Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Abortion — Why Abortion Should Be Legalized

Why Abortion Should Be Legalized

- Categories: Abortion Pro Choice (Abortion) Women's Health

About this sample

Words: 1331 |

Published: Jan 28, 2021

Words: 1331 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, why abortion should be legal.

- Gipson, J. D., Hirz, A. E., & Avila, J. L. (2011). Perceptions and practices of illegal abortion among urban young adults in the Philippines: a qualitative study. Studies in family planning, 42(4), 261-272. (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00289.x)

- Finer, L. B., & Hussain, R. (2013). Unintended pregnancy and unsafe abortion in the Philippines: context and consequences. (https://www.guttmacher.org/report/unintended-pregnancy-and-unsafe-abortion-philippines-context-and-consequences?ref=vidupdatez.com/image)

- Flavier, J. M., & Chen, C. H. (1980). Induced abortion in rural villages of Cavite, the Philippines: Knowledge, attitudes, and practice. Studies in family planning, 65-71. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/1965798)

- Gallen, M. (1979). Abortion choices in the Philippines. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-biosocial-science/article/abs/abortion-choices-in-the-philippines/853B8B71F95FEBDD0D88AB65E8364509 Journal of Biosocial Science, 11(3), 281-288.

- Holgersson, K. (2012). Is There Anybody Out There?: Illegal Abortion, Social Work, Advocacy and Interventions in the Philippines. (https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A574793&dswid=4931)

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1225 words

1 pages / 579 words

5 pages / 2322 words

1 pages / 448 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Abortion

Abortion is a really big deal that people have been arguing about for ages. It's all about life, morals, and personal rights. Some folks think it's a bad thing, and we're gonna talk about why. When someone gets an abortion, [...]

Satire is a potent tool that can be employed to address sensitive topics, and one such contentious issue is the abortion debate. Abortion, a divisive subject, has fueled passionate arguments for many years. The purpose of this [...]

Abortion is a highly controversial topic that has been the subject of heated debates for decades. One of the main theoretical frameworks through which abortion can be analyzed is functionalism. Functionalism is a sociological [...]

Abortion is a highly controversial and debated topic in today's society, and it is a matter of personal choice and moral beliefs. The debate over abortion has been ongoing for many years, and it has raised important ethical, [...]

Abortion is murder. 3000 babies are being killed every single day. In every 1000 women there are 12-13 abortions and there are 4.3 billion women in the world. I do believe it is a choice but a wrong choice because you are [...]

Humans should have the right to be able to abort their children. It is undeniable that humans should have abortion rights. That is just the bare minimum. These reasons will follow up for why.Primarily, Laws should not be kept on [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

As the Supreme Court considers Roe v. Wade, a look at how abortion became legal

Nina Totenberg

The future of abortion, always a contentious issue, is up at the Supreme Court on Dec. 1. Arguments are planned challenging Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey , the court's major decisions over the last half-century that guarantee a woman's right to an abortion nationwide. J. Scott Applewhite/AP hide caption

The future of abortion, always a contentious issue, is up at the Supreme Court on Dec. 1. Arguments are planned challenging Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey , the court's major decisions over the last half-century that guarantee a woman's right to an abortion nationwide.

For nearly a half-century, abortion has been a constitutional right in the United States. But this week, the U.S. Supreme Court hears arguments in a Mississippi case that directly challenges Roe v. Wade and subsequent decisions.

Those rulings consistently declared that a woman has a constitutional right to terminate a pregnancy in the first two trimesters of pregnancy when a fetus is unable to survive outside the womb. But with that abortion right now in doubt, it's worth looking back at its history.

Abortion did not become illegal in most states until the mid to late 1800s. But by the 1960s, abortion, like childbirth, had become a safe procedure when performed by a doctor, and women were entering the workforce in ever larger numbers.

Still, being pregnant out of wedlock was seen as scandalous, and women increasingly sought out abortions, even though they were illegal. What's more, to be pregnant often meant that women's educations were stunted, as were their chances for getting a good job. Because of these phenomena, illegal abortion began to skyrocket and became a public health problem. Estimates of numbers each year ranged from 200,000 to over a million, a range that was so wide precisely because illegal procedures often went undocumented.

At the time, young women could see the perils for themselves. Anyone who lived in a college dormitory back then might well have seen one or more women carried out of the dorm hemorrhaging from a botched illegal abortion.

George Frampton clerked for Justice Harry Blackmun the year that his boss authored Roe v. Wade , and he remembers that until Roe , "those abortions had to be obtained undercover if you had a sympathetic doctor" and you were "wealthy enough." But most abortions were illegal and mainly took place "in backrooms by abortion quacks" using "crude tools" and "no hygiene."

By the early to mid-1960s, Frampton notes, thousands of women in large cities were arriving at hospitals, bleeding and often maimed.

One woman, in an interview with NPR, recalled "the excruciatingly painful [illegal] procedure," describing it as "the equivalent of having a hot poker stuck up your uterus and scraping the walls." She remembered that the attendant had to "hold her down on the table."

The result, says Frampton, was that by the mid-1960s, a reform movement had begun, aimed at decriminalizing abortion and treating it more like other medical procedures. Driving the reform movement were doctors, who were concerned about the effect that illegal abortions were having on women's health. Soon, the American Law Institute — a highly respected group of lawyers, judges and scholars — published a model abortion reform law supported by major medical groups, including the American Medical Association.

Many states then began to loosen their abortion restrictions. Four states legalized abortion, and a dozen or so adopted some form of the model law, which permitted abortion in cases of rape, incest and fetal abnormality, as well as to save the life or health of the mother.

By the early 1970s, when nearly half the states had adopted reform laws, there was a small backlash. Still, as Frampton observes, "it wasn't a big political or ideological issue at all."

In fact, the justices in 1973 were mainly establishment conservatives. Six were Republican appointees, including the court's only Catholic. And five were generally conservative, as defined at the time, including four appointed by President Richard Nixon. Ultimately, the court voted 7-to-2 that abortion is a private matter to be decided by a woman during the first two trimesters of her pregnancy.

That framework has remained in place ever since, with the court repeatedly upholding that standard. In 1992, it reiterated the framework yet again, though it said that states could enact some limited restrictions — for example, a 24-hour waiting period — as long as the restrictions didn't impose an "undue burden" on a woman's right to abortion.

Frampton says that the court established the viability framework because of the medical consensus that a fetus could not survive outside the womb until the last trimester. He explains that "the justices thought that this was going to dispose of the constitutional issues about abortion forever."

Although many had thought that fetal viability might change substantially, that has not happened. But in the years that followed, the backlash to the court's abortion decisions grew louder and louder, until the Republican Party, which had earlier supported Roe , officially abandoned it in 1984.

Looking at the politicization of the Supreme Court nomination and confirmation process in recent years, one can't help but wonder whether Roe played a part in that polarization. What does Frampton think?

"I'm afraid," he concedes, "that analysis is absolutely spot on. I think they [the justices] saw it as a very important landmark constitutional decision but had no idea that it would become so politicized and so much a subject of turmoil."

Just why is abortion such a controversial issue in the United States but not in so many other countries where abortion is now legal? Florida State University law professor Mary Ziegler, author of Abortion and the Law in America , points out that in many countries, the abortion question has been resolved through democratic means — in some countries by national referendum, in others by parliamentary votes and, in some, by the courts. In most of those countries, however, abortions, with some exceptions, must be performed earlier, by week 12, 15 or 18.

But — and it is a big but — in most of those countries, unlike in the U.S., national health insurance guarantees easy access to abortions.

Lastly, Ziegler observes, "there are a lot of people in the United States who have a stake in our polarized politics. ... It's a way to raise money. It's a way to get people out to the polls."

And it's striking, she adds, how little our politics resemble what most people say they want. Public opinion polls consistently show that large majorities of Americans support the right to abortion in all or most cases. A poll conducted last May by the Pew Research Center found 6 in 10 Americans say that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. And a Washington Post -ABC poll conducted last month found that Americans by a roughly 2-to-1 margin say the Supreme Court should uphold its landmark Roe v. Wade decision.

But an NPR poll conducted in 2019 shows just how complex — and even contradictory — opinions are about abortion. The poll found that 77% of Americans support Roe . But that figure dropped to 34% in the second trimester. Other polls had significantly higher support for second trimester abortions. A Reuters poll pegged the figure at 47% in 2021. And an Associated Press poll found that 49% of poll respondents supported legal abortion for anyone who wants one "for any reason," while 50% believed that this should not be the case. And 86% said they would support abortion at any time during a pregnancy to protect the life or health of the woman.

All this would seem to suggest that there is overwhelming support for abortion rights earlier in pregnancy, but less support later in pregnancy, and overwhelming support for abortions at any time to protect the life or, importantly, the health of the mother. That, however, is not where the abortion debate is in the 25 or so states that have enacted very strict anti-abortion laws, including outright bans, in hopes that the Supreme Court will overturn Roe .

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- America’s Abortion Quandary

2. Social and moral considerations on abortion

Table of contents.

- 1. Americans’ views on whether, and in what circumstances, abortion should be legal

- Public views of what would change the number of abortions in the U.S.

- A majority of Americans say women should have more say in setting abortion policy in the U.S.

- How do certain arguments about abortion resonate with Americans?

- In their own words: How Americans feel about abortion

- 3. How the issue of abortion touches Americans personally

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

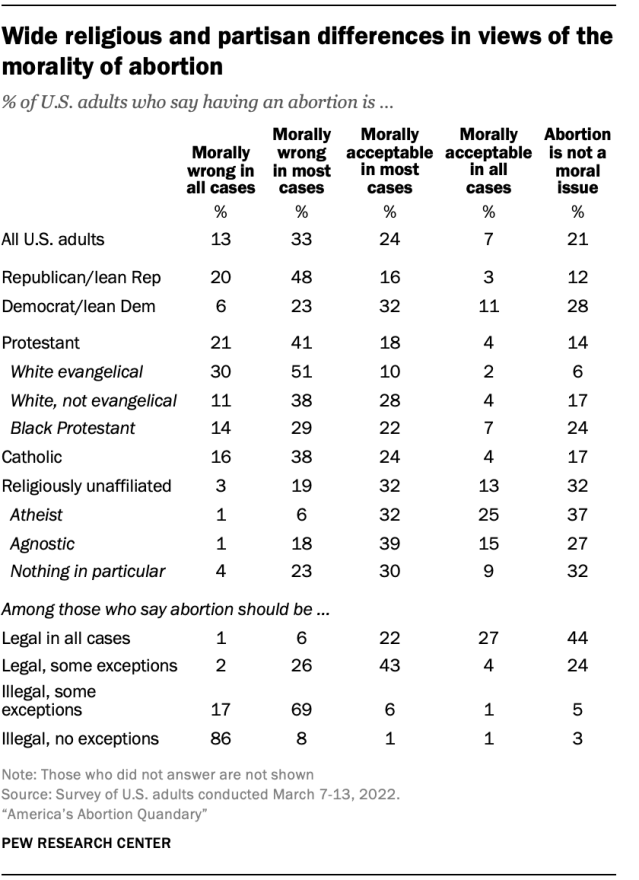

Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms: Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable most of the time. About an additional one-in-five do not consider abortion a moral issue.

There are wide differences on this question by political party and religious affiliation. Among Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party, most say that abortion is morally wrong either in most (48%) or all cases (20%). Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, meanwhile, only about three-in-ten (29%) hold a similar view. About four-in-ten Democrats say abortion is morally acceptable in most (32%) or all (11%) cases, while an additional 28% say abortion is not a moral issue.

White evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly say abortion is morally wrong in most (51%) or all cases (30%). A slim majority of Catholics (53%) also view abortion as morally wrong, but many also say it is morally acceptable in most (24%) or all cases (4%), or that it is not a moral issue (17%). And among religiously unaffiliated Americans, about three-quarters see abortion as morally acceptable (45%) or not a moral issue (32%).

There is strong alignment between people’s views of whether abortion is morally wrong and whether it should be illegal. For example, among U.S. adults who take the view that abortion should be illegal in all cases without exception, fully 86% also say abortion is always morally wrong. The prevailing view among adults who say abortion should be legal in all circumstances is that abortion is not a moral issue (44%), though notable shares of this group also say it is morally acceptable in all (27%) or most (22%) cases.

Most Americans who say abortion should be illegal with some exceptions take the view that abortion is morally wrong in most cases (69%). Those who say abortion should be legal with some exceptions are somewhat more conflicted, with 43% deeming abortion morally acceptable in most cases and 26% saying it is morally wrong in most cases; an additional 24% say it is not a moral issue.

The survey also asked respondents who said abortion is morally wrong in at least some cases whether there are situations where abortion should still be legal despite being morally wrong. Roughly half of U.S. adults (48%) say that there are, in fact, situations where abortion is morally wrong but should still be legal, while just 22% say that whenever abortion is morally wrong, it should also be illegal. An additional 28% either said abortion is morally acceptable in all cases or not a moral issue, and thus did not receive the follow-up question.

Across both political parties and all major Christian subgroups – including Republicans and White evangelicals – there are substantially more people who say that there are situations where abortion should still be legal despite being morally wrong than there are who say that abortion should always be illegal when it is morally wrong.

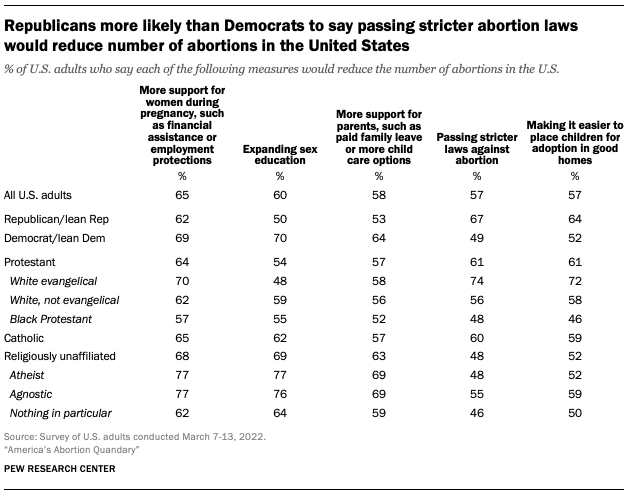

Asked about the impact a number of policy changes would have on the number of abortions in the U.S., nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) say “more support for women during pregnancy, such as financial assistance or employment protections” would reduce the number of abortions in the U.S. Six-in-ten say the same about expanding sex education and similar shares say more support for parents (58%), making it easier to place children for adoption in good homes (57%) and passing stricter abortion laws (57%) would have this effect.

While about three-quarters of White evangelical Protestants (74%) say passing stricter abortion laws would reduce the number of abortions in the U.S., about half of religiously unaffiliated Americans (48%) hold this view. Similarly, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say this (67% vs. 49%, respectively). By contrast, while about seven-in-ten unaffiliated adults (69%) say expanding sex education would reduce the number of abortions in the U.S., only about half of White evangelicals (48%) say this. Democrats also are substantially more likely than Republicans to hold this view (70% vs. 50%).

Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say support for parents – such as paid family leave or more child care options – would reduce the number of abortions in the country (64% vs. 53%, respectively), while Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say making adoption into good homes easier would reduce abortions (64% vs. 52%).

Majorities across both parties and other subgroups analyzed in this report say that more support for women during pregnancy would reduce the number of abortions in America.

More than half of U.S. adults (56%) say women should have more say than men when it comes to setting policies around abortion in this country – including 42% who say women should have “a lot” more say. About four-in-ten (39%) say men and women should have equal say in abortion policies, and 3% say men should have more say than women.

Six-in-ten women and about half of men (51%) say that women should have more say on this policy issue.

Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say women should have more say than men in setting abortion policy (70% vs. 41%). Similar shares of Protestants (48%) and Catholics (51%) say women should have more say than men on this issue, while the share of religiously unaffiliated Americans who say this is much higher (70%).

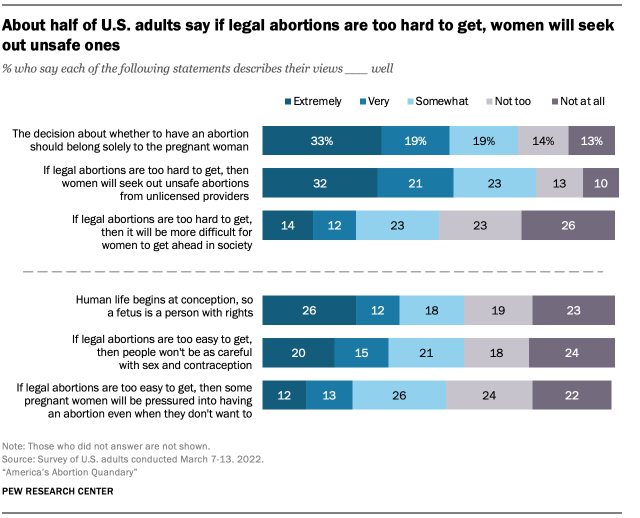

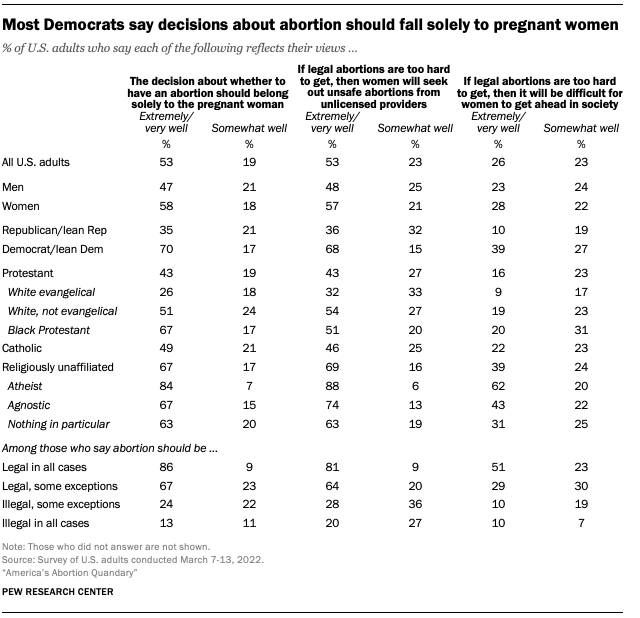

Seeking to gauge Americans’ reactions to several common arguments related to abortion, the survey presented respondents with six statements and asked them to rate how well each statement reflects their views on a five-point scale ranging from “extremely well” to “not at all well.”

The list included three statements sometimes cited by individuals wishing to protect a right to abortion: “The decision about whether to have an abortion should belong solely to the pregnant woman,” “If legal abortions are too hard to get, then women will seek out unsafe abortions from unlicensed providers,” and “If legal abortions are too hard to get, then it will be more difficult for women to get ahead in society.” The first two of these resonate with the greatest number of Americans, with about half (53%) saying each describes their views “extremely” or “very” well. In other words, among the statements presented in the survey, U.S. adults are most likely to say that women alone should decide whether to have an abortion, and that making abortion illegal will lead women into unsafe situations.

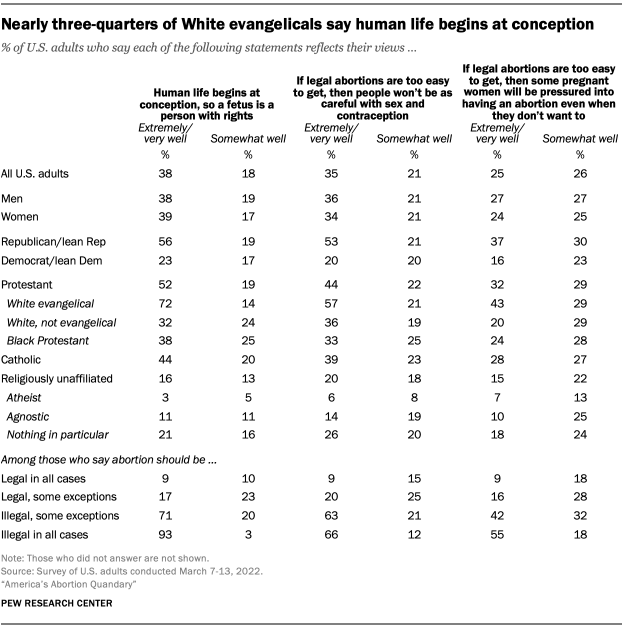

The three other statements are similar to arguments sometimes made by those who wish to restrict access to abortions: “Human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights,” “If legal abortions are too easy to get, then people won’t be as careful with sex and contraception,” and “If legal abortions are too easy to get, then some pregnant women will be pressured into having an abortion even when they don’t want to.”

Fewer than half of Americans say each of these statements describes their views extremely or very well. Nearly four-in-ten endorse the notion that “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights” (26% say this describes their views extremely well, 12% very well), while about a third say that “if legal abortions are too easy to get, then people won’t be as careful with sex and contraception” (20% extremely well, 15% very well).

When it comes to statements cited by proponents of abortion rights, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to identify with all three of these statements, as are religiously unaffiliated Americans compared with Catholics and Protestants. Women also are more likely than men to express these views – and especially more likely to say that decisions about abortion should fall solely to pregnant women and that restrictions on abortion will put women in unsafe situations. Younger adults under 30 are particularly likely to express the view that if legal abortions are too hard to get, then it will be difficult for women to get ahead in society.

In the case of the three statements sometimes cited by opponents of abortion, the patterns generally go in the opposite direction. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say each statement reflects their views “extremely” or “very” well, as are Protestants (especially White evangelical Protestants) and Catholics compared with the religiously unaffiliated. In addition, older Americans are more likely than young adults to say that human life begins at conception and that easy access to abortion encourages unsafe sex.

Gender differences on these questions, however, are muted. In fact, women are just as likely as men to say that human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights (39% and 38%, respectively).

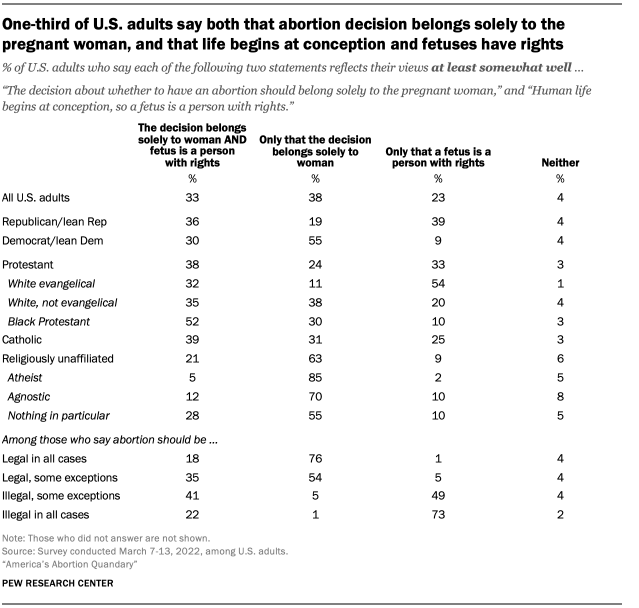

Analyzing certain statements together allows for an examination of the extent to which individuals can simultaneously hold two views that may seem to some as in conflict. For instance, overall, one-in-three U.S. adults say that both the statement “the decision about whether to have an abortion should belong solely to the pregnant woman” and the statement “human life begins at conception, so the fetus is a person with rights” reflect their own views at least somewhat well. This includes 12% of adults who say both statements reflect their views “extremely” or “very” well.

Republicans are slightly more likely than Democrats to say both statements reflect their own views at least somewhat well (36% vs. 30%), although Republicans are much more likely to say only the statement about the fetus being a person with rights reflects their views at least somewhat well (39% vs. 9%) and Democrats are much more likely to say only the statement about the decision to have an abortion belonging solely to the pregnant woman reflects their views at least somewhat well (55% vs. 19%).

Additionally, those who take the stance that abortion should be legal in all cases with no exceptions are overwhelmingly likely (76%) to say only the statement about the decision belonging solely to the pregnant woman reflects their views extremely, very or somewhat well, while a nearly identical share (73%) of those who say abortion should be illegal in all cases with no exceptions say only the statement about human life beginning at conception reflects their views at least somewhat well.

When asked to describe whether they had any other additional views or feelings about abortion, adults shared a range of strong or complex views about the topic. In many cases, Americans reiterated their strong support – or opposition to – abortion in the U.S. Others reflected on how difficult or nuanced the issue was, offering emotional responses or personal experiences to one of two open-ended questions asked on the survey.

One open-ended question asked respondents if they wanted to share any other views or feelings about abortion overall. The other open-ended question asked respondents about their feelings or views regarding abortion restrictions. The responses to both questions were similar.

Overall, about three-in-ten adults offered a response to either of the open-ended questions. There was little difference in the likelihood to respond by party, religion or gender, though people who say they have given a “lot” of thought to the issue were more likely to respond than people who have not.

Of those who did offer additional comments, about a third of respondents said something in support of legal abortion. By far the most common sentiment expressed was that the decision to have an abortion should be solely a personal decision, or a decision made jointly with a woman and her health care provider, with some saying simply that it “should be between a woman and her doctor.” Others made a more general point, such as one woman who said, “A woman’s body and health should not be subject to legislation.”

About one-in-five of the people who responded to the question expressed disapproval of abortion – the most common reason being a belief that a fetus is a person or that abortion is murder. As one woman said, “It is my belief that life begins at conception and as much as is humanly possible, we as a society need to support, protect and defend each one of those little lives.” Others in this group pointed to the fact that they felt abortion was too often used as a form of birth control. For example, one man said, “Abortions are too easy to obtain these days. It seems more women are using it as a way of birth control.”

About a quarter of respondents who opted to answer one of the open-ended questions said that their views about abortion were complex; many described having mixed feelings about the issue or otherwise expressed sympathy for both sides of the issue. One woman said, “I am personally opposed to abortion in most cases, but I think it would be detrimental to society to make it illegal. I was alive before the pill and before legal abortions. Many women died.” And one man said, “While I might feel abortion may be wrong in some cases, it is never my place as a man to tell a woman what to do with her body.”

The remaining responses were either not related to the topic or were difficult to interpret.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Christianity

- Evangelicalism

- Political Issues

- Politics & Policy

- Protestantism

- Religion & Abortion

- Religion & Politics

- Religion & Social Values

Majority of Americans continue to favor moving away from Electoral College

Americans see many federal agencies favorably, but republicans grow more critical of justice department, 9 facts about americans and marijuana, nearly three-quarters of americans say it would be ‘too risky’ to give presidents more power, biden nears 100-day mark with strong approval, positive rating for vaccine rollout, most popular, report materials.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- Volume 70 Masthead

- Volume 69 Masthead

- Volume 68 Masthead

- Volume 67 Masthead

- Volume 66 Masthead

- Volume 65 Masthead

- Volume 64 Masthead

- Volume 63 Masthead

- Volume 62 Masthead

- Volume 61 Masthead

- Volume 60 Masthead

- Volume 59 Masthead

- Volume 58 Masthead

- Volume 57 Masthead

- Volume 56 Masthead

- Volume 55 Masthead

- Volume 54 Masthead

- Volume 53 Masthead

- Volume 52 Masthead

- Volume 51 Masthead

- Volume 50 Masthead

- Sponsorship

- Subscriptions

- Print Archive

- Special Issue: Law Meets World Vol. 68

- Symposia Topics

Equality Arguments for Abortion Rights

Introduction.

Roe v. Wade grounds constitutional protections for women’s decision whether to end a pregnancy in the Due Process Clauses. 1 But in the four decades since Roe , the U.S. Supreme Court has come to recognize the abortion right as an equality right as well as a liberty right. In this Essay, we describe some distinctive features of equality arguments for abortion rights. We then show how, over time, the Court and individual Justices have begun to employ equality arguments in analyzing the constitutionality of abortion restrictions. These arguments first appear inside of substantive due process case law, and then as claims on the Equal Protection Clause. Finally, we explain why there may be independent political significance in grounding abortion rights in equality values.

Before proceeding, we offer two important caveats. First, in this brief Essay we discuss equality arguments that Supreme Court justices have recognized—not arguments that social movement activists made in the years before Roe , that academics made in their wake, or that ordinary Americans might have made then or might make now. Second, we address, separately, arguments based on the Due Process Clauses and the Equal Protection Clause. In most respects but one, 2 however, we emphasize that a constitutional interpreter’s attention to the social organization of reproduction could play a more important role in determining the permissibility of various abortion-restrictive regulations than the particular constitutional clause on which an argument is based.

I. Equality Arguments for Abortion Rights

Equality arguments are also concerned about the gendered impact of abortion restrictions. Sex equality arguments observe that abortion restrictions deprive women of control over the timing of motherhood and so predictably exacerbate the inequalities in educational, economic, and political life engendered by childbearing and childrearing. Sex equality arguments ask whether, in protecting unborn life, the state has taken steps to ameliorate the effects of compelled motherhood on women, or whether the state has proceeded with indifference to the impact of its actions on women. 5 Liberty arguments focus less on these gendered biases and burdens on women.

To be clear, equality arguments do not suppose that restrictions on abortion are only about women. Rather, equality arguments are premised on the view that restrictions on abortion may be about both women and the unborn— both and . Instead of assuming that restrictions on abortion are entirely benign or entirely invidious, equality analysis entertains the possibility that gender stereotypes may shape how the state pursues otherwise benign ends. The state may protect unborn life in ways it would not, but for stereotypical assumptions about women’s sexual or maternal roles.

For example, the state’s bona fide interest in protecting potential life does not suffice to explain the traditional form of criminal abortion statutes in America. Such statutes impose the entire burden of coerced childbirth on pregnant women and provide little or no material support for new mothers. In this way, abortion restrictions reflect views about how it is “natural” and appropriate for a woman to respond to a pregnancy. If abortion restrictions were not premised on these views, legislatures that sought to coerce childbirth in the name of protecting life would bend over backwards to provide material support for the women who are required to bear—too often alone—the awesome physical, emotional, and financial costs of pregnancy, childbirth, and childrearing. 6 Only by viewing pregnancy and motherhood as a part of the natural order can a legislature dismiss these costs as modest in size and private in nature. Nothing about a desire to protect fetal life compels or commends this state of affairs. When abortion restrictions reflect or enforce traditional sex-role stereotypes, equality arguments insist that such restrictions are suspect and may violate the U.S. Constitution.

II. Equality Arguments in Legal Doctrine

While Roe locates the abortion right in the Due Process Clauses, the Supreme Court has since come to conceive of it as an equality right as well as a liberty right. The Court’s case law now recognizes equality arguments for the abortion right based on the Due Process Clauses. Additionally, a growing number of justices have asserted equality arguments for the abortion right independently based on the Equal Protection Clause.

A. Equality Arguments for Abortion Rights and the Due Process Clauses

The Court has also invoked equality concerns to make sense of the Due Process Clauses in the area of abortion rights. The opinion of the Court in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey 11 is shaped to a substantial degree by equality values. At the very moment in Casey when the Court reaffirms constitutional protection for abortion rights, the Court explains that a pregnant woman’s “suffering is too intimate and personal for the State to insist, without more, upon its own vision of the woman’s role, however dominant that vision has been in the course of our history and our culture.” 12 This emphasis on the role autonomy of the pregnant woman reflects the influence of the equal protection sex discrimination cases, which prohibit the government from enforcing stereotypical roles on women. Likewise, in the stare decisis passages of Casey , the Court emphasizes, as a reason to reaffirm Roe , that “[t]he ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives.” 13 Here, as elsewhere in Casey , the Court is interpreting the Due Process Clause and drawing on equality values in order to make sense of the substance of the right.

The equality reasoning threading through Casey is not mere surplusage. Equality values help to identify the kinds of restrictions on abortion that are unconstitutional under Casey ’s undue burden test. As the joint opinion applies the test, abortion restrictions that deny women’s equality impose an undue burden on women’s fundamental right to decide whether to become a mother. Thus, the Casey Court upheld a twenty-four-hour waiting period, but struck down a spousal notification provision that was eerily reminiscent of the common law’s enforcement of a hierarchical relationship between husband and wife. Just as the law of coverture gave husbands absolute dominion over their wives, so “[a] State may not give to a man the kind of dominion over his wife that parents exercise over their children.” 14 An equality-informed understanding of Casey ’s undue burden test prohibits government from coercing, manipulating, misleading, or stereotyping pregnant women.

B. Equality Arguments for Abortion Rights and the Equal Protection Clause

In Carhart , Justice Ginsburg invoked equal protection cases—including Virginia —to counter woman-protective arguments for restricting access to abortion, which appear in the majority opinion. Woman-protective arguments are premised on certain judgments about women’s nature and decisional competence. 22 But the equal protection precedents that Justice Ginsburg cited are responsive both to woman-protective and to fetal-protective anti-abortion arguments. As Justice Blackmun’s Casey opinion illustrates, equality arguments are concerned that gender assumptions shape abortion restrictions, even when genuine concern about fetal life is present.

C. What About Geduldig ?

Equality arguments complement liberty arguments, and are likely to travel together. There is therefore little reason to reach the abstract question of whether, if Roe and Casey were overruled, courts applying existing equal protection doctrine would accord constitutional protection to decisions concerning abortion .

Proponents of equality arguments have long regarded the state’s regulation of pregnant women as suspect—as potentially involving problems of sex-role stereotyping. But in one of its early equal protection sex discrimination decisions, the Court reasoned about the regulation of pregnancy in ways not necessarily consistent with this view. In Geduldig , the Court upheld a California law that provided workers comprehensive disability insurance for all temporarily disabling conditions that might prevent them from working, except pregnancy. According to the conventional reading of Geduldig , the Court held categorically that the regulation of pregnancy is never sex based, so that such regulation warrants very deferential scrutiny from the courts.

The conventional wisdom about Geduldig , however, is incorrect. The Geduldig Court did not hold that governmental regulation of pregnancy never qualifies as a sex classification. Rather, the Geduldig Court held that governmental regulation of pregnancy does not always qualify as a sex classification. 24 The Court acknowledged that “distinctions involving pregnancy” might inflict “an invidious discrimination against the members of one sex or the other.” 25 This reference to invidiousness by the Geduldig Court is best understood in the same way that Wendy Williams’s brief in Geduldig used the term “invidious”—namely, as referring to traditional sex-role stereotypes. 26 Particularly in light of the Court’s recognition in Nevada Department of Human Resources v. Hibbs 27 that pregnant women are routinely subject to sex-role stereotyping, 28 Geduldig should be read to say what it actually says, not what most commentators and courts have assumed it to say.

Geduldig was decided at the dawn of the Court’s sex discrimination case law and at the dawn of the Court’s modern substantive due process jurisprudence. The risk of traditional sex-role stereotyping and stereotyping around pregnancy was developed more fully in later cases, including in twenty-five years of litigation over the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. 29 This explains why, when Hibbs was decided in 2003, the Court could reason about pregnancy in ways that the Geduldig Court contemplated in theory but could not register in fact.

III. The Political Authority of the Equal Protection Clause

We have thus far considered the distinctive concerns and grounds of equality arguments, which enable them to complement liberty arguments for abortion rights. We close by considering some distinctive forms of political authority that equality arguments confer.

Some critics pejoratively refer to certain of the Court’s Due Process decisions as recognizing “unenumerated” constitutional rights. Although there are two Due Process Clauses in the Constitution, these interpreters regard decisions like Roe , Casey , and Lawrence , which recognize substantive rather than procedural due process rights, as lacking a basis in the text of the Constitution, hence as recognizing “unenumerated rights.”

The pejorative “unenumerated rights” is often deployed against Roe and Lawrence in an ad hoc manner, without clarification of whether the critic of unenumerated rights is prepared to abandon all bodies of law that have similar roots or structure. For example, those who use the objection from unenumerated rights to attack Roe and Lawrence generally assume that the First Amendment limits state governments; but of course, incorporation of the Bill of Rights against the states is also a feature of the Court’s substantive due process doctrine. 30 Other “unenumerated rights” to which most critics of Roe and Lawrence are committed include the applicability of equal protection principles to the conduct of the federal government. 31 And this view cannot readily distinguish other “unenumerated” rights of unquestioned authority, such as the rights to travel (or not), 32 marry (or not), 33 procreate (or not), 34 and use contraceptives (or not). 35 At their Supreme Court confirmation hearings, Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito learned from the experience of Judge Robert Bork by swearing allegiance to Griswold .

But even if the pejorative term “unenumerated” is deployed selectively and inconsistently, it has frequently been deployed in such a way as to affect popular perceptions of Roe ’s authority. Accordingly, in light of criticism of the abortion right as “unenumerated,” it is worth asking whether grounding the right in the Equal Protection Clause, as well as the Due Process Clauses, can enhance the political authority of the right.

Adding claims on the Equal Protection Clause to the due process basis for abortion rights can strengthen the case for those rights in constitutional politics as well as constitutional law. The Equal Protection Clause is a widely venerated constitutional text to which Americans across the political spectrum have long laid claim. And crucially, once the Supreme Court recognizes that people have a right to engage in certain conduct by virtue of equal citizenship, Americans do not count stripping them of this right as an increase in constitutional legitimacy. We cannot think of a precedent for this dynamic. And so: If the Court were to recognize the abortion right as an equality right, a future Court might be less likely to take this right away.

This understanding has increasingly come to shape constitutional law. We have documented the Supreme Court’s equality-informed understanding of the Due Process Clause in Lawrence and Casey . We have also identified the growing number of justices who view the Equal Protection Clause as an independent source of authority for abortion rights. We view this reading of the substantive due process and equal protection cases as contributing to a synthetic understanding of the constitutional basis of the abortion right—as grounded in both liberty and equality values. For a variety of reasons this Essay has explored, the synthetic reading leaves abortions right on stronger legal and political footing than a liberty analysis alone.

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). ↩

- See infra Part III on the political authority of the Equal Protection Clause. ↩

- For examples of work in the equality tradition that emerged in the years before Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey , 505 U.S. 833 (1992), see Laurence H. Tribe, American Constitutional Law § 15-10, at 1353–59 (2d ed. 1990); Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Some Thoughts on Autonomy and Equality in Relation to Roe v. Wade, 63 N.C. L. Rev. 375 (1985); Sylvia A. Law, Rethinking Sex and the Constitution , 132 U. Pa. L. Rev. 955 (1984); Catharine A. MacKinnon, Reflections on Sex Equality Under Law , 100 Yale L.J. 1281 (1991); Reva Siegel, Reasoning From the Body: A Historical Perspective on Abortion Regulation and Questions of Equal Protection , 44 Stan. L. Rev. 261 (1992) [hereinafter Siegel, Reasoning From the Body ]; and Cass R. Sunstein, Neutrality in Constitutional Law (With Special Reference to Pornography, Abortion, and Surrogacy) , 92 Colum. L. Rev. 1 (1992). For more recent sex equality work, see, for example, What Roe v. Wade Should Have Said: The Nation’s Top Legal Experts Rewrite America’s Most Controversial Decision (Jack M. Balkin ed., 2005) (sex equality opinions by Jack Balkin, Reva Siegel, and Robin West); and Reva B. Siegel, Sex Equality Arguments for Reproductive Rights: Their Critical Basis and Evolving Constitutional Expression , 56 Emory L.J. 815, 833–34 (2007) [hereinafter Siegel, Sex Equality Arguments for Reproductive Rights ] (surveying equality arguments after Casey ). ↩

- See, e.g. , Siegel, Sex Equality Arguments for Reproductive Rights , supra note 3, at 817–22. ↩

- See id. at 819. ↩

- See generally Siegel, Reasoning From the Body , supra note 3. ↩

- 539 U.S. 558 (2003). ↩

- Id. at 578. ↩

- Id. at 575. ↩

- Thus the Court wrote that the very “continuance” of Bowers v. Hardwick , 478 U.S. 186 (1986), “as precedent demeans the lives of homosexual persons.” Lawrence , 539 U.S. at 575. ↩

- 505 U.S. 833 (1992). ↩

- Id. at 852. ↩

- Id. at 856. ↩

- Id. at 898. ↩

- Id. at 928 (Blackmun, J., concurring in part, concurring in the judgment in part, and dissenting in part). ↩

- Id. ↩

- 550 U.S. 124 (2007). ↩

- Id. at 172 (Ginsburg, J., dissenting). For an argument that “equal citizenship stature” is central to Justice Ginsburg’s constitutional vision, see generally Neil S. Siegel, “Equal Citizenship Stature”: Justice Ginsburg’s Constitutional Vision , 43 New Eng. L. Rev. 799 (2009). ↩

- 518 U.S. 515 (1996). ↩

- Id. at 534. ↩

- See generally Neil S. Siegel, The Virtue of Judicial Statesmanship , 86 Tex. L. Rev. 959, 1014–30 (2008); Reva B. Siegel, Dignity and the Politics of Protection: Abortion Restrictions Under Casey / Carhart, 117 Yale L.J. 1694 (2008). ↩

- 417 U.S. 484 (1974). ↩

- See Neil S. Siegel & Reva B. Siegel, Pregnancy and Sex Role Stereotyping: From Struck to Carhart, 70 Ohio St. L.J. 1095, 1111–13 (2009); Reva B. Siegel, You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby: Rehnquist’s New Approach to Pregnancy Discrimination in Hibbs, 58 Stan. L. Rev. 1871, 1891–97 (2006). ↩

- Geduldig , 417 U.S. at 496–97 n.20. ↩

- See Brief for Appellees at 38, Geduldig , 417 U.S. 484 (No. 73-640), 1974 WL 185752, at *38 (“The issue for courts is not whether pregnancy is, in the abstract, sui generis, but whether the legal treatment of pregnancy in various contexts is justified or invidious. The ‘gross, stereotypical distinctions between the sexes’ . . . are at the root of many laws and regulations relating to pregnancy.” (quoting Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677, 685 (1973))). ↩

- 538 U.S. 721 (2003). ↩

- Id. at 731 (majority opinion of Rehnquist, C.J.) (asserting that differential workplace leave policies for fathers and mothers “were not attributable to any differential physical needs of men and women, but rather to the pervasive sex-role stereotype that caring for family members is women’s work”); id. at 736 (quoting Congress’s finding that the “prevailing ideology about women’s roles has . . . justified discrimination against women when they are mothers or mothers-to-be” (citation omitted) (internal quotation marks omitted)). ↩

- Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(k) (2006) (“The terms ‘because of sex’ or ‘on the basis of sex’ include, but are not limited to, because of or on the basis of pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions; and women affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions shall be treated the same for all employment-related purposes . . . .”). Concerns about sex-role stereotyping played a significant part in Congress’s decision to amend Title VII . See, e.g. , H.R. Rep. No. 95-948, at 3 (1978) (“[T]he assumption that women will become [pregnant] and leave the labor force leads to the view of women as marginal workers, and is at the root of the discriminatory practices which keep women in low-paying and dead-end jobs.”). ↩

- See, e.g. , McDonald v. City of Chicago, 130 S. Ct. 3020, 3050 (2010) (Scalia, J., concurring) (“Despite my misgivings about Substantive Due Process as an original matter, I have acquiesced in the Court’s incorporation of certain guarantees in the Bill of Rights ‘because it is both long established and narrowly limited.’” This case does not require me to reconsider that view, since straightforward application of settled doctrine suffices to decide it.” (quoting Albright v. Oliver, 510 U.S. 266, 275 (1994))). ↩

- See Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) (holding that de jure school segregation in Washington, D.C. violates the equal protection component of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment); see also, e.g. , Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200, 240 (1995) (Thomas, J., concurring in part and concurring in the judgment) (“These programs not only raise grave constitutional questions, they also undermine the moral basis of the equal protection principle. Purchased at the price of immeasurable human suffering, the equal protection principle reflects our Nation’s understanding that such classifications ultimately have a destructive impact on the individual and our society.” (emphasis added)). ↩

- See Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) (right to travel as a fundamental right). ↩

- See Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374 (1978) (right to marry as a fundamental right); Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) (same). ↩

- See Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) (right to procreate as a fundamental right). ↩

- See Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972) (right to contraception for all individuals as a fundamental right); Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) (right to contraception for married couples as a fundamental right). ↩

- Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 172 (2007) (Ginsburg, J., dissenting). ↩

Share this:

About the author.

Neil S. Siegel is Professor of Law and Political Science, Co-Director, Program in Public Law, Duke Law School. Reva B. Siegel is Nicholas deB. Katzenbach Professor of Law, Yale University.

Special Education Entwinement

Abstract The privatization of public K-12 education in the United States has accelerated dramatically in recent years, blurring the line between public and private schooling. This shift has raised critical constitutional and statutory questions...

Racial Reckoning and the Police-Free Schools Movement

Abstract Across the country, students of color face daily threats of arrest, exclusion, and violence at the hands of school police officers. Whether deemed threatening, defiant, or hypersexualized, Black students, in particular, pay a heavy price to...

The War on Higher Education

Abstract Higher education is under assault in the United States. Tracking authoritarian movements across the globe, domestic attacks on individual professors and academic institutions buttress a broader campaign to undermine multiracial democracy...

Bringing Visibility to AAPI Reproductive Care After Dobbs

Abstract Dobbs’ impact on growing AAPI communities is underexamined in legal scholarship. This Essay begins to fill that gap, seeking to bring together an overdue focus on the socio-legal experiences of AAPI communities with examination of the...

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The legalization of abortion is a complex social issue influenced by consistent global abortion rates, varying public opinion, and the need for safe, legal procedures. State and international laws reflect the diverse approaches and ethical considerations surrounding this debate.

Introduction to Abortion Essay 1. Understanding the Topic: Abortion. Abortion is a highly debated and sensitive topic that revolves around the termination of a pregnancy before the fetus can survive outside the womb. It raises complex moral, ethical, and legal questions.

The bill would legalize abortion during the first 14 weeks of pregnancy—and later, if the pregnancy resulted from rape or threatened the person’s life or health, exceptions currently allowed...

Why Abortion Should Be Legalized. This essay provides an example of an argumentative essay that argues for the legalization of abortion. It emphasizes women's rights, reducing crime, and addressing pregnancies resulting from sexual assault.

Democrats are divided about whether abortion should be legal or illegal at 24 weeks, with 34% saying it should be legal, 29% saying it should be illegal, and 21% saying it depends. There also is considerable division among each partisan group by ideology.

Access to safe, legal abortion is a matter of human rights. Authoritative interpretations of international human rights law establish that denying women, girls, and other pregnant people access...

Four states legalized abortion, and a dozen or so adopted some form of the model law, which permitted abortion in cases of rape, incest and fetal abnormality, as well as to save the life or...

About a third of U.S. adults (36%) say abortion should be illegal in all (8%) or most (28%) cases. Generally, Americans’ views of whether abortion should be legal remained relatively unchanged in the past few years, though support fluctuated somewhat in previous decades.

The prevailing view among adults who say abortion should be legal in all circumstances is that abortion is not a moral issue (44%), though notable shares of this group also say it is morally acceptable in all (27%) or most (22%) cases.

In this Essay, we describe some distinctive features of equality arguments for abortion rights. We then show how, over time, the Court and individual Justices have begun to employ equality arguments in analyzing the constitutionality of abortion restrictions.