Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Graduate School Applications: Writing a Research Statement

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is a Research Statement?

A research statement is a short document that provides a brief history of your past research experience, the current state of your research, and the future work you intend to complete.

The research statement is a common component of a potential candidate’s application for post-undergraduate study. This may include applications for graduate programs, post-doctoral fellowships, or faculty positions. The research statement is often the primary way that a committee determines if a candidate’s interests and past experience make them a good fit for their program/institution.

What Should It Look Like?

Research statements are generally one to two single-spaced pages. You should be sure to thoroughly read and follow the length and content requirements for each individual application.

Your research statement should situate your work within the larger context of your field and show how your works contributes to, complicates, or counters other work being done. It should be written for an audience of other professionals in your field.

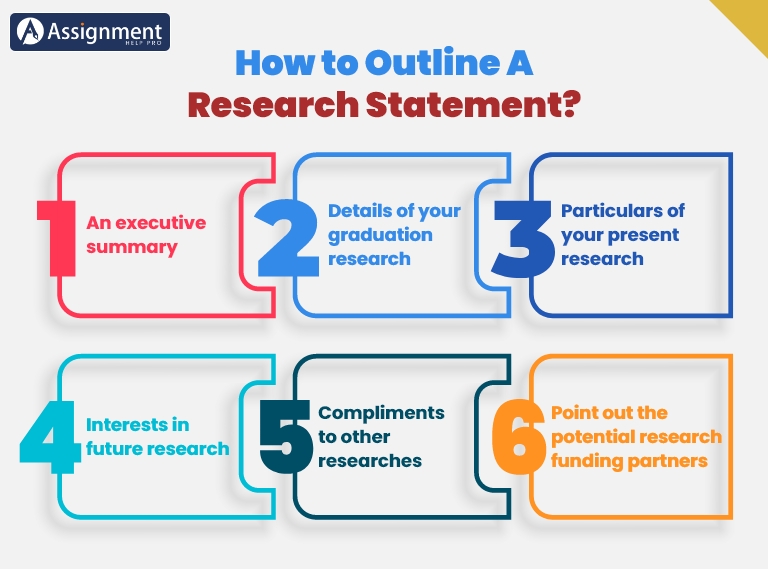

What Should It Include?

Your statement should start by articulating the broader field that you are working within and the larger question or questions that you are interested in answering. It should then move to articulate your specific interest.

The body of your statement should include a brief history of your past research . What questions did you initially set out to answer in your research project? What did you find? How did it contribute to your field? (i.e. did it lead to academic publications, conferences, or collaborations?). How did your past research propel you forward?

It should also address your present research . What questions are you actively trying to solve? What have you found so far? How are you connecting your research to the larger academic conversation? (i.e. do you have any publications under review, upcoming conferences, or other professional engagements?) What are the larger implications of your work?

Finally, it should describe the future trajectory on which you intend to take your research. What further questions do you want to solve? How do you intend to find answers to these questions? How can the institution to which you are applying help you in that process? What are the broader implications of your potential results?

Note: Make sure that the research project that you propose can be completed at the institution to which you are applying.

Other Considerations:

- What is the primary question that you have tried to address over the course of your academic career? Why is this question important to the field? How has each stage of your work related to that question?

- Include a few specific examples that show your success. What tangible solutions have you found to the question that you were trying to answer? How have your solutions impacted the larger field? Examples can include references to published findings, conference presentations, or other professional involvement.

- Be confident about your skills and abilities. The research statement is your opportunity to sell yourself to an institution. Show that you are self-motivated and passionate about your project.

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="what's a research statement"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Research statement, what is a research statement.

The research statement (or statement of research interests) is a common component of academic job applications. It is a summary of your research accomplishments, current work, and future direction and potential of your work.

The statement can discuss specific issues such as:

- funding history and potential

- requirements for laboratory equipment and space and other resources

- potential research and industrial collaborations

- how your research contributes to your field

- future direction of your research

The research statement should be technical, but should be intelligible to all members of the department, including those outside your subdiscipline. So keep the “big picture” in mind. The strongest research statements present a readable, compelling, and realistic research agenda that fits well with the needs, facilities, and goals of the department.

Research statements can be weakened by:

- overly ambitious proposals

- lack of clear direction

- lack of big-picture focus

- inadequate attention to the needs and facilities of the department or position

Why a Research Statement?

- It conveys to search committees the pieces of your professional identity and charts the course of your scholarly journey.

- It communicates a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be different, important, and innovative.

- It gives a context for your research interests—Why does your research matter? The so what?

- It combines your achievements and current work with the proposal for upcoming research.

- areas of specialty and expertise

- potential to get funding

- academic strengths and abilities

- compatibility with the department or school

- ability to think and communicate like a serious scholar and/or scientist

Formatting of Research Statements

The goal of the research statement is to introduce yourself to a search committee, which will probably contain scientists both in and outside your field, and get them excited about your research. To encourage people to read it:

- make it one or two pages, three at most

- use informative section headings and subheadings

- use bullets

- use an easily readable font size

- make the margins a reasonable size

Organization of Research Statements

Think of the overarching theme guiding your main research subject area. Write an essay that lays out:

- The main theme(s) and why it is important and what specific skills you use to attack the problem.

- A few specific examples of problems you have already solved with success to build credibility and inform people outside your field about what you do.

- A discussion of the future direction of your research. This section should be really exciting to people both in and outside your field. Don’t sell yourself short; if you think your research could lead to answers for big important questions, say so!

- A final paragraph that gives a good overall impression of your research.

Writing Research Statements

- Avoid jargon. Make sure that you describe your research in language that many people outside your specific subject area can understand. Ask people both in and outside your field to read it before you send your application. A search committee won’t get excited about something they can’t understand.

- Write as clearly, concisely, and concretely as you can.

- Keep it at a summary level; give more detail in the job talk.

- Ask others to proofread it. Be sure there are no spelling errors.

- Convince the search committee not only that you are knowledgeable, but that you are the right person to carry out the research.

- Include information that sets you apart (e.g., publication in Science, Nature, or a prestigious journal in your field).

- What excites you about your research? Sound fresh.

- Include preliminary results and how to build on results.

- Point out how current faculty may become future partners.

- Acknowledge the work of others.

- Use language that shows you are an independent researcher.

- BUT focus on your research work, not yourself.

- Include potential funding partners and industrial collaborations. Be creative!

- Provide a summary of your research.

- Put in background material to give the context/relevance/significance of your research.

- List major findings, outcomes, and implications.

- Describe both current and planned (future) research.

- Communicate a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be unique, significant, and innovative (and easy to fund).

Describe Your Future Goals or Research Plans

- Major problem(s) you want to focus on in your research.

- The problem’s relevance and significance to the field.

- Your specific goals for the next three to five years, including potential impact and outcomes.

- If you know what a particular agency funds, you can name the agency and briefly outline a proposal.

- Give broad enough goals so that if one area doesn’t get funded, you can pursue other research goals and funding.

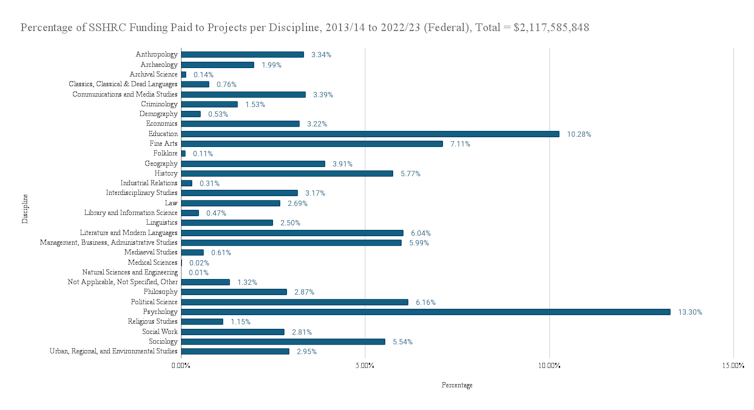

Identify Potential Funding Sources

- Almost every institution wants to know whether you’ll be able to get external funding for research.

- Try to provide some possible sources of funding for the research, such as NIH, NSF, foundations, private agencies.

- Mention past funding, if appropriate.

Be Realistic

There is a delicate balance between a realistic research statement where you promise to work on problems you really think you can solve and over-reaching or dabbling in too many subject areas. Select an over-arching theme for your research statement and leave miscellaneous ideas or projects out. Everyone knows that you will work on more than what you mention in this statement.

Consider Also Preparing a Longer Version

- A longer version (five–15 pages) can be brought to your interview. (Check with your advisor to see if this is necessary.)

- You may be asked to describe research plans and budget in detail at the campus interview. Be prepared.

- Include laboratory needs (how much budget you need for equipment, how many grad assistants, etc.) to start up the research.

Samples of Research Statements

To find sample research statements with content specific to your discipline, search on the internet for your discipline + “Research Statement.”

- University of Pennsylvania Sample Research Statement

- Advice on writing a Research Statement (Plan) from the journal Science

- Enhancing Student Success

- Innovative Research

- Alumni Success

- About NC State

How to Construct a Compelling Research Statement

A research statement is a critical document for prospective faculty applicants. This document allows applicants to convey to their future colleagues the importance and impact of their past and, most importantly, future research. You as an applicant should use this document to lay out your planned research for the next few years, making sure to outline how your planned research contributes to your field.

Some general guidelines

(from Carleton University )

An effective research statement accomplishes three key goals:

- It clearly presents your scholarship in nonspecialist terms;

- It places your research in a broader context, scientifically and societally; and

- It lays out a clear road map for future accomplishments in the new setting (the institution to which you’re applying).

Another way to think about the success of your research statement is to consider whether, after reading it, a reader is able to answer these questions:

- What do you do (what are your major accomplishments; what techniques do you use; how have you added to your field)?

- Why is your work important (why should both other scientists and nonscientists care)?

- Where is it going in the future (what are the next steps; how will you carry them out in your new job; does your research plan meet the requirements for tenure at this institution)?

1. Make your statement reader-friendly

A typical faculty application call can easily receive 200+ applicants. As such, you need to make all your application documents reader-friendly. Use headings and subheadings to organize your ideas and leave white space between sections.

In addition, you may want to include figures and diagrams in your research statement that capture key findings or concepts so a reader can quickly determine what you are studying and why it is important. A wall of text in your research statement should be avoided at all costs. Rather, a research statement that is concise and thoughtfully laid out demonstrates to hiring committees that you can organize ideas in a coherent and easy-to-understand manner.

Also, this presentation demonstrates your ability to develop competitive funding applications (see more in next section), which is critical for success in a research-intensive faculty position.

2. Be sure to touch on the fundability of your planned research work

Another goal of your research statement is to make the case for why your planned research is fundable. You may get different opinions here, but I would recommend citing open or planned funding opportunities at federal agencies or other funders that you plan to submit to. You might also use open funding calls as a way to demonstrate that your planned research is in an area receiving funding prioritization by various agencies.

If you are looking for funding, check out this list of funding resources on my personal website. Another great way to look for funding is to use NIH Reporter and NSF award search .

3. Draft the statement and get feedback early and often

I can tell you from personal experience that it takes time to refine a strong research statement. I went on the faculty job market two years in a row and found my second year materials to be much stronger. You need time to read, review and reflect on your statements and documents to really make them stand out.

It is important to have your supervisor and other faculty read and give feedback on your critical application documents and especially your research statement. Also, finding peers to provide feedback and in return giving them feedback on their documents is very helpful. Seek out communities of support such as Future PI Slack to find peer reviewers (and get a lot of great application advice) if needed.

4. Share with nonexperts to assess your writing’s clarity

Additionally, you may want to consider sharing your job materials, including your research statement, with non-experts to assess clarity. For example, NC State’s Professional Development Team offers an Academic Packways: Gearing Up for Faculty program each year where you can get feedback on your application documents from individuals working in a variety of areas. You can also ask classmates and colleagues working in different areas to review your research statement. The more feedback you can receive on your materials through formal or informal means, the better.

5. Tailor your statement to the institution

It is critical in your research statement to mention how you will make use of core facilities or resources at the institution you are applying to. If you need particular research infrastructure to do your work and the institution has it, you should mention that in your statement. Something to the effect of: “The presence of the XXX core facility at YYY University will greatly facilitate my lab’s ability to investigate this important process.”

Mentioning core facilities and resources at the target institution shows you have done your research, which is critical in demonstrating your interest in that institution.

Finally, think about the resources available at the institution you are applying to. If you are applying to a primarily undergraduate-serving institution, you will want to be sure you propose a research program that could reasonably take place with undergraduate students, working mostly in the summer and utilizing core facilities that may be limited or require external collaborations.

Undergraduate-serving institutions will value research projects that meaningfully involve students. Proposing overly ambitious research at a primarily undergraduate institution is a recipe for rejection as the institution will read your application as out of touch … that either you didn’t do the work to research them or that you are applying to them as a “backup” to research-intensive positions.

You should carefully think about how to restructure your research statements if you are applying to both primarily undergraduate-serving and research-intensive institutions. For examples of how I framed my research statement for faculty applications at each type of institution, see my personal website ( undergraduate-serving ; research-intensive research statements).

6. Be yourself, not who you think the search committee wants

In the end, a research statement allows you to think critically about where you see your research going in the future. What are you excited about studying based on your previous work? How will you go about answering the unanswered questions in your field? What agencies and initiatives are funding your type of research? If you develop your research statement from these core questions, your passion and commitment to the work will surely shine through.

A closing thought: Be yourself, not who you think the search committee wants. If you try to frame yourself as someone you really aren’t, you are setting the hiring institution and you up for disappointment. You want a university to hire you because they like you, the work you have done, and the work you want to do, not some filtered or idealized version of you.

So, put your true self out there, and realize you want to find the right institutional fit for you and your research. This all takes time and effort. The earlier you start and the more reflection and feedback you get on your research statement and remaining application documents, the better you can present the true you to potential employers.

More Advice on Faculty Job Application Documents on ImPACKful

How to write a better academic cover letter

Tips on writing an effective teaching statement

More Resources

See here for samples of a variety of application materials from UCSF.

- Rules of the (Social Sciences & Humanities) Research Statement

- CMU’s Writing a Research Statement

- UW’s Academic Careers: Research Statements

- Developing a Winning Research Statement (UCSF)

- Academic Packways

- ImPACKful Tips

Leave a Response Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

More From The Graduate School

Advice From Newly Hired Assistant Professors

Virtual Postdoc Research Symposium Elevates and Supports Postdoctoral Scholars Across North Carolina

Expand Your Pack: Start or Join an Online Writing Group!

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Write a Research Statement

Last Updated: May 19, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 64,563 times.

The research statement is a very common component of job applications in academia. The statement provides a summary of your research experience, interests, and agenda for reviewers to use to assess your candidacy for a position. Because the research statement introduces you as a researcher to the people reviewing your job application, it’s important to make the statement as impressive as possible. After you’ve planned out what you want to say, all you have to do is write your research statement with the right structure, style, and formatting!

Research Statement Outline and Example

Planning Your Research Statement

- For example, some of the major themes of your research might be slavery and race in the 18th century, the efficacy of cancer treatments, or the reproductive cycles of different species of crab.

- You may have several small questions that guide specific aspects of your research. Write all of these questions out, then see if you can formulate a broader question that encapsulates all of these smaller questions.

- For example, if your work is on x-ray technology, describe how your research has filled any knowledge gaps in your field, as well as how it could be applied to x-ray machines in hospitals.

- It’s important to be able to articulate why your research should matter to people who don’t study what you study to generate interest in your research outside your field. This is very helpful when you go to apply for grants for future research.

- Explain why these are the things you want to research next. Do your best to link your prior research to what you hope to study in the future. This will help give your reviewer a deeper sense of what motivates your research and why it matters.

- For example, if your research was historical and the documents you needed to answer your question didn’t exist, describe how you managed to pursue your research agenda using other types of documents.

- Some skills you might be able to highlight include experience working with digital archives, knowledge of a foreign language, or the ability to work collaboratively. When you're describing your skills, use specific, action-oriented words, rather than just personality traits. For example, you might write "speak Spanish" or "handled digital files."

- Don’t be modest about describing your skills. You want your research statement to impress whoever is reading it.

Structuring and Writing the Statement

- Because this section summarizes the rest of your research statement, you may want to write the executive summary after you’ve written the other sections first.

- Write your executive summary so that if the reviewer chooses to only read this section instead of your whole statement, they will still learn everything they need to know about you as an applicant.

- Make sure that you only include factual information that you can prove or demonstrate. Don't embellish or editorialize your experience to make it seem like it's more than it is.

- If you received a postdoctoral fellowship, describe your postdoc research in this section as well.

- If at all possible, include research in this section that goes beyond just your thesis or dissertation. Your application will be much stronger if reviewers see you as a researcher in a more general sense than as just a student.

- Again, as with the section on your graduate research, be sure to include a description of why this research matters and what relevant skills you bring to bear on it.

- If you’re still in graduate school, you can omit this section.

- Be realistic in describing your future research projects. Don’t describe potential projects or interests that are extremely different from your current projects. If all of your research to this point has been on the American civil war, future research projects in microbiology will sound very farfetched.

- For example, add a sentence that says “Dr. Jameson’s work on the study of slavery in colonial Georgia has served as an inspiration for my own work on slavery in South Carolina. I would welcome the opportunity to be able to collaborate with her on future research projects.”

- For example, if your research focuses on the history of Philadelphia, add a sentence to the paragraph on your future research projects that says, “I believe based on my work that I would be a very strong candidate to receive a Balch Fellowship from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.”

- If you’ve received funding for your research in the past, mention this as well.

- Typically, your research statement should be about 1-2 pages long if you're applying for a humanities or social sciences position. For a position in psychology or the hard sciences, your research statement may be 3-4 pages long.

- Although you may think that having a longer research statement makes you seem more impressive, it’s more important that the reviewer actually read the statement. If it seems too long, they may just skip it, which will hurt your application.

Formatting and Editing

- For example, instead of saying, “This part of my research was super hard,” say, “I found this obstacle to be particularly challenging.”

- For example, if your research is primarily in anthropology, refrain from using phrases like “Gini coefficient” or “moiety.” Only use phrases that someone in a different field would probably be familiar with, such as “cultural construct,” “egalitarian,” or “social division.”

- If you have trusted friends or colleagues in fields other than your own, ask them to read your statement for you to make sure you don’t use any words or concepts that they can’t understand.

- For example, when describing your dissertation, say, “I hypothesized that…” When describing your future research projects, say, “I intend to…” or “My aim is to research…”

- At the same time, don’t make your font too big. If you write your research statement in a font larger than 12, you run the risk of appearing unprofessional.

- For instance, if you completed a postdoc, use subheadings in the section on previous research experience to delineate the research you did in graduate school and the research you did during your fellowship.

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/graduate_school_applications/writing_a_research_statement.html

- ↑ https://www.cmu.edu/student-success/other-resources/handouts/comm-supp-pdfs/writing-research-statement.pdf

- ↑ https://postdocs.cornell.edu/research-statement

- ↑ https://gradschool.cornell.edu/academic-progress/pathways-to-success/prepare-for-your-career/take-action/research-statement/

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/executivesummary

- ↑ https://www.niu.edu/writingtutorial/style/formal-and-informal-style.shtml

- ↑ https://www.unl.edu/gradstudies/connections/writing-about-your-research-verb-tense

- ↑ https://www.unr.edu/writing-speaking-center/student-resources/writing-speaking-resources/editing-and-proofreading-techniques

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Apr 24, 2022

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

How to Write a Research Statement

- Experimental Psychology

Task #1: Understand the Purpose of the Research Statement

The primary mistake people make when writing a research statement is that they fail to appreciate its purpose. The purpose isn’t simply to list and briefly describe all the projects that you’ve completed, as though you’re a museum docent and your research publications are the exhibits. “Here, we see a pen and watercolor self-portrait of the artist. This painting is the earliest known likeness of the artist. It captures the artist’s melancholic temperament … Next, we see a steel engraving. This engraving has appeared in almost every illustrated publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and has also appeared as the television studio back-drop for the …”

Similar to touring through a museum, we’ve read through research statements that narrate a researcher’s projects: “My dissertation examined the ways in which preschool-age children’s memory for a novel event was shaped by the verbal dialogue they shared with trained experimenters. The focus was on the important use of what we call elaborative conversational techniques … I have recently launched another project that represents my continued commitment to experimental methods and is yet another extension of the ways in which we can explore the role of conversational engagement during novel events … In addition to my current experimental work, I am also involved in a large-scale collaborative longitudinal project …”

Treating your research statement as though it’s a narrated walk through your vita does let you describe each of your projects (or publications). But the format is boring, and the statement doesn’t tell us much more than if we had the abstracts of each of your papers. Most problematic, treating your research statement as though it’s a narrated walk through your vita misses the primary purpose of the research statement, which is to make a persuasive case about the importance of your completed work and the excitement of your future trajectory.

Writing a persuasive case about your research means setting the stage for why the questions you are investigating are important. Writing a persuasive case about your research means engaging your audience so that they want to learn more about the answers you are discovering. How do you do that? You do that by crafting a coherent story.

Task #2: Tell a Story

Surpass the narrated-vita format and use either an Op-Ed format or a Detective Story format. The Op-Ed format is your basic five-paragraph persuasive essay format:

First paragraph (introduction):

- broad sentence or two introducing your research topic;

- thesis sentence, the position you want to prove (e.g., my research is important); and

- organization sentence that briefly overviews your three bodies of evidence (e.g., my research is important because a, b, and c).

Second, third, and fourth paragraphs (each covering a body of evidence that will prove your position):

- topic sentence (about one body of evidence);

- fact to support claim in topic sentence;

- another fact to support claim in topic sentence;

- another fact to support claim in topic sentence; and

- analysis/transition sentence.

Fifth paragraph (synopsis and conclusion):

- sentence that restates your thesis (e.g., my research is important);

- three sentences that restate your topic sentences from second, third, and fourth paragraph (e.g., my research is important because a, b, and c); and

- analysis/conclusion sentence.

Although the five-paragraph persuasive essay format feels formulaic, it works. It’s used in just about every successful op-ed ever published. And like all good recipes, it can be doubled. Want a 10-paragraph, rather than five-paragraph research statement? Double the amount of each component. Take two paragraphs to introduce the point you’re going to prove. Take two paragraphs to synthesize and conclude. And in the middle, either raise six points of evidence, with a paragraph for each, or take two paragraphs to supply evidence for each of three points. The op-ed format works incredibly well for writing persuasive essays, which is what your research statement should be.

The Detective Story format is more difficult to write, but it’s more enjoyable to read. Whereas the op-ed format works off deductive reasoning, the Detective Story format works off inductive reasoning. The Detective Story does not start with your thesis statement (“hire/retain/promote/ award/honor me because I’m a talented developmental/cognitive/social/clinical/biological/perception psychologist”). Rather, the Detective Story starts with your broad, overarching research question. For example, how do babies learn their native languages? How do we remember autobiographical information? Why do we favor people who are most similar to ourselves? How do we perceive depth? What’s the best way to treat depression? How does the stress we experience every day affect our long-term health?

Because it’s your research statement, you can personalize that overarching question. A great example of a personalized overarching question occurs in the opening paragraph of George Miller’s (1956) article, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information.”

My problem is that I have been persecuted by an integer. For seven years this number has followed me around, has intruded in my most private data, and has assaulted me from the pages of our most public journals. This number assumes a variety of disguises, being sometimes a little larger and sometimes a little smaller than usual, but never changing so much as to be unrecognizable. The persistence with which this number plagues me is far more than a random accident. There is, to quote a famous senator, a design behind it, some pattern governing its appearances. Either there really is something unusual about the number or else I am suffering from delusions of persecution. I shall begin my case history by telling you about some experiments that tested how accurately people can assign numbers to the magnitudes of various aspects of a stimulus. …

In case you think the above opening was to a newsletter piece or some other low-visibility outlet, it wasn’t. Those opening paragraphs are from a Psych Review article, which has been cited nearly 16,000 times. Science can be personalized. Another example of using the Detective Story format, which opens with your broad research question and personalizes it, is the opening paragraph of a research statement from a chemist:

I became interested in inorganic chemistry because of one element: Boron. The cage structures and complexity of boron hydrides have fascinated my fellow Boron chemists for more than 40 years — and me for more than a decade. Boron is only one element away from carbon, yet its reactivity is dramatically different. I research why.

When truest to the genre of Detective Story format, the full answer to your introductory question won’t be available until the end of your statement — just like a reader doesn’t know whodunit until the last chapter of a mystery. Along the way, clues to the answer are provided, and false leads are ruled out, which keeps readers turning the pages. In the same way, writing your research statement in the Detective Story format will keep members of the hiring committee, the review committee, and the awards panel reading until the last paragraph.

Task #3: Envision Each Audience

The second mistake people make when writing their research statements is that they write for the specialist, as though they’re talking to another member of their lab. But in most cases, the audience for your research statement won’t be well-informed specialists. Therefore, you need to convey the importance of your work and the contribution of your research without getting bogged down in jargon. Some details are important, but an intelligent reader outside your area of study should be able to understand every word of your research statement.

Because research statements are most often included in academic job applications, tenure and promotion evaluations, and award nominations, we’ll talk about how to envision the audiences for each of these contexts.

Job Applications . Even in the largest department, it’s doubtful that more than a couple of people will know the intricacies of your research area as well as you do. And those two or three people are unlikely to have carte blanche authority on hiring. Rather, in most departments, the decision is made by the entire department. In smaller departments, there’s probably no one else in your research area; that’s why they have a search going on. Therefore, the target audience for your research statement in a job application comprises other psychologists, but not psychologists who study what you study (the way you study it).

Envision this target audience explicitly.Think of one of your fellow graduate students or post docs who’s in another area (e.g., if you’re in developmental, think of your friend in biological). Envision what that person will — and won’t — know about the questions you’re asking in your research, the methods you’re using, the statistics you’re employing, and — most importantly — the jargon that you usually use to describe all of this. Write your research statement so that this graduate student or post doc in another area in psychology will not only understand your research statement, but also find your work interesting and exciting.

Tenure Review . During the tenure review process, your research statement will have two target audiences: members of your department and, if your tenure case receives a positive vote in the department, members of the university at large. For envisioning the first audience, follow the advice given above for writing a research statement for a job application. Think of one of your departmental colleagues in another area (e.g., if you’re in developmental, think of your friend in biological). Write in such a way that the colleague in another area in psychology will understand every word — and find the work interesting. (This advice also applies to writing research statements for annual reviews, for which the review is conducted in the department and usually by all members of the department.)

For the second stage of the tenure process, when your research statement is read by members of the university at large, you’re going to have to scale it down a notch. (And yes, we are suggesting that you write two different statements: one for your department’s review and one for the university’s review, because the audiences differ. And you should always write with an explicit target audience in mind.) For the audience that comprises the entire university, envision a faculty friend in another department. Think political science or economics or sociology, because your statement will be read by political scientists, economists, and sociologists. It’s an art to hit the perfect pitch of being understood by such a wide range of scholars without being trivial, but it’s achievable.

Award Nominations . Members of award selection committees are unlikely to be specialists in your immediate field. Depending on the award, they might not even be members of your discipline. Find out the typical constitution of the selection committee for each award nomination you submit, and tailor your statement accordingly.

Task #4: Be Succinct

When writing a research statement, many people go on for far too long. Consider three pages a maximum, and aim for two. Use subheadings to help break up the wall of text. You might also embed a well-designed figure or graph, if it will help you make a point. (If so, use wrap-around text, and make sure that your figure has its axes labeled.)

And don’t use those undergraduate tricks of trying to cram more in by reducing the margins or the font size. Undoubtedly, most of the people reading your research statement will be older than you, and we old folks don’t like reading small fonts. It makes us crabby, and that’s the last thing you want us to be when we’re reading your research statement.

Nice piece of information. I will keep in mind while writing my research statement

Thank you so much for your guidance.

HOSSEIN DIVAN-BEIGI

Absolutely agree! I also want to add that: On the one hand it`s easy to write good research personal statement, but on the other hand it`s a little bit difficult to summarize all minds and as result the main idea of the statement could be incomprehensible. It also seems like a challenge for those guys, who aren`t native speakers. That`s why you should prepare carefully for this kind of statement to target your goals.

How do you write an action research topic?? An then stAte the problem an purpose for an action research. Can I get an example on language development?? Please I need some help.

Thankyou I now have idea to come up with the research statement. If I need help I will inform you …

much appreciated

Just like Boote & Beile (2005) explained “Doctors before researchers” because of the importance of the dissertation literature review in research groundwork.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Authors

Morton Ann Gernsbacher , APS Past President, is the Vilas Research Professor and Sir Frederic Bartlett Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She can be contacted at [email protected]. Patricia G. Devine , a Past APS Board Member, is Chair of the Department of Psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She can be contacted at [email protected].

Careers Up Close: Joel Anderson on Gender and Sexual Prejudices, the Freedoms of Academic Research, and the Importance of Collaboration

Joel Anderson, a senior research fellow at both Australian Catholic University and La Trobe University, researches group processes, with a specific interest on prejudice, stigma, and stereotypes.

Experimental Methods Are Not Neutral Tools

Ana Sofia Morais and Ralph Hertwig explain how experimental psychologists have painted too negative a picture of human rationality, and how their pessimism is rooted in a seemingly mundane detail: methodological choices.

APS Fellows Elected to SEP

In addition, an APS Rising Star receives the society’s Early Investigator Award.

Privacy Overview

Writing a Research Statement

What is a research statement.

A research statement is a short document that provides a brief history of your past research experience, the current state of your research, and the future work you intend to complete.

The research statement is a common component of a potential student's application for post-undergraduate study. The research statement is often the primary way for departments and faculty to determine if a student's interests and past experience make them a good fit for their program/institution.

Although many programs ask for ‘personal statements,' these are not really meant to be biographies or life stories. What we, at Tufts Psychology, hope to find out is how well your abilities, interests, experiences and goals would fit within our program.

We encourage you to illustrate how your lived experience demonstrates qualities that are critical to success in pursuing a PhD in our program. Earning a PhD in any program is hard! Thus, as you are relaying your past, present, and future research interests, we are interested in learning how your lived experiences showcase the following:

- Perseverance

- Resilience in the face of difficulty

- Motivation to undertake intensive research training

- Involvement in efforts to promote equity and inclusion in your professional and/or personal life

- Unique perspectives that enrich the research questions you ask, the methods you use, and the communities to whom your research applies

How Do I Even Start Writing One?

Before you begin your statement, read as much as possible about our program so you can tailor your statement and convince the admissions committee that you will be a good fit.

Prepare an outline of the topics you want to cover (e.g., professional objectives and personal background) and list supporting material under each main topic. Write a rough draft in which you transform your outline into prose. Set it aside and read it a week later. If it still sounds good, go to the next stage. If not, rewrite it until it sounds right.

Do not feel bad if you do not have a great deal of experience in psychology to write about; no one who is about to graduate from college does. Do explain your relevant experiences (e.g., internships or research projects), but do not try to turn them into events of cosmic proportion. Be honest, sincere, and objective.

What Information Should It Include?

Your research statement should describe your previous experience, how that experience will facilitate your graduate education in our department, and why you are choosing to pursue graduate education in our department. Your goal should be to demonstrate how well you will fit in our program and in a specific laboratory.

Make sure to link your research interests to the expertise and research programs of faculty here. Identify at least one faculty member with whom you would like to work. Make sure that person is accepting graduate students when you apply. Read some of their papers and describe how you think the research could be extended in one or more novel directions. Again, specificity is a good idea.

Make sure to describe your relevant experience (e.g., honors thesis, research assistantship) in specific detail. If you have worked on a research project, discuss that project in detail. Your research statement should describe what you did on the project and how your role impacted your understanding of the research question.

Describe the concrete skills you have acquired prior to graduate school and the skills you hope to acquire.

Articulate why you want to pursue a graduate degree at our institution and with specific faculty in our department.

Make sure to clearly state your core research interests and explain why you think they are scientifically and/or practically important. Again, be specific.

What Should It Look Like?

Your final statement should be succinct. You should be sure to thoroughly read and follow the length and content requirements for each individual application. Finally, stick to the points requested by each program, and avoid lengthy personal or philosophical discussions.

How Do I Know if It is Ready?

Ask for feedback from at least one professor, preferably in the area you are interested in. Feedback from friends and family may also be useful. Many colleges and universities also have writing centers that are able to provide general feedback.

Of course, read and proofread the document multiple times. It is not always easy to be a thoughtful editor of your own work, so don't be afraid to ask for help.

Lastly, consider signing up to take part in the Application Statement Feedback Program . The program provides constructive feedback and editing support for the research statements of applicants to Psychology PhD programs in the United States.

- Get Curious

- Talk to People

- Take Action

- Inspire Others

- Events and Outcomes

- JHU At-A-Glance

- Students and Schools

- Ready to Hire?

- Mentor Students

- Hire Students

- “When U Grow Up” Podcast

Writing an Effective Research Statement

- Share This: Share Writing an Effective Research Statement on Facebook Share Writing an Effective Research Statement on LinkedIn Share Writing an Effective Research Statement on X

Your browser doesn't support HTML video.

A research statement is a summary of research achievements and a proposal for upcoming research. It often includes both current aims and findings, and future goals. Research statements are usually requested as part of a relevant job application process, and often assist in the identification of appropriate applicants. Learn more about how to craft an effective research statement.

- Undergraduate Students

- Masters Students

- PhD/Doctoral Students

- Postdoctoral Scholars

- Faculty & Staff

- Families & Supporters

- Prospective Students

- Explore Your Interests / Self-Assessment

- Build your Network / LinkedIn

- Search for a Job / Internship

- Create a Resume / Cover Letter

- Prepare for an Interview

- Negotiate an Offer

- Prepare for Graduate School

- Find Funding Opportunities

- Prepare for the Academic Job Market

- Search for a Job or Internship

- Advertising, Marketing, and Public Relations

- Arts & Entertainment

- Consulting & Financial Services

- Engineering & Technology

- Government, Law & Policy

- Hospitality

- Management & Human Resources

- Non-Profit, Social Justice & Education

- Retail & Consumer Services

- BIPOC Students & Scholars

- Current & Former Foster Youth

- Disabled Students & Scholars

- First-Generation Students & Scholars

- Formerly Incarcerated Students & Scholars

- International Students & Scholars

- LGBTQ+ Students & Scholars

- Students & Scholars with Dependents

- Transfer Students

- Undocumented Students & Scholars

- Women-Identifying Students & Scholars

Research Statements

- Share This: Share Research Statements on Facebook Share Research Statements on LinkedIn Share Research Statements on X

A research statement is used when applying for some academic faculty positions and research-intensive positions. A research statement is usually a single-spaced 1-2 page document that describes your research trajectory as a scholar, highlighting growth: from where you began to where you envision going in the next few years. Ultimately, research productivity, focus and future are the most highly scrutinized in academic faculty appointments, particularly at research-intensive universities. Tailor your research statement to the institution to which you are applying – if a university has a strong research focus, emphasize publications; if a university values teaching and research equally, consider ending with a paragraph about how your research complements your teaching and vice versa. Structures of these documents also varies by discipline. See two common structures below.

Structure One:

Introduction: The first paragraph should introduce your research interests in the context of your field, tying the research you have done so far to a distinct trajectory that will take you well into the future.

Summary Of Dissertation: This paragraph should summarize your doctoral research project. Try not to have too much language repetition across documents, such as your abstract or cover letter.

Contribution To Field And Publications: Describe the significance of your projects for your field. Detail any publications initiated from your independent doctoral or postdoctoral research. Additionally, include plans for future publications based on your thesis. Be specific about journals to which you should submit or university presses that might be interested in the book you could develop from your dissertation (if your field expects that). If you are writing a two-page research statement, this section would likely be more than one paragraph and cover your future publication plans in greater detail.

Second Project: If you are submitting a cover letter along with your research statement, then the committee may already have a paragraph describing your second project. In that case, use this space to discuss your second project in greater depth and the publication plans you envision for this project. Make sure you transition from your dissertation to your second large project smoothly – you want to give a sense of your cohesion as a scholar, but also to demonstrate your capacity to conceptualize innovative research that goes well beyond your dissertation project.

Wider Impact Of Research Agenda: Describe the broader significance of your work. What ties your research projects together? What impact do you want to make on your field? If you’re applying for a teaching-oriented institution, how would you connect your research with your teaching?

Structure Two:

25% Previous Research Experience: Describe your early work and how it solidified your interest in your field. How did these formative experiences influence your research interests and approach to research? Explain how this earlier work led to your current project(s).

25% Current Projects: Describe your dissertation/thesis project – this paragraph could be modeled on the first paragraph of your dissertation abstract since it covers all your bases: context, methodology, findings, significance. You could also mention grants/fellowships that funded the project, publications derived from this research, and publications that are currently being developed.

50% Future Work: Transition to how your current work informs your future research. Describe your next major project or projects and a realistic plan for accomplishing this work. What publications do you expect to come out of this research? The last part of the research statement should be customized to demonstrate the fit of your research agenda with the institution.

Department of Psychology

Writing a research statement.

Ten Tips for Writing a Compelling Research Statement (A non-exhaustive list)

1. Focus on your intellectual interests and professional goals.

- Although many programs ask for ‘personal statements’, these are not really meant to be biographies or life stories. What we hope to find out is how well your abilities, interests, experiences and goals would fit within our program.

2. Describe your relevant experience (e.g., honors thesis, research assistantship) in specific detail.

- If you have worked on a research project, what was the research question, what were the hypotheses, how were they tested, and what did you find?

- Being specific shows us that you really were a key part of the project and that you understand what you did!

3. Whenever possible, demonstrate rather than simply state your knowledge.

- Not very convincing: “In this project, I learned a great deal about the psychology of persuasion”

- More convincing: “In this project, I learned about the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (Petty & Caccippo, 1986), and came to understand the importance of distinguishing between central and peripheral information processing when examining why different types of messages influence people."

4. Honestly identify concrete skills you would bring to graduate school, and also describe the skills you hope to acquire.

- For example: “I am familiar with conducting t-tests and ANOVAs in SPSS, but am eager to advance my statistical knowledge. In particular, structural equation modelling will be an important technique to learn given the types of research questions I intend to pursue.”

5. Articulate why you want to pursue a graduate degree.

- What are your career goals and how will pursuing a graduate degree advance them?

6. Articulate why you want to pursue a graduate degree at this specific institution !

- How can we help you achieve your goals?

7. Outline your core research interests and explain why you think they are scientifically and/or practically important. Again, be specific.

- Not very convincing: “I am interested in investigating why people discriminate against others because discrimination is a very important social problem."

- More convincing: “I am interested in investigating why people discriminate against others. In particular, I want to examine the role that implicit attitudes and stereotypes play in causing people to make biased decisions. Biased decisions – in hiring, promotion, law enforcement, and so on – can result in widespread societal disparities. Research by Correll, Park, Judd and Wittenbrink (2007), for example, suggests that racial disparities in shootings of suspects may be partially due to automatically activated stereotypes…”

8. Link your research interests to the expertise and research programs of faculty here.

- Identify at least one faculty member with whom you would like to work.

- Read some of their papers, and describe how you think the research could be extended in one or more novel directions. Again, specificity is a good idea.

- This is where you really have the opportunity to demonstrate your fit to a program and your ability to think critically, creatively and generatively about research.

9. Ask at least one professor at your current (or prior) institution to give you feedback on your statement.

10. Proofread! Or better yet, have a spelling and grammar-obsessed friend proofread your statement.

APPLY to our PhD or MS program

Program Description

- Welcome page - Program Highlights - Program Requirements - Areas of Specialization

Information about applying to our Graduate program

Current Graduate Students

Graduate Student News

Psych Graduate Handbook

Certificate Program Cognitive Science

University Resources CAS Graduate Programs College Graduate Handbook Graduate Student S enate Graduate Student Li fe

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))