientist may begin to think that the results are sufficiently reproducible (i.e., dependable) to merit being summarized in a law, a verbal or mathematical description of a phenomenon that allows for general predictions. A law simply states what happens; it does not address the question of why.

One example of a law, the law of definite proportions , which was discovered by the French scientist Joseph Proust (1754–1826), states that a chemical substance always contains the same proportions of elements by mass. Thus, sodium chloride (table salt) always contains the same proportion by mass of sodium to chlorine, in this case 39.34% sodium and 60.66% chlorine by mass, and sucrose (table sugar) is always 42.11% carbon, 6.48% hydrogen, and 51.41% oxygen by mass.

Whereas a law states only what happens, a theory attempts to explain why nature behaves as it does. Laws are unlikely to change greatly over time unless a major experimental error is discovered. In contrast, a theory, by definition, is incomplete and imperfect, evolving with time to explain new facts as they are discovered.

Because scientists can enter the cycle shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) at any point, the actual application of the scientific method to different topics can take many different forms. For example, a scientist may start with a hypothesis formed by reading about work done by others in the field, rather than by making direct observations.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Classify each statement as a law, a theory, an experiment, a hypothesis, an observation.

- Ice always floats on liquid water.

- Birds evolved from dinosaurs.

- Hot air is less dense than cold air, probably because the components of hot air are moving more rapidly.

- When 10 g of ice were added to 100 mL of water at 25°C, the temperature of the water decreased to 15.5°C after the ice melted.

- The ingredients of Ivory soap were analyzed to see whether it really is 99.44% pure, as advertised.

- This is a general statement of a relationship between the properties of liquid and solid water, so it is a law.

- This is a possible explanation for the origin of birds, so it is a hypothesis.

- This is a statement that tries to explain the relationship between the temperature and the density of air based on fundamental principles, so it is a theory.

- The temperature is measured before and after a change is made in a system, so these are observations.

- This is an analysis designed to test a hypothesis (in this case, the manufacturer’s claim of purity), so it is an experiment.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Classify each statement as a law, a theory, an experiment, a hypothesis, a qualitative observation, or a quantitative observation.

- Measured amounts of acid were added to a Rolaids tablet to see whether it really “consumes 47 times its weight in excess stomach acid.”

- Heat always flows from hot objects to cooler ones, not in the opposite direction.

- The universe was formed by a massive explosion that propelled matter into a vacuum.

- Michael Jordan is the greatest pure shooter to ever play professional basketball.

- Limestone is relatively insoluble in water, but dissolves readily in dilute acid with the evolution of a gas.

The scientific method is a method of investigation involving experimentation and observation to acquire new knowledge, solve problems, and answer questions. The key steps in the scientific method include the following:

- Step 1: Make observations.

- Step 2: Formulate a hypothesis.

- Step 3: Test the hypothesis through experimentation.

- Step 4: Accept or modify the hypothesis.

- Step 5: Develop into a law and/or a theory.

Contributions & Attributions

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The scientific method. At the core of biology and other sciences lies a problem-solving approach called the scientific method. The scientific method has five basic steps, plus one feedback step: Make an observation. Ask a question. Form a hypothesis, or testable explanation. Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

• answer key for the contents of each box Procedure • Introduce the scientific method by brainstorming how a problem is solved. Formulate student's ideas into a chart of steps in the scientific method. Determine with the students how a scientist solves problems. • Arrange students in working groups of 3 or 4.

Find worksheets and answer keys to test your understanding of the scientific method and its steps. Learn how to form hypotheses, identify variables, collect data, and draw conclusions in various scenarios.

The scientific method is a process used to explore observations and answer questions. Originally used by scientists looking to prove new theories, its use has spread into many other areas, including that of problem-solving and decision-making. The scientific method is designed to eliminate the influences of bias, prejudice and personal beliefs ...

Ask a question - identify the problem to be considered. Make observations - gather data that pertains to the question. Propose an explanation (a hypothesis) for the observations. Make new observations to test the hypothesis further. Figure 1.12.2 1.12. 2: Sir Francis Bacon.

Learn the definition, history, and steps of the scientific method, a procedure for conducting scientific experiments. The web page does not provide an answer key for scientific problem solving.

A process that uses a variety of skills and tools to answer questions or to test ideas. Steps used: Ask questions, hypothesize and predict, test hypothesis, analyze results, draw conclusions, and communicate results. Rules: Often scientific investigations are launched to answer who, what, when, where, or how questions.

In doing so, they are using the scientific method. 1.2: Scientific Approach for Solving Problems is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts. Chemists expand their knowledge by making observations, carrying out experiments, and testing hypotheses to develop laws to summarize their results and ...

The six steps of the scientific method include: 1) asking a question about something you observe, 2) doing background research to learn what is already known about the topic, 3) constructing a hypothesis, 4) experimenting to test the hypothesis, 5) analyzing the data from the experiment and drawing conclusions, and 6) communicating the results ...

You have used the scientific method to find an answer to a question. Scientific Problem Solving. ... it eventually becomes a theory - a general principle that is offered to explain natural phenomena. Note a key word - explanation. The theory offers a description of why something happens. A law, on the other hand, is a statement that is ...

At 14 years old, Adam is 3 years younger than his brother Michael. A class of 30 students separated into equal sized teams results in 5 students per team. When the bananas were divided evenly among the 6 monkeys, each monkey received 4 bananas. Define a variable.

Learn how to use the scientific method to solve everyday problems and explore deeper questions about science. This web page does not provide an answer key for the exercises or examples.

Scientific Problem Solving — Nature of Science Lessons 1-3. Term. 1 / 22. critical thinking. Click the card to flip 👆. Definition. 1 / 22. comparing what you already know with the information you are given in order to decide whether you agree with it.

The scientific method. At the core of physics and other sciences lies a problem-solving approach called the scientific method. The scientific method has five basic steps, plus one feedback step: Make an observation. Ask a question. Form a hypothesis, or testable explanation. Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

The scientific method is a method of investigation involving experimentation and observation to acquire new knowledge, solve problems, and answer questions. The key steps in the scientific method include the following: Step 1: Make observations. Step 2: Formulate a hypothesis. Step 3: Test the hypothesis through experimentation.

How to Introduce Students to the Scientific MethodStudents, and sometimes even teachers, often think scientists only use the scientific method to answer science-related questions. In fact, you can apply the scientific method to almost any problem. The key is to use the elements (steps) to reduce bias and help come to a solution to the problem.One Size Does Not Fit All[caption

Use the scientific method and your problem solving abilities to get out. While you are in the escape room ... Like a crime detective, you can use the elements of the scientific method to find the answer to everyday problems. For example you pick up a flashlight and turn it on, but the light does not work. You have observed that the light does ...

Test your knowledge of scientific inquiry, the scientific method, and scientific laws and theories with these flashcards. Find definitions, examples, and steps for each term and concept.

Solving Scientific Problems by Asking Diverse Questions. Gravity has been apparent for thousands of years: Aristotle, for example, proposed that objects fall to settle into their natural place in 4th century BC. But it was not until around 1900, when Issac Newton explained gravity using mathematical equations, that we really understood the ...

The Nature of Science-chapter 1 section 2 Scientific Problem Solving. Term. 1 / 12. Scientific methods. Click the card to flip 👆. Definition. 1 / 12. are steps used to solve problems or answer question in a scientific way. Click the card to flip 👆.

Exercise 1. Exercise 2. Exercise 3. At Quizlet, we're giving you the tools you need to take on any subject without having to carry around solutions manuals or printing out PDFs! Now, with expert-verified solutions from Campbell Biology 11th Edition, you'll learn how to solve your toughest homework problems.

The scientific method is a method of investigation involving experimentation and observation to acquire new knowledge, solve problems, and answer questions. The key steps in the scientific method include the following: Step 1: Make observations. Step 2: Formulate a hypothesis. Step 3: Test the hypothesis through experimentation.

Find step-by-step solutions and answers to Campbell Biology - 9780135188743, as well as thousands of textbooks so you can move forward with confidence. ... Scientific Skills Exercise. Page 136: Concept Check 7.3. Page 139: Concept Check 7.4. Page 141: Concept Check 7.5. ... Problem-Solving Exercise. Page 1011: Concept Check 45.2. Page 1014 ...