Search form (GSE) 1

The psychology of emotional and cognitive empathy.

The study of empathy is an ongoing area of major interest for psychologists and neuroscientists in many fields, with new research appearing regularly.

Empathy is a broad concept that refers to the cognitive and emotional reactions of an individual to the observed experiences of another. Having empathy increases the likelihood of helping others and showing compassion. “Empathy is a building block of morality—for people to follow the Golden Rule, it helps if they can put themselves in someone else’s shoes,” according to the Greater Good Science Center , a research institute that studies the psychology, sociology, and neuroscience of well-being. “It is also a key ingredient of successful relationships because it helps us understand the perspectives, needs, and intentions of others.”

Though they may seem similar, there is a clear distinction between empathy and sympathy. According to Hodges and Myers in the Encyclopedia of Social Psychology , “Empathy is often defined as understanding another person’s experience by imagining oneself in that other person’s situation: One understands the other person’s experience as if it were being experienced by the self, but without the self actually experiencing it. A distinction is maintained between self and other. Sympathy, in contrast, involves the experience of being moved by, or responding in tune with, another person.”

Emotional and Cognitive Empathy

Researchers distinguish between two types of empathy. Especially in social psychology, empathy can be categorized as an emotional or cognitive response. Emotional empathy consists of three separate components, Hodges and Myers say. “The first is feeling the same emotion as another person … The second component, personal distress, refers to one’s own feelings of distress in response to perceiving another’s plight … The third emotional component, feeling compassion for another person, is the one most frequently associated with the study of empathy in psychology,” they explain.

It is important to note that feelings of distress associated with emotional empathy don’t necessarily mirror the emotions of the other person. Hodges and Myers note that, while empathetic people feel distress when someone falls, they aren’t in the same physical pain. This type of empathy is especially relevant when it comes to discussions of compassionate human behavior. There is a positive correlation between feeling empathic concern and being willing to help others. “Many of the most noble examples of human behavior, including aiding strangers and stigmatized people, are thought to have empathic roots,” according to Hodges and Myers. Debate remains concerning whether the impulse to help is based in altruism or self-interest.

The second type of empathy is cognitive empathy. This refers to how well an individual can perceive and understand the emotions of another. Cognitive empathy, also known as empathic accuracy, involves “having more complete and accurate knowledge about the contents of another person’s mind, including how the person feels,” Hodges and Myers say. Cognitive empathy is more like a skill: Humans learn to recognize and understand others’ emotional state as a way to process emotions and behavior. While it’s not clear exactly how humans experience empathy, there is a growing body of research on the topic.

How Do We Empathize?

Experts in the field of social neuroscience have developed two theories in an attempt to gain a better understanding of empathy. The first, Simulation Theory, “proposes that empathy is possible because when we see another person experiencing an emotion, we ‘simulate’ or represent that same emotion in ourselves so we can know firsthand what it feels like,” according to Psychology Today .

There is a biological component to this theory as well. Scientists have discovered preliminary evidence of “mirror neurons” that fire when humans observe and experience emotion. There are also “parts of the brain in the medial prefrontal cortex (responsible for higher-level kinds of thought) that show overlap of activation for both self-focused and other-focused thoughts and judgments,” the same article explains.

Some experts believe the other scientific explanation of empathy is in complete opposition to Simulation Theory. It’s Theory of Mind, the ability to “understand what another person is thinking and feeling based on rules for how one should think or feel,” Psychology Today says. This theory suggests that humans can use cognitive thought processes to explain the mental state of others. By developing theories about human behavior, individuals can predict or explain others’ actions, according to this theory.

While there is no clear consensus, it’s likely that empathy involves multiple processes that incorporate both automatic, emotional responses and learned conceptual reasoning. Depending on context and situation, one or both empathetic responses may be triggered.

Cultivating Empathy

Empathy seems to arise over time as part of human development, and it also has roots in evolution. In fact, “Elementary forms of empathy have been observed in our primate relatives, in dogs, and even in rats,” the Greater Good Science Center says. From a developmental perspective, humans begin exhibiting signs of empathy in social interactions during the second and third years of life. According to Jean Decety’s article “The Neurodevelopment of Empathy in Humans ,” “There is compelling evidence that prosocial behaviors such as altruistic helping emerge early in childhood. Infants as young as 12 months of age begin to comfort victims of distress, and 14- to 18-month-old children display spontaneous, unrewarded helping behaviors.”

While both environmental and genetic influences shape a person’s ability to empathize, we tend to have the same level of empathy throughout our lives, with no age-related decline. According to “Empathy Across the Adult Lifespan: Longitudinal and Experience-Sampling Findings,” “Independent of age, empathy was associated with a positive well-being and interaction profile .”

And it’s true that we likely feel empathy due to evolutionary advantage : “Empathy probably evolved in the context of the parental care that characterizes all mammals. Signaling their state through smiling and crying, human infants urge their caregiver to take action … females who responded to their offspring’s needs out-reproduced those who were cold and distant,” according to the Greater Good Science Center. This may explain gender differences in human empathy.

This suggests we have a natural predisposition to developing empathy. However, social and cultural factors strongly influence where, how, and to whom it is expressed. Empathy is something we develop over time and in relationship to our social environment, finally becoming “such a complex response that it is hard to recognize its origin in simpler responses, such as body mimicry and emotional contagion,” the same source says.

Psychology and Empathy

In the field of psychology, empathy is a central concept. From a mental health perspective, those who have high levels of empathy are more likely to function well in society, reporting “larger social circles and more satisfying relationships,” according to Good Therapy , an online association of mental health professionals. Empathy is vital in building successful interpersonal relationships of all types, in the family unit, workplace, and beyond. Lack of empathy, therefore, is one indication of conditions like antisocial personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder. In addition, for mental health professionals such as therapists, having empathy for clients is an important part of successful treatment. “Therapists who are highly empathetic can help people in treatment face past experiences and obtain a greater understanding of both the experience and feelings surrounding it,” Good Therapy explains.

Exploring Empathy

Empathy plays a crucial role in human, social, and psychological interaction during all stages of life. Consequently, the study of empathy is an ongoing area of major interest for psychologists and neuroscientists in many fields, with new research appearing regularly. Lesley University’s online bachelor’s degree in Psychology gives students the opportunity to study the field of human interaction within the broader spectrum of psychology.

Related Articles & Stories

Read more about our students, faculty, and alumni.

6 Critical Skills for Counselors

Janet Echelman ’97

Becoming a champion for the deaf community.

6 Ways Educators Can Prevent Bullying

‘I Feel Your Pain’: The Neuroscience of Empathy

- Developmental Psychology

- Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Sensory Systems

Whether it’s watching a friend get a paper cut or staring at a photo of a child refugee, observing someone else’s suffering can evoke a deep sense of distress and sadness — almost as if it’s happening to us. In the past, this might have been explained simply as empathy, the ability to experience the feelings of others, but over the last 20 years, neuroscientists have been able to pinpoint some of the specific regions of the brain responsible for this sense of interconnectedness. Five scientists discussed the neuroscience behind how we process the feelings of others during an Integrative Science Symposium chaired by APS Fellow Piotr Winkielman (University of California, San Diego) at the 2017 International Convention of Psychological Science in Vienna.

Mirroring the Mind

Cultural emphasis on ingroups and outgroups may create an “empathy gap” between people of different races and nationalities, says Ying-yi Hong .

“When we witness what happens to others, we don’t just activate the visual cortex like we thought some decades ago,” said Christian Keysers of the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience in Amsterdam. “We also activate our own actions as if we’d be acting in similar ways. We activate our own emotions and sensations as if we felt the same.”

Through his work at the Social Brain Lab, Keysers, together with Valeria Gazzola, has found that observing another person’s action, pain, or affect can trigger parts of the same neural networks responsible for executing those actions and experiencing those feelings firsthand. Keysers’ presentation, however, focused on exploring how this system contributes to our psychology. Does this mirror system help us understand what goes on in others? Does it help us read their minds? Can we “catch” the emotions of others?

To explore whether the motor mirror system helps us understand the inner states behind the actions of others, Keysers in one study asked participants to watch a video of a person grasping toy balls hidden within a large bin. In one condition, participants determined whether or not the person in the video hesitated before selecting a ball (a theory-of-mind task). Using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in combination with fMRI, Keysers showed that interfering with the mirror system impaired people’s ability to detect the level of confidence of others, providing evidence that this system indeed contributes to perceiving the inner states of others. Performing fMRI and TMS on other brain regions such as the temporoparietal junction (TPJ) further suggests that this motor simulation in the mirror system is then sent onward to more cognitive regions in the TPJ.

“Very rapidly, we got this unifying notion that when you witness the states of others you replicate these states in yourself as if you were in their shoes, which is why we call these activities ‘vicarious states,’” Keysers said.

Studies have suggested that this ability to mentalize the experiences of others so vividly can lead us to take prosocial steps to reduce their pain, but Keysers also wanted to investigate the depth of this emotional contagion — how and to what extent we experience other people’s suffering. To do this, Keysers’ lab studied two very different populations: human psychopaths and rats.

While witnessing the pain of others is correlated with activity in the insula, which is thought to contribute to self-awareness by integrating sensory information, and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which is associated with decision making and impulse control, the researchers found that psychopaths who passively observed an aggressor twisting someone’s hand exhibited significantly less brain activity than their neurotypical peers. When the psychopathic individuals were asked to attempt to empathize with the person in the video, however, their brain activity increased to baseline levels.

This suggests that the current model of empathy as a one-dimensional scale with empathic individuals at one end and psychopaths at the other may be overly simplistic, Keysers said.

“Psychopaths are probably equally high on ability, it’s just that they don’t recruit this spontaneously, so their propensity is modified,” he explained.

These findings could lead to more effective interventions for psychopathic individuals, as well as to future research into where people with autism spectrum disorders may fall on these axes.

Shared Pain

Studies of emotional contagion in animal models have allowed researchers to further examine the role of deep brain activity, which can be difficult to neurostimulate in humans. Keysers’ work with rats has found that these animals are more likely to freeze after watching another rat receive an electric shock if they themselves had been shocked in the past.

Inhibiting a region analogous to the ACC in the rats’ brains reduced their response to another rat’s distress, but not their fear of being shocked themselves, suggesting that the area deals specifically with socially triggered fear, Keysers said.

Claus Lamm, University of Vienna, investigates the processes that regulate firsthand pain and those that cause empathy for pain through numerous studies on the influence of painkillers.

In these experiments, participants who took a placebo “painkiller” reported lower pain ratings after receiving a shock than did those in the control group. When those same participants watched a confederate get shocked, they reported a similar drop in their perception of the actor’s pain.

“If you reduce people’s self-experienced pain, if you induce analgesia, that not only helps people to deal with their own pain, but it also reduces empathy for the pain of another person,” Lamm said.

On the neural level, Lamm said, fMRI scans showed that people in the placebo group displayed lower levels of brain activity in the anterior insula and mid cingulate cortex in both cases. These results were further confirmed in another study that compared participants who received only the painkiller placebo with those who received both the placebo and naltrexone, an opioid antagonist that prevents the brain from regulating pain.

This resulted in a “complete reversal” of the placebo effect, causing participants to report both their own pain and the pain of others at near baseline rates, supporting Lamm’s previous claims about the pain system’s role in empathy.

“This suggests that empathy for pain is grounded in representing others’ pain within one’s own pain systems,” Lamm said.

The Self/Other Divide

Empathy may not give us a full sense of someone else’s experiences, however. When observers in one of Keysers’ studies were given the opportunity to pay to reduce the severity of the electric shocks a confederate was about to receive, on average participants paid only enough to reduce her pain by 50%.

Lamm studied this self/other distinction through a series of experiments that measured people’s emotional egocentricity bias. To do so, participants were presented with visuo-tactile stimulation that was either congruent or incongruent with that of a partner under fMRI. In an incongruent pair, for example, one participant might be presented with an image of a rose and be touched with something that felt like a rose, while the other was shown a slug and touched with a slimy substance.

Participants’ own emotions were found to color their perception of other people’s affect at a relatively low rate — however, when researchers inhibited the right supramarginal gyrus (rSMG), a region of the brain previous associated mainly with language processing, this egocentricity bias increased, suggesting that the rSMG may be responsible for maintaining a self/other divide, Lamm said.

“Empathy not only requires a mechanism for sharing emotions, but also for keeping them separate. Otherwise we are getting ‘contaged,’ emotionally distressed and so on,” he said.

The rate of rSMG activation also changes significantly across a lifetime, Lamm added, with the area’s developmental trajectory causing emotional egocentricity to be more common in adolescents and the elderly.

Developing Division

Researchers are working to unite neuroscientific and psychological perspectives on feelings, empathy, and identity, says Piotr Winkielman .

Rebecca Saxe (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) said her work with developmental psychology confirms this trend. In one series of experiments, Saxe monitored the brain networks that 3- to 5-year-old children used to consider a character’s mind (the temporoparietal junction, posterior cingulate, and prefrontal cortex) and body (the secondary somatosensory cortex, insula, middle frontal gyrus, and ACC) throughout a short film.

Saxe found that while these brain regions may interact with each other, there were no points of overlap between the mind and body networks’ activities.

“When we’re getting information from the same source and about the same people, we still nevertheless impose a kind of dualism where we alternate between considering what their bodies feel like and the causes of their minds,” Saxe said.

Furthermore, Saxe and her colleagues found that while these networks were more distinct in children who were able to pass an explicit-false-belief task (e.g., if Sally puts her sandwich on a shelf and her friend moves it to the desk, where will she look for it?), the division was present in participants of all ages.

“Most people have treated explicit false belief as if it were the milestone,” Saxe said. “Actually, the false-belief task is just one measure of a much more continuous developmental change as children become increasingly sophisticated in their thinking about other people’s minds.”

Next, Saxe scaled this experiment down to test the theory of mind of infants as young as 6 months, this time measuring their response to children’s facial expressions, outdoor scenes, and visual static. This time period may be key to understanding the neuropsychology of empathy because most of the brain’s cognitive development happens within the first year of life, she explained.

“A baby’s brain is more different from a 3-year-old’s brain than a 3-year-old’s brain is from a 33-year-old’s brain,” Saxe said.

Under fMRI, the infants’ brains were found to have many of the same regional responses that allow adults to distinguish between faces and scenes. Their brains didn’t show any regional preferences for objects and bodies, however.

This level of regional specificity suggests that the Kennard Principle, the theory that infants’ brains possess such resilience and plasticity because the cortex hasn’t specialized yet, may be only partially true. There does appear to be some functional organization of social process, Saxe said, with gradually increasing specialization as the child ages.

Empathy in Action

Brian D. Knutson says analysis of individuals’ brain activity when considering a purchase may be predictive of aggregate market choices.

On the surface, neuroforecasting sounds like a concept that would be right at home in the world of Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report — a science fiction thriller about a society that stops crime before it happens based on the brainwaves of three mutant “precogs” — said APS Fellow Brian D. Knutson (Stanford University), but someday it could play a very real role in the future of economics.

Knutson’s research on the brain mechanisms that influence choice homes in on three functional targets: the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) for gain anticipation, the anterior insula for loss anticipation, and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) for value integration.

Using fMRI, Knutson was able to predict participants’ purchases in a simulated online shopping environment on the basis of brain activations in these areas. Before participants chose to buy a product, increased activity in the NAcc and mPFC was paired with a decrease in the insula, while the reverse was true of trials in which participants chose not to make a purchase.

“This was very exciting to me as a psychologist to be able to say, ‘Wow, we can take activity out of the brain and, not knowing anything else about who it is and what product they’re seeing, we can predict choice,’” Knutson said.

His economist colleagues weren’t as impressed: They were interested in market activity, not individual choice. Knutson said he accepted this challenge by applying his neuroanaylsis to large-scale online markets such as Kiva and Kickstarter.

Knutson asked 30 participants to rate the appeal and neediness of loan requests on Kiva and found that posts with photos of people displaying a positive affect were most likely to trigger the increased NAcc activity that caused them to make a purchase — or in this case, a loan. More importantly, the averaged choices of those participants forecasted the loan appeal’s success on the internet. Two similar studies involving Kickstarter campaigns also suggested a link between NAcc activity and aggregate market activity.

While brain activity doesn’t scale perfectly to aggregate choice, Knutson said, some components of decision making, such as affective responses, may be more generalizable than others.

“The paradox may be that the things that make you most consistent as an individual, that best predict your choices, may not be the things that make your choices conform to those of others. We may be able to deconstruct and decouple those components in the brain,” Knutson said.

Global Empathy

The neuroanatomy of our brains may allow us to feel empathy for another’s experiences, but it can also stop us from making cross-cultural connections, said APS Fellow Ying-yi Hong (Chinese University of Hong Kong).

“Despite all these neurobiological capabilities enabling us to empathize with others, we still see cases in which individuals chose to harm others, for example during intergroup conflicts or wars,” Hong said.

This may be due in part to the brain’s distinction between in-group and out-group members, she explained. People have been found to show greater activation in the amygdala when viewing fearful faces of their own race, for example, and less activation in the ACC when watching a needle prick the face of someone of a different race.

The cultural mixing that accompanies globalization can heighten these responses, Hong added. In one study, she and her colleagues found that melding cultural symbols (e.g., combining the American and Chinese flags, putting Chairman Mao’s head on the Lincoln Memorial, or even presenting images of “fusion” foods) can elicit a pattern of disgust in the anterior insula of White Americans similar to that elicited by physical contaminant objects such as insects.

These responses can also be modulated by cultural practices, Hong said. One study comparing the in-group/out-group bias in Korea, a more collectivist society, and the United States, a more individualistic society, found that more interdependent societies may foster a greater sense of in-group favoritism in the brain.

Further research into this empathy gap should consider not just the causal relationship between neural activation and behavior, she said, but the societal context in which they take place.

“What I want to propose,” Hong said, “is that maybe there is another area that we can also think about, which is the culture, the shared lay theories, values, and norms.”

There is some fantastic research going on in empathy. From an evolutionary point of view however it’s important to distinguish an evolved motivation system from a competency. Empathy is a competency not a motivation. Empathy can be used for both benevolent but also malevolent motives. And psychopaths have a competency for empathy but what they lack is mammalian caring motivation. Insofar as part of the reproductive strategy of the psychopath is to exploit others and even threaten them then having a brain that turns off distress to the suffering they cause would be an advantage to them. Psychopaths are much more likely to be prepared to harm others to get what they want. Mammalian caring motivation, when guided by higher cognitive processes and human empathy gives rise to compassion. Without empathy compassion would be tricky but without compassion you can still have empathic competencies

Gilbert, P. (2017). Compassion as a social mentality: An evolutionary approach. In: P. Gilbert (ed). Compassion: Concepts, Research and Applications. (p. 31-68). London: Routledge

Gilbert. P. (2015). The evolution and social dynamics of compassion Journal of Social & Personality Psychology Compass, 9, 239–254. DOI: 10.1111/spc3.12176

Catarino, F., Gilbert, P., McEwan., K & Baião, R. (2014). Compassion motivations: Distinguishing submissive compassion from genuine compassion and its association with shame, submissive behaviour, depression, anxiety and stress Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33, 399-412.

Gilbert, P., Catarino, F., Sousa, J., Ceresatto, L., Moore, R., & Basran, J. (2017). Measuring competitive self-focus perspective taking, submissive compassion and compassion goals. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1), 5

Very interesting article. The research behind what links our empathy to our actions determining the agenda is fascinating. As social creatures, we seem to inhibit empathetic tendencies naturally in our genetic makeup when studied. Since we have the highest empathetic behavior compared to other animals, who also show empathetic behavior, I wonder if it falls more on our social norms. What we consider relatable is worthy of our empathy. If we don’t relate, we may be less inclined to put ourselves in the other position.

I have what I call empathy pain. It radiates an aching pain in my legs and I can barely stand it. I’ve googled it in attempts to validate it is real. It seems people either do not believe me or can’t understand stand when I tell them it makes my legs ache. Seeing someone’s cuts, surgical incisions, bloody wounds. I can’t describe all the triggers, but I can 100% say the pain I feel in response is intense, even when they say “oh, it didn’t hurt” or “it’s not hurting”. Well, it hurt ME seeing it.

I am currently writing a literature review for my psychology course in University, based on what I am writing about I believe you may have Mirror Touch Synesthesia. This condition is characterized by viewing others being touched and feeling tactile sensations, and this seems quite similar to what you shared. I would recommend doing a bit of research on MTS, and see if it relates to you.

Since I was 7 years old I felt others pain Then I thought everyone could . I came to realize I feel so much more than most . I feel what I see, I feel what I hear. My sensitive to touch is more like pain but my pain level is very high, I can take a lot of pain.

What about feeling pain or illness without observing it or even having knowledge of someone else’s pain? Such as the phenomenon of twins. I’m looking for research of this outside of the twin sibling relationship.

When carrying out functional mapping of the amygdala cortex by means of electrical stimulation in one of my patients with focal epileptic seizures who was being evaluated for resective epilepsy surgery of the orbitofrontal, opercular, and anterior insular cortex the stimulation caused the patient to reminisce over video films he had seen of cartoons (animaniacs) as a child, at the same time empathizing with the suffering of those characters. I had probably activated a limbic pathway connected to the limen insulae where I was administering electrical stimulation at that time. The visual imagery stopped as soon as the stimulus train was over but the patient still empathized with the cartoon characters for about 20 seconds after the stimulation was over and reported his feelings to me.

Wow… I thought I was alone in the way I feel everyone’s pain and joy. I find that I can not watch scenes of torture or violence on tv, thus I hate most movies, unless it’s a children flick. I get pulled into every story I read. On 911 I thought my heart really was breaking, it consumed my entire body. I can’t watch history shows of Pearl Harbor, or nazis. If I do, sometimes those images stay with me for years and come back as nightmares. It’s not easy living with this in today’s world.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

Scientists Discuss How to Study the Psychology of Collectives, Not Just Individuals

In a set of articles appearing in Perspectives on Psychological Science, an international array of scientists discusses how the study of neighborhoods, work units, activist groups, and other collectives can help us better understand and respond to societal changes.

Artificial Intelligence: Your Thoughts and Concerns

APS members weigh in on the biggest opportunities and/or ethical challenges involving AI within the field of psychological science. Will we witness vast and constructive cross-fertilization—or “a dystopian cyberpunk corporation-led hellscape”?

Hearing is Believing: Sounds Can Alter Our Visual Perception

Audio cues can not only help us to recognize objects more quickly but can even alter our visual perception. That is, pair birdsong with a bird and we see a bird—but replace that birdsong with a squirrel’s chatter, and we’re not quite so sure what we’re looking at.

Privacy Overview

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Empathy articles from across Nature Portfolio

Empathy is a social process by which a person has an understanding and awareness of another's emotions and/or behaviour, and can often lead to a person experiencing the same emotions. It differs from sympathy, which involves concern for others without sharing the same emotions as them.

Latest Research and Reviews

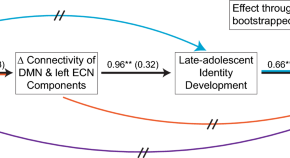

Diverse adolescents’ transcendent thinking predicts young adult psychosocial outcomes via brain network development

- Rebecca J. M. Gotlieb

- Xiao-Fei Yang

- Mary Helen Immordino-Yang

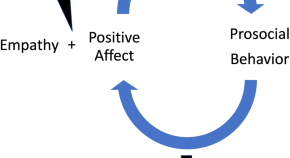

The effect of psilocybin on empathy and prosocial behavior: a proposed mechanism for enduring antidepressant effects

- Kush V. Bhatt

- Cory R. Weissman

A distinct cortical code for socially learned threat

Studies in mice show that observational fear learning is encoded by neurons in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in a manner that is distinct from the encoding of fear learned by direct experience.

- Shana E. Silverstein

- Ruairi O’Sullivan

- Andrew Holmes

Cortical regulation of helping behaviour towards others in pain

A study describes the role of the anterior cingulate cortex in coding and regulating helping behaviour exhibited by mice towards others experiencing pain.

- Mingmin Zhang

- Ye Emily Wu

- Weizhe Hong

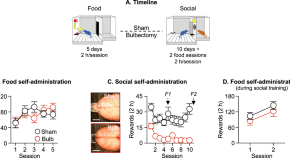

Social odor choice buffers drug craving

- Kimberly M. Papastrat

- Cody A. Lis

- Marco Venniro

Nucleus accumbens core single cell ensembles bidirectionally respond to experienced versus observed aversive events

- Oyku Dinckol

- Noah Harris Wenger

- Munir Gunes Kutlu

News and Comment

Natural primate neurobiology.

A new study captures nearly the full repertoire of primate natural behaviour and reveals that highly distributed cortical activity maintains multifaceted dynamic social relationships.

- Jake Rogers

Your pain in my brain

- Helena Hartmann

Comforting in mice

- Sachin Ranade

Feeling another’s pain

Projections from the anterior cingulate cortex to the nucleus accumbens are required for the social transfer of pain or analgesia in mice.

- Darran Yates

Taking action: empathy and social interaction in rats

- Sam A. Golden

Stress and sociability

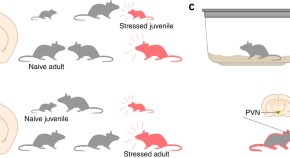

Humans and animals can react to the affective state of others in distress. However, exposure to a stressed partner can trigger stress-related adaptations. Two studies shed light on the mechanisms underlying the behavioral responses toward stressed individuals and on the synaptic changes associated with social transmission of stress.

- Dana Rubi Levy

- Ofer Yizhar

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

How to build empathy in research

Brenda Reginatto

Sunetra Bane

Dr Susie Donnelly

About this video

Empathy can help researchers better understand people’s behaviours, values and needs. Through asking effective questions, a researcher can build empathy with research participants.

In this webinar, our experts explain why empathy is important in research and focus on three tools for building empathy in research: interviewing, journey mapping and Photovoice. Also, they discuss ways of adapting these tools across sectors; including academia, industry and clinical settings.

After this webinar, you will learn practical tips on how to ask effective questions for building empathy with research participants, how to leverage journey-maps to understand workflows and stories, identify gaps and needs, and encourage participatory research. Also, you will understand how the use of Photovoice as a methodological tool can promote empathy among policymakers and other stakeholders.

About the presenters

Independent Consultant to digital health companies in Boston, USA.

Brenda is a gerontologist with expertise in human-centered design and healthcare innovation. Brenda has led user research teams at University College Dublin (Ireland) and Partners Healthcare (USA), where she worked with companies, ranging from early stage start-ups to large multinationals, to bring the voice of the user to the design and development of their digital health products. After obtaining her MSc from King’s College London in 2012, Brenda became interested in the application of human-centred design to create better products and services for older adults. She is currently working as an independent consultant to digital health companies in Boston, USA.

Independent UX consultant with innovation labs and start-ups.

Sunetra is a user-experience researcher and strategist with experience in human-centered design and design thinking for product and service design. She also has a background in global public health in the US and Indian context, earning her MPH from Boston University’s School of Public Health in 2015.

During her time at Partners Healthcare, Sunetra leveraged both those elements of her background, education and experience to lead design projects focused on improving health outcomes and the human journey with illness and wellness. She is interested in bridging the gap between academic and applied user research for product and service design in healthcare. Sunetra is now based in Pune, India, working as an independent UX consultant with innovation labs and start-ups.

Postdoctoral researcher with the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Systems and the Centre for Arthritis Research in University College Dublin.

Susie is a postdoctoral researcher with the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Systems and the Centre for Arthritis Research in University College Dublin. She joined these teams in 2018 under a Wellcome Trust Medical Humanities and Social Science Collaborative grant to conduct participatory action research with a community of people living with the chronic and invisible illness, rheumatoid arthritis. Building on her background in journalism (BA) and sociology (HDip, MSocSc, PhD), she began to explore innovative participatory methods such as photovoice upon joining the research team at the Centre for Applied Research in Connected Health as ethnographer in 2017.

Susie’s research career reflects her diverse interests in methodology, communications, power and inequality. She has peer-reviewed publications in the Journal of Medical Internet Research , the Irish Journal of Sociology , and the Journal of Contemporary Religion among others

Standing up for Science

How to write a lay summary

How to create impact with patient and public involvement

How your research can make an impact on society

Life after publication: How to promote your work for maximum impact

Empathy slides.

Brenda Reginatto on Twitter

Brenda Reginatto on LinkedIn

Sunetra Bane on LinkedIn

Susie Donnelly on Twitter

Susie Donnelly on LinkedIn

Follow Researcher Academy on Twitter

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Empathy Defined

What is empathy.

The term “empathy” is used to describe a wide range of experiences. Emotion researchers generally define empathy as the ability to sense other people’s emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling.

Contemporary researchers often differentiate between two types of empathy : “Affective empathy” refers to the sensations and feelings we get in response to others’ emotions; this can include mirroring what that person is feeling, or just feeling stressed when we detect another’s fear or anxiety. “Cognitive empathy,” sometimes called “perspective taking,” refers to our ability to identify and understand other people’s emotions. Studies suggest that people with autism spectrum disorders have a hard time empathizing .

Empathy seems to have deep roots in our brains and bodies, and in our evolutionary history . Elementary forms of empathy have been observed in our primate relatives , in dogs , and even in rats . Empathy has been associated with two different pathways in the brain, and scientists have speculated that some aspects of empathy can be traced to mirror neurons , cells in the brain that fire when we observe someone else perform an action in much the same way that they would fire if we performed that action ourselves. Research has also uncovered evidence of a genetic basis to empathy , though studies suggest that people can enhance (or restrict) their natural empathic abilities.

Having empathy doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll want to help someone in need, though it’s often a vital first step toward compassionate action.

For more: Read Frans de Waal’s essay on “ The Evolution of Empathy ” and Daniel Goleman’s overview of different forms of empathy , drawing on the work of Paul Ekman.

What are the Limitations?

When Empathy Hurts, Compassion Can Heal

A new neuroscientific study shows that compassion training can help us cope with other…

Does Empathy Reduce Prejudice—or Promote It?

Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton explains how to make sense of conflicting scientific evidence.

How to Avoid the Empathy Trap

Do you prioritize other people's feelings over your own? You might be falling into the…

Featured Articles

Who Finds Joy in Other People’s Joy?

Who feels good when a good thing happens for someone else? Our GGSC sympathetic joy quiz results suggest it has almost nothing to do with money or…

How Accurate Are Media Portrayals of Foster Families?

Movies and TV often paint the youth foster system in a negative light. But do people who went through the system agree?

Can Artificial Intelligence Help Human Mental Health?

A conversation with UC Berkeley School of Public Health professor Jodi Halpern about AI ethics, empathy, and mental health.

The Best Greater Good Articles of 2023

We round up the most-read and highly rated Greater Good articles from the past year.

Our Favorite Books of 2023

Greater Good’s editors pick the most thought-provoking, practical, and inspirational science books of the year.

Is It Actually Helpful to Talk About Toxic Masculinity?

Research suggests that men are changing their behavior in positive ways, including around emotions.

Why Practice It?

Empathy is a building block of morality—for people to follow the Golden Rule, it helps if they can put themselves in someone else’s shoes. It is also a key ingredient of successful relationships because it helps us understand the perspectives, needs, and intentions of others. Here are some of the ways that research has testified to the far-reaching importance of empathy.

- Seminal studies by Daniel Batson and Nancy Eisenberg have shown that people higher in empathy are more likely to help others in need, even when doing so cuts against their self-interest .

- Empathy is contagious : When group norms encourage empathy, people are more likely to be empathic—and more altruistic.

- Empathy reduces prejudice and racism : In one study, white participants made to empathize with an African American man demonstrated less racial bias afterward.

- Empathy is good for your marriage : Research suggests being able to understand your partner’s emotions deepens intimacy and boosts relationship satisfaction ; it’s also fundamental to resolving conflicts. (The GGSC’s Christine Carter has written about effective strategies for developing and expressing empathy in relationships .)

- Empathy reduces bullying: Studies of Mary Gordon’s innovative Roots of Empathy program have found that it decreases bullying and aggression among kids, and makes them kinder and more inclusive toward their peers. An unrelated study found that bullies lack “affective empathy” but not cognitive empathy, suggesting that they know how their victims feel but lack the kind of empathy that would deter them from hurting others.

- Empathy reduces suspensions : In one study, students of teachers who participated in an empathy training program were half as likely to be suspended, compared to students of teachers who didn’t participate.

- Empathy promotes heroic acts: A seminal study by Samuel and Pearl Oliner found that people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust had been encouraged at a young age to take the perspectives of others.

- Empathy fights inequality. As Robert Reich and Arlie Hochschild have argued, empathy encourages us to reach out and want to help people who are not in our social group, even those who belong to stigmatized groups , like the poor. Conversely, research suggests that inequality can reduce empathy : People show less empathy when they attain higher socioeconomic status.

- Empathy is good for the office: Managers who demonstrate empathy have employees who are sick less often and report greater happiness.

- Empathy is good for health care: A large-scale study found that doctors high in empathy have patients who enjoy better health ; other research suggests training doctors to be more empathic improves patient satisfaction and the doctors’ own emotional well-being .

- Empathy is good for police: Research suggests that empathy can help police officers increase their confidence in handling crises, diffuse crises with less physical force, and feel less distant from the people they’re dealing with.

For more: Learn about why we should teach empathy to preschoolers .

How Do I Cultivate It?

Humans experience affective empathy from infancy, physically sensing their caregivers’ emotions and often mirroring those emotions. Cognitive empathy emerges later in development, around three to four years of age , roughly when children start to develop an elementary “ theory of mind ”—that is, the understanding that other people experience the world differently than they do.

From these early forms of empathy, research suggests we can develop more complex forms that go a long way toward improving our relationships and the world around us. Here are some specific, science-based activities for cultivating empathy from our site Greater Good in Action :

- Active listening: Express active interest in what the other person has to say and make him or her feel heard.

- Shared identity: Think of a person who seems to be very different from you, and then list what you have in common.

- Put a human face on suffering: When reading the news, look for profiles of specific individuals and try to imagine what their lives have been like.

- Eliciting altruism: Create reminders of connectedness.

And here are some of the keys that researchers have identified for nurturing empathy in ourselves and others:

- Focus your attention outwards: Being mindfully aware of your surroundings, especially the behaviors and expressions of other people , is crucial for empathy. Indeed, research suggests practicing mindfulness helps us take the perspectives of other people yet not feel overwhelmed when we encounter their negative emotions.

- Get out of your own head: Research shows we can increase our own level of empathy by actively imagining what someone else might be experiencing.

- Don’t jump to conclusions about others: We feel less empathy when we assume that people suffering are somehow getting what they deserve .

- Show empathic body language : Empathy is expressed not just by what we say, but by our facial expressions, posture, tone of voice, and eye contact (or lack thereof).

- Meditate: Neuroscience research by Richard Davidson and his colleagues suggests that meditation—specifically loving-kindness meditation, which focuses attention on concern for others—might increase the capacity for empathy among short-term and long-term meditators alike (though especially among long-time meditators).

- Explore imaginary worlds: Research by Keith Oatley and colleagues has found that people who read fiction are more attuned to others’ emotions and intentions.

- Join the band: Recent studies have shown that playing music together boosts empathy in kids.

- Play games : Neuroscience research suggests that when we compete against others, our brains are making a “ mental model ” of the other person’s thoughts and intentions.

- Take lessons from babies: Mary Gordon’s Roots of Empathy program is designed to boost empathy by bringing babies into classrooms, stimulating children’s basic instincts to resonate with others’ emotions.

- Combat inequality: Research has shown that attaining higher socioeconomic status diminishes empathy , perhaps because people of high SES have less of a need to connect with, rely on, or cooperate with others. As the gap widens between the haves and have-nots, we risk facing an empathy gap as well. This doesn’t mean money is evil, but if you have a lot of it, you might need to be more intentional about maintaining your own empathy toward others.

- Pay attention to faces: Pioneering research by Paul Ekman has found we can improve our ability to identify other people’s emotions by systematically studying facial expressions. Take our Emotional Intelligence Quiz for a primer, or check out Ekman’s F.A.C.E. program for more rigorous training.

- Believe that empathy can be learned : People who think their empathy levels are changeable put more effort into being empathic, listening to others, and helping, even when it’s challenging.

For more : The Ashoka Foundation’s Start Empathy initiative tracks educators’ best practices for teaching empathy . The initiative gave awards to 14 programs judged to do the best job at educating for empathy . The nonprofit Playworks also offers eight strategies for developing empathy in children .

What Are the Pitfalls and Limitations of Empathy?

According to research , we’re more likely to help a single sufferer than a large group of faceless victims, and we empathize more with in-group members than out-group members . Does this reflect a defect in empathy itself? Some critics believe so , while others argue that the real problem is how we suppress our own empathy .

Empathy, after all, can be painful. An “ empathy trap ” occurs when we’re so focused on feeling what others are feeling that we neglect our own emotions and needs—and other people can take advantage of this. Doctors and caregivers are at particular risk of feeling emotionally overwhelmed by empathy.

In other cases, empathy seems to be detrimental. Empathizing with out-groups can make us more reluctant to engage with them, if we imagine that they’ll be critical of us. Sociopaths could use cognitive empathy to help them exploit or even torture people.

Even if we are well-intentioned, we tend to overestimate our empathic skills. We may think we know the whole story about other people when we’re actually making biased judgments—which can lead to misunderstandings and exacerbate prejudice.

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Empathy?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Bailey Mariner

Empathy is the ability to emotionally understand what other people feel, see things from their point of view, and imagine yourself in their place. Essentially, it is putting yourself in someone else's position and feeling what they are feeling.

Empathy means that when you see another person suffering, such as after they've lost a loved one , you are able to instantly envision yourself going through that same experience and feel what they are going through.

While people can be well-attuned to their own feelings and emotions, getting into someone else's head can be a bit more difficult. The ability to feel empathy allows people to "walk a mile in another's shoes," so to speak. It permits people to understand the emotions that others are feeling.

Press Play for Advice on Empathy

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , featuring empathy expert Dr. Kelsey Crowe, shares how you can show empathy to someone who is going through a hard time. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Signs of Empathy

For many, seeing another person in pain and responding with indifference or even outright hostility seems utterly incomprehensible. But the fact that some people do respond in such a way clearly demonstrates that empathy is not necessarily a universal response to the suffering of others.

If you are wondering whether you are an empathetic person, here are some signs that show that you have this tendency:

- You are good at really listening to what others have to say.

- People often tell you about their problems.

- You are good at picking up on how other people are feeling.

- You often think about how other people feel.

- Other people come to you for advice.

- You often feel overwhelmed by tragic events.

- You try to help others who are suffering.

- You are good at telling when people aren't being honest .

- You sometimes feel drained or overwhelmed in social situations.

- You care deeply about other people.

- You find it difficult to set boundaries in your relationships.

Types of Empathy

There are several types of empathy that a person may experience. The three types of empathy are:

- Affective empathy involves the ability to understand another person's emotions and respond appropriately. Such emotional understanding may lead to someone feeling concerned for another person's well-being, or it may lead to feelings of personal distress.

- Somatic empathy involves having a physical reaction in response to what someone else is experiencing. People sometimes physically experience what another person is feeling. When you see someone else feeling embarrassed, for example, you might start to blush or have an upset stomach.

- Cognitive empathy involves being able to understand another person's mental state and what they might be thinking in response to the situation. This is related to what psychologists refer to as the theory of mind or thinking about what other people are thinking.

Empathy vs. Sympathy vs. Compassion

While sympathy and compassion are related to empathy, there are important differences. Compassion and sympathy are often thought to be more of a passive connection, while empathy generally involves a much more active attempt to understand another person.

Uses for Empathy

Being able to experience empathy has many beneficial uses.

- Empathy allows you to build social connections with others . By understanding what people are thinking and feeling, you are able to respond appropriately in social situations. Research has shown that having social connections is important for both physical and psychological well-being.

- Empathizing with others helps you learn to regulate your own emotions . Emotional regulation is important in that it allows you to manage what you are feeling, even in times of great stress, without becoming overwhelmed.

- Empathy promotes helping behaviors . Not only are you more likely to engage in helpful behaviors when you feel empathy for other people, but other people are also more likely to help you when they experience empathy.

Potential Pitfalls of Empathy

Having a great deal of empathy makes you concerned for the well-being and happiness of others. It also means, however, that you can sometimes get overwhelmed, burned out , or even overstimulated from always thinking about other people's emotions. This can lead to empathy fatigue.

Empathy fatigue refers to the exhaustion you might feel both emotionally and physically after repeatedly being exposed to stressful or traumatic events . You might also feel numb or powerless, isolate yourself, and have a lack of energy.

Empathy fatigue is a concern in certain situations, such as when acting as a caregiver . Studies also show that if healthcare workers can't balance their feelings of empathy (affective empathy, in particular), it can result in compassion fatigue as well.

Other research has linked higher levels of empathy with a tendency toward emotional negativity , potentially increasing your risk of empathic distress. It can even affect your judgment, causing you to go against your morals based on the empathy you feel for someone else.

Impact of Empathy

Your ability to experience empathy can impact your relationships. Studies involving siblings have found that when empathy is high, siblings have less conflict and more warmth toward each other. In romantic relationships, having empathy increases your ability to extend forgiveness .

Not everyone experiences empathy in every situation. Some people may be more naturally empathetic in general, but people also tend to feel more empathetic toward some people and less so toward others. Some of the factors that play a role in this tendency include:

- How you perceive the other person

- How you attribute the other individual's behaviors

- What you blame for the other person's predicament

- Your past experiences and expectations

Research has found that there are gender differences in the experience and expression of empathy, although these findings are somewhat mixed. Women score higher on empathy tests, and studies suggest that women tend to feel more cognitive empathy than men.

At the most basic level, there appear to be two main factors that contribute to the ability to experience empathy: genetics and socialization. Essentially, it boils down to the age-old relative contributions of nature and nurture .

Parents pass down genes that contribute to overall personality, including the propensity toward sympathy, empathy, and compassion. On the other hand, people are also socialized by their parents, peers, communities, and society. How people treat others, as well as how they feel about others, is often a reflection of the beliefs and values that were instilled at a very young age.

Barriers to Empathy

Some people lack empathy and, therefore, aren't able to understand what another person may be experiencing or feeling. This can result in behaviors that seem uncaring or sometimes even hurtful. For instance, people with low affective empathy have higher rates of cyberbullying .

A lack of empathy is also one of the defining characteristics of narcissistic personality disorder . Though, it is unclear whether this is due to a person with this disorder having no empathy at all or having more of a dysfunctional response to others.

A few reasons why people sometimes lack empathy include cognitive biases, dehumanization, and victim-blaming.

Cognitive Biases

Sometimes the way people perceive the world around them is influenced by cognitive biases . For example, people often attribute other people's failures to internal characteristics, while blaming their own shortcomings on external factors.

These biases can make it difficult to see all the factors that contribute to a situation. They also make it less likely that people will be able to see a situation from the perspective of another.

Dehumanization

Many also fall victim to the trap of thinking that people who are different from them don't feel and behave the same as they do. This is particularly common in cases when other people are physically distant.

For example, when they watch reports of a disaster or conflict in a foreign land, people might be less likely to feel empathy if they think that those who are suffering are fundamentally different from themselves.

Victim Blaming

Sometimes, when another person has suffered a terrible experience, people make the mistake of blaming the victim for their circumstances. This is the reason that victims of crimes are often asked what they might have done differently to prevent the crime.

This tendency stems from the need to believe that the world is a fair and just place. It is the desire to believe that people get what they deserve and deserve what they get—and it can fool you into thinking that such terrible things could never happen to you.

Causes of Empathy

Human beings are certainly capable of selfish, even cruel, behavior. A quick scan of the news quickly reveals numerous unkind, selfish, and heinous actions. The question, then, is why don't we all engage in such self-serving behavior all the time? What is it that causes us to feel another's pain and respond with kindness ?

The term empathy was first introduced in 1909 by psychologist Edward B. Titchener as a translation of the German term einfühlung (meaning "feeling into"). Several different theories have been proposed to explain empathy.

Neuroscientific Explanations

Studies have shown that specific areas of the brain play a role in how empathy is experienced. More recent approaches focus on the cognitive and neurological processes that lie behind empathy. Researchers have found that different regions of the brain play an important role in empathy, including the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula.

Research suggests that there are important neurobiological components to the experience of empathy. The activation of mirror neurons in the brain plays a part in the ability to mirror and mimic the emotional responses that people would feel if they were in similar situations.

Functional MRI research also indicates that an area of the brain known as the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) plays a critical role in the experience of empathy. Studies have found that people who have damage to this area of the brain often have difficulty recognizing emotions conveyed through facial expressions .

Emotional Explanations

Some of the earliest explorations into the topic of empathy centered on how feeling what others feel allows people to have a variety of emotional experiences. The philosopher Adam Smith suggested that it allows us to experience things that we might never otherwise be able to fully feel.

This can involve feeling empathy for both real people and imaginary characters. Experiencing empathy for fictional characters, for example, allows people to have a range of emotional experiences that might otherwise be impossible.

Prosocial Explanations

Sociologist Herbert Spencer proposed that empathy served an adaptive function and aided in the survival of the species. Empathy leads to helping behavior, which benefits social relationships. Humans are naturally social creatures. Things that aid in our relationships with other people benefit us as well.

When people experience empathy, they are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors that benefit other people. Things such as altruism and heroism are also connected to feeling empathy for others.

Tips for Practicing Empathy

Fortunately, empathy is a skill that you can learn and strengthen. If you would like to build your empathy skills, there are a few things that you can do:

- Work on listening to people without interrupting

- Pay attention to body language and other types of nonverbal communication

- Try to understand people, even when you don't agree with them

- Ask people questions to learn more about them and their lives

- Imagine yourself in another person's shoes

- Strengthen your connection with others to learn more about how they feel

- Seek to identify biases you may have and how they affect your empathy for others

- Look for ways in which you are similar to others versus focusing on differences

- Be willing to be vulnerable, opening up about how you feel

- Engage in new experiences, giving you better insight into how others in that situation may feel

- Get involved in organizations that push for social change

A Word From Verywell

While empathy might be lacking in some, most people are able to empathize with others in a variety of situations. This ability to see things from another person's perspective and empathize with another's emotions plays an important role in our social lives. Empathy allows us to understand others and, quite often, compels us to take action to relieve another person's suffering.

Reblin M, Uchino BN. Social and emotional support and its implication for health . Curr Opin Psychiatry . 2008;21(2):201‐205. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f3ad89

Cleveland Clinic. Empathy fatigue: How stress and trauma can take a toll on you .

Duarte J, Pinto-Bouveia J, Cruz B. Relationships between nurses' empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study . Int J Nursing Stud . 2016;60:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015

Chikovani G, Babuadze L, Iashvili N, Gvalia T, Surguladze S. Empathy costs: Negative emotional bias in high empathisers . Psychiatry Res . 2015;229(1-2):340-346. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.001

Lam CB, Solmeyer AR, McHale SM. Sibling relationships and empathy across the transition to adolescence . J Youth Adolescen . 2012;41:1657-1670. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9781-8

Kimmes JG, Durtschi JA. Forgiveness in romantic relationships: The roles of attachment, empathy, and attributions . J Marital Family Ther . 2016;42(4):645-658. doi:10.1111/jmft.12171

Kret ME, De Gelder B. A review on sex difference in processing emotional signals . Neuropsychologia . 2012; 50(7):1211-1221. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.022

Schultze-Krumbholz A, Scheithauer H. Is cyberbullying related to lack of empathy and social-emotional problems? Int J Develop Sci . 2013;7(3-4):161-166. doi:10.3233/DEV-130124

Baskin-Sommers A, Krusemark E, Ronningstam E. Empathy in narcissistic personality disorder: From clinical and empirical perspectives . Personal Dis Theory Res Treat . 2014;5(3):323-333. doi:10.1037/per0000061

Decety, J. Dissecting the neural mechanisms mediating empathy . Emotion Review . 2011; 3(1): 92-108. doi:10.1177/1754073910374662

Shamay-Tsoory SG, Aharon-Peretz J, Perry D. Two systems for empathy: A double dissociation between emotional and cognitive empathy in inferior frontal gyrus versus ventromedial prefrontal lesions . Brain . 2009;132(PT3): 617-627. doi:10.1093/brain/awn279

Hillis AE. Inability to empathize: Brain lesions that disrupt sharing and understanding another's emotions . Brain . 2014;137(4):981-997. doi:10.1093/brain/awt317

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Is Empathy the Key to Effective Teaching? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Teacher-Student Interactions and Student Outcomes

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 10 March 2022

- Volume 34 , pages 1177–1216, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Karen Aldrup ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1567-5724 1 ,

- Bastian Carstensen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5259-9578 1 &

- Uta Klusmann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8656-344X 1

32k Accesses

26 Citations

50 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

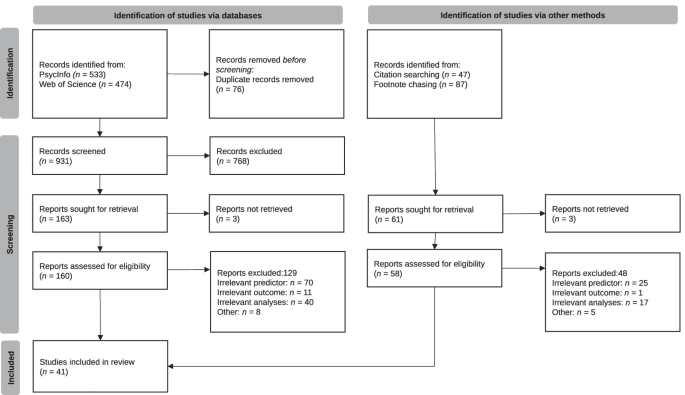

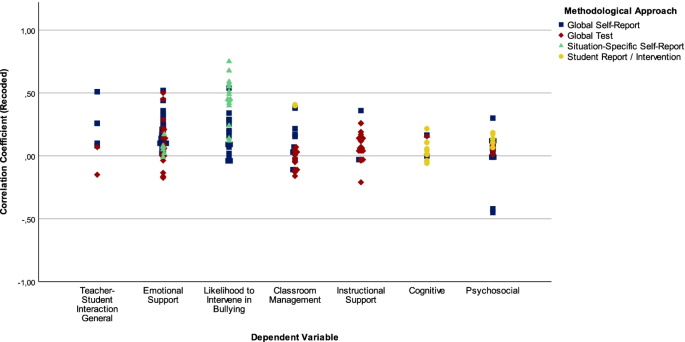

Teachers’ social-emotional competence has received increasing attention in educational psychology for about a decade and has been suggested to be an important prerequisite for the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. In this review, we will summarize the current state of knowledge about the association between one central component of teachers’ social-emotional competence—their empathy—with these indicators of teaching effectiveness. After all, empathy appears to be a particularly promising determinant for explaining high-quality teacher-student interactions, especially emotional support for students and, in turn, positive student development from a theoretical perspective. A systematic literature research yielded 41 records relevant for our article. Results indicated that teachers reporting more empathy with victims of bullying in hypothetical scenarios indicated a greater likelihood to intervene. However, there was neither consistent evidence for a relationship between teachers’ empathy and the degree to which they supported students emotionally in general, nor with classroom management, instructional support, or student outcomes. Notably, most studies asked teachers for a self-evaluation of their empathy, whereas assessments based on objective criteria were underrepresented. We discuss how these methodological decisions limit the conclusions we can draw from prior studies and outline perspective for future research in teachers’ empathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

A world beyond self: empathy and pedagogy during times of global crisis

Eliza Gates & Jen Scott Curwood

Effects of Empathy-based Learning in Elementary Social Studies

June Lee, Yunoug Lee & Mi Hwa Kim

Towards a Pedagogy of Empathy

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Students experience a range of emotions—such as enjoyment, anxiety, and boredom—while they attain new knowledge, take exams, or strive to connect with their classmates (Ahmed et al., 2010 ; Hascher, 2008 ; Martin & Huebner, 2007 ; Pekrun et al., 2002 ). Teachers are confronted with these emotions in the classroom and beyond, and their ability to read their students’ emotional signals and attend to them sensitively is vital to form positive teacher-student relationships (Pianta, 1999 ). Therefore, teachers’ social-emotional characteristics have been suggested as essential for the quality of teacher-student interactions and, in turn, students’ psychosocial outcomes (Brackett & Katulak, 2007 ; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009 ; Rimm-Kaufman & Hamre, 2010 ). Empathy is one component of teachers’ social-emotional characteristics that appears particularly relevant for the quality of teacher-student interactions from a theoretical perspective. First, empathy is considered as the origin of human’s prosocial behavior (Preston & de Waal, 2002 ). Second, in contrast to social-emotional characteristics such as emotional self-awareness or emotion regulation, empathy explicitly refers to other people rather than to the self, more specifically, to the ability to perceive and understand students’ emotions and needs (Zins et al., 2004 ).

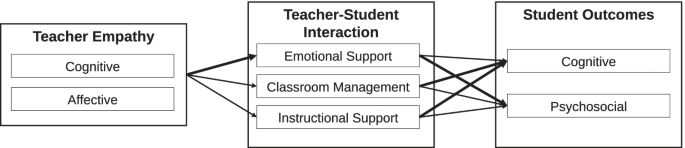

Because of these theoretical arguments and a recent increase in empirical studies on this topic, the goal of this article is to review prior research investigating the relationship of teachers’ empathy with the quality of teacher-student interactions and, in turn, with student outcomes (see heuristic working model in Figure 1 ). We use effective teaching here as an umbrella term to refer to both interaction quality and student outcomes. Summarizing the current level of knowledge on this topic appears particularly useful for the following reasons. First, various meanings have been attached to the term empathy, and the diversity of concepts that have been used to refer to concepts closely related to empathy (e.g., emotional intelligence, perspective taking, and emotion recognition; also see Batson, 2009 ; Olderbak & Wilhelm, 2020 ) make it difficult to oversee prior research at first glance. Second, the research field has rapidly grown throughout the last decade. Thus, to understand foci of prior research and widely neglected questions is important; for example, the review will uncover possible specific underrepresented student outcomes (e.g., cognitive vs. psychosocial). Third, researchers have applied different methodological approaches. For example, self-report scales and objective tests are available and it is debatable whether both are equally valid considering the risk of self-serving bias in questionnaires (Brackett et al., 2006 ). Against this background, it is important to summarize not only the results from prior studies but also the assessment methods they applied to inform future studies in terms of which methodological approaches are best suited to obtain valid results.

Heuristic working model on the role of teachers’ empathy in the quality of teacher-student interactions and student outcomes; paths where we expect the closest associations are in bold (also see Brackett & Katulak, 2007 ; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009 )

A General Theoretical Perspective on Empathy

Historically, two distinct lines of research have evolved around empathy (for an overview see, e.g., Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004 ; Davis, 1983 ). First, from the affective perspective , empathy describes the emotional reactions to another person’s affective experiences. According to Eisenberg and Miller ( 1987 ), this means that one experiences the same emotion as the other person. Hatfield et al. ( 1993 ) described the phenomenon of “catching” other people’s emotions as emotional contagion. Affective empathy can elicit both positive and negative emotions, and because emotions are multi-componential, the subjective feelings, thoughts, expressions, and physiological and behavioral reactions can differ depending on the type of emotion (Olderbak et al., 2014 ; Scherer, 1984 ). Empathy from the affective perspective can also mean to feel something that is appropriate but not identical with the other person’s emotion, for instance, responding with concern and sympathy to another person’s sadness (e.g., Batson et al., 2002 ).

Second, from the cognitive perspective, empathy reflects a person’s ability to understand how other people feel by taking their perspective and reading their nonverbal signals (e.g., Wispé, 1986 ). Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright ( 2004 ) pointed out that theory of mind largely converges with the cognitive definition of empathy. Furthermore, models of emotional intelligence, such as the four-branch-model (Mayer & Salovey, 1997 ), include qualities resembling empathy as defined in the cognitive perspective: the ability to perceive emotions in other people’s faces accurately and to understand emotions, that is, knowing when specific emotions are likely to arise.

In accordance with Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright ( 2004 ), we define empathy as including both affective and cognitive components (for similar approaches, also see Davis, 1983 ; Decety & Jackson, 2004 ; Preston & de Waal, 2002 ). This allows for a more comprehensive understanding of empathy and its consequences because the affective component of empathy explains why we care for other people in need and are motivated to react sensitively, whereas the cognitive component explains what enables people to know and name the feelings of others (Batson, 2009 ). Preston and de Waal ( 2002 ) also support the idea that cognitive and affective empathy are entangled and complement each other in explaining prosocial behavior. They suggest that the development of cognitive empathy promotes the “effectiveness of empathy by helping the subject to focus on the object, even in its absence, remain emotionally distinct from the object, and determine the best course of action for the object’s needs” (Preston & de Waal, 2002 , p. 20).

Considering the central role of empathy in human relationships, which has also been supported empirically (Eisenberg & Miller, 1987 ; Kardos et al., 2017 ; Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015 ; Sened et al., 2017 ; Vachon et al., 2014 ), its importance in social occupations has been recognized for a long time. For instance, Rogers ( 1959 ) proposed that the therapists’ ability to accurately perceive their clients’ point of view will facilitate the therapeutic process and, in turn, produce change in personality and behavior. In line with this assumption, studies with psychotherapists and also with physicians showed that their empathy predicted their patients’ satisfaction and clinical outcomes (Elliott et al., 2018 ; Hojat et al., 2011 ). Like psychotherapists or physicians and their clients, teachers are in close interpersonal contact with their students. Hence, it seems plausible to assume a central role of empathy in their professional lives as well.

The Role of Teacher Empathy

Caring for students and establishing positive teacher-student relationships are a central part of teachers’ professional roles (Butler, 2012 ; O’Connor, 2008 ; Watt et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, providing high levels of emotional support as indicated by a positive emotional tone in the classroom, sensitive responses to students’ emotional, social, and academic needs, and consideration of their interests is one aspect of high-quality classrooms (Pianta & Hamre, 2009 ). To achieve this, the ability to read students’ (non-)verbal signals—in others words: empathy—is vital (Pianta, 1999 ). For instance, teachers’ cognitive empathy will help them better identify from a student’s facial expressions if he or she is sad about a bad grade, angry about an argument with friends, or bored with specific learning activities. Empathic teachers will know that students may feel anxious when confronted with challenging tasks or embarrassed and frustrated when repeatedly unable to answer the teacher’s questions. Having recognized negative affective states in their students, teachers’ affective empathy should motivate them to react sensitively to their students’ emotional needs, provide comfort, and encouragement (Batson, 2009 ; Weisz et al., 2020 ). The prosocial classroom model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009 ) also integrates these ideas and further states that teachers’ social-emotional competence, of which empathy is one part, should facilitate classroom management.