Valentina Tereshkova

Who Was Valentina Tereshkova?

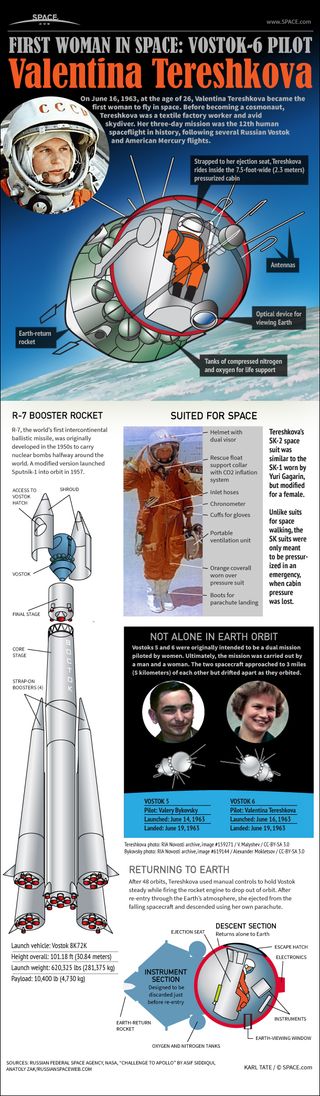

As a young woman, Valentina Tereshkova worked in a textile mill and parachuted as a hobby. She was chosen to be trained as a cosmonaut in the USSR’s space program. On June 13, 1963, she became the first woman to travel into space. In just under three days, she orbited the earth 48 times. After her space flight, she served in the Communist Party and represented the USSR at numerous international events.

The second of three children born to Vladimir Tereshkova and Elena Fyodorovna Tereshkova, Valentina Tereshkova was born on March 6, 1937 in Bolshoye Maslennikovo, a village in western Russia. When she was two years old, father was killed fighting in World War II. Her mother raised Valentina, her sister Ludmilla and her brother Vladimir, supporting the family by working in a textile mill.

Valentina began attending school when she was eight or 10 (accounts vary), and then started working in the textile mill in 1954. She continued her education through correspondence courses, and learned to parachute in her spare time. It was her parachuting experience that led to her being chosen, in 1962, for training as a cosmonaut in the Soviet space program. During the late 1950s and 1960s, the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union escalated for space travel supremacy. The competitiveness between the two nations for "one upping" achievements was fierce and the Soviets were determined to be the first to send a woman into space.

Cosmonaut Career

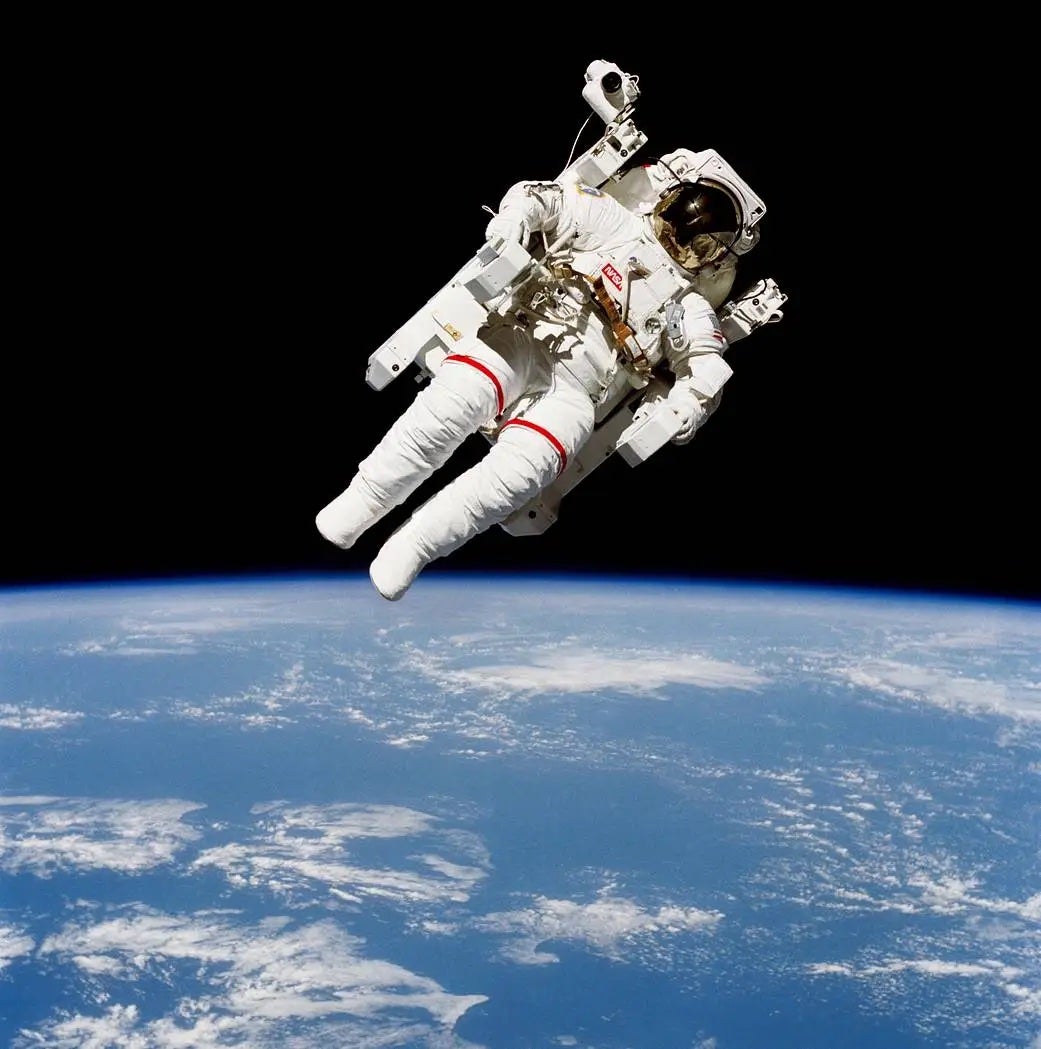

When she returned from her voyage—parachuting from her space craft to earth from 20,000 feet—Tereshkova was given the title Hero of the Soviet Union.

Despite the success of Tereshkova’s flight, it was 19 years before another woman (Svetlana Savitskaya, also from the USSR) traveled to space. Many accounts suggest that women cosmonauts did not receive the same treatment as their male counterparts. The first American woman to go to space was Sally Ride in 1983.

Life After Space Travel

On November 3, 1963, Tereshkova married Andrian Nikolayev, who was also a cosmonaut. On June 8, 1964, their daughter, Yelena Adrianovna Nikolayeva, was born. Tereshkova and Nikolayev divorced in 1980.

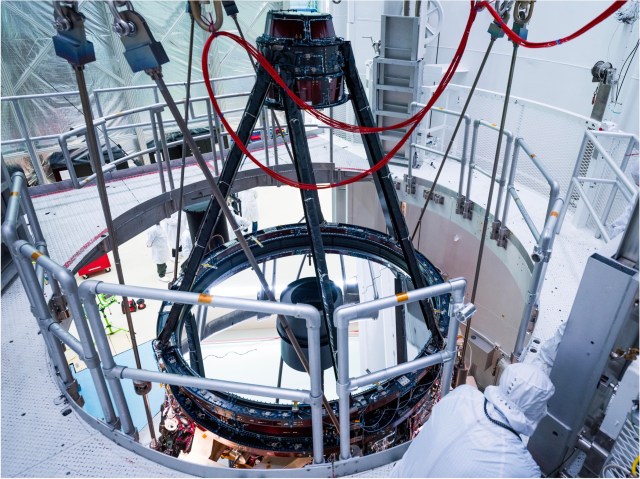

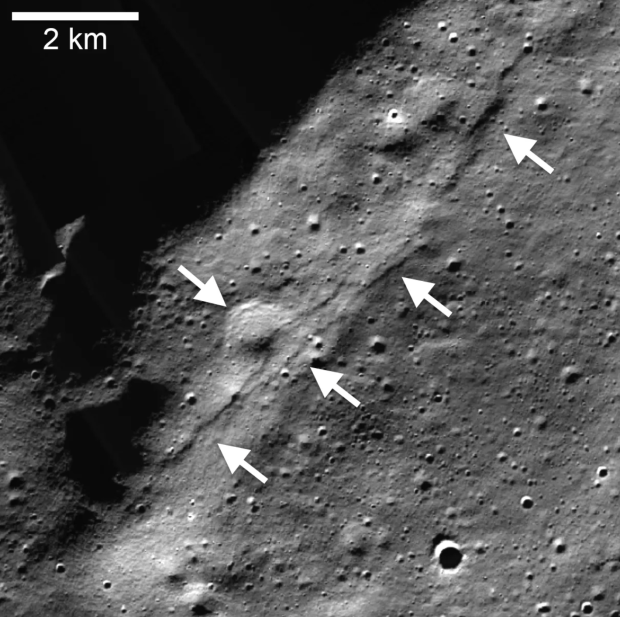

Tereshkova graduated with distinction from the Zhukovsky Military Air Academy in 1969. She became a prominent member of the Communist Party, and represented the USSR at numerous international events, including the United Nations conference for the International Women’s Year in 1975. She headed the Soviet Committee for Women from 1968-87, was pictured on postage stamps, and had a crater on the moon named after her.

In 2007, Vladimir Putin invited Tereshkova to celebrate her 70th birthday. At the time, she said, “If I had money, I would enjoy flying to Mars.” In 2015, her space craft, Vostov 6, was displayed as part of an exhibit at the Science Museum in London called “Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age.” Tereshkova attended the opening, and spoke lovingly about her spacecraft, calling it “my lovely one” and “my best and most beautiful friend – my best and most beautiful man.”

QUICK FACTS

- Birth Year: 1937

- Birth date: March 6, 1937

- Birth Country: Russia

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: In 1963, cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman to travel in space aboard Vostok 6.

- Science and Medicine

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Valentina Tereshkova Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/valentina-tereshkova

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 25, 2021

- Original Published Date: February 25, 2016

Mae Jemison

Neil Armstrong

This Is the Crew of the Artemis II Mission

10 Black Pioneers in Aviation Who Broke Barriers

Biography: You Need to Know: Joseph M. Acaba

Ellen Ochoa

Alan Shepard

James A. Lovell, Jr.

Michael Collins

Valentina Tereshkova: The First Woman in Space

First Woman in Space

- An Introduction to Astronomy

- Important Astronomers

- Solar System

- Stars, Planets, and Galaxies

- Space Exploration

- Weather & Climate

Space exploration is something that people routinely do today, without regard to their gender. However, there was a time more than half a century ago when access to space was considered a "man's job". Women weren't yet there, held back by requirements that they had to be test pilots with a certain amount of experience. In the U.S. 13 women went through astronaut training in the early 1960s, only to be kept out of the corps by that pilot requirement.

In the Soviet Union, the space agency actively sought a woman to fly, provided she could pass the training. And so it was that Valentina Tereshkova made her flight in the summer of 1963, a couple of years after the first Soviet and U.S. astronauts took their rides to space. She paved the way for other women to become astronauts, although the first American woman didn't fly to orbit until the 1980s.

Early Life and Interest in Flight

Valentina Tereshkova was born to a peasant family in the Yaroslavl region of the former USSR on March 6, 1937. Soon after starting work in a textile mill at the age of 18, she joined an amateur parachuting club. That stoked her interest in flight, and at the age of 24, she applied to become a cosmonaut. Just earlier that year, 1961, the Soviet space program began to consider sending women into space. The Soviets were looking for another "first" at which to beat the United States, among many space firsts they achieved during the era.

Overseen by Yuri Gagarin (the first man in space) the selection process for female cosmonauts began in mid-1961. Since there weren't many female pilots in the Soviet air force, women parachutists were considered as a possible field of candidates. Tereshkova, along with three other women parachutists and a female pilot, was selected to train as a cosmonaut in 1962. She began an intensive training program designed to help her withstand the rigors of launch and orbit.

From Jumping out of Planes to Spaceflight

Due to the Soviet penchant for secrecy, the entire program was kept quiet, so very few people knew about the effort. When she left for training, Tereshkova reportedly told her mother she was going to a training camp for an elite skydiving team. It wasn't until the flight was announced on the radio that her mother learned the truth of her daughter's achievement. The identities of the other women in the cosmonaut program were not revealed until the late 1980s. However, Valentina Tereshkova was the only one of the group to go into space at that point.

Making History

The historic first flight of a female cosmonaut was slated to concur with the second dual flight (a mission on which two craft would be in orbit at the same time, and ground control would maneuver them to within 5 km (3 miles) of each other). It was scheduled for June of the following year, which meant that Tereshkova had only about 15 months to get ready. Basic training for the women was very similar to that of the male cosmonauts. It included classroom study, parachute jumps, and time in an aerobatic jet. They were all commissioned as second lieutenants in the Soviet Air Force, which had control over the cosmonaut program at the time.

Vostok 6 Rockets into History

Valentina Tereshkova was chosen to fly aboard Vostok 6, scheduled for a June 16, 1963 launch date. Her training included at least two long simulations on the ground, of 6 days and 12 days duration. On June 14, 1963 cosmonaut Valeriy Bykovsky launched on Vostok 5 . Tereshkova and Vostok 6 launched two days later, flying with the call sign "Chaika" (Seagull). Flying two different orbits, the spacecraft came within roughly 5 km (3 miles) of each other, and the cosmonauts exchanged brief communications. Tereshkova followed the Vostok procedure of ejecting from the capsule some 6,000 meters (20,000 feet) above the ground and descending under a parachute. She landed near Karaganda, Kazakhstan, on June 19, 1963. Her flight lasted 48 orbits totaling 70 hours and 50 minutes in space. She spent more time in orbit than all the U.S. Mercury astronauts combined.

It's possible that Valentina may have trained for a Voskhod mission that was to include a spacewalk, but the flight never happened. The female cosmonaut program was disbanded in 1969 and wasn't until 1982 that the next woman flew in space. That was Soviet cosmonaut Svetlana Savitskaya, who went into space aboard a Soyuz flight. The U.S. did not send a woman into space until 1983, when Sally Ride, an astronaut and physicist , flew aboard the space shuttle Challenger.

Personal Life and Accolades

Tereshkova was married to fellow cosmonaut Andrian Nikolayev in November 1963. Rumors abounded at the time that the union was just for propaganda purposes, but those have never been proven. The two had a daughter, Yelena, who was born the following year, the first child of parents that had both been in space. The couple later divorced.

Valentina Tereshkova received the Order of Lenin and Hero of the Soviet Union awards for her historic flight. Later she served as the president of the Soviet Women's Committee and became a member of the Supreme Soviet, the USSR's national parliament, and the Presidium, a special panel within the Soviet government. In recent years, she has led a quiet life in Moscow.

Edited and updated by Carolyn Collins Petersen .

- Space First: From Space Dogs to a Tesla

- Women in Space - Timeline

- Biography of Yuri Gagarin, First Man in Space

- They Never Became Astronauts: The Story of the Mercury 13

- Who Was Yuri Gagarin?

- The History and Legacy of Project Mercury

- The Space Race of the 1960s

- Robert Henry Lawrence, Jr.

- Laika, the First Animal in Outer Space

- A Timeline of Women in Aviation

- The Life of Guion "Guy" Bluford: NASA Astronaut

- The History of Space Shuttle Challenger

- Christa McAuliffe: First NASA Teacher in Space Astronaut

- Did Politics Fuel the Space Race?

- Remembering NASA Astronaut Gus Grissom

First woman in space: Valentina

Valentina Tereshkova was born in Maslennikovo, near Yaroslavl, in Russia on 6 March 1937. Her father was a tractor driver and her mother worked in a textile factory. Interested in parachuting from a young age, Tereshkova began skydiving at a local flying club, making her first jump at the age of 22 in May 1959. At the time of her selection as a cosmonaut, she was working as a textile worker in a local factory.

After the first human spaceflight by Yuri Gagarin, the selection of female cosmonaut trainees was authorised by the Soviet government, with the aim of ensuring the first woman in space was a Soviet citizen.

On 16 February 1962, out of more than 400 applicants, five women were selected to join the cosmonaut corps: Tatyana Kuznetsova, Irina Solovyova, Zhanna Yorkina, Valentina Ponomaryova and Valentina Tereshkova. The group spent several months in training, which included weightless flights, isolation tests, centrifuge tests, 120 parachute jumps and pilot training in jet aircraft.

Four candidates passed the final examinations in November 1962, after which they were commissioned as lieutenants in the Soviet air force (meaning Tereshkova also became the first civilian to fly in space, since technically these were only honorary ranks).

Originally a joint mission was planned that would see two women launched on solo Vostok flights on consecutive days in March or April 1963. Tereshkova, Solovyova and Ponomaryova were the leading candidates. It was intended that Tereshkova would be launched first in Vostok 5, with Ponomaryova following her in Vostok 6.

However, this plan was changed in March 1963: Vostok 5 would carry a male cosmonaut, Valeri Bykovsky, flying the mission with a woman in Vostok 6 in June. The Russian space authorities nominated Tereshkova to make the joint flight.

Flight of the ‘Seagull’

After watching the launch of Vostok 5 at Baikonur Cosmodrome on 14 June, Tereshkova completed preparations for her own flight. On the morning of 16 June, Tereshkova and her backup Solovyova both dressed in spacesuits and were taken to the launch pad by bus. After completing checks of communication and life support systems, she was sealed inside her spacecraft.

After a two-hour countdown, Vostok 6 lifted off without fault and, within hours, she was in communication with Bykovsky in Vostok 5, marking the second time that two manned spacecraft were in space at the same time. With the radio call sign ‘Chaika’ (‘seagull’), Tereshkova had become the first woman in space. She was 26.

Tereshkova’s televised image was broadcast throughout the Soviet Union and she spoke to Khrushchev by radio. She maintained a flight log and performed various tests to collect data on her body’s reaction to spaceflight. Her photographs of Earth and the horizon were later used to identify aerosol layers within the atmosphere.

Her mission lasted just under three days (two days, 23 hours, and 12 minutes). With a single flight, she had logged more flight time than the all the US Mercury astronauts who had flown to that date combined. Both Tereshkova and Bykovsky were record-holders. Bykovsky had spent nearly five days in orbit and even today he retains the record for having spent the longest period of time in space alone.

Thank you for liking

You have already liked this page, you can only like it once!

Related Articles

Today’s women in space

European women in space

NASA: the Space Shuttle era

Related Links

Who were the first women in space? What were their stories?

First Woman in Space: Valentina Tereshkova

From June 16 to 19, 1963, Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova became the first woman to fly in space.

Tereshkova was born on March 6, 1937, in Bolshoye Maslennikovo. Tereshkova graduated at age 17. While working at a textile mill at the age of 18, she took correspondence courses from an industrial school and joined a club for parachutists, making over 150 jumps.

Shortly after the flight of cosmonaut Gherman Titov in September of 1961 she wrote a letter to the Soviet space program volunteering for the cosmonaut team. Unknown to her, Soviet space officials were considering the selection of a group of women parachutists.

In December 1961 Tereshkova was invited to Moscow for an interview and medical examination. The following March she reported with three other women to the Soviet Space Center at Star City. The women were subjected to the same centrifuge rides and zero-G flights as men. They were also commissioned as junior lieutenants in the Soviet Air Force and given fight instruction.

In May 1963, Tershkova and Tatyana Torchillova were chosen to train for the Vostok 6 flight. On June 16, 1963, she was launched into orbit aboard Vostok and made 45 revolutions around the earth in a 70-hour 50-minute space flight. Tereshkova orbited the earth once every 88 minutes by operating her spacecraft with manual controls. Tereshkova parachuted from the Vostok 6 after re-entering the earth's atmosphere and landed about 612 km (380 miles) northeast of Karaganda, Kazakhstan, in central Asia.

In the years following her flight, Tereshkova made many public appearances on behalf of the government and trips to other countries. Tereshkova went on to graduate from the Zhuykosky Air Force Engineering Academy in 1969 and earned a degree in Technical Science in 1976.

First American Woman in Space: Sally Ride

Twenty years after Tereshkova became the first woman to fly in space, Dr. Sally Ride became the first American woman to fly in space on June 18, 1983 as part of STS-7.

Ride was born in suburban Encino, California. As a teenager she took up tennis and within a few years was ranked eighteenth nationally. In 1968, she enrolled at Swarthmore College as a physics major, but she dropped out after three semesters to work on her tennis game full time. In 1970, Ride gave up tennis and entered Stanford University, where she took a double major in physics and English literature. Ride continued at Stanford for a PhD in physics, where her research focused on the absorption of X-rays by interstellar gas.

While at the University she saw an announcement that NASA was looking for young scientists to serve as mission specialists, and she immediately applied. She passed NASA's preliminary process and became one of the 208 finalists. Ride was flown to Johnson Space Center outside Houston for physical fitness tests, psychiatric evaluation, and personal interviews. Three months later, she was an astronaut and one of six women selected as astronaut candidates. She was part of Astronaut Group 8, which formed in 1978. (After approximately two years of training, the ascans—astronaut candidates—become astronauts.)

While learning to use a new space shuttle remote manipulative arm for a future mission, Ride acted as backup orbit Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) for STS-2 and prime orbit CAPCOM for STS-3. She was named a mission specialist on the seventh flight of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1983 and became the first American Women to fly in space. She flew on a second mission, STS-41G, in 1984.

Twice she served on the commissions appointed to investigate the causes and recommend remedies after the tragic losses of the Challenger and Columbia crews.

She left NASA in 1987 to pursue an academic career.

Tereshkova and Ride paved the way for the women who would follow them in space, including ...

Tamara jernigan .

Tamara Jernigan was one of the thirteen astronauts selected by NASA in June 1985. She flew on five Space Shuttle missions, logging over 1512 hours in space.

Jernigan was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, but grew up in southern California and graduated from high school in Santa Fe Springs in 1977. She attended Stanford University receiving a B.S. in physics (with honors) in 1981 and an M.S. in engineering science in 1983. She also earned an M.S. in astronomy from the University of California at Berkeley in 1985.

While continuing her studies at Stanford and Berkeley from June 1981 until her selection as an astronaut, she worked for the NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California. Her field of research was astrophysics and she earned and PhD from Rice in space physics in 1988.

In addition to her time in space, on Earth Jernigan served as Deputy Chief of the Astronaut Office and Deputy for the Space Station program, before retiring from NASA in 2001.

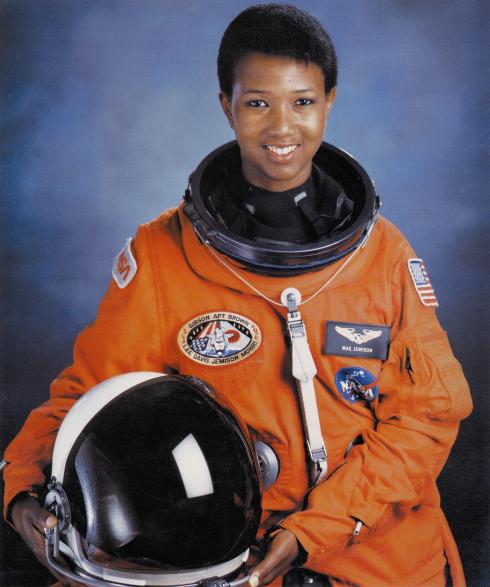

Mae Jemison

On September 12, 1992, Dr. Mae Jemison made history as the first African American woman to fly in space.

Jemison grew up in a Chicago, where her mother was a teacher and her father a maintenance supervisor. She attended the Chicago Public School System and earned honors in math and science. Jemison attended Stanford University at the age of 16 and earned her bachelor’s degree in Chemical Engineering and African American Studies, graduating in 1977. She went on to earn a medical degree from Cornell University in 1981 and served two years in the Peace Corps in West Africa as a staff physician.

Inspired by Sally Ride and Guy Bluford, Jemison left her private medical practice in Los Angeles and applied to become an astronaut candidate. In 1987, she was one of 15 ascans (astronaut candidates) chosen from a pool of 2,000 applicants. She completed the intensive training, and was assigned to STS-47, a Spacelab Life Sciences mission. On this eight-day flight Jemison served as a mission specialist and carried out experiments.

After leaving NASA, Dr. Jemison went on to teach, formed a company that researches advanced technologies, and is a public speaker.

This content was migrated from an earlier online exhibit, Women in Aviation and Space History , which shared the stories of the women featured in the Museum in early 2000s.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

Valentina Tereshkova: First woman in space

In 1963 Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman to journey to space orbiting Earth in the Vostok 6 space capsule.

Early life and joining the Soviet Space Program

The vostok 6 mission, after space: personal life and politics, valentina tereshkova faqs, famous quotes, additional resources, bibliography.

Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman to travel to space on June 16, 1963, when she orbited Earth as part of the Vostok 6 mission.

Tereshkova spent almost three days in space during her solo mission.

She remains the youngest woman to fly to space, the only female astronaut or cosmonaut to make a solo space journey, and the first civilian to journey to space.

Following her one and only space mission, Tereshkova has received a number of prestigious medals and has held many political positions, according to the Royal Museum of Greenwich . She has also toured the world as an advocate for Soviet science.

Related: 20 trailblazing women in astronomy and astrophysics

Valentina Tereshkova was born Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova to a peasant family in Maslennikovo, Russia, on March 6, 1937, according to History.com. Her father was a tractor driver, while her mother worked in a textile factory, the European Space Agency (ESA) says. During her early years, She received little in the way of formal education, and she went to work in a textile factory at just 18. Her father was killed in World War II.

Tereshkova's life changed course when she was 22 and made her first parachute jump with a local aviation club, the Yaroslavl Air Sports Club. She would go on to make over 150 jumps, according to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum . Her passion for skydiving brought her to the attention of the Soviet space program.

In April 1961, the program launched Yuri Gagarin , the first human in space, and Soviet Chief Designer Sergey Korolyov was keen to follow this by flying the first woman to space. According to NASA , in 1962, a Soviet space delegation visited the U.S. and came away with the impression that the country was in the process of selecting female astronauts and that a woman from America would journey to space very soon.

Up until this point, the astronauts and cosmonauts selected by the U.S. and by the Soviet Union had been picked from pools of military jet pilots, but according to NASA in the 1950s and early 1960s, these were exclusively male. On 16 February 1962 , five women were selected from 400 applicants to join the cosmonaut corps: Tatyana Kuznetsova, Irina Solovyova, Zhanna Yorkina, Valentina Ponomaryova, and Valentina Tereshkova. The group then spent several months training for space flight, including exposure to near weightlessness , isolation tests, and centrifugal testing. They also underwent pilot training in jet aircraft and made 120 parachute jumps, according to ESA.

Four of the candidates passed examinations in Nov. 1962 and were commissioned as lieutenants in the Soviet Air Force. This was just an honorary rank which means Tereshkova was a civilian when she journeyed to space.

At the time, cosmonauts had to parachute from their capsules seconds before they hit the ground on returning to Earth . This was considered one of the most challenging aspects of the Vostok series of missions. It was believed that Tereshkova's experience skydiving would be favorable for this element of the mission. NASA suggests that the other potential female cosmonauts were more technically qualified than Tereshkova, but she better fit the image of a Soviet proletariat and thus made a better political candidate. The space race , was, after all, a political game, with much of the Soviet Union's reason for sending a woman to space rooted in in the desire to do this before the U.S. just had the Soviets had done with Gargarin.

The Soviet Union initially intended to launch two woman cosmonauts into space in late 1962, but the missions were delayed. In March 1963, it was decided that male cosmonaut, Valeri Bykovsky would fly Vostok 5, a separate spacecraft but part of the same dual flight mission as the Vostok 6 capsule, which would be crewed by Tereshkova. Her radio call sign on the mission would be 'Chaika' or 'seagull.'

Vostok 5 and Bykovsky launched ahead of Vostok 6 on June 14, 1963, with Tereshkova watching on as she made final preparations for the launch of Vostok 6. Vostok 6 would blast off two days later on June 16, 1963, from Baikonur Cosmodrome.

Vostok 6 was guided by an automatic control system, so Tereshkova never actually took control of the craft during the flight. Though Vostok 5 and 6 had different orbits, they came within around 3 miles of each other during their respective flights. This allowed Tereshkova and Bykovsky to communicate briefly with each other before they drifted apart again.

During the flight of Vostok 6 , Tereshkova would also communicate with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, by radio, and her image was televised and broadcast across the Soviet Union. Tereshkova kept detailed logs of the mission and collected data regarding her body's reaction to spaceflight. In addition to this, the first female cosmonaut captured images of Earth, some of which would later be used to identify aerosol layers in our planet's atmosphere.

The Vostok 6 mission lasted 71 hours and 12 minutes, just 48 minutes short of three days. At the time, that was longer than the combined flight time of every U.S. Mercury astronaut. During those three days in space, Tereshkova made 48 orbits of Earth.

On June 19, 1963, Vostok 6 re-entered Earth's atmosphere , and Tereshkova ejected at an altitude of 20,000 feet and parachuted safely back to Earth. Vostok 5 would safely return to Earth just a few hours later.

Tereshkova never returned to space . The female cosmonaut group was disbanded in Oct. 1969, and it would take the Soviet Union another 19 years to send a female cosmonaut to space. In 1982, Svet lana Savitskaya became the second Russian woman in space.

Following her return to Earth, Tereshkova was awarded the Order of Lenin and the Hero of the Soviet Union awards. In Nov. 1963, she married fellow cosmonaut Andrian Nikolayev, the pair had a daughter in 1964.

Together Tereshkova and Nikolayev made various trips abroad to promote goodwill and Soviet science. They separated in 1979, but their divorce was only formalized in 1982 as it required the personal permission of Soviet Premier Brezhnev.

During reviews to return to space in 1978, Tereshkova met a military medical physician called Yuliy Shaposhnikov. Following her separation from Nikolayev, Tereshkova, and Shaposhnikov lived together for 20 years until his death in 1999.

Before the fall of the Soviet Union , Tereshkova was a prominent member of the Communist Party and represented the Soviet government at a number of meetings of international women's organizations, including acting as Soviet representative to the UN Conference for the International Women's Year in Mexico City in 1975. She would be recognized internationally with the United Nations Gold Medal of Peace, the Simba International Women's Movement Award, and the Joliot-Curie Gold Medal.

Tereshkova became a member of the World Peace Council in 1966. She served as a member of the Yaroslavl Supreme Soviet in 1967 and as a member of the council of the Union of the Supreme Soviet from 1966 to 1970 and then again from 1970 to 1974 when Tereshkova was elected to the presidium of the Supreme Soviet. In 1977 she earned a doctorate in aeronautical engineering.

During the 1980s, Tereshkova acted as Deputy to the Supreme Soviet and was Vice President of the International Women's Federation, as well as holding a number of other international positions. Tereshkova remained active in politics after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Her last political position to date was as Deputy Chair for the Committee for International Affairs in 2021.

How old was Valentina Tereshkova when she went to space?

Tereshkova was just 26 when she flew into space. She remains the youngest woman to make such a journey.

What are three interesting facts about Valentina Tereshkova?

1. Tereshkova married fellow cosmonaut and Vostok 3 crew member Andriyan Nikolayev in November 1963.

2. The daughter of Tereshkova and Nikolayev, Yelena, was born in June 1964 and was the firstborn to two parents who had journeyed to space.

3. Even at 86 years old, Tereshkova wants to be the first woman to travel to Mars , even if this is a one-way trip, according to NASA .

What happened to Valentina Tereshkova after the mission to space?

After her journey to space and before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Tereshkova was an official head of State and has held several political positions since, including Deputy Chair for the Committee for International Affairs in Russia. She was elected as a member of the World Peace Council in 1966.

"A bird cannot fly with one wing only. Human spaceflight cannot develop any further without the active participation of women."

"If women can be railroad workers in Russia, why can't they fly in space?"

"Once you've been in space, you appreciate how small and fragile the Earth is."

"Anyone who has spent any time in space will love it for the rest of their lives. I achieved my childhood dream of the sky."

"They forbade me from flying, despite all my protests and arguments. After being once in space, I was keen to go back there. But it didn't happen."

Read more about the Vostok 6 spacecraft that carried Tereshkova to space in these NASA resources . The often strange story of the Soviet Space Program is told here in this YouTube video . The first U.S. woman to make it to space was Sally Ride. You can read more about her and her mission courtesy of NASA .

Valentina Tereshkova and Sally Ride - Women Space Pioneers, NASA, [Accessed 06/10/23], [ https://www.nasa.gov/mediacast/valentina-tereshkova-and-sally-ride-women-space-pioneers ]

Who was the first woman in space? Royal Observatory Greenwich, [Accessed 06/10/23], [ https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/who-was-first-woman-space ]

First woman in space: Valentina, ESA [Accessed 06/10/23], [ https://www.esa.int/About_Us/ESA_history/50_years_of_humans_in_space/First_woman_in_space_Valentina ]

Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova becomes the first woman in space, History. Com. [Accessed 06/10/23], [ https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-woman-in-space ]

Valentina Tereshkova, Britannica, [Accessed 06/10/23], [ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Valentina-Tereshkova ]

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (photo, video)

Switzerland signs Artemis Accords to join NASA in moon exploration

Sweden becomes 38th country to sign NASA's Artemis Accords for moon exploration

Most Popular

- 2 Boom's XB-1 test plane gets FAA green light for supersonic flight

- 3 Saturn's 'Death Star' moon Mimas may have gotten huge buried ocean from ringed planet's powerful pull

- 4 Mysterious dark matter may leave clues in 'strings of pearls' trailing our galaxy

- 5 James Webb Space Telescope's 'shocking' discovery may hint at hidden exomoon around 'failed star'

Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

NASA’s Fermi Mission Sees No Gamma Rays from Nearby Supernova

The Ocean Touches Everything: Celebrate Earth Day with NASA

The April 8 Total Solar Eclipse: Through the Eyes of NASA

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Astronauts Home

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Events

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

Sols 4159-4160: A Fully Loaded First Sol

NASA’s Juno Gives Aerial Views of Mountain, Lava Lake on Io

Climate Change Research

NASA Open Science Initiative Expands OpenET Across Amazon Basin

NASA Motion Sickness Study Volunteers Needed!

NASA Selects New Crew for Next Simulated Mars Journey

AI for Earth: How NASA’s Artificial Intelligence and Open Science Efforts Combat Climate Change

Tech Today: Taking Earth’s Pulse with NASA Satellites

Hubble Goes Hunting for Small Main Belt Asteroids

NASA’s TESS Returns to Science Operations

Astronauts To Patch Up NASA’s NICER Telescope

NASA’s Roman Space Telescope’s ‘Eyes’ Pass First Vision Test

NASA’s Near Space Network Enables PACE Climate Mission to ‘Phone Home’

NASA Photographer Honored for Thrilling Inverted In-Flight Image

NASA Langley Team to Study Weather During Eclipse Using Uncrewed Vehicles

ARMD Solicitations

Amendment 10: B.9 Heliophysics Low-Cost Access to Space Final Text and Proposal Due Date.

Earth Day 2024: Posters and Virtual Backgrounds

NASA Names Finalists of the Power to Explore Challenge

NASA Partnerships Bring 2024 Total Solar Eclipse to Everyone

NASA Receives 13 Nominations for the 28th Annual Webby Awards

A Solar Neighborhood Census, Thanks to NASA Citizen Science

60 years ago today, Valentina Tereshkova launched into space

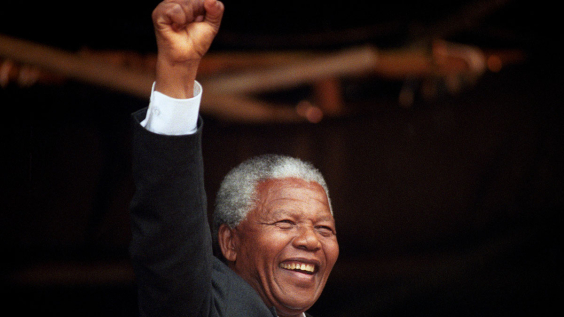

On a drab Sunday in Moscow in November 1963, a dark-suited man stood beside his veiled bride, whose bashful smile betrayed the merest hint of nerves. Despite the extraordinarily lavish surroundings of the capital’s Wedding Palace, it might have been any normal wedding but for one thing: Both groom and bride were cosmonauts, members of Russia’s elite spacefaring fraternity .

Two years earlier, that bride, Valentina Tereshkova, had been a factory seamstress and amateur parachutist with more than 100 jumps to her name when she’d volunteered for the cosmonaut program. Now, the 26-year-old, whom TIME magazine dubbed “a tough-looking Ingrid Bergman,” was among the most famous women in the world, an accolade she had earned just months ago by becoming the first female to leave the planet.

Sixty years on from her pioneering Vostok 6 mission, more than 70 women from around the globe have followed in Tereshkova’s footsteps, crossing that ethereal boundary between ground and space. Some have commanded space missions, helmed space stations, made spacewalks, spent more than a cumulative year of their lives in orbit, and even flown with a prosthesis. And women from Britain, Iran, and South Korea have become their countries’ first national astronauts, ahead of male counterparts.

Humble beginnings

Born in the tiny Russian hamlet of Bolshoye Maslennikovo, 160 miles (250 kilometers) northeast of Moscow, Tereshkova scarcely knew her father. A tractor driver prior to his service, he died in the Finnish Winter War when she was two years old. Her mother single-handedly raised three children while also laboring in the Krasny Perekop textile mill.

Tereshkova did not begin formal schooling until nearly age 10 and left at the age of 16, finishing her education via correspondence courses. The young girl worked making coats, apprenticed in a tire factory, then joined her mother and sisters at the loom. An interest in aviation eventually drew Tereshkova to an air sports club, where she made her first parachute jump at age 22.

In 1961, she applied to Russia’s secretive space program, just as officials were considering flying a woman in space as the obvious next step after Yuri Gagarin had become the first man in space in April that year. Early in 1962, five female finalists — Tatiana Kuznetsova, Valentina Ponomaryova, Irina Solovyova, Zhanna Yorkina, and Tereshkova — arrived at the cosmonauts’ training facility on Moscow’s forested outskirts to learn the rudiments of space travel. All were seasoned parachutists. This was a necessary prerequisite, as during the descent back to Earth, cosmonauts ejected from their Vostok capsules at an altitude of 4 miles (7 km) and landed beneath a parachute canopy.

Tereshkova was not top of the crop in technical preparedness or skill. Unlike NASA’s steely-eyed astronauts, she was no fighter ace or test pilot or intellectual. Indeed, the best praise bestowed by the cosmonauts’ commander, stone-faced General Nikolai Kamanin, was that she was “suitably feminine.” But her humble origins and gushing support for Russia’s ruling regime made her an ideal pawn for Premier Nikita Khrushchev, for whom space exploration and Soviet propaganda were dual faces of the same coin. He desired to promulgate the fiction that under Soviet socialism anyone could go into space. In a high-stakes, high-risk environment, it was a huge gamble.

The original mission plan envisaged either one woman flying for three to four days or two women launching in separate Vostok capsules. But this changed in March 1963. Instead, male cosmonaut Valeri Bykovsky would attempt a record-breaking weeklong flight on Vostok 5, with Tereshkova launching on Vostok 6 partway into his mission for few-day-long mission of her own.

Shortly after Bykovsky’s June 14th launch, his rocket underperformed and limited his mission from eight to five days. Nonetheless, it still ensured a world record at the time. In Moscow, Khrushchev was hosting Harold Wilson, leader of Britain’s Labour Party. When Wilson asked how many cosmonauts Khrushchev had in space this time, the premier could not help but gloat: “Only one… so far!”

Tereshkova’s Vostok 6 mission launched at 12:29 P.M. Moscow Time on June 16th. The rocket sent her into an orbital configuration that caused her spacecraft and Bykovsky’s to naturally pass within 3 miles (5 km) of each other twice daily. Three hours after liftoff, Tereshkova heard Bykovsky radioing her callsign, Seagull, and the pair were soon in regular voice contact. At one point, Bykovsky quipped that Tereshkova was “singing songs for me.”

Her three-day mission proved a political triumph for Khrushchev, surpassing all of NASA’s Project Mercury astronauts’ time in space combined. She photographed terrestrial cloud cover and landmasses beneath her flight path and was astounded by the “light blue, beautiful band” of the horizon over the poles.

But rumor swirled that Tereshkova did not adapt well to the strange weightless environment, appearing tired and weak in televised images from space. She suffered motion sickness, consumed barely half of her food, and grumbled about a lack of provisions to clean her face or teeth. She found the provided bite-sized chunks of bread dry and tasteless, and despite Tereshkova’s penchant for Vostok’s fruit juices and cutlet pieces, she began craving Russian black bread, potatoes, and onions as her mission neared its end.

That end came June 19th, after 70 hours and 48 orbits. The capsule’s descent was commanded automatically. After ejecting, Tereshkova mistakenly opened her helmet visor and was struck by a small piece of falling metal; the glancing blow left a nasty cut on her face. Barely missing a lake in the prevailing wind, she landed safely and was welcomed home by a clutch of kindly — though somewhat perplexed — locals, who offered her fermented milk, cheese, flatcakes, and bread.

A complicated legacy

Following Vostok 6’s success, Khrushchev crowed that Russia offered its women a far better lot than the capitalist West: Under Soviet socialism, he said, women could prosper and reach the stars . But the propagandist reality of Tereshkova’s flight was laid bare when no more Russian women entered space for another two decades. Even today, the total number of female cosmonauts can be counted on two hands, accounting for just 8 percent of all women launched into space to date.

Like Gagarin before her, who logged the shortest orbital mission by any male spacefarer, Tereshkova’s time in space is also the shortest of any woman’s. Neither flew again, as Gagarin was killed in an aircraft crash before he could complete a second mission. Tereshkova earned a doctorate in aerospace engineering and became active in politics. Although she was sanctioned by the U.S. in 2022 for her support of Vladimir Putin’s attempted annexation of Ukraine, Valentina Tereshkova’s spaceflight remains a shining example of the triumph of the human spirit over fierce adversity.

An updated list of space missions: Current and upcoming voyages

NASA bids farewell to the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter with new photos

NASA is taking astronaut applications. Here’s how to apply

It’s hard to grow food in space. These sensors can help.

Remembering Tom Stafford, the Apollo commander who did his part to thaw the Cold War

The upgrades to spacesuits that need to be made sooner rather than later

Isolation and annoying co-workers: Solving the stress of a trip to Mars

Studying lake deposits could give scientists insight into ancient traces of life on Mars

Evidence shows the Moon’s south pole is probably not the best place to land

Home → Features → History and Humanities → People

The First Woman in Space: The Story of Valentina Tereshkova

From humble beginnings to stellar heights.

Today, we still lament about the discrepant gender gap in STEM fields ( science , technology , engineering , and mathematics ) but things were a lot worse a century ago . Only a select few women got to be scientists in the ’50s and early ’60s — at least compared to the number of men who went on to earn a PhD — and this was during a time when things started to drift towards more liberal ground.

The USSR, however, didn’t seem to share the same gender bias in science as other countries, possibly because the Marxist doctrine upon which the regime was based took granting equal rights to both men and women very seriously, including their place in society. In 1964, some 40% of engineering graduates in the USSR were female s c ompared to under 5% in the US. By the mid-1980s, 58% of Russian engineers were women.

Women of science in Soviet Russia

Roshanna Sylvester, a writer at Russian History Blog, has some thoughts as to why Soviet Russia might have succeeded where the United States failed — and is still failing, for that matter:

Analysis of pedagogical journals suggests that girls’ quest for advancement in the 1960s was aided by the USSR’s standard school curriculum, which privileged the study of math and the hard sciences. There are also hints that girls benefited from generalized efforts by science and math educators to identify and mentor talented students as well as to improve the overall quality of instruction in those fields. As far as influences beyond the school room, sociological studies (particularly those conducted by Shubkin’s group in Novosibirsk) offer support for the notion that parents played key roles in shaping daughters’ aspirations. But those results also suggest that girls’ ideas about occupational prestige both reflected contemporary stereotypes about ‘women’s work’ and offered up challenges to male domination in science and technology fields.

This is a valid point. Even in the 1960s, long after the war, there were millions of Russians that lived like they had for centuries : through subsistence farming. Science and a job in science, either as a doctor, engineer or electrician, offered a way out and promised a place for the “new man” in the “new world”. As such , many Russians of humble origins, including women, sought to study hard and win a place. One of these women who came out of the Russian syste m w as Valentina Tereshkova. The daughter of a tractor driver and a textile plant worker in the Yaroslavl Region of Russia, Tereshkova left school when she was 17 to work as a textile factory assembly worker, as her mother had. However, she still insisted on earning her education and opted to study by correspondence. She was als o a keen amateur skydiver through the DOSAAF Aviation Club in Yaroslavl and made her first jump in May 1959 at age 22. Two years later in April 1961, the Soviet Union launched Vostok 1, aboard which was Yuri Gagarin: the first man in space.

The first woman in space

The following year, in 1962, the Soviets launched a program for the new Vostok where they recruited 50 people to serve as cosmonauts, including five women. Of these five women, one would be selected as the first women in space. The prime candidate need not be a pilot, but since upon re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere the pilot of the Vostok spacecraft would be ejected to make a landing by parachute , skydiving experience w as a must. Thanks to her jumps, Tereshkova — a woman with little formal education — was selected as one of the five women, all of whom were much more qualified than her: test pilots, engineers, and world-class parachutists. After intensive training, however, Tereshkova proved she could make the final cut. In the end, Tereshkova was one of two final candidates.

On June 14, 1963, Vostok 5 was launched into space with cosmonaut Valeri Bykovsky aboard. With Bykovsky still orbiting the earth, Tereshkova was launched into space on June 16 aboard Vostok 6. The two spacecraft had different orbits but at one point came within three miles of each other, allowing the two cosmonauts to exchange brief communications. It was a stellar achievement! Not only did Tereshkova become the first woman in space, but with one single flight , she also logged more flight time than all previous American astronauts put together at the time – 70.8 hours in space with 48 orbits of the Earth. While in space, the first female cosmonaut performed experiments intended to assess the effects of microgravity and space on the human bod y a nd took photos that helped identify aerosols in the atmosphere.

Unfortunately, her landing wasn’t a smooth on e: b y the time she ejected from the capsule, Tereshkova was famished and dehydrated from poor food and agonizing injuries brought about from being strapped in her seat for three days straight. According to her own recent account (at the time, any kind of internal behavior that could discredit the Soviet Union would be immediately dismissed), when parachuting down, Tereshkova saw that she was heading for a large lake. With her body numb and weak , s he doubted she could swim to shore. Luckily, a high wind blew her over to the shoreline and she landed safely, albeit roughly. Her nose banged pretty hard on her helmet and she had to wear makeup in public to cover up the subsequent bruises.

After landing, Tereshkova never flew again, but did study engineering at the Zhukovsky Air Force Academy and eventually obtained her Ph.D. in 1977. She also became a prominent politician, served on international councils , s poke at international conferences, played a critical role in socialist women’s issues, and was awarde d t he USSR’s highest honor , the Hero of the Soviet Union medal, along with many other awards.

Unfortunately, while at the surface the Soviet society cherished her, it was secretly eating her alive . After her flight, Tereshkova dealt with Air Force officials who sought to discredit her by claiming she was insubordinate and drunk on the launch pad (they were eventually dismisse d) a nd pressured her into marrying Andrian Nikolayev, the only bachelor cosmonaut at the time, in a lavish ceremony presided over by Khrushchev himself. The marriage wasn’t happy at all, but if the two divorced it would have meant the end of both of their careers.

In 1978, the female cosmonaut program was finally relaunched, and Tereshkov a immediately signed back up. While undergoing medical review, Tereshkova met and fell in love with physician Yuliy Shaposhnikov. Although she failed her medical review and never went back into space, Tereshkova separated from and successfully divorced her first husband (the divorce had to be approved by then-Premier Leonid Brezhnev; he granted it in 1982) and married Yuliy. Following the USSR collapse in 1991, she lost political office.

In 1999, her husband died and she retire d t o a small house on the outskirts of Star City. In 2013, at a state celebration for her seventieth birthday, Tereshkova said she’d love to go to Mars, jokingly or not, even if it was a one-way mission. The former cosmonaut isn’t alone in committing herself to such a mission : t housands of people from around the world have signed up to a project called Mars One, which has announced plans to launch a private mission to land a group of four men and women on Mars in 2023 to found a permanent colony. So far, a hundred people have been shortlisted.

Needless to say, there are a lot of things we can learn from Tereshkova’s story, but there’s also a lot we can learn from the USSR’s approach to women in science . Take this letter from a girl in Ukraine to Yuri Gagarin :

I have wanted to ask you for a long time already: ‘is it possible for a simple village girl to fly to the cosmos?’ But I never decided to do it. Now that the first Soviet woman has flown into space, I finally decided to write you a letter….I know [to become a cosmonaut] one needs training and more training, one needs courage and strength of character. And although I haven’t yet trained ‘properly’, I am still confident of my strength. It seems to me that with the kind of preparation that you gave Valia Tereshkova, I would also be able to fly to the cosmos.

Now, compare it to this letter written by a fifteen-year-old American girl to John Glenn:

Dear Col. Glenn, I want to congratulate you on your successful space flight around the earth. I am proud to live in a nation where such scientific achievements can be attained. I’m sure it takes a great amount of training and courage for you to accomplish such a feat. It was a great honor to witness this historical event. I would very much like to become an astronaut, but since I am a 15 year old girl I guess that would be impossible. So I would like to wish you and all of the other astronauts much success in the future.

Was this helpful?

Related posts.

- Stephen Colbert ridicules administrator’s plan to allow NASA corporate sponsorships

- Cristina Birch, former national track champion, selected as NASA astronaut

- Astronauts’ blood can flow in reverse and even stagnate

- X-rays reveal what lies beneath spacesuits in new Smithsonian exhibit

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

- How we review products

© 2007-2023 ZME Science - Not exactly rocket science. All Rights Reserved.

- Science News

- Environment

- Natural Sciences

- Matter and Energy

- Quantum Mechanics

- Thermodynamics

- Periodic Table

- Applied Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Biochemistry

- Microbiology

- Plants and Fungi

- Planet Earth

- Earth Dynamics

- Rocks and Minerals

- Invertebrates

- Conservation

- Animal facts

- Climate change

- Weather and atmosphere

- Diseases and Conditions

- Mind and Brain

- Food and Nutrition

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- The Solar System

- Asteroids, meteors & comets

- Astrophysics

- Exoplanets & Alien Life

- Spaceflight and Exploration

- Computer Science & IT

- Engineering

- Sustainability

- Renewable Energy

- Green Living

- Editorial policy

- Privacy Policy

- Valentina Tereshkova Biography

Flying into space wasn’t something women were exactly encouraged to do during the second half of the 20th century. Being a part of a space exploration team was exclusively reserved for men, although there were women out there interested in pursuing an astronaut career. However, they were hindered by a strategically articulated prerequisite of needing to have a substantial amount of pilot experience, regardless if they had actual astronaut training or not.

Nonetheless, during the 1960s, the Soviet Union decided to be the first country to send a woman into space. Valentina Tereshkova was the woman pioneer who in 1963, managed to fly into space and orbit the Earth, not once, but a total of 48 times in the span of three days.

From a Textile Mill to Parachuting

Valentina Tereshkova was born in a small village Bolshoye Maslennikovo in the west of Russia , on March 6, 1937. She was one of three children of Elena Tereshkova and Vladimir Tereshkov who died in World War II when Valentina was merely two years old. Her mother Elena raised her three children alone after her husband was killed, and worked hard as a textile worker.

When Valentina turned 18 years old, she got a job at the same textile mill where her mother was working, but soon afterwards decided to pursue amateur parachuting as well. It didn’t take long for her to start broadening her horizons and to develop a hunger for flying. As fate would have it, Valentina applied for astronaut training overseen by Yuri Gagarin in 1961, just as the Soviet Union was looking to start training women for space. This, obviously, had nothing to do with the Soviet Union being feminist-oriented but rather with the competition with the United States, where each of them wanted to be the first in as many things possible connected to space exploration.

And Off She Went

As official records state, Valentina Tereshkova became the first ever woman in the world to be a part of an active astronaut team and was sent into space on June 16, 1963. It was previously questioned whether or not women can withstand the rigorous training as well as the harsh conditions in space. As it turns out, they can, and then some. The tests conducted during the flight showed that women are actually even better equipped than men when it comes to tolerating gravitational forces.

Tereshkova and her teammate Bykovsky were celebrated all over the Soviet Union upon their return. Tereshkova was even given the title of the Hero of the Soviet Union and was decorated by Brezhnev himself. Although she dedicated much of her time after the flight to spreading feminist values across the world, and was praised for her efforts, the Soviet Union wasn’t as kind to her and other female astronauts as one would conclude. While the rest of the world thought that the Russian women were treated as equal to men in their home country, the reality was much different. The opportunity given to Tereshkova was used as a marketing ploy to keep the appearance of an egalitarian society, when the truth was that they weren’t considered to be the same, not in the home setting nor in regards to the flight opportunities.

An Ambassador for Women Across the World

In 1963, Tereshkova married a Soviet astronaut Nikolayev, who went into space only a year before she did. A year after they were married, on June 8, 1964, they welcomed a daughter into their family, who they named Yelena Adrianovna Nikolayeva. Although they feared that their daughter might suffer some health consequences related to their own exposure to space radiation, nothing alarming was ever found.

After her career as an active astronaut, Tereshkova went on to take up aerospace engineering, but also made substantial contribution to the Soviet culture and society, not only by heading the Soviet Women's Committee and the USSR's International Cultural and Friendship Union, but also by inspiring countless women to go after their dreams no matter what obstacles lie ahead.

More in Feature

Are Former Soviet Member Countries More Religious Today?

5 Facts To Know About The Future Of Buddhism

Reasons Why Muslims Are The World’s Fastest-growing Religious Group

The Uprising At Sobibor Extermination Camp

How Many People Have Ever Lived On Earth?

Fact Check – Are No Two Snowflakes Exactly Alike?

The Smithsonian Natural History Museum: Beyond The Public View

The Three Rs Of Animal Testing: A More Humane Approach To Animal Experimentation

How to Decipher the History Written in Our Genome

The most innovative ways to use crispr, openmind books, scientific anniversaries, nanomedicine to fight cancer, featured author, latest book, valentina tereshkova: from space to the kremlin.

When she was a child, Valentina Tereshkova (March 6, 1937) dreamed of being a train driver . She was fascinated by the idea of taking trains, seeing different cities and meeting people. Her childhood was truncated by the Second World War, in which her father died on the front lines. “We were children of the war,” she recalled a couple of years ago at the Science Museum in London.

Little Valentina did not imagine then that she would not drive trains but spacecraft and that she would become a legend, being the first woman to do so. At age 80, Tereshkova is an icon in her country.

After her space career, she obtained a doctorate in engineering and became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Today she is still active in political life and regularly attends the Duma—the parliament of the Federal Assembly of Russia. President Putin himself congratulated her on her last birthday .

The proletarian as an icon

Valentina’s mother learned to read at the age of 26. After becoming a widow, she raised her three children in the village of Maislennikovo, in central Russia. Valentina started school at the age of eight but had to leave at sixteen to begin working.

A keen amateur skydiver, she trained in a local club, a decision that would mark the direction of her life. While working in a textile factory, the Soviet Air Force undertook an exhaustive search in flying clubs to locate women parachutists. Valentina was one of the four hundred chosen.

Surrounded by great secrecy, the young women had to overcome different eliminatory tests and in the end there were just five left, among them Tereshkova. After two years of training, she was chosen to be the first woman to fly in space.

The cosmonaut claims to be ignorant of why they chose her. Sergei Korolev, principal designer of the Soviet space program, stated at that time that, although her comrades were better prepared, “none could compete with Tereshkova in the ability to influence crowds, arouse sympathy among people and appear before an audience.”

Her humble origins and her proletarian profile brought her closer to the people, which fitted perfectly with the model sought by Russian leaders.

The mistake that could have ended her life

On June 16, 1963, Tereshkova took to space in command of the Vostok 6 mission. The objective, in addition to surpassing the United States by sending the first female astronaut to space (as had already happened with Yuri Gagarin), was to find out how the female body responded to these extreme conditions.

The mission lasted almost three days, in which Tereshkova—who was then 26 years old— orbited the Earth 48 times. When she was already in orbit, the cosmonaut realized an error in the control program that would have prevented her from descending to return to Earth. After she communicated the problem to the base, they were able to correct it but Korolev asked her to keep it a secret. Tereshkova stayed silent for thirty years, until the person responsible for the error finally made it public.

Her exploit caused a great stir in the Soviet Union. As Tereshkova’s mother had no television, her neighbours invited her to their house to see Valentina in space , which was a real surprise to her as she knew nothing due to the secrecy of the Russian authorities.

The second woman, nineteen years later

Nineteen years had to pass before another woman would fly in space, Russian Svetlana Savistskaya, who did so with the Soyuz-T 7 mission in 1982. Russia won the women’s space race over the United States by a wide margin, as the first American woman who made it to space was Sally Ride in 1983.

Why did Russia take so long to send a woman back into space? Although for Nikita Khrushchev, the first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the space race was a priority—he even attended the wedding of Tereshkova with the also-cosmonaut Andriyan Nikolayev—with his dismissal in 1964 the goals changed. For the new leader, Leonid Brezhnev, the space program was no longer a priority and a new group of female cosmonauts was not trained until 1979.

After her mission, Tereshkova studied space engineering and obtained her doctorate in 1977. In those years she was a member of the Supreme Soviet and until 1991 belonged to the Central Committee of the Communist Party. On her eightieth birthday, Vladimir Putin congratulated her in person with these words: “You have always been an example to us of how you have served the motherland, over time and with different tasks. Today you continue to do so in the Duma.” Now retired from the air force, Tereshkova retains that thirst for adventure that took her into space and has reiterated that she would like to fly to Mars , even if it were only a one-way trip.

Laura Chaparro

@laura_chaparro

Related publications

- 5 Milestones of the Soviet Space Race

- Yuri Gagarin and the Day we Went into Space

- The Conquest of Space

More about Science

Environment, leading figures, mathematics, scientific insights, more publications about ventana al conocimiento (knowledge window), comments on this publication.

Morbi facilisis elit non mi lacinia lacinia. Nunc eleifend aliquet ipsum, nec blandit augue tincidunt nec. Donec scelerisque feugiat lectus nec congue. Quisque tristique tortor vitae turpis euismod, vitae aliquam dolor pretium. Donec luctus posuere ex sit amet scelerisque. Etiam sed neque magna. Mauris non scelerisque lectus. Ut rutrum ex porta, tristique mi vitae, volutpat urna.

Sed in semper tellus, eu efficitur ante. Quisque felis orci, fermentum quis arcu nec, elementum malesuada magna. Nulla vitae finibus ipsum. Aenean vel sapien a magna faucibus tristique ac et ligula. Sed auctor orci metus, vitae egestas libero lacinia quis. Nulla lacus sapien, efficitur mollis nisi tempor, gravida tincidunt sapien. In massa dui, varius vitae iaculis a, dignissim non felis. Ut sagittis pulvinar nisi, at tincidunt metus venenatis a. Ut aliquam scelerisque interdum. Mauris iaculis purus in nulla consequat, sed fermentum sapien condimentum. Aliquam rutrum erat lectus, nec placerat nisl mollis id. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Nam nisl nisi, efficitur et sem in, molestie vulputate libero. Quisque quis mattis lorem. Nunc quis convallis diam, id tincidunt risus. Donec nisl odio, convallis vel porttitor sit amet, lobortis a ante. Cras dapibus porta nulla, at laoreet quam euismod vitae. Fusce sollicitudin massa magna, eu dignissim magna cursus id. Quisque vel nisl tempus, lobortis nisl a, ornare lacus. Donec ac interdum massa. Curabitur id diam luctus, mollis augue vel, interdum risus. Nam vitae tortor erat. Proin quis tincidunt lorem.

The Mathematical Secrets of Escher

Do you want to stay up to date with our new publications.

Receive the OpenMind newsletter with all the latest contents published on our website

OpenMind Books

- The Search for Alternatives to Fossil Fuels

- View all books

About OpenMind

Connect with us.

- Keep up to date with our newsletter

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The first woman in space: 'People shouldn’t waste money on wars'

In 1963 Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman to go into space. On her 80th birthday, she looks back at a lifetime of immense political change

P arachuting was her first love. The moment she could, Valentina Tereshkova joined the renowned paramilitary flying club in her native Yaroslavl (without telling her mother) and trained almost every weekend. She has more than 90 jumps under her belt. “I did night jumps, too, on to land and water – the Volga river.” Day and night, she tells me, “it’s a very different experience, but both are wonderful”, and she spreads her arms wide as though balancing herself in flight, radiating delight. “I learned to wait as long as possible before pulling the cord, just to feel the air; 40 seconds, 50 seconds ... It’s not really falling; you experience enormous pleasure from the sensation of your whole body. It’s marvellous.”

It is hard to believe that the woman sitting across the table from me enthusing about her early hobby is 80. All right, she turned 80 only a few days ago, but even immaculate hair and makeup can only flatter so much. She looks to me not a day over 70. My gaze keeps alighting on her elegant hands with their flawless dark nail varnish. My own (rather younger) hands look wrinkled and gnarled by comparison.

We are somewhere deep and indeterminate within the cavernous Science Museum in London, and Tereshkova had arrived, as dignitaries tend to do, suddenly, and with a flurry of suited escorts. I had seen her so often, in photographs, in film, and from a distance in person – that she seemed entirely familiar, from her tailored suit to the medal she wears, red banner with gold star, denoting her status as a Hero of the Soviet Union, then the highest state award.

The reason for her celebrity is almost as hard to believe now as the parachuting. Over 50 years ago, in 1963, Tereshkova became the first woman to go into space, and it was her parachuting experience that qualified her for selection. She was only 26 when she made her one and only space flight, but that feat has defined the rest of her life. It propelled her into the upper reaches of the Soviet elite, and gave her security for life. That elevation though came at a life-long cost: a treadmill of obligations that has lasted more than half a century.

Public speaking, accepting honours, roving the world as a citizen-diplomat, being a very visible part of Soviet, and now Russian, public life, are roles that she continues to fulfil to this day. Hence her visit to London for the opening of a display of artefacts linked to her cosmonaut’s life. It is one of a series of UK-Russia collaborations, following the hugely successful Russian space exhibition at the museum last year.

Has she honestly enjoyed this life lived so much in the public eye? “I think it’s tremendously important to meet people, to establish a connection and tell people about space,” she says gravely. “It can increase trust, and that is something that is so badly needed, today.”

Aware of the current chill in the international climate, Tereshkova sees herself, (not for the first time) with a responsibility to help improve things through public diplomacy. In the UK, she might be surprised to discover how relatively few now know her name. The global impact of her flight, with the near-universal recognition that followed, has faded over the years, though not in Russia, and not for me, as a child of that era.

Unsmiling and austere, sometimes in military uniform, Tereshkova is a fixture in my memory as she remains for many Russians. She was always conspicuous, not least because women were so few in the top line-ups for official Soviet occasions. As a Moscow-based correspondent in the late 1980s, I saw her at the various political gatherings convened by Mikhail Gorbachev in his twin causes of glasnost and perestroika. She made the transfer, effortlessly, or so it seemed, into the elite of post-Soviet Russia.

But it is the grainy footage of Tereshkova the cosmonaut that is most memorable. I am just old enough to remember the early “space race”, with the Americans and the Soviets vying for supremacy in the heavens. These were years when a distinction was observed between astronauts (American) and cosmonauts (Russian), and the terms “space” and “cosmos” existed side by side.

We knew about Laika, the dog who won the animal space race for the Soviet Union in 1957, but who died sooner than we knew . Four years later, Yuri Gagarin just pipped the American, Alan Shepard, to be the first man into space. A year later, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth.

Then, in 1963, the pendulum swung back, with Tereshkova registering a win for the Soviets, when she became the first woman to fly in space. Perhaps the most coveted prize, though, went to the Americans when they made the first moon landing in 1969. You can sense, even 40 years on, that this victory still rankles just a little with Russians to this day.

Revisiting the rivalry of the space race helps cast light on mysteries that long surrounded Tereshkova’s flight. One is the suggestion that it was, in many respects, a failure: The charges were that the first female cosmonaut had been too ill and lethargic to conduct the planned tests on board; and/or that she had unreasonably challenged orders.

Tereshkova only gave her definitive account 30 years later, and she repeats it for my benefit. She denies being ill – or more ill than might be expected – or failing to complete the on-board tests; the voyage was, actually extended from one to three days at her request, and the tests had been planned only for one.

As for insubordination, there was a hitch, and a serious one, that emerged soon after lift-off. As she tells it, she discovered that the settings for re-entry were incorrect, to the point where she would have sped into outer space, rather than back to Earth. She was eventually sent new settings, but her space centre bosses made her swear to secrecy about the mistake, to save their own reputation and that of the programme. “We insisted that all was OK; we didn’t talk about it. We kept it secret for 30 years, until the person who made the mistake was in his grave.”

The view of the Earth from space remains with her, as it does with so many astronauts, as “a planet at once so beautiful and so fragile”. Everyone, she says, “Americans, Asians, everyone who has seen it says the same thing, how unbelievably beautiful the Earth is and how very important it is to look after it. Our planet suffers from human activity, from fires, from war; we have to preserve it.”

Had the experience changed her? “When you are up there, you are homesick for Earth as your cradle. When you get back, you just want to get down and hug it.”

She is particularly concerned about the risk from asteroids, and ferrets around in her bag to find a fragment of a meteorite that hit Russia. “It’s tiny,” she says, “but very heavy.” She wants more work to be done to avert the threat of a devastating collision. “People shouldn’t waste money on wars, but come together to discuss how to defend the world from threats like asteroids coming from outer space.”

Tereshkova shares with astronauts and cosmonauts around the world a profound nostalgia for the experience of space. Having hoped against hope to make another flight, she is on record as saying that she would volunteer for a one-way trip to Mars .

I flick back to the day she was selected for the space mission, after hard months of training and continual monitoring, from among five women who were competing for the single slot on Vostok 6. Was she surprised, and weren’t the others envious? Not at all, she says almost scornfully. “We believed each of us was worthy of being chosen.” Had she kept up with the others since? I ask, (there have been reports that she is less solicitous of friends and family than she could have been). Surprised by the question, Tereshkova allows herself a rare smile and her eyes light up. Yes, she says, the group meets up from time to time, obligations and illness permitting. “There is a bond, a comradeship, that never goes away.”

There may indeed be a special bond among the early cosmonauts, but as she grew used to fame, Tereshkova’s personal life became rocky. Her first marriage to a fellow cosmonaut, Andriyan Nikolayev, had been encouraged, if not actually arranged, by the space authorities as a fairytale message to the country. The then Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev officiated at the nuptials. But this state-sanctioned element made it hard when the relationship turned sour. The split was finally formalised in 1982, when Tereshkova married Yuli Shaposhnikov, a surgeon, with whom she lived happily until his death in 1999.

Tereshkova’s life is unique as the first woman in space, but she is also inevitably a child of her times. Her 80 years span an extraordinary kaleidoscope of Russian history. I run through it, for her response. She was born in 1937, a year that casts, I suggest, a certain shadow (when Stalin’s purges were at their height). She catches the reference, but does not elaborate.

After the political thaw, under Khrushchev, came the long “stagnation”, under Leonid Brezhnev, followed by the tumultuous reforms introduced by Gorbachev. Tereshkova stops me mid-flow. “The Soviet Union was important for more than one generation. I am not ignoring the mistakes, the highs and the lows, but as a whole … It is wrong to paint it only in dark colours. There was a lot of good as well.”

This is a familiar defence of the Soviet Union. For many Russians who lived through those years, the end of the Soviet Union is regarded as a betrayal. How does Tereshkova see it? In an echo of Putin’s much-quoted remark, she says “We all experienced the end of the Soviet Union as a personal tragedy and can’t forgive those who allowed it to happen.” How does she rate Gorbachev? She almost spits out her answer. “I don’t respect him; I don’t even want to hear his name.” How about Boris Yeltsin, who wrested power, to be the first president after the Soviet collapse? “I didn’t know him. The one I know is Vladimir Putin.”

Tereshkova is a big fan of Putin and he, it would appear, of her. He congratulated her personally on her 70th and 80th birthdays and added to her tally of awards. “An awful lot depends on leaders,” she says. “Putin took over a country that was on the brink of disintegration; he rebuilt it, and gave us hope again.” People trust him, she says. “You only have to see how he is received, how people respond to him. He’s a splendid person.”

It appears that the habits of a Soviet lifetime die hard. In so saying, Tereshkova reflects the views of many ordinary Russians, of a generation that has lived through almost continual, and often alarming, change. They grew up, consciously or not, if not in fear, then knowing the price of not conforming. They embrace the stability they associate with Putin – and that is at least part of his success.

Could Tereshkova have done more – to advance the cause of women, say, to promote individual rights – given her privileged position and the status she enjoyed? Perhaps. But, she showed that women could do what was then regarded as the most state of the art, most demanding feat – going into space, solo.

Seen from today’s Russia, her one pioneering feat, followed by a lifetime of civic duty, have served to keep both the capability of women and the fragility of the planet in the public eye, and that must be accounted a contribution, too.

Valentina Tereshkova: First Woman in Space is at the Science Museum until 17 September 2017.

This interview is the second in a series.

- Indira Jaising: ‘In India you can’t even dream of equal justice. Not at all’

Guardian women seminar: How women can change the world is being held at the Guardian offices in London on Thursday 4 May. Register to attend here .