InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development

This brief is part of a series that summarizes essential scientific findings from Center publications.

Content in This Guide

Step 1: why is early childhood important.

- : Brain Hero

- : The Science of ECD (Video)

- You Are Here: The Science of ECD (Text)

Step 2: How Does Early Child Development Happen?

- : 3 Core Concepts in Early Development

- : 8 Things to Remember about Child Development

- : InBrief: The Science of Resilience

Step 3: What Can We Do to Support Child Development?

- : From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts

- : 3 Principles to Improve Outcomes

The science of early brain development can inform investments in early childhood. These basic concepts, established over decades of neuroscience and behavioral research, help illustrate why child development—particularly from birth to five years—is a foundation for a prosperous and sustainable society.

Brains are built over time, from the bottom up.

The basic architecture of the brain is constructed through an ongoing process that begins before birth and continues into adulthood. Early experiences affect the quality of that architecture by establishing either a sturdy or a fragile foundation for all of the learning, health and behavior that follow. In the first few years of life, more than 1 million new neural connections are formed every second . After this period of rapid proliferation, connections are reduced through a process called pruning, so that brain circuits become more efficient. Sensory pathways like those for basic vision and hearing are the first to develop, followed by early language skills and higher cognitive functions. Connections proliferate and prune in a prescribed order, with later, more complex brain circuits built upon earlier, simpler circuits.

The interactive influences of genes and experience shape the developing brain.

Scientists now know a major ingredient in this developmental process is the “ serve and return ” relationship between children and their parents and other caregivers in the family or community. Young children naturally reach out for interaction through babbling, facial expressions, and gestures, and adults respond with the same kind of vocalizing and gesturing back at them. In the absence of such responses—or if the responses are unreliable or inappropriate—the brain’s architecture does not form as expected, which can lead to disparities in learning and behavior.

The brain’s capacity for change decreases with age.

The brain is most flexible, or “plastic,” early in life to accommodate a wide range of environments and interactions, but as the maturing brain becomes more specialized to assume more complex functions, it is less capable of reorganizing and adapting to new or unexpected challenges. For example, by the first year, the parts of the brain that differentiate sound are becoming specialized to the language the baby has been exposed to; at the same time, the brain is already starting to lose the ability to recognize different sounds found in other languages. Although the “windows” for language learning and other skills remain open, these brain circuits become increasingly difficult to alter over time. Early plasticity means it’s easier and more effective to influence a baby’s developing brain architecture than to rewire parts of its circuitry in the adult years.

Cognitive, emotional, and social capacities are inextricably intertwined throughout the life course.

The brain is a highly interrelated organ, and its multiple functions operate in a richly coordinated fashion. Emotional well-being and social competence provide a strong foundation for emerging cognitive abilities, and together they are the bricks and mortar that comprise the foundation of human development. The emotional and physical health, social skills, and cognitive-linguistic capacities that emerge in the early years are all important prerequisites for success in school and later in the workplace and community.

Toxic stress damages developing brain architecture, which can lead to lifelong problems in learning, behavior, and physical and mental health.

Scientists now know that chronic, unrelenting stress in early childhood, caused by extreme poverty, repeated abuse, or severe maternal depression, for example, can be toxic to the developing brain. While positive stress (moderate, short-lived physiological responses to uncomfortable experiences) is an important and necessary aspect of healthy development, toxic stress is the strong, unrelieved activation of the body’s stress management system. In the absence of the buffering protection of adult support, toxic stress becomes built into the body by processes that shape the architecture of the developing brain.

Policy Implications

- The basic principles of neuroscience indicate that early preventive intervention will be more efficient and produce more favorable outcomes than remediation later in life.

- A balanced approach to emotional, social, cognitive, and language development will best prepare all children for success in school and later in the workplace and community.

- Supportive relationships and positive learning experiences begin at home but can also be provided through a range of services with proven effectiveness factors. Babies’ brains require stable, caring, interactive relationships with adults — any way or any place they can be provided will benefit healthy brain development.

- Science clearly demonstrates that, in situations where toxic stress is likely, intervening as early as possible is critical to achieving the best outcomes. For children experiencing toxic stress, specialized early interventions are needed to target the cause of the stress and protect the child from its consequences.

Suggested citation: Center on the Developing Child (2007). The Science of Early Childhood Development (InBrief). Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu .

Related Topics: toxic stress , brain architecture , serve and return

Explore related resources.

- Reports & Working Papers

- Tools & Guides

- Presentations

- Infographics

Videos : Serve & Return Interaction Shapes Brain Circuitry

Reports & Working Papers : From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts

Briefs : InBrief: The Science of Neglect

Videos : InBrief: The Science of Neglect

Reports & Working Papers : The Science of Neglect: The Persistent Absence of Responsive Care Disrupts the Developing Brain

Reports & Working Papers : Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships

Tools & Guides , Briefs : 5 Steps for Brain-Building Serve and Return

Briefs : 8 Things to Remember about Child Development

Partner Resources : Building Babies’ Brains Through Play: Mini Parenting Master Class

Podcasts : About The Brain Architects Podcast

Videos : FIND: Using Science to Coach Caregivers

Videos : How-to: 5 Steps for Brain-Building Serve and Return

Briefs : How to Support Children (and Yourself) During the COVID-19 Outbreak

Videos : InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : MOOC: The Best Start in Life: Early Childhood Development for Sustainable Development

Presentations : Parenting for Brain Development and Prosperity

Videos : Play in Early Childhood: The Role of Play in Any Setting

Videos : Child Development Core Story

Videos : Science X Design: Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children

Podcasts : The Brain Architects Podcast: COVID-19 Special Edition: Self-Care Isn’t Selfish

Podcasts : The Brain Architects Podcast: Serve and Return: Supporting the Foundation

Videos : Three Core Concepts in Early Development

Reports & Working Papers : Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : Training Module: “Talk With Me Baby”

Infographics : What Is COVID-19? And How Does It Relate to Child Development?

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : Vroom

Early Childhood Research

From language development to overall health, research consistently finds what happens in a child’s earliest years is most important for healthy development, growth and long-term well-being.

Notable Publications & Projects

Below are some of the most well-respected research studies on early childhood and early brain development, including some of Start Early’s own research and publications.

Longitudinal Research Studies

Read on and learn more about why quality early learning and care helps address the long-standing injustices in our communities and is a proven solution to breaking the cycle of generational poverty.

The Abecedarian Project

The Abecedarian Project demonstrated that young children who receive high-quality early education from infancy to age 5 do better in reading and math and are more likely to stay in school longer, graduate from high school, and attend a four-year college.

HighScope Perry Preschool

By age 40, adults who participated as 3- and 4-year-olds in quality preschool were more likely to have graduated from high school, held a job, made higher earnings, and committed fewer crimes than those who didn’t attend, according to this seminal study.

Early Head Start Research & Evaluation

Children enrolled in Early Head Start performed better on measures of cognition, social and emotional, and language functioning than their peers who were not enrolled, according to this landmark study of the federal Early Head Start program. The study also found that children who participated in Early Head Start (from birth to age 3) and later programs (from age 3 to 5) had the most positive outcomes.

Our Research Work

We conduct research and evaluations to elevate the expertise of early childhood professionals and support better learning environments.

Support Our Work

Together, when we start early, we can close the opportunity gap. With your support, we are getting closer to this reality every day.

What We Do

Our holistic approach ensures that we impact every aspect of early childhood development so children, families and educators can thrive.

Stay Connected

Sign up to receive news, helpful tools and learn about how you can help our youngest learners.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Caplan Foundation for Early Childhood

The Caplan Foundation for Early Childhood is an incubator of promising research and development projects that appear likely to improve the welfare of young children, from infancy through 7 years, in the United States. Welfare is broadly defined to include physical and mental health, safety, nutrition, education, play, familial support, acculturation, societal integration and childcare.

Grants are only made if a successful project outcome will likely be of significant interest to other professionals, within the grantee’s field of endeavor, and would have a direct benefit and potential national application. The Foundation’s goal is to provide seed money to implement those imaginative proposals that exhibit the greatest chance of improving the lives of young children, on a national scale . Because of the Foundation’s limited funding capability, it seeks to maximize a grant's potential impact.

Program Guidelines

The Foundation provides funding in the following areas

Early Childhood Welfare

Children can only reach their full potential when all aspects of their intellectual, emotional and physical development are optimally supported.

Providing a safe and nurturing environment is essential as is imparting the skills of social living in a culturally diverse world. Therefore, the Foundation supports projects that seek to perfect child rearing practices and to identify models that can provide creative, caring environments in which all young children thrive.

Early Childhood Education and Play

Research shows that children need to be stimulated as well as nurtured, early in life, if they are to succeed in school, work and life. That preparation relates to every aspect of a child’s development, from birth to age seven, and everywhere a child learns – at home, in childcare settings and in preschool.

We seek to improve the quality of both early childhood teaching and learning, through the development of innovative curricula and research based pedagogical standards, as well as the design of imaginative play materials and learning environments.

Parenting Education

To help parents create nurturing environments for their children, we support programs that teach parents about developmental psychology, cultural child rearing differences, pedagogy, issues of health, prenatal care and diet, as well as programs which provide both cognitive and emotional support to parents.

Funding Limitations

the foundation will not fund:.

- programs outside of the United States

- the operation or expansion of existing programs

- the purchase or renovation of capital equipment

- the staging of single events (e.g. concerts, seminars, etc.)

- the creation or acquisition of works of art or literature

- the activities of single individuals or for-profit entities

- political or religious organizations

- programs with religious content

- programs to benefit children residing in foreign countries

- medical research applicable to both adults and children

All letters of inquiry that don't comply with the limitations will be rejected.

Furthermore, the Foundation will only fund grant applications that define measurable outcomes, include credible methods for documenting and assessing results, provide for financial accountability in the application of funds, and include detailed, prudent implementation budgets.

Policy on Funding Indirect Expenses for Grants

The Foundation will not fund arbitrary or excessive allocations of indirect expenses even if a project is worthy. The Foundation’s Board will only approve a maximum of 15% of a project’s direct expenses, when earmarked as general and/or administrative overhead.

Policy Regarding Multiple Year Funding Requests

Consistent with the Foundation’s mission, as an incubator of innovative research and development directed to improving the general welfare of young children, we will not fund more than the first year of multiple year projects. It is our belief that having multiple funders, of those worthy projects that demand more sustained efforts, increases the likelihood of their success by ensuring broader oversight and greater long term promotional possibilities.

Apply for a Grant

The Foundation employs a two-step grant application process that includes the submission of both a Letter of Inquiry (LOI) and a Full Proposal–the latter only by those applicants requested to do so. This ensures that consideration of Full Proposals is limited to those applications that strictly comply with the Foundation’s programmatic guidelines.

The next deadline for submitting a LOI is .

Applicants must submit Letters of Inquiry by clicking on the Email your Letter of Inquiry button below. Once a Letter of Inquiry is received by the Foundation, the Directors will determine if the proposed program fits the Foundation’s funding guidelines. Successful applicants will be invited via email to submit Full Proposals.

Each Letter of Inquiry should include the following information:

- The organization’s official name, website address and contact information

- A brief (250 word maximum) summary of the organization’s mission and recent program history

- The organization’s 501(c)(3) Tax Exempt Status letter from the IRS and its’ Federal Tax ID#

- The total amount of the organization’s annual budget

- The total amount of the grant request

- An indication of the amount and type of support being requested from all sources

- Title of the project and a narrative description (1,000 words or less) of the issue(s) or need(s) to be addressed by the proposal, the work to be performed and the anticipated outcome

- A description of how the proposal fits the Foundation’s program guidelines

- A description of how your project and/or research is innovative in nature

- A contact person, their email address and phone number

Your Letter of Inquiry must follow the number format listed above. Failure to follow the specified format will disqualify your LOI from review by the Board of Directors. Please note LOI and the name of your organization in the subject line of your email.

There are many proposals that we do not consider because they do not meet the criteria stated in our website. We strive to fund ideas that are adventurous, thoughtful and challenge the status quo. They should have a fresh concept (not rehash an older idea) and a defined method of implementation that promotes new approaches and understanding of early childhood and pushes the boundaries of academic, social and cultural studies and practices.

All written correspondence to the Caplan Foundation for Early Childhood should be directed to Amanda R. Oechler, CPA at 108 East Main Street, Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, 17745

Email your Letter of Inquiry

This will open your default email client. If you are using a different client, please send the email to [email protected], and use "Letter of Inquiry" as your subject line.

Submit Your Application

Grants Awarded

{{ grant.organization }}, previous recipients.

- {{ grant.organization }} – {{ grant.amount }}

More about Previous Recipients

Frank and Theresa Caplan were pioneers in the development of creative, imaginative, educational toys for young children. In the early thirties, Frank Caplan was a youth worker and one of the first male nursery school teachers in the United States. In 1949, he co-founded Creative Playthings, a company that designed and manufactured toys to enhance the imagination and learning of young children.

By the 1950’s, Creative Playthings was one of the most important manufacturers and suppliers of early childhood educational toys and equipment. They collaborated with internationally known artists, such as Nino Vitali, to design toys, as well Milton Hebald, Isamu Noguchi, Robert Winston and architects like Louis Kahn to design outdoor playscapes and sculptures.

Creative Playthings researched and developed innovative curriculum materials for schools and furniture that could be stacked and rearranged to allow for flexibility within the classroom. They introduced dolls, which were racially diverse, and anatomically correct boy and girl dolls, which were provocative at the time.

In 1975, Frank Caplan and his wife, Theresa, created The Princeton Center for Infancy and Early Childhood, a pioneering research and publishing organization focusing on materials for parent education. He researched and co-authored, with Theresa, a national bestselling series on early childhood development called The First Twelve Months of Life (1977), The Second Twelve Months of Life (1978), and The Early Childhood Years: The 2-6 Year Old (1983). In addition, Frank and Theresa co-authored The Power of Play in 1973.

Throughout their lives, Frank and Theresa worked to develop innovative and beautifully designed educational toys and equipment for home and school environment. They wanted to encourage parents’ understanding and knowledge about the extraordinary time of infancy and early childhood.

The Caplan Foundation for Early Childhood was created in 2014 as a result of a bequest from Theresa Caplan stipulating her estate be used to incubate innovation and research addressing the needs of children from birth through age seven.

Financial Information

- 2015 IRS Form 990 (PDF)

- 2014 IRS Form 990 (PDF)

Submit your application.

Please send us the required documents as outlined on the website .

Investigating Educators’ and Students’ Perspectives on Virtual Reality Enhanced Teaching in Preschool

- Open access

- Published: 05 April 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sophia Rapti ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0003-4741-6572 1 ,

- Theodosios Sapounidis 1 &

- Sokratis Tselegkaridis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0825-0787 2

16 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

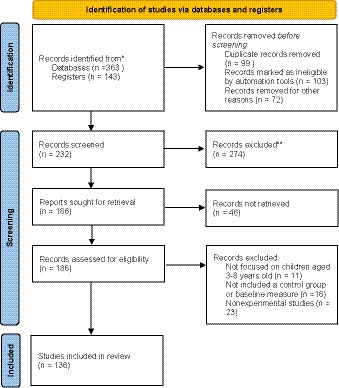

Recent developments in technology have introduced new tools, such as virtual reality, into the learning process. Although virtual reality appears to be a promising technology for education and has been adopted by a few schools worldwide, we still do not know students’ and educators’ opinions, preferences, and challenges with it, particularly in relation to preschool education. Therefore, this study: (a) analyzes the preferences of 175 children aged 3 to 6 years regarding traditional teaching compared to enhanced teaching with virtual reality and (b) captures educators’ perspectives on virtual reality technology. This evaluation of virtual reality took place in 12 Greek preschool classrooms. A combination of quantitative and qualitative methods were used for data collection. Specifically, regarding the qualitative data collection, the study included semi-structured interviews with the participating educators, oriented by 2 axes: (a) preschoolers’ motivation and engagement in virtual reality activities, and (b) virtual reality technology prospects and difficulties as an educational tool in a real class. Regarding the quantitative data collection, specially designed questionnaires were used. Bootstrapping was utilized with 1000 samples to strengthen the statistical analysis. The analysis of the students’ responses indicated a statistically significant difference in preference in favor of virtual reality enhanced teaching compared to a traditional method. Statistically significant differences were also observed regarding gender. Furthermore, based on the educators’ answers and comments, difficulties were encountered initially but eventually, virtual reality was regarded as an effective approach for educational purposes. However, concerns arose among educators as to whether this technology could adequately promote preschoolers’ cooperative skills.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent times, young learners have experienced an era marked by fast technological growth. Accordingly, children are exposed to various technological tools and electronic devices both in their everyday lives and in their school routines. Hence, there is a demand for innovative learning tools and practices (Kaimara et al., 2022 ).

Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) are regarded as updated teaching tools and are used more frequently in educational settings. Some researchers claim that students utilizing ICTs may perform better and more creatively than those students who are engaged in traditional learning activities (Nawaz et al., 2022 ). Moreover, the earlier ICTs and new technologies are used in education, the more aware young learners may become of them, and thus, may be able to exploit them effectively and wisely in their later lives (Li, 2021 ). Preschool educators may find it useful to integrate ICT tools and methods for teaching and learning, and in order to prepare effective future citizens.

According to some researchers’ claims, Virtual Reality (VR) is a form of these innovative tools and practices that has flourished as an interesting, “feasible” teaching aid in the learning process (Brown et al., 2020 ; Maas & Hughes, 2020 ). Specifically, VR can be integrated with mobile phones, personal computers (PCs), special glasses, and other types of gear into the teaching process. Therefore, with the aid of these types of technological devices, students can virtually “travel” from the depths of the Earth’s oceans to the peaks of Mars, allowing them to witness places, animals, and cultures firsthand that were previously unreachable through traditional teaching methods. Consequently, immersive learning activities characterized by realism are created through VR equipment (Shin, 2017 ). VR, based on conducted studies, is believed to have brought about several new learning opportunities in school routines, converting the school classroom into a natural, real, and meaningful environment for children’s learning experiences. During these experiences, learners have the potential to develop a range of skills and interact efficiently and effectively (Huang et al., 2016 ). Thus, VR may arise as a promising technology, suitable for educational settings from preschool to the university (Tilhou et al., 2020 ).

Notwithstanding, the majority of VR implementations can be found in fields like training simulation such as fighting and surgery (Burke et al., 2017 ; Oberhauser et al., 2018 ) instead of school classrooms. Thus, there has been a limited amount of researchs investigating the usage of VR technology in domains that are integrated into the education field (Chavez & Bayona, 2018 ). The implementation of VR seems not to have been examined thoroughly and sufficiently, although it may bring about several benefits to learners (Rienties et al., 2016 ). No matter how immersive a technological tool such as VR may be to offer “full multi-sensory interaction” , not many educators have integrated it into their activities in school classrooms (Radianti et al., 2020 ). In addition to this, some researchers claim that teachers cannot use VR effectively unless they are trained in it (Lorusso et al., 2020 ).

Additionally, VR may not be widely implemented in school classrooms for other reasons. Based on the existing literature, excessive exposure to VR may affect children negatively because it may create misconceptions of reality and may not promote critical thinking about the VR scenes and information (Hussein & Nätterdal, 2015 ; Li, 2021 ). Furthermore, there are concerns that children may lose a sense of their own creativity as they grow accustomed to more and more VR technology. Finally, there are concerns that preschoolers might adopt a sedentary lifestyle or experience motion sickness, vision loss, and headaches because of excessive exposure to VR screens (Hussein & Nätterdal, 2015 ). Consequently, the issue of time exposure to VR technology and whether this should be limited and under the constant presence of a teacher has arisen (Freina & Ott, 2015 ).

Moreover, educators are likely to face obstacles while attempting to implement VR in school classrooms, including the following: the shortage of modern technological gear, educators’ lack of knowledge and experience with VR technology, inadequate hardware/software knowledge, usability for VR technology, and the high cost of VR equipment (Kavanagh et al., 2017 ). Although new technologies may help to create effective learning environments for students, they are also often quite expensive and may be difficult to afford within school settings. Yet, the VR technology that is proposed in this current paper is reasonably priced; thus, many schools could provide it to their educators and students. Most often, in academic settings, VR is found to be utilized more frequently in higher education rather than in K-12 settings (Luo et al., 2021 ) and even less often in preschool classrooms.

Therefore, in this paper, we explore the potential impact of VR technology on young learners and specifically on preschoolers. In that way, education stakeholders would be able to clarify whether it may be helpful to design and implement VR activities from an early age.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides the theoretical background for virtual reality in educational settings, and Section 3 outlines the methodology employed to implement the intervention. The results are presented in Section 4 , with a detailed discussion following in Section. 5 . Section 6 describes the limitations encountered and Section 7 highlights the conclusions of the study.

Theoretical Background

In this section, we study the background of VR technology and its implementation in educational settings, with an emphasis on preschool classrooms. Studying these topics together contributes to a better understanding of VR’s impact on young learners. Moreover, this may enrich the existing professional literature and in turn, contribute to the effective preparation of preschoolers for their future lives.

VR Definition

VR is a form of simulated reality that may facilitate educators and students in the learning process. Yet, there has not been a widely accepted definition for VR yet. (Luo et al., 2021 ). Moreover, VR often fails to be distinguished from Augmented Reality (AR) which “overlays digital objects or virtual information onto the real world” (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2017 ). Most of the time, while referring to VR, a set-up of hardware and software utilizing technology comes to mind (Makransky & Petersen, 2019 ). According to related literature, there are 3 types of VR emerging from the degree the user interacts with the virtual environment: (a) immersive VR, (b) semi-immersive VR, and (c) non-immersive VR (Lorusso et al., 2020 ). In the first type, either devices such as Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) or special glasses are used. In the second type, desktop equipment or a TV screen is utilized to display the simulation (Merchant et al., 2014 ; Wu et al., 2020 ). In the third type, conventional computer equipment (screen, keyboard, mouse) is used (Robertson et al., 1993 ). Finally, the experience created by VR can evoke several senses like vision, hearing, and touching (Elmqaddem, 2019 ).

Development of VR in Educational Settings

VR is thought to enhance teaching and promote learners’ skills owing to its theoretical and practical framework. In detail, VR integrates disciplines of constructivist learning theory since it may help learners to obtain and construct knowledge with support from their teachers and peers, rather than being positioned as passive knowledge consumers. Therefore, during VR activities, students construct their knowledge based on their previous experiences facilitated by teachers (Rababah, 2021 ). Additionally, VR enables inquiry-based learning and could enhance children’s critical thinking of ideas, contributing to their cognitive development (Shin, 2017 ). In addition to this, based on the findings from other conducted studies, children seem to enhance their social skills through their participation in VR activities (Lorusso et al., 2020 ). VR could also improve teaching activities as it is used for integrating and scaffolding learning. Scaffolding focuses on what students cannot yet do by themselves but are able to do with the help of others, and aims to enable them to be able to accomplish this successfully alone (Van de Pol & Elbers, 2013 ). Moreover, with the technological growth characterizing our routine, scaffolding can be supported by computer tools (Belland, 2014 ). Such new technologies may support students’ learning by optimizing teaching practices and empowering the learning process through the use of multimedia gear (Shi et al., 2022 ). Thus, VR, by using technological tools and scaffolding, may contribute enhance traditional teaching methods through to the design of innovative school activities tailored to children’s needs.

During the last decade, VR has become increasingly popular due to its immersive traits and its ability to enrich the learning environment in school classrooms (Luo et al., 2021 ). Hence, many countries integrate VR technology into their educational settings to facilitate learning in various domains such as science, mathematics, and vocabulary development (Hu-Au & Lee, 2017 ; Villena-Taranilla et al., 2022 ). Notably, in European countries in general and in Greece specifically, there are official guidelines from the Ministry of Education for all kindergartens to integrate new technologies into the school curriculum. Teaching methods need to be developed and updated to put the students at the center of the learning process as active participants using modern technology. New technologies, such as VR and AR, among others may foster this (Rapti et al., 2023 ). Now, children can have easy access to technological tools and VR devices which seem to be appealing to them. This is especially true when the VR equipment is of low cost, such as in the case of this current study. Appropriate pricing allows schools to have easier access to this technology, making it possible to utilize iteffectively by both developed and developing countries.

According to Williams et al. ( 2018 ), VR technology has arisen in educational settings as a potential mainstream technology for a number of reasons:

It may empower educators’ teaching methods.

It may raise and keep students’ interests, thus evoking their curiosity.

It may wake up children’s imagination and contribute to the development of their creativity and other related skills.

It may form sensory-rich virtual learning environments, in which vision, sound-hearing, and touch can contribute to creating interesting learning experiences.

In these new learning experiences created by VR technology, there may be factors that need to be considered while designing and implementing activities in school classrooms in order to gain all the potential benefits for students: the age, the characteristics of students’ development, and the gender of participants. Empirical studies have indicated that in order to engage young learners in the learning process, effective school activities need to be tailored to their real needs and development (Bayar, 2014 ). Furthermore, the gender factor may influence students’ preference regarding new technologies such as VR. Technology preferences and differences between boys and girls are often attributed to gender-based stereotypes (Sullivan & Bers, 2013 ). Males seem to be more confident while dealing with computer equipment, due perhaps to their frequent exposure to video games (Sapounidis et al., 2019 ). Additionally, females are more likely than males to enrich their games with imagination through collaboration in small groups of peers, whilst males prefer to use more physical strength and work with larger teams (Volman et al., 2005 ).

VR and Preschool Education

Young learners need to develop a range of skills to succeed in life and in demanding workplaces as future citizens. Hence, educational settings should promote these skills and prepare students effectively for their well-being. What is more, it is vital to achieve this from an early age. Fortunately, educators can choose among a wide variety of tools and practices to select the most suitable ones for their students’ support in the learning process. One of these tools may be VR technology. Findings from emerging research indicates that, preschoolers can enhance many skills through VR activities. These skills include: motor, linguistic, mathematical, social, and scientific ones (Ren & Wu, 2019 ; Zhu et al., 2020 ; Pan et al., 2021 ). Young learners seem to experiment with VR technology and gear with curiosity, which generates a sense of enthusiasm (Lorusso et al., 2020 ). These activities also contribute to their cognitive development too (Li, 2021 ). Additionally, VR technology seems to enhance children’s social skills. Social learning is rooted in children’s family environments. When young learners enter preschool, they immediately enter a larger social group in which they are supported to develop their social competencies with peers and teachers. VR activities may facilitate children’s social experiences and motivate them to form positive behaviors rather than negative ones (Shoshani, 2023 ).

However, so far, few studies have explored young learners’ preferences between VR technology and traditional methods. Thus, it remains unclear what students prefer most and regard as appealing game-playing activities in preschool classrooms. Furthermore, there haven’t been enough studies investigating preschool educators’ perspectives on VR and its potential impact on their school reality. So, in order to contribute to the theory related to VR and its implementations, our study aims to fill the gaps in existing literature, by addressing the following Research Questions (RQ):

RQ1. What do preschoolers prefer most between VR activities and traditional ones? RQ2. What are the educators’ perspectives on VR technology in preschool? RQ3. Is gender a factor affecting preschoolers’ preference for VR technology?

Methodology

Participants.

Children were randomly selected to participate in this activity enriched by VR technology. Thirteen educators from 12 areas of Northern Greece implemented the intervention. In addition to this, a total of 175 children from 12 public Greek kindergartens, including 83 girls and 92 boys, all 3 to 6 years of age, took part in the VR applications. The educators participated in a 3-hour training program regarding the utilization of VR in the school classroom, prior to the children’s participation.

Research Design and Procedure

The researchers designed two different learning activities for one group of participants. The same class of kindergarteners was examined during and after a traditional teaching activity and during and after one activity enriched by VR technology. All the children, with the help of their educators, first participated in a traditional teaching activity about the animals of the Antarctic and the dinosaurs. The same children then “traveled” to the Antarctic and “met” dinosaurs using VR headsets, smartphones, and VR videos, as shown in Fig. 1 . To facilitate that, a VRbox (V2) which is a low-cost VR headset is utilized. This is a type of VR technology that can use a smartphone’s screen to place the user inside a 3D world. Thus, this is a reasonably-priced VR tool that can be an asset to help schools with very low financial budgets to have access to innovative VR experiences and related educational approaches.

VR activities with preschoolers utilizing VR technology

When the activities were completed, the children were asked to indicate their preference between traditional activities and VR activities. Two questionnaires were employed to collect data; self-reported measures/questionnaires with one question for each item. First, the “This or That” questionnaire (Sim & Horton, 2012 ) was used, where the children were asked to choose between the two activities and indicate (a) their favorite one, (b) the activity they would like to do again, and (c) the one they found more enjoyable as a game.

Additionally, the “Smilyometer” (Read, 2008 ) was employed using a 5-point Likert scale, which is treated as interval scale (e.g., Sapounidis et al., 2019 ). Children were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement to the following statements: (a) I liked the traditional activity, (b) I liked the VR activity, (c) I would like to do the traditional activity again, (d) I would like to do the VR activity again, (e) I thought the traditional activity gave me fun as a game, and (f) I thought the VR activity gave me fun as a game.

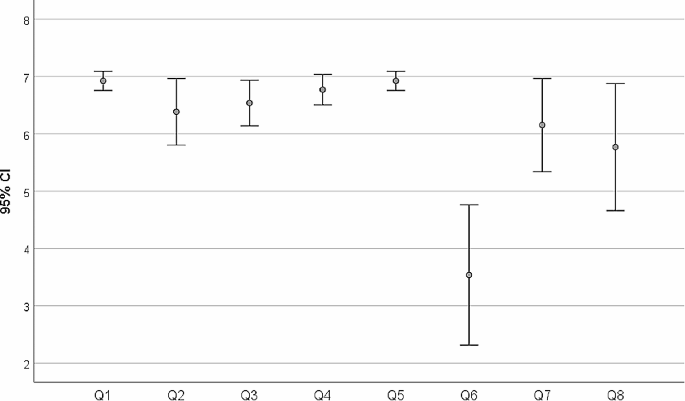

In addition, educators were asked to provide their perspectives regarding VR experience using a 7-point Likert scale questionnaire. Specifically, the questionnaire consisted of 8 Questions (Q):

Q1. Children did not find the VR activities boring. Q2. Children demonstrated a higher attention span during VR activities compared to traditional activities. Q3. VR activities motivated children, who are used to showing little interest in activities, to participate more. Q4. I am interested in integrating more VR activities into my lessons. Q5. I believe that VR activities of this kind could be utilized for educational purposes. Q6. I believe that VR activities could foster cooperation among students. Q7. The implementation of VR activities was easy to do in a school classroom. Q8. VR activities can be utilized as forms of playing and facilitating learning in a school classroom.

Finally, to capture the educators’ perspectives on the usage of VR technology, semi-structured interviews were designed (Kallio et al., 2016 ), oriented by 3 axes: (a) preschoolers’ motivation and engagement in VR activities, and (b) VR technology prospects and difficulties as an educational tool in a real class.

Data Analysis

To conduct a statistical analysis of the data, the questionnaire responses were quantified. Specifically, regarding the “This or That” questionnaire, the response in favor of traditional activities was assigned a score of 1, while the response in favor of VR activities was assigned a score of 2.

Related to the “Smilyometer”, the scoring system used was as follows: (a) Strongly Disagree was assigned a score of 1, (b) Disagree was assigned a score of 2, (c) Neutral was assigned a score of 3, (d) Agree was assigned a score of 4, and (e) Strongly Agree was assigned a score of 5.

To strengthen the statistical analysis, bootstrapping methods were utilized, with 1000 samples. The bootstrapping approach assumes no underlying distribution of the data, as it treats even the non-normal data as normal, drawing random subsamples from the originally collected samples (Cheung et al., 2023 ). A paired-sample t-test was employed to compare the responses of students regarding traditional activities and VR activities. Additionally, an independent-sample t-test was utilized to analyze the data based on student gender. In general, multiple t-tests might result in increasing type I errors, however, in our case, we test two conditions at a time (boys/girls, or traditional teaching/VR teaching), so the type I error does not exceed 5% (Field, 2005 ).

Finally, related to the educators’ questionnaire, the scoring system used was as follows: (a) Strongly Disagree was assigned a score of 1, (b) Disagree was assigned a score of 2, (c) Somewhat Disagree was assigned a score of 3, (d) Neutral was assigned a score of 4, (e) Somewhat Agree was assigned a score of 5, (f) Agree was assigned a score of 6, and (g) Strongly Agree was assigned a score of 7.

The students’ preference for VR activities is indicated through (a) the results of the “This or That” questionnaire (shown in Table 1 ), and (b) the results of the “Smilyometer” questionnaire (shown in Table 2 ).

According to Table 1 , there were statistically significant ( p < 0.05) and strong ( r > 0.7) associations between children’s responses and learning activity.

The reliability of Smilyometer questions for the traditional activity was found to be acceptable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.73 and inter-item correlations of 0.4. Also, the reliability of Smilyometer questions for the VR activity was found to be acceptable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.688 and inter-item correlations of 0.5. These alpha values are considered acceptable given the small number of items (Herman, 2015 ; Pallant, 2020 ).

To assess potential statistically significant differences between students’ preferences for the traditional activity and the VR activity, a paired-sample t-test was performed. The results, presented in Table 3 , favored VR activities in each case.

Regarding the analysis by gender of the students, Table 4 displays the means of the responses along with the corresponding standard deviations and standard error mean.

To assess any statistically significant differences between boys’ and girls’ preferences for the traditional activity and the VR activity, independent-sample t-test was performed. The results, are presented in Table 5 .

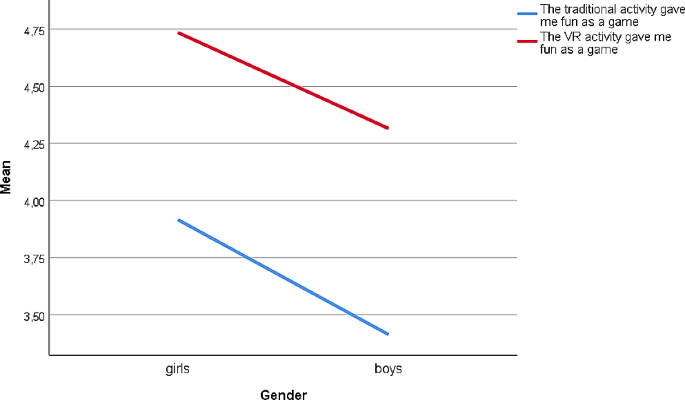

Based on the results of the independent-samples t-test, statistically significant differences were observed in two questions. Figure 2 displays the mean scores for both girls and boys in these questions.

Statistically significant differences between girls and boys

Table 6 presents the mean scores derived from the educators’ responses to the questionnaire administered to them.

The educators’ responses depicted a belief that VR activities can be utilized for educational purposes (Q5). Additionally. the children get engaged in VR activities without getting bored (Q1). However, the has been a low score regarding the question of whether such activities fostered students’ cooperation (Q6).

Figure 3 shows the mean values for the eight questions, accompanied by 95% confidence interval (CI) bars.

Mean values with 95% CI

Regarding the semi-structured interviews, and preschoolers’ motivation and engagement, all the educators agree that the VR activity excited the children, who “ asked, again and again, to put on the VR headset, to live the experience ” while “ waiting for their turn to put on the VR headset ”. However, the educators noted that this posed challenges as the children had to endure long waiting time for their turns to participate. It was suggested by the educators that having had multiple VR headsets available would have been beneficial, allowing more children to engage in activities simultaneously.

In addition, “ some children were afraid to wear the VR headset at first until they got used to them ”, while some other children “ reported fear due to instability in moving around the room ”. This highlights the importance of being exposed to such technologies adequately enough before using them in an activity orientated by certain rules.

Regarding VR technology as a potentially effective educational tool, when the children were asked to describe what they saw during the VR activities, it was noted that “ they readily used descriptive language to express their experiences. In contrast, during other activities, some children were observed to be more reserved and less likely to speak or provide detailed descriptions ”. Therefore, although the VR activity was implemented on an individual basis, it effectively captured the children’s interest and made the lesson experiential. However, it was noted that developing cooperation among the children proved to be challenging within this activity.

Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that the children expressed a strong desire for more opportunities to engage in VR experiences in the future. The preschoolers remembered details from their virtual “journeys” and wanted to share their experience with their peers even after a month had passed.

Lastly, aside from the preschoolers’ enthusiasm about VR technology, we also witnessed their educators’ enthusiasm as well: “ I believe that virtual reality is a valuable tool that can be effectively utilized for teaching purposes”, “It was truly enjoyable and impressive to witness my students learning and having fun simultaneously”, “They actively engaged with one another, discussing their experiences and expressing their enthusiasm strongly ”.

This current paper aims to capture students’ and educators’ perspectives on VR technology in preschool. Regarding our first RQ and what preschoolers tend to prefer most between VR activities and traditional ones, all the preschoolers showed great interest in VR activities. They were extremely curious and wanted to explore the learning environment and the 3D world which was created by VR equipment. They were focused on the activity from the very beginning to the end of it. These findings emerge from both educators’ feedback and the students’ responses to our questionnaire after the VR intervention. It seems that when a teaching activity in the school curriculum is attractive, it raises and keeps students’ attention and interest throughout its implementation (Chen, 2016 ).

In addition to this, the preschoolers seemed to enjoy the VR activities very much due to their visual, auditory, and kinesthetic characteristics. In VR activities, children are motivated to use their hands, arms, and legs. This is something that preschoolers enjoy doing. On top of that, this VR trait contributes to children’s development of coordination and motor skills (Wang et al., 2022 ). Moreover, children were supported through the usage of VR instruments to improve their navigation and orientation ability (Lorusso et al., 2020 ). So, while having a VR learning activity tailored to preschoolers’ age and development, a range of skills promotion may be achieved too.

Related to our second RQ and the educators’ perspectives on VR technology implemented in preschool, all the educators agreed that this may be an effective tool to utilize in school classrooms with potential benefits for young learners. To start with, all the educators commented on VR activities as a means of creating a unique enhanced teaching experience for preschoolers. Young learners seem to live a learning experience in which knowledge is built by broadening their imagination and mind allowing them to access visually everything they wish as if they were there in real (Schmitz et al., 2020 ). In such a frame, students not only can learn innovatively but they can perform the tasks better and more holistically based on some researchers’ claims (Radianti et al., 2020 ).

In addition to this, preschoolers’ attention span and enjoyment emerging from VR activities were high throughout the intervention according to educators’ comments in their interviews. This may be attributed to the fact that VR applications in preschool classrooms assist children in learning various subjects while having fun (Zhai, 2021 ). This finding aligns with the results of our study, which demonstrated statistically significant differences in children’s preferences for VR activities compared to traditional ones. The experiences offered by VR technology contributed to the children’s strong preference for VR activities. Furthermore, educators noticed that children were able to remember easily and reflect upon concepts via VR technology. It seems that VR’s characteristic of having powerful visualization and fewer symbols to interpret while trying to understand something may facilitate young learners’ direct understanding of topics with less cognitive effort (Elmqaddem, 2019 ). Consequently, this could contribute to their better comprehension of many issues (Li, 2021 ).

In terms of our third RQ and whether gender has the potential to affect the VR impact on preschoolers, the findings from this study indicate that there may be a gender difference in the experience of VR activities. We found that during our VR intervention, girls showed greater interest than boys in the VR activities compared to traditional ones and gained more pleasure out of it. That may have happened because of the females being emotionally involved with the information in the VR environment (Mousas et al., 2018 ). Some research indicates that females may be more prone to become «embodied ” with visualized information and understand it better than males (De Almeida Scheibler & Rodrigues, 2018 ). Moreover, the female participants seemed to enjoy and participate equally in all the VR scenarios in the implemented activities. This may be explained by the fact that female participants liked the topics of our VR activities. It seems that the context of a VR activity may affect the level of interest that each gender may show. For instance, military scenarios may appeal most to males (Grassini & Laumann, 2020 ).

Finally, regarding children’s social skills and their promotion through VR technology, according to existing literature, VR technology may create a range of emotional situations in which children can enhance their social skills. VR technology turns out to be able to represent authentic social scenarios and cases in which children act as if they are in their everyday lives (Georgescu et al., 2014 ). The more children become familiar with VR technology, the more they participate in groups to work and cooperate as team members (Luo et al., 2021 ). However, based on the educators’ perspectives in our intervention, limitations were identified in promoting student collaboration. Furthermore, our findings revealed two different cases: on the one hand, the children were so enthusiastic to experience the VR environment that they didn’t care to share this with their peers. On the other hand, they were so engaged in the VR activity that they showed great interest in discussing their ideas and feelings with their friends many days after the intervention. Thus, while there was enthusiasm and detailed discussions among the students about their individual experiences, there was a lack of a common group goal, teamwork, and collaborative activity. Hence, the educators observed that although the VR activities generated excitement and full engagement, they did not necessarily foster a sense of teamwork among the students. According to some researchers’ findings, VR might enable children to feel that they belong to a special learning group and environment to explore and discover knowledge meaningful to them. Yet, this often makes them want to share this experience and cooperate more with the visualized heroes rather than their peers (Bailey & Bailenson, 2017 ). Therefore, VR appears to be a technology potential to promote communication among students but needs to be further researched as far as the collaboration domain is concerned.

Limitations

Children were randomly selected to participate in this activity enriched by VR technology. However, one of the limitations of this study could be that all the data was collected from kindergartens located in Northern Greece to which we had easy access. Additionally, because of educators’ limited prior experience with VR technology, we decided to provide them with a 3-hour training program. During this program, they were able to familiarize themselves with the equipment and actively participate in various VR activities before implementing the intervention with the students. Yet, this may have affected the way they utilized VR technology and the way they expressed their perspectives on it. Additionally, it was the first time the children had been exposed to such activities, which may have led them to their enthusiastic preference for VR activities.

Conclusions

In this paper, a preschool education intervention was conducted involving 13 educators and 175 students. The study aimed to explore the preferences and perspectives of both teachers and learners by comparing traditional teaching methods with VR enhanced teaching. Statistical analysis, specifically t-tests, were employed to examine whether there were statistically significant differences between the two approaches, and the results indicated a significant preference for VR activities. Also, gender differences were observed to be statistically significant. Thus, it is recommended that further research investigating VR’s impact on preschoolers focusing on the gender factor be conducted. Moreover, according to the findings, educators expressed the belief that teaching may be enhanced by VR technology. The educators’ interviews highlighted the enthusiasm of children to experience VR learning and get engaged in it with much curiosity and interest. However, the interviews also revealed limited development of cooperation among students. Finally, this current paper suggests utilizing VR technology in preschool to enhance traditional teaching methods as long as implemented activities meet the young learners’ 21st -century needs.

Data Availability

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Akçayır, M., & Akçayır, G. (2017). Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature. Educational Research Review , 20 , 1–11.

Article Google Scholar

Bailey, J. O., & Bailenson, J. N. (2017). Immersive virtual reality and the developing child. Cognitive development in digital contexts (pp. 181–200). Academic.

Bayar, A. (2014). The components of effective Professional Development activities in terms of teachers’ perspective. Online Submission , 6 (2), 319–327.

Google Scholar

Belland, B. R. (2014). Scaffolding: Definition, current debates, and future directions. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 505–518).

Brown, M., McCormack, M., Reeves, J., Brooks, C., & Grajek, S. (2020). EDUCAUSE Horizon Report. Teaching and Learning Edition. EDUCAUSE Horizon Report Review , 55 (1).

Burke, E., Felle, P., Crowley, C., Jones, J., Mangina, E., & Campbell, A. G. (2017). Augmented reality EVAR training in mixed reality educational space. In 2017 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) 1571–1579.

Chavez, B., & Bayona, S. (2018). Virtual reality in the learning process. Trends and Advances in Information Systems and Technologies , 2 (6), 1345–1356.

Chen, Y. L. (2016). The effects of virtual reality learning environment on student cognitive and linguistic development. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher , 25 , 637–646.

Cheung, S. F., Pesigan, I. J. A., & Vong, W. N. (2023). DIY bootstrapping: Getting the nonparametric bootstrap confidence interval in SPSS for any statistics or function of statistics (when this bootstrapping is appropriate). Behavior Research Methods , 55 (2), 474–490. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01808-5 .

De Almeida Scheibler, C., & Rodrigues, M. A. F. (2018). User experience in games with HMD glasses through first and third-person viewpoints with emphasis on embodiment. Proceedings – 2018 20th Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality, SVR 2018 . https://doi.org/10.1109/SVR.2018.00022 .

Elmqaddem, N. (2019). Augmented reality and virtual reality in Education. Myth or reality? International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning , 14 (3). https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v14i03.9289 .

Field, A. (2005). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS Third Edition. In SAGE (Vol. 2nd, Issue Third Edition).

Freina, L., & Ott, M. (2015). A literature review on immersive virtual reality in education: state of the art and perspectives. The International Scientific Conference eLearning and Software for Education , 10–1007.

Georgescu, A. L., Kuzmanovic, B., Roth, D., Bente, G., & Vogeley, K. (2014). The use of virtual characters to assess and train non-verbal communication in high-functioning autism. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience , 8 , 807.

Grassini, S., & Laumann, K. (2020). Are modern head-mounted displays Sexist? A systematic review on gender differences in HMD-Mediated virtual reality. Frontiers in Psychology , 11 , https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01604 .

Herman, B. C. (2015). The influence of global warming science views and sociocultural factors on willingness to mitigate global warming. Science Education , 99 (1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21136 .

Hu-Au, E., & Lee, J. J. (2017). Virtual reality in education: A tool for learning in the experience age. International Journal of Innovation in Education , 4 (4), 215–226.

Huang, H. M., Liaw, S. S., & Lai, C. M. (2016). Exploring learner acceptance of the use of virtual reality in medical education: A case study of desktop and projection-based display systems. Interactive Learning Environments , 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2013.817436 .

Hussein, M., & Nätterdal, C. (2015). The benefits of virtual reality in Education the benefits of using virtual reality in Education A Comparison Study the benefits of virtual reality in education: A comparison study . University of Gothenburg,

Kaimara, P., Oikonomou, A., & Deliyannis, I. (2022). Could virtual reality applications pose real risks to children and adolescents? A systematic review of ethical issues and concerns. Virtual Reality , 26 (2), 697–735.

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., & Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing (Vol , 72 , 2954–2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031 . Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Kavanagh, S., Luxton-Reilly, A., Wuensche, B., & Plimmer, B. (2017). A systematic review of virtual reality in education. Themes in Science and Technology Education , 10 (2), 85–119.

Li, J. (2021). Research on the reform and innovation of preschool education informatization under the background of wireless communication and virtual reality. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing , 2021 , 1–6.

Lorusso, M. L., Giorgetti, T. S., Negrini, M., Reni, P., G., & Biffi, E. (2020). Semi-immersive virtual reality as a tool to improve cognitive and social abilities in preschool children. Applied Sciences , 10 (8), 2948.

Luo, H., Li, G., Feng, Q., Yang, Y., & Zuo, M. (2021). Virtual reality in K-12 and higher education: A systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2019. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning , 37 (3), 887–901.

Maas, M. J., & Hughes, J. M. (2020). Virtual, augmented and mixed reality in K–12 education: A review of the literature. Technology Pedagogy and Education , 29 (2), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1737210 .

Makransky, G., & Petersen, G. B. (2019). Investigating the process of learning with desktop virtual reality: A structural equation modeling approach. Computers & Education , 134 , 15–30.

Merchant, Z., Goetz, E. T., Cifuentes, L., Keeney-Kennicutt, W., & Davis, T. J. (2014). Effectiveness of virtual reality-based instruction on students’ learning outcomes in K-12 and higher education: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education , 70 , 29–40.

Mousas, C., Anastasiou, D., & Spantidi, O. (2018). The effects of appearance and motion of virtual characters on emotional reactivity. Computers in Human Behavior , 86 , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.036 .

Nawaz, S., Biasutti, M., Górecki, J., & Zang, J. (2022). New evidence on technological acceptance model in preschool education: Linking project-based learning (PBL), mental health, and semi-immersive virtual reality with learning performance .

Oberhauser, M., Dreyer, D., Braunstingl, R., & Koglbauer, I. (2018). What’s real about virtual reality flight simulation? Aviation Psychology and Applied Human Factors . https://doi.org/10.1027/2192-0923/a000134 .

Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual: A step-by-step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. Open University Press.

Pan, Z., López, M., Li, C., & Liu, M. (2021). Introducing augmented reality in early childhood literacy learning. Research in Learning Technology , 29 .

Rababah, E. Q. (2021). From theory to practice: Constructivist learning practices among Jordanian kindergarten teachers. Kıbrıslı Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi , 16 (2), 612–626.

Radianti, J., Majchrzak, T. A., Fromm, J., & Wohlgenannt, I. (2020). A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Computers & Education , 147 .

Rapti, S., Sapounidis, T., & Tselegkaridis, S. (2023). Enriching a traditional learning activity in preschool through augmented reality: Children’s and teachers’ views. Information , 14 (10), 530.

Read, J. C. (2008). Validating the Fun Toolkit: An instrument for measuring children’s opinions of technology. Cognition Technology and Work , 10 (2), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10111-007-0069-9 .

Ren, Z., & Wu, J. (2019). The effect of virtual reality games on the gross motor skills of children with cerebral palsy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 16 (20), 3885.

Rienties, B., Giesbers, B., Lygo-Baker, S., Ma, H. W. S., & Rees, R. (2016). Why some teachers easily learn to use a new virtual learning environment: A technology acceptance perspective. Interactive Learning Environments , 24 (3), 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.881394 .

Robertson, G. G., Card, S. K., & Mackinlay, J. D. (1993). Three views of virtual reality: Nonimmersive virtual reality. Computer , 26 (2), 81.

Sapounidis, T., Demetriadis, S., Papadopoulos, P. M., & Stamovlasis, D. (2019). Tangible and graphical programming with experienced children: A mixed methods analysis. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction , 19 , 67–78.

Schmitz, A., Joiner, R., & Golds, P. (2020). Is seeing believing? The effects of virtual reality on young children’s understanding of possibility and impossibility. Journal of Children and Media , 14 (2), 158–172.

Shi, A., Wang, Y., & Ding, N. (2022). The effect of the game–based immersive virtual reality learning environment on learning outcomes: Designing an intrinsic integrated educational game for pre–class learning. Interactive Learning Environments , 30 (4), 721–734.

Shin, D. H. (2017). The role of affordance in the experience of virtual reality learning: Technological and affective affordances in virtual reality. In Telematics and Informatics (Vol. 34, Issue 8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.05.013 .

Shoshani, A. (2023). From virtual to prosocial reality: The effects of prosocial virtual reality games on preschool children’s prosocial tendencies in real-life environments. Computers in Human Behavior , 139 .

Sim, G., & Horton, M. (2012). Investigating children’s opinions of games: Fun toolkit vs. this or that. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series , 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1145/2307096.2307105 .

Sullivan, A., & Bers, M. U. (2013). Gender differences in kindergarteners’ robotics and programming achievement. International Journal of Technology and Design Education , 23 (3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-012-9210-z .

Tilhou, R., Taylor, V., & Crompton, H. (2020). 3D Virtual Reality in K-12 Education: A Thematic Systematic Review . https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0618-5_10 .

Van de Pol, J., & Elbers, E. (2013). Scaffolding student learning: A micro-analysis of teacher–student interaction. Learning Culture and Social Interaction , 2 (1), 32–41.

Villena-Taranilla, R., Tirado-Olivares, S., Cózar-Gutiérrez, R., & González-Calero, J. A. (2022). Effects of virtual reality on learning outcomes in K-6 education: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review , 35 , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100434 .

Volman, M., Van Eck, E., Heemskerk, I., & Kuiper, E. (2005). New technologies, new differences. Gender and ethnic differences in pupils’ use of ICT in primary and secondary education. Computers and Education , 45 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2004.03.001 .

Wang, N., Abdul RahmanM, N., & Lim, B. H. (2022). Teaching and curriculum of the preschool physical education major direction in colleges and universities under virtual reality technology. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience .

Williams, J., Jones, D., & Walker, R. (2018). Consideration of using virtual reality for teaching neonatal resuscitation to midwifery students. Nurse Education in Practice , 31 , 126–129.

Wu, B., Yu, X., & Gu, X. (2020). Effectiveness of immersive virtual reality using head-mounted displays on learning performance: A meta‐analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology , 51 (6), 1991–2005.

Zhai, H. (2021). The application of VR technology in preschool education professional teaching. In 2021 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Education (ICAIE) , 319–323.

Zhu, M., Sun, Z., Zhang, Z., Shi, Q., He, T., Liu, H., & Lee, C. (2020). Haptic-feedback smart glove as a creative human-machine interface (HMI) for virtual/augmented reality applications. Science Advances , 6 (19).

Download references

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. No funding was received for conducting this study.

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Philosophy and Education, Department of education, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH), Thessaloniki, 54124, Greece

Sophia Rapti & Theodosios Sapounidis

Department of Information and Electronic Engineering, International Hellenic University (IHU), Sindos, 57400, Greece

Sokratis Tselegkaridis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Theodosios Sapounidis .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respects to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the current study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (number 56/24-2-2022, 46009/2022). Additionally, informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study (informed consent from the parents regarding the children-participants under 16 and verbal informed consent from the educators-participants were obtained prior to the intervention).

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Rapti, S., Sapounidis, T. & Tselegkaridis, S. Investigating Educators’ and Students’ Perspectives on Virtual Reality Enhanced Teaching in Preschool. Early Childhood Educ J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-024-01659-z

Download citation

Accepted : 09 March 2024

Published : 05 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-024-01659-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Virtual reality technology

- Preschool education

- Mixed method

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

How to Do Action Research in Your Classroom

You are here

This article is available as a pdf. please see the link on the right..

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Game-based learning in early childhood education: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Department of Kindergarten, College of Education, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

Game-based learning has gained popularity in recent years as a tool for enhancing learning outcomes in children. This approach uses games to teach various subjects and skills, promoting engagement, motivation, and fun. In early childhood education, game-based learning has the potential to promote cognitive, social, and emotional development. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to summarize the existing literature on the effectiveness of game-based learning in early childhood education This systematic review and meta-analysis examine the effectiveness of game-based learning in early childhood education. The results show that game-based learning has a moderate to large effect on cognitive, social, emotional, motivation, and engagement outcomes. The findings suggest that game-based learning can be a promising tool for early childhood educators to promote children’s learning and development. However, further research is needed to address the remaining gaps in the literature. The study’s findings have implications for educators, policymakers, and game developers who aim to promote positive child development and enhance learning outcomes in early childhood education.

1 Introduction

Game-based learning in early childhood education has evolved over time, driven by advancements in technology, educational research, and changing pedagogical approaches. Digital game-based learning refers to the use of digital technology, such as computers or mobile devices, to deliver educational content through interactive games ( Behnamnia et al., 2020 ). Game-based learning, on the other hand, is a broader term that encompasses both digital and non-digital games as tools for educational purposes. In the early years, educational games were primarily non-digital, consisting of board games, puzzles, and manipulatives designed to teach basic concepts and skills ( Pivec, 2007 ). These games often focused on early literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving. With the advent of computers and educational software, digital games emerged as a new medium for learning in the late 20th century. Early educational computer games, such as “Reader Rabbit” and “Math Blaster,” aimed to engage young learners through interactive gameplay while reinforcing educational content. As technology continued to advance, game-based learning expanded beyond standalone software to web-based platforms, mobile apps, and immersive virtual environments ( Shamir et al., 2019 ). The introduction of touchscreen devices, such as tablets and smartphones, made educational games more accessible and interactive for young children. These advancements allowed for greater customization, adaptive learning experiences, and real-time feedback, tailoring the games to meet the individual needs and abilities of young learners.

Researchers and educators recognized the potential of game-based learning to enhance engagement, motivation, and learning outcomes in early childhood education. Studies began to explore the cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral effects of game-based learning, highlighting its effectiveness in promoting critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, creativity, and digital literacy skills ( Park and Park, 2021 ).

In early childhood education, online educational game-based learning has gained popularity as a tool to promote cognitive, social, and emotional development in young children ( Anastasiadis et al., 2018 ). Online educational games are interactive digital games specifically designed to educate and teach children a wide range of skills and concepts. These games utilize engaging and interactive elements to promote learning in areas such as literacy, numeracy, problem-solving, and critical thinking ( Papanastasiou et al., 2022 ). These games are typically played on digital devices such as computers, tablets, and smartphones, and they offer a variety of engaging and interactive learning experiences for young children. Young children are naturally curious and have a strong desire to explore and learn about their environment ( Gurholt and Sanderud, 2016 ). Online educational game-based learning taps into this natural curiosity and provides children with opportunities to engage in meaningful and engaging learning experiences. These games can be tailored to meet the unique needs and abilities of young children, and they can be adapted to suit different learning styles and preferences ( Qian and Clark, 2016 ).

One of the key benefits of online educational game-based learning in early childhood education is its ability to promote cognitive development ( Ferreira et al., 2016 ). Online games can help children develop their problem-solving skills, memory, attention, and processing speed. For example, puzzle games can help children develop their spatial reasoning and problem-solving skills, while memory games can help them improve their memory and concentration ( Suhana, 2017 ).

In addition to promoting cognitive development, online educational game-based learning can also enhance social development in young children. Online games provide children with opportunities to interact with their peers and develop important social skills such as cooperation, communication, and empathy. Children can learn to work together, take turns, and share resources, which are essential skills for building positive relationships and succeeding in life ( Lamrani and Abdelwahed, 2020 ).

Moreover, online educational game-based learning can promote emotional development in young children ( Peterson et al., 2016 ). Online games can help children develop their emotional regulation skills, self-awareness, and self-confidence ( Simion and Bănuț, 2020 ). Games that involve role-playing can help children develop their emotional intelligence and understand different perspectives, while games that require children to take risks and try new things can help them build resilience and confidence ( Huynh et al., 2020 ).

This distinction is further exemplified in studies using online educational game-based learning in early childhood education for is its ability to increase children’s motivation and engagement in learning ( Hwa, 2018 ). Traditional teaching methods can sometimes be dry and one-dimensional, leading to disengagement and boredom in children ( Fotaris et al., 2016 ). Online educational games, on the other hand, provide a fun and interactive way to learn, which can increase children’s motivation and engagement in learning ( Nieto-Escamez and Roldán-Tapia, 2021 ). Children are more likely to be engaged in learning when they are having fun and enjoying the process ( Iten and Petko, 2016 ). Furthermore, online educational game-based learning can be tailored to meet the individual needs and abilities of young children ( Ke, 2014 ). Online games can be adapted to suit different learning styles and preferences, ensuring that all children can benefit from this approach to learning. This is certainly true in the case of games that involve movement and physical activity can be used to promote learning in children who have a kinesthetic learning style, while games that involve visual aids can be used to promote learning in children who have a visual learning style ( Hayati et al., 2017 ).