REVIEW article

Poverty reduction of sustainable development goals in the 21st century: a bibliometric analysis.

- Institute of Blue and Green Development, Shandong University, Weihai, China

No Poverty is the top priority among 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The research perspectives, methods, and subject integration of studies on poverty reduction have been greatly developed with the advance of practice in the 21st century. This paper analyses 2,459 papers on poverty reduction since 2000 using VOSviewer software and R language. Our conclusions show that (1) the 21st century has seen a sharp increase in publications of poverty reduction, especially the period from 2015 to date. (2) The divergence in research quantity and quality between China and Kenya is great. (3) Economic studies focus on inequality and growth, while environmental studies focus on protection and management mechanisms. (4) International cooperation is usually related to geographical location and conducted by developed countries with developing countries together. (5) Research on poverty reduction in different regions has specific sub-themes. Our findings provide an overview of the state of the research and suggest that there is a need to strengthen the integration of disciplines and pay attention to the contribution of marginal disciplines to poverty reduction research in the future.

Introduction

Global sustainable development is the common target of human society. “No Poverty” and “Zero Hunger” are two primary goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs) , along with important premises in the completion of the goals of “Decent Work and Economic Growth Industry” and “Innovation and Infrastructure.” China has made great efforts in meeting its No Poverty targets. To achieve the goal of eliminating extreme poverty in the rural areas by the end of2020 1 , China has been carrying out a basic strategy of targeted approach named Jingzhunfupin 2 , which refers to implementing accurate poverty identification, accurate support, accurate management and tracking. By 2021, China accomplished its poverty alleviation target for the new era on schedule and achieved a significant victory 3 .

However, the worldwide challenges are still arduous. On the one hand, the recent global poverty eradication process has been further hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The World Bank shows that global extreme poverty rose in 2020 for the first time in over 20 years, with the total expected to rise to about 150 million by the end of 2021 4 . People “return to poverty” are emerging around the world. On the other hand, people who got out of income poverty may still be trapped in deprivations in health or education. About 1.3 billion people (22%) still live in multidimensional poverty among 107 developing countries, according to the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index report released by the United Nations 5 . Meanwhile, the issue of inequality became more prominent, reflected by the number of people who are in relative poverty 6 .

In line with the dynamic poverty realities, the focusing of poverty research moved forward as well. Research frameworks have evolved from single dimension poverty to multidimensional poverty ( Bourguignon et al., 2019 ) and from income poverty to capacity poverty ( Zhou et al., 2021 ). Research perspectives concentrate on the macroscopic view, but have now turned to microscopic individual behavior analysis. Cross-integration of sociology, psychology, public management, and other disciplines also helps to expand and deepen the research ( Addison et al., 2008 ). Some cutting-edge researchers are making effort to shed light on the relationships between “No Poverty” and other SDGs. For example, Hubacek et al. (2017) verified the coherence of climate targets and achieving poverty eradication from a global perspective 7 . Li et al. (2021) discussed the impacts and synergies of achieving different poverty eradication goals on air pollutants in China. These novel papers give us insightful inspiration on combining poverty reduction with the resource or environmental problem including aspects like energy inequity, carbon emission. Hence, summarizing the research on different poverty realities and academic backgrounds should provide theoretical and empirical guidance for speeding up the elimination of poverty in the world ( Chen and Ravallion, 2013 ).

Previous review literature on poverty reduction all directed certain sub-themes. For example, Chamhuri et al. (2012) , Kwan et al. (2018) , Mahembe et al. (2019a) reviewed urban poverty, foreign aid, microfinance, and other topics, identifying the objects, causes, policies, and mechanisms of poverty and poverty reduction. Another feature of the review literature is that scholars often synthesize the articles and map the knowledge network manually, which constrains the amount of literature to be analyzed, leading to an inadequate understanding of poverty research. Manually literature review on specific fields of poverty reduction results in a research gap. Analysis delineating the general academic knowledge of poverty reduction is somewhat limited despite the abundance of research. Yet, following the trend toward scientific specialization and interdisciplinary viewpoints, the core and the periphery research fields and their connections have not been clearly described. Different studies are in a certain degree of segmentation because scholars have separately conducted studies based on their countries’ unique poverty background or their subdivision direction. Possibly, lacking communication and interaction will affect the overall development of poverty reduction research especially in the context of globalization. Less than 10 years are left to accomplish the UN sustainable development goals by 2030. It is urgent to view the previous literature from a united perspective in this turbulent and uncertain age.

Encouragingly, with advances in analytical technology, bibliometrics has become increasingly popular for developing representative summaries of the leading results ( Merediz-Solà and Bariviera, 2019 ). It has been widely applied in a variety of fields. In the domain of poverty study, Amarante et al. (2019) adopted the bibliometric method and reviewed thousands of papers on poverty and inequality in Latin America. Given above issues, we expand the scope of the literature and conduct a systematic bibliometric analysis to make a preliminary description of the research agenda on poverty reduction.

This paper presents an analysis of publications, keywords, citations, and the networks of co-authors, co-words, and co-citations, displaying the research status of the field, the hot spots, and evolution through time. We use R language and VOSviewer software to process and visualize data. Our contributions may be as follows. Firstly, we used the bibliometric method and reviewed thousands of papers together, helping keep pace with research advances in poverty alleviation with the rapid growth in the literature. Secondly, we clarified the core and periphery research areas, and their connections. These may be beneficial to handle the trend toward scientific specialization, as well as fostering communication and cooperation between disciplines, mitigating segmentation between the individual studies. Thirdly, we also provided insightful implications for future research directions. Discipline integration, intergenerational poverty, heterogeneous research are the directions that should be paid attention to.

The structure of this article is as follows. Methodology and Initial Statistics provides the methodology and initial statistics. Bibliometric Analysis and Network Analysis offer the bibliometric analysis and network visualization. The remaining sections offer discussions and conclusions.

Methodology and Initial Statistics

Bibliometrics, a library and information science, was first proposed by intelligence scientist Pritchard in 1969 ( Pritchard, 1969 ). It exploits information about the literature such as authors, keywords, citations, and institutions in the publication database. Bibliometric analyses can systematically and quantitatively analyze a large number of documents simultaneously. They can highlight research hotspots and detects research trends by exploring the time, source, and regional distribution of literature. Thus, bibliometric analyses have been widely used to help new researchers in a discipline quickly understand the extent of a topic ( Merediz-Solà and Bariviera, 2019 ).

Research tools such as Bibexcel, Histcite, Citespace, and Gephi have been created for bibliometric analysis. In this paper, R language and VOSviewer software are adopted. R language provides a convenient bibliometric analysis package for Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed databases, by which mathematical statistics were performed on authors, journals, countries, and keywords. VOSviewer software provides a convenient tool for co-occurrence network visualization, helping map the knowledge structure of a scientific field ( Van Eck and Waltman, 2010 ).

Data Collection

The bibliometric data was selected and downloaded from the Web of Science database ( www.webofknowledge.com ). We choose the WoS Core Collection, which contained SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, and A&HCI papers to focus on high-quality papers. The data was collected on March 19, 2021.

To identify the documents, we used verb phrases and noun phrases with the meaning of poverty reduction, such as “reduce poverty” and “poverty reduction,” as search terms, because there are several different expressions of “poverty reduction.” We also considered the combinations of “no poverty” and SDGs, “zero hungry” and “SDGs.” Because the search engine will pick up articles that have nothing to do with “poverty alleviation” depending on what words are used in the abstract, we employed keyword matching. Meanwhile, to prevent missing essential work that does not require author keywords, we also searched the title. Specifically, a retrieval formula can be written as [AK = (“search term”) OR TI = (“search term”)] in the advanced search box, where AK means author keywords and TI means title. Finally, we restricted the document types to “article” to obtain clear data. Thus, papers containing search phrases in headings or author keywords were marked and were guaranteed to be close to the desired topic.

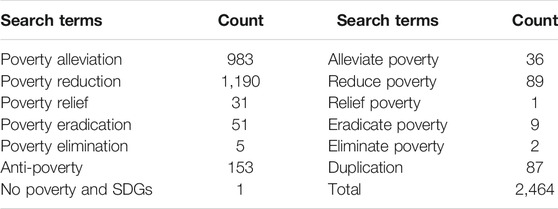

A total of 2,551 studies were obtained, with 2,464 articles retained after removing duplicates. Table 1 presents the results for each search term. The phrasing of “poverty alleviation” and “poverty reduction” are written preferences.

TABLE 1 . Information of data collection.

Descriptive Analysis

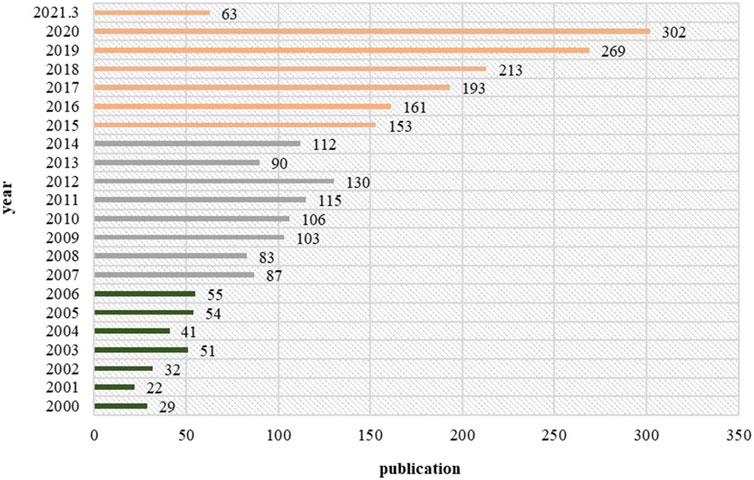

Figure 1 gives details of each year’s publications during the period 2000–2021. The cut-off points of 2006 and 2015 divide the publication trends into three stages. The first period is 2000–2006, with approximately 40 publications per year. The second period is 2007–2014, in which production is between 80 and 130 papers annually. The third period is 2015–2021, with an 18.31% annual growth rate, indicating a growing interest in this field among scholars. Perhaps this is because 2006 was the last year of the first decade for the International Eradication of Poverty, and 2015 is the year that eliminating all forms of poverty worldwide was formally adopted as the first goal in the United Nations Summit on Sustainable Development. Greater access to poverty reduction plan materials and data is a vital reason for the growth in papers as well.

FIGURE 1 . Annual scientific production.

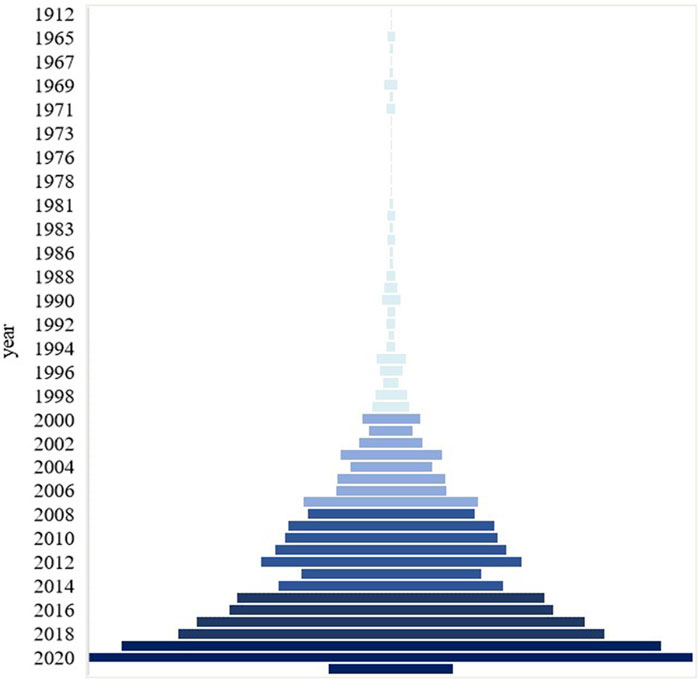

We can notice that the milestone year is 1995 when we examine the time trend with broader horizons ( Figure 2 ). Before 1995, scant literature touches upon the topic of “poverty alleviation.” This confirms that in the time range we check the majority of the development of academic interest in this issue takes place. Thus, the 21st century has become a period of booming research on poverty reduction.

FIGURE 2 . Annual scientific production in a longer period.

Bibliometric Analysis

In this section, we offer the bibliometric analysis including the affiliation statistics, citation analysis and keywords analysis. Author analysis is not included because some authors’ abbreviations have led to statistical errors.

Affiliation Statistics

From 2000 to 2021, a total of 2,459 articles were published in 979 journals, a wide range. Table 2 lists the top ten journals, which together account for 439 (17.86%) of the articles in our data set. Development in Practice and World Development have the most publications, respectively 121 (4.92%) and 107 (4.35%), followed by Sustainability at 44 (1.8%). The top 10 journals mostly involve development or social issues, with some having high impact factors, including Food Policy (4.189) and Journal of Business Ethics (4.141).

TABLE 2 . Top 10 sources of publications.

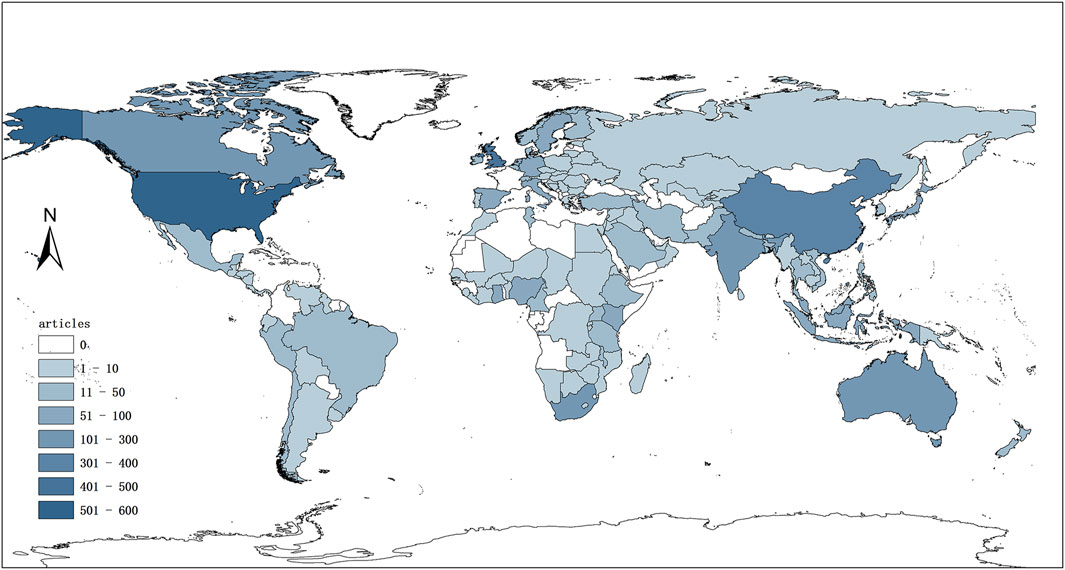

Figure 3 presents the geographic distribution of the published articles on poverty reduction. As indicated in the legend, the white part on the map shows regions with zero published articles recorded in WoS. Darker shades indicate a greater number of articles published in the country or region. The US region is darkest on the map, with 593 articles published, followed by England, with 412 papers, and China, with 348 articles. Ranking fourth is South Africa, perhaps because South Africa is a pilot site for many poverty reduction projects. India, for the same reason, is similarly shaded.

FIGURE 3 . Spatial distribution of publication in all countries. Note: the data of all countries is from Web of Science.

Citation Analysis

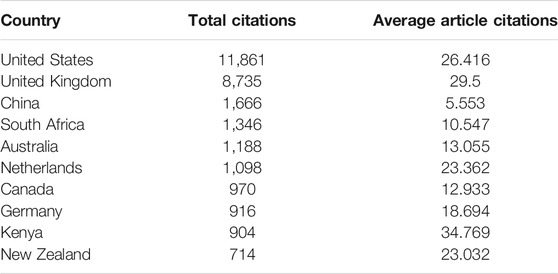

The number of citations evaluates the influence and contribution of individual papers, authors, and nations. The top 10 countries in total citations are displayed in Table 3 . Consistent with the publication distribution, the leader is the United States (11,861), with the United Kingdom (8,735) and China (1,666) following. However, there is a broad gap between China and England in total citations. The average article citation ranks are quite different from the total citation list. Notably, Kenya takes first place based on its average citations per paper, though its total citations rank seventh, showing that Kenya’s poverty reduction practices and research are of great interest to a large number of scholars. By contrast, China’s average article citation is just roughly one-sixth of Kenya’s. The different pattern of the number of Chinese publications and citations shows that the quality of Chinese research must be improved even as it raises its publication quantity.

TABLE 3 . Top ten countries by total citations.

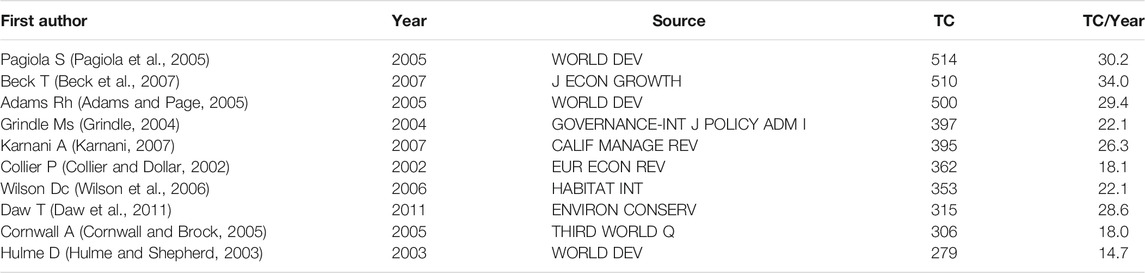

Table 4 lists the top 10 most cited articles with their first author, year, source, total citations, and total citations per year. Highly cited articles can be used as a benchmark for future research, and in some way signal the scientific excellence of each sub-field. For example, Wilson et al. (2006) reminded the importance of informal sector recycling to poverty alleviation. Daw et al. (2011) discussed the poverty alleviation benefits from ecosystem services (ES) with examples in developing countries. Pagiola et al. (2005) found that Payments for Environmental Services (PES) can alleviate poverty, and explored the key factors of this poverty mitigation effect using evidence from Latin America 8 . These three papers combined the environmental ecosystem with poverty alleviation. Beck et al. (2007) , Karnani (2007) explored the relationships between the SME sector and poverty alleviation and the private sector and poverty alleviation, respectively. Grindle (2004) discussed the necessary what, when, and how for good governance of poverty reduction. Cornwall and Brock (2005) took a critical look at how the three terms of “participation,” “empowerment” and “poverty reduction” have come to be used in international development policy. Adams and Page (2005) examined the impact of international migration and remittances on poverty. In the theory domain, Collier and Dollar (2002) derived a poverty-efficient allocation of aid. Hulme and Shepherd (2003) provided meaning for the term chronic poverty. Even from the present point of view, these scholars’ studies remain innovative and significant.

TABLE 4 . Top 10 papers with the highest total citations.

Keywords Analysis

The keywords clarify the main direction of the research and are regarded as a fine indicator for revealing the literature’s content ( Su et al., 2020 ). Two different types of keywords are provided by Web of Science. One is the author keywords, offered by the original authors, and another is the keywords plus, contrived by extracting from the cited reference. The frequency of both types of keywords in 2,459 papers is examined respectively in the whole sample and the sub-sample hereinafter for concentration and coverage.

Whole Sample

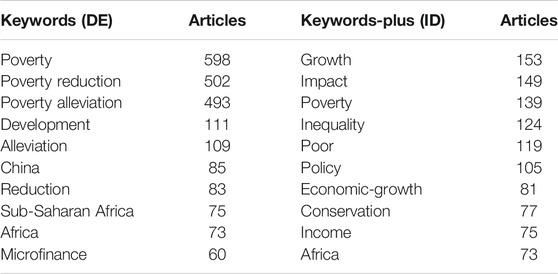

Table 5 lists the Top 10 most frequently used keywords and keyword-plus of total papers. Clearly author keywords are often repetitive, with “poverty,” “poverty reduction,” and “reduction” chosen as keywords for the same paper, but these do not dominate the keywords-plus. Hence, the keywords-plus may be more precise at identifying relevant content. However, we used author keywords for the literature screening.

TABLE 5 . Top 10 author keywords and keywords-plus with the highest frequency.

In addition to the terms “poverty” or “poverty reduction or alleviation,” we note that “China” and “Africa” occur frequently, with “India” and “Bangladesh” following when we expand the list from the Top 10 to Top 20 ( Supplementary Figure S1 ). The appearance of these places coincides with our speculation that the research was often conducted in Africa, East Asia, or South Asia once again, whereas the larger compositions are from developing countries or less developed countries.

The cumulative trend of TOP20 author keywords and keywords-plus is shown in Supplementary Figure S1 . The diagram also gives some information about other concerns bound up with anti-poverty programs, including “microfinance,” “food security,” “livelihoods,” “health,” “Economic-growth” and “income,” as numerous papers are focused on these aspects of poverty reduction.

Further, policy study and impact evaluation may be the core objectives of these papers. Vital evidence can be found in countless documents. Researchers measured the effect of policies or programs from various perspectives. In the study of Jalana and Ravallion (2003) , they indicated that ignoring foregone incomes overstated the benefits of the project when they estimated net gain from the Argentine workfare scheme. Meng (2013) found that the 8–7 plan increased rural income in China’s target counties by about 38% in 1994–2000, but had only a short-term impact 9 . Galiani and McEwan (2013) studied the heterogeneous influences of the Programa de Asignación Familiar (PRAF) program, in which implemented education cash transfer and health cash transfer to people of varying degrees of poverty in Honduran. Maulu et al. (2021) concluded that rural extension programs can provide a sustainable solution to poverty. Some studies also have drawn relatively fresh conclusions or advice on poverty reduction projects. Mahembe et al. (2019a) found that aid disbursed in production sectors, infrastructure and economic development was more effective in reducing poverty through retrospecting empirical studies of official development assistance (ODA) or foreign aid on poverty reduction. Meinzen-Dick et al. (2019) reviewed the literature on women’s land rights (WLR) and poverty reduction, but found no papers that directly investigate the link between WLR and poverty. Huang and Ying (2018) constructed a literature review that included the necessity and the ways of introducing a market mechanism to government poverty alleviation. Mbuyisa and Leonard (2017) demonstrated that information and communication technology (ICT) can be used as a tool for poverty reduction by Small and Medium Enterprises.

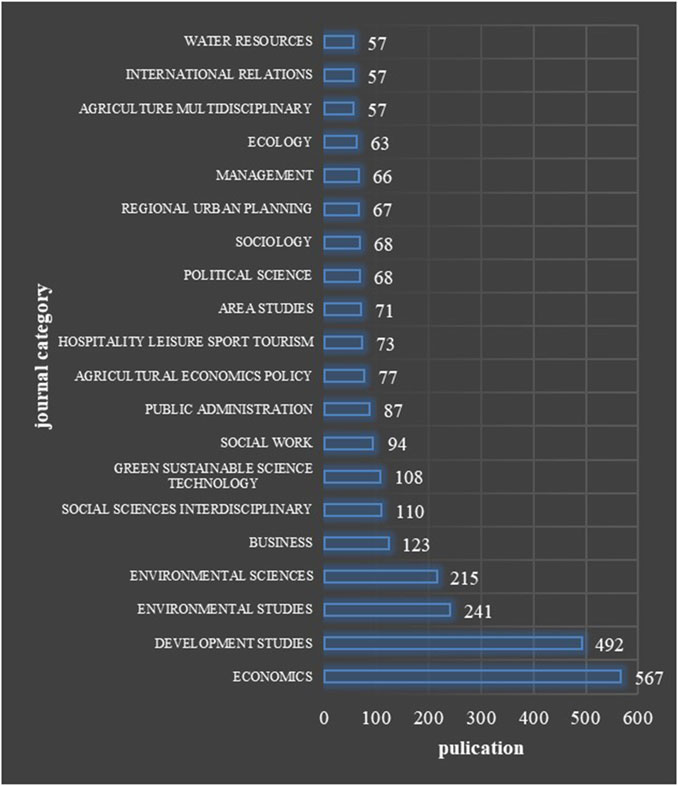

Web of Science provides the publications of each journal category ( Figure 4 ). Economics is the largest type of journal, followed by development studies and environmental studies. Education should be regarded as an important way to address the intergenerational poverty trap. However, we note that journals in education are only a fraction of the total number of journals. Psychology journals are in a similar position, though endogenous drivers of poverty reduction have been increasingly emphasized in recent research. The detailed data can be found in the supplementary documents. To investigate the differences between the subdivisions of the research, we chose economic and environmental journals as sub-samples for further analysis.

FIGURE 4 . Visualization of journal category from the web of science.

As Supplementary Figure S2 shows, the TOP10 author keywords in economic sample are similar to the whole sample. We note that microfinance is a real heated research domain both in economic and whole sample. The poor usually have multiple occupations or self-employment in very small businesses ( Banerjee and Duflo, 2007 ). The poor often have less access to formal credit. Karlan and Zinman (2011) examined a microcredit program in the Philippines and found that microcredit does expand access to informal credit and increase the ability against risk. Banerjee et al. (2015a) reported the results of an assessment of a random microcredit scheme in India, which increased the investment and profits of small-scale enterprises managed by the poor.

Several new keywords enter the TOP20 list in the economic field, including “targeting,” “income distribution,” “productivity,” “employment,” “rural poverty,” “access,” and “program.” “Targeting” is an essential topic in the economic field. It concerns the effectiveness of poverty reduction program and social fairness. Hence, an abundance of literature reviews the definitions of poverty that allow individuals to apply for poverty alleviation programs. Park et al. (2002) , Bibi and Duclos (2007) , Kleven and Kopczuk (2011) , discussed the inclusion error and exclusion error in programs’ targeting and identification under the criterion of poverty lines or specific tangible asset poverty agency indicators (e.g., whether households have color televisions, pumps or flooring, and so forth). In practice, Niehaus et al. (2013) tested the accuracy of different agency indicators to allocate Below Poverty Line (BPL) cards in India and found that using a greater number of poverty indicators led to a deterioration in targeting effectiveness while creating widespread violations in the implementation because less qualified families are more likely to pay bribes to investigators. Bardhan and Mookherjee (2005) explored the targeting effectiveness of decentralization in the implementation of anti-poverty projects. He and Wang (2017) assessed the targeting accuracy of the College Graduate Village Officials (CGVOs) project, a unique human capital redistribution policy in China, on poverty alleviation 10 .

The terms “inequality” and “growth” are first and second in the keywords-plus. This may be because inequality and growth are two of the major components in poverty changes in the economic field, which are stressed in the studies of Datt and Ravallion (1992) , Beck et al. (2007) . The ranking may also imply that the economics of the 21st century is more concerned with human welfare than the pursuit of rapid economic growth. Since a growing number of organizations are trying to build human capital to improve the livelihoods of their clients and further their mission of lifting themselves out of poverty. McKernan (2002) showed that social development programs are important components of microfinance program success. Similarly, Karlan and Valdivia (2006) argued that increasing business training can factually improve business knowledge, practice effectiveness, and revenue. Besides, cash transfers are widely adopted to reduce income inequality and improve education and the health status of poor groups ( Banerjee et al., 2015b ; Sedlmayr et al., 2020 ). Benhassine et al. (2015) noted that the Tayssir Project in Morocco, a cash transfer project, achieved an increasing improvement of school enrolment rate in the treatment group, especially for girls 11 .

We combine the journal types of “Environmental Studies” and “Environmental Sciences” into one unit for analysis ( Supplementary Figure S3 ). In the environmental field, the terms “conservation” and “management” are ranked first and second. This field also involves “ecosystem services,” “climate change,” “biodiversity conservation,” and “deforestation,” with rapid growth in recent years. These themes were discussed by Alix-Garcia et al. (2013) , Alix-Garcia et al. (2015) , Sims and Alix-Garcia (2017) in their investigations of the effect of conditional cash transfers on environmental degradation, the poverty alleviation benefits of the ecosystem service payment project, and comparison of the effects in protected areas and of ecosystem service payment on poverty reduction in Mexico. The differences in economic research in poverty reduction and environmental field show the necessity of strengthening cooperation between disciplines.

Network Analysis

Network relationship is established by the co-occurrence of two types of information. It enables mapping of the knowledge nodes with a joint perspective, instead of viewing scientific ideas in isolation. The data is imported into VOSviewer software after removing duplicates by R package. We then provide the co-authorship analysis, co-citation analysis, and co-keywords analysis.

Co-Authorship Analysis

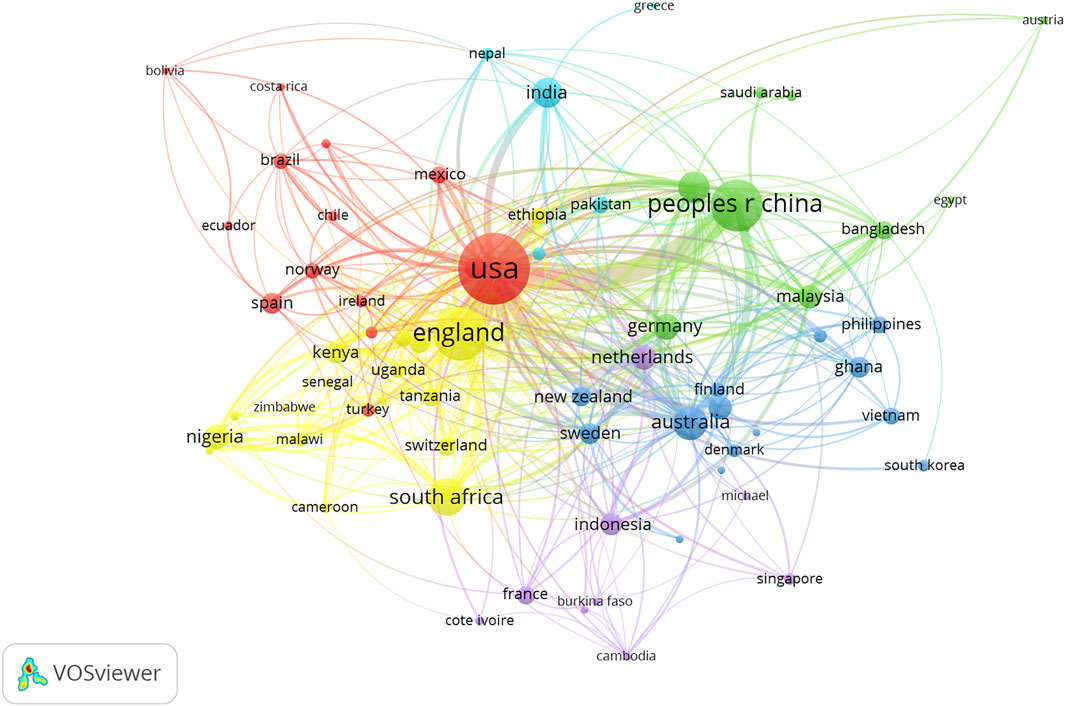

Co-authorship may reflect international cooperation as shown by the country distribution ( Figure 5 ). When the authors of two countries have a cooperative relationship, a line is generated to connect the corresponding countries. The size of nodes reflects the number of countries of origin of the authors. The width of the line represents the cooperative frequency between them, and the different colors mark the partition of the countries.

FIGURE 5 . International networks of co-authorship.

The network includes a total of 1,449 countries, of which 92 meet the threshold of at least five instances of cooperation. The United States, United Kingdom, China, and South Africa have the strongest interlinkage with other countries or regions. Whether countries in each cluster demonstrate international academic cooperation on poverty reduction is sometimes based on geographic location. For example, the red cluster includes the United States, Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and Ecuador. These countries mainly lie in the Americas. The United Kingdom, Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa are in the yellow group, located in Europe and Africa. The green cluster includes China, Malaysia, and Bangladesh, all Asian countries. The distribution of countries on each cluster and the map as a whole show that research on poverty alleviation is usually conducted by developed and developing nations together. This may be due to anti-poverty programs in developed countries usually being subsidized by international non-governmental organizations, as shown by the branch literature devoted to foreign aid and poverty reduction ( Mahembe et al., 2019b ).

Co-Citation Analysis

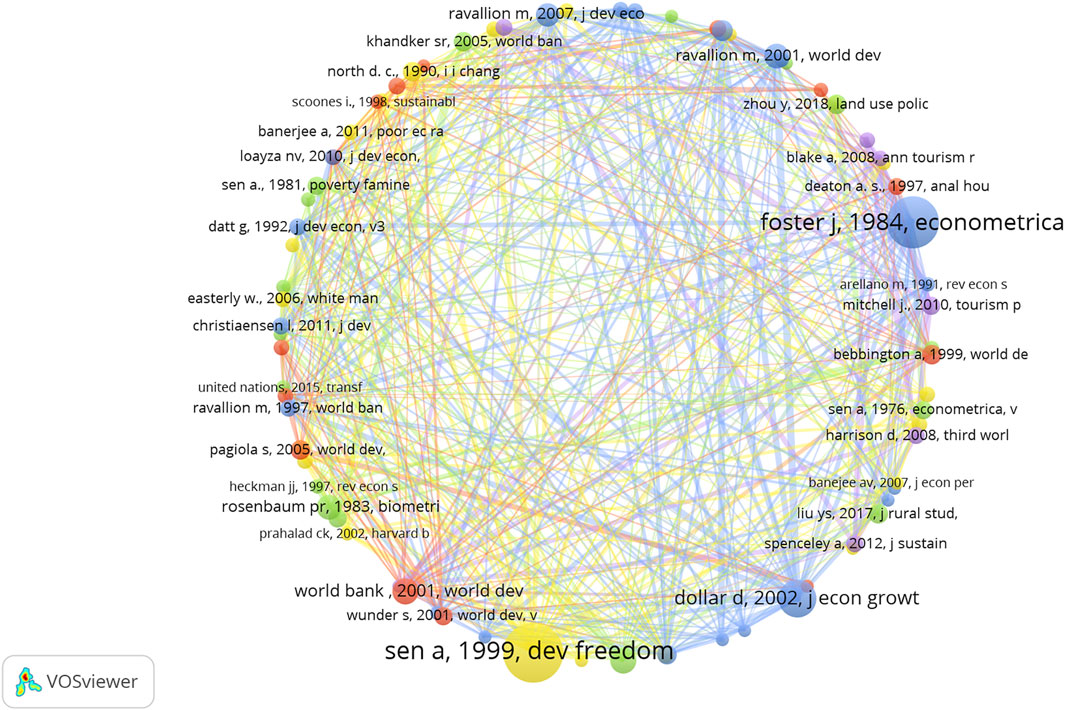

Co-citation analysis can locate the core classical literature efficiently ( Zhang et al., 2020 ). Pioneering studies of co-citation analysis were performed by Small (1973) . When an article cited two other articles, a relationship of co-citation will be established between these two “cited” articles ( González-Alcaide et al., 2016 ). Since co-citation aims at reference, it targets the knowledge base for the past.

Figure 6 displays the co-citation network of the cited references. The functions of the sizes and colors are the same as in Figure 5 . The most cited papers in the co-citation relationship are the studies of Foster et al. (1984) , Sen et al. (1999) , Dollar and Kraay (2002) , which respectively explore poverty measures, globalization and development, and the growth impact for the poor.

FIGURE 6 . Cited reference network of co-citation.

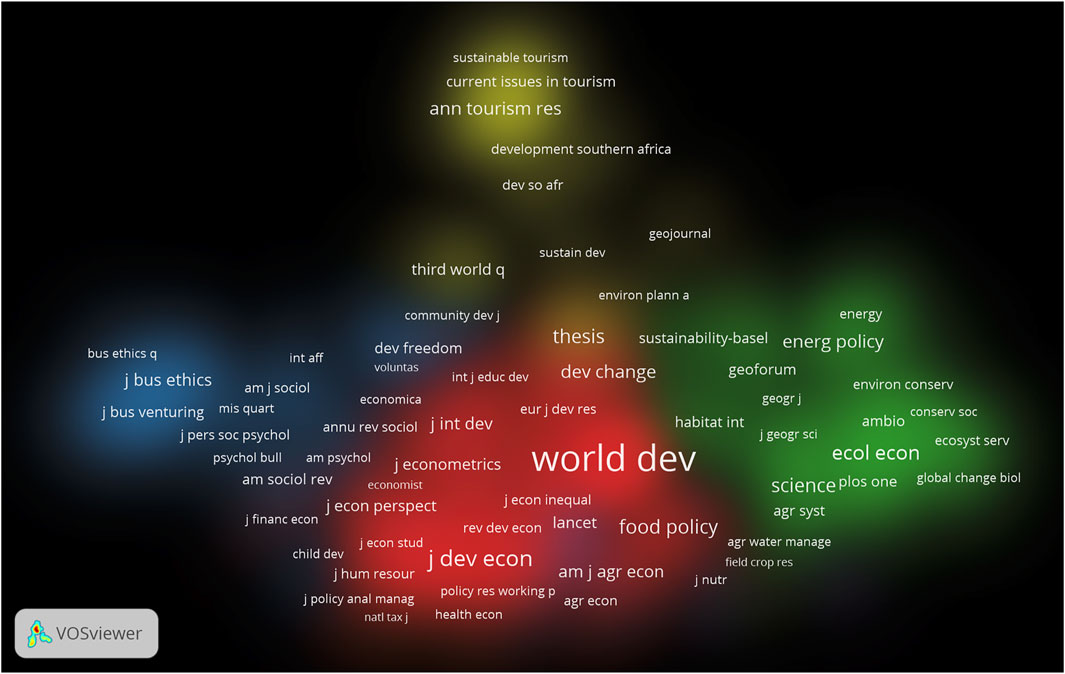

Figure 7 gives the co-citation heat map of sources, based on their density. We set the threshold at 20, and 78 cited sources remained on the map. Different colors signify different clusters of co-citation. The lighter the color, the more frequently the journals are cited. There are four major categories. World development and the Journal of Development Economics have the largest influence on the red cluster, which mainly contains development and economic studies. The second cluster is green and includes the fields of energy, environment, and ecology, with Ecology Economics as its brightest star. The Journal of Business Ethics and Annals of Tourism Research are the most-cited journals in the third and fourth cluster, which represents the fields of business and tourism. Some psychology studies exist in transitional spaces between business studies and economic studies, suggesting a trend of interdisciplinary work. In the past 10 years, we checked manually that psychology and other interdisciplinary research performed well. Many papers were published in Science or Nature. In the research of Mani et al. (2013) , there was a causal relationship between poverty and psychological function. Poverty reduced the cognitive performance of the poor, because poverty consumes spiritual resources, leaving fewer cognitive resources to guide choices and actions. Another psychology-based experiment in Togo showed that personal proactive training increased the profits of poor businesses by 30%, while traditional training influence was not significant ( Campos et al., 2017 ). In the study of Ludwig et al. (2012) , they revealed that the shift from high-poverty to low-poverty communities resulted in significant long-term improvements in physical and mental health and subjective well-being and had a continuing impact on collective efficacy and neighborhood security.

FIGURE 7 . Cited source density network of co-citation.

Co-Words Analysis

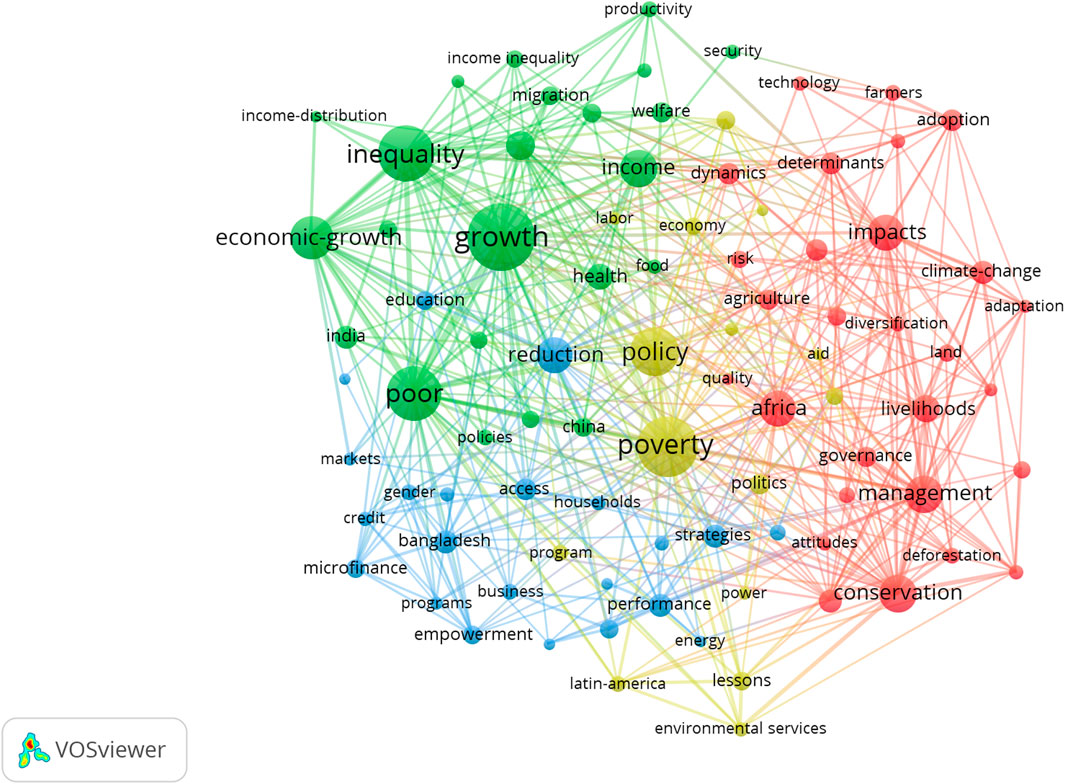

The analysis of co-words was performed after the co-citation analysis. Since it is hard to explain the changes in cluster from year to another in a co-citation map, Callon et al. (1983) proposed co-word analysis to identify and visualize scientific networks and their evolution. Based on our keyword analysis and following the arguments of Zhang et al. (2016) , the knowledge structures of author keywords and keywords plus are similar, but keywords plus can mirror a large proportion of the author keywords when the threshold of the number of instances of a word exceeds 10. The merger of two types of keywords will inflate the total number of words, leaving unique words representing the latest hot spot with little chance to be selected. Therefore, we conduct the co-word analysis using keywords plus to map the structure.

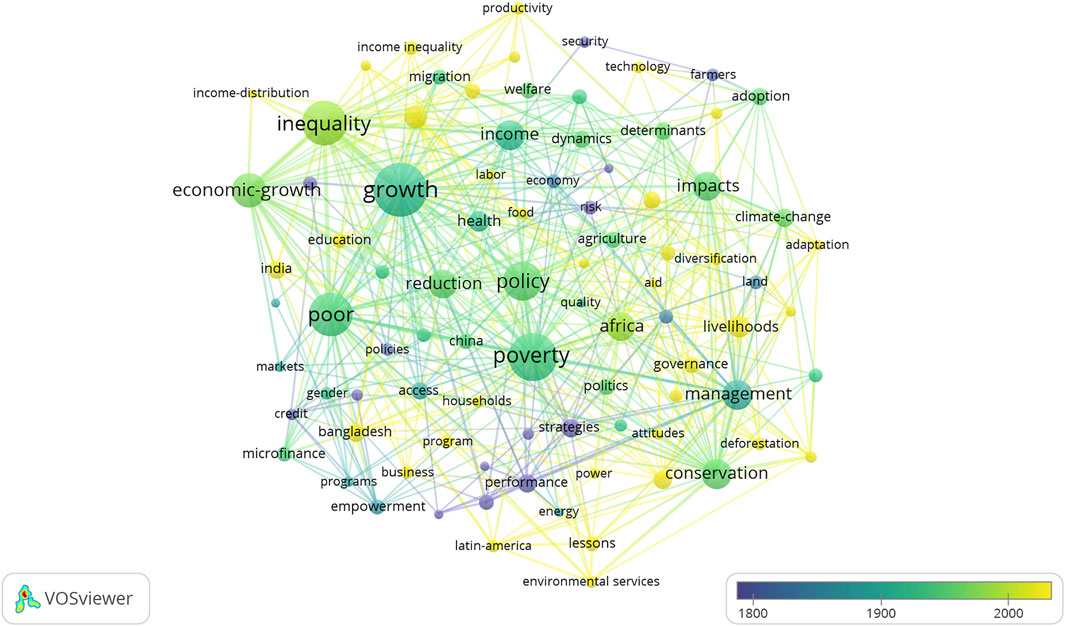

We set the minimum number of occurrences to 15, and 100 words with the greatest link strength are selected from the total of 2,774. As shown in Figure 8 , keywords plus generates 4 clusters. To our delight, each cluster does reflect the research priorities of each region.

FIGURE 8 . Keywords-plus co-occurrence cluster map.

The first cluster (red) reveals studies concerning livelihood, conservation, management, climate change and agriculture. These topics have strong interlinkage to Africa, suggesting that poverty reduction in Africa is often related to basic livelihood and ecology. The poor in Africa rely on the ecological conditions heavily as they are facing a more disadvantaged climate and resources. Therefore, their poverty reduction process is sometimes highly unstable and subject to considerable internal and external constraints. Stevenson and Irz (2009) concluded that the numerous studies presented almost no evidence of aquaculture reducing poverty directly.

The second cluster (green) represents studies focused on economic growth and income inequality, common in China and India. This pattern may imply that papers of this cluster focus on the economic conditions of the poor. Other studies in this cluster are related to migration, health, and welfare. The third cluster (blue) is the poverty reduction strategies on microfinance and empowerment, which are associated with Bangladesh where the Grameen Bank, one of the most notable and intensely researched microcredit programs, was founded ( McKernan, 2002 ). This cluster’s studies are interested in approaches such as business, markets, and education, to help the poor rise from poverty. The fourth cluster (yellow) contains studies of poverty reduction programs on environmental services in Latin America, where the environmental problem is intertwined with poverty traps.

Figure 9 shows the time trend of keywords-plus co-occurrence. Because the keywords plus are extracted from the cited references, they can reflect the changes in hotspots from relatively early to the most recent years. As can be seen, education, technology, and environmental services are the latest keywords in research on poverty reduction.

FIGURE 9 . Keywords-plus co-occurrence time trend map.

There are several limitations to our bibliometric analysis, though we undertake an extensive review of the literature. First, we inevitably lose a fraction of the literature. keywords and title are chosen as the criteria for helping precisely concentrate the search results on our subject. However, the Web of Science core collection on which our study relied is weak in the coverage of literature to some degree. Hence, there is a trade-off between the quantity and the quality of literature. We choose the latter, leading to an unclear restriction of the comprehensiveness of research. Second, we can identify recent research status but are not able to locate the Frontier accurately. Network mapping requires selecting a minimum occurrence threshold for including corresponding authors, keywords, and citations into the network. Because a certain number of citations or new hotspots take several years to be widely used and studied, this threshold may neglect these important data ( Linnenluecke et al., 2020 ). One possible solution is to manually examine the latest published papers in high-quality journals. Third, the mining of subfields is not deep enough. In other words, bibliometrics cannot sort out the main conclusions of literature on poverty reduction. For instance, we do not know whether the conclusion of different studies are consistent for the same poverty alleviation project. Neither do we know the exact mechanism of the anti-poverty program through bibliometric analysis, which limits the possibility of finding research points from controversial conclusions or mechanisms.

However, several points are worth taking into consideration for the future. To start with, poverty reduction is a natural interdisciplinary social science problem. Interdisciplinary has become a major research trend. Except applying cash transfer to ecological programs, associations are raised. We may discuss whether the combination of finance and ecology will bring positive benefits to financial stability, ecological protection, and poverty reduction by the means of capitalization of ecological resources or establishing the ecological bank. Our analysis suggests that some unheeded branch disciplines like human ethology are contributing to poverty reduction research as well. Thus, we need to investigate the interdisciplinary integration and the contribution of marginal disciplines on poverty reduction.

Then, more attention should be paid the intergenerational poverty. It requires researchers to extend the time span of observation and questionnaire investigation. Some work has been done. One example is the research of Hussain and Hanjra (2004) . They reviewed literature and clarified that advances in irrigation technologies, such as micro-irrigation systems, have strong anti-poverty potential, alleviating both temporary and chronic poverty. Another example is the research of Jones (2016) , which indicated that conditional cash transfers (CCTs) could indeed interrupt the intergenerational cycle of poverty through human capital investments. However, there remains a lot of work to be done for preventing the next generation from returning to poverty in this turbulent period. In a related matter, the role of education in isolating intergenerational poverty or returning to the poverty trap should be highlighted. What kind of education would more effectively help families out of poverty, quality education or vocational skill education? How to allocate educational resources effectively? For poor students, what kind of psychological intervention in education is needed to mitigate the impact of native families and help them grow up confidently? Lots of questions waiting for empirical answering, yet we note that the educational journal only took a little fraction of the total journals in Section 4.3.2.

Next, poverty does exist in prosperous conurbations though the focal point obtained from keywords analysis is “rural area”. Nevertheless, both the slums in the center of big cities and circulative flowing refugees are experiencing more relative deprivation, representing a state of instability. Chamhuri et al. (2012) reviewed the objects, causes, and policies of urban poverty. Exploring how to lift a particular small economic low-lying area out of poverty is also of great significance. Follow-up researches should keep up.

Moreover, poverty alleviation needs to be based on individual or group-specific characteristics to some degree. It is not feasible to implement a unified poverty alleviation policy on a large scale. Exquisitely designed randomized controlled trials are used to reveal the heterogeneous influence of poverty alleviation programs. Haushofer and Shapiro (2016) compared the difference between monthly transfers and one-time lump-sum transfers. The subdivision research on the effect of poverty reduction programs should be strengthened. We imagine that a model may be formed to predict the total poverty reduction effects of different policies in the various region to obtain an optimized strategy of “No Poverty” in the future.

Lastly, exploring whether poverty reduction will be contradictory or coordinate with other SDGs might be a popular direction. About the literature review, two aspects can be improved. The first is merging with other databases to compare the loss of the trade-off between quality and quantity. Next, subsequent literature reviews need to explore how to better combine manual literature collation and bibliometrics, especially when the subject is a large topic.

Poverty reduction is one of the objectives of welfare economics and development economics. It is a classic and lasting topic and has recently come into the limelight. Poverty reduction studies in the 21st century are usually based on specific poverty alleviation projects or policies in developing countries. Researchers examine numerous topics, including whether the target audience has been precisely identified and covered in the design and implementation process, whether poverty reduction projects have been proved effective, what mechanisms have contributed to the success of poverty reduction projects, and what caused their failure. The aim of this paper is to summarize the amount, growth trajectory, citation, and geographic distribution of the poverty reduction literature, map the intellectual structure, and highlight emerging key areas in the research domain using the bibliometric method. We use the VOSviewer software and the R language as tools to analyze 2,459 articles published since 2000.

We have several conclusions. First, the 21st century is a period of booming research on poverty reduction, and the number of publications has increased sharply since 2015. Second, in affiliation analysis, Development in Practice and World Development are the top publications. The most frequently cited source of co-citations are World Development , Ecology Economics, Journal of Business Ethics, and Annals of Tourism Research , respectively the centers of the fields of economics, energy, the environment, and ecology, business, and tourism. Third, there are differences in the national and regional distribution of literature, based on the number of publications and citations. The United States led both the publication list and the total citation list, followed by the United Kingdom, China, and South Africa. Yet, there is a huge variation in the number of citations, with the United States and the United Kingdom having almost 5 to 6 times more citations than China and South Africa. In terms of average citations, Kenya is the best performer. The average citation amount in China is low, implying that Chinese scholars need to improve the quality of their literature. Fourth, in the keyword analysis, policy discussion and impact estimation are the two major themes. The keywords related to poverty reduction are different among different disciplines. Economics pays more attention to inequality and growth, while environmental disciplines pay more attention to protection and management. This may suggest that strengthening the cooperation between disciplines will lead to more diversified research perspectives. Fifth, in the co-author analysis, international cooperation is usually related to geographical location. For example, there is a large amount of cooperation between Europe and Africa, within Asia, and between North and South America. At the same time, poverty reduction research often shows the cooperative patterns of developed and developing countries. Last, in the co-keyword analysis, four clusters reflect the research priorities of each region. Poverty reduction in Africa is often related to basic livelihood and ecology. The economic conditions of the poor are the concerns of research in China and India. The South Asia region is also the location of microcredit program experiments. Poverty traps are intertwined with environmental problems in Latin America’s literature.

Our findings also offer inspiration for the future. There may be a need to investigate the interdisciplinary integration. Intergenerational and urban poverty deserve attention. The heterogeneous design of poverty alleviation strategies needs to be further deepened. It might be a popular direction to figure out whether poverty reduction will be contradictory with other SDGs and conduct scenario simulation. We identify shortcomings as well. Finally, precisely identifying research frontiers requires further exploration.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grant number 72022009).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.754181/full#supplementary-material

1 The extreme poverty criterion set by World Bank is 1.9$ a day in purchasing power parties (PPP), https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/brief/policy-research-note-03-ending-extreme-poverty-and-sharing-prosperity-progress-and-policies . The China poverty alleviation target in 2020 is to eliminate absolute poverty, which is defined as living less than 2,300 yuan per person per day at 2010 constant prices. In addition to living above the absolute poverty line, people who must reached other five qualitative criteria can be calculated getting rid of absolute poverty, which is no worries about food, clothing, basic medical care, compulsory education and housing safety

2 Jingzhunfupin is a general term of Chinese targeted poverty alleviation work model. Opposite to the haploid poverty alleviation, different assistance policies will be formulated according to the different category of poverty, distinctive causes, dissimilar background of poor households and their divergent living environment

3 https://enapp.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202102/26/AP60382a17a310f03332f97555.html . https://www.bbc.com/news/56213271

4 https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview

5 The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) is developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) since 2010. It has been published annually by OPHI and in the Human Development Reports (HDRs) ever since. https://ophi.org.uk/multidimensional-poverty-index/

6 Relative poverty is another poverty measurement to reflect the underlying economic gradient. It is induced from the relative deprivation theory. Countries set the relative poverty line at a constant proportion of the country or year-specific mean (or median) income in practice ( https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00127 )

7 This paper mainly found that eradicating extreme poverty, i.e., moving people to an income above $1.9 purchasing power parity (PPP) a day, does not jeopardize the climate target. That is to say, the climate target and no poverty goal is consistent and coordinated

8 This paper indicated that Payments for Environmental Services may reduce poverty mainly by making payments to poor natural resource managers in upper watersheds. The effects depend on how many participants are poor, the poor’s ability to participate, and the amounts paid

9 8–7 plan is the second wave of China’s poverty alleviation program. The Leading Group renewed poverty line and the National Poor Counties list in 1993. Targeted counties received three major interventions: credit assistance, budgetary grants for investment and public employed projects (i.e., Food-for-Work).

10 In the College Graduate Village Officials (CGVOs) program, the government hire outstanding graduates to work in the rural areas, for example as the village committee secretary, to help rural development and alleviate poverty. In this paper, the College Graduate Village Officials assisted eligible poor households to understand and apply for relevant subsidies, which reduced elite capture of pro-poor programs and move forward poverty alleviation process

11 The Tayssir Project was labeled the Education Support Program, sending a positive signal of its educative value

Adams, R. H., and Page, J. (2005). Do international Migration and Remittances Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries? World Develop. 33, 1645–1669. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.05.004

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Addison, T., Hulme, D., and Kanbur, R. (2008), Poverty Dynamics: Measurement and Understanding from an Interdisciplinary Perspective. Working Paper No. 19. Brooks World Poverty Institute . Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1246882 .

Google Scholar

Alix-Garcia, J., McIntosh, C., Sims, K. R. E., and Welch, J. R. (2013). The Ecological Footprint of Poverty Alleviation: Evidence from Mexico's Oportunidades Program. Rev. Econ. Stat. 95, 417–435. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00349

Alix-Garcia, J. M., Sims, K. R. E., and Yañez-Pagans, P. (2015). Only One Tree from Each Seed? Environmental Effectiveness and Poverty Alleviation in Mexico's Payments for Ecosystem Services Program. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 7, 1–40. doi:10.1257/pol.20130139

Amarante, V., Brun, M., and Rossel, C. (2020). Poverty and Inequality in Latin America's Research Agenda: A Bibliometric Review. Dev. Pol. Rev. 38, 465–482. doi:10.1111/dpr.12429

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., and Kinnan, C. (2015). The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 7, 22–53. doi:10.1257/app.20130533

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Goldberg, N., Karlan, D., Osei, R., Parienté, W., ..., , Shapiro, J., Thuysbaert, B., and Udry, C. (2015). A Multifaceted Program Causes Lasting Progress for the Very Poor: Evidence from Six Countries. Science 348, 1260799. doi:10.1126/science.1260799

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Banerjee, A. V., and Duflo, E. (2007). The Economic Lives of the Poor. J. Econ. Perspect. 21, 141–167. doi:10.1257/089533007780095556

Bardhan, P., and Mookherjee, D. (2005). Decentralizing Antipoverty Program Delivery in Developing Countries. J. Public Econ. 89, 675–704. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.01.001

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and Levine, R. (2007). Finance, Inequality and the Poor. J. Econ. Growth 12, 27–49. doi:10.1007/s10887-007-9010-6

Benhassine, N., Devoto, F., Duflo, E., Dupas, P., and Pouliquen, V. (2015). Turning a Shove into a Nudge? A "Labeled Cash Transfer" for Education. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 7, 86–125. doi:10.1257/pol.20130225

Bibi, S., and Duclos, J.-Y. (2007). Equity and Policy Effectiveness with Imperfect Targeting. J. Develop. Econ. 83, 109–140. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.12.001

Bourguignon, F., and Chakravarty, S. R. (2019). “The Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty,” in Poverty, Social Exclusion and Stochastic Dominance. Themes in Economics (Theory, Empirics, and Policy) . Editor S. Chakravarty (Singapore: Springer ), 83–107. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-3432-0_7

Callon, M., Courtial, J.-P., Turner, W. A., and Bauin, S. (1983). From Translations to Problematic Networks: An Introduction to Co-word Analysis. Soc. Sci. Inf. 22, 191–235. doi:10.1177/053901883022002003

Campos, F., Frese, M., Goldstein, M., Iacovone, L., Johnson, H. C., McKenzie, D., et al. (2017). Teaching Personal Initiative Beats Traditional Training in Boosting Small Business in West Africa. Science 357, 1287–1290. doi:10.1126/science.aan5329

Chamhuri, N. H., Karim, H. A., and Hamdan, H. (2012). Conceptual Framework of Urban Poverty Reduction: A Review of Literature. Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 68, 804–814. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.268

Chen, S., and Ravallion, M. (2013). More Relatively-Poor People in a Less Absolutely-Poor World. Rev. Income Wealth 59 (1), 1–28. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4991.2012.00520.x

Collier, P., and Dollar, D. (2002). Aid Allocation and Poverty Reduction. Eur. Econ. Rev. 46, 1475–1500. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00187-8

Cornwall, A., and Brock, K. (2005). What Do Buzzwords Do for Development Policy? a Critical Look at 'participation', 'empowerment' and 'poverty Reduction'. Third World Q. 26, 1043–1060. doi:10.1080/01436590500235603

Datt, G., and Ravallion, M. (1992). Growth and Redistribution Components of Changes in Poverty Measures. J. Develop. Econ. 38, 275–295. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(92)90001-P

Daw, T., Brown, K., Rosendo, S., and Pomeroy, R. (2011). Applying the Ecosystem Services Concept to Poverty Alleviation: the Need to Disaggregate Human Well-Being. Envir. Conserv. 38, 370–379. doi:10.1017/S0376892911000506

Dollar, D., and Kraay, A. (2002). Growth Is Good for the Poor. J. Econ. Growth 7, 195–225. doi:10.1023/A:1020139631000

Foster, J., Greer, J., and Thorbecke, E. (1984). A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures. Econometrica 52, 761–766. doi:10.2307/1913475

Galiani, S., and McEwan, P. J. (2013). The Heterogeneous Impact of Conditional Cash Transfers. J. Public Econ. 103, 85–96. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.04.004

González-Alcaide, G., Calafat, A., Becoña, E., Thijs, B., and Glänzel, W. (2016). Co-Citation Analysis of Articles Published in Substance Abuse Journals: Intellectual Structure and Research Fields (2001-2012). J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 77, 710–722. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.710

Grindle, M. S. (2004). Good Enough Governance: Poverty Reduction and Reform in Developing Countries. Governance 17, 525–548. doi:10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00256.x

Haushofer, J., and Shapiro, J. (2016). The Short-Term Impact of Unconditional Cash Transfers to the Poor: Experimental Evidence from Kenya*. Q. J. Econ. 131, 1973–2042. doi:10.1093/qje/qjw025

He, G., and Wang, S. (2017). Do college Graduates Serving as Village Officials Help Rural China. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 9, 186–215. doi:10.1257/app.20160079

Huang, D., and Ying, Z. (2018). A Review on Precise Poverty Alleviation by Introducing Market Mechanism in a Context Dominated by Government, 2nd International Forum on Management, Education and Information Technology Application . Paris: Atlantis Press , 110–117. doi:10.2991/ifmeita-17.2018.19

Hubacek, K., Baiocchi, G., Feng, K., and Patwardhan, A. (2017). Poverty Eradication in a Carbon Constrained World. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00919-4

Hulme, D., and Shepherd, A. (2003). Conceptualizing Chronic Poverty. World Develop. 31, 403–423. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00222-X

Hussain, I., and Hanjra, M. A. (2004). Irrigation and Poverty Alleviation: Review of the Empirical Evidence. Irrig. Drain. 53, 1–15. doi:10.1002/ird.114

Jalan, J., and Ravallion, M. (2003). Estimating the Benefit Incidence of an Antipoverty Program by Propensity-Score Matching. J. Business Econ. Stat. 21, 19–30. doi:10.1198/073500102288618720

Jones, H. (2016). More Education, Better Jobs? A Critical Review of CCTs and Brazil's Bolsa Família Programme for Long-Term Poverty Reduction. Soc. Pol. Soc. 15, 465–478. doi:10.1017/S1474746416000087

Karlan, D., and Valdivia, M. (2011). Teaching Entrepreneurship: Impact of Business Training on Microfinance Clients and Institutions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 93, 510–527. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00074

Karlan, D., and Zinman, J. (2011). Microcredit in Theory and Practice: Using Randomized Credit Scoring for Impact Evaluation. Science 332, 1278–1284. doi:10.1126/science.1200138

Karnani, A. (2007). The Mirage of Marketing to the Bottom of the Pyramid: How the Private Sector Can Help Alleviate Poverty. Calif. Manage. Rev. 49, 90–111. doi:10.2307/41166407

Kleven, H. J., and Kopczuk, W. (2011). Transfer Program Complexity and the Take-Up of Social Benefits. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 3, 54–90. doi:10.1257/pol.3.1.54

Kwan, C., Walsh, C. A., and Donaldson, R. (2018). Old Age Poverty: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Cogent Soc. Sci. 4, 1478479–1478521. doi:10.1080/23311886.2018.1478479

Li, R., Shan, Y., Bi, J., Liu, M., Ma, Z., Wang, J., et al. (2021). Balance between Poverty Alleviation and Air Pollutant Reduction in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 16 (9), 094019. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac19db

Linnenluecke, M. K., Marrone, M., and Singh, A. K. (2020). Conducting Systematic Literature Reviews and Bibliometric Analyses. Aust. J. Manage. 45, 175–194. doi:10.1177/0312896219877678

Ludwig, J., Duncan, G. J., Gennetian, L. A., Katz, L. F., Kessler, R. C., Kling, J. R., et al. (2012). Neighborhood Effects on the Long-Term Well-Being of Low-Income Adults. Science 337, 1505–1510. doi:10.1126/science.1224648

Mahembe, E., Odhiambo, N. M., and Read, R. (2019). Foreign Aid and Poverty Reduction: A Review of International Literature. Cogent Soc. Sci. 5, 1625741. doi:10.1080/23311886.2019.1625741

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., and Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function. Science 341, 976–980. doi:10.1126/science.1238041

Maulu, S., Hasimuna, O. J., Mutale, B., Mphande, J., and Siankwilimba, E. (2021). Enhancing the Role of Rural Agricultural Extension Programs in Poverty Alleviation: A Review. Cogent Food Agric. 7, 1886663. doi:10.1080/23311932.2021.1886663

Mbuyisa, B., and Leonard, A. (2017). The Role of ICT Use in SMEs towards Poverty Reduction: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Int. Dev. 29, 159–197. doi:10.1002/jid.3258

McKernan, S.-M. (2002). The Impact of Microcredit Programs on Self-Employment Profits: Do Noncredit Program Aspects Matter. Rev. Econ. Stat. 84, 93–115. doi:10.1162/003465302317331946

Meinzen-Dick, R., Quisumbing, A., Doss, C., and Theis, S. (2019). Women's Land Rights as a Pathway to Poverty Reduction: Framework and Review of Available Evidence. Agric. Syst. 172, 72–82. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2017.10.009

Meng, L. (2013). Evaluating China's Poverty Alleviation Program: a Regression Discontinuity Approach. J. Public Econ. 101, 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.02.004

Merediz-Solà, I., and Bariviera, A. F. (2019). A Bibliometric Analysis of Bitcoin Scientific Production. Res. Int. Business Finance 50, 294–305. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.06.008

Niehaus, P., Atanassova, A., Bertrand, M., and Mullainathan, S. (2013). Targeting with Agents. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol. 5, 206–238. doi:10.1257/pol.5.1.206

Pagiola, S., Arcenas, A., and Platais, G. (2005). Can Payments for Environmental Services Help Reduce Poverty? an Exploration of the Issues and the Evidence to Date from Latin America. World Develop. 33, 237–253. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.07.011

Park, A., Wang, S., and Wu, G. (2002). Regional Poverty Targeting in China. J. Public Econ. 86, 123–153. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00108-6

Pritchard, A. (1969). Oecologia. J. Doc. 50, 348–349. doi:10.2307/1934868

Sedlmayr, R., Shah, A., and Sulaiman, M. (2020). Cash-plus: Poverty Impacts of Alternative Transfer-Based Approaches. J. Develop. Econ. 144, 102418. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102418

Sen, A. (1999). “Development as freedom,” in The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change . Editors J. T. Roberts, A. B. Hite, and N. Chorev (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons ), 525.

Sims, K. R. E., and Alix-Garcia, J. M. (2017). Parks versus PES: Evaluating Direct and Incentive-Based Land Conservation in Mexico. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 86, 8–28. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2016.11.010

Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the Scientific Literature: A New Measure of the Relationship between Two Documents. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 24, 265–269. doi:10.1002/asi.4630240406

Stevenson, J. R., and Irz, X. (2009). Is Aquaculture Development an Effective Tool for Poverty Alleviation? A Review of Theory and Evidence. Cah. Agric. 18, 292–299. doi:10.1684/agr.2009.0286

Su, Y., Yu, Y., and Zhang, N. (2020). Carbon Emissions and Environmental Management Based on Big Data and Streaming Data: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 733, 138984. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138984

Van Eck, N. J., and Waltman, L. (2010). Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 84, 523–538. doi:10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Wilson, D. C., Velis, C., and Cheeseman, C. (2006). Role of Informal Sector Recycling in Waste Management in Developing Countries. Habitat Int. 30, 797–808. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2005.09.005

Zhang, J., Yu, Q., Zheng, F., Long, C., Lu, Z., and Duan, Z. (2016). Comparing Keywords Plus of WOS and Author Keywords: A Case Study of Patient Adherence Research. J. Assn Inf. Sci. Tec 67, 967–972. doi:10.1002/asi.23437

Zhang, X., Yu, Y., and Zhang, N. (2020). Sustainable Supply Chain Management under Big Data: a Bibliometric Analysis. Jeim 34, 427–445. doi:10.1108/JEIM-12-2019-0381

Zhou, D., Cai, K., and Zhong, S. (2021). A Statistical Measurement of Poverty Reduction Effectiveness: Using China as an Example. Soc. Indic. Res. 153, 39–64. doi:10.1007/s11205-020-02474-w

Keywords: poverty reduction, bibliometric analysis, VOSviewer, sustainable development goals, 21st century

Citation: Yu Y and Huang J (2021) Poverty Reduction of Sustainable Development Goals in the 21st Century: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Commun. 6:754181. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.754181

Received: 06 August 2021; Accepted: 01 October 2021; Published: 18 October 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Yu and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanni Yu, [email protected] ; Jinghong Huang, [email protected]

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

- PMC10265551

The Impact of Education and Culture on Poverty Reduction: Evidence from Panel Data of European Countries

1 Department of Economics, University of Foggia, 71121 Foggia, Italy

2 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences, University of Palermo, Viale Delle Scienze, 90128 Palermo, Italy

The 2030 Agenda has among its key objectives the poverty eradication through increasing the level of education. A good level of education and investment in culture of a country is in fact necessary to guarantee a sustainable economy, in which coexists satisfactory levels of quality of life and an equitable distribution of income. There is a lack of studies in particular on the relations between some significant dimensions, such as education, culture and poverty, considering time lags for the measurement of impacts. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by focusing on the relationship between education, culture and poverty based on a panel of data from 34 European countries, over a 5-year period, 2015–2019. For this purpose, after applying principal component analysis to avoid multicollinearity problems, the authors applied three different approaches: pooled-ordinary least squares model, fixed effect model and random effect model. Fixed-effects estimator was selected as the optimal and most appropriate model. The results highlight that increasing education and culture levels in these countries reduce poverty. This opens space to new research paths and policy strategies that can start from this connection to implement concrete actions aimed at widening and improving educational and cultural offer.

Introduction

Poverty eradication has been the key objective for spans in many countries since that has been recognized as the greatest hostile issues ‘jeopardising balanced society socio-economic development’ (Balvociute, 2020 ). Poverty can be considered one of the core features of unsustainable socio-economic development and as a persistent phenomenon that can have upsetting effect on peoples’ lives (Bossert et al., 2022 ). For this reason, the extreme poverty removal, as well as the fight against inequalities and injustices, have been placed at the center, with climate change, of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. The nature of poverty is multidimensional and inequalities within and among countries is an obstinate origin for concern (Fund, 2015 ; Alvaredo et al., 2017 ; Alkire & Seth, 2015 ; Kwadzo, 2015 ). For its interpretation and measurement, the literature has added to the monetary approach of material deprivation, the social and subjective dimension of the human being (Bellani & D’Ambrosio, 2014 ; Maggino, 2015 ). As stated by Kwadzo ( 2015 ), it is possible to define three poverty measurements: monetary poverty, social exclusion, and capability poverty. Similarly, there are a lot of indicators measuring well-being and quality of life: Index of Happiness, Human Poverty Index and Human Development Index (Senasu et al., 2019 ; Spada et al., 2020 ; UNDP, 1990 ; Veenhoven, 2012 ; Watkins, 2007 ). All these indicators focus and start from education. For example, the Human Poverty Index (HPI) was introduced by the United Nations to complement the Human Development Index (HDI) and used, for the first time, in the 1997 Human Development Report. In 2010, it was replaced by the Multidimensional Poverty Index. The HPI focuses on the deprivation of three essential parameters of human life, already taken into account by the Human Development Index: life expectancy, education and standard of living (Alkire et al., 2015 ; UNDP, 1990 ).

Previous studies shown that education indicators have a large impact on a country’s poverty (Bakhtiari & Meisami, 2010 ; UNDP, 1990 ; Watkins, 2007 ) and that investing in health and education is a way to reduce income inequality and poverty. In addition, studies highlight that increasing equality and the quality of education is essential to combat economic and gender inequality within society (Walker et al., 2019 ). However, few studies provide empirical evidence on how education impacts on income inequality (Liu et al., 2021 ; Santos, 2011 ; Walker et al., 2019 ) and most of these studies analyses the poverty phenomenon neglecting the combined effect of various variables. Different dimensions of poverty have also empirically demonstrated a high degree of correlation (Kwadzo, 2015 ). In addition, the literature review analysis highlighted a gap in quantitative studies, especially on the paths between some relevant dimensions, such as education, culture and poverty, considering time lags for the measurement of impacts. In light of this, the main objectives of this study are: (i) To identify over the five-year period considered (2015–2019), with what delay and with what magnitude and sign, the poverty is influenced by some indicators representative of the educational and cultural dimension; and (ii) Consequently, better calibrate education policies in European countries, in order to achieve a reduction in the poverty rate in the short term, in compliance with the objectives of the 2030 Agenda.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. A literature review regarding the relation between poverty, education and inequalities is presented in Sect. 2 . The Sect. 3 enlightens research gaps linked to the aims of this study and hypothesis to corroborate. Section 4 defines data and summarizes the methodological approach used to reach the work’s aims. Results are presented and discussed in Sect. 5 . Finally, the last section sets out our main conclusions by highlighting limitations of the study and future directions.

Theoretical Framework

The core role of education.

Over the last decades it is possible to individuate in the EU-28 a quickly growing portion of the population having income below 60% of the median disposable income. In addition, there is a share of the population has been becoming more impoverished (Balvociute, 2020 ; EUROSTAT Statistic Explained, 2019 ). In same way, it is possible to speak about “poverty trap”, a mechanisms whereby countries are poor and persist poor: existing poverty appears a straight cause of poverty in the future (Knight et al., 2009 ; Kraay & McKenzie, 2014 ). Aspects such as accommodation, education, medical and material services are considered essential. In particular, an increasing number of empirical studies have supported the positive effects of education on the creation of wealth by individuals and on promoting economic effective and fair development (UNESCO & Global Education Monitoring Report, 2017 ; Walker et al., 2019 ; Xu, 2016 ; Zhang, 2020 ). A research note by European Commission ( 2015 ) shows that individuals with primary education remain the most vulnerable in all EU countries (with a risk of poverty ranging from 13%—Netherlands—to 56% Romania). Even the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) endorsed by the World Bank and ‘Education for All’ program (UNESCO, 2007 ) emphases the significant role of education (Awan et al., 2011 ). A diverse balance can be possible and policy efforts to interrupt the poverty trap might have long-term effects. In this framework, the model proposed by Santos ( 2011 ) shows that a policy oriented towards aligning the quality of education would reduce initial inequalities. In light of this, Shi & Qamruzzaman, ( 2022 ) in a recent work, study, by means of numerous econometrical methods, the tie between investments in education, financial inclusion, and poverty decrease for the period 1995–2018 in 68 nations, underlining the role of education-backed poverty mitigation public policies that need to be more targeted. Several studies demonstrate that level of poverty and education are strictly related. For instance, Bossert et al. ( 2022 ) by focusing on Atkinson-Kolm-Sen index, that measures the percentage income gap of the poor that can be attributed to inequality among the poor (Sen, 1973 , 1976 ), emphasized the close relation between poverty and inequality. Consistent with previous studies, Lenzi and Perruca ( 2022 ) demonstrate that tertiary educated people report higher ranks of life satisfaction. This link is even more marked in rural territories where education is recognised as an important tool for reducing poverty as it allows the acquisition of skills and productive knowledges which increase people’s productivity and their earnings (Tilak, 2002 ). A recent report of the United Nations ( 2021 ) underlines how the reduced access to educational and health services in rural areas becomes a barrier, determining the difficulty of people living in these areas to found employment in well-paid professions contributing to economic growth (Chmelewska and Zegar, 2018 ). However, as Liu and colleagues ( 2021 ) find, different levels of education have distinct effects on poverty in rural areas of China and that the latter is driven not only by factors within the region but also by the level of poverty in the surrounding regions. In addition, numerous empirical evidences reveal a link between educational level and income inequalities in several geopolitical contexts. Bakhtiari and Meisami ( 2010 ), in a work of over 10 years ago, makes use of a panel data set of 37 Islamic countries (eight time periods) to study income inequality along with a model of poverty, with the main variables as income level, health status, education and savings. Findings show that enhancing the health and education can reduce income inequality and poverty. Likewise, as Arafat and Khan ( 2022 ) underline the high level of education not only contributes to reducing the degree of poverty but improves the conditions of mental, social and emotional well-being compared to poorly educated families. After about 10 years, similar works by Wani and Dhami ( 2021 ) and Sabir and Aziz ( 2018 ) reach the same results investigating the SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) countries and 31 developing countries (by employing the System Generalized Method of Moments). In several cases, and especially in rural areas, poverty is linked to the lower level of household income compared to urban areas, resulting in differences in access to basic goods and services to meet personal needs (Chmelewska and Zegar, 2018 ). In this territories household income level is directly associated with food security, in fact, an increase in the level of income reduces food insecurity (Chegini et al., 2021 ). However, as evidenced by other authors (Kirkpatrick et al., 2020 ; Kusio & Fiore, 2022 ), access to education can help to overcome the migration of young people and geographical isolation and inaccessibility that characterize the poor areas (Kvedaraite et al., 2011 ). In turn, young, educated people affect entrepreneurial attitudes. Walker et al. ( 2019 ) in the recent report ‘ The Power of Education to Fight Inequality. How increasing educational equality and quality is crucial to fighting economic and gender inequality ’ show how education can be emancipating for individuals, and it can play the role of a ‘leveler and equalizer within society’. Education interrupts obstinate and rising inequality by promoting the development of more decent work, rising incomes for the poorest people: it can aid to endorse long-lasting, wide-ranging economic growth and social cohesion.

Gradstein and Justman ( 2002 ) underlined the role of education in shaping the social cohesion that can assure equality between individuals. Universal free education enhances people’s earning power, and can bring them out of poverty. Low levels of education hamper economic growth, which in turn slows down poverty reduction (UNESCO, 2017 ; Global Education Monitoring Report, 2019 ) estimates that each year of schooling raises earnings by around 10%;53 this figure is even higher for women. In Tanzania, having a secondary education reduces the chances of being poor as a working adult by almost 60%. According to a study by UNESCO and the Global Education Monitoring Report ( 2019 ), if all adults finished secondary school, 420 million individuals would be lifted out of poverty. The convergence of crises deriving first from COVID-19 then from climate change, and conflicts, are generating extra impacts above all on poverty, nutrition, health and education affecting all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Equilience, a synchratic neologism composed of Equity + Resilience, that is resilient systems in respect of equity as a balancing of the different interests of the parties. Recent research (Berbés-Blázquez et al., 2021 ; Williams et al., 2020 ; Contò and Fiore, 2020 ) highlight the crucial importance to promote the ‘marriage’ between equity and resilience.

Aims of Study and Hypothesis

This research is potentially the first study to investigate the relationship between educational, cultural factors and poverty in European countries.

The main research directions are as follows: (i) To assess the impact of education and culture (expressed by the following indicators: Cultural employment, Total educational expenditure, Graduates in tertiary education, Number of enterprises in the cultural sectors, Tertiary educational attainment ) upon poverty (indicated by Persons at risk of poverty or social ); (ii) To compare the strength and direction of the relationships between the variables considered in two temporal situations, i.e. with zero lag, and with lag equal to one year. The data cover the period 2015–2019 and were extracted from the Eurostat database.

In the light of the above discussion, of the literature review analysis, and of the theoretical frameworks examined this study explores the following research hypotheses with regard to the European context:

Education and culture have an inverse impact on the levels of poverty.

Our second hypothesis states:

The association between cultural, educational variables and poverty, in the short term is more intense if we consider a delay of one-year.

The dataset is a balanced panel of annual observations for 34 European countries and covers the period from 2015 to 2019. On the basis of literature findings, our analysis focused on the following dimensions: education, income inequality and poverty.

Thereby, the variables considered for our investigation are as follows:

- Poverty indicator: Persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion (% of population, thousand persons; hereinafter labelled with PRP);

- Education and cultural indicators: Cultural employment (thousand persons); Total educational expenditure (million euros); Graduates in tertiary education (‰ of population;); Number of enterprises in the cultural sectors (number) Tertiary educational attainment (‰ of population). Respectively, hereinafter they will be labelled with CE, TEE, GTE, NEC and TEA.

The indicators have been extracted from the Eurostat database. The summary statistics are reported in Table Table1. 1 . In the selected time period, Iceland is the country that shows the lowest values with respect PRP (12.08%). Instead, the country showing the worst performance is Romania (PRP = 41.60%). With regard to the education indicators, Germany holds the highest values for both CE (81,661.48 thousand persons) and TEE (30.588.86 million euros), highlighting great attention to education issues. Instead, in Eastern Europe (Montenegro, Romania, and Hungary) the indicators pertaining to the education area take on more penalized values. Italy is the country that boasts the largest number of enterprises in the cultural sector (NEC = 179,136.8), thanks also to the artistic beauties of which this country is rich. As far as the tertiary education level is concerned, the highest value of is held by Cyprus while the lowest by Romania (respectively TEA = 57.34 and TEA = 25.26). For subsequent processing, since the variables considered are both in the form of ratios and counts, all data were converted to natural logarithms.

Summary statistics for the Eurostat datasets, 2015–2019

| Country | PRP (% of people) | CE (thousand persons) | TEE (million euros) | GTE (‰ of people) | NEC (number) | TEA(‰ population) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Austria | 16.90 ± 0.27 | 174.32 ± 7.00 | 2,321.94 ± 349.82 | 22.44 ± 0.64 | 17,206,20 ± 756,05 | 40,14 ± 1,10 |

| Belgium | 21.26 ± 0.96 | 192.92 ± 12.66 | 13.88 ± 0.42 | 40,883,40 ± 1793,72 | 45,56 ± 1,88 | |

| Bulgaria | 37.70 ± 4.60 | 85.64 ± 1.68 | 406.27 ± 34.87 | 14.08 ± 0.38 | 10,622,60 ± 298,85 | 32,94 ± 0,82 |

| Croatia | 22.90 ± 1.44 | 54.90 ± 4.40 | 366.78 ± 50.34 | 18.16 ± 1.22 | 7277,80 ± 1290,32 | 33,44 ± 2,00 |

| Cyprus | 20.90 ± 1.95 | 13.18 ± 0.81 | 103.86 ± 4.97 | 10.10 ± 0.10 | 2419,60 ± 246,29 | 57,34 ± 2,15 |

| Czechia | 12.28 ± 0.45 | 198.36 ± 9.17 | 1,019.77 ± 161.00 | 16.72 ± 0.43 | 49,046,75 ± 4227,15 | 32,66 ± 1,06 |

| Denmark | 17.74 ± 0.51 | 123.68 ± 2.37 | 3,888.45 ± 130.80 | 22.62 ± 1.41 | 13,342,40 ± 600,75 | 45,2 ± 1,52 |

| Estonia | 23.46 ± 0.25 | 35.00 ± 1.50 | 242.30 ± 0 | 16.08 ± 0.46 | 3538,40 ± 329,77 | 40,04 ± 1,17 |

| Finland | 16.28 ± 0.59 | 122.56 ± 6.58 | 2,703.90 ± 139.27 | 23.80 ± 0.90 | 10,190,00 ± 99,94 | 40,7 ± 0,75 |

| France | 18.34 ± 0.48 | 917.60 ± 45.72 | 16,419.90 ± 0 | 26.08 ± 1.05 | 162,416,80 ± 7866,12 | 45,74 ± 1,76 |