- Today's Paper

- Most Popular

- Times Topics

- Sunday Book Review

- N.Y. / Region

- Art & Design

Best Sellers

- Real Estate

'Black Hearts'

By jim frederick reviewed by joshua hammer.

Illustration by Paul Sahre and Jonas Beuchert; photograph from “Black Hearts”

A riveting account of the flawed leadership, bad luck and virulent personalities that led to the 2006 murder of an entire Iraqi family by American soldiers.

'So Much for That'

By lionel shriver reviewed by leah hager cohen.

Health care and bank accounts loom large in Lionel Shriver’s multifaceted 10th novel, in which plans, relationships and families are changed by illness.

'Wisdom'

By stephen s. hall reviewed by jim holt.

A science writer addresses the question: What makes a sage?

Bundles of Funnies

By douglas wolk.

New collections of classic comics, including “Peanuts,” “Bloom County” and “Popeye.”

'The Surrendered'

By chang-rae lee reviewed by terrence rafferty.

As death draws near, Chang-rae Lee’s heroine, a Korean War orphan who now lives in New York, sets off for Europe to look for her wayward son.

'Reality Hunger: A Manifesto'

By david shields reviewed by luc sante.

With an assist from others’ quotations, David Shields argues that our deep need for reality is not being met by the old and crumbling models of literature.

'The Man Who Ate His Boots'

By anthony brandt reviewed by sara wheeler.

The boldness and the folly of the explorers who sought the Northwest Passage.

'Holy Warriors'

By jonathan phillips reviewed by eric ormsby.

This “character driven” account of two centuries of religious combat is the best recent history of the Crusades.

'Still Life'

By melissa milgrom reviewed by max watman.

A journalist’s adventures in the world of taxidermy, where she observes the art of incising, skinning, sculpturing and reassembling.

'The Man From Saigon'

By marti leimbach reviewed by elizabeth d. samet.

Vietcong capture a female reporter in this vivid Vietnam War novel.

Fiction Chronicle

By jan stuart.

Novels by Dominick Dunne, Sadie Jones, Melanie Benjamin, Brian Hart and Elizabeth Kostova.

Children’s Books

Children’s Books About the Holocaust

Reviewed by elizabeth devereaux.

A documentary approach to Anne Frank’s life and diary; and a novel about Jewish refugee children during World War II.

'Amelia Earhart'

By sarah stewart taylor reviewed by tanya lee stone.

An entertaining, graphic-novel style account of Amelia Earhart’s stay in Newfoundland before she crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1928.

Children’s Bookshelf

By julie just.

More children’s books reviewed.

Love and Baseball

Illegitimate politics, hardcover fiction, hardcover nonfiction, paperback trade fiction, paperback mass-market fiction, paperback nonfiction, hardcover advice, paperback advice, children's books, graphic books, all the lists », book review features.

Take This Job and Write It

By jennifer schuessler.

Work has become central to most people’s self-conception. Why does fiction have so little to say about it?

Killing by Numbers

By marilyn stasio.

Mystery novels by Jo Nesbo, Cara Black, Simon Lelic and Robert Goddard.

- More Crime Columns

Book Review Podcast

Featuring Jim Frederick, the author of “Black Hearts,” on an Iraqi tragedy; and Luc Sante explaining David Shields’s mind-bending manifesto, “Reality Hunger.”

Up Front: Joshua Hammer

By the editors.

As Newsweek’s Jerusalem bureau chief from 2001 to 2004, Joshua Hammer “covered Iraq extensively, embedding with United States troops as the insurgency spiraled out of control.”

Inside the List

Seth Grahame-Smith’s “Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter” enters the hardcover fiction list at No. 4.

Editors’ Choice

Recently reviewed books of particular interest.

Paperback Row

By elsa dixler.

Paperback books of particular interest.

Crime Columns

The new york times book review: back issues, e-mail the book review, books f.a.q., home delivery, subscribe to the book review.

SEARCH BOOK REVIEWS SINCE 1981:

Times Topics: Featured Authors

- Back to Top

- Copyright 2010 The New York Times Company

- Terms of Service

- Corrections

- Work for Us

Inside the Ordinary

Inside the Ordinary | Reviews

NYT Sunday Book Reviews

The New York Times Sunday Book Review section appears in the weekend edition of the “paper.” It’s the literary high point of some weekends; most reviewers are quite capable authors themselves. At times they are able to focus their talent in ways that crystallize some aspects of the books they review. While not necessarily better than the books themselves, the reviews are bite-size morsels that the busy (or lazy) can readily digest.

- Liesl Schillinger on Michael Ondaatje’s The Cat’s Table

David Gates on Janet Frame’s Towards Another Summer

Tom mccarthy on clancy martin’s how to sell, tom barbash on howard jacobson’s the act of love.

- Chris Hedges on Emmanuel Guibert, Didier Lefevre and Frederic Lemercier’s (tr. by Alexis Siegel) The Photographer

Laura Miller on Walter Kirn’s Lost in the Meritocracy

Jess row on anne michael’s winter vault, jack pendarvis on frederick barthelme’s waveland.

- Robert Sullivan on Eric Sanderson’s Mannahatta

David Orr on Frederick Seidel’s Poems 1959-2009

******************************

Liesl Schillinger on Michael Ondaatje’s The Cat’s Table ( 14 October 2011 )

“Not all the mysteries Ondaatje explores in his account of Mynah’s sea passage — revisited in adulthood from the remove of decades and from another continent — have clear resolutions, nor do they need them. Uncertainty, Ondaatje shows, is the unavoidable human condition, the gel that changes the light on the lens, altering but not spoiling the image. . . ”

“. . it looks ahead to Mary Gaitskill’s sense of a vivid inner ferocity: ‘When Grace studied Philip’s eyes she could feel at the back of her mind the movement of sliding door opening to let out small furry evil-smelling animals with sharp claws and teeth.'”

“. . . she’s overwhelmed by the metastasizing of ordinary comportment.”

“At one point Martin deploys the rhetoric of full-blown Heidegerian phenomenology, having an avuncular figure say to Bobby: “Time, Grandson. . . . A watch puts you in the middle of the stuff of ordinary being.” Quentin’s section of “The Sound and the Fury,” perhaps the greatest of all American novels (or, for that matter, of all novels), begins with an almost identical passage. But there’s a vital difference: reading Faulkner, I’m struck with the exhilarating awareness that immense questions are working themselves out right before my eyes; reading Martin, it’s all too evident that commonplaces, worked out already and elsewhere, are being drafted in, or soldered on, to lend philosophical gravitas to what is, at base, a quite straight-up, noirish moral potboiler.”

“The novel succeeds because, for all his insanity, Felix knows both too much and not enough about his own and Marisa’s emotions.”

Chris Hedges on Emmanuel Guibert, Didier Lefevre and Frederic Lemercier’s (tr. by Alexis Siegel) The Photographer “All narratives of war told through the lens of the combatants cry with them the seduction of violence. But once you cross to the other side, to stand in fear with the helpless and the weak, you confront the moral depravity of industrial slaughter and the scourge that is war itself . . . The disparity between what we are told or what we believe about war and war itself is so vast that those who come back, like Lefevre, are often rendered speechless . . . How do you explain that the very proposition of war as an instrument of virtue is absurd?”

“Like many memoirs [it] combines penetrating shrewdness with remarkable blind spots. . . . He has the satirist’s cruel knack for conjuring and dispatching an individual in a single line, like the ‘computer whiz’ described as having ‘all the characteristics of a bad stutterer without the stutter itself.’ . . . [The memoir] betrays the roots of this skill in a wobbly notion of the self as a void encased in a posture.”

“Their [Anne Michaels and Michael Ondaatje] fiction might be described as an attempt to bring together the practice of the lyric poem — density of language, intense sensory observation, a skilled suspension of time — with the novelist’s brick-by-brick construction of drama in time, and, more important, in history. [They] . . . are not novelists of contemporary life but archivists and re-enactors who use poetic immediacy to make the past present — not as an orderly narrative but as a series of fragments or snapshots linked by a kind of dream logic, a hallucination that is neither entirely past nor present. . . Occasionally, in the midst of all this careful composition, these lovingly burnished surfaces, the howl of a very different kind of novel comes through. . . It shatters its own dreamlike stillness.”

“A book-length fascination and loathing culminates in Vaughn’s rapt litany of all the television he could spend the rest of his life watching in bed: ‘news and sports and those incredible game shows and ‘Lost,’ which seems to have a lot of sex in it, and HGTV, all those house-buying shows, . . . a blown-up building one night and a mother killing her children the next.’ To which Greta, the unlikely voice of reason and the heart of this bittersweet, conciliatory comedy says, ‘Uh, no.'”

Robert Sullivan on Eric W. Sanderson’s Mannahatta

The fact-intense charts, maps and tables offered in abundance here are fascinating, and even kind of sexy. And at the very middle of the book, the two-page spread of Mannahatta in all its primevil glory — the visual denouement of a decade’s research — feels a little like a centerfold.

“. . . he’s an exhilarating and unsettling writer who is very good at saying things that can seem rather bad. When a Seidel poem begins, ‘ The most beautiful power in the world has buttocks ,’ it’s hard to know whether to applaud or shake your head.” . . . ‘This combination of barbarity and grace is one of Seidel’s most remarkable technical achievements; he’s like a violinist who pauses from bowing expertly through Paganini’s Caprice No. 24 to smash his instrument against the wall. [Quoting Siedel’s The Cosmos Trilogy] :

It is time to lose your life, even if it isn’t over. It is time to say goodbye and try to die. It is October .

Starwhisperer

- Many Voices of Marian McPartland Now Silenced A musical voice can refer to a singer like Tony Bennett. Or it can refer to a voice in an orchestra of voices -- like Arturo Sandoval's trumpet. In the case of the late Marian McPartland, several voices that have sung together in perfect harmony have been silenced. It is a big loss in our […]

- Nadeem Aslam: "The Opposite of War is Not Peace" The Blind Man's Garden The full quotation from Nadeem Aslam's The Blind Man's Garden (@AAKnopf): "The opposite of war is not peace but civilization, and civilization is purchased with violence and cold-blooded murder. With war." The New Yorker's "Briefly Noted" reviewer judges the writing to be "visceral but exquisite, emotionally affecting yet unsentimental." An excerpt: "Rohan […]

- Ex-Situ: The Violin Promo for "The Violin" by Anna Clyne and Josh Dorman As part of New York City's River to River Festival, the Original Music Workshop presented "The Violin." The Original Music Workshop describes such events as those that: . . .take place in unexpected spaces, away from the Williamsburg site where OMW is constructing its heralded […]

- Violinist as Orchestra Symbol The 10 June 2013 issue of the New Yorker featured a photograph by Gabriele Stabile of musician Erykah Badu and a violinist. In the periodical's "Goings on About Town," the violinist is unnamed, anonymous, but represents the Brooklyn Philharmonic with whom Badu was to play later in the month.

- Very Short Fiction as Poetry? So suggests the New Yorker's James Wood in a review (pay wall) of Jamie Quatro’s book of short stories (New Yorker 3/11/13). He writes: Short fiction is closer to poetry than to the novel, and very short fiction is even closer. Quatro has a poet’s compound eye for small forms, passing phrases, useful repetitions, fleeting images. […]

Image Credit

Poetryandscience.com.

- Fearful Asymmetry: Melancholies of Knowledge Melancholies of Knowledge is a collection that brings together a snapshot of perspectives near the end of the last century on the role of "literature in the age of science." The post Fearful Asymmetry: Melancholies of Knowledge appeared first on Poetry and Science.

- Chapter IX: The Functions and Future of Poetry A chapter by FSC Northrop published in 1947 sensed a moral imperative for poetry to embrace the reality uncovered by science. The post Chapter IX: The Functions and Future of Poetry appeared first on Poetry and Science.

- The Subjugated Meaning of “Diversity” Jonathan Cole offers a more powerful sense of "diversity" in university education - and what should be done about it. Interviewed by Leonard Lopate on WNYC 2016-01 The post The Subjugated Meaning of “Diversity” appeared first on Poetry and Science.

- Glenmorangie and the New Makers Glenmorangie campaign in 2016-04: An exciting new generation of makers is merging creative ambition with the disciplined rationale of hard science. The post Glenmorangie and the New Makers appeared first on Poetry and Science.

- Science Gallery International SNIP from the Science Gallery International portal: Science Gallery International is a non-profit company headquartered in Dublin and charged with supporting the development of the Global Science Gallery Network. Our misison […] The post Science Gallery International appeared first on Poetry and Science.

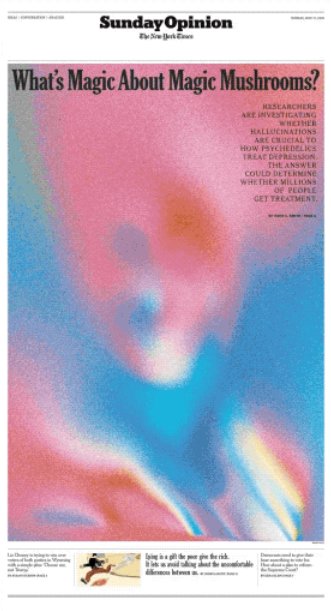

Rachel Poser Is Joining The Times as Sunday Review Editor

Rachel Poser, the deputy editor of Harper’s Magazine, is joining The Times as Sunday Review editor on July 12. Read more in this note from Meeta Agrawal.

I’m excited to announce that Rachel Poser will be our new Sunday Review editor.

The Sunday Review has long been the home of some of Times Opinion’s most ambitious journalism. Rachel will bring her sharp editorial instincts to the section, working closely with the design team to breathe new life into our Sunday section. She will commission and edit long-form pieces and curate the section, drawing from and working alongside the story editors, all with an eye to producing the weekly destination for ideas journalism.

Before coming to the Times, Rachel was the deputy editor of Harper’s Magazine, where she edited reported features, investigations, essays and memoirs. She has been responsible for some of the most-read and celebrated stories in the magazine’s recent history. Over the past year, she has edited a feature about five days in a TikTok collab house , essays about the roles of art and history in our politics, and an unnerving report about the psychological risks of meditation , among many others. Rachel’s own writing has appeared in Harper’s, Mother Jones, The New York Times Book Review and elsewhere. Her profile of classicist Dan-el Padilla Peralta for The New York Times Magazine made waves well beyond the walls of academia.

As we were getting to know Rachel, a former colleague shared, “she is one of the sharpest editors I’ve ever worked with; I remember one issue where she absolutely saved an almost irredeemable draft, and is equally comfortable wielding a red pen on big names and no names.”

Rachel is a Brooklyn native. She holds degrees from Princeton, Oxford and Harvard.

Rachel will start with us on July 12. Please join me in welcoming her to the team.

Explore Further

Mission and values, introducing opinion’s contributing writers and design changes.

We use cookies and similar technologies to recognize your repeat visits and preferences, as well as to measure and analyze traffic. To learn more about cookies, including how to disable them, view our Cookie Policy . By clicking “I Accept” on this banner, you consent to the use of cookies unless you disable them.

- Humor & Entertainment

- Puzzles & Games

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $15.58 $15.58 FREE delivery: Saturday, April 27 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon Sold by: numberonestore

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $8.65

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The New York Times Presents Smarter by Sunday: 52 Weekends of Essential Knowledge for the Curious Mind Hardcover – October 26, 2010

Purchase options and add-ons.

A handy, smaller, and more focused version of our popular New York Times knowledge books―organized by weekends and topic Fell asleep during history class in high school when World War II was covered? Learned the table of elements at one time but have forgotten it since ? Always wondered who really invented the World Wide Web? Here is the book for you, with all the answers you've been looking for: The New York Times Presents Smarter by Sunday is based on the premise that there is a recognizable group of topics in history, literature, science, art, religion, philosophy, politics, and music that educated people should be familiar with today. Over 100 of these have been identified and arranged in a way that they can be studied over a year's time by spending two hours on a topic every weekend.

- Print length 560 pages

- Language English

- Publisher St. Martin's Press

- Publication date October 26, 2010

- Dimensions 5.5 x 1.75 x 8.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0312571348

- ISBN-13 978-0312571344

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

From booklist, about the author.

THE NEW YORK TIMES has the largest circulation of any seven-days-a-week newspapers, and its awardwinning staff of editors, reporters, and critics cover news and people around the world.

Product details

- Publisher : St. Martin's Press; First Edition (October 26, 2010)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 560 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0312571348

- ISBN-13 : 978-0312571344

- Item Weight : 1.35 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.5 x 1.75 x 8.25 inches

- #279 in Business Encyclopedias

- #447 in Sports Encyclopedias

- #1,026 in Trivia (Books)

About the author

New york times.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

The New York Times is reimagining Sunday Review

As of July 17, there is a brand-new section in The New York Times: Sunday Opinion.

Though the name is new, Sunday Opinion has a long history. It was born in 1935 as The News of the Week in Review, a place where Times staffers could offer their analysis of the week’s news. In 2011, the section was given over to the Opinion editors and renamed Sunday Review. Since then, it has been the print home of our finest and most ambitious opinion journalism, where you can find the Sunday columnists Maureen Dowd, Ross Douthat and Jamelle Bouie; the Times editorial board; and incisive guest essays from a wide range of viewpoints.

This redesign completes that transformation. By renaming the section Sunday Opinion, we’re recognizing the role it plays and making that clearer to readers.

Click here to read more.

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here

Other items that may interest you

Google worker says the company is 'silencing our voices' after dozens are fired

Nexstar dropping scripps-owned the cw affiliates in 7 markets, fcc targets pay-tv contract terms deemed harmful to independent programmers, newsweek's ai etiquette: how the publisher defines the rules.

E&P Exlusives

Would reinstating public editors bring back trust in media?

What does the future local website look like part 2, e&p’s 2024 class of news media’s 10 to watch, exploring temple university klein college of media and communication.

- Скидки дня

- Справка и помощь

- Адрес доставки Идет загрузка... Ошибка: повторите попытку ОК

- Продажи

- Список отслеживания Развернуть список отслеживаемых товаров Идет загрузка... Войдите в систему , чтобы просмотреть свои сведения о пользователе

- Краткий обзор

- Недавно просмотренные

- Ставки/предложения

- Список отслеживания

- История покупок

- Купить опять

- Объявления о товарах

- Сохраненные запросы поиска

- Сохраненные продавцы

- Сообщения

- Уведомление

- Развернуть корзину Идет загрузка... Произошла ошибка. Чтобы узнать подробнее, посмотрите корзину.

Oops! Looks like we're having trouble connecting to our server.

Refresh your browser window to try again.

Knife by Salman Rushdie review – a life interrupted

While the author’s account of the 2022 murder attempt is a courageous defence of free speech, it is also shot through with self-regard, making it a sometimes hard book to admire

T welve weeks after the knife attack that almost killed him on 12 August 2022, Salman Rushdie returned to his home in New York. One miracle duly following another, he was fairly soon out and about again: eating (tentatively) and drinking, and generally amazing everyone with his corporeal presence. At a dinner party in Brooklyn, for instance, he saw his old friend Martin Amis , who was then dying of cancer. After this meeting, which would be their last, Amis apparently sent Rushdie an email “so laudatory that I can’t reproduce it all”. What he will tell us, however, is that having expected his fellow writer to be altered, even diminished, by his trauma, Amis was struck by his intactness. Rushdie was, he wrote, entire : “And I thought with amazement, He’s EQUAL to it.”

In his extraordinary new book about the attempt on his life, Rushdie acknowledges that this statement may not have been true – and he’s right, of course. We are no match for horror and violence, just as we’re no match for cancer or any other illness. Such things may only be endured; a body responds (or not) to whatever treatment is available. But in another way, Amis wasn’t wrong. For all that Knife is unsparing of grisly details – when Rushdie describes the initial state of the eye that he lost to his would-be assassin’s blade, lolling on his cheek like “a large soft-boiled egg”, I had to close my eyes for a few moments – what has stayed with me since I finished it has relatively little to do with its author’s flesh and bones. On the page, this could not be anyone but Rushdie. In spirit, he really is, yes, unchanged. The writing is as good as it has ever been, and also (sometimes) as bad. If he appears before us as a courageous person, a true hero of free speech, he is still a bit of a snob and a show-off. The amour propre that was often on display in Joseph Anton , his 2012 memoir of the years when he was in hiding, has not gone away, though perhaps I’m more willing to forgive it now.

When Rushdie’s agent and staunch friend, Andrew Wylie , visited him in hospital after the attack – it happened on stage at the Chautauqua Institution, as Rushdie was about to give a lecture on the importance of keeping writers safe from harm – he told him with huge certainty he would one day write about what had happened. At the time, Rushdie was unconvinced. But Wylie was also right. At a certain point, he realised there was nothing else to be done but this; that such a book would be his way of taking control. He would meet hatred head-on “with art”. And so Knife was born: at once a fever dream and something cooler and more collected. Those moments of violent “intimacy” with his attacker, who has yet to stand trial and whom he prefers not to name (he calls him “the A”), are vividly recalled, as are the days and weeks in hospital afterwards. There is blood. The “armadillo tail” of a ventilator pipe is pushed down a throat. A lung is drained. An eyelid is stitched closed. A bowel cranks to life and a bladder refuses to do so. Nightmares and hallucinations crowd in. Elsewhere, however, Rushdie is by turns puckish (listen to the sound of his “penis begging for mercy”), sentimental (love will conquer all, he thinks, looking at the faces of those at his bedside) and ruminative (revisiting The Satanic Verses , the cause of the fatwa to which his attacker belatedly responded, he notes once again that a person who is afraid of the consequences of what they say cannot be said to be free). There is some light (and wholly justified) score settling: no, those writers who disagreed with him over the honouring of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015 by the writers’ organisation PEN International have still not been in touch, even now. More strangely, Rushdie imagines a series of extended encounters with his attacker, in which he quotes Jodi Picoult at him and accuses him of being an “incel”.

For the reader (or this reader, at least) the effect of these different modes is discombobulating, to put it mildly. I was dizzied by the variety of my responses, pity shading into indignation, and straight back again, and while it’s surely part of Rushdie’s point that he wants Knife to be challenging as well as consolatory – his anger, he tells us, has faded; life is all “gravy” now – I cannot think he intended to go this far. How to explain the moment when he makes a point of telling us how much more his family like his new wife, the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, than “one or two of the women who preceded her”? (This is his fifth marriage.) How to account for the fact that he seems to think it is charming and funny that Griffiths had T-shirts made for him with the word FINALLY emblazoned on them? (Because his son, Milan, and others said “Finally” when they met her.) In the midst of the grace and dignity he displays elsewhere, this seems tin-eared at best.

after newsletter promotion

The reader may be struck, too, by the inadequacy of words in a case like this: a failing Rushdie at one point notes himself (the notion that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger is both a cliche and an untruth, he writes). The book is at its best when it is at its most visceral, its author grappling with the earthly, the horribly tangible. When it moves to a higher, more philosophical plane – “Art is not luxury. It stands at the essence of our humanity, and it asks for no special protection except the right to exist”; “I have always believed that love is a force, that in its most potent form it can move mountains” – it’s in danger of banality. There is an uncomfortable disproportionality between the time Rushdie gives to those writers (Ovid, Lorca) he briefly presses into the service of his thoughts on art and freedom, and the main event of his struggle to breathe, to sit up, to walk; his scars, his disfigurement. People should certainly read this book, and I hope that they will, especially those who currently want for cultural courage; who’ve chosen, in recent times, to stay quiet about so many things. But I must warn you that it isn’t so easy to admire as some are saying. Rushdie’s light is undimmed, and while I celebrate this wholeheartedly in life, in Knife it brings with it a certain dissonance.

- Salman Rushdie

- Observer book of the week

- Autobiography and memoir

Most viewed

Support 110 years of independent journalism.

- The Weekend Essay

Salman Rushdie’s warning bell

His memoir Knife is a defence of free speech for a new age of intolerance. We should listen.

By Nicola Sturgeon

“At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife just after I came out on stage at the amphitheatre in Chautauqua to talk about the importance of keeping writers safe from harm.”

This is the stark opening paragraph of Salman Rushdie’s new book, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder .

It is hard to imagine a book more visceral, personal, vulnerable. Rushdie’s earlier work of memoir, Joseph Anton , was written in the third person. It is inconceivable that this one could have been: “when somebody wounds you 15 times it definitely feels very first-person,” Rushdie writes. “That’s an ‘I’ story.”

Rushdie pours himself, heart and soul, onto the page. It is a book which, in his words, “I’d much rather not have needed to write” – a sentiment that can surprise no one – but reads like the “reckoning” he claims it to be.

Knife is writing as therapy, a healing process for Rushdie’s mind. He uses his art, a tool he wields with customary power and precision, to blunt the impact of the blade that almost ended his life. It takes him to a place of cold indifference to the individual who plunged it into him: “I don’t forgive you. I don’t not forgive you. You are simply irrelevant to me.”

The Saturday Read

Morning call, events and offers, the green transition.

- Administration / Office

- Arts and Culture

- Board Member

- Business / Corporate Services

- Client / Customer Services

- Communications

- Construction, Works, Engineering

- Education, Curriculum and Teaching

- Environment, Conservation and NRM

- Facility / Grounds Management and Maintenance

- Finance Management

- Health - Medical and Nursing Management

- HR, Training and Organisational Development

- Information and Communications Technology

- Information Services, Statistics, Records, Archives

- Infrastructure Management - Transport, Utilities

- Legal Officers and Practitioners

- Librarians and Library Management

- OH&S, Risk Management

- Operations Management

- Planning, Policy, Strategy

- Printing, Design, Publishing, Web

- Projects, Programs and Advisors

- Property, Assets and Fleet Management

- Public Relations and Media

- Purchasing and Procurement

- Quality Management

- Science and Technical Research and Development

- Security and Law Enforcement

- Service Delivery

- Sport and Recreation

- Travel, Accommodation, Tourism

- Wellbeing, Community / Social Services

Writing it, Rushdie explains, was a “way of taking ownership of what happened, making it mine – making it my work. Which is a thing I know how to do. Dealing with a murder attack is not a thing I know how to do. A book about an attempted murder might be a way for the almost-murderee to come to grips with the event.”

It is, first and foremost, a book about the sudden, brutal and very nearly successful attempt on his life. No detail is spared in the description of the attack, the pain of his injuries or the indignities they inflicted on him – “in the presence of serious injuries, your body’s privacy ceases to exist… You surrender the captaincy of your ship, so that it won’t sink.” He tells of a long recovery which will always be incomplete. The stab wound to his right eye, “the cruellest blow”, was so deep that the optic nerve was severed, “which meant there would be no possibility of saving the vision. It was gone.”

What struck me most in the early pages was Rushdie’s immediate sense of the inevitable. His first thought when he registered the attacker rushing towards him was, “So it’s you. Here you are.” Thirty years under the threat of death – the fatwa ordered against him in 1989, following the publication of The Satanic Verses – must do that to the strongest spirit.

And yet he writes movingly about having made the conscious decision 20 years earlier no longer to live in the shadow of fear, to escape the oppression of round-the-clock security, and “remake a life of freedom”. In one of the most heartbreaking parts of the book, he talks of achieving freedom “by living like a free man”. The attack may not have ended his life, but it cruelly robbed him of his liberty all over again.

He is haunted by premonition. A few nights before he is stabbed, he dreams of being attacked by a man with a spear. Shifting into the third person, he describes looking at the moon the night before his world changed forever, feeling happy, in love, pleased at having just completed his latest novel. His “life feels good. But we know what he doesn’t know… the happy man by the lake is in mortal danger.” Rushdie is deliberately deploying – so he tells us – the literary device of foreshadowing. In his case, however, it is not his future rushing towards him, but his past: “a masked man with a knife, seeking to carry out a death order from three decades ago… The revenant past, seeking to drag me back in time.”

There is a hint of guilt in the pages, too. Had his insistence on living a carefree life been foolish? In short, did he bring it on himself? As his healing progressed, he was able to reject this notion, though the effort required to do so is discernible. He believes that “we would not be who we are today without the calamities of our yesterdays”, concluding that “to regret what your life has been is the true folly”.

Rushdie also reveals a deep hurt – indeed, he seems surprised to find it still lurking within – caused by those of his peers who failed to stand with him when the fatwa was declared: “Many prominent and non-Muslim people had joined forces with the Islamist attack to say what a bad person I was, John Berger, Germaine Greer, President Jimmy Carter, Roald Dahl and various British Tory grandees.” He writes: “For many years I felt obliged to defend the text of ‘that’ novel and also the character of its author.” By contrast, the outpouring of love and solidarity that flowed to him in the wake of the 2022 attack gave him the strength he needed to recover.

This is a point we should all reflect on, with some shame. It is clear that he sees the response by some to the fatwa not just as a betrayal of himself, but also of the principle of free speech, which he defends with every word he writes. Rushdie argues that the abandonment by progressive forces of the right of individual free speech in favour of the protection of the sensibilities of vulnerable groups has allowed its weaponisation by the far right – it has become “a kind of freedom for bigotry”. In the midst of our modern-day debates about the rights and limits of free speech, we should pay attention to his words.

Rushdie’s memoir, then, is about so much more than the attempted murder of its writer. It is a deep reflection on the transience of happiness, and the fragility of life. It is a celebration of the power – and necessity – of art as the medium through we which we can, and must, make sense of the world and fight back against the worst of human nature. It is an ode to the resilience of the human spirit at its best, the triumph – however clichéd it may seem – of love over hate, and a clarion call of defiance.

As he lay on the floor, bleeding from 15 stab wounds, he was preparing for death – “It was probable that I was dying” – and yet he made a conscious decision to live, to will into being a future “on whose existence that inner part of me was insisting with all the will it possessed”.

This book represents a solitary journey of healing, but it is also a meditation on the troubled times we live in. For Rushdie, writing it was an act of necessity, of personal survival – but through his experience he offers us a clarity that is all too rare.

He reflects on the features of an age in which social media distorts our reality and in which privacy is surrendered. “Something strange has happened to the idea of privacy in our surreal time,” he writes. “It appears to have become… a valueless quality – actually undesirable. If a thing is not made public, it doesn’t really exist.”

Rushdie understands, better than most, the corrosive power of hate. He is excoriating about any religion which seeks to impose a system of belief on those who do not wish to believe: “I have no issue with religion when it occupies this private space… But when religion becomes politicised, even weaponised, then it is everybody’s business, because of its capacity for harm.”

And from the experience of living under a religiously imposed death sentence for 30 years, he understands better than most the demonisation of those we disagree with, a phenomenon all too prevalent today: “I know it is possible to construct an image of a man, a second self, that bears very little resemblance to the first self, but this second self gains credibility because it is repeated over and over again.” There will be few public figures who won’t recognise the dissonance, and danger, of constantly absorbing a version of yourself that is at odds with what and who you feel yourself to be.

It is this observation that ties Rushdie’s past experience to the present. What is cancel culture, after all, if not a modern-day – though obviously less extreme – “fatwa” on those we disagree with? What was exceptional 30 years ago is today commonplace. Again, Rushdie is forcing us, through the lens of his own experience, to confront some deeply uncomfortable truths.

For all the many pressing issues it engages with, one of the most remarkable things about this book is the paucity of anger. There is the sense on almost every page that Rushdie wants any energy he might expend on anger to be invested instead on making the most of his “second shot at life”. In place of anger is a quest to make sense of the senseless. He does not seek to excuse – quite the reverse. He obliterates, with reason and the power of his intellect, the warped logic of the coward who tried to murder him. It is an approach that emasculates his would-be assassin much more effectively than any amount of rage.

In the process of writing this profoundly life-affirming memoir, it is clear that Salman Rushdie has found his own peace. No one deserves it more. For the rest of us, though, his book should have the opposite effect. It should shake us from our complacencies. It should renew our resolve to confront and defeat the forces that led a young man to plunge a knife into an artist. Rushdie has done us a great service in writing this book. It is up to us now to heed its message.

Purchasing a book may earn the NS a commission from Bookshop.org, who support independent bookshops

[See also: Lessons from The World of Yesterday ]

Content from our partners

Unlocking the potential of a national asset, St Pancras International

Time for Labour to turn the tide on children’s health

How can we deliver better rail journeys for customers?

What’s the point of Liz Truss?

Peter Frankopan Q&A: “If you want to write good history, read lots of novels”

Weighing the options in a country where nothing works any more

- OH&S, Risk Management

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Reviews, essays, best sellers and children's books coverage from The New York Times Book Review.

Philip Pullman is against a religion that puts the spirit above human life. There are plenty of bullies on the prowl in these reassuring storybooks, but the pint-size protagonists always manage to triumph. Regarding reviews of "Isadora: A Sensational Life" and "The Healing Wound" and the essay "Expecting the Worst."

Editors' Choice / Staff Picks From the Book Review. 5 KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON, Paperback Row. Inside the List. OUR ANCIENT FAITH Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment. AMERICA LAST The Right's Century- Long Romance With Foreign Dictators. An Appreciation. Previous issue date: The New York Times - Book Review - April 07, 2024

For Caleb Carr, Salvation Arrived on Little Cat's Feet. As he struggled with writing and illness, the "Alienist" author found comfort in the feline companions he recalls in a new memoir ...

LETTERS TO GWEN JOHN, by Celia Paul. (New York Review Books, $29.95.) Paul's haunting memoir takes the form of correspondence with a fellow painter she never knew: Gwen John, who died in 1939 ...

0028-7806. The New York Times Book Review ( NYTBR) is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of The New York Times in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely read book review publications in the industry. [2] The magazine's offices are located near Times Square in ...

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race. Stephen King, who has ...

The blade went in all the way to the optic nerve, which meant there would be no possibility of saving the vision. It was gone. As bad as this was, he had been fortunate. A doctor says, "You're ...

Find book reviews & news from the Sunday Book Review on new books, best-seller lists, fiction, non-fiction, literature, children's books, hardcover & paperbacks. ... Get The New York Times Book Review before it appears online every Friday. Sign up for the email newsletter here: SEARCH BOOK REVIEWS SINCE 1981: Times Topics: Featured Authors ...

The New York Times Book Review: Back Issues. Good Steiner, Bad Steiner. Frames of Mind. Find book reviews & news from the Sunday Book Review on new books, best-seller lists, fiction, non-fiction, literature, children's books, hardcover & paperbacks.

Find book reviews & news from the Sunday Book Review on new books, best-seller lists, fiction, non-fiction, literature, children's books, hardcover & paperbacks. ... The New York Times Book Review: Back Issues. Complete contents of the Book Review since 1997. Help. Books F.A.Q.

The New York Times - Book Review Now you can read The New York Times - Book Review anytime, anywhere. The New York Times - Book Review is available to you at home or at work, and is the same edition as the printed copy available at the newsstand. Sections and supplements are laid out just as in the print edition, but complemented by a variety of digital tools which enhance the printed ...

Reviews, essays, best sellers and children's books coverage from The New York Times Book Review.

Find book reviews & news from the Sunday Book Review on new books, best-seller lists, fiction, non-fiction, literature, children's books, hardcover & paperbacks.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, The New York Times Book Review is operating remotely and will accept physical submissions by request only. If you wish to submit a book for review consideration, please email a PDF of the galley at least three months prior to scheduled publication to [email protected]. . Include the publication date and any related press materials, along with links to ...

The New York Times Replica Edition

O.J. and the Monster Jealousy. I always thought of the Simpson case as a great American tragedy, with its echoes of "Othello.". Opinion essays and news analysis from New York Times Opinion ...

Deion Sanders Still Believes in 'The Little Engine That Could'. That kids' classic "completely changed my life," says the former football star, now the University of Colorado's ...

The New York Times Sunday Book Review section appears in the weekend edition of the "paper." It's the literary high point of some weekends; most reviewers are quite capable authors themselves. At times they are able to focus their talent in ways that crystallize some aspects of the books they review. While not necessarily better than the ...

Rachel Poser, the deputy editor of Harper's Magazine, is joining The Times as Sunday Review editor on July 12. Read more in this note from Meeta Agrawal. I'm excited to announce that Rachel Poser will be our new Sunday Review editor. The Sunday Review has long been the home of some of Times Opinion's most ambitious journalism.

Here is the book for you, with all the answers you've been looking for: The New York Times Presents Smarter by Sunday is based on the premise that there is a recognizable group of topics in history, literature, science, art, religion, philosophy, politics, and music that educated people should be familiar with today. Over 100 of these have been ...

As of July 17, there is a brand-new section in The New York Times: Sunday Opinion. Though the name is new, Sunday Opinion has a long history. It was born in 1935 as The News of the Week in Review, a place where Times staffers could offer their analysis of the week's news. In 2011, the section was given over to the Opinion editors and renamed ...

The New York Times Book Review (NYTBR) is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of The New York Times in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely read book review publications in the industry. The magazine's offices are located near Times Square in New York City.

Find many great new & used options and get the best deals for The New York Times Supersized Book of Sunday Crosswords: 500 Puzzles [New York T at the best online prices at eBay! Free shipping for many products! ... Product ratings and reviews. Learn more. Write a review. 4.6. 38 product ratings. 5. 31 users rated this 5 out of 5 stars. 31. 4. 2 ...

T welve weeks after the knife attack that almost killed him on 12 August 2022, Salman Rushdie returned to his home in New York. One miracle duly following another, he was fairly soon out and about ...

By Nicola Sturgeon. "At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife just after I came out on stage at the amphitheatre in Chautauqua to talk about the importance of keeping writers safe from harm.". This is the stark opening paragraph of ...