An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Survey research: we can do better

Susan starr , mls, phd.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Readers may use articles without permission of copyright owners, as long as the author and MLA are acknowledged and the use is educational and not for profit.

Survey research is a commonly employed methodology in library and information science and the most frequently used research technique in papers published in the Journal of the Medical Library Association (JMLA) [ 1 ]. Unfortunately, very few of the survey reports that the JMLA receives provide sufficiently sound evidence to qualify as full-length JMLA research papers. A great deal of effort often goes into such studies, and our profession really needs the kind of evidence that the authors of these studies hoped to provide. Fortunately, the problems in these studies are not all that difficult to resolve. However, the problems do have to be addressed at the outset , before the survey is sent to potential respondents. Once the survey has been administered, it is too late.

To determine if a report qualifies for publication as a research study, the JMLA uses the definition of research given by the US Department of Health and Human Services, “a systematic investigation…designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge” [ 2 ]. Problems arise when submitted surveys do not meet these criteria; either the reader cannot generalize from the findings to the population at large and/or the survey does not add to the knowledgebase of health sciences librarianship. If the results seem interesting, the JMLA may publish the paper as a brief communication in the hope that others will follow up with more in-depth investigations. However, many of these problematic surveys could have provided critically needed information, if only they had been done slightly differently. There are three common problems with the surveys that the JMLA receives, and each has a relatively straightforward solution.

Three common problems

Problem #1: The survey has not been designed to answer a question of interest to a substantial group of potential readers of the JMLA. A survey intended for publication should be designed to shed light on research questions relevant to health sciences librarianship or the delivery of biomedical information. Questions regarding user behavior, the effectiveness of interventions, barriers to using information, the utility of metadata, and so on are all potentially answerable with survey methodology. For example, a survey could be designed to reveal what influences users' decisions to use a library, whether physicians retain information retrieval techniques that are taught in medical school, what prevents clinicians from consulting published research, whether users appreciate good metadata, and so on. These are all important questions on issues of general interest, and surveys to help answer them are suitable for publication.

Problems arise because surveys can be used to provide information on local issues as well. For example, a librarian may wish to determine whether library users will tolerate increases in interlibrary loan fees, whether searchers are having trouble with a proxy server, or if local administrators approve of library services. A survey can be the best method to uncover this kind of information. However, such surveys are usually not publishable, even as a brief communication, as the questions included relate almost exclusively to local problems.

Solution #1: Before embarking on a survey intended for publication, review the current literature on the topic of interest. Design the survey to specifically address an issue of general importance that is not already answered in the literature. Survey questions should be written to provide information that can be used by others. A few questions specific to your institution or user group can also be included if necessary.

Problem #2: The results cannot be generalized beyond the group of people who answered the survey. Unfortunately, a major problem in all survey research is that respondents are almost always self-selected. Not everyone who receives a survey is likely to answer it, no matter how many times they are reminded or what incentives are offered. If those who choose to respond are different in some important way from those who do not, the results may not reflect the opinions or behaviors of the entire population under study. For example, to identify barriers to nurses' use of information, a survey should be answered by a representative sample of the nursing population. If only recent graduates of a nursing program, only pediatric nurses, or only nurses who are very annoyed with lack of access to computers in their hospital answer, the results may well be biased and so cannot be generalized to all nurses. Such a survey could be published as a brief communication, if the results were provocative and might stimulate research by others, but it would not be publishable as a research paper.

Solution #2: To address sample bias, take these three steps:

Send the survey to a representative sample of the population. Use reminders and incentives to obtain a high response rate (over 60%), thus minimizing the chances that only those with a particular perspective are answering the survey. And…

Include questions designed to identify sample bias. Questions will vary according to the topic of the survey, but typically such questions identify the demographics (age, sex, educational level, position, etc.) of the respondents or the characteristics of the organization (size, budget, location, etc.). Then…

Compare the characteristics of those answering the survey to those of known distributions of the population to identify possible bias. Samples of librarians, for example, can be compared to Medical Library Association (MLA) member surveys to determine if they reflect the general characteristics of MLA members. Samples of clinicians can be compared to statistics on the nations' medical professionals, and samples of academic libraries can be compared to the characteristics reported in the Association of Academic Health Sciences Library (AAHSL) annual survey. If the sample appears to be biased, acknowledge that as a limitation of the study's results.

Problem #3: The answers to the survey questions do not provide the information needed to address the issue at hand. Many times survey questions in studies submitted to the JMLA are ambiguous. Since it is impossible to determine what the answers represent, the paper must be rejected. A related and more subtle problem occurs when the survey did not ask about all the relevant issues. For example, a librarian might decide to survey clinicians to identify barriers to their use of mobile devices. She designs a survey that includes questions related to physical barriers, such as screen size, and questions on availability issues, such as accessibility of a particular database. The paper reports that the major barriers to use of mobile devices are physical problems with the devices. However, reviewers may note that there are many other possible barriers to using mobile technology in a clinical setting. Infrastructure issues, such as wireless connectivity in the hospital, and organizational issues, such as policies with respect to using cell phones in front of patients, can be critical factors. As a result, the conclusion of the survey is misleading, and the paper cannot be published.

Solution #3: Interview a few representative members of the intended survey population to identify all the critical aspects of the study topic before designing the survey. Then, pretest the survey on others and discuss the survey with pretest participants to identify ambiguous answers or unintelligible questions.

Benchmarking surveys

Benchmarking surveys provide data on the characteristics of a particular population of individuals, businesses, or organizations. Their intention is not to add to the knowledgebase of a discipline, but instead to provide numerical information that others can use for that purpose. The US Census is an example of a benchmarking survey; the MLA membership survey is another benchmarking tool as are the AAHSL annual survey and many of the surveys undertaken by the Pew Research Center. The data in these surveys are used by others both for practical purposes and for research. Social scientists use census data to develop economic models; academic medical libraries use AAHSL data to justify their budgets; and policy makers use the Pew data to understand social trends in the United States.

To be useful, a benchmarking study must be structured so that the data can be used either by researchers to compare different groups or by organizations, such as hospitals or libraries, to identify a peer group for comparative purposes. Using data to reliably compare groups selected according to multiple variables requires a very large scale study, an unbiased sample, and a thoroughly pretested survey instrument. Because benchmarking surveys need to be large and use a professionally constructed sample and survey instrument, most such surveys are done by organizations rather than individuals. Few, if any, benchmarking surveys submitted to the JMLA have a large enough sample to permit detailed analysis or identification of peer groups. They remain suggestive rather than conclusive and are normally only published as brief communications.

Three problems and three solutions

The solutions are not all that difficult to implement but as noted at the beginning of this editorial, they must be put in place before the survey is administered. To “develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge,” a survey needs to be created to answer a question that is important to others, gather information that will allow the researcher to identify sample bias, and use a well-designed unambiguous set of questions. The research question comes first; if the answer is already in the literature, then no further research is required. Developing a sampling methodology comes next, including identifying possible sources of bias and creating questions that will allow them to be identified. Last are interviews to refine the questions and pretesting to identify problematic language. We can do better surveys, and if we do, we will have the evidence we need to improve the delivery of biomedical information.

- 1. Gore S.A, Nordberg J.M, Palmer L.A, Piorun M.E. Trends in health sciences library and information science research: an analysis of research publications in the Bulletin of the Medical Library Association and Journal of the Medical Library Association from 1991 to 2007. J Med Lib Assoc. 2009 Jul;97(3):203–11. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.97.3.009. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Protection of human subjects. 45 CFR 46.102(d) 2005.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (46.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Advertisement

Marketing survey research best practices: evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles

- Methodological Paper

- Published: 10 April 2017

- Volume 46 , pages 92–108, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- John Hulland 1 ,

- Hans Baumgartner 2 &

- Keith Marion Smith 3

21k Accesses

634 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Survey research methodology is widely used in marketing, and it is important for both the field and individual researchers to follow stringent guidelines to ensure that meaningful insights are attained. To assess the extent to which marketing researchers are utilizing best practices in designing, administering, and analyzing surveys, we review the prevalence of published empirical survey work during the 2006–2015 period in three top marketing journals— Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science ( JAMS ), Journal of Marketing ( JM ), and Journal of Marketing Research ( JMR )—and then conduct an in-depth analysis of 202 survey-based studies published in JAMS . We focus on key issues in two broad areas of survey research (issues related to the choice of the object of measurement and selection of raters, and issues related to the measurement of the constructs of interest), and we describe conceptual considerations related to each specific issue, review how marketing researchers have attended to these issues in their published work, and identify appropriate best practices.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A Retrospective on the Use of Survey Methodologies in Marketing Research

Crafting Survey Research: A Systematic Process for Conducting Survey Research

In conducting their topical review of publications in JMR , Huber et al. ( 2014 ) show evidence that the incidence of survey work has declined, particularly as new editors more skeptical of the survey method have emerged. They conclude (p. 88)—in looking at the results of their correspondence analysis—that survey research is more of a peripheral than a core topic in marketing. This perspective seems to be more prevalent in JMR than in JM and JAMS , as we note above.

A copy of the coding scheme used is available from the first author.

Several studies used more than one mode.

Traditionally, commercial researchers used phone as their primary collection mode. Today, 60% of commercial studies are conducted online (CASRO 2015 ), growing at a rate of roughly 8% per year.

Although the two categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive, the overlap was small ( n = 4).

This is close to the number of studies in which an explicit sampling frame was employed, which makes sense (i.e., one would not expect a check for non-response bias when a convenience sample is used).

It is interesting to note that Cote and Buckley examined the extent of CMV present in papers published across a variety of disciplines, and found that CMV was lowest for marketing (16%) and highest for the field of education (> 30%). This does not mean, however, that marketers do a consistently good job of accounting for CMV.

In practice, these items need to be conceptually related yet empirically distinct from one another. Using minor variations of the same basic item just to have multiple items does not result in the advantages described here.

In general, the use of PLS (which is usually employed when the measurement model is formative or mixed) was uncommon in our review, so it appears that most studies focused on using reflective measures.

Most of the studies discussing discriminant validity used the approach proposed by Fornell and Larcker ( 1981 ). A recent paper by Voorhees et al. ( 2016 ) suggests use of two approaches to determining discriminant validity: (1) the Fornell and Larcker test and (2) a new approach proposed by Henseler et al. ( 2015 ).

This solution is not a universal panacea. For example, Kammeyer-Mueller et al. ( 2010 ) show using simulated data that under some conditions using distinct data sources can distort estimation. Their point, however, is that the researcher must think carefully about this issue and resist using easy one-size-fits-all solutions.

Podsakoff et al. ( 2003 ) also mention two other techniques—the correlated uniqueness model and the direct product model—but do not recommend their use. Only very limited use of either technique has been made in marketing, so we do not discuss them further in this paper.

These techniques are described more extensively in Podsakoff et al. ( 2003 ), and contrasted to one another. Figure 1 (p. 898) and Table 4 (p. 891) in their paper are particularly helpful in understanding the differences across approaches.

It is unclear why the procedure is called the Harman test, because Harman never proposed the test and it is unlikely that he would be pleased to have his name associated with it. Greene and Organ ( 1973 ) are sometimes cited as an early application of the Harman test (they specifically mention “Harman’s test of the single-factor model,” p. 99), but they in turn refer to an article by Brewer et al. ( 1970 ), in which Harman’s one-factor test is mentioned. Brewer et al. ( 1970 ) argued that before testing the partial correlation between two variables controlling for a third variable, researchers should test whether a single-factor model can account for the correlations between the three variables, and they mentioned that one can use “a simple algebraic solution for extraction of a single factor (Harman 1960 : 122).” If measurement error is present, three measures of the same underlying factor will not be perfectly correlated, and if a single-factor model is consistent with the data, there is no need to consider a multi-factor model (which is implied by the use of partial correlations). It is clear that the article by Brewer et al. does not say anything about systematic method variance, and although Greene and Organ talk about an “artifact due to measurement error” (p. 99), they do not specifically mention systematic measurement error. Schriesheim ( 1979 ), another early application of Harman’s test, describes a factor analysis of 14 variables, citing Harman as a general factor-analytic reference, and concludes, “no general factor was apparent, suggesting a lack of substantial method variance to confound the interpretation of results” (p. 350). It appears that Schriesheim was the first to conflate Harman and testing for common method variance, although Harman was only cited as background for deciding how many factors to extract. Several years later, Podsakoff and Organ ( 1986 ) described Harman’s one-factor test as a post-hoc method to check for the presence of common method variance (pp. 536–537), although they also mention “some problems inherent in its use” (p. 536). In sum, it appears that starting with Schriesheim, the one-factor test was interpreted as a check for the presence of common method variance, although labeling the test Harman’s one-factor test seems entirely unjustified.

Ahearne, M., Haumann, T., Kraus, F., & Wieseke, J. (2013). It’s a matter of congruence: How interpersonal identification between sales managers and salespersons shapes sales success. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41 (6), 625–648.

Article Google Scholar

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14 (3), 396–402.

Arnold, T. J., Fang, E. E., & Palmatier, R. W. (2011). The effects of Customer acquisition and retention orientations on a Firm’s radical and incremental innovation performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39 (2), 234–251.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1990). Assessing method variance in Multitrait-Multimethod matrices: The case of self-reported affect and perceptions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75 (5), 547–560.

Baker, R., Blumberg, S. J., Brick, J. M., Couper, M. P., Courtright, M., Dennis, J. M., & Kennedy, C. (2010). Research synthesis AAPOR report on online panels. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74 (4), 711–781.

Baker, T. L., Rapp, A., Meyer, T., & Mullins, R. (2014). The role of Brand Communications on front line service employee beliefs, behaviors, and performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42 (6), 642–657.

Baumgartner, H., & Steenkamp, J. B. E. (2001). Response styles in marketing research: A cross-National Investigation. Journal of Marketing Research, 38 (2), 143–156.

Baumgartner, H., & Weijters, B. (2017). Measurement models for marketing constructs. In B. Wierenga & R. van der Lans (Eds.), Springer Handbook of marketing decision models . New York: Springer.

Google Scholar

Bell, S. J., Mengüç, B., & Widing II, R. E. (2010). Salesperson learning, Organizational learning, and retail store performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38 (2), 187–201.

Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44 (2), 175–184.

Berinsky, A. J. (2008). Survey non-response. In W. Donsbach & M. W. Traugott (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Public Opinion research (pp. 309–321). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Chapter Google Scholar

Brewer, M. B., Campbell, D. T., & Crano, W. D. (1970). Testing a single-factor model as an alternative to the misuse of partial correlations in hypothesis-testing research. Sociometry, 33 (1), 1–11.

Carmines, E. G., and Zeller, R.A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences , no. 07-017. Beverly Hills: Sage.

CASRO. (2015). Annual CASRO benchmarking financial survey.

Cote, J. A., & Buckley, M. R. (1987). Estimating trait, method, and error variance: Generalizing across 70 construct validation studies. Journal of Marketing Research, 24 (3), 315–318.

Curtin, R., Presser, S., & Singer, E. (2005). Changes in telephone survey nonresponse over the past quarter century. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69 (1), 87–98.

De Jong, A., De Ruyter, K., & Wetzels, M. (2006). Linking employee confidence to performance: A study of self-managing service teams. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34 (4), 576–587.

Diamantopoulos, A., Riefler, P., & Roth, K. P. (2008). Advancing formative measurement models. Journal of Business Research, 61 (12), 1203–1218.

Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1998). Common methods bias: Does common methods variance really bias results? Organizational Research Methods, 1 (4), 374–406.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (3), 39–50.

Goodman, J. K., Cryder, C. E., & Cheema, A. (2013). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of Mechanical Turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26 (3), 213–224.

Graesser, A. C., Wiemer-Hastings, K., Kreuz, R., Wiemer-Hastings, P., & Marquis, K. (2000). QUAID: A questionnaire evaluation aid for survey methodologists. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 32 (2), 254–262.

Graesser, A. C., Cai, Z., Louwerse, M. M., & Daniel, F. (2006). Question understanding aid (QUAID) a web facility that tests question comprehensibility. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70 (1), 3–22.

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60 , 549–576.

Greene, C. N., & Organ, D. W. (1973). An evaluation of causal models linking the received role with job satisfaction. Administrative Science Quarterly , 95-103.

Grégoire, Y., & Fisher, R. J. (2008). Customer betrayal and retaliation: When your best customers become your worst enemies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36 (2), 247–261.

Groves, R. M. (2006). Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70 (5), 646–675.

Groves, R. M., & Couper, M. P. (2012). Nonresponse in household interview surveys . New York: Wiley.

Groves, R. M., Couper, M. P., Lepkowski, J. M., Singer, E., & Tourangeau, R. (2004). Survey methodology (Second ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Harman, H. H. (1960). Modern factor analysis . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47 , 153–161.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43 (1), 115–135.

Hillygus, D. S., Jackson, N., & Young, M. (2014). Professional respondents in non-probability online panels. In M. Callegaro, R. Baker, J. Bethlehem, A. S. Goritz, J. A. Krosnick, & P. J. Lavrakas (Eds.), Online panel research: A data quality perspective (pp. 219–237). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of Management, 21 (5), 967–988.

Huber, J., Kamakura, W., & Mela, C. F. (2014). A topical history of JMR. Journal of Marketing Research, 51 (1), 84–91.

Hughes, D. E., Le Bon, J., & Rapp, A. (2013). Gaining and leveraging Customer-based competitive intelligence: The pivotal role of social capital and salesperson adaptive selling skills. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41 (1), 91–110.

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in Strategic Management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20 (2), 195–204.

Jap, S. D., & Anderson, E. (2004). Challenges and advances in marketing strategy field research. In C. Moorman & D. R. Lehman (Eds.), Assessing marketing strategy performance (pp. 269–292). Cambridge: Marketing Science Institute.

Jarvis, C. B., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2003). A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 30 (2), 199–218.

Kamakura, W. A. (2001). From the Editor. Journal of Marketing Research, 38 , 1–2.

Kammeyer-Mueller, J., Steel, P. D., & Rubenstein, A. (2010). The other side of method bias: The perils of distinct source research designs. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45 (2), 294–321.

Kemery, E. R., & Dunlap, W. P. (1986). Partialling factor scores does not control method variance: A reply to Podsakoff and Todor. Journal of Management, 12 (4), 525–530.

Lance, C. E., Dawson, B., Birkelbach, D., & Hoffman, B. J. (2010). Method effects, measurement error, and substantive conclusions. Organizational Research Methods, 13 (3), 435–455.

Lenzner, T. (2012). Effects of survey question comprehensibility on response quality. Field Methods, 24 (4), 409–428.

Lenzner, T., Kaczmirek, L., & Lenzner, A. (2010). Cognitive burden of survey questions and response times: A psycholinguistic experiment. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24 (7), 1003–1020.

Lenzner, T., Kaczmirek, L., & Galesic, M. (2011). Seeing through the eyes of the respondent: An eye-tracking study on survey question comprehension. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 23 (3), 361–373.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (1), 114–121.

Lohr, S. (1999). Sampling: Design and analysis . Pacific Grove: Duxbury Press.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Jarvis, C. B. (2005). The problem of measurement model misspecification in Behavioral and Organizational research and some recommended solutions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 (4), 710.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and Behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Quarterly, 35 (2), 293–334.

Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17 (3), 437–455.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric methods (Second ed.). New York: McGraw Hill.

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45 (4), 867–872.

Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., & Clark, M. A. (2002). Substantive and operational issues of response bias across levels of analysis: An example of climate-satisfaction relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87 (2), 355–368.

Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision making, 5 (5), 411–419.

Phillips, L. W. (1981). Assessing measurement error in key informant reports: A methodological note on Organizational analysis in marketing. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 , 395–415.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in Organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12 (4), 531–544.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in Behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social Science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63 , 539–569.

Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Research Methods, 12 (4), 762–800.

Rindfleisch, A, & Antia, K. D. (2012). Survey research in B2B marketing: Current challenges and emerging opportunities. In G. L. Lilien, & R. Grewal (Eds.), Handbook of Business-to-Business marketing (pp 699–730). Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Rindfleisch, A., Malter, A. J., Ganesan, S., & Moorman, C. (2008). Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. Journal of Marketing Research, 45 (3), 261–279.

Rossiter, J. R. (2002). The C-OAR-SE procedure for scale development in marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19 (4), 305–335.

Schaller, T. K., Patil, A., & Malhotra, N. K. (2015). Alternative techniques for assessing common method variance: An analysis of the theory of planned behavior research. Organizational Research Methods, 18 (2), 177–206.

Schriesheim, C. A. (1979). The similarity of individual directed and group directed leader behavior descriptions. Academy of Management Journal., 22 (2), 345–355.

Schuman, H., & Presser, N. (1981). Questions and answers in attitude surveys . New York: Academic.

Schwarz, N., Groves, R., & Schuman, H. (1998). Survey methods. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. 1, 4th ed., pp. 143–179). New York: McGraw Hill.

Simmering, M. J., Fuller, C. M., Richardson, H. A., Ocal, Y., & Atinc, G. M. (2015). Marker variable choice, reporting, and interpretation in the detection of common method variance: A review and demonstration. Organizational Research Methods, 18 (3), 473–511.

Song, M., Di Benedetto, C. A., & Nason, R. W. (2007). Capabilities and financial performance: The moderating effect of Strategic type. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35 (1), 18–34.

Stock, R. M., & Zacharias, N. A. (2011). Patterns and performance outcomes of innovation orientation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39 (6), 870–888.

Sudman, S., Bradburn, N. M., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Thinking about answers: The application of cognitive processes to survey methodology . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Summers, J. O. (2001). Guidelines for conducting research and publishing in marketing: From conceptualization through the review process. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29 (4), 405–415.

The American Association for Public Opinion Research. (2016). Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys (9th ed.) AAPOR.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Voorhees, C. M., Brady, M. K., Calantone, R., & Ramirez, E. (2016). Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (1), 119–134.

Wall, T. D., Michie, J., Patterson, M., Wood, S. J., Sheehan, M., Clegg, C. W., & West, M. (2004). On the validity of subjective measures of company performance. Personnel Psychology, 57 (1), 95–118.

Wei, Y. S., Samiee, S., & Lee, R. P. (2014). The influence of organic Organizational cultures, market responsiveness, and product strategy on firm performance in an emerging market. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42 (1), 49–70.

Weijters, B., Baumgartner, H., & Schillewaert, N. (2013). Reversed item bias: An integrative model. Psychological Methods, 18 (3), 320–334.

Weisberg, H. F. (2005). The Total survey error approach: A guide to the new Science of survey research . Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Wells, W. D. (1993). Discovery-oriented consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 19 (4), 489–504.

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13 (3), 477–514.

Winship, C., & Mare, R. D. (1992). Models for sample selection bias. Annual Review of Sociology, 18 (1), 327–350.

Wittink, D. R. (2004). Journal of marketing research: 2 Ps. Journal of Marketing Research, 41 (1), 1–6.

Zinkhan, G. M. (2006). From the Editor: Research traditions and patterns in marketing scholarship. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34 , 281–283.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The constructive comments of the Editor-in-Chief, Area Editor, and three reviewers are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, 104 Brooks Hall, Athens, GA, 30602, USA

John Hulland

Smeal College of Business, Penn State University, State College, PA, USA

Hans Baumgartner

D’Amore-McKim School of Business, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA

Keith Marion Smith

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to John Hulland .

Additional information

Aric Rindfleisch served as Guest Editor for this article.

Putting the Harman test to rest

A moment’s reflection will convince most researchers that the following two assumptions about method variance are entirely unrealistic: (1) most of the variation in ratings made in response to items meant to measure substantive constructs is due to method variance, and (2) a single source of method variance is responsible for all of the non-substantive variation in ratings. No empirical evidence exists to support these assumptions. Yet when it comes to testing for the presence of unwanted method variance in data, many researchers suspend disbelief and subscribe to these implausible assumptions. The reason, presumably, is that doing so conveniently satisfies two desiderata. First, testing for method variance has become a sine qua non in certain areas of research (e.g., managerial studies), so it is essential that the research contain some evidence that method variance was evaluated. Second, basing a test of method variance on procedures that are strongly biased against detecting method variance essentially guarantees that no evidence of method variance will ever be found in the data.

Although various procedures have been proposed to examine method variance, the most popular is the so-called Harman one-factor test, which makes both of the foregoing assumptions. Footnote 14 While the logic underlying the Harman test is convoluted, it seems to go as follows: If a single factor can account for the correlation among a set of measures, then this is prima facie evidence of common method variance. In contrast, if multiple factors are necessary to account for the correlations, then the data are free of common method variance. Why one factor indicates common method variance and not substantive variance (e.g., several substantive factors that lack discriminant validity), and why several factors indicate multiple substantive factors and not multiple sources of method variance remains unexplained. Although it is true that “if a substantial amount of common method variance is present, either (a) a single factor will emerge from the factor analysis, or (b) one ‘general’ factor will account for the majority of the covariance in the independent and criterion variables” (Podsakoff and Organ 1986 , p. 536), it is a logical fallacy (i.e., affirming the consequent) to argue that the existence of a single common factor (necessarily) implicates common method variance.

Apart from the inherent flaws of the test, several authors have pointed out various other difficulties associated with the Harman test (e.g., see Podsakoff et al. 2003 ). For example, it is not clear how much of the total variance a general factor has to account for before one can conclude that method variance is a problem. Furthermore, the likelihood that a general factor will account for a large portion of the variance decreases as the number of variables analyzed increases. Finally, the test only diagnoses potential problems with method variance but does not correct for them (e.g., Podsakoff and Organ 1986 ; Podsakoff et al. 2003 ). More sophisticated versions of the test have been proposed, which correct some of these shortcoming (e.g., if a confirmatory factor analysis is used, explicit tests of the tenability of a one-factor model are available), but the faulty logic of the test cannot be remedied.

In fact, the most misleading application of the Harman test occurs when the variance accounted for by a general factor is partialled from the observed variables. Since it is likely that the general factor contains not only method variance but also substantive variance, this means that partialling will not only remove common method variance but also substantive variance. Although researchers will most often argue that common method variance is not a problem since partialling a general factor does not materially affect the results, this conclusion is also misleading, because the test is usually conducted in such a way that the desired result is favored. For example, in most cases all loadings on the method factor are restricted to be equal, which makes the questionable assumption that the presumed method factor influences all observed variables equally, even though this assumption is not imposed for the trait loadings.

In summary, the Harman test is entirely non-diagnostic about the presence of common method variance in data. Researchers should stop going through the motions of conducting a Harman test and pretending that they are performing a meaningful investigation of systematic errors of measurement.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H. & Smith, K.M. Marketing survey research best practices: evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 46 , 92–108 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0532-y

Download citation

Received : 19 August 2016

Accepted : 29 March 2017

Published : 10 April 2017

Issue Date : January 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0532-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Survey research

- Best practices

- Literature review

- Survey error

- Common method variance

- Non-response error

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

Why Submit?

- About Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology

- About the American Association for Public Opinion Research

- About the American Statistical Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Editors-in-Chief

Kristen Olson

Katherine Jenny Thompson

Editorial board

Call for Submissions

The Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology invites submissions for a future special issue on Survey Research from Asia-Pacific, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Learn more about the topic and submit your paper through September 30, 2024 .

Latest articles

Latest posts on x.

Latest Virtual Issue

Enjoy a new special virtual issue featuring articles relating to Small Area Estimation Methods and Applications, curated by the JSSAM editors.

Virtual Issues

These specially curated, themed collections from JSSAM feature a selection of papers previously published in the journal.

Browse all virtual issues

Email alerts

Register to receive table of contents email alerts as soon as new issues of Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology are published online.

Publish in JSSAM

Want to publish in Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology ? The journal publishes articles on statistical and methodological issues for sample surveys, censuses, administrative record systems, and other related data.

View instructions to authors

Related Titles

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2325-0992

- Copyright © 2024 American Association for Public Opinion Research

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

How U.S. Public Opinion Has Changed in 20 Years of Our Surveys

When The Pew Charitable Trusts created Pew Research Center in 2004, we were surveying Americans using the established industry method at the time: calling people on their landline phones and hoping they’d answer. As the Center marks its 20th anniversary this year, survey methods have become more diverse , and we now conduct most of our interviews online .

Public opinion itself has also changed in major ways over the last 20 years, just as the country and world have. In this data essay, we’ll take a closer look at how Americans’ views and experiences have evolved on topics ranging from technology and politics to religion and social issues.

To mark Pew Research Center’s 20th anniversary, this data essay summarizes key shifts in public opinion and national demographics between 2004 and 2024. The essay is based on survey data from the Center and the U.S. Census Bureau. Links to these sources are available in the text. The links to the Center surveys include information about their field dates, sample sizes and other methodological details.

All references to Republicans and Democrats in this analysis include independents who lean toward each party. White, Black and Asian racial categories reflect people who identify as single-race and non-Hispanic. Hispanics are of any race.

The rise of the internet, smartphones and social media

The past two decades have witnessed the emergence of all sorts of technologies that let people interact with the world in new ways. For instance, 63% of U.S. adults used the internet in 2004, and 65% owned a cellphone (we weren’t yet asking about smartphones). Today, 95% of U.S. adults browse the internet, and 90% own a smartphone, according to our surveys.

Social media was just taking off in 2004, the year Mark Zuckerberg launched “The Facebook” (as it was known then) from his Harvard dorm room. Since then, Americans have widely adopted social media . These platforms have also become a key source of news for the U.S. public, even as concerns about misinformation and national security have grown.

Meanwhile, many traditional news organizations have struggled. In 2004, daily weekday newspaper circulation in the U.S. totaled around 55 million. By 2022, that had fallen to just under 21 million. Newspapers’ advertising dollars and employee counts have also decreased.

In this more fragmented news environment, Americans – particularly Republicans – have become less trusting of the information that comes from news organizations. On the whole, however, more people still say they trust information from news organizations than from social media.

Other emerging technologies

Some technological changes over the past 20 years haven’t been as widely adopted, and a few still sound like science fiction. For example, Elon Musk announced this year that his company Neuralink had implanted a computer chip in a living person’s brain. The chip is intended to allow people to use phones or computers simply by thinking about what they want to do on the devices – an idea that Americans are largely hesitant about .

Other innovations we’ve surveyed about that might have seemed far-fetched back in 2004 include driverless passenger vehicles , space tourism , AI chatbots like ChatGPT, and gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of developing serious health conditions. Our research suggests that Americans are still getting introduced to and forming opinions of these technologies, so we’ll likely see public attitudes evolve on these and other innovations over the next 20 years.

Declining trust in national institutions

Around the Center’s founding in 2004, 36% of Americans said they trusted the federal government to do what is right just about always or most of the time. By April 2024, just 22% said the same.

This is part of a longer-term decline in trust. In 1964, 77% of Americans trusted the federal government to do the right thing all or most of the time. There have been a few periods of increased trust in the decades since, including shortly after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. But since 2008, fewer than 30% of Americans have said they trust the government to do the right thing all or most of the time.

Views of Congress and the Supreme Court have also become more negative over the past 20 years. In 2006, 53% of Americans had a favorable view of Congress , but after some ups and downs, that share fell to 26% in 2023. And the share of adults who view the nation’s highest court favorably is near its lowest mark in almost 40 years of data.

The years during and after the coronavirus pandemic have also seen a more general distrust of people who were once considered experts. Many Americans were dissatisfied with the communication they received about the pandemic from public health officials, and close to half thought officials were unprepared for the initial coronavirus outbreak in the United States. Most Americans still trust scientists to act in the public’s best interest, but fewer say this now than in 2020, especially among Republicans.

More diversity in the U.S. and its government

The U.S. has become much more diverse over the past 20 years on several measures, including immigrant status. Today, immigrants account for 13.8% of the nation’s population – near the record high from 1890 – and they have come from just about every country in the world.

Racial and ethnic diversity has also increased. Between 2004 and 2022, the U.S. population grew by 14%, according to the Census Bureau . But the Asian, Hispanic and Black populations all grew at faster rates – 74%, 55% and 22%, respectively – while the White population remained stable. As a result, the share of Americans who are White fell from 68% in 2004 to 59% in 2022. 1

As the country has become more diverse, so have its voters – and its leaders. The 118th Congress is the most racially and ethnically diverse in history, and the number of women in Congress is at an all-time high. And majorities of President Joe Biden’s judicial appointments have been women and racial or ethnic minorities, a first for any president.

Still, there’s some skepticism that women will ever achieve parity with men in political leadership. In 2023, 52% of Americans said it is only a matter of time before there are as many women in political office as men , while 46% said men will continue to hold more high political offices.

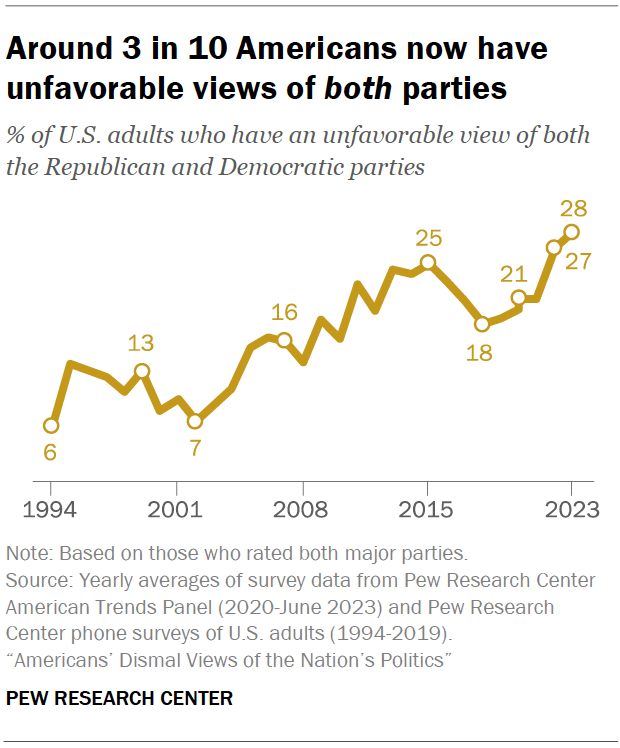

Growing dissatisfaction with the Democratic and Republican parties

In the early 2000s, very few Americans had unfavorable views of both the Democratic and Republican parties. But over the next two decades, the share saying they dislike both major parties increased, reaching 28% in 2023.

This is just one element of Americans’ broad dissatisfaction with politics . As trust in political institutions declines, few Americans now think the political system is working even somewhat well. Majorities say that most elected officials don’t care what people like them think and that ordinary people have too little influence on Congress’ decision-making. And most see little or no common ground between Republicans and Democrats on the economy, the environment, the budget deficit, immigration, gun policy or abortion.

As a result, many Americans say they regularly feel angry or exhausted when they think about U.S. politics, and very few feel hopeful and excited. When asked for the one word or phrase they’d use to describe politics today, some of the most common answers are “divisive,” “corrupt” and “messy.”

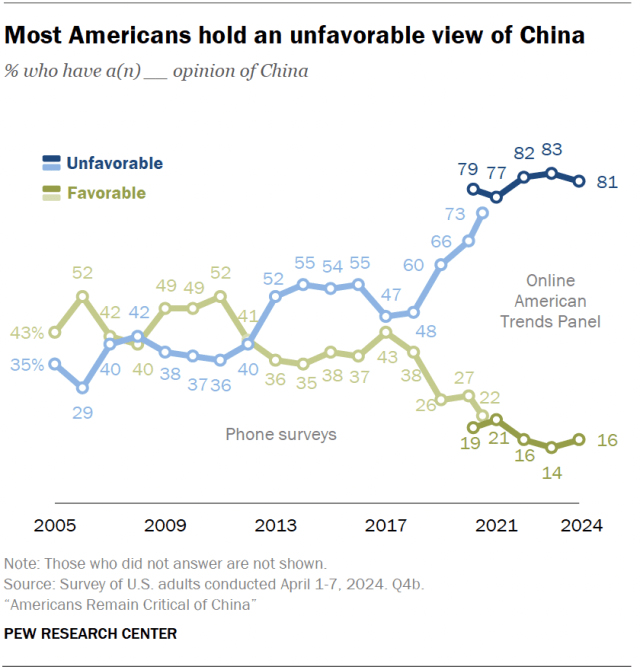

China’s emergence as a perceived threat – and even an enemy

Americans’ views of China have become increasingly negative over the past two decades. In 2005, the first year we asked this question, 35% of U.S. adults had an unfavorable view of China. Today, about eight-in-ten view China unfavorably, and about four-in-ten say it is an enemy of the U.S. , as opposed to a competitor or a partner.

In an open-ended survey question in 2023, half of Americans named China as the country that poses the greatest threat to the U.S. – about three times the share who named Russia, the second-most common answer. In contrast, China was only the third-most popular answer in 2007, behind Iran and Iraq.

The rise of the religiously unaffiliated

Many Americans describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” At the Center, we refer to this group as religious “nones.”

The share of Americans who identify as religious nones is significantly higher than it was when we began asking this question about religious identity in 2007. In recent years, the share of religious nones has mostly been stable, around 28%. But it’s too early to tell whether this population is leveling off or will continue to grow.

Still, religious nones are currently one of the largest religious groups in the United States. They trail Protestants, who make up 41% of U.S. adults, but make up a larger share of the population than Catholics (20%) and all other faiths (8%).

While they don’t identify with any organized religion, many religious nones do hold some religious or spiritual beliefs . For example, most say there is some higher power or spiritual force in the universe, though just 13% say they believe in “God as described in the Bible.”

A reversal in public opinion about same-sex marriage

The first same-sex marriages in the U.S. took place in 2004 in Massachusetts – to the consternation of both presidential candidates at the time, Republican George W. Bush and Democrat John Kerry. Their opinions reflected those of the general public: That year, 31% of Americans supported same-sex marriage , while 60% opposed it.

By 2023, attitudes on same-sex marriage had effectively flipped: 63% of Americans supported it and 34% opposed it.

The tide began to turn around 2010, when similar shares expressed support and opposition for same-sex marriage. Soon, larger shares began to favor than oppose it. And by 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark Obergefell v. Hodges ruling, which established that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry.

Since the world’s first same-sex marriages were legally recognized in the Netherlands in 2001, many places globally have followed a similar path as the U.S. International views of same-sex marriage vary, but in general, there has been increased support over the past decade. Same-sex marriage is currently legal in more than 30 places worldwide , mostly in Europe and the Americas.

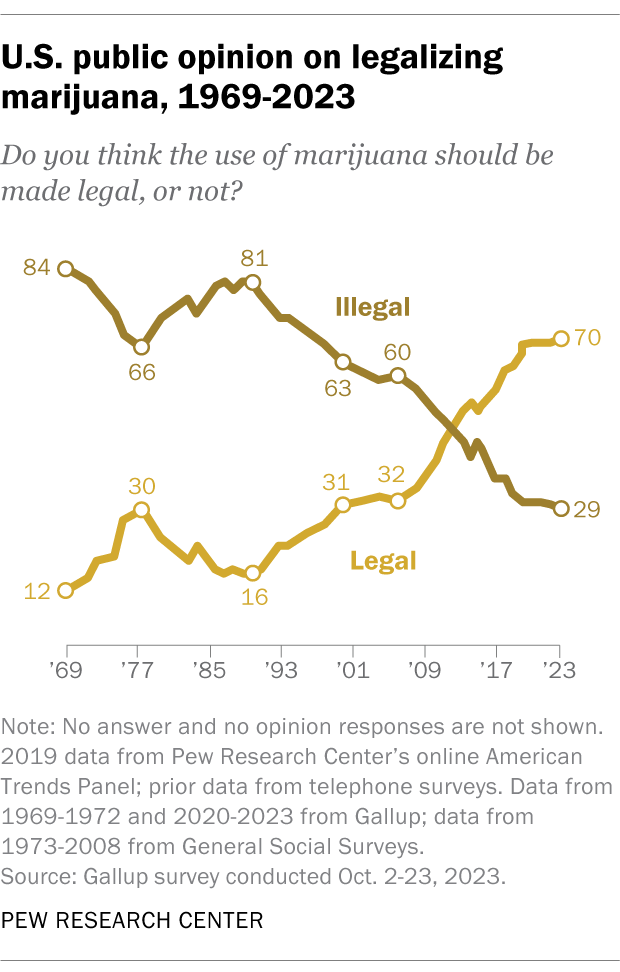

Another reversal: Marijuana legalization

Support for legalizing marijuana has also been on the rise in the U.S. over the past two decades. Around the time the Center was established in 2004, just a third of U.S. adults said marijuana should be legalized, but that rose to 70% by 2023.

The change in attitudes is even starker when looking at the longer term. In 1969, just 12% of Americans supported legalizing marijuana. It wasn’t until 1996 that any state legalized the drug for medical purposes, and it took until 2012 for states to begin legalizing it for recreational purposes.

Today, 38 states and the District of Columbia have legalized marijuana for medical and/or recreational use.

Increasingly polarized views on climate change, guns, abortion

On several issues, the pattern is not just that Americans’ views have changed markedly over the past two decades. It’s that Democrats and Republicans have grown further apart in their views, eroding areas of common ground between the parties. (In this essay, as in most Center publications, “Democrats” and “Republicans” refer to people who identify with or lean toward that party.)

Consider climate change. In 2009, Democrats were already 36 percentage points more likely than Republicans to say climate change is a major threat to the U.S. (61% vs. 25%). But by 2022, that partisan gap had grown to 55 points: 78% of Democrats, but just 23% of Republicans, considered climate change a major threat.

Globally, people in many advanced economies tend to have similar levels of concern to U.S. Democrats. A median of 75% of adults across 19 countries we surveyed in 2022 said climate change is a major threat to their country.

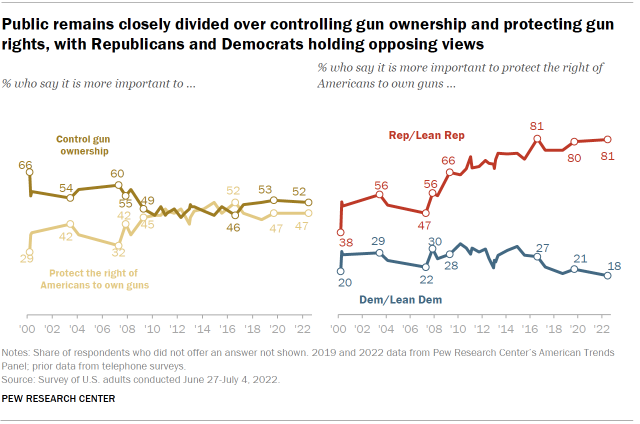

The topic of guns has become increasingly partisan , too. In 2003, 56% of Republicans and 29% of Democrats said it was more important to protect Americans’ right to own guns than to control gun ownership, a 27-point gap. But by 2022, that gap had swelled to 63 points (81% vs. 18%).

These changes coincided with major court rulings, including the Supreme Court’s 2008 decision in District of Columbia v. Heller, which held that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual’s right to have a gun.

Abortion is another subject where partisan divisions have grown. In 2007, 63% of Democrats said abortion should be legal in all or most cases. That share has grown to 85% today, following the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, which had enshrined the constitutional right to abortion in 1973.

By comparison, there has been relatively little change in opinion among Republicans: About four-in-ten continue to say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. As a result, the partisan gap has soared from 24 points in 2007 to 44 points today.

Global views vary, but support for legal abortion has generally grown over the past decade in Europe, Latin America and India. A median of 66% of adults across 27 places we surveyed now say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. In most places where we can measure political ideology on a left-right scale, people on the left are more likely than those on the right to support legal abortion. But the U.S. has by far the largest gap between the two sides.

All photos by Getty Images

- White, Black and Asian populations include those who report being only one race and are not Hispanic. Hispanics are of any race. ↩

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys

Ronald c kessler, sergio aguilar-gaxiola, jordi alonso, corina benjet, evelyn j bromet, graça cardoso, louisa degenhardt, giovanni de girolamo, rumyana v dinolova, finola ferry, silvia florescu, josep maria haro, yueqin huang, elie g karam, norito kawakami, jean-pierre lepine, daphna levinson, fernando navarro-mateu, beth-ellen pennell, marina piazza, josé posada-villa, kate m scott, dan j stein, margreet ten have, yolanda torres, maria carmen viana, maria v petukhova, nancy a sampson, alan m zaslavsky, karestan c koenen.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

CONTACT Ronald C. Kessler [email protected] Department of Health Care Policy , Harvard Medical School , 180 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA02115, USA

Received 2017 Mar 23; Revised 2017 Jun 16; Accepted 2017 Jul 6; Collection date 2017.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background : Although post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) onset-persistence is thought to vary significantly by trauma type, most epidemiological surveys are incapable of assessing this because they evaluate lifetime PTSD only for traumas nominated by respondents as their ‘worst.’

Objective : To review research on associations of trauma type with PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys, a series of epidemiological surveys that obtained representative data on trauma-specific PTSD.

Method : WMH Surveys in 24 countries (n = 68,894) assessed 29 lifetime traumas and evaluated PTSD twice for each respondent: once for the ‘worst’ lifetime trauma and separately for a randomly-selected trauma with weighting to adjust for individual differences in trauma exposures. PTSD onset-persistence was evaluated with the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

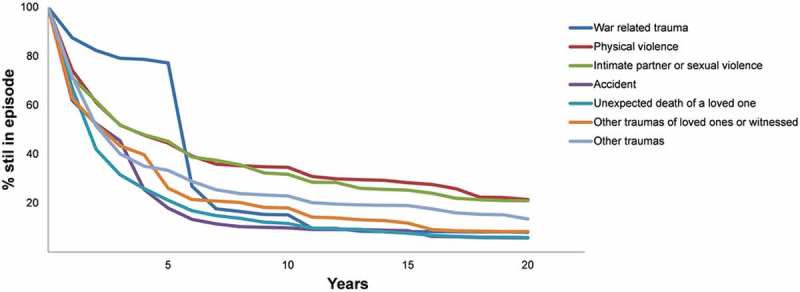

Results : In total, 70.4% of respondents experienced lifetime traumas, with exposure averaging 3.2 traumas per capita. Substantial between-trauma differences were found in PTSD onset but less in persistence. Traumas involving interpersonal violence had highest risk. Burden of PTSD, determined by multiplying trauma prevalence by trauma-specific PTSD risk and persistence, was 77.7 person-years/100 respondents. The trauma types with highest proportions of this burden were rape (13.1%), other sexual assault (15.1%), being stalked (9.8%), and unexpected death of a loved one (11.6%). The first three of these four represent relatively uncommon traumas with high PTSD risk and the last a very common trauma with low PTSD risk. The broad category of intimate partner sexual violence accounted for nearly 42.7% of all person-years with PTSD. Prior trauma history predicted both future trauma exposure and future PTSD risk.

Conclusions : Trauma exposure is common throughout the world, unequally distributed, and differential across trauma types with respect to PTSD risk. Although a substantial minority of PTSD cases remits within months after onset, mean symptom duration is considerably longer than previously recognized.

KEYWORDS: Burden of illness, disorder prevalence and persistence, epidemiology, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), trauma exposure

1. Introduction

The fact that only a small minority of people in the population develops post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Atwoli, Stein, Koenen, & McLaughlin, 2015 ) even though the vast majority are exposed to traumas at some time in their life (Benjet et al., 2016 ) has raised questions about individual differences in psychological vulnerability to PTSD. These questions are the subject of considerable research (Liberzon & Abelson, 2016 ; Sayed, Iacoviello, & Charney, 2015 ; Smoller, 2016 ). One prior consideration is the possibility that PTSD risk varies significantly by trauma type. Such differences have been documented, with highest PTSD risk thought to occur after traumas involving interpersonal violence (Caramanica, Brackbill, Stellman, & Farfel, 2015 ; Fossion et al., 2015 ). A related line of research suggests that trauma history is a risk factor for subsequent PTSD, with prior traumas involving violence again possibly of special importance (Lowe, Walsh, Uddin, Galea, & Koenen, 2014 ; Smith, Summers, Dillon, & Cougle, 2016 ). Few studies estimating these differences across trauma types did so using unbiased methods, raising questions about the validity of results regarding these differences. The issue of biasedness comes up because of a common data collection convention in general population epidemiological studies of PTSD whereby respondents are asked about lifetime exposure to each of a wide range of traumas but then assessed for PTSD only for the one trauma nominated by the respondent as their worst or most upsetting lifetime trauma. This approach makes it impossible to estimate conditional risk of PTSD after trauma exposure without upward bias because the traumas for which PTSD is assessed are atypically severe.

One approach to deal with this problem is to assess PTSD twice for epidemiological survey respondents who report experiencing multiple lifetime traumas: once for the trauma nominated by the respondent as their worst lifetime trauma and a second time for a random trauma (i.e. one randomly-selected occurrence of one randomly-selected trauma type). By weighting the random trauma reports by the inverse of their probabilities of selection at the individual level and combining these weighted reports with reports about the worst lifetime trauma, a representative sample can be generated of all lifetime traumas experienced by all survey respondents. The weight would be 1 for respondents who reported lifetime exposure to only one occurrence of one trauma type.

This weighted sample of trauma occurrences can then be used to obtain estimates both of the distribution of trauma exposure in the population and the conditional probability of PTSD after exposure to traumas of different types. These estimates are unbiased if the model is correct, although they will still be subject to the biases of recall error. The current paper reports data on between-trauma differences in the distribution of trauma exposure by trauma type and the risk of PTSD associated with each trauma type in the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. The WMH Surveys are a series of community epidemiological surveys that used this weighting scheme to generate a representative sample of trauma occurrences in the general population of participating countries (Liu et al., 2017 ).

We begin by reporting results on overall lifetime prevalence and basic socio-demographic correlates of trauma exposure in the population. We break down traumas into a number of different types for this purpose. We then examine conditional risk of PTSD after trauma exposure and compare this risk across trauma types. We also examine a number of predictors of PTSD risk among people exposed to traumas controlling for trauma type, including socio-demographic predictors, information about prior trauma exposure, and information about history of mental disorder before exposure to the focal trauma. Next, we examine data on the typical course of PTSD; that is, on the duration of PTSD episodes. We examine the same range of predictors of duration as for onset. Finally, we combine all of the above information into a consolidated portrait of the population burden of PTSD broken down by trauma type. This consolidated portrait takes into consideration differences across traumas in prevalence, conditional risk of PTSD, and the duration of PTSD.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. sample.

The WMH Surveys are a coordinated series of cross-national community epidemiological surveys using consistent sampling, field procedures, and instruments designed to facilitate pooled cross-national analyses of prevalence and correlates of common mental disorders (Kessler & Ustun, 2008 ). The subset of 26 WMH Surveys considered in this paper are those that assessed lifetime PTSD after both worst and random traumas . Five of the surveys were carried out in low/lower-middle income countries (People’s Republic of China [PRC], Colombia, Nigeria, Peru, Ukraine), seven in upper-middle income countries (Brazil, Bulgaria, Colombia [administered after the previously-mentioned Colombian survey, when the country income rating had increased], Lebanon, Mexico, Romania, South Africa), and 14 in high income countries (Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Portugal, Spain [separate national and regional surveys], USA). Each survey was based on a multi-stage clustered area probability sample of adult household residents. Three of the 26 surveys included the urbanized area of their countries (Colombia, Mexico, Peru), and five were based in specific Metropolitan areas (Beijing and Shanghai, PRC; Sao Paulo, Brazil; Medellin, Colombia; Murcia, Spain; six cities in Japan). The Nigerian survey was restricted to specific regions and the other 17 the entire country. More details about the samples are presented in Table 1 (Stein, de Jonge, Kessler, & Scott, in press ).

WMH sample characteristics by World Bank income categories. a

a World Bank (2012) Data. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/country . Some of the WMH countries have moved into new income categories since the surveys were conducted. The income groupings above reflect the status of each country at the time of data collection. The current income category of each country is available at the preceding URL.

b NSMH (The Colombian National Study of Mental Health); NSMHW (The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing); B-WMH (The Beijing World Mental Health Survey); S-WMH (The Shanghai World Mental Health Survey); EMSMP (La Encuesta Mundial de Salud Mental en el Peru); CMDPSD (Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption); NSHS (Bulgaria National Survey of Health and Stress); MMHHS (Medellín Mental Health Household Study); LEBANON (Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs of the Nation); M-NCS (The Mexico National Comorbidity Survey); RMHS (Romania Mental Health Survey); SASH (South Africa Health Survey); NSMHWB (National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing); ESEMeD (The European Study Of The Epidemiology Of Mental Disorders); NHS (Israel National Health Survey); WMHJ 2002–2006 (World Mental Health Japan Survey); NZMHS (New Zealand Mental Health Survey); NISHS (Northern Ireland Study of Health and Stress); NMHS (Portugal National Mental Health Survey); PEGASUS-Murcia (Psychiatric Enquiry to General Population in Southeast Spain-Murcia);NCS-R (The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication).

c Most WMH Surveys are based on stratified multistage clustered area probability household samples in which samples of areas equivalent to counties or municipalities in the US were selected in the first stage followed by one or more subsequent stages of geographic sampling (e.g. towns within counties, blocks within towns, households within blocks) to arrive at a sample of households, in each of which a listing of household members was created and one or two people were selected from this listing to be interviewed. No substitution was allowed when the originally sampled household resident could not be interviewed. These household samples were selected from Census area data in all countries other than France (where telephone directories were used to select households) and the Netherlands (where postal registries were used to select households). Several WMH Surveys (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Spain-Murcia) used municipal or universal health-care registries to select respondents without listing households. The Japanese sample is the only totally un-clustered sample, with households randomly-selected in each of the 11 metropolitan areas and one random respondent selected in each sample household: 17 of the 27 surveys are based on nationally representative household samples.

d The response rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of households in which an interview was completed to the number of households originally sampled, excluding from the denominator households known not to be eligible either because of being vacant at the time of initial contact or because the residents were unable to speak the designated languages of the survey. The weighted average response rate is 70.4%

e People’s Republic of China.

f For the purposes of cross-national comparisons we limit the sample to those 18+.

g Colombia moved from the ‘lower and lower-middle income’ to the ‘upper-middle income’ category between 2003 (when the Colombian National Study of Mental Health was conducted) and 2010 (when the Medellin Mental Health Household Study was conducted), hence Colombia’s appearance in both income categories. For more information, please see footnote a .

WMH interviews were administered face-to-face in respondent homes by trained lay interviewers after obtaining informed consent using procedures approved by local Institutional Review Boards. The response rate had a weighted (by sample size) mean of 70.4% across surveys (between 45.9% in France and 97.2% in Medellin). The interviews were in two parts. Part I, administered to all respondents ( n = 125,718), assessed core DSM-IV mental disorders. Part II, administered to all Part I respondents with core disorders and a probability subsample of other respondents ( n = 68,894), assessed additional disorders and correlates. Traumas and PTSD were assessed in Part II. The analysis sample considered here includes the 50,855 Part II respondents who reported lifetime trauma exposure. As detailed elsewhere (Heeringa et al., 2008 ), this sample was weighted to match population geographic/socio-demographic distributions and to adjust for under-sampling of Part I non-cases.

2.2. Measures

Traumas : A total of 29 trauma types were assessed, with reports of lifetime exposure followed by questions about number of lifetime occurrences and age at first occurrence of each type. Traumas were divided into seven categories for purposes of analysis: seven related to war (e.g. combatant, civilian in war zone, relief worker, refugee); four related to physical violence (e.g. physically abused by a caregiver as a child, mugged); four related to intimate partner or sexual violence (raped, sexually assaulted, stalked, physically abused by a romantic partner); seven related to accidents (toxic chemical spill, other man-made disaster, natural disaster, life-threatening motor vehicle collision, other accident where the respondent accidentally caused serious injury to another person, other life-threatening accident, life-threatening illness); unexpected or traumatic death of a loved one; four related to traumas that happened to other people (child had life-threatening illness, other traumas that occurred to loved ones, witnessed physical fights at home as a child, witnessed any other trauma); and a residual category of ‘other’ traumas. The latter category included responses to two questions: (i) an open-ended question: Did you ever experience any other extremely traumatic or life-threatening event that I haven’t asked you about? that was backcoded into the other six categories whenever possible and the residual reports coded in an ‘other’ category; and (ii) a question about a ‘private’ trauma: Sometimes people have experiences they don’t want to talk about in interviews. I won’t ask you to describe anything like this but, without telling me what it was, did you ever have a traumatic event that you didn’t tell me about because you didn’t want to talk about it? As shown below, a surprisingly large number of respondents answered this question affirmatively.

PTSD : DSM-IV PTSD was assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler & Ustün, 2004 ), a fully-structured lay interview that assesses a wide range of common mental disorders. As noted in the Introduction, PTSD was assessed separately for one random occurrence of one randomly-selected trauma type reported by each respondent selected using a random numbers table for that respondent (the respondent’s random trauma ) and separately for the respondent’s self-reported worst trauma. When DSM-IV/CIDI criteria for PTSD were met, the respondent was asked how long symptoms persisted and if the symptoms were still present at the time of interview. Clinical reappraisal interviews with the SCID (Haro et al., 2006 ) blinded to CIDI diagnoses of PTSD (but instructed to focus on the same trauma as the one assessed in the CIDI in order to guarantee valid comparison of diagnoses) documented moderate CIDI–SCID concordance (Landis & Koch, 1977 ) (AUC = .69). Sensitivity and specificity were 38.3% and 99.1%, respectively, resulting in a likelihood ratio positive (Sensitivity/[1-Specificity]) of 42.0 that is well above the 10.0 typically considered definitive for a positive screen (Gardner & Altman, 2000 ). Based on these operating characteristics, a very high proportion of CIDI cases (86.1%) were confirmed by the SCID.

2.3. Analysis methods

Cross-tabulations were used to estimate the distribution of lifetime trauma exposure at the individual level and to examine the distribution of trauma exposure as well as conditional risk of PTSD associated with each trauma type in this trauma-level dataset. Means were calculated within subsamples to estimate average number of trauma occurrences given any. Discrete-time survival analysis with time-varying predictors was used to examine the socio-demographic and prior trauma predictors of each type of trauma exposure and the predictors of persistence of PTSD among cases. As noted in the Introduction, random trauma reports were weighted by the inverse of random trauma probability of selection multiplied by the respondent’s Part II weight to generate a sample representative of all traumas experienced by all respondents. Logistic regression analysis was used to examine predictors of conditional risk of PTSD among the trauma-exposed. Design-adjusted standard errors were used to assess significance of individual predictors and design-based Wald χ 2 tests to evaluate the significance of predictor sets.

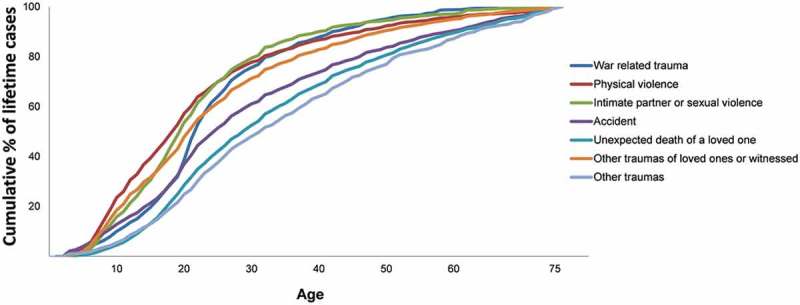

3.1. Prevalence and distribution of trauma exposure

Lifetime exposure to one or more traumas was reported by a weighted 70.4% of Part II WMH respondents ( n = 50,855, with 51,196 random and/or worst events; Table 2 ). Mean number of lifetime trauma types among those with any was 2.9, for 2.0 trauma types for capita (i.e. .704 × 2.9). The distribution of number of types among respondents with any was 32.1% one, 23.4% two, 16.6% three, 10.7% four, 6.5% five, 3.9% six, 2.5% seven, and 4.3% more than seven. By far the most common trauma types were unexpected death of a loved one (reported by 31.4% of respondents) and direct exposure to (i.e. witnessing or discovering) death or serious injury (23.7%). The next most common trauma types at the respondent level were muggings (14.5%), life-threatening automobile accidents (14.0%), and life-threatening illnesses (11.8%). ‘Private’ traumas were reported by 4.9% of respondents. When considered in terms of broader categories, the most common traumas at the respondent level were those that either occurred to a loved one or were witnessed (35.7% of respondents), those involving accidents (34.3%), and unexpected death of a loved one (31.4%) followed by physical violence (22.9%), intimate partner sexual violence (14.0%), war-related traumas (13.1%), and ‘other’ traumas (8.4%).

Prevalence and distribution of lifetime traumas in the WMH Surveys ( n = 68,894).

a The percent of all respondents who reported ever in their lifetime experiencing the trauma type indicated in the row heading. For example, 3.1% of respondents across surveys reported a history of combat experience.