- Search by keyword

- Search by citation

Page 1 of 5

Spatial analysis of outdoor indecent assault risk: a study using ambient population data

Spatiotemporal data on ambient populations have recently become widely available. Although previous studies have indicated a link between the spatial patterns of crime occurrence and ambient population distrib...

- View Full Text

Post-pandemic crime trends in England and Wales

This study of recorded crime trends in England & Wales spans three and a half years, that is, two covid pandemic years from March 2020 and 18 ‘post-pandemic’ months following cessation of covid restrictions...

Gender differences in online abuse: the case of Dutch politicians

Online abuse and threats towards politicians have become a significant concern in the Netherlands, like in many other countries across the world. This paper analyses gender differences in abuse received by Dut...

Online hate speech victimization: consequences for victims’ feelings of insecurity

This paper addresses the question whether and to what extent the experience of online hate speech affects victims’ sense of security. Studies on hate crime in general show that such crimes are associated with ...

Identity fraud victimization: a critical review of the literature of the past two decades

This study aims to provide an understanding of the nature, extent, and quality of the research evidence on identity fraud victimization in the US. Specifically, this article reviews, summarizes, and comments o...

Text mining domestic violence police narratives to identify behaviours linked to coercive control

Domestic and family violence (DFV) is a significant societal problem that predominantly affects women and children. One behaviour that has been linked to DFV perpetration is coercive control. While various def...

The spatial patterning of emergency demand for police services: a scoping review

This preregistered scoping review provides an account of studies which have examined the spatial patterning of emergency reactive police demand (ERPD) as measured by calls for service data. To date, the field ...

Operationalizing deployment time in police calls for service

Analyses of emergency calls for service data in the United States suggest that around 50% of dispatched police deployment time is spent on crime-related incidents. The remainder of time is spent in a social se...

Predictors of police response time: a scoping review

As rapid response has been a key policing strategy for police departments around the globe, so has police response time been a key performance indicator. This scoping review maps and assesses the variables tha...

Counterfeits on dark markets: a measurement between Jan-2014 and Sep-2015

Counterfeits harm consumers, governments, and intellectual property holders. They accounted for 3.3% of worldwide trades in 2016, having an estimated value of $509 billion in the same year. Estimations in the ...

An analysis of protesting activity and trauma through mathematical and statistical models

The effect that different police protest management methods have on protesters’ physical and mental trauma is still not well understood and is a matter of debate. In this paper, we take a two-pronged approach ...

Characteristics and associated factors of self-reported sexual aggression in the Belgian population aged 16–69

Sexual violence is a major public health, societal, and judicial problem worldwide. Studies investigating the characteristics of its perpetrators often rely on samples of convicted offenders, which are biased ...

Do police stations deter crime?

The introduction of community policing led to a significant increase in the number of police stations, particularly in urban settings. Police stations are largely assumed to have an impact on crime but there a...

Exploring the impact of measurement error in police recorded crime rates through sensitivity analysis

It is well known that police recorded crime data is susceptible to substantial measurement error. However, despite its limitations, police data is widely used in regression models exploring the causes and effe...

Measuring the impact of the state of emergency on crime trends in Japan: a panel data analysis

City-specific temporal analysis has been commonly used to investigate the impact of COVID-19-related behavioural regulation policies on crime. However, these previous studies fail to consider differences in th...

Domestic abuse in the Covid-19 pandemic: measures designed to overcome common limitations of trend measurement

Research on pandemic domestic abuse trends has produced inconsistent findings reflecting differences in definitions, data and method. This study analyses 43,488 domestic abuse crimes recorded by a UK police fo...

Circumstances, policing, and attrition of multiple compared to single perpetrator rape cases within the South African criminal justice system

Research into the circumstances of rape, and criminal justice system responses, is pivotal to informing prevention and improving the likelihood of justice for victims. In this paper, we explore the differences...

Overlapped Bayesian spatio-temporal models to detect crime spots and their possible risk factors based on the Opole Province, Poland, in the years 2015–2019

Geostatistical methods currently used in modern epidemiology were adopted in crime science using the example of the Opole province, Poland, in the years 2015–2019. In our research, we applied the Bayesian spat...

Why do people legitimize and cooperate with the police? Results of a randomized control trial on the effects of procedural justice in Quito, Ecuador

The present study employs a randomized control trial design to evaluate the impact of deterrence and procedural justice on perceptions of legitimacy and cooperation with law enforcement among individuals in Qu...

The value of criminal history and police intelligence in vetting and selection of police

Despite decades of research considering police misconduct, there is still little consensus on officer characteristics associated with misconduct, and best practice for detection and prevention. While current r...

Do increases in the price of fuel increase levels of fuel theft? Evidence from England and Wales

Fuel prices have increased sharply over the past year. In this study we test the hypothesis that increases in the price of fuel are associated with increases in motorists filling their fuel tank and driving of...

A field-experiment testing the impact of a warrant service prioritization strategy for police patrol officers

The objective of this experiment was to test the efficacy of providing prioritized warrant lists to patrol officers. A field experiment was carried out with the Greensboro (NC) Police Department. Warrant risk ...

Going dark? Analysing the impact of end-to-end encryption on the outcome of Dutch criminal court cases

Law enforcement agencies struggle with criminals using end-to-end encryption (E2EE). A recent policy paper states: “while encryption is vital and privacy and cyber security must be protected, that should not c...

Considering the lip print patterns of Ibo and Hausa Ethnic groups of Nigeria: checking the wave of ethnically driven terrorism

Lip print of an individual is distinct and could be a useful form of evidence to identify the ethnicity of a terrorist.

Towards cyber-biosecurity by design: an experimental approach to Internet-of-Medical-Things design and development

The introduction of the internet and the proliferation of internet-connected devices (IoT) enabled knowledge sharing, connectivity and global communications. At the same time, these technologies generated a cr...

Police practitioner views on the challenges of analysing and responding to knife crime

Knife crime remains a major concern in England and Wales. Problem-oriented and public health approaches to tackling knife crime have been widely advocated, but little is known about how these approaches are un...

Supporting crime script analyses of scams with natural language processing

In recent years, internet connectivity and the ubiquitous use of digital devices have afforded a landscape of expanding opportunity for the proliferation of scams involving attempts to deceive individuals into...

Weather and crime: a systematic review of the empirical literature

The weather-crime association has intrigued scholars for more than 150 years. While there is a long-standing history of scholarly interest in the weather-crime association, the last decade has evidenced a mark...

Unpacking the police patrol shift: observations and complications of “electronically” riding along with police

As frontline responders, patrol officers exist at the core of policing. Little remains known, however, about the specific and nuanced work of contemporary patrol officers and their shift characteristics. Drawi...

Spatial distribution and developmental trajectories of crime versus crime severity: do not abandon the count-based model just yet

A new body of research that focuses on crime harm scores rather than counts of crime incidents has emerged. Specifically in the context of spatial analysis of crime, focusing on crime harm suggests that harm i...

Analysis of the risk of theft from vehicle crime in Kyoto, Japan using environmental indicators of streetscapes

With the advent of spatial analysis, the importance of analyzing crime patterns based on location has become more apparent. Previous studies have advanced our understanding of the factors associated with crime...

A multilevel examination of the association between COVID-19 restrictions and residence-to-crime distance

Restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted people’s daily routine activities. Rooted in crime pattern and routine activity theories, this study tests whether the enactment of a Safer-at-Home...

Correction: Offline crime bounces back to pre-COVID levels, cyber stays high: interrupted time-series analysis in Northern Ireland

The original article was published in Crime Science 2021 10 :26

Theorizing globally, but analyzing locally: the importance of geographically weighted regression in crime analysis

Theoretical relationships with crime across cities are explicitly or implicitly assumed to be the same in all places: a one-unit change in X leads to a β change in Y. But why would we assume the impact of unem...

Blowing in the wind? Testing the effect of weather on the spatial distribution of crime using Generalized Additive Models

Oslo, the capital of Norway, is situated in a North European cool climate zone. We investigate the effect of weather on the overall level of crime in the city, as well as the impact of different aspects of wea...

Illegal waste fly-tipping in the Covid-19 pandemic: enhanced compliance, temporal displacement, and urban–rural variation

Illegal dumping of household and business waste, known as fly-tipping in the UK, is a significant environmental crime. News agencies reported major increases early in the COVID-19 pandemic when waste disposal ...

Need to go further: using INLA to discover limits and chances of burglaries’ spatiotemporal prediction in heterogeneous environments

Near-repeat victimization patterns have made predictive models for burglaries possible. While the models have been implemented in different countries, the results obtained have not always been in line with ini...

Anti-social behaviour in the coronavirus pandemic

Anti-social behaviour recorded by police more than doubled early in the coronavirus pandemic in England and Wales. This was a stark contrast to the steep falls in most types of recorded crime. Why was ASB so d...

Say NOPE to social disorganization criminology: the importance of creators in neighborhood social control

Despite decades of research into social disorganization theory, criminologists have made little progress developing community programs that reduce crime. The lack of progress is due in part to faulty assumptio...

Different places, different problems: profiles of crime and disorder at residential parcels

Certain places generate inordinate amounts of crime and disorder. We examine how places differ in their nature of crime and disorder, with three objectives: (1) identifying a typology of profiles of crime and ...

Alone against the danger: a study of the routine precautions taken by voluntary sex workers to avoid victimisation

This article explores the routine precautions taken by sex workers (SW) in Switzerland, a country in which sex work is a legal activity. It is based on approximately 1100 h of non-systematic participant observ...

Explaining offenders’ longitudinal product-specific target selection through changes in disposability, availability, and value: an open-source intelligence web-scraping approach

To address the gap in the literature and using a novel open-source intelligence web-scraping approach, this paper investigates the longitudinal relationships between availability, value, and disposability, and...

Cryptocurrencies and future financial crime

Cryptocurrency fraud has become a growing global concern, with various governments reporting an increase in the frequency of and losses from cryptocurrency scams. Despite increasing fraudulent activity involvi...

More crime in cities? On the scaling laws of crime and the inadequacy of per capita rankings—a cross-country study

Crime rates per capita are used virtually everywhere to rank and compare cities. However, their usage relies on a strong linear assumption that crime increases at the same pace as the number of people in a reg...

Offline crime bounces back to pre-COVID levels, cyber stays high: interrupted time-series analysis in Northern Ireland

Much research has shown that the first lockdowns imposed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with changes in routine activities and, therefore, changes in crime. While several types of violent...

The Correction to this article has been published in Crime Science 2022 11 :11

Identifying seasonal spatial patterns of crime in a small northern city

To explore spatial patterns of crime in a small northern city, and assess the degree of similarity in these patterns across seasons.

The impact of the COVID-19, social distancing, and movement restrictions on crime in NSW, Australia

The spread of COVID-19 has prompted Governments around the world to impose draconian restrictions on business activity, public transport, and public freedom of movement. The effect of these restrictions appear...

The new normal of web camera theft on campus during COVID-19 and the impact of anti-theft signage

The opportunity for web camera theft increased globally as institutions of higher education transitioned to remote learning during COVID-19. Given the thousands of cameras currently installed in classrooms, ma...

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health calls for police service

Drawing upon seven years of police calls for service data (2014–2020), this study examined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on calls involving persons with perceived mental illness (PwPMI) using a Bayesian ...

A victim-centred cost–benefit analysis of a stalking prevention programme

Research suggests that stalking inflicts great psychological and financial costs on victims. Yet costs of victimisation are notoriously difficult to estimate and include as intangible costs in cost–benefit ana...

- Editorial Board

- Manuscript editing services

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

Annual Journal Metrics

2022 Citation Impact 6.1 - 2-year Impact Factor 4.7 - 5-year Impact Factor 1.951 - SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper) 1.755 - SJR (SCImago Journal Rank)

2023 Speed 12 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 224 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 445,839 downloads 324 Altmetric mentions

- More about our metrics

- ISSN: 2193-7680 (electronic)

- Follow us on Twitter

Crime Science

ISSN: 2193-7680

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

What the data says (and doesn’t say) about crime in the united states.

From the first day of his presidency to his campaign for reelection, Donald Trump has sounded the alarm about crime in the United States. Trump vowed to end “ American carnage ” in his inaugural address in 2017. This year, he ran for reelection on a platform of “ law and order .”

As Trump’s presidency draws to a close, here is a look at what we know – and don’t know – about crime in the U.S., based on a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the federal government and other sources.

Crime is a regular topic of discussion in the United States. We conducted this analysis to learn more about U.S. crime patterns and how those patterns have changed over time.

The analysis relies on statistics published by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), the statistical arm of the U.S. Department of Justice. FBI statistics were accessed through the Crime Data Explorer . BJS statistics were accessed through the National Crime Victimization Survey data analysis tool . Information about the federal government’s transition to the National Incident-Based Reporting System was drawn from the FBI and BJS, as well as from media reports.

To measure public attitudes about crime in the U.S., we relied on survey data from Gallup and Pew Research Center.

How much crime is there in the U.S.?

It’s difficult to say for certain. The two primary sources of government crime statistics – the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) – both paint an incomplete picture, though efforts at improvement are underway.

The FBI publishes annual data on crimes that have been reported to the police, but not those that haven’t been reported. The FBI also looks mainly at a handful of specific violent and property crimes, but not many other types of crime, such as drug crime. And while the FBI’s data is based on information it receives from thousands of federal, state, county, city and other police departments, not all agencies participate every year. In 2019, the most recent full year available, the FBI received data from around eight-in-ten agencies .

BJS, for its part, tracks crime by fielding a large annual survey of Americans ages 12 and older and asking them whether they were the victim of a crime in the past six months. One advantage of this approach is that it captures both reported and unreported crimes. But the BJS survey has limitations of its own. Like the FBI, it focuses mainly on a handful of violent and property crimes while excluding other kinds of crime. And since the BJS data is based on after-the-fact interviews with victims, it cannot provide information about one especially high-profile type of crime: murder.

All those caveats aside, looking at the FBI and BJS statistics side-by-side does give researchers a good picture of U.S. violent and property crime rates and how they have changed over time.

Which kinds of crime are most and least common?

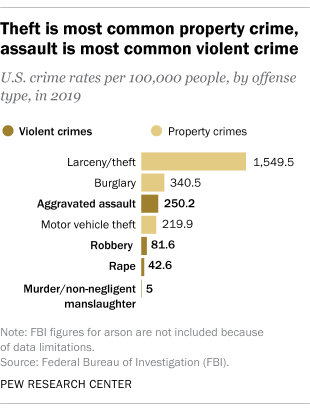

Property crime in the U.S. is much more common than violent crime. In 2019, the FBI reported a total of 2,109.9 property crimes per 100,000 people, compared with 379.4 violent crimes per 100,000 people.

By far the most common form of property crime in 2019 was larceny/theft, followed by burglary and motor vehicle theft. Among violent crimes, aggravated assault was the most common offense, followed by robbery, rape, and murder/non-negligent manslaughter.

BJS tracks a slightly different set of offenses from the FBI, but it finds the same overall patterns, with theft the most common form of property crime in 2019 and assault the most common form of violent crime.

How have crime rates in the U.S. changed over time?

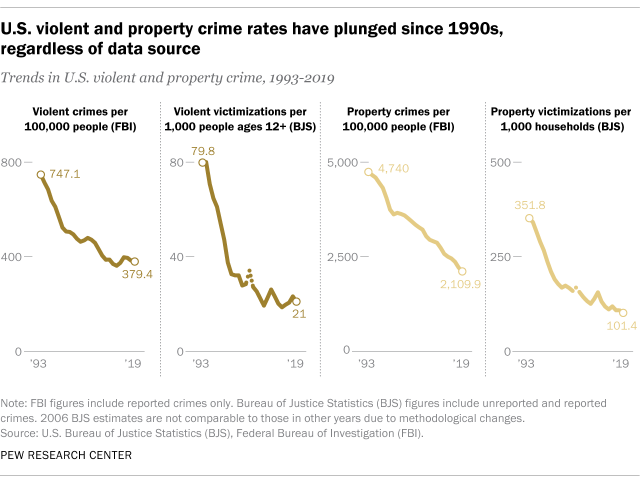

Both the FBI and BJS data show dramatic declines in U.S. violent and property crime rates since the early 1990s, when crime spiked across much of the nation.

Using the FBI data, the violent crime rate fell 49% between 1993 and 2019, with large decreases in the rates of robbery (-68%), murder/non-negligent manslaughter (-47%) and aggravated assault (-43%). (It’s not possible to calculate the change in the rape rate during this period because the FBI revised its definition of the offense in 2013 .) Meanwhile, the property crime rate fell 55%, with big declines in the rates of burglary (-69%), motor vehicle theft (-64%) and larceny/theft (-49%).

Using the BJS statistics, the declines in the violent and property crime rates are even steeper than those reported by the FBI. Per BJS, the overall violent crime rate fell 74% between 1993 and 2019, while the property crime rate fell 71%.

How do Americans perceive crime in their country?

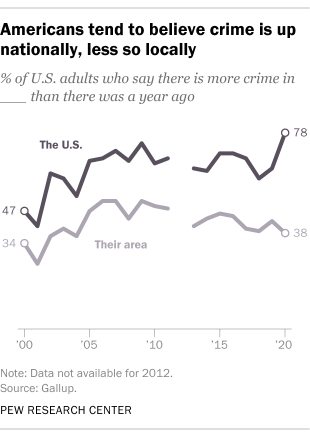

Americans tend to believe crime is up, even when the data shows it is down.

In 20 of 24 Gallup surveys conducted since 1993, at least 60% of U.S. adults have said there is more crime nationally than there was the year before, despite the generally downward trend in national violent and property crime rates during most of that period.

While perceptions of rising crime at the national level are common, fewer Americans believe crime is up in their own communities. In all 23 Gallup surveys that have included the question since 1993, no more than about half of Americans have said crime is up in their area compared with the year before.

This year, the gap between the share of Americans who say crime is up nationally and the share who say it is up locally (78% vs. 38%) is the widest Gallup has ever recorded .

Public attitudes about crime also differ by Americans’ partisan affiliation , race and ethnicity and other factors. For example, in a summer Pew Research Center survey , 74% of registered voters who support Trump said violent crime was “very important” to their vote in this year’s presidential election, compared with a far smaller share of Joe Biden supporters (46%).

How does crime in the U.S. differ by demographic characteristics?

There are some demographic differences in both victimization and offending rates, according to BJS.

In its 2019 survey of crime victims , BJS found wide differences by age and income when it comes to being the victim of a violent crime. Younger people and those with lower incomes were far more likely to report being victimized than older and higher-income people. For example, the victimization rate among those with annual incomes of less than $25,000 was more than twice the rate among those with incomes of $50,000 or more.

There were no major differences in victimization rates between male and female respondents or between those who identified as White, Black or Hispanic. But the victimization rate among Asian Americans was substantially lower than among other racial and ethnic groups.

When it comes to those who commit crimes, the same BJS survey asks victims about the perceived demographic characteristics of the offenders in the incidents they experienced. In 2019, those who are male, younger people and those who are Black accounted for considerably larger shares of perceived offenders in violent incidents than their respective shares of the U.S. population. As with all surveys, however, there are several potential sources of error, including the possibility that crime victims’ perceptions are incorrect.

How does crime in the U.S. differ geographically?

There are big differences in violent and property crime rates from state to state and city to city.

In 2019, there were more than 800 violent crimes per 100,000 residents in Alaska and New Mexico, compared with fewer than 200 per 100,000 people in Maine and New Hampshire, according to the FBI .

Even in similarly sized cities within the same state, crime rates can vary widely. Oakland and Long Beach, California, had comparable populations in 2019 (434,036 vs. 467,974), but Oakland’s violent crime rate was more than double the rate in Long Beach. The FBI notes that various factors might influence an area’s crime rate, including its population density and economic conditions.

See also: Despite recent violence, Chicago is far from the U.S. ‘murder capital’

What percentage of crimes are reported to police, and what percentage are solved?

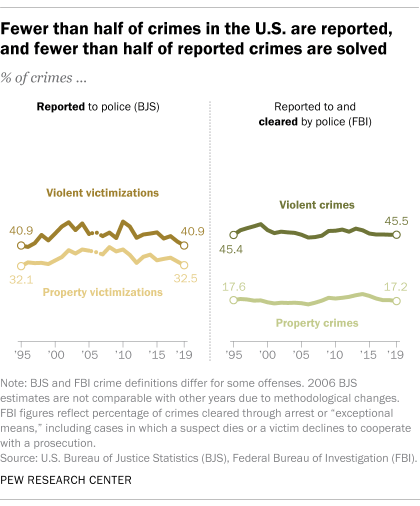

Most violent and property crimes in the U.S. are not reported to police, and most of the crimes that are reported are not solved.

In its annual survey, BJS asks crime victims whether they reported their crime to police or not. In 2019, only 40.9% of violent crimes and 32.5% of household property crimes were reported to authorities. BJS notes that there are a variety of reasons why crime might not be reported, including fear of reprisal or “getting the offender in trouble,” a feeling that police “would not or could not do anything to help,” or a belief that the crime is “a personal issue or too trivial to report.”

Most of the crimes that are reported to police, meanwhile, are not solved , at least based on an FBI measure known as the clearance rate. That’s the share of cases each year that are closed, or “cleared,” through the arrest, charging and referral of a suspect for prosecution, or due to “exceptional” circumstances such as the death of a suspect or a victim’s refusal to cooperate with a prosecution. In 2019, police nationwide cleared 45.5% of violent crimes that were reported to them and 17.2% of the property crimes that came to their attention.

Both the percentage of crimes that are reported to police and the percentage that are solved have remained relatively stable for decades.

Which crimes are most likely to be reported to police, and which are most likely to be solved?

Around eight-in-ten motor vehicle thefts (79.5%) were reported to police in 2019, making it by far the most commonly reported property crime tracked by BJS. Around half (48.5%) of household burglary and trespassing offenses were reported, as were 30% of personal thefts/larcenies and 26.8% of household thefts.

Among violent crimes, aggravated assault was the most likely to be reported to law enforcement (52.1%). It was followed by robbery (46.6%), simple assault (37.9%) and rape/sexual assault (33.9%).

The list of crimes cleared by police in 2019 looks different from the list of crimes reported. Law enforcement officers were generally much more likely to solve violent crimes than property crimes, according to the FBI.

The most frequently solved violent crime tends to be homicide. Police cleared around six-in-ten murders and non-negligent manslaughters (61.4%) last year. The clearance rate was lower for aggravated assault (52.3%), rape (32.9%) and robbery (30.5%).

When it comes to property crime, law enforcement agencies cleared 18.4% of larcenies/thefts, 14.1% of burglaries and 13.8% of motor vehicle thefts.

Is the government doing anything to improve its crime statistics?

Yes. The FBI has long recognized the limitations of its current data collection system and is planning to fully transition to a more comprehensive system beginning in 2021.

The new system, known as the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), will provide information on a much larger number of crimes , as well as details such as the time of day, location and types of weapons involved, if applicable. It will also provide demographic data, such as the age, sex, race and ethnicity of victims, known offenders and arrestees.

One key question looming over the transition is how many police departments will participate in the new system, which has been in development for decades. In 2019, the most recent year available, NIBRS received violent and property crime data from 46% of law enforcement agencies, covering 44% of the U.S. population that year . Some researchers have warned that the transition to a new system could leave important data gaps if more law enforcement agencies do not submit the requested information to the FBI.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

U.S. public divided over whether people convicted of crimes spend too much or too little time in prison

What we know about the increase in u.s. murders in 2020, america’s incarceration rate falls to lowest level since 1995, under trump, the federal prison population continued its recent decline, trump used his clemency power sparingly despite a raft of late pardons and commutations, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

April 11, 2024

Why We Believe the Myth of High Crime Rates

The crime issue, a focus of the 2024 presidential election, is sometimes rooted in the misplaced fears of people who live in some of the safest places

By Sara Novak

David Wall/Getty Images

Americans are convinced that they are living in a world ravaged by crime. In major cities, we fear riding public transportation or going out after dark. We buy weapons for self-defense and skip our nightly jogs . Next to the weather, the explosion of crime is a favorite topic of conversation. The overwhelming consensus is that crime is only getting worse. According to a Gallup poll, in late 2022, 78 percent of Americans contended that there was more crime than there used to be.

These perceptions would make sense if they were accurate, but they aren’t. Crime, in fact, is down in the U.S., rivaling low levels that haven’t been seen since the 1960s. According to FBI data , violent crime rates dropped by 8 percent and property crime dropped by about 6 percent by the third quarter of last year, compared with the same period in 2022. Still, the reality of these optimistic statistics doesn’t quell people’s fears.

New York City is a prime example. Crime was down by 6 percent in July 2023 from a year earlier. Specifically, murder was down by 11 percent, rape was down by 11 percent, and robbery was down by 6 percent. Yet at the time that these statistics were released in 2023, a poll of New Yorkers’ feelings around crime painted a grim picture of a city riddled with violence. The poll found that 61 percent of New Yorkers were worried about being the target of crime and that 36 percent fretted about the safety of public places. It is true that crime increased during the pandemic, and revising the way we view public safety after such a spike in crime statistics has ended happens at a slow pace. The pandemic is a case in point. The figures on major crime perceptions have remained inflated for years.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The reasons for such misperceptions are manifold. Crime tends to concentrate in certain places, mostly within poorer neighborhoods in cities such as Baltimore, New Orleans, Detroit, Birmingham, Ala., and Memphis, Tenn. This means that most of us will never experience it. Only 2 percent of people are ever affected by violent crime, and 15 percent are affected by any type of misconduct. Perceptions matter because in most cases, they are the sole basis for the fears that fuel the idea that crime is rampant. That can affect people in different ways. The older you are, for example, the more likely you are to fear crime even though you’re half as likely to ever experience it , compared with other age groups.

Even more surprisingly, if you live in a part of the country with little crime, you’re probably more frightened of it than people who actually live in the relatively few neighborhoods where it is commonplace, such as the Belmont neighborhood in Detroit or Hopkins–Middle East in Baltimore, where violent crimes are respectively 150 and 300 times more likely to happen, compared with other neighborhoods. A study published in the April 2018 issue of the journal Humanities and Social Sciences Communications found that “significant levels of fear are often reported by people who enjoy low levels of victimization.” Study co-author Steven Bishop , a social science expert at University College London, says that if you experience crime or the threat of it more often, you’re more likely to have adjusted your fears in line with reality. In neighborhoods with more crime, people harness their expectations and avoid the areas where criminals congregate. But when you’re never exposed to crime, you’re a poor judge of the risk of encountering it.

Oftentimes, our perceptions of crime are built around an imaginary “elsewhere” in which, in the most extreme scenario, civil order has collapsed, says Wesley G. Skogan , a professor of crime policy and the politics of crime at Northwestern University. When we’re asked about our own neighborhood, for example, we’re more likely to be moderately realistic about crime levels, compared with when we’re asked about other parts of the country. “Within your neighborhood, you’re talking about your own experiences and the experiences of those whom you know,” Skogan says. In other words, your own insights into levels of public safety are the most accurate.

There are many reasons for these attitudes. Partisanship plays a growing role in fueling these perspectives. Our perspectives on crime are shaped by the politics of the moment — and have been for some time. During both George H.W. Bush's and Bill Clinton's presidencies, opposing parties held similar views on crime. But around 2000, perspectives began to depend on who was in power. According to the 2022 Gallup Poll, with President Joe Biden in the White House, 73 percent of Republicans said crime in their area was growing while only 42 percent of Democrats agreed. “Crime has become a big partisan split with the biggest gap in history happening during the Biden administration,” says Skogan. What’s more, Republicans are also more likely to be somewhat older, which could be a factor contributing to their fear of crime. ( The average Republican is 50 years old , while the average Democrat is 47.)

Watershed events such as September 11 also contribute to how we think about crime. According to John Roman , director of the Center on Public Safety & Justice at NORC at the University of Chicago, the 9/11 attacks marked a period under the George W. Bush administration when our views about crime began to fall out of line with reality. Roman contends that, as a nation, we didn’t foresee the largest terrorist attack in our country’s history, and that makes us worry that even when crime statistics show a reduction, an unforeseen event may still strike without warning. “Ever since 9/11 we’ve been bombarded with warnings and messages that didn’t exist before,” Roman says. Every time you’re in an airport or train station, there are warning signs that say things like “if you see something, say something”—reminders that lead to hypervigilance.

After 9/11 the federal government took on a partial role as public safety overseer, instituting a color-coded warning system to alert us to pending terrorist attacks. But that warning system is gone—and according to Roman, people have been left to make their own judgments about what it means to be safe, which can translate into the feeling of having to be on guard all the time. Similar issues arise when changes are made in policing. More and more cities have the police patrol with their lights flashing; while the goal is to raise police visibility, that tactic can result in the opposite of its intended effect.

Additionally, features that create a sense of disorder within a given neighborhood—for example, graffiti, broken-down buildings and trash—are often wrongly associated with an increased risk of crime. According to a September 2023 study published in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning , “public space regeneration significantly improves safety perceptions for both genders.” Seeing drug use in public places, graffiti and people sleeping on public transportation all send psychological warning signs to the average person who’s just trying to get home from work. Still, it’s largely inaccurate messaging, in Roman’s view. “Disorder and danger really aren’t as highly correlated as people think,” he says.

Media reports contribute to these flawed perceptions. Crimes that happen halfway across the globe have no real impact on our personal experience of safety on the street but can still weigh heavily on our psyche, Bishop says. This is also true for social media. “Overall, media and social media influenced perceptions of how frequently crime occurs,” reported a September 2017 study published in the American International Journal of Social Science .

Pablo Navarrete Hernandez of the University of Sheffield in England, lead author of the 2023 Landscape and Urban Planning study, says that misplaced fears have been shown to have a major impact on perceptions about the neighborhoods in which we live and how public resources are allocated to them. Spending on police for neighborhoods with relatively low crime rates can divert expenditures from needier areas.

Misperceptions also affect those who end up alone and indoors because of fears of nonexistent crime. Parents may be afraid to take their kids to the park or on walks around the neighborhood. Fears of taking the metro or the bus may keep us at home. And older people may forgo their favorite hobbies and social contacts, contributing to the national epidemic of loneliness and the health risks that come with it. In the end, fear begins to hold us hostage much more than the risk of crime ever could.

Crime Rates in a Pandemic: the Largest Criminological Experiment in History

- Published: 16 June 2020

- Volume 45 , pages 525–536, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Ben Stickle ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8561-2070 1 &

- Marcus Felson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3173-072X 2

53k Accesses

114 Citations

131 Altmetric

12 Mentions

Explore all metrics

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 has impacted the world in ways not seen in generations. Initial evidence suggests one of the effects is crime rates, which appear to have fallen drastically in many communities around the world. We argue that the principal reason for the change is the government ordered stay-at-home orders, which impacted the routine activities of entire populations. Because these orders impacted countries, states, and communities at different times and in different ways, a naturally occurring, quasi-randomized control experiment has unfolded, allowing the testing of criminological theories as never before. Using new and traditional data sources made available as a result of the pandemic criminologists are equipped to study crime in society as never before. We encourage researchers to study specific types of crime, in a temporal fashion (following the stay-at-home orders), and placed-based. The results will reveal not only why, where, when, and to what extent crime changed, but also how to influence future crime reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Six months in: pandemic crime trends in England and Wales

Samuel Langton, Anthony Dixon & Graham Farrell

The U-shaped crime recovery during COVID-19: evidence from national crime rates in Mexico

Jose Roberto Balmori de la Miyar, Lauren Hoehn-Velasco & Adan Silverio-Murillo

Crime and punishment in times of pandemics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 is unquestionably one of the most significant world-wide events in recent history, impacting culture, government operations, crime, economics, politics, and social interactions for the foreseeable future. One unique aspect of this crisis is the governmental response of issuing legal stay-at-home orders to attempt to slow the spread of the virus. While these orders varied, both in degree and timing, between countries and states, they generally began with strong encouragement for persons to isolate themselves voluntarily. As the magnitude of the crisis grew, governments began legally mandating persons to stay-at-home to reduce the transmission rate of the virus. There were, of course, exceptions; workers who were deemed ‘essential,’ such as those in the fields of medicine, finance, public safety, food production, transportation, and in other miscellaneous industries did not have to abide by these orders to the degree to which the general public did.

Nevertheless, practically overnight, the entire country ceased or significantly reduced day-to-day travels, eliminating commutes from home to work, as well as leisure activities, shopping trips, social gatherings, the ability to dine out, and more. One poll in late March found that 90% of Americans, including essential workers, were ‘staying at home as much as possible’ (Washington Post-ABC, 2020 ). The ‘stay-at-home’ mandates brought about the most wide-reaching, significant, and sudden alteration of the lives of billions of people in human history. Across the United States and around the world, a positive byproduct (Fattah, 2020 ) of these unprecedented events is a dramatic drop in crime rates.

Initial Crime Data

Several researchers have made initial examinations into how crime rates have fluctuated in the advent of COVID-19. The results have been mixed, to say the least, especially when comparing broad categories of crime across different cities and with different methods and periods of study. However, these initial academic studies are intrinsically valuable and deserve to be mentioned here.

One of the earliest studies with perhaps the most striking results was by Shayegh and Malpede ( 2020 ), which identified an overall drop in crime in San Francisco of 43% and Oakland of about 50% following city issuance of some of the most restrictive and early stay-at-home orders in the US, beginning March 16th , 2020 and the two weeks after.

Surprisingly, significant results are also clearly seen when examining specific crimes against retailers in crime in Los Angeles. Pietrawska, Aurand, and Palmer ( 2020a ) found a 64% increase in retail burglary, while city-wide burglary rates were down 10%. Similarly, Pietrawska, Aurand, and Palmer ( 2020b ) identified a five-week change in crimes occurring at restaurants in Chicago, a 74% reduction, while city-wide crime declined 35%. Continuing their study of crime rates in the pandemic outside of a retail focus, Pietrawska, Aurand, and Palmer ( 2020c ) compared crimes against persons and crimes against property in four cities for ten weeks, finding sharp variations from week to week and within different crime types.

Another early study by Ashby ( 2020a ) of eight large US cities during the first few weeks of the crisis (January to March 23rd—before some states and areas implemented stay-at-home orders) found disparate impacts by crime type and location. For example, burglary declined in Austin, Los Angeles, Memphis, and Scan Francisco, but not in Louisville or Boston. Conversely, serious assaults in public declined in Austin, Los Angeles, and Louisville, but not other cities.

Felson, Jiang, and Xu ( 2020 ) examined burglary in Detroit during three periods, representing data before stay-at-home orders were in place and two periods under orders (March 10th to March 23rd and March 24th to March 31st). Their findings indicated an overall 32% decline in burglary, with the most substantial change in the third period. However, the decline was more significant in block groups of higher residential parcels than in mix-use land areas.

Campedelli et al. ( 2020 ) analyzed crime in Los Angeles in two time periods (the first ending March 16th and the second ending March 28th) using Bayesian structural time-series models to estimate what crime would have been if the COVID-19 pandemic had not occurred. Comparing the actual crime data against the estimated ‘sans-pandemic’ data, the first model found an overall crime reduction of 5.6% during the pandemic. Likewise, the second model (ending March 28th) showed a 15% reduction. Specifically, researchers found that overall crime rates significantly decreased, particularly when referencing robbery (−24%), shoplifting (−14%), theft (−21%), and battery (−11%). However, burglary, domestic violence, stolen vehicles, and homicide remained statically unchanged.

While not explicitly measuring crime rates, studies of calls for police service can function as an indirect measure of crime in a given area. Early studies of calls for service during the pandemic present mixed results. Lum, Maupin, and Stoltz ( 2020 ) found that 57% of 1000 agencies surveyed in the United States and Canada reported a reduction in calls for service in March of 2020. Ashby ( 2020b ), on the other hand, found no discernible difference in forecasted calls for service in 10 large US cities between the first identified cases of COVID-19 in the US throughout early March. However, Ashby found that once stay-at-home orders were implemented, calls for service did decline, although not evenly across call types or cities. In another study of police calls for service, Mohler et al. ( 2020 ) examined calls in Los Angeles and Indianapolis between January and mid-April; they concluded there was some impact on police calls for service but not across all crime types or places.

Internationally, Swedish researchers Gerell, Kardell, and Kindgren ( 2020 ) examined crime during the five weeks after government restrictions on activities began, observing an 8.8% total drop in reported crime despite the country’s somewhat lax response (when compared to other countries’ policies on restricting the public’s movement). Specifically, the researchers found residential burglary fell by 23%, commercial burglary declined 12.7%, and instances of pick-pocketing were reduced by a staggering 61% —however, there was little change in robberies or narcotics crime. In Australia, Payne and Morgan ( 2020 ) studied crime in March, finding assaults, sexual violations, and domestic violence were not significantly different from what was predicted under ‘normal’ conditions at the lower end of the confidence interval. They cautioned against early conclusions based on this data as the government orders came only a few weeks into the study.

These initial reports indicate that crime rates have indeed changed, but unequally across different categories, types, places, and timeframes. Among crime researchers, the featured question of this pandemic will be, “Why have crime rates fallen so dramatically?” The corollary is, “What can be learned from this experience to leverage crime reduction in the future?” The data and opportunities before every criminologist will provide near-endless research opportunities at levels never before possible, and every effort should be made to capture data and promote the study of crime. This research note aims to identify and encourage these lines of inquiry, to urge researchers to dive deeply into the data made available from the pandemic, and to provide the impetus for not only discerning why crime fell but also for how to pragmatically utilize this knowledge after the world emerges from seclusion.

Crime in Lock-Down: Theoretical Implications

During the few hours before a legal stay-at-home order was implemented, and throughout the first few weeks that followed, it is essential to note what likely did ‘not’ change. As people around the world returned from frantic and stress-filled trips to stock up on food and other essentials and closed the door to their residence behind them, their biological and physiological conditions changed very little, nor did the labels attributed to them by society, friends, or family. Poverty and inequality did not disappear or increase immediately. It is unlikely that self-control dramatically increased either. There were, however, things that did change; society became more disorganized, and social influences and relationships were suddenly cut, diminished, or otherwise altered. Strain, stress, and anomie likely increased significantly as many became fearful for the future (both financially and physically) and estranged from family and friends whom they could not visit physically. Further, punitive responses to crime (i.e., deterrence) were slowed or ceased altogether as courts closed, police were encouraged to reduce contact with the public, and thousands of prisoners were released early.

With crime declining at such a significant pace and many of the often-attributed circumstances impacting crime staying consistent or in some cases increasing or decreasing in a direction opposite of what many believe drives crime, many criminological theories appear to be struggling to explain the abrupt and sweeping change. We believe the scope and nature of crime changes during the COVID-19 crisis will become a proving ground for the many theories that attempt to explain the etiology of criminal behavior. In the end, this naturally occurring experiment will advance our knowledge of crime and human behavior as no other event has ever done during the era in which criminological data were widely available.

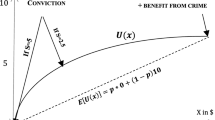

As such, we argue that the single most salient aspect of the steep fall in crime rates during the COVID-19 pandemic are the legal stay-at-home orders (i.e., lock-down, shelter-in-place) implemented to slow the spread of the virus by promoting social distancing. Stay-at-home orders were issued by most states and legally required residence to stay within their homes except for authorized activities. Commonly, these activities included seeking health care, purchasing food and other necessary supplies, banking, and similar activities. The orders either outright closed or by de-facto closed broad swaths of the economy and impacted schools, private social gatherings, religious activities, travel, and more. In short, these orders disrupted the daily activities of entire populations and was the only variable that changed abruptly, just days before double-digit drops in crime around the world. As such, we believe, the Environmental Criminology suite of perspectives including; Rational Choice (Clarke & Felson, 1993 ) and Routine Activity (Cohen & Felson, 1979 ) will emerge as frontrunners in understanding the crime changes during COVID-19 and will provide insight how to influence crime in the future.

A Call to Examine Crime

Therefore, we offer a call for examining crime before, during, and after a government-imposed stay-at-home order, that coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we advocate for researchers to consider crime in the context of temporal shifts, in a place-based context, to use emerging data sources, and to study crime with specificity.

Crime Specificity

Criminologists tend to overgeneralize about crime while underestimating the enormous specificity in offender decision making (LeClerc, & Wortley, R. (Eds.)., 2013 ). Even within each crime type, the finer particulars of an offense should be studied to understand how crime patterns change and shift. Specificity is even more critical when researching crime in a pandemic as it allows for an understanding of nuanced changes, such as opportunity structure, that would otherwise be missed. For example, the changes in daily activities in the wake of the pandemic tend to decrease the population in non-residential parts of the metropolis, while increasing the population in residential zones.

For example, the broad category of ‘theft’ appears to be down across many cities in the US (Ashby, 2020a ). However, theft is likely not declining evenly across all categories. Consider theft in a retail context. The retail sector has experienced an 85% decline in foot traffic after the stay-at-home orders were implemented (Jahshan, 2020 ); many stores are closed, and thus the opportunity for shoplifting and employee theft are curtailed. Pietrawska et al. ( 2020a ), for example, identified a 24% decline in shoplifting in Los Angeles, compared to a city-wide decline of theft at only 5%. However, theft may persist (and even see an increase) within stores that remain open such as grocers, construction supplies, convenience stores, pharmacies, and other ‘essential’ retailers. These thefts may be the result of a change in offender behavior (i.e., shifting from targeting a specific store—now closed, to another that is open), due to panic buying (i.e., purchasing limits on essential products may result in theft), or impacted by reduced guardianship within the stores (e.g., short-staffed employees are more focused on service than crime prevention).

One of the most exciting illustrations of crime specificity has to do with pocket-picking the covert removal of a wallet from a pocket or purse in a crowded venue. This crime thrives on a crowd, perhaps more than any other form. As noted earlier, Swedish researchers (Gerell et al., 2020 ) found that pocket-picking decreased by 61% in Stockholm during the COVID-affected period when crowd-reduction was especially emphasized. These findings underscore the importance of linking specific changes in routines to specific types of crime.

Theft may also be moving outside of the physical retail structure and developing in areas where officially reported came data is not readily available. For example, before COVID-19 package theft (e.g., packages delivered outside a residence and stolen before the owner can retrieve them) was a growing concern, and few, if any, police agencies kept data on the problem (Stickle, Hicks, Stickle, & Hutchinson, 2020 ). However, with entire populations confined to their homes, shopping has shifted virtually, and delivery of products has risen 74% (ACI, 2020 ). As a result, the opportunity for theft of packages left unattended at a residence may be increasing (Stickle, 2020a ). While more person may be home, daily routine activities have also been interrupted, which impact guardianship. As a result, packages left unattended for extended periods or forgotten altogether (Stickle, 2020b ).

These are just a few examples of why examining specific crime types and situations is vital to criminology. It allows the researcher to identify nuanced changes that are important when developing future prevention techniques and to test theoretical tools. There are, no doubt, many factors that are impacting pandemic crime rates, and only by examining them with specificity can researchers achieve an enhanced understanding of crime.

Temporal Shift

Temporal understanding of crime is essential because the time of day, day of the week, months, seasons, and other time-related factors are commonly known to impact crime; in other words, crime is not evenly distributed across place or time (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1995 ). However, stay-at-home orders that have people living, working, eating, and finding entertainment at home as weekdays merge into weekends may cause time distinctions to blur when speaking of crime. The change in the population’s routine behavior, even at home, is already being seen in online browsing habits and television use; behavior has shifted to higher viewing rates on Mondays than on the traditional Saturday (Comcast, 2020 ). To address these unusual, pandemic-generated changes in routine activities, criminologists need to examine crime rates in a different temporal perspective and consider the context of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. However, there must be more specificity than a pre and post examination of crime trends, and measurements at the state and even community level are needed to ensure accuracy.

We propose the following seven important periods for identification and comparison of crime rate changes related to the crisis (Table 1 ).

These measures must be tailored to individual communities or states to coincide with routine activity trends and government orders. Period 1 should be of sufficient time to establish some base levels of crime rates. Period 2 is where the beginning of voluntary behavior changes is likely to be observable, somewhere around mid-February, and extending until the government ordered quarantines for the general population. During this time, as concern swept across the nation, many people chose to alter their lifestyles; schools closed, and other modifications in society likely began to impact crime slowly. For example, an early study of police calls for service by Mohler et al. ( 2020 ) found routine activities began to change 8 to 10 days before stay-at-home orders were enacted in Los Angeles, California, and Indianapolis, Indiana, as well as other cities and other nations.

Periods 3 and 4 are contingent on the length of the government-ordered closures. For example, if a state was under stay-at-home orders for 4 weeks, we recommend examining an early period (period 3) as well as a late period (period 4) of two weeks. Dividing the length of stay-at-home orders by half (or more if the order is longer than six weeks) will capture the changes in routine activity as the stay-at-home orders continue. Capturing this data in two or more periods is crucial as the longer the order continues, the more likely people will begin to violate the order, and crime rates may begin to change. For example, early reports in Sweden saw a slight decline in vandalism (−4%), followed by a sharp increase after five weeks into the restrictions. There is also likely some relationship between non-compliance and crime as Nivette et al. ( 2020 ) found non-compliance with stay-at-home orders was associated with delinquent behavior. While early reports have not identified the same trends in the US, news reports during the month of May (Koetsier, 2020 ) indicated that a large number of persons were emerging from homes before an official end to the stay-at-home orders. A rise in crime may be detected because it is possible that the longer the orders continue, the less effective they become.

Lastly, periods 5 and 6 are difficult to define as the situation is still unfolding at the time of this publication, as a complete rescinded stay-at-home order has not occurred to date. Moreover, it is also critical to consider that many individuals who live in an area where the stay-at-home orders have been partially revoked may still choose not to return to their daily lives (see a news report by Schaul et al., 2020 ). This is why it will be important to capture data starting at the point of a rescinded stay-at-home order and by measuring crime rates every few weeks after that for an extended period. These periods may coincide with the phased re-opening plan followed by many governments (see CDC, 2020 ) or within a timeframe for several weeks each, which may result in the need to add continued periods of crime data.

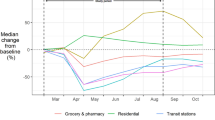

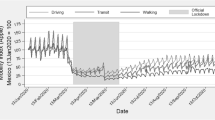

Criminologists do not have to rely on the assumption that people follow stay-at-home orders. For the first time, Mobility Trend Reports are being offered free (including in CSV format) by both Google ( 2020 ) and Apple ( 2020 ). These reports offer aggregated movement data based on anonymized cell phone location history at the national, state, and county levels. The data includes daily reports and includes inferred locations (i.e., retail, grocery, parks, transit, residential, workplace). With this data, it is possible to compare societal behavior within these recommended periods and gain a more accurate picture of where people were and importantly when they were there. Combined with the ability to measure compliance with movement restrictions, criminologists have the data to examine the routine activities of whole populations at a level never before possible while overlaying crime rates for both a temporal a place-based evaluation.

Place-Based

Studying crime based at a place is another critical part of understanding not only crime trends but also methods to disrupt crime (Eck & Weisburd, 2015 ). Under the current circumstances with people’s daily routine disrupted, this is even more important as people shift to more time within the home, the opportunities and places for offenders and victims to meet become limited. As a result, there is likely far less crime as people; both victims and offenders are not together in a place for the crime to occur.

To illustrate, consider workplace violence and crime. With a significant number of persons at home, rather than work, there is a reduced opportunity for offenders to assault co-workers. Similarly, there is less opportunity for a victim to have a phone stolen from the breakroom. It is important to remember that during the COVID-19 crisis, variables commonly related to many other criminological theories (i.e., poverty, stress, self-control) have not changed to such a degree to explain the sharp reduction in crime. Instead, the opportunity to be connected to a victim in time and place appears to be the most significant variable that has led to a marked reduction in the workplace and other place-based crimes.

However, in some regards, this place-based shift may result in increased crime rates in other areas (Roberts, 2020 ). For example, while digital, the internet can be classified as a ‘place’ or medium for victimization to occur (Machimbarrena et al., 2018 ). Under the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders, people are spending significantly more time online. By late March, for example, cable internet usage, as reported by The Internet and Television Association ( 2020 ), surged more than 30% and continued to grow until mid-April, which appears to coincide with many of the stay-at-home orders. The increased time using the internet likely leads to more opportunities for cybercrimes to occur as the victim’s virtual presence has shifted dramatically (e.g., away from place-based crime at work or school and to place-based crime online). Additionally, offenders may have also been impacted by the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and have increased time to identify victims.

Shifting back to a physical place and crimes, it is also important to evaluate land usage and population density when considering crime trends. There are emerging trends in the new COVID-19 crime data suggesting crime differences in certain places (Ashby, 2020a ). For example, public places such as stores, restaurants, and entertainment areas are experiencing sharp decreases in some types of crime (Pietrawska et al., 2020a ), while crime in the home may be remaining consistent (Campbdelli, 2020; Payne & Morgan, 2020 ; Shayegh & Malpede, 2020 , and mix-land use may see relatively stable or slightly increasing crime rates (Felson et al., 2020 ). Here again, routine activities and rational choice perspectives may explain much of the crime in these places. For instance, entertainment businesses and districts, along with dine-in restaurants, were generally closed during the orders. Thus, with fewer offenders routinely in these places and fewer victims present, crime will naturally decline. However, a reasoning offender (Cornish & Clarke, 2014 ) may choose to target areas with fewer people (i.e., guardians) such as closed malls, business parks, and other places that may see an increase in property crimes. Additionally, mixed land usage, especially in population-dense areas, may allow an offender to travel in areas unnoticed easily and, therefore, present opportunities for crime (Felson et al., 2020 ).

Place, whether virtual or physical, is a crucial factor in crime. The COVID-19 crisis has re-shaped the places that persons routinely visit, increasing some—home and online, while decreasing others—work, retail, school, and entertainment. Highlighting the role that place has played in crime rates during the pandemic should influence how criminologists study crime in a post-pandemic world and lead to further crime reduction through place-based prevention techniques.

Data-Driven

We have listed some initial findings on crime in the COVID-19 era and also described the need to study crime specifically, temporally, and place-based. Next, we will discuss data for measuring crime. One problem in criminology, as in other social science fields, is there are too many variables, too little variation, or an inability to control for specific variables. However, in the current pandemic, these problems decrease dramatically, and criminologists should take advantage of the favorable conditions and abundant data.

First, as described in the introduction, few variables changed during the first several weeks of the pandemic. The most substantial change has been the stay-at-home orders, which impacted the routine activities of entire populations. With so few variables changed, it should be easier to identify and measure significant and substantial changes in crime. Second, the variation in crime rates has been drastic. On the order of 10%, 20%, and even sometimes 60% transformation of crime patterns. These significant measurable changes allow researchers to see ‘past’ other variables that have little impact and focus on the significant variables impacting crime. Third, with entire populations affected by the pandemic, there is little need for controlling traditional variables such as age, gender, education, social status, and more. The impacted population is closer to the entire population rather than a ‘sample population,’ which means it is possible to move beyond inferential statistics and measure the actual change in the whole population.

Another challenge for criminologists is crime data. We encourage the use of four broad categories of data, including official police reports, victim and other self-report surveys, private or anecdotal data, and public data. Police data is an essential source during the pandemic. However, with many agencies experiencing workforce-related issues during the pandemic and purposely reducing the person-to-person contact to reduce the risk of virus spread, the official police data may underreport crime more than usual. Further, with more persons staying inside and not venturing out to school and work, other crimes, such as intimate partner violence and abuse of children, may not be captured through traditional reporting means. Therefore, it will be important that victim and self-report surveys continue to be used to help capture data that official reports do not (see Krohn, Thornberry, Gibson, & Baldwin, 2010 ).

Other sources of direct crime data and ancillary sources are often overlooked. Ancillary sources of data can take the form of calls to abuse hotlines, reports on consumer spending, internet traffic, police call for service, hospital mandatory reporting on specific injuries, and the Bureau of Labor Statics ( 2020 ) data on injuries resulting from violence at the workplace. Additionally, sources from private companies also provide insight into crime not always reported through official channels. For example, many retail organizations release data on crime within their stores, credit card companies release fraud statistics, and insurance organizations publish claims related to crime victimization. These sources may be particularly important as many areas where crime is occurring during the COVID-19 crisis are within private spaces, and obtaining non-police data is essential to understanding the crime shift. Lastly, other publicly available resources should be included in the analysis as well. Specifically, Mobility Trend Reports by Apple and Google, which provide detailed information on population location daily that the county level. This data set, never before publicly provided, should be used to overlay with other data (see Mohler et al., 2020 ).

Moving beyond the data to the methods, the circumstances of the COVID-19 crisis has led to a naturally occurring quasi-random control trial. Because each state-issued stay-at-home order at different times, under different circumstances, and rescinded them at different dates, it is possible to compare crime across many population groups. For example, Kentucky issued an order on March 26th and entered phased re-opening on May 11th (47 days) while neighboring state Tennessee waited seven more days, issuing a stay-at-home order on March 31st, and began a phased re-opening on April 27th, fourteen days ahead of its neighbor. These states, which share many demographic similarities, are ideal for comparison.

In addition to the unequal start and stop dates for state-wide lock-downs, the activities limited by the orders varied as well; for instance, some states kept parks open while others closed them. Similarly, some states outlawed gatherings of 10 or more, while other states established different criteria. The response to alcohol also creates a valuable point in data analysis. Examples abound of states that relaxed laws on alcohol sales, such as Kentucky, which allowed for the first-time home delivery of alcohol and service of alcohol with food take-out orders during the crisis (Minton, 2020 ). On the other end of the spectrum, some states deemed alcohol ‘non-essential’ but changed course after public backlash. For example, Pennsylvania initially closed liquor stores and created a cascade of persons traveling outside the state seeking alcohol (Thomas, 2020 ). Conditions such as these either between states or even within states are plentiful and provide essential data points that allow for an excellent comparison of crime and related factors.

The Largest Criminological Experiment in History

There is little doubt that the COVID-19 crisis will impact history on a scale not seen since WWII. Provisional insights indicate that a substantial drop in crime is occurring around the world and within the US. However, these reports also indicate the changes are not even across time, place, or crime type. Therefore, we encourage criminologists to study this crisis through the use of new and existing sources of crime data, with a specificity of crime types, in a temporal fashion, and placed based.

Moreover, the leading feature of these crime changes will be that the government ordered stay-at-home mandates, which impacted the routine activities of entire populations. The variation in these orders by state and community regarding when the orders were implemented and rescinded and what restrictions were in place has provided a naturally occurring, quasi-randomized control experiment. For example, researchers can compare states and communities that released prisoners early, increased or reduced alcohol availability, began lock-downs early, crime in public places as opposed to residential and mixed land use, and operationalize many variables that were previously intangible or inarticulable.

The findings emerging from the COVID-19 crisis will impact criminological theories for the next several decades. We encourage researchers to embark on in-depth explorations of the data made available from the pandemic and to search for not only why, where, when, and to what extent crime fell, but also how to use this knowledge for practical applications after the world returns to ‘normal’ and concludes this experiment in crime reduction and extraordinary test of human determination and resiliency.

ACI (2020). COVID-19 crisis driving changes in ecommerce purchasing behaviors, ACI Worldwide Research Reveals: https://www.aciworldwide.com/news-and-events/press-releases/2020/april/covid-19-crisis-drives-changes-in-ecommerce-sales-aci-worldwide-research-reveals

Apple Inc. (2020). COVID-19 - Mobility trends reports . https://www.apple.com/covid19/mobility

Ashby, M. P. J. (2020a). Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Science, 9 (6). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-020-00117-6 .

Ashby, M. P. J. (2020b). Changes in police calls for service during the early months of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/h4mcu

Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1995). Criminality of place. European journal on criminal policy and research, 3 (3), 5–26.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020). News release , Bureau of Labor Statics US Department of Labor: The Employment Situation – April 2020 . https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

Campedelli, G. M., Aziani, A., & Favarin, S. (2020). Exploring the effect of 2019-nCoV containment policies on crime: The case of los angeles. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.11021.

Center for Disease Control (2020). Guidelines opening up American again. https://www.whitehouse.gov/openingamerica/

Clarke, R. V. G., & Felson, M. (Eds.). (1993). Routine activity and rational choice (Vol. 5). Transaction publishers.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44 , 588–608.

Article Google Scholar

Comcast (2020). COVID-19 TV habits suggest the days are blurring together. https://corporate.comcast.com/stories/xfinity-viewing-data-covid-19

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (Eds.). (2014). The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending. Transaction Publishers.

Eck, J., & Weisburd, D. L. (2015). Crime places in crime theory. Crime and place: Crime prevention studies, 4 .

Fattah, E. A. (2020). A social Scientist’s look at a global crisis: Reflections on the likely positive impact of the Corona virus . Special Paper: School of Criminology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada.

Google Scholar

Felson, M., Jiang, S., & Xu, Y. (2020). Research note: Routine activity effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on burglary in Detroit, March 2020.

Gerell, M., Kardell, J., & Kindgren, J. (2020). Minor COVID-19 association with crime in Sweden, a five week follow up . Malmo University https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/w7gka/ .

Google (2020). COVID-19 Community Mobility Report. https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/

Jahshan, E. (2020). Retail footfall declines at sharpest rate in march. Retail Gazette: https://www.retailgazette.co.uk/blog/2020/04/retail-footfall-declines-at-sharpest-rate-in-march/

Koetsier, J. (2020). Apple data shows shelter-in-place is ending, whether governments want it to or not. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/05/01/apple-data-shows-shelter-in-place-is-ending-whether-governments-want-it-to-or-not/#6e35fbdd6fb5 .

Krohn, M. D., Thornberry, T. P., Gibson, C. L., & Baldwin, J. M. (2010). The development and impact of self-report measures of crime and delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26 (4), 509–525.

LeClerc, B., & Wortley, R. (Eds.). (2013). Cognition and crime: Offender decision making and script analyses . Routledge.

Lum, C., Maupin, C., & Stoltz, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on law enforcement agencies (wave 1) . International Association of Chiefs of police. https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/IACP-GMU survey.Pdf.

Machimbarrena, J. M., Calvete, E., Fernández-González, L., Álvarez-Bardón, A., Álvarez-Fernández, L., & González-Cabrera, J. (2018). Internet risks: An overview of victimization in cyberbullying, cyber dating abuse, sexting, online grooming and problematic internet use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15 (11), 2471.

Minton, M. (2020). Cocktails in quarantine: How your state governs booze buying during lock-down. (2020). Competitive Enterprise Institute: https://cei.org/blog/cocktails-quarantine-how-your-state-governs-booze-buying-during-lockdown

Mohler, G., Bertozzie, A. L., Carter, J., Short, M. B., Sledge, D., Tia, G. E., Uchida, C., D., and Brantingham, P. J. (2020). Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 101692.

Nivette, A., Ribeaud, D., Murray, A. L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Hepp, U., Shanahan, L., & Eisner, M. (2020). Non-compliance with COVID-19-related public health measures among young adults: Insights from a longitudinal cohort study. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/8edbj

Payne, J., & Morgan, A. (2020). Property Crime during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A comparison of recorded offence rates and dynamic forecasts (ARIMA) for March 2020 in Queensland, Australia.

Pietrawska, B., Aurand, S. K. & Palmer, W. (2020a) Covid-19 and crime: CAP’s perspective on crime and loss in the age of Covid-19: Los Angeles crime. CAP Index, Issue 19.2.

Pietrawska, B., Aurand, S. K. & Palmer, W. (2020b) Covid-19 and crime: CAP’s perspective on crime and loss in the age of Covid-19: Crime in Los Angeles and Chicago during Covid-19. CAP Index, Issue 19.3.

Pietrawska, B., Aurand, S. K. & Palmer, W. (2020c) Covid-19 and crime: CAP’s perspective on crime and loss in the age of Covid-19: Crime in Los Angeles and Chicago during Covid-19. CAP Index, Issue 19.4.

Roberts, K. (2020). Opportunity knocks: How crime patterns can change during a pandemic. Australian Institute of Police Management. https://www.aipm.gov.au/karl-roberts-opportunity-knocks-coronavirus

Schaul, K., Mayes, B. R., & Berkowitz, B. (2020). Where Americans are still staying at home the most. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/national/map-us-still-staying-home-coronavirus/

Shayegh, S., & Malpede, M. (2020). Staying Home Saves Lives, Really! In Staying home saves lives, really! . RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3567394 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Stickle, B. (2020a) Porch piracy: Here’s what we learned after watching hours of YouTube videos showing packages being pilfered from homes. The Conversation : https://theconversation.com/porch-piracy-heres-what-we-learned-after-watching-hours-of-youtube-videos-showing-packages-being-pilfered-from-homes-132497

Stickle, B. (2020b). Package theft in a pandemic . Jill Dando Institute of Security and Crime Science: University College London https://www.ucl.ac.uk/jill-dando-institute/sites/jill-dando-institute/files/package_theft_in_a_pandemic_final_no_15_.pdf .

Stickle, B., Hicks, M., Stickle, A., & Hutchinson, Z. (2020). Porch pirates: Examining unattended package theft through crime script analysis. Criminal Justice Studies, 33 (2), 79–95.