We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 5: 10 Real Cases on Acute Heart Failure Syndrome: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Swathi Roy; Gayathri Kamalakkannan

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Diagnosis and Management of New-Onset Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

A 54-year-old woman presented to the telemetry floor with shortness of breath (SOB) for 4 months that progressed to an extent that she was unable to perform daily activities. She also used 3 pillows to sleep and often woke up from sleep due to difficulty catching her breath. Her medical history included hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and history of triple bypass surgery 4 years ago. Her current home medications included aspirin, atorvastatin, amlodipine, and metformin. No significant social or family history was noted. Her vital signs were stable. Physical examination showed bilateral diffuse crackles in lungs, elevated jugular venous pressure, and 2+ pitting lower extremity edema. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with left ventricular hypertrophy. Chest x-ray showed vascular congestion. Laboratory results showed a pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP) level of 874 pg/mL and troponin level of 0.22 ng/mL. Thyroid panel was normal. An echocardiogram demonstrated systolic dysfunction, mild mitral regurgitation, a dilated left atrium, and an ejection fraction (EF) of 33%. How would you manage this case?

In this case, a patient with known history of coronary artery disease presented with worsening of shortness of breath with lower extremity edema and jugular venous distension along with crackles in the lung. The sign and symptoms along with labs and imaging findings point to diagnosis of heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF). She should be treated with diuretics and guideline-directed medical therapy for congestive heart failure (CHF). Telemetry monitoring for arrythmia should be performed, especially with structural heart disease. Electrolyte and urine output monitoring should be continued.

In the initial evaluation of patients who present with signs and symptoms of heart failure, pro-BNP level measurement may be used as both a diagnostic and prognostic tool. Based on left ventricular EF (LVEF), heart failure is classified into heart failure with preserved EF (HFpEF) if LVEF is >50%, HFrEF if LVEF is <40%, and heart failure with mid-range EF (HFmEF) if LVEF is 40% to 50%. All patients with symptomatic heart failure should be started on an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (or angiotensin receptor blocker if ACE inhibitor is not tolerated) and β-blocker, as appropriate. In addition, in patients with New York Heart Association functional classes II through IV, an aldosterone antagonist should be prescribed. In African American patients, hydralazine and nitrates should be added. Recent recommendations also recommend starting an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) in patients who are symptomatic on ACE inhibitors.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Search Menu

- Author videos

- ESC Content Collections

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About European Heart Journal Supplements

- About the European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, case presentation.

- < Previous

Clinical case: heart failure and ischaemic heart disease

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Giuseppe M C Rosano, Clinical case: heart failure and ischaemic heart disease, European Heart Journal Supplements , Volume 21, Issue Supplement_C, April 2019, Pages C42–C44, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/suz046

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Patients with ischaemic heart disease that develop heart failure should be treated as per appropriate European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association (ESC/HFA) guidelines.

Glucose control in diabetic patients with heart failure should be more lenient that in patients without cardiovascular disease.

Optimization of cardiac metabolism and control of heart rate should be a priority for the treatment of angina in patients with heart failure of ischaemic origin.

This clinical case refers to an 83-year-old man with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and shows that implementation of appropriate medical therapy according to the European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association (ESC/HFA) guidelines improves symptoms and quality of life. 1 The case also illustrates that optimization of glucose metabolism with a more lenient glucose control was most probably important in improving the overall clinical status and functional capacity.

The patient has family history of coronary artery disease as his brother had suffered an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) at the age of 64 and his sister had received coronary artery by-pass. He also has a 14-year diagnosis of arterial hypertension, and he is diabetic on oral glucose-lowering agents since 12 years. He smokes 30 cigarettes per day since childhood.

In February 2009, after 2 weeks of angina for moderate efforts, he suffered an acute anterior myocardial infarction. He presented late (after 14 h since symptom onset) at the hospital where he had been treated conservatively and had been discharged on medical therapy: Atenolol 50 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg tds, Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50, and Fluticasone 500 mg oral inhalers.

Four weeks after discharge, he underwent a planned electrocardiogram (ECG) stress test that documented silent effort-induced ST-segment depression (1.5 mm in V4–V6) at 50 W.

He underwent a coronary angiography (June 2009) and left ventriculography that showed a not dilated left ventricle with apical dyskinesia, normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, 52%); occlusion of proximal LAD, 60% stenosis of circumflex (CX), and 60% stenosis of distal right coronary artery (RCA). An attempt to cross the occluded left anterior descending (LAD) was unsuccessful.

He was therefore discharged on medical therapy with: Atenolol 50 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Perindopril 4 mg o.d., oral isosorbide mono-nitrate (ISMN) 60 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., metformin 850 mg tds, Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg, and Fluticasone 500 mcg b.i.d. oral inhalers.

He had been well for a few months but in March 2010 he started to complain of retrosternal constriction associated to dyspnoea for moderate efforts (New York Heart Association (NYHA) II–III, Canadian Class II).

For this reason, he was prescribed a second coronary angiography that showed progression of atherosclerosis with 80% stenosis on the circumflex (after the I obtuse marginal branch) and distal RCA. The LAD was still occluded.

After consultation with the heart team, CABG was avoided because surgical the risk was deemed too high and the patient underwent palliative percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of CX and RCA. It was again attempted to cross the occlusion on the LAD. But this attempt was, again, unsuccessful. Collateral circulation from posterior interventricular artery (PDL) to the LAD was found. The pre-PCI echocardiogram documented moderate left ventricular dysfunction (EF 38%), the pre-discharge echocardiogram documented a LVEF of 34%. Because of the reduced LVEF, atenolol was changed for Bisoprolol (5 mg o.d.).

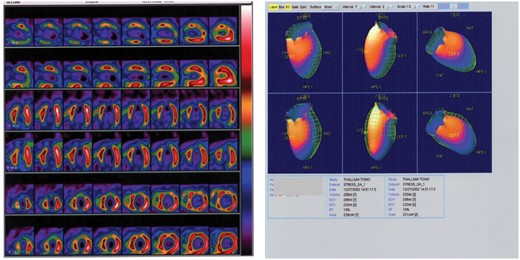

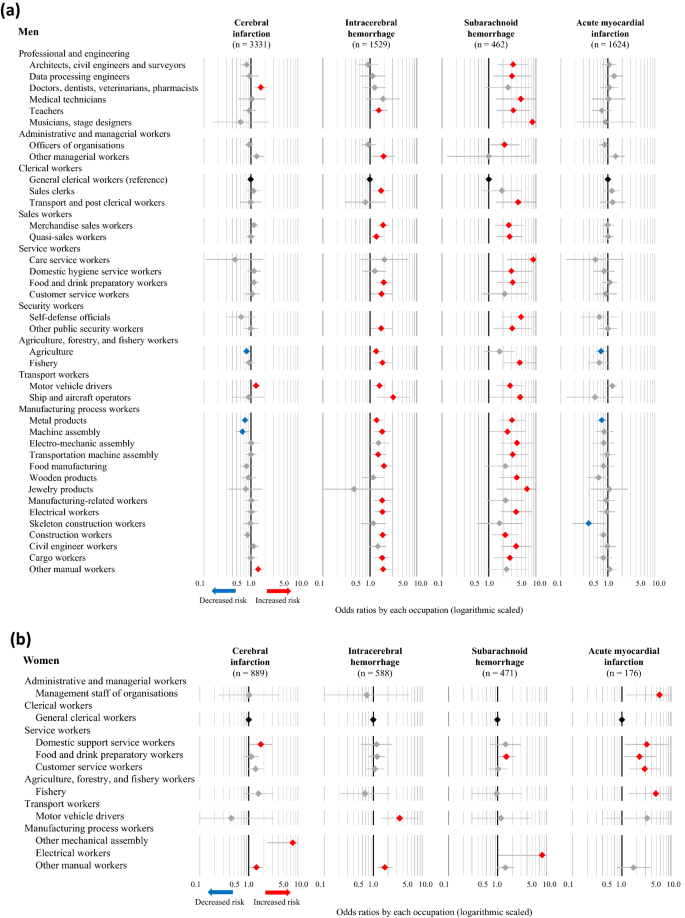

At follow-up visit in December 2012, the clinical status and the haemodynamic conditions had deteriorated. He complained of worsening effort-induced dyspnoea/angina that now occurred for less than a flight of stairs (NYHA III). On clinical examination clear signs of worsening heart failure were detected ( Table 1 ). His medical therapy was modified to: Bisoprolol 5 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Perindopil 5 mg o.d., ISMN 60 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg tds, Furosemide 50 mg o.d., Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg oral inhaler, and Fluticasone 500 mcg oral inhaler. A stress perfusion cardiac scintigraphy was requested and revealed dilated ventricles with LVEF 19%, fixed apical perfusion defect and reversible perfusion defect of the antero-septal wall (ischaemic burden <10%, Figure 1 ). He was admitted, and an ICD was implanted.

Clinical parameters during follow-up visits

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy and left ventriculography showing dilated left ventricle with left ventricular ejection fraction 19%. Reversible perfusion defects on the antero-septal wall and fixed apical perfusion defect.

In March 2013, he felt slightly better but still complained of effort-induced dyspnoea/angina (NYHA III, Table 1 ). Medical therapy was updated with bisoprolol changed with Nebivolol 5 mg o.d. and perindopril changed to Enalapril 10 mg b.i.d. The switch from bisoprolol to nebivolol was undertaken because of the better tolerability and outcome data with nebivolol in elderly patients with heart failure. Perindopril was switched to enalapril because the first one has no indication for the treatment of heart failure.

In September 2013, the clinical conditions were unchanged, he still complained of effort-induced dyspnoea/angina (NYHA III) and did not notice any change in his exercise capacity. His BNP was 1670. He was referred for a 3-month cycle of cardiac rehabilitation during which his medical therapy was changed to: Nebivolol 5 mg o.d., Ivabradine 5 mg b.i.d., uptitrated in October to 7.5 b.i.d., Trimetazidine 20 mg tds, Furosemide 50 mg, Metolazone 5 mg o.d., K-canrenoate 50 mg, Enalapril 10 mg b.i.d., Clopidogrel 75 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 40 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg b.i.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg oral inhaler, and Fluticasone 500 mcg oral inhaler.

At the follow-up visit in January 2014, he felt much better and had symptomatically, he no longer complained of angina, nor dyspnoea (NYHA Class II, Table 1 ). Trimetazidine was added because of its benefits in heart failure patients of ischaemic origin and because of its effect on functional capacity. Ivabradine was added to reduce heart rate since it was felt that increasing nebivolol, that was already titrated to an effective dose, would have had led to hypotension.

He missed his follow-up visits in June and October 2014 because he was feeling well and he had decided to spend some time at his house in the south of Italy. In January and June 2015, he was well, asymptomatic (NYHA I–II) and able to attend his daily activities. He did not complain of angina nor dyspnoea and reported no limitations in his daily activities. Unfortunately, in November 2015 he was hit by a moped while on the zebra crossing in Rome and he later died in hospital as a consequence of the trauma.

This case highlights the need of optimizing both the heart failure and the anti-anginal medications in patients with heart failure of ischaemic origin. This patient has improved dramatically after the up-titration of diuretics, the control of heart rate with nebivolol and ivabradine and the additional use of trimetazidine. 1–3 All these drugs have contributed to improve the clinical status together with a more lenient control of glucose metabolism. 4 This is another crucial point to take into account in diabetic patients, especially if elderly, with heart failure in whom aggressive glucose control is detrimental for their functional capacity and long-term prognosis. 5

IRCCS San Raffaele - Ricerca corrente Ministero della Salute 2018.

Conflict of interest : none declared. The authors didn’t receive any financial support in terms of honorarium by Servier for the supplement articles.

Ponikowski P , Voors AA , Anker SD , Bueno H , Cleland JG , Coats AJ , Falk V , González-Juanatey JR , Harjola VP , Jankowska EA , Jessup M , Linde C , Nihoyannopoulos P , Parissis JT , Pieske B , Riley JP , Rosano GM , Ruilope LM , Ruschitzka F , Rutten FH , van der Meer P ; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the Special Contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC . Eur J Heart Fail 2016 ; 18 : 891 – 975 .

Google Scholar

Rosano GM , Vitale C. Metabolic modulation of cardiac metabolism in heart failure . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 99 – 103 .

Vitale C , Ilaria S , Rosano GM. Pharmacological interventions effective in improving exercise capacity in heart failure . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 1 – 27 .

Seferović PM , Petrie MC , Filippatos GS , Anker SD , Rosano G , Bauersachs J , Paulus WJ , Komajda M , Cosentino F , de Boer RA , Farmakis D , Doehner W , Lambrinou E , Lopatin Y , Piepoli MF , Theodorakis MJ , Wiggers H , Lekakis J , Mebazaa A , Mamas MA , Tschöpe C , Hoes AW , Seferović JP , Logue J , McDonagh T , Riley JP , Milinković I , Polovina M , van Veldhuisen DJ , Lainscak M , Maggioni AP , Ruschitzka F , McMurray JJV. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology . Eur J Heart Fail 2018 ; 20 : 853 – 872 .

Vitale C , Spoletini I , Rosano GM. Frailty in heart failure: implications for management . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 104 – 106 .

- myocardial ischemia

- cardiac rehabilitation

- heart failure

- older adult

Email alerts

More on this topic, related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1554-2815

- Print ISSN 1520-765X

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 09 February 2021

Clinical judgement in chest pain: a case report

- Mishita Goel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1540-2910 1 ,

- Shubhkarman Dhillon 1 ,

- Sarwan Kumar 1 &

- Vesna Tegeltija 1

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 15 , Article number: 49 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3878 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Cardiac stress testing is a validated diagnostic tool to assess symptomatic patients with intermediate pretest probability of coronary artery disease (CAD). However, in some cases, the cardiac stress test may provide inconclusive results and the decision for further workup typically depends on the clinical judgement of the physician. These decisions can greatly affect patient outcomes.

Case presentation

We present an interesting case of a 54-year-old Caucasian male with history of tobacco use and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who presented with atypical chest pain. He had an asymptomatic electrocardiogram (EKG) stress test with intermediate probability of ischemia. Further workup with coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) and cardiac catheterization revealed multivessel CAD requiring a bypass surgery. In this case, the patient only had a history of tobacco use but no other significant comorbidities. He was clinically stable during his hospital stay and his testing was anticipated to be negative. However to complete workup, cardiology recommended anatomical testing with CCTA given the indeterminate EKG stress test results but the results of significant stenosis were surprising with the patient eventually requiring coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

As a result of the availability of multiple noninvasive diagnostic tests with almost similar sensitivities for CAD, physicians often face this dilemma of choosing the right test for optimal evaluation of chest pain in patients with intermediate pretest probability of CAD. Optimal test selection requires an individualized patient approach. Our experience with this case emphasizes the role of history taking, clinical judgement, and the risk/benefit ratio in deciding further workup when faced with inconclusive stress test results. Physicians should have a lower threshold for further workup of patients with inconclusive or even negative stress test results because of the diagnostic limitations of the test. Instead, utilizing a different, anatomical test may be more valuable. Specifically, the case established the usefulness of CCTA in cases such as this where other CAD diagnostic testing is indeterminate.

Peer Review reports

Heart disease is one of the most commonly encountered medical conditions in the world. Individuals seeking medical help because of chest pain frequently require further testing for heart disease. Cardiac stress testing is a validated diagnostic tool commonly used to assess symptomatic patients with intermediate pretest probability of coronary artery disease (CAD). Baseline electrocardiogram (EKG) findings and ability to exercise are important factors to determine the most appropriate cardiac stress test. Exercise EKG stress test is preferred in patients who have normal baseline EKGs and are able to exercise. Patients found to have positive test results with chest pain usually undergo cardiac catheterization, while those with negative test results are usually considered to have non-cardiac chest pain. In some cases, the cardiac stress test may provide inconclusive results. The decision for further workup typically depends on the clinical judgement of the physician and the results may greatly affect patient outcomes. We present an interesting case of a healthy man who presented with chest pain and had an inconclusive EKG stress test, but further workup was performed and revealed multivessel CAD requiring a bypass surgery.

A 54-year-old, overweight (BMI 29), Caucasian man with a history of tobacco smoking and gastroesophageal reflux presented to the emergency department with chest pain. He described it as sudden in onset, while he was working on his laptop. Location was substernal, radiating to his left arm and jaw. Initially, the pain was 7/10 in intensity but it improved spontaneously even before he reached the hospital or received any medications. On further probing, he reported that he had experienced intermittent episodes of chest pain for the last 3 weeks but it was mostly exertional and was relieved with rest. The pain was not associated with shortness of breath, diaphoresis, or nausea/vomiting. He denied any fever, chills, cough, abdominal pain, urinary or bowel complaints. He did not have any family history of significant cardiac events.

On presentation, the patient was hemodynamically stable with a blood pressure of 139/85 mmHg and heart rate of 81 beats per minute. His EKG did not show any ischemic changes, no left ventricular hypertrophy, or left bundle branch block. Three sets of serial troponin enzyme were less than 0.010. Lipid panel showed total cholesterol of 235, triglycerides 408, HDL 26, and LDL could not be calculated. His pretest probability of CAD was intermediate on the basis of age and sex. Since the patient was chest pain free since admission and was able to exercise, an exercise treadmill EKG stress test was ordered. The patient achieved 95% of maximum predicted heart rate and 10 METs of exercise with normalization of slight T wave inversions that were seen in leads V2, V3, and V4 at rest. Thus, it was read as maximum asymptomatic stress test with intermediate probability of ischemia. Echocardiogram was obtained which showed normal left ventricular function and no significant valvular or wall motion abnormalities. At this point, cardiology was consulted to evaluate the patient and they recommended coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) for further risk stratification.

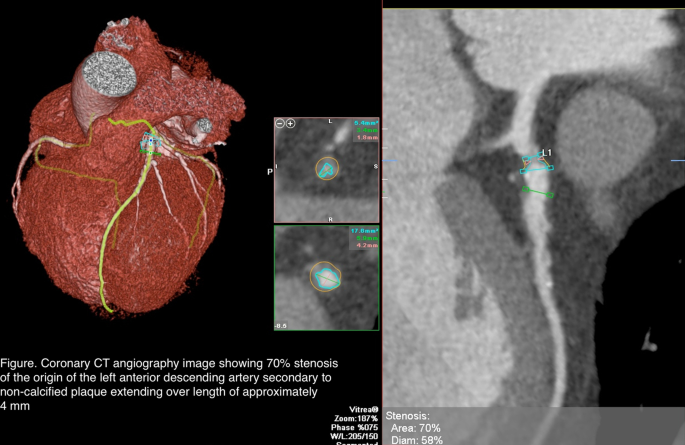

Diagnosis and management

CCTA results showed approximate 70% stenosis of the origin of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) secondary to noncalcified plaque extending over a length of approximately 4 mm (Fig. 1 ), approximate 40–50% stenosis of the proximal ramus intermedius branch secondary to mixed calcified and noncalcified plaque and scattered calcified and noncalcified plaque along the circumflex and obtuse marginal branches with 30–40% luminal diameter stenosis. Fractional flow reserve–computed tomography (FFR-CT) revealed a high likelihood of flow-limiting stenosis with a value of less than 0.5 secondary to the significant stenosis at the origin of the LAD and a low likelihood of flow-limiting stenosis in the left circumflex, ramus intermedius, and right coronary arteries.

Coronary computed tomography angiography image showing 70% stenosis of the origin of the left anterior descending artery to secondary to non-calcified plaque extending over a length of approximately 4 mm

The patient was then taken for cardiac catheterization which showed a 95% stenotic lesion of LAD with partial perfusion (TIMI grade 2 flow) giving rise to diagonal 1, which has an ostial and proximal 70% stenosis; ramus intermedius with proximal 70% segmental stenosis; circumflex, nondominant vessel, which has mild disease in proximal distal segments, giving rise to obtuse marginal 1, which has proximal 70% stenosis. Cardiothoracic surgery was consulted and the patient underwent bypass graft surgery.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient did well after the surgery. He stayed in the hospital for 4 days post-op without any complaints and was discharged home in stable condition. A referral to home care was made to provide for monitoring of the patient's progress and detection of any complications during the immediate post-op period. Cardiac rehabilitation referral was also provided and the patient was instructed to follow up with a cardiologist and cardiothoracic surgeon.

Cardiac stress testing is usually performed for diagnosis of CAD in patients with intermediate pretest probability of CAD. Appropriate history, physical examination, and baseline EKG findings are crucial in determining the most appropriate and cost-effective stress test for these patients. According to the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, exercise stress EKG is recommended as an initial diagnostic test among patients at intermediate pretest risk who are able to exercise and who have an interpretable resting EKG [ 1 ]. In the presence of baseline EKG abnormalities, including ST depression greater than 1 mm, left ventricular hypertrophy, left bundle branch block, paced rhythm or pre-excitation, functional tests with imaging or anatomical tests including CCTA are preferred. Studies have shown that exercise EKG test is adequate for risk stratification of cardiac events which are found to be very low in patients with a negative EKG stress test [ 2 ].

Our case describes a commonly encountered scenario of a patient with few risk factors for CAD who presented to the hospital with chest pain and requires further diagnostic testing for CAD. Treadmill EKG is one of the most utilized CAD testing methods in our practice and the results guide further management of patients presenting with chest pain. A meta-analysis including 22 years of research revealed the pooled sensitivity of EKG stress test in detecting CAD to be 68% and specificity to be 77% [ 1 ]. Despite this, EKG stress tests continue to be one of the most commonly used and trusted tools in our clinical practice.

A cohort study comparing usefulness of dipyridamole echocardiography, dobutamine-atropine echocardiography, and exercise stress testing revealed similar sensitivity for diagnosis of CAD in patients presenting with chest pain [ 3 ]. In fact even in cases of multivessel CAD, studies have shown similar sensitivity of all three tests [ 4 ]. Studies have shown low prevalence of significant ischemia and CAD mortality in patients achieving more than 10 METs on exercise stress test [ 5 ]. In a 2014 randomized controlled trial, all cause mortality was found to be similar in patients with suspected CAD and normal resting EKG who underwent EKG stress test with imaging compared to those without imaging [ 6 ].

Physicians seldom see reports of indeterminate stress test results which is when they depend on expert opinion for further evaluation. In this case, the patient was an overweight 54-year-old man who had a history of tobacco use but no other significant comorbidities were known. He was clinically stable during his hospital stay. We anticipated his testing would be negative. To complete workup, cardiology recommended anatomical testing with CCTA given the indeterminate EKG stress test results and this was performed immediately. The results of significant stenosis were surprising to the care team. CCTA is a relatively newer non-invasive anatomical test that has a high diagnostic accuracy to identify the presence of coronary plaques and stenosis. Since it can also determine the extent of stenosis, it is being used for CAD risk stratification. In patients with low to intermediate probability of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), it can be used as an initial test to rule out ACS owing to its high negative predictive value. It is also being utilized as an alternative to invasive coronary angiography in patients with equivocal stress test results.

Our case demonstrates a situation where CCTA proved to be a more accurate diagnostic tool than EKG stress testing. The results significantly altered management as the patient concluded his hospital stay with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Alternatively, if CCTA was not performed and the cardiologist deemed the indeterminate stress test results as negative, the patient may have been discharged and may have had a deleterious cardiac outcome. Recent guidelines from the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence recommend CCTA as the initial diagnostic test in patients with suspected CAD [ 7 ]. However, contrast-related side effects, availability of test, and cost are the main barriers to this recommendation at this time. CCTA has also been shown to have limited diagnostic accuracy in patients with intracoronary stents. The PROMISE trial showed no significant difference in clinical outcomes of patients with suspected CAD who underwent anatomical stress testing with CCTA compared to those who underwent functional stress testing [ 8 ]. However it may be worthwhile to utilize CCTA as the initial CAD diagnostic test if no contraindications are noted.

As a result of the availability of multiple noninvasive diagnostic tests with almost similar sensitivities for CAD, physicians often face this dilemma of choosing the right test for optimal evaluation of chest pain in patients with intermediate pretest probability of CAD. Optimal test selection requires an individualized patient approach. Our case describes a patient with intermediate probability of CAD presenting to the hospital with chest pain that resolved on admission and having a treadmill EKG stress test with indeterminate results. Decision to proceed with anatomical testing using CCTA was made and the patient was found to have significant CAD requiring CABG. Our experience with this case emphasizes the role of history taking, clinical judgement, and the risk/benefit ratio in deciding further workup when faced with inconclusive stress test results. Physicians should have a lower threshold for further workup of patients with inconclusive or even negative stress test results because of the diagnostic limitations of the test. Repeating the same test may result in uncertainty and indeterminate stress test should not be presumed as negative. Instead, utilizing a different, anatomical CAD test may be more valuable. Specifically, the case established the usefulness of CCTA in cases such as this where other CAD diagnostic testing is indeterminate.

Availability of supporting data

Data that supports this study have been referenced here.

Bourque JM, Beller GA. Value of exercise ECG for risk stratification in suspected or known CAD in the era of advanced imaging technologies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(11):1309–21.

Article Google Scholar

Christman MP, Bittencourt MS, Hulten E, et al . Yield of downstream tests after exercise treadmill testing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(13):1264–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.052 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alberto J, Román S, Vilacosta I, et al . Dipyridamole and dobutamine-atropine stress echocardiography in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: comparison with exercise stress test, analysis of agreement, and impact of antianginal treatment. Chest. 1996;110(5):1248–54.

Previtali M, Lanzarini L, Fetiveau R, et al . Comparison of dobutamine stress echocardiography, dipyridamole stress echocardiography and exercise stress testing for diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(12):865–70.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bourque JM, Charlton GT, Holland BH, Belyea CM, Watson DD, Beller GA. Prognosis in patients achieving ≥10 METS on exercise stress testing: Was SPECT imaging useful? J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18(2):230–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-010-9323-2 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Duvall WL, Lane Duvall W, Savino JA, et al . Prospective evaluation of a new protocol for the provisional use of perfusion imaging with exercise stress testing. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42(2):305–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-014-2864-x .

Overview | Recent-onset chest pain of suspected cardiac origin: assessment and diagnosis | Guidance | NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg95 . Accessed 18 Apr 2020.

Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al . Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1291–300.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge contribution of Dr. Nishit Choksi and Dr. Nishtha Sareen, who were the cardiologists involved in care of this patient. All the above stated authors have contributed significantly in writing and editing the manuscript.

No funding received.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Internal Medicine, Ascension Providence Rochester Hospital/Wayne State University School of Medicine, 1101 W University Drive, Rochester, MI, 48307, USA

Mishita Goel, Shubhkarman Dhillon, Sarwan Kumar & Vesna Tegeltija

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

We confirm that all authors have contributed in writing and drafting, obtaining images, editing and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mishita Goel .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval or formal consent not required for this type of study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

No competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Goel, M., Dhillon, S., Kumar, S. et al. Clinical judgement in chest pain: a case report . J Med Case Reports 15 , 49 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02666-z

Download citation

Received : 20 November 2020

Accepted : 06 January 2021

Published : 09 February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02666-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Stress test

- Coronary artery disease

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Create Free Account or

- Acute Coronary Syndromes

- Anticoagulation Management

- Arrhythmias and Clinical EP

- Cardiac Surgery

- Cardio-Oncology

- Cardiovascular Care Team

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- COVID-19 Hub

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Dyslipidemia

- Geriatric Cardiology

- Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Noninvasive Imaging

- Pericardial Disease

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

- Sports and Exercise Cardiology

- Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

- Valvular Heart Disease

- Vascular Medicine

- Clinical Updates & Discoveries

- Advocacy & Policy

- Perspectives & Analysis

- Meeting Coverage

- ACC Member Publications

- ACC Podcasts

- View All Cardiology Updates

- Earn Credit

- View the Education Catalog

- ACC Anywhere: The Cardiology Video Library

- CardioSource Plus for Institutions and Practices

- ECG Drill and Practice

- Heart Songs

- Nuclear Cardiology

- Online Courses

- Collaborative Maintenance Pathway (CMP)

- Understanding MOC

- Image and Slide Gallery

- Annual Scientific Session and Related Events

- Chapter Meetings

- Live Meetings

- Live Meetings - International

- Webinars - Live

- Webinars - OnDemand

- Certificates and Certifications

- ACC Accreditation Services

- ACC Quality Improvement for Institutions Program

- CardioSmart

- National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)

- Advocacy at the ACC

- Cardiology as a Career Path

- Cardiology Careers

- Cardiovascular Buyers Guide

- Clinical Solutions

- Clinician Well-Being Portal

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Innovation Program

- Mobile and Web Apps

Heart Failure Center Patient Cases

HOME | HF CENTER HOME | FAQ | ABOUT

Heart Failure: Ask the Expert – Patient Cases

Welcome to the GCVI HF Center’s Ask the Expert – Patient Cases channel! On this channel you will have access to multiple heart failure patient cases published by leading ACC experts. We also encourage you to engage and consult with ACC global experts on cases specific to your practice. Ask the Expert through the online portal below!

Engage with ACC global experts!

Heart Failure Patient Case Quizzes

- Unrecognized HFpEF in a Type 2 DM Patient – Reducing CV and HF Risk

- Untreated HFrEF/Ischemic Cardiomyopathy in Type 2 DM – How to Optimize Medical Therapy to Improve Heart Failure Outcomes

- Restrictive Cardiomyopathies Series: Advanced HF Therapies in ATTR Cardiac Amyloidosis (Certified Patient Case Study)

- ECG of the Month: Variable QRS Morphologies in Heart Failure

- Untreated HFrEF/Ischemic Cardiomyopathy in Type 2 DM

- Unrecognized HFpEF in a Type 2 DM Patient

Regional Patient Case Quizzes Select your region to view available courses.

JACC Journals on ACC.org

- JACC: Advances

- JACC: Basic to Translational Science

- JACC: CardioOncology

- JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging

- JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions

- JACC: Case Reports

- JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology

- JACC: Heart Failure

- Current Members

- Campaign for the Future

- Become a Member

- Renew Your Membership

- Member Benefits and Resources

- Member Sections

- ACC Member Directory

- ACC Innovation Program

- Our Strategic Direction

- Our History

- Our Bylaws and Code of Ethics

- Leadership and Governance

- Annual Report

- Industry Relations

- Support the ACC

- Jobs at the ACC

- Press Releases

- Social Media

- Book Our Conference Center

Clinical Topics

- Chronic Angina

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

Latest in Cardiology

Education and meetings.

- Online Learning Catalog

- Products and Resources

- Annual Scientific Session

Tools and Practice Support

- Quality Improvement for Institutions

- Accreditation Services

- Practice Solutions

Heart House

- 2400 N St. NW

- Washington , DC 20037

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: 1-202-375-6000

- Toll Free: 1-800-253-4636

- Fax: 1-202-375-6842

- Media Center

- ACC.org Quick Start Guide

- Advertising & Sponsorship Policy

- Clinical Content Disclaimer

- Editorial Board

- Privacy Policy

- Registered User Agreement

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

© 2024 American College of Cardiology Foundation. All rights reserved.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 4: 10 Real Cases on Valvular Heart Disease: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Nikhitha Mantri; Puvanalingam Ayyadurai; Marin Nicu

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion.

- Clinical Symptoms

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Management of Patent Foramen Ovale

A 26-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain for 1 day. The chest pain started suddenly, was nonradiating, and was associated with arm movement. She did house cleaning 1 day prior to presentation. The pain was not relieved by taking over-the-counter medication. She denied palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath, and trauma. Her family history and social history were unremarkable. On presentation to the ED, her vital signs were stable. On physical examination, she did not have any significant findings except chest wall tenderness. Her ECG showed first-degree atrioventricular block. Initial laboratory findings were unremarkable. She was given analgesics. The patient was transferred to the telemetry floor, where an echocardiogram was performed, which showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction with no wall motion or valvular abnormality and a small patent foramen ovale (PFO). How would you manage this case?

This patient is a young asymptomatic woman who presented with musculoskeletal chest pain. Incidentally, she was noted to have a PFO, which is asymptomatic and does not require any treatment.

PFO is an opening in the atrial wall at the location of the fossa ovalis that remains open beyond 1 year of life. After birth, when the pulmonary circulation develops, the foramen ovale closes due to the increase in left atrial pressures, which takes up to 1 year.

PFO is usually asymptomatic and is often found incidentally. However, it carries a risk of paradoxical embolism in high-risk patients. Some patients present with systemic embolism causing organ infarcts and even myocardial infarction.

The diagnostic test of choice is echocardiography. PFO can be detected using color flow Doppler, contrast echocardiography, and transmitral Doppler.

Isolated PFO does not usually require any treatment unless it is associated with an unexplained neurologic event. Such conditions are treated with antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulation therapy. Percutaneous closure of the PFO is an option when there is contraindication to medical management and anticoagulant treatment, in the setting of paradoxical embolism or cryptogenic stroke. Surgical closure is indicated when the opening is >25 mm or when there is failure of a percutaneous device.

PFO is usually asymptomatic and is often found incidentally.

Isolated PFO does not usually require any treatment unless it is associated with an unexplained neurologic event.

Case 2: Management of Aortic Stenosis

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Complete Your CE

Course case studies, external link, this link leads outside of the netce site to:.

While we have selected sites that we believe offer good, reliable information, we are not responsible for the content provided. Furthermore, these links do not constitute an endorsement of these organizations or their programs by NetCE, and none should be inferred.

Women and Coronary Heart Disease

Course #33224 - $90 -

#33224: Women and Coronary Heart Disease

Your certificate(s) of completion have been emailed to

- Back to Course Home

- Review the course material online or in print.

- Complete the course evaluation.

- Review your Transcript to view and print your Certificate of Completion. Your date of completion will be the date (Pacific Time) the course was electronically submitted for credit, with no exceptions. Partial credit is not available.

CASE STUDY 1

The following case studies offer an opportunity for healthcare professionals to test or improve their skills in observation and diagnosis. While the outcome in each has already been determined, the information and scenarios may be used to help in day-to-day patient interaction. Analyses of all of the case studies are presented following this section.

Read through the following clinical vignettes and take time to review each woman's cardiovascular risk factor profile. Then, refer to the questions at the end of the case study to analyze each female patient's current health status.

Patient S is a White woman, 43 years of age, and mother of three small children. She has a long-standing history of significant obesity with little success in dieting over the years. At 5'3", she is obese, weighing 220 pounds. Her fat distribution is "apple-shaped" and consequently, her waist-hip ratio is more than the 0.8 normal range. In addition, Patient S lives a fairly sedentary lifestyle and does not have a regular exercise program. Her dietary habits do not take into account basic recommendations for cardiac nutrition.

Patient J is 55 years of age and teaches high school English. Her cardiovascular risk factor profile includes a 30-pack-year history of cigarette smoking and altered lipid levels. Her HDL is only 35 mg/dL and her LDL is 145 mg/dL. Patient J has tried with little success to control her cholesterol with diet. Recently, she began taking gemfibrozil as prescribed by her family physician, but has not followed his recommendation to quit smoking and enroll in a smoking cessation program at a local hospital. Rather, she continues to smoke one pack of cigarettes per day.

Patient V is a woman, 47 years of age, who has a family history of CHD. Although she denies ever experiencing cardiac symptoms, her brother suffered a nonfatal MI at 46 years of age and her father had an MI at 53 years of age. Both of these cardiac events were medically managed. However, her father's disease did progress to the point that he underwent CABG surgery five years ago. He had three coronary artery lesions bypassed. In addition to her family history, Patient V is approximately 30 pounds overweight and does not exercise on a regular basis. She drinks approximately two to three glasses of red wine per day and has never smoked.

Patient D is 67 years of age and lives in an assisted living retirement community. An insulin-dependent diabetic since adolescence, Patient D is unable to care for herself due to the effects of the diabetes on her eyesight, as well as the development of peripheral neuropathies. In addition to the diabetes, Patient D continues to smoke. By now, she has a 40-pack-year history of smoking.

Patient F is an African American woman, 36 years of age, with a history of mild hypertension. Her blood pressure has been fairly well controlled on an ACE inhibitor over the past two years. Patient F eats a well-balanced, nutritious diet, exercises three to five times a week, and does not have a history of smoking or alcohol use. However, she does exhibit excessive competitiveness, being harried, and rushing to complete more and more tasks in an ever-shrinking period of time. In addition to these characteristics, she exhibits a somewhat cynical or negative outlook with occasional expression of hostile or angry thoughts and feelings.

In analyzing these clinical vignettes, consider the following questions:

Which of these women is at greatest risk for CHD?

Who is at least risk?

What recommendations would you make in counseling each patient regarding her cardiovascular health?

Case Study 1 Analyses

All five of these women have risk factors for CHD. However, Patients J and D possess three of the most significant cardiovascular risk factors: cigarette smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. Therefore, based on the data available in the vignettes, Patients J and D are at greatest risk for CHD. If further information was available about each woman's cardiac risk factor profiles, we might be able to differentiate even further to determine which of these two women is at greater risk.

Patient F appears be in the best cardiovascular state among the group. Her mild hypertension is well controlled; she is not overweight, eats a sensible diet, and sees that she gets some form of aerobic exercise at least three times a week.

What specific recommendations would you make in counseling each woman about her cardiovascular health?

Counseling recommendations for Patient S would primarily focus on cardiac nutrition aspects and developing an exercise program for cardiovascular fitness. Because she is more than 30% overweight, she is at a tremendously increased risk of CHD due to the added stress on her heart and the changes that occur in lipid metabolism when fat is distributed in the abdominal versus gluteal region. Therefore, patient teaching should emphasize good nutrition and reading nutrition labels to manage caloric intake, as well as limiting intake of fat and cholesterol. In addition to changes in diet, Patient S should be counseled on incorporating some form of aerobic exercise, such as walking, three to five times a week to achieve cardiovascular fitness. The exercise will also have the added benefit of helping her modify her weight level.

Two major concerns become evident in assessing Patient J's health status—her smoking history and her hyperlipidemia. Recommendations would focus on encouraging and motivating the patient to quit smoking, through the use of the nicotine patch or gum with the additional support of bupropion and/or a smoking cessation program to increase her chances of successfully quitting. These programs are essential because they teach the patient behavioral and psychologic techniques to utilize at various stages of the quitting process and help the person identify specific problem situations and how these can be realistically managed. Patient J's lipid profile should be closely monitored to determine the effectiveness of gemfibrozil in lowering her LDL levels. In addition, patient teaching should focus on the deleterious effects of smoking on lipid profiles, specifically HDL levels. Smoking tends to decrease levels of HDL, which could be used as another health information tidbit to motivate Patient J to quit smoking.

Recommendations for cardiac health for Patient V would primarily focus on the alterable factors rather than her significant family history, which cannot be changed. As a result, patient teaching and counseling would be geared toward getting her weight into a more desirable range by paying attention to nutrition and getting some form of regular aerobic exercise. Patient V would also benefit from more health teaching regarding alcohol consumption. While a moderate intake of alcohol may be associated with positive antioxidant effects that can impart some protection against the development of CHD, the key is moderation. One drink per day is the recommendation for alcohol consumption in women.

In assessing Patient D's health history, her diabetes and smoking habit are big concerns. In terms of her diabetes, she is in need of strict control to prevent further progression and significant complications associated with the disease, such as CHD. Another major factor that would help prevent a major cardiac event is for her to quit smoking. Remember that many cardiovascular risk factors are synergistic. In other words, risk factors work together in increasing an individual's risk of developing CHD. Cigarette smoking and diabetes are both powerful independent risk factors for CHD, and together, they significantly elevate the chances of developing the disease.

Patient counseling recommendations for Patient F are twofold: continued control of her hypertension and stress management. Patient F and all of the women should be applauded regarding the positive habits they have incorporated into their lifestyle. In this patient's case, these positive aspects include attention to nutrition, aerobic exercise, and staying away from smoking or alcohol use. She does, however, need assistance with stress management. While her regular exercise program is most likely one avenue for her to deal with this stress, it obviously is not singly effective. In other words, additional stress management strategies could be added to her repertoire.

CASE STUDY 2

Patient M is a White woman, 75 years of age, who presented to her local emergency department with sudden complaints of chest pain. She described the pain as a severe substernal burning sensation that radiated across the chest to her shoulders bilaterally and then to the neck and jaw region. Although not brought on by exertion, the chest pain was associated with dyspnea, pallor, diaphoresis, nausea, and epigastric discomfort. Patient M had taken one nitroglycerin tablet with partial relief. When the chest pain recurred 10 to 15 minutes later, her family dialed 911 and the local emergency medical service responded. Once transported to the emergency department, her pain persisted. She received two additional doses of nitroglycerin and was placed on 2 L of oxygen per nasal cannula.

Following stabilization, she was admitted to a telemetry floor for further observation and medical management. Nursing assessment revealed the following cardiovascular risk factors: 50-pack-year history of smoking, hypertension, and mild-to-moderate obesity. As part of the medical workup, Patient M was scheduled for a coronary angiogram the following day. The angiogram revealed an 80% blockage of the right coronary artery and the cardiologist recommended Patient M consider a PCI to open the coronary artery blockage.

The following day, Patient M underwent a PCI to the right coronary artery. The procedure was progressing uneventfully until she had an episode of bradycardia as her heart rate dropped to 38 beats per minute. The patient received a 0.5 mg dose of IV atropine, which was repeated in 10 minutes. Other than this episode, Patient M did not experience any other postprocedure complications, such as hypotension, or other technical-related problems.

The day after the PCI, Patient M was receiving her discharge instructions from her nurse when she began noticing a return of the dull epigastric pain. The pain did not appear to be related to her food intake because she was progressing on her diet. Later that day, as the pain persisted, Patient M had an ultrasound of her abdomen, which showed multiple walnut-sized gallstones. The gastroenterologist referred her to a general surgeon who recommended that she undergo a cholecystectomy for further relief of her gastrointestinal symptoms. The surgeon advised her of the risks and benefits of laparoscopic versus traditional surgery, and Patient M opted for the laparoscopic procedure. Four small incisions were made in her abdomen, and the cholecystectomy was performed without any complications. Three days postoperatively, she complained again of moderate-to-severe epigastric pain and became jaundiced. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography revealed retained stones in the common bile duct, which were removed. Patient M subsequently recovered and was discharged home after a total of nine days in the hospital.

In analyzing this case study, consider the following questions:

What cardiovascular risk factors are present? What risk factors are negative?

Is the patient's chest pain syndrome typical or atypical for women? Why or why not?

What tests would you anticipate in the diagnostic workup of women experiencing angina?

What nursing diagnoses would be appropriate for this patient during hospitalization? What special implications do these diagnoses have in women?

Case Study 2 Analyses

What coronary risk factors are present? What risk factors are negative?

The cardiovascular risk factors known for Patient M include her age, postmenopausal status, smoking history, and hypertension.

The chest pain syndrome experienced by Patient M is typical for women. She described the chest pain as a substernal burning sensation that radiated across her precordium to her shoulder region bilaterally and then to her neck and jaw. In addition, her chest pain was accompanied by dyspnea, diaphoresis, nausea, and epigastric distress, all of which may or may not be associated with anginal episodes in women. In contrast, chest pain in men often begins substernally and spreads across the left precordium down the left arm.

What tests would you anticipate to be in the diagnostic workup of women experiencing angina?

The diagnostic phase for women with angina often begins with a resting 12-lead ECG. This test is useful in women due to their higher proportion of silent or unrecognized infarctions. Conversely, the exercise ECG is not considered a good test in women due to high false-positive rates and other problems associated with women exercising at adequate intensity levels. Other noninvasive cardiac diagnostic tests might include nuclear myocardial perfusion scans and exercise echocardiogram. Of these three tests, the exercise echocardiogram is the best test for women. It is associated with the highest accuracy rates and is especially sensitive to single vessel disease, which occurs more frequently in women than in men.

Decreased Cardiac Output : With the sudden onset of angina and need to undergo a PCI to open a blockage of the right coronary artery, Patient M is at risk for decreased cardiac output. Women should be taught to take angina seriously and to have it evaluated by a physician as soon as possible. This is especially critical in women because they have an unfavorable prognosis post-MI. After PCI, women also have higher mortality rates and, therefore, should be carefully assessed. Complications must be recognized early in their course so they can be corrected and managed successfully.

Pain : Patient M really has two etiologies of her pain: chest pain and epigastric discomfort referred from her biliary tract disease. It is important to recognize that angina is often more severe in women than men (and both stable and unstable angina are more frequent in women), and therefore, necessary pharmacologic therapy may be more intense. In women, angina is managed best by either nitrates or calcium channel blockers, although the dosage may not be the same as it is in men. Because women have been excluded from many clinical drug trials testing cardiac medications, the optimal dose of various medications to treat women is less well known. Further research is needed to guide this area of clinical practice.

Knowledge Deficit : Like any other patient undergoing diagnostic testing and an invasive cardiac procedure, not to mention the cholecystectomy, Patient M should be taught about various components of her illness and hospitalization. These components include her disease process, diagnostic tests, medications, risk factor modification, and the recovery process, with emphasis on the long-term positive outcomes associated with PCI in women. In addition, when teaching female cardiac patients, it is vital to search for patient teaching materials that discuss the unique concerns of women with CHD.

CASE STUDY 3

Patient Y, a woman 76 years of age, was seen in the Women's Cardiac Center for a personalized health and risk factor assessment. Assessment findings included a heart rate of 84 beats per minute, blood pressure 172/68 mm Hg, height 5'5", and weight 171 pounds. Waist-hip ratio was 0.75, and skin fold calipers measured 42% body fat. Lipid profile included total cholesterol of 239 mg/dL, HDL 40 mg/dL, LDL 159 mg/dL, ratio 5.9 mg/dL, and triglycerides 248 mg/dL. Fasting glucose was 79 mg/dL. Past medical history included hiatal hernia, cholecystectomy, hypothyroidism, arthritis, insomnia, and a long-standing history of ankle edema. The patient also reported symptoms suspicious of sleep apnea.

Based on this assessment, cardiovascular risk factors were identified and the patient was instructed on risk factor modification. Four months later, she phoned the Women's Cardiac Center with complaints of anterior chest discomfort that radiated to her neck, jaw, and back, accompanied by shortness of breath. She was referred to Cardiology and seen three days later.

The diagnostic workup included a 12-lead ECG and nuclear myocardial perfusion scan, followed by an angiogram. She was not considered a candidate for the exercise EKG due to her advanced age and other comorbidities, specifically arthritis, which would limit her ability to exercise at adequate intensity levels. The 12-lead ECG revealed nonspecific T-wave changes in the inferior leads, and the nuclear scan was positive, suggestive of single-vessel disease of the left circumflex artery. An angiogram was then performed and showed triple vessel disease with significant left main disease. Her occlusions were 50% to 60% of the left main, 90% of the circumflex, and 60% of the right coronary artery. EF was estimated at 60%, indicating preserved left ventricular function. Based on these diagnostic findings, the patient was referred for CABG surgery.

Two weeks later, Patient Y underwent CABG surgery with internal mammary grafting. During surgery, she required inotropic support with dobutamine and epinephrine and atrioventricular sequential pacing. An intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was also placed via the right femoral artery due to right heart failure. On the first postoperative day, the patient remained in the intensive care unit on the IABP and ventilator. Lab values showed a creatine phosphokinase of 3113 IU/L and creatine kinase isoenzyme MB of 169.4 IU/L. A bedside echocardiogram confirmed an inferior-posterior and right ventricular infarct.

The patient was transferred to the cardiac surgical stepdown unit on the third postoperative day where she developed atrial fibrillation and was digitalized. Oxygen was administered at 5 L per nasal cannula and her ambulation was significantly limited. In addition, a bruit was noted in her right groin. An echo-Doppler revealed a two-chamber pseudoaneurysm which was unsuccessfully compressed. On the sixth postoperative day, the patient went in and out of atrial fibrillation/flutter and converted to sinus rhythm on postoperative day 7. As a result, she was weaned from oxygen and progressed with independent ambulation. However, she remained hospitalized until postoperative day 12 for observation of her heart rhythm and right groin pseudoaneurysm.

Two days after discharge, the patient received a follow-up telephone call from the Cardiac Liaison Nurse to assess her condition. Patient Y stated she was "feeling pretty good," yet indicated some difficulty with incisional pain, anorexia, fluid loss, insomnia, and confusion about her medications. After recuperating at home, the patient enrolled in a phase II cardiac rehabilitation program. At this time, the patient reports no angina or chest discomfort. She is progressing in her exercise program and tolerating activity. Problems experienced since discharge include a urinary tract infection, depression, and increasing heart failure. Her furosemide dosage has been increased, and she has obtained good relief of her symptoms.

What is the common picture of a woman's general health and cardiac status when referred for CABG surgery?

What significance does this patient's perioperative MI have for her long-term prognosis?

Identify ways to assess both short- and long-term outcomes of women post-CABG surgery.

Case Study 3 Analyses

Patient Y has the following cardiovascular risk factors:

Age: Older than 60 years of age

Positive family history: Both parents died from CHD

Hypertension: 172/68 mm Hg

Hypercholesterolemia: Total cholesterol 239 mg/dL; HDL 40 mg/dL; LDL 159 mg/dL; ratio 5.9; triglycerides 248 mg/dL

Body composition: Percentage of body fat is 42%

Menopause: Received HRT for 20 years

Stress: Rated as a 5 on a 0 to 10 scale

The following cardiovascular risk factors are negative:

Personal history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease

Smoking history

History of alcohol consumption

Sedentary lifestyle (Reports walking one mile per day)

As in the previous case study, Patient Y's chest pain syndrome is fairly typical for women. She experienced chest discomfort in the anterior region of her chest, which then radiated to her neck, jaw, and back. The chest pain was also accompanied by shortness of breath, which may or may not occur in women, just like other associated symptoms such as nausea, diaphoresis, or lightheadedness.

What is the common picture of a woman's general health and cardiac status when referred for CABG?

Like Patient Y, women who are referred for CABG surgery tend to be older with more comorbidities or multiple health problems, including hypertension, hypothyroidism, sleep apnea, arthritis, hiatal hernia, and sciatica. In terms of cardiac status, women tend to be referred more often for unstable angina, in comparison to men who usually are referred on the basis of a positive exercise ECG. In addition, women tend to have a lower incidence of prior MI before surgery and thus have better EFs, fewer diseased arteries or more single vessel disease (50% have single-vessel disease versus 25% two-vessel and 25% three-vessel disease), and more left ventricular hypertrophy and mitral regurgitation.

What significance does the patient's perioperative MI have for her long-term prognosis?

Women who suffer an MI have a worse prognosis than men, which is why timely diagnosis with an appropriate workup and treatment is so important in women experiencing anginal symptoms. When women go on to infarct, they have a much greater chance of not surviving, both in the early postinfarct period as well as later in their clinical course.

Decreased Cardiac Output : Patient Y was a woman with complaints of angina who underwent CABG surgery. During the surgical procedure, she suffered an inferior-posterior and right ventricular infarct. Despite the fact that her left ventricular EF was preserved at 60% post-MI, she should be carefully observed for early signs of heart failure, as well as any other complications during the postoperative period.

Pain : Again, prior to surgical intervention, Patient Y's angina should be carefully assessed and treated with nitrates or calcium channel blockers to prevent an acute MI, which would significantly impact her prognosis and long-term outcome. While postsurgical pain is most likely incisional, it is still important to assess for the return of angina, which could signal reocclusion of one of the bypass grafts.

Activity Intolerance : Patient Y is 76 years of age with multiple health problems, including arthritis. She will likely be slow to mobilize in the postoperative phase to begin with, which is compounded by the problems she developed with postoperative atrial fibrillation. After her ventricular rate was controlled and the pseudoaneurysm was addressed, her cardiac rehabilitation activity and exercise program was appropriately resumed.

Body Image Disturbance : This is a potential nursing diagnosis for Patient Y given her feelings of depression in the postdischarge phase. These feelings could be considered a normal part of recuperation and a reflection of perceived changes in body image due to the sternotomy and leg incisions. After being discharged home, she did complain of continued incisional pain that could be partially alleviated by wearing a supportive bra to decrease tension from the breasts.

Knowledge Deficit : As with Patient M in Case Study 2, Patient Y has a knowledge deficit regarding her cardiac disease and surgical procedure. Patient teaching for Patient Y should incorporate elements such as disease process, cardiac medications, activity restriction, caring for the surgical incision, risk factor modification, outpatient cardiac rehabilitation, and the recovery process. She would also benefit from gender and sex-specific patient teaching aids, if available, so she could relate to the unique concerns and needs of women who have faced CHD and CABG surgery.

Patient outcomes may be measured both during the hospitalization and postdischarge phases. During the hospitalization phase, examples of clinical outcomes to be assessed for a population of female cardiac patients include complication rates (e.g., perioperative MIs, dysrhythmias, pseudoaneurysms); length of stay (both intensive care unit and hospital length of stay); and readmissions (both intensive care units and hospital readmissions), along with the clinical reasons.

After the hospitalization phase, patient outcomes may be assessed again. Examples of outcomes to be measured in the early discharge phase include pain, appetite, wound healing (incisions in surgical patients), rest/sleep patterns, psychologic comfort, and exercise patterns. Teaching and learning outcomes are also important to assess, including whether the female cardiac patient understood her discharge instructions related to activity and exercise, cardiac medications, diet, and when to return to work. Quality of life becomes an important consideration for this population. Research suggests that women experience more days of restricted activity due to continuing cardiac symptomatology, such as recurring chest pain and dyspnea. Ability to return to work and previous hobbies and pastimes would be an important area to assess in this regard.

CASE STUDY 4

Patient A was a woman, 88 years of age, who lived in an assisted living retirement home. She had been a widow for 20 years, after losing her husband to long-term complications associated with diabetes. Until approximately seven years ago, Patient A had been in relatively good health with no major health problems, but she suffered a mild stroke at 81 years of age. At that time, she decided to quit her 50- to 60-year smoking habit. Other than her smoking history, she did not have any other significant cardiovascular risk factors.

After recuperating from her stroke, Patient A decided to leave her apartment and move into the assisted living facility where she would not only have some companionship but also receive assistance with meals and transportation to doctor's appointments and other activities. About six years after suffering the cerebrovascular accident, she had a bout of heart failure. She was admitted to the local hospital and received oxygen per nasal cannula, IV furosemide, and digoxin. After two weeks in the hospital, the patient was discharged home in apparently better condition. However, two days after returning home Patient A suffered a sudden cardiac death event at the breakfast table. Efforts at resuscitation were unsuccessful.

Case Study 4 Analyses

Positive cardiovascular risk factors for Patient A include the nonalterable factors of age and menopause and the alterable factor of smoking history. The risk factors that were negative in her history include family history of CHD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, or psychosocial concerns.

Patient A's cardiac event is atypical for women in terms of initial presentation of the disease process. MI and sudden cardiac death are more commonly a first manifestation of CHD in men, while angina is the most common presenting scenario for women. Women tend to lag behind men in both the occurrence and incidence of CHD, as well as sudden cardiac death events. In terms of Patient A's history, it is possible that she initially suffered an MI, which was not recognized, and went on to develop heart failure as a post-MI complication. This then explains her increased risk for earlier reinfarction and higher mortality.

CASE STUDY 5

Patient H, a White woman 60 years of age, suddenly began complaining of chest pain one evening. The pain was substernal, spread down both arms bilaterally, and radiated to her neck and jaw region. Patient H also complained of shortness of breath, nausea, and diaphoresis. Never having witnessed these symptoms before, Patient H's husband and daughter transported her to the local emergency department.

When she arrived in the emergency department, immediate priorities focused on obtaining a brief yet comprehensive history of symptomatology and past medical problems, as well as instituting appropriate treatments. The health assessment revealed numerous cardiovascular risk factors. Patient H's increasing age is one nonalterable risk factor present. In addition, she has a significant family history of CHD. Her mother and grandmother both suffered fatal heart attacks in their late 50s or early 60s. While Patient H does not have a history of smoking, she does have hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. She is also obese, with a height of 5'2" and weight of 240 pounds and does not report engaging in a regular exercise program.

In terms of supportive treatment, Patient H was placed on 3 L of supplemental oxygen per nasal cannula and given sublingual nitroglycerin. She rated her pain an 8 on a 0 to 10 scale and did not report an appreciable decrease in her pain level after the first nitroglycerin dose. A second sublingual dose was given, after which she obtained relief. In the diagnostic workup phase, Patient H had a 12-lead ECG that revealed signs of ischemia in leads II and III and a ventricular dysrhythmia. Serial cardiac enzymes were drawn to rule out MI. Patient H was admitted to the coronary care unit (CCU) for treatment of an inferior MI.

Once transferred to the CCU, the patient was placed on the bedside monitor and a left radial arterial line and left subclavian Swan Ganz catheter were inserted for hemodynamic monitoring purposes. A bedside echocardiogram was performed to assess left ventricular EF and overall function of the chambers of the heart. The exam revealed that left ventricular EF was not preserved, estimated at only about 40% pumping function. Positive inotropes were started to increase the contractility of the heart and improve cardiac output. Intravenous nitroglycerin that was started in the emergency department was continued to improve coronary perfusion and for afterload reduction. After two days, Patient H was transferred out of the CCU to the cardiology stepdown unit. Telemetry showed slight sinus bradycardia at a rate of 56 beats per minute without ectopy. Other vital signs included blood pressure 102/56 mm Hg and a respiratory rate of 26 breaths per minute. Patient H remained on supplemental oxygen at 2 L per nasal cannula.

Cardiac rehabilitation was initiated when Patient H was in the stepdown unit. Rehabilitation activities first focused on identifying her risk stratification level, from low to high on a continuum, to guide initial activity and further exercise prescriptions. Because the patient's left ventricular EF was approximately 40%, her risk stratification level was identified as moderate and she was instructed that her cardiac rehabilitation activity would entail ambulating three times a day, first with monitored assistance in the hallway, working eventually toward the goal of independent ambulation. Prior to her first ambulation, Patient H's nurse took orthostatic blood pressure readings with the following results: lying 120/68 mm Hg; sitting 116/64 mm Hg; and standing 112/62 mm Hg. Heart rate pre-exercise was 58 beats per minute. As a result of these data, Patient H was assisted into the hallway for monitored ambulation. After walking for approximately two minutes, her heart rhythm converted from sinus bradycardia into a fast atrial fibrillation, with a ventricular rate of 180 beats per minute. Her blood pressure was 102/56 mm Hg. The patient was assisted back to bed, and a cardiology consult was requested.

The consulting cardiologist ordered a diltiazem drip. After her ventricular rate was under control, the patient was digitalized with 1 mg of digoxin followed by a maintenance dose of 0.125 mg IV. Other cardiac medications added to the regime included a beta blocker, furosemide, and potassium.

On the day of discharge, Patient H's family was present for discharge teaching. Her nurse explained the list of medications, including the dose and frequency, as well as her activity limitations. Patient H was instructed not to drive a car for two weeks and to increase her walking each day by one minute until she arrived at the goal of approximately 30 to 45 minutes at least three times a week. In addition, Patient H was informed about the nearest outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program. It was explained to her that the primary benefits of attending an outpatient program would be that the staff would assist her in developing an activity and exercise program individualized to her needs and physical capabilities. In addition, they would teach her and her family other components of heart healthy living, such as cardiac nutrition, managing diabetes, and stress.

After discharge, the patient did enroll in an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program and had attended three sessions when she began developing symptoms of heart failure, including orthopnea, shortness of breath, and weight gain. On physical examination, crackles were auscultated bibasilarly and dependent pitting edema was present in her ankles bilaterally. On being seen in the heart failure clinic, she was restarted on a diuretic, furosemide, and an ACE inhibitor and her digoxin was kept at the same dosage.

What special implications exist with regard to dosing cardiac medications in women?

Describe the common response of women with CHD to activity.

What factors influence women's involvement in cardiac rehabilitation programs?