CASE REPORT article

Case report: a case study significance of the reflective parenting for the child development.

- Department of Psychology, Plovdiv University “Paisii Hilendarski,” Plovdiv, Bulgaria

There are studies that connect the “child” in the past with the “parent” in the present through the prism of high levels of stress, guilt, anxiety. This raises the question of the experiences and internal work patterns formed in childhood and developed through parenthood at a later stage. The article (case study) presents the quality of parental capacity of a family raising a child with an autism spectrum. The abilities of parents (the emphasis is on the mother) to recognize and differentiate the mental states of their non-verbal child are discussed. An analysis of the parental representations for the child and the parent–child relationship is developed. The parameters of reflective parenting are measured. The methodology provides good opportunities for identifying deficits in two aspects: parenting and the functioning of the child itself. Without their establishment, therapy could not have a clear perspective. An integrative approach for psychological support of the child and his family is presented: psychological work with the child on the main areas of functioning, in parallel with the therapy conducted with the parents and the mother, as the main caregiver. The changes for the described period are indicated, which are related to the improvement of the parental capacity in the mother and the progress in the therapy in the child. A prognosis for ongoing therapy is given, as well as topics that have arisen in the process of diagnostic procedures.

Introduction

Attachment theory focuses on parent–child attachment and the effects this relationship has on the child's personality, interpersonal skills, and its capacity to form healthy relationships with adults. According to Bowlby (1969) , parents who are approachable and responsive allow their child to develop a sense of security, thus creating a sound basis for it to learn about the world. The capability of parents to verbalize the feelings and experiences of their child through conversations, reading stories or fairy tales, commenting on everyday situations develops the skills of mentalization in the child ( Ханчева, 2019 ).

In mature age, the ability to mentalize depends on the emotional load of the interpersonal situation. Optimal mentalization implies integration of cognitive knowledge with insights into the emotional world, which allows a man to see more clearly and achieve “emotional knowledge” ( Allen and Fonagy, 2006 ).

The processes of mentalization can be influenced by the “heritage” that is passed down through generations. In their life experience, individuals operate and make their choices not being aware that they repeat the history of their ancestors. In part, these complex relationships can be seen, felt, or anticipated. They are experienced as elusive, insensible, unnamed, or secret, and may leave traumatic traces ( Kellermann, 2001 ).

Tisseron (2011) , associates the process of transmission of traumatic experience from generation to generation with three types of symbolization of experience: affective/sensory/motor, figurative, and verbal. If the event is symbolized in just one of the modalities, the results are associated with violation of mental life. The result becomes a distortion of the parent–child relationships, of their functioning.

The main psychopathological mechanisms that are activated in the transmission of mental content between individuals from generation to generation are associated with the identification and the projective identity. In this case of transmission through generations, insensible patterns, conflicts, scenarios and roles, ideals, and perceptions of the object are identified.

Children of severely traumatic parents reproduce scenes that their parents went through, trying to understand their pain, and at the same time establish a connection with them. They maintain family ties through the integration of parenting experiences. In the meantime, the parent seeks to teach his/her child survival strategies in situations of future persecution, thus passing on his/her traumatic experience ( Baranowsky et al., 1998 ).

Wilgowicz (1999) , introduces the term “vampire complex” describing the impact of unexpressed and insensible experiences passed down from generation to generation. These traumatic experiences form the unconscious connection between the generations which interferes the natural course of the processes of separation and individuation. This complex is associated with experience of the child who in its development turns out to be “locked” in the prison of the parental traumatic experience being neither alive, nor dead, or in other words, unborn.

Krystal (1978) , describes the affective blindness of the principal caregiver as a characteristic of unprocessed traumatic experience ( Den Velde, 1998 ; Коростелева et al., 2017 ). It is associated with incomplete integration of the somatic Self into the Self.

Ammon (2000) , Hirsch (1994) describe in this context the “psychosomatic mother whose behavior is characterized by a lack of understanding of boundaries, intrusiveness, alexithymia, excessive concern for the physical functioning of her child, and at the same time “blind” to its psychic experiences.” Hope et al. (2019) report that maternal depression and complaints of psychological distress are associated with an increased risk of trauma and hospitalization for the age 3–11 years, with the highest being in the period 3–5 years. In another study, Baker et al. (2017) , reported an increased risk of burns, poisoning, and fractures in children aged 0–4 years raised by depressed mothers and/or such found in an anxious episode. Postpartum depression in the mother presupposes a high risk of burns, fractures, poisoning ( Nevriana et al., 2020 ).

The relationship between parental attitudes and child development is influenced by unconscious dynamics of the intrapsychic world of mother and father ( Tagareva, 2019 ). The ability of parents for reflexion and metacognitive monitoring allows them to recognize and regulate, to modulate, to turn into a symbolic (verbal) form the states they observe in their child. This gives an opportunity to comprehend and return in an understandable form to the child interpretation of its state based on understanding and empathy. If this capacity fails, the parent cannot give an adequate and meaningful interpretation of what is happening, because he/she himself/herself gets lost and confused in his/her own (threatening his/her integrity) experiences, and strong, meaningless, overwhelming emotions. The consequences of the lack of a “secure base” in the face of the caregiver may be associated with: low self-esteem, behavior of decompensation under stress, inability to develop and maintain friendships, trust and intimacy, pessimism toward themselves, family, society ( Matanova, 2015 ). The low level of reflexion on the trauma and the unaddressed traumatic experience as the mother's internal position, affect, and are a risk factor for, psychopathology later in the development.

In addition, parenting skills can be further tested when raising a child with Autism Spectrum Disorders in the family. Therapy for this nosology needs to include both psychological work with the child and support for the parents, especially for the mother, who in most cases limits her social roles and devotes herself only to parenthood. This is a serious argument to seek and optimize approaches in clinical practice to support the family environment in which children with neurodevelopmental disorders are raised.

Materials and Methods

This article is designed to present a case of a family with a child diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder, where the non-integrated individual traumatic experience in the mother (N.) affects the quality of her reflective parenting.

The analysis aims to display the status of individual functioning and skills for reflective parenting, as well as the effectiveness of psychological intervention to revive and optimize the relationship mother-child. Although the functioning of the mother is the focus of the present study, an analysis of parenting and the father has also been applied.

The study is a pilot one and marks the start of a project lasting over time.

Diagnostic tools have been used for:

- Assessment of the development and functioning of the child according to the methodology of Matanova et al. ( Matanova and Todorova, 2013 ). The methodology includes research of cognitive, linguistic, social, emotional, and motor sphere of functioning. Based on the identified deficits, it is possible to arrange a therapeutic plan for the child.

- Self-assessment scales for the study of the quality of the parental relationship and the formed internal work patterns (of affection and romantic relationship) of N. with her parents:

° The Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (PRFQ) by Luyten et al. (2017a , b ). The PRF assessment screening tool provides additional evidence of the complexity and multidimensionality of the PRF ( Luyten et al., 2009 ). It contains 18 items intended mainly for use in the study of PRF of parents with children aged 0–5 years. Three different aspects of PRF are evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale. Based on validated factor analysis, the authors identified three theoretically consistent and clinically significant factors, each of which included six items: (1) prementalization modes (PM), (2) certainty about mental states (CMS), (3) interest and curiosity about mental states (IC).

° Assessment of emotional bonding in the parent–child relationship (PBI) Gordon Parker ( Parker, 1979 ; Parker et al., 1979 ). The questionnaire consists of two scales which measure the variables “Care” and “Overcare” or “Control” by evaluating basic parenting styles through the prism of children's perception. It consists of two identical questionnaires of 25 items, one for each parent.

- Family sociogram to report its representation in the current family.

° Version of Eidemiller and Cheremisin ( Eidemiller et al., 2007 ). It is a drawing projective technique exploring several aspects: identify the position of the subject in the system of interpersonal relationships; determine the nature of communication in the family (direct or indirect). Dimensions: Number of family members who fall into the very circle; Size of the circles which mark the members; Disposition of circles (members) relative to each other (location); Distance between circles (members).

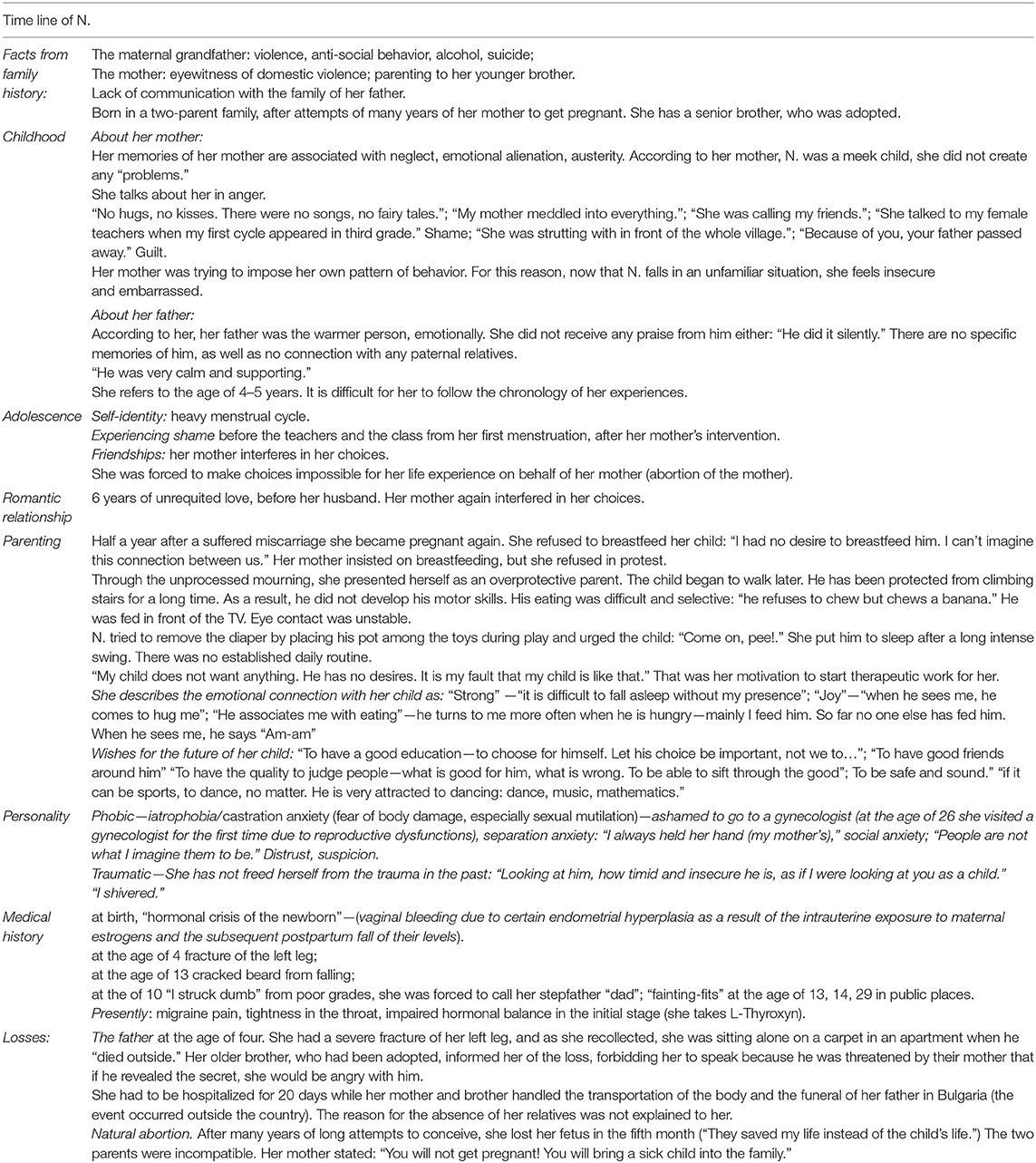

The case under study includes: demographic data of the family, anamnesis of the child (data obtained from psychological and medical research), prescribed therapy and progress, “The Time Line” ( Stanton, 1992 )—technique to retrieve significant events from the mother's history during the main stages of her development, located on the “axis of time,” data obtained from her psychological research—hers and her husband's.

N. is married with one child at 2.6 years, with suspected Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Demographic Data at First Visit

Mother (N.)—age: 36 years, education: higher, occupation: technologist.

Father (K.)—age: 39 years, education: higher, occupation: technologist.

Now, the mother is taking care of her child. Only her husband works. They live alone in a small town. The child is separated in his own room.

The child—bears his father's first name. According to parents: does not speak, does not eat independently—“He opens his mouth a little,” walks on tiptoe, does not play with other children, does not obey to commands, gets tired easily. The child attends the nursery until noon (on the recommendation of the director of the institution: “He does not eat”) and the Municipal Center for Personal Development. A social pedagogue works with him.

Data for Assessment of the Child's Development

The child was carried to full-term, born from a second, pathological pregnancy of the mother, laid in bed to avoid miscarriage in the first months. He had a protracted jaundice, which passed after a year and a half. He was not breastfed.

After a consultation with a psychologist, dysfunction was found in the following areas: Sensory: the child does not hold pelvic reservoirs, shows behavior of sensory hunger—needs intensely sensory stimuli; Motor development: with evidence of late walking, the child steps on toes; Cognitive processes: the child has not yet formed a body schema, he tends to suck the thumbs of his lower limbs; he still explores the objective world through oral modality; passivity regarding the choice of a toy if it is not in his filed vision; he does not play with his toys as intended; Emotional and social functioning: he is easily separated from the adult; the emotional expression is poorly differentiated and is played through the body by waving hands; lack of social interest; interaction is possible after prolonged sensory stimulation. Language development: he vocalizes; does not respond to his name.

During the study, the child is calm, passive. When coming into interaction, he retains his interest in the adult, but without any initiative to develop it further.

Electroencephalography was performed, in awake state and with open eyes, which displayed mixed main activity: of diffuse beta waves, and tetha waves 4.5–5 Hz, in the anterior areas: sporadically slower waves 3–4 Hz.

The child was prescribed a therapy with psychologist with live setting twice a week. The therapy with the parents was once a week. It started online prior to the beginning of the therapy with the child due to COVID-19 quarantine. Twenty sessions were held with the child, i.e., work continued for 5 weeks (with setting twice a week). The therapy includes psychological work with the child in the main areas of functioning, established as therapeutic lines of the conducted diagnostics. Ten sessions were held with the parents and the mother. Two of the sessions were held with the parents. The following were studied: their functioning through the different subsystems: marital, parental, child–parental; difficulties in raising a child with an autism spectrum. It was found that the family system organized its resource for therapy only for the child. They realized that their well-being was important for their child's development. The marital subsystem was in the background. A session was held with the father, in which his role as the Third Significant in the child's life was discussed. Seven sessions were held with the mother. In them was unfolded her personal story through early experience, child–parent relationship, main topics of growing up, intimacy, parent–child relationship with her child. The therapy is going on.

Progress of the Therapy With the Child

Decrease of sensory hunger, no tactile simulation is required to activate the child to study the objective reality; General motor skills: reduced toe walking, except in moments of agitation, he walks on a full step on a sensory path. The child jumps on tiptoe, climbing stairs is easier than getting down; Fine motor skills: improved grip (small toys, sticks, without clenching them in the fist); Cognition: recognizes himself in the mirror, experiments on dropping toys (primary circular reactions). Still uses oral inspection of some toys, beginnings of a play by designation (zone of proximal development). The active choice of toys is in progress, he explores freely the specialist room. Object constancy is formed, he seeks an object which he has played with. Lively, interesting. Emotional development: he expresses his joy by shouting and laughing, rejoices when imitated. Expresses anger. Attempts to manipulate by imitating crying. Language development: sporadically pronounces syllables, still does not respond to his name; Peculiarities: likes objects with small holes and pays lasting attention to them. He enters the oral-sadistic stage, bites toys, and gnaws some of them. Learned helplessness.

Data From Performed Psychological Studies

Child–parent relationships and internal work patterns for oneself and for the other (pbi).

The results of the self-assessment questionnaire on emotional closeness in the parent–child relationship with the mother indicate:

With reference to the relations with her mother: high results along the dimension “Overcare/Control” (24 points) and low results along the dimension “Care/Concern” (22 points). From these results it is evident that the mother in childhood is represented as emotionally cold, indifferent, and careless, and at the same time imposing control, intrusiveness, and excessive contact, infantilizing, and hindering the autonomy of N. as a child.

With reference to the relations with her father: high results along both dimensions “Overcare/Control” (32 points) and “Care/Concern” (25 points) what relates to a representation of the father's character as emotionally restrained in his behavior, but at the same time controlling, intrusive, and in attitude which is highly infantilizing and hindering the autonomy of N.

The model of adult attachment, proposed by Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) , related through the Parker quadrant, for the emotional closeness of a child–parent shows that N. has an active negative internal work pattern for herself along the dimension of “anxiety” and is associated with vulnerability to separation, rejection, or insufficient love. The work pattern of the other is negative, associated with fear of intimacy and social avoidance, i.e., along the dimension of “avoidance.” The attachment style corresponds to style B avoidant, subcategory cowardly avoidant.

In her husband, the internal work pattern is ambivalent. The mother's character from childhood is represented as emotionally restrained and controlling, while the father's is emotionally indifferent, however encouraging autonomy.

Family Sociogram

As a child, she presented inadequate, low self-esteem, and anxiety, an experience of emotional rejection and isolation. The father was the most significant figure, he was more emotionally close. This is also observed in her relations with the maternal grandmother. The size and thickening of the circle, which it is represented with, shows high levels of intrapersonal neuroticism. There are too many figures in the circle: apart from her four-member family, mother, father, brother, and she, it also includes her maternal grandmother and her uncle, the brother of her mother, as the division is in two camps on the basis of proximity-distance: her mother, uncle, and brother are found at one end of the circle, and the other end is occupied by her, her father and grandmother.

As an adult, prior to the birth of her child, her mother was also included in the circle which is associated with a tendency to unsatisfied needs from her.

After the birth of the child, the hierarchy is maintained and there is enough space between the members of the family now.

Through the life cycle of the family and the separation/individuation, this crisis must be lived through and integrated as a new experience. The stages show that in her childhood N. did not have a sound family model, the boundaries between the parent family and the maternal family are permeable. The above configuration could be interpreted as the presence of triangulations in the family system, and as well as intergenerational ones.

Within the romantic couple, in the period of the dyad, N. presents herself and her husband in a line, as the lower part of the test field includes the figure of her mother depicted by a smaller circle. This could be interpreted with the still insufficient density of the family boundaries. Establishing family boundaries (internal and external) is an important task at this stage of family life, as well as creating an optimal balance of proximity and distance; distribution of the roles in the family; establishing the hierarchy; negotiating family rules; coordination of future life plans, as well as joint understanding and acceptance.

It is also confirmed by the results of the interpretation of the family sociogram with the father as well. As a child he presented himself with inadequate, low self-assessment, he was hierarchically placed next to the mother's figure. Prior to the birth of the child, he presented unsatisfied needs from his parental family: no separation, the boundaries between own and native family are permeable. In the present one, the experience in the reality of what is happening is available. There is no differentiation between the relationships, and dissatisfaction with them is present. The child is put in the place of unsolved contradictions.

Reflective Parenting PRFQ

In all three dimensions, the results show values above the average as IC (“interest and curiosity about mental states”) is leading-−85.5%. It is associated with intrusive hypermentalization, i.e., she is difficult to regulate and interpret her own mental states when faced with her unregulated, difficult child. As a sequence, an inadequate reaction in response to his affective signals by the mother is provoked, as well as the presence of low levels distress tolerance. In hypermentalization as a process, there is a tendency to understand or explain mental dynamics based on complex logical constructs, sometimes abstract, notional, and without pragmatic benefit. Its extreme forms are characterized by autistic, groundless fantasizing.

The possibilities for reflective parenting with the father show increased trends in the dimensions of IC (“interest and curiosity about mental states”) and CMS, which is associated with enhanced hypermentalization, as in the mother, in the cases when she does not recognize the vague mental states of her child, however, here is also a desire to understand.

In her story N. unfolds a picture of the transmission of a traumatic experience of rejection/avoidance. The experience of emotional neglect has formed a negative notion of the Self. Through her anger, she repeats the model of her mother, not realizing that her own model is possible.

N. demonstrates a personal style in which fear and anxiety constitute a centrally organizing dimension. Reported phobias are associated with behaviors of shyness, restraint, aptitude for low self-esteem, indecisiveness, uselessness, and emotional inhibition. It is difficult for her to identify anxious thoughts, as well as to connect them with their triggers from reality, to master them and to allow a “decentralized” point of view on anxious situations, what might be the birth and upbringing of a child with arrested development. Avoidance behavior is associated with a remarkably high level of distress and a low level of long-term adaptation. ( Mikulincer and Shaver, 2012 ; Lingiardi and McWilliams, 2017 ). In cognitive theory, this feature (functioning through fear and avoidance) is considered an excellent example of an early maladaptive self-assessment scheme. The theory of mentalization conceptualizes this as an implicit (automatic) mentalizing deficit. In addition, there are difficulties in understanding the mind of others ( Dimaggio et al., 2007 ; Lampe and Malhi, 2018 ). Another major deficit of mentalization is their weak affective consciousness ( Steinmair et al., 2020 ).

Mother–Child Relationship

The relationship with her child is not objective. There is no construct to include references to the related problems outlined in her child. N. includes projective identification against guild as a protective mechanism related to her wishes for the child's future. The relationship with her child is idealized, in her aspiration and strong desire for love, characteristic of her personal structure. In this case, the child serves the mother's deficits and is not perceived objectively. The projection also supports this structure in her fear of rejection. She is parenting by satisfying the child's physical needs without giving the father the opportunity to be introduced to the child's mental life. And, although the projection is central to the father, in describing the relationship with the child, their shared experiences are related to “curiosity,” “play.” The mother's fear of loss, of rejection is the result of the unprocessed mourning. It could be also thought of splitting through the non-integrated image of the early figure of attachment. Presently, she is still demonized, and the father is idealized.

In the described period the child's study of objective reality is activated. recognizable in a mirror. Demonstrates the beginning of a game as intended, expresses joy in interaction, anger. Attempts to manipulate through imitation.

Parent Couple

The possibilities for reflective parenting in both parents are associated with increased hypermentalization, and the father has a desire to understand the mental states of the child.

Married Couple

N.'s internal working models are of a cowardly avoidant style (her husband's internal working model is ambivalent). The level of adherence to therapy is low, a high level of symptom reporting, and a low level of basic confidence. Those who have a negative BPM for themselves and for the other both want and fear of intimacy in the couple. This also presupposes the future occurrence of crisis in N. married couple.

Family System

In families such as the above described, raising a child who is unable to express their own needs in a conventional way, unresolved conflicts from the beginning of their life cycle, can escalate and lead to marital dissatisfaction and dysfunction throughout the family system.

The presented integrative model of psychological support in a family raising a child with an autistic spectrum outlines a picture of improvement in two lines: in the child and in the child–parent relationship. In mother, the process of disidentification, the formation of the transmission of the object, the separation of what has been transmitted to it, allows the history of the past to be restored, therefore gives more freedom to the individual in the shaping of the individuality. Currently, the inserted traumas, even if not one's own, in the subjective experience of conflicts and fantasies, allow to integrate this experience and to turn it from destructive to structuring.

If the traumatic event is mentally processed, symbolized, and inserted in the individual memory as an experience, it receives the status of the past, of memory. It is passed on to generations not only as the content of traumatic experience but also the aptitude of its mental processing and coping with it, which affects the individual development of the child.

N.'s feedback on the therapy so far: “He showed it to us, but I, my fault, my mistake, was that I did not see it.” She finds that now is more observant.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this article are not readily available because personal data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Zlatomira Kostova.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author's Note

The article presents a research perspective on the possibilities of parental capacity, through the integration of different approaches to understanding human suffering in clinical psychology.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Коростелева, И. С., Ульник, Х., Кудрявцева, A. В., and Pатнер, Е. A. (2017). Трансгенерационная передача: роль трансмиссионного объекта в формировании психосоматического симптома. Журнал практической Психологии Психоанализа . Korosteleva, I. S., Ulnik, H., Kudryavtseva, A. V., and Patner, E. A. (2017). Transgenerative transmission: the role of transmission object in the formation of a psychosomatic symptom. J. Pract. Psychol. Psychoanal .

Google Scholar

Ханчева, К. (2019). Mентализация и ранни етапи на социо-емоционално развитие. Университетско издателство. Климент Охридски . Hancheva, C. (2019). Mentalization and Early Stages of Socio-Emotional Development . University press: Kliment Ohridski.

Allen, J. G., and Fonagy, P., (eds.). (2006). The Handbook of Mentalization-Based Treatment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. doi: 10.1002/9780470712986

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ammon, G. (2000). Psychosomatic Therapy . Saint Petersburg, FL: Speech.

Baker, R., Kendrick, D., Tata, L. J., and Orton, E. (2017). Association between maternal depression and anxiety episodes and rates of childhood injuries: a cohort study from England. Inj. Prev . 23, 396–402. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042294

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baranowsky, A. B., Young, M., Johnson-Douglas, S., Williams-Keeler, L., and McCarrey, M. (1998). PTSD transmission: a review of secondary traumatization in Holocaust survivor families. Canad. Psychol . 39:247–256. doi: 10.1037/h0086816

Bartholomew, K., and Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol . 61, 226–244. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss . v. 3, Vol. 1. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Den Velde, W. O. (1998). “Children of Dutch war sailors and civilian resistance veterans,” in International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma , ed Y. Danieli (Boston, MA: Springer), 147–161. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-5567-1_10

Dimaggio, G., Semerari, A., Carcione, A., Nicolo, G., and Procacci, M. (2007). Psychotherapy of Personality Disorders: Metacognition, States of Mind and Interpersonal Cycles . London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203939536

Eidemiller, E. G., Alexandrova, N. V., and Justickis, V. (2007). Family Psychotherapy . Saint Petersburg, FL: Speech.

Hirsch, M. (1994). The body as a transitional object. Psychother. Psychosom . 62, 78–81. doi: 10.1159/000288907

Hope, S., Pearce, A., Chittleborough, C., Deighton, J., Maika, A., Micali, N., et al. (2019). Temporal effects of maternal psychological distress on child mental health problems at ages 3, 5, 7 and 11: analysis from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Psychol. Med . 49, 664–674. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001368

Kellermann, N. P. (2001). Transmission of Holocaust trauma-an integrative view. Psychiatry 64, 256–267. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.3.256.18464

Krystal, H. (1978). Trauma and affects. Psychoanal. Study Child . 33:81–116. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1978.11822973

Lampe, L., and Malhi, G. S. (2018). Avoidant personality disorder: current insights. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag . 11, 55–66. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S121073

Lingiardi, V., and McWilliams, N., (eds.). (2017). Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual: PDM-2 . New York, NY: Guilford Publications. doi: 10.4324/9780429447129-11

Luyten, P., Fonagy, P., Mayes, L., and Van Houdenhove, B. (2009). Mentalization as a multidimensional concept. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Luyten, P., Mayes, L. C., Nijssens, L., and Fonagy, P. (2017a). The parental reflective functioning questionnaire: development and preliminary validation. PLoS ONE 12:e0176218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176218

Luyten, P., Nijssens, L., Fonagy, P., and Mayes, L. C. (2017b). Parental reflective functioning: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Psychoanal. Study Child . 70, 174–199. doi: 10.1080/00797308.2016.1277901

Matanova, V. (2015). Attachment: There and Then, Here and Now . Varna: Steno.

Matanova, V., and Todorova, E. (2013). Guide for Applying a Methodology for Assessing the Educational Needs of Children and Students . Institute of Mental Health and Development.

Mikulincer, M., and Shaver, P. R. (2012). An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry 11, 11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.003

Nevriana, A., Pierce, M., Dalman, C., Wicks, S., Hasselberg, M., Hope, H., et al. (2020). Association between maternal and paternal mental illness and risk of injuries in children and adolescents: nationwide register based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ 369:m853. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m853

Parker, G. (1979). Parental characteristics in relation to depressive disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 134, 138–147. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.2.138

Parker, G., Tupling, H., and Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol . 52, 1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x

Stanton, M. D. (1992). The time line and the “Why now?” Question: a technique and rationale for therapy, training, organization consultations and research. J. Marit. Fam. Ther . 18, 331–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1992.tb00947.x

Steinmair, D., Richter, F., and Loeffler-Stastka, H. (2020). Relationship between mentalizing and working conditions in health care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health . 17:2420. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072420

Tagareva, K. (2019). “Psychological readiness for motherhood in pregnant women in different social environments,” in Proceedings of the Interdisciplinary Scientific Conference of the Faculty of Pedagogy at Plovdiv University: “Man and Global Society.” (Plovdiv).

Tisseron, S. (2011). Secrets de Famille Mode D'emploi. Paris: Marabout. doi: 10.3917/puf.tisse.2011.02

CrossRef Full Text

Wilgowicz, P. (1999). Listening psychoanalytically to the Shoah half a century on. Int. J. Psychoanal . 80, 429–438. doi: 10.1516/0020757991598765

Keywords: traumatic experiences, emotional bonding, autistic spectrum disorder, family system, reflective parenting

Citation: Kostova Z (2021) Case Report: A Case Study Significance of the Reflective Parenting for the Child Development. Front. Psychol. 12:724996. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724996

Received: 14 June 2021; Accepted: 26 July 2021; Published: 17 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Kostova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zlatomira Kostova, z_kostova@uni-plovdiv.bg

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9. Case Studies

Case studies #1-5 parent/guardian interactions, case study #1.

You receive this email from a parent:

“Dear Teacher,

I am very worried about my son starting kindergarten and getting on the bus. When we go to the store, he doesn’t stay with me and sometimes wanders off. We think he has a behavior disability, but no one has helped him. I heard the county has resources, but we haven’t found any yet. Could you walk him to the bus in the afternoons and make sure he gets on it and stays on?

Case Study #2

A parent comes to have lunch with their son, a typical practice at your elementary school. This student is on your IEP caseload and you know the parents well. At the conclusion of lunch, you walk by and say hello to the parent and conversationally ask “how are you?” The parent becomes visibly upset and begins to tell you that her son is physically acting out at home and hitting her. She begins crying. You haven’t seen this behavior from the child at school and you are shocked to hear this report from the parent.

Case Study #3

You co-teach 1st grade with a general education teacher who receives this email from a parent:

I am really worried about Jimmy’s reading. He seems really far behind his sisters when they were his age. He barely knows his sight words and forgets them all the time. I think there might be a problem. Can we schedule a conference?”

The co-teacher forwards you the email, asking if you can help her with a response. From your evaluations and observations, Jimmy is reading on grade level and demonstrates age typical academic achievement. You have not seen signs that Jimmy is behind his peers.

Case Study #4

You are a 9th grade Science teacher. You are sitting in a parent/ teacher conference with the guardian of a child in your class. You are discussing the student’s distractibility during independent work. The guardian of the student says, “You see a lot of kids, do you think my son has ADHD? Should he be on medication? Would he benefit from special education?”

Case Study #5

You are a 10th grade teacher. You send an email to a parent about their child, Josie, who qualified for special education services in 1st grade. Josie’s eligibility records indicate she was identified as having an intellectual disability. Late last week, Josie began pushing other students with her body while transitioning in the hallways. The behavior appears to be escalating. Shortly after you send your email, you receive this reply: “No thank you.” You are concerned that a potential language barrier exists, but when you consult the school records, they indicate that the parent has not asked for a translator for any meeting to date. Josie’s former teachers have expressed they had no difficulty communicating with the parent, even though the parent’s first and primary language is Spanish. Your colleagues believe this is an avoidance tactic so the parent doesn’t have to address Josie’s behaviors.

Case Studies #6-10 Collaboration with Professional Colleagues

Case study #6.

You are the special education teacher assigned to provide collaborative push-in support in a general education setting. You do not have common planning time with the general education teacher. Each day when you arrive in class, you learn about the topic of instruction at the same time as the students. When you asked the general education teacher for lesson plans to help you prepare in advance you were told, “I don’t have time to write lesson plans. I just know what I am doing every day.” You are concerned about your ability to provide accommodations and needed IEP support without prior knowledge of what is going to be taught each day.

Case Study #7

You are a general education teacher and were just informed that your class has been designated as the “inclusion class.” Approximately ⅓ of your students will have IEPs. You know that at least two of the students have significant behavioral concerns. A special education teacher or paraprofessional will be present during most of the academic instruction, but you are concerned about meeting the needs of all students and handling behaviors.

Case Study #8

One of your students frequently demonstrates disruptive and unsafe behaviors (e.g., cursing and throwing things) in the classroom. You have tried every behavioral strategy you can think of and they just don’t work to stop the behavior, so you resort to sending the student to the office. One day, as you are writing the disciplinary referral to send the student to the office, he comments, “That’s fine. When I’m hanging out in the office, Mrs. Angelo (the office manager) talks with me and gives me candy.”

Case Study #9

You are a special education teacher responsible for supervising two special education paraprofessionals. Some of your students require assistance with bathroom routines and occasionally have accidents which require adult support to clean up and change clothes. One of the paraprofessionals is unwilling to support students with these needs and is quite vocal about how the bathroom duties make her “feel sick.” The other paraprofessional shares with you in confidence that she feels it is unfair that she is always the one to handle these needs.

Case Study #10

You are a special education teacher working with a collaborative team of general education teachers and paraprofessionals. Your team has a student with significant medical needs and all team members are concerned about his safety. You asked your principal to provide training for all staff related to the students needs but were told that there is not enough funding for training.

High Leverage Practices in Special Education: Collaboration: https://highleveragepractices.org/four-areas-practice-k-12/collaboration

IRIS Module on collaboration for students with cognitive disabilities: https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/scd/cresource/q2/p05/

IRIS Module on Family Engagement: Collaborating with Families of Students with Disabilities: https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/fam/

IRIS Module on Serving Students with Visual Impairments: The Importance of Collaboration: https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/v03-focusplay/

Virginia Department of Education Inclusive Practices: https://www.doe.virginia.gov/programs-services/special-education/iep-instruction/inclusive-practices

A Case Study Guide to Special Education Copyright © by Jennifer Walker; Melissa C. Jenkins; and Danielle Smith. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Analyzing differences between parent- and self-report measures with a latent space approach

Dongyoung go, minjeong jeon, saebyul lee, ick hoon jin, hae-jeong park.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: [email protected] (HJP); [email protected] (IHJ)

Received 2021 Jun 30; Accepted 2022 May 19; Collection date 2022.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

We explore potential cross-informant discrepancies between child- and parent-report measures with an example of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Youth Self Report (YSR), parent- and self-report measures on children’s behavioral and emotional problems. We propose a new way of examining the parent- and child-report differences with an interaction map estimated using a Latent Space Item Response Model (LSIRM). The interaction map enables the investigation of the dependency between items, between respondents, and between items and respondents, which is not possible with the conventional approach. The LSIRM captures the differential positions of items and respondents in the latent spaces for CBCL and YSR and identifies the relationships between each respondent and item according to their dependent structures. The results suggest that the analysis of item response in the latent space using the LSIRM is beneficial in uncovering the differential structures embedded in the response data obtained from different perspectives in children and their parents. This study also argues that the differential hidden structures of children and parents’ responses should be taken together to evaluate children’s behavioral problems.

Introduction

How children think of themselves may not be consistent with how their parents think about themselves. Reportedly, parents’ evaluations of their children are often biased, sometimes superficial, and affected by their relationship with their children. Similarly, children often do not view themselves objectively [ 1 – 5 ].

Parent review and child review are frequently utilized in assessing children’s behavior or psychology [ 6 – 9 ]. Among many scales, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [ 7 ] and the Youth Self Report (YSR) are widely used scales to evaluate children’s behavior problems, which are based on parent reports (CBCL) and self (children) reports (YSR) on the same questionnaires. To evaluate children, the CBCL and YSR comprise items of eight domains (often called syndromes): Aggressive Behavior (AB), Anxious/Depressed (AD), Attention Problems (AP), Rule-Breaking Behavior (RBB), Somatic Complaints (SC), Social Problems (SP), Thought Problems (TP), and Withdrawn/Depressed (WD). These domains are often categorized into scores of internalizing (a combination of AD, WD, and SC) and externalizing problems (a combination of RBB and AB).

The large discrepancies between the CBCL and YSR data are a commonly discussed issue in the literature [ 2 , 6 , 10 – 12 ]. To study the discrepancies between parent- and self-report measures from the CBCL and YSR, two types of approaches are conventionally taken: the direct comparison and the model-based approaches. For the direct comparison, researchers typically utilized the measures that estimate the dependency between items of two different scales, using Pearson correlation or Cohen’s Kappa [ 2 , 10 , 12 , 13 ]. However, these direct comparison methods do not take into account the potential dependency among items that may differently exist in the two sets of measures on children. Consequently, comparison between CBCL and YSR based on the responses without considering intrinsic item inter-dependency is questionable. Three types of inter-dependent hidden structures may exist in the group item response data; between items and items, between respondents and respondents, and between items and respondents. These inter-dependent structures may differ between CBCL and YSR.

To consider item-item inter-dependency, factor analysis [ 7 , 14 , 15 ] has been applied to evaluate the CBCL and YSR relationship by modeling item response data with linear combinations of latent factors. Not being based on the item-response theory, those latent variables do not directly reflect the innate item or respondent characteristics embedded in the choice behaviors.

Several studies exist that defined the characteristics of items based on the item-response theory model to compare the characteristics between the two groups of respondents in the latent space [ 2 , 12 , 16 – 19 ]. Although the item-response theory model includes latent variables for items and respondents to explain group response data (see Eq 2 in the Method section), the direct item-item, respondent-respondent, or item-respondent relationships are not easily discernible. Furthermore, the previous item-response theory model may not directly evaluate each individual’s tendency toward items. Evaluating item response characteristics in each individual is critical in the practical application. Looking at individual-level discrepancies between a child-parent couple enables to generate personalized feedback on the child and parent. When exploring how a pair of child and parent views the child’s behavior differently, it would be intuitive if the items and each respondent (child and parent) have their positions (thus can be visualized) in the same latent space and if the distance between each item and respondent is explicitly defined.

In this study, to explore the multi-dimensional inter-dependent structures between items, respondents and item-respondent pairs differently embedded in the CBCL and YSR responses, we approached the problem in the latent space with a newly developed Latent Space Item Response Model (LSIRM) [ 20 ].

Latent spaces, or in other words, interaction maps, are commonly utilized to represent the relationship or dependencies between actors in various literature, such as social network analysis [ 21 , 22 ], recommendation [ 23 , 24 ]. The LSIRM assumes the inter-dependency can be modeled with ‘the distance’ in latent space in which both respondents and items have their ‘latent positions’ where the short distances in the latent space implies the strong dependency. For example, two items closer to each other in a latent space have stronger dependency than two items far apart. Two items with strong dependency indicate that respondents tend to show a similar response pattern to those items. Similarly, two respondents close to each other have strong dependencies, meaning that they tend to show a similar pattern of responding to test items (i.e., if one respondent responds positively to some items, the other respondent is likely to respond positively to those items). We will show that examining these dependency patterns in the two sets of measures can enlighten and shed new light on understanding the differences between CBCL and YSR. We will further present that the currently proposed method has an advantage in directly exploring respondent tendency toward items at the individual level, making it possible to examine different views in a child-parent pair on the child’s behaviors.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: We begin by describing the empirical data example that we will use in this study, followed by conventional analyses of the data. We then briefly describe the LSIRM and show how this model can capture the dependency in item response data. Next, we describe our strategy for comparing children and parent reports from the CBCL and YSR with LSIRM. In the Result and Discussion sections, we present and discuss our analysis results, compared with conventional analysis methods, and the differential views about the children’s behaviors from the children’s and their patients’ perspectives.

Materials and methods

Empirical data example.

We used a dataset from the Children Mind Institute’s healthy brain network MRI database ( https://childmind.org/data-sharing-initiatives/ ) [ 25 ]. Among 1,479 children, we selected 662 children (male: 397, female: 265) who had both the CBCL and YSR scores. Their age ranged from 10–18 years (mean: 13.8 years, standard deviation: 1.97 years). The CBCL and YSR tests consist of 120 items stating identical children’s behavioral problems in both tests. Among them, 118 items are multiple-choice questions such as “Acts too young for his/her age.” Respondents are asked to choose an option among the three response categories, “Not true,” “Somewhat or sometimes true,” “Very true or often true”, which are coded 0, 1, and 2, respectively. The other two free response items such as “Please write in any problems that were not listed above” is not considered here. The CBCL and YSR items are categorized into eight syndromes. We provided each item’s syndrome membership in the S1 Table . Several items do not belong to any particular syndromes. Those include Items 6, 7, 15, 24, 44, 49, 53, 55, 59, 60, 73, 74, 77, 80, 88, 92, 93, 98, 106, 107, 108, 109, and 110.

For data analysis, we dichotomized the original responses by combining the two positive categories of “Somewhat or sometimes true,” “Very true or often true,” and contrasting it with the only negative category of “Not true.” Such data dichotomization is not uncommon in the CBCL and YSR analysis, in part because of the frequently reported low reliability of the response categories [ 26 – 29 ]. After dichotomization, the mean proportion of positive responses was 0.43 with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.24 in the YSR, while in the CBCL, it was 0.27 with an SD of 0.17.

Analysis of CBCL and YSR differences using conventional methods

To compare with the current LSIRM analysis, we applied four analysis methods commonly used in the literature to compare the CBCL and YSR: three direct comparisons using pairwise measures, i.e., Pearson correlation, Kappa coefficients, and Jaccard similarity, and one model-based approach using item factor analysis. First, we evaluated the Pearson correlations between the CBCL and YSR at the syndrome level, using the syndrome-specific sum scores. The syndrome-level sum score is the sum of binary responses to the individual items, which can be treated as continuous data. Overall, the Pearson correlation was low, ranging from 0.23 (thought problem; TP) to 0.47 (rule-breaking problem; RBB). Table 1 shows the CBCL-YSR correlations for all syndromes. The size of the correlations was similar to the reports in the literature (e.g., [ 13 ]).

Table 1. Syndrome-level correlations and Kappa coefficients between CBCL and YSR.

a For the Kappa coefficients, we computed the syndrome mean of the item-level coefficients.

We then computed the Kappa coefficients to evaluate the degree of agreement between CBCL and YSR at the item level, following the procedure used in [ 12 ]. The Kappa coefficients were also low, ranging from -0.02 to 0.49, with a mean of 0.18. Table 1 lists the mean Kappa coefficients for all syndromes. This result is also in line with the reports in the literature (e.g., [ 12 ]).

Next, we applied conventional dyadic similarity analysis at the item level by using the Jaccard similarity measure [ 30 ]. Jaccard similarity is a dyadic similarity measure that compares the positive response counts of item pairs. Specifically, Jaccard similarity for binary vectors A and B is defined as J ( A , B ) = | A ∩ B |/| A ∪ B |. For the CBCL and YSR data, we computed the Jaccard similarity between P item vectors in the CBCL and YSR, respectively, where P are the number of items; we then subtracted the CBCL Jaccard similarity from the YSR similarity matrix. Table 2 lists the item pairs with the top 12 most significant differences in Jaccard similarity. Interestingly, none of the identified items have syndrome membership.

Table 2. Twelve item-item pairs are showing the most significant differences in Jaccard similarity between the CBCL and YSR.

[] indicates syndromes that the items belong to. [X] indicates that the item is not a member of any particular syndrome. For all pairs, the YSR showed high similarity (mean 0.963), while the CBCL showed low similarity (mean 0.014).

Lastly, we applied exploratory item factor analysis to the CBCL and YSR data, using the R package ‘mirt’ [ 31 ]. In the item factor model, the probability of answering positively to item i for respondent k is defined as follows:

where d i is item intercept, α i is item-specific latent factor, and θ k is respondent-specific latent factor [ 31 ].

In this experiment, we found the optimal number of factors was four, both for the CBCL and YSR data, based on G2 goodness-of-fit statistics and their p-values [ 32 ]. The factor structure comparison table and their fit statistics are given in the Supplementary S2 Table . The factor structure, however, was different between the two datasets. To summarize, for the first two factors, the CBCL and YSR show similar loading structures: the first significant factor covers most items of the AD syndrome (internalizing syndrome), and the second important factor covers most items of the RBB syndrome, an externalizing syndrome. However, the last two factor structures are quite different between the CBCL and YSR. The third factor is loaded on attention, social and thought problems (AP, SP, and TP) syndromes in the CBCL, while in the YSR, it is loaded on SC and WD syndromes. The fourth factor is loaded on the items with no syndrome membership in the YSR, while in the CBCL, this factor is loaded on most of the AB syndrome. These results are also consistent with the literature [ 6 , 14 ].

All four analyses point to that there are significant discrepancies between the CBCL and YSR data. We will later compare and discuss the proposed latent space approach’s results compared with these conventional methods. These conventional methods work as a reference for validating the proposed algorithm and providing a rationale for applying the current model-based approach.

Latent space item response model

The LSIRM [ 20 ] has been developed as an extension of the Rasch model to alleviate the conventional assumption of conditional independence (item responses are independent given a latent trait) and of homogeneity (respondents with the same trait level have equal success probability to an item). The LSIRM introduces latent positions, w i and z k for each item i and each respondent k in a d -dimensional latent space. The probability of positive response P ( y k i = 1 ) to an item i from a respondent k is then formulated as follows:

with item coefficients β i (item easiness), respondent coefficients θ k (latent trait), and the latent positions of respondent z k and item w i ( z k , w i ∈ R d ). The latent positions of respondent z k and item w i are determined by their distances, given the respondent and item coefficients. The resulting latent space approach provides an interaction map that represents the interactions of respondents and items, and helps derive insightful diagnostic information on items as well as respondents. We will use the words latent space and interaction map simultaneously. Though the dimension of the latent space or the distance measure can be arbitrarily chosen by researcher, we stick to R 2 and euclidean distance as Jeon et al. [ 20 ] remarked because of its strength in visualization. Eq 2 explains that when a respondent is further away from an item (i.e., larger distance and weaker dependency), the probability of giving a positive response to the item decreases. When a respondent becomes closer to an item (i.e., the shorter distance, the stronger dependency), the probability of giving a positive response increases. Note that Eq 2 is slightly different from Jeon et al. [ 20 ]’s formulation in that we fix the distance weight as one. This set-up enables us to match the two interaction maps from the CBCL and YSR data.

Transitivity

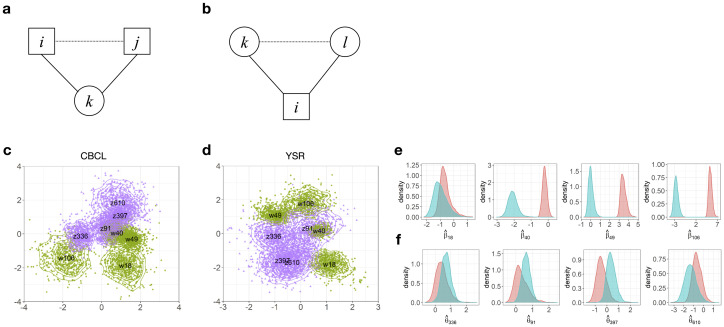

Note that although the model specifies distances between respondents and items in Eq 2 , the model also captures item-item and respondent-respondent distances. Fig 1(a) and 1(b) explains how it is possible; (a) if a k -th respondent responds positively to an i -th item and at the same time responds positive to a j -th item, the latent positions of w i and w j are likely to be close to each other; (b) if an i -th item is positively answered by respondents k and l , z k and z l are likely to be close to each other in interaction map. This is a property interaction map referred to as transitivity [ 33 , 34 ].

Fig 1. The concept of the distance, position and the latent space (interaction map).

(a) and (b) visualize the triangle inequality of the distance. (a) k is a respondent, and i and j are two items. If the positions of two items i and j are close to respondent k in the interaction map, the two items are fairly close to each other, by the triangle inequality. (b) i is an item, and k and l are two respondents. If two respondents k and l are close to the item i , the two respondents k and l are also close. (c) is an example of the posterior distributions of latent positions in the CBCL interaction map, and (d) is the posterior distributions in the YSR interaction map. For visualization, only four items (w18, w40, w49, w106) and four respondents (z91, z336, z397, z610) are displayed. Green dots and lines around the item positions indicate the posterior distributions of the item positions. Purple dots and lines around the person positions indicate the posterior distributions of the person positions. Note that the interaction maps differ for parents (CBCL) and children (YSR). Note also that both item and person positions are located in the same map. The short distance between two latent positions of items (respondents) in the interaction map implies a large dependency between two items (respondents). (e) and (f) present posterior distributions of selected item coefficients (e) and respondent coefficients (f). Blue indicates the CBCL, and red indicates the YSR distributions for each coefficient. All Bayesian inferences are made through these posterior samples; thereby flexible inference such as variance or overlapped portion with other distribution can be made.

The distance between two latent positions in latent space is the measure of dependency. The short distance between i th item latent position ( w i ) and j th item latent position ( w j ) means high dependency between two items. The respondent who responds positively to item i is likely to respond positively to j th item, vice-versa. The LSIRM models the item-item, respondent-respondent, and item-respondent dependency by projecting respondents and items to the continuous latent space. Therefore, the model-based comparison of two scales from different informants using the LSIRM allows us to evaluate pairwise dependencies between items, between respondents, and between items and respondents. Additionally, comparisons in aspects of higher-order dependencies, such as clustering patterns and relationships between clusters, are available using the LSIRM.

Fig 1(c) and 1(d) illustrate the interaction maps of the CBCL and YSR for the selected respondents and items for specific example. The figures display the posterior samples of latent positions for the selected items and respondents. For the item-item comparison, Items 40 and 49 (w40, w49) are relatively close in both interaction maps. This implies that Items 40 and 49 have a high dependency in both YSR and CBCL responses. On the other hand, Items 49 and 106 (w49, w106) are apart more in the CBCL interaction map than in the YSR interaction map, which implies a difference in dependency between the YSR and CBCL responses. Note that Item 40 states “Hears sounds or voices that aren’t there”, Item 49 states “Constipated, doesn’t move bowels”, and Item 106 is about “Vandalism”. Therefore, we can identify the differences of inherent dependency between pairs of items by comparing the interaction maps of the CBCL and YSR. For example, parents tended to make different reports on vandalism and constipation, while children responded similarly to those topics.

Regarding the respondent-respondent relationship, Fig 1(c) and 1(d) also show that some respondents are close to their locations, while others are further away. For example, Respondents 610 and 397 (z610, z397) are close to each other in both interaction maps, meaning that their response patterns were similar, given their latent trait levels and item difficulty. Similarly, for the respondent-item, we can also observe that Respondent 236 (z236) is closer to Item 106 (w106) in the CBCL space than in the YSR space. This indicates that for Respondent 236, the child’s probability of positively responding to “Vandalism” was lower than her parent’s likelihood of giving positive responses.

Of note, the current model assumes some hidden tendencies in the parents’ responses toward their children. Thus, other parent respondents’ responses are needed to decompose those hidden parent-to-children tendencies as a structure, even though the parent respondents are not directly related to the other children.

To estimate the LSIRM parameters, we used a Bayesian approach, following [ 20 ]. The priors of β i , θ k , z k and w i are set to an independent normal distribution with a mean of 0 and some variances. The hyper-prior for the variance parameter of θ k ( k = 1, ⋯, N ) is set to be a conjugate inverse Gamma distribution:

Metropolis-Hasting-within-Gibbs sampler [ 35 ] was used, which generates the posterior samples of β i , θ k , z k , and w i for k = 1, ‥, N and i = 1, ‥, P . Additional details of the estimation procedure are provided in the S1 Appendix . We set the number of iterations to 30,000 and take every 5-th sample after the first 5,000 steps as a burn-in period. Convergence was satisfactory, and the posterior distributions of the example item and person parameters are presented in Fig 1(e) and 1(f) .

Due to the invariance property of the distances (invariance to rotation, reflection, and translation), multiple solutions may be available for the latent positions that produce the same distance matrix. This issue is common for models that involve latent spaces [ 21 ]. To resolve such an identifiability issue, we applied Procrustes transformation [ 36 ] as a post-processing procedure, which is a standard method to resolve latent position identifiability in the literature [ 21 , 22 ]. For [ Z ] the class of positions equivalent to Z under rotation, reflection, translation, the Procrustean transformation is Z * = argmin TZ tr( Z 0 − TZ ) T ( Z 0 − TZ ), where Z 0 is a fixed set of positions and T ranges over the set of rotations, reflections, and translations. It is known that Z * is the closest element to Z 0 in terms of the sum of squared and is unique if Z 0 Z T is nonsingular [ 37 ]. Here the target Z 0 would be the positions draw that produces maximum a posteriori and the other posterior draw of latent positions are carried out Procrustes transformation to resolve the invariance to reflections, rotations and translations. All Bayesian inferences are made through the posterior samples obtained after the post-processing.

To deal with missingness in the datasets under investigation, we extended the estimation procedure of Jeon et al. [ 20 ] with Bayesian data augmentation [ 38 ]. Specifically, we imputed the missing data with the posterior samples, where an estimated item response for missing y ^ i k was generated using the estimated parameters of the previous step of the Gibbs sampling. The imputed response values were updated in every Gibbs sampling step. After assuming missing at random (MAR), this Bayesian data augmentation produces valid imputation results [ 39 ]. Of all item and respondent pairs, the missing proportion was 0.192% in YSR and 0.259% in the CBCL. We made MAR assumption because currently there is no established method for testing the nature of missingness, and MAR is often assumed in the CBCL and YSR analysis. Further, addressing potential non-ignorable missingness is not the primary purpose of the current study. We will look into the sensitivity of this assumption in future research.

Strategies for analyzing the CBCL and YSR differences with the LSIRM

We applied a series of further analyses for model-based examinations of the CBCL-YSR differences with the discussed latent space approach.

First, we fit the separate LSIRM to the CBCL and YSR datasets and estimated two sets of item coefficients β i , respondent coefficients θ k , and their latent space positions ( z k and w i ). We evaluated the goodness of fit of the model to each dataset.

Second, we examined the differences between the item coefficients β i estimated from the CBCL and YSR analysis. We also compared item positions w i in the CBCL and YSR interaction maps and checked whether the items with a large discrepancy between CBCL and YSR in item coefficients β i show distinct interaction patterns between them.

Third, we compared the CBCL and YSR in terms of item-pair distance or item-item dependency over the interaction map. For this, we first evaluated the distance distribution of the two items i and j (i.e., the posterior distributions of the distance || w i − w j ||) in the CBCL denoted as D i j C B C L ( x ) and YSR denoted as D i j Y S R ( x ) , respectively. This posterior distribution function D i j C B C L and D i j Y S R were obtained by calculating the Euclidean distance of each posterior sample of w i and w j in CBCL and YSR, obtained by fitting the LSIRM. This distribution represents the estimated dependency between item i and item j in terms of the distribution. We then assessed the significance of the differences of each item-pair dependency by evaluating the overlapped portion of their distance distribution. The overlapped portion was defined as

where min ( D i j C B C L ( x ) , D i j Y S R ( x ) ) indicates the overlapping areas of the two distributions. R ≤ .05 indicates that the two distributions are fairly different in a statistical sense [ 40 – 42 ]. An alternative approach, the calculation of the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between D i j C B C L ( x ) and D i j Y S R ( x ) , was also applied to capture the difference of item-pair dependency and its results were reported in the Supplementary S2 Appendix .

Fourth, item syndrome-level dependency is evaluated, with the syndrome positions identified with the centroid of the syndrome-specific items. Since the item syndrome is named with its semantic properties, it makes the axis of the interaction map more interpretable and comparable with intuition. To highlight the meaning of this axis, we used cosine similarity to measure the similarity of item syndrome level. The cosine similarity is measured based on the coordinates of the syndrome latent positions in the CBCL and YSR separately. The cosine similarity of two vectors a and b can be computed as

where ϕ is the angle between two vectors a and b , and || a || 2 > 0 and || b || 2 > 0 are their lengths. cos( ϕ ) ranges from -1 to 1, while -1 indicates that the two vectors point to the opposite directions, and 1 indicates the same direction. Cosine similarity of 0 means that the two vectors are orthogonal.

Fifth, we evaluated differences in the dependency between respondents with their syndrome levels. We presented that the distance between each respondent and syndrome in the interaction map could be used to find the vulnerable syndromes for each respondent. We then compared K-means clustering of all respondents based on the distance from all item syndromes and demonstrated how the interaction map approach could derive unique findings.

To evaluate the goodness of fit of the LSIRM to CBCL and YSR data, we assessed the proximity of the predicted item responses based on the estimated model to the original item responses, which is a commonly used strategy for evaluating the prediction accuracy of binary classification [ 43 – 45 ]. As evaluation criteria, we used sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy, which are reported as reliable measures [ 46 , 47 ].

The three indices are defined as Specifity = TN TN + FP , Sensitivity = TP TP + FN , Overall accuracy = TP + TN TP + TN + FP + FN , where TN is true negative, TP is true positive, FP is false positive, and FN is false negative. Table 3 shows the result. All values are higher than 0.70, except for the sensitivity for the CBCL. This suggests that overall, the LSIRM showed satisfactory fit to both the CBCL and YSR data in terms of prediction.

Table 3. Three goodness-of-fit measures of the LSIRM to the CBCL and YSR data.

Item coefficients and positions.

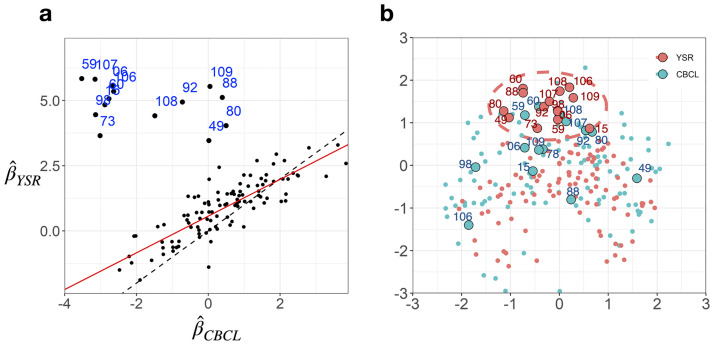

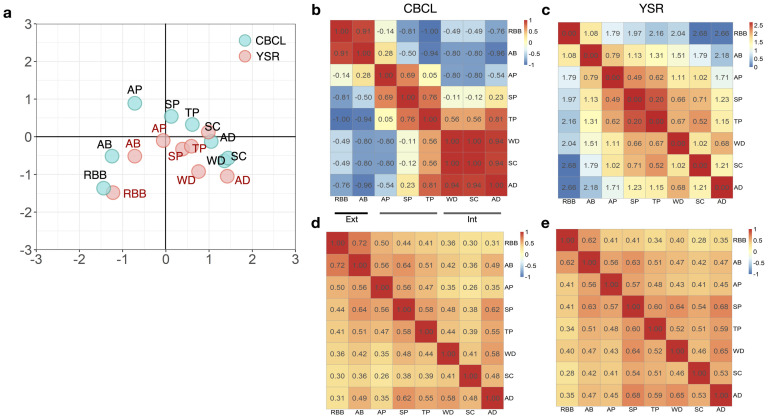

Fig 2(a) shows the relationship between the CBCL and YSR in the estimated item coefficients β ^ i . For most test items, the two sets of β ^ i are similar with the correlation of r = 0.83. However, a group of items does not follow this general pattern (marked in blue in the scatter plot). For those items, β ^ Y S R were higher than β ^ C B C L , meaning that the children than their parents more easily endorsed them. The specific contents of those items were listed in Table 4 . Those items appear to address behaviors related to sexual or physiological problems. That is, parents tended to believe that their children did not have sexual and physiological problems, even when the children themselves acknowledged such problems. Further analysis of these items with the interaction map can lead to more detailed interpretation.

Fig 2. Item-wise comparison between the CBCL and YSR.

(a) Comparison between the CBCL and YSR item coefficients β ^ i is displayed. The red line is the linear regression line between the CBCL and YSR estimates. The dotted line is y = x . Numbers indicate the outliers that deviate largely from the linear trend. For most test items, the two sets of β ^ i are similar with the correlation of r = 0.83. However, the indicated items do not follow this general pattern. (b) An integrated interaction map for the CBCL and YSR item positions is presented. Blue and red dots represent the item positions identified in the CBCL and YSR data, respectively. Larger dots with number labels are the outlier items identified in (a). Note that the distance between dots indicates the degree of association of the two items in the latent space. For the close items, if respondents respond positively to an item, they are more likely to respond positively to the other item.

Table 4. Items that differ between the CBCL and YSR in item-wise coefficients β ^ i or item easiness (a tendency of the positive answer).

The item easinesses of the YSR for these items are greater than the CBCL ( β ^ C B C L < β ^ Y S R ).

Fig 2(b) shows interaction maps with item latent positions w i obtained from CBCL and YSR analysis with respective LSIRMs. For visual comparisons, the two estimated interaction maps were matched and integrated using Procrustes matching. Blue dots indicate the positions of test items from the CBCL space, and red dots indicate the positions of test items in the YSR space. Respondents’ positions are not presented in Fig 2(b) to focus on item position comparisons.

The distributions of item positions were generally similar between CBCL and YSR spaces, but there were some notable exceptions. The aforementioned items with dissimilar item coefficients (items in Fig 2(a) and Table 4 ) were placed in different regions of the CBCL and YSR interaction maps. See items marked with numbers in Fig 2(b) . These items were closely located to each other in YSR (marked with a dotted red oval), which was not the case in the CBCL data.

Differences in item-item dependency

We evaluated item-pair distance differences between the CBCL and YSR data based on D i j C B C L and D i j Y S R values. For most item pairs, the difference was statistically significant ( p < 0.01) based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Table 5 lists the top 12 item pairs with the largest CBCL-YSR differences.

Table 5. Top 12 item pairs that show the largest differences between the CBCL and YSR in terms of D i j C B C L and D i j Y S R .

AP, SP and TP etc. within the brackets indicate the syndrome that each item belongs.

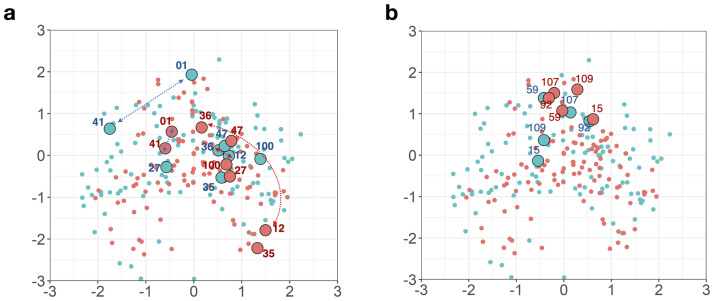

Fig 3(a) illustrates how different the item-pair distances were between the CBCL and YSR data for the top four pairs. Interestingly, these items did not match the items identified from the item coefficient ( β i ) difference analysis ( Table 4 ). In addition, they did not match the items identified with the Jaccard similarity analysis ( Table 2 and Fig 3(b) ). Fig 3(b) shows the Jaccard similarity between the CBCL and YSR data. The items identified in conventional direct comparison using Jaccard similarity were not coherently located with Fig 3(a) in the interaction map. This implies that our analysis of item-pair dependency does not offer the same kind of information as the analysis of the item coefficients and the conventional similarity analysis.

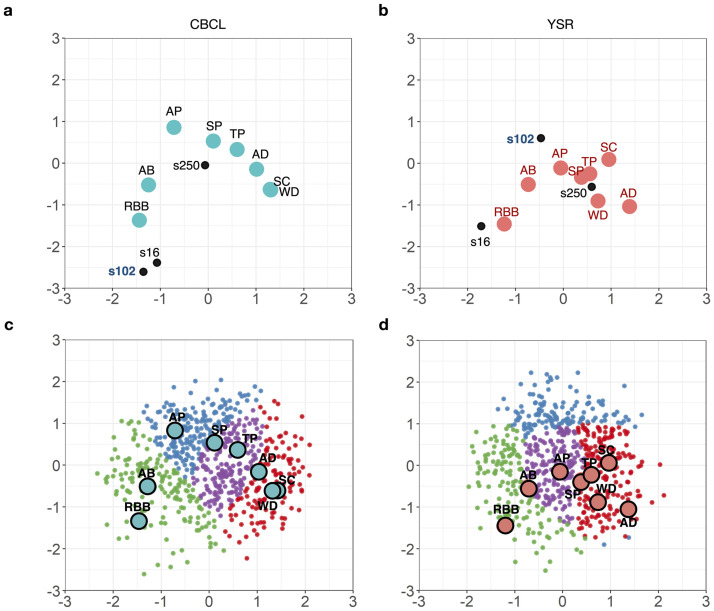

(a) Four item-item pairs with the largest differences in the distance (see Table 5 ). Double-side arrows are drawn to show the distances between two pairs (items 40 and 01; items 36 and 12) in the CBCL (blue) and YSR data (red). In addition to the position of each item, the distance between the two items’ positions should be noted. (b) Four item-item pairs with the largest difference in the Jaccard similarity between the CBCL and YSR data. This implies that our analysis of item-pair dependency does not offer the same kind of information as the analysis of the item coefficient and the conventional similarity analysis.

With item-pair differences, two groups of pairs can be distinguished in Table 5 . In one group, those pairs were believed to have similar behaviors from the children’s perspective, but not so much to the parents’ view (Pairs 1–9). In the other group, the item pairs showed the opposite patterns: while they were perceived similar behaviors to the parents’ eyes, they were believed to have different problems to the children (Pairs 10–12).

For example, to the children, “Act too young” and “Impulsive” (Pair 1) were similar behaviors, while it was not the case to the parents. The parents consider their children’s behaviors of “Complains of loneliness” and “Stores up too many things he/she doesn’t need” (Pair 11) are highly relevant, but children consider them irrelevant. Most of these items are the members of attention, social and thought problems (AP, SP, and TP) syndromes, indicating that those syndromes’ behaviors were likely to be evaluated and reported differently by different informants, i.e., parents and children in the current context.

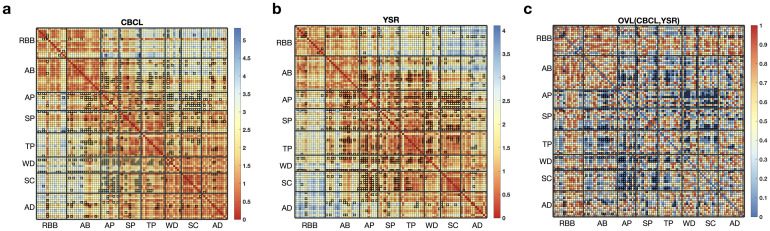

We assessed the overall differences in item-item dependency between the CBCL and YSR data by evaluating the overlap of the D i j C B C L and D i j Y S R distributions. Fig 4 summarizes above Fig 3 with respect to item-item dependency categorized by syndromes. The distance of each item pair (i.e., expectation of the probability distribution D ij ) is displayed in Fig 4(a) and 4(b) for the CBCL and YSR, respectively. The low value of distance means that their latent position was located closely and had a strong interaction. Fig 4(c) summarizes the overlapped portion for all pairs of items between CBCL and YSR. The item pairs with overlapped portion less than 0.05 are marked with bold edges. Of all the item pairs, about 9% of the pairs had overlapped portions of less than 0.05. The alternative approach using KL-divergence ( S2 Appendix ) suggests that pairs of items with a large discrepancy in KL-divergence between CBCL and YSR are positioned differently in their interaction maps.

Fig 4. Item-item distance heatmaps of the CBCL and YSR, and an overlapped portion heatmap between the CBCL and YSR.