An Introduction to Zambia's Lozi People

Freelance Writer

The Lozi tribe of Western Zambia are a proud people with a complex history. They are the only tribe in Zambia with a King instead of a chief, and account for approximately 900,000 people. This is an introduction to Zambia’s Lozi people.

According to myth, the Lozi tribe began when the sun god Nyambe descended from heaven onto Barotseland, which is the Lozi homeland. He came with his wife Nasilele (the moon), and together they began the line of Luyi-Luyana kings. Before ascending back to the heavens, they left their daughter Mbuyu to continue the line of leadership through her male offspring.

Another account of the creation of the Lozi tribe is that they came from the Lunda Kingdom in present day Democratic Republic of Congo, and were led into Western Zambia by a Lunda princess called Mbuywamwamba between the 17th and 18th centuries. This was during the Bantu Migration from which other Zambian tribes such as the Bemba also moved into Zambia.

The historical account is that the Lozi were originally called the ‘ Luyi ‘ (meaning ‘Foreigner’) and spoke a language called Siluyana. They lived in Bulozi, a plain in the Upper Zambezi. In 1830, the Luyi people were conquered by the Makololo tribe under a leader called Sebetwane, who was part of many tribes that escaped the Mfecane , a series of wars under the Zulu king Shaka from present day South Africa. The Makololo changed the Luyi’s name to ‘Lozi’, which translates to ‘plain’. Although the Makololo were overthrown in 1864, the Luyi kept their new name.

Political history

It was believed that Barosteland had copper, gold and other minerals, so Cecil Rhodes, a colonialist figure known for his dreams of building a road from Cape Town , South Africa to Cairo, Egypt convinced the Litunga (the King – known by the name Lewanika) to sign over mining rights to Rhodes British South African Company under the Lochner Concession of 1890. Barosteland then became a British protectorate with the Lozis offered protection from neighboring tribes interested in conquering the Lozi. Barotseland became part of Northern Rhodesia (now known as Zambia) in May 1964, five months before Northern Rhodesia became an independent nation.

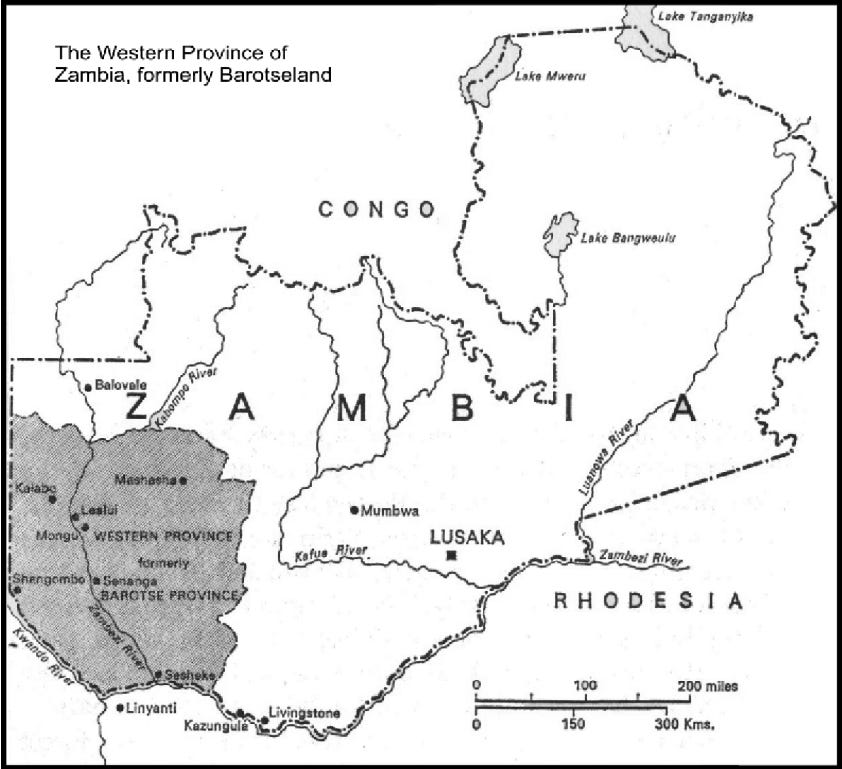

The Lozi are mostly concentrated in the Western Province of Zambia, although they are also based in smaller numbers in the Caprivi strip of Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique and Zimbabwe . The Lozi homeland is called Barotseland, and was once considered to be an independent kingdom with its own flag. The administrative capital is called Lealui, and the winter capital is called Limulunga – the towns are separated by a distance of approximately 11 miles (17.7 km). The town of Mongu is the political capital and is approximately 10 miles (16km) west of Lealui.

The Lozis show respect through a practice called likute . According to the essay ‘Moonlight and Clapping Hands: Lozi Cosmic Arts of Barosteland’ by Karen E Milbourne from the book African Cosmos published by Stellar Arts, it is “the performance of politeness, deference and cooperation… Its most visible feature consists of Lozi men and women clapping their hands in respect to one another, their leaders and the divine”. When members of the Lozi tribe meet the Litunga , they put their arms in the air, recite tributes and kneel several times as a form of respect.

Political structure

The Litunga is known as the ‘holder of the earth’ which is a literal translation of his name. This means all land in Barotseland belongs to the King, and his subjects are granted permission to live on the land. The Litunga is ruler of all Lozis. Under him is his prime minister, the Ngambela. The indunas or councilors are under the prime minister.

Traditional ceremony

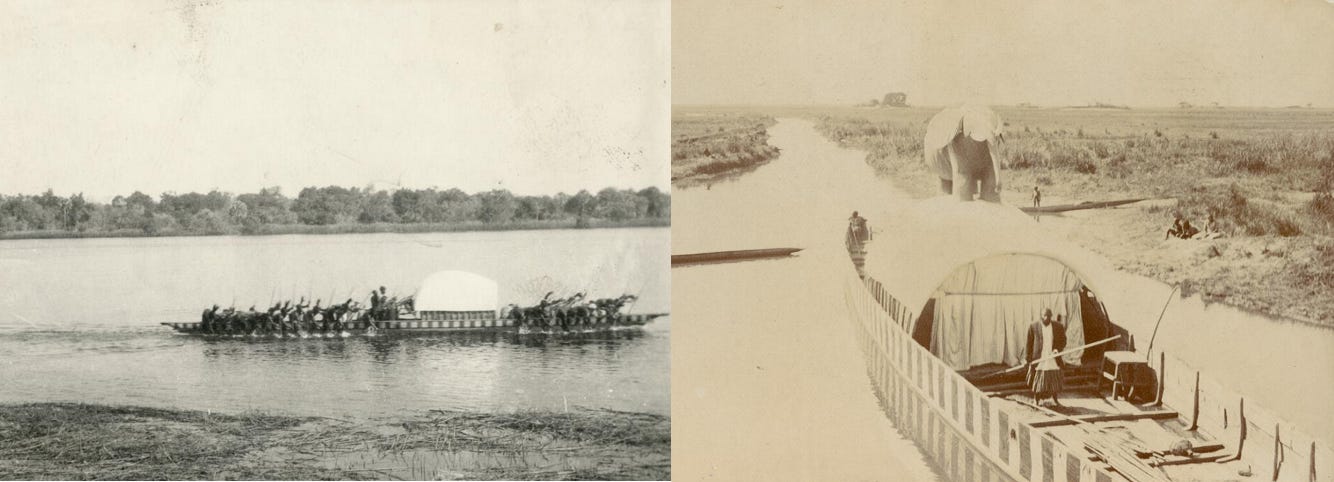

The Lozis celebrate the Kuomboka ceremony annually in March or April at the end of the rainy season. It is one of the most popular traditional ceremonies in Zambia. ‘ Kuomboka ‘ translates to ‘get out of the water’ and involves the Litunga , his Queen and a number of their subjects moving from his residence at Lealui which floods annually, to Limulunga. The journey is a spectacle to watch, with the royal barge called the Nalikwanda (meaning ‘for the people’ which referred to the fact that the boat could be used by anyone, although later it came to be only used for the King) drawing attention with the large model elephant on the top. The Queen travels in a separate barge. The night before Kuomboka, the King beats a royal drum called the maoma which is a call to able-bodied men from the kingdom to prepare to escort their king. “Up to 120 men in leopard skins, red berets and lions manes to lead a flotilla of barges, banana boats and dugout canoes across lilly-studded waters” (Milborune, African Cosmos ).

Other drums that are played during the Kuomboka include the manjabila, lishoma, mwenduko, mutanga. “Manjabila is played in the Nalikwanda to give praises to the former leader of the canoe makers, and it alternates with maoma. Andlishoma is played up to the second landing at the harbour of Limulunga. Mwenduko together with mwatota and ngw’awawa (xylophones) are played while Nalikwanda is leaving. Mutango is played early in the morning to confirm to the people that the Litunga or Litunga la Mboela (The Queen) will not spend the night in Lealui or Nalolo. Firstly it will be played in the courtyard and thereafter at Namoo” (Barotse Royal Establishment, Kuomboka Ceremony, 2008: 14-15).

The Litunga’s traditional attire is called sikutindo, which is worn when boarding the royal barge. He also carries a namaya which is a fly whisk. He then changes into his other royal attire, a black and gold British admiral’s uniform which is said to have been given to the Litunga who was ruling in 1902 by King Edward VIII in recognition of a treaty that had been signed between the Lozis and Queen Victoria.

Male members of Barosteland (the Lozi kingdom) wear a siziba – a skirt which is red, black and white chitenge (a cotton print fabric usually with bold patterns). They wear a matching waistcoat and red beret called a lishushu . The women wear a satin outfit called musinsi which consists of two skirts , a top called a baki and a small wrapper called a chali.

Women and men from the Lozi tribe sometimes wear ivory bangles which are given at different points in life such as birth, puberty etc.

Another way to learn about Lozi culture is to visit the Nayuma Museum which is located opposite the Litunga’s palace in Mongu.

Identity and naming

The Lozi sometimes name their children after former royal leaders. For instance, the name Matauka is usually given to a female child and was the name of the Queen whose brother was the Litunga from 1875 – 1885 and 1886 – 1916. Nasilele is also a common female name and refers to the wife of Nyambe (the sun god) who according to myth founded the Lozi tribe.

Traditionally, the eyes and mouth were kept open at the point of death. Men were buried facing east, while women were buried facing west. The dead were buried with their personal possessions as it was believed that they would be needed in the afterlife. According to the kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane blog , “The grave of a person of status, which is situated to the side of the commoner s cemetery, is surrounded by a circular barrier of grass and branches. As sign of grief, the kin of the deceased wear their skin cloaks inside out. The hut of the deceased is pulled down, the roof being placed near the grave, while the remaining possessions of the dead person are burned so that nothing will attract the ghost back to the village”. The funeral for a deceased King is a more elaborate affair.

The Lozi perform a variety of dances based on occasion. During a girl’s initiation, a dance called siyomboka is performed. It is also the name of the conical drum that is used during the occasion. During royal occasions such as Kuomboka , men and women perform different dances. The ngomalume is a warrior-style dance performed only by men. It “demands skillful co-ordination of steps and the abdominal movements” (Agrippa Njungu, Music of My People (II): Dances in Barotseland ). The liwale is performed by women at royal events. Other dances include the liimba, lishemba and sipelu, which is the most popular.

Like the myth of the creation of the Lozi tribe, there are many others. One of the most fascinating is the myth of the Lengolengole , a creature with the head of a snake and lizard-like feet that lives in the Zambezi river and was said to have been spotted by a Litunga in the early 20th century.

Food and drink

According to a Food and Consumption Report titled ‘ The Common Zambian Foodstuff, Ethnicity, Preparation and Nutrient Composition of selected foods’ by Drinah Banda Nyirenda, Ph.D., Martha Musukwa, MSc. and Raider Habulembe Mugode, BSc, the Lozi ethnic grouping occupy and control access to the floodplain with its potential for cattle production, fishing, wetland/floodplain agriculture (rice and maize), and harvesting of foodstuffs from the natural fauna and flora of the floodplain. The preferred fruits of the Lozi are exotic fruits. Apart from local fruits such as mumbole and namulomo which are preferred for their good taste, the local fruits that are most preferred by the Lozi people are those that have several uses such as mubula, which is used for making porridge, scones called manyende, and a drink known as maheu. Nuts are added as an alternative to groundnuts. Muzauli is added to relishes as an alternative to groundnuts or as a source of cooking oil, and mukuwa may be made into a drink.

The staple food of Zambia nshima is eaten by the Lozi as well, although it is called buhobe .

KEEN TO EXPLORE THE WORLD?

Connect with like-minded people on our premium trips curated by local insiders and with care for the world

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

Africans in Space: The Incredible Story of Zambia’s Afronauts

An Introduction to Zambia’s Kaonde Tribe

Zambian Authors You Should Know

Guides & Tips

Why visiting victoria falls is now easier than ever.

An Introduction to Zambia’s Luvale People

The Ultimate Guide to Rocktober, Zambia

Restaurants

The top 10 restaurants in lusaka, zambia.

The Circus School Empowering Zambia's Children

A Street Art Tour of Lusaka, Zambia

Food & Drink

The 10 best breakfast and brunch spots in lusaka, zambia.

The Most Popular Travel Bloggers From Zambia

See & Do

What you should know about africa's dying ancient baobabs.

- Post ID: 1000224157

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

African History Extra

A history of the Lozi kingdom. ca. 1750-1911.

State and society in south-central africa.

In the first decade of the 20th century, only a few regions on the African continent were still controlled by sovereign kingdoms. One of these was the Lozi kingdom, a vast state in south-central Africa covering nearly 250,000 sqkm that was led by a shrewd king who had until then, managed to retain his autonomy.

The Lozi kingdom was a powerful centralized state whose history traverses many key events in the region, including; the break up of the Lunda empire, the Mfecane migrations, and the colonial scramble. In 1902, the Lozi King Lewanika Lubosi traveled to London to meet the newly-crowned King Edward VII in order to negotiate a favorable protectorate status. He was met by another African delegate from the kingdom of Buganda who described him as "a King, black like we are, he was not Christian and he did what he liked" 1

This article explores the history of the Lozi kingdom from the 18th century to 1916, and the evolution of the Lozi state and society throughout this period.

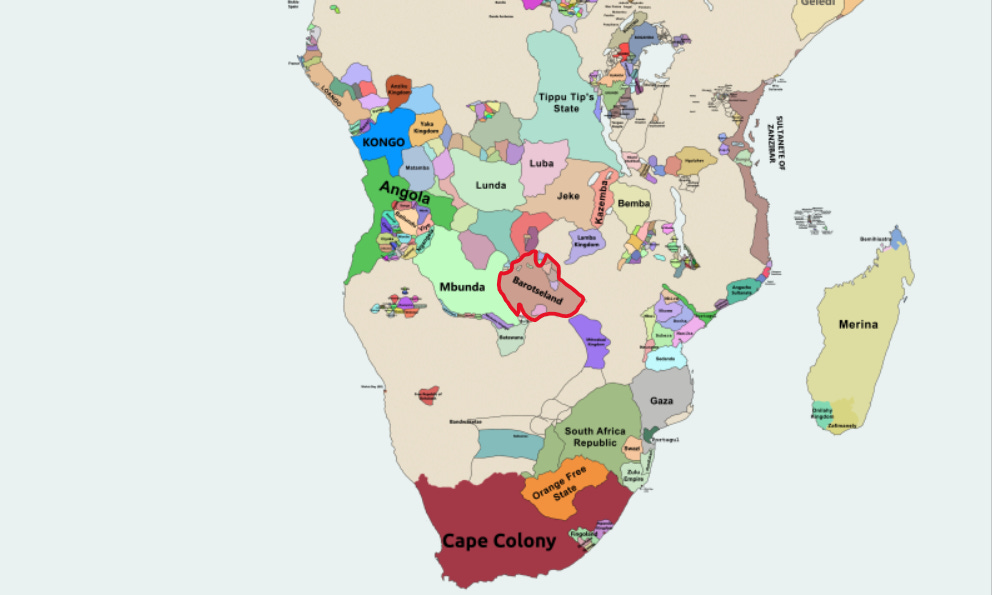

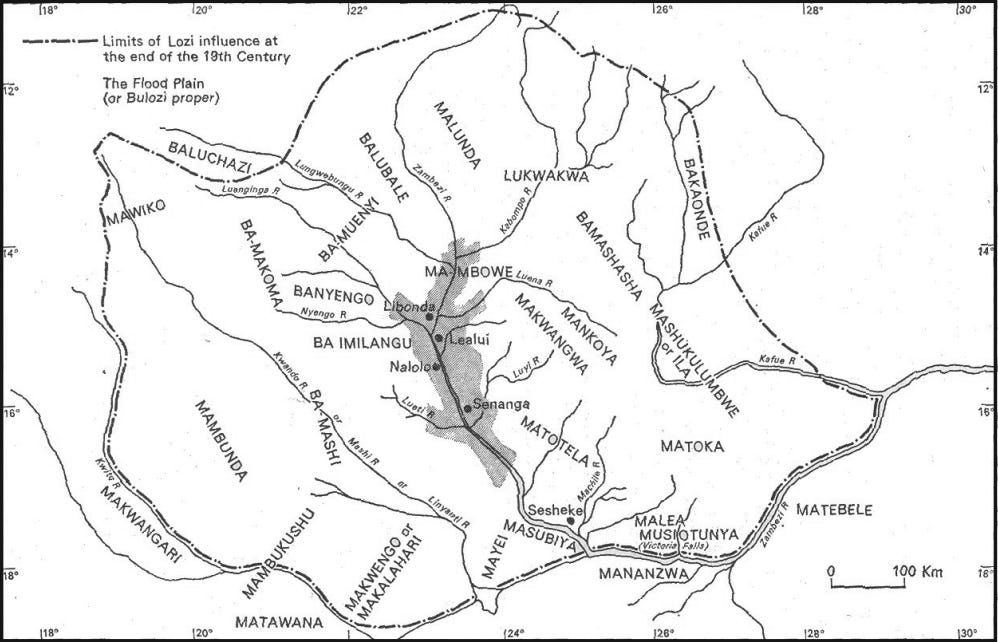

Map of Africa in 1880 highlighting the location of the Lozi kingdom (Barosteland) 2

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of the Lozi kingdom

The landscape of the Lozi heartland is dominated by the Zambezi River which cuts a bed of the rich alluvial Flood Plain between the Kalahari sands and the miombo woodlands in modern Zambia.

The region is dotted with several ancient Iron Age sites of agro-pastoralist communities dating from the 1st/5th century AD to the 12th/16th century, in which populations were segmented into several settlement sites organized within lineage groups. 3 It was these segmented communities that were joined by other lineage groups arriving in the upper Zambezi valley from the northern regions under the Lunda empire, and gradually initiated the process of state formation which preceded the establishment of the Lozi kingdom. 4

The earliest records and traditions about the kingdom's founding are indirectly associated with the expansion and later break-up of the Lunda empire, in which the first Lozi king named Rilundo married a Lunda woman named Chaboji. Rulindo was succeeded by Sanduro and Hipopo, who in turn were followed by King Cacoma Milonga, with each king having lived long enough for their former capitals to become important religious sites. 5

The above tradition about the earliest kings, which was recorded by a visitor between 1845-1853, refers to a period when the ruling dynasty and its subjects were known as the Aluyana and spoke a language known as siluyana. In the later half of the 19th century, the collective ethnonym for the kingdom's subjects came to be known as the lozi (rotse), an exonym that emerged when the ruling dynasty had been overthrown by the Makololo, a Sotho-speaking group from southern Africa. 6

King Cacoma Milonga also appears in a different account from 1797, which describes him as “a great souva called Cacoma Milonga situated on a great island and the people in another.” He is said to have briefly extended his authority northwards into Lunda’s vassals before he was forced to withdraw. 7 He was later succeeded by King Mulambwa (d. 1830) who consolidated most of his predecessors' territorial gains and reformed the kingdom's institutions inorder to centralize power under the kingship at the expense of the bureaucracy. 8

Mulambwa is considered by Lozi to have been their greatest king, and it was during his very long reign that the kingdom’s political, economic, and judicial systems reached that degree of sophistication noted by later visitors. 9

the core territories of the Lozi kingdom 10

The Government in 19th century buLozi

At the heart of the Lozi State is the institution of kingship, with the Lozi king as the head of the social, economic and administrative structures of the whole State. After the king's death, they're interred in a site of their choosing that is guarded by an official known as Nomboti who serves as an intermediary between the deceased king and his successors and is thus the head of the king's ancestral cult. 11

The Lozi bureaucracy at the capital, which comprised the most senior councilors ( Indunas ) formed the principal consultative, administrative, legislative, and judicial bodies of the nation. A single central body the councilors formed the National Council ( Mulongwanji) which was headed by a senior councilor ( Ngambela) as well as a principal judge ( Natamoyo) . A later visitor in 1875 describes the Lozi administration as a hierarchy of “officers of state” and “a general Council” comprising “state officials, chiefs, and subordinate governors,” whose foundation he attributed to “a constitutional ruler now long deceased”. 12

The councilors were heads of units of kinship known as the Makolo , and headed a provincial council ( kuta ) which had authority over individual groups of village units ( silalo ) that were tied to specific tracts of territories/land. These communities also provided the bulk of the labour and army of the kingdom, and in the later years, the Makolo were gradually centralized under the king who appointed non-hereditary Makolo heads. This system of administration was extended to newly conquered regions, with the southern capital at Nalolo (often occupied by the King’s sister Mulena Mukwai ), while the center of power remained in the north with the roving capital at Lealui. 13

The valley's inhabitants established their settlements on artificially built mounds ( liuba ) tending farms irrigated by canals, activities that required large-scale organized labor. Some of the surplus produced was sent to the capital as tribute, but most of the agro-pastoral and fishing products were exchanged internally and regionally as part of the trade that included craft manufactures and exports like ivory, copper, cloth, and iron. Long-distance traders from the east African coast (Swahili and Arab), as well as the west-central African coast (Africans and Portuguese), regularly converged in Lozi’s towns. 14

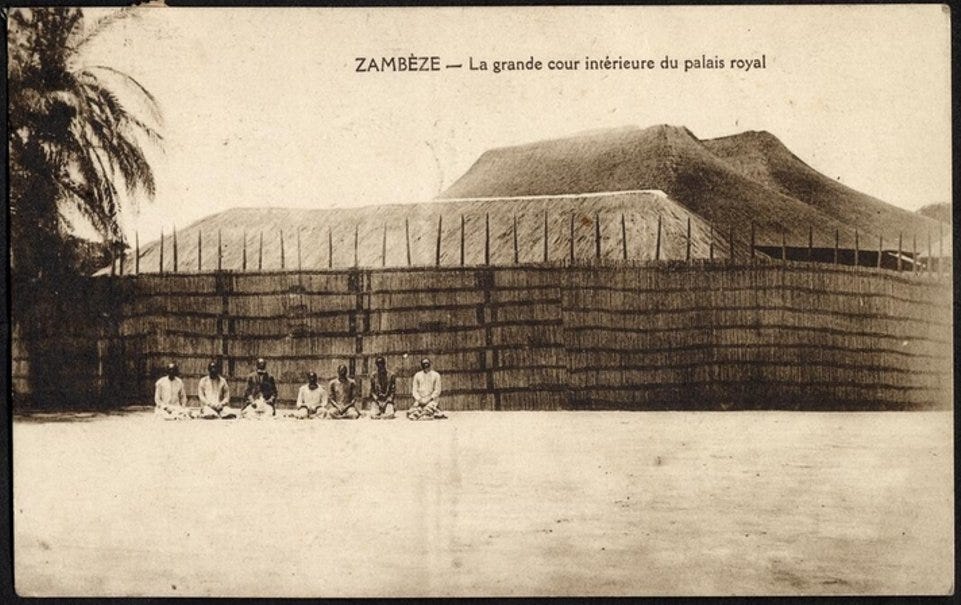

Palace of the King (at Lealui) ca. 1916, Zambia. USC Libraries.

Palace of the Mulena Mukwai/Mokwae (at Nalolo), 1914, Zambia. USC Libraries.

The Lozi kingdom under the Kololo dynasty.

After the death of Mulambwa, a succession dispute broke out between his sons; Silumelume in the main capital of Lealui and Mubukwanu at the southern capital of Nalolo, with the latter emerging as the victor. But by 1845, Mubukwanu's forces were defeated in two engagements by a Sotho-speaking force led by Sebetwane whose followers ( baKololo ) had migrated from southern Africa in the 1820s as part of the so-called mfecane . Mubukwanu's allies fled to exile and control of the kingdom would remain in the hands of the baKololo until 1864. 15

Sebetwane (r. 1845-1851) retained most of the pre-existing institutions and complacent royals like Mubukwanu's son Sipopa, but gave the most important offices to his kinsmen. The king resided in the Caprivi Strip (in modern Namibia) while the kingdom was ruled by his brother Mpololo in the north, and daughter Mamochisane at Nololo, along with other kinsmen who became important councilors. The internal agro-pastoral economy continued to flourish and Lozi’s external trade was expanded especially in Ivory around the time the kingdom was visited by David Livingstone in 1851-1855, during the reign of Sebetwane's successor, King Sekeletu (r. 1851-1864). 16

The youthful king Sekeletu was met with strong opposition from all sections of the kingdom, spending the greater part of his reign fighting a rival candidate named Mpembe who controlled most of the Lozi heartland. After Sekeletu's death in 1864, further succession crisis pitted various royals against each other, weakening the control of the throne by the baKololo. The latter were then defeated by their Luyana subjects who (re)installed Sipopa as the Lozi king. While the society was partially altered under baKololo rule, with the Luyana-speaking subjects adopting the Kololo language to create the modern Lozi language, most of the kingdom’s social institutions remained unchanged. 17

The (re) installation of King Sipopa (r. 1864-1876) involved many Lozi factions, the most powerful of which was led by a nobleman named Njekwa who became his senior councilor and was married to Sipopa's daughter and co-ruler Kaiko at Nalolo. But the two allies eventually fell out and shortly after the time of Njekwa's death in 1874, the new senior councilor Mamili led a rebellion against the king in 1876, replacing him with his son Mwanawina. The latter ruled briefly until 1878 when factional struggles with his councilors drove him off the throne and installed another royal named Lubosi Lewanika (r.1878-84, 1885-1916) while his sister and co-ruler Mukwae Matauka was set up at Nalolo. 18

The Royal Barge on the Zambezi river , ca. 1910, USC Library

King Lewanika’s Lozi state

During King Lubosi Lewanika's long reign, the Lozi state underwent significant changes both internally as the King's power became more centralized, and externally, with the appearance of missionaries, and later colonialists.

After King Lubosi was briefly deposed by his powerful councilor named Mataa in favor of King Tatila Akufuna (r. 1884-1885), the deposed king returned and defeated Mataa's forces, retook the throne with the name Lewanika, and appointed loyalists. To forestall external rebellions, he established regional alliances with King Khama of Ngwato (in modern Botswana), regularly sending and receiving embassies for a possible alliance against the Ndebele king Lobengula. He instituted several reforms in land tenure, created a police force, revived the ancestral royal religion, and created new offices in the national council and military. 19

King Lewanika expanded the Lozi kingdom to its greatest extent by 1890, exercising varying degrees of authority over a region covering over 250,000 sqkm 20 . This period of Lozi expansion coincided with the advance of the European missionary groups into the region, followed by concessioners (looking for minerals), and the colonialists. Of these groups, Lewanika chose the missionaries for economic and diplomatic benefits, to delay formal colonization of the kingdom, and to counterbalance the concessionaries, the latter of whom he granted limited rights in 1890 to prospect for minerals (mostly gold) in exchange for protection against foreign threats (notably the powerful Ndebele kingdom in the south and the Portuguese of Angola in the west). 21

The Lozi kingdom at its greatest extent in the late 19th century

Lewanika oversaw a gradual and controlled adoption of Christianity (and literacy) confined to loyal councilors and princes, whom he later used to replace rebellious elites. He utilized written correspondence extensively with the various missionary groups and neighboring colonial authorities, and the Queen in London, inorder to curb the power of the concessionaires (led by Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa company which had taken over the 1890 concession but only on paper), and retain control of the kingdom. He also kept updated on concessionary activities in southern Africa through diplomatic correspondence with King Khama. 22

The king’s Christian pretensions were enabled by internal factionalism that provided an opportunity to strengthen his authority. Besides the royal ancestral religion, lozi's political-religious sphere had been dominated by a system of divination brought by the aMbundu (from modern Angola) whose practitioners became important players in state politics in the 19th century, but after reducing the power of Lewanika's loyalists and the king himself, the later purged the diviners and curbed their authority. 23

This purge of the Mbundu diviners was in truth a largely political affair but the missionaries misread it as a sign that the King was becoming Christian and banning “witchcraft”, even though they were admittedly confused as to why the King did not convert to Christianity. Lewanika had other objectives and often chided the missionaries saying; "What are you good for then? What benefits do you bring us? What have I to do with a bible which gives me neither rifles nor powder, sugar, tea nor coffee, nor artisans to work for me." 24

The newly educated Lozi Christian elite was also used to replace the missionaries, and while this was a shrewd policy internally as they built African-run schools and trained Lozi artisans in various skills, it removed the Lozi’s only leverage against the concessionaires-turned-colonists. 25

The Lozi kingdom in the early 20th century: From autonomy to colonialism.

The King tried to maintain a delicate balance between his autonomy and the concessionaries’ interests, the latter of whom had no formal presence in the kingdom until a resident arrived in 1897, ostensibly to prevent the western parts of the kingdom (west of the Zambezi) from falling under Portuguese Angola. While the Kingdom was momentarily at its most powerful and in its most secure position, further revisions to the 1890 concessionary agreement between 1898 and 1911 steadily eroded Lewanika's internal authority. 26

Internal opposition by Lozi elites was quelled by knowledge of both the Anglo-Ndebele war of 1893 and the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902. But it was the Anglo-Boer war that influenced the Lozi’s policies of accommodation in relation to the British, with Lozi councilors expressing “shock at the thought of two groups of white Christians slaughtering each other”. 27 The war illustrated that the Colonialists were committed to destroying anyone that stood in their way, whether they were African or European, and a planned expulsion of the few European settlers in Lozi was put on hold.

Always hoping to undermine the local colonial governors by appealing directly to the Queen in London, King Lewanika prepared to travel directly to London at the event of King Edward’s coronation in 1902, hoping to obtain a favorable agreement like his ally, King Khama had obtained on his own London visit in 1895. When asked what he would discuss when he met King Edward in London, the Lozi king replied: “When kings are seated together, there is never a lack of things to discuss.” 28

King Lewanika (front seat on the left) and his entourage visiting Deeside, Wales, ca. 1901 , Aberdeen archives

It is likely that the protection of western Lozi territory from the Portuguese was also on the agenda, but the latter matter was considered so important that it was submitted by the Portuguese and British to the Italian king in 1905, who decided on a compromise of dividing the western region equally between Portuguese-Angola and the Lozi. While Lewanika had made more grandiose claims to territory in the east and north that had been accepted, this one wasn’t, and he protested against it to no avail 29

After growing internal opposition to the colonial hut tax and the King’s ineffectiveness had sparked a rebellion among the councilors in 1905, the colonial governor sent an armed patrol to crush the rebellion, This effectively meant that Lewanika remained the king only nominally, and was forced to surrender the traditional authority of Kingship for the remainder of his reign. By 1911, the kingdom was incorporated into the colony of northern Rhodesia, formally marking the end of the kingdom as a sovereign state. 30

the Lozi king lewanika ca. 1901. Aberdeen archives

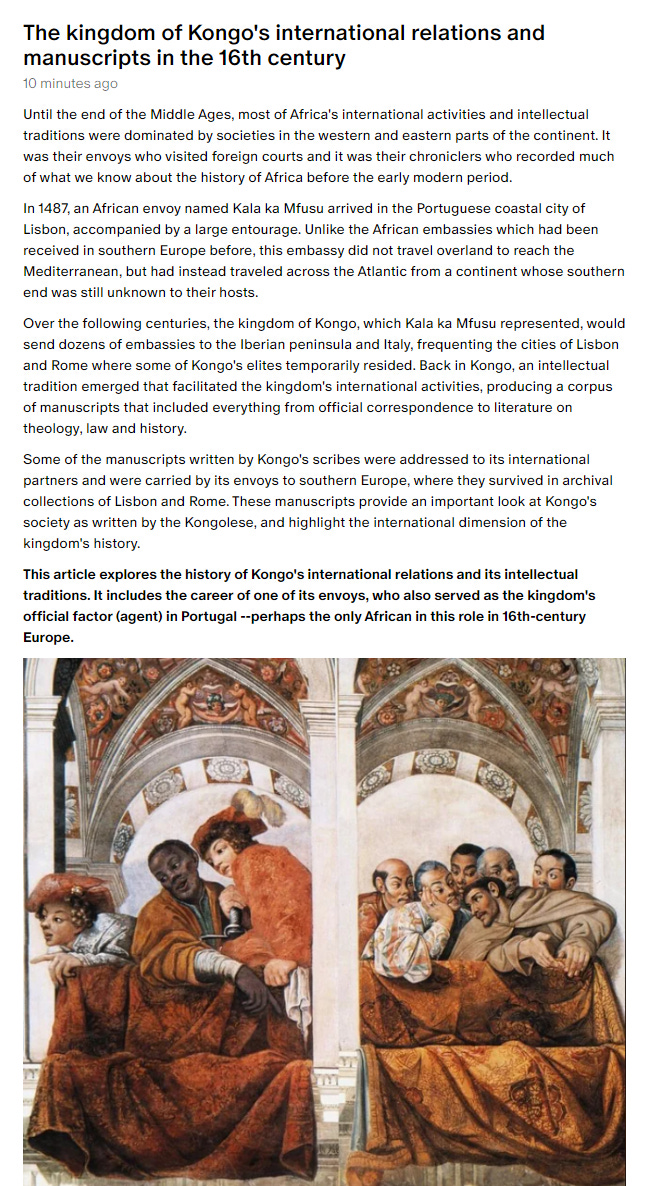

A few hundred miles west of the Lozi territory was the old kingdom of Kongo, which created an extensive international network sending its envoys across much of southern Europe and developed a local intellectual tradition that includes some of central Africa’s oldest manuscripts.

Read more about it here:

KONGO'S FOREIGN RELATIONS & MANUSCRIPTS

Thanks for reading African History Extra! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901-1914 By Jeffrey Green pg 22

Map by Sam Bishop at ‘theafricanroyalfamilies’

Iron Age Farmers in Southwestern Zambia: Some Aspects of Spatial Organization by Joseph O. Vogel

Iron Age History and Archaeology in Zambia by D. W. Phillipson

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton pg 310, Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 18-20)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 5, 10-15)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton pg 310)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 57-59)

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 2

Map by Mutumba Mainga

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 30)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 38-41, The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 3-5

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 33-36, 44-47, 50-54)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 32, 130-131)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 61-71)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 74-82, The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 9-11

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 87-92, The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 11-12

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 103-113, The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 13-15

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 19- 34 Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 115- 136)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia pg 150-161)

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 38-56, Barotseland's Scramble for Protection by Gerald L. Caplan pg 280-285

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 174-175)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 137-138)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 179-182)

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 76-81

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 63-68, 74-75

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 76

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 192)

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 88-89.

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 90-103

Ready for more?

- lightbulb_outline Advanced Search

Cite This Item

Copy and paste a formatted citation or use one of the links below to export the citation to your chosen bibliographic manager.

Copy Citation

Chicago manual of style 17th edition (author date), apa 7th edition, mla 9th edition, harvard reference format (author date), export citation, your privacy.

This website uses cookies to analyze traffic so we can improve your experience using eHRAF.

By clicking “Accept all cookies”, you agree eHRAF can store cookies on your device and disclose information in accordance with our Cookie Policy .

Secessionism in African Politics pp 293–328 Cite as

United in Separation? Lozi Secessionism in Zambia and Namibia

- Wolfgang Zeller 7 &

- Henning Melber 8 , 9 , 10 , 11

- First Online: 21 August 2018

967 Accesses

2 Citations

Part of the book series: Palgrave Series in African Borderlands Studies ((PSABS))

This chapter analyzes why secessionist movements on both sides of the Namibia-Zambia border have—despite shared roots—so far never joined forces in a united cause of pan-Lozi nationalism. We outline the historical processes through which the Lozi kingdom was partitioned and gradually transformed into Barotseland and the Caprivi Strip during the colonial period. We then examine how decolonization planted the seeds of Lozi separatism in Western Province and the secessionist movement in Caprivi, and how these evolved separately after Zambia’s and Namibia’s independence. The final section traces the initial thawing and renewed freezing of relations between successive central governments and separatists in the Zambian case, as well as the high treason trial that defined the aftermath of the Caprivi secession in Namibia.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

The terms Lozi and Barotse are synonymous.

In the Lozi administrative hierarchy the Ngambela is the most senior councilor who communicates decisions between the Litunga and the khuta , as well as the public. In obvious relation to the Westminster Model, he is often referred to as “Prime Minister.”

United Democratic Party ( 2005 ).

The exact number is disputed but this is the verifiable minimum number of casualties.

WP: 2010 Zambia national census; Caprivi: 2011 Population and Housing Census.

Cf. Lemarchand ( 1972 ) and Eifert et al. ( 2010 ).

cf. Zeller ( 2007a , b , 2009 , 2010 ) and Melber ( 2009 ).

Hobsbawm and Ranger ( 1983 ), Mamdani ( 1996 ) and Forrest ( 2004 )

Mainga ( 1973 ), Caplan ( 1970 ), Gluckman ( 1959 ), Trollope ( 1937 : 19) and Flint ( 2003 )

Gluckman ( 1955 , 1965 ). See also Sumbwa ( 2000 ).

Caplan ( 1970 ) and Mainga ( 1973 : 139).

Flint ( 2003 : 402–410), Mainga ( 1973 : 132f) and Gluckman ( 1941 : 96).

Caplan ( 1969 )

Mainga Bull ( 1995 : 5).

Flint ( 2004 : 119)

Mainga ( 1973 : 171)

Anglo-German agreement of 1890, Article III. 2.

The English name of the document is “Anglo-German Agreement of 1890.”

The population of the area referred to the place as “Luhonono” and in August 2013, the Namibian government announced that this would replace “Schuckmannsburg” as its official name.

Streitwolf ( 1911 : 229–234).

Mainga Bull ( 1995 : 5), Mainga ( 1973 : 161) and Caplan ( 1970 : 74–118).

Caplan ( 1970 : 86f).

Van Horn ( 1977 : 164) and Gluckman ( 1941 : 164).

Mainga ( 1973 : 206)

Mainga Bull ( 1995 : 6)

Streitwolf ( 1911 : 110).

Two of these groups claimed autonomous chieftaincies in the post-independence period and their official recognition by the South West African People Organisation (SWAPO) government infuriated the core leadership of the Mafwe.

Mainga Bull ( 1995 : 6).

Caplan ( 1970 : 145)

Kangumu ( 2000 , 2011 )

Caplan ( 1970 : 168ff)

Mainga Bull ( 1995 : 9) and Caplan ( 1968 : 346f)

Caplan ( 1968 : 350f) and Mulford ( 1967 : 212ff)

Sumbwa ( 2000 )

Caplan ( 1968 : 355)

Mainga Bull ( 1995 : 12)

Kenneth Kaunda in a speech at Lealui on August 6, 1964, cited in Sumbwa ( 2000 , 114).

Caplan ( 1968 : 356)

Silozi is used for regular administrative proceedings, Siluyana for royal and ceremonial affairs.

MP Mrs. Judith Hart http://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=1966-12-13a.227.9&s=barotse#g229.4 .

Flint ( 2004 : 167f).

Cf. Hobsbawm and Ranger ( 1983 ).

In 1963 the South African government published the Report of the Commission of Enquiry into South West African Affairs, commonly known as the Odendaal Report after its chairman, Fox Odendaal. Its official purpose was to make recommendations on the best ways to promote the socioeconomic development of Namibia’s black majority population, but it is widely regarded as an attempt to fend off anti-Apartheid critics.

Flint ( 2004 : 174) and Kangumu ( 2011 : 214 ff)

Fisch ( 1999 : 42)

Muyongo served as SWAPO Representative in Zambia (1964–1965), Educational Secretary (1966–1970), and Vice President (1970–80)

United Democratic Party ( 2005 ) and Flint ( 2004 : 188).

http://www.caprivivision.com/who-has-the-power-to-revive-canu/ .

Caprivi Freedom ( 2013 )

South Africa ( 1964 ).

Fosse ( 1996 ) and Kangumu ( 2011 )

Cf. Melber and Saunders ( 2007 )

Virtual Zambia ( 2008 )

MMD ( 1991 )

Times of Zambia (January 31, 2009).

Englebert ( 2005 : 29–59) and Sumbwa ( 2000 : 115f)

Mainga Bull ( 1995 : 8) and Sumbwa ( 2000 : 116)

Sumbwa ( 2000 : 117)

Sumbwa ( 2000 : 119f)

Minorities at Risk ( 2009 ).

Barotse National Conference ( 1995 ).

The Post (1994) and Englebert ( 2005 )

Englebert ( 2005 ). Compare with Mbikusita-Lewanika ( 2001 ) and Barotse Patriotic Front ( 2004 )

Muyongo was the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA) Vice President from 1987 until 1992 and DTA President from 1992 to 1999. http://www.klausdierks.com/Biographies/Biographies_M.htm l. Accessed June 30, 2008

As Soiri (2001: 200) notes, it is difficult to establish whether politics entered into ethnicity or vice versa.

Fosse ( 1996 : 165–168) and Flint ( 2004 : 244–266)

Fosse ( 1996 : 165)

Fisch ( 1999 : 20)

Compare with Streitwolf ( 1911 : 126)

Soiri ( 2001 : 201).

See also Flint ( 2003 : 427).

Amnesty International ( 2003a )

cf. Zeller ( 2007b , 2010 )

Amnesty International ( 2003b )

afrolNews/IRIN ( 2006 )

The Namibian , February 12, 2013 and Menges ( 2013 ).

Analysis Africa ( 2013 ). The overall figures slightly differ according to sources and cannot be verified beyond any doubt. As the report also concludes: “Many have been tortured, and the state now faces potentially huge civil claims from the 43 men set free by the court after spending 13 years in jail.” See also The Namibian of February 2, 2002, and of June 16, 2007, reporting on the claims of some of the accused to be “Caprivians” and not “Namibians » and hence refusing to accept the jurisdiction of the Namibian courts.

Examples include a pro-secessionist opinion piece published in Caprivi Vision 1 September 2005, and the controversy over the revival and subsequent banning of the United Democratic Party (UDP) ( The Namibian , July 28, 2006, and September 8, 2006; Allgemeine Zeitung , September 4, 2006; New Era , September 4–5, 2006). Caprivi separatists claim that this (hitherto undisclosed) document proves that the 1964 Caprivi African National Union (CANU)-SWAPO merger was agreed on the condition that Caprivi would become an independent state separate from Namibia ( The Namibian , January 24, 2007), the reinstallment of CANU by locals and the repeated public claims by accused and acquitted high treason suspects that Caprivi is historically “not part of Namibia” ( The Namibian , February 2, 2005; January 17, 2007, April 17, 2007, and June 14, 2007, respectively).

Sankwasa ( 2013 )

Sasman ( 2017 )

Namibian Sun ( 2013 ).

http://www.caprivifreedom.com/news.i?cmd=view&nid=1198 .

http://www.caprivifreedom.com/news.i?cmd=view&nid=1185 ; see also www.capriviconcernedgroup.com .

http://geocurrents.info/news-map/war-and-strife-news/continuing-tension-in-namibias-caprivi-strip#ixzz2VXa0UJv5 ; http://www.thevillager.com.na/news_article.php?id=1439&title=Caprivi%20rises%20%20again .

The ruling party’s handling of the SWAPO detainee issue and the National Society for Human Rights and, the emergence of opposition parties Congress of Democrats and Rally for Democracy and Progress are prominent examples.

Reader’s Letter (2008). The Namibian , accessed at: http://www.namibian.com.na/2008/March/letters/08ED201395.html .

The Namibian ( 2008 ). See also “Pohamba at political rally.” 2008. The Namibian , accessed at: http://www.namibian.com.na/2008/February/national/08EB20FA4F.html .

Mutenda ( 2013 ).

Guijarro ( 2013 ).

Sanzila ( 2013 )

Ngoshi ( 2013 ).

Kaure ( 2013 ).

The Windhoek Observer ( 2013 ).

Interview, Inyambo Yeta (2005).

http://www.postzambia.com/post-read_article.php?articleId=25516 .

http://www.postzambia.com/post-read_article.php?articleId=21897 .

http://www.postzambia.com/post-read_article.php?articleId=18135 .

http://www.ukzambians.co.uk/home/2012/02/28/president-satas-reaction-to-barotse-report-a-u-turn-or-a-consciously-calculated-electoral-deception/?695d7100 .

http://www.barotseland.info/Freedom_Resolution_2012.htm .

Afrol News/IRIN. (2006). Caprivi political party declared illegal . Retrieved from http://www.afrol.com/articles/21239

Amnesty International. (2003a). Namibia. Justice delayed is justice denied. The Caprivi treason trial. Amnesty International, report reference AFR 42/001/2003.

Google Scholar

Amnesty International. (2003b). Namibia: Authorities must ensure a fair trial for Caprivi defendants . Amnesty International, report reference AFR 42/005/2003.

Analysis Africa. (2013). Caprivi secession trial still haunts Namibia . Retrieved from http://analysisafrica.com/reports/caprivi-secession-trial-still-haunts-namibia/#.Ucr2CqxjEuJ

Barotse National Conference. (1995). Resolutions of the Barotse National Conference Lealui . Lusaka, Zambia, November 3–4, 1995.

Barotse Patriotic Front. (2004). Submission to the Constitutional Review Commission.

Caplan, G. L. (1968). Barotseland, the secessionist challenge to Zambia. Journal of Modern African Studies, 6 (3), 343–360.

Article Google Scholar

Caplan, G. L. (1969). Barotseland’s scramble for protection. Journal of African History, x (2), 277–294.

Caplan, G. L. (1970). The elites of Barotseland 1878–1969: A political history of Zambia’s Western Province . London: C. Hurst & Co.

Book Google Scholar

Caprivi Freedom. (2013). History. Retrieved from http://www.caprivifreedom.com/history.i

Eifert, B., Miguel, E., & Posner, D. N. (2010). Political competition and ethnic identification in Africa. American Journal of Political Science, 54 (2), 494–510.

Englebert, P. (2005). Compliance and defiance to national integration in Barotseland and Casamance. Afrika Spektrum, 39 (1), 29–59.

Fisch, M. (1999). The secessionist movement in the Caprivi: A historical perspective . Windhoek: Namibia Scientific Society.

Flint, L. (2003). State-building in Central Southern Africa: Citizenship and subjectivity in Barotseland and Caprivi. Journal of African Historical Studies, 36 (2), 393–428.

Flint, L. (2004). Historical constructions of postcolonial citizenship and subjectivity: The case of the Lozi peoples of southern Central Africa . Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Birmingham.

Forrest, J. B. (2004). Subnationalism in Africa: Ethnicity, alliances, and politics . Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Fosse, L. J. (1996). Negotiating the nation in local terms . Ethnicity and nationalism in eastern Caprivi, Namibia . Master’s thesis, Department and Museum of Anthropology, University of Oslo.

Gluckman, M. (1941). Economy of the central Barotse plain . Livingstone: Rhodes-Livingstone Institute.

Gluckman, M. (1955). The judicial process among the Barotse of northern Rhodesia . Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Gluckman, M. (1959). The Lozi of Barotseland in Northwestern Rhodesia. In E. Colson & M. Gluckman (Eds.), Seven tribes of British Central Africa (pp. 1–93). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Gluckman, M. (1965). The ideas in Barotse jurisprudence . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Guijarro, E. M. (2013). An independent Caprivi: A madness of the few, a partial collective yearning or a realistic possibility? Citizen perspectives on Caprivian secession. Journal of Southern African Studies, 39 (2), 337–352.

Hobsbawm, E., & Ranger, T. (Eds.). (1983). The invention of tradition . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kangumu, B. (2000). A forgotten corner of Namibia: Aspects of the history of the Caprivi strip, c. 1939-1980 . Master’s thesis, University of Cape Town.

Kangumu, B. (2011). Contesting Caprivi a history of colonial isolation and regional nationalism in Namibia . Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Kaure, A. T. (2013, August 23). There was once a region. The Namibian .

Lemarchand, R. (1972). Political clientelism and ethnicity in tropical Africa: Competing solidarities in nation-building. The American Political Sciences Review, 66 (1), 68–90.

Mainga Bull, M. (1973). Bulozi under the Luyana kings . Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Mainga Bull, M. (1995). The 1964 Barotseland Agreement in Historical Perspective . Livingstone: Institute of Economic Studies.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mbikusita-Lewanika, A. (2001). Barotseland: Bastion of resistance . Paper presented at conference Interrogating the New Political Culture in Southern Africa, Harare, 13–15 June, 2001.

Melber, H. (2009). One Namibia, one nation? The Caprivi as a contested territory. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 27 (4), 463–481.

Melber, H., & Saunders, C. (2007). Conflict mediation in decolonisation: Namibia’s transition to independence. Africa Spectrum, 42 (1), 73–94.

Menges, W. (2013, December 19). Treason accused sue for N$ 1,2 billion. The Namibian .

Minorities at Risk. (2009). Assessment for Lozi in Zambia. Retrieved from http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/mar/assessment.asp?groupId=55102

Movement for Multi-Party Democracy. (1991). The MMD manifesto . MMD: Lusaka.

Mulford, D. C. (1967). Zambia. The politics of independence 1957–1964 . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mutenda, M. (2013, August 15). Namibia: Zambezi name fuels heated debate. New Era .

Namibian Sun. (2013, November 25). Blow for Caprivian exiles’ home return. Namibian Sun.

Ngoshi, M. K. (2013, August 23). Caprivians in the Zambezi region. The Namibian .

Sankwasa, F. (2013, November 19). Govt wants to entice refugees back. Namibian Sun .

Sanzila, G. (2013, August 21). Zambezi name still causing waves. New Era .

Sasman, C. (2017, April 21). Muyongo speaks out. Namibian Sun.

Soiri, I. (2001). SWAPO wins, apathy rules: The Namibian 1998 local authority elections. In M. Cowen & L. Laakso (Eds.), Multi-party elections in Africa (pp. 187–216). London: James Currey.

South Africa. (1964). Report of the commission into SWA affairs, 1962–3, Pretoria.

Streitwolf, K. (1911). Der Caprivizipfel . Berlin: Süsserott.

Sumbwa, N. (2000). Traditionalism, democracy and political participation: The case of Western Province, Zambia. African Study Monographs, 21 (3), 105–146.

The Namibian. (2008, April 1). Pohamba at power line opening. The Namibian.

The Windhoek Observer. (2013, August 22). What’s in a name? The Windhoek Observer.

Trollope, W. E. (1937). Inspection tour 1937. National Archives of Namibia, 2267 , A503/1-7.

United Democratic Party. (2005). Caprivi Zipfel: The controversial strip. Retrieved from http://www.caprivifreedom.com/history.i?cmd=view&hid=23

Van Horn, L. (1977). The agricultural history of Barotseland, 1840–1964. In R. Palmer & N. Parsons (Eds.), The roots of rural society in Central and Southern Africa (pp. 144–169). London: Heinemann.

Virtual Zambia. (2008). The economic history of Zambia . Retrieved from http://www.bized.co.uk/virtual/dc/back/econ.htm

Zeller, W. (2007a). Chiefs, policing and vigilantes: ‘Cleaning up’ the Caprivi borderland of Namibia. In L. Buur & H. M. Kyed (Eds.), State recognition and democratization in sub-Saharan Africa: A new dawn for traditional authorities? (pp. 79–104). New York: Palgrave.

Chapter Google Scholar

Zeller, W. (2007b). ‘Now we are a town’: Chiefs, investors, and the state in Zambia’s Western Province. In L. Buur & H. M. Kyed (Eds.), State recognition and democratization in sub-Saharan Africa: A new dawn for traditional authorities? (pp. 209–231). New York: Palgrave.

Zeller, W. (2009). Danger and opportunity in Katima Mulilo: A Namibian border boomtown at transnational crossroads. Journal of Southern African Studies, 35 (1), 133–154.

Zeller, W. (2010). Neither arbitrary nor artificial: Lozi chiefs and the making of the Namibia-Zambia borderland. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 25 (2), 6–21.

Dr. Stephen Muliokela, Director Golden Valley Agricultural Research Trust, Lusaka, June 4, 2004.

Mr. Marcus Ndebele, market trader, Mwandi, May 25, 2004.

Mr. Namukolo Mukutu, former Permanent Secretary for Agriculture, Lusaka, 4 June 2004.

Mr. Sibeso Yeta, Mwandi, May 20, 2004.

Mr. Wally Herbst, Mwandi, May 24, 2004.

Mrs Fiona Dixon-Thompson, Mwandi, May 24, 2004.

Munukayumbwa Mulumemui, BRE Induna Omei for Sesheke District, Mwandi, May 21, 2004.

Dominik Sandema, BRE Induna Anasambala for Sesheke District, Mwandi, June 11, 2004.

Senior Chief Inyambo Yeta, BRE chief for Sesheke District, Mwandi, June 14, 2004.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Wolfgang Zeller

Nordic Africa Institute, Uppsala, Sweden

Henning Melber

Department of Political Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Centre for Africa Studies, University of the Free State in Bloemfontein, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Centre for Commonwealth Studies/School for Advanced Study, University of London, London, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wolfgang Zeller .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Wageningen University & Research, De Bilt, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Lotje de Vries

Pomona College, Claremont, CA, USA

Pierre Englebert

Overseas Development Institute, London, UK

Mareike Schomerus

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Zeller, W., Melber, H. (2019). United in Separation? Lozi Secessionism in Zambia and Namibia. In: de Vries, L., Englebert, P., Schomerus, M. (eds) Secessionism in African Politics. Palgrave Series in African Borderlands Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90206-7_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90206-7_11

Published : 21 August 2018

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-90205-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-90206-7

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Lozi Kingdom and the Kololo

The origins of the Luyi or Aluyana, as the Lozi people were originally called, are carefully concealed in myths designed to maintain the prestige and selectiveness of the ruling dynasty. “Luyi” or “Aluyana” means “people of the river.” According to myth, the Lozi came from Nyambe (the Lozi name for God). This myth of origin implies that they were indigenous, not immigrants, to the western province of Zambia. The Lozi myth is believed to have expressed an important truth because in the Lozi society, where the dynasty originated from mattered less than the nature of the land they colonized. However, historical evidence suggests that the Lozi came from the Lunda Empire. Consequently, the Lozi kingdom developed an imperial structure similar to other kingdoms that had a similar background. The kingdom was favored by a relatively prosperous valley environment that facilitated dense settlement of the people.

Once the kingdom had been founded, it had a special economic base that consisted of fertile plains of about hundred miles long which were flooded by the

Zambezi River every year. The kingdom, also generally known as Barotseland, accommodated peoples of clear distinct origin and history as opposed to the true Lozi who occupied the flood plain. These peoples lived in the surrounding woodland.

The Lozi kingdom was founded in seventh century by people believed to have come from the Lunda Empire to the north. It is also believed that the newcomers introduced intensive cultivation of the flood plain. By 1800 various peoples to the west were brought under Lozi rule while to those to the east and west paid tribute in form of labor. The flood plain was mainly administered by relatives of the king in the early days of the dynasty. Later some kind of royal bureaucracy— an unusual development anywhere in Africa— replaced the earlier system. This was possible because of the plain, which made demand for control a matter of political control as well. As guardian of the land, the king built up a following of loyal officials who he allocated states on the plain. The system enabled Lozi kings to make political appointments on the basis of personal merit instead of birth. As such any such appointees could lose both office and land allotted to them if they fell out of favor. Trade also developed between the various peoples in the region.

Trade in fish, grain, and basket work for the iron work, woodwork, and barkcloth made Barotseland fairly self-sufficient. The Lozi also raided the Tonga and the Ila for cattle and slaves. However, the Lozi did not participate in the slave trade because they needed to retain slaves themselves to perform manual labor in the kingdom. The control of trade made the Litunga more powerful in his kingdom. Through his Tndunas, the Litunga was able to have almost total control of the economy of the Lozi kingdom.

Following the Mfecane (a series of migrants set in motion by Shaka Zulu’s empire in South Africa), the Kololo were forced to move north to the Zambezi River. In 1845 the Kololo leader Sebitwane found the Lozi kingdom split by succession dispute following the death of the tenth Litunga Mulambwa in 1830. The succession dispute resulted into a civil that split the Lozi kingdom into three groups. Sebitwanes warriors quickly overrun the Lozi kingdom. The Kololo imposed their language on the Lozi, although their conquest was hardly disruptive. As a small group of nomad warriors who had turned into herders and not cultivators, they found the Lozi to have been well established. Their language became a unifying influence in the kingdom. Soon Kololo kingship became far more popular in style than that offered by the Lozi. Unlike his predecessor, the Kololo king was more of a war-captain and was freely accessible to his fellow warriors. This was unlike the Lozi Litunga who was surrounded by rituals and taboos, and hence kept secluded. Because of this, Kololo kings were liked and easily accepted by most Lozi subjects. Sebitwane won the loyalty of his subject people by giving them cattle, taking wives from various groups and even giving leaders conquered people important positions of responsibility. He treated both the Kololo and Lozi generously.

However, despite this apparent popularity, the Kololo kings failed to come to terms with the special circumstances of Barotseland. They therefore made their capitals to the south of the central plain, among marshes that they considered secure from their traditional adversaries, the Ndebele, to their south.

The kololo did not disrupt the economic system of the Lozi, which was based on mounds and canals of the flood plain. However, the political system of the Kololo was very different from that of the Lozi. In the Kololo political system, men who were of the same age as the king were made territorial governors. Initially, this ensured that the flow of tribute to the king’s court. The system did not, however, guarantee the continued operating system of the flood plain.

The Lozi kingdom was prone to malaria and had eventually developed an immunity to the disease. The Kololo, however, were not immune, and were often afflicted with the disease. This greatly undermined the Kololo ability to resist the Lozi when the latter rose against their conquerors. The various Lozi princes who had escaped and fled from Kololo invasion had taken refuge to the north. Among them was Sepopa.

Following the death of Sebitwane in 1851, he was succeeded by weak rulers. His son Sekeletu was not as able a ruler as his father. He died in 1863 after which Kololo rule declined completely. The Lozi and the Toka-Leya, who had also been under Kololo rule, rose against the Kololo and declared themselves independent. The Kololo did not put up any serious resistance because they were terribly divided.

In 1864 Sepopa raised a Lozi army that took advantage of malaria-afflicted Kololo and successfully defeated it. Sepopa revived the Lozi institutions, but the problem of royal succession resurfaced, and it remained a source of weakness for the revived Lozi kingdom. Consequently, Sepopa was overthrown in 1878. For two years instability reigned until 1878 when Lewanika became king of the Lozi as Litunga. He too continued to have difficulties retaining his position as king. He was constantly under threat of attack from the Ndebele in the south. This relationship with the Ndebele forced Lewanika to take a friendly attitude toward European visitors to his kingdom.

Bizeck J. Phiri

See also: Difaqane on the Highveld; Lewanika I, the Lozi and the BSA Company; Tonga, Ila, and Cattle.

Further Reading

Flint, E. “Trade and Politics in Barotseland During the Kololo Period.” Journal of African History. 2, no. 1 (1970): 72-86.

Langworthy, H. W. Zambia Before 1890: Aspects of Precolonial History. London: Longman, 1972.

Mainga, M. “The Lozi Kingdom.” In A Short History of Zambia, edited by B. M. Fagan. 2nd ed. Nairobi: Longman, 1968.

Muuka, L. S. “The colonisation of Barotseland in the 17th century.” In The Zambesian Past, edited by E. Stokes and R. Brown. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1966.

Roberts, A. A History of Zambia. London: Heinemann, 1976.

Smith, E. W. “Sebetwane and the Makololo.” African Studies. 15, no. 2 (1956): 49-74.

- WorldHistory -> Sundries

An Introduction to Zambia's Lozi People

This tribe believe they are descended from the sun - here's everything you need to know about zambia's lozi people..

The Lozi tribe of Western Zambia are a proud people with a complex history. They are the only tribe in Zambia with a King instead of a chief, and account for approximately 900,000 people. This is an introduction to Zambia’s Lozi people.

According to myth, the Lozi tribe began when the sun god Nyambe descended from heaven onto Barotseland, which is the Lozi homeland. He came with his wife Nasilele (the moon), and together they began the line of Luyi-Luyana kings. Before ascending back to the heavens, they left their daughter Mbuyu to continue the line of leadership through her male offspring.

Another account of the creation of the Lozi tribe is that they came from the Lunda Kingdom in present day Democratic Republic of Congo, and were led into Western Zambia by a Lunda princess called Mbuywamwamba between the 17th and 18th centuries. This was during the Bantu Migration from which other Zambian tribes such as the Bemba also moved into Zambia.

The historical account is that the Lozi were originally called the ‘ Luyi ‘ (meaning ‘Foreigner’) and spoke a language called Siluyana. They lived in Bulozi, a plain in the Upper Zambezi. In 1830, the Luyi people were conquered by the Makololo tribe under a leader called Sebetwane, who was part of many tribes that escaped the Mfecane , a series of wars under the Zulu king Shaka from present day South Africa. The Makololo changed the Luyi’s name to ‘Lozi’, which translates to ‘plain’. Although the Makololo were overthrown in 1864, the Luyi kept their new name.

It was believed that Barosteland had copper, gold and other minerals, so Cecil Rhodes, a colonialist figure known for his dreams of building a road from Cape Town , South Africa to Cairo, Egypt convinced the Litunga (the King – known by the name Lewanika) to sign over mining rights to Rhodes British South African Company under the Lochner Concession of 1890. Barosteland then became a British protectorate with the Lozis offered protection from neighboring tribes interested in conquering the Lozi. Barotseland became part of Northern Rhodesia (now known as Zambia) in May 1964, five months before Northern Rhodesia became an independent nation.

The Lozi are mostly concentrated in the Western Province of Zambia, although they are also based in smaller numbers in the Caprivi strip of Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique and Zimbabwe . The Lozi homeland is called Barotseland, and was once considered to be an independent kingdom with its own flag. The administrative capital is called Lealui, and the winter capital is called Limulunga – the towns are separated by a distance of approximately 11 miles (17.7 km). The town of Mongu is the political capital and is approximately 10 miles (16km) west of Lealui.

The Lozis show respect through a practice called likute . According to the essay ‘Moonlight and Clapping Hands: Lozi Cosmic Arts of Barosteland’ by Karen E Milbourne from the book African Cosmos published by Stellar Arts, it is “the performance of politeness, deference and cooperation… Its most visible feature consists of Lozi men and women clapping their hands in respect to one another, their leaders and the divine”. When members of the Lozi tribe meet the Litunga , they put their arms in the air, recite tributes and kneel several times as a form of respect.

Political structure

The Litunga is known as the ‘holder of the earth’ which is a literal translation of his name. This means all land in Barotseland belongs to the King, and his subjects are granted permission to live on the land. The Litunga is ruler of all Lozis. Under him is his prime minister, the Ngambela. The indunas or councilors are under the prime minister.

Traditional ceremony

The Lozis celebrate the Kuomboka ceremony annually in March or April at the end of the rainy season. It is one of the most popular traditional ceremonies in Zambia. ‘ Kuomboka ‘ translates to ‘get out of the water’ and involves the Litunga , his Queen and a number of their subjects moving from his residence at Lealui which floods annually, to Limulunga. The journey is a spectacle to watch, with the royal barge called the Nalikwanda (meaning ‘for the people’ which referred to the fact that the boat could be used by anyone, although later it came to be only used for the King) drawing attention with the large model elephant on the top. The Queen travels in a separate barge. The night before Kuomboka, the King beats a royal drum called the maoma which is a call to able-bodied men from the kingdom to prepare to escort their king. “Up to 120 men in leopard skins, red berets and lions manes to lead a flotilla of barges, banana boats and dugout canoes across lilly-studded waters” (Milborune, African Cosmos ).

Other drums that are played during the Kuomboka include the manjabila, lishoma, mwenduko, mutanga. “Manjabila is played in the Nalikwanda to give praises to the former leader of the canoe makers, and it alternates with maoma. Andlishoma is played up to the second landing at the harbour of Limulunga. Mwenduko together with mwatota and ngw’awawa (xylophones) are played while Nalikwanda is leaving. Mutango is played early in the morning to confirm to the people that the Litunga or Litunga la Mboela (The Queen) will not spend the night in Lealui or Nalolo. Firstly it will be played in the courtyard and thereafter at Namoo” (Barotse Royal Establishment, Kuomboka Ceremony, 2008: 14-15).

The Litunga’s traditional attire is called sikutindo, which is worn when boarding the royal barge. He also carries a namaya which is a fly whisk. He then changes into his other royal attire, a black and gold British admiral’s uniform which is said to have been given to the Litunga who was ruling in 1902 by King Edward VIII in recognition of a treaty that had been signed between the Lozis and Queen Victoria.

Male members of Barosteland (the Lozi kingdom) wear a siziba – a skirt which is red, black and white chitenge (a cotton print fabric usually with bold patterns). They wear a matching waistcoat and red beret called a lishushu . The women wear a satin outfit called musinsi which consists of two skirts , a top called a baki and a small wrapper called a chali.

Women and men from the Lozi tribe sometimes wear ivory bangles which are given at different points in life such as birth, puberty etc.

Another way to learn about Lozi culture is to visit the Nayuma Museum which is located opposite the Litunga’s palace in Mongu.

Identity and naming

The Lozi sometimes name their children after former royal leaders. For instance, the name Matauka is usually given to a female child and was the name of the Queen whose brother was the Litunga from 1875 – 1885 and 1886 – 1916. Nasilele is also a common female name and refers to the wife of Nyambe (the sun god) who according to myth founded the Lozi tribe.

Traditionally, the eyes and mouth were kept open at the point of death. Men were buried facing east, while women were buried facing west. The dead were buried with their personal possessions as it was believed that they would be needed in the afterlife. According to the kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane blog , “The grave of a person of status, which is situated to the side of the commoner s cemetery, is surrounded by a circular barrier of grass and branches. As sign of grief, the kin of the deceased wear their skin cloaks inside out. The hut of the deceased is pulled down, the roof being placed near the grave, while the remaining possessions of the dead person are burned so that nothing will attract the ghost back to the village”. The funeral for a deceased King is a more elaborate affair.

The Lozi perform a variety of dances based on occasion. During a girl’s initiation, a dance called siyomboka is performed. It is also the name of the conical drum that is used during the occasion. During royal occasions such as Kuomboka , men and women perform different dances. The ngomalume is a warrior-style dance performed only by men. It “demands skillful co-ordination of steps and the abdominal movements” (Agrippa Njungu, Music of My People (II): Dances in Barotseland ). The liwale is performed by women at royal events. Other dances include the liimba, lishemba and sipelu, which is the most popular.

Like the myth of the creation of the Lozi tribe, there are many others. One of the most fascinating is the myth of the Lengolengole , a creature with the head of a snake and lizard-like feet that lives in the Zambezi river and was said to have been spotted by a Litunga in the early 20th century.

Food and drink

According to a Food and Consumption Report titled ‘ The Common Zambian Foodstuff, Ethnicity, Preparation and Nutrient Composition of selected foods’ by Drinah Banda Nyirenda, Ph.D., Martha Musukwa, MSc. and Raider Habulembe Mugode, BSc, the Lozi ethnic grouping occupy and control access to the floodplain with its potential for cattle production, fishing, wetland/floodplain agriculture (rice and maize), and harvesting of foodstuffs from the natural fauna and flora of the floodplain. The preferred fruits of the Lozi are exotic fruits. Apart from local fruits such as mumbole and namulomo which are preferred for their good taste, the local fruits that are most preferred by the Lozi people are those that have several uses such as mubula, which is used for making porridge, scones called manyende, and a drink known as maheu. Nuts are added as an alternative to groundnuts. Muzauli is added to relishes as an alternative to groundnuts or as a source of cooking oil, and mukuwa may be made into a drink.

The staple food of Zambia nshima is eaten by the Lozi as well, although it is called buhobe .

Information about COVID-19

Tracing the origins, development and status of lozi language: a socio- linguistics and african oral literature perspective.

By kibabii / November 6, 2016

Muyendekwa Limbali

The University of Zambia

5.1 Abstract

The study traces the origin of Lozi language of the Western Province and other areas where the language is and was spoken since its origin is oblique or obscure. This study reviews a number of studies by different scholars who have different interpretations about the origin of Lozi language. Some allude to the fact that the Lozi language is a dialect of Southern Sotho, the language of the conquerors under Sebitwane. The Lozi people themselves claim that they were the first inhabitants of the plains and that they have always been there. They also point their ancestry to the union between Nyambe and the female ancestress Mbuyu. Others trace the Lozi origin to the Mwata Yamvo dynasty of the old Lunda Kingdom in the Katanga area of the Congo. Today, the Lozi themselves say that there is practically no Lozi who is pure Luyi and so they point their ancestry to Nkoya, Kwangwa, Subiya, Totela, Mbunda, Kololo among other languages. This can be attributed to intermarriages and dominance over small languages which they later assimilate hence failing to trace their own source. Many have come with their assertions on the origin and development of the Lozi originally called the A-Luyi or Luyana people. Lozi is spoken in many parts of Zambia and even beyond borders and it enjoys its status as the economic language of Western Province and one of the seven official languages on radio and medium of instruction in schools. It has also developed orthographically. These are some of the developments shown in the origin of Lozi language. The origin of the language is traced even in Angola, Zimbabwe as observed by Jacottet and Coillard that there is link between Shona and Siluyana but disputed by Fortune who says that there is no link between Siluyana and Shona. Jacottet points to Angola and not Congo but also disputed by Lozi people who deny any ethnological connections and say they understand Mbunda and various Angolan languages because of geographical proximity only.

5.2 Introduction

This article is drawn from the study conducted about the origins, development and status of the Lozi Language following contentious claims among some tribal groups occupying the Western Province of Zambia .

5.3 The Origin and Development of the Lozi language

Lozi language is one of the languages widely spoken throughout Western Province of Zambia and is one of the seven national languages of the country. The population of its native is estimated at more than one million people but many speak and understand it as their second or third language. It is also spoken in the Portuguese territory of Angola, Namibia mainly Caprivi strip, Botswana, and parts of South Africa. The Western Province is divided into six administrative districts namely: Mongu, Senanga, Kaoma, Sesheke, Kalabo and Lukulu. As noted earlier, this language has an extra ordinary history and different scholars have advanced varying explanations on the origin of Lozi language. For instance, Mutumba (1973) claims thus:

The name Lozi (usually spelt Rotse by the missionaries, travellers and early administration and hence Barotse Province instead of Bulozi Province) is a collective name for several small tribes of similar cultural and linguistic character who comprised the Lozi Kingdom. The exact origin of this collective name is unknown although there are a number of traditions surrounding it. It is invariably said that the Ma-Lozi were the founders of the present ruling dynasty in Bulozi, and their name was passed on to cover the whole group of tribes which they absorbed into their state (Mutumba 1973:5).

There is the tendency among the people of Western Province to call the royal family and the aristocracy as ‘Ma Lozi’ as opposed to the common people. To better understand the origin of Lozi language, we look at the origin of the term Bantu. According to Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel Bleek (1827-1875), the term Bantu is traced to South African languages other than the languages of the Bushmen and Hottentots, which means people. It is rendered ‘abantu’ in the Nguni dialects and bato in Tswana. Nowadays, Bantu refers to languages which have a common ancestry. This is due to the fact that language is dynamic and hence changes in time and space. It is worth noting that, although the term was coined to refer to a family of languages, it also applies to peoples speaking Bantu languages as ‘mother tongues’ and to anything thought to be characteristic of such peoples; hence such phrases as Bantu culture. According to Greenberg, the Bantu people and languages originated in and spread from the Cameroon-Nigeria border area. According to Guthrie, the Bantu people and languages originated in and spread from the Congo basin. Most scholars favour Greenberg’s Theory (Bryant, 1965). What Guthrie says in essence is that Proto-Bantu was spoken somewhere in the Congo Basin. Fage and Oliver (1962), in their short History of Africa, expressed a view similar to Guthrie’s Theory. They suggested that the earliest Bantu speaking people may have been hunters and fishermen and moved along the Congo and encountered and adopted the cultivated plants of their earliest traders and migrants from the South East Asia.

The assertion by Greenberg and Guthrie could be true to some extent because of proximity between the Cameroon-Nigeria borders and Congo Basin where Bantu are believed to have originated from. It could be concluded that Lozi could have come from one of these areas. Another variant of tradition; however, says that the people known as ‘Ma-Lozi today were originally known as ‘A-Luyi’ or ‘Aluyana’ until the 19th Century. In the middle of the 19th Century, the ‘A-Luyi’ or ‘Aluyana’ were conquered by the Makololo, a people of Sotho stock from the South, and it is alleged that the A-luyi were given the name of ‘Ma-Lozi’ by the Makololo. Both traditions seem feasible but the latter emerges more strongly when it is realised that the core of the Lozi Kingship which struggled to remain unchanged despite the Makololo influence and other external forces, uses as an official language at court a language known as ‘Siluyana’. Moreover, there are numerous tribal groups in Bulozi who were there long before the Makololo invasion and whose dialects are very closely related to Siluyana. In this study both names, A-luyi (or Luyana) and Ma-Lozi, are used (Mutumba 1973).

The name Lozi is of comparatively recent origin. Formerly the people were known as Aluyi or Aluyana. The Lozi people, who are the dominant tribe in the region of North-Western Rhodesia usually called Barotseland live in a great flood plain since the Luyi liberated their country from the Kololo, but retained the Kololo language. Rotse has become Lozi, in accordance with regular phonetic changes of r to l and s to z . The surface similarity of Rotse with Hurutshe, the parent stock of the Tswana, and with Rozwi, the dominant ‘shona’ group has led some anthropologists to relate the Luyi to these peoples in the South. But the Lozi’s own legends and the ethnological linguistic and ethnological evidence undoubtedly give them a northern origin, probably in a region of great watershed plains cut by rivers, somewhere about Lake Dilolo (Colson and Gluckman 1968:1)

The Lozi themselves say they are kin to the Lunda. They do not claim decent from the great Lunda King Mwatayamvo, but they say they and the Lunda descended from Mbuyawamwambwa, the daughter and wife of god Nyambe. According to Yukawa (1987), one main reason why Siluyana lost its vocabulary can be observed as follows;