- Create new account

- Reset your password

Register and get FREE resources and activities

Ready to unlock all our resources?

An overview of the Welsh education system

The education system in Wales used to resemble the structure set up in England , with maintained schools (most state schools) following the National Curriculum. However, from September 2022 a new curriculum will be introduced that has been created in Wales by teachers, partners, practitioners and businesses. The age of a child on 1 September determines when they need to start primary school.

From September 2022 , phases and key stages will be replaced with one continuum of learning from ages 3 to 16 in each of the new areas of learning. The areas are:

1. Expressive arts

2. Humanities

3. Health and wellbeing

4. Science and technology

5. Mathematics and numeracy

6. Languages, literacy and communication

In addition, literacy, numeracy and digital skills will be embedded throughout all curriculum areas.

Boost your child's maths & English skills!

- We'll create a tailored plan for your child...

- ...and add activities to it each week...

- ...so you can watch your child grow in skills & confidence

What about teaching in Welsh?

The Welsh Government wants to make sure that children can be educated in Welsh if there’s a need or demand for it, so Welsh is taught as a part of the curriculum in all schools up to the age of 16 . Schools have the option to teach lessons entirely or mostly in Welsh – this includes English-medium schools (schools where children are taught in English).

‘Welsh-medium’ schools are schools where children are taught in Welsh. Children going to these schools also get a good grounding in English language skills, but schools are not required by law to teach English in Years 1 and 2.

Does the curriculum in Wales have a Welsh slant?

Take the subject of history, for example. Welsh schools are given discretion on exactly what to teach in history within the curriculum. Although they’re encouraged to focus on historical figures and events from their local area and around Wales in the first instance, they’re also free to include topics involving Britain as a while.

What tests do pupils in Wales take?

Statutory teacher assessments are usually administered at the end of Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 3, as in England, but students do not take Key Stage 2 National Curriculum Tests (Standard Attainment Tests, or SATs) .

However, Key Stage 2 assessments will not continue from September 2022 and Key Stage 3 assessments are to end when the new curriculum rollout has been completed (by 2024).

Since May 2013, all children in Wales from Y2 to Y9 have taken National Reading and Numeracy Tests as part to a new National Literacy and Numeracy Framework (LNF). These will continue with the new curriculum in 2022.

Students take General Certificate of Secondary Education exams (GCSEs) during year 11, and have the choice to continue on to Years 12 and 13 to sit A-level exams.

Please note: the table below is best viewed on a desktop (not mobile) screen.

When is the new curriculum for Wales being introduced?

The new curriculum for Wales will be introduced in school classrooms from nursery to Year 7 in 2022, rolling into Year 8 in 2023, Year 9 in 2024, Year 10 in 2025 and Year 11 in 2026. All schools will have access the final curriculum from 2020, to allow them to move towards full roll-out in 2022.

Give your child a headstart

- FREE articles & expert information

- FREE resources & activities

- FREE homework help

More like this

- Education spending

Major challenges for education in Wales

- Luke Sibieta

Published on 21 March 2024

This report examines the major challenges for education in Wales, including low outcomes across a range of measures and high levels of inequality.

- Education and skills

- Poverty, inequality and social mobility

- Human capital

Download the report

PDF | 583.29 KB

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Economic and Social Research Council via the ESRC Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy. This report also draws heavily on analysis and knowledge gained by the author in his work as a Research Fellow at the Education Policy Institute.

Executive summary

Last December, the OECD published the latest round of PISA tests in reading, maths and science skills. These international comparisons always prompt public debate. Most countries saw declining scores, reflecting the effects of the pandemic. In Wales, the declines were particularly large, erasing all the progress seen since 2012. This report argues that low scores in Wales are a major concern and challenge for the new First Minister. Low educational outcomes are not likely to be a reflection of higher poverty in Wales, a different ethnic mix of pupils, statistical biases or differences in resources. They are more likely to reflect differences in policy and approach. We recommend that policymakers and educators in Wales pause, and in some cases rethink, past and ongoing reforms in the following areas:

- The new Curriculum for Wales should place greater emphasis on specific knowledge.

- Reforms to GCSEs should be delayed to give proper time to consider their effects on long-term outcomes, teacher workload and inequalities.

- More data on pupil skill levels and the degree of inequality in attainment are needed and should be published regularly.

- A move towards school report cards, alongside existing school inspections, could be an effective way to provide greater information for parents without a return to league tables.

Related content

Sliding education results and high inequalities should prompt big rethink in welsh education policy, key findings.

- PISA scores declined by more in Wales than in most other countries in 2022, with scores declining by about 20 points (equivalent to about 20% of a standard deviation, which is a big decline). This brought scores in Wales to their lowest ever level, significantly below the average across OECD countries and significantly below those seen across the rest of the UK. Scotland and Northern Ireland also saw declines in PISA scores in 2022, whilst scores were relatively stable in England.

- Lower scores in Wales cannot be explained by higher levels of poverty. In PISA, disadvantaged children in England score about 30 points higher, on average, than disadvantaged children in Wales. This is a large gap and equivalent to about 30% of a standard deviation. Even more remarkably, the performance of disadvantaged children in England is either above or similar to the average for all children in Wales.

- These differences extend to GCSE results. In England, the gap in GCSE results between disadvantaged and other pupils was equivalent to 18 months of educational progress, which is already substantial, in 2019 before the pandemic. In Wales, it was even larger at 22–23 months in 2019 and has hardly changed since 2009. The picture is worse at a local level. Across England and Wales, the local areas with the lowest performance for disadvantaged pupils are practically all in Wales. There are many areas of England with higher or similar levels of poverty to local areas in Wales, but which achieve significantly higher GCSE results for disadvantaged pupils, e.g. Liverpool, Gateshead and Barnsley.

- A larger share of pupils in England are from minority ethnic or immigrant backgrounds than in Wales. Such pupils tend to show higher levels of performance. However, even this cannot explain lower scores in Wales, as second-generation immigrants also tend to show lower levels of performance in Wales than in England.

- The differences in educational performance between England and Wales are unlikely to be explained by differences in resources and spending. Spending per pupil is similar in the two countries, in terms of current levels, recent cuts and recent trends over time.

- There are worse post-16 educational outcomes in Wales, with a higher share of young people not in education, employment or training than in the rest of the UK (11% compared with 5–9%), lower levels of participation in higher education (particularly amongst boys) and lower levels of employment and earnings for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

- The explanation for lower educational performance is much more likely to reflect longstanding differences in policy and approach, such as lower levels of external accountability and less use of data.

- There are important lessons for policymakers in Wales from across the UK. The new Curriculum for Wales is partly based on the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence, with both having noble aims to broaden the curriculum, improve well-being and focus on skills. However, there is now evidence arguing that these quite general skills-based curricula might not be effective ways to develop those skills. New GCSEs are due to be taught in Wales from 2025, including greater use of assessment, a broader range of subjects and the removal of triple science as an option. These reforms run the risk of widening inequalities, increasing teacher workload and limiting future education opportunities. There is much greater use of data to understand differences in outcomes and inequalities in England. This could easily be emulated in Wales without a return to school league tables.

1. Introduction

In December 2023, the OECD published the latest round of PISA scores (OECD, 2023). These international comparisons of reading, maths and science skills always prompt significant public debate, particularly in countries seeing declining scores. The latest tests were taken in 2022. Most countries saw declining scores, reflecting the effects of school closures during the pandemic.

In Wales, scores declined significantly, with the lowest test scores across the four nations of the UK. This erased all the increases seen in Wales since 2012 , when low PISA test scores last prompted soul-searching in the Welsh education system. This time, concern about low scores within Wales has been relatively brief, with the Minister emphasising ongoing reforms (Miles, 2023). This contrasts with the picture elsewhere in the UK. In Scotland , low and declining scores have prompted significant public debate and have led the Minister to promise improvements to the system (Gilruth, 2023). In England , ministers have claimed credit for relatively high scores and an improvement in relative scores compared with other countries. There were also declines in Northern Ireland, though public debate has been mostly focused on the restoration of the Northern Ireland Executive.

This short report argues that low education outcomes, high levels of inequality and their consequences for children’s life chances represent a major challenge for the new First Minister of Wales. Improving this situation should be an urgent priority for his new government.

2. Overall performance and inequalities in Wales

This section sets out the overall performance of pupils in Wales in PISA tests over time, overall levels of inequality and how this compares with the rest of the UK.

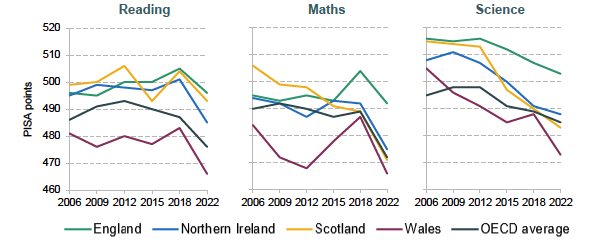

Large declines in reading, maths and science skills in Wales

Starting with the overall picture, Figure 1 shows that PISA test scores in Wales fell significantly in maths, reading and science in 2022. To some extent, this matches the decline seen across other OECD countries following the global pandemic. However, there was a steeper fall in Wales in reading and science. Scores in Wales are also now lower than in any previous PISA cycle. The declines in Wales represented about 20 PISA points, on average. This is equivalent to about 20% of a standard deviation, which is a substantial decline.

Figure 1. PISA scores across UK nations over time

Source: Based on figures 7.13–7.15 in Sizmur et al. (2019); OECD (2023).

We also saw large falls over time in maths and science in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Across both nations, there were smaller falls in reading scores, which remain above the OECD average.

In England, we see a different picture. Reading and maths skills were increasing gradually between 2006 and 2018. There was then a relatively small decline in both reading and maths scores in 2022, taking them back to the same levels as around 2012/2015. Given the scale of disruption to education during the pandemic and the declines seen across other OECD countries, a small decline and general stable pattern over the last 10 years is likely to be a positive sign of resilience in England.

Whilst there were declines in science scores in England in 2022, Jerrim (2024) argues that this decline is seen across most OECD countries and may reflect methodological changes in the survey over time. Science scores in England also remain well above the OECD average.

Larger inequalities in Wales

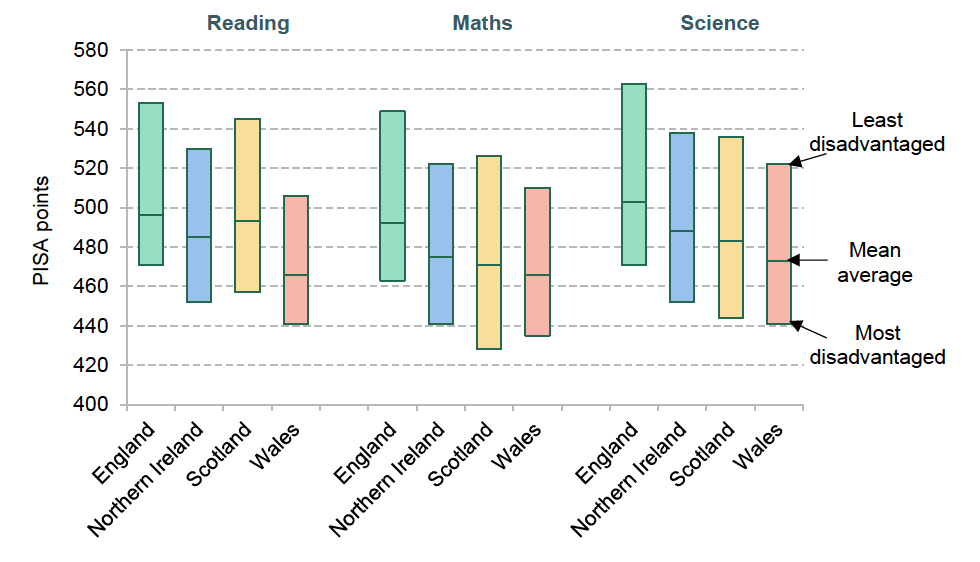

Equally concerning are the level of performance of disadvantaged pupils and the state of educational inequalities in Wales, which are visible in both PISA and GCSE results. Figure 2 shows the mean PISA scores in each nation and subject for those in the most and least disadvantaged groups (bottom and top quartiles of the OECD’s index of economic, social and cultural status, ESCS), together with the mean scores for all children, in 2022.

Figure 2. Average PISA scores for most disadvantaged, least disadvantaged and all by nation and subject area in 2022

Source: Department for Education, 2023.

The gaps in performance between the most and least disadvantaged groups are broadly similar across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and are perhaps a little larger for Scotland in reading and maths. However, the difference in levels between England and other nations of the UK by level of disadvantage is very stark. For the least disadvantaged group, we see that scores in England are about 25–30 PISA points higher than in the other nations of the UK, on average. Some of this is likely to be explained by higher incomes at the top end of the spectrum in England. However, it is notable that scores for the least disadvantaged 25% of children in Wales are only barely above the average for all children in England.

At the other end of the distribution, disadvantaged children in Wales have the lowest scores across all four nations for reading and science (and the second-lowest for maths, just above the very low maths scores for disadvantaged children in Scotland). Disadvantaged children in England score about 30 points higher, on average, than disadvantaged children in Wales. This is a large gap and equivalent to about 30% of a standard deviation. Indeed, the performance of disadvantaged children in England is either above or similar to the average for all children in Wales.

Why we should care about the reasons for low PISA scores

Before thinking about the factors driving low PISA scores in Wales and policy implications, it is important to ask whether PISA scores actually matter. There are no prizes for a high PISA ranking, except kudos, and there are no immediate consequences, except pressure on policymakers. It is also important to focus on the actual scores, rather than rankings or relative performance. Education is not a zero-sum game. If all countries saw an equally large rise in scores, we are all likely to be better off.

PISA scores matter because they are a valuable and comparable indicator of young people’s skills in reading, numeracy and science. These are fundamental skills for accessing the rest of the curriculum and for achieving education qualifications. There is an enormous body of evidence that shows how skills and educational qualifications lead to greater chances of employment, higher earnings, higher productivity, improved health outcomes, lower crime, and the list goes on as evidence improves (Hanushek et al., 2015; Psacharopoulos and Patrinos, 2018).

Furthermore, there is a great deal of evidence showing that Welsh young people experience worse educational and labour market outcomes after leaving school than young people in the rest of the UK. A recent EPI/SKOPE report shows that young people in Wales have the lowest participation in higher education across the UK, with Welsh boys seeing particularly poor trends over the last 15 years (Robson et al., 2024). We also see that the share of young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) is higher in Wales than in the rest of the UK. In 2022–23 , 11% of 16- to 18-year-olds in Wales were NEET, as compared with 5–9% across the rest of the UK. A similar picture emerges for 19- to 24-year-olds. In the labour market, we also see that Welsh young people from working-class backgrounds have lower earnings and lower employment levels than working-class young people from other UK nations.

The inescapable truth is that disadvantaged pupils in Wales have low skill levels and low levels of educational attainment. This drives a high disadvantage gap, reduces opportunities in the labour market and perpetuates inequalities. This will act as a drag on growth and living standards.

3. Explanations for lower performance in Wales

In this section, we gradually examine the potential explanations for lower levels of educational performance in Wales, including the statistical biases and the roles of poverty, ethnic mix, resources, the curriculum, accountability and assessments.

Statistical concerns and biases

To what extent do lower PISA scores in Wales reflect statistical concerns and biases? Some caution is always needed when interpreting exact changes across countries over time, particularly as PISA scores are based on a sample of children in each nation across each cycle. There are also sources of potential bias specific to the UK and Wales, with the OECD warning that low response rates could be creating biases within the UK this year. Jerrim (2023) has written about the curious issue of the implausibly low scores of pupils taking the test in Welsh, which could be biasing Welsh scores downwards. However, such biases are likely to be modest (less than 10 points) and have been known to affect previous years (Jerrim, Lopez-Agudo and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, 2022).

In general, one should focus on the general trends and levels over time. For Wales, this is a picture of low test scores across all three subject areas, below the OECD average and lower than the rest of the UK. Furthermore, as shown below, the fact that we see higher GCSE inequalities and worse post-16 educational and labour market outcomes in Wales strongly suggests that PISA is capturing a real issue in the Welsh education system.

Higher poverty is not the explanation

There will be differences between disadvantaged children in Wales and England that explain some of these differences in skill levels. However, there is likely to be a high degree of socio-economic similarity between the disadvantaged groups across England and Wales (we look at differences by ethnic background below). These groups are mainly made up of families reliant on means-tested benefits or on minimum wage levels, which will be very similar across the two nations. As of January 2019, the share of children eligible for free school meals was about 18% in Wales , which is only slightly larger than the 15% in England . Furthermore, about 8–9% of pupils were persistently eligible for free school meals (FSM) across both nations, suggesting similar levels of persistent poverty (Cardim-Dias and Sibieta, 2022). Transitional protections under universal credit make it difficult to present more recent statistics in a comparable way.

Differences in GCSE specifications between England and Wales make it difficult to compare absolute or raw results. However, Cardim-Dias and Sibieta (2022) show that one can produce reliable comparisons of inequalities in GCSE results, and the gap in performance between disadvantaged and other pupils. This analysis presents the disadvantage gap in terms of months of educational progress, where 11 months would be the expected difference in performance between a child born in September and one born in August.

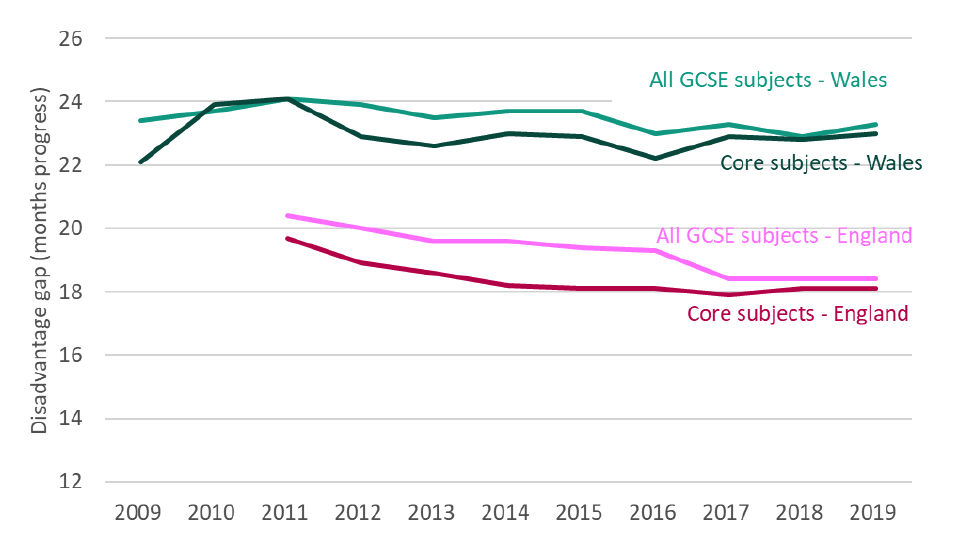

As shown in Figure 3, Cardim-Dias and Sibieta (2022) show higher inequalities in GCSE results in Wales than in England. Before the pandemic, disadvantaged pupils in Wales were the equivalent of 22–23 months of educational progress behind their peers, compared with a gap of 18 months in England.

Figure 3.Disadvantage gap in GCSE results in Wales and England over time (months of educational progress; disadvantaged defined as ever eligible for FSM in past six years)

Note: Core subjects are English/Welsh, maths and science.

Source: Reproduced from Cardim-Dias and Sibieta (2022) with kind permission.

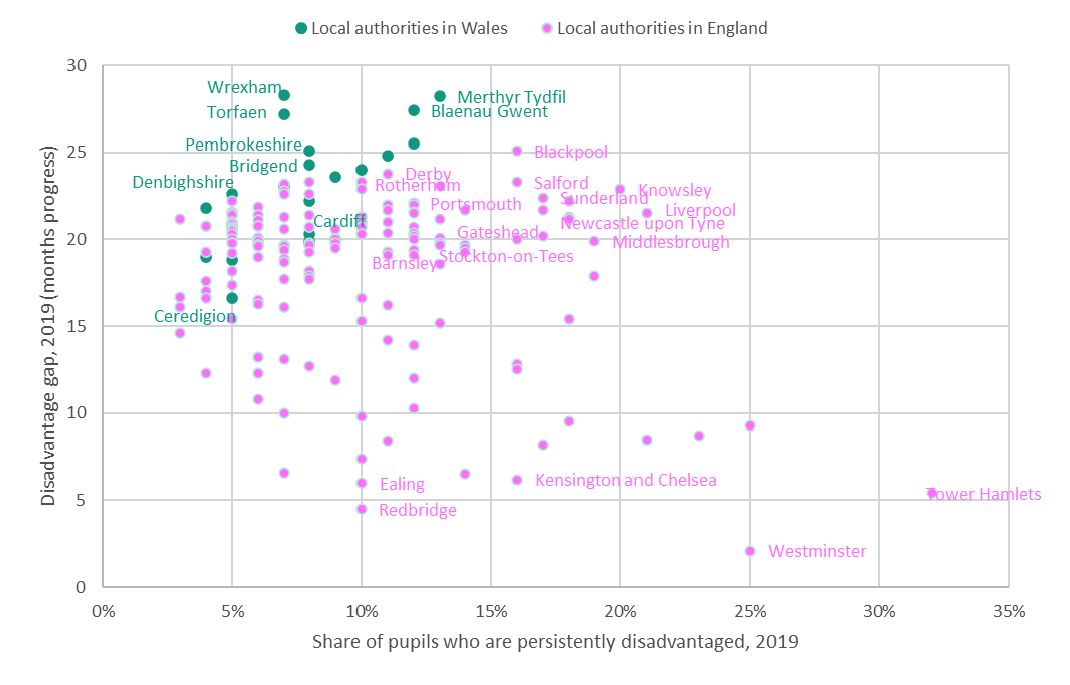

The results are even more stark at a local level, as shown in Figure 4. Across England and Wales, the local authorities with the worst performance for disadvantaged pupils are practically all in Wales. Before the pandemic, there were seven local authorities in Wales where disadvantaged pupils were at least 25 months behind their peers at the national level: Torfaen, Wrexham, Blaenau Gwent, Merthyr Tydfil, Neath Port Talbot, Rhondda Cynon Taf and Pembrokeshire. In England, this was only the case for Blackpool. Furthermore, there are many local authorities in England with similar levels of deprivation and demographics to deprived areas in Wales, but which manage to achieve a lower disadvantage gap – for example, Salford, Gateshead and Portsmouth. There are also places with much higher levels of persistent disadvantage that achieve lower disadvantage gaps, such as Liverpool and Newcastle. The low performance of disadvantaged pupils in Wales is simply not an inevitable result of high levels of deprivation.

Figure 4. Relationship between persistent disadvantage and the disadvantage gap across local authorities in Wales and England

Note: Pupils are classed as persistently disadvantaged if they were eligible for free school meals for 80% of their time in school. Disadvantage gap is measured in terms of GCSE results.

To be clear, the overall level of the disadvantage gap and educational inequalities in England are substantial, with a national disadvantage gap of 18 months before the pandemic and much evidence to suggest that this has been getting even worse over recent years (Babbini et al., 2023). But the picture in Wales looks even worse than this. This greater disadvantage gap cannot be explained by higher levels of disadvantage in Wales. Areas of England with similar or higher levels of disadvantage manage to achieve lower levels of educational inequality. The explanation must lie elsewhere.

Role of immigrants and ethnic make-up

Perhaps the most significant difference is the ethnic make-up of each nation. Over 30% of pupils in England are from minority ethnic backgrounds, compared with about 10% in Wales . Over 20% of 15-year-olds in England were from first- or second-generation immigrant backgrounds in 2022, compared with 10% in Wales (OECD, 2023). This matters, as the evidence clearly shows that ethnic minorities and those from immigrant backgrounds generally perform very well in England (Wilson, Burgess and Briggs, 2011; OECD, 2023). These differences seem likely to be accentuated amongst the disadvantaged group, and may explain some of the lower performance in Wales. However, there are reasons to doubt that this explains a large element of lower skill levels in Wales.

According to PISA, non-immigrants in England score about 30 PISA points higher in maths than non-immigrants in Wales. We also see that immigrants score about 20 PISA points higher in England than in Wales. Immigrants and non-immigrants alike have higher levels of performance in England. Indeed, the high performance of immigrants is an under-appreciated success of the English education system. As Freedman (2024) has pointed out, England is the only European country where second-generation immigrants outperform non-immigrants in PISA. If second-generation immigrants in England were a country, they would have similar maths scores to high-performing countries such as Canada and Estonia, and be not far behind Korea and Japan.

How much do resources matter?

Resources and spending also differ across the UK (Sibieta, 2023). In Scotland, spending per pupil has long been higher and class sizes lower than in the rest of the UK (Jerrim and Sibieta, 2021). Following a further boost since 2018, spending per pupil in Scotland is at least 18% or £1,300 higher than elsewhere in the UK. Spending levels and trends are more similar in Wales, England and Northern Ireland. There were real-terms cuts to spending per pupil between 2010 and 2019, which are now being gradually reversed (Sibieta, 2023).

With England showing higher levels of skills than high-spending Scotland, one naturally asks whether school spending matters all that much. The answer is still yes. Correlations of spending across time and countries provide little information on the true effects of higher spending on educational outcomes. We have excellent evidence showing increasing levels of school spending does improve educational outcomes, and probably more so for disadvantaged students (Jackson and Mackevicius, 2024). This remains relevant and can help us interpret differences across nations.

In Scotland, we see historical levels of higher spending and recent large increases. An entirely plausible explanation is that higher levels of skills in Scotland in the past could be partly explained by greater resources. Recent declines could be explained by negative effects of reforms outweighing the effects of extra spending, and potentially by reforms reducing the bang-for-buck from extra resources.

In England, we see stable scores at a time of reduced spending per pupil and resilience in the face of a global pandemic. A very plausible explanation is that reforms to the system, such as the knowledge-rich curriculum and focus on basic literacy and numeracy, could have had positive effects, which may have been slightly diminished by reduced spending. This has the additional implication that the current English system may well be characterised by high bang-for-buck from extra spending.

This has some important lessons for policymakers in Wales considering the role of extra resources. How much you spend and how you spend it are often seen as competing factors. This is an entirely false trade-off. They both matter in complementary ways. A well-functioning and high-performing system is likely to generate large gains from extra spending. Throwing money at a poorly-performing system will likely produce disappointing results.

Curriculum changes: knowledge versus skills

One of the biggest school policy differences across the four nations of the UK has been curriculum reform. Scotland (from 2010) and Northern Ireland (from 2007) have already implemented skills-based curricula, which focus on the development of skills and competencies. The new Curriculum for Wales , implemented from 2022 onwards, takes a similar approach and is partly modelled on the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence. The National Curriculum in England is very different. The most recent version was implemented from 2014 onwards and focuses on whether pupils have specific elements of knowledge.

The Curriculum for Wales aims to develop general skills and defines four key purposes:

- ambitious, capable learners, ready to learn throughout their lives;

- enterprising, creative contributors, ready to play a full part in life and work;

- ethical, informed citizens of Wales and the world;

- healthy, confident individuals, ready to lead fulfilling lives as valued members of society.

Learning is organised into six different areas of learning (combining many traditional subject domains). A high emphasis is also placed on health and well-being. Schools then have significant autonomy to define the specific elements of their own curriculum as long as they are progressing towards the general definitions of skills. This is intended to achieve a broad and balanced curriculum.

These are of course very noble and sensible aims. The trouble is that defining the curriculum in terms of general skills might not actually be a good way to develop those skills in the first place. Whilst many of the skills seem like good long-term goals for an education system, Christodoulou (2023) argues that it is more effective to break those skills down into the teaching of specific elements of knowledge. Assessing generic skills is also incredibly difficult. As a result, skill-based curricula can lead to significant inequalities in the curriculum content that pupils are exposed to, and in the ways in which they are assessed. Indeed, based on pilots of the new curriculum, education researchers in Wales have already warned that the new curriculum risks exacerbating existing inequalities without external accountability on curriculum design and assessment, and extra investment (Power, Newton and Taylor, 2020).

Paterson (2023) also argues that the reduction in science and maths scores in Scotland and Northern Ireland, alongside stable reading scores, is the pattern one might expect following the introduction of skills-based curricula. Reading is a relatively general skill that parents can assist with. Maths and science require more specific knowledge that parents might find harder to impart. This seems like a reasonable conclusion. However, it would be near impossible to definitively conclude that it is the adoption of skills-based curricula that has led to lower scores in Scotland and Northern Ireland, and that a knowledge-based curriculum has improved scores in England. Correlation is not causation. Furthermore, the improvements in reading in England appear longstanding, dating back to 2006 at least, and might not just be about the adoption of the new National Curriculum. The improvements may reflect the widespread adoption of synthetic phonics following the Rose Report in 2006, which has been shown to have had positive effects (Machin, McNally and Viarengo, 2018).

The trouble is, as argued by Crehan (2023), declines have happened in essentially every country that has adopted such skills-based curricula – for example, France, Finland, Australia and New Zealand, with the last thinking about ways to introduce specific knowledge elements into its curriculum.

Lastly, there is also no evidence to suggest that policymakers in Wales have been successful in achieving the broader aim of maximising pupil well-being. The 2022 PISA report for Wales (Ingram et al., 2023) shows that pupils in Wales report a lower score for overall life satisfaction than the OECD average and that a lower-than-average share of pupils felt like they belonged in school. Pupils reporting higher levels of life satisfaction and belonging tended to be those achieving higher scores on PISA tests.

At the very least, all this must leave us wary about the introduction of the skills-based Curriculum for Wales. Maybe Wales will totally buck the international trend. However, there is no good evidence showing that a skills-based curriculum will be able to turn around low scores and high inequalities seen in Wales.

Accountability and assessment: not measuring up

Another key difference across the four nations has been approaches to accountability and assessment. In England, there has long been a focus on high-stakes accountability, either through league tables, school-by-school data comparisons or Ofsted inspections with single-word judgements (often with high consequences for schools and their leadership teams). This can have benefits, in terms of high levels of accountability, but can also create perverse incentives to teach to the test, and the problems associated with high-pressured school inspections are now well known.

Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland abolished league tables long ago. Some evidence suggests this had a small negative effect in Wales (Burgess, Wilson and Worth, 2013), and a more general school categorisation system was introduced about 10 years ago. This has since been abolished and replaced by a system of self-evaluation by schools.

Since 2013, pupils aged 7–14 have sat literacy and numeracy tests of one form or another in Wales. However, the results from these have rarely been published in ways that allow us to track average skills levels or inequalities over time. For England, we have significant data on pupil skill levels from tests such as the phonics check and Key Stage 2 tests , and there are clear metrics comparing school performance with national and low benchmarks at pretty much every stage of education. Historically, such test scores have been used as part of school league tables. However, more important are the ways in which the data are used to track overall performance over time, to understand inequalities across pupils and areas, and for schools to compare their own levels with those of others. This approach to data on school comparisons was briefly part of the Welsh school system, but is not really encouraged any more. The Welsh Government has recently published data showing falling numeracy and reading levels since the pandemic, and it plans to publish more on inequalities in Spring 2024. This should ideally become a regular and systematic overview of skills levels and inequalities across time and place and enable schools to do comparisons to aid their understanding.

Accountability through school inspections occurs throughout Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. However, the immediate consequences from poor school inspection outcomes are less severe in Wales, except in the case of very poor inspection reports which can result in special measures. Single-word summary judgements have also been abolished, making it quite hard to discern the overall quality of schools from inspection reports. To be fair, policy and debate in England are also moving away from narrow, single-word judgements towards more holistic school report cards. It would be entirely feasible and sensible for Wales to adopt such an approach. It could include summaries from different parts of inspection reports, data on pupil attainment and inequalities, and wider aspects about the school environment and pupil well-being.

Assessments and exams have also been moving in different directions across the four nations of the UK. In Wales, the key developments have been retaining A*–G grades (instead of the numbers used in England), maintaining AS levels and creating GCSE specifications specific to Wales. This makes it harder, but not impossible, to undertake comparisons across the UK. New GCSEs in Wales will be taught from September 2025. These will be available in more vocational subjects and make more use of continuous assessments (e.g. coursework), and it will no longer be possible to study triple-science subjects of biology, chemistry and physics. These changes are being undertaken to broaden the set of available subjects and to align with the aims of the new curriculum. However, there are also clear risks with this approach. The benefits and returns to vocational GCSEs in England in the 2000s were pretty weak (see the 2011 Wolf Report), high levels of continuous assessment can increase inequalities (Kelly, 2023) and create more workload for teachers, and removing triple-science subjects risks capping the future educational opportunities of Welsh learners in science, medical and technological subjects.

4. Conclusions

The overwhelming conclusion is that the overall level of educational performance in Wales is low, and inequalities are high and persistent. Policymakers should be doing more to address the underlying reasons driving this disappointing set of results. At present, the most prominent education policies of the Welsh Government are the new Curriculum for Wales, free school meals in primary schools and a potential change in the school year. However, there is very little evidence that any of these policies will improve educational attainment or narrow inequalities.

The picture on schools in England appears rosier. However, it is important not to treat England as a perfect benchmark. There are also real problems in England. Inequalities are wide (and probably widening), there are significant problems recruiting and retaining teachers, there is huge pressure on the special educational needs system and there are also obvious concerns about a narrowing of the curriculum. This being said, there are still important lessons for policymakers in Wales.

Whilst it is important that policymakers in Wales make changes, it is also important that they do not panic. Now is the time for policymakers and educators to pause and in some cases rethink past and ongoing reforms to Welsh education in the following areas:

- The Curriculum for Wales should place greater emphasis on specific knowledge than it does now.

- The reform to GCSEs should be delayed to give proper time to consider how its aims and the evidence base fit with addressing poor performance and wide inequalities.

- A move towards school report cards, alongside the existing school inspections, could be an effective way to provide greater information for parents without a return to league tables.

Conversations on changes to the curriculum should happen with policymakers, teachers and schools inside and outside Wales. Rather than repeat mistakes, it is crucial to learn lessons from the Curriculum for Excellence alongside the Scottish Government. Much can be learnt from the current rethink in New Zealand, as well as other countries that are thinking about rowing back from skills-based curricula. There is also much that can be learnt from individual teachers and schools in England who have been at the forefront of the knowledge-rich curriculum.

The planned reforms to GCSEs in Wales are significant, with the introduction of more continuous assessment and changes to subjects. Key questions to ask include whether there is strong evidence that increased use of continuous assessment for GCSEs will improve educational performance and narrow gaping inequalities. Or will it increase workloads and inequalities? Are there better ways to achieve improvements? An open and evidence-based conversation will ultimately point to the right directions.

Policymakers should also publish better and more regular data on overall skills levels across young people in Wales at different ages, and the levels of inequality across pupils from different backgrounds and areas. Schools should be able and encouraged to compare themselves with other schools, as used to be the case. If this is not possible within the existing ways that literacy and numeracy test results are collected, then this should be changed to make it possible. Given the relatively low reading scores in Wales, a phonics check for children in Year 1 or Year 2 might be a very sensible addition too.

The movement towards school report cards in England also seems like a positive step that Wales could lead on. They could be incorporated into existing school inspections to provide parents with a clear summary of the performance and well-being of their children.

Publishing more data does not have to mean a return to school league tables, which have mostly been superseded by better and more sophisticated ways of using data. It is instead a confirmation for schools, parents and taxpayers that pupils are mastering key skills that are required to access the rest of the curriculum and wider education opportunities. One objection to focusing on tests in literacy and numeracy is that it narrows the curriculum, and there has been clear criticism in England of the way the English Baccalaureate has narrowed the curriculum (see Long and Danechi (2019)). However, this is not an inevitable consequence. Done right, skill tests and comparisons can ensure that pupils acquire foundational skills that enable them to access a wider curriculum and set of qualifications. Without basic skills and knowledge, a wider curriculum is a pipe dream.

Fundamentally, if you do not like the surprises from PISA every three years, then fill the void with better annual data so that PISA just ends up confirming what you already know. Ideally, this would be a picture of improving skills, lower inequalities and pupils accessing a wider curriculum. However, without reform or good data, there could be an even nastier surprise for Welsh policymakers when the next PISA results are published three years from now.

Babbini, N., Hunt, E., Robinson, D. and Tuckett, S., 2023. EPI Annual Report 2023. Education Policy Institute, https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/annual-report-2023/ .

Burgess, S., Wilson, D. and Worth, J., 2013. A natural experiment in school accountability: the impact of school performance information on pupil progress. Journal of Public Economics , 106, 57–67, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047272713001291 .

Cardim-Dias, J. and Sibieta, L., 2022. Inequalities in GCSE results across England and Wales. Education Policy Institute, https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/inequalities-in-gcse-results-across-england-and-wales/ .

Christodoulou, D., 2023. Skills vs knowledge, 13 years on. No More Marking blog, https://substack.nomoremarking.com/p/skills-vs-knowledge-13-years-on .

Crehan, L., 2023. https://twitter.com/lucy_crehan/status/1732038894336847942 .

Department for Education, 2023. PISA 2022: national report for England, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pisa-2022-national-report-for-england .

Freedman, S., 2024. The truth about integration. Comment is Freed blog, https://samf.substack.com/p/the-truth-about-integration .

Gilruth, J., 2023. Literacy and numeracy: Education Secretary statement. Scottish Government, https://www.gov.scot/publications/ministerial-statement-literacy-numeracy/ .

Hanushek, E., Schwerdt, G., Wiederhold, S. and Woessmann, L., 2015. Returns to skills around the world: evidence from PIAAC. European Economic Review , 73, 103–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.10.006 .

Ingram, J., Stiff, J., Cadwallader, S., Lee, G. and Kayton, H., 2023. PISA 2022: National Report for Wales. Welsh Government, https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2023-12/pisa-2022-national-report-wales-059.pdf .

Jackson, C.K. and Mackevicius, C.L., 2024, What impacts can we expect from school spending policy? Evidence from evaluations in the United States. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics , 16(1), 412–46, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20220279 .

Jerrim, J., 2023. Were PISA reading scores in Wales as bad as they first seemed? FFT Education Datalab, https://ffteducationdatalab.org.uk/2023/12/were-pisa-reading-scores-in-wales-as-bad-as-they-first-seemed/ .

Jerrim, J., 2024. How concerned should we be about England’s declining PISA science scores? Schools Week , 18 March, https://schoolsweek.co.uk/how-concerned-should-we-be-about-englands-declining-pisa-science-scores/ .

Jerrim, J., Lopez-Agudo, L.A. and Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O.D., 2022. The impact of test language on PISA scores. New evidence from Wales. British Educational Research Journal , 48(3), 420–45, https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3774 .

Jerrim, J. and Sibieta, L., 2021. A comparison of school institutions and policies across the UK, Education Policy Institute, https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/a-comparison-of-school-institutions-and-policies-across-the-uk/ .

Kelly, D.P., 2023. Retain external examination as the primary means of assessment. Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities blog, https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/cepeo/2023/06/22/retain-external-examination-as-the-primary-means-of-assessment/ .

Long, R. and Danechi, S., 2019. English Baccalaureate. House of Commons Library Briefing Paper 06045, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06045/SN06045.pdf .

Machin, S., McNally, S. and Viarengo, M., 2018. Changing how literacy is taught: evidence on synthetic phonics. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy , 10(2), 217–41, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20160514 .

Miles, J., 2023. Written statement: PISA 2022: National Report for Wales. Welsh Government, https://www.gov.wales/written-statement-pisa-2022-national-report-wales .

OECD, 2023. PISA 2022 Results: The State of Learning and Equity in Education . https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/53f23881-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/53f23881-en .

Paterson, L., 2023. PISA 2022 in Scotland: declining attainment and growing social inequality. Reform Scotland, https://reformscotland.com/2023/12/pisa-2022-in-scotland-declining-attainment-and-growing-social-inequality-lindsay-paterson/ .

Power, S., Newton, N. and Taylor, C., 2020. ‘Successful futures’ for all in Wales? The challenges of curriculum reform for addressing educational inequalities. The Curriculum Journal , 31(2), 317–33, https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.39 .

Psacharopoulos, G. and Patrinos, H.A., 2018. Returns to investment in education: a decennial review of the global literature. Education Economics , 26(5), 445–58, https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2018.1484426 .

Robson, J., Sibieta, L., Khandekar, S., Neagu, M., Robinson, D. and James Relly, S., 2024. Comparing policies, participation and inequalities across UK post-16 Education and Training landscapes. Education Policy Institute, https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/uk-nations-education-and-training/ .

Rose, J., 2006. Independent review of the teaching of early reading. Department for Education and Skills, https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/5551/2/report.pdf .

Sibieta, L., 2023. How does school spending per pupil differ across the UK? IFS Report R256, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/how-does-school-spending-pupil-differ-across-uk .

Sizmur, J., Ager, R., Bradshaw, J., Classick, R., Galvis, M., Packer, J., Thomas, D. and Wheater, R., 2019. Achievement of 15-year-olds in England: PISA 2018 results. Department for Education, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/904420/PISA_2018_England_national_report_accessible.pdf .

Wilson, D., Burgess, S. and Briggs, A., 2011. The dynamics of school attainment of England’s ethnic minorities. Journal of Population Economics , 24, 681–700, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0269-0 .

Wolf, A., 2011. Review of vocational education: the Wolf Report. Department for Education and Department for Business, Innovation & Skills, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-vocational-education-the-wolf-report .

Research Fellow

Luke is a Research Fellow at the IFS and his general research interests include education policy, political economy and poverty and inequality.

Report details

Suggested citation.

Sibieta, L. (2024). Major challenges for education in Wales . London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/major-challenges-education-wales (accessed: 25 October 2024).

More from IFS

Understand this issue.

Professor Sir Richard Blundell to give the Marshall Paley Lecture on inequalities

27 September 2024

Growth and cutting inequality must go hand in hand for Labour

23 July 2024

There are good reasons to reverse the two-child limit

22 July 2024

Policy analysis

Big budget cuts and salaries well below those in schools: England’s colleges continue to be neglected

This report sets out the financial state of colleges in England since 2010 and analyses the key future challenges they face.

24 October 2024

The effect of Sure Start on youth misbehaviour, crime and contacts with children’s social care

This report studies the impact of Sure Start, which supported families of under-5s, on children’s behaviour, youth offending and social care contacts.

23 October 2024

Pressures on public sector pay

Over a fifth of government spending goes on pay. We examine recruitment and retention challenges which mean that pressures could mount going forward.

Academic research

Education and inequality: an international perspective

20 September 2024

Health inequality and health types

We use k-means clustering, a machine learning technique, and Health and Retirement Study data to identify health types during middle and old age.

3 October 2024

Health shocks, health insurance, human capital, and the dynamics of earnings and health

We specify and calibrate a life-cycle model of labor supply and savings incorporating health shocks and medical treatment decisions.

21 October 2024

Education Wales

Q&a with simon pirotte – medr chief executive.

Darllenwch y dudalen hon yn Gymraeg

1. So what is Medr?

Medr is the new arms-length funder and regulator for tertiary education and research in Wales. We have oversight for further education, higher education, work-based learning and apprenticeships, adult education, research, and school sixth forms.

Wales the first place in the UK to have brought all those areas together in one place – we’re leading the way!

2. Why was Medr created?

Although Medr officially went ‘live’ on 1 August this year, the journey to get to this point began almost a decade ago, when the Welsh Government commissioned Professor Ellen Hazelkorn to undertake a review into the post-compulsory education and training system in Wales.

The review looked at gaps in provision across the tertiary sector and identified the need for better coherence and more joined-up thinking. It recommended the establishment of a new national body with responsibility for the regulation, oversight and co-ordination of the post-compulsory sector. We have explored systems with similar models (such as those in New Zealand and Norway), and we are confident that implementing this approach in Wales will lead to better strategic alignment across the tertiary sector.

The overarching goal is a system that delivers for learners and for Wales, and Medr has been created to enable that by facilitating clearer pathways for learners and encouraging collaborative working across the sector.

3. How are you making sure that learners’ interests are being represented? Will they have an opportunity to give their views about the education and training they receive?

One of the aims in our draft Strategic Plan (which we’re currently consulting on – you have until 25 October to get a response in!) is about focussing the sector around the needs of the learner and ensuring that they are involved in decision making. We recognise that giving learners the opportunity to share their views on their education and training is key to ensuring that the system delivers for them, and we are looking at how we can capture the learner voice across all parts of the sector.

We are currently in conversation with learners on our strategic direction, and we have a learner representative on our Board. At an institutional level, we are working to develop a learner engagement code for providers, which will ensure that learners are able to contribute to decision making that directly affects them.

4. What will you be doing to make sure post 16 learners with additional learning needs experience a quality education?

We want to ensure that learners find the best learning pathway for them – whatever and wherever that is. An important part of that is ensuring that barriers for learners with additional learning needs are removed whenever possible.

Alongside the work happening elsewhere in the sector, and in the Welsh Government, Medr has work to do to keep identifying and mitigating those barriers. Promoting equality of opportunity is one of our strategic duties as set out in legislation and a key focus for us in our draft Strategic Plan. I hope that responses to the consultation will identify ways we can improve our work around additional learning needs, and that by working in partnership with the sector we will continue to improve our understanding and support for learners with additional learning needs.

5. What does this change mean for school sixth forms?

On the face of it, there won’t be any significant immediate changes. School sixth forms will receive funding from Medr via their local authority, and Estyn will continue to have responsibility for quality and inspections.

Medr is taking over the Welsh Ministers’ existing powers in relation to sixth form organisation. We know that sixth forms are an integral part of the tertiary sector and a key part of the education journey for many learners. We want pathways to be clear, coherent, and impactful, so we are really glad that school sixth forms are in our remit, and we’re looking forward to working in partnership with the sector to ensure that provision across Wales is the best it can be.

6. What are your plans for making sure learners can carry on their post 16 education in the medium of Welsh?

We are working with the Coleg Cymraeg Cenedlaethol as the designated organisation under the Tertiary Education and Research Act to advise Medr on our statutory duty to promote and ensure sufficient provision of Welsh-medium tertiary education.

Our commitment to the Welsh language is reflected in our Strategic Plan; we will be developing a national plan for the Welsh language across the tertiary sector and working with Qualifications Wales and other stakeholders to ensure that there are routes available into Welsh-medium education and assessment.

7. What’s in your in box for this term?

Having launched on 1 August, we’re full of energy and are going full steam ahead this term! Our first Strategic Plan is a huge priority for us, and an important one to get right as we consider what we need to focus on over the next few years. We’ve worked hard to ensure that the draft Plan reflects the conversations we’ve had with our partners about the opportunities and challenges ahead, and we’re looking forward to gathering more views through the formal consultation.

As part of our consultation activity, we are engaging with learners and employers to gather their views in preparation for submission of a final draft of the Plan to Welsh Ministers in December.

8. When and how will we start to see the impact Medr is making?

Without getting ahead of ourselves, I think we’re already starting to see it in the way organisations and providers are thinking. We’ve been talking about this for a long time now – it’s been eight years since the Hazelkorn review into our tertiary system. In the conversations we’ve been having with the sector, we’ve heard people’s concerns about the challenges ahead, but we’ve also sensed real optimism about the possibilities for the future.

It may be a while before we start to see tangible impacts of Medr’s work. Our strategic duties are ambitious and we’ll be working hard to deliver them, but we don’t expect to see changes immediately. In our Strategic Plan we’ve outlined our founding commitments, which we hope to achieve in the next two years, and our growth commitments, to be achieved by the end of the Plan’s life in 2030.

From my point of view, one of the key measures of our impact will be conversations with learners to hear their reflections on their educational journey, and whether our system has equipped them with the skills and knowledge they need to lead a fulfilling life – whatever that looks like.

Find out more about Medr. Have your say on our Strategic Plan

The Seren Academy

The Seren Academy is a fully funded programme from the Welsh Government which supports the aspirations and ambitions of our most able learners, helping to widen their horizons, develop a passion for their chosen field of study, and reach their academic potential.

It is available to years 8 to 13 learners from state schools and further education colleges across Wales who have been identified by their institution as meeting the eligibility criteria.

Being part of the Seren Academy offers our most able learners’ opportunities to immerse themselves in an established super curricular experience to:

- ignite their curiosity and motivation for their learning

- empower them to make ambitious, informed choices about their future educational pathway and

- advance their ability to reach their potential and succeed at highly selective universities.

In the last academic year, the Seren Academy has supported approximately 23,000 Seren learners from across Wales, and, thanks to collaboration with schools and colleges the programme has evolved.

Eligibility criteria

More flexibility has enabled teaching leads to identify learners for the academy in Y8 and Y9.

New programme pack

You can access the Stage One teacher Programme pack by registering on Seren Space

A resource to help teachers break down barriers to participation so that learners from disadvantaged backgrounds can participate in the academy during the school day.

Seren Space

An online platform, for year 10 to 13 learners. Teachers can also register to be part of the Seren Teacher’s community where they can access resources and communications.

Building relationships with Universities

Seren can now offer a Cambridge University residential and Cardiff University dental residential as part of the suite of six residential experiences for year 12, and there is now a new Exeter University reduced offer for Seren graduates.

Universities in Wales

Building on our established partnerships with Universities in Wales , five “Uni Intensive” days were held across Wales for Y10.

Swansea University’s leadership for future generations events

This year 280 Seren learners participated with the former US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, her husband, former US President Bill Clinton and former First Minister Mark Drakeford.

Debating competition

The first national year 9 Seren debating competition was held with 16 schools from across Wales participating in the final at Jesus College, Oxford. Make sure your school/s are entering this year! Your hub coordinator will be organising the interschool competitions in your area.

Super-curricular toolkit

A super-curricular toolkit was created in collaboration with Oxplore , containing classroom guides, resources and worksheets for teachers to challenge learners with debates and ideas that go beyond what is covered in the classroom.

Axiom Maths

40 schools are now partnered with Axiom Maths to deliver an additional super-curricular maths programme to Y8 Seren learners from September 2024. Following a teacher-led maths challenge pilot in Pembrokeshire, we are launching a national maths challenge for all Seren schools to take part this year.

Don’t miss your opportunity to apply for Taith Pathway 2 funding

Taith is Wales’ international learning exchange programme, creating life-changing opportunities to learn, study and volunteer all over the world. On 3 October Taith opens its next call for funding applications – this will be a ‘Pathway 2’ funding call.

What is Pathway 2?

Pathway 2 funding is available to any non-profit educational or training organisation based in Wales who is looking to fund an international collaborative project. Organisations within the schools, youth, adult education and further education/vocational education and training sectors are able to apply.

To qualify for funding a project must support educational innovation and address a specific issue or sector priority in Wales.

Pathway 2 projects offer staff and learners with opportunities to enhance their understanding, knowledge and application of a key theme or topic whilst developing a project output from their learning in collaboration with international partners.

Project Output

Whilst visiting an international partner, known as a mobility, is a component of Pathway 2 projects, the primary focus of these projects is not the personal benefits to individual participants. Rather, international mobilities are intended to facilitate the development and successful completion of project deliverables which addresses a specific issue or sector priority in Wales. Pathway 2 projects are all about creating and sharing results that bring lasting benefits – not just for the organisations involved, but also for the applicant’s sector, as well as for Wales and the international partner countries.

To qualify for Pathway 2 funding your organisations’ projects must align with at least one of the identified Taith themes. For Pathway 2 2024 the themes are ‘Developments in Education’, ‘Diversity and Inclusion’ and ‘Sustainability and Climate Change’. It is worth noting that Taith themes are set annually so you may see them change in future years.

Taith is dedicated to making international exchange more inclusive and accessible for everyone. Its strategy focuses on helping people who have been underrepresented in international exchange – such as those from disadvantaged or ethnic minority backgrounds, Disabled individuals, and people with additional learning needs – gain access to these valuable opportunities.

Looking for inspiration?

- Pencoed Primary School, joined together with two other schools, Ysgol Y Gogarth and Ysgol Pen Rhos to apply for Taith Pathway 2 funding to support the development and sustainability of community focused schools in Wales.

- Plan International UK applied for funding to deliver a virtual project which will empower Welsh youth sector professionals to create supportive environments for essential discussions, address sensitive topics, and help young people. It will provide resources to challenge attitudes and behaviours that contribute to Gender-Based Violence.

- Disability Sport Wales will create two resources to help people identify available para sports pathways and understand the impairment profiles and requirements of National Governing Bodies when recruiting athletes.

- Cardiff and Vale College will develop an innovative resource to boost employment rates for individuals with ALN by helping employers and support networks provide meaningful, sustainable opportunities for neurodiverse people.

- ColegauCymru/CollegesWales will address issues from Estyn’s June 2023 report on peer-on-peer sexual harassment among 16-18-year-olds in further education. The project will focus on preventing misogynistic attitudes and cultures in FE learners and developing a transnational Community of Practice.

- In line with Taith and the Welsh Government’s equality objectives, particularly the vision for an anti-racist Wales, Diverse Cymru applied for funding to develop inclusive, community-led resources. These resources aim to address the acknowledged inequities faced by minority ethnic communities in the adult education sector across Wales.

Taith’s website makes it easy to filter project summaries . Use the left-hand column to filter by Pathway, and click the magnifying glass icon next to the Organisation Name to view brief summaries of projects funded in previous calls.

Get ready to apply

Timelines for applications

- 3rd October 2024: Opening of Pathway 2 (2024) funding call.

- 21st November 2024, 12pm: Application deadline.

- March 2025: Outcome notifications will be sent to all applying organisations.

- 1st May 2025: Projects can commence.

Want to know more? Why not sign up to one of Taith’s webinars?

In these webinars Taith will provide an overview of Pathway 2 2024 funding call and share details of the eligibility criteria, eligible activities and costs as well as providing guidance on how to prepare for your application.

This will also be a great opportunity for organisations to raise any questions with the Taith team.

8th October 12.00-13.30 English session

8th October 16:00-17:30 Welsh session

22 nd October 12:00-13:30 Welsh session

22 nd October 16:00-17:30 English session

To learn more about Taith and the funding available visit www.Taith.wales

Message from the Cabinet Secretary for Education, Lynne Neagle

With the new school year in full swing, the Cabinet Secretary for Education has outlined her priorities and how children and young people will remain at the heart of education policy. She also welcomes Vikki Howells, the new Minister for Further & Higher Education to the Education Wales team.

Education Secretary, Lynne Neagle said:

“In my six months as Cabinet Secretary for Education I have been privileged to see the excellent work done in our schools and colleges. It is clear we all share the same priority, in always putting the interests of children and young people first in our decisions.

I’m very much looking forward to working with you all again this term, as I renew my focus on raising standards and attainment, continuing to improve attendance and ensuring the wellbeing of all learners.

Listening and talking to you is something I have really valued, in ministerial roundtables, on visits and at events. Last term this helped me in my decision not to press ahead with changing school term dates, providing additional support for the curriculum and ongoing work to simplify ALN implementation. And the value we place upon our public servants and your commitment to improving the lives of our learners is reflected in the Government’s decision to award above inflation pay rises.

The First Minister has set out her priorities for the remainder of the Government following a listening exercise during the Summer, with improving standards in schools and colleges high up the agenda.

Later this term I will set out clear priorities aimed at improving standards for all learners. This will focus on demonstrable improvements in literacy, and numeracy with well-being and equity at the forefront.

We are supporting schools to adopt innovative approaches to teaching numeracy and literacy and putting our literacy and numeracy framework on a statutory footing. This is alongside our Mathematics Support Programme which provides comprehensive teaching resources and activities for all learners.

Phase two of our Attainment Champions pilot, begins this month and will see more partner schools recruited to the scheme which shares innovative practices to improve the educational experiences for learners facing disadvantage.

I know there is a strong link between school attendance and attainment, our reforms can only succeed if children are in school.

We have seen an improvement in attendance, and there is plenty of good practice happening in schools. However, I know there is more we can do, and I will be making sure efforts are targeted towards the groups of pupils who we know are most likely to be not attending school, those from lower income families, secondary age children and pupils in key exam years.

This month marks the start of the final year of the initial implementation of the ALN system. I have witnessed incredible progress and commitment from the education workforce, and wonderful examples of schools, children and families putting the needs of every child first. There have been more than 10,000 statutory Individual Development Plans (IDPs) agreed in the past 12 months, an incredible testament to our workforce.

However, I know from what you and parents are telling me that we also face challenges in implementing ALN reform, which is why I have taken action, including commissioning an examination of the legislative framework to ensure it is delivering for learners.

I recognise the financial challenges many families face. This is why we have several schemes in place such as the School Essentials Grant to help low-income families buy uniform and sports kits. We are the only nation in the UK to offer all state primary schools a free school meal to children, which help learning and makes sure they have a nutritional meal. We all know a healthy school meal can help with learner concentration and wellbeing enabling them to achieve their full potential, which is why during this school year we will review the nutritional content of school meals.

I’m delighted to be joined by a new Minister for Further and Higher Education, Vikki Howells. Her appointment is part of the new Cabinet announced by the First Minister. The new team offers stability, draws on experience, and brings our collective talents together.

Alongside the Minister for Further and Higher Education, I look forward to working with Medr , the new commission for tertiary education and research which is now operational, over the next year on how we can improve post statutory education strategic planning, including increasing the numbers of learners in post 16 education.

I want to thank all of you for your continued hard work and commitment as we work together to ensure all learners are supported to achieve their full potential.”

Pupil Development Grant – don’t miss out!

The Pupil Development Grant (PDG) is a key enabler for tackling the impact of poverty on educational attainment and ensuring our national mission of high standards and aspirations for all.

Welsh Government guidance recommends schools and settings focus their spend on eight key areas which are of most benefit to children from low-income households.

Estyn highlight that effective schools reduce the impact of poverty by focusing on:

- ensuring all pupils, especially those experiencing poverty, have access to the very best learning and teaching, and by

- building relationships with ‘parents, the local community and specialist services to meet the needs of pupils and their families’ – the key tenets of Community Focused Schools .

Case studies

New video case studies show how PDG is being used to best support children and young people across Wales. The schools include Ysgol Plasmawr, Ysgol Borthyn, Ysgol Nant Caerau, Awel y Môr Primary School, Bridgend College, Craigfelen Primary School, Idris Davies School, Llandeilo Primary School and Parc Primary School.

From supporting high quality learning and teaching to engaging with families and raising aspirations, education practitioners in early years, primary and secondary schools and settings share how they plan and spend PDG to support the progression and wellbeing of learners impacted by poverty.

David Williams, headteacher of Parc Primary School in Treorchy, said:

“We’ve got around 65% of our children who are classed as vulnerable, so the PDG has really transformed how we support our vulnerable families and our low-income families. What it allows us to do is ensure there is equity for all our stakeholders; the pupils, the parents and carers of the school, the wider community.

“We’re very passionate and proud here about the opportunities we give the children and the parents. The children engage in a wide range of activities. They’re learning about the fire triangle, they’re growing and cultivating their own crops, they’re looking at the weather. There is plenty of evidence already of the impact.”

EEF Toolkits

The EEF Toolkits are another free to access resource for schools providing a evidence-based source of methods to improve learning for disadvantaged pupils.

Spread the word

When parents and carers register as eligible for free school meals with their Local Authority, this unlocks access to the School Essentials Grant. It also means schools get more funding.

With the introduction of free school meals for primary pupils, many parents and carers do not realise that schools will lose out unless they continue to register as eligible.

So spread the word by sharing: https://www.gov.wales/get-help-school-costs

Even if they don’t need the grant, registering as eligible will mean schools get additional funding.

14 to 16 Learning under the Curriculum for Wales

Following consultation earlier this year, statutory guidance on 14 to 16 Learning under Curriculum for Wales (CfW) has been published today.

This complements the publication of the first wave of reformed GCSE exam specifications from WJEC later this month and aims to support schools to plan and design their curriculum for the first cohort of year 10 learners under CfW from September 2025.

What’s next? From September 2025 the curriculum offer for 14 to 16 year olds should be organised around the four components of the 14 to 16 Learner Entitlement alongside qualifications during years 10 and 11.

What will be required of schools/practitioners?

To design a 14 to 16 curriculum offer that:

- ensures everything a learner experiences is in pursuit of the four purposes.

- includes an appropriate mix of general, vocational and skill-based qualifications at different levels, based on the needs of their learners, with all learners benefitting from challenging, stretching and ambitious qualifications in English, Welsh, Mathematics and the Sciences.

- provides dedicated curriculum time to support their learners to understand their strengths, and to plan for their next steps post 16.

- ensures all their year 10 and 11 learners continue to learn across all Areas and mandatory elements of the curriculum, and that they make progress in all four components of the Learner Entitlement.

As schools plan for September 2025, we will provide resources to support practitioners and senior leaders in designing their curriculum offer in line with the guidance. This will include process maps for curriculum design along with good practice case studies focusing on learner effectiveness. These supporting materials will be published throughout the Autumn term with the first available later this month alongside the publication of WJEC’s Made for Wales GCSE specifications.

We are also developing a targeted package of professional learning for senior leaders to support them as new qualifications and the Learner Entitlement are introduced from September 2025. This will complement the work of Welsh Government curriculum colleagues on curriculum design, progression and assessment, whilst supplementing WJEC’s professional learning schedule for the Made-for-Wales GCSEs. Full details of the package of professional learning will be publicised in Dysg by the end of September.

Written Statement: Publication of Curriculum for Wales 14 to 16 Learning Guidance (18 September 2024)

Teacher Pay Recommendations

Please read this statement published today from the Cabinet Secretary for Education Lynne Neagle.

It covers recommendations for amendments to teachers’ pay and conditions from September 2024.

14 to 16 Learning in the Curriculum for Wales: an update

From September 2026, all learners aged 3-16 will be following the Curriculum for Wales. The aspiration of the curriculum is that all learners leave education at 16 with the knowledge, skills and understanding they need to succeed as they move to the next stage of their education, training or employment.

Following on from the consultation earlier this year, statutory guidance will be published in September setting out the legal requirements and the Welsh Government’s policy expectations for a school’s curriculum for 14 to 16-year-old learners under the Curriculum for Wales.

The guidance will be accompanied by detail of a package of professional learning and resources to support schools in designing, implementing, and reviewing their curriculum for years 10 and 11.

This will include good practice case studies, professional learning on learner effectiveness and targeted support on curriculum design.

The new GCSEs Qualifications Wales has reformed GCSE qualifications in Wales to reflect what learners are being taught as part of the new curriculum.

Reformed GCSEs are being introduced in a phased approach, with the first wave being taught in schools from September 2025.

Schools will have a full academic year to prepare for teaching of this first wave of new GCSEs following the publication of final qualification specifications in September 2024 ( draft specifications are already available).

With support from Adnodd and Welsh Government, WJEC will offer a package of teaching resources and professional learning opportunities to support schools and practitioners to deliver these new qualifications.

Other National 14-16 Qualifications

It’s not just GCSEs which are being updated to reflect the new curriculum.

Qualifications Wales has also consulted on, and is now taking forward the development of, a wider set of 14-16 qualifications in Wales.

These will comprise the exciting new VCSE qualification, Foundation Qualifications and the Skills Suite (encompassing Skills for Life, Skills for Work and the Personal Project).

These qualifications will be available for teaching in school from September 2027.

Adnodd, Qualifications Wales and Welsh Government will work with awarding bodies to ensure that bilingual teaching and learning resources will be available to support the delivery of these new national qualifications.

Keep Informed

Qualifications Wales has a dedicated hub for the reformed National 14 to 16 Qualifications where you can stay up-to-speed with the latest announcements, access resources and ask questions.

School essentials – support for families

The School Essentials Grant scheme for 2024-25 opened on 1 July.

Up to £200 is available for children whose families are on lower incomes for school uniform and other essentials, in all year groups from reception to year 11.

In order to make sure all eligible families apply, we have made it easy for schools to share information with parents on how to apply for the grants available.

Even if learners are receiving Universal Primary Free School Meals, it is important to still check eligibility to access the School Essentials Grant and extra funding for schools.

A leaflet in 19 languages is available here , along with resources and advice for schools on how to share information.

School uniform schemes – case studies

As well as the school essentials grant there are excellent initiatives taking place in schools across Wales to support families in keeping school uniform costs down. Case studies from Children in Wales highlight some of these schemes.

For example at Blaenhonddan Primary in Neath Port Talbot, ‘Eco Warriors’ pupils have helped to set up a recycling scheme providing families with school uniform free of charge.