Global warming frequently asked questions

We value your feedback

Help us improve our content

Related Content

News & features, climate change: atmospheric carbon dioxide, does it matter how much the united states reduces its carbon dioxide emissions if china doesn't do the same, how much will earth warm if carbon dioxide doubles pre-industrial levels, maps & data, air - atmospheric climate variables, land - terrestrial climate variables, what environmental data are relevant to the study of infectious diseases like covid-19, teaching climate, toolbox for teaching climate & energy, white house climate education and literacy initiative, climate youth engagement, climate resilience toolkit, annual greenhouse gas index, climate change indicators in the united states—2016, food safety and nutrition.

We're moving!

Understanding our planet to benefit humankind

News & features.

What Is Climate Change?

How do we know climate change is real, why is climate change happening, what are the effects of climate change, what is being done to solve climate change, earth science in action.

More to Explore

Ask nasa climate.

People Profiles

Images of Change

Before-and-after images of earth, climate change resources, an extensive collection of global warming resources for media, educators, weathercasters, and public speakers..

- Images of Change Before-and-after images of Earth

- Global Ice Viewer Climate change's impact on ice

- Earth Minute Videos Animated video series illustrating Earth science topics

- Climate Time Machine Climate change in recent history

- Multimedia Vast library of images, videos, graphics, and more

- En español Creciente biblioteca de recursos en español

- For Educators Student and educator resources

- For Kids Webquests, Climate Kids, and more

- Show search

Climate Change Stories

Climate Change FAQs

You asked. Our scientists answered. Use this guide to have the best info about climate change and how we can solve it together.

December 09, 2018 | Last updated November 13, 2023

Top Question: What Can I Do About Climate Change?

- Start a conversation. Talking about climate change is the best way to kickstart action , says Chief Scientist Kath arine Hayhoe.

- Vote at the ballot box (and the store). At every level, elected leaders have influence on policies that affect us all. And support companies taking climate action.

- Take personal action. Calculate your carbon footprint and share what you’ve learned to make action contagious.

Climate Change Basics

Click items to expand answers.

Each of these terms describes parts of the same problem—the fact that the average temperature of Earth is rising. As the planet heats up (global warming), we see broad impacts on Earth’s climate, such as shifting seasons, rising sea level, and melting ice.

As the impacts of climate change become more frequent and more severe, they will create—and in many cases they already are creating—crises for people and nature around the world. Many types of extreme weather, including heatwaves, heavy downpours, hurricanes and wildfires are becoming stronger and more dangerous.

Left unchecked, these impacts will spread and worsen, affecting our homes and cities, economies, food and water supplies as well as the species, ecosystems, and biodiversity of this planet we all call home.

All of these terms are accurate, and there’s no perfect one that will make everyone realize the urgency of action. Whatever you choose to call it, the most important thing is that we act to stop it.

Yes, scientists agree that the warming we are seeing today is entirely human-caused.

Climate has changed in the past due to natural factors such as volcanoes, changes in the sun’s energy and the way the Earth orbits the sun. In fact, these natural factors should be cooling the planet. However, our planet is warming.

Scientists have known for centuries that the Earth has a natural blanket of greenhouse or heat-trapping gases. This blanket keeps the Earth more than 30 degrees Celsius (over 60 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than it would be otherwise. Without this blanket, our Earth would be a frozen ball of ice.

Greenhouse gases, which include carbon dioxide and methane, trap some of the Earth’s heat that would otherwise escape to space. The more heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, the thicker the blanket and the warmer it gets.

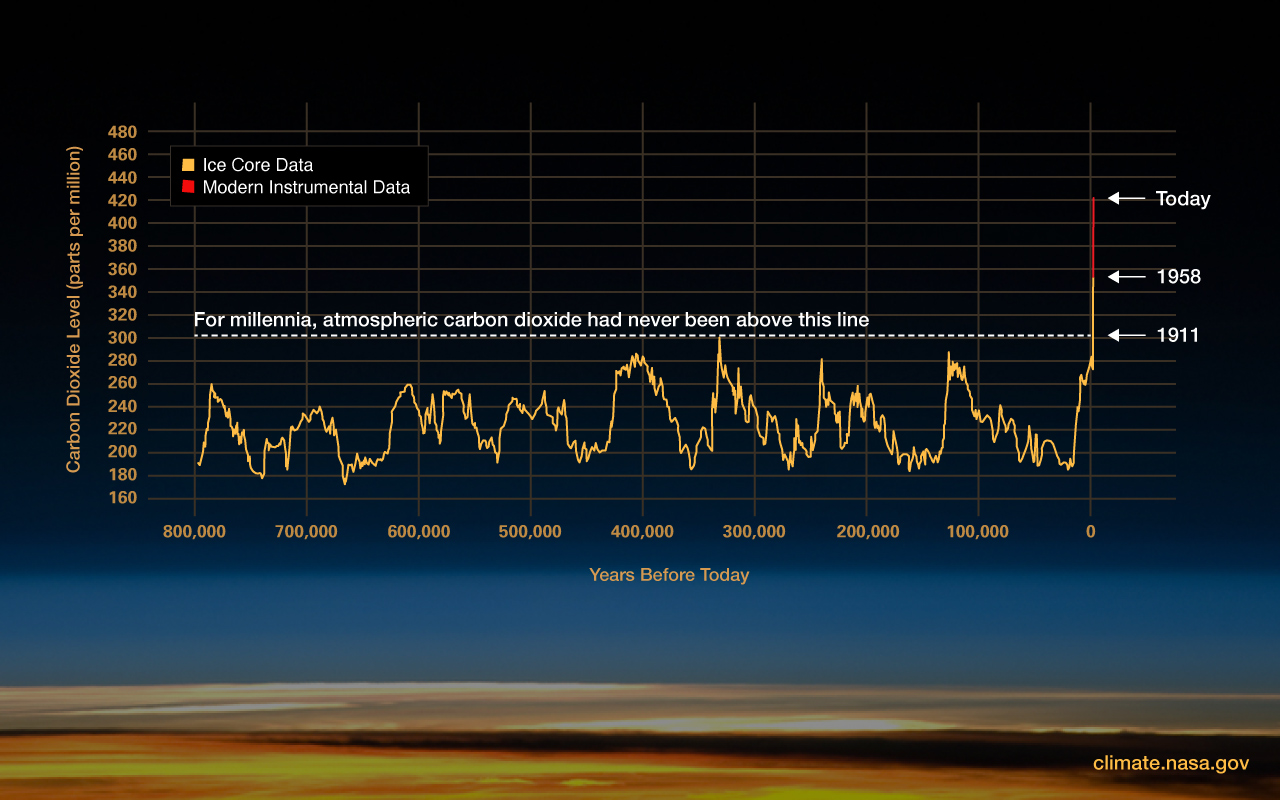

Over Earth’s history, heat-trapping gas levels have gone up and down due to natural factors. Today, however, by burning fossil fuels, causing deforestation ( forests are key parts of the planet’s natural carbon management systems), and operating large-scale industrial agriculture, humans are rapidly increasing levels of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere.

The human-caused increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is much greater than any observed in the paleoclimate history (i.e. ancient climate data measured through ice sheets, tree rings, sediments and more) of the earth. As a result, temperature in the air and ocean is now increasing faster than at any time in human history.

Scientists have looked at every other possible reason why climate might be changing today, and their conclusions are clear. There’s no question: it’s us.

One of the main reasons scientists are so worried about climate change is the speed at which it is occurring. In many cases, these changes are happening faster than animals, plants, and ecosystems can safely adapt to – and the same is true for human civilization.

We’ve never seen climate change this quickly, and it is putting our food and water systems, our infrastructure, and even our economies at risk. In some places, these changes are already crossing safe levels for ecosystems and humans.

That’s why, the more we do to mitigate these risks, the better off we will all be.

Effects of Climate Change

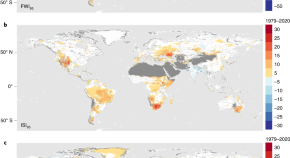

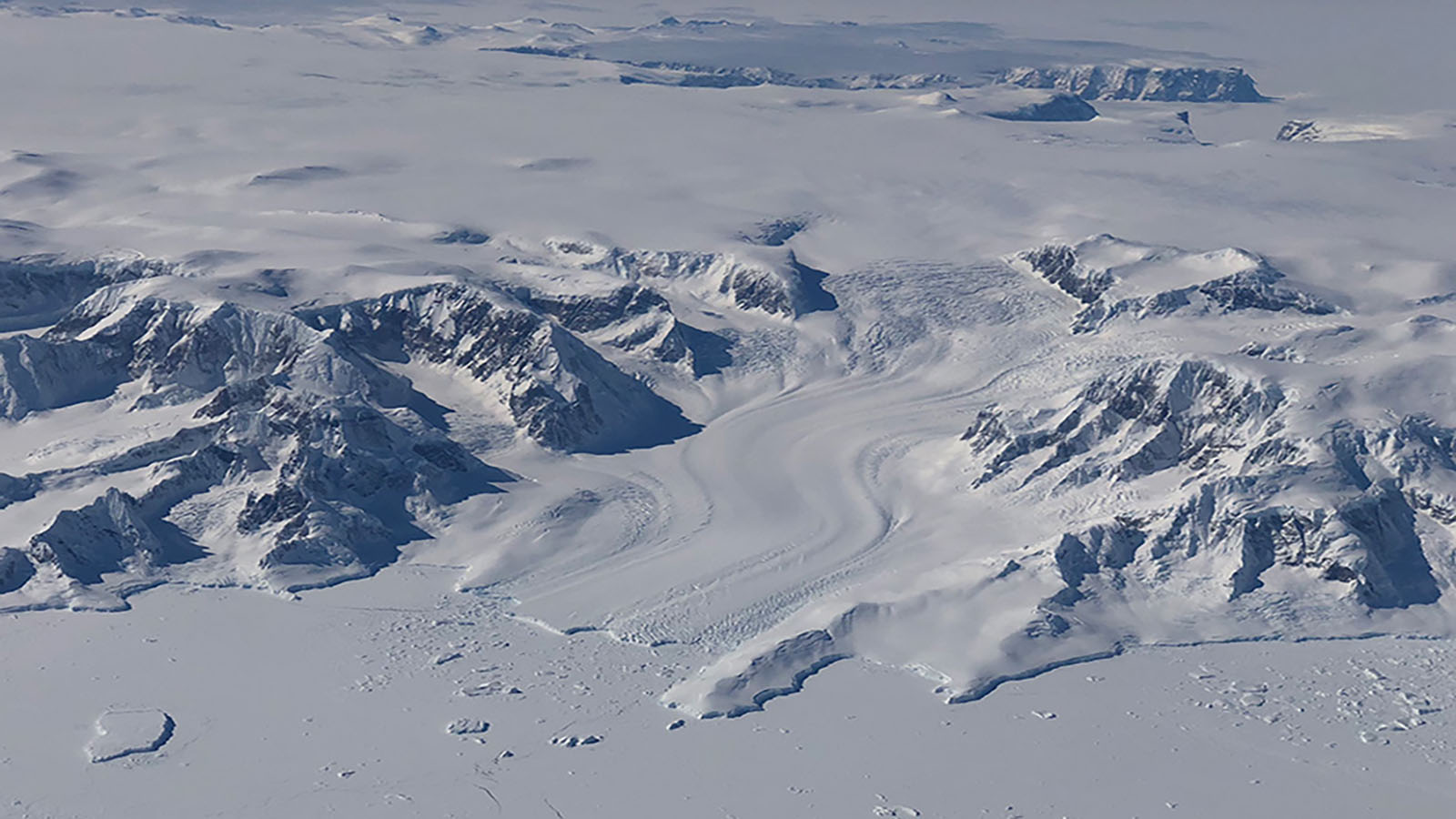

Climate change is affecting our planet in many ways. Average temperatures are increasing; rainfall patterns are shifting; snow lines are retreating; glaciers and ice sheets are melting; permafrost is thawing; sea levels are rising ; and severe weather is becoming more frequent.

In particular, heatwaves are becoming more frequent and more intense. Tropical cyclones like hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones are intensifying faster and dumping more rain. Wildfires are burning greater area, and in many areas around the world, heavy rainfall is becoming more frequent and droughts are getting stronger.

All of these impacts are concerning because they can harm and even potentially lead to the collapse of ecosystems and human systems. And it’s clear that they become more severe the more heat-trapping gases we produce.

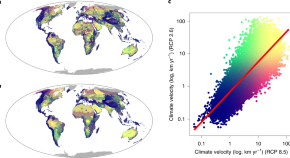

Rapid changes in climate can directly and indirectly impact animals across the world. Many species are approaching—or have already reached—the limit of where they can go to find hospitable climates. In the polar regions, animals like polar bears that live on sea ice are now struggling to survive as that ice melts.

It’s not just how climate change affects an animal directly; it’s about how the warming climate affects the ecosystem and food chain to which an animal has adapted. For example, in the U.S. and Canada, moose are being affected by an increase in ticks and parasites that are surviving the shorter, milder winters .

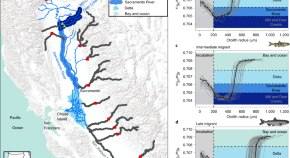

In western North America, salmon rely on steady-flowing cold rivers to spawn. As climate change alters the temperature and flow of these waterways, some salmon populations are dwindling. This change in salmon population affects many species that rely on salmon like orcas or grizzly bears.

Changes in temperature and moisture are causing some species to migrate in search of new places to live. For instance, in North America, species are shifting their ranges an average of 11 miles north and 36 feet higher in elevation each decade to find more favorable conditions. The Central Appalachians are one resilient climate escape route that may help species adapt to changing conditions.

There are some natural places with enough topographical diversity such that, even as the planet warms, they can be resilient strongholds for plant and animal species . These strongholds serve as breeding grounds and seed banks for many plants and animals that otherwise may be unable to find habitat due to climate change. However, strongholds are not an option for all species, and some plants and animals are blocked from reaching these areas by human development like cities, highways and farmland.

Here at The Nature Conservancy, we use science to identify such locations and work with local partners and communities to do everything we can to protect them.

From reducing agricultural productivity to threatening livelihoods and homes, climate change is affecting people everywhere. You may have noticed how weather patterns near you are shifting or how more frequent and severe storms are developing in the spring. Maybe your community is experiencing more severe flooding or wildfires .

Many areas are even experiencing “sunny day flooding” as rising sea levels cause streets to flood during high tides. In Alaska, some entire coastal communities are being moved because the sea level has risen and what used to be permanently frozen ground has thawed to the point where their original location is no longer habitable.

Climate change also exacerbates the threat of human-caused conflict resulting from a scarcity of resources like food and water that become less reliable as growing seasons change and rainfall patterns become less predictable.

Many of these impacts are disproportionately affecting low-income, Indigenous, or marginalized communities. For example, in large cities in North America, low-income communities are often hotter during heatwaves, more likely to flood during heavy downpours, and the last to have their power restored after storms.

Around the globe, many of the poorest nations are being impacted first and most severely by climate change, even though they have contributed far less to the carbon pollution that has caused the warming in the first place. Climate change affects us all, but it doesn’t affect us all equally: and that’s not fair.

Whether you live close to a coast or far from one, what happens in oceans matters to our lives .

Earlier, we described how greenhouse gases trap heat around the planet. Only a small fraction of the extra heat being trapped by the carbon pollution blanket is going into heating up the atmosphere. Almost 90% of the heat is going into the ocean, causing the ocean to warm.

Warmer water takes up more space, causing sea level to rise. As land-based ice melts, this addition of water from land to the ocean causes the ocean to rise even faster.

Warmer oceans can drive fish migrations and lead to coral bleaching and die off.

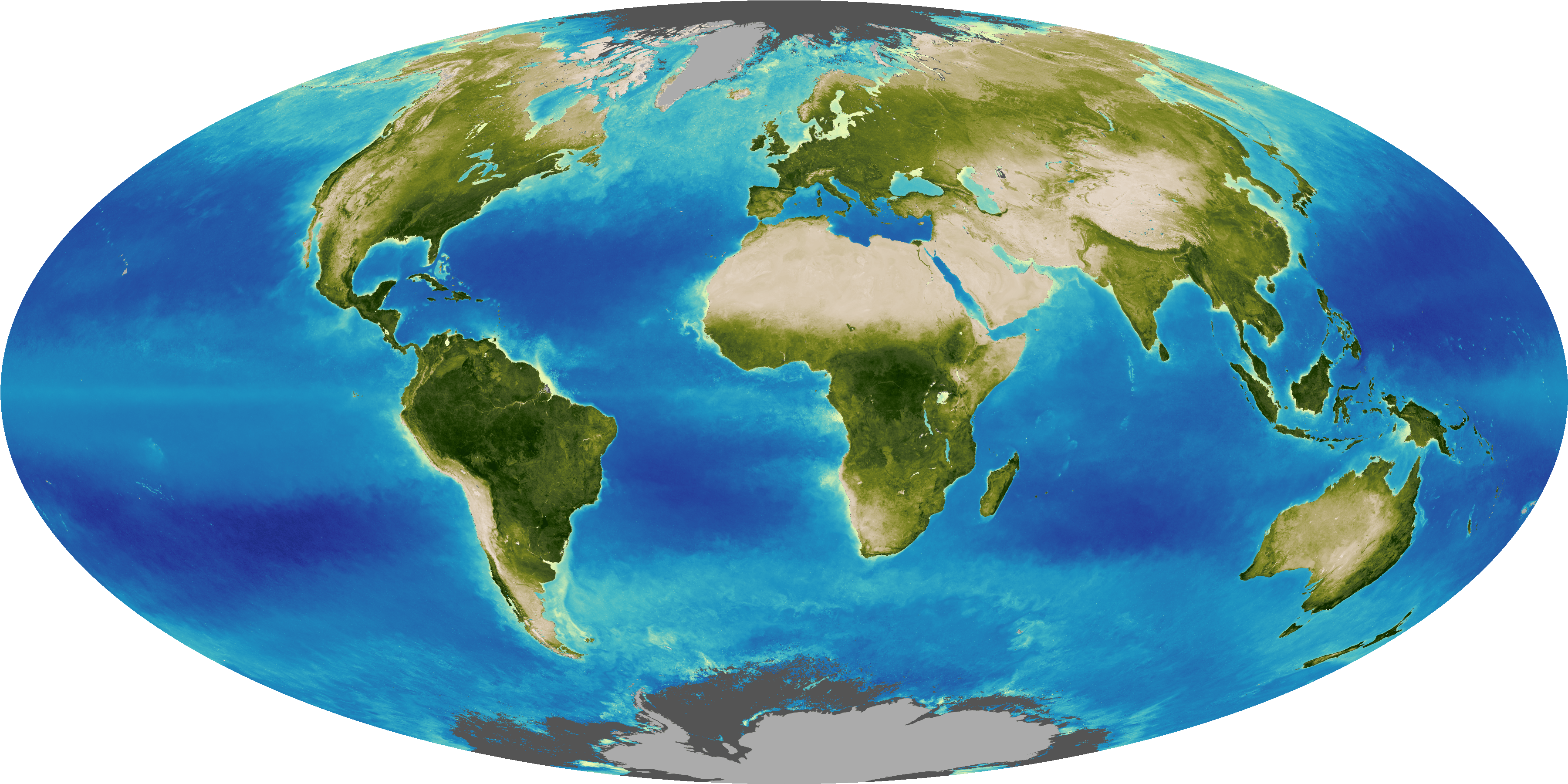

As the ocean surface warms, it’s less able to mix with deep, nutrient-rich water, which limits the growth of phytoplankton (little plants that serve as the base of the marine food web and that also produce a lot of the oxygen we breathe). This in turn affects the whole food chain.

In addition to taking up heat, the oceans are also absorbing about a quarter of the carbon pollution that humans produce. In addition to warming the air and water of our planet, some of this extra carbon dioxide is being absorbed by the ocean, making our oceans more acidic. In fact, the rate of ocean acidification is the highest it has been in 300 million years!

This acidification negatively impacts many marine habitats and animals, but is a particular threat to shellfish, which struggle to grow shells as water becomes more acidic.

There’s also evidence that warming surface waters may contribute to slowing ocean currents. These currents act like a giant global conveyor belt that transports heat from the tropics toward the poles. This conveyor belt is critical for bringing nutrient-rich waters towards the surface near the poles where giant blooms of food web-supporting phytoplankton occur (this is why the Arctic and Antarctic are known for having such high abundance of fish and marine mammals). With continued warming, these processes may be at risk.

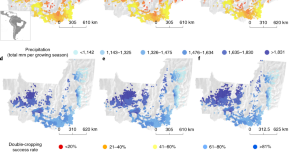

Climate change is disrupting weather patterns, leading to more extreme and frequent heatwaves, droughts, and flooding events that directly threaten harvests. Warmer seasons are also contributing to rising populations of insect pests that eat a higher share of crop yields, and higher carbon dioxide levels are causing plants to grow faster, while decreasing their nutritional content.

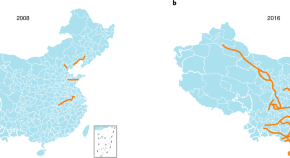

Flooding, drought, and heatwaves have decimated crops in China. In Bangladesh, rising sea levels are threatening rice crops. In the midwestern United States, more frequent and intense rains have caused devastating spring flooding, which delays—and sometimes prevents—planting activities.

These impacts make it more difficult for farmers to grow crops and sustain their livelihoods. Globally, one recent study finds that staple crop yield failures will be 4.5 times higher by 2030 and 25 times higher by mid-century. That means a major rice or wheat failure every other year, and higher probabilities of soybean and maize failures.

However, farmers are poised to play a significant role in addressing climate change. Agricultural lands are among the Earth’s largest natural reservoirs of carbon , and when farmers use soil health practices like cover crops, reduced tillage, and crop rotations, they can draw carbon out of the atmosphere .

These practices also help to improve the soil’s water-holding capacity, which is beneficial as water can be absorbed from the soil by crops during times of drought, and during heavy rainfalls, soil can help reduce flooding and run-off by slowing the release of water into streams.

Healthier soils can also improve crop yields, boost farmers’ profitability, and reduce erosion and fertilizer runoff from farm fields, which in turn means cleaner waterways for people and nature. That’s why climate-smart agriculture is a win-win!

Solutions to Climate Change

Yes, deforestation, land use change, and agricultural emissions are responsible for about a quarter of heat-trapping gas emissions from human activities. Agricultural emissions include methane from livestock digestion and manure, nitrous oxide from fertilizer use, and carbon dioxide from land use change.

Forests are one of our most important types of natural carbon storage , so when people cut down forests, they lose their ability to store carbon. Burning trees—either through wildfires or controlled burns-- releases even more carbon into the atmosphere.

Forests are some of the best natural climate solutions we have on this planet. If we can slow or stop deforestation , manage natural land so that it is healthy, and use other natural climate solutions such as climate-smart agricultural practices, we could achieve up to one third of the emission reductions needed by 2030 to keep global temperatures from rising more than 2°C (3.6°F). That’s the equivalent of the world putting a complete stop to burning oil.

When it comes to climate change, there’s no one solution that will fix it all. Rather, there are many solutions that, together, can address this challenge at scale while building a safer, more equitable, and greener world.

First, we need to reduce our heat-trapping gas emissions as much as possible, as soon as possible. Through efficiency and behavioral change, we can reduce the amount of energy we need.

At the same time, we have to transition all sectors of our economy away from fossil fuels that emit carbon, through increasing our use of clean energy sources like wind and solar. This transition will happen much faster and more cost-effectively if governments enact an economy-wide price on carbon.

Second, we need to harness the power of nature to capture carbon and deploy agricultural practices and technologies that capture and store carbon. Our research shows that proper land management of forests and farmlands, also called natural climate solutions, can provide up to one-third of the emissions reductions necessary to reach the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal.

The truth, however, is that even if we do successfully reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, we will still have to address harmful climate impacts. That’s why there is a third category of climate solutions that is equally important: adaptation to the impacts of global warming.

Adaptation consists of helping our human and natural systems prepare for the impacts of a warming planet. Greening urban areas helps protect them from heat and floods; restoring coastal wetlands helps protect from storm surge; increasing the diversity of ecosystems helps them to weather heat and drought; growing super-reefs helps corals withstand marine heatwaves. There are many ways we can use technology, behavioral change, and nature to work together to make us more resilient to climate impacts.

Climate change affects us all, but it doesn’t affect us all equally or fairly. We see how sea level rise threatens communities of small island states like Kiribati and the Solomon Islands and of low-lying neighborhoods in coastal cities like Mumbai, Houston and Lagos. Similarly, people living in many low-income neighborhoods in urban areas in North America are disproportionately exposed to heat and flood risk due to a long history of racist policies like redlining.

Those who have done the least to contribute to this problem often bear the brunt of the impacts and have the fewest resources to adapt. That’s why it is particularly important to help vulnerable communities adapt and become more resilient to climate change.

We need to increase renewable energy at least nine-fold from where it is today to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement and avoid the worst climate change impacts. Every watt that we can reduce through efficiency or shift from fossil fuel to renewables like wind power or solar power is a step in the right direction.

The best science we have tells us that to avoid the worst impacts of global warming, we must globally achieve net-zero carbon emissions no later than 2050. To do this, the world must immediately identify pathways to reduce carbon emissions from all sectors: transportation, agriculture, electricity, and industry. This cannot be achieved without a major shift to renewable energy.

Clean energy and technological innovation are not only helping mitigate climate change, but also helping create jobs and support economic growth in communities across the world. Renewable energy such as wind and solar have experienced remarkable growth and huge cost improvements over the past decade with no signs of slowing down.

Prices are declining rapidly, and renewable energy is becoming increasingly competitive with fossil fuels all around the world. In some places, new renewable energy is already cheaper than continuing to operate old, inefficient, and dirty fossil fuel-fired power plants.

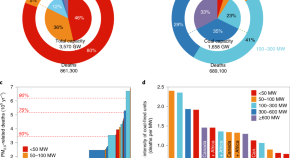

However, it’s important that renewable energy development isn’t built at the expense of protecting unique ecosystems or important agricultural lands. Without proactive planning, renewable energy developments could displace up to 76 million acres of farm and wildlife habitat—an area the size of Arizona.

Fortunately, TNC studies have found that we can meet clean energy demand 17 times over without converting more natural habitat. The key is to deploy new energy infrastructure on the wealth of previously converted areas such as agricultural lands, mine sites, and other transformed terrain, at a lower cost .

Thoughtful planning is required at every step. For instance, much of the United States’ wind potential is in the Great Plains, a region with the best remaining grassland habitat on the continent. TNC has mapped out the right places to site wind turbines in this region in order to catalyze renewable energy responsibly, and we’re doing the same analysis for India and Europe as well.

There can also be unique interventions to protect wildlife where clean energy has already been developed. In Kenya, for instance, a wind farm employs biodiversity monitors to watch for migrating birds , and can order individual turbines to shut down in less than a minute.

The Nature Conservancy is committed to tackling the dual crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. These two crises are, as our chief scientist says, two sides of the same coin .

What we do between now and 2030 will determine if we get on track to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement while also conserving enough land and water to slow accelerated species loss. That’s why we have ambitious 2030 goals that focus on people and the planet.

We're combatting these dual crises by:

- Enhancing nature’s ability to draw down and store carbon across forests, farmlands and wetlands by accelerating the deployment of natural climate solutions .

- Mobilizing action for a clean energy future and new, low-carbon technologies in harmony with nature.

- Supporting the leadership of Indigenous Peoples and local communities .

- Building resilience through natural defenses such as restored reefs, mangroves and wetlands that reduce the impact of storms and floods.

- Restoring and bolstering the resilience of vulnerable ecosystems like coral reefs and coastal wetlands.

- Helping countries around the globe, like India and Croatia , implement and enhance their commitments to the Paris Agreement.

Visit Our Goals for 2030 to learn more about TNC’s actions and partnerships to tackle climate change this decade.

Why We Must Urgently Act on Climate

Some amount of change has already occurred, and some future changes are inevitable due to our past choices. However, the good news is that we know what causes it and what to do to stop it. It will take courage, ambition, and a push to create change, but it can be done.

Reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050 is an ambitious goal, one that’s going to require substantial effort across every sector of the economy. We don’t have a lot of time, but if we are prepared to act now, and act together, we can substantially reduce the rate of global warming and prevent the worst impacts of climate change from coming to pass.

The even better news is that the low carbon economy that we need to create will also give us cleaner air, more abundant food and water, more affordable energy choices, and safer cities. Likewise, many of the solutions to even today’s climate change impacts benefit both people and nature.

When we really understand the benefits of climate action—how it will lead us to a world that is safer and healthier, more just and equitable—the only question we have left is: What are we waiting for?

Scientific studies show that climate change, if unchecked, would overwhelm our communities and pose an existential threat to certain ecosystems.

These catastrophic impacts include sea level rise from melting ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica that would flood most major global coastal cities; increasingly common and more severe storms, droughts, and heatwaves; massive crop failures and water shortages; and the large-scale destruction of habitats and ecosystems, leading to species extinctions .

To avoid the worst of climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says that “every bit of warming matters.” When it comes to limiting climate change, there’s no magic threshold: the faster we reduce our emissions, the better off we will be.

In 2015, all the countries in the world came together and signed the Paris Agreement . It’s a legally binding international treaty in which signatories agree to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C (3.5° F) above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C (2.7°F) above pre-industrial levels.”

Every day that goes by, we are releasing carbon into the atmosphere and increasing our planetary risk. Scientists agree that we need to begin reducing carbon emissions RIGHT NOW .

To reach the goal of the Paris Agreement, the world must make significant progress toward decarbonization (reducing carbon from the atmosphere and replacing fossil fuels in our economies) by 2030 and commit ourselves to reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050. This is no small feat and will require a range of solutions applied together, to reach the goal.

As the IPCC says, “every action matters.” You can be part of the climate change solution and you can activate others, too.

It’s really important that we use our voices for climate action. Tell your policy makers that you care about climate change and want to see them enact laws and policies that address greenhouse gas emissions and climate impacts.

One of the simplest—and most important—things that everyone can do is to talk about climate change with family and friends . We know these conversations can seem like a recipe for discord and hard feelings. It starts with meeting people where they are. TNC has resources to help you break the climate silence and pave the way for action on global warming.

You can also talk about climate change where you work, and with any other organization you’re part of. Join an organization that shares your values and priorities, to help amplify your voice. Collective change begins with understanding the risks climate change poses and the actions that can be taken together to reduce emissions and build resilience.

Lastly, you can calculate your carbon footprint and take actions individually or with your family and friends to lower it. You might be surprised which of your activities are emitting the most heat-trapping gases. But don’t forget to talk about the changes you’ve made, to help make them contagious —contagious in a good way, of course!

Stay connected for the latest news from nature.

Get global conservation stories, news and local opportunities near you. Check out a sample Nature News email.

Please provide a valid email address

You’ve already signed up with this email address. To review your email preferences, please visit nature.org/emailpreferences

We may have detected a typo. Please enter a valid email address (formatted as [email protected]). Did you mean to type ?

We are sorry, but there was a problem processing the reCAPTCHA response. Please contact us at [email protected] or try again later.

Talking About Climate

COP28: Your Guide to the 2023 UN Climate Change Conference in UAE

COP28 takes place November 30-December 12, 2023 in United Arab Emirates. This guide will tell you what to expect at COP28, why TNC will be there, and what it all means for you.

Food, Climate and Nature FAQs: Understanding the Food System’s Role in Healing Our Planet

You've got questions about food, farming, climate and nature. We've got answers and easy ways you can support regenerative food systems that help the planet.

Renewable Energy Transition

We no longer need to choose between abundant energy and a cleaner environment. A renewable energy revolution is happening across the globe.

News from the Columbia Climate School

Six Tough Questions About Climate Change

Whenever the focus is on climate change, as it is right now at the Paris climate conference , tough questions are asked concerning the costs of cutting carbon emissions, the feasibility of transitioning to renewable energy, and whether it’s already too late to do anything about climate change. We posed these questions to Laura Segafredo , manager for the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project . The decarbonization project comprises energy research teams from 16 of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitting countries that are developing concrete strategies to reduce emissions in their countries. The Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project is an initiative of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network .

- Will the actions we take today be enough to forestall the direct impacts of climate change? Or is it too little too late?

There is still time and room for limiting climate change within the 2˚C limit that scientists consider relatively safe, and that countries endorsed in Copenhagen and Cancun. But clearly the window is closing quickly. I think that the most important message is that we need to start really, really soon, putting the world on a trajectory of stabilizing and reducing emissions. The temperature change has a direct relationship with the cumulative amount of emissions that are in the atmosphere, so the more we keep emitting at the pace that we are emitting today, the more steeply we will have to go on a downward trajectory and the more expensive it will be.

Today we are already experiencing an average change in global temperature of .8˚. With the cumulative amount of emissions that we are going to emit into the atmosphere over the next years, we will easily reach 1.5˚ without even trying to change that trajectory.

Two degrees might still be doable, but it requires significant political will and fast action. And even 2˚ is a significant amount of warming for the planet, and will have consequences in terms of sea level rise, ecosystem changes, possible extinctions of species, displacements of people, diseases, agriculture productivity changes, health related effects and more. But if we can contain global warming within those 2˚, we can manage those effects. I think that’s really the message of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports—that’s why the 2˚ limit was chosen, in a sense. It’s a level of warming where we can manage the risks and the consequences. Anything beyond that would be much, much worse.

- Will taking action make our lives better or safer, or will it only make a difference to future generations?

It will make our lives better and safer for sure. For example, let’s think about what it means to replace a coal power plant with a cleaner form of energy like wind or solar. People that live around the coal power plant are going to have a lot less air pollution, which means less asthma for children, and less time wasted because of chronic or acute diseases. In developing countries, you’re talking about potentially millions of lives saved by replacing dirty fossil fuel based power generation with clean energy.

It will also have important consequences for agricultural productivity. There’s a big risk that with the concentration of carbon and other gases in the atmosphere, agricultural yields will be reduced, so preventing that means more food for everyone.

And then think about cities. If you didn’t have all that pollution from cars, we could live in cities that are less noisy, where the air’s much better, and have potentially better transportation. We could live in better buildings where appliances are more efficient. And investing in energy efficiency would basically leave more money in our pockets. So there are a lot of benefits that we can reap almost immediately, and that’s without even considering the biggest benefit—leaving a planet in decent condition for future generations.

- How will measures to cut carbon emissions affect my life in terms of cost?

To build a climate resilient economy, we need to incorporate the three pillars of energy system transformation that we focus on in all the deep decarbonization pathways. Number one is improving energy efficiency in every part of the economy—buildings, what we use inside buildings, appliances, industrial processes, cars…everything you can think of can perform the same service, but using less energy. What that means is that you will have a slight increase in the price in the form of a small investment up front, like insulating your windows or buying a more efficient car, but you will end up saving a lot more money over the life of the equipment in terms of decreased energy costs.

The second pillar is making electricity, the power sector, carbon-free by replacing dirty power generation with clean power sources. That’s clearly going to cost a little money, but those costs are coming down so quickly. In fact there are already a lot of clean technologies that are at cost parity with fossil fuels— for example, onshore wind is already as competitive as gas—and those costs are only coming down in the future. We can also expect that there are going to be newer technologies. But in any event, the fact that we’re going to use less power because of the first pillar should actually make it a wash in terms of cost.

The Australian deep decarbonization teams have estimated that even with the increased costs of cleaner cars, and more efficient equipment for the home, etc., when the power system transitions to where it’s zero carbon, you still have savings on your energy bills compared to the previous situation.

The third pillar that we think about are clean fuels, essentially zero-carbon fuels. So we either need to electrify everything— like cars and heating, once the power sector is free of carbon—or have low-carbon fuels to power things that cannot be electrified, such as airplanes or big trucks. But once you have efficiency, these types of equipment are also more efficient, and you should be spending less money on energy.

Saving money depends on the three pillars together, thinking about all this as a whole system.

- Given that renewable sources provide only a small percentage of our energy and that nuclear power is so expensive, what can we realistically do to get off fossil fuels as soon as possible?

There are a lot of studies that have been done for the U.S. and for Europe that show that it’s very realistic to think of a power sector that is almost entirely powered by renewables by 2050 or so. It’s actually feasible—and this considers all the issues with intermittency, dealing with the networks, and whatever else represents a technological barrier—that’s all included in these studies. There’s also the assumption that energy storage, like batteries, will be cheaper in the future.

That is the future, but 2050 is not that far away. 35 years for an energy transition is not a long time. It’s important that this transition start now with the right policy incentives in place. We need to make sure that cars are more efficient, that buildings are more efficient, that cities are built with more public transit so less fossil fuels are needed to transport people from one place to another.

I don’t want people to think that because we’re looking at 2050, that means that we can wait—in order to be almost carbon free by 2050, or close to that target, we need to act fast and start now.

- Will the remedies to climate change be worse than the disease? Will it drive more people into poverty with higher costs?

I actually think the opposite is true. If we just let climate go the way we are doing today by continuing business as usual, that will drive many people into poverty. There’s a clear relationship between climate change and changing weather patterns, so more significant and frequent extreme weather events, including droughts, will affect the livelihoods of a large portion of the world population. Once you have droughts or significant weather events like extreme precipitation, you tend to see displacements of people, which create conflict, and conflict creates disease.

I think Syria is a good example of the world that we might be going towards if we don’t do anything about climate change. Syria is experiencing a once-in-a-century drought, and there’s a significant amount of desertification going on in those areas, so you’re looking at more and more arid areas. That affects agriculture, so people have moved from the countryside to the cities and that has created a lot of pressure on the cities. The conflict in Syria is very much related to the drought, and the drought can be ascribed to climate change.

And consider the ramifications of the Syrian crisis: the refugee crisis in Europe, terrorism, security concerns and 7 million-plus people displaced. I think that that’s the world that we’re going towards. And in a world like that, when you have to worry about people being safe and alive, you certainly cannot guarantee wealth and better well-being, or education and health.

- So finally, doing what needs to be done to combat climate change all comes down to political will?

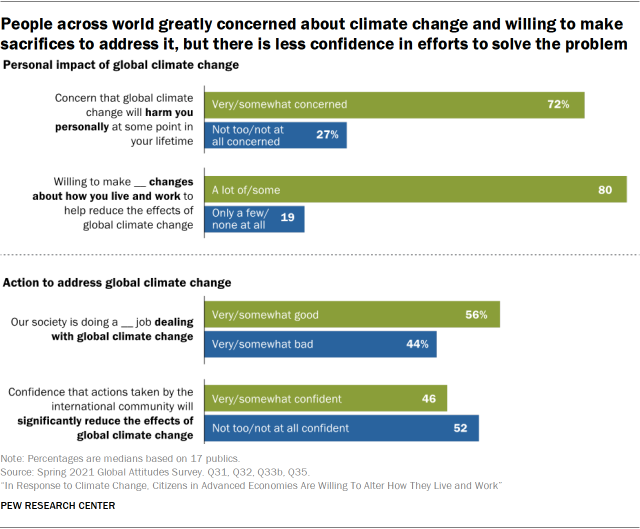

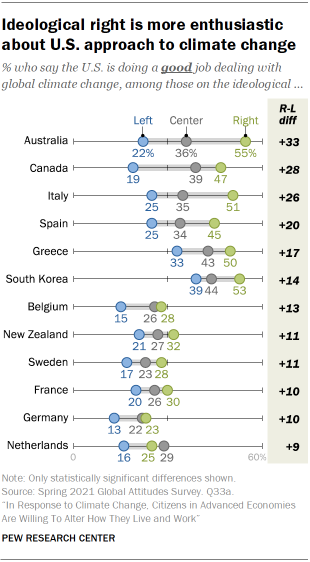

The majority of the American public now believe that climate change is real, that it’s human induced and that we should do something about it.

But there’s seems to be a disconnect between what these numbers seem to indicate and what the political discourse is like… I can’t understand it, yet it seems to be the situation.

I’m a little concerned because other more immediate concerns like terrorism and safety always come first. Because the effects of climate change are going to be felt a little further away, people think that we can always put it off. The Department of Defense, its top-level people, have made the connection between climate change and conflict over the next few decades. That’s why I would argue that Syria is actually a really good example to remind us that if we are experiencing security issues today, it’s also because of environmental problems. We cannot ignore them.

The reality is that we need to do something about climate change fast—we don’t have time to fight this over the next 20 years. We have to agree on this soon and move forward and not waste another 10 years debating.

Read the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project 2015 report . The full report will be released Dec. 2.

Laura Segafredo was a senior economist at the ClimateWorks Foundation, where she focused on best practice energy policies and their impact on emission trajectories. She was a lead author of the 2012 UNEP Emissions Gap Report and of the Green Growth in Practice Assessment Report. Before joining ClimateWorks, Segafredo was a research economist at Electricité de France in Paris.

She obtained her Ph.D. in energy studies and her BA in economics from the University of Padova (Italy), and her MSc in economics from the University of Toulouse (France).

Related Posts

In the Jersey Suburbs, a Search for Rocks To Help Fight Climate Change

Solar Geoengineering To Cool the Planet: Is It Worth the Risks?

Army Veteran and Environmental Advocate: A Sustainability Science Student’s Journey to Columbia

Celebrate over 50 years of Earth Day with us all month long! Visit our Earth Day website for ideas, resources, and inspiration.

Many find low wages prohibits saving. Changing personal vehicles and heating systems costs. Will there be financial support for people on low wages?

The energy innovation and dividend bill has already been introduced in the house. It’s a carbon fee and dividend plan. The carbon fee rises every year and 100% of it goes back directly into the hands of the people by a check each month. This helps offset rising costs, especially for lower income folks.

81 cosponsors now Tell your rep in Congress to support this HR 763!

Results show that yields for all four crops grown at levels of carbon dioxide remaining at 2000 levels would experience severe declines in yield due to higher temperatures and drier conditions. But when grown at doubled carbon dioxide levels, all four crops fare better due to increased photosynthesis and crop water productivity, partially offsetting the impacts from those adverse climate changes. For wheat and soybean crops, in terms of yield the median negative impacts are fully compensated, and rice crops recoup up to 90 percent and maize up to 60 percent of their losses.

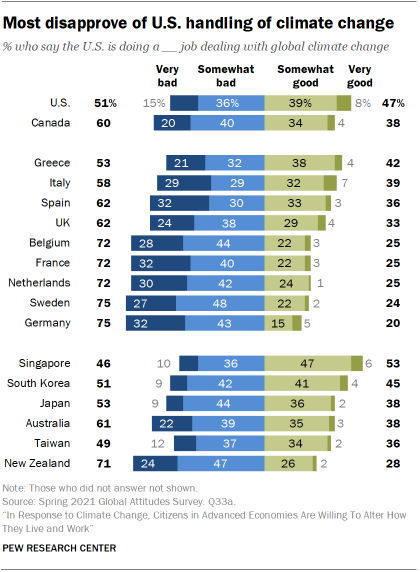

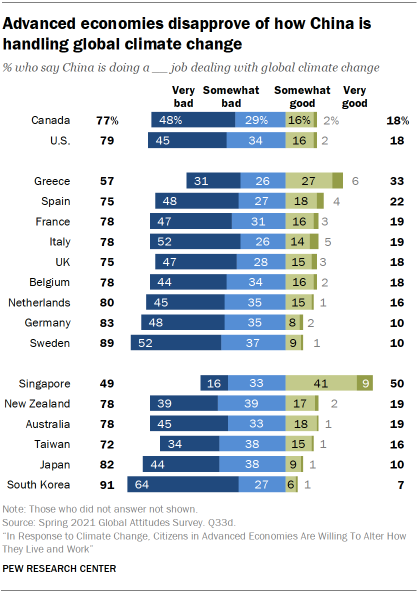

When is Russia, China, and Mexico going to work toward a better environment instead of the United States trying to do it all? They continue to pollute like they have for years. Who is going to stop the deforestation of the rain forest?

I’m curious if climate change has any effect on seismic activity. It seems with ice melting on the poles and increasing water dispersement and temp of that water, it might cause the plates to shift to compensate. Is there any evidence of this?

this isn’t because of doldrums or jet streams. the pattern keeps having the same action. we must save trees :3

How long do we have, before it’s too late?

Climate Change isn’t nearly as big of a deal as everyone makes it out to be. Meaning no disrespect to the author, but I really don’t see how this is something that we should be worrying about given that one human recycling their soda cans or getting their old phone refurbished rather than dumping it isn’t going to restore the polar ice caps or lower the temperature of the planet. And supposedly agriculture is the problem, but I point-blank refuse to give up my beef night, or bacon and eggs for breakfast on Saturdays. Also, nuclear power is supposed to be a solution, but the building of the power plants is going to add more greenhouse gases than the plant will take out. The whole planet needs a reality check. Earth isn’t going to explode because it’s slightly hotter than it used to be!

Thank you and I need in your help

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter →

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- TikTok’s fate

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- 9 questions about climate change you were too embarrassed to ask

Basic answers to basic questions about global warming and the future climate.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: 9 questions about climate change you were too embarrassed to ask

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55048475/North_America_from_low_orbiting_satellite_Suomi_NPP.0.jpg)

This explainer was updated by Umair Irfan in December 2018 and draws heavily from a card stack written by Brad Plumer in 2015. Brian Resnick contributed the section on the Paris climate accord in 2017.

There’s a vast and growing gap between the urgency to fight climate change and the policies needed to combat it.

In 2018, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that it is possible to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius this century, but the world may have as little as 12 years left to act. The US government’s National Climate Assessment , with input from NASA, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Pentagon, also reported that the consequences of climate change are already here, ranging from nuisance flooding to the spread of mosquito-borne viruses into what were once colder climates. Left unchecked, warming will cost the US economy hundreds of billions of dollars.

However, these facts have failed to register with the Trump administration, which is actively pushing policies that will increase the emissions of heat-trapping gases.

Ever since he took office, President Donald Trump has rejected or undermined President Barack Obama’s signature climate achievements: the Paris climate agreement; the Clean Power Plan , the main domestic policy for limiting greenhouse gas emissions; and fuel economy standards , which target transportation, the largest US source of greenhouse gases.

At the same time, the Trump administration has aggressively boosted fossil fuels: opening unprecedented swaths of public lands to mining and drilling , attempting to bail out foundering coal power plants , and promoting hydrocarbon exploitation at climate change conferences .

Trump has also appointed climate change skeptics to key positions. Quietly, officials at these and other science agencies have been removing the words “climate change” from government websites and press releases.

Yet the evidence for humanity’s role in changing the climate continues to mount, and its consequences are increasingly difficult to ignore. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations now top 408 parts per million, a threshold the planet hasn’t seen in millions of years . Greenhouse gas emissions reached a record high in 2018. Disasters worsened by climate change have taken hundreds of lives, destroyed thousands of homes, and cost billions of dollars.

The big questions now are how these ongoing changes in the climate will reverberate throughout the rest of the world, and what we should do about them. The answers bridge decades of research across geology, economics, and social science, which have been confounded by uncertainty and obscured by jargon. That’s why it can be a bit daunting to join the discussion for the first time, or to revisit the conversation after a hiatus.

To help, we’ve provided answers to some fundamental questions about climate change you may have been afraid to ask.

1) What is global warming?

In short: The world is getting hotter, and humans are responsible.

Yes, the planet’s temperature has changed before, but it’s the rise in average temperature of the Earth's climate system since the late 19th century, the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, that’s important here. Temperatures over land and ocean have gone up 0.8° to 1° Celsius (1.4° to 1.8° Fahrenheit), on average, in that span:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10346257/Screen_Shot_2018_03_05_at_10.29.11_AM.png)

Many people use the term “climate change” to describe this rise in temperatures and the associated effects on the Earth's climate. (The shift from the term “global warming” to “climate change” was also part of a deliberate messaging effort by a Republican pollster to undermine support for environmental regulations.)

Like detectives solving a murder, climate scientists have found humanity’s fingerprints all over the planet’s warming, with the overwhelming majority of the evidence pointing to the extra greenhouse gases humans have put into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide trap heat at the Earth’s surface, preventing that heat from escaping back out into space too quickly. When we burn coal, natural gas, or oil for energy, or when we cut down forests that usually soak up greenhouse gases, we add even more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, so the planet warms up.

Global warming also refers to what scientists think will happen in the future if humans keep adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

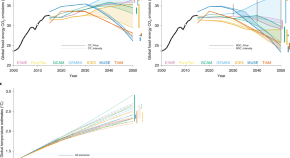

Though there is a steady stream of new studies on climate change, one of the most robust aggregations of the science remains the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s fifth assessment report from 2013. The IPCC is convened by the United Nations, and the report draws on more than 800 expert authors. It projects that temperatures could rise at least 2°C (3.6°F) by the end of the century under many plausible scenarios — and possibly 4°C or more. A more recent study by scientists in the United Kingdom found a narrower range of expected temperatures if atmospheric carbon dioxide doubled, rising between 2.2°C and 3.4°C.

Many experts consider 2°C of warming to be unacceptably high , increasing the risk of deadly heat waves, droughts, flooding, and extinctions. Rising temperatures will drive up global sea levels as the world’s glaciers and ice sheets melt. Further global warming could affect everything from our ability to grow food to the spread of disease.

That’s why the IPCC put out another report in 2018 comparing 2°C of warming to a scenario with 1.5°C of warming . The researchers found that this half-degree difference is actually pretty important, since every bit of warming matters. Between the two outlooks, less warming means fewer people will have to move from coastal areas, natural weather events will be less severe, and economies will take a smaller hit.

However, limiting warming would likely require a complete overhaul of our energy system. Fossil fuels currently provide just over 80 percent of the world’s energy. To zero out emissions this century, we’d have to replace most of that with low-carbon sources like wind, solar, nuclear, geothermal, or carbon capture.

Beyond that, we may have to electrify everything that uses energy and start pulling greenhouse gases straight from the air. And to get on track for 1.5°C of warming, the world would have to halve greenhouse gas emissions from current levels by 2030.

That’s a staggering task, and there are huge technological and political hurdles standing in the way. As such, the world's nations have been slow to act on global warming — many of the existing targets for curbing greenhouse gas emissions are too weak , yet many countries are falling short of even these modest goals.

2) How do we know global warming is real?

The simplest way is through temperature measurements. Agencies in the United States, Europe, and Japan have independently analyzed historical temperature data and reached the same conclusion: The Earth’s average surface temperature has risen roughly 0.8° Celsius (1.4° Fahrenheit) since the early 20th century.

But that’s not the only clue. Scientists have also noted that glaciers and ice sheets around the world are melting. Satellite observations since the 1970s have shown warming in the lower atmosphere. There’s more heat in the ocean, causing water to expand and sea levels to rise. Plants are flowering earlier in many parts of the world. There’s more humidity in the atmosphere. Here’s a summary from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8613575/HowDoWeKnowGWisReal.png)

These are all signs that the Earth really is getting warmer — and that it’s not just a glitch in the thermometers. That explains why climate scientists say things like , “Warming in the climate system is unequivocal.” They’re really confident about this one.

3) How do we know humans are causing global warming?

Climate scientists say they are more than 95 percent certain that human influence has been the dominant cause of global warming since 1950. They’re about as sure of this as they are that cigarette smoke causes cancer.

Why are they so confident? In part because they have a good grasp of how greenhouse gases can warm the planet, in part because the theory fits the available evidence, and in part because alternate theories have been ruled out. Let's break it down in six steps:

1) Scientists have long known that greenhouse gases in the atmosphere — such as carbon dioxide, methane, or water vapor — absorb certain frequencies of infrared radiation and scatter them back toward the Earth. These gases essentially prevent heat from escaping too quickly back into space, trapping that radiation at the surface and keeping the planet warm.

2) Climate scientists also know that concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have grown significantly since the Industrial Revolution. Carbon dioxide has risen 45 percent . Methane has risen more than 200 percent . Through some relatively straightforward chemistry and physics , scientists can trace these increases to human activities like burning oil, gas, and coal.

3) So it stands to reason that more greenhouse gases would lead to more heat. And indeed, satellite measurements have shown that less infrared radiation is escaping out into space over time and instead returning to the Earth’s surface. That’s strong evidence that the greenhouse effect is increasing.

4) There are other human fingerprints that suggest increased greenhouse gases are warming the planet. For instance, back in the 1960s, simple climate models predicted that global warming caused by more carbon dioxide would lead to cooling in the upper atmosphere (because the heat is getting trapped at the surface). Later satellite measurements confirmed exactly that . Here are a few other similar predictions that have also been confirmed.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8613609/HumansGW.jpg)

5) Meanwhile, climate scientists have ruled out other explanations for the rise in average temperatures over the past century. To take one example: Solar activity can shift from year to year, affecting the Earth's climate. But satellite data shows that total solar irradiance has declined slightly in the past 35 years, even as the Earth has warmed.

6) More recent calculations have shown that it’s impossible to explain the temperature rise we’ve seen in the past century without taking the increase in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into account. Natural causes, like the sun or volcanoes, have an influence, but they’re not sufficient by themselves.

Ultimately, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded that most of the warming since 1951 has been due to human activities. The Earth’s climate can certainly fluctuate from year to year due to natural forces (including oscillations in the Pacific Ocean, such as El Niño ). But greenhouse gases are driving the larger upward trend in temperatures.

And as the Climate Science Special Report , released by 13 US federal agencies in November 2017, put it, “For the warming over the last century, there is no convincing alternative explanation supported by the extent of the observational evidence.”

More: This chart breaks down all the different factors affecting the Earth’s average temperature. And there’s much more detail in the IPCC’s report , particularly this section and this one .

4) How has global warming affected the world so far?

Here’s a list of ongoing changes that climate scientists have concluded are likely linked to global warming, as detailed by the IPCC here and here .

Higher temperatures: Every continent has warmed substantially since the 1950s. There are more hot days and fewer cold days, on average, and the hot days are hotter.

Heavier storms and floods : The world’s atmosphere can hold more moisture as it warms. As a result, the overall number of heavier storms has increased since the mid-20th century, particularly in North America and Europe (though there’s plenty of regional variation). Scientists reported in December that at least 18 percent of Hurricane Harvey’s record-setting rainfall over Houston in August was due to climate change.

Heat waves: Heat waves have become longer and more frequent around the world over the past 50 years, particularly in Europe, Asia, and Australia.

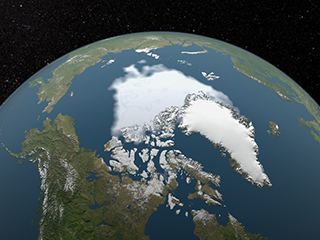

Shrinking sea ice: The extent of sea ice in the Arctic, always at its maximum in winter, has shrunk since 1979, by 3.3 percent per decade. Summer sea ice has dwindled even more rapidly, by 13.2 percent per decade. Antarctica has seen recent years with record growth in sea ice, but it’s a very different environment than the Arctic, and the losses in the north far exceed any gains at the South Pole, so total global sea ice is on the decline:

Global, Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice Area Spiral February 2018 #GlobalWarming #ClimateChange pic.twitter.com/gayoLFSJ5u — Kevin Pluck (@kevpluck) March 1, 2018

Shrinking glaciers and ice sheets : Glaciers around the world have, on average, been losing ice since the 1970s. In some areas, that is reducing the amount of available freshwater. The ice sheet on Greenland, which would raise global sea levels by 25 feet if it all melted, is declining, with some sections experiencing a sudden surge in the melt rate. The Antarctic ice sheet is also getting smaller, but at a much slower rate .

Sea level rise: Global sea levels rose 9.8 inches (25 centimeters) in the 19th and 20th centuries, after 2,000 years of relatively little change , and the pace is speeding up . Sea level rise is caused by both the thermal expansion of the oceans — as water warms up, it expands — and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets (but not sea ice).

Food supply: A hotter climate can be both good for crops (it lengthens the growing season, and more carbon dioxide can increase photosynthesis) and bad for crops (excess heat can damage plants). The IPCC found that global warming was currently benefiting crops in some high-latitude areas but that negative effects are becoming increasingly common worldwide. In areas like California, crop yields are estimated to decline 40 percent by 2050.

Shifting species: Many land and marine species have had to shift their geographic ranges in response to warmer temperatures. So far, several extinctions have been linked to global warming, such as certain frog species in Central America.

Warmer winters: In general, winters are warming faster than summers . Average low temperatures are rising all over the world. In some cases, these temperatures are climbing above the freezing point of water. We’re already seeing massive declines in snow accumulation in the United States, which can paradoxically increase flood, drought, and wildfire risk — as water that would ordinarily dispatch slowly over the course of a season instead flows through a region all at once.

Debated impacts

Here are a few other ways the Earth’s climate has been changing — but scientists are still debating whether and how they’re linked to global warming:

Droughts have become more frequent and more intense in some parts of the world — such as the American Southwest, Mediterranean Europe, and West Africa — though it’s hard to identify a clear global trend. In other parts of the world, such as the Midwestern United States and Northwestern Australia, droughts appear to have become less frequent. A recent study shows that, globally, the time between droughts is shrinking and more areas are affected by drought and taking longer to recover from them.

Hurricanes have clearly become more intense in the North Atlantic Ocean since 1970, the IPCC says. But it’s less clear whether global warming is driving this. 2017 was an exceptionally bad year for Atlantic hurricanes in terms of strength and damage. And while scientists are still uncertain whether they were a fluke or part of a trend, they are warning we should treat it as a baseline year. There doesn’t yet seem to be any clear trajectory for tropical cyclones worldwide.

5) What impacts will global warming have in the future?

It depends on how much the planet actually heats up. The changes associated with 4° Celsius (or 7.2° Fahrenheit) of warming are expected to be more dramatic than the changes associated with 2°C of warming.

Here’s a basic rundown of big impacts we can expect if global warming continues, via the IPCC ( here and here ).

Hotter temperatures: If emissions keep rising unchecked, then global average surface temperatures will be at least 2°C higher (3.6°F) than preindustrial levels by 2100 — and possibly 3°C or 4°C or more.

Higher sea level rise: The expert consensus is that global sea levels will rise somewhere between 0.2 and 2 meters by the end of the century if global warming continues unchecked (that’s between 0.6 and 6.6 feet). That’s a wide range, reflecting some of the uncertainties scientists have in how ice will melt. In specific regions like the Eastern United States, sea level rise could be even higher, and around the world, the rate of rise is accelerating .

Heat waves: A hotter planet will mean more frequent and severe heat waves .

Droughts and floods: Across the globe, wet seasons are expected to become wetter, and dry seasons drier. As the IPCC puts it , the world will see “more intense downpours, leading to more floods, yet longer dry periods between rain events, leading to more drought.”

Hurricanes: It’s not yet clear what impact global warming will have on tropical cyclones. The IPCC said it was likely that tropical cyclones would get stronger as the oceans heat up, with faster winds and heavier rainfall. But the overall number of hurricanes in many regions was likely to “either decrease or remain essentially unchanged.”

Heavier storm surges: Higher sea levels will increase the risk of storm surges and flooding when storms do hit.

Agriculture: In many parts of the world, the mix of increased heat and drought is expected to make food production more difficult. The IPCC concluded that global warming of 1°C or more could start hurting crop yields for wheat, corn, and rice by the 2030s, especially in the tropics. (This wouldn’t be uniform, however; some crops may benefit from mild warming, such as winter wheat in the United States.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8613683/WGII_AR5_Fig7_4.jpg)

Extinctions: As the world warms, many plant and animal species will need to shift habitats at a rapid rate to maintain their current conditions. Some species will be able to keep up; others likely won’t. The Great Barrier Reef, for instance, may not be able to recover from major recent bleaching events linked to climate change. The National Research Council has estimated that a mass extinction event “could conceivably occur before the year 2100.”

Long-term changes: Most of the projected changes above will occur in the 21st century. But temperatures will keep rising after that if greenhouse gas levels aren’t stabilized. That increases the risk of more drastic longer-term shifts. One example: If West Antarctica’s ice sheet started crumbling, that could push sea levels up significantly. The National Research Council in 2013 deemed many of these rapid climate surprises unlikely this century but a real possibility further into the future.

6) What happens if the world heats up more drastically — say, 4°C?

The risks of climate change would rise considerably if temperatures rose 4° Celsius (7.2° Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels — something that’s possible if greenhouse gas emissions keep rising at their current rate.

The IPCC says 4°C of global warming could lead to “substantial species extinctions,” “large risks to global and regional food security,” and the risk of irreversibly destabilizing Greenland’s massive ice sheet.

One huge concern is food production: A growing number of studies suggest it would become significantly more difficult for the world to grow food with 3°C or 4°C of global warming. Countries like Bangladesh, Egypt, Vietnam, and parts of Africa could see large tracts of farmland turn unusable due to rising seas. Scientists are also concerned about crops getting less nutritious due to rising CO2.

Humans could struggle to adapt to these conditions. Many people might think the impacts of 4°C of warming will simply be twice as bad as those of 2°C. But as a 2013 World Bank report argued, that’s not necessarily true. Impacts may interact with each other in unpredictable ways. Current agriculture models, for instance, don’t have a good sense of what will happen to crops if increased heat waves, droughts, new pests and diseases, and other changes all start to combine.

“Given that uncertainty remains about the full nature and scale of impacts,” the World Bank report said, “there is also no certainty that adaptation to a 4°C world is possible.” Its conclusion was blunt: “The projected 4°C warming simply must not be allowed to occur.”

7) What do climate models say about the warming that could actually happen in the coming decades?

That depends on your faith in humanity.

Climate models depend on not only complicated physics but the intricacies of human behavior over the entire planet.

Generally, the more greenhouse gases humanity pumps into the atmosphere, the warmer it will get. But scientists aren’t certain how sensitive the global climate system is to increases in greenhouse gases. And just how much we might emit over the coming decades remains an open question, depending on advances in technology and international efforts to cut emissions.

The IPCC groups these scenarios into four categories of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations known as Representative Concentration Pathways . They serve as standard benchmarks for evaluating climate models, but they also have some assumptions baked in .

RCP 2.6, also called RCP 3PD, is the scenario with very low greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. It bets on declining oil use, a population of 9 billion by 2100, increasing energy efficiency, and emissions holding steady until 2020, at which point they’ll decline and even go negative by 2100. This is, to put it mildly, very optimistic.

The next tier up is RCP 4.5, which still banks on ambitious reductions in emissions but anticipates an inflection point in the emissions rate around 2040. RCP 6 expects emissions to increase 75 percent above today’s levels before peaking and declining around 2060 as the world continues to rely heavily on fossil fuels.

The highest tier, RCP 8.5, is the pessimistic business-as-usual scenario, anticipating no policy changes nor any technological advances. It expects a global population of 12 billion and triple the rate of carbon dioxide emissions compared to today by 2100.

Here’s how greenhouse gas emissions under each scenario stack up next to each other:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10350069/RCP_IEA_Emissions.jpg)

And here’s what that means for global average temperatures, assuming that a doubling of carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere leads to 3°C of warming:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10350081/3C_Sensitivity.jpg)

As you can see, RCP 3PD is the only trajectory that keeps the planet below 2°C of warming. Recall what it would take to keep emissions in line with this pathway and you’ll understand the enormity of the challenge of meeting this goal.

8) How do we stop global warming?

The world’s nations would need to cut their greenhouse gas emissions by a lot. And even that wouldn’t stop all global warming.

For example, let’s say we wanted to limit global warming to below 2°C. To do that, the IPCC has calculated that annual greenhouse gas emissions would need to drop at least 40 to 70 percent by midcentury.

Emissions would then have to keep falling until humans were hardly emitting any extra greenhouse gases by the end of the century. We’d also have to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere .

Cutting emissions that sharply is a daunting task. Right now, the world gets 87 percent of its primary energy from fossil fuels: oil, gas, and coal. By contrast, just 13 percent of the world’s primary energy is “low carbon”: a little bit of wind and solar power, some nuclear power plants, a bunch of hydroelectric dams. That’s one reason global emissions keep rising each year.

To stay below 2°C, that would all need to change radically. By 2050, the IPCC notes, the world would need to triple or even quadruple the share of clean energy it uses — and keep scaling it up thereafter. Second, we’d have to get dramatically more efficient at using energy in our homes, buildings, and cars. And stop cutting down forests. And reduce emissions from agriculture and from industrial processes like cement manufacturing.

The IPCC also notes that this task becomes even more difficult the longer we put it off, because carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases will keep piling up in the atmosphere in the meantime, and the cuts necessary to stay below the 2°C limit become more severe.

9) What are we actually doing to fight climate change?

A global problem requires global action, but with climate change, there is a yawning gap between ambition and action.

The main international effort is the 2015 Paris climate accord, of which the United States is the only country in the world that wants out . The deal was hammered out over weeks of tense negotiations and weighs in at 31 pages . What it does is actually pretty simple.

The backbone is the global target of keeping global average temperatures from rising 2°C (compared to temperatures before the Industrial Revolution) by the end of the century. Beyond 2 degrees, we risk dramatically higher seas, changes in weather patterns, food and water crises, and an overall more hostile world.

Critics have argued that the 2-degree mark is arbitrary, or even too low , to make a difference. But it’s a starting point, a goal that, before Paris, the world was on track to wildly miss.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7291239/global_CO2_emissions_graphic.jpg)

Paris is voluntary

To accomplish this 2-degree goal, the accord states that countries should strive to reach peak emissions “as soon as possible.” (Currently, we’re on track to hit peak emissions around 2030 or later , which will likely be too late.)

But the agreement doesn’t detail exactly how these countries should do that. Instead, it provides a framework for getting momentum going on greenhouse gas reduction, with some oversight and accountability. For the US, the pledge involves 26 to 28 percent reductions by 2025. (Under Trump’s current policies, that goal is impossible .)

There’s also no defined punishment for breaking it. The idea is to create a culture of accountability (and maybe some peer pressure) to get countries to step up their climate game.

In 2020, delegates are supposed to reconvene and provide updates about their emission pledges and report on how they’re becoming more aggressive on accomplishing the 2-degree goal.

However, many countries are already falling behind on their climate change commitments, and some, like Germany, are giving up on their near-term targets.

Paris asks richer countries to help out poorer countries

There’s a fundamental inequality when it comes to global emissions. Rich countries have plundered and burned huge amounts of fossil fuels and gotten rich from them. Poor countries seeking to grow their economies are now being admonished for using the same fuels. Many low-lying poor countries also will be among the first to bear the worst impacts of climate change.

The main vehicle for rectifying this is the Green Climate Fund , via which richer countries, like the US, are supposed to send $100 billion a year in aid and financing by 2020 to the poorer countries. The United States’ share was $3 billion , but with President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris accord, this goal is unlikely to be met.

The agreement matters because we absolutely need momentum on this issue

The Paris agreement is largely symbolic, and it will live on even though Trump is aiming to pull the US out. But, as Jim Tankersley wrote for Vox , “the accord will be weakened, and, much more importantly, so will the fragile international coalition” around climate change.

We’re already seeing the Paris agreement lose steam. At a follow-up climate meeting this year in Katowice, Poland , negotiators forged an agreement on measuring and verifying their progress in cutting greenhouse gases, but left many critical questions of how to achieve these reductions unanswered.

But the Paris accord isn’t the only international climate policy game in town

There are regional international climate efforts like the European Union’s Emissions Trading System . However, the most effective global policy at keeping warming in check to date doesn’t have to do with climate change, at least on the surface.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol , which was convened by countries to halt the destruction of the ozone layer, had a major side effect of averting warming. In fact, it’s been the single most effective effort humanity has undertaken to fight climate change. Since many of the substances that eat away at the ozone layer are potent heat-trappers, limiting emissions of gases like chlorofluorocarbons has an outsize effect.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10354423/Screen_Shot_2017_11_27_at_2.33.42_PM.png)

And the Trump administration doesn’t appear as hostile to Montreal as it does to Paris. The White House may send the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol to the Senate for ratification, giving the new regulations the force of law. If implemented, the amendment would avert 0.5°C of warming by 2100.

Regardless of what path we choose, the key thing to remember is that we are going to pay for climate change one way or another. We have the opportunity now to address warming on our own terms, with investments in clean energy, moving people away from disaster-prone areas, and regulating greenhouse gas emissions. Otherwise, we’ll pay through diminished crop harvests, inundated coastlines, destroyed homes, lost lives, and an increasingly unlivable planet. Ignoring or stalling on climate change chooses the latter option by default. Our choices do matter, but we’re running out of time to make them.

F urther reading:

Avoiding catastrophic climate change isn’t impossible yet. Just incredibly hard.

Reckoning with climate change will demand ugly tradeoffs from environmentalists — and everyone else

Show this cartoon to anyone who doubts we need huge action on climate change

It’s time to start talking about “negative” carbon dioxide emissions

A history of the 2°C global warming target

Scientists made a detailed “roadmap” for meeting the Paris climate goals. It’s eye-opening.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

In This Stream

Trump withdraws the us from paris climate agreement.

- The rumors that Trump was changing course on the Paris climate accord, explained

Next Up In Science

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

No one wants to think about pandemics. But bird flu doesn’t care.

The Supreme Court: The most powerful, least busy people in Washington

You could soon get cash for a delayed flight

Baby Reindeer’s messy stalking has led to more messy stalking offscreen

Challengers is the best thing that could happen to polyamory

Why America’s Israel-Palestine debate is broken — and how to fix it

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

Climate Change Research

Fifth national climate assessment.

Check out NCA5, the most comprehensive analysis of the state of climate change in the United States.

Explore NCA5

EPA’s Climate Change Research seeks to improve our understanding of how climate change impacts human health and the environment.

Air Quality

Researching how changes in climate can affect air quality.

Community Resilience

Research to empower communities to become more resilient to climate change.

Ecosystems & Water Quality

Research to understand how climate change is affecting these resources now and in the future.

Researching how energy production will impact climate and the environment.

Human Health

Research to understand how a changing climate will impact human health.

Tools & Resources

Decision support tools, models & databases, research grants, outreach, and educational resources.

More Resources

- Publications, Presentations, and Other Research Products in Science Inventory

- Climate Change Research Milestones

- EPA's Climate Change Homepage

- EPA's Climate Adaptation Plan

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Research articles

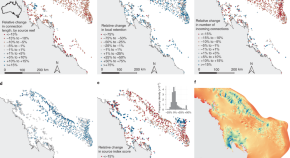

Global warming decreases connectivity among coral populations

The authors develop a high-resolution model of coral larval dispersal for the southern Great Barrier Reef. They show that 2 °C of warming decreases larval dispersal distance and connectivity of reefs, hampering post-disturbance recovery and the potential spread of warm-adapted genes.

- Joana Figueiredo

- Christopher J. Thomas

- Emmanuel Hanert

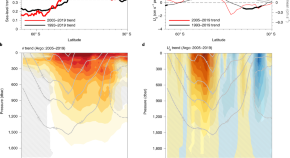

Phenological mismatches between above- and belowground plant responses to climate warming

The authors conduct a meta-analysis to reveal mismatches in above- and belowground plant phenological responses to warming that differ by plant type (herbaceous versus woody). The work highlights a need for further research and consideration of under-represented belowground phenological changes.

- Huiying Liu

- Madhav P. Thakur

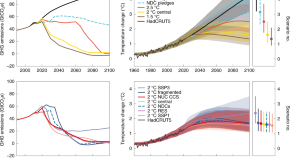

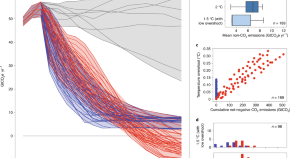

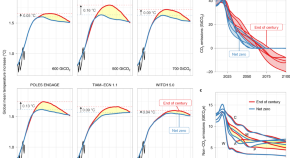

Near-term transition and longer-term physical climate risks of greenhouse gas emissions pathways

There is a balance in mitigation pathway design between economic transition cost and physical climate threats. This study provides a comprehensive framework to assess the near- and long-term risks under various warming scenarios globally and in particular regions.

- Ajay Gambhir

- Seth Monteith

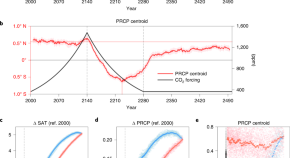

Hysteresis of the intertropical convergence zone to CO 2 forcing

In idealized model experiments where CO 2 increases four-fold before returning to its original level, temperature and precipitation show almost linear responses to CO 2 forcing. In contrast, the response of the Intertropical Convergence Zone lags behind CO 2 changes, associated with delayed energy exchanges.

- Jong-Seong Kug

- Jongsoo Shin

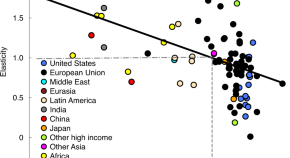

Contextualizing cross-national patterns in household climate change adaptation

The context and motivation around adaptation are influenced by local culture and institutions. In the United States, China, Indonesia and the Netherlands, some factors (such as perceived costs) have similar influences on household adaptation to flooding, but others (such as flood experience) differ between countries.

- Brayton Noll

- Tatiana Filatova