Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Use of Discourse Markers in the Background of Thesis Proposals Written by Postgraduate Students

Discourse marker affects the logical meaning that is conveyed by an author to the readers. This article reports the analysis of discourse markers inside the background of master thesis proposals. The data presented were gained from eight students who had finished their comprehensive paper seminar in a postgraduate program. Eight backgrounds of master thesis proposals had been analyzed qualitatively. The results of this research revealed that there was a mix-used of the discourse markers. Each draft showed both appropriate and inappropriate use of three discourse maker classes. The appropriate discourse markers had no digression of the stipulated form and were found free from misuse patterns. On the contrary, the discourse markers were found as inappropriate use. The most dominant problem experienced by the students was the high density of discourse markers in a short text or connective overuse misuse pattern. The three classes of discourse markers had some common variants. There wer...

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 January 2023

The use of discourse markers in argumentative compositions by Jordanian EFL learners

- Anas Huneety 1 ,

- Asim Alkhawaldeh 2 ,

- Bassil Mashaqba ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0835-0075 1 ,

- Zainab Zaidan 1 &

- Abdallah Alshdaifat 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 41 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1831 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

The aim of the present study is to investigate the use of discourse markers (DMs) in the argumentative compositions written by EFL learners at two academic stages (sophomores and seniors) majoring in English at the Hashemite University, Jordan. The significance of this study springs from its focus on the use of DMs in Jordanian EFL learners’ argumentative writings. Employing an integrated research method of qualitative and quantitative analysis, the findings revealed that both groups of participants used the same types of DMs with varying degree of frequency, namely, elaborative, contrastive, reason, inferential, conclusive, and exemplifier DMs, respectively. The sophomores were observed to employ a relatively higher number of DMs compared to the seniors, which may be ascribed to some redundant instances of DMs. The elaborative, contrastive, and reason types were the most widely used, while inferentials, conclusives and exemplifiers appeared infrequently in both groups. The analysis of individual DMs displayed that the DMs ‘and’, ‘because’, and ‘but’ were the predominant across the seniors and sophomores’ argumentative texts. This overuse of these DMs may be due to the influence of L1 of the participants and the popularity of these DMs among students and teachers of English. Additionally, the participants showed a low proficiency in using DMs since they overused largely a restricted variety of DMs at the expense of others that would be expected in the argumentative writing; some DMs were noticed either to be underused or absent. The results of Pearson’s r correlation test indicated that there was a weak positive but significant correlation between the writing quality and the use of DMs. This may be taken as a predictor of the writing quality in argumentative compositions by EFL. Pedagogically, the study emphasizes the significance of teaching DMs, where EFL learners should be taught how to use them appropriately to avoid any transference of their L1. Further research on DMs in argumentative writings in different levels of proficiency is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

A corpus-based comparison of linguistic markers of stance and genre in the academic writing of novice and advanced engineering learners

Effects of input enhancement and genre on L2 learners’ performance in the continuation writing task

The art of rhetoric: persuasive strategies in Biden’s inauguration speech: a critical discourse analysis

Introduction.

Recently, there has been a thriving interest in academic research on linguistic items such as ‘but’, ‘and’, ‘therefore’, ‘because’ (widely referred to as discourse markers ) that signal the underlying relations that bind units of discourse into a larger cohesive and coherent text (e.g., Aijmer, 2002 ; Alkhawaldeh, 2018 ; Andersen, 2000 ; Beeching, 2016 ; Blakemore, 2002 ; Erman, 1987 ; Fedriani & Sansó, 2017 ; Foolen, 1996 ; Fraser, 1999 ; González, 2004 ; Heine et al. 2021 ; Huneety et al., 2017 ; Jucker, 1997 ; Lenk, 1998 ; Lewis, 2003 ; Olmen et al., 2021 ; Traugott, 1995 ). Discourse markers (DMs henceforth) count a functional category that do not typically alter the propositional content of an utterance but play largely an important role in the structuring and organization of discourse. This role that reflects an interpretive relationship between the segment hosting them and the prior utterance can be manifested by means of elaborating or commenting on the prior discourse, indicating a contrast between the foregoing and forthcoming discourse, drawing attention to what is next, reformulating an idea, or highlighting a proposition (Heine et al. 2021 ).

DMs constitute an indispensably fundamental part of language use, and their pervasiveness in speech and writing makes them a worthwhile object of study. The importance of exploring DMs lies in the fact that they aid discourse cohesion and coherence-they serve as cohesive devices that mark underlying connections between propositions (Al-Khawaldeh, 2018 ). It has been argued that the use of DMs facilitates the hearer/ reader’s task of interpreting and understanding the speaker/writer’s utterances (Müller, 2005 ; Aijmer 2015 ; Schiffrin, 1987 ; Blakemore, 2002 ; Huneety, et al., 2019 ). The adequate use of DMs is pivotal in rendering texts (especially in the context of academic writing) comprehensible and effective. Academic writing that employs DMs is perceived to be more logical, persuasive, and authoritative (Mauranen, 1993 ). It thus appears that examining DMs in learners’ writing, as the goal of the present study, is a compelling task for the applied linguistics researcher (Siepmann, 2005 ).

Many studies have highlighted that the use of DMs poses a challenge for EFL learners, especially in writing at colleges and universities. This would be ascribed to a variety of reasons: (i) overuse, underuse, and misuse of DMs are likely to affect the readability and comprehensibility of the text; (ii) the use of DMs is sensitive to text type (e.g., DMs used in argumentative writing differs from those used in expository writing); and (iii) the use of DMs, particularly for EFL learners, tends to vary across languages and cultures (see Altenberg & Tapper, 1998 ).

The present study investigates the use of DMs in argumentative texts written by two groups of learners at two different levels of proficiency (sophomores and seniors) at the Hashemite University in Jordan. The reason beyond the choice of this type of writing is that it has been characterized as the hardest type in both L1 and L2, in comparison with other types of writings such as narrative and expository (see Yang and Sun 2012 ).

To achieve the purpose of the present examination, an integrated method of research analysis was employed: quantitative and qualitative. Following Altenberg and Tapper ( 1998 ), the comparison in terms of similarities and differences between these two groups of learners was concerned mainly with the overuse and underuse of DMs. These two terms are used in our analysis as purely descriptive labels in the data under examination. Therefore, the misuse of DMs with regard to their incorrect usage (grammar, spelling, punctuation, etc.) is beyond the scope of the present study. Given that, the study seeks to explore the following research questions:

1. Which types of DMs are more or less frequent in argumentative compositions used by EFL learners?

2. Are there any significant differences between sophomores and seniors in the use of DMs in their writing?

3. Is there any correlation between the number of DMs employed in the text and the quality of writing?

The significance of this paper is generally two-fold. First, the insights obtained from the statistical and qualitative findings on how DMs are used by the respective EFL learners would be of some use by teachers and instructors at universities to improve the quality of the learners’ writing performance. Second, the expected findings may offer a better understanding of the correlation between the use of DMs and the quality of writing in Jordanian EFL argumentative composition.

Review of the literature

This literature review focuses on the general use of discourse markers and the studies conducted on the discourse of EFL learners. Numerous studies have been conducted on DMs and many researchers have investigated the use of DMs by EFL learners in particular e.g., (Martínez, 2004 ; Jalilifar, 2008 ; Chapetón Castro, 2009 ; Aidinlou and Mehr, 2012 ; Kalajahi, Abdullah, and Baki 2012 ; Povolná, 2012 ; Daif-Allah and Albesher, 2013 .

Many of these studies compared the use of DMS by EFL learners with that of English learners. These studies have emphasized the poor writing skills of EFL learners, which may be partially attributed to their poor usage of DMs. For example, Altenberg and Tapper ( 1998 ) observed that advanced Swedish learners of English underused DMs in their compositions compared to English native students. The most commonly used DMs by Swedish learners were contrastive and inferential ones, while summative DMs (e.g., in sum and short) were rarely used. In a recent study, Tapper ( 2005 ) compared the use of DMs by Swedish EFL learners of English to American university students. The findings reported that the Swedish learners of English used far more DMs in their essays than their American counterpart. This overuse of DMs by Swedish leaners of English may be a result of their native language transference which contains more DMs than English does as reported in Altenberg and Tapper ( 1998 ). Müller ( 2005 ) discussed the use of four DMS (well, you know, like and so) in the speech of German EFL learners’ and native speakers of English. Findings showed that although German speakers used the four discourse markers, some functions were mainly unknown to German speakers who also employed new functions. Fung and Carter ( 2007 ) examined the use of discourse markers by Hong Kong learners of English and English speakers. They found that Hong Kong learners widely employed referentially functional DMs (e.g., and, but, because, OK and so), yet they underused a number of DMs such as really, sort of, I see.

Various studies have examined the use and frequency of DMs and their impact of the quality of writing. Some of these studies demonstrated that the frequency of DMs was not an indicator of writing quality. For example, Alattar and Abu-Ayyash ( 2020 ) dealt with the use of conjunctions as cohesive devices in Emirati students’ argumentative essays. The study found no positive correlation between the Emirati students’ use of DMs and the quality of their argumentative writing. That is, in many essays, though many participants employed a wide range of DMs correctly, the quality of the texts was poor because it was difficult to understand these texts. Similarly, dealing with the cohesive devices, including connectives in papers written by Chinese learners, Zhang ( 2021 ) reported no link between unity of the text and writing quality.

However, some studies reported a correlation between the overuse of DMs. For example, examining the use of DMs in the expository writings by third-year and fourth-year Spanish EFL learners, Martinez ( 2016 ) found a positive significant correlation relationship between the density of DMs and the quality of writing. They also revealed that there was little variety in the use of DMs across the both groups of participants.

In the Turkish context, Uzun ( 2017 ) examined the use of DMs in argumentative essays written by Turkish EFL learners. In this study, the additive DMs were the most frequent type in the data while adversative and causal types were by far less frequently used. The findings showed a very weak positive relation between the essay scores and writing quality.

Some studies examined the use and frequency of DMs in particular types of texts, showing how each text type prefers some types of DMs. For example, Rahimi ( 2011 ) made a comparison between Iranian EFL learners’ argumentative and expository writings. He found that in both types of writing elaborative and contrastive DMs were the most frequently used. In another study, Doró ( 2016 ) conducted a study on DMs in argumentative essays written by third-year students of English in the Hungarian university. The study revealed that where the types of DMs with a high percentage of occurrence were elaborative, contrastive and inferential DMs, students tended to underuse summative markers, especially at the end of their essays. Similarly, Ghanbari et al. ( 2016 ) drew a comparison between Iranian EFL learners academic and non-academic writings. It was reported that that in academic writings, elaborative and inferential DMs were the predominate, whereas in non-academic writings only elaborative DMs were the most commonly used. In a study on DMs in argumentative and narrative texts written by native and non-native undergraduates, Alghamdi ( 2014 ) reported that DMs with a high frequency were elaborative, contrastive, and reason, and there was no significant difference in the use of DMs between both types of writing in the two groups.

An examination of the above literature shows that DMs were investigated in different contexts and in different languages. In the context of Jordan, there have been two studies addressing the use of DMs by Jordanian EFL learners: Ali and Mahadin ( 2015 ) and Asassfeh et al. ( 2013 ). Ali and Mahadin ( 2015 ) studied the use of DMs in expository writing of advanced EFL learners and intermediate EFL learners at University of Jordan. The study has found out that the proficiency level of the student affects the use of DMs. Asassfeh et al. ( 2013 ) have investigated the use of logical connectors in expository writings written by Jordanian English-major undergraduates representing the four academic years. They have concluded that students use logical connectors a lot but in an inaccurate way. This study aims to fill in a gap in the literature by examining the use of DMs in a new type of texts, i.e., argumentative compositions, by EFL students. To that end, a sample of 120 students were asked to write compositions that were then analyzed in terms of the use of DMs. What follows is a presentation of the methods employed to collect and analyze data. Results then presented and discussed. The study concludes with some concluding remarks and recommendation for future studies.

Theoretical Framework

This study draws mainly on Fraser’s ( 1999 ) broad characterization of DMs, particularly his taxonomy of DMs. This is because Fraser based his insights on other prominent studies on DMs (e.g., Schiffrin 1987 , Blakemore 2002 , Redeker ( 2006 )), and his description has been used for written discourse. Fraser ( 1999 ) defines DMs as lexical expressions that mostly signal a relationship between S2 and S1, where S2 is the discourse segment which hosts the DM as a part of it, and S1 is the prior discourse segment. Lenk ( 1998 ) refers to this function as the prominent textual function of DMs that indicates the kinds of relations existing between different parts of the discourse. DMs come from different grammatical classes, such as conjunctions (e.g., but, also, because,…etc.), adverbs (e.g., furthermore, however,…etc.), prepositional phrases (e.g., on the contrary, on the other hand, as a result …etc. (Fraser, 1999 ). DMs generally tend to occur in segment-initial position (to introduce an utterance). However, they may also occur medially and finally (ibid).

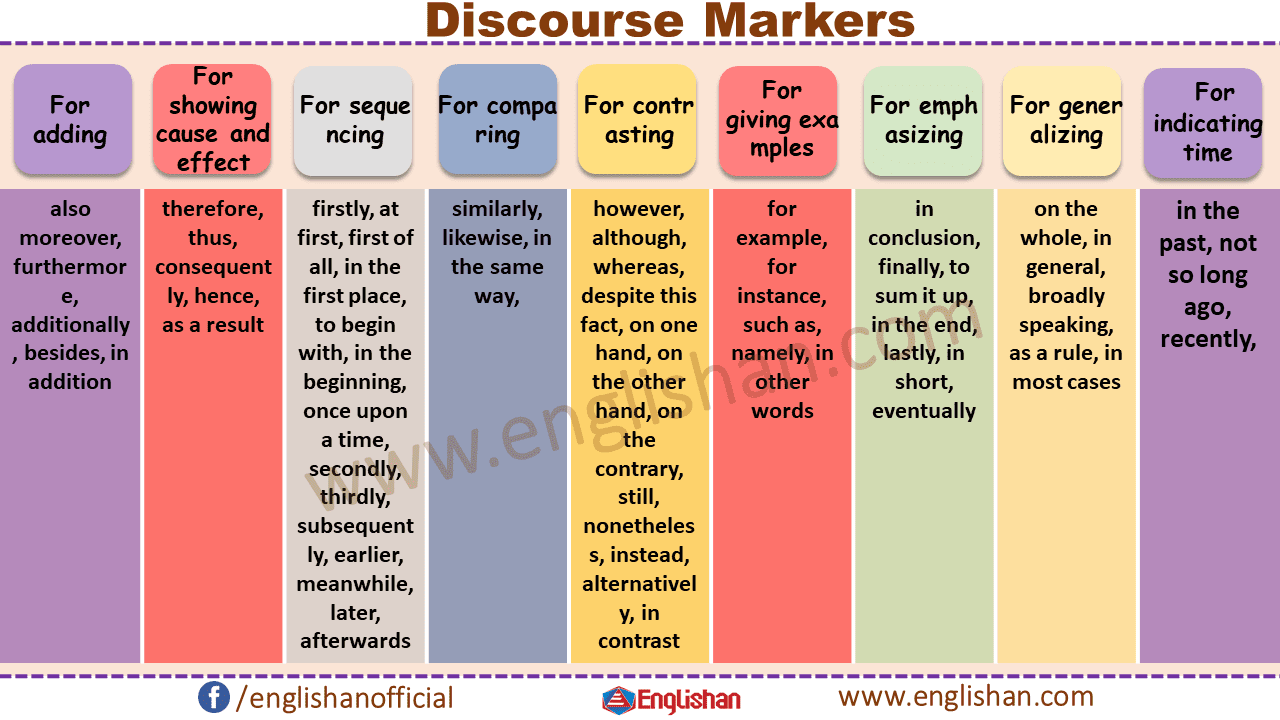

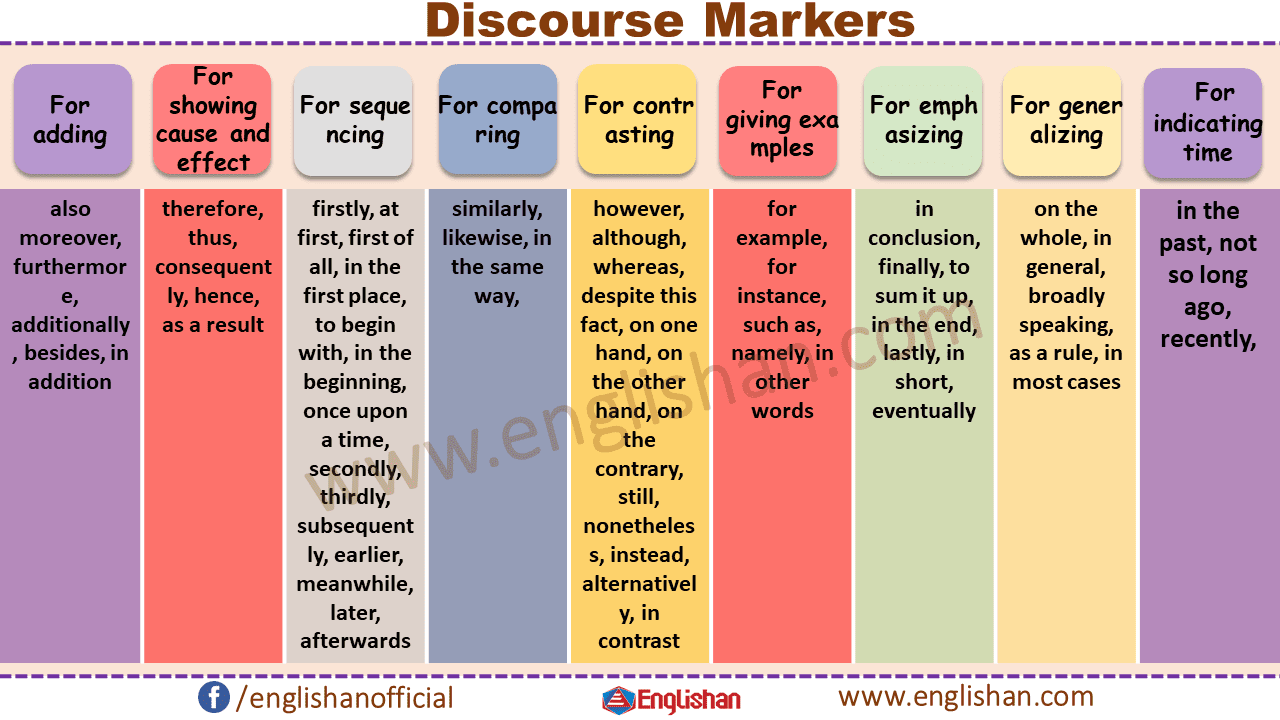

In this study, six categories of DMs were included for the purpose of analysis. Four of them were adopted from Fraser ( 1999 ): contrastive DMs (although, however, yet, etc.) elaborative DMs (and, moreover, in addition, etc.), inferential DMs (therefore, as a result, etc.), and reason DMs (because, since, etc.). The other two categories were suggested by Martínez ( 2004 ), namely, conclusives (in conclusion, in short, etc.) and exemplifiers (for example, for instance, etc.).

Methods and material

The participants of the present study were selected from two different levels of proficiency (sophomores and seniors) at the Hashemite University, Jordan. All of them were EFLs (their native language is Arabic), aging between 18 and 22. During the spring semester 2019–20, a total of 120 students were selected randomly from eight classes.

The students were divided into two groups: the first group consists of 60 sophomores who all passed basic grammar course and paragraph writing course , and the second group consists of 60 seniors who all passed advanced grammar course and essay writing cours e. These courses were based on to select the participants of the study, where the former two courses are required for sophomores and the latter two courses are required for seniors. Grammar courses help students gain systemic knowledge of English grammar (the basic and complex grammatical structure of sentences), meanwhile writing courses improve students’ writing ability skills (successful paragraph and essay development)

In order to ensure the homogeneity of the participants in the study and to cover all proficiency levels to get realistic results, the participants were of different gender (male and female) and GPA (ranging from good to excellent). The data of the present study is argumentative texts with a minimum word-count of 250 words on the online-learning. The following task was given to the participants:

‘Online education is rapidly increasing in popularity. Some people think that online teaching is as effective as in-person instruction, while others think online teaching is inferior. Discuss both these views and give your own opinion.’

This topic was chosen in particular because the Hashemite University students have experienced online learning over the past few years. The onset of Covid-19 pandemic has led to such a significant development in online learning. Therefore, we believed that the students are able to argue about this topic easily because they are aware of the advantages and disadvantages of the issue (For details, see also Abdalhadi, et al., 2022 ).

The researchers used a mixed approach in the present study to address the above-mentioned research questions. After a brief introduction on the importance of online education in Jordan), the students were given 40 min to write the task. All of the 120 paragraphs were examined. The process of identification of DMs in the compiled data draws mainly on Fraser’s ( 1999 , 2006 ) list of DMs, as presented in Table 1 . The reported DMs were calculated in terms of frequency. The wordsmith concordance software (wordsmith tool 4.0) was used for scanning DMs occurrences and generating concordance lists of all DMs detected in the data. For interrater reliability, the compositions were evaluated and scored out of (20 points) by two experienced raters, who are instructors of English. The essays scoring greater than 12 points were assessed as of good quality. The agreement index between the raters reached 95%, which indicates that the scoring was highly consistent among the two raters.

To obtain statistical values concerning writing quality, a Pearson’s r correlation test was applied to find out whether the frequency of the use of DMs and writing quality are correlated or not. Pearson’s r correlation is used to measure the strength of a linear correlation between two variables, where the value r = 1 means a positive linear correlation, r = −1 means a negative linear correlation, and r = 0 means no linear correlation. Finally, to compare the results of both groups of students, the means and standard deviations were measured and an independent-samples t-test was carried out to test the significance of difference between the two groups.

Results and discussion

Research question 1, which types of dms are more or less frequent in argumentative compositions used by efl learners.

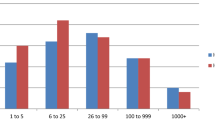

The quantitative analysis of data by means of the Wordsmith concordance software showed that the entire data set had a sum of 802 occurrences of 25 different DMs in the argumentative compositions. Tables 2 and 3 show that the participants in the present study used a number of DMs with various rates. All the types of DMs adopted for the present investigation were found to be used by the participants of the present study: elaborative, contrastive, reason, inferential, conclusive, and exemplifier. Although some DMs are by nature poly-functional, particularly ‘and’, all DMs detected in the present data were observed to serve only one function.

It can be noticed that both groups used the same types of DMs with varying frequencies. The number of DMs used by both groups revealed that there was no statistical difference, where the total frequency of DMs in the seniors’ argumentative texts was 415 occurrences and 387 in their sophomores’ counterparts. The reason why seniors employed a less number of DMs than did the sophomores may be attributed to the notion that the seniors tended to avoid overusing or redundant instances of DMs observed in the sophomores ‘compositions. This finding is in line with Altenberg & Tapper ( 1998 ), who found that the advanced Swedish learners of English used a less number of DMs than non-advanced ones. Moreover, in Yang and Sun ( 2012 ) on argumentative essays by Chinese learners of English at two levels of proficiency, sophomores overused DMs more frequently than did seniors. Put it differently, the sophomores slightly outperformed the seniors in terms of the frequency of DMs, which may be due to some redundant instances of DMs, where some DMs were unnecessary and their presence contributed nothing to the text coherence as seen in the examples below. Overall, it can be discerned that both sophomores and seniors had difficulties with using DMs in their argumentative writing in terms of overusing, underusing, omitting, or redundancy. Aijmer ( 2002 ) pointed out that learners may underuse or overuse certain forms in their writing in comparison with their native counterparts.

“Online learning depends on internet and the student himself. And online learning gives us more information and we can search about anything in it, and we can watch the online course more than one time to understand what it is talking about”.

“Classroom room learning have advantage like you can ask your teacher about anything you can’t understand. and in the same minute, you can share your information and make a conversation about it, and the teacher gives you homework to improve your skill.”

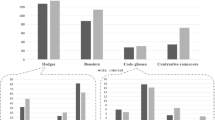

As shown in Table 2 , elaborative DMs appeared to be the predominate, compared to other types of DMs, in both groups of learners (sophomores = 49.9% and seniors = 40%). Contrastive DMs ranked the second in the data (sophomores = 18.3% and seniors = 26.9%), followed by reason markers (sophomores = 16.4% and seniors = 13.2%), exemplifiers (sophomores = 6.5% and seniors = 8.8%), and conclusive markers (sophomores = 5.1% and seniors = 8%). The least frequently used type is inferential DMs (sophomores = 3.8% and seniors = 3.1%). It is evident that there was no difference in the rank order of the types of DMs used by both groups of learners.

The statistical findings revealed, as displayed in Table 2 , that the three types of DMs (namely elaborative, contrastive, and reason) had a high frequency in the argumentative texts under exploration, in contrast to other types (exemplifier, conclusive, and inferential). Elaborative DMs accounted for the largest percentage of use, followed by contrastive DMs and reason DMs. This is in line with Alghamdi’s findings ( 2014 ), which reported that these three categories were utilized at higher rates than other DMs in argumentative compositions in his comparison between NS and NNS students in their narrative and argumentative texts. Likewise, Rahimi ( 2011 ) reported in his comparison between argumentative and expository writings by Iranian EFL learners that elaborative and contrastive DMs were used at higher rates than other DMs in argumentative compositions.

This high percentage of the occurrence of elaborative, contrastive, and reason DMs can be attributed to the argumentative mode of the respective texts written by the sophomores and seniors, where they require to employ such DMs for adding new arguments, contrasting ideas, and justifying standpoints. While it was found that the most frequently used types were elaborative DMs, followed by contrastive DMs in the present study, Polish undergraduate learners of English were reported to make more use of the contrastive type than the elaborative one in their argumentative essays (Sanczyk, 2010 ).

A further analysis of the DMs in the data under examination revealed that elaborative type ranked by far the highest in terms of frequency. It made up 49.9 % of the entire occurrence of DMs in the sophomores’ text and 40% in the seniors’ text. Among this type, the most commonly used DM was, as shown in Table 3 , the marker ‘and’, while the other elaborative DMs detected in the data (‘in addition’, ‘also’, ‘besides’, and ‘furthermore’) showed a low frequency, less than 7% for each one in the sophomores and seniors’ data. Table 3 displays that the elaborative DM ‘and’ appeared 150 times with an average of 36.1% by the sophomores, and 90 times with a percentage of 23.2% by the seniors. This is a relatively high percentage that a single item appeared to be taking up almost third of the entire frequency of DMs in the sophomore’s argumentative texts and around quarter in the seniors’ texts.

The overuse of ‘and’ in both groups is not surprising for two reasons. On one hand, preceding research findings report that EFL learners (regardless of their L1) are likely to employ more ‘ands’ than native speakers of English (Taweel, 2020 ). On the other hand, native speakers of Arabic are inclined to use more ‘ands’ as a result of interference of L1, Arabic, which is characterized with a high frequency of the additive marker wa:w ‘and’.

This overreliance on ‘and’ may signal a low proficiency in the use of DMs in the students’ argumentative writing (Uzun, 2017 ). Strikingly, some elaborative DMs such as ‘moreover’, ‘as well’, ‘too’, ‘or’, ‘in other words’, and ‘further’ were never used in the data. Thus, the overuse of ‘and’ at the expense of other elaborative DMs that were either rarely used or neglected indicates that the learners have a low proficiency level in using DMs.

More elaborately, the overuse of ‘and’ can be due, to a greater extent, to the negative transfer from Arabic as the mother tongue of the leaners, where the DM ‘wa’ ‘and’, in Arabic, is poly-functional that it serves various functions such as, in addition to elaborative, contrastive, causal, and temporal (Hamed, 2014 , Arabi & Ali, 2014 ).

However, it seems that the seniors employed ‘and’ less frequently than the sophomores who largely overused it. This indicates that there was some kind of development/ improvement in the proficiency level of the seniors as they incorporated other elaborative DMs more frequently than those by the sophomores, reducing dependence on ‘and’ in favor of other DMs. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that EFL learners used largely elaborative DMs in argumentative compositions in an attempt to explain, support, and develop their point of view in details, thus, make their thesis statement more well-expressed and persuasive.

Overall measures of DMs in both groups have shown that there is a relative decrease in the occurrences of the elaborative DM ‘and’ by seniors and increase of other elaborative DMs such as ‘also’, ‘furthermore’, ‘in addition’, compared to the sophomores, who used ‘and’ more repeatedly in their texts. That is, there is a common tendency among seniors to employ more frequently diverse elaborative DMs than sophomores.

As for the contrastive DMs that came the second in frequency in both groups, they were frequently used in comparison with other DMs such as, inferential and conclusive categories (the sophomores 18.3% and the seniors 26.9%). By contrast, Jalilfar ( 2008 ) reported that the contrastive DMs were the least in the essays written by the intermediate and advanced EFL learners. According to the statistical results, the contrastive ‘but’ was the highest among this class, and it was almost equally used by the sophomores and seniors, ranking third in the total occurrences of the DMs in the data (9.6% and 9%, respectively). This high frequency of ‘but’ may be attributed to the fact that it is very simple in its orthographic structure and semantically unambiguous, which renders it easy for learners to use (Djigunović and Vikov, 2011 ). Unlike other types of DMs, a variety of contrastive DMs (‘but’, ‘however’, ‘although’, ‘yet’, and ‘on the other hand’) were employed by both groups of learners rather than relying on a very limited number of DMs as the case with the class of reason DMs in this study. Interestingly, the seniors made more use of the contrastive DMs than did the sophomores, which indicates that they have more proficiency and knowledge about the nature of argumentative texts. Given that the argumentation is typically marked by showing a contrast, opposition, and juxtaposition between the argument and counterargument in order to convince the reader/listener of the acceptability of the controversial standpoint at issue (Eemeren, 2021 ), it was observed that some contrastive DMs that usually appear in argumentative academic compositions such as ‘nevertheless’, ‘nonetheless’, ‘whereas’, ‘conversely’, and ‘despite’ were never used by both groups.

Ranking the third largest category in both groups, the category of reason DMs was relatively moderately used by both groups (16.4% by the sophomores, 13.2% by the seniors). Dissimilar to these findings, it was reported that reason DMs were the most widely used by Turkish learners of English in their argumentative essays (Altunay, 2009 ). Among this class, the most commonly used one is ‘because’, contrast to other used ones, (after all, and for this/that reason) which were highly underused. Across the both groups, it was the second highest DM, making up 14.2% by sophomores and 10.6% by seniors. One DM, namely, ‘after all’, was used only by the seniors (0.8%), while other DMs, such as ‘since’ was totally absent in both groups. All in all, both groups of learners tend highly to overuse ‘because’ at the expense of other reason DMs, which were largely underused or absent. This could be argued that the learners heavily relied on ‘because’ to compensate for their unfamiliarity with other reason DMs. These results most probably reflect that this type of DMs poses a difficulty for the subjects of the present study.

Less frequently used types in the data were conclusive and exemplifier DMs. The former was used 5.1% by the sophomores and 8% by the seniors whereas, the latter was used 6.5% by the sophomores and 8.8% by the seniors. Only three conclusive DMs (‘in conclusion’, ‘in short’, and ‘to sum up’) were employed by both the sophomores and seniors. Comparing the both groups, the conclusive type had a higher frequency in the seniors’ argumentative texts than the sophomores’ texts. The DM ‘in conclusion’ was the predominate one among this type, while the others were mostly underutilized, where its total frequency in the whole data in both groups was 3.4% by sophomores and 5.7 % by the seniors. Concerning exemplifiers, like the conclusive types, only three DMs (‘for example’, ‘for instance’, and ‘such as’) appeared in the data. The findings showed that the most commonly used one in this class was ‘for example’ in the sophomores’ texts and ‘such as’ in their counterparts. It seems that these two categories appeared more in the seniors’ argumentative compositions. This evidently indicates that there is a development in the seniors’ proficiency level as compared to their counterparts regarding using exemplifiers to give examples as evidence in order to support their argument and conclusives to signal that they have reached the end of the composition and will summarize what has been argued for or against.

As given in Table 2 , the least frequently used type by both groups of learners was inferential DMs, accounting for 3.8% by the sophomores and 3.1% by the seniors. This indicates that there was no significant difference between these groups of students with regard to using this type of markers. The analysis showed that the inferential DMs found in the data include ‘thus’, ‘therefore’, ‘because of’, ‘as a result’, and ‘accordingly’. In the inferential category, the DMs ‘as a result’ had the highest frequency in the sophomores’ data, but it was totally neglected in the seniors’ data. While ‘because of’ was the least frequently used by sophomores in the inferential category, it appeared the most frequent one by the seniors. Overall, the students here displayed a tendency to underuse this type of DMs that would be typical in English argumentative writing. This self-evident underuse of inferential DMs in the data under consideration indicates that the learners had insufficient knowledge as such DMs are crucial in texts with argumentative mode. That is, it may be argued that inferential DMs are the most difficult to learn by Jordanian EFL learners.

A closer analysis of the individual DMs used in the argumentative texts written by sophomores and seniors revealed that the most commonly used DMs across both groups of learners were ‘and’ (36.1%) (23.2%), ‘because’ (14.2%) (10.6%), and ‘but’ (9.6%) (9%), respectively. There were no differences in the frequency order of these three DMs between the two groups of leaners. However, they displayed some differences in the number of their occurrence in each group. As shown in Table 3 , ‘and’ as an elaborative DM was employed less frequently by the seniors (23.2%) than the sophomores (36.1%). Although this shows that both groups overused this DM at the expense of other DMs, the seniors showed less dependence on this marker in favor of other DMs, which reflects some improvement of their use of DMs, compared to their counterparts. While ‘because’ made a percentage of 14.2% in the sophomores’ writing, it had less percentage in the seniors’ writings (10.6). For the last highest DMs in the data, the contrastive ‘but’, it was equally used by both groups (9.6% by the sophomores and 9% by the seniors). Other DMs occurred by far less frequently such as ‘however’, ‘on the other hand’, and ‘furthermore’. Moreover, there are some DMs that were rarely used by both groups of learners (e.g., ‘although’, ‘yet’, ‘besides’, ‘furthermore’) or were only used by one group (‘as a result’, ‘therefore’, ‘after all’). Remarkably, it was found that an array of manifold DMs was never used neither by the sophomores nor by the seniors (e.g., ‘hence’, ‘nonetheless’, ‘nevertheless’, ‘despite’, ‘on the contrary’, ‘consequently’, ‘since’, ‘in other words’). This can be interpreted that EFL learners tend to rely more on DMs familiar to them from an early stage (Paquot, 2014 ). Such findings are in agreement with Alghamdi ( 2014 ) that in each DM category, there are explicit overuse and underuse of some DMs in EFl argumentative writings.

On the ground of these results, it is justifiable to infer that since both groups of learners in this study utilized frequently a very limited number of DMs in their argumentative texts, they had a poor proficiency level of using DMs, compared to higher proficient L1/ L2 writers (Zhang, 2021 ). The importance of such findings stems from the fact that the quality of academic writing can be evaluated based on lexical variety (Hinkel, 2004 ).

Research question 2

Are there any significant differences between sophomores and seniors in the use of dms in their writing.

To address the second question of the present study, an independent-samples t -test was undertaken in order find whether there is any statistically significant difference between the sophomores and the seniors’ use of DMs in their argumentative written texts. As displayed in Table 4 , the results of the respective test revealed no statistically significant difference between the sophomores ( M = 69.17, SD = 72.07) and seniors ( M = 64.50, SD = 54.29) in their use of DMs in argumentative papers; t (10) = 0.126, p = 0.901.

More elaborately, the total occurrences of the DMs found across argumentative compositions written by the two groups in this study was 802, as clearly illustrated in Table 5 below, where they had a frequency of 415 occurrences in the sophomores’ texts and 387 occurrences in the seniors’ texts. It can be seen that the frequency of DMs in the sophomores’ compositions was slightly higher than the seniors’. The present study conducted a lexical density test (a test used to measure the proportion of the content (lexical) words over the total words) to measure the proportion of the DMs to the total number of words (the total number of words in the sophomores and seniors’ data is 8549 and 8991, respectively) in the argumentative data under examination. The numerical results displayed that the lexical density (LD), which refers to the proportion of DMs to the total number of words, is 4.8% in the sophomores’ writings and 4.3% in the seniors’ writings. It has been reported that the density of DMs and quality of writing are positively related in EFL learners’ compositions (Martínez, 2016 ). In this regard, the current results can, to some degree, may indicate that the participants showed a low proficiency in writing their argumentative texts. A number of studies report that more proficient learners tend to use an increased amount of DMs in their written texts (see Uzun, 2017 ).

Research question 3

Is there any correlation between the number of dms employed in the text and the quality of writing.

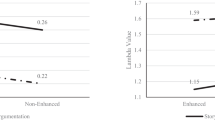

With regard to the last question of the study concerning the relationship between the frequency of DMs and the quality of writing, a Pearson’s r correlation test was carried out to assess this relationship. As illustrated in Table 6 , the results displayed that the correlation between the frequency of DMs employed in the argumentative compositions written by the sophomores and their evaluation was weakly positively correlated, r (58) = .32, p = 0.012. Likewise, the frequency of DMs and the evaluation of the seniors’ writings were found to be weakly positively correlated, r (58) = 0.42, p < 0.001. Based on the results obtained from the present correlation test, it can be stated that a positive correlation but significant (the sophomores 0.012656 and the seniors .000764) was found between the total use of DMs and the quality writing of the argumentative texts written by the participants of the present study. It can be suggested that the highly-rated argumentative compositions tend to employ more DMs than did their poorly-rated counterparts.

Although the results of the present study revealed that there was a positive correlation between the two values at issue, the relationship between the frequency of DMs and the evaluation was weak (for the nearer the value is to zero, the weaker the relationship). However, we can infer that the frequency of DMs can be, to some extent, a potential predictor/ indicator of writing quality, that is, the higher the number of DMs, the better the quality of writing. Such findings are in line with the studies that support the existence of a positive correlation between the deployment of DMs and the quality of writing (Jin, 2001 ; Liu and Braine 2005 , Yang and Sun 2012 ). This implies that EFL learners of both groups in this study still face some difficulties in using DMs in their argumentative writing. The absence of significantly positive correlations between the quality of writing and the frequency of DMs in the respective argumentative texts reflects the students’ low-level proficiency in employing DMs.

However, it should be borne in mind that correlational tests do not always suggest causation- that when two variables in tandem do not necessarily indicate that one variable is affecting the other. (Bruce &. Harper, 2012 ).

The present study examined the use of DMs in argumentative writing by the seniors and sophomores majoring in English at the Hashemite university. These two groups of EFL learners represented two different level of proficiency. The findings revealed both groups used the same types of DMs with varying degree of frequency: elaborative, contrastive, reason, inferential, conclusive, and exemplifier. The seniors were found to employ more slightly DMs than did the sophomores, which may be a result of overusing some DMs and unnecessary instances of DMs. There was no statistically difference in the frequency of DMs by both groups.

The types of DMs that appeared commonly were elaborative, contrastive and reason. However, conclusives and exemplifiers were infrequently used. Across the both group of data, the elaborative type of DMs was the predominate. The analysis of individual DMs reported that the DMs ‘and’, ‘because’, and ‘but’ were the most widely used in both groups. It also reported that both groups over-relied on a very limited number of DMs in their argumentative writing at the expense of other DMs, which reflects a low proficiency in using DMs.

Moreover, there are some DMs that were rarely used by both groups of learners (e.g., although, yet, besides, furthermore) or were only used by one group (as a result, therefore, after all). Remarkably, it was found that an array of manifold DMs was never used neither by the sophomores nor by the seniors (e.g., hence, nonetheless, nevertheless, despite, on the contrary, consequently, since, in other words).

The findings indicated that there was a weak positive but significant correlation between the use of DMs and the quality of writing in both argumentative texts written by the sophomores and seniors.

Pedagogical implications

Based on the present findings on the use of DMs in the sophomore and seniors’ argumentative writings, some pedagogical implications can be highlighted. As we have seen, the use of DMs in argumentative writings presents a challenge to EFL learners across different levels of proficiency. Moreover, the analysis reveals that EFL learners demonstrate little variety in the use of DMs.

The inappropriate use of DMs should be attended to by both instructors and learners. More focus should be placed on DMs and students should be exposed to more varied DMs. In other words, instructors of English should familiarize their students with a wide variety of DMs and encourage learners to vary in their choice of DMs in their writings rather than relying on restricted range of DMs. To increase the quality of EFL argumentative writing, learners should be given more exercises on the functions of DMs and their role in creating and maintaining the cohesion and coherence of text, especially, in academic writing (For details, see Guba et al., 2021 ). This would help in the development of the EFL learners’ writing proficiency.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abdalhadi H, Al-Khawaldeh N, Al Huneety A, Mashaqba B (2022) A corpus-based pragmatic analysis of jordanian’s Facebook status updates during COVID-19. Ampersand, 100099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2022.100099

Aidinlou NA, Mehr HS (2012) The effect of discourse markers instruction on EFL learners’ writing. World J Educ 2(2):10–16

Article Google Scholar

Aijmer K (2002) English discourse particles: evidence from a corpus. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Aijmer K (2015) Analyzing discourse markers in spoken corpora: actually as a case study. In: Baker P, McEnery T (eds) Corpora and discourse studies. Palgrave Macmillan, London, p 88–109

Alattar F, Abu-Ayyash E (2020) The use of conjunctive cohesive devices in Emirati students’ argumentative essays. Br J English Linguist 8(1):9–25

Google Scholar

Alghamdi EA (2014) Discourse markers in ESL personal narrative and argumentative papers: a qualitative and quantitative analysis. Int J Humanit Soc Sci 4(4):294–305

Ali E, Mahadin R (2015) The use of interpersonal discourse markers by students of English at the university of Jordan. Arab World English Journal 6(7):306–319

Alkhawaldeh A (2018) Discourse functions of Kama in Arabic journalistic discourse from the perspective of rhetorical structure theory. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature 7(3):206–213

Al-Khawaldeh, Asim (2018) Uses of the discourse marker wallahi in Jordanian spoken Arabic. A pragma-discourse perspective. International Journal of Humanities and Social sciences 8(6):114–123

Altenberg B, Tapper M (1998) The use of adverbial connectors in advanced Swedish learners’ written English. In: Granger S (ed) Learner English on computer. Addison Wesley Longman Limited, Harlow, p 80–93

Altunay D (2009) Use of connectives in written discourse: a study at an ELT Department Turkey. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Anadolu University

Andersen G (2000) Pragmatic markers and sociolinguistic variation: a relevance-theoretic approach to the language of adolescents. Benjamins, Amsterdam

Arabi H, Ali N (2014) ‘Explication of conjunction errors in a corpus of written discourse by Sudanese English majors’. Arab World Engl J 4(5):111–130

Asassfeh SM, Alshboul SS, Al-Shaboul YM (2013) Distribution and appropriateness of use of logical connectors in the academic writing of Jordanian English-major undergraduates. J Educ Psychol Sci 222(1259):1–46

Beeching Kate (2016) Pragmatic markers in British English—meaning in social interaction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Blakemore D (2002) Relevance and linguistic meaning: the semantics and pragmatics of discourse markers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bruce T, Harper B (2012) Conducting educational research. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc, New York

Chapetón Castro CM (2009) The use and functions of discourse markers in EFL classroom interaction. Profile Issues Teach Prof Dev 11:57–78

Daif-Allah AS, Albesher K (2013) The use of discourse markers in paragraph writings: the case of preparatory year program students in Qassim University. Engl Lang Teach 6(9):217–227

Djigunović M, Vikov Gloria (2011) Acquisition of discourse markers: evidence from EFL writing. Seraz 55:255–278

Doró K (2016) Linking adverbials in EFL undergraduate argumentative essays: a diachronic corpus study. In: Lehmann M, Lugossy R, Horváth J (eds) Empirical studies in English applied linguistics. Lingua Franca Csport,University of Pecs, p. 152–165

Eemeren F (2021) Characterizing argumentative style: the case of KLM and the destructed squirrels; In: Boogaart R, Jansen H, Van Leeuwen M (eds) The language of argumentation. Springer, Switzerland

Erman B (1987) Pragmatic expressions in English: a study of you know, you see and i mean in face-to-face conversation. Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm Studies in English 69. Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm

Fedriani C, Sansó A (2017) Pragmatic markers, discourse markers and modal particles: new perspectives. John Benjamins Publishing company, Amsterdam/Philadelphia

Foolen A (1996) Pragmatic particles. In: Verschueren J. et al. (eds) Handbook of pragmatics. Benjamins, Amsterdam

Fraser B (1999) What are discourse markers? J Pragmatics 31(7):931–952

Fraser B (2006) Towards a theory of discourse markers. In: Kerstin F(ed) Approaches to discourse particles. Elsevier, Amsterdam, p 189–204

Fung L, Carter R (2007) Discourse markers and spoken English: Native and learner use in pedagogic settings. Applied Linguistics 28:410–439

Ghanbari N, Dehghani T, Shamsaddini MR (2016) Discourse markers in academic and non-academic writing of Iranian EFL Learners. Theory Pract Lang Stud 6(7):1451–1459

González M (2004) Pragmatic markers in oral narrative: the case of english and catalan. Benjamins, Amsterdam

Guba MNA, Mashaqba B, Huneety A, AlHajEid O (2021) Attitudes toward Jordanian Arabic-accented English among native and non-native speakers of English. ELOPE: English Language Overseas Perspectives and Enquiries 18(2):9–29

Hamed M (2014) ‘conjunctions in argumentative writing of Libyan tertiary students’. Engl Lang Teach 7(3):108–120

Heine B, Kaltenböck G, Kuteva T, Haiping L (2021) The rise of discourse markers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hinkel E (2004) Teaching Academic ESL writing: Practical techniques in vocabulary and grammar. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, United States of America

Huneety A, Mashaqba B, AlOmari M, Zuraiq W, Alshboul S (2019) Patterns of lexical cohesion in Arabic newspaper editorials. Jordan Journal of Modern Languages and Literature 11(3):273–296

Huneety A, Mashaqba B, Al-Shboul SSY, Alshdaifat, A T (2017) A contrastive study of cohesion in Arabic and English religious discourse. International Journal of Applied linguistics and English Literature 6(3):116–122

Jalilifar A (2008) Discourse markers in composition writings: the case of Iranian learners of english as a foreign language. Engl Lang Teach 1(2):114–122

Jin W (2001) A Quantitative study of cohesion in Chinese graduate students’ writing: variations across genres and proficiency levels. Paper presented at the Symposium on Second Language Writing at Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana

Jucker A (1997) The discourse marker well in the history of english. Engl Lang Linguist 1:1–110

Kalajahi S, Abdullah ANB, Baki R (2012) Constructing an organized and coherent text: how discourse markers are viewed by Iranian post-graduate students. Int J Humanit Soc Sci 2(9):196–202

Lenk U (1998) Discourse markers and global coherence in conversation. J Pragmatics 30:245–257

Lewis DM (2003). Rhetorical motivations for the emergence of discourse particles, with special reference to English of course. In: van der Wouden T, Foolen A, Van de Craen P (eds) Particles. Belgian J Linguist 16:79–91

Liu M, Braine G (2005) Cohesive features in argumentative writing produced by Chinese undergraduates. System 33(4):623–636

Martinez AC (2016) Conjunctions in the writing of students enrolled on bilingual and non-bilingual programs. Revista de Educación 371:100–125

Martínez ACL (2004) Discourse markers in the expository writing of Spanish university students. Ibérica: Revista de la Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos (AELFE) 8:63–80

Mauranen A (1993) Cultural differences in academic rhetoric. A textlinguistic study. Peter Lang, Frankfurt/Main

Müller S (2005) Discourse markers in native and non-native English discourse. John Benjamins Publishing Co, Amsterdam

Olmen D, Šinkūnienė J (2021). Pragmatic markers and peripheries. Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing company

Paquot M (2014) Academic vocabulary in learner writing: from extraction to analysis. Continuum, London

Povolná R (2012) Causal and contrastive discourse markers in novice academic writing. Brno Studies in English. 38(2):131–148

Rahimi M (2011) Discourse markers in argumentative and expository writing of Iranian EFL learners. World J Engl Lang 1(2):68

Redeker G (2006) Discourse markers as attentional cues at discourse transitions. In: Fischer K (ed) Approaches to discourse particles. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 339–358

Sanczyk A (2010) Investigating argumentative essays of English undergraduates studying in Poland as regards their use of cohesive devices. M.A thesis, University of Oslo

Schiffrin D (1987) Discourse markers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Siepmann D (2005) Discourse markers across languages: a contrastive study of second-level discourse markers in native and non-native text. Routledge, New York

Tapper M (2005) Connectives in advanced Swedish EFL learners’ written English-preliminary results. Working Papers Engl Linguist 5:116–144

Taweel A (2020) Discourse markers in the academic writing of Arab students of English: a corpus-based approach. Theory Pract Lang Stud 10(5):569–575

Traugott EG (1995) The role of the development of discourse markers in a theory of grammaticalization. Paper given at the 12th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Manchester, 13–18 August

Uzun K (2017) The use of conjunctions and its relationship with argumentative writing performance in an EFL setting. J Teach Engl Spec Acad Purposes V5(N2):307–315

Yang W, Sun Y (2012) The use of cohesive devices in argumentative writing by Chinese EFL learners at different proficiency levels. Linguist Educ 23(1):31–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2011.09.004 . MarchppScienceDirect

Article CAS Google Scholar

Zhang Y (2021) Adversative and concessive conjunctions in EFL writing. Springer, Singapore

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Arts, The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan

Anas Huneety, Bassil Mashaqba & Zainab Zaidan

Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Al-alBayt University, Mafraq, Jordan

Asim Alkhawaldeh

Mohammed Bin Zayed University for Humanities, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Abdallah Alshdaifat

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Asim Alkhawaldeh .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The methodology for this study was approved by Research Ethics Panel of the Hashemite University (Ethics approval number:1/2022/2023).

Informed Consent

Voluntary informed consent was obtained from all participants after we made sure that they were aware of the process in which they were involved. The participants were fully informed of the aims of the task and that their written texts would be only used for research purpose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Huneety, A., Alkhawaldeh, A., Mashaqba, B. et al. The use of discourse markers in argumentative compositions by Jordanian EFL learners. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 41 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01525-0

Download citation

Received : 03 June 2022

Accepted : 17 January 2023

Published : 30 January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01525-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Unpacking the function(s) of discourse markers in academic spoken English: a corpus-based study

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 17 May 2022

- Volume 45 , pages 49–70, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mehrdad Vasheghani Farahani 1 &

- Zahra Ghane 2

6892 Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Discourse markers can have various functions depending on the context in which they are used. Taking this into consideration, in this corpus-based research, we analyzed and unveiled quantitatively and qualitatively the functions of four discourse markers in academic spoken English. To this purpose, four discourse markers, i.e., “I mean,” “I think,” “you see,” and “you know,” were selected for the study. The British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus was used as the data gathering source. To detect the discourse markers, concordance lines of the corpus were carefully read and analyzed. The quantitative analysis demonstrated that from among the four discourse markers, “you know” and “you see” were the most and the least frequent ones in the corpus, respectively. In line with the quantitative analysis, the qualitative analysis of the concordance lines demonstrated that there were various functions with regard to each of the four discourse markers. The findings of this study can have implications in fields such as corpus-based studies, genre analysis, and contrastive linguistics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Frequency and Stylistic Variability of Discourse Markers in Nigerian English

Analysing Discourse Markers in Spoken Corpora: Actually as a Case Study

“Well (er) You Know …”: Discourse Markers in Native and Non-native Spoken English

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Discourse markers have been an intriguing topic of research in pragmatics. They play a pivotal role in pragmatic competence of speakers (Müller, 2005 ; Lam, 2009 ; Öztürk & Durmuşoğlu Köse, 2020 ) and will help them to make their speech more comprehensible and rich (Crozet, 2003 ) as well as more sociable (Weydt, 2006 ). In addition, discourse markers perform various functions relating to turn taking management as well as speaker-audience relationship (Crible, 2017 ) as they are defined and detected mostly by the various functions they (can) perform (Aijmer, 2013 ).

The concept of discourse markers has intrigued researchers to investigate their different forms and functions in speech and writing. Indeed, the interest in studying discourse markers stems from the fact that they are pragmatically variant or multifunctional (Schleef, 2005 ; Lee, 2017 ). This wide range of functions have resulted into the introduction of various terminologies such as sentence connectives (Fraser, 1999 ; Halliday & Hasan, 1976 ), discourse particles (Schourup, 1985 ), discourse signals (Lamiroy & Swiggers, 1991 ), discourse connectives (Unger, 1996 ), discourse particles (Aijmer, 1997 , 2002 ), speech act adverbials (Aijmer, 1997 ), discourse operators (Gaines, 2011 ), thetical features (Heine et al., 2016 ), pragmatic markers (Brinton, 2017) and metadiscourse features (Hyland, 2004 , 2019 ).

In line with these various terminologies, there is a range of homogenous definitions. To name a few, Hyland ( 2004 ) defines discourse markers as “a self-reflective linguistic expression referring to the evolving text, to the writer, and to the imagined readers of that text” (p. 133). In the same line, Vande Kopple ( 2012 ) defines these features as “elements of texts that convey meanings other than those that are primarily referential” (p.37). In another definition, Ädel (2010) defines discourse markers as “reflexive linguistic expressions referring to the evolving discourse itself or its linguistic form, including references to the writer-speaker qua writer-speaker and the (imagined or actual) audience qua audience of the current discourse” (p.75).

Discourse markers have specific characteristics, which make them distinguished from other linguistic elements. As an example, Hyland ( 2019 ), while referring to metadiscourse markers as the terminology, assigns three distinguishing roles to them: these features must be distinguished from propositional aspects of meanings because they are inherently non-propositional; they consider those aspects of discourse which are used to establish writer-reader and/or speaker-audience interaction; and they can have various functions in different contexts.

The term “discourse marker” has been the subject of a range of studies over the last decades. It can have miscellaneous functions, extending from signals, which function as hesitation filters, to clausal expressions, which are frequently used and found in spoken interactions. There are some studies focusing on the multifunctionality of discourse markers such as Mauranen ( 2001 ), Thompson ( 2003 ), Farrokhi and Ashrafi ( 2009 ), Crismore and Abdollahzadeh ( 2010 ), Letsoela ( 2014 ), Ma and Wang ( 2015 ), Ghasemali and Azizeh ( 2017 ), Akbas and Hardman ( 2018 ), Hajimia ( 2018 ), and Jalilifar ( 2008 ). These studies studied various discourse markers from different perspectives such as genre, language variations, grammaticalization, and native and non-native language.

Language as a means of communication plays a significant role in everyday life because “all people use spoken language to interact with one another” (Zarei & Mansoori, 2007 ; Povolná, 2010, p.23). Although spoken and written languages are interdependent (Townend & Walker, 2006 ), spoken language has some specifications which make it different from written language. Cook ( 2004 ) accentuates the differences between spoken and written forms of language by saying that “Many of the devices of written language have no spoken equivalent” (p. 12) which can be the result of differences in the mode or in the context of usage. In this regard, one difference is that unlike the written form, spoken language does not have the opportunity for self-revision and editing on the spot (Crawford & Csomay, 2016). Another difference is the matter of formality in speech versus written modes, meaning that in spoken mode, there are more instances of informality.

A detailed look at the literature review supported this idea that there was a lack of research in the area of discourse markers in spoken language, despite the fact that in written language, there were a plethora of studies (see, for example, Erman, 2000 ; Chapetón & Claudia, 2009 ; Kohlani, 2010 ; Ismail, 2012 ; Sharndama & Yakubu, 2013 ; Dylgjeri, 2014 ; Piurko, 2015 ; Crible et al., 2019 ). This can be due to the fact that collecting spoken data, as compared to written data, is a more overwhelming issue, which requires too much budget and time (Burnard, 2002 ).

Despite the lack of solid research in spoken discourse with the exploitation of large corpora, in one of the rare studies, Huang ( 2011 ) studied the spoken discourse markers between Chinese non-native speakers (NNSs) of English and native speakers (NSs). Using linear unit grammar analysis and text-based analysis and applying SECCL, MICASE, and ICE-GB corpora, the results of this corpus-based research showed that discourse markers such as “like,” “oh,” “well,” “you know,” “I mean,” “you see,” “I think,” and “now” are found more frequently in dialogue genres as compared to monologue genres in spite of the similarities found between NNSs and NSs. In addition, the results of this research showed that discourse markers correlate with context, type of activity, and identity of the speakers.

In another related research, Novotana ( 2016 ) studied the role of discourse markers as well as their functions in spoken English. For this purpose, he chose 19 discourse markers such as “I see,” “you know,” “I mean,” “actually,” and “really,” among others. The analysis of his corpus demonstrated that not only do discourse markers play a pivotal role in English spoken mode, but also they can have various functions, depending on the intention of the speaker(s) and the context of usage.

In addition, Kizil ( 2017 ) studied the function and frequency of discourse markers in learners’ spoken interlanguage of EFL learners. With two corpora of reference and learner, he showed that as far as audience interaction is concerned, non-native speakers used fewer discourse markers as compared to native speakers, which can be attributed to their unawareness of the significant role of discourse markers.

In the same vein, Resnik ( 2017 ) investigated the function and distribution of discourse markers (metadiscourse features) in spoken interaction as a strategy for compensating miscommunication among multilingual speakers who communicate in their L2 (English). For this objective, she conducted 27 interviews for creating a corpus of spoken English. The analysis showed that L2 speakers of English employ metadiscourse features as a means of enhancing mutual understanding and that depending on the situation, they bear different functions.

In the same vein, Jong-Mi ( 2017 ), investigated the multifunctional nature of “Okay” as a discourse marker used by Korean EFL (English as a foreign language) teachers in their naturally occurring discourses of EFL classes. The data gathered from video recordings of six Korean teachers demonstrated that discourse marker “Okay” can take three different roles as “getting attention”, “signaling approval and acceptance as a feedback device,” and “working as a transition activator.”

In a recent study, Banguis-Bantawig ( 2019 ) investigated the functions of discourse markers in speeches of selected Asian Presidents. Adapting the discourse theory of Hassan and Halliday and de Beaugrande and Dressler in analyzing 54 English speeches of Presidents in Asia, he showed that there were three pivotal roles in relation to discourse markers used by presidents including adding something to the speech, cohesion, and substitution.

A look at the above-mentioned studies indicated that they were mostly limited to small-scaled corpora, jeopardizing the generalizability of their results as well as corpus representativeness. Moreover, the review of the related literature showed that the studies in this area of research lacked the exploitation of large, balanced, and representative corpora in spoken discourse. Consequently, based on the insight gained from literature review and due to the research aims, this study was an effort to fill out this less researched gap and area of research by addressing these two questions: (1) How were the above-mentioned discourse markers used and distributed in the British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus and which discourse marker was the most frequent one? and (2) Which functions did these discourse markers have in the context of use in spoken discourse? The null hypothesis of this study was that there was no difference in terms of discourse marker distribution in the corpus of the study and that there was no difference in terms of the function(s) of the discourse markers in the corpus of the study.

2 Theoretical framework

The framework of the present study is Discourse Grammar (Kaltenböck et al., 2011 ) which as proposed by Heine et al. ( 2013 , 2020 ) rose out of the analysis of spoken and written linguistic discourse on the one hand and of the work conducted on thetical expressions on the other. In other words, it is based on the distinction between two organizing principles of grammar where one concerns the structure of sentences (sentence grammar) and the other the linguistic organization beyond the sentence (thetical grammar). The term theticals, including DMs, is sometimes used interchangeably with extra-clausal constituents (ECC) or parentheticals (see Dik, 1997: 379–409) and encompasses various constituents such as vocatives, imperatives, social exchange formulae, interjections, and conceptual theticals.

Discourse Grammar is a relatively new framework providing a detailed description and explanation of DMs, their functions, and evolution. Accordingly, the thetical grammar is based on the speaker’s communicative intents and the knowledge of discourse processing at a higher level, relating the text to the situation of discourse. The situation of discourse refers to the cognitive frame used by interlocutors to construct and interpret spoken or written texts; it is delimited by three components, namely, (i) text organization, (ii) attitudes of the speaker, and/or (iii) speaker-hearer interact. The last two are sometimes called interpersonal [or modal] functions and relate, respectively, to the terms “subjectivity” and “intersubjectivity” (Heine et al., 2020 ).

In this framework, a distinction is provided between two organizing principles of grammar, where one concerns the structure of sentences (sentence grammar) and the other the linguistic organization beyond the sentence (thetical grammar). Kaltenböck et al. ( 2011 ) and Heine ( 2013 ) have introduced the specification in (1) to describe a prototypical thetical.

Theticals are (a) invariable expressions which are (b) syntactically independent from their environment, (c) typically set off prosodically from the rest of the utterance (which can be marked by comma in writing), and (d) their function is to relate an utterance to the situation of discourse, that is, to the organization of texts, speaker-hearer interaction, and/or the attitudes of the speaker (Heine, 2013 , p. 1211).

3 Procedure and detection of the discourse markers

This study privileged both quantitative and qualitative phases. In the quantitative study, the frequency of the detected discourse makers was calculated through the statistical procedures and in line with the criteria mentioned above. In the qualitative phase, the extracted concordance lines were scrutinized to unveil the function(s) of the detected discourse markers. Accordingly, an array of steps was taken for the issue of feasibility. First, we scrutinized the whole corpus of the study, through the concordance lines and CQL (Corpus Query Language) technique in Sketch Engine Corpus Software to detect the tokens of discourse markers. In order to distinguish discourse markers from other types of non-prepositional elements, we exploited the criteria set by Kaltenböck et al. ( 2011 ) as come in (1).

Following the conditions, four discourse markers were selected in this study including “I mean,” “you know,” “you see,” and “I think.” These were selected due to their higher frequency and dispersion in the corpus and due to their similarity that is all can be followed by the complementizer “that” in the level of sentence grammar. In other words, they were among the most frequent discourse markers in the corpus, and they can receive a subordinate clause when used as an intendent clause. Table 1 shows the frequency of discourse markers of the study. It is worth mentioning that in order to be able to unpack the function(s) of these discourse markers, we analyzed the linguistic context surrounding the discourse marker as well as the topic of the discussion. It should be noted that it is problematic to intuitively interpret the functions of discourse markers, as most previous studies have done, because a researcher cannot read a speaker’s mind; in most cases, the uses of DMs are not even easily available to introspection by the speaker. As a result, this study used the immediate context and the co-occurrence phenomena to categorize the uses of discourse markers and to clarify the logic of the identification of their functions. However, occasionally more than one type of co-occurrence is found in the same instance. In cases of this kind, the classification has to be confirmed by the use of other discourse markers in the context.

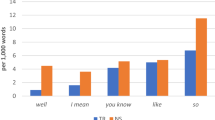

Table 1 shows the type and frequency of the discourse markers of the study. As can be seen, from among 4 types of discourse markers, “I mean” had 1888 frequency. Then, was “I think” discourse marker with 2940 tokens, followed by “you know” with 3569 tokens and “you see” with 506 tokens. On aggregation, there were 8903 tokens of the 4 discourse markers in the corpus.

4 Corpus of the study

Rather than the rudimentary and time-consuming process of detecting the existing similarities and differences out of the immediate context, researchers resort corpora to explore the differences and similarities of a language(s) in the immediate context of use (Zanettin et al., 2003 ; Anderman & Rogers, 2008 ; Candel-Mora & Vargas-Sierra, 2013 , Milagrosa Pantaleon, 2018 ). As a matter of fact, comparing to extract and analyze language features manually which is not only time-consuming but also subject to error (Anthony, 2009 ), one plausible way is to apply corpora defined as “an electronically stored, searchable collection of texts” (Jones & Waller, 2015 , p.6). Corpora are useful in that they can give the researcher(s) a quick access to the word/phrase as well as to the context in which it is used (Anderman & Rogers, 2008 ). As a result, having access to a representative and balanced corpus that could meet the requirements of the study was an integral part of this research (Heng & Tan, 2010 ).

As creating a Do It Yourself (DIY) corpus was inherently an arduous task and was beyond the scope of the current research, we decided to employ already compiled and available corpora. There are a number of various academic spoken corpora such as the Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English (Nesi & Thompson, 2006 ) and Hong Kong Corpus of Spoken English (Cheng & Warren, 1999 ); however, from among these spoken corpora, the one, which was exploited in this study, was “The British Academic Spoken English (BASE) corpus.” The reason why this corpus was used was due to its availability in Sketch engine corpus software and its fitness to this study. This corpus was compiled at the Universities of Warwick and Reading out of 160 lectures and 39 seminars video recorded from 2000 to 2005. The male and female speakers were both native and non-native speakers of English (Thompson & Nesi, 2001 ). As its name implies, it is narrowed down to academic genre and contains such fields of studies as arts and humanities, life and medical sciences, physical sciences, and social studies and sciences. The corpus contains 1,756,545 words and 1,477,281 sentences. This specialized, representative, and balanced corpus, which was tagged at part of speech (POS), was used in this research to be in line with the research boundary of the study in hand.

5 Quantitative analysis

This study was done in two phases of quantitative and qualitative analysis. As for the quantitative analysis, the frequency of each of the discourse markers was calculated separately through the whole corpus. The results are presented in the following tables. The data analysis was done through SPSS version 26.

Table 2 demonstrates the frequency of discourse markers in the corpus. As can be seen, there were 8037 tokens of discourse markers from among which “you know” was the most frequent one with 3188 tokens followed by “I think” and “I mean” with 2578 and 1786 tokens. The least frequent type of discourse marker was “you see” with only 485 tokens.

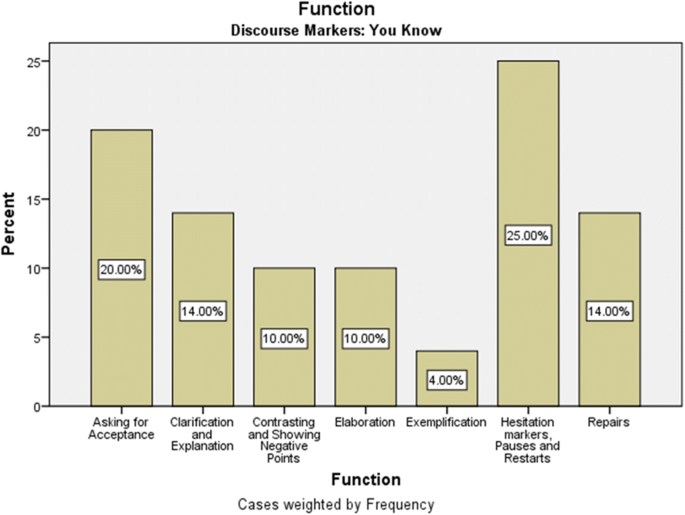

Figure 1 shows the functions of the “you know” discourse marker. As can be seen from among seven functions, hesitation markers and asking for acceptance were the two most frequent functions with 25% and 20%, respectively, followed by clarification function and repairs as the third used discourse markers (14%). Next were contrastive function and elaboration function with 10% followed by exemplification as the least frequent function (4%).

Functions of “you know” discourse marker

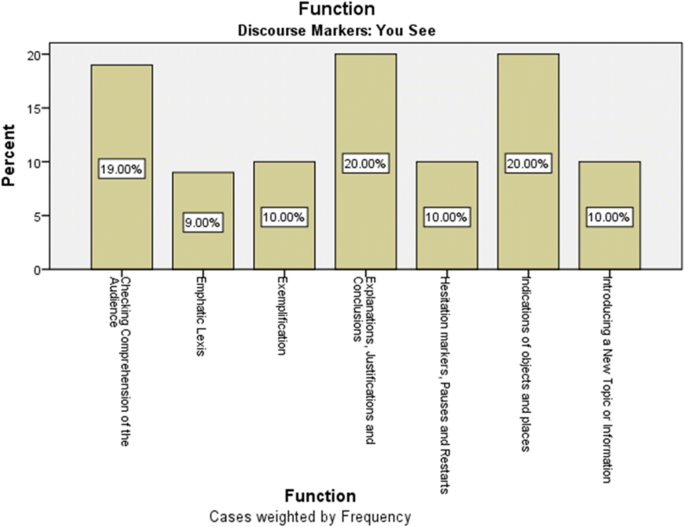

Figure 2 indicates the functions of “you see” discourse marker. As can be seen, from among these functions, indication of objects and explanations were the most frequent discourse markers (20%) followed by checking comprehension as the second most frequent function (19%). With 10%, introducing new topic, hesitation markers, and exemplification were the third most frequent functions. Emphatics function with only 9% was the least frequent function.

Functions of “you see” discourse marker

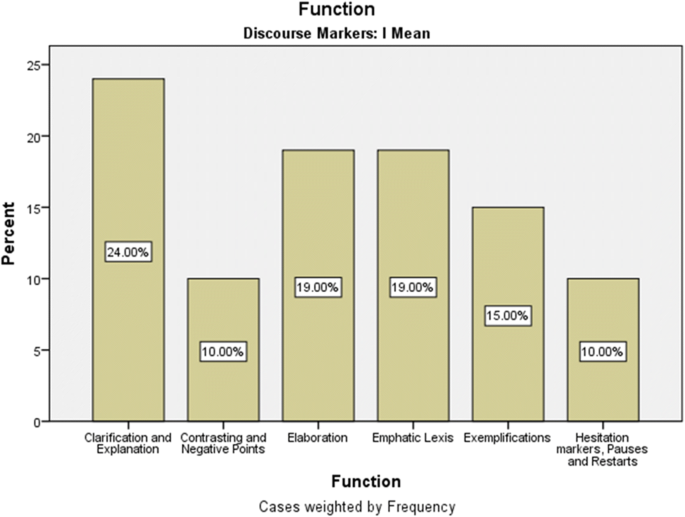

Figure 3 indicates the functions of “I mean” discourse marker with their frequency. As can be inferred, clarification and explanation were the most frequent function with 24% followed by elaboration and emphatic lexis with 19%. In the third rank was exemplification with 15%. The least used functions were hesitation and contrasting ones with 10%.

The functions of “I mean” discourse marker in the corpus

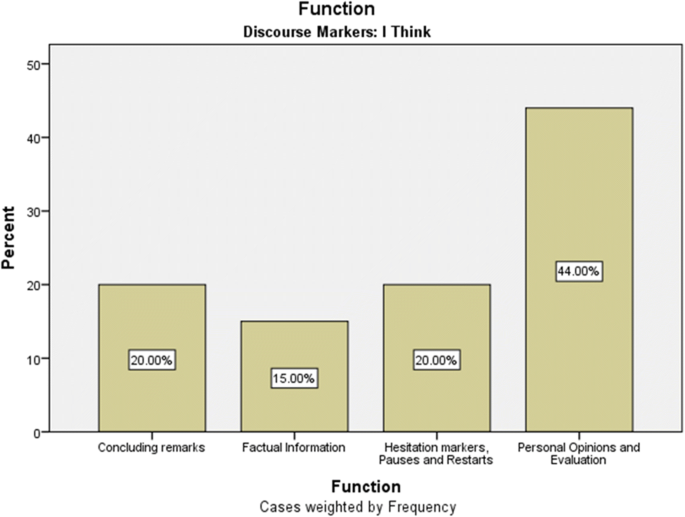

Figure 4 represents the functions of “I think” with four ones. As can be inferred from the figure, personal opinion with 44% was the most frequent function followed by concluding remarks and hesitation remarks as the second most frequent functions (20%). The least used function was factual information with 15%.

The functions of “I think” discourse marker

6 Qualitative analysis

Once the quantitative analysis was done, the qualitative analysis was conducted through close reading of the concordance lines. It is worth mentioning that 30% of the concordance lines were randomly selected through shuffling technique of the corpus software to unpack the functions of discourse markers.

7 Functions of “you know” discourse marker