| | | This drawing was done by a child survivor as part of post-genocide trauma therapy, and appears in . (See the first drawing in this essay for bibliographic information) | Causes of GenocideThe underlying causes of conflicts that result in acts of genocide often have deep historical roots. Stereotypes and prejudices can develop over centuries. Ethnic and cultural distinctions often result in the formation of "in-group" and "out-group" thinking, where members of different races, religions, or cultures view each other as separate, alien, and "different." Identity groups are formed from such thinking. In many regions, members of different identity groups, for mutual advantage, develop conflict prevention methods. Yet where resources are limited, or where pressures are placed on societies because of political or economic instability, relations may degrade. This can lead one group to become convinced that many of its problems are the fault of another group, and that all of those problems would be resolved if only the other group no longer existed. Guy Burgess has named this irrational and potentially dangerous idea the " into-the-sea" frame . Coexistence and power sharing are not considered to be viable options, and the more powerful group instead desires to exterminate the other (i.e., drive the other side "into the sea"). Often there is a "coherent and vicious elite" led by a majority-supported dictator who incites genocidal movements. Such movements find expression more readily when powerful political entities are made up of a common ethnicity and when minorities are marginalized. | "Can I see another's woe, and not be in sorrow too? Can I see another's grief, and not seek for kind relief?" | Responding to Acts of GenocideGenocide, like any morally relevant action, can be supported, denounced, or viewed with apathy. One's moral convictions will result in varying responses to genocidal acts. Perpetrators of genocide often feel completely justified in their actions, and may draw on local cultural or political values to curry favor. This can lead to a response of support, thereby furthering the criminal acts. Others, while not participating in the acts directly, may support them by financial or political means. Still other groups may attempt to take a neutral, apathetic stance. International law and historical precedent, however, has made it extremely dangerous for relevant parties to attempt to merely stand by. An example of such behavior was the Swiss policy of neutrality in World War II.. In the mid-1990s Swiss banks were held accountable for servicing the financial interests of Nazi party members and for failing to settle accounts with Holocaust victims or their surviving family members. It would seem that parties that are in a position to oppose acts of genocide, but fail to do so, can expect punitive repercussions. The international community, following international law , sometimes attempts to stop genocide before it happens, or while it is in process. Often, however, the ability to do anything effective is minimal. Another approach is punishment after-the-fact, which is supposed to not only extract retribution or justice, but also act as a deterrent against future genocidal acts. Whether the deterrence effect is real, however, is unclear. Preventing acts of genocide has become an important topic in peace research. Preventing genocide implies understanding how genocidal motivations begin and how groups become powerful enough to impose their plans on their victims. This involves the ability to recognize how ethnic and political values mesh in potentially dangerous ways and how elite organizers of genocide obtain state power. In addition to developing working theories of how genocidal acts begin and progress, prevention also necessitates the ability to detect signs of genocidal schemes and respond to them as early as possible. Government investigation agencies (such as the FBI and Interpol), the United Nations, and independent human rights organizations (such as Amnesty International), utilize some early detection methods. Attempts to prevent genocide usually involve preventive diplomacy and violence prevention . Dealt with elsewhere in depth, suffice it to say here that this involves both Track I and Track II diplomatic efforts to diffuse tensions and try to encourage the parties to negotiate at least a settlement , if not a resolution of their differences -- enough to prevent widespread violence. Sanctions are also sometimes used as deterrents or punishments for unacceptable behavior. For example, economic, financial and military sanctions were imposed against the Yugoslav Federation to try to end their support of the Serb's "ethnic cleansing," a euphemism for genocide. Military intervention may also be called upon, as was the case with U.N. peacekeeping forces and later NATO forces acting in Bosnia in the 1990s. International law also supports after-the-fact prosecution of war criminals. International law was the force behind the Nuremberg trials of Nazi officers in the late 1940's and, in more modern times, the trial of former Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milosavic at The Hague. The International Criminal Court (ICC), established in 2002, is intended to make such prosecution more effective. Though adherence to the ICC Statute (the Rome Statute) varies from country to country,[5] 139 countries signed the initial statute and the 60-country ratification minimum required for the ICC to enter into force was reached on April 11, 2002. Both the United States and Russia have refused to accept the jurisdiction of the ICC, however, leading to questions about how effective the court can be without their participation. Problems with PunishmentIn actuality, all forms of punishment face difficult challenges. Many question the effectiveness, and the ethicality, of economic sanctions , especially since sanctions can easily affect an entire nation's economy, arguably punishing innocent citizens for the crimes of their government or of a powerful faction. Legal punishment for genocidal acts can be frustrated by an inability to find the individuals responsible. Also complicating the matter is the fact that the number of people who committed the crimes is often so large as to make a trial huge, costly, and impractical. Military action also presents the challenges of how to engage, when to intervene, and how long to stay when hostilities have subsided, in addition to the delay from the time when military action is deemed necessary and when (if at all) it is approved by the international community. Threat of punishment can also prolong a conflict. If one side fears prosecution if they end the conflict, they may continue, even though they realize that they cannot win. One answer to this fear is offering amnesty to all sides, as was done in South Africa with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Here the belief was that reconciliation and stability would be much more easy to achieve if people testified about their heinous actions, but then were forgiven, instead of prosecuted. This, many argue, has allowed that intractable conflict to be transformed much more effectively than it might have been, had whites been threatened with prosecution for crimes against humanity or other violations of international law. The Aftermath of GenocideActs of genocide cause people to flee dangerous areas, becoming refugees or internally displaced people (IDPs). Great numbers of refugees fleeing to neighboring countries can be a social, political, and economic burden on those countries. Refugees often encounter discrimination in new countries, and may have no choice but to live in refugee camps, not knowing when or if they will return home. When they do return, they don't know if they will find their homes and possessions intact. This is but one of myriad problems faced by individuals, communities, and societies after a genocide ends. Once the acts of genocide come under control, and accountability for the crimes is being enforced, the processes of peacebuilding , reconciliation , and healing must begin. Victim groups will, understandably, have a great deal of hatred for their oppressors. Relations between enemy ethnic groups must improve; otherwise retaliatory violence is essentially assured. Efforts to forge new relations between groups and to empower the victim group are justified. Realistically, though, true reconciliation will likely take a long time, as the crimes are horrible enough to make them nearly unforgivable. The greatest challenge following genocide is rebuilding a society, since a conflict that at one time might have been resolved may now have become intractable. The rebuilt society must have a power-sharing form of government in order to prevent future inequalities that could lead to violent retaliation. Preventing a cycle of hatred and violence becomes the central challenge. However, sharing power with one's past enemy, especially following such a horrible crime as genocide, may not be possible. Peace is often tenuous in these situations, as is the case today in Rwanda and Cambodia . [1] Ethnic cleansing is a euphemism for genocide. Ethnic cleansing means "the purging, by mass expulsion or killing, of one ethnic or religious group by another" according to the Oxford English Dictionary "ethnic cleansing" avaliable at http://www.oed.com/ . The term is derived from the Serbian and Croatian etniko ienje and was first used in the 1990s in the former Yugoslavia, especially to describe the actions taken by the Serbian government against ethnic Albanian Muslims living in Kosovo. The Serb government wished to have a Serbia for Serbs and tried to rid its southern region, Kosovo, of non-Serbs. [2] Some moderate Hutus were also victims of mass killings in 1994. [3] United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. [4] Decoust, MichPle. "Australia 's Forgotten Dreamtime." [on-line] ( Le Monde diplomatique , October 2000) Available from http://mondediplo.com/2000/10/14abos . Accessed 28 January 2002. [5] Notably, the United States and China have not ratified the Rome Statute, each having political objections to certain aspects of the treaty. Negotiation efforts between the ICC and countries yet to ratify its power continue. For up-to-date information on such efforts, see http://www.iccnow.org/countryinfo.html Use the following to cite this article: McMorran, Chris and Norman Schultz. "Genocide ." Beyond Intractability . Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: August 2003 < http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/war-crimes-genocide >. Additional ResourcesThe intractable conflict challenge.  Our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious, and the most neglected, problem facing humanity. Solving today's tough problems depends upon finding better ways of dealing with these conflicts. More... Selected Recent BI Posts Including Hyper-Polarization Posts - The Threat of Political Violence in the United States -- The number of people supporting political violence is not nearly the 30% that has been often reported, but it is still much higher than it should be. We all need to try to calm down our rhetoric so things don't get out of hand.

- Revisiting BI's Constructive Conflict Initiative - Part 1 -- Looking back on the 5-year old Constructive Conflict Initiative, a lot has happened to bring it to fruition. But a lot of challenges remain.

- Reprise: The Power Strategy Mix — Empowering the Pursuit of the Common Good -- Power takes three forms that can be mixed and matched: coercion, exchange, and integration. The "recipe" for the optimal "power strategy mix" changes depending on whom you are trying to influence.

Get the Newsletter Check Out Our Quick Start Guide Educators Consider a low-cost BI-based custom text . Constructive Conflict Initiative  Join Us in calling for a dramatic expansion of efforts to limit the destructiveness of intractable conflict. Things You Can Do to Help IdeasPractical things we can all do to limit the destructive conflicts threatening our future. Conflict FrontiersA free, open, online seminar exploring new approaches for addressing difficult and intractable conflicts. Major topic areas include: Scale, Complexity, & Intractability Massively Parallel Peacebuilding Authoritarian Populism Constructive Confrontation Conflict FundamentalsAn look at to the fundamental building blocks of the peace and conflict field covering both “tractable” and intractable conflict. Beyond Intractability / CRInfo Knowledge Base  Home / Browse | Essays | Search | About BI in ContextLinks to thought-provoking articles exploring the larger, societal dimension of intractability. Colleague ActivitiesInformation about interesting conflict and peacebuilding efforts. Disclaimer: All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Beyond Intractability or the Conflict Information Consortium. Beyond Intractability Unless otherwise noted on individual pages, all content is... Copyright © 2003-2022 The Beyond Intractability Project c/o the Conflict Information Consortium All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without prior written permission. Guidelines for Using Beyond Intractability resources. Citing Beyond Intractability resources. Photo Credits for Homepage, Sidebars, and Landing Pages Contact Beyond Intractability Privacy Policy The Beyond Intractability Knowledge Base Project Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess , Co-Directors and Editors c/o Conflict Information Consortium Mailing Address: Beyond Intractability, #1188, 1601 29th St. Suite 1292, Boulder CO 80301, USA Contact Form Powered by Drupal production_1 Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books. Internet Archive Audio - Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet. Mobile Apps- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser ExtensionsArchive-it subscription. - Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page NowCapture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future. Please enter a valid web address - Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Century Of Genocide: Critical Essays And Eyewitness AccountsBookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for. - Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

To help the reader learn about the similarities and differences among the various cases, each case is structured around specific leading questions. In every chapter authors address: Who committed the genocide? How was the genocide committed? Why was the genocide committed? Who were the victims? What were the outstanding historical forces? What was the long-range impact? What were the responses? How do scholars interpret this genocide? How does learning about this genocide contribute to the field of study? While the material in each chapter is based on sterling scholarship and wide-ranging expertise of the authors, eyewitness accounts give voice to the victims. This book is an attempt to provoke the reader into understanding that learning about genocide is important and that we all have a responsibility not to become immune to acts of genocide, especially in the interdependent world in which we live today. plus-circle Add Review comment ReviewsDownload options. For users with print-disabilities IN COLLECTIONSUploaded by Upside Down Clown on September 15, 2022 SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Conflict, Security, and Defence

- East Asia and Pacific

- Energy and Environment

- Global Health and Development

- International History

- International Governance, Law, and Ethics

- International Relations Theory

- Middle East and North Africa

- Political Economy and Economics

- Russia and Eurasia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Special Issues

- Virtual Issues

- Reading Lists

- Archive Collections

- Book Reviews

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About International Affairs

- About Chatham House

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article ContentsGenocide: the power and problems of a concept- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Cecilia Ducci, Genocide: the power and problems of a concept, International Affairs , Volume 98, Issue 5, September 2022, Pages 1786–1787, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiac170 - Permissions Icon Permissions

Andrea Graziosi and Frank Sysyn's Genocide: the power and problems of a concept explores the inherent tensions surrounding the definition of this crime and makes a significant contribution to the study of genocide. As the introduction points out, genocide presents an intrinsic ‘friction between a legal and thus basically rigid concept, and the multifaceted realities explored by research in fields such as history, anthropology, law, area studies, gender studies, and the history of ideas’ (p. 3). The book aims to ‘contribute to a more nuanced understanding’ of genocide and shed light on the challenges and inner contradictions of this crime (p. 3). To do so, the contributors review the history of genocide in the twentieth century with a variety of chapters that may be of interest to a broad audience studying genocide, history, sociology and International Relations (IR). In the first chapter, Anton Weiss-Wendt critically assesses the drafting of the Genocide Convention. Highlighting the competing interests of great powers, Weiss-Wendt argues that ‘it was meant to be a dead letter’ (p. 23). Annette F. Timm then denounces the exclusion of sexual violence from commemorations and education regarding genocide, in particular the Holocaust, as a form of silencing. Ronald Grigor Suny's chapter stands out as he criticizes the widespread trend of condensing all types of mass violence into the category of genocide. Instead, he proposes the categorization of violence into ‘exemplary’, ‘excisionary or exterminationist’ and ‘residual’, arguing that ‘genocide and genocidal are distinct’ ideas (p. 89). Norman M. Naimark's and Graziosi's chapters are somewhat complementary with their shared focus on Soviet famines of the 1930s, such as the Holodomor in Ukraine. This way, the book sheds light on the use of starvation as a tool of genocide. In a similar vein, Douglas Irvin-Erickson references Raphael Lemkin's 1953 speech about the Ukrainian genocide (pp. 145–6). Despite calling the Genocide Convention ‘a product of post-World War II geopolitics’, Irvin-Erickson actually warns against broadening the scope of genocide to avoid watering down its meaning under international law (p. 149). Caroline Fournet analyses the problems of genocide from another perspective, focusing on the French reluctance to apply the Genocide Convention, while Michelle Tusan describes genocide as a process which should account for the ‘experience beyond the moment of atrocity’ (p. 216). Finally, Scott Straus ends the book with a thought-provoking point about the one-sided framing of the Rwanda case, claiming that public attention has neglected to consider the non-genocidal crimes that were committed before, during and after the Rwandan genocide. By exploring other types of violence in the Rwandan context, Straus ultimately contends that, given its status, the exclusive focus on genocide can divert public attention from other forms of mass violence (p. 245). Given the wide array of scholars that contributed to the volume, the book builds on what seems to be an inner contradiction. On the one hand, it calls for the extension of the category of genocide to accommodate the ever-changing and diverse realities of violence. On the other hand, it highlights how the emphasis on genocide reinforces the perception that other forms of non-genocidal violence (that do not reach the threshold of genocide) are perceived as ‘less worthy of sustained attention’ (p. 240). It is therefore unclear where the book stands on this issue: should the definition be broadened to encompass cases that are not legally and historically considered full-fledged genocides? Or should the problem be countered by stressing the existence and relevance of other mass atrocities, such as crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing and war crimes? The book accurately illustrates how the geopolitical interests that led to the current definition of genocide have inevitably raised the well-known debates over whether we should stick to a narrow conceptualization or adopt a broader understanding of this crime. On this note, it would have been worth emphasizing that these discussions fundamentally stem from the superior status attributed to genocide, which has been acquired over time from both a legal and a socio-historical perspective. A brief overview of the jurisprudence on genocide in the first few chapters could have stressed this point. To conclude, the book makes a valuable contribution to the current understanding of genocide and its numerous contradictions. It provides empirical examples of the discussions regarding its definition over the years and goes a step further by bringing to the fore the oft-neglected concept of ‘transformative genocides’ (p. 7). The contributors also usefully unpack the motivations and the narratives that sustain this phenomenon. The book deals with the limitations of the concept of genocide from different perspectives and through several case-studies in a skilful way. Overall, it has significant implications for further studies on the politicization of genocide. | Month: | Total Views: | | September 2022 | 199 | | October 2022 | 167 | | November 2022 | 115 | | December 2022 | 106 | | January 2023 | 35 | | February 2023 | 22 | | March 2023 | 29 | | April 2023 | 53 | | May 2023 | 32 | | June 2023 | 25 | | July 2023 | 24 | | August 2023 | 18 | | September 2023 | 24 | | October 2023 | 25 | | November 2023 | 29 | | December 2023 | 33 | | January 2024 | 30 | | February 2024 | 24 | | March 2024 | 28 | | April 2024 | 19 | | May 2024 | 37 | | June 2024 | 37 | | July 2024 | 27 | | August 2024 | 33 | | September 2024 | 16 | Email alertsCiting articles via. - Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations- Online ISSN 1468-2346

- Print ISSN 0020-5850

- Copyright © 2024 The Royal Institute of International Affairs

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide - Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers OnlySign In or Create an Account This PDF is available to Subscribers Only For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription. Genocide - Essay Examples And Topic Ideas For FreeGenocide is a term used to describe violent crimes committed against groups with the intent to destroy the existence of the group. Essays on genocide can discuss historical instances, the psychological and social underpinnings of genocidal acts, and the global response to genocide. This could include an examination of international laws, the role of the International Criminal Court, and various humanitarian interventions aimed at preventing or responding to genocide. A substantial compilation of free essay instances related to Genocide you can find in Papersowl database. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself. Outlook on the Cambodian GenocideThe Cambodian Genocide was a slaughter of Cambodians by the Khmer Rouge who was led by Pol Pot, from 1975-1979. Pol Pot who was the Prime minister of Cambodia at the time killed Cambodians by execution, forced labor, and famine. Pol Pot renamed the country Democratic Kampuchea. The reign was ended after 4 years when Vietnam invaded and caused the collapse of the regime. The Cambodian Genocide was the result of a social engineering project by the Khmer Rouge, attempting […] The Armenian GenocideThe start of the Armenian genocide occurred in the year 1913 and extended all the way through 1916 which involved the Turks and Armenian people taking place in the Ottoman Empire. Throughout history, attempts to gain control over land has been a major cause of destruction and mass targeting of groups of people in the efforts to retain powerful empires and kingdoms throughout history. The loss of the Ottoman Empire's land to the west brought the leaders of the Turkish […] Critical Race Theory: Guiding the Path of Black Lives Matter"Critical race theory is a study on of racial oppression and its direct connection to the law and the government. Critical race theorists believe that the law largely contributes to racial oppression and works to keep white supremacy active. They study the ways that the law does this currently and throughout history. Black Lives Matter uses many of the ideas of critical race theory in looking at issues within the systems of our society. Attempting to recreate and change the […] We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs. History of the Rwandan GenocideThe Rwandan Genocide was a tragic event that happened in April 1994 to July 1994. The genocide took place in the Rwandan Civil War, a conflict beginning in 1990 between the Hutu and the Tutsis people. The genocide made many problems for the world, it has many lasting effects on the world and Rwanda. The Rwandan genocide was as devastating as the Holocaust and were both left with a bad reputation. “After the genocide, Rwanda was on the brink of […] Genocide: the Nazis’ Original PlanThe Holocaust, which took place during 1933-1945, was a devastating period of time when the German Nazi's planned to mass murder European Jews. The literal term 'Holocaust' originates from the Hebrew Bible's term olah meaning a sacrifice that is offered up. This was a frightening time for everyone, Jewish and non-Jewish. Approximately six million people were killed as a result of the Holocaust (Roth). Adolf Hitler, the leader of Germany at the time, hated Jews and blamed them for all […] Why did the Holocaust Happen?Today, the problem of studying the Holocaust is the problem of the recognition of its uniqueness as a historical phenomenon of a universal scale. Before World War II, all conflicts in the history of genocide were based on religious conflicts: mass extermination of people took place on religious grounds. In the twentieth century, religious motives ceased to play a decisive role in determining the group identity of people. The Holocaust was one of the acts of mass destruction of people […] Genocide in Germany the HolocaustGenocide is by definition the intentional, methodical, and targeted destruction of a particular ethnic, religious, or racial group. The term genocide is derived from the Greek prefix genos, which translates to race or tribe, and the Latin suffix cide, meaning killing. The Holocaust, also known as Shoah, is the most notable and deadliest instance of genocide in the world. The Holocaust began in Germany in the 1930s and expanded to Nazi occupied Germany, until the last liberation of death camps […] How could Rwandan Genocide be Justified?The Rwandan genocide occured in 1994 in Kigali, Rwanda. After the germans lost possession of Rwanda, the people of Rwanda were placed under the Belgian administration. The fight between the two ethnic groups, Hutu and Tutsi, had been brewing for years but with the death of their king and president the Hutus saw a chance to move higher up in the social status. For years, the Hutus and Tutsis were treated as two different races instead of the same. This […] Deliberate and Systematic Destruction of a Racial, Political, or Cultural GroupThis genocide that is going to be discussed was state-sponsored and became known as one of the world's most notorious times to be alive. The official definition of a holocaust is a thorough destruction involving extensive loss of life (Merriam-Webster, Holocaust ). When it pertains to the Holocaust, almost everyone knows what it is. It was the mass killing of almost six million Jewish, Slavic, and mentally disabled people by Nazi Germany during World War II. Nazis had the hope […] The Greek Genocide HistoryThe genocide I'm revolving my term paper around is the Greek Genocide. The Greek Genocide started during and after World War I from 1914 to 1923. More specifically, the Ottoman Empire were the central antagonists that perpetuated this systematic extermination of millions of innocent Greek lives. Amongst the lofty death toll, other unfortunate consequences of this genocide included but were not limited to: deportation by force, agonizing death marches, rape, and imposing religion on to the Greeks. The Greek Genocide […] Phenomenon of GenocideBetween 1975 and 1979, during the Vietnam War, the United States bombarded a great deal of the nation of Cambodia and manipulated Cambodian politics to support the increase of Lon Nol as the leader of Cambodia. A Communist group known as Khmer Rouge used this as an opportunity to recruit followers as an excuse for the brutal policies, they exercised once in power. The Khmer Rouge took control of the Cambodian government in 1975, with the objective of transforming the […] Human Rights are Basic Rights Given to a Person Mainly because they are Humans Human rights are held universally by all humans, and no distinction should be made as to who can exercise and obtain their rights. Benjamin Valention (2000) ponders why some conflicts result in the killing of massive numbers of unarmed civilians. This remains one of the most discussed topics facing humanity. He further states that as the threat of global nuclear conflict recedes in the wake of the cold war, mass killings seem poised to regain their place as the greatest […] The Holocaust’s Bureaucracy of GenocideThe intent of this study was to select and analyze a global event. The event chosen to be analyzed was the Holocaust. The Holocaust occurred in Germany beginning in the 1930s and then expanded to all areas of Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. The event was a genocide in which Nazi Germany murdered about six million European Jews; they also murdered other groups, which resulted in up to seventeen million deaths overall. Germany's persecution of these groups was implemented […] Horror of GenocideThroughout history, man has always been at battle with one another, even today. When remembering the different historical events that occurred back then, the main things that come to the mind are war and hatred. Over the years different groups of people and government have had the trait of hatred and have used it to go through with eliminating their "enemies" with war. War has a certain standard, this standard allows people to fight when legitimate conflicts arise and can't […] Genocide in Germany: the HolocaustThere is much speculation as to why Adolf Hitler may have hated Jewish people so fervently. Some historians suspect that it could be related to his heritage; Hitler's father Alois was born out of wedlock, and there were rumors that he might have been of Jewish descent. Adolf did not have a healthy relationship with his father, leading some to believe that this is a possible explanation for his contempt. Another possible case for Hitler's disgust for Jewish people could […] Native American GenocideWhen digging deeper into American history and learning about what happened to Native American Indian populations brings extremely dark and unpleasant facts surrounding America's foundation to the surface. These facts are often used to help undermine the commonly held belief that America is a great nation founded on moral principles of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is undeniable that Europeans committed many atrocities against the American Indians. This has led some to raise questions of genocide and […] The Theme of the Holocaust and the ResponsibilityWhen we see an image in black and white, we tend to believe that such an event only occurred in a history textbook years ago. We think of wars, death, power, the absence of life, and aggression. An image in black and white can create a nostalgic mood or a hopeless feeling like the Holocaust picture presented below. The image background, a grassland, looks dead and dull, no life being born out of it and a gray sky portraying an […] American Genocide Issues"By 1923, a 3,000-year-old civilization virtually ceased to exist," (Cohan). This civilization is Armenia, once a nation under the rule of the formidable Ottoman Empire, a powerful Islamic dynasty that controlled extensive territories throughout Southeast Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa. As citizens of the Ottoman Empire, the Armenian people were challenged for their firm Christian identity by its Turkish rulers through discriminatory laws and taxes. With the Empire facing territorial decline and a severe collapse of power amidst Armenian […] Problem of Genocide in AmericaIn America there has been Genocide. Even abroad there has been genocide. Genocide is classified as the "deliberate and systematic destruction of a racial, political, or cultural group". Genocide is intentional killing of people based on their race, gender, and many other entities. Many classify the biggest genocide in history was the killing of Germans during the Holocaust. Also, the intentional killing of Black Americans, during the slave trade and slavery. Even today with the intentional oppression of Black Americans […] Darfur and the Labeling of GenocideThe situation in Darfur is a result of multiple conflicts that started as separate, but eventually came to intersect. One of these conflicts is a civil war between the Islamist Khartoum-based government and the Sudanese Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality Movement. Khartoum is the capital and largest city in Sudan. The two rebel groups opposed the political and economic marginalization of Darfur by the Khartoum. The groups made their appearance in February 2003, but the government did not […] The Genocide of the Pontic GreeksThe Pontic Greeks were set in Ottoman Empire in the midst of the Armenian Genocide. It was the Spring of 1914. The Turks began ordering Greeks from Eastern Thrace as well as Western Anatolia to boycott every business run by a Greek. In the midst of this, hundreds of thousands Greek inhabitants from those regions were deported. Every Ottoman Greek man with an age between 21 and 45 were sent to concentration camps. These men endured pain-staking labor lacking any […] Why should we Never Forget the HolocaustI think that it is important to learn about the holocaust and what had happened during it. From the beginning of the holocaust when it all started, 1933, when hitler became power over germany, none of it was right or acceptable. Learning about the holocaust is something that everyone in the world should know about. Knowing what happened should be enough to make sure that this action never takes place again because of how brutal and harsh it was. Humans […] US Backed a GenocideThis research paper focuses on The United States lack of political action against human rights violations against the Argentina citizens by the military dictatorship and General Jorge Rafael Videla. The fact the United States knew about the human right violations, had a team conduct investigation in to the matters and supported the military dictatorships. Creates a moral and ethical question here as to how the US justified their support of the military dictatorship and the Foreign Policy that played into […] The Root of the Holocaust: DarfurUpon different generations we have seen numerous genocides occur in all areas around the world. One of the most famous genocides was the Holocaust. Though the Holocaust was made aware to the public and caught the eye of people all over the globe, it still fell through the cracks for many years just like a lot of other genocides. Most of the time, genocides are started in silence because the people who are being targeted are kept quiet such as […] Gender and Sexuality: a Historiography and Analysis of the HolocaustThe Holocaust: a genocide in which Nazi Germany, aided by local collaborators, systematically murdered millions of people between 1941 and 1945; an event made possible through meticulous planning and manipulation across multiple dimensions. In an attempt for ultimate control, Hitler preyed upon the vulnerabilities of pre-existing stereotypes and stigmas surrounding gender and sexuality and manipulated his followers in accepting these ideologies. In fact, is arguable that everyone involved within the Holocaust (men, women, children, homosexuals, Jews, those of minority ethnicity, […] Elie Wiesel’s “Night”: Unveiling Humanity in Echoes in DarknessElie Wiesel's "Night" is more than just a memoir; it's a haunting exploration of the depths and extremes of human nature, confronted by unimaginable horror. Published in 1956, this poignant narrative charts Wiesel's personal journey through the Holocaust as a teenage Jew. But beyond its historical context, "Night" stands as a timeless testament to the human spirit's resilience and the persistent struggle between hope and despair. "Night" starts in the small town of Sighet, where Wiesel lived a relatively peaceful […] United States of IslamophobiaSophie Mize, March 7th, 2019 - Honors English IV, 4th Period: American Islamophobia and Genocide. Hatred is a learned behavior and, more than a behavior, it is used as a tool in times of turmoil. Historically, this hatred leads to divisions in society and an inevitable widespread violence. The method of dispersion and implantation of ideals varies, from the identification system and propaganda slander of the Tutsi by the Hutus, to the current brainwashing against those who fail to acknowledge […]  Understanding the Concept and Implications of the “Final Solution”The term "Final Solution" is deeply ingrained in the historical lexicon of the 20th century, primarily referring to the Nazi regime's plan for the systematic genocide of the Jewish population during World War II. This phrase, first articulated in the early 1940s, was a euphemism for the most heinous crimes against humanity, resulting in the deaths of approximately six million Jews, along with millions of others deemed undesirable by the Nazi state. Understanding the implications and context of the "Final […] Adolf Hitler’s Role in the Holocaust: a Historical AnalysisOne of the most terrible incidents in human history is the part played by Adolf Hitler in the Holocaust. Six million Jews and millions of others were killed in this systematic state-sponsored persecution that serves as a sobering warning about the perils of totalitarian governments and unbridled hatred. The massive Nazi apparatus under Hitler's leadership his strategic choices and his ideological convictions all played significant roles in the planning of this massacre. Adolf Hitler who was born in Austria in […] When did the Holocaust End? Examining the Conclusion of a Dark Era and its Lasting Impact on World HistoryThe Holocaust stands as a profound testament to both the darkest capabilities of human nature and the extraordinary resilience inherent in the human spirit. As World War II neared its end, the relentless machinery of the Nazi genocide continued unabated, despite the shifting tides of battle. The encroachment of Allied forces into Nazi-occupied lands brought with it a sliver of hope in a period overshadowed by immense darkness. The liberation of the concentration camps underscored the resilience of the human […] Related topicAdditional example essays. - Discrimination in Workplace

- Should Teachers Carry Guns

- What A Streetcar Named Desire lost in the film

- What is the Importance of Professionalism?

- Solutions to Gun Violence

- Catherine Roerva: A Complex Figure in the Narrative of Child Abuse

- Followership and Servant Leadership

- Why Abortion Should be Illegal

- Death Penalty Should be Abolished

- The Mental Health Stigma

- Logical Fallacies in Letter From Birmingham Jail

- How the Roles of Women and Men Were Portrayed in "A Doll's House"

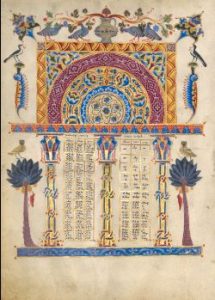

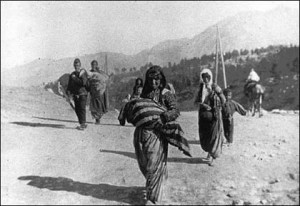

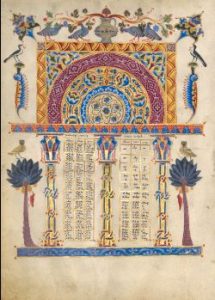

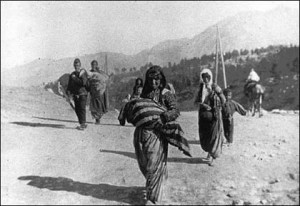

1. Tell Us Your Requirements 2. Pick your perfect writer 3. Get Your Paper and Pay Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant! Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert. short deadlines 100% Plagiarism-Free Certified writers  Teaching GuidesNew resistance, agency, and empowerment.  The Resistance, Agency, and Empowerment teaching unit explores the concept, forms, and examples of resistance through which students learn about genocide. Examining individual and collective actions in response to the Armenian Genocide and its denial as it was being carried out and over the course of more than a century thereafter, the unit highlights the long, continuing legacy of genocide and the value of individual choice and cooperation in affecting positive change. (more…) NEW! Armenian Life in the Ottoman Empire Before 1915 Life under the Ottoman Empire had its own unique challenges and opportunities for Armenians, as is evident through this collection of pictures, courtesy of the Project Save Armenian Photo Archives, Inc. This lesson focuses on analyzing primary sources (more…) New! “Bird Letters” Lesson & Activity Understanding other cultures means exploring their languages, beliefs, art, traditions. Central to the Armenian identity is the unique language and alphabet, a deeply held religious faith, and their unique expression of these two components in “illuminated manuscripts” (handwritten books decorated with elaborate designs or miniature pictures.) These ancient texts are still revered by Armenians… (more…) Stages of Genocide: A Toolkit for Educators Studying genocide is a critical part of a student’s understanding of both history and of current events. The Stages of Genocide Toolkit is designed to help teachers cover the topic in a meaningful and incisive way, introducing students to the phenomenon of genocide itself and then examining it through multiple case studies. (more…) Operation Nemesis: Using a murder trial to teach about the Armenian Genocide Soghomon Tehlirian, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, assassinated Talaat Pasha, the primary architect of the Armenian Genocide, in Berlin in 1921. Although there was no doubt Tehlirian committed the murder, the jury found him not guilty, after hearing 2 days of testimony about the genocide planned and executed by Talaat Pasha. The trial helped motivate Raphael Lemkin to coin the word “genocide.” (more…) Survivor Objects: the Zeytun Gospels The Zeytun Gospels, an 800-year-old manuscript, survived the Armenian Genocide. Understanding the life of an object like the Zeytun Gospels illuminates the devastation of genocide. It also shows how justice, even in small doses, can be found amidst the ruins left by genocide. (more…) Human Rights and Genocide: A Case Study of the First Modern Genocide of the 20th Century This comprehensive teacher’s manual focuses on the Armenian Genocide of 1915 during which 1.5 million Armenians, half of the Armenian population, were systematically annihilated. It includes a 1-day, 2-day, and 10-day unit with all the materials teachers will need, including more than two dozen overheads, interactive classroom exercises and more. Discussions include a wide range of topics related to the Armenian Genocide: the history of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, primary source documents, witness and survivor memoirs, maps and political-economic timelines, and the problem of denial. (more…) Two Day Lesson on the Armenian Genocide This is a compressed version of The Genocide Education Project’s ten-day curriculum found in Human Rights and Genocide: A Case Study of the First Modern Genocide of the 20th Century . It is to be completed in two fifty-minute class periods, with 2 homework assignments, one before and another between the lessons. The lesson includes the definition of genocide, historical background on the Armenian case, a review of other major genocides, a short national TV news piece, and readings from survivor testimonies. Finding a New Life: The Armenians of Watertown Finding a New Life: The Armenians of Watertown is an introductory unit providing a background to the history of the Armenian Genocide, the effects of the genocide on subsequent generations in Watertown, and universalizes the experience for other groups who have found safe haven in Watertown. Finding a New Life illustrates the continued pain and damage that genocide brings and the fortitude of those searching for the truth. Deli Sarkis: The Scars He Carried This lesson plan is accompanies readings from the book Deli Sarkis: The Scars He Carried by Ellen Sarkisian Chesnut. The lesson was created by Frank Perez, World History teacher at San Benito High School in Hollister, CA. (more…) THE PROMISE lesson plan: Concepts of Resistance “Our revenge will be to survive,” says the character Ana to Michael in the feature film, The Promise . This lesson introduces students to the efforts by genocide victim populations to respond to the violence against them. Using the feature film, The Promise , students are guided through readings, discussions, and exercises about the Armenian Genocide and the different forms resistance can take. The Other Side of Home GenEd has created a discussion guide to accompany this compelling 40-minute documentary which explores a Turkish woman’s discovery of her hidden Armenian heritage and the legacy of genocide denial. “The Other Side of Home” is now available to view through public library online streaming services, Kanopy, Hoopla, and Overdrive, using your public library card number (If you don’t have a card, many libraries now accept online library card applications.) THE PROMISE: film study guide The film, The Promise, released in 2017, is the first major Hollywood dramatic feature recounting the history of the Armenian Genocide of 1915, perpetrated by the Turkish government. The film provides a unique educational opportunity to understand the greatest atrocity and human rights crisis of WWI. It also opens a window onto the German and American presence in the (more…) Memorializing Genocide: A Tulip Garden How should genocide be remembered? This lesson and activity begins with a classroom discussion about how communities remember major historical events, including human rights atrocities. Students also learn the allegorical story of Armenian botanist JJ Manissadjian, who studied and catalogued a rare, wild tulip found in the Armenian homeland in pre-WWI Ottoman Empire. The tulip became extinct in the wild, but was cultivated later from seeds Manissadjian had sent to Europe. Manissadjian was imprisoned during the Armenian Genocide, but escaped and immigrated to Europe and the United States. The tulip story is symbolic of the fate of Armenians. Ten Stages of Genocide This teaching guide is based on genocide scholar Dr. Gregory H. Stanton’s work “Ten Stages of Genocide” (an update of his previous “Eight Stages of Genocide,” 1996.) The progression of stages is a formula for how genocide is prepared, carried out, and produces long-lasting repercussions. Beginning with prejudice, genocide develops over time, involving the cooperation of a large number of people and the state; This lesson helps students understand genocide as a process that can be corrected and prevented. Educator’s Guide for “Like Water for Stone” Novel Like Water on Stone by Dana Walrath is fictional account of the Armenian genocide. This novel in verse recounts the flight to America of three Armenian children after the Ottoman Turks confiscate their family’s flour mill and murder their parents. For sixty-three days the children travel on foot, above the tree line of the Caucasus Mountains and through the Syrian Desert, to reach refuge in Aleppo, Syria. Taken in by a sympathetic Arab shopkeeper, the children disguise themselves as Arabs to avoid being forcibly relocated to the Deir el-Zor concentration camp, where starvation and barbarity led to certain death. After three years in hiding, the children finally receive a letter and boat tickets to America from their keri (maternal uncle). The book’s Educator’s Guide was created for Random House by Judith Turner, a longtime educator at Terrace Community Middle School in Tampa, Florida. It includes pre-reading activities, discussion and activity prompts and a list of Common Core Standards correlations. They Shall Not Perish: The Story of Near East Relief They Shall Not Perish: The Story of Near East Relief is a 32-page curriculum booklet on America’s response to the Armenian Genocide, through the work of the Near East Relief foundation. NER workers courageously bore witness to the genocide and fed, clothed, and provided medical treatment to thousands of refugees. Near East Relief is credited with saving over one million lives between 1915 and 1930, including 132,000 orphan children, in what was the largest international humanitarian effort up until that time. An Armenian Journey: From Despair to Hope in Rhode Island A curriculum resource guide and video documentary created by The Genocide Education Project in cooperation with the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities. The Armenian Journey: From Despair to Hope in Rhode Island provides a background to the history of the Armenian Genocide, the effects of the Genocide on subsequent generations, and universalizes the experience for other groups who have found safe haven in the United States. The video and resource guide illustrates and elucidates the continued pain that the enormous crime of genocide and its denial brings, as well as the fortitude of those searching for truth. (more…) The New York Times and the Armenian Genocide A Lesson Plan based on The Armenian Genocide – News Accounts from the American Press, 1915-1922This curriculum extracts articles from the book, “The Armenian Genocide: News Accounts from the American Press,” compiled by Richard Kloian (available from GenEd and can be ordered for $25 by emailing). Including 200 New York Times articles, other journalistic accounts, U.S. Ambassador Morgenthau’s personal account of the genocide, survivor accounts, telegrams from the genocide perpetrator, photographs, and more, the book presents a compelling chronicle of the systematic deportations and massacres of the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire, perpetrated by the Turkish governing authorities between 1915 and 1922. iwitness Photo Activity The i w itness photo documentary project was begun by artists Ara Oshagan and Levon Parian in 1995, when they began photographing and later interviewing survivors of the Armenian Genocide. The photographs were first exhibited at the Downey Museum of Art in southern California in 1999, and later featured in the LA Times Sunday Magazine and many other venues. During the centennial commemoration of the Armenian Genocide in 2015, the exhibit was re-made into a large-scale public art installation on three levels at the Music Center and Grand Park in Downtown Los Angeles. i witness provides an ideal vehicle for middle-high school students to explore first-person testimonies of the Armenian Genocide through an artistic, interpretive lens.  Exhibit installation images by Ara Oshagan, Levon Parian, Vahagn Thomassian, Narineh Mirzaeian | www.iwitness1915.org Genocide and the Human Voice: Nicole’s Journey This interactive online classroom provides students a background to the history of the Armenian Genocide and the effects of the denial of the Genocide on subsequent generations. Nicole’s real life journey to the village of her grandmother, now in Eastern Turkey, illustrates the continued pain that genocide brings and the fortitude of those searching for truth. (more…) Crimes Against Humanity and Civilization: The Genocide of the Armenians FROM FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES: Facing History’s resource book, Crimes Against Humanity and Civilization: The Genocide of the Armenians, combines the latest scholarship on the Armenian Genocide with an interdisciplinary approach to history, enabling students and teachers to make the essential connections between history and their own lives. By concentrating on the choices that individuals, groups, and nations made before, during, and after the genocide, readers have the opportunity to consider the dilemmas faced by the international community in the face of massive human rights violations. (more…) The Armenians: Shadows of a Forgotten Genocide Published by the Holocaust Resource Center and Archives, Bayside, New York for its 1999 Armenian Genocide exhibit, this 23-page booklet includes a brief history on the Armenian Genocide, news coverage, maps, the continuing Turkish government denial, and discussion questions. Contact The Genocide Education Project for the booklet. The Armenian Genocide, 1915 – 1923: A Handbook for Students and Teachers Prepared by the Armenian Cultural Foundation About the Author: Simon Payaslian holds a Ph.D. In political science (Wayne State University, 1992) and is a Teaching Fellow and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). This handbook provides both a historical perspective of the Genocide and an overview of international and national constraints in preventing the genocides that followed, highlighting the world’s inability to deal appropriately with the perpetrators of the Armenian Tragedy. This book also provides teachers with maps, graphs, and eyewitness accounts as well as valuable teaching aids such as the worksheets, discussion and essay topics to maximize the student’s understanding of how the unspeakable can occur and recur even in contemporary times. Model Curriculum For Human Rights and Genocide Published for the California State Board of Education by the California Department of Education ISBN 0-8011-0725-3 This Model Curriculum for Human Rights and Genocide, which serves as a guide for classroom teachers, supports the curriculum and instruction described in the framework. Pages 1-5 of this document contain a model that can be used by developers of curriculum. This section provides the philosophical bases for including studies on human rights and genocide in the curriculum, identifies places in the history-social science courses where learnings can be included, and poses questions that will engage students in critical thinking on this topic. (more…) Teaching the Armenian Genocide: Resources for Teachers, Students and Educators Published by the Armenian Genocide Resource Center (AGRC) of Northern California This resource guide lists books, teaching guides, research reports, monographs, archival documents, bibliographies, photographs, websites, videos, and maps available on the Armenian Genocide. Confronting Genocide: Never Again?FROM THE CHOICES PROGRAM: Overview of the Unit – The genocides of the twentieth century elicited feelings of horror and revulsion throughout the world. Yet both the international community and the United States have struggled to respond to this recurring problem. (more…) - Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contentsGenocide and american indian history. - Jeffrey Ostler Jeffrey Ostler Department of History, University of Oregon

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.3

- Published online: 02 March 2015

The issue of genocide and American Indian history has been contentious. Many writers see the massive depopulation of the indigenous population of the Americas after 1492 as a clear-cut case of the genocide. Other writers, however, contend that European and U.S. actions toward Indians were deplorable but were rarely if ever genocidal. To a significant extent, disagreements about the pervasiveness of genocide in the history of the post-Columbian Western Hemisphere, in general, and U.S. history, in particular, pivot on definitions of genocide. Conservative definitions emphasize intentional actions and policies of governments that result in very large population losses, usually from direct killing. More liberal definitions call for less stringent criteria for intent, focusing more on outcomes. They do not necessarily require direct sanction by state authorities; rather, they identify societal forces and actors. They also allow for several intersecting forces of destruction, including dispossession and disease. Because debates about genocide easily devolve into quarrels about definitions, an open-ended approach to the question of genocide that explores several phases and events provides the possibility of moving beyond the present stalemate. However one resolves the question of genocide in American Indian history, it is important to recognize that European and U.S. settler colonial projects unleashed massively destructive forces on Native peoples and communities. These include violence resulting directly from settler expansion, intertribal violence (frequently aggravated by colonial intrusions), enslavement, disease, alcohol, loss of land and resources, forced removals, and assaults on tribal religion, culture, and language. The configuration and impact of these forces varied considerably in different times and places according to the goals of particular colonial projects and the capacities of colonial societies and institutions to pursue them. The capacity of Native people and communities to directly resist, blunt, or evade colonial invasions proved equally important. - Native Americans

- American Indians

- colonialism

- imperialism

- Indian removal

- ethnic cleansing

- Indian reservations

- assimilation