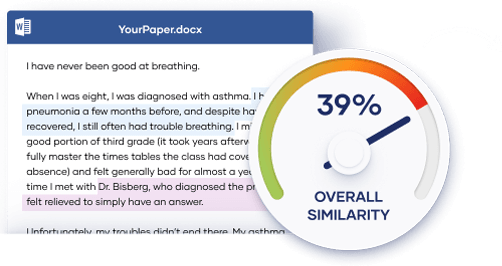

Prevent plagiarism, run a free plagiarism check.

- Knowledge Base

Academic Integrity vs. Academic Dishonesty

Published on March 10, 2022 by Tegan George and Jack Caulfield. Revised on April 13, 2023.

Academic integrity is the value of being honest, ethical, and thorough in your academic work. It allows readers to trust that you aren’t misrepresenting your findings or taking credit for the work of others.

Academic dishonesty (or academic misconduct) refers to actions that undermine academic integrity. It typically refers to some form of plagiarism , ranging from serious offenses like purchasing a pre-written essay to milder ones like accidental citation errors. Most of which are easy to detect with a plagiarism checker .

These concepts are also essential in the world of professional academic research and publishing. In this context, accusations of misconduct can have serious legal and reputational consequences.

Table of contents

Types of academic dishonesty, why does academic integrity matter, examples of academic dishonesty, frequently asked questions about plagiarism.

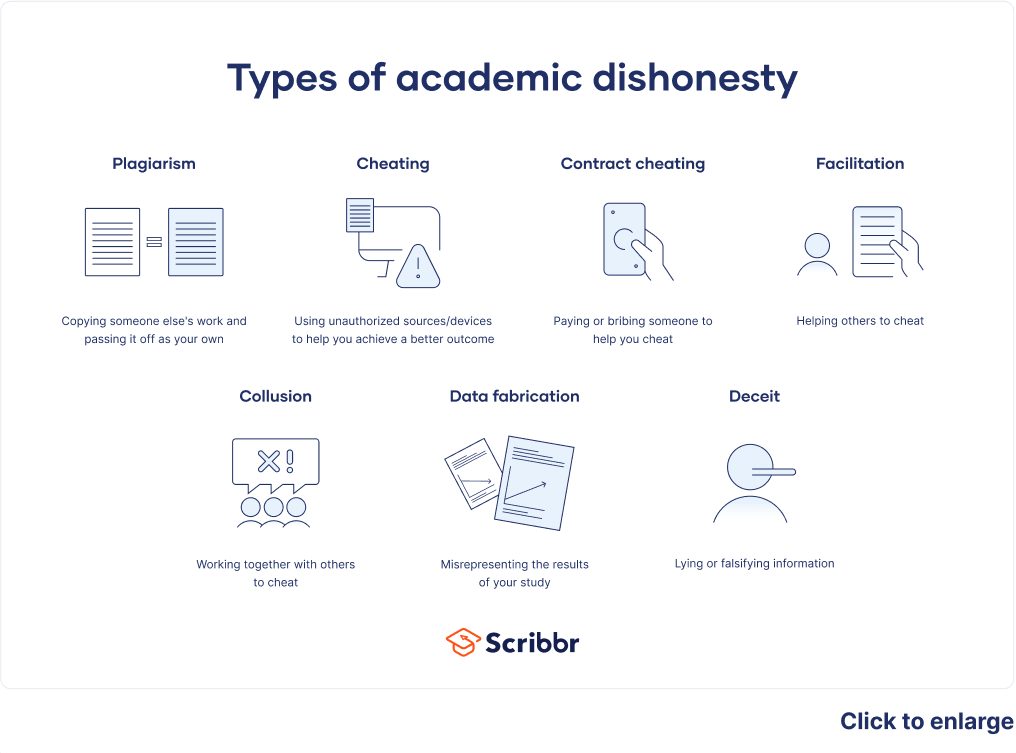

While plagiarism is the main offense you’ll hear about, academic dishonesty comes in many forms that vary extensively in severity, from faking an illness to buying an essay.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Most students are clear that academic integrity is important, but dishonesty is still common.

There are various reasons you might be tempted to resort to academic dishonesty: pressure to achieve, time management struggles, or difficulty with a course. But academic dishonesty hurts you, your peers, and the learning process. It’s:

- Unfair to the plagiarized author

- Unfair to other students who did not cheat

- Damaging to your own learning

- Harmful if published research contains misleading information

- Dangerous if you don’t properly learn the fundamentals in some contexts (e.g., lab work)

The consequences depend on the severity of the offense and your institution’s policies. They can range from a warning for a first offense to a failing grade in a course to expulsion from your university.

- Faking illness to skip a class

- Asking for a classmate’s notes from a special review session held by your professor that you did not attend

- Crowdsourcing or collaborating with others on a homework assignment

- Citing a source you didn’t actually read in a paper

- Cheating on a pop quiz

- Peeking at your notes on a take-home exam that was supposed to be closed-book

- Resubmitting a paper that you had already submitted for a different course (self-plagiarism)

- Forging a doctor’s note to get an extension on an assignment

- Fabricating experimental results or data to prove your hypothesis in a lab environment

- Buying a pre-written essay online or answers to a test

- Falsifying a family emergency to get out of taking a final exam

- Taking a test for a friend

Academic integrity means being honest, ethical, and thorough in your academic work. To maintain academic integrity, you should avoid misleading your readers about any part of your research and refrain from offenses like plagiarism and contract cheating, which are examples of academic misconduct.

Academic dishonesty refers to deceitful or misleading behavior in an academic setting. Academic dishonesty can occur intentionally or unintentionally, and varies in severity.

It can encompass paying for a pre-written essay, cheating on an exam, or committing plagiarism . It can also include helping others cheat, copying a friend’s homework answers, or even pretending to be sick to miss an exam.

Academic dishonesty doesn’t just occur in a classroom setting, but also in research and other academic-adjacent fields.

Consequences of academic dishonesty depend on the severity of the offense and your institution’s policy. They can range from a warning for a first offense to a failing grade in a course to expulsion from your university.

For those in certain fields, such as nursing, engineering, or lab sciences, not learning fundamentals properly can directly impact the health and safety of others. For those working in academia or research, academic dishonesty impacts your professional reputation, leading others to doubt your future work.

Academic dishonesty can be intentional or unintentional, ranging from something as simple as claiming to have read something you didn’t to copying your neighbor’s answers on an exam.

You can commit academic dishonesty with the best of intentions, such as helping a friend cheat on a paper. Severe academic dishonesty can include buying a pre-written essay or the answers to a multiple-choice test, or falsifying a medical emergency to avoid taking a final exam.

The consequences of plagiarism vary depending on the type of plagiarism and the context in which it occurs. For example, submitting a whole paper by someone else will have the most severe consequences, while accidental citation errors are considered less serious.

If you’re a student, then you might fail the course, be suspended or expelled, or be obligated to attend a workshop on plagiarism. It depends on whether it’s your first offense or you’ve done it before.

As an academic or professional, plagiarizing seriously damages your reputation. You might also lose your research funding or your job, and you could even face legal consequences for copyright infringement.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. & Caulfield, J. (2023, April 13). Academic Integrity vs. Academic Dishonesty. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/plagiarism/academic-dishonesty/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, consequences of mild, moderate & severe plagiarism, what is self-plagiarism | definition & how to avoid it, what is your plagiarism score.

Academic Honesty: Why It Matters in Psychology

In psychology, academic honesty is about so much more than getting in trouble..

Posted April 17, 2021 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- All colleges and universities have academic honesty policies with serious consequences.

- Websites that pay to write student papers violate academic honesty and are becoming more abundant and aggressive.

- Academic honesty is inherently psychological, involving questions of curiosity, trust, morality, and future orientation.

The other day, while looking for a free plagiarism checker to use in addition to the one provided by my institution, I came across a website blatantly selling papers to students. This particular site promises, for a high fee per page, to write students completely unique papers that won’t get caught as plagiarism. They’ll even write your Ph.D. dissertation for you (uh…good luck defending that).

All professors are familiar with these sites. The fact that students are paying others to produce work for them is not a secret, at all. Most of us have caught students doing this, or versions of it, and though it’s exhausting and demoralizing, we’ve learned to deal with it semester after semester.

What is academic honesty?

This behavior falls under the heading of “academic honesty.” All colleges and universities have academic honesty policies that address issues like plagiarism and cheating, including serious consequences for violating them. I, for one, am particularly adept at detecting copy/paste/change-a-few-words plagiarism. Frankly, half the time it’s obvious because it’s incomprehensible. As many professors will commiserate, if I wasn’t so good at detecting it, life would be much easier.

Most of us on the policy enforcement side can relate stories with versions of, “But I bought the paper! I didn’t plagiarize, the person who wrote it did! I shouldn’t be held responsible!” In fact, I receive more and more pushback like that every semester: “My cousin wrote the paper for me and I had no idea she plagiarized! She should get in trouble, not me!”

Where does academic dishonesty come from?

We certainly understand that issues like plagiarism may come from lack of confidence in one’s writing skills, being unprepared for college, pressure, inaccessible resources, and the like, but overall, I’ve found it to be a matter of buy-in. Either students buy in to the concept of academic honesty or they don’t, and this has implications beyond school.

How is academic honesty linked to psychology?

I’m less concerned with magically convincing students to follow academic honesty policies than I am in getting them to think about why it is important in the context of psychology. Though I am indeed a prevention practitioner, I’m not naïve enough to think I can change someone’s mind about the value of academic honesty. I am, however, hopeful that those studying psychology will consider the following connections (and then some):

- Learning – You’re not learning much if you’re not doing the work. I once listened to an NPR story about students purchasing papers in which a student said, “I feel like I am doing my own work because I’m using my own money.” Come on. Psychology is all about learning. It’s a topic in every introductory psychology course. It’s usually an entire chapter in introductory psychology textbooks. We have classes specifically focused on it. One of the foundations of learning is that the learner be…involved.

- Morality – “What is moral?” students ask. I can’t answer that, but I am pretty confident that cheating is not. Again, this is a topic that is usually covered in introductory psychology and then over and over again in developmental psychology, social psychology, and more. You’ll even find “moral psychology” as its own field. Psychologist Lawrence Kholberg asked if subjects would steal a drug. Today, he could ask if you’d buy a term paper.

- Future orientation – Personality psychology research suggests that those with a “future orientation” tend to have better outcomes than those with a “present orientation.” The idea is that if you have a future orientation, you tend to, well, look to the future and anticipate future outcomes more than those who are focused solely on the present. While a concern with consequences is associated with mortality (e.g. Kholberg’s theory), the ability or tendency to envision potential consequences is associated with a future orientation. Could there be a more psychological question than, “Is it worth it?”

- Conscientiousness and trust – Conscientiousness is a core personality trait. Trust is essential in development and relationships. Academic dishonesty violates trust and displays low conscientiousness.

- Human services – Students often take psychology because it’s required for medical careers, careers involving working with children, and other human service careers. Go back to the first point about learning. I once had a nurse who tried to inject Heparin directly into my muscle. I had to fight to get her to inject it subcutaneously, as directed. When you work in a hospital, on a general surgery floor, not knowing where to safely inject a blood thinner is alarming. When you don’t do your own work, you don’t have a chance to learn and for a discipline preparing students to work with humans, especially children, everything associated with academic honesty, all of the above, is essential.

- Personal fable – Simply put, this component of David Elkind’s adolescent egocentrism theory suggests that adolescents tend to think they are special and unique. “It might happen to you, but it won’t happen to me.” I can’t tell you how many students are shocked and very angry when caught. In fact, I once read a Twitter thread from professors about the very real dangers associated with catching plagiarism. Many students are still in adolescence , and thinking you’re an exception who won’t get caught is a sure sign.

- Entitlement and violence – Speaking of anger, the idea that you’re special is linked to entitlement , a very psychological concept. In fact, those who study education research “academic entitlement,” in which students feel they should get a good grade just because they attended class or just because they turned in work. Having worked in domestic and sexual violence for a very long time, I know that entitlement is often coupled with violence, as challenges to one’s sense of entitlement frequently result in anger and aggression . Linking homework to violence seems incredible, but it’s a very real possibility.

- Behavioral consistency – As much as we may want to, professors generally can’t share information about other students with other professors. There’s no, “Hey, watch out for this student, they told me their cousin is doing all their homework for them.” However, all academic honesty policies do require some level of reporting to campus administration and they know about behavioral consistency, another psychological concept. This concept suggests that people tend to behave in a consistent manner; they behave in ways that match their past behavior. Need I say more?

One of the main reasons for academic honesty is scientific integrity. I didn’t address it above because, frankly, I find that’s not a very convincing argument, especially when these “pay for us to do your homework” sites target students so aggressively. I found a few more of these sites and recently used their online chat tool. Before I disclosed that I am a professor, and subsequently got kicked off, every single one guaranteed that my professor and my institution “wouldn’t find out.” That’s appalling, not just for the reasons above, but because we do find out, and it can ruin a student’s entire academic career .

Psychology is fascinating and fun. Why wouldn’t you want to learn it, anyway?

Ashley Maier teaches psychology at Los Angeles Valley College.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Teaching Commons Conference 2024

Join us for the Teaching Commons Conference 2024 – Cultivating Connection. Friday, May 10.

Academic Honesty and Stanford's Honor Code

Main navigation.

At Stanford University, the Honor Code is an undertaking of the Stanford academic community, individually and collectively, to uphold a culture of academic integrity in the classroom. Here we offer background information about academic integrity issues in higher education and pedagogic strategies to support and promote academic integrity.

A revised Honor Code was approved by the university community in Spring 2023 , effective September 1, 2023.

The Office of Community Standards (OCS) oversees the Honor Code and alleged student violations. For policies and guidance about Stanford’s Honor Code and the student accountability process please visit the Office of Community Standards website .

What is academic integrity?

The term academic integrity generally means a commitment to a set of fundamental values that support research, learning, scholarship, and service in academia.

At Stanford, the Honor Code is the university's statement on academic integrity, first written by students in 1921. It articulates university expectations of students and faculty in establishing and maintaining the highest standards in academic work.

The Stanford Honor Code

The revised Honor Code (effective September 1, 2023) has been clarified to encourage clear communication between faculty, instructors, and students.

Stanford’s Honor Code has three components:

- Students will support this culture of academic honesty by neither giving nor accepting unpermitted academic aid in any work that serves as a component of grading or evaluation.

- Instructors will support this culture of academic honesty by providing clear guidance, both in their course syllabi and in response to student questions, on what constitutes permitted and unpermitted aid. Instructors will also not take unusual or unreasonable precautions to prevent academic dishonesty.

- Students and instructors will also cultivate an environment conducive to academic integrity. While instructors set academic requirements, the Honor Code is a community undertaking that requires students and instructors to work together to ensure conditions that support academic integrity.

Practices for supporting academic integrity and student learning

Here are some practices that instructors and students in instructional roles can use to promote a learning environment that supports academic integrity and works to uphold the Honor Code.

Many strategies that help students abide by the Honor Code also enhance their learning. While there are many reasons why students, intentionally or unintentionally, might violate the Honor Code, this will likely hinder their learning and compromise their academic experience and, potentially, their future careers.

For details of these and similar strategies, see “ Teaching strategies to support the Honor Code and student learning ”.

Decide on your course policies

What constitutes permitted and unpermitted aid might be different for a course you are leading than for other courses. Depending on your course goals, this might include how to collect and cite research, student collaboration and group work, approved tools, exam protocols, and so on. Be thoughtful as you decide what is appropriate based on the goals of the course, the requirements of the discipline, your teaching philosophy, and the needs of your students.

Guidance on Generative AI

The Office of Community Standards’ (OCS) guidance on generative AI tools states that the use of generative AI tools, like chatbots, image generators, and code generators, is treated analogously to assistance from another person. In particular, using generative AI tools to substantially complete an assignment or exam (e.g. by entering exam or assignment questions) is not permitted. Individual course instructors are free to set their own policies regulating the use of generative AI tools in their courses, including allowing or disallowing some or all uses of such tools.

These pedagogic strategies for adapting to generative AI chatbots can help you determine how to best address generative AI in your course.

Clearly communicate expectations and policies to students and across instructional teams

Discuss the Honor Code and your own individual course policy on academic integrity in your course syllabus. The CTL course syllabus template contains samples of how to do this.

Consider providing examples of what is permissible or not, and review these expectations on the first day of class and before each assignment and assessment. Be prepared to respond to student questions.

Giving a quiz graded on completion to help students identify what is and is not plagiarism can be helpful to check for understanding.

Frame assessments as part of the learning process

Some students may view good grades—or simply submitting a finished assignment—as an end in itself, and so value the outcome more than the learning process. Others might see assessments as unfair or busy work, intended to create high pressure situations, or a way to rank students against each other, rather than to support their learning.

To provide students with a sense of purpose and fairness in assessment, it can be motivating for students to understand the purpose behind the design of the assessment and what you expect to see. Using rubrics for feedback and assessment can make grading more transparent and consistent, so students can demonstrate their learning.

Assessments can be opportunities for students to get valuable feedback, reflect on their learning strategies, and practice important skills. Explain how your assessments support the learning process and encourage them to do their best and be honest, so that the assessment can accurately inform you if they need more help.

Well-designed assessments can reveal where you might improve the course, or areas where students need more support, such as misconceptions they might pick up.

Design assessments that encourage students to demonstrate individual learning

Rather than just ask for an answer to a question that could be provided by another source, ask students to explain how they arrived at that answer. This can give you (and your students) more information to help identify where their gaps in understanding are and requires a more considered and unique response from each student.

Assessments can also be designed to encourage students to demonstrate reasoning and originality . For example:

- Include opportunities for students to demonstrate their problem-solving and reflect on their processes, such as project or problem-based assessments.

- Where suitable, include opportunities for students to demonstrate their originality, such as in personal response papers and creative work.

- Create assessments that require synthesis and critical analysis, such as combining sources and approaches, which also encourage higher-order thinking.

- Get students to show their drafting and editing process alongside finished work.

- Encourage students to think about and respond to contemporary issues or recent questions in the field, where there is less chance an answer that they can copy already exists.

Address the importance of integrity in your field

You can play a valuable role in discussing with students the value of academic integrity in the field of study. What happens if a researcher plagiarizes another scholar’s work? What are the consequences of misrepresenting one’s ideas or falsifying data?

Work with them to foster the habits of academic integrity, such as accurately noting and acknowledging research sources, and being transparent about their methods and sources.

Foster well-being and belonging

Although there are many reasons students may violate the Honor Code, addressing the reasons that students may feel pressured to complete assessments or perform well every time, or other stresses that can affect academic performance, may help mitigate some of these factors.

Consider these optional assessment strategies:

- Frequent and low-stakes assessments : Administering multiple low-stakes assessments reduces the overall weight and stress students associate with each assessment. Students may feel less pressure to take extreme measures to get every answer correct because an incorrect answer will not impact their grades as much. More frequent assessments also provide students with increased opportunities to practice and get feedback on their performance.

- Consider instituting exam or assignment resubmissions : Consider allowing students opportunities to earn points back on questions that they missed. This can be particularly important if you must include an assessment in your course that is worth a large percentage of a student’s grade, but is helpful in any type of assessment to encourage reflection and growth in student learning. This practice not only incentivizes students to learn from their mistakes and fill in their gaps in understanding but also reduces the stress associated with the assessment. This technique also places value on student learning rather than student performance, as students are rewarded for improvement.

- Provide flexibility in final grade components : If an instructor offers a greater number of assessments during the quarter, more flexibility can be given to calculating a student’s final grade. Flexibility can be automatically built into a grading scheme for all students at the start of the quarter by allowing students to drop a number or percentage of assessments. Such flexibility also can assist students who face unexpected difficulties during the quarter without requiring them to disclose details to instructors.

Instructors can also support students’ sense of self-efficacy by regularly encouraging them to connect with various learning programs on campus, such as academic skills coaching , subject matter tutors , and writing tutors .

To mitigate student concerns about the consequences of poor performance, remind students of helpful policies about taking an incomplete or withdrawal .

Consider short and synchronous assessments

Reducing the overall length of an assessment can make it less feasible for students to receive unpermitted help from websites or other sources. Synchronous assessments also remove the temptation or pressure for students to share assessment content with other students completing the assessment at a later time.

Work together with students

The third part of the Honor Code states that both parties must cooperate to establish optimal conditions. Trust between students and faculty is key. Communicate with your students about the Honor Code and consider working with them to adjust as needed your assessments, rubrics, and grading policies over time.

You might invite students into a dialogue about the purpose and uses of AI, collaboration, primary and secondary sources, and so on. Crafting a collaboration and resource policy together can be a valuable learning experience to reflect with students on the purpose of the course, be transparent about learning objectives and pedagogical choices, and encourage buy-in and community-building within the class.

By connecting to student interests and sharing your passion for the subject, students can become more intrinsically motivated to learn for the sake of learning, rather than learning for the sake of a grade (e.g., to perform on a test). This resource on promoting intrinsic motivation has strategies to help you.

What about plagiarism detection tools?

Tools such as Turnitin, Unicheck, and Plagiarism Checker from Grammarly typically compare uploaded student work to a database of other works to detect matches and help determine the originality and sources of the student work. Some plagiarism detection tools also leverage AI technology and can detect AI-generated text to varying degrees of accuracy, but this technology is new and not reliable.

Instructors may use plagiarism detection tools with clear advance notice. Students must be informed that their assignments will be checked with this technology.

See Tips for Faculty & Teaching Assistants on the OCS website for current policy guidance on plagiarism detection tools and the Honor Code.

See also Guidance on technology tools for academic integrity for a more detailed discussion.

What about proctoring exams?

The Honor Code has been clarified to encourage clear communication between faculty, instructors, and students. The revised Honor Code applies to cases filed after September 1, 2023 .

The approved proposal to update the university’s Honor Code includes the addition of new text to improve clarity and to launch an Academic Integrity Working Group (AIWG) to evaluate equitable practices for proctoring in-person examinations through a multi-year study.

The AIWG proctoring study

While the Honor Code no longer explicitly prohibits proctoring, such practices, defined as the reasonable supervision of exams by an exam administrator, are still prohibited unless done as a part of the Academic Integrity Working Group pilot program.

The AIWG will begin its work during the 2023–24 academic year. The study is expected to span two to four academic years. During this time, proctoring will be limited to the few courses that are part of the study. Unless your course is part of the study, proctoring will remain forbidden, and there is no need to adjust your syllabi for proctoring at this time.

- Honor Code , Office of Community Standards (September 2023)

- Interpretations of the Honor Code , Office of Community Standards (Spring 2023)

- What is Plagiarism? , Office of Community Standards

- Tips for Faculty & Teaching Assistants , Office of Community Standards

- Exams and the Honor Code , Office of Community Standards

- Teaching strategies to support the Honor Code and student learning , Teaching Commons (2020)

- Filing an Honor Code concern , Office of Community Standards

- Guidance on technology tools for academic integrity , Teaching Commons

Beck, Victoria. 2014. “ Testing a Model to Predict Online Cheating—Much Ado about Nothing. ” Active Learning in Higher Education 15 (1): 65–75.

Carl Wieman Science Education Initiative. April 2015. Assessments That Support Student Learning .

G. Gibbs and C. Simpson. 2004. “ Conditions Under Which Assessment Supports Student Learning ,” Learning and Teaching in Higher Education , V. 1, pp. 3-31

International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI). 2021. The Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity . (3rd ed.).

Lang, James M. May 28, 2013. “ Cheating Lessons, Part 1. ” The Chronicle of Higher Education .

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Design - Frances Loeb Library

Write and Cite

- Academic Integrity

Responsible research and writing habits

Generative ai (artificial intelligence).

- Citing Sources

- Fair Use, Permissions, and Copyright

- Writing Resources

- Grants and Fellowships

Need Help? Be in Touch.

- Ask a Design Librarian

- Call 617-495-9163

- Text 617-237-6641

- Consult a Librarian

- Workshop Calendar

- Library Hours

Central to any academic writing project is crediting (or citing) someone else' words or ideas. The following sites will help you understand academic writing expectations.

Academic integrity is truthful and responsible representation of yourself and your work by taking credit only for your own ideas and creations and giving credit to the work and ideas of other people. It involves providing attribution (citations and acknowledgments) whenever you include the intellectual property of others—and even your own if it is from a previous project or assignment. Academic integrity also means generating and using accurate data.

Responsible and ethical use of information is foundational to a successful teaching, learning, and research community. Not only does it promote an environment of trust and respect, it also facilitates intellectual conversations and inquiry. Citing your sources shows your expertise and assists others in their research by enabling them to find the original material. It is unfair and wrong to claim or imply that someone else’s work is your own.

Failure to uphold the values of academic integrity at the GSD can result in serious consequences, ranging from re-doing an assignment to expulsion from the program with a sanction on the student’s permanent record and transcript. Outside of academia, such infractions can result in lawsuits and damage to the perpetrator’s reputation and the reputation of their firm/organization. For more details see the Academic Integrity Policy at the GSD.

The GSD’s Academic Integrity Tutorial can help build proficiency in recognizing and practicing ways to avoid plagiarism.

- Avoiding Plagiarism (Purdue OWL) This site has a useful summary with tips on how to avoid accidental plagiarism and a list of what does (and does not) need to be cited. It also includes suggestions of best practices for research and writing.

- How Not to Plagiarize (University of Toronto) Concise explanation and useful Q&A with examples of citing and integrating sources.

This fast-evolving technology is changing academia in ways we are still trying to understand, and both the GSD and Harvard more broadly are working to develop policies and procedures based on careful thought and exploration. At the moment, whether and how AI may be used in student work is left mostly to the discretion of individual instructors. There are some emerging guidelines, however, based on overarching values.

Since policies are changing rapidly, we recommend checking the links below often for new developments, and this page will continue to update as we learn more.

- Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) from HUIT Harvard's Information Technology team has put together this webpage explaining AI and curating resources about initial guidelines, recommendations for prompts, and recommendations of tools with a section specifically on image-based tools.

- Generative AI in Teaching and Learning at the GSD The GSD's evolving policies, information, and guidance for the use of generative AI in teaching and learning at the GSD are detailed here. The policies section includes questions to keep in mind about privacy and copyright, and the section on tools lists AI tools supported at the GSD.

- AI Code of Conduct by MetaLAB A Harvard-affiliated collaborative comprised of faculty and students sets out recommendations for guidelines for the use of AI in courses. The policies set out here are not necessarily adopted by the GSD, but they serve as a good framework for your own thinking about academic integrity and the ethical use of AI.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 1:18 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gsd/write

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Academic Integrity

The topic of academic integrity is often framed around misconduct and dishonesty, carrying both negative and punitive connotations. However, the dialogue is shifting towards an approach that is educative, preventative, and positive in promoting student success. With that shifting focus in mind, this page brings together information from a variety of sources across campus that promote academic integrity from multiple perspectives.

Read more to find out about ways to encourage academic integrity in your courses, what to do when a breach in academic integrity is suspected, and what students need to know regarding ensuring academic integrity, consequences of a breach, and procedures to follow if suspected of a breach in academic integrity.

How is Academic Integrity Defined at UC Berkeley?

There is no single agreed upon definition of academic integrity at UC Berkeley. However, most definitions found in the literature and across higher education institutions consider academic integrity to entail honesty, responsibility, and openness to both scholarship and scholarly activity.

The University defines academic misconduct as “any action or attempted action that may result in creating an unfair academic advantage for oneself or an unfair academic advantage or disadvantage for any other member or members of the academic community” (UC Berkeley Code of Student Conduct).

There is more detailed information related to this definition of academic integrity in the Code of Student Conduct .

See our Campus Policies page for a link to the relevant Berkeley policy.

Review the UC Berkeley Honor Code .

What does Academic Integrity Look Like?

There are countless examples of what academic misconduct and dishonesty look like, and how to avoid them, but too rarely are we given examples (or provide students with examples) of academic integrity, and how to ensure it. Whether it is a matter of semantics or framing, it is helpful to think about academic integrity from a goal-oriented perspective - something we strive to achieve - versus an avoidance perspective where it is something we merely guard against out of fear or anxiety.

Depending on the discipline, instructor preference, goals for student learning, and the nature of the course itself, here are some examples of what academic integrity can look like:

In a class where collaboration is an essential skill to learn, and knowledge is collectively constructed or discovered, students work in small groups on homework assignments in a peer-to-peer learning model. Students still turn in homework individually.

In a writing intensive class, papers are broken up into smaller pieces or several drafts to solicit feedback on the use of and proper credit to the work of others and their ideas - addressing misunderstandings before a summative assignment is due.

In an upper division course, students are encouraged to draw on their previous and complementary coursework in articulating an emerging theoretical framework or analysis through appropriate citation of text and ideas from previous/concurrent writing assignments.

Academic Integrity Through Course Design

Learning environments that reduce the incentive and opportunity for students to cheat can also increase their motivation and mastery of course material. Many times, academic integrity and success are the result of careful planning, preparation, and awareness of resources on the part of the student. In addition to the list below of five potential aspects of a course designed to promote academic integrity and student learning, we have developed an assignment that can be given to students very early in a semester to help chart a Roadmap to Success in any given class.

-Adapted from Lang, J. (2013). Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. ( Available online via the UC Berkeley Library )

Foster Students' Intrinsic Motivation

Instead of thinking about a course as covering certain content in a field, frame the course as an opportunity for students to master the content through engaging open-ended, authentic problems, questions, or challenges.

Engage students in the course through articulating (by both you and them) the relevance of the course material to their current lives, the local community, or their future professions

Place Emphasis on Learning for Mastery Over Performance

Provide students with choices in how they demonstrate learning, whether via options within an assignment or options of assignments, to encourage focus on mastery learning over performance

Use Frequent, Low-Stakes Assessments

Incorporate short breaks in a class, or in the very beginning or end, to ask students questions about content understanding and connections between course material

Decrease the pressure on each assignment as a motivation for dishonesty - in so doing, enable feedback on learning throughout a course, and build student self-efficacy...

Build Student Self-Efficacy

The belief that one is able to achieve the learning expectations of a course diminishes motivation for dishonesty, so instead of using early assignments to "weed students out," try to give students opportunities for early success (rigorous, but achievable)

Convey to students what it takes to be successful in a course (perhaps even quoting effective strategies/practices from former students who excelled in the course)

Prepare Students for Ethical Considerations in the Field/Profession

Introduce students to what it means to have integrity as a psychologist, economist, historian, biologist, etc. and explain why integrity in the field matters

Discuss case studies from the field that reflect both ethical and unethical motives and their outcomes to give students a sense of why developing a habit of integrity in their work now will matter after they graduate

Information for Instructors and Department Chairs

Berkeley honor code.

Honor Code Exam Example

Ways to Incorporate the Honor Code in Your Syllabus

Understanding cultural logic, jason patent, for department chairs: steps to promote academic integrity.

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Promoting Academic Integrity

While it is each student’s responsibility to understand and abide by university standards towards individual work and academic integrity, instructors can help students understand their responsibilities through frank classroom conversations that go beyond policy language to shared values. By creating a learning environment that stimulates engagement and designing assessments that are authentic, instructors can minimize the incidence of academic dishonesty.

Academic dishonesty often takes place because students are overwhelmed with the assignments and they don’t have enough time to complete them. So, in addition to being clear about expectations and responsibilities related to academic integrity, instructors should also invite students to plan accordingly and communicate with them in the event of an emergency. Instructors can arrange extensions and offer solutions in case that students have an emergency. Communication between instructors and students is vital to avoid bad practices and contribute to hold on to the academic integrity values.

The guidance and strategies included in this resource are applicable to courses in any modality (in-person, online, and hybrid) and includes a discussion of addressing generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT with students.

On this page:

What is academic integrity, why does academic dishonesty occur, strategies for promoting academic integrity, academic integrity in the age of artificial intelligence, columbia university resources.

- References and Additional Resources

- Acknowledgment

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Promoting Academic Integrity. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/academic-integrity/

According to the International Center for Academic Integrity , academic integrity is “a commitment, even in the face of adversity, to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage.” We commit to these values to honor the intellectual efforts of the global academic community, of which Columbia University is an integral part.

Academic dishonesty in the classroom occurs when one or more values of academic integrity are violated. While some cases of academic dishonesty are committed intentionally, other cases may be a reflection of something deeper that a student is experiencing, such as language or cultural misunderstandings, insufficient or misguided preparation for exams or papers, a lack of confidence in their ability to learn the subject, or perception that course policies are unfair (Bernard and Keith-Spiegel, 2002).

Some other reasons why students may commit academic dishonesty include:

- Cultural or regional differences in what comprises academic dishonesty

- Lack or poor understanding on how to cite sources correctly

- Misunderstanding directions and/or expectations

- Poor time management, procrastination, or disorganization

- Feeling disconnected from the course, subject, instructor, or material

- Fear of failure or lack of confidence in one’s ability

- Anxiety, depression, other mental health problems

- Peer/family pressure to meet unrealistic expectations

Understanding some of these common reasons can help instructors intentionally design their courses and assessments to pre-empt, and hopefully avoid, instances of academic dishonesty. As Thomas Keith states in “Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem.” faculty and administrators should direct their steps towards a “thoughtful, compassionate pedagogy.”

The CTL is here to help!

The CTL can help you think through your course policies and ways to create community, design course assessments, and set up CourseWorks to promote academic integrity. Email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

In his research on cheating in the college classroom, James Lang argues that “the amount of cheating that takes place on our campuses may well depend on the structures of the learning environment” (Lang, 2013a; Lang, 2013b). Instructors have agency in shaping the classroom learning experience; thus, instances of academic dishonesty can be mitigated by efforts to design a supportive, learning-oriented environment (Bertam, 2017 and 2008).

Understanding Student’s Perceptions about Cheating

It is important to know how students understand critical concepts related to academic integrity such as: cheating, transparency, attribution, intellectual property, etc. As much as they know and understand these concepts, they will be able to show good academic integrity practices.

1. Acknowledge the importance of the research process, not only the outcome, during student learning.

Although the research process is slow and arduous, students should understand the value of the different processes involved during academic writing: investigation, reading, drafting, revising, editing and proof-reading. For Natalie Wexler, using generative Artificial Intelligence tools like ChatGPT as a substitute of writing itself is beyond cheating, an act of self cheating: “The process of writing itself can and should deepen that knowledge and possibly spark new insights” (“‘ Bots’ Can Write Good Essays, But That Doesn’t Make Writing Obsolete” ).

Ways to understand the value of writing their own work without external help, either from external sources, peers or AI, hinge on prioritizing the process over the product:

- Asking students to present drafts of their work and receive feedback can help students to gain confidence to continue researching and writing.

- Allowing students the freedom to choose or change their research topic can increase their investment in an assignment, which can motivate them to conduct their own writing and research rather than relying on AI tools.

2. Create a supportive learning environment

When students feel supported in a course and connected to instructors and/or TAs and their peers, they may be more comfortable asking for help when they don’t understand course material or if they have fallen behind with an assignment.

Ways to support student learning include:

- Convey confidence in your students’ ability to succeed in your course from day one of the course (this may ease student anxiety or imposter syndrome ) and through timely and regular feedback on what they are doing well and areas they can improve on.

- Explain the relevance of the course to students; tell them why it is important that they actually learn the material and develop the skills for themselves. Invite students to connect the course to their goals, studies, or intended career trajectories. Research shows that students’ motivation to learn can help deter instances of academic dishonesty (Lang, 2013a).

- Teach important skills such as taking notes, summarizing arguments, and citing sources. Students may not have developed these skills, or they may bring bad habits from previous learning experiences. Have students practice these skills through exercises (Gonzalez, 2017).

- Provide students multiple opportunities to practice challenging skills and receive immediate feedback in class (e.g., polls, writing activities, “boardwork”). These frequent low-stakes assessments across the semester can “[improve] students’ metacognitive awareness of their learning in the course” (Lang, 2013a, pp. 145).

- Help students manage their time on course tasks by scheduling regular check-ins to reduce students’ last minute efforts or frantic emails about assignment requirements. Establish weekly online office hours and/or be open to appointments outside of standard working hours. This is especially important if students are learning in different time zones. Normalize the use of campus resources and academic support resources that can help address issues or anxieties they may be facing. (See the Columbia University Resources section below for a list of support resources.)

- Provide lists of approved websites and resources that can be used for additional help or research. This is especially important if on-campus materials are not available to online learners. Articulate permitted online “study” resources to be used as learning tools (and not cheating aids – see McKenzie, 2018) and how to cite those in homework, writing assignments or problem sets.

- Encourage TAs (if applicable) to establish good relationships with students and to check-in with you about concerns they may have about students in the course. (Explore the Working with TAs Online resource to learn more about partnering with TAs.)

3. Clarify expectations and establish shared values

In addition to including Columbia’s academic integrity policy on syllabi, go a step further by creating space in the classroom to discuss your expectations regarding academic integrity and what that looks like in your course context. After all, “what reduces cheating on an honor code campus is not the code itself, but the dialogue about academic honesty that the code inspires. ” (Lang, 2013a, pp. 172)

Ways to cultivate a shared sense of responsibility for upholding academic integrity include:

- Ask students to identify goals and expectations around academic integrity in relation to course learning objectives.

- Communicate your expectations and explain your rationale for course policies on artificial intelligence tools, collaborative assignments, late work, proctored exams, missed tests, attendance, extra credit, the use of plagiarism detection software or proctoring software, etc. It will make a difference to take the time at the beginning of the course to explain differences between quoting, summarizing and paraphrasing. Providing examples of good and bad quotation/paraphrasing will help students to know what constitutes good academic writing.

- Define and provide examples for what constitutes plagiarism or other forms of academic dishonesty in your course.

- Invite students to generate ideas for responding to scenarios where they may be pressured to violate the values of academic integrity (e.g.: a friend asks to see their homework, or a friend suggests using chat apps during exams), so students are prepared to react with integrity when suddenly faced with these situations.

- State clearly when collaboration and group learning is permitted and when independent work is expected. Collaboration and group work provide great opportunities to build student-student rapport and classroom community, but at the same time, it can lead students to fall into academic misconduct due to unintended collaboration/failure to safeguard their work.

- Discuss the ethical, academic, and legal repercussions of posting class recordings, notes and/or class materials online (e.g., to sites such as Chegg, GitHub, CourseHero – see Lederman, 2020).

- Partner with TAs (if applicable) and clarify your expectations of them, how they can help promote shared values around academic integrity, and what they should do in cases of suspected cheating or classroom difficulties

4. Design assessments to maximize learning and minimize pressure

High stakes course assessments can be a source of student anxiety. Creating multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning, and spreading assessments throughout the semester can lessen student stress and keep the focus on student learning (see Darby, 2020 for strategies on assessing students online). As Lang explains, “The more assessments you provide, the less pressure you put on students to do well on any single assignment or exam. If you maintain a clear and consistent academic integrity policy, and ensure that all students caught cheating receive an immediate and substantive penalty, the benefit of cheating on any one assessment will be small, while the potential consequences will be high” (Lang, 2013a and Lang, 2013c). For support with creating online exams, please please refer to our Creating Online Exams resource .

Ways to enhance one’s assessment approach:

- Design assignments based on authentic problems in your discipline. Ask students to apply course concepts and materials to a problem or concept.

- Structure assignments into smaller parts (“scaffolding”) that will be submitted and checked throughout the semester. This scaffolding can also help students learn how to tackle large projects by breaking down the tasks.

- Break up a single high-stakes exam into smaller, weekly tests. This can help distribute the weight of grades, and will lessen the pressure students feel when an exam accounts for a large portion of their grade.

- Give students options in how their learning is assessed and/or invite students to present their learning in creative ways (e.g., as a poster, video, story, art project, presentation, or oral exam).

- Provide feedback prior to grading student work. Give students the opportunity to implement the feedback. The revision process encourages student learning, while also lowering the anxiety around any one assignment.

- Utilize multiple low-stakes assignments that prepare students for high-stakes assignments or exams to reduce anxiety (e.g., in-class activities, in-class or online discussions)

- Create grading rubrics and share them with your students and TAs (if applicable) so that expectations are clear, to guide student work, and aid with the feedback process.

- Use individual student portfolio folders and provide tailored feedback to students throughout the semester. This can help foster positive relationships, as well as allow you to watch students’ progress on drafts and outlines. You can also ask students to describe how their drafts have changed and offer rationales for those decisions.

- For exams , consider refreshing tests every term, both in terms of organization and content. Additionally, ground your assignments by having students draw connections between course content and the unique experience of your course in terms of time (unique to the semester), place (unique to campus, local community, etc. ), personal (specific student experiences), and interdisciplinary opportunities (other courses students have taken, co-curricular activities, campus events, etc.). (Lang, 2013a, pp. 77).

Since its release, ChatGPT has raised concern in universities across the country about the opportunity it presents for students to cheat and appropriate AI ideas, texts, and even code as their own work. However, there are also potential positive uses of this tool in the learning process–including as a tool for teachers to rely on when creating assessments or working with repetitive and time-consuming tasks.

Possible Advantages of ChatGPT

Due to the novelty of this tool, the possible advantages that might present in the teaching-learning process should be under the control of each instructor since they know exactly what they expect from students’ work.

Prof. Ethan Mollick teaches innovation and entrepreneurship at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and has been openly sharing on his Twitter account his journey incorporating ChatGPT into his classes. Prof. Mollick advises his students to experiment with this tool, trying and retrying prompts. He recognizes the importance of acknowledging its limits and the risks of violating academic honesty guidelines if the use of this tool is not stated at the end of the assignment.

Prof. Mollick uncovers four possible uses of this AI tool, ranging from using ChatGPT as an all-knowing intern, as a game designer, as an assistant to launch a business, or even to “hallucinate” together ( “Four Paths to the Revelation” ). For Prof. Mollick, ChatGPT is a useful technology to craft initial ideas, as long as the prompts are given within a specific field, include proper context, step-by-step directions and have the proper changes and edits.

Resources for faculty:

- Academic Integrity Best Practices for Faculty (Columbia College & School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

- Faculty Statement on Academic Integrity (Columbia College)

- FAQs: Academic Integrity from Columbia Student Conduct and Community Standards

- Ombuds Office for assistance with academic dishonesty issues.

- Columbia Center of Artificial Intelligence Technology

Resources for students:

- Policies from Columbia Student Conduct and Community Standards

- Understanding the Academic Integrity Policy (Columbia College & School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

Student support resources:

- Maximizing Student Learning Online (Columbia Online)

- Center for Student Advising Tutoring Service (Berick Center for Student Advising)

- Help Rooms and Private Tutors by Department (Berick Center for Student Advising

- Peer Academic Skills Consultants (Berick Center for Student Advising)

- Academic Resource Center (ARC) for School of General Studies

- Center for Engaged Pedagogy (Barnard College)

- Writing Center (for Columbia undergraduate and graduate students)

- Counseling and Psychological Services

- Disability Services

For graduate students:

- Writing Studio (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

- Student Center (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

- Teachers College

Columbia University Information Technology (CUIT) CUIT’s Academic Services provides services that can be used by instructors in their courses such as Turnitin , a plagiarism detection service and online proctoring services such as Proctorio , a remote proctoring service that monitors students taking virtual exams through CourseWorks.

Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) The CTL can help you think through your course policies, ways to create community, design course assessments, and setting up CourseWorks to promote integrity, among other teaching and learning facets. To schedule a one-on-one consultation, please contact the CTL at [email protected] .

References

Bernard, W. Jr. and Keith-Spiegel, P. (2002). Academic Dishonesty: An Educator’s Guide . Mahwah, NJ: Psychology Press.

Bertram Gallant, T. (2017). Academic Integrity as a Teaching and Learning Issue: From Theory to Practice . Theory Into Practice, 56(2), 88-94.

Bertram Gallant, T. (Ed.). (2008). Academic Integrity in the Twenty-First Century: A Teaching and Learning Imperative . ASHE Higher Education Report . 33(5), 1-143.

Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Creating Online Exams .

Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Working with TAs online .

Darby, F. (2020). 7 Ways to Assess Students Online and Minimize Cheating . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Gonzalez, J. (2017, February). Teaching Students to Avoid Plagiarism . Cult of Pedagogy, 26.

International Center for Academic Integrity (2023). Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity .

International Center on Academic Integrity (2023). https://academicintegrity.org/

Keith, T. Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem. The University of Chicago. (2022, Feb 16).

Lang, J.M. (2013a). Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty . Harvard University Press.

Lang, J. M. (2013b). Cheating Lessons, Part 1 . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lang, J. M. (2013c). Cheating Lessons, Part 2 . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lederman, D. (2020, February 19). Course Hero Woos Professors . Inside Higher Ed.

McKenzie, L. (2018, May 8). Learning Tool or Cheating Aid? Inside Higher Ed.

Marche, S. (2022, Dec 6). The College Essay is Dead. The Atlantic.

Mollick, E. (2023, Jan 17). All my Classes Suddenly Became AI Classes. One Useful Thing.

Mollick, Ethan. (2022, Dic 8). Four Paths to the Revelation. One Useful Thing.

Wexler, N. Bots’ Can Write Good Essays, But That Doesn’t Make Writing Obsolete. Minding the Gap.

Additional Resources

Bretag, T. (Ed.). (2016). Handbook of Academic Integrity. Singapore: Springer Publishing.

Ormand, C. (2017 March 6). SAGE Musings: Minimizing and Dealing with Academic Dishonesty . SAGE 2YC: 2YC Faculty as Agents of Change.

WCET (2009). Best Practice Strategies to Promote Academic Integrity in Online Education .

Thomas, K. (2022 February 16). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 February 25). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 2: Small Steps to Discourage Academic Dishonesty. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 April 28). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 3: Towards a Pedagogy of Academic Integrity. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 June 7). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 4: Library Services to Support Academic Honesty. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

Acknowledgement

This resource was adapted from the faculty booklet Promoting Academic Integrity & Preventing Academic Dishonesty: Best Practices at Columbia University developed by Victoria Malaney Brown, Director of Academic Integrity at Columbia College and Columbia Engineering, Abigail MacBain and Ramón Flores Pinedo, PhD students in GSAS. We would like to thank them for their extensive support in creating this academic integrity resource.

Want to communicate your expectations around AI tools?

See the CTL’s resource “Considerations for AI Tools in the Classroom.”

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

A Guide To...Academic Honesty and Academic Integrity

Academic integrity.

- Find your department's statement on Academic Integrity

- Take the quiz

- The Writer's Workshop at Holy Cross

- Schedule an appointment with a Librarian

- The Purdue OWL

Notable cases of plagiarism

Rand Paul (R)

Kentucky Senator 2011 -

Blake, A. (2013, November 4). Rand Paul's plagiarism allegations, and why they matter . The Washington Post.

Stephen Ambrose, 1936-2002

American historian and author

Kirkpatrick, D. D. (2002, January 5). 2 say Stephen Ambrose, popular historian, copied passages . The New York Times.

Alex Haley, 1921-1992

Fulwood, S. I. (2003). Plagiarism playing by the rules: in the academic world, in music and even in church, what constitutes plagiarism is under new scrutiny after journalism's wake-up call . Black Issues Book Review, (5). 24.

Academic Honesty means being honest and ethical about the way that you do academic work. This includes citing and acknowledging when you borrow from the work of others. As Holy Cross students, you are required to follow the College's Academic Honesty policy.

Excerpt from the College policy:

All education is a cooperative enterprise between faculty and students. This cooperation requires trust and mutual respect, which are only possible in an environment governed by the principles of academic honesty. As an institution devoted to teaching, learning, and intellectual inquiry, Holy Cross expects all members of the College community to abide by the highest standards of academic integrity. Any violation of academic honesty undermines the student-faculty relationship, thereby wounding the whole community. The principal violations of academic honesty are plagiarism, cheating, and collusion.

It is the responsibility of students, independent of the faculty’s responsibility, t o understand the proper methods of using and quoting from source materials (as explained in standard handbooks such as The Little Brown Handbook and the Harbrace College Handbook), and t o take credit only for work they have completed through their own individual efforts within the guidelines established by the faculty.

The Scholarly Conversation

Tips for Avoiding Plagiarism

- What needs to be cited?

- Tips for the research process

What needs to be cited? In addition to citing exact quotations from your sources, you need to cite any ideas or words that you did not think up yourself. You should always cite:

- Anything you summarize from another source

- Websites (even if there is no author listed)

- Information you received from other people, such as information learned during interviews

- Graphs, illustrations, and any other visual items you use in your work. (This includes images from websites.)

- Video and audio recordings that you sample in your work.

Some things that you don't need to cite:

- Your own life experiences or ideas

- Your own results from lab or field experiments

- Any artwork or media you have created yourself

- “Common knowledge” (This is information that can be found undocumented in many places and is likely to be known by many people.)

Good practices for taking notes:

Before writing a note, read the original text over until you understand the meaning.

Use quotation marks around any exact phrasing you use from the original source.

While you are taking your notes, record the source for each piece of information (including page numbers) in you notes so that you’ll be able to cite the source in your paper.

Use a variety of sources in your research. If you use only one source, you may end up using too many of that author’s ideas and words.

Plan ahead and leave yourself enough time to do your research and writing. If you are rushing to finish your paper, you’ll be more likely to improperly cite things or to accidentally plagiarize.

College policy and definitions

Academic Honesty Policy

-accessed 4/1/2019 from https://www.holycross.edu/sites/default/files/Registrar/academic_integrity_policy.pdf

Plagiarism is the act of taking the words, ideas, data, illustrative material, or statements of someone else, without full and proper acknowledgment, and presenting them as one’s own.

Cheating is the use of improper means or subterfuge to gain credit or advantage. Forms of cheating include the use, attempted use, or improper possession of unauthorized aids in any examination or other academic exercise submitted for evaluation; the fabrication or falsification of data; misrepresentation of academic or extracurricular credentials; and deceitful performance on placement examinations. It is also cheating to submit the same work for credit in more than one course, except as authorized in advance by the course instructors. Collusion is assisting or attempting to assist another student in an act of academic dishonesty.

At the beginning of each course, the faculty should address the students on academic integrity and how it applies to the assignments for the course. The faculty should also make every effort, through vigilance and through the nature of the assignments, to discourage and prevent dishonesty in any form. It is the responsibility of students, independent of the faculty’s responsibility, to understand the proper methods of using and quoting from source materials (as explained in standard handbooks such as The Little Brown Handbook and the Harbrace College Handbook), and to take credit only for work they have completed through their own individual efforts within the guidelines established by the faculty.

The faculty member who observes or suspects academic dishonesty should first discuss the incident with the student. The very nature of the faculty-student relationship requires both that the faculty member treat the student fairly and that the student responds honestly to the faculty’s questions concerning the integrity of his or her work. If the faculty is convinced that the student is guilty of academic dishonesty, he or she shall impose an appropriate sanction in the form of a grade reduction or failing grade on the assignment in question and/or shall assign compensatory course work. The sanction may reflect the seriousness of the dishonesty and the faculty’s assessment of the student’s intent. In all instances where a faculty member does impose a grade penalty because of academic dishonesty, he or she must submit a written report to the Chair or Director of the department and the Class Dean. This written report must be submitted within a week of the faculty member’s determination that the policy on academic honesty has been violated. This report shall include a description of the assignment (and any related materials, such as guidelines, syllabus entries, written instructions, and the like that are relevant to the assignment), the evidence used to support the complaint, and a summary of the conversation between the student and the faculty member regarding the complaint. The Class Dean will then inform the student in writing that a charge of dishonesty has been made and of his or her right to have the charge reviewed. A copy of this letter will be sent to the student’s parents or guardians. The student will also receive a copy of the complaint and all supporting materials submitted by the professor. The student’s request for a formal review must be made in writing to the Class Dean within one week of the notification of the charge. The written statement must include a description of the student’s position concerning the charge by the faculty. A review panel consisting of a ClassDean, the Chair or Director of the department of the faculty member involved (or a senior member of the same department if the Chair or Director is the complainant), and an additional faculty member selected by the Chair or Director from the same department, shall convene within two weeks to investigate the charge and review the student’s statement, meeting separately with the student and the faculty member involved. The Chair or Director of the complainant’s department (or the alternate) shall chair the panel and communicate the panel’s decision to the student’s Class Dean. If the panel finds by majority vote that the charge of dishonesty is supported, the faculty member’s initial written report to the Class Dean shall be placed in the student’s file until graduation, at which time it shall be removed and destroyed unless a second offense occurs. If a majority of the panel finds that the charge of dishonesty is not supported, the faculty member’s initial complaint shall be destroyed, and the assignment in question shall be graded on its merits by the faculty member. The Class Dean shall inform the student promptly of the decision made. This information will be sent to the student’s parents or guardians. The Class Dean may extend all notification deadlines above for compelling reasons. He or she will notify all parties in writing of any extensions. Each instance of academic dishonesty reported to the Class Dean (provided that the charge of dishonesty is upheld following a possible review, as described above) shall result in an administrative penalty in addition to the penalty imposed by the faculty member.

For a first instance of academic dishonesty, the penalty shall be academic probation effective immediately and continuing for the next two consecutive semesters. For a second instance, the penalty shall be academic suspension for two consecutive semesters. For a third instance, the penalty shall be dismissal from the College. Dismissal from the College shall also be the penalty for any instance of academic dishonesty that occurs while a student is on probation because of a prior instance of dishonesty. Multiple charges of academic dishonesty filed at or about the same time shall result in a one-year suspension if the student is not and has not been on probation for a prior instance of dishonesty. Multiple charges of academic dishonesty filed at or about the same time shall result in a dismissal if the student has ever been on probation for a prior instance of dishonesty. Suspension and dismissal are effective at the conclusion of the semester in which the violation of the policy occurred. Students may appeal a suspension or dismissal for reasons of academic dishonesty to the Committee on Academic Standing, which may uphold the penalty, overturn it, or substitute a lesser penalty. A penalty of dismissal, if upheld by the Committee, may be appealed to the President of the College.

- Next: Find your department's statement on Academic Integrity >>

- Last Updated: Mar 12, 2024 12:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.holycross.edu/academichonesty

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

A Positive Approach to Academic Integrity

In 2017, 83 Ohio State students were reported for using an app called GroupMe to share quiz questions and answers (Bever, 2017). At universities across the nation, students have cheated using various apps and technology. Increased access to technology tools does provide additional avenues for cheating, but the availability of these new tools has not led to more cheating (see Lang, 2013).

Still, preventing academic misconduct is a topic that weighs on many instructors’ minds. We want students to learn and to come by their degrees honestly. The good news is that the educator’s role in academic honesty does not always have to be punitive or after-the-fact. Proactively promoting academic integrity in positive ways can reduce the likelihood that students will commit misconduct.

In the United States, public attitudes about academic misconduct range from mild irritation at the existence of cheating to the moral outrage one might show toward hard criminal offenses. In an effort to reduce cheating, instructors often implement defensive measures. For example, using a digital plagiarism detector such as Turnitin is meant to deter students from plagiarizing in their writing and to catch the ones who do so. Setting time limits for synchronous online exams is a common tactic for reducing the time available for students to use the textbook or a website like Chegg to solve their problems for them.

But telling students not to cheat—and what will happen to them if they do—only goes so far in deterring academic misconduct.

Underneath those dos and don’ts are implicit values present in the American system of higher education. What if we openly communicated those values instead?

What do we value?

The concept of academic integrity is often taught with a focus on academic misconduct and how not to misbehave. Students navigate through college trying not to break the rules. Underneath those rules lie traits that are valued in our education system, and in scholarly work. For example, we trust that a student who can explain a concept in their own words rather than quoting a text has truly learned that concept. We also value original thought and the individual voice in scholarly conversation. We place importance on respecting what writers and researchers contribute to the conversation, and on distinguishing who said what.

For a brief history on the development of intellectual property, see Bloch, 2012, Chapter 2.

Do students understand what academic integrity is?

Bretag and colleagues (2014) discuss two main types of research into academic integrity: student self-reports about their cheating behaviors and research on students’ understanding of academic integrity. Based on surveys of students at multiple institutions, they found that students had some idea of what academic integrity is but did not feel they received enough support for how to practice it effectively, beyond the generic information provided early in their college careers. In one of the surveys, students indicated that instructors’ expectations varied and that conventions were not uniform across courses, and that knowing what happens when you commit academic misconduct is not helpful.

Learning disciplinary practices

Nelms (2015) points out that many students plagiarize unintentionally on their way to becoming more expert in their fields. As novice students learn to use the language of their disciplines, they may begin by imitating the language that they are reading. He provides a positive view of plagiarism as an opportunity to help students develop their own voices and learn to participate in scholarly conversation. By viewing students first as learners, it is possible to create penalties that are educational rather than punitive (Morris, 2016).

English language learners

It’s especially critical to support English language learners writing in a non-native language to understand academic integrity expectations. Rhetorical styles and conventions vary around the world. Students who were not educated in the United States may have learned practices surrounding academic integrity that do not align with the Western conventions of incorporating and citing scholarly work, and therefore face a steeper learning curve.

Explore resources for supporting international students with writing from Writing Across the Curriculum.

The learning environment

In Cheating Lessons (2013), James Lang examines how features of a learning environment might lead to increased academic misconduct. He argues that instructors can influence these features directly. They are (p. 35):

Emphasis on performance : Students who are more concerned with doing well on a test than with learning are more likely to cheat on that test. If an instructor overemphasizes grades, the focus on performance can put pressure on students and become a dominant feature of the learning environment.

High stakes : If a student’s grade is determined by one or two assessments, such as a midterm (at 50% of the grade) and a final (the other 50% of the grade), cheating is more likely. In such a class, students are not receiving regular feedback on their work, and only have two chances to demonstrate their learning.