- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

The Ultimate Guide to Getting Your Thesis Published in a Journal

- 7-minute read

- 25th February 2023

Writing your thesis and getting it published are huge accomplishments. However, publishing your thesis in an academic journal is another journey for scholars. Beyond how much hard work, time, and research you invest, having your findings published in a scholarly journal is vital for your reputation as a scholar and also advances research findings within your field.

This guide will walk you through how to make sure your thesis is ready for publication in a journal. We’ll go over how to prepare for pre-publication, how to submit your research, and what to do after acceptance.

Pre-Publication Preparations

Understanding the publishing process.

Ideally, you have already considered what type of publication outlet you want your thesis research to appear in. If not, it’s best to do this so you can tailor your writing and overall presentation to fit that publication outlet’s expectations. When selecting an outlet for your research, consider the following:

● How well will my research fit the journal?

● Are the reputation and quality of this journal high?

● Who is this journal’s readership/audience?

● How long does it take the journal to respond to a submission?

● What’s the journal’s rejection rate?

Once you finish writing, revising, editing, and proofreading your work (which can take months or years), expect the publication process to be an additional three months or so.

Revising Your Thesis

Your thesis will need to be thoroughly revised, reworked, reorganized, and edited before a journal will accept it. Journals have specific requirements for all submissions, so read everything on a journal’s submission requirements page before you submit. Make a checklist of all the requirements to be sure you don’t overlook anything. Failing to meet the submission requirements could result in your paper being rejected.

Areas for Improvement

No doubt, the biggest challenge academics face in this journey is reducing the word count of their thesis to meet journal publication requirements. Remember that the average thesis is between 60,000 and 80,000 words, not including footnotes, appendices, and references. On the other hand, the average academic journal article is 4,000 to 7,000 words. Reducing the number of words this much may seem impossible when you are staring at the year or more of research your thesis required, but remember, many have done this before, and many will do it again. You can do it too. Be patient with the process.

Additional areas of improvement include>

· having to reorganize your thesis to meet the section requirements of the journal you submit to ( abstract, intro , methods, results, and discussion).

· Possibly changing your reference system to match the journal requirements or reducing the number of references.

· Reformatting tables and figures.

· Going through an extensive editing process to make sure everything is in place and ready.

Identifying Potential Publishers

Many options exist for publishing your academic research in a journal. However, along with the many credible and legitimate publishers available online, just as many predatory publishers are out there looking to take advantage of academics. Be sure to always check unfamiliar publishers’ credentials before commencing the process. If in doubt, ask your mentor or peer whether they think the publisher is legitimate, or you can use Think. Check. Submit .

If you need help identifying which journals your research is best suited to, there are many tools to help. Here’s a short list:

○ Elsevier JournalFinder

○ EndNote Matcher

○ Journal/Author Name Estimator (JANE)

○ Publish & Flourish Open Access

· The topics the journal publishes and whether your research will be a good fit.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

· The journal’s audience (whom you want to read your research).

· The types of articles the journal publishes (e.g., reviews, case studies).

· Your personal requirements (e.g., whether you’re willing to wait a long time to see your research published).

Submitting Your Thesis

Now that you have thoroughly prepared, it’s time to submit your thesis for publication. This can also be a long process, depending on peer review feedback.

Preparing Your Submission

Many publishers require you to write and submit a cover letter along with your research. The cover letter is your sales pitch to the journal’s editor. In the letter, you should not only introduce your work but also emphasize why it’s new, important, and worth the journal’s time to publish. Be sure to check the journal’s website to see whether submission requires you to include specific information in your cover letter, such as a list of reviewers.

Whenever you submit your thesis for publication in a journal article, it should be in its “final form” – that is, completely ready for publication. Do not submit your thesis if it has not been thoroughly edited, formatted, and proofread. Specifically, check that you’ve met all the journal-specific requirements to avoid rejection.

Navigating the Peer Review Process

Once you submit your thesis to the journal, it will undergo the peer review process. This process may vary among journals, but in general, peer reviews all address the same points. Once submitted, your paper will go through the relevant editors and offices at the journal, then one or more scholars will peer-review it. They will submit their reviews to the journal, which will use the information in its final decision (to accept or reject your submission).

While many academics wait for an acceptance letter that says “no revisions necessary,” this verdict does not appear very often. Instead, the publisher will likely give you a list of necessary revisions based on peer review feedback (these revisions could be major, minor, or a combination of the two). The purpose of the feedback is to verify and strengthen your research. When you respond to the feedback , keep these tips in mind:

● Always be respectful and polite in your responses, even if you disagree.

● If you do disagree, be prepared to provide supporting evidence.

● Respond to all the comments, questions, and feedback in a clear and organized manner.

● Make sure you have sufficient time to make any changes (e.g., whether you will need to conduct additional experiments).

After Publication

Once the journal accepts your article officially, with no further revisions needed, take a moment to enjoy the fruits of your hard work. After all, having your work appear in a distinguished journal is not an easy feat. Once you’ve finished celebrating, it’s time to promote your work. Here’s how you can do that:

● Connect with other experts online (like their posts, follow them, and comment on their work).

● Email your academic mentors.

● Share your article on social media so others in your field may see your work.

● Add the article to your LinkedIn publications.

● Respond to any comments with a “Thank you.”

Getting your thesis research published in a journal is a long process that goes from reworking your thesis to promoting your article online. Be sure you take your time in the pre-publication process so you don’t have to make lots of revisions. You can do this by thoroughly revising, editing, formatting, and proofreading your article.

During this process, make sure you and your co-authors (if any) are going over one another’s work and having outsiders read it to make sure no comma is out of place.

What are the benefits of getting your thesis published?

Having your thesis published builds your reputation as a scholar in your field. It also means you are contributing to the body of work in your field by promoting research and communication with other scholars.

How long does it typically take to get a thesis published?

Once you have finished writing, revising, editing, formatting, and proofreading your thesis – processes that can add up to months or years of work – publication can take around three months. The exact length of time will depend on the journal you submit your work to and the peer review feedback timeline.

How can I ensure the quality of my thesis when attempting to get it published?

If you want to make sure your thesis is of the highest quality, consider having professionals proofread it before submission (some journals even require submissions to be professionally proofread). Proofed has helped thousands of researchers proofread their theses. Check out our free trial today.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Utility Menu

- ARC Scheduler

- Student Employment

- Senior Theses

Doing a senior thesis is an exciting enterprise. It’s often the first time students are engaging in truly original research and trying to develop a significant contribution to a field of inquiry. But as joyful as an independent research process can be, you don’t have to go it alone. It’s important to have support as you navigate such a large endeavor, and the ARC is here to offer one of those layers of support.

Whether or not to write a senior thesis is just the first in a long line of questions thesis writers need to consider. In addition to questions about the topic and scope of your thesis, there are questions about timing, schedule, and support. For example, if you are collecting data, when should data collection start and when should it be completed? What kind of schedule will you write on? How will you work with your adviser? Do you want to meet with your adviser about your progress once a month? Once a week? What other resources can you turn to for information, feedback, and support?

Even though there is a lot to think about and a lot to do, doing a thesis really can be an enjoyable experience! Keep reminding yourself why you chose this topic and why you care about it.

Tips for Tackling Big Projects:

Break the process down into manageable chunks.

- When you’re approaching a big project, it can seem overwhelming to look at the whole thing at once, so it’s essential to identify the smaller steps that will move you towards the completed project.

- Your adviser is best suited to help you break down the thesis process with field-specific advice.

- If you need to refine the breakdown further so it makes sense for you, schedule an appointment with an Academic Coach . An academic coach can help you think through the steps in a way that works for you.

Schedule brief writing sessions at regular times.

- Pre-determine the time, place, and duration.

- Keep it short (15 to 60 minutes).

- Have a clear and reasonable goal for each writing session.

- Make it a regular event (every day, every other day, MWF).

- time is not wasted deciding to write if it’s already in your calendar;

- keeping sessions short reduces the competition from other tasks that are not getting done;

- having an achievable goal for each session provides a sense of accomplishment (a reward for your work);

- writing regularly can turn into a productive habit.

Create accountability structures.

- In addition to having a clear goal for each writing session, it's important to have clear goals for each week and to find someone to communicate these goals to, such as your adviser, a “thesis buddy,” your roommate, etc. Communicating your goals and progress to someone else creates a useful sense of accountability.

- If your adviser is not the person you are communicating your progress to on a weekly basis, then request to set up a structure with your adviser that requires you to check in at less frequent but regular intervals.

- Commit to attending Accountability Hours at the ARC on the same day every week. Making that commitment will add both social support and structure to your week. Use the ARC Scheduler to register for Accountability Hours.

- Set up an accountability group in your department or with thesis writers from different departments.

Create feedback structures.

- It’s important to have a means for getting consistent feedback on your work and to get that feedback early. Work on large projects often lacks the feeling of completeness, so don’t wait for a whole section (and certainly not the whole thesis) to feel “done” before you get feedback on it!

- Your thesis adviser is typically the person best positioned to give you feedback on your research and writing, so communicate with your adviser about how and how often you would like to get feedback.

- If your adviser isn’t able to give you feedback with the frequency you’d like, then fill in the gaps by creating a thesis writing group or exploring if there is already a writing group in your department or lab.

- The Harvard College Writing Center is a great resource for thesis feedback. Writing Center Senior Thesis Tutors can provide feedback on the structure, argument, and clarity of your writing and help with mapping out your writing plan. Visit the Writing Center website to schedule an appointment with a thesis tutor .

Accept that there will be some anxious moments.

- To reduce this source of anxiety, try keeping a separate document where you jot down ideas on how your research questions or central argument might be clarifying or changing as you research and write. Doing this will enable you to stay focused on the section you are working on and to stop worrying about forgetting the new ideas that are emerging.

- You might feel anxious when you realize that you need to update your argument in response to the evidence you have gathered or the new thinking your writing has unleashed. Know that that is OK. Research and writing are iterative processes – new ideas and new ways of thinking are what makes progress possible.

- Breaking down big projects into manageable chunks and mapping out a schedule for working through each chunk is one way to reduce this source of anxiety. It’s reassuring to know you are working towards the end even if you cannot quite see how it will turn out.

- It may be that your thesis or dissertation never truly feels “done” to you, but that’s okay. Academic inquiry is an ongoing endeavor.

Focus on what works for you.

- Just because your roommate wrote 10 pages in a day doesn’t mean that’s the right pace or strategy for you.

- If you are having trouble figuring out what works for you, use the ARC Scheduler to make an appointment with an Academic Coach , who can help you come up with daily, weekly, and semester-long plans.

Use your resources.

- There’s a lot of the thesis writing process that has to be done independently, but there are also a lot of free resources at Harvard to help you do the work.

- If you’re having trouble finding a source, email your question or set up a research consult via Ask a Librarian .

- If you’re looking for additional feedback or help with any aspect of writing, contact the Harvard College Writing Center . The Writing Center has Senior Thesis Tutors who will read drafts of your thesis (more typically, parts of your thesis) in advance and meet with you individually to talk about structure, argument, clear writing, and mapping out your writing plan.

- If you need help with breaking down your project or setting up a schedule for the week, the semester, or until the deadline, use the ARC Scheduler to make an appointment with an Academic Coach .

- If you would like an accountability structure for social support and to keep yourself on track, come to Accountability Hours at the ARC.

Accordion style

- Assessing Your Understanding

- Building Your Academic Support System

- Common Class Norms

- Effective Learning Practices

- First-Year Students

- How to Prepare for Class

- Interacting with Instructors

- Know and Honor Your Priorities

- Memory and Attention

- Minimizing Zoom Fatigue

- Note-taking

- Office Hours

- Perfectionism

- Scheduling Time

- Study Groups

- Tackling STEM Courses

- Test Anxiety

Honors Theses

What this handout is about.

Writing a senior honors thesis, or any major research essay, can seem daunting at first. A thesis requires a reflective, multi-stage writing process. This handout will walk you through those stages. It is targeted at students in the humanities and social sciences, since their theses tend to involve more writing than projects in the hard sciences. Yet all thesis writers may find the organizational strategies helpful.

Introduction

What is an honors thesis.

That depends quite a bit on your field of study. However, all honors theses have at least two things in common:

- They are based on students’ original research.

- They take the form of a written manuscript, which presents the findings of that research. In the humanities, theses average 50-75 pages in length and consist of two or more chapters. In the social sciences, the manuscript may be shorter, depending on whether the project involves more quantitative than qualitative research. In the hard sciences, the manuscript may be shorter still, often taking the form of a sophisticated laboratory report.

Who can write an honors thesis?

In general, students who are at the end of their junior year, have an overall 3.2 GPA, and meet their departmental requirements can write a senior thesis. For information about your eligibility, contact:

- UNC Honors Program

- Your departmental administrators of undergraduate studies/honors

Why write an honors thesis?

Satisfy your intellectual curiosity This is the most compelling reason to write a thesis. Whether it’s the short stories of Flannery O’Connor or the challenges of urban poverty, you’ve studied topics in college that really piqued your interest. Now’s your chance to follow your passions, explore further, and contribute some original ideas and research in your field.

Develop transferable skills Whether you choose to stay in your field of study or not, the process of developing and crafting a feasible research project will hone skills that will serve you well in almost any future job. After all, most jobs require some form of problem solving and oral and written communication. Writing an honors thesis requires that you:

- ask smart questions

- acquire the investigative instincts needed to find answers

- navigate libraries, laboratories, archives, databases, and other research venues

- develop the flexibility to redirect your research if your initial plan flops

- master the art of time management

- hone your argumentation skills

- organize a lengthy piece of writing

- polish your oral communication skills by presenting and defending your project to faculty and peers

Work closely with faculty mentors At large research universities like Carolina, you’ve likely taken classes where you barely got to know your instructor. Writing a thesis offers the opportunity to work one-on-one with a with faculty adviser. Such mentors can enrich your intellectual development and later serve as invaluable references for graduate school and employment.

Open windows into future professions An honors thesis will give you a taste of what it’s like to do research in your field. Even if you’re a sociology major, you may not really know what it’s like to be a sociologist. Writing a sociology thesis would open a window into that world. It also might help you decide whether to pursue that field in graduate school or in your future career.

How do you write an honors thesis?

Get an idea of what’s expected.

It’s a good idea to review some of the honors theses other students have submitted to get a sense of what an honors thesis might look like and what kinds of things might be appropriate topics. Look for examples from the previous year in the Carolina Digital Repository. You may also be able to find past theses collected in your major department or at the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library. Pay special attention to theses written by students who share your major.

Choose a topic

Ideally, you should start thinking about topics early in your junior year, so you can begin your research and writing quickly during your senior year. (Many departments require that you submit a proposal for an honors thesis project during the spring of your junior year.)

How should you choose a topic?

- Read widely in the fields that interest you. Make a habit of browsing professional journals to survey the “hot” areas of research and to familiarize yourself with your field’s stylistic conventions. (You’ll find the most recent issues of the major professional journals in the periodicals reading room on the first floor of Davis Library).

- Set up appointments to talk with faculty in your field. This is a good idea, since you’ll eventually need to select an advisor and a second reader. Faculty also can help you start narrowing down potential topics.

- Look at honors theses from the past. The North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library holds UNC honors theses. To get a sense of the typical scope of a thesis, take a look at a sampling from your field.

What makes a good topic?

- It’s fascinating. Above all, choose something that grips your imagination. If you don’t, the chances are good that you’ll struggle to finish.

- It’s doable. Even if a topic interests you, it won’t work out unless you have access to the materials you need to research it. Also be sure that your topic is narrow enough. Let’s take an example: Say you’re interested in the efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s and early 1980s. That’s a big topic that probably can’t be adequately covered in a single thesis. You need to find a case study within that larger topic. For example, maybe you’re particularly interested in the states that did not ratify the ERA. Of those states, perhaps you’ll select North Carolina, since you’ll have ready access to local research materials. And maybe you want to focus primarily on the ERA’s opponents. Beyond that, maybe you’re particularly interested in female opponents of the ERA. Now you’ve got a much more manageable topic: Women in North Carolina Who Opposed the ERA in the 1970s and 1980s.

- It contains a question. There’s a big difference between having a topic and having a guiding research question. Taking the above topic, perhaps your main question is: Why did some women in North Carolina oppose the ERA? You will, of course, generate other questions: Who were the most outspoken opponents? White women? Middle-class women? How did they oppose the ERA? Public protests? Legislative petitions? etc. etc. Yet it’s good to start with a guiding question that will focus your research.

Goal-setting and time management

The senior year is an exceptionally busy time for college students. In addition to the usual load of courses and jobs, seniors have the daunting task of applying for jobs and/or graduate school. These demands are angst producing and time consuming If that scenario sounds familiar, don’t panic! Do start strategizing about how to make a time for your thesis. You may need to take a lighter course load or eliminate extracurricular activities. Even if the thesis is the only thing on your plate, you still need to make a systematic schedule for yourself. Most departments require that you take a class that guides you through the honors project, so deadlines likely will be set for you. Still, you should set your own goals for meeting those deadlines. Here are a few suggestions for goal setting and time management:

Start early. Keep in mind that many departments will require that you turn in your thesis sometime in early April, so don’t count on having the entire spring semester to finish your work. Ideally, you’ll start the research process the semester or summer before your senior year so that the writing process can begin early in the fall. Some goal-setting will be done for you if you are taking a required class that guides you through the honors project. But any substantive research project requires a clear timetable.

Set clear goals in making a timetable. Find out the final deadline for turning in your project to your department. Working backwards from that deadline, figure out how much time you can allow for the various stages of production.

Here is a sample timetable. Use it, however, with two caveats in mind:

- The timetable for your thesis might look very different depending on your departmental requirements.

- You may not wish to proceed through these stages in a linear fashion. You may want to revise chapter one before you write chapter two. Or you might want to write your introduction last, not first. This sample is designed simply to help you start thinking about how to customize your own schedule.

Sample timetable

Avoid falling into the trap of procrastination. Once you’ve set goals for yourself, stick to them! For some tips on how to do this, see our handout on procrastination .

Consistent production

It’s a good idea to try to squeeze in a bit of thesis work every day—even if it’s just fifteen minutes of journaling or brainstorming about your topic. Or maybe you’ll spend that fifteen minutes taking notes on a book. The important thing is to accomplish a bit of active production (i.e., putting words on paper) for your thesis every day. That way, you develop good writing habits that will help you keep your project moving forward.

Make yourself accountable to someone other than yourself

Since most of you will be taking a required thesis seminar, you will have deadlines. Yet you might want to form a writing group or enlist a peer reader, some person or people who can help you stick to your goals. Moreover, if your advisor encourages you to work mostly independently, don’t be afraid to ask them to set up periodic meetings at which you’ll turn in installments of your project.

Brainstorming and freewriting

One of the biggest challenges of a lengthy writing project is keeping the creative juices flowing. Here’s where freewriting can help. Try keeping a small notebook handy where you jot down stray ideas that pop into your head. Or schedule time to freewrite. You may find that such exercises “free” you up to articulate your argument and generate new ideas. Here are some questions to stimulate freewriting.

Questions for basic brainstorming at the beginning of your project:

- What do I already know about this topic?

- Why do I care about this topic?

- Why is this topic important to people other than myself

- What more do I want to learn about this topic?

- What is the main question that I am trying to answer?

- Where can I look for additional information?

- Who is my audience and how can I reach them?

- How will my work inform my larger field of study?

- What’s the main goal of my research project?

Questions for reflection throughout your project:

- What’s my main argument? How has it changed since I began the project?

- What’s the most important evidence that I have in support of my “big point”?

- What questions do my sources not answer?

- How does my case study inform or challenge my field writ large?

- Does my project reinforce or contradict noted scholars in my field? How?

- What is the most surprising finding of my research?

- What is the most frustrating part of this project?

- What is the most rewarding part of this project?

- What will be my work’s most important contribution?

Research and note-taking

In conducting research, you will need to find both primary sources (“firsthand” sources that come directly from the period/events/people you are studying) and secondary sources (“secondhand” sources that are filtered through the interpretations of experts in your field.) The nature of your research will vary tremendously, depending on what field you’re in. For some general suggestions on finding sources, consult the UNC Libraries tutorials . Whatever the exact nature of the research you’re conducting, you’ll be taking lots of notes and should reflect critically on how you do that. Too often it’s assumed that the research phase of a project involves very little substantive writing (i.e., writing that involves thinking). We sit down with our research materials and plunder them for basic facts and useful quotations. That mechanical type of information-recording is important. But a more thoughtful type of writing and analytical thinking is also essential at this stage. Some general guidelines for note-taking:

First of all, develop a research system. There are lots of ways to take and organize your notes. Whether you choose to use note cards, computer databases, or notebooks, follow two cardinal rules:

- Make careful distinctions between direct quotations and your paraphrasing! This is critical if you want to be sure to avoid accidentally plagiarizing someone else’s work. For more on this, see our handout on plagiarism .

- Record full citations for each source. Don’t get lazy here! It will be far more difficult to find the proper citation later than to write it down now.

Keeping those rules in mind, here’s a template for the types of information that your note cards/legal pad sheets/computer files should include for each of your sources:

Abbreviated subject heading: Include two or three words to remind you of what this sources is about (this shorthand categorization is essential for the later sorting of your sources).

Complete bibliographic citation:

- author, title, publisher, copyright date, and page numbers for published works

- box and folder numbers and document descriptions for archival sources

- complete web page title, author, address, and date accessed for online sources

Notes on facts, quotations, and arguments: Depending on the type of source you’re using, the content of your notes will vary. If, for example, you’re using US Census data, then you’ll mainly be writing down statistics and numbers. If you’re looking at someone else’s diary, you might jot down a number of quotations that illustrate the subject’s feelings and perspectives. If you’re looking at a secondary source, you’ll want to make note not just of factual information provided by the author but also of their key arguments.

Your interpretation of the source: This is the most important part of note-taking. Don’t just record facts. Go ahead and take a stab at interpreting them. As historians Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff insist, “A note is a thought.” So what do these thoughts entail? Ask yourself questions about the context and significance of each source.

Interpreting the context of a source:

- Who wrote/created the source?

- When, and under what circumstances, was it written/created?

- Why was it written/created? What was the agenda behind the source?

- How was it written/created?

- If using a secondary source: How does it speak to other scholarship in the field?

Interpreting the significance of a source:

- How does this source answer (or complicate) my guiding research questions?

- Does it pose new questions for my project? What are they?

- Does it challenge my fundamental argument? If so, how?

- Given the source’s context, how reliable is it?

You don’t need to answer all of these questions for each source, but you should set a goal of engaging in at least one or two sentences of thoughtful, interpretative writing for each source. If you do so, you’ll make much easier the next task that awaits you: drafting.

The dread of drafting

Why do we often dread drafting? We dread drafting because it requires synthesis, one of the more difficult forms of thinking and interpretation. If you’ve been free-writing and taking thoughtful notes during the research phase of your project, then the drafting should be far less painful. Here are some tips on how to get started:

Sort your “evidence” or research into analytical categories:

- Some people file note cards into categories.

- The technologically-oriented among us take notes using computer database programs that have built-in sorting mechanisms.

- Others cut and paste evidence into detailed outlines on their computer.

- Still others stack books, notes, and photocopies into topically-arranged piles.There is not a single right way, but this step—in some form or fashion—is essential!

If you’ve been forcing yourself to put subject headings on your notes as you go along, you’ll have generated a number of important analytical categories. Now, you need to refine those categories and sort your evidence. Everyone has a different “sorting style.”

Formulate working arguments for your entire thesis and individual chapters. Once you’ve sorted your evidence, you need to spend some time thinking about your project’s “big picture.” You need to be able to answer two questions in specific terms:

- What is the overall argument of my thesis?

- What are the sub-arguments of each chapter and how do they relate to my main argument?

Keep in mind that “working arguments” may change after you start writing. But a senior thesis is big and potentially unwieldy. If you leave this business of argument to chance, you may end up with a tangle of ideas. See our handout on arguments and handout on thesis statements for some general advice on formulating arguments.

Divide your thesis into manageable chunks. The surest road to frustration at this stage is getting obsessed with the big picture. What? Didn’t we just say that you needed to focus on the big picture? Yes, by all means, yes. You do need to focus on the big picture in order to get a conceptual handle on your project, but you also need to break your thesis down into manageable chunks of writing. For example, take a small stack of note cards and flesh them out on paper. Or write through one point on a chapter outline. Those small bits of prose will add up quickly.

Just start! Even if it’s not at the beginning. Are you having trouble writing those first few pages of your chapter? Sometimes the introduction is the toughest place to start. You should have a rough idea of your overall argument before you begin writing one of the main chapters, but you might find it easier to start writing in the middle of a chapter of somewhere other than word one. Grab hold where you evidence is strongest and your ideas are clearest.

Keep up the momentum! Assuming the first draft won’t be your last draft, try to get your thoughts on paper without spending too much time fussing over minor stylistic concerns. At the drafting stage, it’s all about getting those ideas on paper. Once that task is done, you can turn your attention to revising.

Peter Elbow, in Writing With Power, suggests that writing is difficult because it requires two conflicting tasks: creating and criticizing. While these two tasks are intimately intertwined, the drafting stage focuses on creating, while revising requires criticizing. If you leave your revising to the last minute, then you’ve left out a crucial stage of the writing process. See our handout for some general tips on revising . The challenges of revising an honors thesis may include:

Juggling feedback from multiple readers

A senior thesis may mark the first time that you have had to juggle feedback from a wide range of readers:

- your adviser

- a second (and sometimes third) faculty reader

- the professor and students in your honors thesis seminar

You may feel overwhelmed by the prospect of incorporating all this advice. Keep in mind that some advice is better than others. You will probably want to take most seriously the advice of your adviser since they carry the most weight in giving your project a stamp of approval. But sometimes your adviser may give you more advice than you can digest. If so, don’t be afraid to approach them—in a polite and cooperative spirit, of course—and ask for some help in prioritizing that advice. See our handout for some tips on getting and receiving feedback .

Refining your argument

It’s especially easy in writing a lengthy work to lose sight of your main ideas. So spend some time after you’ve drafted to go back and clarify your overall argument and the individual chapter arguments and make sure they match the evidence you present.

Organizing and reorganizing

Again, in writing a 50-75 page thesis, things can get jumbled. You may find it particularly helpful to make a “reverse outline” of each of your chapters. That will help you to see the big sections in your work and move things around so there’s a logical flow of ideas. See our handout on organization for more organizational suggestions and tips on making a reverse outline

Plugging in holes in your evidence

It’s unlikely that you anticipated everything you needed to look up before you drafted your thesis. Save some time at the revising stage to plug in the holes in your research. Make sure that you have both primary and secondary evidence to support and contextualize your main ideas.

Saving time for the small stuff

Even though your argument, evidence, and organization are most important, leave plenty of time to polish your prose. At this point, you’ve spent a very long time on your thesis. Don’t let minor blemishes (misspellings and incorrect grammar) distract your readers!

Formatting and final touches

You’re almost done! You’ve researched, drafted, and revised your thesis; now you need to take care of those pesky little formatting matters. An honors thesis should replicate—on a smaller scale—the appearance of a dissertation or master’s thesis. So, you need to include the “trappings” of a formal piece of academic work. For specific questions on formatting matters, check with your department to see if it has a style guide that you should use. For general formatting guidelines, consult the Graduate School’s Guide to Dissertations and Theses . Keeping in mind the caveat that you should always check with your department first about its stylistic guidelines, here’s a brief overview of the final “finishing touches” that you’ll need to put on your honors thesis:

- Honors Thesis

- Name of Department

- University of North Carolina

- These parts of the thesis will vary in format depending on whether your discipline uses MLA, APA, CBE, or Chicago (also known in its shortened version as Turabian) style. Whichever style you’re using, stick to the rules and be consistent. It might be helpful to buy an appropriate style guide. Or consult the UNC LibrariesYear Citations/footnotes and works cited/reference pages citation tutorial

- In addition, in the bottom left corner, you need to leave space for your adviser and faculty readers to sign their names. For example:

Approved by: _____________________

Adviser: Prof. Jane Doe

- This is not a required component of an honors thesis. However, if you want to thank particular librarians, archivists, interviewees, and advisers, here’s the place to do it. You should include an acknowledgments page if you received a grant from the university or an outside agency that supported your research. It’s a good idea to acknowledge folks who helped you with a major project, but do not feel the need to go overboard with copious and flowery expressions of gratitude. You can—and should—always write additional thank-you notes to people who gave you assistance.

- Formatted much like the table of contents.

- You’ll need to save this until the end, because it needs to reflect your final pagination. Once you’ve made all changes to the body of the thesis, then type up your table of contents with the titles of each section aligned on the left and the page numbers on which those sections begin flush right.

- Each page of your thesis needs a number, although not all page numbers are displayed. All pages that precede the first page of the main text (i.e., your introduction or chapter one) are numbered with small roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv, v, etc.). All pages thereafter use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.).

- Your text should be double spaced (except, in some cases, long excerpts of quoted material), in a 12 point font and a standard font style (e.g., Times New Roman). An honors thesis isn’t the place to experiment with funky fonts—they won’t enhance your work, they’ll only distract your readers.

- In general, leave a one-inch inch margin on all sides. However, for the copy of your thesis that will be bound by the library, you need to leave a 1.25-inch margin on the left.

How do I defend my honors thesis?

Graciously, enthusiastically, and confidently. The term defense is scary and misleading—it conjures up images of a military exercise or an athletic maneuver. An academic defense ideally shouldn’t be a combative scene but a congenial conversation about the work’s merits and weaknesses. That said, the defense probably won’t be like the average conversation that you have with your friends. You’ll be the center of attention. And you may get some challenging questions. Thus, it’s a good idea to spend some time preparing yourself. First of all, you’ll want to prepare 5-10 minutes of opening comments. Here’s a good time to preempt some criticisms by frankly acknowledging what you think your work’s greatest strengths and weaknesses are. Then you may be asked some typical questions:

- What is the main argument of your thesis?

- How does it fit in with the work of Ms. Famous Scholar?

- Have you read the work of Mr. Important Author?

NOTE: Don’t get too flustered if you haven’t! Most scholars have their favorite authors and books and may bring one or more of them up, even if the person or book is only tangentially related to the topic at hand. Should you get this question, answer honestly and simply jot down the title or the author’s name for future reference. No one expects you to have read everything that’s out there.

- Why did you choose this particular case study to explore your topic?

- If you were to expand this project in graduate school, how would you do so?

Should you get some biting criticism of your work, try not to get defensive. Yes, this is a defense, but you’ll probably only fan the flames if you lose your cool. Keep in mind that all academic work has flaws or weaknesses, and you can be sure that your professors have received criticisms of their own work. It’s part of the academic enterprise. Accept criticism graciously and learn from it. If you receive criticism that is unfair, stand up for yourself confidently, but in a good spirit. Above all, try to have fun! A defense is a rare opportunity to have eminent scholars in your field focus on YOU and your ideas and work. And the defense marks the end of a long and arduous journey. You have every right to be proud of your accomplishments!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Atchity, Kenneth. 1986. A Writer’s Time: A Guide to the Creative Process from Vision Through Revision . New York: W.W. Norton.

Barzun, Jacques, and Henry F. Graff. 2012. The Modern Researcher , 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. 2014. “They Say/I Say”: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing , 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Lamott, Anne. 1994. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life . New York: Pantheon.

Lasch, Christopher. 2002. Plain Style: A Guide to Written English. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Turabian, Kate. 2018. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, alert: update to standardized testing policy.

Starting with those applying to the Harvard Class of 2029 (entering fall 2025), Harvard College will require the submission of standardized test scores from applicants for admission as part of the whole-person application review process that takes a whole-student approach. Please visit our FAQ for more information .

Last Updated: April 11, 12:37pm

Open Alert: Update to Standardized Testing Policy

Preparing for a senior thesis.

Every year, a little over half of Harvard’s senior class chooses to pursue a senior thesis. While the senior thesis looks a little different from field to field, one thing remains the same: completion of a senior thesis is a serious and challenging endeavor that requires the student to make a genuine intellectual contribution to their field of interest.

The senior thesis is a significant task for students to undertake, but there is a variety of support resources available here at Harvard to ensure that seniors can make the best of their senior thesis experience.

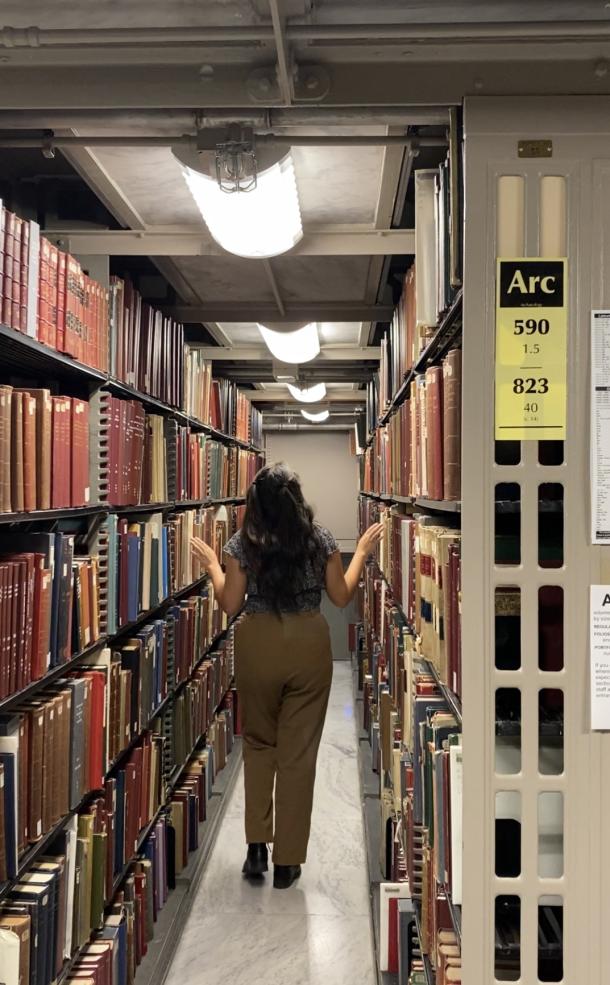

Wandering the library stacks at Widener.

I do most of my research in Widener Library. Hannah Martinez

As a rising senior in the History department, I am planning on pursuing a senior thesis on the history and use of the SAT in college admissions, and I am using the following support systems and resources to research and write my thesis:

- Staff at the History department. Every student within the department is assigned an academic advisor, who is a graduate student studying History at Harvard and knows the support available within the department. My academic advisor has helped me throughout the thesis process by connecting me with potential faculty members to advise my thesis and pick classes with a lighter course load so I can focus on completing my thesis. The Director of Undergraduate Studies in History (the History DUS) has also been pivotal in making sure that I attended a lot of information sessions about what the thesis looks like and how much of a commitment it is.

- History faculty at Harvard! All of my professors in History have been incredibly helpful in teaching me how to write like a historian, how to use primary sources in my essays, and how to undertake a serious research project over the course of a semester. Of course, while the thesis will require me to go far beyond what I’ve ever done before, I feel prepared to take on such a task because of the unwavering support from the History faculty. My mentor, Emma Rothschild, is one of the members of the faculty who has been invaluable in encouraging me to go as far as I am able.

- And last but certainly not least: funding. Funding, whether in term-time of the summer before senior year, is crucial towards making the senior thesis possible. Harvard’s Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships is dedicated to connecting Harvard students to funding sources across the university so they can pursue their research and get paid for it. This summer, I received a grant from the university of almost $2,000 so I am able to travel to libraries, buy books, and potentially take time off of work and do my research. Without such a grant, it would be incredibly difficult for me to do enough research so I can write a thesis this upcoming fall.

As you can see, there are multiple avenues for support and resources here at Harvard so your senior thesis is as easy as possible. While the senior thesis is still a challenging project that will take up a lot of time, Harvard’s resources make it possible for senior students to do their very best in all of their theses. I’m excited to start writing this fall!

Student Voices

How the mellon mays undergraduate fellowship propelled my love of archives into academic aspirations.

Beginning my senior thesis: A personal commitment to community and justice

Amy Class of '23 Alumni

Exploring Research at Harvard: Social Studies Edition

Olga Class of '22 Alumni

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

Published on September 9, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on July 18, 2023.

It can be difficult to know where to start when writing your thesis or dissertation . One way to come up with some ideas or maybe even combat writer’s block is to check out previous work done by other students on a similar thesis or dissertation topic to yours.

This article collects a list of undergraduate, master’s, and PhD theses and dissertations that have won prizes for their high-quality research.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Award-winning undergraduate theses, award-winning master’s theses, award-winning ph.d. dissertations, other interesting articles.

University : University of Pennsylvania Faculty : History Author : Suchait Kahlon Award : 2021 Hilary Conroy Prize for Best Honors Thesis in World History Title : “Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the “Noble Savage” on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807”

University : Columbia University Faculty : History Author : Julien Saint Reiman Award : 2018 Charles A. Beard Senior Thesis Prize Title : “A Starving Man Helping Another Starving Man”: UNRRA, India, and the Genesis of Global Relief, 1943-1947

University: University College London Faculty: Geography Author: Anna Knowles-Smith Award: 2017 Royal Geographical Society Undergraduate Dissertation Prize Title: Refugees and theatre: an exploration of the basis of self-representation

University: University of Washington Faculty: Computer Science & Engineering Author: Nick J. Martindell Award: 2014 Best Senior Thesis Award Title: DCDN: Distributed content delivery for the modern web

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

University: University of Edinburgh Faculty: Informatics Author: Christopher Sipola Award: 2018 Social Responsibility & Sustainability Dissertation Prize Title: Summarizing electricity usage with a neural network

University: University of Ottawa Faculty: Education Author: Matthew Brillinger Award: 2017 Commission on Graduate Studies in the Humanities Prize Title: Educational Park Planning in Berkeley, California, 1965-1968

University: University of Ottawa Faculty: Social Sciences Author: Heather Martin Award: 2015 Joseph De Koninck Prize Title: An Analysis of Sexual Assault Support Services for Women who have a Developmental Disability

University : University of Ottawa Faculty : Physics Author : Guillaume Thekkadath Award : 2017 Commission on Graduate Studies in the Sciences Prize Title : Joint measurements of complementary properties of quantum systems

University: London School of Economics Faculty: International Development Author: Lajos Kossuth Award: 2016 Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance Title: Shiny Happy People: A study of the effects income relative to a reference group exerts on life satisfaction

University : Stanford University Faculty : English Author : Nathan Wainstein Award : 2021 Alden Prize Title : “Unformed Art: Bad Writing in the Modernist Novel”

University : University of Massachusetts at Amherst Faculty : Molecular and Cellular Biology Author : Nils Pilotte Award : 2021 Byron Prize for Best Ph.D. Dissertation Title : “Improved Molecular Diagnostics for Soil-Transmitted Molecular Diagnostics for Soil-Transmitted Helminths”

University: Utrecht University Faculty: Linguistics Author: Hans Rutger Bosker Award: 2014 AVT/Anéla Dissertation Prize Title: The processing and evaluation of fluency in native and non-native speech

University: California Institute of Technology Faculty: Physics Author: Michael P. Mendenhall Award: 2015 Dissertation Award in Nuclear Physics Title: Measurement of the neutron beta decay asymmetry using ultracold neutrons

University: Stanford University Faculty: Management Science and Engineering Author: Shayan O. Gharan Award: Doctoral Dissertation Award 2013 Title: New Rounding Techniques for the Design and Analysis of Approximation Algorithms

University: University of Minnesota Faculty: Chemical Engineering Author: Eric A. Vandre Award: 2014 Andreas Acrivos Dissertation Award in Fluid Dynamics Title: Onset of Dynamics Wetting Failure: The Mechanics of High-speed Fluid Displacement

University: Erasmus University Rotterdam Faculty: Marketing Author: Ezgi Akpinar Award: McKinsey Marketing Dissertation Award 2014 Title: Consumer Information Sharing: Understanding Psychological Drivers of Social Transmission

University: University of Washington Faculty: Computer Science & Engineering Author: Keith N. Snavely Award: 2009 Doctoral Dissertation Award Title: Scene Reconstruction and Visualization from Internet Photo Collections

University: University of Ottawa Faculty: Social Work Author: Susannah Taylor Award: 2018 Joseph De Koninck Prize Title: Effacing and Obscuring Autonomy: the Effects of Structural Violence on the Transition to Adulthood of Street Involved Youth

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, July 18). Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 14, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/examples/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, checklist: writing a dissertation, thesis & dissertation database examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Yale College Undergraduate Admissions

- A Liberal Arts Education

- Majors & Academic Programs

- Teaching & Advising

- Undergraduate Research

- International Experiences

- Science & Engineering Faculty Features

- Residential Colleges

- Extracurriculars

- Identity, Culture, Faith

- Multicultural Open House

- Virtual Tour

- Bulldogs' Blogs

- First-Year Applicants

- International First-Year Applicants

- QuestBridge First-Year Applicants

- Military Veteran Applicants

- Transfer Applicants

- Eli Whitney: Nontraditional Applicants

- Non-Degree & Alumni Auditing Applicants

- What Yale Looks For

- Putting Together Your Application

- Selecting High School Courses

- Application FAQs

- First-Generation College Students

- Rural and Small Town Students

- Choosing Where to Apply

- Inside the Yale Admissions Office Podcast

- Visit Campus

- Virtual Events

- Connect With Yale Admissions

- The Details

- Estimate Your Cost

- QuestBridge

Search form

Writing a senior thesis: is it worth it.

Before coming to Yale, I thought a thesis was the main argument of a paper. I quickly learned that an undergraduate thesis is about fifty times harder and fifty pages longer than any thesis arguments I wrote in high school. At Yale, every senior has some sort of senior requirement, but thesis projects vary by department. Some departments require students to do a semester-long project, where you write a longer paper (25-35 pages) or expand, through writing, the research you’ve been working on (mostly applies to STEM majors). In some departments you can take two senior seminars and complete a longer project at the end of the semester. And other departments have an option to complete a year-long thesis: you spend your senior year (and in some cases your junior year), intensely researching and writing about a topic you choose or create yourself.

Both my departments––English and Ethnicity, Race, and Migration––offer all three of these options, and each student decides what they think is best for them. As a double major, I had the additional option to write an even longer thesis combining both my majors, but that seemed like way too much work––especially since I would have to take two senior thesis classes at the same time. Instead, I chose a year-long thesis for ER&M that combined my literary interests with various theoretical frameworks and the two senior seminars for English. This spring I’m taking my second seminar. Really, I chose the option to torture myself for a whole year, the end result being a minimum of 50 pages of innovative thinking and writing. I wanted to rise to the challenge, proving to myself I could do it. But there also seemed to be the pressure of “this is what everyone in the major does,” and a “thesis is proof that you actually learned.” Although these sentiments influenced my decision to complete a thesis, I know a long research paper does not validate my education or work as a scholar the last four years. It is not the end all be all.

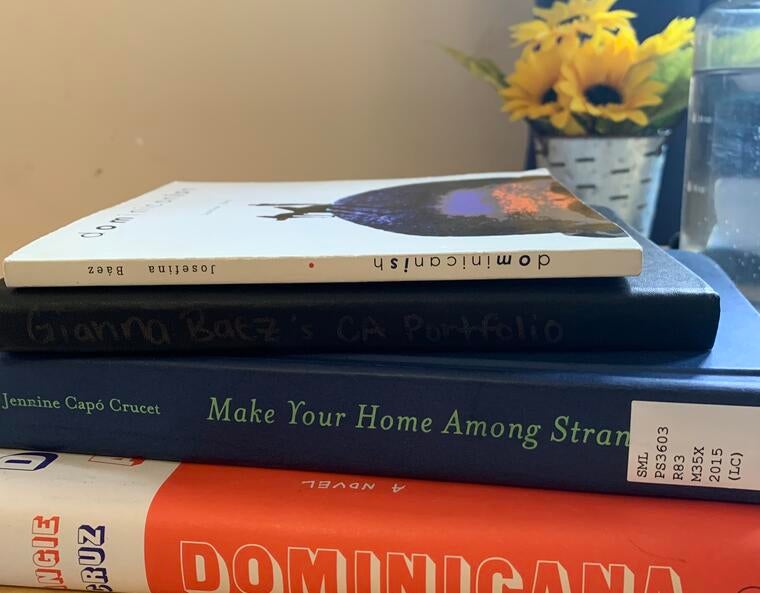

My senior thesis focuses on Caribbean literature - specifically, two novels written by Caribbean women that really look at what it means to come from an immigrant family, to move, and to find yourself in completely new spaces. These experiences are all too relatable to my own life as a second-generation woman of color with immigrant parents enrolled at Yale. In my writing, I focus on how these women make sense of “home” (a very broad and complicated topic, I know), and what their stories tell us about the diasporic experience in general. The project is very personal to me, and I chose it because I wanted to understand my family’s history and their task in making “home” in the U.S., whatever that means. But because it’s so personal, it’s also been really difficult. I’ve experienced a lot of writer’s block or often felt unmotivated and judgmental towards my work. I’ve realized how difficult it is to devote your time and energy to such a long process––not only is it research heavy, but you have to write and rewrite drafts, constantly adjusting to make sure you’re being as clear as possible. Really, writing a thesis is like writing a portion of a book. And that’s crazy! You’re writing two or three whole chapters of academic work as an undergraduate student.

The process is definitely not for everyone, and I’ve certainly thought “Why did I want to do this again?” But what’s really kept me going is the support from my advisors and friends. The ER&M department faculty does an amazing job of providing us mentorship, revisions, and support throughout the process; my advisor has served as my editor but also the person who reminds me most that this work is important, as I often forget that. It also helps to have many friends and people in the major also writing their theses. I’ve found different spaces to just have a thesis study hall or working time, with other people also struggling through. Recently, I submitted my first full draft (note: it was kind of unfinished but it’s okay because it’s a draft!), and it was crazy to think that I wrote 50+ pages, most of which are just my own original thoughts and analysis on two books that have almost no scholarship written about them. It was a relief for sure. This week I will be taking a full break from it, but it reminded me of why I began this journey. It reminded me of all the people who’ve supported me along the way, and how I really couldn’t have done it without them. And now, I’m really looking forward to how good it will feel to turn in my fully written thesis mid-April. I’ve realized that this project shouldn’t be about making it good for Yale’s standard, but for myself, for my family, and for the people who believe in this work as much as I do.

More Posts by Gianna

Senior Bucket List: All the things I had to do before I left Yale/New Haven

Meet Rhythmic Blue!

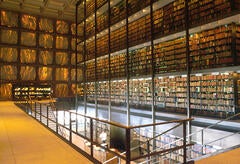

Medieval Manuscripts and the Beinecke Library

How I Navigated My Double Major

Rating Boba in New Haven

Quarantine Birthdays

Welcome to the Trumbutt!!!!

Yale IMs: Intramural Sports #MOORAH

Reimagining Virtual Relationships

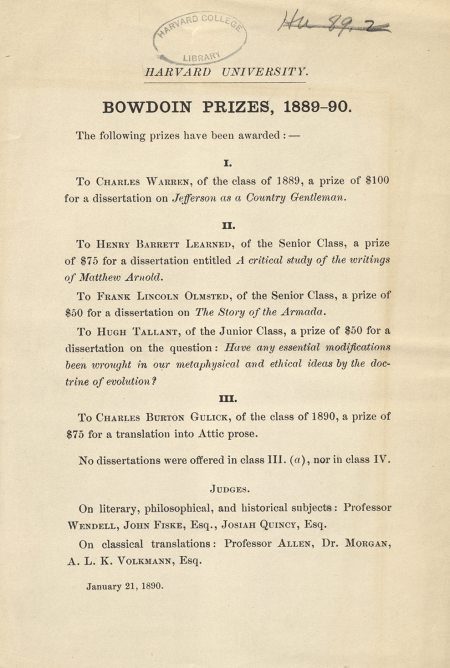

Harvard University Theses, Dissertations, and Prize Papers

The Harvard University Archives ’ collection of theses, dissertations, and prize papers document the wide range of academic research undertaken by Harvard students over the course of the University’s history.

Beyond their value as pieces of original research, these collections document the history of American higher education, chronicling both the growth of Harvard as a major research institution as well as the development of numerous academic fields. They are also an important source of biographical information, offering insight into the academic careers of the authors.

Spanning from the ‘theses and quaestiones’ of the 17th and 18th centuries to the current yearly output of student research, they include both the first Harvard Ph.D. dissertation (by William Byerly, Ph.D . 1873) and the dissertation of the first woman to earn a doctorate from Harvard ( Lorna Myrtle Hodgkinson , Ed.D. 1922).

Other highlights include:

- The collection of Mathematical theses, 1782-1839

- The 1895 Ph.D. dissertation of W.E.B. Du Bois, The suppression of the African slave trade in the United States, 1638-1871

- Ph.D. dissertations of astronomer Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin (Ph.D. 1925) and physicist John Hasbrouck Van Vleck (Ph.D. 1922)

- Undergraduate honors theses of novelist John Updike (A.B. 1954), filmmaker Terrence Malick (A.B. 1966), and U.S. poet laureate Tracy Smith (A.B. 1994)

- Undergraduate prize papers and dissertations of philosophers Ralph Waldo Emerson (A.B. 1821), George Santayana (Ph.D. 1889), and W.V. Quine (Ph.D. 1932)

- Undergraduate honors theses of U.S. President John F. Kennedy (A.B. 1940) and Chief Justice John Roberts (A.B. 1976)

What does a prize-winning thesis look like?

If you're a Harvard undergraduate writing your own thesis, it can be helpful to review recent prize-winning theses. The Harvard University Archives has made available for digital lending all of the Thomas Hoopes Prize winners from the 2019-2021 academic years.

Accessing These Materials

How to access materials at the Harvard University Archives

How to find and request dissertations, in person or virtually

How to find and request undergraduate honors theses

How to find and request Thomas Temple Hoopes Prize papers

How to find and request Bowdoin Prize papers

- email: Email

- Phone number 617-495-2461

Related Collections

Harvard faculty personal and professional archives, harvard student life collections: arts, sports, politics and social life, access materials at the harvard university archives.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to main navigation

Anthropology

Undergraduate

Alumni & Friends

Home / Undergraduate / Anthropology Undergraduate Handbook / Senior Thesis

Senior Thesis

Students considering an independent thesis must arrange for the sponsorship and support of a faculty member before beginning research. An independent senior thesis (not written within a senior seminar) should be based on original research and reflect the student’s understanding of fundamental theories and issues in anthropology. The thesis should be comparable in content, style, and length (generally 25–30 pages) to a professional journal article in its subfield. Students who wish to complete the senior comprehensive requirement through and independent thesis will enroll in a section of ANTH 195S supervised by their thesis sponsor or ANTH 195A , ANTH 195B and ANTH 195C series.

Senior theses have been based on independent ethnographic studies, life histories, and laboratory analyses of archaeological or osteological remains. The department has copies of past Senior Theses available for review in the Ethnographic Library (328 Social Sciences 1). These theses are an excellent resource for students who want to get an idea of the range of topics available for study and the appropriate structure and style of Senior Theses. Students are permitted to review the various theses but they are not to be removed from the Ethnographic Library.

Senior Thesis Process

Students who plan to write an independent Senior Thesis must begin planning well in advance – typically three quarters before they plan to graduate. The Senior Thesis process usually takes about a full academic year and requires that students are highly self-motivated and committed to their thesis topic. Most students spend at least one quarter conducting research and one quarter writing the thesis. The steps for completing a Senior Thesis are described below.

STEP 1: Decide on a topic. This can be developed independently or in conjunction with a faculty member. The Senior Theses in the Ethnographic Library are an excellent resource for students in the process of determining the style, subject, and scope of their research and writing process.

STEP 2: Find a permanent Anthropology faculty member who will sponsor and advise you on your thesis. Your faculty sponsor will supervise your research and writing, evaluate your thesis, and write your final thesis evaluation. Visiting faculty, lecturers and graduate students cannot supervise Senior Thesis projects. The department recommends that you approach a faculty member with whom you have taken a course with in the past and whose research interests are similar to yours.

Most faculty will not supervise students whom they have never supervised in a class, nor will faculty ordinarily work with students who have not already demonstrated superior work in their Anthropology coursework at UCSC. If you intend to do ethnographic fieldwork for your Senior Thesis you should first select a thesis adviser, then plan this research in consultation with your adviser. Do not complete the fieldwork first and then attempt to find an adviser.

STEP 3: If the research for your thesis involves work with either human subjects or with animals, then you MUST talk to your thesis adviser regarding the Human Subjects or CARC applications. Human Subjects and CARC applications are a very important aspect of doing advanced research. Without submitting and gaining approval on a Human Subjects or CARC application students cannot present or publish any findings from thesis research.

STEP 4: Conduct your thesis research. You may elect to take an Independent Study course (ANTH 197, 198 or 199) with your thesis adviser so that you can receive units for your research. Keep in mind that only ONE Independent Study course may be counted towards your Upper- Division major requirements and that all students must complete 10 Upper-Division courses in the major.

STEP 5: Enroll in ANTH 195S and write your thesis. For information on format, rules, and style, talk to your thesis adviser and see the American Anthropological Association’s Style Guide . Anthropology Senior Theses must demonstrate proficiency in the discipline of Anthropology. Your senior thesis must be submitted by the end of the quarter in which you are enrolled for ANTH 195S.

Submitting Your Senior Thesis

The final draft of your senior thesis must be submitted to the department so that the Anthropology Undergraduate Advisor can confirm completion of the senior comprehensive requirment when processing major checklists for graduation.

Below is a link to the Senior Thesis Submission and Evaluation Form. You will be required to provide the following information in the form:

- Student ID #

- Faculty Sponsor for Thesis (Instructor of Record for ANTH 195S or ANTH 195A/B/C)

- Current Quarter and Year

- Thesis Title

- Geographic Region of Research Project

- Summary of Thesis

- Upload of Thesis Document

- If you choose to share your thesis, it will be available to UCSC affiliates logged into their UCSC Google Account

You will not be able to submit the form until all of these fields are completed.

Upon submission of the form, you will automatically be redirected to DocuSign where you will confirm your decision to share the thesis by initial (required). Because the thesis is unable to be transmitted to DocuSign, you will be prompted to upload a copy of your thesis again. The document you upload through DocuSign will be appended to the DocuSign form.

Once you have submitted the DocuSign form, it will be routed to your faculty sponsor who will confirm that the thesis submitted satisfies the senior comprehensive requirement.

If your faculty sponsor determines that the thesis warrants review for honors, they will select another senate faculty member from the Department of Anthropology to review as a second reader. The second reader will confirm whether the thesis merits honors.

Finally, the completed DocuSign document will be routed to the Anthropology Undergraduate Advisor who will process completion of the senior comprehensive requirement.

- Senior Thesis Submission Form

- Undergraduate Program

- Program Learning Outcomes

- Anthropology B.A. Requirements

- Anthropology Minor Requirements

- Earth Sciences/Anthropology Combined Major B.A.

- Submit Senior Thesis

- Declaring the Anthropology Major/Minor

- Transfer Coursework

- Anthropology GE Courses

- Study Abroad

- Experiential Learning

- Independent Studies

- Grade Options

- How to Talk to Faculty

- Undergraduate Awards and Scholarships

- Anthropology Links

- Report an accessibility barrier

- Land Acknowledgment

- Accreditation

Last modified: June 29, 2022 128.114.113.87

- Hirsh Health Sciences

- Webster Veterinary

Dissertations and Theses

Find graduate theses & dissertations, find senior honors theses.

- Resources for writing & submitting a thesis or dissertation

- Dissertations and theses as a research tool

We can help locate sources, create multimedia components, manage your data, cite sources, answer questions about copyright, and more.

Browse the pages of this guide for information on finding graduate theses & dissertations and Senior Honors Theses at Tufts; resources for writing and submitting a thesis or dissertation ; and resources for locating dissertations written by authors at other institutions to use in your research. Get in touch with any questions about this guide or your research.

Search for Tufts master's theses and Ph.D. dissertations in JumboSearch . You’ll find records for both print and digital, and links to the digital version where available.

You can also browse for Tufts theses & dissertations in Dissertations & Theses @ Tufts , with full text available for:

- Most PhD dissertations after 1996

- Most master's theses after 2005

Tufts undergraduate theses that have been submitted in print form are housed in Tufts Archival Research Center (TARC). More information and a list of theses submitted through 2015 is available from TARC.

Theses that have been submitted electronically are available in the Tufts Digital Library . Students began submitting theses electronically in 2010.

To find senior honors theses for a specific department :

- Visit the Advanced Search page in the Tufts Digital Library

- Enter the name of the department in the "Creator Department" search box [note that this is not the "Creator" search box, which comes first. Scroll past that to "Creator Department"]. For longer department names you can use a few keywords instead of entering the whole name.

- Click Search

- On the left side of the results page, open the Collections limit and click "Senior honors theses"

Please note that because undergraduates are not required to submit a copy to TARC, your results won't be a complete set of all honors theses written for a particular department.

- Next: Resources for writing & submitting a thesis or dissertation >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 2:23 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/theses

- Sustainability

‘A really amazing thing’: The 2024 Senior Thesis Exhibition has arrived

By Bates News — Published on April 12, 2024

A week ago, much of the artwork destined for the 2024 Senior Thesis Exhibition in the Bates College Museum of Art could be found in various studio spaces in the Olin Arts Center.

For the eight senior artists, moving their artwork from studio spaces into the museum for a professional exhibition is like having their name up in lights. A visitor approaching the double glass doors of the museum sees the names of all eight seniors displayed in big block letters on the gallery wall facing the doors.

“This moment validates what is possible. And that’s a really amazing thing.” Michel Droge

Whether an artist’s name is in lights on a Broadway marquee or on a Bates museum wall, the effect is the same, says Michel Droge, one of the Bates faculty members helping the seniors display their work in the popular annual exhibition.

“Seeing your name in big letters when you first walk in, or on a poster or postcard, really solidifies the idea that ‘I can do this. I can do this for a living.’ Sometimes people are like, ‘Oh, being an artist is too hard of a life,’ or whatever. This moment validates what is possible. And that’s a really amazing thing.”

This year’s Senior Thesis Exhibition, on display through May 25 , features seniors working in paint, mixed media, digital animation, and installation/performance.

In moving just a few hundred feet from those studios into the museum’s galleries, the artwork, has traveled into a new dimension. It’s now in community — alive and almost begging for conversation.

“Since they moved their work into the museum, we’ve been talking about how everybody’s work is sort of bouncing off each other’s,” says Droge, a visiting assistant professor of art and visual culture. “They saw that when they were working in the studios, but you can really see the conversation happening now.”

Droge pointed to a piece of driftwood on a pedestal, which accents a presentation of oil paintings by George Peck ’24 of Philadelphia that recall a camping trip along the Down East coast. Nearby are oils by Amelia Hawkins ’24 of Sun Valley, Idaho, that capture the phenomenon of forest fires in Idaho.

In some of Hawkins’ oils, “the way the [tree branches] are painted and drawn relates to the driftwood,” says Droge. “Then you look at the driftwood and then look at Emma’s work.” That’s Emma Upton ’24 of Amherst, N.H., who used drawn self-portraits to create mixed-media abstractions. “There’s all sorts of back and forth. And all of the work is transformative.”