Popular searches

- How to Get Participants For Your Study

- How to Do Segmentation?

- Conjoint Preference Share Simulator

- MaxDiff Analysis

- Likert Scales

- Reliability & Validity

Request consultation

Do you need support in running a pricing or product study? We can help you with agile consumer research and conjoint analysis.

Looking for an online survey platform?

Conjointly offers a great survey tool with multiple question types, randomisation blocks, and multilingual support. The Basic tier is always free.

Research Methods Knowledge Base

- Navigating the Knowledge Base

- Five Big Words

- Types of Research Questions

- Time in Research

- Types of Relationships

- Types of Data

- Unit of Analysis

- Two Research Fallacies

- Philosophy of Research

- Ethics in Research

- Conceptualizing

- Evaluation Research

- Measurement

- Research Design

- Table of Contents

Fully-functional online survey tool with various question types, logic, randomisation, and reporting for unlimited number of surveys.

Completely free for academics and students .

Language Of Research

Learning about research is a lot like learning about anything else. To start, you need to learn the jargon people use, the big controversies they fight over, and the different factions that define the major players. We’ll start by considering five really big multi-syllable words that researchers sometimes use to describe what they do. We’ll only do a few for now, to give you an idea of just how esoteric the discussion can get (but not enough to cause you to give up in total despair). We can then take on some of the major issues in research like the types of questions we can ask in a project, the role of time in research , and the different types of relationships we can estimate. Then we have to consider defining some basic terms like variable , hypothesis , data , and unit of analysis . If you’re like me, you hate learning vocabulary, so we’ll quickly move along to consideration of two of the major fallacies of research, just to give you an idea of how wrong even researchers can be if they’re not careful (of course, there’s always a certainly probability that they’ll be wrong even if they’re extremely careful).

Cookie Consent

Conjointly uses essential cookies to make our site work. We also use additional cookies in order to understand the usage of the site, gather audience analytics, and for remarketing purposes.

For more information on Conjointly's use of cookies, please read our Cookie Policy .

Which one are you?

I am new to conjointly, i am already using conjointly.

- Advanced Skills

- Roots & Affixes

- Grammar Review

- Verb Tenses

- Common Idioms

- Learning English Plan

- Pronunciation

- TOEFL & IELTS Vocab.

- Vocab. Games

- Grammar Practice

- Comprehension & Fluency Practice

- Suggested Reading

- Lessons & Courses

- Lesson Plans & Ideas

- ESL Worksheets+

- What's New?

The Language of Research: an Explanation and Examples

Learning the language of research can help you understand research answers to important problems. It can also help you read academic texts (and tests) more easily.

This page explains key words for understanding the process of research. It talks about what can go wrong, leading to false or misleading results.

Then it links to several examples of research , so you can see how scientists use these words.

At the bottom is a link to a crossword puzzle . Use it to check your understanding of many important words used in research reports.

The Research Process

Research starts with a question or a problem. Researchers first find out what others have already learned about the subject.

If the question has not been fully answered, they figure out a way to get more information. They may do further observations or perform an experiment to test their idea.

Next they analyze the data (information) they have collected. Then they publish their procedures, data, and conclusions. This allows other scientists to repeat the experiments and double-check the conclusions.

The “gold standard” (best proof) of clinical research is a double-blind trial. That is an experiment with two (or more) groups of people in which only one group receives the drug or treatment being tested. The other group gets a placebo.

(A placebo is a “sugar pill” or other treatment that looks and feels like the experimental treatment but has no active ingredients. Any effects it has are psychological—because the participants expect it to work.)

A “double-blind” experiment gets its name because both the researchers and the participants are “blind” during the test. Nobody knows until the experiment has finished which group got the treatment and which group got an inactive placebo. That helps prevent people's expectations from distorting (twisting or changing) the results.

The treatment being tested should give significantly better results than the placebo. If not, any apparent difference it makes may be due to people’s hopes and expectations. So a double-blind trial is a way to check the effectiveness of a treatment.

The Language of Research: Describing Problems (Bias, Errors, and Distortion)

The language of research: describing errors.

There are several reasons research results can be misleading. There may be flaws in the research design. Researchers may make mistakes during the experiment or when analyzing the data. They may even be biased: wanting certain results so much that they influence the results.

Sometimes groups that might profit from the results pay for the research but onl report it if they get the results they want.

Here is an article , and then a TED talk , that explain these problems in more depth. (They aso show how to use the language for errors.) The article emphasizes the importance of having other researchers repeat important experiments. If other researchers get the same results, people can have more confidence in them.

The TED talk gives some clues to recognize when some research results may be biased or missing. (The speaker presents some very useful information. However, he talks quickly and uses a lot of British slang. If you find listening difficult, try reading the written transcript of his talk.)

Examples of the Language of Research

Research Study 1: Drug Interactions

Doctors know a lot about the side effects of single medications. They have also studied some interactions between two drugs. But what can happen when a person takes more than two (as many patients with serious health problems do)? This talk discusses the need for more research on drug interactions, even when each is safe by itself.

Study 2: The Effects of Green Spaces on Health

This study finds major health benefits for city residents who live near parks.

Study 3: Forest Re-growth Helps the Climate

This article discusses how the regeneration of tropical forests can reduce global warming. With more trees, more carbon dioxide is taken out of the air and stored in the trees.

Practice the Language of Research with a Crossword

Right-click here for the crossword , and here for the answers .

You can practice more research vocabulary with Scientific Method Vocabulary , as well as Science Vocabulary , or a gap-fill practice on climate change at Conservation Terminology .

Home > Learn English Vocabulary > The Language of Research.

Didn't find what you needed? Explain what you want in the search box below. (For example, cognates, past tense practice, or 'get along with.') Click to see the related pages on EnglishHints.

New! Comments

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

What's New?-- site blog

Learn about new and updated pages on EnglishHints, with just enough information to decide if you want to read more.

Do you already use English in your profession or studies-- but realize you need more advanced English or communication skills in certain areas?

I can help-- with targeted suggestions & practice on EnglishHints or with coaching or specialized help for faster results. Let me know. I can suggest resources or we can arrange a call.

Vocabulary in Minutes a Month

Sign up for our free newsletter, English Detective . In a few minutes twice a month you can:

- Improve your reading fluency with selected articles & talks on one subject (for repeated use of key words)

- Understand and practice those words using explanations, crosswords, and more

- Feel more confident about your English reading and vocab. skills-- and more prepared for big tests & challenges

For information (and a free bonus), see Building Vocabulary

Home | About me | Privacy Policy | Contact me | Affiliate Disclosure

Language and Scientific Research

- © 2021

- Wenceslao J. Gonzalez 0

Center for Research in Philosophy of Science and Technology, University of A Coruña, Ferrol, Spain

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Provides a comprehensive exploration of the semantics of science

Covers both basic scientific research and the development of applied science

Argues that language affects the structure and dynamics of science and is therefore not a mere expressive instrumental sign

1578 Accesses

3 Citations

Buy print copy

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Table of contents (9 chapters)

Front matter, the relevance of language for scientific research.

Wenceslao J. Gonzalez

The Problem of Reference and Potentialities of the Language in Science

Semantics of science and theory of reference: an analysis of the role of language in basic science and applied science, on the role of language in scientific research: language as analytic, expressive, and explanatory tool.

- Ladislav Kvasz

Language and Change in Scientific Research: Evolution and Historicity

Scientific inquiry and the evolution of language.

- Jeffrey Barrett

Language, History and the Making of Accurate Observations

- Anastasios Brenner

Scientific Language in the Context of Truth and Fiction

The evolution of truth and belief, models, fictions and artifacts.

- Tarja Knuuttila

Language in Mathematics and in Empirical Sciences

On mathematical language: characteristics, semiosis and indispensability.

- Jesus Alcolea

Characterization of Scientific Prediction from Language: An Analysis of Nicholas Rescher’s Proposal

- Amanda Guillan

Back Matter

- Historicity

- Mathhematics

About this book

This book analyzes the role of language in scientific research and develops the semantics of science from different angles. The philosophical investigation of the volume is divided into four parts, which covers both basic science and applied science: I) The Problem of Reference and Potentialities of the Language in Science; II) Language and Change in Scientific Research: Evolution and Historicity; III) Scientific Language in the Context of Truth and Fiction; and IV) Language in Mathematics and in Empirical Sciences.

Editors and Affiliations

About the editor, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Language and Scientific Research

Editors : Wenceslao J. Gonzalez

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60537-7

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy , Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-030-60536-0 Published: 28 April 2021

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-60539-1 Published: 28 April 2022

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-60537-7 Published: 27 April 2021

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XI, 285

Number of Illustrations : 15 b/w illustrations

Topics : Philosophy of Science , Philosophy of Language

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Language and power.

- Sik Hung Ng Sik Hung Ng Department of Psychology, Renmin University of China

- and Fei Deng Fei Deng School of Foreign Studies, South China Agricultural University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.436

- Published online: 22 August 2017

Five dynamic language–power relationships in communication have emerged from critical language studies, sociolinguistics, conversation analysis, and the social psychology of language and communication. Two of them stem from preexisting powers behind language that it reveals and reflects, thereby transferring the extralinguistic powers to the communication context. Such powers exist at both the micro and macro levels. At the micro level, the power behind language is a speaker’s possession of a weapon, money, high social status, or other attractive personal qualities—by revealing them in convincing language, the speaker influences the hearer. At the macro level, the power behind language is the collective power (ethnolinguistic vitality) of the communities that speak the language. The dominance of English as a global language and international lingua franca, for example, has less to do with its linguistic quality and more to do with the ethnolinguistic vitality of English-speakers worldwide that it reflects. The other three language–power relationships refer to the powers of language that are based on a language’s communicative versatility and its broad range of cognitive, communicative, social, and identity functions in meaning-making, social interaction, and language policies. Such language powers include, first, the power of language to maintain existing dominance in legal, sexist, racist, and ageist discourses that favor particular groups of language users over others. Another language power is its immense impact on national unity and discord. The third language power is its ability to create influence through single words (e.g., metaphors), oratories, conversations and narratives in political campaigns, emergence of leaders, terrorist narratives, and so forth.

- power behind language

- power of language

- intergroup communication

- World Englishes

- oratorical power

- conversational power

- leader emergence

- al-Qaeda narrative

- social identity approach

Introduction

Language is for communication and power.

Language is a natural human system of conventionalized symbols that have understood meanings. Through it humans express and communicate their private thoughts and feelings as well as enact various social functions. The social functions include co-constructing social reality between and among individuals, performing and coordinating social actions such as conversing, arguing, cheating, and telling people what they should or should not do. Language is also a public marker of ethnolinguistic, national, or religious identity, so strong that people are willing to go to war for its defense, just as they would defend other markers of social identity, such as their national flag. These cognitive, communicative, social, and identity functions make language a fundamental medium of human communication. Language is also a versatile communication medium, often and widely used in tandem with music, pictures, and actions to amplify its power. Silence, too, adds to the force of speech when it is used strategically to speak louder than words. The wide range of language functions and its versatility combine to make language powerful. Even so, this is only one part of what is in fact a dynamic relationship between language and power. The other part is that there is preexisting power behind language which it reveals and reflects, thereby transferring extralinguistic power to the communication context. It is thus important to delineate the language–power relationships and their implications for human communication.

This chapter provides a systematic account of the dynamic interrelationships between language and power, not comprehensively for lack of space, but sufficiently focused so as to align with the intergroup communication theme of the present volume. The term “intergroup communication” will be used herein to refer to an intergroup perspective on communication, which stresses intergroup processes underlying communication and is not restricted to any particular form of intergroup communication such as interethnic or intergender communication, important though they are. It echoes the pioneering attempts to develop an intergroup perspective on the social psychology of language and communication behavior made by pioneers drawn from communication, social psychology, and cognate fields (see Harwood et al., 2005 ). This intergroup perspective has fostered the development of intergroup communication as a discipline distinct from and complementing the discipline of interpersonal communication. One of its insights is that apparently interpersonal communication is in fact dynamically intergroup (Dragojevic & Giles, 2014 ). For this and other reasons, an intergroup perspective on language and communication behavior has proved surprisingly useful in revealing intergroup processes in health communication (Jones & Watson, 2012 ), media communication (Harwood & Roy, 2005 ), and communication in a variety of organizational contexts (Giles, 2012 ).

The major theoretical foundation that has underpinned the intergroup perspective is social identity theory (Tajfel, 1982 ), which continues to service the field as a metatheory (Abrams & Hogg, 2004 ) alongside relatively more specialized theories such as ethnolinguistic identity theory (Harwood et al., 1994 ), communication accommodation theory (Palomares et al., 2016 ), and self-categorization theory applied to intergroup communication (Reid et al., 2005 ). Against this backdrop, this chapter will be less concerned with any particular social category of intergroup communication or variant of social identity theory, and more with developing a conceptual framework of looking at the language–power relationships and their implications for understanding intergroup communication. Readers interested in an intra- or interpersonal perspective may refer to the volume edited by Holtgraves ( 2014a ).

Conceptual Approaches to Power

Bertrand Russell, logician cum philosopher and social activist, published a relatively little-known book on power when World War II was looming large in Europe (Russell, 2004 ). In it he asserted the fundamental importance of the concept of power in the social sciences and likened its importance to the concept of energy in the physical sciences. But unlike physical energy, which can be defined in a formula (e.g., E=MC 2 ), social power has defied any such definition. This state of affairs is not unexpected because the very nature of (social) power is elusive. Foucault ( 1979 , p. 92) has put it this way: “Power is everywhere, not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere.” This view is not beyond criticism but it does highlight the elusiveness of power. Power is also a value-laden concept meaning different things to different people. To functional theorists and power-wielders, power is “power to,” a responsibility to unite people and do good for all. To conflict theorists and those who are dominated, power is “power over,” which corrupts and is a source of social conflict rather than integration (Lenski, 1966 ; Sassenberg et al., 2014 ). These entrenched views surface in management–labor negotiations and political debates between government and opposition. Management and government would try to frame the negotiation in terms of “power to,” whereas labor and opposition would try to frame the same in “power over” in a clash of power discourses. The two discourses also interchange when the same speakers reverse their power relations: While in opposition, politicians adhere to “power over” rhetorics, once in government, they talk “power to.” And vice versa.

The elusive and value-laden nature of power has led to a plurality of theoretical and conceptual approaches. Five approaches that are particularly pertinent to the language–power relationships will be discussed, and briefly so because of space limitation. One approach views power in terms of structural dominance in society by groups who own and/or control the economy, the government, and other social institutions. Another approach views power as the production of intended effects by overcoming resistance that arises from objective conflict of interests or from psychological reactance to being coerced, manipulated, or unfairly treated. A complementary approach, represented by Kurt Lewin’s field theory, takes the view that power is not the actual production of effects but the potential for doing this. It looks behind power to find out the sources or bases of this potential, which may stem from the power-wielders’ access to the means of punishment, reward, and information, as well as from their perceived expertise and legitimacy (Raven, 2008 ). A fourth approach views power in terms of the balance of control/dependence in the ongoing social exchange between two actors that takes place either in the absence or presence of third parties. It provides a structural account of power-balancing mechanisms in social networking (Emerson, 1962 ), and forms the basis for combining with symbolic interaction theory, which brings in subjective factors such as shared social cognition and affects for the analysis of power in interpersonal and intergroup negotiation (Stolte, 1987 ). The fifth, social identity approach digs behind the social exchange account, which has started from control/dependence as a given but has left it unexplained, to propose a three-process model of power emergence (Turner, 2005 ). According to this model, it is psychological group formation and associated group-based social identity that produce influence; influence then cumulates to form the basis of power, which in turn leads to the control of resources.

Common to the five approaches above is the recognition that power is dynamic in its usage and can transform from one form of power to another. Lukes ( 2005 ) has attempted to articulate three different forms or faces of power called “dimensions.” The first, behavioral dimension of power refers to decision-making power that is manifest in the open contest for dominance in situations of objective conflict of interests. Non-decision-making power, the second dimension, is power behind the scene. It involves the mobilization of organizational bias (e.g., agenda fixing) to keep conflict of interests from surfacing to become public issues and to deprive oppositions of a communication platform to raise their voices, thereby limiting the scope of decision-making to only “safe” issues that would not challenge the interests of the power-wielder. The third dimension is ideological and works by socializing people’s needs and values so that they want the wants and do the things wanted by the power-wielders, willingly as their own. Conflict of interests, opposition, and resistance would be absent from this form of power, not because they have been maneuvered out of the contest as in the case of non-decision-making power, but because the people who are subject to power are no longer aware of any conflict of interest in the power relationship, which may otherwise ferment opposition and resistance. Power in this form can be exercised without the application of coercion or reward, and without arousing perceived manipulation or conflict of interests.

Language–Power Relationships

As indicated in the chapter title, discussion will focus on the language–power relationships, and not on language alone or power alone, in intergroup communication. It draws from all the five approaches to power and can be grouped for discussion under the power behind language and the power of language. In the former, language is viewed as having no power of its own and yet can produce influence and control by revealing the power behind the speaker. Language also reflects the collective/historical power of the language community that uses it. In the case of modern English, its preeminent status as a global language and international lingua franca has shaped the communication between native and nonnative English speakers because of the power of the English-speaking world that it reflects, rather than because of its linguistic superiority. In both cases, language provides a widely used conventional means to transfer extralinguistic power to the communication context. Research on the power of language takes the view that language has power of its own. This power allows a language to maintain the power behind it, unite or divide a nation, and create influence.

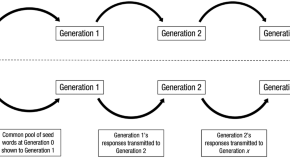

In Figure 1 we have grouped the five language–power relationships into five boxes. Note that the boundary between any two boxes is not meant to be rigid but permeable. For example, by revealing the power behind a message (box 1), a message can create influence (box 5). As another example, language does not passively reflect the power of the language community that uses it (box 2), but also, through its spread to other language communities, generates power to maintain its preeminence among languages (box 3). This expansive process of language power can be seen in the rise of English to global language status. A similar expansive process also applies to a particular language style that first reflects the power of the language subcommunity who uses the style, and then, through its common acceptance and usage by other subcommunities in the country, maintains the power of the subcommunity concerned. A prime example of this type of expansive process is linguistic sexism, which reflects preexisting male dominance in society and then, through its common usage by both sexes, contributes to the maintenance of male dominance. Other examples are linguistic racism and the language style of the legal profession, each of which, like linguistic sexism and the preeminence of the English language worldwide, has considerable impact on individuals and society at large.

Space precludes a full discussion of all five language–power relationships. Instead, some of them will warrant only a brief mention, whereas others will be presented in greater detail. The complexity of the language–power relations and their cross-disciplinary ramifications will be evident in the multiple sets of interrelated literatures that we cite from. These include the social psychology of language and communication, critical language studies (Fairclough, 1989 ), sociolinguistics (Kachru, 1992 ), and conversation analysis (Sacks et al., 1974 ).

Figure 1. Power behind language and power of language.

Power Behind Language

Language reveals power.

When negotiating with police, a gang may issue the threatening message, “Meet our demands, or we will shoot the hostages!” The threatening message may succeed in coercing the police to submit; its power, however, is more apparent than real because it is based on the guns gangsters posses. The message merely reveals the power of a weapon in their possession. Apart from revealing power, the gangsters may also cheat. As long as the message comes across as credible and convincing enough to arouse overwhelming fear, it would allow them to get away with their demands without actually possessing any weapon. In this case, language is used to produce an intended effect despite resistance by deceptively revealing a nonexisting power base and planting it in the mind of the message recipient. The literature on linguistic deception illustrates the widespread deceptive use of language-reveals-power to produce intended effects despite resistance (Robinson, 1996 ).

Language Reflects Power

Ethnolinguistic vitality.

The language that a person uses reflects the language community’s power. A useful way to think about a language community’s linguistic power is through the ethnolinguistic vitality model (Bourhis et al., 1981 ; Harwood et al., 1994 ). Language communities in a country vary in absolute size overall and, just as important, a relative numeric concentration in particular regions. Francophone Canadians, though fewer than Anglophone Canadians overall, are concentrated in Quebec to give them the power of numbers there. Similarly, ethnic minorities in mainland China have considerable power of numbers in those autonomous regions where they are concentrated, such as Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Collectively, these factors form the demographic base of the language community’s ethnolinguistic vitality, an index of the community’s relative linguistic dominance. Another base of ethnolinguistic vitality is institutional representations of the language community in government, legislatures, education, religion, the media, and so forth, which afford its members institutional leadership, influence, and control. Such institutional representation is often reinforced by a language policy that installs the language as the nation’s sole official language. The third base of ethnolinguistic vitality comprises sociohistorical and cultural status of the language community inside the nation and internationally. In short, the dominant language of a nation is one that comes from and reflects the high ethnolinguistic vitality of its language community.

An important finding of ethnolinguistic vitality research is that it is perceived vitality, and not so much its objective demographic-institutional-cultural strengths, that influences language behavior in interpersonal and intergroup contexts. Interestingly, the visibility and salience of languages shown on public and commercial signs, referred to as the “linguistic landscape,” serve important informational and symbolic functions as a marker of their relative vitality, which in turn affects the use of in-group language in institutional settings (Cenoz & Gorter, 2006 ; Landry & Bourhis, 1997 ).

World Englishes and Lingua Franca English

Another field of research on the power behind and reflected in language is “World Englishes.” At the height of the British Empire English spread on the back of the Industrial Revolution and through large-scale migrations of Britons to the “New World,” which has since become the core of an “inner circle” of traditional native English-speaking nations now led by the United States (Kachru, 1992 ). The emergent wealth and power of these nations has maintained English despite the decline of the British Empire after World War II. In the post-War era, English has become internationalized with the support of an “outer circle” nations and, later, through its spread to “expanding circle” nations. Outer circle nations are made up mostly of former British colonies such as India, Pakistan, and Nigeria. In compliance with colonial language policies that institutionalized English as the new colonial national language, a sizeable proportion of the colonial populations has learned and continued using English over generations, thereby vastly increasing the number of English speakers over and above those in the inner circle nations. The expanding circle encompasses nations where English has played no historical government roles, but which are keen to appropriate English as the preeminent foreign language for local purposes such as national development, internationalization of higher education, and participation in globalization (e.g., China, Indonesia, South Korea, Japan, Egypt, Israel, and continental Europe).

English is becoming a global language with official or special status in at least 75 countries (British Council, n.d. ). It is also the language choice in international organizations and companies, as well as academia, and is commonly used in trade, international mass media, and entertainment, and over the Internet as the main source of information. English native speakers can now follow the worldwide English language track to find jobs overseas without having to learn the local language and may instead enjoy a competitive language advantage where the job requires English proficiency. This situation is a far cry from the colonial era when similar advantages had to come under political patronage. Alongside English native speakers who work overseas benefitting from the preeminence of English over other languages, a new phenomenon of outsourcing international call centers away from the United Kingdom and the United States has emerged (Friginal, 2007 ). Callers can find the information or help they need from people stationed in remote places such as India or the Philippines where English has penetrated.

As English spreads worldwide, it has also become the major international lingua franca, serving some 800 million multilinguals in Asia alone, and numerous others elsewhere (Bolton, 2008 ). The practical importance of this phenomenon and its impact on English vocabulary, grammar, and accent have led to the emergence of a new field of research called “English as a lingua franca” (Brosch, 2015 ). The twin developments of World Englishes and lingua franca English raise interesting and important research questions. A vast area of research lies in waiting.

Several lines of research suggest themselves from an intergroup communication perspective. How communicatively effective are English native speakers who are international civil servants in organizations such as the UN and WTO, where they habitually speak as if they were addressing their fellow natives without accommodating to the international audience? Another line of research is lingua franca English communication between two English nonnative speakers. Their common use of English signals a joint willingness of linguistic accommodation, motivated more by communication efficiency of getting messages across and less by concerns of their respective ethnolinguistic identities. An intergroup communication perspective, however, would sensitize researchers to social identity processes and nonaccommodation behaviors underneath lingua franca communication. For example, two nationals from two different countries, X and Y, communicating with each other in English are accommodating on the language level; at the same time they may, according to communication accommodation theory, use their respective X English and Y English for asserting their ethnolinguistic distinctiveness whilst maintaining a surface appearance of accommodation. There are other possibilities. According to a survey of attitudes toward English accents, attachment to “standard” native speaker models remains strong among nonnative English speakers in many countries (Jenkins, 2009 ). This suggests that our hypothetical X and Y may, in addition to asserting their respective Englishes, try to outperform one another in speaking with overcorrect standard English accents, not so much because they want to assert their respective ethnolinguistic identities, but because they want to project a common in-group identity for positive social comparison—“We are all English-speakers but I am a better one than you!”

Many countries in the expanding circle nations are keen to appropriate English for local purposes, encouraging their students and especially their educational elites to learn English as a foreign language. A prime example is the Learn-English Movement in China. It has affected generations of students and teachers over the past 30 years and consumed a vast amount of resources. The results are mixed. Even more disturbing, discontents and backlashes have emerged from anti-English Chinese motivated to protect the vitality and cultural values of the Chinese language (Sun et al., 2016 ). The power behind and reflected in modern English has widespread and far-reaching consequences in need of more systematic research.

Power of Language

Language maintains existing dominance.

Language maintains and reproduces existing dominance in three different ways represented respectively by the ascent of English, linguistic sexism, and legal language style. For reasons already noted, English has become a global language, an international lingua franca, and an indispensable medium for nonnative English speaking countries to participate in the globalized world. Phillipson ( 2009 ) referred to this phenomenon as “linguistic imperialism.” It is ironic that as the spread of English has increased the extent of multilingualism of non-English-speaking nations, English native speakers in the inner circle of nations have largely remained English-only. This puts pressure on the rest of the world to accommodate them in English, the widespread use of which maintains its preeminence among languages.

A language evolves and changes to adapt to socially accepted word meanings, grammatical rules, accents, and other manners of speaking. What is acceptable or unacceptable reflects common usage and hence the numerical influence of users, but also the elites’ particular language preferences and communication styles. Research on linguistic sexism has shown, for example, a man-made language such as English (there are many others) is imbued with sexist words and grammatical rules that reflect historical male dominance in society. Its uncritical usage routinely by both sexes in daily life has in turn naturalized male dominance and associated sexist inequalities (Spender, 1998 ). Similar other examples are racist (Reisigl & Wodak, 2005 ) and ageist (Ryan et al., 1995 ) language styles.

Professional languages are made by and for particular professions such as the legal profession (Danet, 1980 ; Mertz et al., 2016 ; O’Barr, 1982 ). The legal language is used not only among members of the profession, but also with the general public, who may know each and every word in a legal document but are still unable to decipher its meaning. Through its language, the legal profession maintains its professional dominance with the complicity of the general public, who submits to the use of the language and accedes to the profession’s authority in interpreting its meanings in matters relating to their legal rights and obligations. Communication between lawyers and their “clients” is not only problematic, but the public’s continual dependence on the legal language contributes to the maintenance of the dominance of the profession.

Language Unites and Divides a Nation

A nation of many peoples who, despite their diverse cultural and ethnic background, all speak in the same tongue and write in the same script would reap the benefit of the unifying power of a common language. The power of the language to unite peoples would be stronger if it has become part of their common national identity and contributed to its vitality and psychological distinctiveness. Such power has often been seized upon by national leaders and intellectuals to unify their countries and serve other nationalistic purposes (Patten, 2006 ). In China, for example, Emperor Qin Shi Huang standardized the Chinese script ( hanzi ) as an important part of the reforms to unify the country after he had defeated the other states and brought the Warring States Period ( 475–221 bc ) to an end. A similar reform of language standardization was set in motion soon after the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty ( ad 1644–1911 ), by simplifying some of the hanzi and promoting Putonghua as the national standard oral language. In the postcolonial part of the world, language is often used to service nationalism by restoring the official status of their indigenous language as the national language whilst retaining the colonial language or, in more radical cases of decolonization, relegating the latter to nonofficial status. Yet language is a two-edged sword: It can also divide a nation. The tension can be seen in competing claims to official-language status made by minority language communities, protest over maintenance of minority languages, language rights at schools and in courts of law, bilingual education, and outright language wars (Calvet, 1998 ; DeVotta, 2004 ).

Language Creates Influence

In this section we discuss the power of language to create influence through single words and more complex linguistic structures ranging from oratories and conversations to narratives/stories.

Power of Single Words

Learning a language empowers humans to master an elaborate system of conventions and the associations between words and their sounds on the one hand, and on the other hand, categories of objects and relations to which they refer. After mastering the referential meanings of words, a person can mentally access the objects and relations simply by hearing or reading the words. Apart from their referential meanings, words also have connotative meanings with their own social-cognitive consequences. Together, these social-cognitive functions underpin the power of single words that has been extensively studied in metaphors, which is a huge research area that crosses disciplinary boundaries and probes into the inner workings of the brain (Benedek et al., 2014 ; Landau et al., 2014 ; Marshal et al., 2007 ). The power of single words extends beyond metaphors. It can be seen in misleading words in leading questions (Loftus, 1975 ), concessive connectives that reverse expectations from real-world knowledge (Xiang & Kuperberg, 2014 ), verbs that attribute implicit causality to either verb subject or object (Hartshorne & Snedeker, 2013 ), “uncertainty terms” that hedge potentially face-threatening messages (Holtgraves, 2014b ), and abstract words that signal power (Wakslak et al., 2014 ).

The literature on the power of single words has rarely been applied to intergroup communication, with the exception of research arising from the linguistic category model (e.g., Semin & Fiedler, 1991 ). The model distinguishes among descriptive action verbs (e.g., “hits”), interpretative action verbs (e.g., “hurts”) and state verbs (e.g., “hates”), which increase in abstraction in that order. Sentences made up of abstract verbs convey more information about the protagonist, imply greater temporal and cross-situational stability, and are more difficult to disconfirm. The use of abstract language to represent a particular behavior will attribute the behavior to the protagonist rather than the situation and the resulting image of the protagonist will persist despite disconfirming information, whereas the use of concrete language will attribute the same behavior more to the situation and the resulting image of the protagonist will be easier to change. According to the linguistic intergroup bias model (Maass, 1999 ), abstract language will be used to represent positive in-group and negative out-group behaviors, whereas concrete language will be used to represent negative in-group and positive out-group behaviors. The combined effects of the differential use of abstract and concrete language would, first, lead to biased attribution (explanation) of behavior privileging the in-group over the out-group, and second, perpetuate the prejudiced intergroup stereotypes. More recent research has shown that linguistic intergroup bias varies with the power differential between groups—it is stronger in high and low power groups than in equal power groups (Rubini et al., 2007 ).

Oratorical Power

A charismatic speaker may, by the sheer force of oratory, buoy up people’s hopes, convert their hearts from hatred to forgiveness, or embolden them to take up arms for a cause. One may recall moving speeches (in English) such as Susan B. Anthony’s “On Women’s Right to Vote,” Winston Churchill’s “We Shall Fight on the Beaches,” Mahatma Gandhi’s “Quit India,” or Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream.” The speech may be delivered face-to-face to an audience, or broadcast over the media. The discussion below focuses on face-to-face oratories in political meetings.

Oratorical power may be measured in terms of money donated or pledged to the speaker’s cause, or, in a religious sermon, the number of converts made. Not much research has been reported on these topics. Another measurement approach is to count the frequency of online audience responses that a speech has generated, usually but not exclusively in the form of applause. Audience applause can be measured fairly objectively in terms of frequency, length, or loudness, and collected nonobtrusively from a public recording of the meeting. Audience applause affords researchers the opportunity to explore communicative and social psychological processes that underpin some aspects of the power of rhetorical formats. Note, however, that not all incidences of audience applause are valid measures of the power of rhetoric. A valid incidence should be one that is invited by the speaker and synchronized with the flow of the speech, occurring at the appropriate time and place as indicated by the rhetorical format. Thus, an uninvited incidence of applause would not count, nor is one that is invited but has occurred “out of place” (too soon or too late). Furthermore, not all valid incidences are theoretically informative to the same degree. An isolated applause from just a handful of the audience, though valid and in the right place, has relatively little theoretical import for understanding the power of rhetoric compared to one that is made by many acting in unison as a group. When the latter occurs, it would be a clear indication of the power of rhetorically formulated speech. Such positive audience response constitutes the most direct and immediate means by which an audience can display its collective support for the speaker, something which they would not otherwise show to a speech of less power. To influence and orchestrate hundreds and thousands of people in the audience to precisely coordinate their response to applaud (and cheer) together as a group at the right time and place is no mean feat. Such a feat also influences the wider society through broadcast on television and other news and social media. The combined effect could be enormous there and then, and its downstream influence far-reaching, crossing country boarders and inspiring generations to come.

To accomplish the feat, an orator has to excite the audience to applaud, build up the excitement to a crescendo, and simultaneously cue the audience to synchronize their outburst of stored-up applause with the ongoing speech. Rhetorical formats that aid the orator to accomplish the dual functions include contrast, list, puzzle solution, headline-punchline, position-taking, and pursuit (Heritage & Greatbatch, 1986 ). To illustrate, we cite the contrast and list formats.

A contrast, or antithesis, is made up of binary schemata such as “too much” and “too little.” Heritage and Greatbatch ( 1986 , p. 123) reported the following example:

Governments will argue that resources are not available to help disabled people. The fact is that too much is spent on the munitions of war, and too little is spent on the munitions of peace [italics added]. As the audience is familiar with the binary schema of “too much” and “too little” they can habitually match the second half of the contrast against the first half. This decoding process reinforces message comprehension and helps them to correctly anticipate and applaud at the completion point of the contrast. In the example quoted above, the speaker micropaused for 0.2 seconds after the second word “spent,” at which point the audience began to applaud in anticipation of the completion point of the contrast, and applauded more excitedly upon hearing “. . . on the munitions of peace.” The applause continued and lasted for 9.2 long seconds.

A list is usually made up of a series of three parallel words, phrases or clauses. “Government of the people, by the people, for the people” is a fine example, as is Obama’s “It’s been a long time coming, but tonight, because of what we did on this day , in this election , at this defining moment , change has come to America!” (italics added) The three parts in the list echo one another, step up the argument and its corresponding excitement in the audience as they move from one part to the next. The third part projects a completion point to cue the audience to get themselves ready to display their support via applause, cheers, and so forth. In a real conversation this juncture is called a “transition-relevance place,” at which point a conversational partner (hearer) may take up a turn to speak. A skilful orator will micropause at that juncture to create a conversational space for the audience to take up their turn in applauding and cheering as a group.

As illustrated by the two examples above, speaker and audience collaborate to transform an otherwise monological speech into a quasiconversation, turning a passive audience into an active supportive “conversational” partner who, by their synchronized responses, reduces the psychological separation from the speaker and emboldens the latter’s self-confidence. Through such enjoyable and emotional participation collectively, an audience made up of formerly unconnected individuals with no strong common group identity may henceforth begin to feel “we are all one.” According to social identity theory and related theories (van Zomeren et al., 2008 ), the emergent group identity, politicized in the process, will in turn provide a social psychological base for collective social action. This process of identity making in the audience is further strengthened by the speaker’s frequent use of “we” as a first person, plural personal pronoun.

Conversational Power

A conversation is a speech exchange system in which the length and order of speaking turns have not been preassigned but require coordination on an utterance-by-utterance basis between two or more individuals. It differs from other speech exchange systems in which speaking turns have been preassigned and/or monitored by a third party, for example, job interviews and debate contests. Turn-taking, because of its centrality to conversations and the important theoretical issues that it raises for social coordination and implicit conversational conventions, has been the subject of extensive research and theorizing (Goodwin & Heritage, 1990 ; Grice, 1975 ; Sacks et al., 1974 ). Success at turn-taking is a key part of the conversational process leading to influence. A person who cannot do this is in no position to influence others in and through conversations, which are probably the most common and ubiquitous form of human social interaction. Below we discuss studies of conversational power based on conversational turns and applied to leader emergence in group and intergroup settings. These studies, as they unfold, link conversation analysis with social identity theory and expectation states theory (Berger et al., 1974 ).

A conversational turn in hand allows the speaker to influence others in two important ways. First, through current-speaker-selects-next the speaker can influence who will speak next and, indirectly, increases the probability that he or she will regain the turn after the next. A common method for selecting the next speaker is through tag questions. The current speaker (A) may direct a tag question such as “Ya know?” or “Don’t you agree?” to a particular hearer (B), which carries the illocutionary force of selecting the addressee to be the next speaker and, simultaneously, restraining others from self-selecting. The A 1 B 1 sequence of exchange has been found to have a high probability of extending into A 1 B 1 A 2 in the next round of exchange, followed by its continuation in the form of A 1 B 1 A 2 B 2 . For example, in a six-member group, the A 1 B 1 →A 1 B 1 A 2 sequence of exchange has more than 50% chance of extending to the A 1 B 1 A 2 B 2 sequence, which is well above chance level, considering that there are four other hearers who could intrude at either the A 2 or B 2 slot of turn (Stasser & Taylor, 1991 ). Thus speakership not only offers the current speaker the power to select the next speaker twice, but also to indirectly regain a turn.

Second, a turn in hand provides the speaker with an opportunity to exercise topic control. He or she can exercise non-decision-making power by changing an unfavorable or embarrassing topic to a safer one, thereby silencing or preventing it from reaching the “floor.” Conversely, he or she can exercise decision-making power by continuing or raising a topic that is favorable to self. Or the speaker can move on to talk about an innocuous topic to ease tension in the group.

Bales ( 1950 ) has studied leader emergence in groups made up of unacquainted individuals in situations where they have to bid or compete for speaking turns. Results show that individuals who talk the most have a much better chance of becoming leaders. Depending on the social orientations of their talk, they would be recognized as a task or relational leader. Subsequent research on leader emergence has shown that an even better behavioral predictor than volume of talk is the number of speaking turns. An obvious reason for this is that the volume of talk depends on the number of turns—it usually accumulates across turns, rather than being the result of a single extraordinary long turn of talk. Another reason is that more turns afford the speaker more opportunities to realize the powers of turns that have been explicated above. Group members who become leaders are the ones who can penetrate the complex, on-line conversational system to obtain a disproportionately large number of speaking turns by perfect timing at “transition-relevance places” to self-select as the next speaker or, paradoxical as it may seem, constructive interruptions (Ng et al., 1995 ).

More recent research has extended the experimental study of group leadership to intergroup contexts, where members belonging to two groups who hold opposing stances on a social or political issue interact within and also between groups. The results showed, first, that speaking turns remain important in leader emergence, but the intergroup context now generates social identity and self-categorization processes that selectively privilege particular forms of speech. What potential leaders say, and not only how many speaking turns they have gained, becomes crucial in conveying to group members that they are prototypical members of their group. Prototypical communication is enacted by adopting an accent, choosing code words, and speaking in a tone that characterize the in-group; above all, it is enacted through the content of utterances to represent or exemplify the in-group position. Such prototypical utterances that are directed successfully at the out-group correlate strongly with leader emergence (Reid & Ng, 2000 ). These out-group-directed prototypical utterances project an in-group identity that is psychologically distinctive from the out-group for in-group members to feel proud of and to rally together when debating with the out-group.

Building on these experimental results Reid and Ng ( 2003 ) developed a social identity theory of leadership to account for the emergence and maintenance of intergroup leadership, grounding it in case studies of the intergroup communication strategies that brought Ariel Sharon and John Howard to power in Israel and Australia, respectively. In a later development, the social identity account was fused with expectation states theory to explain how group processes collectively shape the behavior of in-group members to augment the prototypical communication behavior of the emergent leader (Reid & Ng, 2006 ). Specifically, when conversational influence gained through prototypical utterances culminates to form an incipient power hierarchy, group members develop expectations of who is and will be leading the group. Acting on these tacit expectations they collectively coordinate the behavior of each other to conform with the expectations by granting incipient leaders more speaking turns and supporting them with positive audience responses. In this way, group members collectively amplify the influence of incipient leaders and jointly propel them to leadership roles (see also Correll & Ridgeway, 2006 ). In short, the emergence of intergroup leaders is a joint process of what they do individually and what group members do collectively, enabled by speaking turns and mediated by social identity and expectation states processes. In a similar vein, Hogg ( 2014 ) has developed a social identity account of leadership in intergroup settings.

Narrative Power

Narratives and stories are closely related and are sometimes used interchangeably. However, it is useful to distinguish a narrative from a story and from other related terms such as discourse and frames. A story is a sequence of related events in the past recounted for rhetorical or ideological purposes, whereas a narrative is a coherent system of interrelated and sequentially organized stories formed by incorporating new stories and relating them to others so as to provide an ongoing basis for interpreting events, envisioning an ideal future, and motivating and justifying collective actions (Halverson et al., 2011 ). The temporal dimension and sense of movement in a narrative also distinguish it from discourse and frames. According to Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, and Roselle ( 2013 ), discourses are the raw material of communication that actors plot into a narrative, and frames are the acts of selecting and highlighting some events or issues to promote a particular interpretation, evaluation, and solution. Both discourse and frame lack the temporal and causal transformation of a narrative.

Pitching narratives at the suprastory level and stressing their temporal and transformational movements allows researchers to take a structurally more systemic and temporally more expansive view than traditional research on propaganda wars between nations, religions, or political systems (Halverson et al., 2011 ; Miskimmon et al., 2013 ). Schmid ( 2014 ) has provided an analysis of al-Qaeda’s “compelling narrative that authorizes its strategy, justifies its violent tactics, propagates its ideology and wins new recruits.” According to this analysis, the chief message of the narrative is “the West is at war with Islam,” a strategic communication that is fundamentally intergroup in both structure and content. The intergroup structure of al-Qaeda narrative includes the rhetorical constructions that there are a group grievance inflicted on Muslims by a Zionist–Christian alliance, a vision of the good society (under the Caliphate and sharia), and a path from grievance to the realization of the vision led by al-Qaeda in a violent jihad to eradicate Western influence in the Muslim world. The al-Qaeda narrative draws support not only from traditional Arab and Muslim cultural narratives interpreted to justify its unorthodox means (such as attacks against women and children), but also from pre-existing anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism propagated by some Arab governments, Soviet Cold War propaganda, anti-Western sermons by Muslim clerics, and the Israeli government’s treatment of Palestinians. It is deeply embedded in culture and history, and has reached out to numerous Muslims who have emigrated to the West.

The intergroup content of al-Qaeda narrative was shown in a computer-aided content analysis of 18 representative transcripts of propaganda speeches released between 2006–2011 by al-Qaeda leaders, totaling over 66,000 words (Cohen et al., 2016 ). As part of the study, an “Ideology Extraction using Linguistic Extremization” (IELEX) categorization scheme was developed for mapping the content of the corpus, which revealed 19 IELEX rhetorical categories referring to either the out-group/enemy or the in-group/enemy victims. The out-group/enemy was represented by four categories such as “The enemy is extremely negative (bloodthirsty, vengeful, brainwashed, etc.)”; whereas the in-group/enemy victims were represented by more categories such as “we are entirely innocent/good/virtuous.” The content of polarized intergroup stereotypes, demonizing “them” and glorifying “us,” echoes other similar findings (Smith et al., 2008 ), as well as the general finding of intergroup stereotyping in social psychology (Yzerbyt, 2016 ).

The success of the al-Qaeda narrative has alarmed various international agencies, individual governments, think tanks, and religious groups to spend huge sums of money on developing counternarratives that are, according to Schmid ( 2014 ), largely feeble. The so-called “global war on terror” has failed in its effort to construct effective counternarratives although al-Qaeda’s finance, personnel, and infrastructure have been much weakened. Ironically, it has developed into a narrative of its own, not so much for countering external extremism, but for promoting and justifying internal nationalistic extremist policies and influencing national elections. This reactive coradicalization phenomenon is spreading (Mink, 2015 ; Pratt, 2015 ; Reicher & Haslam, 2016 ).

Discussion and Future Directions

This chapter provides a systematic framework for understanding five language–power relationships, namely, language reveals power, reflects power, maintains existing dominance, unites and divides a nation, and creates influence. The first two relationships are derived from the power behind language and the last three from the power of language. Collectively they provide a relatively comprehensible framework for understanding the relationships between language and power, and not simply for understanding language alone or power alone separated from one another. The language–power relationships are dynamically interrelated, one influencing the other, and each can draw from an array of the cognitive, communicative, social, and identity functions of language. The framework is applicable to both interpersonal and intergroup contexts of communication, although for present purposes the latter has been highlighted. Among the substantive issues discussed in this chapter, English as a global language, oratorical and narrative power, and intergroup leadership stand out as particularly important for political and theoretical reasons.

In closing, we note some of the gaps that need to be filled and directions for further research. When discussing the powers of language to maintain and reflect existing dominance, we have omitted the countervailing power of language to resist or subvert existing dominance and, importantly, to create social change for the collective good. Furthermore, in this age of globalization and its discontents, English as a global language will increasingly be resented for its excessive unaccommodating power despite tangible lingua franca English benefits, and challenged by the expanding ethnolinguistic vitality of peoples who speak Arabic, Chinese, or Spanish. Internet communication is no longer predominantly in English, but is rapidly diversifying to become the modern Tower of Babel. And yet we have barely scratched the surface of these issues. Other glaring gaps include the omission of media discourse and recent developments in Corpus-based Critical Discourse Analysis (Loring, 2016 ), as well as the lack of reference to languages other than English that may cast one or more of the language–power relationships in a different light.

One of the main themes of this chapter—that the diverse language–power relationships are dynamically interrelated—clearly points to the need for greater theoretical fertilization across cognate disciplines. Our discussion of the three powers of language (boxes 3–5 in Figure 1 ) clearly points in this direction, most notably in the case of the powers of language to create influence through single words, oratories, conversations, and narratives, but much more needs to be done. The social identity approach will continue to serve as a meta theory of intergroup communication. To the extent that intergroup communication takes place in an existing power relation and that the changes that it seeks are not simply a more positive or psychologically distinctive social identity but greater group power and a more powerful social identity, the social identity approach has to incorporate power in its application to intergroup communication.

Further Reading

- Austin, J. L. (1975). How to do things with words . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Billig, M. (1991). Ideology and opinions: Studies in rhetorical psychology . Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Crystal, D. (2012). English as a global language , 2d ed. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Culpeper, J. (2011). Impoliteness . New York: John Wiley.

- Holtgraves, T. M. (2010). Social psychology and language: Words, utterances, and conversations. In S. Fiske , D. Gilbert , & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., pp. 1386–1422). New York: John Wiley.

- Mumby, D. K. (Ed.). (1993). Narrative and social control: Critical perspectives (Vol. 21). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Ng, S. H. , & Bradac, J. J. (1993). Power in language: Verbal communication and social influence . Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412994088.n202 .

- Abrams, D. , & Hogg, M. A. (2004). Metatheory: Lessons from social identity research. Personality and Social Psychology Review , 8 , 98–106.

- Bales, R. F. (1950). Interaction process analysis: A method for the study of small groups . Oxford: Addison-Wesley.

- Benedek, M. , Beaty, R. , Jauk, E. , Koschutnig, K. , Fink, A. , Silvia, P. J. , . . . & Neubauer, A. C. (2014). Creating metaphors: The neural basis of figurative language production. NeuroImage , 90 , 99–106.

- Berger, J. , Conner, T. L. , & Fisek, M. H. (Eds.). (1974). Expectation states theory: A theoretical research program . Cambridge, MA: Winthrop.

- Bolton, K. (2008). World Englishes today. In B. B. Kachru , Y. Kachru , & C. L. Nelson (Eds.), The handbook of world Englishes (pp. 240–269). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bourhis, R. Y. , Giles, H. , & Rosenthal, D. (1981). Notes on the construction of a “Subjective vitality questionnaire” for ethnolinguistic groups. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development , 2 , 145–155.

- British Council . (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.britishcouncil.org/learning-faq-the-english-language.htm .

- Brosch, C. (2015). On the conceptual history of the term Lingua Franca . Apples . Journal of Applied Language Studies , 9 (1), 71–85.

- Calvet, J. (1998). Language wars and linguistic politics . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cenoz, J. , & Gorter, D. (2006). Linguistic landscape and minority languages. International Journal of Multilingualism , 3 , 67–80.

- Cohen, S. J. , Kruglanski, A. , Gelfand, M. J. , Webber, D. , & Gunaratna, R. (2016). Al-Qaeda’s propaganda decoded: A psycholinguistic system for detecting variations in terrorism ideology . Terrorism and Political Violence , 1–30.

- Correll, S. J. , & Ridgeway, C. L. (2006). Expectation states theory . In L. DeLamater (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 29–51). Hoboken, NJ: Springer.

- Danet, B. (1980). Language in the legal process. Law and Society Review , 14 , 445–564.

- DeVotta, N. (2004). Blowback: Linguistic nationalism, institutional decay, and ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Dragojevic, M. , & Giles, H. (2014). Language and interpersonal communication: Their intergroup dynamics. In C. R. Berger (Ed.), Handbook of interpersonal communication (pp. 29–51). Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power–Dependence Relations. American Sociological Review , 27 , 31–41.

- Fairclough, N. L. (1989). Language and power . London: Longman.

- Foucault, M. (1979). The history of sexuality volume 1: An introduction . London: Allen Lane.

- Friginal, E. (2007). Outsourced call centers and English in the Philippines. World Englishes , 26 , 331–345.

- Giles, H. (Ed.) (2012). The handbook of intergroup communication . New York: Routledge.

- Goodwin, C. , & Heritage, J. (1990). Conversation analysis. Annual review of anthropology , 19 , 283–307.

- Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. In P. Cole & J. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and semantics (pp. 41–58). New York: Academic Press.

- Halverson, J. R. , Goodall H. L., Jr. , & Corman, S. R. (2011). Master narratives of Islamist extremism . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hartshorne, J. K. , & Snedeker, J. (2013). Verb argument structure predicts implicit causality: The advantages of finer-grained semantics. Language and Cognitive Processes , 28 , 1474–1508.

- Harwood, J. , Giles, H. , & Bourhis, R. Y. (1994). The genesis of vitality theory: Historical patterns and discoursal dimensions. International Journal of the Sociology of Language , 108 , 167–206.

- Harwood, J. , Giles, H. , & Palomares, N. A. (2005). Intergroup theory and communication processes. In J. Harwood & H. Giles (Eds.), Intergroup communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 1–20). New York: Peter Lang.

- Harwood, J. , & Roy, A. (2005). Social identity theory and mass communication research. In J. Harwood & H. Giles (Eds.), Intergroup communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 189–212). New York: Peter Lang.

- Heritage, J. , & Greatbatch, D. (1986). Generating applause: A study of rhetoric and response at party political conferences. American Journal of Sociology , 92 , 110–157.

- Hogg, M. A. (2014). From uncertainty to extremism: Social categorization and identity processes. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 23 , 338–342.

- Holtgraves, T. M. (Ed.). (2014a). The Oxford handbook of language and social psychology . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Holtgraves, T. M. (2014b). Interpreting uncertainty terms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 107 , 219–228.

- Jenkins, J. (2009). English as a lingua franca: interpretations and attitudes. World Englishes , 28 , 200–207.

- Jones, L. , & Watson, B. M. (2012). Developments in health communication in the 21st century. Journal of Language and Social Psychology , 31 , 415–436.

- Kachru, B. B. (1992). The other tongue: English across cultures . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Landau, M. J. , Robinson, M. D. , & Meier, B. P. (Eds.). (2014). The power of metaphor: Examining its influence on social life . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Landry, R. , & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality an empirical study. Journal of language and social psychology , 16 , 23–49.

- Lenski, G. (1966). Power and privilege: A theory of social stratification . New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Loftus, E. F. (1975). Leading questions and the eyewitness report. Cognitive Psychology , 7 , 560–572.

- Loring, A. (2016). Ideologies and collocations of “Citizenship” in media discourse: A corpus-based critical discourse analysis. In A. Loring & V. Ramanathan (Eds.), Language, immigration and naturalization: Legal and linguistic issues (chapter 9). Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.

- Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A radical view , 2d ed. New York: Palgrave.

- Maass, A. (1999). Linguistic intergroup bias: Stereotype perpetuation through language. Advances in experimental social psychology , 31 , 79–121.

- Marshal, N. , Faust, M. , Hendler, T. , & Jung-Beeman, M. (2007). An fMRI investigation of the neural correlates underlying the processing of novel metaphoric expressions. Brain and language , 100 , 115–126.

- Mertz, E. , Ford, W. K. , & Matoesian, G. (Eds.). (2016). Translating the social world for law: Linguistic tools for a new legal realism . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mink, C. (2015). It’s about the group, not god: Social causes and cures for terrorism. Journal for Deradicalization , 5 , 63–91.

- Miskimmon, A. , O’Loughlin, B. , & Roselle, L. (2013). Strategic narratives: Communicating power and the New World Order . New York: Routledge.

- Ng, S. H. , Brooke, M. & Dunne, M. (1995). Interruptions and influence in discussion groups. Journal of Language & Social Psychology , 14 , 369–381.

- O’Barr, W. M. (1982). Linguistic evidence: Language, power, and strategy in the courtroom . London: Academic Press.

- Palomares, N. A. , Giles, H. , Soliz, J. , & Gallois, C. (2016). Intergroup accommodation, social categories, and identities. In H. Giles (Ed.), Communication accommodation theory: Negotiating personal relationships and social identities across contexts (pp. 123–151). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Patten, A. (2006). The humanist roots of linguistic nationalism. History of Political Thought , 27 , 221–262.

- Phillipson, R. (2009). Linguistic imperialism continued . New York: Routledge.

- Pratt, D. (2015). Reactive co-radicalization: Religious extremism as mutual discontent. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion , 28 , 3–23.

- Raven, B. H. (2008). The bases of power and the power/interaction model of interpersonal influence. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy , 8 , 1–22.

- Reicher, S. D. , & Haslam, S. A. (2016). Fueling extremes. Scientific American Mind , 27 , 34–39.

- Reid, S. A. , Giles, H. , & Harwood, J. (2005). A self-categorization perspective on communication and intergroup relations. In J. Harwood & H. Giles (Eds.), Intergroup communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 241–264). New York: Peter Lang.

- Reid, S. A. , & Ng, S. H. (2000). Conversation as a resource for influence: Evidence for prototypical arguments and social identification processes. European Journal of Social Psychology , 30 , 83–100.

- Reid, S. A. , & Ng, S. H. (2003). Identity, power, and strategic social categorisations: Theorising the language of leadership. In P. van Knippenberg & M. A. Hogg (Eds.), Leadership and power: Identity processes in groups and organizations (pp. 210–223). London: SAGE.

- Reid, S. A. , & Ng, S. H. (2006). The dynamics of intragroup differentiation in an intergroup social context. Human Communication Research , 32 , 504–525.

- Reisigl, M. , & Wodak, R. (2005). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and antisemitism . London: Routledge.

- Robinson, W. P. (1996). Deceit, delusion, and detection . Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Rubini, M. , Moscatelli, S. , Albarello, F. , & Palmonari, A. (2007). Group power as a determinant of interdependence and intergroup discrimination. European Journal of Social Psychology , 37 (6), 1203–1221.

- Russell, B. (2004). Power: A new social analysis . Originally published in 1938. London: Routledge.

- Ryan, E. B. , Hummert, M. L. , & Boich, L. H. (1995). Communication predicaments of aging patronizing behavior toward older adults. Journal of Language and Social Psychology , 14 (1–2), 144–166.

- Sacks, H. , Schegloff, E. A. , & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. L anguage , 50 , 696–735.

- Sassenberg, K. , Ellemers, N. , Scheepers, D. , & Scholl, A. (2014). “Power corrupts” revisited: The role of construal of power as opportunity or responsibility. In J. -W. van Prooijen & P. A. M. van Lange (Eds.), Power, politics, and paranoia: Why people are suspicious of their leaders (pp. 73–87). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Schmid, A. P. (2014). Al-Qaeda’s “single narrative” and attempts to develop counter-narratives: The state of knowledge . The Hague, The Netherlands: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 26. Available at https://www.icct.nl/download/file/A-Schmid-Al-Qaedas-Single-Narrative-January-2014.pdf .

- Semin, G. R. , & Fiedler, K. (1991). The linguistic category model, its bases, applications and range. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 1–50). Chichester, U.K.: John Wiley.

- Smith, A. G. , Suedfeld, P. , Conway, L. G. , IIl, & Winter, D. G. (2008). The language of violence: Distinguishing terrorist from non-terrorist groups by thematic content analysis. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict , 1 (2), 142–163.

- Spender, D. (1998). Man made language , 4th ed. London: Pandora.

- Stasser, G. , & Taylor, L. (1991). Speaking turns in face-to-face discussions. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology , 60 , 675–684.

- Stolte, J. (1987). The formation of justice norms. American Sociological Review , 52 (6), 774–784.

- Sun, J. J. M. , Hu, P. , & Ng, S. H. (2016). Impact of English on education reforms in China: With reference to the learn-English movement, the internationalisation of universities and the English language requirement in college entrance examinations . Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development , 1–14 (Published online January 22, 2016).

- Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology , 33 , 1–39.

- Turner, J. C. (2005). Explaining the nature of power: A three—process theory. European Journal of Social Psychology , 35 , 1–22.

- Van Zomeren, M. , Postmes, T. , & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin , 134 (4), 504–535.

- Wakslak, C. J. , Smith, P. K. , & Han, A. (2014). Using abstract language signals power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 107 (1), 41–55.

- Xiang, M. , & Kuperberg, A. (2014). Reversing expectations during discourse comprehension . Language, Cognition and Neuroscience , 30 , 648–672.

- Yzerbyt, V. (2016). Intergroup stereotyping. Current Opinion in Psychology , 11 , 90–95.

Related Articles

- Language Attitudes

- Vitality Theory