Trauma Is Everywhere. Write About It Anyway.

Melissa Febos’s recent essay collection shows us not only how to capture the difficult, intimate details of our lives in writing, but why we should.

Every day—through TikTok, Instagram, and Zoom—the internet forces us to think about how we present ourselves to the world, giving us endless opportunities to construct our identities anew. Little wonder, perhaps, that the personal feels ubiquitous in contemporary writing, too, with a slew of publications that draw from, or appear to draw from, the lives of their authors. (Think of the novels of Douglas Stuart, the essays of T Kira Madden, and the poems of Ocean Vuong, all writers who mingle personal experiences with exceptional creative writing.) But in the past few years, I’d argue that another driving force has been behind much personal writing: the many traumas of recent vintage, including the pandemic , racist violence, and the mental-health crisis . As these events have piled up, my writing students have become more interested in rendering their own experiences—especially the painful ones.

Melissa Febos is at the vanguard of this particular boom in confessional writing, and she is the guide I point my students to when they want to write in this style. She’s best known for her nonfiction: Whip Smart , Abandon Me , and last year’s Girlhood , a masterful analysis of growing up female , which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. Febos is an engaging, cerebral writer who mingles what might seem like familiar ingredients—research, interviews, cultural critique, and personal anecdotes—in surprising ways. Her latest book is Body Work , an essay collection that sets out to teach the craft of personal writing by not only showing us how to capture the difficult, intimate details of our lives, but also arguing for why we should pursue the practice in such a challenging time.

Read: The unending assaults on girlhood

“This is not a craft book in the traditional sense,” Febos asserts early on. Body Work , I learned over its 192 taut pages, is an explanation of why stories like Febos’s are powerful, and moreover, why they take so much work. In their attempts to write in the confessional form, my students inevitably encounter dilemmas—including struggles over sentence sequencing and the fear of problematic ex-boyfriends reading their work—that Febos wants to help resolve. “Writing has become for me,” Febos says in Body Work ’s author’s note, “a primary means of digesting and integrating my experiences and thereby reducing the pains of living, or if not, at least making them useful to myself and to others.”

There’s a musty axiom put forward in writing classes that forging this type of connection with a reader shouldn’t be the priority, that writers should instead aim to create art that transcends personal concerns. But relatability is at the very core of Febos’s project, which makes it essential for teaching the kind of writing that many students are interested in producing in 2022. This doesn’t mean that Febos thinks we should do away with the classic nuts and bolts of technique: Body Work argues that after an initial unburdening—that confessional rush at 2 a.m. in the Notes app—drafts should pile on drafts. Febos maintains an emphasis on form that is nicely balanced throughout the book by some charming, low-level woo-woo. (This is, for example, the only craft book I’ve read that describes, step-by-step, the process the author followed to cast a spell on an ex-lover. I might try it.)

Body Work begins with an extended version of an essay that I’ve taught for years, which Febos published in 2016 in the magazine Poets & Writers : The Heart-Work: Writing About Trauma as a Subversive Act . It speaks to the need to write about personal trauma without the fear of seeming navel-gazey . “Since when did telling our own stories and deriving their insights become so reviled? It doesn’t matter if the story is your own … only that you tell it well,” Febos writes. This essay always opens up my students, many of whom worry that their life might be “too boring” to merit a personal essay. When trauma is a near-universal experience, is that trauma still interesting? It is—of course—but it can be hard to feel that. To find the creative spark in a difficult moment can be extraordinarily liberating.

Read: To write a great essay, think and care deeply

Febos argues that one reason a writer might fear that their stories don’t have value is a function of our society’s preconceived notions about certain people or groups. Pivoting to a personal anecdote from her book tour for Whip Smart , a memoir in which Febos chronicles her experience working as a dominatrix, she writes:

Interviewers asked only about my experiences and never about my craft. At readings, I would be billed on posters as “Melissa Febos, former dominatrix” alongside my co-reader, “[insert male writer name], poet.” Even some friends, after reading the book, would write to me to exclaim, “The writing! It was so good ,” as if that were a happy accident accompanying my diarist’s transcription.

Throughout Body Work , we see this sort of maneuver, which I’ve come to think of as Febosian: a critical assertion—in this case that female-identifying writers are too often reduced to their biography—supported by an entertaining personal anecdote. The author’s life, in other words, becomes an inexorable part of her argument (in a book about making one’s life an inexorable part of one’s writing).

I’ve found in my own work that including personal anecdotes can be challenging, because to make them worthwhile we must view ourselves through a lens that allows for weakness and even wrongdoing. Febos offers some guidance on this too: “When something seems difficult, in writing and in life, we tend to make rules around it,” she asserts in a section on sex writing, before presenting antidotes to common creative roadblocks with a list of productive “unrules”: “ You can use any words you want. Sex doesn’t have to be good. ”

Even when Febos reaches a thesis that I disagree with—“that to write an awakened sex scene, one may need to be awake to their own sex”—I’m persuaded by her argument for the need for creative honesty. I took my first writing class during my semester abroad in Italy, a time during which I was definitely asleep to my own sex. But I wrote, because my teacher made me write, a sex scene. I agonized over it. And the little scene I ended up producing was the single thing that made me realize that I wanted to keep writing forever. Confessing my own limitations liberated me: For the first time, a character of mine moved on their own. It felt like magic. I’ve been chasing that feeling ever since.

My favorite passage in Body Work , though, and the anecdote that argues most convincingly for the necessity of creative confession, is an epiphanic sequence in which Febos recalls the experience of writing about a challenging relationship, the story of which became the foundation of Abandon Me. As she wrote a draft, Febos realized that “there was only one correct ending to my story: my narrator would leave her lover.” In other words, her creative practice helped her understand what her rational mind couldn’t. This is a lesson that many of my students mention: The act of writing for my class has helped them discover something about themselves.

And I thought I knew what they meant.

But recently, as in 24 days ago, at the moment I’m typing the first draft of these words, my brother died. It has been an impossible time of intrusive imagery, random floods of emotion, and extreme disassociation. My brain’s actions are unpredictable. They frighten me.

Writing about my loss, my therapist told me, would be good for someone like me, to whom writing comes naturally. “It’s a way to process and recognize yourself,” he said. “To find a way to engage.” By trying to encounter my brother’s death in active form, in other words, I could start to metabolize it.

What I can say is that the night I learned my brother had died, I retreated to my parents’ living room, an incoherent mess of tears, or whatever flood state exists beyond tears. I wrote a few sentences. I wasn’t trying to make art, but I wasn’t journaling either. I didn’t feel better afterward, but I did feel a bit different. My thoughts were less frantic and more grounded. I’ve continued that writing practice every night since, slowly turning my initial rush of honesty into something that could potentially connect with others. Body Work helped me learn how to work alongside and through my ongoing pain by forging a creative outlet. I’m grateful to Febos for the lesson in how to do it.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE RADICAL POWER OF PERSONAL NARRATIVE

by Melissa Febos ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 15, 2022

Sharp insights from a passionate practitioner and champion of memoir.

A writer known for her candid autobiographical writing about sex, trauma, and female identity lays out the tenets of her craft.

Febos takes no prisoners in this strongly worded manifesto—despite her claim on the first page that it is not a manifesto. In fact, her impassioned theses and proclamations about writing are exactly that. Proceeding from the principle that “writing is a form of freedom more accessible than many and there are forces at work in our society that would like to withhold it from those whose stories most threaten the regimes that govern this society," she turns the charge of "navel-gazing" on its head. She further points out that memoirists do not publish raw therapeutic diaries but crafted literary works with the power to change the world. Her blunt anger is understandable. “At readings I would be billed on posters as MELISSA FEBOS, FORMER DOMINATRIX, alongside my co-reader, [INSERT MALE WRITER NAME], POET." In a chapter called "Mind Fuck," Febos lays out rules for writing about sex, starting with "You can use any words you want,” and she illustrates her points with well-chosen quotes from writers like Marie Howe, Nancy Mairs, Carmen Maria Machado, and Cheryl Strayed. In a useful chapter addressing the pitfalls of writing about other people, Febos describes her own approach and practices, developed via hard experience. A section called "Mom Goggles," for example, goes right to the question many readers may have about the writer's often X-rated work: Does her mother read it? It turns out she does, along with other family members, prior to publication. The author’s exhortations with regard to craft—"every single notation—every piece of punctuation, every word, every paragraph break in a piece of writing is a decision"; "The I of [the] narrator is not the I that writes the book"—are crucial, likely distilled from her lectures at the University of Iowa.

Pub Date: March 15, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-64622-085-4

Page Count: 192

Publisher: Catapult

Review Posted Online: Dec. 6, 2021

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 1, 2022

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | SELF-HELP | GENERAL NONFICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Melissa Febos

BOOK REVIEW

by Melissa Febos

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

IndieBound Bestseller

A WEALTH OF PIGEONS

A cartoon collection.

by Steve Martin illustrated by Harry Bliss ‧ RELEASE DATE: Nov. 17, 2020

A virtuoso performance and an ode to an undervalued medium created by two talented artists.

The veteran actor, comedian, and banjo player teams up with the acclaimed illustrator to create a unique book of cartoons that communicates their personalities.

Martin, also a prolific author, has always been intrigued by the cartoons strewn throughout the pages of the New Yorker . So when he was presented with the opportunity to work with Bliss, who has been a staff cartoonist at the magazine since 1997, he seized the moment. “The idea of a one-panel image with or without a caption mystified me,” he writes. “I felt like, yeah, sometimes I’m funny, but there are these other weird freaks who are actually funny .” Once the duo agreed to work together, they established their creative process, which consisted of working forward and backward: “Forwards was me conceiving of several cartoon images and captions, and Harry would select his favorites; backwards was Harry sending me sketched or fully drawn cartoons for dialogue or banners.” Sometimes, he writes, “the perfect joke occurs two seconds before deadline.” There are several cartoons depicting this method, including a humorous multipanel piece highlighting their first meeting called “They Meet,” in which Martin thinks to himself, “He’ll never be able to translate my delicate and finely honed droll notions.” In the next panel, Bliss thinks, “I’m sure he won’t understand that the comic art form is way more subtle than his blunt-force humor.” The team collaborated for a year and created 150 cartoons featuring an array of topics, “from dogs and cats to outer space and art museums.” A witty creation of a bovine family sitting down to a gourmet meal and one of Dumbo getting his comeuppance highlight the duo’s comedic talent. What also makes this project successful is the team’s keen understanding of human behavior as viewed through their unconventional comedic minds.

Pub Date: Nov. 17, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-250-26289-9

Page Count: 272

Publisher: Celadon Books

Review Posted Online: Aug. 30, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Sept. 15, 2020

ART & PHOTOGRAPHY | GENERAL NONFICTION | BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | ENTERTAINMENT, SPORTS & CELEBRITY

More by Steve Martin

by Steve Martin ; illustrated by Harry Bliss

by Steve Martin

by Steve Martin & illustrated by C.F. Payne

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

New York Times Bestseller

CINEMA SPECULATION

by Quentin Tarantino ‧ RELEASE DATE: Nov. 1, 2022

A top-flight nonfiction debut from a unique artist.

The acclaimed director displays his talents as a film critic.

Tarantino’s collection of essays about the important movies of his formative years is packed with everything needed for a powerful review: facts about the work, context about the creative decisions, and whether or not it was successful. The Oscar-winning director of classic films like Pulp Fiction and Reservoir Dogs offers plenty of attitude with his thoughts on movies ranging from Animal House to Bullitt to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to The Big Chill . Whether you agree with his assessments or not, he provides the original reporting and insights only a veteran director would notice, and his engaging style makes it impossible to leave an essay without learning something. The concepts he smashes together in two sentences about Taxi Driver would take a semester of film theory class to unpack. Taxi Driver isn’t a “ paraphrased remake ” of The Searchers like Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc? is a paraphrased remake of Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby or De Palma’s Dressed To Kill is a paraphrased remake of Hitchcock’s Psycho . But it’s about as close as you can get to a paraphrased remake without actually being one. Robert De Niro’s taxi driving protagonist Travis Bickle is John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards. Like any good critic, Tarantino reveals bits of himself as he discusses the films that are important to him, recalling where he was when he first saw them and what the crowd was like. Perhaps not surprisingly, the author was raised by movie-loving parents who took him along to watch whatever they were watching, even if it included violent or sexual imagery. At the age of 8, he had seen the very adult MASH three times. Suddenly the dark humor of Kill Bill makes much more sense. With this collection, Tarantino offers well-researched love letters to his favorite movies of one of Hollywood’s most ambitious eras.

Pub Date: Nov. 1, 2022

ISBN: 978-0-06-311258-2

Page Count: 400

Publisher: Harper/HarperCollins

Review Posted Online: Oct. 31, 2022

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2022

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | ENTERTAINMENT, SPORTS & CELEBRITY | GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | GENERAL NONFICTION

SEEN & HEARD

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

REVIEW: Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative by Melissa Febos

April 7, 2022.

Reviewed by Michelle Bowdler

Febos states in her author’s note that Body Work is “not a craft book in the traditional sense.” It is not prescriptive or didactic about what any one writer must do or that there is one way to succeed. Instead, Febos has a conversation with us about the ways in which writing has been incorporated into all aspects of her life and the things she has learned over many years.

Body Work seamlessly offers an insight into the author’s creative processes as it invites the reader to explore their own. Because of this juxtaposition, I learned many important concepts in this stunning book, and never for a moment felt dashed by them. This is more remarkable than it sounds. Too often in reading craft books, one is in awe of how someone whose work they admire approaches their art yet feels discouraged that they could ever write as compellingly.

Quite the opposite lessons were true in reading Body Work . Febos leaves ample room for readers to partake of her insights and move forward in their own unique ways. In twelve-step programs, the expression “take what you like and leave the rest behind” also applies here. Febos’s ego is decidedly absent from the discourse — a true teacher, the best kind. When I got to the last page and closed the book with a sigh of admiration, I realized how optimistic I felt: worthy of attending to my voice and the subjects I wanted to explore.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that writers can be insecure and too often compare ourselves to others, with literary awards, “best of” lists, residencies and fellowships celebrated daily on social media. Febos — no stranger to these accolades — gently encourages self-reflection and a trust of one’s own artistic development. As a result of her willingness to show vulnerability, normalizing it for others and gently challenging us to reconsider our assumptions, I found myself able to face a writer’s block I’d been fighting. For weeks after reading this book, I noticed an absence of judgment and self-criticism during my writing time and was able to produce pages without dread or exhaustion overwhelming me.

I have my own relationship to traditional craft books and instruction. I suppose most writers do. While I had hoped to have a career in writing after graduating from college, an overwhelming trauma in my early twenties (which became the subject of the book I would finally write 30 years later) left me unable to pursue this dream. By the time my nervous system recalibrated, I had moved away from artistic expression and abandoned my earlier aspirations.

In my forties, I started writing again. When I complained to a friend how lost I felt, she sent me Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird . That book was instrumental in providing me with a next step. I worried less about the quality of my “shitty first drafts” and instead focused on getting my thoughts on the page little by little, bird by bird. A few years later, I began an intensive nonfiction program for nontraditional writers. My instructor was Alex Marzano-Lesnevich, and the first reading they assigned was Vivian Gornick’s The Situation and the Story . From that book, I learned more basic tenets. Alex’s classes were laden with craft lessons, and I needed them all, especially what Alex modeled as a teacher in class: respect, honesty and generosity to fellow writers and self-compassion. While writing is a creative and seemingly solitary endeavor, we have much to learn from authors and instructors who have an open hand as they teach. Febos falls into that category.

There are specific notes of brilliance and insight in each chapter. I was especially taken with the analysis in the first chapter, “In Praise of Navel Gazing , ” which counters the notion that writing about one’s life is self-indulgent, uninteresting, and too often applied to those who are marginalized in society as a tool to diminish their voices and prevent movement on social justice issues.

“Mind Fuck” gives us several insights into writing about sex. Febos states, “My whole practical thesis around the craft of writing a sex scene is that it is exactly the same as any other scene.” The chapter offers a feminist analysis of what makes writing about sex difficult for writers. Febos offers concrete strategies for getting past the belief that the topic is too challenging to get right.

“A Big Shitty Party” offers guidance on ways to be thoughtful and act with integrity when real people are characters in your work. My favorite of her many insights is that “cruelty rarely makes for good writing” and that it is not contrary to making art to consider the impact of one’s words on others. Throughout Body Work , Febos includes several references to the work of other writers, philosophers, mental health professionals and more. This single book provides an exhaustive reading list that would benefit a writing student for years.

The books, essays, and instruction I most value are the rare ones that make it abundantly clear that one does not need to suffer to become a better writer. Febos’s book is smart but it is also compassionate. The rarity of that combination has a kind of magic to it. Perhaps a different frame, in fact, will produce several new voices unafraid and willing to stand by their work and the subjects they choose to write about. There is a kind of grace in the immersive experience of reading Body Work and it will find its place on my bookshelf, in a location where it is easy to grab anytime I need to hear Febos’ voice reminding me to carry on in a way that is value laden, kind and intentional.

Share a Comment Cancel reply

Contributor updates.

Alumni & Contributor Updates: Early 2024

Contributor Updates: Fall 2023

Contributor & Alumni Updates: Spring 2023

Contributor Updates: Spring 2022

Toni Tileva

Book Review: Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative by Melissa Febos

My review for the Washington Independent Review of Books

Melissa Febos’ latest essay collection, Body Work , is “not a craft book in the traditional sense,” she states. Nor is it a flowery ode to the writer’s life. Instead, it’s a practical, clear-eyed take on the intimate (and intricate) connection between our bodies and our bodies of work. Throughout, Febos beautifully narrates the ways in which writing is “integrated into the fundamental movements of life,” asking readers to go beyond writing about their lives to writing their lives.The author, whose previous works include Whip Smart , Abandon Me , and Girlhood , is a keen social critic, and she makes a cogent argument as to why women’s writing about trauma has been dismissed as unartistic, trite, and self-indulgent:

“Resistance to memoirs about trauma is always in part a resistance to movements of social justice.”

Indeed, while male navel-gazing has been valorized as the kindling for many a Great American Novel, when the introspection comes from women, it is scorned as so much whining no one wants to hear about yet again. (No wonder the words “histrionics” and “hysteria” sound so similar.) Febos makes an impassioned defense of self-reflection as a subversive act that personifies the notion “the personal is political.” Further, the freedom it creates benefits not just the writer but society. From it, we all wrest a bit more license to be honest about our truths.

Her essays are well researched, and much of the excitement here comes from the way in which she curates writing from Native and other non-mainstream voices. In “In Praise of Navel Gazing,” Febos discusses the work of social psychologist James Pennebaker, who found that writing about trauma is healing. She also examines how her “own internalized sexism” shaped her view of what a “real” writer does — craft fiction in the traditional American sense. This essay made me think about similar criticisms leveled against actors for “playing themselves” and thus “not acting.”

As you might guess, her chapter on how to write about sex is less about the mechanics and more about refusing to be shamed into silence. Her inclusion of an Audre Lorde essay on what sex actually is — and it’s not just sex — is especially well developed. When someone in an audience asks Febos if she feels any shame writing about the act, she responds, “I am shameless.” But shameless is not the same as vulgar or vacuous. Rather, writing about sex “might free me from shame and replace the onus of change onto the society in which we live.”

Even though Body Work is not meant to be a manual on memoir writing, it offers a useful, nuanced take on many issues that come up when tackling any sort of nonfiction. The third essay, “A Big Shitty Party,” explores writing about other people — a thorny subject faced by journalists and anthropologists alike. “It is profoundly unfair,” asserts Febos, “that a writer gets to author the public version of a story.” It is moments like this where her vulnerability and thoughtfulness are truly illuminating.

Febos also discusses ways in which writers can strengthen a story by taking a “casualties be damned, this is my artistic vision” approach or, conversely, by declining to add something “when a detail felt cruel.” She is never reckless in her own story-making; this is not slash-and-burn truth-telling. Rather, she explores how one can stay true to their recounting of an event while maintaining care for those woven into it.

The must-read Body Work is a captivating, eloquent paean to the power of working through a “pain that has been given value by the alchemy of creative attention.” In its pages, Melissa Febos posits self-appraisal as a brave act that is both intensely personal and also communal. “The only way to make room is to drag all our stories into that room,” she writes. “That’s how it gets bigger.”

Ph.D. Cultural Anthropology, Bulgarian, writer, cruciverbalista, lexicon-drunk. Mischief, Mayhem, Mangia!

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Suggestions for Kids

- Fiction Suggestions

- Nonfiction Suggestions

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

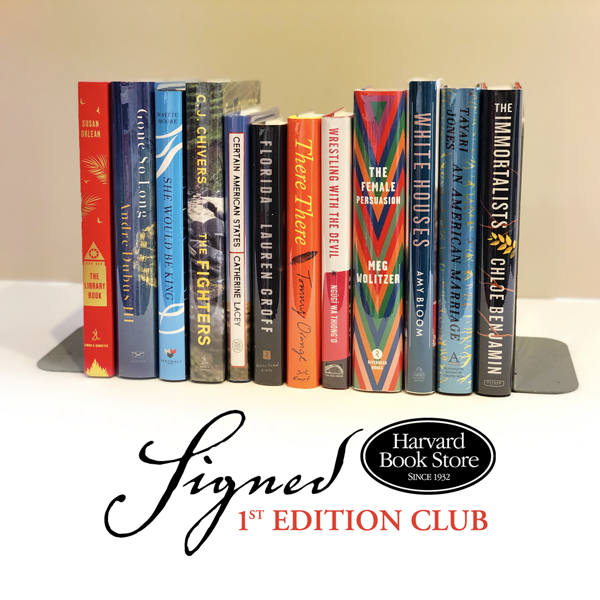

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Harvard Square Book Circle

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative

Memoir meets craft masterclass in this “daring, honest, psychologically insightful” exploration of how we think and write about intimate experiences—“a must read for anybody shoving a pen across paper or staring into a screen or a past" (Mary Karr)

In this bold and exhilarating mix of memoir and master class, Melissa Febos tackles the emotional, psychological, and physical work of writing intimately while offering an utterly fresh examination of the storyteller’s life and the questions which run through it. How might we go about capturing on the page the relationships that have formed us? How do we write about our bodies, their desires and traumas? What does it mean for an author’s way of writing, or living, to be dismissed as “navel-gazing”—or else hailed as “so brave, so raw”? And to whom, in the end, do our most intimate stories belong? Drawing on her own path from aspiring writer to acclaimed author and writing professor—via addiction and recovery, sex work and academia—Melissa Febos has created a captivating guide to the writing life, and a brilliantly unusual exploration of subjectivity, privacy, and the power of divulgence. Candid and inspiring, Body Work will empower readers and writers alike, offering ideas—and occasional notes of caution—to anyone who has ever hoped to see themselves in a story.

There are no customer reviews for this item yet.

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore

© 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved

Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected]

View our current hours »

Join our bookselling team »

We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily.

Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm

Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual.

Map Find Harvard Book Store »

Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy »

Harvard University harvard.edu »

- Clubs & Services

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative

Embed our reviews widget for this book

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

Book Review: Body Work by Melissa Febos

By Sam Paul Posted on 5.18.22

Melissa Febos has made a career out of telling her own story. Her work is deeply personal, sometimes painful, and always resonant. Her memoirs and essays stand out even beyond the import of her experiences and her talent because they are always interwoven–almost bursting–with poetic and philosophical references and insights that help connect her own experiences to universal ones. Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative , is no different. I saw this book categorized somewhere as a craft memoir. As such, I anticipated that it would be centered somehow on instruction, something I was eager for from a writer I so clearly admire. What I read was something entirely unexpected, and also wonderful. Body Work is at a times a treatise, at times a meditation on personal writing, and at times Febos’s intellectual autobiography.

Febos tells the story of her writing life, the difficulties of portraying real people, the hard work of finding the truest and best story among the many versions of the stories we tell ourselves. More than that, she stands up for memoir, which is often derided as unserious or self indulgent–in part, she argues, due to its categorization as a feminine art form. The first essay, “In Praise of Navel-Gazing,” takes on these denigrations of the form and tells the story of how she was able to dismiss them and embrace personal writing as political, as intellectual, as worthy–and, as the title claims, radical.

“Resistance to the lived stories of women, and those of all oppressed people, is a resistance to justice,” Melissa Febos

Silencing stories of the oppressed is of service to their oppressors and silencing stories of people recounting trauma is of service to its perpetrators. While, revealing our pasts–grappling with and drawing insights from them in the process–is of service not just to the person writing, but to the greater collective.

“Transforming my secrets into art has transformed me,” Febos says. “I believe that stories like these have the power to transform the world. That is the point of literature, or at least that’s what I tell my students. We are writing the history that we could not find in any other book. We are telling the stories that no one else can tell, and we are giving this proof of our survival to each other.”

These threads are pulled, and tangled and teased out throughout the book. Febos explores narrative’s place in personal healing, the deep, long-held human need to share our stories–as a form of therapy, political activation, and a religious rite. In psychotherapy, she argues, finding and telling the story of a trauma is necessary to heal it. Confession is also a step towards redemption–as she explores in the text of the Mishneh Torah in the book’s final essay, “The Return.”

But not all trauma narratives or confessional stories are art. What makes a personal story a work of art–or at least a good one, Febos argues–is the writer’s ability to gain and transmit their insight. Just as writing about and processing a trauma helps the writer to transform their experiences, it is the resulting understanding and self awareness that allows their writing to transcend them and to touch upon something beyond the particulars of their personal circumstances. This is something Febos does expertly when writing about her own artistic history.

I read this book over the course of 24 hours, and finished feeling exhilarated and inspired. Febos portrays writing our stories as an urgent act, an act of completion, a primordial urge, and a return to self. As a reader, this book was a revelation. As a writer, it was a call to action, an incitement. In Body Work , Febos does more than defend navel-gazing or self reflection, she champions it. This book is a call to arms.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Get the Latest on IG

Follow us on instagram @yourfeministbookclub

Get into the loop

Want to get a heads up on the book of the month before anyone else? Want to be on the VIP list for special offers and deals? Well, get on the list and you’ll be officially in the FBC loop!

Website by FirstTracks

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

Hilde ostby's memoir 'my belly' traces the root of body image issues and self-loathing.

Ayesha Rascoe

Self-loathing because of our looks can be second-nature for many of us. NPR's Ayesha Rascoe talks with Hilde Ostby about her memoir, "My Belly," which examines what's behind that feeling.

AYESHA RASCOE, HOST:

Norwegian writer Hilde Ostby says she's never entered a room without thinking about her belly. She can't stand it.

HILDE OSTBY: It should be flat, completely flat, no bulks whatsoever. That's the goal for, I think, a lot of women.

RASCOE: A hard to reach goal, which can translate into a constant sense of personal failure. So Hilde Ostby decided to really examine why she spent most of her adult life hating how she looked. Her new short book is titled "My Belly."

OSTBY: The book started when I was 45 years old, and I tried to sum up my life to that point. And then I realized that I'd done a lot of things, like I do yoga. I love to do yoga. I love my child. So I've been talking to my child and hugging my child. But more than that, I've spent 30 of those 45 years hating my belly. And then I started to investigate, and I found out that this is normal. It's more normal than not.

RASCOE: How do you think you develop this loathing? In the book, I found it interesting - it wasn't like you were someone who was - like, as a kid who was being told you have to look a certain way or anything like that.

OSTBY: Yeah. It was surprising for me too because my dad was a professor in philosophy. What I did as a child was read and write. I've always wanted to be a writer. I never wanted to be a model (laughter). So it shocked me, really, how much all of these thoughts had snuck into my mind. I tried to read Roald Dahl's books for my daughter, and suddenly realized that all the bad characters in Roald Dahl are heavy. So it's kind of - it's part of a culture so ingrained that it's difficult to really find out exactly where it's from because it's everywhere.

We have a phobia of fat in our society that is - it's sick. I was anorexic for several years, and I was extremely thin, and I hated my belly then. I was very heavy. I hated my belly then. I have been what society calls normal and then I also hated my belly. It's very few incidents where I didn't hate my belly. And then when you realize that, how shallow that is, you realize that the one and only thing that is important for your health is the - your mental health.

RASCOE: That was interesting that you pointed out that even when you were thin, you weren't happy. I remember when I was much thinner - I was kind of underweight as a kid - I still wasn't happy with my stomach because I wanted it to look like the singer, you know, back in the day, Aaliyah. She had the flattest stomach. And even when I was thin, I thought I had a pooch. It's a very weird thing that we take in on ourselves. It's never good enough. It's never going to be good enough.

OSTBY: No. And this cause discomfort in your own body. I tried to get to the bottom of that, and that was when I found the research of Dr. Vincent Felitti. He set up a diet clinic in San Diego in 1985, and he started to diet people that were morbidly obese. And during that process, he noticed that a lot of people just fell out of his program. So then he started interviewing people. He talked to 200 of his former clients to find out why they dropped out of his program, and he talked to them about their lives. And then he found out that they have all these extremely traumatic experiences behind them, and food was just a way of solving a much bigger problem. So Vincent Felitti made a list of childhood trauma, and he found that the more of these adverse childhood experiences you have had, the more likely you are to develop an eating disorder or drug addiction. Or it's also linked to heart disease, depression, autoimmune disease and cancer even.

And I found out I have five of those traumas. One of them is that I was raped when I was 15, and that was the same exact time that I developed my eating disorder. And that isn't a coincidence. That is the normal. It's 20% of women in Norway have been raped. So why don't we see the connection here, how we hate our bodies, how the commercial system just feeds off this self-hatred? You feel uncomfortable when you go and buy a dress, or you go on a diet to kind of alleviate the pain of feeling so uncomfortable. But we have to get to the root of the problems.

RASCOE: I'm so sorry that you went through that. Did learning about this research change how you thought about yourself? Did it make you have more grace for yourself - anger at society, but more grace for yourself?

OSTBY: Yes. But then it's an ongoing process. I need to unlearn that self-hatred, and that takes a lot of time. So I really have to - I try to read my own book...

OSTBY: ...To remind myself of what I really think about this because it sneaks back in into my mind. But the things I do to kind of feel more happy with my own body is to be more playful. I started boxing. And I also go to this ballet class, and I'm really terrible at it.

OSTBY: And I laugh at myself, and I have fun with it. And last time I went to this ballet class, I just stood in front of all of these young, very thin women, and I thought, I'm going to show you my ballet. You're going to see my body, and you're going to think it's not a big deal. You can have fun with your body.

RASCOE: That's Hilde Ostby. Her new book is called "My Belly." Thank you so much for talking to us about it.

OSTBY: Thank you for having me. It's a pleasure.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Copyright © 2024 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

Body Work : Book summary and reviews of Body Work by Sara Paretsky

Summary | Reviews | More Information | More Books

V.I. Warshawski Novel

by Sara Paretsky

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' rating:

Published Aug 2010 464 pages Genre: Mysteries Publication Information

Rate this book

About this book

Book summary.

The enigmatic performer known as the Body Artist takes the stage at Chicago's Club Gouge and allows her audience to use her naked body as a canvas for their impromptu illustrations. V. I. Warshawski watches as people step forward, some meek, some bold, to make their mark. The evening takes a strange turn when one woman's sketch triggers a violent outburst from a man at a nearby table. Quickly subdued, the man - an Iraqi war vet - leaves the club. Days later, the woman is shot outside the club. She dies in V.I.'s arms, and the police move quickly to arrest the angry vet. A shooting in Chicago is nothing new, certainly not to V.I., who is hired by the vet's family to clear his name. As V.I. seeks answers, her investigation will take her from the North Side of Chicago to the far reaches of the Gulf War.

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews.

"Starred Review. This strong outing shows why the tough, fiercely independent, dog-loving private detective continues to survive." - Publishers Weekly "Another solid entry in a popular series." - Booklist "Paretsky plays out her trademark political and social themes not with rhetoric, but with a compelling story of lives shattered by pride, greed and fear of the unknown." - Kirkus

Author Information

- Books by this Author

Sara Paretsky Author Biography

Before there was Lisbeth Salander or Stephanie Plum, there was V.I. Warshawski. Sara Paretsky revolutionized the mystery world in 1982 when she introduced V.I. in Indemnity Only . By creating a believable investigator with the grit and the smarts to tackle problems on the mean streets, Paretsky challenged a genre in which women typically were either vamps or victims. Hailed by critics and readers, Indemnity Only was followed by nineteen more best-selling Warshawski novels. The New York Times writes that Paretsky "always makes the top of the list when people talk about female operatives," while Publishers Weekly says, "Among today's PIs, nobody comes close to Warshawski." Called "passionate" and "electrifying," V.I. reflects her creator's own passion for social justice. As a contributor ...

... Full Biography Link to Sara Paretsky's Website

Other books by Sara Paretsky at BookBrowse

More Recommendations

Readers also browsed . . ..

- Exiles by Jane Harper

- Happiness Falls by Angie Kim

- A Disappearance in Fiji by Nilima Rao

- The Last Mona Lisa by Jonathan Santlofer

- The Golden Gate by Amy Chua

- A Death in Denmark by Amulya Malladi

- Glory Be by Danielle Arceneaux

- The Kingdoms of Savannah by George Dawes Green

- One Puzzling Afternoon by Emily Critchley

- Carolina Moonset by Matt Goldman

more mysteries...

Support BookBrowse

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The Stone Home by Crystal Hana Kim

A moving family drama and coming-of-age story revealing a dark corner of South Korean history.

The House on Biscayne Bay by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

Win This Book

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

- Teen & Young Adult

- Personal Health

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $21.95 $21.95 FREE delivery: Tuesday, April 23 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $9.31

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Other Sellers on Amazon

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The Body Image Workbook for Teens: Activities to Help Girls Develop a Healthy Body Image in an Image-Obsessed World Paperback – Illustrated, December 1, 2014

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Part of series An Instant Help Book for Teens

- Print length 200 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Instant Help

- Publication date December 1, 2014

- Grade level 6 - 12

- Reading age 13 years and up

- Dimensions 8.36 x 0.51 x 9.83 inches

- ISBN-10 1626250189

- ISBN-13 978-1626250185

- See all details

Frequently bought together

More items to explore

From the Publisher

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Instant Help; Illustrated edition (December 1, 2014)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 200 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1626250189

- ISBN-13 : 978-1626250185

- Reading age : 13 years and up

- Grade level : 6 - 12

- Item Weight : 2.31 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.36 x 0.51 x 9.83 inches

- #8 in Teen & Young Adult Nonfiction on Peer Pressure

- #22 in Self-Esteem for Teens & Young Adults

- #31 in Teen & Young Adult Self-Esteem & Self-Reliance Issues

About the author

Julia v. taylor.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

A history of hypochondria wonders why we worry

In ‘a body made of glass,’ caroline crampton writes about the ways in which society has thought about diagnosis and delusion.

In the late 14th century, a spate of patients scattered across Europe developed an unusual delusion: They came to believe that their bodies were made of glass. Those suffering from this bizarre affliction were terrified of shattering — at least one of them insisted on sleeping in heaps of straw so as to prevent any mishaps. But to modern-day hypochondriacs, this archaic phobia might represent both a fear and a perverse fantasy. A glass person would be perilously breakable, but her condition would also be blissfully transparent.

The journalist Caroline Crampton often wishes that she could see her own insides. She is as desperate for knowledge of the darkest corners of her anatomy as she is terrified of her fragility. “I am a hypochondriac,” she writes in her new book, “ A Body Made of Glass: A Cultural History of Hypochondria .” “Or, at least, I worry that I am, which really amounts to the same thing.” She has suffered from this secondary malady since she was diagnosed with the primary malady of Hodgkin’s lymphoma as a teenager. After months of treatment, her doctors assured her that she was in remission — but a year later, the disease returned. Crampton beat it again, but her anxiety lingers to this day. Is her apprehension irrational?

“A Body Made of Glass” proposes that it is and it isn’t. On the one hand, Crampton often experiences symptoms that she later recognizes to be psychosomatic; on the other, her hyper-vigilance after her supposedly successful first cancer treatment enabled her to spot a suspicious lump the second time. “My fears about health are persistent and at times intrusive,” she concedes, “but they are not necessarily unwarranted.” She concludes that “diagnosable illness and hypochondria can coexist.” Although “we tend to think of hypochondria as shorthand for an illness that’s all in your head,” the people most worried about their health are very often the people who have the most reason to be.

Unfortunately, many of us have cause to brood on the indignities of embodiment. Crampton writes that “a serious illness is much easier to cope with if it can be slotted into a familiar structure with a beginning, middle, and end,” but she knows that the comforts of recovery and resolution are denied to the ever-increasing number of patients with chronic or autoimmune conditions. Like those conditions, hypochondria is “a plotless story.”

“Without a firm diagnosis for my unreliable symptoms, I am stuck in the first scene of the drama, endlessly looping around the same few lines of dialogue,” Crampton writes. “The compulsion to narrativize this experience is always there, but always thwarted.” There is no satisfying ending, no definitive interpretation of a vague pain or a mysterious twinge.

Indeed, there is no absolute agreement about what qualifies as diagnosis and what qualifies as delusion. In a society riddled with biases, credibility is not apportioned equally, and marginalized populations are often dismissed as hysterical. A host of studies have demonstrated that doctors are less likely to listen to women and non-White people, and Crampton knows that she is “taken more seriously in medical examinations” because she is White and upper middle class. The prejudice cuts both ways: Patients, too, rely on “irrelevant details like confidence, carriage, and body language” to determine whether a physician is trustworthy.

And of course, sickness itself — and therefore hypochondria — is a culturally specific construct that is always subject to revision. The catalogue of medically reputable diseases expands and contracts as research advances and outdated theories are debunked. “It is now possible to test for conditions that were previously undetectable,” Crampton writes. The novelist Marcel Proust was regarded by his contemporaries (and even his father) as deranged because he took such strenuous precautions to avoid fits of coughing, but contemporary medicine might have vindicated his concerns. One century’s hypochondriac is another’s confirmed patient.

In 1733, the physician George Cheyne described hypochondria as a “disease of civilization.” According to Crampton, he meant that it was “a consequence of the excesses of an imperial and consumerist society that had abandoned the simplicity of earlier human existence in favor of an indulgent diet and inactive lifestyle,” but hypochondria is also a disease of civilization because it increases as our knowledge does. The more we understand about the myriad ways our bodies can fail, the more we have to fear.

Because the boundaries delineating hypochondria from verifiable sickness are not fixed, it is difficult to pin down either notion with precision. Crampton acknowledges that her topic of choice “resists definition, like oil sliding over the surface of water.” She is right that hypochondria is a shifting target, but her refusal to venture even a provisional characterization can make for frustrating reading.

“A Body Made of Glass” is a product of impressively thorough research, but it is sometimes circuitous and digressive to the point of frenzy. It blends memoir and literary criticism with micro-histories of subjects of varying relevance, among them the emergence of quack medicine and the medieval theory of the humors.

“Hypochondria” is an old word but a relatively new concept, and it is not always clear whether Crampton’s book traces the history of the phenomenon or the history of the term. Sometimes, her concern is etymological: She informs us that the word first appeared in the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of medical tracts produced and disseminated in ancient Greece, where it referred to “the place where hard ribs give way to soft abdomen.” Elsewhere, however, Crampton discusses not language but terror in the face of mortality. Her wide-ranging reflections touch on such eminences as John Donne, Molière and Charles Darwin, all of whom had both palpable ailments and debilitating anxiety about their palpable ailments. (It’s difficult to have the former without the latter, it turns out.)

Still, “A Body Made of Glass” is full of fascinating forays. If it is hard to read for its claims or conclusions, it can still be read for its many sobering observations about sickness — a misfortune that will eventually befall even the heartiest among us. After all, as Crampton darkly notes, “hypochondria is merely the human condition with the comforting fictions stripped away. Whether we choose to think about it all the time or not, we are all just one freak accident away from the end.”

Becca Rothfeld is the nonfiction book critic for The Washington Post and the author of “All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess.”

A Body Made of Glass

A Cultural History of Hypochondria

By Caroline Crampton

Ecco. 321 pp. $29.99

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

'Senseless act of violence': Alabama mother of 4 kidnapped, found dead in car; man charged

Authorities in Alabama arrested a man and charged him with capital murder in the kidnapping and death of Nakita Chantryce Davidson, who was found dead in her car on Friday.

Cedric Dewayne Robertson, 37, of Birmingham, Alabama was arrested Friday evening after detectives with the Birmingham Police Department obtained a warrant Thursday from the Jefferson County District Attorney’s Office. Robertson was later charged with "capital murder committed during a kidnapping," and is currently in custody at the Jefferson County Jail, the DA Office said Monday.

Victim was found dead in a car, police say

Davidson, 40, a mother of four, as per a GoFundMe Account set up for her funeral expenses, was found dead shortly before 3:20 p.m. Friday in a burgundy vehicle in a wooded dead-end area, Birmingham Police said in a news release Saturday .

An investigation into her kidnapping began early the previous day after officers responded to a call of a two-vehicle accident, a little after 2 a.m. Thursday.

"When officers arrived on the scene, they observed one vehicle at the location," police said. "Officers also observed evidence of a violation crime."

At the time, police said that they believe that suspect had "shot the victim, placed her inside her vehicle and left the scene."

Suspect arrested a mile from deceased's location

A warrant for Robertson's arrest for kidnapping was issued and the police had sought the public's help in locating him, warning that they believe the suspect to be "armed and dangerous."

Robertson was eventually arrested Friday evening around 6:40 p.m., about a mile from where Davidson's car and body were found.

It is not immediately clear when the suspect will be arraigned or presented in court. The DA's office did not immediately respond to USA TODAY's request for an update on the case.

'Targeted' killing: UPS driver in Birmingham, Alabama shot dead leaving work, police say

Accused was victim's boyfriend, reports state

While authorities did not specify if Davidson was known to Robertson, AL.com, citing court records reported that the accused was Davidson's boyfriend. The records indicated Robertson was a convicted felon who purposely crashed into the victim's vehicle and shot her before putting her into the trunk of her car's vehicle and driving away in it, the media outlet reported. The suspect's own vehicle and cell phone were found at the site of the car crash.

One of Davidson's shoes, a pink Nike sneaker, was also found at the site of the car crash, that helped in identifying the victim, AL.com reported.

Davidson’s brother, Laderrius Swain, told AL.com that his sister had been dating Robertson for less than a year and was planning to end things with him when she was killed.

“Her plan was to get away from him,’’ Swain told the media outlet. “That’s what she was trying to do that night.”

Swain, who has set up the GoFundMe for Davidson's funeral arrangements , wrote on the page: "Her life was tragically cut short on 4/12/24 due to a senseless act of violence leaving four children without their mother."

A date for the funeral has not yet been set.

Saman Shafiq is a trending news reporter for USA TODAY. Reach her at [email protected] and follow her on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter @saman_shafiq7.

The Science of 3 Body Problem, Explained

- Scientists grapple with chaotic orbits in the three-sun solar system, facing alien deification and threats in 3 Body Problem on Netflix.

- Audacious science questions like amplifying radio waves with the sun and nanofiber tech arise, blending real-world physics with entertainment.

- Cryogenically freezing brains for space travel and remaking bodies poses challenges in hard sci-fi series where scientific ideas take the spotlight.

3 Body Problem sucked viewers into its orbit from the moment it dropped on Netflix late last month. Joining the ranks of other Netflix sci-fi originals , 3 Body Problem stays true to the format with its timeline-jumping, convoluted plot, and heady concepts rooted in physics, cosmology, and technology. Throw in a bunch of dazzling interstellar montages, gore, and plenty of "will-they-won't-they" romance as a palate cleanser, and fans have found themselves motivated for more reasons than one to keep up.

3 Body Problem is a show where a grasp of these complex scientific concepts in itself is seen as a threat by the alien antagonists, which they try to correct by deifying themselves, disrupting the progress of the Oxford Five, and even getting them killed outright.

It's a relief, then, that the writers didn't gatekeep these concepts either, with Vulture reporting the TV adaptation to be more accessible than the once-thought "unadaptable" Liu Cixin trilogy . Still, many new fans have flocked to the Internet to learn the logic behind some of the show's more audacious scenes. For instance, what is a three-body problem, and how is it affecting the San-ti? Can the sun be used to amplify radio waves? Can nanofibers do what Auggie's weapon did? Can you cryogenically freeze just a brain? Let's explore the science behind these memorable moments from 3 Body Problem .

3 Body Problem

Release Date March 21, 2024

Cast Jess Hong, Saamer Usmani, Marlo Kelly, Rosalind Chao, Jovan Adepo

Genres Drama, Adventure, Fantasy

What Is the Three-Body Problem?

Jin (Jess Hong) and Jack (John Bradley) learn by playing the VR video game that San-ti's planet is in a three-sun solar system. When three celestial bodies (suns, planets, etc.) are in close proximity, they all exert force on each other and the orbit becomes chaotic. When it's just two celestial bodies exerting forces on each other, the objects' rotation is a lot easier to predict, i.e., stable. The San-ti's planet being specifically in a three-sun solar system means when their planet rotates around one sun, it's in a stable era. But when the force of another sun snatches it away, it wanders in that gravitational field where the planetary conditions become too extreme for life to exist. So, it fluctuates between stable and chaotic eras.

Since, like Jin says, there is no known solution to the three-body problem, none of their attempts to predict eras and save the avatar work. The San-ti IRL had already figured this out for themselves and fled to try to make their home on Earth.

3 Body Problem Review: A Slow Start Doesn't Hinder This Ambitious Hard Sci-Fi Series

Can the sun be used to amplify radio waves.

What about the epiphany that started it all: when Ye Wenjie (Rosalind Chao) realizes how to contact extraterrestrial life based on data she receives from the American scientist? The Wow! signal referenced in Episode 2 was, in fact, a real signal received in 1977 at the Ohio State University Observatory. It was remarkable because it was a surge far more powerful than the baseline, which is why it was speculated to be communication from extraterrestrials rather than the random result of a cosmic event. However, it is unlikely that we could use the sun to reply — even if that were the case.

The sun is a multilayered sphere composed mostly of plasma , ionized matter similar to a gas. The signal would have to reflect off the first layer but still pass onto the next, and reflect off of that, and so on. It would have to create a perfectly constructive interference in order to work like the amplifiers we are familiar with.

Can Nanofibers Be Used to Slice Through People?

In Episode 5, Auggie's (Eiza González) nanofiber technology was weaponized when the ship Judgment Day pulled into the Panama Canal. In real life, nanofibers do exist and can slice through just about anything! However, they currently have limitations that keep them from being mass-produced like we saw.

Nanofibers are curated and grown in a lab with molecules that are specifically designed to keep them in place as they're being built. The difficulty and cost of creating those necessary conditions as well as the rest of the production process keep them from being utilized like we saw. Everything from the weapon to the water filtration to the bulletproof garb given to Saul (Jovan Adepo) are all realistic applications, though.

Can You Cryogenically Freeze a Brain But Remake a Body?

Will (Alex Sharp) volunteers to save the day by having his brain removed from his body, put on ice, and sent into space on the Project Staircase probe. The hope is that the San-ti will reform his body, motivated by a desire to understand humans and a trust for the man who said he wouldn't pledge his loyalty to humanity. Then, once reformed, he can gather information.

It is possible to extract a human brain and preserve it under those conditions, but we don't have the technology to recreate a human from that brain. The task force is operating under the assumption that the San-ti do.

Netflix's 3 Body Problem Creators Promise a Mind-Blowing Season 2

3 Body Problem stamps itself as a series that many would consider "hard sci-fi," both in The Three-Body Problem book series and in the Netflix adaptation. Hard sci-fi is characterized by scientific speculation that is grounded in reality. Although the execution here has garnered mixed reviews , one might argue that the science can never be completely accurate, or "hard." 3 Body Problem and the genre as a whole are compelling simply because the prioritization of and passion for scientific ideas is as strong as the prioritization of and passion for storytelling.

3 Body Problem is available to stream on Netflix. Check out the trailer below:

Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative

- By Melissa Febos

- Reviewed by Antoaneta Tileva

- August 5, 2022

There’s strength in telling your own story.

Melissa Febos’ latest essay collection, Body Work , is “not a craft book in the traditional sense,” she states. Nor is it a flowery ode to the writer’s life. Instead, it’s a practical, clear-eyed take on the intimate (and intricate) connection between our bodies and our bodies of work. Throughout, Febos beautifully narrates the ways in which writing is “integrated into the fundamental movements of life,” asking readers to go beyond writing about their lives to writing their lives.

The author, whose previous works include Whip Smart , Abandon Me , and Girlhood , is a keen social critic, and she makes a cogent argument as to why women’s writing about trauma has been dismissed as unartistic, trite, and self-indulgent:

“Resistance to memoirs about trauma is always in part a resistance to movements of social justice.”

Indeed, while male navel-gazing has been valorized as the kindling for many a Great American Novel, when the introspection comes from women, it is scorned as so much whining no one wants to hear about yet again. (No wonder the words “histrionics” and “hysteria” sound so similar.) Febos makes an impassioned defense of self-reflection as a subversive act that personifies the notion “the personal is political.” Further, the freedom it creates benefits not just the writer but society. From it, we all wrest a bit more license to be honest about our truths.

Her essays are well researched, and much of the excitement here comes from the way in which she curates writing from Native and other non-mainstream voices. In “In Praise of Navel Gazing,” Febos discusses the work of social psychologist James Pennebaker, who found that writing about trauma is healing. She also examines how her “own internalized sexism” shaped her view of what a “real” writer does — craft fiction in the traditional American sense. This essay made me think about similar criticisms leveled against actors for “playing themselves” and thus “not acting.”

As you might guess, her chapter on how to write about sex is less about the mechanics and more about refusing to be shamed into silence. Her inclusion of an Audre Lorde essay on what sex actually is — and it’s not just sex — is especially well developed. When someone in an audience asks Febos if she feels any shame writing about the act, she responds, “I am shameless.” But shameless is not the same as vulgar or vacuous. Rather, writing about sex “might free me from shame and replace the onus of change onto the society in which we live.”

Even though Body Work is not meant to be a manual on memoir writing, it offers a useful, nuanced take on many issues that come up when tackling any sort of nonfiction. The third essay, “A Big Shitty Party,” explores writing about other people — a thorny subject faced by journalists and anthropologists alike. “It is profoundly unfair,” asserts Febos, “that a writer gets to author the public version of a story.” It is moments like this where her vulnerability and thoughtfulness are truly illuminating.

Febos also discusses ways in which writers can strengthen a story by taking a “casualties be damned, this is my artistic vision” approach or, conversely, by declining to add something “when a detail felt cruel.” She is never reckless in her own story-making; this is not slash-and-burn truth-telling. Rather, she explores how one can stay true to their recounting of an event while maintaining care for those woven into it.

The must-read Body Work is a captivating, eloquent paean to the power of working through a “pain that has been given value by the alchemy of creative attention.” In its pages, Melissa Febos posits self-appraisal as a brave act that is both intensely personal and also communal. “The only way to make room is to drag all our stories into that room,” she writes. “That’s how it gets bigger.”

Antoaneta Tileva is a Bulgarian transplant who has lived in the DC area since she arrived here at age 12. Besides being first-generation, she is also a first-generation Ph.D. in cultural anthropology. She is a mean cruciverbalista and a not-so-mean feminista.

Support the Independent by purchasing this title via our affliate links: Amazon.com Powell's.com Or through Bookshop.org

Book Review in Non-Fiction More

This Much Country: A Memoir

By kristin knight pace.

The author ably harnesses an adventure but often fails to keep the reader on her side.

- Non-Fiction ,

- Biography & Memoir ,

The Crisis of the Middle-Class Constitution: Why Economic Inequality Threatens Our Republic

By ganesh sitaraman.

A law professor warns of looming danger from financial imbalance.

- Business & Economics ,

Advertisement

A Body Made of Glass: Unflinching interrogation of hypochondria

This exploration of the condition and its evolution leads to fascinating cultural observations.

Caroline Crampton's investigation reaches beyond her private experience. Photograph: Darren Kemper/Corbis/VCG/Getty

If you were hoping for Caroline Crampton’s book on hypochondria to provide some clarifying definition of the term, you may find yourself a little disappointed. It is through the exploration of the unanswerable that Crampton invites us into her inner world, where she remains haunted by the duality of being sick and well in each waking moment.

In Crampton’s view, hypochondria breeds on the “doubt inherent in modern medicine”. Since certainty is a condition that has always been irreconcilable with science and medicine, hypochondria has persisted, from its roots as a purely anatomical term in the fifth century BC — denoting the upper third of the abdomen — to the present day.

In one poetic attempt to encapsulate the essence of the condition, she describes it as “being homesick for the body that you are still in”. This description feels all the more poignant when Crampton reveals the origins of her own hypochondria: a diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma at 17 which, despite going into remission after a half-decade of invasive treatments, has left her hyper-conscious of “every twinge and scrape”.

In tying her own experience, as if by an invisible thread, to numerous intellectual giants and fictional characters across time, she offers us a rounder taste of her condition. She speaks of the magical thinking that permeated Joan Didion’s life in the wake of her husband’s death; the existential dread of Woody Allen’s parodied neurotic characters “forever trapped between the two possibilities” of health and terminal illness; the despair of Elizabethan poet John Donne facing his mortality during a relapsing fever; and the obsessiveness of Charles Darwin’s daily rituals aimed at controlling his fears about his degenerating body.

Cork World Book Fest turns 20

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/RJPVEH2WIBE4DFQOGZQW5BPZ3I.jpg)

Hagstone by Sinéad Gleeson: There is a lyricism to this magical and otherworldly debut novel

:quality(70):focal(3856x1468:3866x1478)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/7EF4W3OG45DA3D72EEUTLV72O4.jpg)