How to Analyze a Primary Source

When you analyze a primary source, you are undertaking the most important job of the historian. There is no better way to understand events in the past than by examining the sources — whether journals, newspaper articles, letters, court case records, novels, artworks, music or autobiographies — that people from that period left behind.

Each historian, including you, will approach a source with a different set of experiences and skills, and will therefore interpret the document differently. Remember that there is no one right interpretation. However, if you do not do a careful and thorough job, you might arrive at a wrong interpretation.

In order to analyze a primary source you need information about two things: the document itself, and the era from which it comes. You can base your information about the time period on the readings you do in class and on lectures. On your own you need to think about the document itself. The following questions may be helpful to you as you begin to analyze the sources:

- Look at the physical nature of your source. This is particularly important and powerful if you are dealing with an original source (i.e., an actual old letter, rather than a transcribed and published version of the same letter). What can you learn from the form of the source? (Was it written on fancy paper in elegant handwriting, or on scrap-paper, scribbled in pencil?) What does this tell you?

- Think about the purpose of the source. What was the author’s message or argument? What was he/she trying to get across? Is the message explicit, or are there implicit messages as well?

- How does the author try to get the message across? What methods does he/she use?

- What do you know about the author? Race, sex, class, occupation, religion, age, region, political beliefs? Does any of this matter? How?

- Who constituted the intended audience? Was this source meant for one person’s eyes, or for the public? How does that affect the source?

- What can a careful reading of the text (even if it is an object) tell you? How does the language work? What are the important metaphors or symbols? What can the author’s choice of words tell you? What about the silences — what does the author choose NOT to talk about?

Now you can evaluate the source as historical evidence.

- Is it prescriptive — telling you what people thought should happen — or descriptive — telling you what people thought did happen?

- Does it describe ideology and/or behavior?

- Does it tell you about the beliefs/actions of the elite, or of “ordinary” people? From whose perspective?

- What historical questions can you answer using this source? What are the benefits of using this kind of source?

- What questions can this source NOT help you answer? What are the limitations of this type of source?

- If we have read other historians’ interpretations of this source or sources like this one, how does your analysis fit with theirs? In your opinion, does this source support or challenge their argument?

Remember, you cannot address each and every one of these questions in your presentation or in your paper, and I wouldn’t want you to. You need to be selective.

– Molly Ladd-Taylor, Annette Igra, Rachel Seidman, and others

Primary Source Research

- Primary Source Databases: Subcollections Lists

- Search Strategies

Analyzing Primary Sources

Teaching resources.

- Citing Primary Sources

- Primary Sources by Subject

- Rowan University Archives & Special Collections

When you analyze a primary source, you are undertaking the most important job of the historian. There is no better way to understand past events than by examining the sources that people from that period left behind (e.g., whether journals, newspaper articles, letters, court case records, novels, artworks, music or autobiographies).

Each historian, including you, will approach a source with a different set of experiences and skills, and will therefore interpret the document differently. While there is no one right interpretation, interpretations should still be supported by evidence and analysis. If you do not do a careful and thorough analysis, you might arrive at a wrong interpretation.

In order to analyze a primary source you need information about two things: the document itself and the era from which it comes. You can base your knowledge on class materials and other credible sources. You'll also need to analyze the document itself. The following questions may be helpful for your analysis of the document as an artifact and as a source of historical evidence.

Initial Analysis

- What is the physical nature of your source? This is particularly important if you are dealing with an original source (i.e., an actual old letter, rather than a transcribed and published version of the same letter). What can you learn from the form of the source? (Was it written on fancy paper in elegant handwriting, written on scrap-paper, scribbled in pencil?) What does this tell you?

- What is the source's purpose? What was the author's message or argument? What were they trying to get across? Is the message explicit? Are there implicit messages as well?

- How does the author try to convey their message? What methods do they use?

- What do you know about the author? This might include, for example, race, ethnicity, sex, class, occupation, religion, age, region, or political beliefs? Does any of this matter? How?

- Who was or is the intended audience? Was this source meant for one person's eyes, or for the public? How does that affect the source?

- What can a careful reading of the text/artifact tell you? How do language and word choice work? Are important metaphors or symbols used? What about the silences--what does the author choose NOT to talk about?

Evaluating the Source as Historical Evidence

You'll also want to evaluate how credible the source is and what it tells you about the given historical moment.

- Is it prescriptive--telling you what people thought should happen--or descriptive--telling you what people thought did happen?

- Does it describe ideology and/or behavior?

- Does it tell you about the beliefs/actions of the elite, or of "ordinary" people? From whose perspective?

- What historical questions can you answer using this source? What are the benefits of using this kind of source?

- What questions can this source NOT help you answer? What are the limitations of this type of source?

- If we have read other historians' interpretations of this source or sources like this one, how does your analysis fit with theirs? In your opinion, does this source support or challenge their argument?

Remember, you cannot address each and every one of these questions in your presentation or in your paper, and I wouldn't want you to. You need to be selective.

Credit: Thank you to Carleton College's History Department for permission to adapt their resource " How to Analyze a Primary Source ." (Minor additions or changes made to the original text). Original text created by Molly Ladd-Taylor, Annette Igra, Rachel Seidman, and others.

- Document Analysis Worksheets (National Archives) Worksheets for analyzing various types of primary sources. Apply 4 key principles: "1. Meet the document. 2. Observe its parts. 3. Try to make sense of it. 4. Use it as historical evidence."

- Making Sense of Evidence (History Matters) Strategies for analyzing various types of online primary sources (oral histories, films, maps, etc.).

- Teacher's Guide: Analyzing Primary Sources (PDF) (Library of Congress) Applies three key steps to analyzing primary sources (observe, reflect, question). Includes sample question prompts.

- << Previous: Search Strategies

- Next: Citing Primary Sources >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 2:43 PM

- URL: https://libguides.rowan.edu/primarysourceresearch

History 300: A Guide to Research: Analyzing Primary Sources

- Getting Started

- Reference/Tertiary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Primary Sources

- Phillips Academy Archives Collections This link opens in a new window

- Addison Gallery Resources

- Requesting Items Outside the OWHL

- Historical Eras / Time Periods

- Indian Removal Act of 1830 and its after-effects in the US

- Labor and Industrialism in the US

- Personalities from Early America through the Civil War

- Progressive Reformers

- U.S. Imperialism

- World War II

- Cold War in the US

- US History through a Different Lens This link opens in a new window

- Constitution Essay

- Topics & Research Questions

- Evaluating Sources

- Reading Scholarly Articles This link opens in a new window

- Analyzing Primary Sources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Writing Strategies (Harvard University) This link opens in a new window

- Historiography

Questions to Ask About Your Source

Meet the primary source..

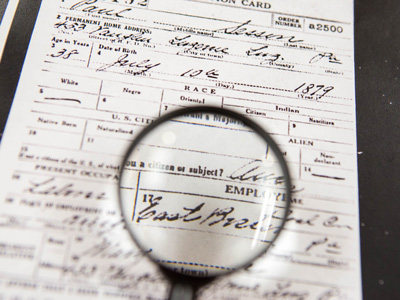

- What type of primary source is this? (letter, report, photograph, artifact, map, poster, cartoon, video, sound recording, artwork, etc.)

- What do you notice first? Describe it as if you were explaining it to someone who can’t see it.

Observe its parts.

- Who made it? Can you tell if one person created it? Or was it a group, like an organization?

- When was it made?

- What personal or specific information is included about the person or group who made it?

- Who is the intended audience?

Try to make sense of it.

- What do you know about this primary source or where it comes from that helps you understand it?

- What else was happening at the time this was created? How does that context (or background information) help you understand why it was created?

- List details that reveal the creator’s perspective. What clues can you find about their background or point of view?

- Why was this primary source made?

Use it as historical evidence.

- This is one piece of a larger story. What questions do you have that this primary source doesn’t answer?

- What evidence does the creator present that you should “fact check” (verify as true)? Do other sources support or contradict this?

- This primary source shows one perspective on this topic. What other perspectives should you get?

- What perspective do you bring to this topic and source? How does your background and the time in which you live affect your perspective?

In order to analyze a primary source you need information about two things: the document itself, and the era from which it comes. You can base your information about the time period on the readings you do in class and tertiary/secondary sources you find during your research. On your own you need to think about the document itself. The following questions may be helpful to you as you begin to analyze the sources:

- Look at the physical nature of your source . This is particularly important and powerful if you are dealing with an original source (i.e., an actual old letter, rather than a transcribed and published version of the same letter). What can you learn from the form of the source? (Was it written on fancy paper in elegant handwriting, or on scrap-paper, scribbled in pencil?) What does this tell you?

- Think about the purpose of the source . What was the author’s message or argument? What were they trying to get across? Is the message explicit, or are there implicit messages as well?

- How does the author try to get the message across? What methods do they use?

- What do you know about the author? Race, gender, class, occupation, religion, age, region, political beliefs? Does any of this matter? How?

- Who constituted the intended audience? Was this source meant for one person’s eyes, or for the public? How does that affect the source?

- What can a careful reading of the text (even if it is an object) tell you? How does the language work? What are the important metaphors or symbols? What can the author’s choice of words tell you? What about the silences — what does the author choose NOT to talk about?

Now you can evaluate the source as historical evidence.

- Is it prescriptive — telling you what people thought should happen — or descriptive — telling you what people thought did happen?

- Does it describe ideology and/or behavior?

- Does it tell you about the beliefs/actions of the elite, or of “ordinary” people? From whose perspective?

- What historical questions can you answer using this source? What are the benefits of using this kind of source?

- What questions can this source NOT help you answer? What are the limitations of this type of source?

- If you have read other historians’ interpretations of this source or sources like this one, how does your analysis fit with theirs? In your opinion, does this source support or challenge their argument?

Adapted from "How to Analyze a Primary Source," Carleton College

Analysis Worksheets

National archives document analysis worksheets.

- Written Document

- Sound Recording

- << Previous: Reading Scholarly Articles

- Next: Annotated Bibliography >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 2:23 PM

- URL: https://owhlguides.andover.edu/hss300

- Source Criticism

How to analyse historical sources

When using sources for evidence, you need to be able to demonstrate your knowledge of them by identifying their historical background.

To do this, you need to analyse your sources.

What is 'source analysis'?

Analysis is the ability to demonstrate an understanding of the elements that contributed to the creation of a historical source.

It answers the question: 'Why does this source exist in its current form?'

There are six analysis skills that you need to master:

How do you analyse a source?

In order to demonstrate a knowledge of the six analysis skills, you need to do two things:

- Carefully read the source to find information that is explicit and implicit

- Conduct background research about the creator of the source

After completing these two steps, you can begin to show your understanding about the six features of historical sources.

Based upon what you found in your reading and background research, answer the following questions for each of the six analysis skills.

Watch a video explanation on the History Skills YouTube channel:

Watch on YouTube

How do you write an analysis paragraph?

Once you have been able to answer all of the question above, you are ready to demonstrate your complete source analysis.

An analysis paragraph should demonstrate your awareness of all six analysis skills in a short paragraph.

This letter was written by John Smith to record the events of the battle for his family at home . It is from the perspective of an Australian soldier who had just experienced the Gallipoli landing on the 25th April, 1915 , and specifically mentions “running like hell” for survival.

What do you do with your analysis?

Your source analysis becomes a vital step in your ability to evaluate your sources in your assessment pieces .

This is most important in written essays , source investigations and short response exams .

You will use different parts of your analysis to help justify a source's usefulness and reliability .

Test your learning

No personal information is collected as part of this quiz. Only the selected responses to the questions are recorded.

Additional resources

What do you need help with, download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

HIS 132 - American History II: Primary Sources for HIS132 Assignment

- Find Articles

- American History 2 Project

- American History Wargame

- Gilded Age/Robber Barons

- World War 1 Resources

- Atomic Bomb Debate

- MLA Citation Help

- Research Process

- Plagiarism/Integrate Sources

- Finding Primary Sources

- Primary Sources for HIS132 Assignment

- World War 2 Resources

- Rape of Nanking Research Guide

- Green Book Guide Page

How to Use This Page

Helpful Databases for Primary Documents

- Library of Congress The Library of Congress is an agency of the legislative branch of government. It is the country's oldest federal cultural institution as well as the largest library in the world.

Trans-Mississippi West and a Growing Industrial Economy 1860-1900

- Two Editorials from the Rocky Mountain news The Sand Creek Massacre of November 29, 1864, in which 700 men of a Colorado territorial militia attacked an encampment of unarmed Cheyenne and Arapaho waiting to commence peace negotiations, shocked the nation. Many locals regarded the action as a genuine battle rather than a massacre, as is evident from the following Rocky Mountain News editorials, which reported Chivington's attack as a brilliant victory against a formidable enemy.

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty signed in Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico, on February 2, 1848, ending the 1846–1848 Mexican-American War between the United States and Mexico. Under the terms of the t

- Homestead Act of 1862 The Homestead Act, enacted on May 20, 1862, provided 160 acres of unoccupied public land to any citizen (or intended citizen) who was willing to occupy and cultivate the land for five years and who was either head of a family or at least twenty-one years old. The land was free except for a small filing fee. By 1870 nearly 14 million acres had been homesteaded.

- Hatch Act, 1887 Federal U.S. legislation introduced by Missouri congressman William H. Hatch that provided federal funds for establishing experimental stations to conduct agricultural research.

- Forest Reserve Act Federal legislation passed on March 3, 1891, that codified many public land laws. The act authorized the president to reserve certain public lands from the public domain and reversed the previous policy of transferring public lands to private ownership. Though the act failed to specify the purpose of these reserves and to provide for their administration (the Forest Management Act of 1897 did both), President Benjamin Harrison used the authority to reserve twenty-two million acres, thus beginning the national forest system.

- Dawes Severalty Act Federal U.S. legislation enacted on February 8, 1887, that provided for the dissolution of the Indian tribes as legal entities and the distribution of tribal lands among individual members. In an attempt to remove any remaining authority from the Native peoples, the act granted citizenship to Indians who renounced tribal allegiance and "adopted the habits of civilized life." It allotted to heads of families 160 acres of reservation land and to adult single people 80 acres; the land was initially awarded in trust, with full title to be transferred after twenty-five years.

Democracy and Empire 1870-1900

- Speech for the Literacy Test Bill Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (R-MA) gave this speech on March 16, 1896, in favor of his Literacy Test Bill, which would have required prospective immigrants over age 14 to prove they could read and write their own language. Congress first passed legislation restricting immigration in 1875, banning convicts and prostitutes from immigrating to the United States.

- Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882 In 1879 Congress passed a bill prohibiting further Chinese immigration, but it was vetoed by President Rutherford B. Hayes. The following year a new treaty with China gave the United States the right to limit or suspend the entry of Chinese labor, but not to prohibit it absolutely. The 1882 suspension of immigration was renewed in 1892 and was followed by other exclusionary legislation. These acts were repealed in 1943.

- Harper's Weekly Editorial Criticizing the Chinese Exclusion Bill The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first major law to restrict immigration into the United States. Specifically, the act excluded all Chinese laborers from entering the country for a period of 10 years. During the debate leading up to its passage in Congress, the influential political magazine Harper's Weekly ran an editorial criticizing the bill, which it said betrayed a key aspect of American democracy that traditionally welcomed "the oppressed of every clime and race."

- Treaty of Paris, 1898 Treaty signed on December 10, 1898, ending the Spanish-American War (1898). According to the treaty terms, Spain would abandon its claim to Cuba (which remained a U.S. protectorate until 1934) and cede Puerto Rico and Guam to the United States (both of which remain U.S. territories).

- "Women Nurses in the American Army" Anita Newcomb McGee (1864–1940) was born and raised in Washington, D.C., the daughter of a noted mathematician and astronomer. She received a medical degree from Columbian College (today George Washington University) in 1892, then studied gynecology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. McGee delivered this speech in Kansas City, Missouri, in September 1899. It was subsequently published in Proceedings of the 8th Annual Meeting of the Association of Military Surgeons.

- Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis (excerpt) Josiah Strong, a Protestant clergyman and the secretary of the Congregational Home Missionary Society, called for Christian-based imperialism in Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis (1885), excerpted below. Passionately prejudicial, Strong was convinced that Americans must be properly Christianized, especially because of the "perils" they faced from wayward immigrants, Roman Catholics, Mormons, alcohol abusers, socialists, and newly wealthy industrialists.

- The Comstock Law - 1873 The Comstock law, named for Anthony Comstock, head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, was passed in 1873. It declared contraceptive devices and materials discussing contraception, abortion, or sex education, to be obscene, and prohibited their distribution through the U.S. Postal Service.

- Minor v. Happersett The case involved the 1872 presidential election, during which a suffragist from Missouri named Virginia Minor attempted to vote but was denied. The registrar officiating the voting pointed to a Missouri law granting voting rights only to "every male citizen."

The Twenties 1920-1929

- Appeal to the U.S. Senate to Submit the Federal Amendment for Woman - 1918 Suffrage Speech delivered by President Woodrow Wilson to the United States Senate, asking that the Senate vote to submit the Nineteenth Amendment to the states for ratification.

- Air Conditioning Invented in the early 20th century, air conditioning became popular in the 1920s. In the following article from the New York Times in 1928, a journalist describes the growth of climate-controlled facilities in cities.

- "Guarding the Gates Against Undesirables" (excerpt) This excerpt comes from an article originally published in Current Opinion in April 1924. Many Americans believed that some populations were simply "unassimilable" into the nation, as the unidentified author of the following document reports.

- "Lynch Law National Disgrace" African Americans were lynched at a rate more than three times greater than that of white Americans. While lynchings took place throughout the United States, the great majority occurred in the South. This editorial, originally published in the Cleveland Advocate on May 15, 1920, called for strict enforcement of antilynching legislation.

- "The New Frontage on American Life" Charles S. Johnson, a leading African American social scientist and editor of his day, examined black urbanization in this 1925 essay that appeared in the famous anthology The New Negro, published the same year. According to Johnson, the city changed those African Americans who migrated northward, particularly in terms of economics as well as servility and obsequiousness to whites.

- Remarks on the Appalachian Trail The Appalachian Trail was one of the first large trail systems to be established in the United States. Benton MacKaye described the development of the Appalachian Trail in these remarks to the National Conference on Outdoor Recreation in 1924.

- "Tragedy in North Carolina" In November 1929, seven months after David Clark's editorial appeared in the Charlotte (N.C.) Observer, the North American Review published this defense of the Loray Mill strikers. In the article below, Margaret Larkin attempts to answer some of the charges that Clark made against the striking textile-mill workers.

World War 2 1941-1945

- Account of a Japanese Submarine Attack (October 29, 1944) The U.S. Merchant Marine carried the life's blood of the Allied war effort. Ships were lightly armed and vulnerable to attack, especially by submarines. Sailors of the merchant marine were civilians, but their duty was perhaps the most hazardous of World War II.

- "The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb" After the war, Henry L. Stimson published the following article in Harper's Magazine, which summarized the Manhattan Project and the decision to drop the bombs. Since his appointment as Franklin D. Roosevelt's secretary of war in 1940, Stimson had been intimately involved in the atomic bomb project.

- "Day of Infamy" Speech Address to a joint session of the U.S. Congress delivered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on December 8, 1941, the day after Japan's surprise naval air attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Calling December 7 "a date which will live in infamy," Roosevelt announced that Japanese forces had also attacked other Pacific targets: Malaya, Hong Kong, Guam, the Philippines, Wake Island, and Midway Island. He asked Congress to declare war on Japan because of this "unprovoked and dastardly attack." Within an hour Congress complied, with only one dissenting vote, and the United States entered World War II (1939–1945).

- Account of the "Trinity Test," the First Atomic Bomb Explosion On July 18, 1945, General Leslie R. Groves, chief of the Manhattan Project, which had produced the atomic bomb, sent a top-secret report to Secretary of War Henry A. Stimson narrating the successful test two days earlier. Groves appended General Thomas Farrell's eyewitness account, which was written from the perspective of the observation post he had occupied. Farrell's account is excerpted from an official U.S. State Department publication.

- Account of the Attack on the USS Arizona, Pearl Harbor The Japanese surprise air raid on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, devastated the U.S. Pacific Fleet—albeit not beyond recovery—and propelled the United States into World War II. Corporal E. C. Nightingale was a member of the U.S. Marine detachment assigned to the USS Arizona, one of the battleships moored along "Battleship Row," the principal target of the first wave of the attack.

- Account of Iwo Jima The taking of Iwo Jima consumed five bloody weeks and the lives of 6,821 Americans and some 21,000 Japanese soldiers. The Japanese garrison defending this small volcanic island fought from the cover of a complex network of caves, tunnels, and bunkers, which allowed the defenders to hold off conquest for more than a month. More U.S. Marines died here than anywhere else in the Pacific theater. What follows is excerpted from a collection of reports by five official USMC combat writers, published after the battle.

America at Mid-Century - 1952-1963

- Moon Landing Mission Speech 1961 Address given by President John F. Kennedy to a special joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961, in which he appealed for a new program that would put a man on the moon before 1970. Kennedy called the speech his "second State of the Union message of 1961."

- Hawaii Admission Act Hawaii and the United States had a long and complicated relationship before Hawaii was finally admitted to the Union in 1959. Over 100 years earlier, in 1849, the United States signed its first commercial treaty with Hawaii, acknowledging Hawaii's independence.

- Letter to Nikita Khrushchev on the Cuban Missile Crisis Letter from President John F. Kennedy to Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev written on October 27, 1962. In this letter, Kennedy responds to Khrushchev's terms, received the previous day, for settling the Cuban Missile Crisis. Kennedy accepted Moscow's proposal that all Soviet missiles be removed from Cuba under U.N. supervision if the United States suspended its blockade and gave assurances that it would not invade the island.

- "Ich bin ein Berliner" Address Address delivered by U.S. president John F. Kennedy in West Berlin on June 26, 1963, after a visit to the Berlin Wall separating the eastern and western sections of the city. Affirming his support for West Berlin as an island of freedom, Kennedy described the two-year-old wall as an offense against humanity and a demonstration of the failures of the communist system.

- "Great Society" Speech Speech given by President Lyndon Baines Johnson on May 22, 1964, to the annual commencement exercises of the University of Michigan. In it Johnson proposed a major new plan to build a "Great Society" in the United States—one in which the quality of individual lives was elevated and American civilization was advanced.

Civil Rights Movement 1945-1966

- Civil Rights Act, 1964 Federal legislation enacted on July 2, 1964, providing the strongest American civil rights legislation since Reconstruction (1867–1877). It prohibited discrimination in all public accommodations (including hotels, gas stations, restaurants, and theaters), if their operations affect commerce, and in any program receiving federal funds.

- Civil Rights Act, 1968 Federal legislation enacted on April 11, 1968, intended to end discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin in housing in the United States.

- Letter to Martin Luther King Jr. on the Need for a United Front Despite earlier disputes, Malcolm X's letter, below, of July 31, 1963, to Martin Luther King Jr. illustrates his willingness to work with other civil-rights leaders in order to defuse what he called the "racial powder keg." He laments the fact that black leaders have failed to come together due to "minor" ideological differences.

- "I've Been to the Mountain Top" Speech Speech delivered by the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the evening of April 3, 1968, to an African-American congregation at the Masonic Temple in Memphis, Tennessee. It was the last speech King gave before his assassination.

- Speech on Black Power Richard Wright used the phrase "black power" in his 1954 book of the same title, and Malcolm X developed what he called the gospel of black nationalism. But Stokely Carmichael, as Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chairman, first developed the idea into a full movement ideology. In this July 28, 1966, speech in Chicago, Carmichael laid out a philosophy that Huey Newton and Bobby Seale adopted for their newly formed Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP).

- Brown v. Board of Education Landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision issued on May 17, 1954, declaring that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

Inequality in the Global Age 2000-Present

- Inaugural Address, 2013 President Barack Obama delivered his second inaugural speech on January 21, 2013, Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The president acknowledged the date through his calls for unity, equality, and peaceful action, echoing the orations of the civil rights leader.

- Remarks by the President and the Vice President on Gun Violence Vice President Joseph Biden and President Barack Obama delivered speeches at the White House on January 16, 2013, outlining a proposed set of stricter gun control policies in the United States. The speeches were delivered in the wake of the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, which occurred on December 14, 2012, and resulted in 26 deaths (20 of whom were children).

- Authorization for Use of Military Force against Terrorists Resolution passed by the U.S. Congress on September 14, 2001, authorizing President Bush to use "all necessary and appropriate force" against those responsible for the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

- Address to the Nation on the National Economy In September 2008 the U.S. economy, hit by the subprime mortgage crisis and subsequent liquidity crisis, was in the middle of the most severe financial disaster since the Great Depression. In a September 24, 2008, televised address to the nation, President George W. Bush urged Congress to approve Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson's $700 billion bailout plan.

- Supreme Court legalizes same-sex marriage nationwide Gee, Brandon. "Supreme Court Legalizes Same-Sex Marriage Nationwide." Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, 2015. ProQuest, http://proxy154.nclive.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/supreme-court-legalizes-same-sex-marriage/docview/1692640561/se-2?accountid=13601.

- Victory Speech - Biden 2020 After several days of waiting for absentee ballot vote tallies to trickle in, Joe Biden was finally declared the winner of the 2020 presidential election on Saturday, November 7. Biden delivered a victory speech that evening in Wilmington, Delaware.

- Remarks at the Signing of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act Passed by Congress on January 29, 2009, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act extended the statute of limitations for employees suing for pay discrimination. The act was passed in response to Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., a 2007 Supreme Court decision that ruled Lilly Ledbetter's gender discrimination suit against her employers to be invalid on the basis of that statute of limitations.

Local or NC Sites for Primary Documents

- Religion in North Carolina Religion in North Carolina The Religion in North Carolina Digital Collection is a grant-funded project to provide digital access to publications of and about religious bodies in North Carolina. Partner institutions at Duke, UNC, and Wake Forest University, contributed the largest portion of the items.

- North Carolina Digital Collections The North Carolina Digital Collections contain over 90,000 historic and recent photographs, state government publications, manuscripts, and other resources on topics related to North Carolina. The Collections are free and full-text searchable, and bring together content from the State Archives of North Carolina and the State Library of North Carolina.

Reconstruction 1863-1877

- Reconstruction Acts Series of four related acts that provided for the military occupation of the former Confederacy. They were passed between March 1867 and March 1868 over the vetoes of President Andrew Johnson.

- North Carolina Sharecropping Contract From 1882. Sharecropping was a system of agriculture in the United States and many other parts of the world. In the United States, it existed mainly during the Reconstruction period but also in some parts of the Antebellum South.

- Proclamation on the Wade-Davis Bill In 1863, Abraham Lincoln proposed the 10 Percent Plan, in which 10 percent of all white males in each Confederate state had to take a loyalty oath, in order for their state to be readmitted into the Union. The states also had to recognize permanent freedom for all former slaves.

- Speech on Reconstruction Speech before the U.S. House of Representatives on December 18, 1865, by Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens urging a harsh policy of reconstruction toward the defeated Confederacy.

- Civil Rights Act, 1875 Federal act designed to prohibit social discrimination against blacks, passed by Congress on March 1, 1875. The act guaranteed to all citizens—regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude—equal rights in public places, such as inns, theaters, restaurants, and public conveyances. Denial of these rights was punishable by payment to the aggrieved person and fine or imprisonment. Many whites refused to obey the act, and in 1883 the Supreme Court struck down the law as unconstitutional on the grounds that Congress did not have the authority to legislate the social customs of any state. The 1875 act was the last federal civil rights legislation until the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Production and Consumption in the Gilded age 1865-1900

- Sherman Antitrust Act First federal U.S. legislation to regulate trusts, enacted on July 2, 1890. Introduced by Republican senator John Sherman, it declared illegal "every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations."

- "How I Became a Socialist" (excerpt) This excerpt comes from Helen Keller's November 3, 1912, article, "How I Became a Socialist," published in the New York Call, in response to an offensive commentary in Common Cause that suggested her socialism could be explained as a result of her "limited development."

- Editorial on Imperialism (excerpt) Author Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) was living abroad when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, but he had long been a vocal critic of what he saw as the rampant greed and corruption that plagued America, as displayed in his work The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, cowritten with colleague Charles Dudley Warner. Upon Twain's triumphant return to the United States, he made the following anti-imperialist editorial statement, recorded in October 15, 1900.

- "The Rise of the Standard Oil Company" (excerpt) Written by muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell, "The Rise of the Standard Oil Company" exposes John D. Rockefeller's unethical business practices in turning his oil company into the largest monopoly in existence at the beginning of the 20th century. The article was originally published in a 16-part series in McClure's Magazine. Tarbell had a particular interest in the Standard Oil Company because it had forced her father's independent oil refinery out of business.

- What Social Classes Owe to Each Other (excerpt) The following is an excerpt from Yale sociologist William Graham Sumner's 1883 piece, What Social Classes Owe to Each Other. For all the criticism of the wealthy, there were also staunch defenders of the new economic order. Sumner, in particular, applied some of Darwin's principles of natural selection and evolution to argue that the laissez-faire approach to economics was the best way to ensure the progress of society.

Progressive Era 1900-1917

- Prohibition Party Platform, 1912 Political platform adopted on July 10, 1912, by the Prohibition Party at its national nominating convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

- "Principles of Conservation" Shortly after President William Howard Taft fired Gifford Pinchot as the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service in 1910, Pinchot published this famous statement summarizing the principles of Progressive Era conservation. Pinchot believed that the conservation of forests and other natural resources was essential to American security, prosperity, and democracy.

- Volstead Act, 1919 Federal U.S. legislation passed on October 28, 1919, to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment, establishing Prohibition. The act, introduced by Representative Andrew J. Volstead of Minnesota and passed over the veto of President Woodrow Wilson, defined intoxicating liquor as any beverage containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol by volume.

- Blue Book (excerpts) Two excerpts from The Blue Book, a collection of essays published in 1917 by the National Woman Suffrage Publishing Company. "Why Women Should Vote," by Jane Addams, and "Objections Answered," by Alice Stone Blackwell take different approaches in arguing for woman suffrage.

US in the Era of the Great War 1901-1920

- Appeal for Neutrality, 1914 Message from President Woodrow Wilson to the U.S. Senate on August 19, 1914, following the outbreak of World War I in Europe. Issued shortly after his Proclamation of Neutrality of August 4, this appeal to the American people called for neutrality "in thought as well as in action."

- Selective Service Act, 1917 Federal legislation enacted on May 18, 1917, establishing registration and classification for military service of all men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty, inclusive. Local civilian draft boards were given responsibility for administering the draft. Exemptions were allowed for alienage, physical unfitness, and conscientious objections on religious grounds.

- "It's Duty Boy" Even after the American declaration of war against Germany, Socialists, pacifists, Progressives, and other Americans were not convinced the United States had a vested interest in the European conflict. In 1917, in order to sell the war to the American people, President Woodrow Wilson mobilized public opinion through the establishment of the Committee of Public Information, headed by Denver journalist George Creel.

- Zimmermann Telegram In early 1917, while the U.S. Congress was debating arming merchant ships to offset Germany's unrestricted submarine attacks on neutral vessels, the British government released a telegram intercepted and deciphered by their Royal Navy from German foreign secretary Alfred Zimmermann to Heinrich von Eckhardt, the German minister to Mexico; the telegram, sent January 19, 1917, is reprinted below.

The Great Depression and New Deal 1929-1940

- Press Release Declaring Confidence in the American Economy From the start of the Great Depression, with the spectacular stock-market crash of October 1929, President Herbert Hoover continually declared his confidence in the soundness of the American economy. In the following press release from November 15, 1929, he notes his recent meetings with business leaders and reaffirms his belief in the general strength of the economy.

- Second Fireside Chat: Outlining the New Deal Program The New Deal established public programs that fought to alleviate the widespread unemployment, poor economy, and unstable financial system that plagued the United States during the Great Depression. In a Fireside Chat on May 7, 1933, Roosevelt outlined the New Deal legislation that had already been approved by Congress, and he campaigned for legislation that had yet to be passed, including what became the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

- "Forgotten Man" Radio Speech National radio address delivered by Franklin D. Roosevelt, Democratic governor of New York, on April 7, 1932, in which he argued that hope for national economic recovery from the Great Depression resided with the ordinary farmer and industrial worker—"the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid."

- "Both Will Kill a Man" Arturo, an Italian-American stonecutter in his fifties, was interviewed by Mary Tomasi and Roaldus Richmond of the WPA's Federal Writers' Project (FWP) in Barre, Vermont, in 1938. Arturo alternated his time between working as a letter-cutter for a local quarry and engaging in days-long drinking binges. The health and safety hazards of stonecutting, Arturo told them, had the potential to kill him if his drinking habit did not, but neither had thus far destroyed him.

- "All Our Folks Was Farmers" In a Federal Writers' Project (FWP) interview with a family of tenant farmers near Fletcher, North Carolina, Anne Winn Stevens described the striking contrast between the palatial estate occupied by the farm's owners and the ramshackle cabin in which the Riddle family lived.

Cold War Begins 1945-1952

- "Iron Curtain" Speech Widely considered to be former prime minister Winston Churchill's most important speech as leader of the opposition in Parliament (1945–1951). He delivered the speech, formally entitled "A Shadow Has Fallen Over Europe and Asia," on March 5, 1946 at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. Churchill expressed alarm and concern at the Soviet Union's expansion in eastern Europe.

- Truman Doctrine Doctrine enunciated by President Harry S. Truman in a speech to Congress on March 12, 1947, proclaiming a U.S. commitment to help non-communist countries resist Soviet expansion.

- "Consequences of the Korean Incident" Written on July 8, 1950, approximately two weeks after the start of the Korean conflict, this document is titled "Consequences of the Korean Incident." Here the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) analyzes Soviet motives for launching an attack on South Korea, probable developments of the conflict, and immediate effects of a failure to hold South Korea.

- Korean War Armistice (excerpt) The Korean War (1950–1953) solidified the country's divide into two states—North Korea and South Korea. The war also set the stage for the coming cold war, situating the communist nations of the Soviet Union and China against the United States in the nuclear age.

- Control of Atomic Energy Joint declaration on control of atomic energy issued by U.S. president Harry S. Truman, British prime minister Clement Attlee, and Canadian prime minister W. L. Mackenzie King on November 15, 1946. In January 1946 the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission was formed to establish international control over atomic energy and devise a scheme for nuclear disarmament.

America at War Abroad and at Home 1965-1974

- Account of Captain Thomas J. Hanton's Experience as a POW (excerpt) Officially called Hoa Lo Prison, the "Hanoi Hilton" (as U.S. prisoners of war christened it) had been built by the French to house political prisoners and became infamous during the Vietnam War as the principal repository for American POWs, who were mostly aviators shot down on missions over North Vietnam.

- Accounts of the Tet Offensive The Tet Offensive, which began on January 30, 1968, sent shock waves through the U.S. home front and rapidly eroded waning popular support for the Vietnam War. A massive tactical defeat for the Viet Cong and NVA, Tet was nevertheless a profound psychological and propaganda victory for them and therefore a strategic triumph.

- Address to Nation on Cease-Fire in Vietnam On January 23, 1973, President Richard Nixon announced to the country that the Paris negotiation talks between the United States, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam had resulted in an agreement to cease fire.

- Basic Principles of Relations between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Since even an accidental confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States could have destabilized world peace, the summit of 1972 was a necessary step to peaceful coexistence. Regional conflicts had the potential of setting the two superpowers against each other, and the summit attempted to lessen the possibility that such an event would escalate into a nuclear crisis.

- Eyewitness Account of the Kent State Shootings Immediately after the Kent State shootings on May 4, 1970, it was clear to observers that the events would have a lasting impact on the relationship between American youths and more-conservative elements in the United States. The following statement from the FBI files is a firsthand account of the Kent State shootings by a freshman at Kent State University. It demonstrates the grim realities of that day.

- Title IX Law passed as part of the Educational Amendments Act of 1972, stating that no one could be excluded from or subjected to discrimination because of her sex by any educational program receiving Federal aid.

- Baker v. Nelson In the following 1971 opinion, from Baker v. Nelson, the Minnesota Supreme Court communicates its decision in support of the county clerk who denied an attempt by two men, Richard John (Jack) Baker and James Michael McConnell, both gay-rights activists, to obtain a marriage license in Hennepin County. This case was the first in the United States involving same-sex marriage.

- Civil Rights Amendment, 1972 Legislation enacted on October 14, 1972, that extended the life of the Commission on Civil Rights. In addition, the act extended the jurisdiction of the commission to include sexual discrimination and to authorize appropriations.

- Statement on the Vietnam War - Martin Luther King Address given by civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to a rally of his Southern Christian Leadership Conference on August 12, 1965, in Birmingham, Alabama.

- Statement on Watergate The Watergate scandal, which involved the break-in and subsequent cover up at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, consumed the last two years of Richard Nixon's presidency. On May 22, 1973, after multiple denials of having any connection to the scandal, Nixon issued a 4,000-word statement to the public that defended his involvement in the affair. In the report, Nixon assumed fault for not heeding "the warning signals I received along the way about a Watergate coverup," but he denied having anything to do with either the break-in or cover up.

Conservative Ascendancy 1974-1999

- "A Black Feminist Statement" The statement below was drafted in April 1977 by founders Barbara Smith, Demita Frazier, and Beverly Smith of the Combahee River Collective, a black feminist group formed in 1974. The group held meetings in Massachusetts and New York to assess the state of black feminism and to plan future activism.

- State of the Union Address, 1980 Jimmy Carter's third State of the Union address, delivered before a joint session of Congress on January 23, 1980. The president's third annual message was delivered during a time of national crisis. Nine weeks earlier, the American embassy in Teheran was seized by radical Iranian students, who took 52 Americans hostage.

- Remarks on the Hostage Situation in Iran and the Soviet Intervention in Afghanistan While speaking to reporters on December 28, 1979, President Carter announced his administration's plans to seek a resolution to end the occupation of the American embassy in Iran and free the embassy personnel taken hostage. Carter also went on record as protesting the recent invasion and overthrow of the Afghanistan government by the Soviet Union.

- Challenger Disaster Address Broadcast address given by President Ronald Reagan on January 28, 1986, following the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger shortly after takeoff.

- "Thousand Points of Light" Speech Speech given by Vice President George H. W. Bush to the Republican National Convention in New Orleans on August 18, 1988, as he accepted the party's nomination for president. The speech, widely regarded as perhaps the finest of Bush's career, gave rise to two popular catchphrases: "a thousand points of light" and "a kinder and gentler nation."

Salem Press ebooks

- Current Topics: Selected Essays on Civil Disobedience, Social Justice, Nationalism & Populism, Violent Demonstrations, and Race Relations by Salem Press Publication Date: 2017 Excellent Resource for documents to support rhetorical analysis.

- << Previous: Finding Primary Sources

- Next: World War 2 Resources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.rccc.edu/amhistory2

Educator Resources

Document Analysis

Document analysis is the first step in working with primary sources. Teach your students to think through primary source documents for contextual understanding and to extract information to make informed judgments.

Use these worksheets — for photos, written documents, artifacts, posters, maps, cartoons, videos, and sound recordings — to teach your students the process of document analysis.

Follow this progression:

Don’t stop with document analysis though. Analysis is just the foundation. Move on to activities in which students use the primary sources as historical evidence, like on DocsTeach.org .

- Meet the document.

- Observe its parts.

- Try to make sense of it.

- Use it as historical evidence.

- Once students have become familiar with using the worksheets, direct them to analyze documents as a class or in groups without the worksheets, vocalizing the four steps as they go.

- Eventually, students will internalize the procedure and be able to go through these four steps on their own every time they encounter a primary source document. Remind students to practice this same careful analysis with every primary source they see.

Worksheets for Novice or Younger Students, or Those Learning English

- Written Document

- Artifact or Object

- Sound Recording

See these Worksheets in Spanish language

Worksheets for Intermediate or Secondary Students

Worksheet for understanding perspective in primary sources - for all students and document types.

This tool helps students identify perspective in primary sources and understand how backgrounds, beliefs, and experiences shape point of view.

- Understanding Perspective in Primary Sources

Former Worksheets

These worksheets were revised in February, 2017. Please let us know if you have feedback. If you prefer the previous version of the worksheets, you can download them below .

- Motion Picture

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Primary source analysis exercises, instructions, flyer activity, photograph activity, poster activity, map activity, letter activity.

- More Exercises

- Advanced Exercises

You should always verify and evaluate the information you find. Just because something is a primary source doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have bias or that the facts shouldn't be verified. You can start by determining the purpose/bias of the author of the document.

There are six activities to guide you through evaluating different types of primary sources including flyers, letters, maps, photographs, and posters.You may not be able to answer some of the questions.You are encouraged to search the Internet to learn more about the items to see if you can find answers or make an educated guess.

Click on the image for the item of interest and it will take you to the activity.

- Next: More Exercises >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2022 3:50 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/primarysourceanalysis

Using and Accessing Primary Sources

- Why Do Historical Research?

- Types of sources

- Forming a research topic

- Locating sources

- BMI 552/652

- BLHD Enrichment Week

- More information

Evaluate and Analyze

- A letter written by a twenty-five-year old medical student will differ greatly from a letter written by a scholar of health science practices. Although the sentiment might be the same, the perspective and influences of these two authors will be worlds apart.

- A historian doesn't look for the truth, since this presumes there is only one true story. The historian tries to understand a number of competing viewpoints to form their own interpretation – what constitutes the best explanation of what happened and why.

- Who authored the source?

- Who is the historical actor?

- Who isn't represented in the historical record?

- What is the document about (what points is the author making)?

- What kind of audience did the author intend to reach?

- What aren't you finding? What are the silences in the record?

- When did this take place?

- When was the resource created or written?

- Where did the happening occur?

- Where was the resource created, published, and/or disseminated?

- Why did something happen the way it did?

- Why was this resource created? (also involves the intended audience)

Examine your biases

- What do you bring to the evidence that you examine?

- Are you inductively following a path of evidence, developing your interpretation based on the sources?

- Do you have an ax to grind?

- Did you begin your research deductively, with your mind made up before even seeing the evidence?

- Use as wide a range of primary source documents and secondary sources as possible

- Adds depth and richness to your historical analysis

- The more exposure you have to different sources and viewpoints, the more you have a balanced and complete view about a topic in history

- More exposure/viewpoints may spark more questions and ultimately lead you to unravel more clues about your topic

- << Previous: Forming a research topic

- Next: Locating sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 11, 2024 3:20 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ohsu.edu/primarysourceguide

Resources: Discussions and Assignments

Module 1 assignment: primary source analysis and western expansion.

In this module, we learned about analyzing primary source documents using the HAPPY Analysis. For this assignment, you will complete a HAPPY Analysis for one of the primary source documents from the reader for this module or other documents related to westward expansion and Native American life during this time period.

Instructions:

Step 1 : Pick a document to analyze:

- Primary Source: Chief Joseph on Indian Affairs (1877, 1879)

- Primary Source: Chester A. Arthur on American Indian Policy (1881)

- Wars with the California Tribes (1891)

- More Indian Outrage (1851)

- Letter from Governor Ross Supporting Apache Removal (1886)

Step 2 : Fill out the HAPPY Analysis Chart for the document you chose. Remember to do a careful, close reading of your source document and fill out the HAPPY analysis in detail.

STEP 3 : Submit your completed chart.

Assignment Grading Rubric:

How to Analyze a Primary Source

Article objectives.

- To learn how to read and analyze historic primary source documents.

Primary Sources

What is a primary source, and why does anyone care? Those are the first and most important questions that a young historian must answer before they can start working with primary sources. So let’s answer them.

A primary source is a piece of historic evidence created or produced during the time that is being studied. Primary sources are a great resource for historians because they can tell us what life was like at the time of the source’s creation – or at least what the creator thought it was like. Cartoons, television shows, newspaper articles, speeches, books, art, and film are all examples of primary sources. A secondary source by contrast is a person’s second hand interpretation and analysis of a time period or a primary source. Textbooks, and journal articles are great examples of secondary sources. Both types of sources are tremendously helpful for historians, but primary sources are especially important for uncovering new information about the past.

Don’t believe me? It’s true. Artifacts from the past can tell us a lot about the culture and society they come from. Here is an awesome example:

The image above is the cover of Captain America issue number 1. Take a look. This seemingly simple comic book written for children reveals a great deal about American culture – as do many comic books. Let’s try examining the document.

First, what do you see? Clearly this is a comic book depicting the character of Captain America fighting the Nazi’s. Clearly he is doing a good job since he has just punched Hitler in the face. Within the Nazi stronghold it is clear that the Nazi’s were planning an invasion of America. On the far wall is a live feed of a Nazi operative bombing a US munitions factory and on the table next to Hitler is a map of the US and a little book called “Plans for the USA.” What this image seems to show is a Nazi plan to invade the United States and the importance of US military involvement to fight the Nazi’s.

Given our knowledge that America did get involved in WW2 and were strong opponents of the Nazi’s, the content of this document may seem unsurprising. However, take a look at the date of the comic. The comic, issue 1, is dated March on the front cover (the inside cover reveals the issue date of March 1941). That means this comic book came out a full 10 months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (December 1941). That a children’s comic book would come out in support of entering the war while the majority of Americans still opposed the idea reveals something new about American society. Americans it seems were not as unanimous as they appeared at first glance.

Captain America creator Jack Kirby – aka Jacob Kurtzberg – was just one of the many Americans who was especially sensitive to the activities of the Nazi party. Being a Jewish American, Kirby was strongly in support of war against the Nazis even before war officially broke out. His character of Captain America was therefore very conscious of the war effort and was constantly fighting Nazi foes. Kirby was not alone in his support of the war and his comic book reveals a large population concerned about rising Nazism and willing to stand against it.

Historian Bradford Wright, whose book Comic Book Nation discusses the importance of comic books in American society, claims that “in these garish comic book images, one glimpses a crude, exaggerated, and absurd caricature of the American experience tailored for young tastes” (Wright, xiv.)

As you can see from above, the ability to analyze sources is an extremely important tool in the historian’s pocket. So you must learn how to go about analyzing sources on your own. Whenever you are faced with a new source, there are certain questions you must ask:

- What is the document?

- When is the document from?

- Where is the document from?

- Whose speech does the document represent?

- Who is the document addressed to?

- What does the document say?

- What potential sources of Bias does the document contain?

- What lessons does the document teach you?

What is the document? Usually this question is the easiest to answer, so it’s the best starting place. The question ‘what is the document’ covers the medium and title of the document. For the example used above the document is a Captain America comic book – Captain America No. 1.

When is the document from? Again this question is straightforward but involved – when was the document produced and what was the context in which it was created?

Where is the document from? What specific country was the document created in? Was the document created about an event in a different company?

Whose speech does the document represent? This is the first hard question, because the answer isn’t always straight forward. The document in question may have been created by a single person, or by a group of people. Or, it may have been created on behalf of a group of people. Take for example political ads. Some of the ads are created by the candidate, some are created by a group the candidate is part of, and some may have been created by a third party speaking for the candidate. In these cases the issue of ‘whose speech’ the ad represents becomes a factor. Take the more concrete example of Captain America No. 1. The comic was written by Jack Kirby, but produced by Timely Comics, so whose speech is it. It is certainly Jack Kirby’s, but is it also Timely Comic’s? Does Kirby speak for the comic book industry or just the company? Furthermore, the comic was read by millions of American children, does that mean it represents their opinions too? These questions aren’t easy to grapple with, but must be considered when analyzing a document.

Who is the document addressed to? This oft overlooked aspect of document analysis is extremely important, because it changes the message and tone of a document. Suppose you are looking at a political speech, the audience of that speech will change the contents of it. If the speech was given at an inauguration, then it was likely designed to fit a large audience. The messages contained in it are likely to be broad and general. The more controversial claims are likely to be left out.

What does the document say? Depending on the document at hand, answering this question may be easier said than done. Some documents are very straightforward, whereas others are very misleading. Often, a document’s author may have been saying exactly what they meant, but in many cases the author is less clear. They say an image is worth a thousand words, but sometimes an image based document can leave you speechless. Ultimately, it is up to you as a historian to decipher the documents meaning. It helps to read the document multiple times, or study the image very carefully looking for all the possible clues. Think always about what the document is saying to its audience, and also what it says to you as a historian.

What potential sources of Bias does the document contain? Bias is prejudice for or against a certain person, group, viewpoint etc. and it often appears in historical documents. Human beings are often biased about one thing or another, and it is you job as a historian to identify any potential bias in the document you are analyzing. The presence of bias can alter the reliability of a document – the creator may not be lying, but their version of the truth may not be as accurate as an unbiased observer.

What lessons does the document teach you? It’s important to remember that historical documents don’t exist in a vacuum – and your teacher or exam board isn’t just making you analyze these documents because they can. The analysis of historical documents is useful because it can reveal new information about the past, or because it can be used as evidence to support an argument about some historical topic. So, always explain what the document teaches you and you’ll be able to get the most out of source analysis.

Image courtesy of:

Kirby, Jack. Captain America no. 1, "Meet Captain America" March 1941

Assessment Forum

Creating and Administering a Primary Source Analysis

John Buchkoski, Mikal B. Eckstrom, Holly Kizewski, and Courtney Pixler | Jan 1, 2015

H undreds of students pass through the introductory history courses of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln each semester with various backgrounds and skill levels. Although some of them have faced a primary source assessment, perhaps in the Advanced Placement Document Based Question Exam, our department had no universal assessment tool to evaluate student learning and skill development. In January 2014, William G. Thomas, our chair, and Margaret Jacobs, the chancellor’s professor of history, asked us to write and administer an exam for all introductory American history courses. Our goal was to construct new pedagogical tools that integrated more primary source analysis into our survey courses.

Collaboration was key to our success, and our different backgrounds and teaching experiences were vitally important in identifying the most significant components of history writing. We agreed that these components were a clear thesis statement, the number of sources used, organization, and analysis. We worked together to ensure that primary sources were similar for the pre- and post-1877 US exams in that they presented issues dealing with race, class, and gender. For example, we incorporated the Utmost Good Faith Clause from the Northwest Ordinance on the pre-1877 test and the Burton-Wheeler Act on the post-1877 test to demonstrate legal decisions regarding Native Americans and land. We chose sources that students were unlikely to have seen before and worked with the instructors to make sure the students would know the context in which the source had been created.

It is impossible to design a “one size fits all” exam that caters to the learning style of each student, but our mix of textual and visual sources helped make our exam more accessible. In order to prepare the students for the exam, the team led a workshop in each of the eight classrooms that focused on how to use primary sources. By working through a sample question and documents in the classroom, we modeled the best strategies for succeeding on the exam. We focused on how to write an effective essay, with a strong thesis statement and a cohesive structure guided by topic sentences. To ensure that online or absent students could review the information covered, the project team used Camtasia, a digital audio-recording tool, to record a podcast of the workshop, which we provided online along with a PowerPoint presentation.

The primary source assessment (PSA) team realized that the students’ teachers used a wide variety of teaching styles and presented very different course content. Each team member served as a liaison between two US history instructors and the PSA team. Faculty reaction to the PSA was varied; some instructors were enthusiastic, while others were initially skeptical. Two factors—clearly discussing the goals of the project and being available for further discussions—helped allay many of the faculty’s concerns. The instructors often found ways to adapt our lecture to fit the themes of the class and their teaching styles. Feedback from the instructors was particularly essential to the success of our workshops, as we were able to incorporate their suggestions over the course of eight lectures. This flexibility on our part helped us to adapt to the challenges that come with stepping into someone else’s classroom.

Because the members of the PSA team had varied historical interests and specializations, each contributed a different perspective to the exam. After choosing the American Revolution and the New Deal as the exam topics for each half of the survey, we eventually selected seven or eight sources. We decided to keep our questions somewhat simple in order to encourage argumentative thesis writing and broad use of evidence. For the first half of the survey, we asked, “Did all Americans benefit equally from the American Revolution?” and used sources covering women, Native Americans, and African Americans to provide a wide range of evidence. Likewise, for the second half of the survey, we asked, “Did all Americans benefit equally from the New Deal of the 1930s?”; we provided sources on African Americans, Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and working-class individuals. In order to remain objective in grading, we designed a rubric. We graded some of the exams together and frequently communicated about the grading process to ensure consistency.

The PSA team assessed the exams using four categories—thesis, sources, analysis, and organization—and tracked the results on a rubric (see sidebar). We then extrapolated various data sets from over four hundred exams. The HIST 110 (American history to 1877) classes averaged 83% for every category except the analysis category (77%). HIST 111 courses averaged higher (82%) in three categories (thesis, sources, and organization), but the analysis was still lower (79%). The averages for both American survey courses were as follows: thesis (83.4%), sources (83%), analysis (79%), and organization (82.2%).

We were pleased to discover that students taking the courses online scored comparably to those in traditional classrooms, leading us to believe that the PSA is effective in both environments. We were also pleased that the students focused on creating precise, argumentative theses and that almost every student provided a thesis statement. Additionally, most used at least six or seven of the documents we provided as evidence in support of their arguments. In the category of organization, a majority of students used a five-paragraph structure with topic sentences, which showed ability to effectively group evidence within a fluent argument. The PSA also indicated to our department the areas in which students could most improve. The analysis portion resulted in the lowest scores. We found that students referred to the sources in their essays but struggled to connect the context of the documents to their argument.

On the question about the American Revolution, in particular, we noted that students’ arguments often did not match the sources. Some students were reluctant to state that the Revolution did not result in total equality, incorrectly arguing that slaves and women became full members of the new Republic. Although students were more willing to be critical of the New Deal policies, we nevertheless encountered essays that argued for the fairness of repatriation and Indian removal. Many students relied on a predetermined narrative that was some variation of American exceptionalism and that clouded their ability to judiciously examine the sources we provided.

The exam also unexpectedly revealed that some students lacked a historical context for understanding race in American history. Documents and questions provided to students highlighted the entanglement of race with US history. During the workshops, the team discussed the interplay of race, class, and gender as a primary analytical tool for assessing the sources. Still, some students wrote that when African Americans are unable to receive Social Security, it is due to laziness, rather than to the historical legacy of the Jim Crow South and the institutional discrimination of the New Deal. When describing Native Americans in the New Deal Era, students adopted the “lazy Indian” trope. Others argued that the government should have taken Indian lands to boost the struggling economy. A few students also grafted current racialized debates onto the documents. For example, when analyzing documents on 1930s Mexican repatriados, one student wrote, “I think the New Deal was a little too fair for Mexicans wishing to return back [sic] to Mexico and take all their goods back. I don’t think illegal immigrants deserve this.” By couching their arguments in current issues of citizenship and migration, this student disregarded historical context. Finally, some students used problematic language found within the documents, such as the word negro .

As troubling as this was, the team agreed that the problematic essays were clearly not malicious. Rather, they seemed to be based on current political issues and a reluctance to criticize celebrated American policies. Although these problems were few in number, the department developed strategies to help students think about race as a construction, in and out of the classroom. One faculty member had advised against using the term negro in his syllabus and in class, and students from his class consistently used culturally appropriate language for African Americans in their essays. In spring 2014, the department discussed teaching about race in a previously planned workshop for faculty and graduate students. We were able to use our findings at this workshop to demonstrate the continuing need for critical race analysis in our classrooms.

Our department-wide efforts to bring a primary source assessment to our introductory classes produced mostly positive results. We were excited to discover that our survey-level students effectively produced structured, argumentative responses to primary sources. We also learned that, going forward, our focus should be on promoting critical analysis. The PSA team learned how to navigate the complexities of large-scale assessments and set the groundwork within our department for similar examinations in the future. Based on our results, the department is considering extending this assessment to other introductory surveys in the future.

The authors are graduate students in history at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

Grading the Primary Source Assessment

Thesis: 25%

Number of Sources: 25%

Analysis of Evidence: 25%

Organization: 25%

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities , and in letters to the editor . Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Tags: Resources for Faculty Resources for Graduate Students Resources for History Departments Resources for Undergraduates K12 Certification & Curricula Teaching Resources and Strategies

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

How to Write a Primary Source Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide

Feeling behind on ai.

You're not alone. The Neuron is a daily AI newsletter that tracks the latest AI trends and tools you need to know. Join 400,000+ professionals from top companies like Microsoft, Apple, Salesforce and more. 100% FREE.

If you've been assigned a primary source analysis for your coursework, it can seem like a daunting task. However, with the right approach and some guidelines, analyzing a primary source can be a rewarding and enriching experience. Here is a step-by-step guide for how to write a primary source analysis that will help you tackle this assignment with confidence.

Understanding Primary Sources

Before you begin analyzing a primary source, it is essential to understand what a primary source actually is. A primary source is a document or artifact that was created during the historical period you are studying. It could be a written document, such as a letter or diary entry, or a non-written document, like a painting or photograph.

Definition of a Primary Source

Primary sources provide firsthand accounts or direct evidence about an event or phenomenon. They are the raw materials of history, providing us with a glimpse into the past that cannot be found anywhere else.

Importance of Primary Source Analysis

Studying primary sources is an essential part of historical research. By analyzing primary sources, you can gain a better understanding of the past and the people who lived through it. You can also develop critical thinking skills and learn how to evaluate sources for their reliability and bias.

One of the most important aspects of primary source analysis is understanding the context in which the source was created. This means considering the historical, social, and cultural factors that influenced the author or creator of the source. For example, a letter written during the Civil War may have a different tone and perspective than a letter written during peacetime.

Another important aspect of primary source analysis is evaluating the credibility of the source. This means considering factors such as the author's bias, the accuracy of the information presented, and the purpose of the source. For example, a government report may be biased towards a particular political agenda, while a personal diary may be more subjective in nature.

Examples of Primary Sources

Primary sources can take many different forms. Some examples include: