- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

In My Blood It Runs review – quietly masterful portrait of growing up Indigenous

Collaborative, open-hearted documentary of a young Arrernte boy is Gayby Baby director Maya Newell’s best work yet

T he defining image imprinted on to my mind after watching director Maya Newell ’s excellent film In My Blood It Runs is of a child – its 10-year-old subject, Dujuan Hoosan, an Arrernte Aboriginal boy living in Alice Springs – running around at nighttime with a canister of exploding fireworks in his hand. A fantastic discharge of orangey-yellow colours light up the darkness, Hoosan swinging the canister around with an elated look on his face.

Newell has been painting vivid pictures of interesting people since her first documentary, the aesthetically rough but affecting 52-minute film Richard, from 2007, about a toy shop owner and Michael Jackson impersonator. Her previous full-length doco was 2015’s Gayby Baby , which depicted the day-to-day lives of children of single-sex parents.

For In My Blood It Runs, the subject is Hoosan – who speaks three languages, addressed the United Nations last September , and yet is “failing” in school, which of course is a reflection of the educational curriculum rather than his obvious intelligence. Made in close collaboration with the boy and his family (Hoosan is in fact a co-cinematographer), it follows him as he navigates the inequality of the education system.

In that early arresting moment, Newell (also a cinematographer) frames the scene beautifully: first with intentional blurriness – bursts of colour appearing like circular baubles, glowing as they float in the air – then with sharp focus, capturing the boy and his countenance. A frosty cynic (not me, ever) might argue this is a simplistic trick: an easy way of achieving visual aplomb by lighting something on fire and making sparks literally fly.

The scene however is about much more than pyrotechnics and sets the mood going forward. As the fireworks fizz and fly, the director cuts to quick shots of archival footage. We see, ever so briefly, as if dancing on the edges of our perception, vision of Arrernte dancers (who are relatives of Hoosan) from Santa Teresa mission in the 1950s, and a clip from On Sacred Ground – a 1980 documentary about the Noonkanbah dispute , in which Indigenous protestors fought against mining in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Hoosan speaks about memory and history (“I just felt something ... in my blood it runs”) before Newell returns to the last sputter of fireworks coming out of the canister.

This moment reminded me of a scene from the director Benh Zeitlin’s poetic 2012 drama Beasts of the Southern Wild, set in the backwaters of Louisiana. In it the protagonist – a young girl named Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis) – also gleefully runs around with light-spitting fireworks in both hands, an image so striking it was used on the poster.

Beasts is a fictional feature and Newell’s film an observational documentary. However they share some similarities. Both for instance are steered by young subjects living in impoverished communities, who view privileged, predominantly white society as a fantasy land or bizarro world – somewhere forever in the distance, unattainable and even unvisitable, like the end of a rainbow.

In another early scene from In My Blood It Runs, Hoosan and some friends – who are residents of Hidden Valley Aboriginal Town Camp – look out from a hill on to Alice Springs, observing a side of the town where “all the rich men comes” with their “clean houses” and “good front, good neighbours”. Like other portraits of remote Indigenous communities (such as Molly Reynolds’ 2015 documentary Another Country and Ivan Sen’s 2011 drama Toomelah), Newell makes a powerful point that there is no one version of Australia; no single country we all experience. The Australia each of us knows differs dramatically according to our place and privilege.

Shot in Mparntwe (Alice Springs), Sandy Bore Homeland and the Borroloola community in the Northern Territory , like most ob-docs, In My Blood It Runs has an unhurried, slice-of-life way about it, capturing daily routines such as Hoosan going to school and hanging around at home.

Even at this young age he is acutely aware of social injustice and the harsh treatment of Indigenous youth in the Northern Territory. After watching a harrowing Four Corners investigation into Indigenous youth incarceration, Hoosan’s aunt warns her nephew that going to juvenile prison means “you’re only going to end up in two places: a jail cell or a coffin” – a hell of a conversation to have with a 10-year-old.

Despite such a heavy context, the tone of the film is soft and pensive rather than polemical, constructed with a lightness of touch. It is often inspirational, in a quiet sort of way, and this is derived almost entirely from Hoosan himself.

Building trust and willingness with subjects – leading them to open up to the camera and reflect on their lives and circumstances – is the great unseen art of the documentarian. Almost always the more a film-maker succeeds, the more transparent and effortless the result appears.

In My Blood It Runs is Newell’s best film yet. It feels like a turning point: the director’s aesthetic choices reflecting the contents of her subject’s character in different and exciting ways. Nothing, for me, visually encapsulates the wide-eyed Hoosan’s presence more than that early moment with the fireworks. Visually simplistic? Maybe. A beautiful distillation of his young character? Absolutely.

In My Blood It Runs is released on 28 October in UK cinemas, and is available on digital formats in the UK and Australia .

- Australian film

- Indigenous Australians

- Documentary films

- Australian education

- Indigenous incarceration

- Alice Springs

- Northern Territory

Most viewed

American Documentary

Discussion guide, in my blood it runs discussion guide, film summary.

POV acknowledges the unceded lands of the many First Nations people, upon which we live, work and tell stories. We also acknowledge the unceded lands of the Arrernte and Garrwa people in Mparntwe and Borroloola, Australia, where this film was made. We pay our respects to all their elders past present and emerging.

FILM SUMMARY

Ten-year-old Arrernte Aboriginal boy Dujuan is a child-healer and a good hunter and speaks three languages. Yet Dujuan is failing in the Australian school system and facing increasing scrutiny from welfare authorities and the police. As he veers perilously close to incarceration, his family fights to give him a strong Arrernte education alongside his western education. We walk with him as he grapples with these pressures and shares his truths.

This guide is an invitation to dialogue. It is based on a belief in the power of human connection and designed for people who want to use In My Blood It Runs to engage family, friends, classmates, colleagues, and communities in conversation. In contrast to initiatives that foster debates in which participants try to convince others that they are right, this document envisions conversations undertaken in a spirit of openness in which people try to understand one another and expand their thinking by sharing viewpoints and listening actively.

The discussion prompts are intentionally crafted to help a wide range of audiences think more deeply about the issues in the film. Rather than attempting to address them all, choose one or two that best meet your needs and interests. And be sure to leave time to consider taking action. Planning next steps can help people leave the room feeling energized and optimistic, even in instances when conversations have been difficult.

For more detailed event planning and facilitation tips, visit https://communitynetwork.amdoc.org/ .

A NOTE TO USERS

Dear POV Community,

We are so glad you are facilitating a discussion inspired by the film In My Blood it Runs! Before you begin, we’d like to encourage you to prepare yourself for the conversation as this film invites you and your community to discuss the experiences of Indigenous people in Australia and America and that conversation requires a learning and unlearning about the truths of our history that have not been typically taught in schools and universities. If they have, they may have been taught in ways that marginalise First Nations perspectives. As such, it is not uncommon for anyone learning about the experiences of Indigenous people for the first time to feel unsure about how to approach discussing the violence committed against First Nations peoples, or about how these ongoing injustices continue to have an impact today. This guide, and our additional resources offer educational materials that will support you in your process of challenging assumptions and recognising the need for more critical and intentional learning. We encourage you to educate yourself as much as possible. Our Helpful Definitions and Concepts and our Delve Deeper Reading List is a great place to start! Additionally, you can visit the In My Blood it Runs website for a wealth of information that has been co-created with cultural advisors, film participants, and the communities represented in the film. As a facilitator we hope you will take necessary steps to ensure that you are prepared to guide a conversation that minimizes harm, while maximizing critical curiosity, growth, and connection. We invite you to share some insights with us about how your conversations fostered transformation in your own community!

Key Participants

Dujuan Hoosan - Ten-year-old Arrernte/Garrwa boy who is a child healer and speaks three languages.

Nana Carol Turner - Dujuan’s maternal grandmother, elder, and a collaborating director of the film. She is a strong advocate for Arrernte language revitalization and against the Australian foster care system that takes Aboriginal children from their families.

Megan Hoosan - Dujuan’s mother who highlights how she loves, cares, and advocates for her son

Margaret Anderson - Dujuan’s paternal grandmother, elder, and a collaborating director of the film. She is an advocate for Arrernte community led schools and against the Australian juvenile detention system.

James Mawson - Dujuan’s Father and is also a collaborating director on the film.

In My Blood It Runs is an excellent tool for outreach and will be of special interest to people who want to explore the following topics:

- Language Revitalization

Settler Colonialism and Schooling

- Elder Knowledges/Community Knowledges

- Systems of Discipline and Punishment

- Land and Country Sovereignty

- Aboriginal Activism and Rights

- Embodied ways of knowing and being

- Aborigional and Indigenous Educational Resurgence

- Restorative Justice & First Nations Systems of Justice

- Epistemology : refers to ways of knowing, the nature of knowledge and truth and inquires about the sources of knowledge. A theory of knowledge that can be contextualized, geopolitical, embodied, an act of resistance and disobedience, and influenced by power.

- Pedagogy: refers to the practices and methods used for teaching and learning within school systems and community and family learning spaces.

- Racialization: Multiple ongoing processes of racial formations linked to macro political, sociological, and economic contexts that are then attributed to groups of people. These racial formations are socially constructed.

- Reciprocity: refers to the ways people care for one another, care for the environment, show gratitude without an endpoint in mind. It is dependent on establishing relationships that are respectful not just with humans, but also with more-than-human kin (i.e. Land, water, cosmos, ancestors).

- Relationality: refers to relationships with people, relations with the environment/Land, relations with the cosmos, and relations with ideas. Indigenous peoples identity is grounded in their relationship with the land and their ancestors.

- Settler Colonialism: The invasion of a territory that is already occupied and an act that uses violence, institutions, and force to justify that occupation. Therefore, it is a structure that involves the practice of taking Indigenous lands, denying Indigenous rights to those lands, and forming government and communities on those lands.

- Colonialism: A system of control by a country over an area or people outside its borders; the establishment, exploitation, acquisition, and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. This includes the exploitation of resources and enslavement of people.

- Aboriginal & Indigenous: Both are collective terms used to describe the original peoples of the land and their descendants. All Indigenous Nations have words in their own language that they use to define themselves, therefore use the term that Indigenous people chose to use themselves.

- Western/Colonial schooling and knowledge: Schooling and knowledge that comes from the Eurowestern tradition and was forced onto Indigenous nations during colonialism. Usually Eurowestern schooling focuses on objective truths and “official” knowledge which does not allow for other ways of thinking and learning.

- Country, Land, territory : refers to a living entity with a consciousness. For First Nations communities their connection to the Country forms the essence of their identity, ways of knowing and being, culture, and spirituality.

- Education (system): refers to the ways the Australian education system, the colonial education system, or mainstream education fails Indigenous children. This system teaches a settler/colonizer history and reinforces a settler/colonizer language.

- Medicine and healing: refers to the sacred traditional health practices, approaches, knowledge, gifts, and beliefs of Indigenous peoples. The ways that they integrate their Indigenous knowledge of traditional healing for the wellness and healing of their community and more-than-human kin. This can be inclusive of ceremony, plant medicine, prayer, stories, songs, music, being in relation, physical/hand techniques, etc.

- Arrernte: Aboriginal people who live on Arrernte lands or whose ancestors are original to Arrernte lands (territory in Australia) and who through self-determination continue to revitalize their languages and cultural practices.

- Historical memory: it refers to narratives and histories that are shared through familial memory, spiritual memory, embodied memory, dreams, stories, etc.

- Ancestral homelands : refers to the Lands that Indigenous peoples ancestors are original to. As descendants, Indigenous peoples continue to honor and be in relation with their ancestral homelands which include their relations with animals, plants, waters, skies, and each other.

- Sovereignty: refers to a nation’s right to self-govern and establish their own laws and citizenship. Sovereign nations practice their cultural traditions, ways of knowing and being, and determine their own future.

- Storytelling and stories: refers to an oral tradition that has been used to pass knowledge from generation to generation. This knowledge, theories and ways of knowing and being are essential for Indigenous people to teach and learn about their relationships, cultural ways, sacred stories, history, values, spirituality and more.

- Settler and/or colonizer: refers to those who want the land, come to stay, and permanently occupy and assert unlawful ownership over Indigenous Sovereign Lands.

- Indigenous resurgence: An intellectual and cultural movement that shifts from settler colonial narratives and reframes and redirects towards Indigenous traditional cultural practices. It refers to Indigenous methods of political resurgence grounded in Indigenous thinking, theorizing, and Indigenous intelligence.

They ask us to make our children ready for school, but why can’t we make schools ready for our children. Margaret Kemarre Turner, Arrernte Elder and Film Advisor

What is the film about?

In My Blood It Runs offers a critical perspective on Aboriginal experiences and ways of knowing and being, as well as, the ways that western schooling systems negatively (and oftentimes, violently) affect Aboriginal youth. The film depicts the struggles of many Aboriginal communities, both historically and contemporarily, in the colonial nation-state of Australia. The removal of Aboriginal youth through the foster care system, erasure in curricula, the relationship between schooling and incarceration of Aboriginal youth, and the illegal occupation of Aboriginal Country are key components that the documentary addresses. Additionally, this film highlights the creative strengths of indigenous and ancestral knowledge, the care-based practices of Dujuan’s community, and the wisdom of young people. Although Australia recognizes Aboriginal and First Nations people, Aboriginal People’s fight for sovereignty and recognition are not taken seriously and often regulated by state control (Moreton-Robinson, 2020). Additionally, schools as institutions are connected to (and shaped by) histories of colonization, and as Aboriginal scholars and educators remind us that ongoing colonial and racist perceptions of Aboriginal identity impact Aboriginal youth’s educational experiences (Shay and Wickes, 2017). Like schools in the United States, education systems in Australia have an ongoing legacy of racism, especially toward Aboriginal youth, although many educational agencies proclaim that there have been big strides in eradicating racial tensions within schooling (Bodkin-Andrews and Carlson, 2016).

In My Blood it Runs center’s Dujuan’s story and experiences, and in doing so reframes the way this story about an Indigenous community is told. By centering the experience and wisdom of an Aboriginal youth, this film resists centering the colonizers’ perspective and refuses deficit-based stereotypes or prejudice embedded in colonial histories. Dujuan is an Arrernte child healer and a student in the Australian schooling system who is labeled as a “bad” and “failing” student by his white teachers. Throughout the film we see the ways that Dujuan’s family remains committed to his Arrernte education alongside his western education. In My Blood It Runs demonstrates the important role elders and family members have in advocating and fighting for Dujuan and other Arrernte youth to learn the Arrernte language and sustain their culture (Paris & Alim, 2014). The film was created through the collaborative partnership amongst Dujuan, his family, Advisors chosen by Dujuan’s family including Arrernte Elders, film producers, Sophie Hyde, Larissa Behrendt and Rachel Naninaaq Edwardson and film director Maya Newell. While the film was made on unceded territory in Australia, the themes, concerns, and structural issues facing Indigenous people it presents can (and should) be considered in the context of Indigenous peoples in Turtle Island, unceded territory now considered America/United States.

What themes will the film surface? There are four overarching themes that the film addresses: Elder Knowledges and Language Reclamation & Revitalization, Settler Colonialism and Schooling, Disciplining and Incarceration, Indigenous Sovereignty and Country (Land) Relations, and self determination. In the following sections viewers are provided with a more detailed introduction to each theme.

Elder Knowledges and Language Reclamation

The United Nations declared 2019 as the international year of Indigenous languages and extended this proclamation as the decade of Indigenous languages to span from 2022-2032 (UNESCO, 2019). UNESCO’s goal is to bring awareness about the importance of Indigenous languages and the linguistic rights of Indigenous peoples. It is critical to recognize that these language revitalization efforts are more than just protecting a language, but Indigenous languages are interdependent with Indigenous peoples sovereignty, Land relations, ways of knowing and being in the world, and cosmologies. Said another way, language is a small (but crucial) part of a whole way of naming, knowing, relating, living, being, and thriving in the world. Hermes, Bang, and Marin (2012) ask, “Would it be better to invent new Ojibwe words to describe educational, standardized concepts like "triangle" or to challenge the standards to accept the Ojibwe morphemes of shape?" (pp. 388). Thinking with the above quote in relation to language revitalization projects, it is evident that the goal is not to have students learn to speak a standard version of Ojibwe, but through language to connect to their specific geographical landscape, Land, home, and community (Hermes et al., 2012). Marrisa Muñoz (2018) states that “for first peoples, a relationship with the Land serves as a foundation for all knowledge” and that “within each Indigenous language is a specific, nuanced understanding of how life is related within their specific ecology” (pp. 67). Language is always in tune with the cycles of nature, one that does not follow a western logic of control despite the dominance that western languages and structures have to dictate what comes to be known as the standard. Therefore, language reclamation is not meant to center western understandings of language that focus on proficiency of semantics, phonemes, syntax, and grammar. This type of standardized language will never be able to assume the legacies of Indigenous knowledge systems and relations to the Land. Instead, a language reclamation (McCarty & Nicholas, 2014) approach to language and culture is about the knowledge that is carried through the songs, stories, prayers, sciences, oral and artistic traditions, and values learned through “doing and being” (pp. 111). These language reclamation projects should be Indigenous led and guided by Indigenous elders because of their wisdom and knowledge.

In the film In My Blood It Runs, Nana Carol, Dujuan’s maternal grandmother, demonstrates the ways she and other Arrernte elders engage in language reclamation efforts. She is aware that in his western education Dujuan is not going to be taught his language. Nana Carol believes it is critical for Dujuan to practice Arrernte and be proud of his Aboriginal upbringing and ancestry. Elders play an important and pivotal role in language reclamation efforts and disrupt narrow understandings about learning only occurring in schools with certified teachers. For example, she embraces Dujuan’s healing gifts, and reminds him that he has the ability to (re)member and pass on his knowledge and help his community. She also encourages Dujuan and other young ones to practice Arrernte through the tradition of storytelling and learning with the Land. Throughout the film Nana Carol talks about the importance of teaching the Arrernte language because it is tied to Aboriginal culture, traditions, and their ways of knowing and being in the world.

Scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith notes that it is important to remember that colonialism is not only about the collection of “new discoveries” that were stolen and taken from Indigenous peoples to be kept in museums, libraries, and universities. Colonialism is also about the “re-arrangement, re-presentation, and re-distribution” (Smith, 2013; p. 62) of knowledge, the multiple ways it manifests, and how Indigenous peoples have been and continue to be affected. Settler colonialism is the invasion of a territory that is already occupied and an act that uses violence, institutions, and force to justify that occupation. Therefore, settler colonialism is a structure, not an event (Wolfe, 2006). For example, history textbooks used in schools are full of dominant narratives that are written from the colonizers perspective and center settler actions as innocent, brave, and justifiable, and in the past. These accounts of history written by settlers, become the “official” curriculum in schools and contribute to Indigenous erasure and violent ideas of settler superiority. Settler colonialism in school systems also manifests itself in violent ways through “curriculum built specifically around the aim of cultural annihilation” which embodies a form of “curricular genocide” (Au, Brown, Calderon, 2016; p. 43). Curricular genocide attacks Native children’s identities in physical and symbolic ways through attempts to assimilate them and teach them that their culture is inferior to white culture (Au, Brown, Calderon, 2016). Despite a long history of colonization with regards to schooling and educational institutions and opportunities (see histories of Native Boarding Schools ), Indigenous children and youth have and continue to resist and enact their agency.

The film In My Blood It Runs, sheds light to what Lomawaima and McCarty (2006) state that Indigenous peoples have always “carefully designed educational systems” (p. 27) to transmit their complex bodies of knowledge. Dujuan is portrayed as a “bad student” in his western school classroom, while in his Arrernte community he is recognized for his healing gifts, speaking three languages, and continuing the legacies of ways of knowing and being of his ancestors. In the film, Dujuan’s wisdom, gifts, and ancestral knowledge are obvious strengths that are overlooked, denied, or misunderstood by his white teachers. There are various moments in the film when Dujuan explicitly mentions that Australia is Aboriginal Country (Land) and that in school they teach him white peoples version of history. Dujuan demonstrates a level of deep consciousness and wisdom in the ways he critiques the school system and how it attempts to assimilate him. However, his criticism of the curriculum he is taught is understood from the teacher and administrator perspective as “bad behaviors” and thus, puts Dujuan at risk of being taken from his family and put in foster care.

Disciplining Policies & Incarceration

Discipline in schools has been well documented and continues to be a discourse within schooling systems. Racialized students in particular, are dehumanized and criminalized almost immediately when they enter the school and are trafficked into systems of incarceration that include juvenile detention centers, jails, and even prisons (Love, 2014). Bettina Love (2016) gives an example of Black youth being subjected to this state-sanctioned violence, when a six-year old Black girl was handcuffed and then taken to the police station because the young girl was having a tantrum at school. Not only is this act sanctioned by schools, they are so normalized within education systems that handcuffing a young Black girl is no longer seen as violent and racist, but a part of disciplining procedures. With the history of Native American Boarding schools, the use of fear, intimidation, and violence was a common practice within these institutions (Grande, 2015). In particular, schools were seen as a way to eliminate Indigenous peoples since Native American boarding schools prohibited Native youth from speaking their language, practicing their cultural beliefs, and from wearing their traditional clothing and regalia. Even to this day, in the United States and around the world students continue to be banned from wearing their First Nations and traditional clothing. As Sandy Grande (2015) explains, “Indian education was never simply about the desire to ‘civilize’ or even deculturalize a people, but rather, from its very inception, it was a project designed to colonize Indian minds as a means of gaining access to Indian labor, land, and resources” (p.23). Even though the above examples are from the United States, Aboriginal Australia is also impacted by western education and we see parallels on how schools as colonial institutions have deep colonial and racist histories, masked as “procedures of disciplining”, that continue to affect students today. In the film, we see different approaches to “misbehavior” and discipline - one from the educational system that threatens to send Dujuan to foster care and another from his community.

The experiences of how discipline is taken up from the perspective of the colonizer (i.e. teachers and schools) juxtaposed to an Indigenous context (Dujuan’s community) offer important insights into different ways of knowing and being in the world. For example, misbehavior in the classroom is judged from Dujuan, as a student, resisting what he is told is the “good” way to behave or questioning the ways that the lessons do not include his ancestral knowledge and experiences. It is apparent that within the classroom colonial practices are still present. We see connections in the discipline tactics are structures that are informed by intimidation and demands for youth to assimilate to parameters of “good” or “bad” as determined by state-sanctioned agencies that have histories of removing Indigenous children from their families and ancestral homelands. Juxtaposed with this, is the way that Dujuan’s family understands what his “misbehavior” communicates to them and their ways of responding. When he runs away from the camp, for instance, his community understands this as a call that Dujuan needs support, and that they are accountable for the healing that he needs in that time. Ultimately, the differences between settler knowledge of discipline and punishment and the example of Indigenous knowledge practices that speak to community care and healing, are illuminated in the context of behavior and schooling. In the settler context, Aboriginal youth are threatened by an education system that does not learn from their wisdom, or consider their insights on how to remake and educational environment that centers Indigenous knowledges, experiences, and ways of being in the world.

Indigenous Sovereignty and Country (Land) Relations

Just because Indigenous and Aboriginal people have been forcibly removed from their territories, does not mean that the Country (Land) is no longer Aboriginal or Indigenous. Therefore, all Country (Land) that people reside on in Australia, U.S., Canda, Brazil, Chile, etc. have always and will always be sovereign Indigenous territories. Although under state control, many Aborignial and Indigenous people are still in legal fights to recuperate their ancestral territories. Therefore, people who are not ancestrally from Aboriginal Australia or Indigneous Lands are guests and are settlers. Often there is a narrative of how settlers need to be conscious and make a home with their environment and to take care of their surroundings. However, this narrative is clouded by the fact that Aboriginal and Indigenous People have always had a relationship with that environment and that it is the settler who must contend with their presence on already occupied Indigenous land. In other words, there cannot be “shared futures” with settlers if there is not a deep interrogation of the social and political project of settler colonialism and the social and historical contexts of places (Bang et al., 2014; Nxumalo, 2019). In order to truly be in solidarity and in relation with Aboriginal and Indigenous people, educators need to be explicit in addressing settler violences; be clear about the diverse aims of decolonization; and be very intentional in understanding the dynamic ways of knowing and being that are specific to understandings of land by Indigenous peoples (Tuck, McKenzie, McCoy, 2014, p.14). This responsibility is often left to the educator, since teacher training programs continue to operate from settler perspectives and normalize the erasure of Indigenous perspectives on sovereignty.

In My Blood It Runs is a powerful example of how Aboriginal People are fighting for their right to be seen as sovereign nations. Aboriginal People continue to have a strong relationship with their ancestral territories and we gain insight into this relationship by the way Dujuan and his family talk about going to the Country. Dujuan explains that it is important to go to the Country and stay connected because of the medicine and teachings that are good for him and the Aboriginal people. Therefore the fight for sovereignty in Aboriginal Australia, as well as other places in the world, is a fight to preserve and sustain their relationships with Country. The Country is representative of Aboriginal people’s connection to their identity, spirituality, family, language, and culture regardless if they live in the Country or in an urban place. Due to the displacement, dispossession, and forced removal from ancestral Lands, Aboriginal people continue to assert their sovereignty through their connection to the Country. The real question for those who are settlers is, are you willing to give back the Land and Country that is not ancestrally yours? Are you ready to fight alongside Aboriginal and Indigenous people, regardless if that means relinquishing your settler privileges? Who are you in relation to the already occupied Aboriginal Country and Land?

BEFORE BEGINNING THE DISCUSSION: We encourage you to practice a Land Acknowledgment before you begin the conversation. In this way, you will frame the conversation in respect and care for the Indigenous people and communities whose land you are occupying; and you will provide a model for your community. To learn more about Land Acknowledgment practices, to find language to use in your Land Acknowledgment, you can use this resource.

PROMPT ONE: STARTING THE CONVERSATION

Immediately after the film, you may want to give people a few quiet moments to reflect on what they have seen. You could pose a general question (examples below) and give people some time to themselves to jot down or think about their answers before opening the discussion. Alternatively, you could ask participants to share their thoughts with a partner before starting a group discussion.

- If you were going to tell a friend about this film, what would you say?

- Describe a moment or scene from the film that you found particularly striking or moving. What was it about this scene that was especially compelling for you?

- If you could ask anyone in the film a single question, whom would you ask and what would you want to know more about?

- Did anything in the film surprise you?

- What aspects of the film felt relatable? What felt familiar? If nothing, then what felt new and unfamiliar?

- Can you think of a time in your life when you held an implicit or explicit racist belief? Upon reflection, where did those implicit ideas come from and/or how were you taught to think that way?

- What does learning about stories of Aboriginal children such as Dujuan make you wonder about the experiences of Native American children and youth in the United States?

- What was your experience learning about First Nations history or Native American history in schools in the United States? How have your thoughts changed after viewing In My Blood it Runs ?

PROMPT TWO: Elder Knowledges and Language Reclamation

A central character to the film was Nana Carol, an Arrernte elder, who is Dujuan’s maternal grandmother. Throughout the film you see how she embraces Dujuan’s healing gifts and see’s Dujuan as an important part of Aboriginal futures. These futures include young ones knowing and honoring their language because it is interconnected with their Country (Land) relations. Therefore, she advocates for Arrernte led schools that include the elders and the community and teach the importance of revitalizing their language. Discuss the following questions on these connections between elder knowledges and language revitalization.

- Do you have any elders in your life that have encouraged you to remain close to certain types of knowledge, lessons, or traditions?

- Nana Carol and Dujuan just arrived in their homeland. Dujuan says in Arrernte, “I’m coming to homeland” and Nana Carol says, “you mean coming back” and encourages him to say it again in Arrernte. Do you speak a language original to your homeland? Why is it important to think about language in relation to the territory or homeland?

- In what ways do you understand the commitment to Arrernte language practices to be important in the lives of the children?

- In what ways is Nana Carol a teacher? How is she different from the teachers in Dujuan’s schooling environment?

- Are schools always supportive of familial and cultural practices?

- In what ways should schools be more attentive to cultural knowledge and why?

PROMPT THREE: Settler Colonialism and Schooling

Although not explicitly mentioned in the film, we see aspects of settler colonialism, which is the invasion of a territory that is already occupied and an act that uses violence, institutions, and force to justify that occupation. As Dujuan explicitly mentions, Australia is Aboriginal Country (Land) and therefore Aboriginal people are the rightful inhabitants of what is now known as Australia. Schooling, as an institution, is not benign and is in fact a culprit of settler colonialism as we see how schooling creates categories of who is a “bad student” that ultimately affect Aborignal youth. The removal of Aborignal youth from their families by foster care relies on school “performance” to finalize these removals; an act of settler colonialism and Aboriginal displacement. Discuss the following questions on these connections between settler colonialism and schooling:

- What were you taught about First Nations history at school? Should our education and history lessons include the Black Lives Matter movement and what it means for Black people, People of Color and First Nations people?

- Are there elements of your identity you feel mainstream society does not honor? How do you think your educational journey would have differed had you been forced to learn in a language other than your own? Are you confident you would have had the same experience in school and beyond?

- Dujuan talks about the memory and history that runs in his blood. Why is this history not legitimized in school? What is the purpose behind the erasure of his Aboriginal history?

- Why does Dujuan have to live far away from his ancestral homelands to get an opportunity to attend school?

- Nana Carol wants her children to be educated, “so that they know the system when they grow up.” What system is Nana Carol talking about? Why do you think this matters to her?

- What are the potential impacts of teaching history from one perspective and presenting it as factual?

- Why is it important to think critically about who is telling the story of the past?

- How does Dujuan describe the history he learns at school compared to the history he learns at home? How does the history learned in his Australian school strengthen the ongoing legacy and impacts of settler colonialism in schooling?

- Have you ever felt that curricula in schools didn’t quite fit your identity? Can you imagine a scenario in which that might be the case? Why or why not?

- Dujuan and his peers are told by the teacher that a standardized test is just like a coloring activity. What do you think about this? What are the implications of this definition about standardized testing?

- Why is it that for Abriginal families, maintaining their family together, and avoiding the foster care system, depends on school performance within a western education system?

PROMPT FOUR: Disciplining Policies & Incarceration

In the film you see multiple ways that Dujuan is being disciplined. For example, he is sent to the “time-out corner”, intimidated by the principal about the foster care system, and is expelled from multiple schools for his “behavior”. Additionally, we see how the education and foster care system work in conjunction to send young Aboriginal youth into the foster care system which leads into forms of incarceration. Discuss the following questions to engage in a dialogue about disciplining policies and incarceration practices.

- What is your memory of being 10 years old? Could you imagine being incarcerated at this age, or as an adult? How would this affect your life, family, work relationships?

- What do school officials and other officers say about Dujuan regarding his “behavior” in school? In what ways is their “official” descriptions of his behavior harmful or short-sighted?

- What disciplinary actions are taken to address Dujuan’s “behavior”? How are these disciplinary actions out of alignment with his home community’s response? What can you infer about the differences between the way westernized knowledge frames behavior and care and indigenous ways of knowing the same behaviors?

- In what ways can we see Dujuan’s identity as an Aboriginal healer come into tension with the schooling system? Why do you think these tensions exist? In what ways could the schooling system be more equitable and supportive of Dujuan as an Aboriginal youth?

- How are the police, jail and/or prisons, and school discipline related, especially when we think of their response to underrepresented students (Aboriginal, Indigenous, Black, poor, LGBTQ+)? What relationships can you draw between the practices of schools and criminal justice institutions?

- Think about these following words: misbehavior, trouble-maker, delinquent, bad student, at-risk. Where do you think these words come from? How do schools use these words to label students? In what ways are these labels connected to colonizer’s knowledge practices and power?

- To conclude the film, Dujuan’s family decide to send him back to his father’s ancestral homelands. In what ways is going back home to his Lands a form of education? What do you think he will learn being back home that he wouldn’t be able to just by going to school?

PROMPT FIVE: Indigenous Sovereignty and Country (Land) Relations

In the film you see and hear Dujuan and his family talk about going to the country. Dujuan explains that it is important to go to the Country and stay connected because of the medicine and teachings that are good for him and the Aboriginal people. The Country for First Nations peoples is more than just a place to visit. Rather, the Country is representative of Aboriginal people’s connection to their identity, spirituality, family, language, and culture regardless if they live in the Country or in an urban place. Due to the displacement, dispossession, and forced removal from ancestral Lands, Aboriginal people continue to assert their sovereignty through their connection to the Country. Discuss the following questions to engage in a dialogue about Indigenous sovereignty and Country (Land) relations.

- Have you ever considered what traditional lands you are currently living on? Why or why not?

- Explain some of the ways that the Arrernte/Garrwa community in the film have a relationship with their ancestral homelands?

- How can this knowledge also be applicable where you currently live? Why is it important to develop a relationship with the land that you are currently occupying and what can you do with that knowledge?

- How is language and culture related to identity, education, and learning? Think about what the elders say in the film and why Dujuan goes back to his ancestral homelands.

- Who are the original peoples from where you live, what are some of their stories, and where are they now? Why is it important, wherever you are, to acknowledge the original people of that territory/land/place?

In My Blood It Runs is not just a film, it’s also a campaign for change. The Arrernte and Garrwa families and communities behind the film have guided a multi-year plan that dovetails the film release. You can support their solutions by backing their campaign focusing on three main goals: education reform, juvenile justice reform and anti-racism. Learn more at: www.inmyblooditruns.com/takeaction

We encourage you to seek out and discover more information about the Indigenous territory you are currently occupying. Here is a tool to learn more: https://native-land.ca/ .

You can also initiate a dialogue between a local Indigenous community organization or leader(s). This could look like having participants suggest Indigenous community members that they already know and/or researching the history of Indigenous people in their local area and then create a letter, email, or action plan to initiate communication between them as community members and the respective Indigenous community member/organization.

Thinking of your sphere of influence or networks, how can you support the agency of First Nations communities? This could be reading a book, donating to First Nations led cause or signing a petition. How can you practice allyship in your daily life?

- IIYC - an international organization centering Indigenous youth voices and supporting Indigneous communities through activism, education, and ceremony.

- Native-Land.ca | Our home on native land - Native Land Digital is a Canadian not-for-profit organization, incorporated in December 2018. Native Land Digital is Indigenous-led, with an Indigenous Executive Director and Board of Directors who oversee and direct the organization.

- Native American Children's Literature Recommended Reading List - A PDF of Indigenous literature created by the First Nations Development Institute

- Indigenous Comic Con - Comic Con highlights the best in Native and Indigenous pop art and Indigenerdity.

- Indigenous Cheerleader - Their mission is to REMEMBER, RECLAIM and RESTORE Indigenous languages and cultures to help create a better and more culturally-sustaining education for children and beyond.

- Indigenous Education Tools - A program designed to develop resources and practices that will have exponential impacts on efforts to improve Native student success across a variety of sectors.

- Home | SBI - Sovereign Bodies Institute (SBI) builds on Indigenous traditions of data gathering and knowledge transfer to create, disseminate, and put into action research on gender and sexual violence against Indigenous people.

- Seeding Sovereignty - An Indigenous-led collective that works to shift social and environmental paradigms by dismantling colonial institutions and replacing them with Indigenous practices created in synchronicity with the land.

- Settler Colonial City Project - a research collective focused on the collaborative production of knowledge about cities on Turtle Island/Abya Yala/The Americas as spaces of ongoing settler colonialism, Indigenous survivance, and struggles for decolonization.

- The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition - Their vision is focused on Indigenous and cultural sovereignty. Their mission is to lead in pursuit of understanding and addressing the ongoing trauma created by the US Indian Boarding School policy.

- Indigenous Children’s Survivance in Public Schools by Leilani Sabzalian - In this book, Leilani Sabzalian counters deficit framings of Indigenous students. One of her goals is to develop educators’ anticolonial literacy so that teachers can counter colonialism and better support Indigenous students in public schools.

- An Indigenuos People’s History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz In this book, Dunbar-Ortiz adroitly challenges the founding myth of the United States and shows how policy against the Indigenous peoples was colonialist and designed to seize the territories of the original inhabitants, displacing or eliminating them.

- As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance by Leanne Betasamosake Simpson

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

- We are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom - Inspired by the many Indigenous-led movements across North America, We Are Water Protectors issues an urgent rallying cry to safeguard the Earth’s water from harm and corruption—a bold and lyrical picture book written by Carole Lindstrom and vibrantly illustrated by Michaela Goade.

About The Authors

Pablo Montes Pablo Montes is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin in the Cultural Studies in Education Program. He is the son of migrant workers from Guanajuato, Mexico, the ancestral territories of the Chichimeca Guamares and P'urhepecha. He currently serves as the Youth Director for the Indigenous Cultures Institute with the Coahuiltecan community in the Lands of Yana Wana (spirit waters of central Texas). Additionally, through a generous grant by the University of Texas at Austin’s Green Fund, he is working with co-author Judith Landeros and other Indigenous people to create a Land Based Education Curriculum. His interests include the intersection of queer settler colonialism, Indigeneity, and Land education.

Judith Landeros Judith Landeros is a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin studying Cultural Studies in Education with a focus on Indigenous girlhood, traditional healing knowledge, and schooling. Her family is from Michoacán and Jalisco, the ancestral territories of the P’urhepecha and Chichimeca. She is a former bilingual early childhood teacher and advocates for the inclusion of Critical Indigenous Studies, Ethnic Studies, and Land as pedagogy within teacher preparation education programs.

Thank you to all who reviewed and contributed to this guide:

Maya Newell, Director of In My Blood it Runs

Rachel Naninaaq Edwardson, Producer of In My Blood it Runs

Rachel Friedland, POV Senior Associate, Programs & Engagement

Discussion Guide Producer, POV

Courtney B. Cook, Education Manager

This resource was created, in part, with the generous support of the Open Society Foundation and the MacArther Foundation.

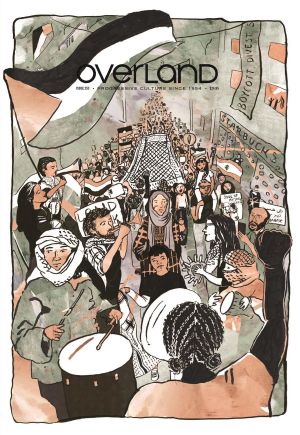

Overland literary journal

- The Journal

253 Summer 2023/4

Dženana Vucic on the subtle and not-so-subtle Marxist symbolism in Sailor Moon, John Docker, a "non-theatre person" by his own admission on The New Theatre, Sarah Schwartz on prison healthcare as punishment and the killing of Veronica Nelson, a poignant short story on memory and displacement from Nasrin Mahoutchi-Hosaini, Jeanine Leane's prize-winning poem, "Water under the bridge", and more.

Browse by format:

- Browse by Theme

- Browse by Author

Indigenous voices to the centre: the making of In My Blood it Runs

What could a real collaborative process look like in a landscape where colonial injustices never ended, and just continued under different names? How could a non-indigenous filmmaking team walk into such an unequal playing field, and effectively give the power back to the communities who never ceded their lands? This is how.

In My Blood It Runs was shot in Mparntwe, Sandy Bore Homeland and Borroloola Community, in the Northern Territory. It is the story of a boy called Dujuan, a child-healer being trained in the ways of the Arrernte people and a good hunter who speaks three languages. The documentary shows him getting into trouble at school and risking incarceration.

Skilfully woven into the film is archival footage of traditional owners throughout history. But even more affecting is the inclusion of more recent news footage. As Dujuan comes of age in an Alice Springs where police patrol the streets locking children into paddy wagons, the results of an inquiry into the Northern Territory’s juvenile detention systems are released, its findings devastating. Aboriginal youths are being tortured in custody. By being out after dark, Dujuan risks being locked up in the very facilities the inquiry has found to be in violation of basic human rights –and he is ten years old.

Since the film’s release, Dujuan’s message of self-empowerment and his demands for justice for Aboriginal people have been heard in various governmental settings. Dujuan addressed the United Nations about the issues Aboriginal people face in their own country. He also wrote an article for Overland .

In June, The Guardian recorded that have been 437 Aboriginal deaths in custody in Australia since 1991 . There have been more since. In My Blood It Runs offers something we desperately needed: not only a coruscating critique of the discriminatory judicial and educational systems that brutally torture and kill Aboriginal people, but the articulation of what a more constructive way forward looks like: a path towards community, and towards healing.

The documentary is also significant because of its radically collective production process. The filmmaking teams’ approach deliberately decentralises the non-Indigenous filmmaker/exoticising voyeur’s gaze, placing Dujuan in control of his own narrative, and his community in control of its own stories. I spoke to filmmakers William Tilmouth, an advisor of Arrernte descent, Maya Newell, a director and producer who previously made the award-winning Gayby Baby , and Rachael Nanninaaq Edwardson, an acclaimed Iñupiaq/Norwegian/Sami filmmaker, about their technique for actively re-distributing power.

It’s important to note here that though it’s a tendency of the mainstream press to read the non-Indigenous (to that land) filmmakers as the initiators and drivers of this project, the seeds of In My Blood it Runs were sewn by the Arrernte community. Having seen Newell’s work, they approached her about ten years ago with an invitation to film their stories. The re-distribution of power that the team aspired to stemmed from an awareness, Edwardson said, that ‘we’re the ones that were standing up and getting the money, we’re the ones that are holding the camera, we’re the ones that could easily say: ‘Sign this release form and then you give us rights to everything you have,’ which is how a lot of films get made.’

And she’s right. This is anecdotal, but when I lived in the indigenous community of Wingellina/Irruntyju, the white-run media company in the town, under pressure to tick boxes and send completed material back to funding bodies, often reverted to a straight-up dictatorial approach. Tilmouth references this style of non-Indigenous led filmmaking in this region of Australia. ‘Directors have clear ideas about how they want to portray Indigenous communities,’ he says. ‘They come in with absolutely prescriptive directives, like: ‘We want you to do this, can you learn your lines and sit still and then we’ll cut to you.’ The team behind In My Blood it Runs never did that. ‘The filmmakers never came in with a script. They never came in with a storyboard … It was organically driven and a credit to the filmmakers.’

But as idealistic and ethical this approach appears to be, how possible is it to share power in this way in a truly collaborative process? In white-dominant country, where Dujuan and his community represent one of the lowest socio and economic groups, where the language needed to secure funding for something as ambitious as a full-length documentary is most emphatically English (a second or third language for many Indigenous people of that region), and where non-Indigenous filmmakers are wielding the tools of the story-making itself, how possible is it really to overturn the non-Indigenous gaze?

Setting aside the flawed notion of an unbiased documentary-maker, and accounting for the subjectivity with which any story on screen will be shaped, even the most well-meaning crew of non-indigenous filmmakers – by virtue of their function and positioning – risk re-inscribing the same old white-dominant narratives. What could a real collaborative process look like in a landscape where colonial injustices never ended, and just continued under different names? How could a non-indigenous filmmaking team walk into such an unequal playing field, and effectively give the power back to the communities who never ceded their lands?

This is how.

Firstly, this was an Arrernte-led project whose impetus came from the community and from Dujuan himself, who serves as both our point of view and protagonist. The beginning of the documentary shows us whose hands the camera is in: Dujuan’s. He interviews his mother through a handheld screen. It’s an image that is also to be referenced in the final shot. We are invited in and ushered out by the community, for the community, and the responsibility for the shape of the film, finally, it is implied, lies in the communities’ hands.

As Newell says from the outset, Dujuan was a special kid. A kid who wanted to share his stories and be filmed. Such is his generosity, in fact, that he shares with us not just his prowess in healing and in traditional forms of knowledge, but also his struggles. At one point in the film Dujuan – who is having difficulty with a curriculum that is teaching him that Captain Cook discovered Australia, implemented and assessed in English by teachers who flagrantly ignore his questions – gets a school report. I watched this documentary with my nine-year-old son. As Dujuan’s mother opened his report, I told him Dujuan had been given the same tests as he had: that it was the exact same curriculum my son was being assessed with. What he saw next made him cry.

The willingness to share such experience and stories has to be community-led, not the other way around.

Secondly, the crew that was asked to film this communities’ story started with a question. Edwardson, herself a First Nations Iñupiaq/Norwegian/Sami person of Alaska, said that form the outset her question was: ‘We have a group of filmmakers, none of whom are indigenous to this particular country, are we even the right people to make this story?’ That fundamental question fed into how they envisioned and eventually undertook the project, which took a total of three years of filming. ‘Our North star,’ Edwardson says, ‘was making sure that we were making a film where we made space in some way for the community to control and be proud of [it] in the end; that it was a true collaboration … The trust would come if we got that part right, because that’s the hardest part to get right.’

Thirdly, the crew began with the acknowledgment of its bias. This goes against antiquated notions of documentary filmmaking, where the crew are some kind of apolitical force behind the camera. Edwardson emphasised ‘the imbalance of power and the understanding of the bias that we all carry as being raised by systems that maintain bias, so we are all subject to that until we actively try to dig that out of our worldviews and … modes of operation.’ The filmmakers actively engaged with their own biases. What this looked like in practical terms was training for everyone who was non-indigenous.

‘There’s that process of consciously setting up and training non-indigenous people in our team, and talking through the stereotypes that exist in the grand narratives that we have about First Nations people in this country,’ Newell said. ‘That allows you to have the armour to be able to face pulling them apart because everything around us tells you to tell the story in a certain way. You’re asked constantly by media to frame the story in a particular way.’

Fourthly, the team assumed and went about educating themselves to increase their cultural competence. It researched widely and hired cultural advisors, five of whom are listed in the film’s credits. And it made the community members collaborative producers: partners.

Aside from looking at the processes of peak bodies in Australia, such as Screen Australia’s protocols on indigenous filmmaking, the producers leaned on work that forms cultural safety models in Aotearoa New Zealand, and translated those protocols into filmmaking. They used ‘those two foundational pillars of cultural safety which are applicable across any space,’ Edwardson said. ‘One to understand your bias, and the power imbalance and the power in the system, and … to then increase your cultural competency alongside that. And the other is obviously to give agency over to the family and the clients and the people who are most affected.’

How did that look in practice?

With every new chunk of filming, the team went back to the community, who always retained its role as editor and shaper of its narratives. Edwardson says that although the story ‘features one boy and one family story at the front of it,’ it was taken to community meetings. The community, family and advisors saw the rushes, the raw unedited visuals and sounds from the day’s filming. Edwardson says ‘even before the rushes they did the story workshop, we did story workshops with them where we storyboarded, and we played around with ideas about how we were going to cover things, what things to cover, what things maybe not to cover, whether or not we collect this and deal with it later … at every step of the way. So the community had a hand in what that story went out.’

Newell and Edwardson both readily admit to the mistakes they made along the way. But it’s this kind of self-reflexivity that made them suitable guardians of these stories.

In white-dominant Australia, where children are seized and incarcerated and tortured, and where generation after generation of Aboriginal people are failed at school, discriminated against, locked up, and killed, In My Blood it Runs offers a both a working model for engagement and a possible way forward. Tilmouth talks about his people as people who are often prescribed inappropriate ‘solutions’. Solutions which he says are harmful and which are ‘dreamt up by people who know nothing about them.’

The only way forward is the kind of robust process used by this team. And most importantly, Newell emphasises that the only ‘solution’ for Dujuan finally in solving the problems and the threats he faces, comes from his family and from his community itself.

Michalia Arathimos

Michalia Arathimos has published work in Westerly , Landfall , Headland , JAAM , Best New Zealand Fiction Volume 4 , Sport and Turbine . Her debut novel, Aukati / Boundary Line , was published in 2019 by Mākaro Press. She is currently Overland ’s fiction reviewer.

Overland is a not-for-profit magazine with a proud history of supporting writers, and publishing ideas and voices often excluded from other places.

If you like this piece, or support Overland ’s work in general, please subscribe or donate .

Related articles & Essays

The Plains exposes the psychic terrain of Victoria’s highways

A journey into male supremacy: Robin Summons’ Victim

Overland ’s free fortnightly newsletter highlights the best of Overland online, new writing from the print journal, and regularly collates writing events and opportunities in the community.

'In My Blood It Runs' Is The Documentary Every Australian Needs To See

Did you know that in Australia, the age of criminal responsibility is only 10 years old? While Aboriginal kids only make up around 5% of kids in Australia, they make up around 60% of kids in juvenile detention across the country. In the Northern Territory, this figure jumps to a staggering 100% .

Historically, the stories of First Nations people have been mistold and misrepresented in this country. Largely, this is because they are not the people who have been allowed to tell them. Last year, an observational documentary and campaign for change called In My Blood It Runs was released. Unlike many stories that came before it, the incredible documentary follows the lead of people of colour and First Nations-led projects, handing back the agency and ownership of Aboriginal stories to the people they belong to.

Made over a three-and-a-half-year period by director Maya Newell (who you might know from her 2015 documentary, Gayby Baby ) alongside Arrernte Elders, In My Blood It Runs offers an essential insight into the importance of First Nations-led education, and the institutions that continue to fail Aboriginal kids, through the eyes of its 10-year-old star, Dujuan. Every single Australian needs to see this film .

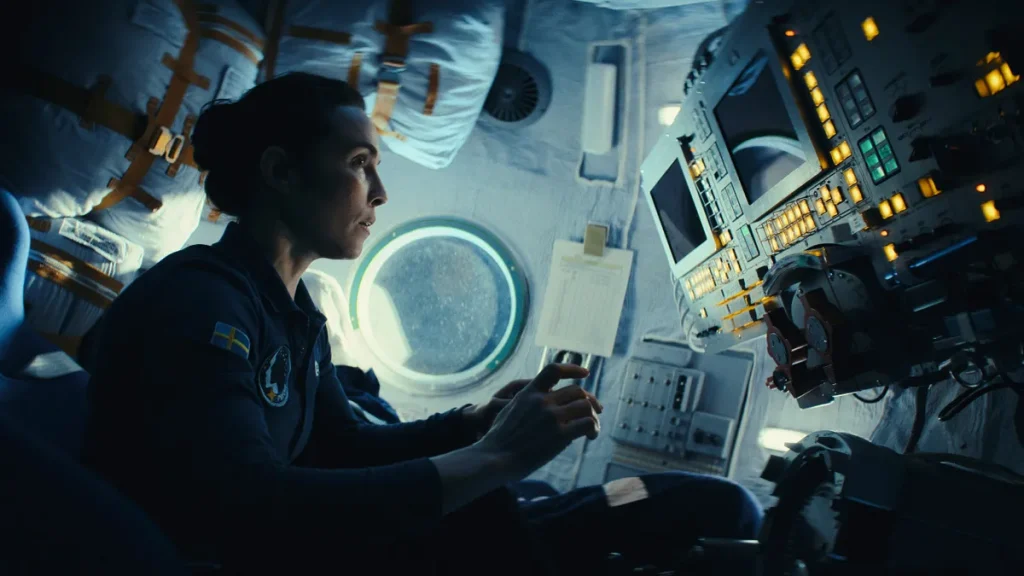

Dujuan Hoosan with his mother, Megan Hoosan. Photo – courtesy of Maya Newell.

Dujuan Hoosan, the star of In My Blood It Runs. Photo – courtesy of Maya Newell.

Dujuan celebrating one of his weekly trips out to Country . Photo – courtesy of Maya Newell.

Left: Dujuan at school, where he is misunderstood. Right: filmmaker Maya Newell with Dujuan while filming In My Blood It Runs. Photo – courtesy of Maya Newell.

The filmmaking team! Photo – courtesy of Maya Newell.

By now, you’ve probably heard of the documentary In My Blood It Runs. The film introduces Dujuan, an Aboriginal boy of Arrernte/Garrwa descent, at 10 years old – the same age of criminal responsibility in Australia. Like lots of other kids his age, Dujuan is charming and cheeky, testing the boundaries of his family’s rules and exploring his own independence. Unlike most other kids, Dujuan has a superpower – his Ngangkere – a healing power inherited from his great grandfather when he passed away, and the land. Dujuan is a strong hunter and he can speak three languages. And while Dujuan is having difficulty in the western education system, where he is misunderstood, he thrives on his weekly trips with his family and community on Country.

I was lucky to speak with the film’s director, Maya Newell , as well as William Tilmouth , an Arrernte man and Founding Chair of Children’s Ground , who worked as a key advisor on the film. We spoke about how the film came to be, the close creative collaboration between the filmmakers and the families featured, and the importance of agency and ownership by First Nations people over their own stories.

Hi Maya + William – thank you both for taking the time to speak with us. Maya, Was there a particular moment or event that motivated you to make this important documentary?

MAYA NEWELL: I suppose there are lots of moments really, but I think the important thing to say is that the film didn’t just sprout up after one moment or just meeting the family once and wanting to make a film. It sits on the bed of about a decade of relationships, and me personally being invited by Arrernte Elders and an organisation called Akeyulerre Healing Centre in Alice Springs and Children’s Ground , which are two Arrernte led organisations that support children, families and communities to stay connected to culture and have access to their homeland, and continue that important process of passing down knowledge to the next generation.

Over those years of working alongside families and getting to know them and going back and forth from Alice Springs and making a series of short films, I realised there was an important bigger story. It felt like we were making the same short films over and over again about this hidden education system, this system that has been going for 65,000 years and continues today, and that is the language and culture and identity of people that is so undervalued and not often recognised within the mainstream education system, yet is so fundamental to children’s wellbeing. I had a beautiful opportunity to learn over those years through the generosity of Elders and families.

I suppose the moment that really flipped this into considering making a longer version film for the general public was when I met Dujuan on a Ngangkere (traditional healing) camp. [Dujuan] was about 8, and bounded up and started telling me about how he got his power, his Ngangkere, from his great grandfather when he passed away, and also from the land. He was so articulate and poetic in the way he confidently described this super power that he had, and he really wanted a film made about him. So we went back with all those people we’d known for a long time and just asked those hard questions about how you would make a film like this, and if was right to make a film like this, and what was the process and the ethics to put in place to be sure that the families would really be driving it themselves.

We see in the film that Dujuan has incredible support from his family in terms of learning his language, his culture and connecting to Country. Why is that so important, and particularly for kids of Dujuan’s age?

WILLIAM TILMOUTH: First and foremost his identity will remain intact. The foundation of his family’s culture, language, Country and identity are very strong, whereas with me, I was subject to the assimilation process and I was subject to the Stolen Generation. And my culture, my language, and my identity all got fragmented. I was asking myself, ‘Who am I? Where do I belong? And where do I fit in this world?’. That’s something that everybody asks themselves somewhere along the track, and when you don’t have answers you are burdened with thoughts that you really don’t belong.

First Nations people’s stories have been historically mistold and misrepresented in this country. How did you go about making this beautiful and sensitive documentary in a way that was respectful and true to Dujuan and his family?

WT: It’s a credit to the filmmakers to recognise that this story belongs in the families, and in the people, and at the end of the day they set aside a lot of their professionalism and egos.

As you can see there’s no scriptwriting, this was all done as is, as people lived it. And to do that, it’s an unconventional way of making a documentary. It’s out of the box and it worked because these people were allowed to have agency and ownership in regards to how the film was made, what was in there, and what was not in there. Every step of the way families were totally involved.

Historically, Indigenous films are always about the sensationalising, the romantic image of Aboriginal people in regards to how films are projected, and this one is devoid of any of that image. It turned out to be one of the best films I’ve ever seen in terms of how our people feel about it after. The repercussions of [the filmmakers’] behaviour will allow the film to live for a long time.

And how was this collaborative creative process realised?

MN: We had big workshops with the whole community and also a board of advisors of which William and other people are part of, and then with Dujuan’s family. We had workshops before we even picked up cameras to think about the messaging – what they wanted the film to be about, what they didn’t want the film to be about, and then we watched rushes, edits, we talked about events and how things were going along the way throughout the many years. And those workshops continued through to our impact phase where families were deciding what goals they wanted us to work on as we released the film, which is the stage we are at now.

We really learned from and researched previous projects that came before us, often initiatives led by artists of colour and other First Nations filmmakers who are really leading in the space of collaboration and co-design. We took a lot of that knowledge from the incredible leadership of our First Nations producers, Felicity Hayes, Professor Larissa Behrendt and Rachel Naninaaq Edwardson. Rachel brought her personal and professional expertise as a First Nations Iñupiat woman from Alaska to develop and form the model of consultation that was right for this particular film.

It’s wonderful to be able to direct audiences to learn more about the importance of First Nations-led education. The importance of juvenile justice reform and raising the age of criminal responsibility to at least 14 from 10 which is absolutely ridiculous. And also, more broadly, to try to influence an end to racism in Australia, which is a big goal, but we’re working towards it.

With so many more eyes on the film, what is an important key message or learning you hope people take away from ‘In My Blood It Runs’?

MN: I think that the key message that has been consistent from Dujuan’s family, their takeaway, Megan (Dujuan’s mother) who says, ‘I just want Australians to know that we love and care about our kids’. I think that’s a simple message but a powerful one in the current context of Black Lives Matter and still the ongoing removal of children from their families and the state of human rights abuses in our juvenile justice systems.

Really the message that William has drummed into me for years and years whenever we had a problem of not knowing how to cut a scene or approach a problem that came up, and he would continually say, ‘Remember it’s about the agency of Aboriginal families to have control of their own lives’, and I think we see that in the film because everything that works for Dujuan is a solution that is derived from his family, not from the institutions that are meant to uplift him.

WT: Children’s Ground [the Arrernte-led organisation of which William is the Founding Chair] advocates for system reform in regards to how we educate and look after our children from birth through to the later teen years. Ultimately at the end of the day, we are asking for system reform with regards to how Aboriginal people are treated because the same tired old methods are just not working. Every year it’s a variation of the past. It’s draconian, it’s primitive, it’s really outdated. The powers that be need to rethink what they’re doing.

What we’re doing at Children’s Ground, and as the film depicts, there is another way of being. Give the family agency, let them find a solution, and support them in that solution. And that’s exactly what happened here. Doing the same old things time and time again and expecting different results is the definition of insanity.

In My Blood It Runs is available to stream on ABC iView now, until August 4th, 2020.

Learn more about the people involved with making In My Blood It Runs and follow its journey here .

In My Blood It Runs is not just a film, it’s also a campaign for change. Learn more about how you can support the solutions guided by the Arrernte and Garrwa families here .

Recent Creative People

These Intricate Woven Paintings Explore Creativity Within Contraints

10 Australian Photographers Who Sell Beautiful Prints

Meet Three Emerging First Nations Artists, Whose Work Is Coming To The NGV

Artist Tai Snaith Paints From A Beautiful ‘Haunted’ House In Fitzroy North

A Day In The Life With Landscape Designer Fran Hale Of Peachy Green

This Potter Makes Petal-Edged Bowls To Help Save The Bees

Meet The Metal Maker Behind These Elegant, Handcrafted Lights

11 Of The Best Places To Buy Affordable Art Prints

This Melbourne Artist Creates Beautiful Weavings Inspired By The Past

The Diverse And Experimental Art Practice Of Benjamin Barretto

This Major Exhibition Celebrates Trailblazing Artist Emily Kam Kngwarray

How Designer Cindy Phillips Landed Her Dream Job With Simone Haag

- All Articles

- Latest Issue

Mon, 09/21/2020

'In My Blood It Runs:' Visualizing the Weight of History through an Aboriginal Child's Eyes

By Patricia Thomson

Shooting Scenarios is a new column that takes a single scene and breaks it down cinematographically, looking at the shooting logistics, creative challenges, and camera gear deployed.

Dujuan Hoosan is a precocious 10-year-old from Mparntwe (Alice Springs), Australia, considered a healer by his Arrernte tribe and a delinquent by his colonialist-minded school. For more than two years, Australian documentarian Maya Newell followed Dujuan, capturing both quotidian moments and broader patterns of racism, with special focus on the educational and juvenile detention systems. Working with a mixed indigenous/non-indigenous team, Newell crafted an observational documentary that is neither didactic nor polemical, but makes its points just by sticking close to Dujuan. The film has been shown to the Australian Parliament and the United Nations in Geneva, where Dujuan was the youngest person ever to address the UN’s Human Rights Council.

In My Blood It Runs airs September 21 on POV and is released in the US through Sentient Art Film.

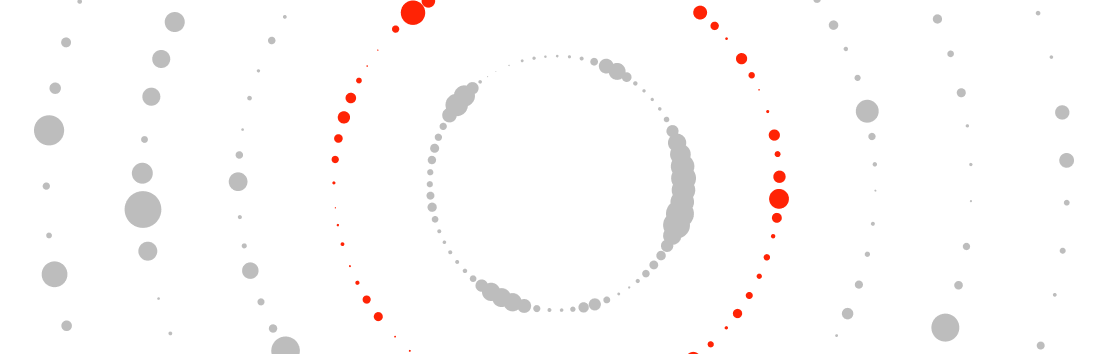

Four minutes into In My Blood It Runs comes a title sequence of such lyricism and evocative meaning it’s clear we’re way beyond the norm.

A close-up camera observes Dujuan playing games with his family and staring into the flames of an oil-drum fire. We then cut to a dreamy, out-of-focus shot of fireworks. Someone has lit a handheld bottle sparkler, which gushes a torrent of golden sparks. Some drift up into the darkness, and the lens’ bokeh turns them into orbs of light floating above a river of gold. The effect is magical.

Dujuan, in focus, fearlessly grabs a lit bottle sparkler from the ground. The image switches to slow motion once he starts to run, trailing sparks like a comet. This takes the film into a different temporal space, one that’s fluid and stretches across the decades. In voiceover Dujuan says, “I was born a little Aboriginal kid. That means I had a memory, a memory about Aboriginals. I just felt something.” Here archival clips start to be intercut with the sparkler footage, each snippet overlaid with dancing orbs of light: an Aboriginal father and children before a smoking fire, dancing men in body paint, Stolen Generation adolescents in uniform at a mission school.

Dujuan continues, “History. In my blood it runs.”

We now see clips of demonstrations leading up to Australia’s 1967 referendum on Aboriginal rights and inclusion in the census. Archival audio fades up: “We want our ceremonies. We want our language. We want our stories told to our children.”

The one-minute sequence ends with a final pop of fireworks and the title In My Blood It Runs .

The Concept

When Newell recorded Dujuan saying that line early on, it stuck with her. “I thought it was incredibly profound for a young person to articulate the weight of history that children carry through life,” says the director/cinematographer. “That doesn’t mean he’s studied the historical facts. But he feels that weight.”

Newell’s challenge was to render that idea visually while remaining true to the film’s child’s-eye perspective. “We asked ourselves, ‘How do we not make this like a BBC documentary, where you’re actually learning that history?’” she recalls.

Rather than use archives didactically, they became “flickers of history,” says the director. The clips selected often contained children and represented Aboriginals’ “resilience and resistance, the history that is not told,” according to Newell. Collectively, they had “the feeling of that weight—as memories, as stories—but telling that in a child-friendly way where it’s not a factual lesson, it’s an evocative portrayal of memory.” The superimposed orbs of light were a reminder that these archival snippets were poetic evocations, a device that continues throughout the film.

“For me, the moments where I’ve been shifted or moved by a documentary are not when I’ve been fed facts,” Newell says. “It’s when I’ve had a feeling, or something’s been presented to me in a new way. So it was really important that we kept the storytelling and the artfulness of this film front and center.”