Mother Tongue Summary, Purpose and Themes

Amy Tan’s “Mother Tongue” is a compelling exploration of language, identity, and familial bonds.

This nonfiction narrative essay, which debuted at the 1989 State of the Language Symposium and was later published in The Threepenny Review in 1990, delves into Tan’s multifaceted relationship with English, influenced significantly by her mother, a Chinese immigrant.

Full Summary

The essay unfolds in three distinct sections.

Initially, Tan introduces us to the concept of “different Englishes,” a theme central to the narrative. She describes the unique form of English spoken by her mother, referred to as her “mother’s English” or “mother tongue.” This language, distinct yet familiar, bridges the first and second parts of the essay.

In the heart of the essay, Tan reflects on the profound impact her mother’s language had on her life and identity. She recalls how her mother, not fluent in “perfect English,” often depended on Tan to bridge communication gaps. This experience shapes Tan’s understanding of language and its nuances.

The essay culminates in a powerful conclusion where Tan connects the dots between her mother’s English and her own writing style and career choices. She recounts how her mother’s presence at a talk for her book “The Joy Luck Club” triggered a realization about the various forms of English she uses.

Tan contrasts the English she speaks at home, her “mother tongue,” with the standard English she learned in school and uses in professional settings. Notably, Tan shifts languages seamlessly, a transition unnoticed by others, including her husband.

Tan shares anecdotes from her past, illustrating how her mother’s language shaped her. She resists describing her mother’s English as “broken,” arguing that it implies deficiency. Instead, she views it as a reflection of others’ limited perceptions.

This perspective is highlighted by the dismissive attitudes of her mother’s stockbroker and doctors, who fail to take her mother seriously, often necessitating Tan’s intervention.

Reflecting on her own journey with English, Tan discusses the challenges she faced in school, influenced by her mother’s unique use of the language. However, this challenge becomes a source of motivation rather than defeat.

Tan’s determination to “master” English leads her to initially distance herself from her “mother tongue.”

It’s not until she begins writing “The Joy Luck Club” that Tan realizes the inaccessibility of the English she was using.

Reconnecting with her “mother tongue,” Tan finds her authentic voice—one deeply influenced and cherished, the voice of her mother. In “Mother Tongue,” Tan not only narrates her personal journey with language but also raises profound questions about identity, culture, and the intrinsic power of language.

The purpose of Amy Tan’s essay “Mother Tongue” is multifaceted, encompassing several key themes and objectives:

- Exploration of Language and Identity : Tan delves into how language shapes identity. By discussing the different forms of English she uses, she illustrates how language is deeply intertwined with personal and cultural identity. The essay emphasizes that the way we speak and the language we use are integral parts of who we are.

- Highlighting Linguistic Diversity and Acceptance : Tan challenges the notion of standard English, advocating for the recognition and acceptance of linguistic diversity. She highlights the richness and complexity of her mother’s version of English, urging readers to reconsider what constitutes “proper” language.

- Examination of Mother-Daughter Relationships : The essay is also a reflection on Tan’s relationship with her mother. Through the lens of language, Tan explores the dynamics of their bond, emphasizing how language both connects and separates them.

- Commentary on Perception and Misunderstanding : Tan addresses how people are often judged based on their language proficiency. Her mother’s experiences with her stockbroker and doctors showcase the misunderstandings and dismissals non-native speakers frequently face. The essay serves as a critique of these societal attitudes.

- Personal Growth and Self-Discovery : “Mother Tongue” is also a story of Tan’s personal journey in understanding her own linguistic heritage and how it has shaped her as a writer and individual. She discusses her initial struggles and eventual acceptance and embrace of her linguistic roots, which significantly influenced her writing style.

- Cultural Representation and Advocacy : By sharing her experiences, Tan advocates for cultural representation and the importance of diverse voices in literature. Her journey to include her mother’s language in her writing is a statement about the value of different cultural perspectives in storytelling.

1. The Complexity and Impact of Language

Amy Tan’s “Mother Tongue” intricately explores the multifaceted nature of language and its profound impact on personal identity and relationships.

The essay delves into the concept of “different Englishes” that Tan encounters and navigates throughout her life. These variations of English—ranging from the standard forms learned in school to the unique, simplified version spoken by her mother—serve as a backdrop for examining how language shapes our understanding of the world and each other.

Tan’s narrative highlights the often overlooked nuances of language, demonstrating how the mastery or lack of mastery of a certain type of language can influence perceptions, opportunities, and interpersonal dynamics.

Her reflections on the dismissive treatment her mother receives due to her non-standard English usage poignantly underscore the societal judgments and barriers language can create.

2. Identity and Cultural Heritage

Central to “Mother Tongue” is the theme of identity, particularly how it is intertwined with cultural heritage and language.

Tan’s own sense of self is deeply connected to her mother’s “mother tongue,” an embodiment of her Chinese heritage. This connection is not just linguistic but also emotional and cultural.

Through her narrative, Tan explores the struggles of balancing her American upbringing with her Chinese heritage, a challenge faced by many children of immigrants.

The essay illustrates how language serves as a bridge and a barrier between her American identity and her Chinese roots.

Tan’s journey of embracing her mother’s English is, in essence, a journey of embracing her own cultural identity, showcasing the complexity of navigating dual heritages.

3. The Power of Voice and Self-Expression

“Mother Tongue” is also a profound exploration of the power of finding one’s voice and the importance of self-expression. Tan’s journey as a writer is central to this theme.

Initially, she struggles with standard English, perceiving it as the only legitimate form of expression in academic and professional realms.

This belief leads her to distance herself from her “mother tongue,” which she initially views as inferior. However, as she evolves as a writer, particularly while working on “The Joy Luck Club,” Tan discovers the richness and authenticity of her mother’s language.

This revelation allows her to find her true voice—a blend of her mother’s English and the standard English she has mastered.

Tan’s embracing of her unique linguistic heritage as a tool for storytelling and self-expression underscores the empowering nature of owning and using one’s individual voice, transcending conventional linguistic boundaries.

Final Thoughts

“Amy Tan’s ‘Mother Tongue’ is an insightful reflection on language, culture, and identity. Through her personal narrative, Tan eloquently demonstrates how language is not just a tool for communication but a significant factor in shaping our experiences, perceptions, and relationships.

Her essay underscores the importance of embracing linguistic diversity and challenges the conventional notion of ‘standard’ language, advocating for a broader understanding and acceptance of different forms of expression.

Sharing is Caring!

A team of Editors at Books That Slay.

Passionate | Curious | Permanent Bibliophiles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Mother Tongue

44 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “mother tongue”.

“Mother Tongue” explores Amy Tan’s relationship with the English language, her mother, and writing. This nonfiction narrative essay was originally given as a talk during the 1989 State of the Language Symposium; it was later published by The Threepenny Review in 1990. Since then, “Mother Tongue” has been anthologized countless times and won notable awards and honors, including being selected for the 1991 edition of Best American Essays .

The original publication of “Mother Tongue,” which this study guide refers to, breaks the essay into three sections. In the first Tan briefly primes the reader on her relationship with “different Englishes” (7). Tan bridges the first and second parts of the essay with descriptions of her “mother’s English,” or her “mother tongue” (7). In the second section Tan describes the impact her mother’s language had on her; Tan’s mother is a Chinese immigrant who often relied on her daughter to produce “perfect English” (7). In the concluding section Tan then connects her mother’s English to Tan’s own choices regarding writing style and career.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,400+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,900+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

In the initial section of “Mother Tongue,” Amy Tan locates her position as “a writer… someone who has always loved language” (7). She describes the multiple Englishes that she uses, from formal academic language to the English she uses with her mother to the English she uses at home with her husband. The section concludes with Tan’s description of her mother’s “expressive command of English” (7), which is in conflict with her mother’s fluency in the language. Although her mother might speak English that is difficult for native speakers to understand, to Tan, her mother’s language is “vivid, direct, full of observation and imagery” (7).

As Tan moves through the second section of “Mother Tongue,” she describes some of the more difficult aspects of being raised by a parent who spoke English that others struggled to understand. Tan references the oft-used language of “broken” English and suggests that her mother’s English and way of speaking, despite its obvious interpersonal and social limitations (including harming Tan’s performance on such metrics as standardized tests), provided Tan a different semantic way of understanding the world.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

The final section of “Mother Tongue” transitions into personal reflection as Tan describes how she has reckoned with being raised by her mother in a xenophobic society. As a writer, Tan only found success when she moved away from more proper, academic register and instead wrote “in the Englishes [she] grew up with” (8). The essay concludes with Tan’s mother’s opinion about Tan’s most famous novel, The Joy Luck Club , in which Tan attempted to write in this fashion. Her mother’s “verdict: ‘So easy to read’” (8).

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

A Pair of Tickets

Fish Cheeks

Rules of the Game

Saving Fish from Drowning

The Bonesetter's Daughter

The Hundred Secret Senses

The Joy Luck Club

The Kitchen God's Wife

The Valley of Amazement

Featured Collections

Books on Justice & Injustice

View Collection

Chinese Studies

Essays & Speeches

Mother Tongue

Ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on Amy Tan's Mother Tongue . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

Mother Tongue: Introduction

Mother tongue: plot summary, mother tongue: detailed summary & analysis, mother tongue: themes, mother tongue: quotes, mother tongue: characters, mother tongue: terms, mother tongue: symbols, mother tongue: theme wheel, brief biography of amy tan.

Historical Context of Mother Tongue

Other books related to mother tongue.

- Full Title: Mother Tongue

- When Written: 1989

- When Published: 1990

- Literary Period: Contemporary

- Genre: Essay, Memoir

- Setting: Oakland, California; San Francisco, California; New York City, New York

- Climax: Tan’s mother attends one of her talks about The Joy Luck Club .

- Antagonist: Societal ignorance and bias

- Point of View: First Person

Extra Credit for Mother Tongue

Sagwa. Tan’s 1994 children’s book, The Chinese Siamese Cat , was adapted for television and broadcast by PBS as “Sagwa The Chinese Siamese Cat.” First aired in 2001, the series follows Sagwa, the protagonist kitten, on her adventures as a palace cat in historic China.

Music. Tan’s talents aren’t limited to pen and paper. A member of the band “Rock Bottom Remainders” since 1993, Tan has performed with fellow authors Stephen King, Dave Barry, and Scott Turow.

Exploring Language and Identity: Amy Tan's "Mother Tongue" and Beyond

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

In the essay “Mother Tongue,” Amy Tan explains that she “began to write stories using all the Englishes I grew up with.” How these “different Englishes” or even a language other than English contribute to identity is a crucial issue for adolescents. In this lesson, students explore this issue by brainstorming the different languages they use in speaking and writing, and when and where these languages are appropriate. They write in their journals about a time when someone made an assumption about them based on their use of language, and share their writing with the class. Students then read and discuss Amy Tan's essay “Mother Tongue.” Finally, they write a literacy narrative describing two different languages they use and when and where they use these languages.

Featured Resources

Discussion Questions for "Mother Tongue" : Have students discuss Amy Tan's essay in small groups, using these discussion questions.

Literacy Narrative Assignment : This handout describes an assignment in which students write a literacy narrative exploring their use of different language in different settings.

From Theory to Practice

NCTE has long held a commitment to the importance of individual student's language choices. In the 1974 Resolution on the Students' Right to Their Own Language , council members "affirm[ed] the students' right to their own language-to the dialect that expresses their family and community identity, the idiolect that expresses their unique personal identity." The Council reaffirmed this resolution in 2003 , "because issues of language variation and education continue to be of major concern in the twenty-first century to educators, educational policymakers, students, parents, and the general public."

Rebecca Wheeler and Rachel Swords assert that: "the child who speaks in a vernacular dialect is not making language errors; instead, she or he is speaking correctly in the language of the home discourse community. Teachers can draw upon the language strengths of urban learners to help students codeswitch-choose the language variety appropriate to the time, place, audience, and communicative purpose. In doing so, we honor linguistic and cultural diversity, all the while fostering students' mastery of the Language of Wider Communication, the de-facto lingua franca of the U.S."

This lesson focuses on ways to investigate the issues of language and identity in the classroom in ways that validate the many languages that students use. To help students gain competence in their ability to choose the right language usage for each situation, explorations of language and identity in the classroom are vital in raising students' awareness of the languages they use and the importance of the decisions that they make as they communicate with others.

Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 9. Students develop an understanding of and respect for diversity in language use, patterns, and dialects across cultures, ethnic groups, geographic regions, and social roles.

- 10. Students whose first language is not English make use of their first language to develop competency in the English language arts and to develop understanding of content across the curriculum.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

Materials and Technology

- Copy of "Mother Tongue" by Amy Tan

- Blue pens, Black pens, and pencils (optional)

- Discussion Questions for "Mother Tongue"

- Literacy Narrative Assignment

- Essay Rubric

- Student Self-Assessment

Preparation

- Arrange for copies of the essay "Mother Tongue" by Amy Tan. The essay is widely anthologized. It was originally published in The Threepenny Review in 1990.

- Make an overhead transparency of the Discussion Questions for "Mother Tongue," or arrange for an LCD projector to show the questions to the class.

- Make copies of the Literacy Narrative Assignment , Literacy Narrative Rubric , and Student Self-Assessment .

- Test the Venn Diagram on your computers to familiarize yourself with the tools and ensure that you have the Flash plug-in installed. You can download the plug-in from the technical support page.

Student Objectives

Students will

- develop critical reading strategies.

- discuss and evaluate the impact of language on identity formation and self-esteem of several writers.

- expand their awareness of the role language plays in identity formation.

- write their own literacy narratives.

Session One

What are the different "languages" you use? When and why? Consider both reading and writing, and don't forget about email! If you speak another language, include it (or possibly them if you know more than one).

- Encourage students to read their responses aloud.

- As they do, keep track on the board or on an overhead transparency of the different "languages" they are describing.

- Discuss the interaction of language usage and choice with audience and occasion by focusing on the examples the students have provided.

- For homework, ask students to write a journal entry that describes a time when someone made assumptions or even a judgment (negative or positive) about them based on their language usage (written or spoken). For those who say they've never had such an experience, suggest writing about a situation they've observed involving someone else.

Session Two

- Open the class by asking volunteers to share their journal entries.

- Look for similarities among the experiences students describe, and discuss them as a group. Ask whether they notice stereotypes at work in the situations they describe.

- If students have access to the Internet, introduce Amy Tan by sharing audio and video clips of her talking and reading. Biographical information about Amy Tan can be found at Bookreporter.com .

- Hand out copies of "Mother Tongue," and read the first two paragraphs aloud.

- Discuss why Tan opens with an explanation of what she is not .

- Read the next two paragraphs. Ask students to explain what Tan means by "different Englishes."

- Shift the discussion by asking why Tan speaks a "different English" with her mother than with her husband. Ask students to consider whether doing so is hypocritical.

- Assign the remainder of the essay as reading for homework.

Session Three

- What point is Tan making with the example of her mother and the hospital?

- What point is she making with the example of the stockbroker?

- Tan says that experts believe that a person's "developing language skills are more influenced by peers," yet she thinks that family is more influential, "especially in immigrant families." Do you think family or peers exert more influence on a person's language?

- Why does Tan discuss the SAT and her performance on it?

- Why does she envision her mother as the reader of her novels?

- After about 15 minutes, ask each group to explain their responses to the questions. Encourage them to support their responses with specific reference to Tan's essay.

- Ask them to write notes and ideas in their journals using the Literacy Narrative Assignment . Stress that students are only gathering ideas. They are not creating the polished essay at this point.

Session Four

- Open by discussing the assignment itself. Explain that a literacy narrative tells a specific story about reading or writing. Tan's article is essentially a literacy narrative because it discusses events about language use from her past (whether good or bad) and reflects on how those events influence her writing today.

- If desired, ask students to choose examples from the essay that connect writing from Tan's past to her present.

- Pass out copies of the Essay Rubric , and discuss the required components for the finished paper.

- Discuss the possibilities that students raised in their journal entries.

- To begin developing ideas further, ask students to use the Venn Diagram to map and compare the two "languages" that they will explore in their essays. Ask them to think creatively about the qualities and characteristics of the "languages."

- Allow students time to work on their literacy narratives in class.

- Assign a draft of the literacy narrative as homework; each student should bring his or her draft to the next class session (on a disk if you are working in a computer lab, or a printed copy otherwise).

- Additionally, if you are not working in a computer lab, ask students to bring a pencil, a black pen, and a blue pen to class.

Session Five

- Begin with a discussion of the problems students are encountering with the assignment.

- Brainstorm ways to address one or two of the challenges.

- Remind students of the criteria for the assignment in the Literacy Narrative Essay Rubric . For the peer review, ask students to compare the drafts that they read to the characteristics described in the rubric.

- Each student will read three papers, each written by someone else.

- On the first paper that you read, make your comments with your black ink pen or in bold.

- On the second paper, make your comments with the blue ink pen or in italics.

- On the third paper, make your comments with your pencil or with underlined letters.

- Finally, you'll return to your own essay and read over the comments.

- Arrange the students in small groups of four, having students rotate the drafts among group members as they read and respond. Adjust groupings as needed to accommodate the number of students in your class.

- Once students have read and responded to all the drafts, discuss questions, comments, and concerns students have as they prepare to revise.

- Encourage students to pay particular attention to comments that all of their peer readers agreed upon when reading their drafts.

- For homework, have students create their final, polished draft of the literacy narratives. Collect the papers at the beginning of the next session.

- To explore a more controversial response to language usage, students might read "If Black English Isn't a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is" by African American author James Baldwin. Written before the term "ebonics" came into usage, it is a brief but highly political argument about the link between language and identity and the damage school systems can cause by privileging one language (or dialect) over another. It can be found in the New York Times archives (29 July 1979, page E19).

- Students also might examine a passage from the fiction of Cormac McCarthy, Sandra Cisneros, or another author who includes Spanish in his or her work—without translating it. What is the effect on a reader who does not know Spanish? What might be the purpose of an author making the decision to write whole sections in Spanish?

- To pursue the link between power and language, students might read the poem "Parsley" by Rita Dove. It explores the historical incident in which the Dominical Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo used the pronunciation of the word "parsley" to separate Dominicans who speak Spanish from the persecuted Haitians who speak a French Creole (a topic Edwidge Danticat takes up in her novel The Farming of Bones ).

Student Assessment / Reflections

Observe students for their participation during the exploration and discussion of Tan’s essay and their own language use. In class discussions and conferences, watch for evidence that students are able to describe specific details about their language use. Monitor students’ progress and process as they work on their lilteracy narratives. For formal assessment, use the Literacy Narrative Rubric . Ask students to complete the Student Self-Assessment to reflect on their exploration of language and their literacy narratives.

- Calendar Activities

- Professional Library

- Student Interactives

Students consider the portrayal of Asians in popular culture by exploring images from classic and contemporary films and comparing them to historical and cultural reference materials.

This interactive tool allows students to create Venn diagrams that contain two or three overlapping circles, enabling them to organize their information logically.

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Amy Tan’s “Mother Tongue” : Rhetorical Analysis

In the essay Mother Tongue , Amy Tan believes that everyone speaks different languages in certain settings and are labeled by the way they speak. The author interested by how language is utilized in our daily life” and uses language as a daily part of her work as a writer. Throughout her life she recognizes her struggles applying proper English instead of the broken used in her home.

She became aware of how she spoke was when giving a lecture about her book The Joy Club and realized her mother who was in the audience did not understand what was being discussed. This was because she never used proper English in her home or talking to her mother. It is her belief utilizing proper English and broken English is essential in communication depending who you are talking to. The next time she noticed this about her English was when walking with her parents, she made the statement “not waste money that way”. This is due to the language barrier in her household that is used only by her family. Her mother was raised in China and spoke Mandarin her English always came across as broken to everyone outside the family, which made it hard for her to understand when someone spoke proper English.

Amy insured everyone that met her mother’s that even though her English seem “broken” it does not reflect her intelligence. Even though people placed this label on her mother of the way she spoke she rejected the idea that her mother English is “limited”. She highlights the fact that even her mother recognizes that her opportunities and interactions in life are limited by the English language. Amy Tan realizes that how you communicate within the family dynamic, especially for immigrant families plays a large role in in the growth of the child. It allowed her to acknowledge that perhaps her family’s language had an effect on the opportunities she was provided in her life. For instance in her experience, she notices that Asian students actually do better in math tests than in language tests, and she questions whether or not other Asian students are discouraged from writing or directed in the direction of math and science. Tan changed her major from pre-med to English and she decided to become a freelance writer even though her boss told her she couldn’t write. She eventually went on to write fiction , she celebrates the fact that she did not follow the expectations that people had of her because of her struggle with writing and language. With her mother as an influence Tan decided to write her stories for people like her, people with “broken” or “limited” English. In the essay , Mother Tongue, Amy Tan goes to great length to persuade the readers of her experiences being multicultural family that the effectiveness and the price an individual pays by insuring that their ideas and intents do not change due to the way they speak, whether they use “perfect” or “broken” English. Tan also clarifies to the readers that her “mother’s expressive command of English belies how much she actually understands”. She uses many examples to take readers into her life experiences to discover this truth. She utilizes the first person view throughout the essay and adds her firsthand knowledge of growing up with a multiple languages spoken in the home. This was done to validate of her argument and shine a light on the importance of this issue in her life as well as her culture.

The examples she uses is when she tells a story of her mother’s struggles with a stockbroker because of her “broken “ English, Tan quotes her mother’s words “Why he not send me check, already two weeks late. So mad he lie to me, losing me money”. Amy Tan did this to give the readers an idea on how this particular situation played out and how her mother’s English affected outcome. The authors writing is also very emotional and somewhat angry at throughout the essay , it makes her and her family very sympathetic figures. Tan’s specific concern is being shunned by both white-America and the Asian population. This also further her strengthen her views that puts her in an equally frustrating position from the perspective of Americans with the stereotypical views of Asians. Many people in college looked at her funny for being an English major instead of Math as a major. Individuals of Chinese decent are associated with math or science and that is because of the stereotyping that Asian receive. This is based on studies being conducted that a majority of Asians do in fact excel in mathematics and sciences.

Amy also observed that many of her instructors towards math and science as well and was even told by a former boss that writing was not biggest attribute and should focus more onto her account management skills. The author states that “perhaps they also have teachers who are steering them away from writing and into math and science, which is what happened to me”. The author utilized the nonfiction essay form to discuss how language played a major role in her life. This also allowed her to show the readers how her relationship with the English language and her mother has changed over the years. In her essay , Mother Tongue Amy Tan describes numerous incidences that helped shape her views as a writer. The uses of first persons account to describe her experiences with her mother and how her mother’s use of the English language influenced her upbringing, such as a story her mother once told her about a guest at her mother’s wedding “Du Yusong having business like fruit stand. Like off-the-street kind. He is Du like Du Zong – but not Tsung-ming Island people….That man want to ask Du Zong father take him in like become own family. Du Zong father wasn’t look down on him, but didn’t take seriously, until that man big like become a mafia. Now important person, very hard to inviting him. She may have chosen to focus on this type sentence structure because it gave the readers sense of awareness into her life and also to make it easier for them to understand the factors that shaped her style as a writer. In conclusion after reading Mother Tongue, it became very apparent that her mother played an important part in the author’s life. However, after further reading, I determined that she could have been addressing a specific group of people. She is also explaining her story to people who read her works, since so much of her literature seems to be influenced by how she views of the English language. Amy Tan goes to great lengths in the essay to give bits and pieces of how she overcame the perception that many people had of her, since she did not do as well with English-related schooling as she did with the Sciences, or Math.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Diaspora Criticism › Analysis of Amy Tan’s Stories

Analysis of Amy Tan’s Stories

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on June 24, 2020 • ( 1 )

Amy Tan’s (born February 19, 1952) voice is an important one among a group of “hyphenated Americans” (such as African Americans and Asian Americans) who describe the experiences of members of ethnic minority groups. Her short fiction is grounded in a Chinese tradition of “talk story” ( gong gu tsai ), a folk art form by which characters pass on values and teach important lessons through narrative. Other writers, such as Maxine Hong Kingston, employ a similar narrative strategy.

A central theme of Tan’s stories is the conflict faced by Chinese Americans who find themselves alienated both from their American milieu and from their Chinese parents and heritage. Other themes include storytelling, memory, and the complex relationships between mother and daughter, husband and wife, and sisters. By using narrators from two generations, Tan explores the relationships between past and present. Her stories juxtapose the points of view of characters (husband and wife, mother and daughter, sisters) who struggle with each other, misunderstand each other, and grow distant from each other. Like Tan, other ethnic writers such as Louise Erdrich use multiple voices to retell stories describing the evolution of a cultural history.

Tan’s stories derive from her own experience as a Chinese American and from stories of Chinese life her mother told her. They reflect her early conflicts with her strongly opinionated mother and her growing understanding and appreciation of her mother’s past and her strength in adapting to her new country. Daisy’s early life, about which Tan gradually learned, was difficult and dramatic. Daisy’s mother, Jingmei (Amy Tan’s maternal grandmother), was forced to become the concubine of a wealthy man after her husband’s death. Spurned by her family and treated cruelly by the man’s wives, she committed suicide. Her tragic life became the basis of Tan’s story “Magpies,” retold by An-mei Hsu in The Joy Luck Club. Daisy was raised by relatives and married to a brutal man. After her father’s death, Tan learned that her mother had been married in China and left behind three daughters. This story became part of The Joy Luck Club and The Kitchen God’s Wife.

Tan insists that, like all writers, she writes from her own experienceand is not representative of any ethnic group. She acknowledges her rich Chinese background and combines it with typically American themes of love, marriage, and freedom of choice. Her first-person style is also an American feature.

The Joy Luck Club

Although critics call it a novel, Tan wrote The Joy Luck Club as a collection of sixteen short stories told by the club members and their daughters. Each chapter is a complete unit, and five of them have been published separately in short-story anthologies. Other writers, such as the American authors Sherwood Anderson (Winesburg, Ohio) and Gloria Naylor (The Women of Brewster Place), and the Canadian Margaret Laurence (A Bird in the House), have also built linked story collections around themes or groups of characters.

The framework for The Joy Luck Club is formed by members of a mah-jongg club, immigrants from China, who tell stories of their lives in China and their families in the United States. The first and fourth sections are the mothers’ stories; the second and third are the daughters’ stories. Through this device of multiple narrators, the conflicts and struggles of the two generations are presented through the contrasting stories. The mothers wish their daughters to succeed in American terms (to have professional careers, wealth, and status), but they expect them to retain Chinese values (filial piety, cooking skills, family loyalty) as well. When the daughters become Americanized, they are embarrassed by their mothers’ old-fashioned ways, and their moth ers are disappointed at the daughters’ dismissal of tradition. Chasms of misunderstanding deepen between them.

Critical Analysis of Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club

Jing-mei (June) Woo forms a bridge between the generations; she tells her own stories in the daughters’ sections and attempts to take her mother’s part in the mothers’ sections. Additionally, her trip to China forms a bridge between her family’s past and present, and between China and America.

The first story, “The Joy Luck Club,” describes the founding of the club by Suyuan Woo to find comfort during the privations suffered in China during World War II. When the Japanese invaders approached, she fled, abandoning her twin daughters when she was too exhausted to travel any farther. She continued the Joy Luck Club in her new life in San Francisco, forming close friendships with three other women. After Suyuan’s death, her daughter Jing-mei, “June,” is invited to take her place. June’s uncertainty of how to behave there and her sketchy knowledge of her family history exemplify the tensions experienced by an American daughter of Chinese parents. The other women surprise June by revealing that news has finally arrived from the twin daughters Suyuan left in China. They present June with two plane tickets so that she and her father can visit her half-sisters and tell them her mother’s story. She is unsure of what to say, believing now that she really did not know her mother. The others are aghast, because in her they see the reflection of their daughters, who are also ignorant of their mothers’ stories, their past histories, their hopes and fears. They hasten to tell June what to praise about their mother: her kindness, intelligence, mindfulness of family, “the excellent dishes she cooked.” In the book’s concluding chapter, June recounts her trip to China.

Rules of the Game

One of the daughters’ stories, “Rules of the Game,” describes the ambivalent relationship of Lindo Jong and her six-year-old daughter. Waverly Place Jong (named after the street on which the family lives) learns from her mother’s “rules,” or codes of behavior, to succeed as a competitive chess player. Her mother teaches her to “bite back your tongue” and to learn to bend with the wind. These techniques help her persuade her mother to let her play in chess tournaments and then help her to win games and advance in rank. However, her proud mother embarrasses Waverly by showing her off to the local shopkeepers. The tensions between mother and daughter are like another kind of chess game, a give and take, where the two struggle for power. The two are playing by different rules, Lindo by Chinese rules of behavior and filial obedience, Waverly by American rules of selfexpression and independence.

Another daughter’s story, “Two Kinds,” is June’s story of her mother’s great expectations for her. Suyuan was certain that June could be anything she wanted to be; it was only a matter of discovering what it was. She decided that June would be a prodigy piano player, and outdo Waverly Jong, but June rebelled against her mother and never paid attention to her lessons. After a disastrous recital, she stops playing the piano, which becomes a sore point between mother and daughter. On her thirtieth birthday, the piano becomes a symbol of her reconciliation with her mother, when Suyuan offers it to her.

Best Quality

“Best Quality” is June’s story of a dinner party her mother gives. The old rivalries between June and Waverly continue, and Waverly’s daughter and American fiancé behave in ways that are impolite in Chinese eyes. After the dinner Suyuan gives her daughter a jade necklace she has worn in the hope that it will guide her to find her “life’s importance.”

A Pair of Tickets

This is the concluding story of The Joy Luck Club. It recounts Jing-mei (June)Woo’s trip to China to meet her half-sisters, thus fulfilling the wish of her mother and the Joy Luck mothers and bringing the story cycle to a close, completing the themes of the first story. June learns from her father how Suyuan’s twin daughters were found by an old school friend. He explains that her mother’s name means “long-cherished wish” and that her own name Jing-mei means “something pure, essential, the best quality.” When at last they meet the sisters, she acknowledges her Chinese lineage: “I also see what part of me is Chinese. It is so obvious. It is my family. It is in our blood.”

Major Works Novels: The Kitchen God’s Wife, 1991; The Hundred Secret Senses, 1995; The Bonesetter’s Daughter, 2001; Saving Fish from Drowning, 2005. Children’s literature: The Moon Lady, 1992; The Chinese Siamese Cat, 1994. Nonfiction: “The Language of Discretion,” 1990 (in The State of the Language, Christopher Ricks and Leonard Michaels, editors); The Opposite of Fate: A Book of Musings, 2003.

Bibliography Becerra, Cynthia S. “Two Kinds.” In Masterplots II: Short Story Series, edited by Charles E. May. Rev. ed. Vol. 8. Pasadena, Calif.: Salem Press, 2004. Bloom, Harold, ed. Amy Tan. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2000. Chua, C. L., and Ka Ying Vu. “Rules of the Game.” In Masterplots II: Short Story Series,edited by Charles E. May. Rev. ed. Vol. 6. Pasadena, Calif.: Salem Press, 2004. Cooperman, Jeannette Batz. The Broom Closet: Secret Meanings of Domesticity in Postfeminist Novels by Louise Erdrich, Mary Gordon, Toni Morrison, Marge Piercy, Jane Smiley, and Amy Tan. New York: Peter Lang, 1999. Ho, Wendy. In Her Mother’s House: The Politics of Asian American Mother-Daughter Writing. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press, 1999. Huh, Joonok. Interconnected Mothers and Daughters in Amy Tan’s ‘The Joy Luck Club.’ Tucson, Ariz.: Southwest Institute for Research on Women, 1992 .____________. Amy Tan: A Critical Companion. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1998. Pearlman, Mickey, and Katherine Usher Henderson. “Amy Tan.” Inter/View: Talks with America’s Writing Women. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990. Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. Amy Tan: A Literary Companion. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004. Tan, Amy. “Amy Tan.” Interview by Barbara Somogyi and David Stanton. Poets and Writers 19, no. 5 (September 1, 1991): 24-32.

Share this:

Categories: Diaspora Criticism , Short Story

Tags: American Literature , Amy Tan , Amy Tan's Storise , Analysis of Amy Tan’s Stories , Character Study of Amy Tan’s Stories , Criticism of Amy Tan’s Stories , Essays of Amy Tan’s Stories , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Notes of Amy Tan’s Stories , Plot of Amy Tan’s Stories , Simple Analysis of Amy Tan’s Stories , Study Guides of Amy Tan’s Stories , Summary of Amy Tan’s Stories , Synopsis of Amy Tan’s Stories , Themes of Amy Tan’s Stories

- The Antagonist - Toptutor4me

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Strong Cultural Identity Importance in Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks” Essay (Critical Writing)

Rhetorical techniques are used in every genre of literature to ignite the reader’s interest, address a particular problem and structure the text in a precise and appealing manner. In “Fish Cheeks”, Amy Tan describes a particular autobiographical moment in her life: a Christmas Eve celebration that her parents invited the minister’s family over, while she was in love with the minister’s son, Robert. The essay explores a thought-provoking theme of being ashamed of one’s own traditions and customs in the context of a current multicultural society.

The text, possessing quite a simple style of narrative, still has rhetorical techniques that illustrate the mindset the author was in at the time of the story. Tan uses a lot of analogies and descriptive language specifically to show the way her younger self viewed the situation, as well as irony to educate her audience about the absurdity of being ashamed of one’s culture.

The problem of cultural identity in the US has always been a pressing issue. In her essay, Tan does not gravitate towards moralizing lessons as to why one should act and think a certain way and should never do the other. She illustrates how the destructive mindset of a Chinese immigrant works on her own example, telling a story about her 14-year-old self. Through the eyes of his Chinese girl, the way the Chinese celebrate Christmas Eve is “shabby”, her Chinese relatives are “noisy” and lack “proper American manners” (Tan).

The context of the narrative is clearly defined by this girl’s frame of perception. The celebration is a such dreadful event for her because everything that her Chinese relatives might do can be judged or misunderstood by the American minister’s family. This conveys the feeling that the author wants the reader to understand the intense dissonance between who she actually is and who she fervently desires to seem.

Tan’s message is supported by her stylistic choices in the text. For instance, she purposefully uses unappetizing epithets for Chinese food items. To her, tofu is “stacked wedges of rubbery”, the cod is “slimy”, a plate of squid “resembling bicycle tires”, while the whole kitchen is “littered with appalling mounds of raw food” (Tan). The author also explicitly underlines the fact that her extended family behaves in an unmannerly way, with the culmination of her despair being at the end of the dinner, when her father, according to a “polite Chinese custom”, belched loudly. Here, the author addresses the concept of cultural misunderstanding – and how great the perceptions of one ethnic group may differ from the ones of the other.

Growing up a Chinese girl in the American society, she wants to blend in and perceives her differences as unwanted. The only moralizing phrase in the essay is the advice her mother gives young Amy Tan “your only shame is to have shame” (Tan). This is the apex of the story, the moment that signals the message Tan wants to communicate – how absurd it is to be ashamed of who you are.

The purpose Amy Tan chose for her essay is truly a noble one – she wishes to aid young readers in understanding and establishing their cultural identity, without spending years figuring it out experientially. She communicates with her audience in a playful manner, with the use of rhetorical techniques such as irony and hilarious analogies, to better illustrate her point. She intricately operates with rhetoric which results in her succeeding in her aim – there is a greater possibility for the reader to learn the lesson when it is provided in such a simple, but smart way.

Tan, Amy. “ Fish Cheeks ”. CommonLit . 2021. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, September 29). Strong Cultural Identity Importance in Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks”. https://ivypanda.com/essays/strong-cultural-identity-importance-in-amy-tans-fish-cheeks/

"Strong Cultural Identity Importance in Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks”." IvyPanda , 29 Sept. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/strong-cultural-identity-importance-in-amy-tans-fish-cheeks/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Strong Cultural Identity Importance in Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks”'. 29 September.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Strong Cultural Identity Importance in Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks”." September 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/strong-cultural-identity-importance-in-amy-tans-fish-cheeks/.

1. IvyPanda . "Strong Cultural Identity Importance in Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks”." September 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/strong-cultural-identity-importance-in-amy-tans-fish-cheeks/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Strong Cultural Identity Importance in Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks”." September 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/strong-cultural-identity-importance-in-amy-tans-fish-cheeks/.

- Amy Tan’s Fish Cheeks and Brent Staple’s Black Men and Public Spaces

- Breaking Oppression Barriers in Maya Angelou's “Champion of the World” and Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks”

- “Fish Cheeks” vs. “It’s Hard Enough Being Me”

- The Story "Two Kinds" by Amy Tan

- Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club Review

- The Gaps Showed in the Amy Tan’s "The Joy Luck Club"

- “Mother Tongue” Article by Amy Tan

- Cultural Acceptance in Amy Tan’s “A Pair of Tickets”

- Aspects of Tim O’Brien’s “Good Form”

- Cheek Dimples: Cosmetic Surgery

- “Know My Name: A Memoir” by Chanel Miller

- The Book "The Sound and the Fury" by William Faulkner

- Shevek’s Character in "The Dispossessed" Analysis

- White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide

- "Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening" by Frost

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Mother Tongue — “Mother Tongue” by Amy Tan

"Mother Tongue" by Amy Tan: a Reflection

- Categories: Amy Tan Mother Tongue

About this sample

Words: 931 |

Published: Jul 10, 2019

Words: 931 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

The essay explores Amy Tan's article "Mother Tongue," focusing on the author's intent and the themes presented in the piece. The central argument of the essay is that Amy Tan's goal in the article is to challenge the notion that individuals who do not speak "perfect" English are not intellectual. Tan's personal experiences growing up with her mother, who spoke a simplified form of English, serve as a backdrop for this argument.

The essay discusses how Tan effectively conveys her message by highlighting key points from the article. These points include the way Tan communicated with her mother, who was well-informed and engaged in activities like reading Forbes reports and conversing with her stockbroker, despite her non-standard English. Tan also explores her own evolving perception of her mother's language, ultimately recognizing its richness and clarity.

Furthermore, the essay emphasizes that Tan's ability to embrace various forms of English and incorporate them into her writing allowed her to reach a broader audience and even make her work more accessible to her mother.

Mother Tongue: response essay

Works cited:.

- Fisher, J. (2012). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House.

- Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The Story of Success. Back Bay Books.

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence. Bantam Books.

- Kaplan, R. M., & Kaplan, R. (2019). The Power of Positive Thinking. Penguin.

- Lambert, L. S. (2018). The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion: Freeing Yourself from Destructive Thoughts and Emotions. Guilford Press.

- Purcell, M. (2018). 5-minute Daily Meditations: Instant Wisdom, Clarity, and Calm. Rockridge Press.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. Free Press.

- Sinek, S. (2017). Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. Portfolio.

- Tolle, E. (2010). The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment. New World Library.

- Williams, M., & Penman, D. (2012). Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World. Rodale Books.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 466 words

2 pages / 759 words

6.5 pages / 3030 words

2 pages / 887 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Mother Tongue

In Amy Tan's essay, "Mother Tongue," she explores the importance of language and how it shapes our identity. Tan reflects on her experiences growing up as a Chinese-American and the challenges she faced due to her mother's [...]

Amy Tan's essay "Mother Tongue" explores the concept of linguistic dominance and its impact on personal identity and relationships. As a Chinese-American writer who has experienced the challenges of communicating in English as a [...]

Do you ever stop to think about the power and beauty of language? In her essay "Mother Tongue," Amy Tan explores the intricate relationship between language and identity, delving into the complexities of communication within [...]

Amy Tan's essay "Mother Tongue" explores the complexities of language and its impact on one's identity and relationships. Tan reflects on her experiences as a bilingual and bicultural individual, shedding light on the challenges [...]

A fact would not be an interesting one to people who feel demeaned as a result of their accents while communicating in English. In Amy Tan’s Mother Tongue, she argues that there is not a specific way to speak English as it [...]

Does everyone consider English as a single language? There are inferences that English is a single language, but in reality, people develop diverse versions of English as their mother tongue such that it is very uncommon to [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Member Interviews

- Science & Exploration

- Public Service

- Achiever Universe

- Summit Overview

- About The Academy

- Academy Patrons

- Delegate Alumni

- Directors & Our Team

- Golden Plate Awards Council

- Golden Plate Awardees

- Preparation

- Perseverance

- The American Dream

- Recommended Books

- Find My Role Model

All achievers

Bestselling novelist.

Download our free multi-touch iBook Creative Writing: Learning from the Masters — available on Apple Books

Creative Writing: Learning from the Masters provides readers with a window into the extraordinary world of writing fiction. This interactive iBook produced by the Academy of Achievement gives aspiring writers a unique look at how fiction is created by six admired and successful authors.

Listen to this achiever on What It Takes

What It Takes is an audio podcast produced by the American Academy of Achievement featuring intimate, revealing conversations with influential leaders in the diverse fields of endeavor: public service, science and exploration, sports, technology, business, arts and humanities, and justice.

I think that’s why I’m a storyteller. I take all these disparate events and connect them. I have to make them seem inevitable and yet surprising and plausible. That’s what I think life is like too. I have the luxury to do exactly what it is we all need time to do... think about the mystery of life.

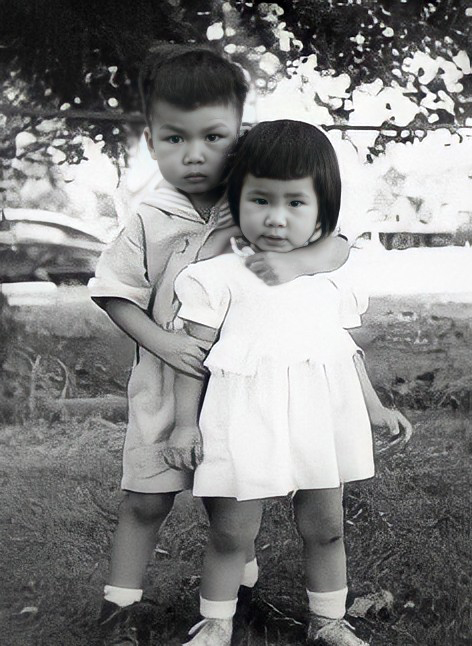

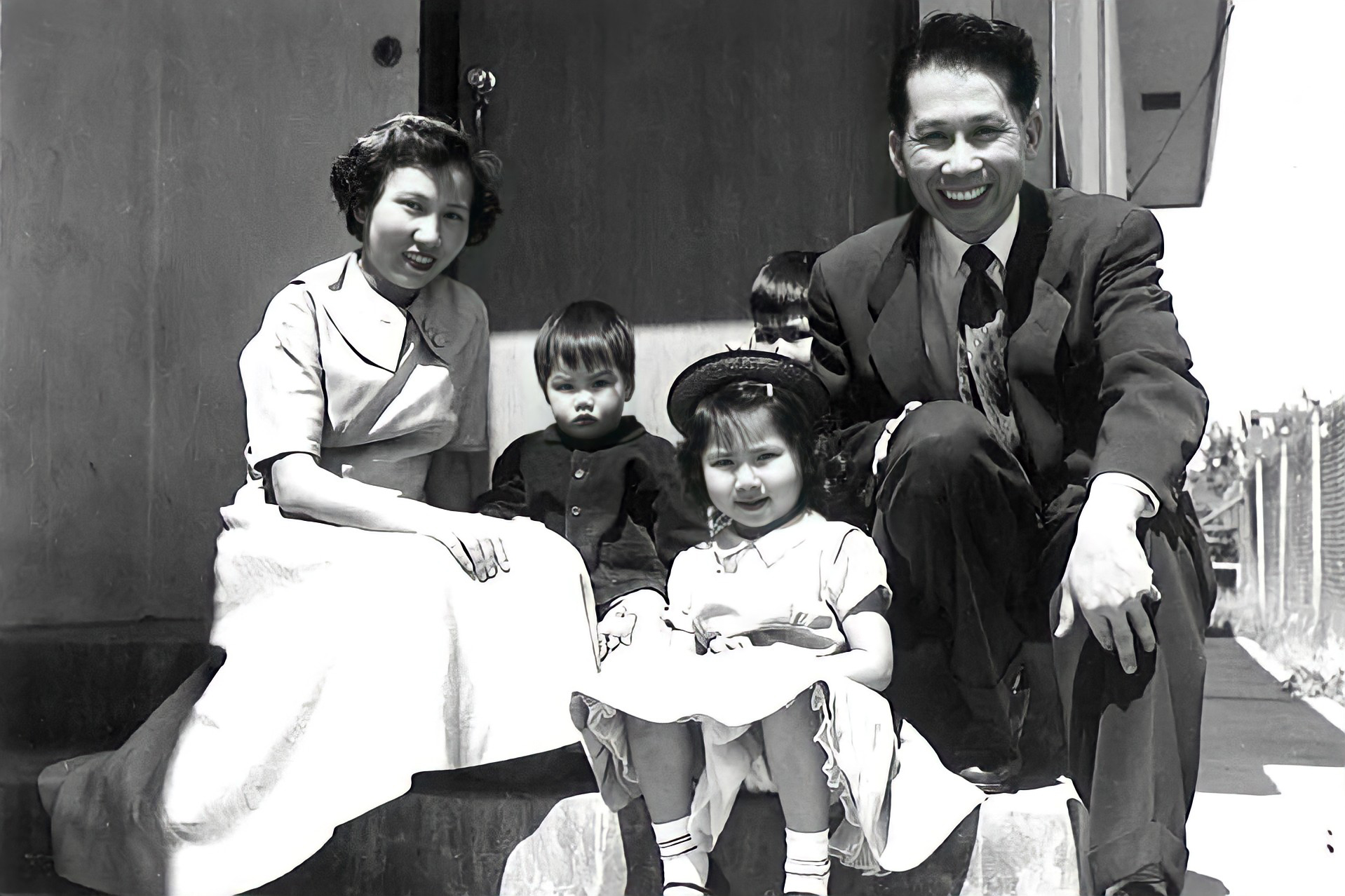

Amy Tan was born in Oakland, California. Her family lived in several communities in Northern California before settling in Santa Clara. Both of her parents were Chinese immigrants. Her father, John Tan, was an electrical engineer and Baptist minister who came to America to escape the turmoil of the Chinese Civil War. The harrowing early life of her mother, Daisy, inspired Amy Tan’s novel The Kitchen God’s Wife. In China, Daisy had divorced an abusive husband but lost custody of her three daughters. She was forced to leave them behind when she escaped on the last boat to leave Shanghai before the Communist takeover in 1949. Her marriage to John Tan produced three children, Amy and her two brothers. Tragedy struck the Tan family when Amy’s father and oldest brother both died of brain tumors within a year of each other. Mrs. Tan moved her surviving children to Switzerland, where Amy finished high school, but by this time mother and daughter were in constant conflict.

Mother and daughter did not speak for six months after Amy Tan left the Baptist college her mother had selected for her, to follow her boyfriend to San Jose City College.

Tan further defied her mother by abandoning the pre-med course her mother had urged, to pursue the study of English and linguistics. She received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in these fields at San Jose State University. In 1974, she and her boyfriend, Louis DeMattei, were married. They were later to settle in San Francisco.

DeMattei, an attorney, took up the practice of tax law, while Tan studied for a doctorate in linguistics, first at the University of California at Santa Cruz, later at Berkeley. By this time, she had developed an interest in the problems of the developmentally disabled. She left the doctoral program in 1976 and took a job as a language development consultant to the Alameda County Association for Retarded Citizens, and later directed a training project for developmentally disabled children.

With a partner, she started a business writing firm, providing speeches for the salesmen and executives of large corporations. After a dispute with her partner, who believed she should give up writing to concentrate on the management side of the business, she became a full-time freelance writer. Among her business works, written under non-Chinese-sounding pseudonyms, were a 26-chapter booklet called “Telecommunications and You,” produced for IBM.

Amy Tan prospered as a business writer. After a few years in business for herself, she had saved enough money to buy a house for her mother. She and her husband lived well on their double income, but the harder Tan worked at her business, the more dissatisfied she became. The work had become a compulsive habit, and she sought relief in creative efforts. She studied jazz piano, hoping to channel the musical training forced on her by her parents in childhood into a more personal expression. She also began to write fiction.

Her first story, “Endgame,” won her admission to the Squaw Valley writer’s workshop taught by novelist Oakley Hall. The story appeared in FM literary magazine, and was reprinted in Seventeen. A literary agent, Sandra Dijkstra, was impressed enough with Tan’s second story, “Waiting Between the Trees,” to take her on as a client. Dijkstra encouraged Tan to complete an entire volume of stories.

Just as she was embarking on this new career, Tan’s mother fell ill. Amy Tan promised herself that if her mother recovered, she would take her to China, to see the daughters who had been left behind almost 40 years before. Mrs. Tan regained her health, and mother and daughter departed for China in 1987. The trip was a revelation for Tan. It gave her a new perspective on her often-difficult relationship with her mother, and inspired her to complete the book of stories she had promised her agent. On the basis of the completed chapters, and a synopsis of the others, Dijkstra found a publisher for the book, now called The Joy Luck Club. With a $50,000 advance from G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Tan quit business writing and finished her book in a little more than four months.

Upon its publication in 1989, Tan’s book won enthusiastic reviews and spent eight months on The New York Times bestseller list. The paperback rights sold for $1.23 million. The book has been translated into 17 languages, including Chinese. Her subsequent novel, The Kitchen God’s Wife (1991), confirmed her reputation and enjoyed excellent sales. In the following years, Amy Tan published two books for children, The Moon Lady and The Sagwa , and two more novels: The Hundred Secret Senses (1995) and The Bonesetter’s Daughter (2001).

In 2003, she published The Opposite of Fate: A Book of Musings , an autobiography in which she disclosed her experience with Lyme disease, a chronic bacterial infection contracted from the bite of a common tick. Amy Tan’s case went undiagnosed for years before she received proper treatment, and she suffered intense physical pain, mental impairment and seizures. For years, Lyme disease made it impossible for Amy Tan to continue writing. With medication, she has been able to control the worst symptoms of her illness, and has resumed writing, but she also spends much of her energy raising awareness of Lyme disease, promoting its early detection and treatment, and advocating for the rights of Lyme disease patients.

With her illness under control, Amy Tan has completed two works of fiction. Her novel Saving Fish from Drowning appeared in 2005. In 2013, she published one of her most ambitious books to date, The Valley of Amazement , an epic saga told from the point of view of a part-American girl raised among the courtesans of Shanghai in the first years of the 20th century. Tan published a powerful memoir, Where the Past Begins , in 2017. The book recounts her difficult childhood and complex relationship with her mother, as well as her evolution as a writer and collaboration with her longtime editor Dan Halpern, in an intense exploration of the relationship between memory and creativity.

In 1988, Amy Tan was earning an excellent living writing speeches for business executives. She worked around the clock to meet the demands from her many high-priced clients, but she took no joy in the work, and felt frustrated and unfulfilled. In her 30s, she took up writing fiction. A year later her first book, a collection of interrelated stories called The Joy Luck Club was an international bestseller, and Amy Tan’s life was changed forever.

Her subsequent books, The Kitchen God’s Wife and The Hundred Secret Senses, have been bestsellers, and the film of The Joy Luck Club was an unprecedented success. At the height of her success, Amy Tan was stricken with Lyme Disease. Although the infection went untreated for many years, she has overcome the devastating symptoms of this chronic illness and has continued to write bestselling novels, including Saving Fish From Drowning and The Valley of Amazement .

Only 30 years ago, a list of well-known American authors would have included virtually no Asian-Americans. Today Amy Tan is one of America’s most popular novelists. Although they are primarily concerned with the lives and concerns of Asian-American women, her stories have found an enthusiastic audience among Americans of all backgrounds, and have been translated into 35 languages.

How did you come to write The Joy Luck Club?

Amy Tan: I wanted to write stories for myself. At first it was purely an aesthetic thing about craft. I just wanted to become good at the art of something. And writing was very private. I also thought of playing improvisational jazz and I did take lessons for a while. At first I tried to write fiction by making up things that were completely alien to my life. I wrote about a girl whose parents were educated, were professors at MIT. There was no Joy Luck Club, it was the country club. I tried to copy somebody’s style that I thought was very clever. I thought I was clever enough to write as well as these people, and I didn’t realize that there is something called originality and your own voice.

One day, after being told one of these stories didn’t work, I thought, “I’m just going to stop showing my work to people, and I’m just going to write a story. Make it fictional, but they’ll be Chinese-American.” What amazed me was: I wrote about a girl who plays chess, and her mother is both her worst adversary and her best ally. I didn’t play chess, so I figured that counted for fiction, but I made her Chinese-American, which made me a little uncomfortable. By the end of this story I was practically crying. Because I realized that — although it was fiction and none of that had ever happened to me in that story — it was the closest thing of describing my life. Of the feelings that I had, of these things that my mother had taught me that were inexplicable or had no name. This invisible force that she taught me, this rebellion that I had. And then feeling that I had lost some power, lost her approval and then lost what had made me special. It was a magic turning point for me. I realized that was the reason for writing fiction. Through that, this subversion of myself, of creating something that never happened, I came closer to the truth. So, to me, fiction became a process of discovering what was true, for me. Only for me.

I went to a writer’s workshop. I met a wonderful writer there named Molly Giles. She looked at my work and said, “Where’s the voice? Where’s the story? There’s so many things that are happening that are not working, but there’s a possible beginning. If I were you, I would start over again and take each one of these and make that your story. You don’t have one story here, you have 12 stories. 16 stories.” She was right because those 16 stories became The Joy Luck Club.

I was at a stage where that kind of criticism didn’t dishearten me at all. It made me so excited because she had said it in the most constructive way — not simply saying, “This isn’t working, this is bad, this is nothing.” She said, “Look at this. Here you have a voice, and it’s inconsistent with this voice, but it’s an interesting voice. So maybe you should think about this question, what is your voice?” That’s a question I still ask myself today as a writer.

I had an agent who, by luck, read my stuff in a little magazine and wanted to be my agent. Believed in me as a fiction writer before I ever believed in myself. In fact, I told her, when she wanted to be my agent. I said, “I’m not really a fiction writer. I don’t need an agent. But if I ever write anything else, maybe ten years from now, I’ll let you know.” She pursued me, and she kept saying, “You have to write more fiction.” I said, “I can’t pay you anything.” She said, “I’m by commission. You don’t have to pay anything until you sell anything.” I said, “Well fine. You want to be my agent and not make anything.” I thought, “Boy, is she dumb.” She hounded me until I wrote a couple more stories, and then she sold that as a collection called The Joy Luck Club.

You’ve spoken of another turning point. In 1987 you traveled with your mother to China, where you had never been. What did you learn from that trip that was so important to you?

Amy Tan: I took this trip to China as a way of fulfilling a promise. I thought my mother was going to die, and I had sworn to God and Buddha and whatever spirits are out there that I would do this if she lived. And by God the little mother pulled through, so I went to China.

I was nervous about it because it meant three weeks with my mother, and I had hardly spent more than a couple of hours alone with her in the last 20 years. So it was a chance for me to really see what was inside of me and my mother. Most importantly, I wanted to know about her past. I wanted to see where she had lived, I wanted to see the family members that had raised her, the daughters she had left behind. The daughters could have been me, or I could have been them.

And I did see all of those things, and even more. I discovered how American I was. I also discovered how Chinese I was by the kind of family habits and routines that were so familiar. I discovered a sense of finally belonging to a period of history, which I never felt with American history.

When you read about the Civil War, a lot of people, like my husband, can say my great-great-grandfather fought in that war. We have the gun and all that kind of stuff. I have a good imagination, but I could never imagine my ancestors having been in any of this history because my parents came to this country in 1949. So none of that history before then seemed relevant to me. It was wonderful going to a country where suddenly the landscape, the geography, the history was relevant. That was enormously important to me.

It doesn’t necessarily have to be that way for everybody, but for me it was extremely important because I had spent so long denying that side of me. In fact, one of the subjects I hated the most was history. I thought it was completely a waste of time. It had absolutely no relevance. Today, I love history. I find it is absolutely relevant to everything that is going on. It’s not just some philosophical babble of how things repeat themselves. You see the undercurrents of change and culture and that is history. It’s those behaviors that are important. History really is a record of behaviors and intentions and actions and consequences.

So, I think going to China was a turning point. I couldn’t have written The Joy Luck Club without having been there, without having felt that spiritual sense of geography.

Was it also a turning point in your relationship with your mother?

Amy Tan: Oh yes. For example…

I used to think that my mother got into arguments with people because they didn’t understand her English, because she was Chinese. And I saw in China that she got in arguments with Chinese people. She was just as difficult in China as she was in America. I had to laugh about that. There are so many things that I could laugh about and see that my sisters were the same way, that we had inherited things from my mother. But there were differences as well. And my sisters, who had grown up thinking that they had been denied this wonderful, loving, nurturing mother who would have understood everything and been sweet and kind and never would have criticized them. Well suddenly they were shocked to find this mother saying, “You didn’t cook this long enough,” or “This is too salty,” and “Why do you wear that? It makes you look terrible.” They were shocked too. It had nothing to do with being American. They were daughters, also wanting their mother’s approval, and didn’t understand why their mother was so critical. So I saw my mother in a different light. We all need to do that. You have to be displaced from what’s comfortable and routine, and then you get to see things with fresh eyes, with new eyes. The new eyes can be very useful in breaking habits of relationships, the old irritations, the patterns of avoidance. You start talking about things. You still get into fights but you learn to just pick what’s important and say, you know, it’s not so important really for me to win this one. Really, what my mother wants is for me to think that what she has to say is valuable. That’s all.

So I saw my mother in a different light. We all need to do that. You have to be displaced from what’s comfortable and routine, and then you get to see things with fresh eyes, with new eyes. The new eyes can be very useful in breaking habits of relationships, the old irritations, the patterns of avoidance. You start talking about things. You still get into fights but you learn to just pick what’s important and say, you know, it’s not so important really for me to win this one. Really, what my mother wants is for me to think that what she has to say is valuable. That’s all.

Then there was The Joy Luck Club and endless weeks on the bestseller list. Many people are smart and have talent and potential. Why do you think it is that you succeeded, when not everybody does?

Amy Tan: You know, I get asked that question a lot and I never know the answer. The answer keeps changing. Sometimes I think that it’s pure luck, I won the lottery. Sometimes I think it’s because I’m a baby-boomer and what I wrote about are very normal emotions and conflicts that many people have, so somehow it struck a universal chord.

I think that I was in the right time and the right place. I met the right people, who were passionate about my work and, thus, able to get it in front of people who would sell the book in bookstores, readers who would pass the word along to their mothers or daughters or friends. I think it’s all of that.

I also begin to think there are things in life that we don’t understand, that are a mystery. I give credit to something beyond me. I’m not sure what that is exactly, except I think it’s a very benevolent force.

A lot of bad things have happened in my life. I never believed the sort of pap that ministers would say. You know, “Bad things happen for certain reasons. God decided to take your brother at this time for a reason.” I thought, “Bullshit, why would somebody allow such pain to happen to anybody?” It’s so difficult. We don’t have words to explain why things happen, and you can’t couch them in terms like that and explain them at the moment that they happen. It’s only later that you see what the connections might have been and how it led to something.

I think that’s why I’m a storyteller. I take all these disparate events and I have to connect them. I have to make them seem inevitable and yet surprising and plausible. That’s what I think life is like, too. I have the luxury to do exactly what it is we all need time to do, and that is just think about the mystery of life.

Speaking now only of your writing career, what setbacks or detours have you had along the way and how have you dealt with them and learned from them? Self-doubts, fear of failure?

Amy Tan: I didn’t fear failure. I expected failure. I think I’ve always been somebody, since the deaths of my father and brother, who was afraid to hope. So, I was more prepared for failure and for rejection than success. The success took me by surprise and it frightened me. On the day that there was a publication party for my book, I spent the whole day crying. I was scared out of my mind that my life was changing, and it was out of my control, and I didn’t know why it was happening. I thought it would ruin things, because at that moment in my life I was fairly happy. I was getting along with my mother. My husband and I had been married for a long time, we were happy, we had our first house, we had great friends, we were doing well, we weren’t starving. We had a comfortable living, and I thought, “Things are going to get messed up here, and I have no control over this.” I could already see how people were treating me differently. That’s the scary thing. You know, when people say, “How has success changed you?” you have to say, “No. How have people changed toward you as the result of success?” And “How have you dealt with that change in how people have changed toward you?” That’s the most difficult thing.

So I went through a terrible period of feeling that I had lost my privacy, that I had lost a sense of who I was. I was scared by the way people measured everything by numbers: where I was on a list, or how many weeks, or how many books I had sold. By the time it came to the second book, I was so freaked out, I broke out in hives. I couldn’t sleep at night. I broke three teeth grinding my teeth. I had backaches. I had to go to physical therapy. I was a wreck!