A Summary and Analysis of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ‘Self-Reliance’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

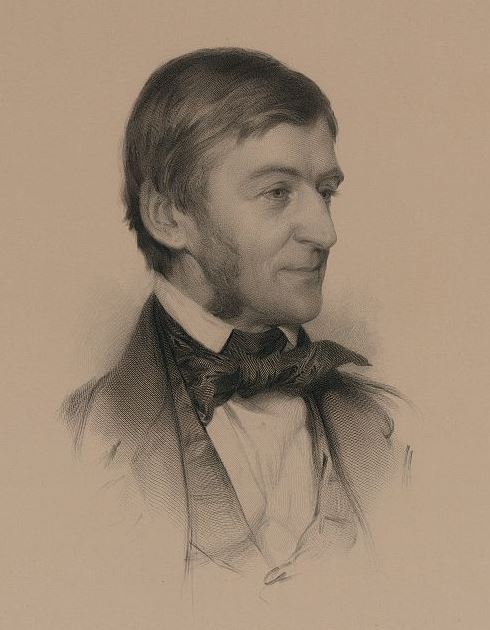

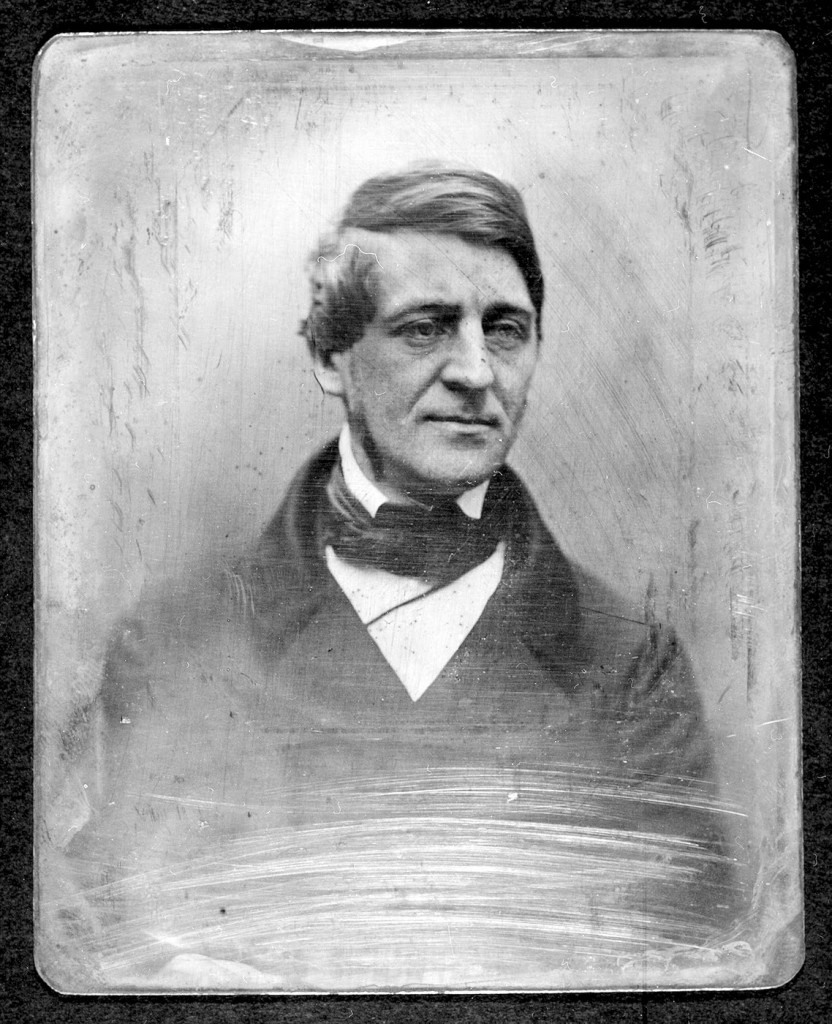

‘Self-Reliance’ is an influential 1841 essay by the American writer and thinker Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82). In this essay, Emerson argues that we should get to know our true selves rather than looking to other people to fashion our individual thoughts and ideas for us. Among other things, Emerson’s essay is a powerful rallying cry against the lure of conformity and groupthink.

Emerson prefaces his essay with several epigraphs, the first of which is a Latin phrase which translates as: ‘Do not seek yourself outside yourself.’ This axiom summarises the thrust of Emerson’s argument, which concerns the cultivation of one’s own opinions and thoughts, even if they are at odds with those of the people around us (including family members).

This explains the title of his essay: ‘Self-Reliance’ is about relying on one’s own sense of oneself, and having confidence in one’s ideas and opinions. In a famous quotation, Emerson asserts: ‘In every work of genius we recognise our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.’

But if we reject those thoughts when they come to us, we must suffer the pangs of envy of seeing the same thoughts we had (or began to have) in works of art produced by the greatest minds. This is a bit like the phenomenon known as ‘I wish I’d thought of that!’, only, Emerson argues, we did think of it, or something similar. But we never followed through on those thoughts because we weren’t interested in examining or developing our own ideas that we have all the time.

In ‘Self-Reliance’, then, Emerson wants us to cultivate our own minds rather than looking to others to dictate our minds for us. ‘Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind,’ he argues. For Emerson, our own minds are even more worthy of respect than actual religion.

Knowing our own minds is far more valuable and important than simply letting our minds be swayed or influenced by other people. ‘It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion’, Emerson argues, and ‘it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.’

In other words, most people are weak and think they know themselves, but can easily abandon all of their principles and beliefs and be swept up by the ideas of the mob. But the great man is the one who can hold to his own principles and ideas even when he is the one in the minority .

Emerson continues to explore this theme of conformity:

A man must consider what a blindman’s-buff is this game of conformity. If I know your sect, I anticipate your argument. I hear a preacher announce for his text and topic the expediency of one of the institutions of his church. Do I not know beforehand that not possibly can he say a new and spontaneous word? Do I not know that, with all this ostentation of examining the grounds of the institution, he will do no such thing? Do I not know that he is pledged to himself not to look but at one side, – the permitted side, not as a man, but as a parish minister?

He goes on:

This conformity makes them not false in a few particulars, authors of a few lies, but false in all particulars. Their every truth is not quite true. Their two is not the real two, their four not the real four; so that every word they say chagrins us, and we know not where to begin to set them right.

Emerson then argues that consistency for its own sake is a foolish idea. He declares, in a famous quotation, ‘A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.’

Instead, great men change and refine their opinions from one day to the next, as new evidence or new ideas come to light. Although this inconsistency may lead us to be misunderstood, Emerson thinks there are worse things to be. After all, great thinkers such as Pythagoras, Socrates, and even Jesus were all misunderstood by some people.

Emerson also argues that, just because we belong to the same social group as other people, this doesn’t mean we have to follow the same opinions. In a memorable image, he asserts that he likes ‘the silent church before the service begins, better than any preaching’: that moment when everyone can have their own individual thoughts, before they are brought together by the priest and are told to believe the same thing.

Similarly, just because we share blood with our relatives, that doesn’t mean we have to believe what other family members believe. Rather than following their ‘customs’, ‘petulance’, or ‘folly’, we must be ourselves first and foremost.

The same is true of travel. We may say that ‘travel broadens the mind’, but for Emerson, if we do not have a sense of ourselves before he pack our bags and head off to new places, we will still be the same foolish person when we arrive at our destination:

Travelling is a fool’s paradise. Our first journeys discover to us the indifference of places. At home I dream that at Naples, at Rome, I can be intoxicated with beauty, and lose my sadness. I pack my trunk, embrace my friends, embark on the sea, and at last wake up in Naples, and there beside me is the stern fact, the sad self, unrelenting, identical, that I fled from. I seek the Vatican, and the palaces. I affect to be intoxicated with sights and suggestions, but I am not intoxicated. My giant goes with me wherever I go.

Emerson concludes ‘Self-Reliance’ by urging his readers, ‘Insist on yourself; never imitate.’ If you borrow ‘the adopted talent’ of someone else, you will only ever be in ‘half possession’ of it, whereas you will be able to wield your own ‘gift’ if you take the time and effort to cultivate and develop it.

Although some aspects of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s argument in ‘Self-Reliance’ may strike us as self-evident or mere common sense, he does take issue with several established views on the self in the course of his essay. For example, although it is often argued that travel broadens the mind, to Emerson our travels mean nothing if we have not prepared our own minds to respond appropriately to what we see.

And although many people might argue that consistency is important in one’s thoughts and opinions, Emerson argues the opposite, asserting that it is right and proper to change our opinions from one day to the next, if that is what our hearts and minds dictate.

Similarly, Emerson also implies, at one point in ‘Self-Reliance’, that listening to one’s own thoughts should take precedence over listening to the preacher in church.

It is not that he did not believe Christian teachings to be valuable, but that such preachments would have less impact on us if we do not take the effort to know our own minds first. We need to locate who we truly are inside ourselves first, before we can adequately respond to the world around us.

In these and several other respects, ‘Self-Reliance’ remains as relevant to our own age as it was to Emerson’s original readers in the 1840s. Indeed, perhaps it is even more so in the age of social media, in which young people take selfies of their travels but have little sense of what those places and landmarks really mean to them.

Similarly, Emerson’s argument against conformity may strike us as eerily pertinent to the era of social media, with its echo chambers and cultivation of a hive mind or herd mentality.

In the last analysis, ‘Self-Reliance’ comes down to trust in oneself as much as it does reliance on oneself. Emerson thinks we should trust the authority of our own thoughts, opinions, and beliefs over the beliefs of the herd.

Of course, one can counter such a statement by pointing out that Emerson is not pig-headedly defending the right of the individual to be loudly and volubly wrong. We should still seek out the opinions of others in order to sharpen and test our own. But it is important that we are first capable of having our own thoughts. Before we go out into the world we must know ourselves , and our own minds. The two-word axiom which was written at the site of the Delphic Oracle in ancient Greece had it right: ‘Know Thyself.’

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Philosophy Break Your home for learning about philosophy

Introductory philosophy courses distilling the subject's greatest wisdom.

Reading Lists

Curated reading lists on philosophy's best and most important works.

Latest Breaks

Bite-size philosophy articles designed to stimulate your brain.

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Self-Reliance Summary (and PDF): Become Your Own Person

In his famous 1841 essay Self-Reliance, Ralph Waldo Emerson argues that society is in conspiracy against our individuality. To really live good lives, we must have the courage to resist conformity and trust the ‘immense intelligence’ of our own intuition and gut instinct.

10 -MIN BREAK

H ow can we best navigate existence? Should we go along with the conventions of society? Should we respect the prevailing traditions and opinions of the day? Or should we relentlessly carve our own paths through life?

Throughout his work, the philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 - 1882) made his answers to such questions clear, spearheading the Transcendentalist movement of mid-19th century America.

One of the key hallmarks of the Transcendentalist movement, which notably included Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau (see our reading list of Thoreau’s best books here ), is its celebration of the supremacy — even divinity — of nature.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 - 1882)

Divinity is not locked in a distant heaven, say transcendentalists; it is accessible right here in the company of the natural world.

We are thus at our best not when we conform to voices outside ourselves, but when we follow the voice within — the glimmering insight, the “immense intelligence” of our natural intuition and instincts.

Society on this view is seen as a corrupting force — it takes us away from our natural wisdom.

Emerson offers the beginnings of a path for how we might resist the pressures of society in his famous 1841 essay, Self-Reliance (access the full text of Self-Reliance as a free PDF here ), which features in my reading list of Emerson’s best books , and is a crucial contribution to Transcendentalist thought.

With eloquent, persuasive prose, Emerson fiercely defends the idea that the good life involves defying conformity, taking charge of our own existences, and living in accordance with the wisdom of the natural world.

Let’s take a look at Emerson’s essay in more detail, and see why his critique of conformity and celebration of individuality remains so acclaimed to this day.

Emerson: in works of genius, we find our own buried thoughts

E merson begins Self-Reliance by discussing a funny thing he’s observed about great works of art. Namely: that they often reflect our own buried thoughts and feelings back to us. He writes:

In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.

Emerson reflects,

Great works of art have no more affecting lesson for us than this. They teach us to abide by our spontaneous impression with good-humored inflexibility [even] when the whole cry of voices is on the other side.

In other words, if we identify our own buried thoughts and concerns in works of genius — works we celebrate and implore others to read, watch, or listen to — then why, Emerson questions, do we often lack the conviction to express or act on such thoughts ourselves?

Perhaps, Emerson laments, we push down such thoughts because they go against convention in some way, or because we feel they might embarrass or expose us if spoken aloud.

In short: because we’re worried by the judgment of others…

Thus Emerson sets up his attack on convention and conformity, within which he thinks we all hide ourselves for fear of exposing our true natures.

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 11,500+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Society is in conspiracy against our individuality

W ith its silly status games and hierarchies, society saps our confidence and self-reliance, Emerson thinks: “It loves not realities and creators, but names and customs.”

As we move through life, we must navigate pre-existing power structures and conventions, and stagger through storms of opinion on what we think, say, and do.

Confident, persuasive voices will try to convince us that this is the way; while others will shame us for daring to act differently.

But against this noise we must try to preserve our individuality, Emerson implores:

You will always find those who think they know what is your duty better than you know it. It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

While outsourcing our opinions to the crowd may be tempting, and might feel like the safer option, in doing so we only falsify ourselves, Emerson warns:

Most men have bound their eyes with one or another handkerchief, and attached themselves to some one of these communities of opinion. This conformity makes them not false in a few particulars, authors of a few lies, but false in all particulars. Their every truth is not quite true.

Of course, society will punish us for trying to steer our own course. “For nonconformity”, Emerson observes, “the world whips you with its displeasure.”

We feel pressure to act according to the expectations of others, because “the eyes of others have no other data for computing our orbit than our past acts, and we are loath to disappoint them.”

But exchanging our true selves for the comfort of the crowd is a cost we should not be willing to bear, Emerson thinks:

Your genuine action will explain itself, and will explain your other genuine actions. Your conformity explains nothing.

After all, what but mediocrity awaits us in convention and consistency?

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall.

Really living means growing and adapting, Emerson says — even if by growing and adapting we contradict our former selves, or people’s expectations of us:

Suppose you should contradict yourself; what then? …Speak what you think now in hard words, and tomorrow speak what tomorrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict everything you said today.

“What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think,” Emerson declares: “No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature.”

Being self-reliant: the ineffable intelligence of our inner nature

W e might wonder why Emerson places so much stock on our ‘inner natures’ — what does he really mean by maintaining our individuality? How might we do so?

Well, Emerson thinks we are endowed with intuition from nature, an immense ‘gut’ intelligence that trumps the fleeting fashions of opinion in society.

“We lie in the lap of immense intelligence,” he writes,

which makes us receivers of its truth and organs of its activity. When we discern justice, when we discern truth, we do nothing of ourselves, but allow a passage to its beams. If we ask whence this comes, if we seek to pry into the soul that causes, all philosophy is at fault. Its presence or its absence is all we can affirm.

We cannot necessarily articulate it, but most of us will be familiar with having a ‘feeling in our gut’ or ‘call of conscience’. It is this kind of intuition that Emerson thinks we should trust much more than public opinion.

We are part of nature, yet the opinions of society corrupt us away from nature:

Man is timid and apologetic; he is no longer upright; he dares not say ‘I think,’ ‘I am,’ but quotes some saint or sage… These roses under my window make no reference to former roses or to better ones; they are for what they are… [but] man postpones or remembers; he does not live in the present, but with reverted eye laments the past, or, heedless of the riches that surround him, stands on tiptoe to foresee the future…

We will not be happy or strong until, like the examples in nature all around us, we live in the present without second-guessing ourselves, “above time”, self-reliant .

Do not imitate: entrust yourself to be your own person

E merson argues our best acts will never come through imitation, for we will never surpass those on whom we model ourselves.

It is only through really, truly, authentically being ourselves that we can live lives of which we can be proud — lives that take us beyond dreary mediocrity. Emerson writes:

Insist on yourself; never imitate. Your own gift you can present every moment with the cumulative force of a whole life’s cultivation; but of the adopted talent of another, you have only an extemporaneous, half possession.

For, indeed, he questions, “where is the master who could have taught Shakspeare?”

Every great person is unique , Emerson thinks. It is through embracing your uniqueness that you shall succeed:

Abide in the simple and noble regions of thy life, obey thy heart, and thou shalt reproduce the Foreworld again.

Make authenticity the foundation of your relationships

B ut what of others? If living only according to our own intuition for how we should live, does Emerson’s philosophy mean selfishness?

No, Emerson says, it means authenticity: seeking to bloom into the best versions of ourselves — not what society claims is best for us; seeking to be human beings of value — not creatures of conformity.

“Live no longer to the expectation of these deceived and deceiving people with whom we converse,” Emerson writes. “Say to them,

O father, O mother, O wife, O brother, O friend, I have lived with you after appearances hitherto. Henceforward I am the truth’s. Be it known unto you that henceforward I obey no law less than the eternal law... I shall endeavor to nourish my parents, to support my family, to be the chaste husband of one wife, — but these relations I must fill after a new and unprecedented way. I appeal from your customs. I must be myself. I cannot break myself any longer for you, or you. If you can love me for what I am, we shall be the happier. If you cannot, I will still seek to deserve that you should. I will not hide my tastes or aversions…

We still strive to be the best we can be, and to respect and honor our loved ones, but through actions and behaviors that we command, not that are commanded for us.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

Indeed, to be the best people we can be, we must no longer bury ourselves under layers of convention; it would be better for all of us if we could be sincere.

We might not all agree with one another, but we can respect each other’s right to disagree in the name of authenticity:

If you are noble, I will love you; if you are not, I will not hurt you and myself by hypocritical attentions. If you are true, but not in the same truth with me, cleave to your companions; I will seek my own. I do this not selfishly, but humbly and truly. It is alike your interest, and mine, and all men’s, however long we have dwelt in lies, to live in truth. Does this sound harsh today? You will soon love what is dictated by your nature as well as mine, and, if we follow the truth, it will bring us out safe at last.

Perhaps such defiance may make us worry about upsetting our loved ones. “Yes,” Emerson concedes,

but I cannot sell my liberty and my power, to save their sensibility. Besides, all persons have their moments of reason, when they look out into the region of absolute truth; then will they justify me, and do the same thing.

People may think that by rejecting convention we are defying all codes of conduct, but such people are misguided; we are now simply living in line with the immense intelligence of nature, not the fleeting opinions of society:

And truly it demands something godlike in him who has cast off the common motives of humanity, and has ventured to trust himself for a taskmaster. High be his heart, faithful his will, clear his sight, that he may in good earnest be doctrine, society, law, to himself, that a simple purpose may be to him as strong as iron necessity is to others!

Living according to your own authority

T hough we may begin our lives living according to the conventions of the day or the expectations of others, there comes a time where the scales fall from our eyes and we must become ourselves. As Emerson puts it:

There is a time in every man's education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself, for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till. The power which resides in him is new in nature, and none but he knows what that is which he can do, nor does he know until he has tried.

So, Emerson commands: do not outsource your share of life to the opinions of others, nor to fortune or luck. Take charge of your own existence, and live according to your own authority right now:

A political victory, a rise of rents, the recovery of your sick, or the return of your absent friend, or some other favorable event, raises your spirits, and you think good days are preparing for you. Do not believe it. Nothing can bring you peace but yourself. Nothing can bring you peace but the triumph of principles.

Explore Emerson’s philosophy of self-reliance further

W hat do you make of Emerson’s analysis? Do you value self-reliance over conformity? Do you agree that our intuition is often wiser than public opinion? Or is there an extent to which the ‘call’ of conscience we hear internally is actually the voice of society inside us?

If you’d like to explore Emerson’s view further, you can read his Self-Reliance essay in full in this free PDF (if you have a spare 30-40 minutes, I highly recommend doing so — it’s a fantastic read. Emerson offers powerful critiques of different aspects of society — including the objects of education, travel, and the accumulation of wealth — and treats us to some beautiful natural imagery in his illustration of how we might live happier, more authentic lives.)

You might also be interested in these related reads which discuss the importance of self-reliance for living well:

- The Porcupine’s Dilemma: Schopenhauer’s Wistful Parable on Human Connection

- Übermensch Explained: the Meaning of Nietzsche’s ‘Superman’

- Albert Camus on Coping with Life's Absurdity

- Kierkegaard On Finding the Meaning of Life

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Best 5 Books to Read

- Henry David Thoreau: The Best 5 Books to Read

Finally, if you enjoy reflecting on these kinds of themes, you might like my free Sunday email, in which I distill one philosophical idea per week, and invite you to share your view. If you’re interested, you can sign up for free below (no spam, unsubscribe any time):

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free):

About the author.

Jack Maden Founder Philosophy Break

Having received great value from studying philosophy for 15+ years (picking up a master’s degree along the way), I founded Philosophy Break in 2018 as an online social enterprise dedicated to making the subject’s wisdom accessible to all. Learn more about me and the project here.

If you enjoy learning about humanity’s greatest thinkers, you might like my free Sunday email. I break down one mind-opening idea from philosophy, and invite you to share your view.

Subscribe for free here , and join 11,500+ philosophers enjoying a nugget of profundity each week (free forever, no spam, unsubscribe any time).

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 11,500+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.

The Last Time Meditation: a Stoic Tool for Living in the Present

5 -MIN BREAK

Nietzsche On Why Suffering is Necessary for Greatness

3 -MIN BREAK

How to Live a Fulfilling Life, According to Philosophy Break Subscribers

15 -MIN BREAK

Enrich Your Personal Philosophy with these 6 Major Philosophies for Life

17 -MIN BREAK

View All Breaks

PHILOSOPHY 101

- What is Philosophy?

- Why is Philosophy Important?

- Philosophy’s Best Books

- About Philosophy Break

- Support the Project

- Instagram / Threads / Facebook

- TikTok / Twitter

Philosophy Break is an online social enterprise dedicated to making the wisdom of philosophy instantly accessible (and useful!) for people striving to live happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives. Learn more about us here . To offset a fraction of what it costs to maintain Philosophy Break, we participate in the Amazon Associates Program. This means if you purchase something on Amazon from a link on here, we may earn a small percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you. This helps support Philosophy Break, and is very much appreciated.

Access our generic Amazon Affiliate link here

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

© Philosophy Break Ltd, 2024

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Photo from Amos Bronson Alcott 1882.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

An American essayist, poet, and popular philosopher, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82) began his career as a Unitarian minister in Boston, but achieved worldwide fame as a lecturer and the author of such essays as “Self-Reliance,” “History,” “The Over-Soul,” and “Fate.” Drawing on English and German Romanticism, Neoplatonism, Kantianism, and Hinduism, Emerson developed a metaphysics of process, an epistemology of moods, and an “existentialist” ethics of self-improvement. He influenced generations of Americans, from his friend Henry David Thoreau to John Dewey, and in Europe, Friedrich Nietzsche, who takes up such Emersonian themes as power, fate, the uses of poetry and history, and the critique of Christianity.

1. Chronology of Emerson’s Life

2.1 education, 2.2 process, 2.3 morality, 2.4 christianity, 2.6 unity and moods, 3. emerson on slavery and race, 4.1 consistency, 4.2 early and late emerson, 4.3 sources and influence, works by emerson, selected writings on emerson, other internet resources, related entries, 2. major themes in emerson’s philosophy.

In “The American Scholar,” delivered as the Phi Beta Kappa Address in 1837, Emerson maintains that the scholar is educated by nature, books, and action. Nature is the first in time (since it is always there) and the first in importance of the three. Nature’s variety conceals underlying laws that are at the same time laws of the human mind: “the ancient precept, ‘Know thyself,’ and the modern precept, ‘Study nature,’ become at last one maxim” (CW1: 55). Books, the second component of the scholar’s education, offer us the influence of the past. Yet much of what passes for education is mere idolization of books — transferring the “sacredness which applies to the act of creation…to the record.” The proper relation to books is not that of the “bookworm” or “bibliomaniac,” but that of the “creative” reader (CW1: 58) who uses books as a stimulus to attain “his own sight of principles.” Used well, books “inspire…the active soul” (CW1: 56). Great books are mere records of such inspiration, and their value derives only, Emerson holds, from their role in inspiring or recording such states of the soul. The “end” Emerson finds in nature is not a vast collection of books, but, as he puts it in “The Poet,” “the production of new individuals,…or the passage of the soul into higher forms” (CW3:14).

The third component of the scholar’s education is action. Without it, thought “can never ripen into truth” (CW1: 59). Action is the process whereby what is not fully formed passes into expressive consciousness. Life is the scholar’s “dictionary” (CW1: 60), the source for what she has to say: “Only so much do I know as I have lived” (CW1:59). The true scholar speaks from experience, not in imitation of others; her words, as Emerson puts it, are “are loaded with life…” (CW1: 59). The scholar’s education in original experience and self-expression is appropriate, according to Emerson, not only for a small class of people, but for everyone. Its goal is the creation of a democratic nation. Only when we learn to “walk on our own feet” and to “speak our own minds,” he holds, will a nation “for the first time exist” (CW1: 70).

Emerson returned to the topic of education late in his career in “Education,” an address he gave in various versions at graduation exercises in the 1860s. Self-reliance appears in the essay in his discussion of respect. The “secret of Education,” he states, “lies in respecting the pupil.” It is not for the teacher to choose what the pupil will know and do, but for the pupil to discover “his own secret.” The teacher must therefore “wait and see the new product of Nature” (E: 143), guiding and disciplining when appropriate-not with the aim of encouraging repetition or imitation, but with that of finding the new power that is each child’s gift to the world. The aim of education is to “keep” the child’s “nature and arm it with knowledge in the very direction in which it points” (E: 144). This aim is sacrificed in mass education, Emerson warns. Instead of educating “masses,” we must educate “reverently, one by one,” with the attitude that “the whole world is needed for the tuition of each pupil” (E: 154).

Emerson is in many ways a process philosopher, for whom the universe is fundamentally in flux and “permanence is but a word of degrees” (CW 2: 179). Even as he talks of “Being,” Emerson represents it not as a stable “wall” but as a series of “interminable oceans” (CW3: 42). This metaphysical position has epistemological correlates: that there is no final explanation of any fact, and that each law will be incorporated in “some more general law presently to disclose itself” (CW2: 181). Process is the basis for the succession of moods Emerson describes in “Experience,” (CW3: 30), and for the emphasis on the present throughout his philosophy.

Some of Emerson’s most striking ideas about morality and truth follow from his process metaphysics: that no virtues are final or eternal, all being “initial,” (CW2: 187); that truth is a matter of glimpses, not steady views. We have a choice, Emerson writes in “Intellect,” “between truth and repose,” but we cannot have both (CW2: 202). Fresh truth, like the thoughts of genius, comes always as a surprise, as what Emerson calls “the newness” (CW3: 40). He therefore looks for a “certain brief experience, which surprise[s] me in the highway or in the market, in some place, at some time…” (CW1: 213). This is an experience that cannot be repeated by simply returning to a place or to an object such as a painting. A great disappointment of life, Emerson finds, is that one can only “see” certain pictures once, and that the stories and people who fill a day or an hour with pleasure and insight are not able to repeat the performance.

Emerson’s basic view of religion also coheres with his emphasis on process, for he holds that one finds God only in the present: “God is, not was” (CW1:89). In contrast, what Emerson calls “historical Christianity” (CW1: 82) proceeds “as if God were dead” (CW1: 84). Even history, which seems obviously about the past, has its true use, Emerson holds, as the servant of the present: “The student is to read history actively and not passively; to esteem his own life the text, and books the commentary” (CW2: 5).

Emerson’s views about morality are intertwined with his metaphysics of process, and with his perfectionism, his idea that life has the goal of passing into “higher forms” (CW3:14). The goal remains, but the forms of human life, including the virtues, are all “initial” (CW2: 187). The word “initial” suggests the verb “initiate,” and one interpretation of Emerson’s claim that “all virtues are initial” is that virtues initiate historically developing forms of life, such as those of the Roman nobility or the Confucian junxi . Emerson does have a sense of morality as developing historically, but in the context in “Circles” where his statement appears he presses a more radical and skeptical position: that our virtues often must be abandoned rather than developed. “The terror of reform,” he writes, “is the discovery that we must cast away our virtues, or what we have always esteemed such, into the same pit that has consumed our grosser vices” (CW2: 187). The qualifying phrase “or what we have always esteemed such” means that Emerson does not embrace an easy relativism, according to which what is taken to be a virtue at any time must actually be a virtue. Yet he does cast a pall of suspicion over all established modes of thinking and acting. The proper standpoint from which to survey the virtues is the ‘new moment‘ — what he elsewhere calls truth rather than repose (CW2:202) — in which what once seemed important may appear “trivial” or “vain” (CW2:189). From this perspective (or more properly the developing set of such perspectives) the virtues do not disappear, but they may be fundamentally altered and rearranged.

Although Emerson is thus in no position to set forth a system of morality, he nevertheless delineates throughout his work a set of virtues and heroes, and a corresponding set of vices and villains. In “Circles” the vices are “forms of old age,” and the hero the “receptive, aspiring” youth (CW2:189). In the “Divinity School Address,” the villain is the “spectral” preacher whose sermons offer no hint that he has ever lived. “Self Reliance” condemns virtues that are really “penances” (CW2: 31), and the philanthropy of abolitionists who display an idealized “love” for those far away, but are full of hatred for those close by (CW2: 30).

Conformity is the chief Emersonian vice, the opposite or “aversion” of the virtue of “self-reliance.” We conform when we pay unearned respect to clothing and other symbols of status, when we show “the foolish face of praise” or the “forced smile which we put on in company where we do not feel at ease in answer to conversation which does not interest us” (CW2: 32). Emerson criticizes our conformity even to our own past actions-when they no longer fit the needs or aspirations of the present. This is the context in which he states that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen, philosophers and divines” (CW2: 33). There is wise and there is foolish consistency, and it is foolish to be consistent if that interferes with the “main enterprise of the world for splendor, for extent,…the upbuilding of a man” (CW1: 65).

If Emerson criticizes much of human life, he nevertheless devotes most of his attention to the virtues. Chief among these is what he calls “self-reliance.” The phrase connotes originality and spontaneity, and is memorably represented in the image of a group of nonchalant boys, “sure of a dinner…who would disdain as much as a lord to do or say aught to conciliate one…” The boys sit in judgment on the world and the people in it, offering a free, “irresponsible” condemnation of those they see as “silly” or “troublesome,” and praise for those they find “interesting” or “eloquent.” (CW2: 29). The figure of the boys illustrates Emerson’s characteristic combination of the romantic (in the glorification of children) and the classical (in the idea of a hierarchy in which the boys occupy the place of lords or nobles).

Although he develops a series of analyses and images of self-reliance, Emerson nevertheless destabilizes his own use of the concept. “To talk of reliance,” he writes, “is a poor external way of speaking. Speak rather of that which relies, because it works and is” (CW 2:40). ‘Self-reliance’ can be taken to mean that there is a self already formed on which we may rely. The “self” on which we are to “rely” is, in contrast, the original self that we are in the process of creating. Such a self, to use a phrase from Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo, “becomes what it is.”

For Emerson, the best human relationships require the confident and independent nature of the self-reliant. Emerson’s ideal society is a confrontation of powerful, independent “gods, talking from peak to peak all round Olympus.” There will be a proper distance between these gods, who, Emerson advises, “should meet each morning, as from foreign countries, and spending the day together should depart, as into foreign countries” (CW 3:81). Even “lovers,” he advises, “should guard their strangeness” (CW3: 82). Emerson portrays himself as preserving such distance in the cool confession with which he closes “Nominalist and Realist,” the last of the Essays, Second Series :

I talked yesterday with a pair of philosophers: I endeavored to show my good men that I liked everything by turns and nothing long…. Could they but once understand, that I loved to know that they existed, and heartily wished them Godspeed, yet, out of my poverty of life and thought, had no word or welcome for them when they came to see me, and could well consent to their living in Oregon, for any claim I felt on them, it would be a great satisfaction (CW 3:145).

The self-reliant person will “publish” her results, but she must first learn to detect that spark of originality or genius that is her particular gift to the world. It is not a gift that is available on demand, however, and a major task of life is to meld genius with its expression. “The man,” Emerson states “is only half himself, the other half is his expression” (CW 3:4). There are young people of genius, Emerson laments in “Experience,” who promise “a new world” but never deliver: they fail to find the focus for their genius “within the actual horizon of human life” (CW 3:31). Although Emerson emphasizes our independence and even distance from one another, then, the payoff for self-reliance is public and social. The scholar finds that the most private and secret of his thoughts turn out to be “the most acceptable, most public, and universally true” (CW1: 63). And the great “representative men” Emerson identifies are marked by their influence on the world. Their names-Plato, Moses, Jesus, Luther, Copernicus, even Napoleon-are “ploughed into the history of this world” (CW1: 80).

Although self-reliance is central, it is not the only Emersonian virtue. Emerson also praises a kind of trust, and the practice of a “wise skepticism.” There are times, he holds, when we must let go and trust to the nature of the universe: “As the traveler who has lost his way, throws his reins on his horse’s neck, and trusts to the instinct of the animal to find his road, so must we do with the divine animal who carries us through this world” (CW3:16). But the world of flux and conflicting evidence also requires a kind of epistemological and practical flexibility that Emerson calls “wise skepticism” (CW4: 89). His representative skeptic of this sort is Michel de Montaigne, who as portrayed in Representative Men is no unbeliever, but a man with a strong sense of self, rooted in the earth and common life, whose quest is for knowledge. He wants “a near view of the best game and the chief players; what is best in the planet; art and nature, places and events; but mainly men” (CW4: 91). Yet he knows that life is perilous and uncertain, “a storm of many elements,” the navigation through which requires a flexible ship, “fit to the form of man.” (CW4: 91).

The son of a Unitarian minister, Emerson attended Harvard Divinity School and was employed as a minister for almost three years. Yet he offers a deeply felt and deeply reaching critique of Christianity in the “Divinity School Address,” flowing from a line of argument he establishes in “The American Scholar.” If the one thing in the world of value is the active soul, then religious institutions, no less than educational institutions, must be judged by that standard. Emerson finds that contemporary Christianity deadens rather than activates the spirit. It is an “Eastern monarchy of a Christianity” in which Jesus, originally the “friend of man,” is made the enemy and oppressor of man. A Christianity true to the life and teachings of Jesus should inspire “the religious sentiment” — a joyous seeing that is more likely to be found in “the pastures,” or “a boat in the pond” than in a church. Although Emerson thinks it is a calamity for a nation to suffer the “loss of worship” (CW1: 89) he finds it strange that, given the “famine of our churches” (CW1: 85) anyone should attend them. He therefore calls on the Divinity School graduates to breathe new life into the old forms of their religion, to be friends and exemplars to their parishioners, and to remember “that all men have sublime thoughts; that all men value the few real hours of life; they love to be heard; they love to be caught up into the vision of principles” (CW1: 90).

Power is a theme in Emerson’s early writing, but it becomes especially prominent in such middle- and late-career essays as “Experience,” “Montaigne, or the Skeptic” “Napoleon,” and “Power.” Power is related to action in “The American Scholar,” where Emerson holds that a “true scholar grudges every opportunity of action past by, as a loss of power” (CW1: 59). It is also a subject of “Self-Reliance,” where Emerson writes of each person that “the power which resides in him is new in nature” (CW2: 28). In “Experience” Emerson speaks of a life which “is not intellectual or critical, but sturdy” (CW3: 294); and in “Power” he celebrates the “bruisers” (CW6: 34) of the world who express themselves rudely and get their way. The power in which Emerson is interested, however, is more artistic and intellectual than political or military. In a characteristic passage from “Power,” he states:

In history the great moment, is, when the savage is just ceasing to be a savage, with all his hairy Pelasgic strength directed on his opening sense of beauty:-and you have Pericles and Phidias,-not yet passed over into the Corinthian civility. Everything good in nature and the world is in that moment of transition, when the swarthy juices still flow plentifully from nature, but their astringency or acridity is got out by ethics and humanity. (CW6: 37–8)

Power is all around us, but it cannot always be controlled. It is like “a bird which alights nowhere,” hopping “perpetually from bough to bough” (CW3: 34). Moreover, we often cannot tell at the time when we exercise our power that we are doing so: happily we sometimes find that much is accomplished in “times when we thought ourselves indolent” (CW3: 28).

At some point in many of his essays and addresses, Emerson enunciates, or at least refers to, a great vision of unity. He speaks in “The American Scholar” of an “original unit” or “fountain of power” (CW1: 53), of which each of us is a part. He writes in “The Divinity School Address” that each of us is “an inlet into the deeps of Reason.” And in “Self-Reliance,” the essay that more than any other celebrates individuality, he writes of “the resolution of all into the ever-blessed ONE” (CW2: 40). “The Oversoul” is Emerson’s most sustained discussion of “the ONE,” but he does not, even there, shy away from the seeming conflict between the reality of process and the reality of an ultimate metaphysical unity. How can the vision of succession and the vision of unity be reconciled?

Emerson never comes to a clear or final answer. One solution he both suggests and rejects is an unambiguous idealism, according to which a nontemporal “One” or “Oversoul” is the only reality, and all else is illusion. He suggests this, for example, in the many places where he speaks of waking up out of our dreams or nightmares. But he then portrays that to which we awake not simply as an unchanging “ONE,” but as a process or succession: a “growth” or “movement of the soul” (CW2: 189); or a “new yet unapproachable America” (CW3: 259).

Emerson undercuts his visions of unity (as of everything else) through what Stanley Cavell calls his “epistemology of moods.” According to this epistemology, most fully developed in “Experience” but present in all of Emerson’s writing, we never apprehend anything “straight” or in-itself, but only under an aspect or mood. Emerson writes that life is “a train of moods like a string of beads,” through which we see only what lies in each bead’s focus (CW3: 30). The beads include our temperaments, our changing moods, and the “Lords of Life” which govern all human experience. The Lords include “Succession,” “Surface,” “Dream,” “Reality,” and “Surprise.” Are the great visions of unity, then, simply aspects under which we view the world?

Emerson’s most direct attempt to reconcile succession and unity, or the one and the many, occurs in the last essay in the Essays, Second Series , entitled “Nominalist and Realist.” There he speaks of the universe as an “old Two-face…of which any proposition may be affirmed or denied” (CW3: 144). As in “Experience,” Emerson leaves us with the whirling succession of moods. “I am always insincere,” he skeptically concludes, “as always knowing there are other moods” (CW3: 145). But Emerson enacts as well as describes the succession of moods, and he ends “Nominalist and Realist” with the “feeling that all is yet unsaid,” and with at least the idea of some universal truth (CW3: 363).

Massachusetts ended slavery in 1783, when Chief Justice William Cushing instructed the jury in the case of Quock Walker, a former slave, that “the idea of slavery” was “inconsistent” with the Massachusetts Constitution’ guarantee that “all men are born free and equal” (Gougeon, 71). Emerson first encountered slavery when he went south for his health in the winter of 1827, when he was 23. He recorded the following scene in his journal from his time in Tallahasse, Florida:

A fortnight since I attended a meeting of the Bible Society. The Treasurer of this institution is Marshal of the district & by a somewhat unfortunate arrangement had appointed a special meeting of the Society & a Slave Auction at the same time & place, one being in the Government house & the other in the adjoining yard. One ear therefore heard the glad tidings of great joy whilst the other was regaled with “Going gentlemen, Going!” And almost without changing our position we might aid in sending the scriptures into Africa or bid for “four children without the mother who had been kidnapped therefrom” (JMN3: 117).

Emerson never questioned the iniquity of slavery, though it was not a main item on his intellectual agenda until the eighteen forties. He refers to abolition in the “Prospects” chapter of Nature when he speaks of the “gleams of a better light” in the darkness of history and gives as examples “the abolition of the Slave-trade,” “the history of Jesus Christ,” and “the wisdom of children” (CW1:43). He condemns slavery in some of his greatest essays, “Self-Reliance” (1841), so that even if we didn’t have the anti-slavery addresses of the 1840s and 1850s, we would still have evidence both of the existence of slavery and of Emerson’s opposition to it. He praises “the bountiful cause of Abolition,” although he laments that the cause had been taken over by “angry bigots.” Later in the essay he treats abolition as one of the great causes and movements of world history, along with Christianity, the Reformation, and Methodism. In a well-known statement he writes that an “institution is the shadow of one man,” giving as examples “the Reformation, of Luther; Quakerism, of Fox; Methodism, of Wesley; Abolition of Clarkson” (CW2: 35). The unfamiliar name in this list is that of Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846), a Cambridge-educated clergyman who helped found the British Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Clarkson travelled on horseback throughout Britain, interviewing sailors who worked on slaving ships, and exhibiting such tools as manacles, thumbscews, branding irons, and other tools of the trade. His History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade by the British Parliament (1808) would be a major source for Emerson’s anti-slavery addresses.

Slavery also appears in “Politics,” from the Essays, Second Series of 1844, when Emerson surveys the two main American parties. One, standing for free trade, wide suffrage, and the access of the young and poor to wealth and power, has the “best cause” but the least attractive leaders; while the other has the most cultivated and able leaders, but is “merely defensive of property.” This conservative party, moreover, “vindicates no right, it aspires to no real good, it brands no crime, it proposes no generous policy, it does not build nor write, nor cherish the arts, nor foster religion, nor establish schools, nor encourage science, nor emancipate the slave, nor befriend the poor, or the Indian, or the immigrant” (CW3: 124). Emerson stands here for emancipation, not simply for the ending of the slave trade.

1844 was also the year of Emerson’s breakout anti-slavery address, which he gave at the annual celebration of the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies. In the background was the American war with Mexico, the annexation of Texas, and the likelihood that it would be entering the Union as a slave state. Although Concord was a hotbed of abolitionism compared to Boston, there were many conservatives in the town. No church allowed Emerson to speak on the subject, and when the courthouse was secured for the talk, the sexton refused to ring the church bell to announce it, a task the young Henry David Thoreau took upon himself to perform (Gougeon, 75). In his address, Emerson develops a critique of the language we use to speak about, or to avoid speaking about, black slavery:

Language must be raked, the secrets of slaughter-houses and infamous holes that cannot front the day, must be ransacked, to tell what negro-slavery has been. These men, our benefactors, as they are producers of corn and wine, of coffee, of tobacco, of cotton, of sugar, of rum, and brandy, gentle and joyous themselves, and producers of comfort and luxury for the civilized world.… I am heart-sick when I read how they came there, and how they are kept there. Their case was left out of the mind and out of the heart of their brothers ( Emerson’s Antislavery Writings , 9).

Emerson’s long address is both clear-eyed about the evils of slavery and hopeful about the possibilities of the Africans. Speaking with the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass beside him on the dais, Emerson states: “The black man carries in his bosom an indispensable element of a new and coming civilization.” He praises “such men as” Toussaint [L]Ouverture, leader of the Haitian slave rebellion, and announces: “here is the anti-slave: here is man; and if you have man, black or white is an insignificance.” (Wirzrbicki, 95; Emerson’s Antislavery Writings, 31).

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 effectively nationalized slavery, requiring officials and citizens of the free states to assist in returning escaped slaves to their owners. Emerson’s 1851 “Address to the Citizens of Concord” calls both for the abrogation of the law and for disobeying it while it is still current. In 1854, the escaped slave Anthony Burns was shipped back to Virginia by order of the Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, an order carried out by U. S. Marines, in accordance with the new law. This example of “Slavery in Massachusetts” (as Henry Thoreau put it in a well-known address) is in the background of Emerson’s 1855 “Lecture on Slavery,” where he calls the recognition of slavery by the original 1787 Constitution a “crime.” Emerson gave these and other antislavery addresses multiple times in various places from the late 1840s till the beginning of the Civil War. On the eve of the war Emerson supported John Brown, the violent abolitionist who was executed in 1859 by the U. S. government after he attacked the U. S. armory in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. In the middle of the War, Emerson raised funds for black regiments of Union soldiers (Wirzbicki, 251–2) and read his “Boston Hymn” to an audience of 3000 celebrating President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. “Pay ransom to the owner,” Emerson wrote, “and fill the bag to the brim. Who is the owner? The slave is owner. And ever was. Pay him” (CW9: 383).

Emerson’s magisterial essay “Fate,” published in The Conduct of Life (1860) is distinguished not only by its attempt to reconcile freedom and necessity, but by disturbing pronouncements about fate and race, for example:

The population of the world is a conditional population, not the best, but the best that could live now; and the scale of tribes, and the steadiness with which victory adheres to one tribe, and defeat to another, is as uniform as the superposition of strata. We know in history what weight belongs to race. We see the English, French, and Germans planting themselves on every shore and market of America and Australia, and monopolizing the commerce of these countries. We like the nervous and victorious habit of our own branch of the family. We follow the step of the Jew, of the Indian, of the Negro. We see how much will has been expended to extinguish the Jew, in vain.… The German and Irish millions, like the Negro, have a great deal of guano in their destiny. They are ferried over the Atlantic, and carted over America, to ditch and to drudge, to make corn cheap, and then to lie down prematurely to make a spot of green grass on the prairie (CW6: 8–9).

The references to race here show the influence of a new “scientific” interest in both England and America in the role that race—often conflated with culture or nation—plays in human evolution. In America, this interest was entangled with the institution of slavery, the encounters with Native American tribes, and with the notion of “Anglo-Saxon liberties” that came to prominence during the American Revolution, and developed into the idea that there was an Anglo-Saxon race (see Horsman).

Emerson would not be Emerson, however, if he did not conduct a critique of his terms, and “race” is a case in point. He takes it up in a non-American context, however: in the essay “Race” from English Traits (1856). Emerson’s critique of his title begins in the essay’s first paragraph when he writes that “each variety shades down imperceptibly into the next, and you cannot draw the line where a race begins or ends.” Civilization “eats away the old traits,” he continues, and religions construct new forms of character that cut against old racial divisions. More deeply still, he identifies considerations that “threaten to undermine” the concept of race. The “fixity … of races as we see them,” he writes, “is a weak argument for the eternity of these frail boundaries, since all our historical period is a point” in the long duration of nature (CW 5:24). The patterns we see today aren’t pure anyway:

though we flatter the self-love of men and nations by the legend of pure races, all our experience is of the gradation and resolution of races, and strange resemblances meet us every where, It need not puzzle us that Malay and Papuan, Celt and Roman, Saxon and Tartar should mix, when we see the rudiments of tiger and baboon in our human form, and know that the barriers of races are not so firm, but that some spray sprinkles us from the antidiluvian seas.

As in Nature and his great early works, Emerson asserts our intimate relations with the natural world, from the oceans to the animals. Why, one might think, should one of the higher but still initial forms be singled out for separation, abasement, and slavery? Emerson works out his views in “Race” without referring to American slavery, however, in a book about England where he sees a healthy mixture, not a pure race. England’s history, he writes, is not so much “one of certain tribes of Saxons, Jutes, or Frisians, coming from one place, and genetically identical, as it is an anthology of temperaments out of them all.… The English derive their pedigree from such a range of nationalities.… The Scandinavians in her race still hear in every age the murmurs of their mother, the ocean; the Briton in the blood hugs the homestead still” (CW5: 28). Still, it is striking that Emerson never mentions slavery in either “Fate” or “Race,” both of which were written during his intense period of public opposition to American slavery.

4. Some Questions about Emerson

Emerson routinely invites charges of inconsistency. He says the world is fundamentally a process and fundamentally a unity; that it resists the imposition of our will and that it flows with the power of our imagination; that travel is good for us, since it adds to our experience, and that it does us no good, since we wake up in the new place only to find the same “ sad self” we thought we had left behind (CW2: 46).

Emerson’s “epistemology of moods” is an attempt to construct a framework for encompassing what might otherwise seem contradictory outlooks, viewpoints, or doctrines. Emerson really means to “accept,” as he puts it, “the clangor and jangle of contrary tendencies” (CW3: 36). He means to be irresponsible to all that holds him back from his self-development. That is why, at the end of “Circles,” he writes that he is “only an experimenter…with no Past at my back” (CW2: 188). In the world of flux that he depicts in that essay, there is nothing stable to be responsible to: “every moment is new; the past is always swallowed and forgotten, the coming only is sacred” (CW2: 189).

Despite this claim, there is considerable consistency in Emerson’s essays and among his ideas. To take just one example, the idea of the “active soul” – mentioned as the “one thing in the world, of value” in ‘The American Scholar’ – is a presupposition of Emerson’s attack on “the famine of the churches” (for not feeding or activating the souls of those who attend them); it is an element in his understanding of a poem as “a thought so passionate and alive, that, like the spirit of a plant or an animal, it has an architecture of its own …” (CW3: 6); and, of course, it is at the center of Emerson’s idea of self-reliance. There are in fact multiple paths of coherence through Emerson’s philosophy, guided by ideas discussed previously: process, education, self-reliance, and the present.

It is hard for an attentive reader not to feel that there are important differences between early and late Emerson: for example, between the buoyant Nature (1836) and the weary ending of “Experience” (1844); between the expansive author of “Self-Reliance” (1841) and the burdened writer of “Fate” (1860). Emerson himself seems to advert to such differences when he writes in “Fate”: “Once we thought, positive power was all. Now we learn that negative power, or circumstance, is half” (CW6: 8). Is “Fate” the record of a lesson Emerson had not absorbed in his early writing, concerning the multiple ways in which circumstances over which we have no control — plagues, hurricanes, temperament, sexuality, old age — constrain self-reliance or self-development?

“Experience” is a key transitional essay. “Where do we find ourselves?” is the question with which it begins. The answer is not a happy one, for Emerson finds that we occupy a place of dislocation and obscurity, where “sleep lingers all our lifetime about our eyes, as night hovers all day in the boughs of the fir-tree” (CW3: 27). An event hovering over the essay, but not disclosed until its third paragraph, is the death of his five-year old son Waldo. Emerson finds in this episode and his reaction to it an example of an “unhandsome” general character of existence-it is forever slipping away from us, like his little boy.

“Experience” presents many moods. It has its moments of illumination, and its considered judgment that there is an “Ideal journeying always with us, the heaven without rent or seam” (CW3: 41). It offers wise counsel about “skating over the surfaces of life” and confining our existence to the “mid-world.” But even its upbeat ending takes place in a setting of substantial “defeat.” “Up again, old heart!” a somewhat battered voice states in the last sentence of the essay. Yet the essay ends with an assertion that in its great hope and underlying confidence chimes with some of the more expansive passages in Emerson’s writing. The “true romance which the world exists to realize,” he states, “will be the transformation of genius into practical power” (CW3: 49).

Despite important differences in tone and emphasis, Emerson’s assessment of our condition remains much the same throughout his writing. There are no more dire indictments of ordinary human life than in the early work, “The American Scholar,” where Emerson states that “Men in history, men in the world of to-day, are bugs, are spawn, and are called ‘the mass’ and ‘the herd.’ In a century, in a millennium, one or two men; that is to say, one or two approximations to the right state of every man” (CW1: 65). Conversely, there is no more idealistic statement in his early work than the statement in “Fate” that “[t]hought dissolves the material universe, by carrying the mind up into a sphere where all is plastic” (CW6: 15). All in all, the earlier work expresses a sunnier hope for human possibilities, the sense that Emerson and his contemporaries were poised for a great step forward and upward; and the later work, still hopeful and assured, operates under a weight or burden, a stronger sense of the dumb resistance of the world.

Emerson read widely, and gave credit in his essays to the scores of writers from whom he learned. He kept lists of literary, philosophical, and religious thinkers in his journals and worked at categorizing them.

Among the most important writers for the shape of Emerson’s philosophy are Plato and the Neoplatonist line extending through Plotinus, Proclus, Iamblichus, and the Cambridge Platonists. Equally important are writers in the Kantian and Romantic traditions (which Emerson probably learned most about from Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria ). Emerson read avidly in Indian, especially Hindu, philosophy, and in Confucianism. There are also multiple empiricist, or experience-based influences, flowing from Berkeley, Wordsworth and other English Romantics, Newton’s physics, and the new sciences of geology and comparative anatomy. Other writers whom Emerson often mentions are Anaxagoras, St. Augustine, Francis Bacon, Jacob Behmen, Cicero, Goethe, Heraclitus, Lucretius, Mencius, Pythagoras, Schiller, Thoreau, August and Friedrich Schlegel, Shakespeare, Socrates, Madame de Staël and Emanuel Swedenborg.

Emerson’s works were well known throughout the United States and Europe in his day. Nietzsche read German translations of Emerson’s essays, copied passages from “History” and “Self-Reliance” in his journals, and wrote of the Essays : that he had never “felt so much at home in a book.” Emerson’s ideas about “strong, overflowing” heroes, friendship as a battle, education, and relinquishing control in order to gain it, can be traced in Nietzsche’s writings. Other Emersonian ideas-about transition, the ideal in the commonplace, and the power of human will permeate the writings of such classical American pragmatists as William James and John Dewey.

Stanley Cavell’s engagement with Emerson is the most original and prolonged by any philosopher, and Emerson is a primary source for his writing on “moral perfectionism.” In his earliest essays on Emerson, such as “Thinking of Emerson” and “Emerson, Coleridge, Kant,” Cavell considers Emerson’s place in the Kantian tradition, and he explores the affinity between Emerson’s call in “The American Scholar” for a return to “the common and the low” and Wittgenstein’s quest for a return to ordinary language. In “Being Odd, Getting Even” and “Aversive Thinking,” Cavell considers Emerson’s anticipations of existentialism, and in these and other works he explores Emerson’s affinities with Nietzsche and Heidegger.

In Conditions Handsome and Unhandsome and Cities of Words , Cavell develops what he calls “Emersonian moral perfectionism,” of which he finds an exemplary expression in Emerson’s “History”: “So all that is said of the wise man by Stoic, or oriental or modern essayist, describes to each reader his own idea, describes his unattained but attainable self.” Emersonian perfectionism is oriented towards a wiser or better self that is never final, always initial, always on the way.

Cavell does not have a neat and tidy definition of perfectionism, and his list of perfectionist works ranges from Plato’s Republic to Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations , but he identifies “two dominating themes of perfectionism” in Emerson’s writing: (1) “that the human self … is always becoming, as on a journey, always partially in a further state. This journey is described as education or cultivation”; (2) “that the other to whom I can use the words I discover in which to express myself is the Friend—a figure that may occur as the goal of the journey but also as its instigation and accompaniment” ( Cities of Words , 26–7). The friend can be a person but it may also be a text. In the sentence from “History” cited above, the writing of the “Stoic, or oriental or modern essayist” about “the wise man” functions as a friend and guide, describing to each reader not just any idea, but “his own idea.” This is the text as instigator and companion.

Cavell’s engagement with perfectionism springs from a response to his colleague John Rawls, who in A Theory of Justice condemns Nietzsche (and implicitly Emerson) for his statement that “mankind must work continually to produce individual great human beings.” “Perfectionism,” Rawls states, “is denied as a political principle.” Cavell replies that Emerson’s (and Nietzsche’s) focus on the great man has nothing to do with a transfer of economic resources or political power, or with the idea that “there is a separate class of great men …for whose good, and conception of good, the rest of society is to live” (CHU, 49). The great man or woman, Cavell holds, is required for rather than opposed to democracy: “essential to the criticism of democracy from within” (CHU, 3).

- [ CW ] The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson , ed. Robert Spiller et al, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971–

- [ E ] “Education,” in Lectures and Biographical Sketches , in The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson , ed. Edward Waldo Emerson, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1883, pp. 125–59

- The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson , ed. Edward Waldo Emerson, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 12 volumes, 1903–4

- The Annotated Emerson , ed. David Mikics, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- The Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson , ed. Edward Waldo Emerson and Waldo Emerson Forbes. 10 vols., Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1910–14.

- The Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks of Ralph Waldo Emerson , ed. William Gillman, et al., Cambridge: Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1960–

- The Early Lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson , 3 vols, Stephen E. Whicher, Robert E. Spiller, and Wallace E. Williams, eds., Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961–72.

- The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson , ed. Ralph L. Rusk and Eleanor M. Tilton. 10 vols. New York: Columbia University Press, 1964–95.

- (with Thomas Carlyle), The Correspondence of Emerson and Carlyle , ed. Joseph Slater, New York: Columbia University Press, 1964.

- Emerson’s Antislavery Writings , eds. Len Gougeon and Joel Myerson, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995.

- The Later Lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson , eds. Ronald Bosco and Joel Myerson, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2003.

- Emerson: Political Writings (Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought) , ed. Kenneth Sacks, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- (See Chronology for original dates of publication.)

- Alcott, Amos Bronson, 1882, Ralph Waldo Emerson: An Estimate of His Character and Genius: In Prose and in Verse , Boston: A. Williams and Co., 1882)

- Allen, Gay Wilson, 1981, Waldo Emerson , New York: Viking Press.

- Arsić, Branka, 2010. On Leaving: A Reading in Emerson , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Arsić, Branka, and Carey Wolfe (eds.), 2010. The Other Emerson , Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bishop, Jonathan, 1964, Emerson on the Soul , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Buell, Lawrence, 2003, Emerson , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cameron, Sharon, 2007, Impersonality , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Carpenter, Frederick Ives, 1930, Emerson and Asia , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cavell, Stanley, 1981, “Thinking of Emerson” and “An Emerson Mood,” in The Senses of Walden, An Expanded Edition , San Francisco: North Point Press.

- –––, 1988, In Quest of the Ordinary: Lines of Skepticism and Romanticism , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- –––, 1990, Conditions Handsome and Unhandsome: The Constitution of Emersonian Perfectionism , Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Abbreviated CHU in the text.).

- –––, 2004, Emerson’s Transcendental Etudes , Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- –––, 2004, Cities of Words: Pedagogical Letters on a Register of the Moral Life , Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Conant, James, 1997, “Emerson as Educator,” ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance , 43: 181–206.

- –––, 2001, “Nietzsche as Educator,” Nietzsche’s Post-Moralism: Essays on Nietzsche’s Prelude to Philosophy’s Future , Richard Schacht (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 181–257.

- Constantinesco, Thomas, 2012, Ralph Waldo Emerson: L’Amérique à l’essai , Paris: Editions Rue d’Ulm.

- Ellison, Julie, 1984, Emerson’s Romantic Style , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Firkins, Oscar W., 1915, Ralph Waldo Emerson , Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Follett, Danielle, 2015, “The Tension Between Immanence and Dualism in Coleridge and Emerson,” in Romanticism and Philosophy: Thinking with Literature , Sophie Laniel-Musitelli and Thomas Constantinesco (eds.), London: Routledge, 209–221.

- Friedl, Herwig, 2018, Thinking in Search of a Language: Essays on American Intellect and Intuition , New York and London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Goodman, Russell B., 1990a, American Philosophy and the Romantic Tradition , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Chapter 2.

- –––, 1990b, “East-West Philosophy in Nineteenth Century America: Emerson and Hinduism,” Journal of the History of Ideas , 51(4): 625–45.

- –––, 1997, “Moral Perfectionism and Democracy in Emerson and Nietzsche,” ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance , 43: 159–80.

- –––, 2004, “The Colors of the Spirit: Emerson and Thoreau on Nature and the Self,” Nature in American Philosophy , Jean De Groot (ed.), Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1–18.

- –––, 2008, “Emerson, Romanticism, and Classical American Pragmatism,” The Oxford Handbook of American Philosophy , Cheryl Misak (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 19–37.

- –––, 2015, American Philosophy Before Pragmatism , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 147–99, 234–54.

- –––, 2021, “Transcendentalist Legacies in American Philosophy,” Handbook of American Romanticism, Philipp Löffler, Clemens Spahr, Jan Stievermann (ed.), Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 517–536.

- Holmes, Oliver Wendell, 1885, Ralph Waldo Emerson , Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Horsman, Reginald, 1981, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism, Cambridge, and London: Harvard University Press.

- Lysaker, John, 2008, Emerson and Self-Culture , Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Matthiessen, F. O., 1941, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Packer, B. L., 1982, Emerson’s Fall , New York: Continuum.

- –––, 2007, The Transcendentalists , Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Poirier, Richard, 1987, The Renewal of Literature: Emersonian Reflections , New York: Random House.

- –––, 1992, Poetry and Pragmatism , Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

- Porte, Joel, and Morris, Saundra (eds.), 1999, The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Richardson, Robert D. Jr., 1995, Emerson: The Mind on Fire , Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Sacks, Kenneth, 2003, Understanding Emerson: “The American Scholar” and His Struggle for Self-Reliance , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Urbas, Joseph, 2016, Emerson’s Metaphysics: A Song of Laws and Causes , Lanham, MD and London: Lexington Books.

- –––, 2021, The Philosophy of Ralph Waldo Emerson , New York and London: Routledge.

- Versluis, Arthur, 1993, American Transcendentalism and Asian Religions , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Whicher, Stephen, 1953, Freedom and Fate: An Inner Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson , Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Wirzbicki, Peter, 2021, Fighting for the Higher Law: Black and White Transcendentalists Against Slavery , Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Zavatta, Benedetta, 2019, Individuality and Beyond: Nietzsche Reads Emerson, trans. Alexander Reynolds , New York: Oxford University Press.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up topics and thinkers related to this entry at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

- Emerson Texts .

Anaxagoras | Augustine of Hippo | Bacon, Francis | Cambridge Platonists | Cicero | Dewey, John | Heraclitus | Iamblichus | James, William | Lucretius | Mencius | Nietzsche, Friedrich | Plotinus | Pythagoras | Schiller, Friedrich | Schlegel, Friedrich | Socrates | transcendentalism

Copyright © 2022 by Russell Goodman < rgoodman @ unm . edu >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Self-Reliance

Ralph waldo emerson, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Self-reliance : the original 1841 essay Ralph Waldo Emerson

Available online, at the library.

SAL3 (off-campus storage)

More options.

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary.

- The Waldo Emerson Essay 1. The Value of Barriers to Self-Reliance 2. Self-Reliance and the Individual 3. Self-Reliance and Society

- Twelve essays by Jessica Helfand On Learning On Gravity On Closure On Loneliness On Character On Uncertainty On Magnanimity On Love On Alchemy On Chance On Authenticity On Individualism On Narrative.

- (source: Nielsen Book Data)

Bibliographic information

Browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- The Columbian Exchange

- De Las Casas and the Conquistadors

- Early Visual Representations of the New World

- Failed European Colonies in the New World

- Successful European Colonies in the New World

- A Model of Christian Charity

- Benjamin Franklin’s Satire of Witch Hunting

- The American Revolution as Civil War

- Patrick Henry and “Give Me Liberty!”

- Lexington & Concord: Tipping Point of the Revolution

- Abigail Adams and “Remember the Ladies”

- Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” 1776

- Citizen Leadership in the Young Republic

- After Shays’ Rebellion

- James Madison Debates a Bill of Rights

- America, the Creeks, and Other Southeastern Tribes

- America and the Six Nations: Native Americans After the Revolution

- The Revolution of 1800

- Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase

- The Expansion of Democracy During the Jacksonian Era

- The Religious Roots of Abolition

Individualism in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”

- Aylmer’s Motivation in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark”

- Thoreau’s Critique of Democracy in “Civil Disobedience”

- Hester’s A: The Red Badge of Wisdom

- “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”

- The Cult of Domesticity

- The Family Life of the Enslaved

- A Pro-Slavery Argument, 1857

- The Underground Railroad

- The Enslaved and the Civil War

- Women, Temperance, and Domesticity

- “The Chinese Question from a Chinese Standpoint,” 1873

- “To Build a Fire”: An Environmentalist Interpretation

- Progressivism in the Factory