School shootings: What we know about them, and what we can do to prevent them

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, robin m. kowalski, ph.d. robin m. kowalski, ph.d. professor, department of psychology - clemson university @cuprof.

January 26, 2022

On the morning of Nov. 30, 2021, a 15-year-old fatally shot four students and injured seven others at his high school in Oakland County, Michigan. It’s just one of the latest tragedies in a long line of the horrific K-12 school shootings now seared into our memories as Americans.

And we have seen that the threat of school shootings, in itself, is enough to severely disrupt schools. In December, a TikTok challenge known as “ National Shoot Up Your School Day ” gained prominence. Although vague and with no clear origin, the challenge warned of possible acts of violence at K-12 schools. In response, some schools nationwide cancelled classes, others stepped up security. Many students stayed home from school that day. (It’s worth noting that no incidents of mass violence ended up occurring.)

What are the problems that appear to underlie school shootings? How can we better respond to students that are in need? If a student does pose a threat and has the means to carry it out, how can members of the school community act to stop it? Getting a better grasp of school shootings, as challenging as it might be, is a clear priority for preventing harm and disruption for kids, staff, and families. This post considers what we know about K-12 school shootings and what we might do going forward to alleviate their harms.

Who is perpetrating school shootings?

As the National Association of School Psychologists says, “There is NO profile of a student who will cause harm.” Indeed, any attempt to develop profiles of school shooters is an ill-advised and potentially dangerous strategy. Profiling risks wrongly including many children who would never consider committing a violent act and wrongly excluding some children who might. However, while an overemphasis on personal warning signs is problematic, there can still be value in identifying certain commonalities behind school shootings. These highlight problems that can be addressed to minimize the occurrence of school shootings, and they can play a pivotal role in helping the school community know when to check in—either with an individual directly or with someone close to them (such as a parent or guidance counselor). Carefully integrating this approach into a broader prevention strategy helps school personnel understand the roots of violent school incidents and assess risks in a way that avoids the recklessness of profiling.

Within this framework of threat assessment, exploring similarities and differences of school shootings—if done responsibly—can be useful to prevention efforts. To that end, I recently published a study with colleagues that examined the extent to which features common to school shootings prior to 2003 were still relevant today. We compared the antecedents of K-12 shootings, college/university shootings, and other mass shootings.

We found that the majority of school shooters are male (95%) and white (61%) –yet many of these individuals feel marginalized. Indeed, almost half of those who perpetrate K-12 shootings report a history of rejection, with many experiencing bullying. One 16-year-old shooter wrote , “I feel rejected, rejected, not so much alone, but rejected. I feel this way because the day-to-day treatment I get usually it’s positive but the negative is like a cut, it doesn’t go away really fast.” Prior to the Parkland shooting, the perpetrator said , “I had enough of being—telling me that I’m an idiot and a dumbass.” A 14-year-old shooter stated in court, “I felt like I wasn’t wanted by anyone, especially my mom. ” These individuals felt rejected and insignificant.

Our study also found that more than half of K-12 shooters have a history of psychological problems (e.g., depression, suicidal ideation, bipolar disorder, and psychotic episodes). The individuals behind the Sandy Hook and Columbine shootings, among others, had been diagnosed with an assortment of psychological conditions. (Of course, the vast majority of children with diagnosed psychological conditions don’t commit an act of mass violence. Indeed, psychologists and psychiatrists have warned that simply blaming mental illness for mass shootings unfairly stigmatizes those with diagnoses and ignores other, potentially more salient factors behind incidents of mass violence.) For some, the long-term rejection is compounded by a more acute rejection experience that immediately precedes the shooting. While K-12 school shooters were less likely than other mass shooters to experience an acute, traumatic event shortly before the shooting, these events are not uncommon.

Many shooters also display a fascination with guns and/or a preoccupation with violence. They play violent video games, watch violent movies, and read books that glorify violence and killing. Several of the shooters showed a particular fascination with Columbine, Hitler, and/or Satanism. They wrote journals or drew images depicting violence and gore. The continued exposure to violence may desensitize individuals to violence and provide ideas that are then copied in the school shootings.

To reiterate, however, there is no true profile of a school shooter. Plenty of people are bullied in middle and high school without entertaining thoughts of shooting classmates. Similarly, making and breaking relationships goes along with high school culture, yet most people who experience a break-up do not think of harming others. Anxiety and depression are common, especially in adolescence, and countless adolescents play violent video games without committing acts of violence in real life. Even if some commonalities are evident, we must recognize their limits.

What can we do?

Understanding the experiences of school shooters can reveal important insights for discerning how to prevent school shootings. So, what might we do about it?

First, the problems that appear to underlie some school shootings, such as bullying and mental-health challenges, need attention—and there’s a lot we can do. School administrators and educators need to implement bullying prevention programs, and they need to pay attention to the mental-health needs of their students. One way to do this is to facilitate “ psychological mattering ” in schools. Students who feel like they matter—that they are important or significant to others—are less likely to feel isolated, ostracized, and alone. They feel confident that there are people to whom they can turn for support. To the extent that mattering is encouraged in schools, bullying should decrease. Typically, we don’t bully people who are important or significant to us.

Second, because most of the perpetrators of K-12 shootings are under the age of 18, they cannot legally acquire guns. In our study , handguns were used in over 91% of the K-12 shootings, and almost half of the shooters stole the gun from a family member. Without guns, there cannot be school shootings. Clearly more needs to be done to keep guns out of the hands of youth in America.

Third, students, staff, and parents must pay attention to explicit signals of an imminent threat. Many shooters leak information about their plans well before the shooting. They may create a video, write in a journal, warn certain classmates not to attend school on a particular day, brag about their plans, or try to enlist others’ help in their plot. Social media has provided a venue for children to disclose their intentions. Yet, students, parents, and educators often ignore or downplay the warning signs of an imminent threat. Students often think their peers are simply expressing threats as a way of garnering attention. Even if the threats are taken seriously, an unwritten code of silence keeps many students from reporting what they see or hear. They don’t want to be a snitch or risk being the target of the would-be shooter’s rage. With this in mind, educators and administrators need to encourage reporting among students—even anonymously—and need to take those reports extremely seriously. Helpful information for teachers, administrators, and parents can be found at SchoolSafety.gov . In addition, Sandy Hook Promise provides information about school violence and useful videos for young people about attending to the warning signs that often accompany school shootings.

Fourth, school leaders should be aware that not every apparent act of prevention is worth the costs. Some people believe that lockdown drills, metal detectors, school resource officers, and the like are useful deterrents to school shootings and school violence more broadly. However, researchers have also demonstrated that they can increase anxiety and fear among students . Students may also become habituated to the drills, failing to recognize the seriousness of an actual threat should it arise. Additionally, most K-12 shooters are students within the school itself. These students are well-versed in the security measures taken by the school to try to deter acts of violence by individuals such as themselves. While few would suggest getting rid of lockdown drills and other security measures, educators and administrators need to be mindful of the rewards versus the costs in their selection of safety measures.

Ultimately, our goal should be creating an environment in which school shootings never occur. This is an ambitious aim, and it will be challenging work. But addressing some key issues, such as mental health, will go a long way toward preventing future tragedies in our schools. As so aptly demonstrated in the Ted Talk, “ I was almost a school shooter ,” by Aaron Stark, making someone feel that they have value and that they matter can go a long way toward altering that individual’s life and, consequently, the lives of others.

Related Content

Kenneth Alonzo Anderson

November 8, 2018

Andre M. Perry

December 4, 2018

K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon

April 15, 2024

Phillip Levine

April 12, 2024

Hannah C. Kistler, Shaun M. Dougherty

April 9, 2024

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Five Facts About Mass Shootings in K-12 Schools

Preventing mass shootings in the United States, particularly those occurring in school settings, is an important priority for families, government leaders and officials, public safety agencies, mental health professionals, educators, and local communities. What does the evidence say about how to detect, prevent, and respond to these tragic events? Here’s what we’ve learned through NIJ-sponsored research: [1]

1. Most people who commit a mass shooting are in crisis leading up to it and are likely to leak their plans to others, presenting opportunities for intervention.

Before their acts of violence, most individuals who carry out a K-12 mass shooting show outward signs of crisis. Through social media and other means, they often publicly broadcast a high degree of personal instability and an inability to cope in their current mental state. Almost all are actively suicidal.

Case studies show that most of these individuals engage in warning behaviors, usually leaking their plans directly to peers or through social media. [2] Yet most leaks of K-12 mass shooting plans are not reported to authorities before the shooting.

Research shows that leaking mass shooting plans is associated with a cry for help. [3] Analyses of case reports from successfully averted K-12 mass shootings point to crisis intervention as a promising strategy for K-12 mass shooting prevention. [4] Programs and strategies found to prevent school shootings and school violence generally could hold promise for preventing school mass shootings as well.

2. Everyone can help prevent school mass shootings.

Most individuals who carry out a K-12 mass shooting are insiders, with some connection to the school they target. Often, they are current or former students.

Research suggests that communities can help prevent school mass shootings by working together to address student crises and trauma, recognizing and reporting threats of violence, and following up consistently.

Two-thirds of foiled plots in all mass shootings (including school mass shootings) are detected through public reporting. Having a mechanism in place to collect information on threats of possible school violence and thwarted attempts is a good first step.

The School Safety Tip Line Toolkit is one resource to consider for developing and implementing a school tip line. [5] The Mass Attacks Defense Toolkit details evidence-based suggestions for recognizing warning signs and creating collaborative systems to follow up consistently in each case. [6] The Averted School Violence Database enables schools to share details about averted school violence incidents and lessons learned that can prevent future acts of violence. [7]

3. Threat assessment is a promising prevention strategy to assess and respond to mass shooting threats, as well as other threats of violence by students.

For schools that adopt threat assessment protocols, school communities are educated to assess threats of violence reported to them. [8] Threat assessment teams, including school officials, mental health personnel, and law enforcement, respond to each threat as warranted by the circumstances. An appropriate response might include referral of a student to mental health professionals, involvement of law enforcement, or both.

Emphasizing the mental health needs of students who pose threats can encourage their student peers to report on those threats without fear of being stigmatized as a “snitch.” In an evaluation study, educating students on this distinction increased their willingness to report threats. [9]

Many educational and public safety experts agree that threat assessment can be a valuable tool. But an ongoing challenge for schools is to implement threat assessment in a manner that minimizes unintended negative consequences. [10]

4. Individuals who commit a school shooting are most likely to obtain a weapon by theft from a family member, indicating a need for more secure firearm storage practices.

In an open-source database study, 80% of individuals who carried out a K-12 mass shooting stole the firearm used in the shooting from a family member. [11] In contrast, those who committed mass shootings outside of schools often purchased guns lawfully (77%).

K-12 mass shootings were more likely to involve the use of a semi-automatic assault weapon than mass shootings in other settings, but handguns were still the most common weapon used in K-12 mass shootings.

Explore more information about the backgrounds, guns, and motivations of individuals who commit mass shootings using The Violence Project interactive database. [12]

5. The overwhelming majority of individuals who commit K-12 mass shootings struggle with various aspects of mental well-being.

Nearly all individuals who carried out a K-12 mass shooting (92%-100%) were found to be suicidal before or during the shooting. [13] Most experienced significant childhood hardship or trauma. Those who commit K-12 mass shootings commonly have histories of antisocial behavior and, in a minority of cases, various forms of psychoses.

Despite the prevalence of mental well-being struggles in these individuals’ life histories, studies suggest that profiling based on mental health does not aid prevention. [14] However, research on common psychological factors associated with K-12 mass shootings, along with other factors that precipitate school violence, can help inform targeted intervention in coordination with crisis intervention, threat assessment, and improved firearm safety practices.

Learn more from these NIJ reports:

- Understanding the Causes of School Violence Using Open Source Data

- A Multi-Level, Multi-Method Investigation of the Psycho-Social Life Histories of Mass Shooters

- The Causes and Consequences of School Violence: A Review

- A Comprehensive School Safety Framework: Report to the Committees on Appropriations

[note 1] National Institute of Justice funding award description, “Student Threat Assessment as a Safe and Supportive Prevention Strategy,” at the Rector & Visitors of the University of Virginia, award number 2014-CK-BX-0004 ; National Institute of Justice funding award description, “Understanding the Causes of School Violence Using Open Source Data,” at the Research Foundation of the City University of New York, award number 2016-CK-BX-0013 ; National Institute of Justice funding award description, “Mass Shooter Database,” at Hamline University, award number 2018-75-CX-0023 , and National Institute of Justice funding award description, “Improving the Understanding of Mass Shooting Plots,” at the RAND Corporation, award number 2019-R2-CX-0003 .

[note 2] Meagan N. Abel, Steven Chermak, and Joshua D. Freilich, “ Pre-Attack Warning Behaviors of 20 Adolescent School Shooters: A Case Study Analysis ,” Crime & Delinquency 68 no. 5 (2022): 786-813.

[note 3] Jillian Peterson et al., “ Communication of Intent To Do Harm Preceding Mass Public Shootings in the United States, 1966 to 2019 ,” JAMA Network Open 4 no. 11 (2021): e2133073.

[note 4] Abel, Chermak, and Freilich, “Pre-Attack Warning Behaviors”; and Jillian Peterson and James Densley, The Violence Project: How To Stop a Mass Shooting Epidemic (New York: Abrams Press, 2021).

[note 5] Michael Planty et al., School Safety Tip Line Toolkit , Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International.

[note 6] RAND Corporation, “ Mass Attacks Defense Toolkit: Preventing Mass Attacks, Saving Lives ."

[note 7] National Police Foundation, Averted School Violence (ASV) Database: 2021 Analysis Update , Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

[note 8] Dewey Cornell and Jennifer Maeng, “ Student Threat Assessment as a Safe and Supportive Prevention Strategy, Final Technical Report ,” Final report to the National Institute of Justice, award number 2014-CK-BX-0004, August 2020, NCJ 255102.

[note 9] Shelby L. Stohlman and Dewey G. Cornell, “ An Online Educational Program To Increase Student Understanding of Threat Assessment ,” Journal of School Heath 89 no. 11 (2019): 899-906.

[note 10] Cornell and Maeng, “Student Threat Assessment.”

[note 11] Jillian Peterson, “ A Multi-Level, Multi-Method Investigation of the Psycho-Social Life Histories of Mass Shooters ,” Final report to the National Institute of Justice, award number 2018-75-CX-0023, September 2021, NCJ 302101.

[note 12] The Violence Project, “ Mass Shooter Database .”

[note 13] Peterson, “A Multi-Level, Multi-Method Investigation.” 14Dewey G. Cornell, “ Threat Assessment as a School Violence Prevention Strategy ,” Criminology & Public Policy 19 no. 1 (2020): 235-252.

[note 14] Dewey G. Cornell, “Threat Assessment as a School Violence Prevention Strategy,” Criminology & Public Policy 19 no. 1 (2020): 235-252, https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12471.

Cite this Article

Read more about:, nij's "five things" series.

Find more titles in NIJ's "Five Things" series .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Uvalde elementary school shooting

Experts say we can prevent school shootings. here's what the research says.

Jeffrey Pierre

Cory Turner

School safety experts have coalesced around a handful of important measures communities and politicians can take to protect students. LA Johnson/NPR hide caption

School safety experts have coalesced around a handful of important measures communities and politicians can take to protect students.

Before the Golden State Warriors took to the court for a pivotal playoff game on Tuesday, Steve Kerr, the team's head coach and a vocal activist, stopped the pre-game interview to say that he didn't walk to talk about basketball. The news of the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, had visibly pushed him to tears. And instead of talking about the game, Kerr wanted to talk about why the shootings were becoming all too common.

27 school shootings have taken place so far this year

"There are 50 senators right now who refuse to vote on H.R. 8, which is a background check rule that the House passed a couple of years ago," Kerr said. "It's been sitting there for two years."

U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., was on the Senate floor, echoing a similar sentiment on Tuesday. "Why are you here," he said to his colleagues, "if not to solve a problem as existential as this."

Can Schools Use Federal Funds To Arm Teachers?

Tuesday's violence follows a familiar pattern of previous school shootings. After every one, there's been a tendency to ask, "How do we prevent the next one?"

For years, school safety experts, and even the U.S. Secret Service, have rallied around some very clear answers. Here's what they say.

It's not a good idea to arm teachers

There's broad consensus that arming teachers is not a good policy. That's according to Matthew Mayer, a professor at Rutgers Graduate School of Education. He's been studying school violence since before Columbine, and he's part of a group of researchers who have published several position papers about why school shootings happen.

In this aerial view, law enforcement works on scene after at shooting Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. Jordan Vonderhaar/Getty Images hide caption

In this aerial view, law enforcement works on scene after at shooting Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas.

Mayer says arming teachers is a bad idea "because it invites numerous disasters and problems, and the chances of it actually helping are so minuscule."

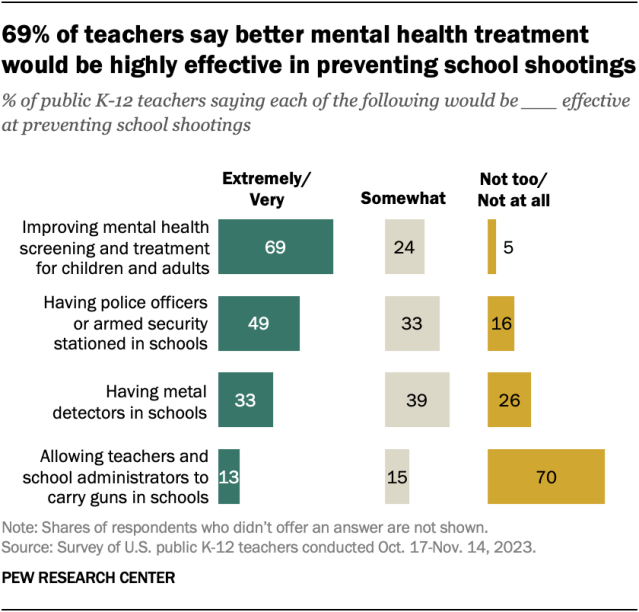

In 2018, a Gallup poll also found that most teachers do not want to carry guns in school, and overwhelmingly favor gun control measures over security steps meant to "harden" schools. When asked which specific measures would be "most effective" at preventing school shootings, 57% of teachers favored universal background checks, and the same number, 57%, also favored banning the sale of semiautomatic weapons such as the one used in the Parkland attack.

Raise age limits for gun ownership

School safety researchers support tightening age limits for gun ownership, from 18 to 21. They say 18 years old is too young to be able to buy a gun; the teenage brain is just too impulsive. And they point out that the school shooters in Parkland, Santa Fe, Newtown, Columbine and Uvalde were all under 21.

School safety researchers also support universal background checks and banning assault-style weapons . But it's not just about how shooters legally acquire firearms. A 2019 report from the Secret Service found that in half the school shootings they studied, the gun used was either readily accessible at home or not meaningfully secured.

Of course, schools don't have control over age limits and gun storage. But there's a lot they can still do.

Schools can support the social and emotional needs of students

A lot of the conversation around making schools safer has centered on hardening schools by adding police officers and metal detectors. But experts say schools should actually focus on softening to support the social and emotional needs of students .

"Our first preventative strategy should be to make sure kids are respected, that they feel connected and belong in schools," says Odis Johnson Jr., of Johns Hopkins University's Center for Safe and Healthy Schools.

Members of the community gather at the City of Uvalde Town Square for a prayer vigil in the wake of a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School. Jordan Vonderhaar/Getty Images hide caption

Members of the community gather at the City of Uvalde Town Square for a prayer vigil in the wake of a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School.

That means building kids' skills around conflict resolution, stress management and empathy for their fellow classmates – skills that can help reduce all sorts of unwanted behaviors, including fighting and bullying.

In its report, the Secret Service found most of the school attackers they studied had been bullied. And while we are still learning about what happened in Uvalde, early reports suggest the shooter there was a regular target of bullying.

Jackie Nowicki has led multiple school safety investigations at the U.S. Government Accountability Office. She and her team have identified some of things schools can do to make their classrooms and hallways feel safer, including "anti-bullying training for staff and teachers, adult supervision, things like hall monitors, and mechanisms to anonymously report hostile behaviors."

Active Shooter Drills May Not Stop A School Shooting — But This Method Could

The Secret Service recommends schools implement what they call a threat assessment model, where trained staff – including an administrator, a school counselor or psychologist, as well as a law enforcement representative – work together to identify and support students in crisis before they hurt others.

There's money to help schools pay for all this

One bit of good news: Because of pandemic federal aid, there's been a big jump in schools' willingness and ability to hire mental health support staff. According to the White House, with the help of federal COVID relief money, schools have seen a 65% increase in social workers, and a 17% increase in counselors.

NPR's Anya Kamenetz contributed to this story.

Did you know we tell audio stories, too? Listen to our podcasts like No Compromise, our Pulitzer-prize winning investigation into the gun rights debate, on Apple Podcasts and Spotify .

- uvalde shooting

Preventing School Shootings

Comprehensive strategies are required to prevent school shootings. The good news is there are proven strategies and approaches ready to be implemented by schools and communities.

School shootings typically involve a mix of suicidal thoughts , despair and anger-- plus access to guns . Schools are the right place to identify students at risk and who are in despair. Often there are signs of distress from the perpetrator that, when ignored, may pave the way to an extreme act of violence.

Begin with School Climate

Building a cohesive and supportive school environment is key to preventing school shootings and traumatic events like other types of mass shootings. In this environment:

- Students feel safe to talk to each other and to staff

- There is mutual trust and respect among students and school staff

- There is on-going dialogue and relationships with family and community members that interact with the school.

- There is adequate support, training and resources for school staff (See “ Recommended Resources ” for examples of programs and resources)

Health Care Settings

"A cohesive and supportive school environment is key to preventing school shootings"

Health care providers can also help in preventing school shootings. They are positioned to identify young patients at risk. At CHOP, primary care and emergency care providers can utilize behavioral health screening tools to identify, assess and refer patients for mental health services to prevent mental illness from being left untreated or ignored. Medical professionals can partner with specific, local mental health providers to establish clear communication, consultation, and referral pathways for at-risk patients.

Addressing Risk of Violence with Programs and Policy

To reduce the risk for individuals with emotional and behavioral challenges to become violent, programs and policies should have the following aims:

- Reduce the day-to-day aggression and the many forms it takes (e.g., physical, social, cyber) within schools and communities. Experts feel that this type of toxic school and community stress, combined with the vulnerabilities of youth, can lead youth with emotional and behavioral problems to be more at risk for future violence, delinquency, and even depression and suicidal acts. Many programs exist. One school-based program developed at CHOP is called PRAISE , which promotes positive school climate in elementary schools.

- Decrease the isolation these children and youth often feel by actively integrating them into peer activities. Schools promoting an inclusive climate in which at-risk youth are also learning better problem-solving and conflict resolution skills are more likely to provide a safe and productive atmosphere.

- Close gaps in mental health services for children with emotional and behavioral problems and to provide a broader continuum of mental health care, including exceptions to privacy protection policies to allow for better communication about the mental health needs of students.

For information on preventing school shootings, click here for sensible policy recommendations to reduce access to guns for youth, especially youth with mental illness.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Public School Trauma Intervention for School Shootings: A National Survey of School Leaders

Associated data.

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not public available due to privacy/confidentiality of research participants.

Trauma intervention in United States’ (U.S.) public schools is varied. The occurrence of public-school shootings across the U.S. elicits questions related to how public schools currently address and provide resources related to trauma for employees and students. A randomized, national survey of public-school teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators was conducted to gather information on public-school preparedness for response to trauma. Findings indicated that only 16.9% of respondents indicated their schools have trauma or crisis plans that address issues related to school shootings. Furthermore, public schools use a variety of strategies to address trauma, but teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators were often unsure about the effectiveness of these trauma interventions in the event of school shootings. Implications for findings suggest methods to enhance next steps in the area of trauma response to school shootings.

1. Introduction

Among public schools in the United States (U.S.), school leaders such as teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators serve on the front lines of student and school needs. Literature indicates that during the typical academic year, school leaders manage school and student needs including but not limited to student academic performance, school activities and events, school district performance, and student mental and psychological health [ 1 ]. The issue of addressing trauma, particularly trauma following school shootings is no exception.

There is no universally accepted definition of a school shooting or mass school shooting and these terms are viewed as different phenomena in this area of research. In fact, there is much controversy on the number and trends in school shootings depending on the definitions used. For instance, Peterson and Densely [ 2 ] indicate there have been 12 mass school shootings since 1989 based on a definition from the Congressional Research Service which states a mass shooting is:

“a multiple homicide incident in which four or more victims are murdered with firearms, not including the offender(s), within one event, and at least some of the murders occurred in a public location(s) in close geographical proximity (e.g., workplace, school, restaurant or other public settings), and the murders are not attributable to any other underlying criminal activity or commonplace circumstance (armed robbery, criminal competition, insurance fraud, argument or romantic triangle) (para 3)”

However, the K-12 school shooting database indicates there have been 177 active school shooting incidents since 1970 based on the following definition: “a gun is brandished, is fired, or a bullet hits school property for any reason, regardless of the number of victims (including zero), time, day of the week, or reason [ 3 ].” Though media coverage of public-school shootings in the U.S. has been amplified in the last 20 years creating the appearance of more frequent and consistent incidents despite school shooting occurrences being statistically rare [ 4 ], trauma in the aftermath of these incidents poses a very real concern for many schools across the nation. Regardless of how a school shooting is defined, the initial impact of widespread fear and panic contributes to subsequent trauma symptoms, which is the primary focus of this research. Thus, the definition of school shooting as it relates to this research is “a gun is brandished, is fired, or a bullet hits school property for any reason, regardless of the number of victims (including zero), time, day of the week, or reason” [ 3 ].

Negative consequences related to school shootings include trauma symptoms such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), posttraumatic stress symptoms, major depression, anxiety, and mood disorders which can be manifested in many ways including mental intrusions, flashbacks, sleep problems and/or nightmares, and hypervigilance [ 5 ], making trauma intervention an important issue for public schools in the U.S. Common methods of trauma intervention in schools have in the past included school-based mental health services on campus [ 6 ]. However, recently, addressing student and employee trauma in schools has increased in awareness and need resulting in more trauma-informed programs and models for schools [ 7 ]. Many schools in the U.S. have adopted trauma-informed strategies to help address student behavior and issues stemming from traumatic experiences [ 8 ]. One common trauma-informed model used in schools is Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), which adds trauma-informed direction and progressive intervention to a holistic support approach for students [ 7 , 9 , 10 ]. However, it is unclear if these strategies are being used in all public schools and what strategies are being used altogether. Additionally, it is unclear if such strategies are sufficient in addressing trauma related to public school shootings.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a national survey of public-school teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators in any U.S. public school to explore the need for resources related to trauma and the role of public schools in managing the psychological effects of school-based traumatic incidents such as school shootings. The following research question was addressed:

- What programming and resources are U.S. public schools providing (or providing access to) for students, public school teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators related to school shootings and/or surviving school shootings?

2. Literature Review

U.S. public schools and education systems have undergone criticism related to the management of trauma or perhaps lack thereof, in the aftermath of public-school shootings [ 11 ]. The effects of trauma related to experiencing a school shooting can put individuals at risk for mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and acute stress disorder as well as sleep disturbances, emotion dysregulation, poorer academic performance and classroom behaviors, lower grade point average, increased school absences, relationship difficulties, decreased work satisfaction, and substance abuse [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Research to examine public school recovery measures related to school shootings has led to possible methods of providing support to students but lacks information regarding ways to support faculty and staff or commonalities in plans and/or programs used among public schools across the U.S. [ 16 ]. Due to the significance of the psychological effects of public-school shootings, research warrants more answers related to how to better manage trauma related to public school shootings. This gap in the literature suggests that barriers may exist for methods to manage the impact of trauma in schools in general, but especially following school shootings.

2.1. Public-School Response to Trauma

Schools are appropriate and practical settings to help students and school employees recover from tragedy as reported by the National Institute of Mental Health: “when violence or disaster affects a whole school or community, teachers and school administrators can play a major role in the immediate recovery process by providing specific structured and semi-structured activities” [ 14 ] (Para 2) [ 18 ]. Instances of school shootings have increased school administrators’ awareness of the need for crisis plans and according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office [ 19 ] approximately 95% of schools nationwide have a crisis plan in place [ 20 ]. However, though “many schools have well-developed emergency management plans, an important piece consistently missing from plans is post-crisis recovery” [ 14 ] (para 5). Following school crises, interventions can range from individual counseling to large debriefing groups and/or assemblies [ 21 ]. However, school leaders (e.g., public school teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators) report that public schools are struggling with adequate responses to trauma in the aftermath of traumatic events such as school shootings [ 9 ]. Despite providing access to mental health resources for students, faculty, and staff members, many report that public schools are missing the mark in providing adequate care related to trauma for those who have experienced school shootings [ 9 ]. “Attention to childhood trauma and the need for trauma-informed care has contributed to the emerging discourse in schools related to teaching practices, school climate, and the delivery of trauma-related in-service and preservice teacher education” [ 22 ] (p.423). This may help address the gap in trauma intervention at public schools in the aftermath of school shootings.

2.2. Trauma-Informed Practices

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network posits that creating a trauma-informed system involves “one in which all parties recognize and respond to the impact of traumatic stress” [ 23 ] (Para1). Trauma-informed care systems can vary from setting to setting. However, these approaches strengthen resilience and protective factors of those impacted by trauma. This mitigates the impact of trauma on other systems (i.e., family, school, etc.), emphasizing continuity of care and collaboration, and maintaining an environment that addresses and minimizes trauma triggers and increases wellness [ 23 ]. Though all these components are important to the trauma-informed response, priorities lie in activities that build meaningful partnerships at the individual and organizational levels and address the intersections of trauma and its compounding impact on traumatized individuals [ 23 ]. The use of trauma-informed care in schools specifically regarding school shootings raises many questions such as how practices may change over time and how practices may vary in schools with shooting history and schools without shooting history. When dealing specifically with school shooting survivors, trauma exposure is, unfortunately, a substantive issue, making trauma-informed care an appropriate intervention tool for public schools to use to address trauma symptoms.

2.3. Trauma-Informed Methods and Practices in Schools

In many states, trauma-informed practice is connected to social and emotional learning, school safety, school discipline, and/or Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) [ 22 ]. Schools may offer resources to teachers and staff members such as toolkits, research or practice briefs, guidebooks, PowerPoint slides, and online training and learning modules [ 22 ]. Many approaches focus on the individual student or teacher–student interaction and how it can be adapted to support student emotional, social, and academic growth following trauma exposure. For a school to be trauma-informed, there needs to be several components and/or foundational principles addressed including building a sense of community, social and emotional connectedness, facilitating knowledge of prevalence and impact of trauma, building capacity of educators and caregivers, empowerment and resiliency, and promoting mindset change by addressing causes of behavior and social justice [ 24 ].

However, implementation of trauma-informed methods at school has been slow to develop across U.S. public schools despite recommendations. Contexts, where trauma-informed practices are most heavily promoted, include high poverty schools, alternative programs, large urban districts, and rural settings [ 22 ]. These trends are disheartening since research indicates that trauma-informed methods can be applied to any program, organization or system that (1) realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths of recovery, (2) recognizes the signs of symptoms of trauma in the clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system, (3) responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and (4) seeks to actively resist re-traumatization [ 25 ]. By these standards, all public schools could benefit from use of trauma-informed practices. Additionally, school shooting incidents have historically occurred in schools that are not associated with high poverty, alternative programs, or large urban districts (where trauma-informed practices are heavily promoted) leaving them vulnerable to inadequate trauma management following a shooting. However, the more pertinent task seems to lie in determining how to implement and evaluate trauma-informed methods in schools that have experienced school shootings and if this is an effective trauma response plan for them.

2.4. Trauma-Informed Methods and Practices in Schools with Shooting History

Trauma-informed supports are, arguably, equally as important for school staff when discussing school shooting scenarios. Application of trauma-informed methods in public schools, however, may be difficult when specifically related to school shootings because schools would need to address the trauma for faculty members in addition to students. Trauma-informed school methods in response to school shootings should consider how such methods will affect teachers and staff members who may be experiencing similar trauma symptoms. One of the nuances of managing trauma in the aftermath of public-school shootings involves attending to the trauma of both students and faculty and staff members [ 9 ]. While trauma-informed school methods are beneficial to students who have experienced trauma, one must question, in scenarios related to public school shootings, if a trauma-informed model that often relies heavily on facilitation from teachers and school staff members is beneficial for their healing and potential trauma symptoms, or how such a model can be adapted so that it is beneficial for all and provides the support needed for faculty/staff. Literature in this area is limited and has yet to address disadvantages or advantages for school faculty and staff administering trauma-informed practices for instances of shared traumatic experiences such as school shootings. Due to the varied methods used by public schools to address trauma and trauma recovery, it is unclear what strategies are being used in schools across the nation, how they relate to school shootings, and how they are perceived by school leaders (e.g., teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators).

The author posed the following research question: What programming and resources are U.S. public schools providing or providing access to for students, public school teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators related to school shootings and/or surviving school shootings? A cross-sectional design approach was used to develop a questionnaire to emphasize description and exploration of trauma response services and resources currently offered in public schools and attitudes towards these services. Prior to conducting this study, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained through Baylor University. A consent statement was presented to participants on the first page of the survey and participants were informed that advancement to the next section of the survey indicated consent. Survey settings were set to ensure that participants were not able to complete the survey more than once. Next, the author analyzed and compiled findings to disseminate among professionals interested in trauma response to public-school shootings.

3.1. Participants

The sampling frame included 360,000 public school teachers, 88,000 administrators, and 58,804 guidance counselors, all of which were obtained from a national marketing email listserv. Upon obtaining contact lists in the sampling frame, 500 individuals from each list of eligible public-school employees (i.e., public school teachers, public school administrators, and public-school guidance counselors) were randomly selected for a total of 1500 individuals. The rationale for this sampling frame is related to Rubin and Babbie’s [ 26 ] estimation of approximately 50% response rate for online surveys and accounts for a sample size large enough (i.e., 750 participants) to provide national estimates for public schools in the U.S. Participants were randomly selected via a random selection tool within the survey software system (i.e., Qualtrics). Initial invitations that included recruitment contact and a link to participate in the survey were sent out to all teachers, administrators, and guidance counselors in the sample. Multiple contacts included the initial formal invitation email, an initial follow-up reminder email 3 days after the initial formal invitation, subsequent follow-up reminder emails at two weeks, four weeks, six weeks, eight weeks, and nine weeks after the initial follow up which included replacement names from prior nonresponse emails. A final thank you letter was sent for those that participated, with a reminder for those who did not participate to do so. Additionally, subsequent contacts included a link to assess for nonresponse bias. All survey responses were anonymous and no identifying information was obtained.

3.2. Assessment and Procedure

The study used an anonymous, online survey to obtain information from participants. The author was not able to identify where any completed questionnaire came from; however, informed consent was connected to the individual’s survey to indicate which surveys would need to be pulled out if participants decided to withdraw from the study. Potential participants were randomly selected from the sampling frame to receive a formal, in-depth invitation letter via their school-related email accounts to complete the anonymous online survey via link. Participants who voluntarily agreed to complete the survey clicked the survey link in their formal invitation which led to the overview of the study describing the study in detail, defining pertinent terms related to the study that were used throughout the survey, and thanking participants for their participation. Participants also reviewed an informed consent prior to completing the survey including potential risks and benefits of the study, anonymity, voluntary participation, protection of human rights, and explanation of their role in the study. Advancement to the next section and completion of the survey indicated consent. Three days after the formal invitation, a follow up email was sent to participants encouraging those that had not participated yet to do so. Following an additional two weeks, another email was sent of a similar nature thanking participants who completed their surveys and encouraging others to participate if they had not. Additional emails were sent at the six week, eight week, and nine week marks for follow up and reminders to complete the survey. Data were collected based on percentage of responses during each wave of reminders. Those whose emails were not working during each wave of contacts were replaced with another name randomly selected from the original sampling frame. To address nonresponse rate bias, a link was provided for those who did not respond to the formal invitation after two emails to assess why survey responses were not provided.

The survey (i.e., the Public-School Trauma Support Assessment) included 25 five-point Likert scale items and 1 open-ended item that were informed by data obtained during a previous study, a five-item PTSD scale for those who had experienced school shootings only, and a demographic section. Some items included examining differences in strategies used among public schools in response to school-based traumatic events and perceived barriers among employees toward implementing a public-school intervention for school-based trauma were from the School Survey on Crime and Safety for Principals [ 27 ]. This survey’s use in the study was based on its use in previous national surveys of public schools by the U.S. Department of Education to measure similar concepts such as school violence, although it focuses on the broader topics of crime and safety and does not address trauma support in public schools. The most recent survey sample in 2016 included approximately 3553 public elementary, middle, and high schools nationwide [ 28 ]. Specifically, the author used eight questions from this survey on topics related to school mental health services, school practices and programs, staff training and practices, and school security staff. Sixteen questions on topics related to parent and community involvement at school, crime incidents, disciplinary problems and actions, and school characteristics from the School Survey on Crime and Safety for Principals were excluded due to being outside of the scope of this study. An additional 18 questions were developed by the author and added to the survey to assess for trauma support services, public school employee perceptions of such services, and differences among strategies that are reported in the literature as being used in public schools to address trauma in students and employees. Participants would, then, identify strategies for public school efforts toward improvement of trauma response to school shootings via questions provided within the survey. The open-ended question was included in the survey for respondents to discuss various strategies used by their schools to reduce trauma symptoms in individuals. The author also requested basic demographic information including age, gender, ethnicity, job title, years of employment in public schools, years of employment in current school district, and number of public schools employed. Participants were expected to complete the survey in approximately 10–15 min. The data collection process lasted for two and a half months.

3.3. Data Analysis

The author calculated effect size using Cohen’s d to determine minimum sample size needed for the study. The results indicated 329 respondents were required to exceed Cohen’s [ 29 ] convention for a large effect ( d = 0.80). Cronbach’s alpha calculation for internal consistency of the survey questions indicated high reliability ( α = 0.88). Expert panel results determined that survey items captured the intended concept of trauma support in schools. SPSS software was used for analysis of survey responses. Basic descriptive analyses (e.g., frequencies, central tendency) provided the percentage of public schools responding to the survey that have a trauma/crisis plan in place. Additional chi square testing was used to compare the attitudes toward public school intervention in the event of school shootings based on respondent’s position at their school (e.g., teacher, guidance counselor, and administrator). Additionally, basic descriptive analyses and axial coding helped to identify themes in public schools’ strategies to reduce trauma symptoms in students and employees for the open-ended survey item. Alpha was set to 0.05. The author reviewed data for the standard assumptions of each test before conducting any analyses.

The total sample included 500 public school teachers, 500 guidance counselors, and 500 administrators. The survey response rate was 27.73%. Survey respondents consisted of 416 (303 identified as women, 72 identified as men, 1 identified gender as not important, and 40 gender nonresponses). Roles included 18 respondents identifying as school administrators, 255 as teachers, 90 as guidance counselors, and 53 not identifying their role. The age of participants ranged from 23 to 67 years old ( M = 38.92, mode = 29). The average length of employment in public schools for participants was 13.14 years (range: 1 year to 53 years of experience; Mdn = 11). A total of 96.8% of respondents identified themselves as full-time public-school employees, 2.8% identified as part-time, and 0.3% did not identify employment status. A total of 59% of survey respondents identified as Caucasian, 24.8% identified as African American, 1.7% identified as other race (e.g., Asian, Middle Eastern), 8.2% identified as Hispanic/Latino, and 5.5% of respondents did not identify a race. Survey respondents represented four regions of the United States: Northeast, Midwest, west, and south. There were 132 respondents from the south region, 85 from the west region, 74 from the Northeast region, 84 from the Midwest region and 41 nonresponses. A total of 73% of survey respondents identified as women and 17.3% as male. An additional 12 respondents completed the separate non-response survey instead of the study survey citing lack of time and concern for the study topic as primary reasons for not completing the study survey.

4.1. Trauma and/or Crisis Intervention Plans

As shown in Table 1 , across all survey respondents, 47.4% percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their school possessed a written trauma and/or crisis plan that describes procedures to be performed in the event of a school shooting. However, only 16.9% were able to agree or strongly agree that their school had a plan that describes trauma intervention strategies to be used in the event of a school shooting. Additionally, 52.5% of respondents were either unsure if their school had a written plan to address school shootings or disagreed altogether that such a plan existed. A total of 83% were unsure or disagreed that their school’s plan included trauma intervention strategies that can be used following a school shooting.

Trauma Intervention Plans.

Additionally, 61% of school administrator respondents confirmed their schools have trauma and/or crisis intervention plans compared with 44% of teacher respondents and 48% of guidance counselor respondents suggesting that administrators may be more likely to be knowledgeable about such plans compared with other respondents (i.e., teachers and guidance counselors).

4.2. Trauma Intervention Strategies in Public Schools

Differences in strategies used among public schools to reduce symptoms of trauma in the event of a school shooting were determined using an open-ended survey question which prompted respondents to identify strategies and/or methods that their school uses to address trauma (i.e., “Please share any strategies that your school uses that may reduce trauma symptoms in students or teachers in the event of a school shooting”). Additionally, other survey questions addressed the use of strategies commonly viewed as beneficial for trauma intervention used in schools such as the presence of a mental health counselor and police officer on campus. Additionally, 86.1% of respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that their school possesses a mental health counselor on campus and 93.6% “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that there is a police officer on their campus.

Some themes emerged from the open-ended survey data regarding trauma intervention. Respondents identified trauma methods within two main themes: prevention and intervention strategies that are used in their schools. Common prevention strategies included peer mentoring and anti-bullying policies and programs. Common intervention strategies included mental health services and specific trauma-informed strategies such as restorative circles. However, it was noted that anti-bullying policies and mental health services appeared to be the most popular strategies mentioned among respondents. Peer mentoring and restorative circles, although mentioned often, were not mentioned as often compared with the aforementioned.

4.3. Attitudes toward Public School Trauma Intervention Following School Shootings

The difference in attitudes toward public school trauma intervention related to school shootings among teachers, administrators, and guidance counselors was assessed via level of agreement based on the following three survey items: (1) My school uses effective methods to reduce trauma symptoms in staff members following a school shooting, (2) My school uses effective methods to reduce trauma symptoms in students following a school shooting, and (3) My school provides enough trauma intervention after a school shooting. Many survey respondents across each position type reported neutral/unsure attitudes toward public school intervention following school shootings (See Figure 1 ). Furthermore, 298 survey respondents were unsure if their school does enough intervention related to school shootings.

Attitudes toward Public School Intervention.

Figure 1 respondent graphs indicating responses across every position type showed a majority of neutral/not sure responses to questions regarding the effectiveness and sufficiency of trauma intervention strategies used in schools for staff members and students.

A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the responses toward public-school trauma intervention strategies based on the respondent’s position at their school. Perception of trauma strategies in public schools was varied among respondents. There was a significant association between respondents’ position at their school and level of agreement regarding effectiveness of trauma intervention in schools for staff members, χ 2 (12, n = 375) = 38.39, p = 0.000). There was also a significant association between respondents’ position at their school and level of agreement regarding effectiveness of trauma intervention used in schools for students, χ 2 (12, n = 375) = 28.48, p = 0.005). Finally, there was a significant association between respondents’ position at their school and level of agreement regarding if their school provides enough trauma intervention following a school shooting χ 2 (12, n = 375) = 24.85, p = 0.016). Specifically, findings indicated that a majority of respondents were unsure if their schools provided effective methods to reduce trauma symptoms in staff members and students.

There was also determined to be a correlation of survey items related to trauma plans and effectiveness of trauma intervention strategies in schools. Specifically, positive responses to survey items about schools having a written plan to address trauma and school shootings were more likely to be associated with positive responses to items related to effectiveness of their school’s trauma strategies, r (373) = 0.520, p < 0.01. Additionally, respondents who confirmed their school used effective methods of trauma intervention in students and staff members were also more likely to select positive responses to the survey question related to preparedness to manage trauma in a student following a school shooting, r (373) = 0.41, p < 0.01.

5. Discussion

This study focused on how public schools currently address trauma on campus and school leaders’ (e.g., guidance counselors, teachers, and administrators) perceptions of these methods. The magnitude of effect was relatively large, and several outcomes offered insight for public schools and school districts to use in future planning for trauma intervention on campus. The overall findings suggest that public schools across the nation use a range of strategies that could potentially be used to address trauma on campus. Specifically, respondents consistently reported a lack of and/or unawareness of written trauma and/or crisis intervention plans in schools. However, many respondents also reported the presence of an on-site mental health counselor. This could suggest many things including, but not limited to, schools perceiving mental health services to be equivalent and/or superior to trauma and/or crisis intervention plans in schools, school employees being more knowledgeable or aware of school mental health services than school trauma plans, or more barriers associated with having trauma and/or crisis plans versus a mental health counselor. Additionally, respondents appeared to be more sure of services that students had access to or would have access to in the event of a school shooting than they were about services for themselves. Overall, trends and correlations in the survey respondent data could provide invaluable information related to how public schools currently address trauma and potential areas of improvement.

5.1. Trauma and/or Crisis Intervention Plans

The presence and/or knowledge of a written plan to address school shootings was shown to be a large indicator in a respondent’s perception of a school’s preparedness for trauma or school shootings. This factor was also a large indicator in the respondent’s individual predicted feelings of self-efficacy and preparedness to help manage student trauma response following a school shooting. This suggests that awareness of a written, formalized plan improves public school employee confidence in the school’s ability to respond to school shootings appropriately. However, in many cases, despite some respondents confirming the presence of a written plan related to school shootings, many of these respondents were either unsure or reported that this plan did not include any specific trauma interventions and/or strategies that should be used following a shooting to address traumatic responses. This pattern of findings was aligned with the predicted direction for all responses suggesting that many schools do not possess a written plan related to procedures following a school shooting and those that do often lack emphasis on trauma intervention. Findings also appeared to lack agreement with previous literature which posits most public schools (approximately 95%) have crisis plans [ 19 , 20 ]. This suggests that the emphasis on survey questions placed on school shootings and trauma intervention may have contributed to this difference and perhaps identifies a gap in existing public-school crisis plans.

5.2. Trauma Intervention Strategies in Public Schools

Many survey respondents mentioned trauma intervention strategies including peer mentoring programs, anti-bullying policies and programs, and trauma-informed practices such as restorative circles. This aligns with current trauma literature which states that all of these interventions are beneficial in some way to schools for prevention and intervention related to school shootings [ 16 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Furthermore, mental health services and access to a police officer on the school’s campus was a common intervention identified by survey respondents. Research indicates that the presence of a school-based mental health counselor improves school climate and other positive outcomes for students, such as school safety and lower rates of suspension and other disciplinary incidents [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. However, research suggests the opposite for the presence of police officers in schools. Specifically, literature suggests that having police in schools has not resulted in safer schools and can result in an increase in student referrals to police and student arrests for low level incidents, particularly with students of color [ 36 , 37 ]. Thus, the presence of both of these professions on a school’s campus could have a significant effect on prevention of traumatic events and reduction in trauma symptoms related to traumatic events.

Overall results aligned with previous literature which states that more schools are focusing on use of trauma-informed strategies [ 22 ]. However, there was little mention of assessment and/or screening used in schools to identify students in need of more intensive supports which literature suggests is a crucial part of trauma intervention [ 8 , 38 , 39 ] and psychological first aid training for school employees which can be complementary to other trauma-informed programs, is designed to be used by anyone after crises occur, and supported by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network and the National Center for PTSD [ 8 , 40 ]. Thus, findings suggest a need for improved access to and knowledge of trauma intervention resources. This gap raises concerns about the implications of the lack of identified services in school crisis plans, support in the aftermath of a school shooting, and consideration of faculty and staff members who may also be experiencing trauma and how they might manage such responses while also support students.

5.3. Attitudes toward Public School Intervention Following School Shootings

Survey respondents were also overwhelmingly unsure of the effectiveness of trauma strategies used in public schools. Findings in this area suggest that school employees often have an unclear perception of trauma strategies used in public schools either due to the lack of strategies used in schools, lack of knowledge of what these strategies are, could be, and how to apply them or inability to determine effectiveness of said trauma strategies. However, when discussing interventions following school shootings, survey respondents appeared to be clear on the services that would be provided to students in the event of a school shooting. Furthermore, they were less clear on the services that would be provided to them in the event of a school shooting. For example, many respondents acknowledged that they were unsure if mental health services would be provided to them in the event of a school shooting and subsequently acknowledged that their school had not made them aware of where they could potentially find resources or access to resources following a school shooting. This suggests an implicit bias and assimilation to the idea that students and their trauma response are the primary concern following a school shooting. However, research suggests that public school employees such as teachers, guidance counselors, and administrators are also vulnerable to experiencing negative effects following school shootings [ 41 ]. Thus, failure to consider faculty and staff trauma and how to manage this is an important factor following school shootings. Implications could include disgruntled school employees, negative attitudes toward the school as an organization, increased risk of mental health related concerns, decreased work satisfaction, increased attrition rates, decreased retention rates, and poor relationships with students.

5.4. Implications

Schools are a logical setting for trauma prevention and intervention services. Many schools attempt to address these issues with school-based mental health services, however, research indicates that these services tend to target aggressive and disruptive behaviors rather than internalized issues such as trauma symptoms [ 16 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. This could prove to be a barrier for crisis incidents such as school shootings. Though incidents of school shootings are rare, considering school trauma responses for such a crisis would enhance knowledge of trauma resources and changes that need to be made to improve existing services. Changes within the public school response to trauma will require diligent and intentional efforts on many levels within the school system. Based on survey responses in this study, public schools would benefit from addressing trauma intervention across micro, mezzo, and macro levels to establish a more comprehensive approach to trauma response. For example, interventions at the micro level may include a critical evaluation of trauma assessment tools used by schools to determine whether the tool reflects the principles of trauma-informed care and are supported by evidence or the implementation of use of such a tool, if one is not already being used. Trauma-informed care and counseling would also be included in micro level interventions. However, research is still needed on best practices for school shooting trauma. Interventions at the mezzo level might include facilitating separate support groups for students and school employees to build safety, collaboration, empowerment, and systems of support [ 20 ]. Finally, interventions at the macro level might include school representatives participating in a trauma or crisis task force in the local community to engage in response efforts and/or advocating with state legislators for access to resources to address school trauma response and its impact on schools and their surrounding communities. Furthermore, trauma-informed models in schools will need to address the widely varied trauma intervention responses among public schools. Trauma literature identifies a variety of trauma-informed methods appropriate for use in schools, however, future research should address the potential benefits of having district, state, or nation-wide recommendations or requirements for such models. Recommendations or requirements should be based on meta-analyses or research conducted with specific trauma-informed models in schools.

5.5. Limitations

This study raises many significant questions for future research. The current research question narrowed the scope of scholarly insight on the topic and though this was the intention to gather foundational research, future research would benefit from broader research inquiries on the topic. The practicalities of providing trauma training to staff such as grants to purchase materials and consultants to adapt resources to a particular school, the impact of using these resources and the resilience they build, the varying needs of students versus school employees following a school shooting, and the effectiveness of trauma-informed practices in school shooting scenarios are all areas for future research consideration. Additionally, this study does not include a comparison of psychometric properties of aforementioned trauma tools and interventions, and thus, cannot contribute to discussion of the superiority of any particular measures. Discrepancies in ratings of effectiveness of trauma intervention strategies across respondents (e.g., administrators, guidance counselors, and teachers) were common. It is unclear, however, how to interpret the lack of group differences in some self-reported outcomes in this study. This pattern of findings may reflect limitations in the assessment measures, in respondent comprehension, or in respondent willingness to disclose information regarding their school. Methodological limitations of this study may include small sample size compared with sample frame and limitations to the randomization process. However, I noted an increase in responses following each reminder email suggesting that a longer data collection period with additional reminder emails would have likely resulted in a larger sample size. The demographics of the sample also indicated disproportionate representations of gender and race in survey respondents as well as the inherent roles and regions of survey respondents potentially having significant differences in their experiences and access to trauma resources and services. Furthermore, differences in response rates between groups (e.g., number of teacher respondents versus administrator respondents) could have led to statistical biases when comparisons were made among groups. Future research may benefit from combining groups with unequal sample sizes for comparisons with less risk for bias. Ultimately, response rates could have been affected by several variables including the roles of the respondent in the school, the region the respondent was in, structure of the respondent’s school day, etc. Unfortunately, the nature of the study offered very little information about those who did not respond or complete the nonresponse survey making determining the extent to which non-respondents are different from respondents difficult. Additionally, schools may be reluctant to invest time and money in trauma intervention for the aftermath of school shootings versus prevention efforts. Despite these limitations, the study suggests that further research in this area is warranted.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study offer insight from public school leaders on how schools are currently addressing trauma in schools including significant gaps in both interventions and research for effectiveness. One glaring topic is the impact of school shooting trauma on staff and faculty who are then providers of care and comfort while managing their own responses even as all of the school requirements continue. This information provides baseline data on public school trauma awareness, trauma intervention, and, in some cases, perception of intervention effectiveness. This knowledge can assist in identifying trends related to addressing trauma in public schools, particularly following school shootings, and determining what needs to be done to create an effective and perhaps systematic response to trauma related to school shootings in public schools. Findings indicate that the lack of trauma response and/or intervention plans that address needs following school shootings in public schools further perpetuates unpreparedness for traumatic events that may occur on or near campus. These challenges exacerbate existing inadequate knowledge of education professionals related to the effects of trauma and how to appropriately respond when it has occurred. Further, the lack of knowledge and/or communication of trauma response and/or intervention plans yields similar consequences.

Overall, the history of public school responses to crises suggests that there is capacity for growth in the area of trauma response. Education professionals have demonstrated commitment to improving trauma response in schools that involve a balance among prevention, intervention, and reaction [ 45 ]. In fact, school professionals may already be laying the groundwork for trauma-informed environments and improved crisis response by promoting effective coping to students through formal instruction in life skills and building rapport and trust with students while modeling appropriate ways of expressing feelings. Many of these tactics would enhance next steps in the area of trauma response to school shootings.

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baylor University (IRB Reference #1414050).

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

US school shootings double in a year to reach historic high

Figures for 2021-22 covering elementary and secondary schools show a total of 327 shootings, 188 of which ended with casualties

Schools in the United States are suffering an alarming rise in shootings, according to new federal data that shows the number of incidents reaching a historic peak for the second year running.

Data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) records that in 2021-22 public and private schools, spanning both elementary and secondary levels, incurred a total of 327 shootings – a record high. The incidents involved a gun being brandished and fired or a bullet hitting school property.

Of the 327 events, chronicled by NCES as part of its annual crime and safety report, 188 ended with casualties, and of those some 57 caused deaths.

The rash of shootings amounts to a doubling of incidents on the year before, which was itself higher than any year since records began 25 years ago. In 2020-21, covering the start of the pandemic, there were a total of 146 school shootings, 93 of which caused casualties (including 43 with deaths).

The number of shootings that led to no deaths or injuries also showed a startling increase. In 2021-22, there were 139 shootings without casualties, more than double the 53 registered the year before.

The rise in recorded shootings is so dramatic between the two most recent years for which figures have been compiled that the NCES warns that the data should be interpreted “with caution”. Yet the data is likely to heighten concern about the safety of American schools, and intensify calls for more rigorous gun controls.

The NCES report shows that public schools across the country have already ramped up extraordinary security measures over the past decade. Some 97% of schools now control access to their premises, 91% use security cameras, and 65% have security staff present at least one day a week.

The proportion of schools that provide mental health assessments to evaluate students for mental health disorders has also risen to more than half.