An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature

Marc Lochbaum

1 Department of Kinesiology and Sport Management, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America

2 Education Academy, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania

Elisabeth Stoner

3 Department of Psychological Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America

Tristen Hefner

Sydney cooper.

4 Department of Kinesiology and Sport Management, Honors College, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America

Andrew M. Lane

5 Faculty of Education, Health and Well-Being, University of Wolverhampton, Walsall, West Midlands, United Kingdom

Peter C. Terry

6 Division of Research & Innovation, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia

Associated Data

All relevant data are within the paper.

Sport psychology as an academic pursuit is nearly two centuries old. An enduring goal since inception has been to understand how psychological techniques can improve athletic performance. Although much evidence exists in the form of meta-analytic reviews related to sport psychology and performance, a systematic review of these meta-analyses is absent from the literature. We aimed to synthesize the extant literature to gain insights into the overall impact of sport psychology on athletic performance. Guided by the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews, we reviewed relevant articles identified via the EBSCOhost interface. Thirty meta-analyses published between 1983 and 2021 met the inclusion criteria, covering 16 distinct sport psychology constructs. Overall, sport psychology interventions/variables hypothesized to enhance performance (e.g., cohesion, confidence, mindfulness) were shown to have a moderate beneficial effect ( d = 0.51), whereas variables hypothesized to be detrimental to performance (e.g., cognitive anxiety, depression, ego climate) had a small negative effect ( d = -0.21). The quality rating of meta-analyses did not significantly moderate the magnitude of observed effects, nor did the research design (i.e., intervention vs. correlation) of the primary studies included in the meta-analyses. Our review strengthens the evidence base for sport psychology techniques and may be of great practical value to practitioners. We provide recommendations for future research in the area.

Introduction

Sport performance matters. Verifying its global importance requires no more than opening a newspaper to the sports section, browsing the internet, looking at social media outlets, or scanning abundant sources of sport information. Sport psychology is an important avenue through which to better understand and improve sport performance. To date, a systematic review of published sport psychology and performance meta-analyses is absent from the literature. Given the undeniable importance of sport, the history of sport psychology in academics since 1830, and the global rise of sport psychology journals and organizations, a comprehensive systematic review of the meta-analytic literature seems overdue. Thus, we aimed to consolidate the existing literature and provide recommendations for future research.

The development of sport psychology

The history of sport psychology dates back nearly 200 years. Terry [ 1 ] cites Carl Friedrich Koch’s (1830) publication titled [in translation] Calisthenics from the Viewpoint of Dietetics and Psychology [ 2 ] as perhaps the earliest publication in the field, and multiple commentators have noted that sport psychology experiments occurred in the world’s first psychology laboratory, established by Wilhelm Wundt at the University of Leipzig in 1879 [ 1 , 3 ]. Konrad Rieger’s research on hypnosis and muscular endurance, published in 1884 [ 4 ] and Angelo Mosso’s investigations of the effects of mental fatigue on physical performance, published in 1891 [ 5 ] were other early landmarks in the development of applied sport psychology research. Following the efforts of Koch, Wundt, Rieger, and Mosso, sport psychology works appeared with increasing regularity, including Philippe Tissié’s publications in 1894 [ 6 , 7 ] on psychology and physical training, and Pierre de Coubertin’s first use of the term sport psychology in his La Psychologie du Sport paper in 1900 [ 8 ]. In short, the history of sport psychology and performance research began as early as 1830 and picked up pace in the latter part of the 19 th century. Early pioneers, who helped shape sport psychology include Wundt, recognized as the “father of experimental psychology”, Tissié, the founder of French physical education and Legion of Honor awardee in 1932, and de Coubertin who became the father of the modern Olympic movement and founder of the International Olympic Committee.

Sport psychology flourished in the early 20 th century [see 1, 3 for extensive historic details]. For instance, independent laboratories emerged in Berlin, Germany, established by Carl Diem in 1920; in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Russia, established respectively by Avksenty Puni and Piotr Roudik in 1925; and in Champaign, Illinois USA, established by Coleman Griffith, also in 1925. The period from 1950–1980 saw rapid strides in sport psychology, with Franklin Henry establishing this field of study as independent of physical education in the landscape of American and eventually global sport science and kinesiology graduate programs [ 1 ]. In addition, of great importance in the 1960s, three international sport psychology organizations were established: namely, the International Society for Sport Psychology (1965), the North American Society for the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity (1966), and the European Federation of Sport Psychology (1969). Since that time, the Association of Applied Sport Psychology (1986), the South American Society for Sport Psychology (1986), and the Asian-South Pacific Association of Sport Psychology (1989) have also been established.

The global growth in academic sport psychology has seen a large number of specialist publications launched, including the following journals: International Journal of Sport Psychology (1970), Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology (1979), The Sport Psychologist (1987), Journal of Applied Sport Psychology (1989), Psychology of Sport and Exercise (2000), International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology (2003), Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology (2007), International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology (2008), Journal of Sport Psychology in Action (2010), Sport , Exercise , and Performance Psychology (2014), and the Asian Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology (2021).

In turn, the growth in journal outlets has seen sport psychology publications burgeon. Indicative of the scale of the contemporary literature on sport psychology, searches completed in May 2021 within the Web of Science Core Collection, identified 1,415 publications on goal setting and sport since 1985; 5,303 publications on confidence and sport since 1961; and 3,421 publications on anxiety and sport since 1980. In addition to academic journals, several comprehensive edited textbooks have been produced detailing sport psychology developments across the world, such as Hanrahan and Andersen’s (2010) Handbook of Applied Sport Psychology [ 9 ], Schinke, McGannon, and Smith’s (2016) International Handbook of Sport Psychology [ 10 ], and Bertollo, Filho, and Terry’s (2021) Advancements in Mental Skills Training [ 11 ] to name just a few. In short, sport psychology is global in both academic study and professional practice.

Meta-analysis in sport psychology

Several meta-analysis guides, computer programs, and sport psychology domain-specific primers have been popularized in the social sciences [ 12 , 13 ]. Sport psychology academics have conducted quantitative reviews on much studied constructs since the 1980s, with the first two appearing in 1983 in the form of Feltz and Landers’ meta-analysis on mental practice [ 14 ], which included 98 articles dating from 1934, and Bond and Titus’ cross-disciplinary meta-analysis on social facilitation [ 15 ], which summarized 241 studies including Triplett’s (1898) often-cited study of social facilitation in cycling [ 16 ]. Although much meta-analytic evidence exists for various constructs in sport and exercise psychology [ 12 ] including several related to performance [ 17 ], the evidence is inconsistent. For example, two meta-analyses, both ostensibly summarizing evidence of the benefits to performance of task cohesion [ 18 , 19 ], produced very different mean effects ( d = .24 vs d = 1.00) indicating that the true benefit lies somewhere in a wide range from small to large. Thus, the lack of a reliable evidence base for the use of sport psychology techniques represents a significant gap in the knowledge base for practitioners and researchers alike. A comprehensive systematic review of all published meta-analyses in the field of sport psychology has yet to be published.

Purpose and aim

We consider this review to be both necessary and long overdue for the following reasons: (a) the extensive history of sport psychology and performance research; (b) the prior publication of many meta-analyses summarizing various aspects of sport psychology research in a piecemeal fashion [ 12 , 17 ] but not its totality; and (c) the importance of better understanding and hopefully improving sport performance via the use of interventions based on solid evidence of their efficacy. Hence, we aimed to collate and evaluate this literature in a systematic way to gain improved understanding of the impact of sport psychology variables on sport performance by construct, research design, and meta-analysis quality, to enhance practical knowledge of sport psychology techniques and identify future lines of research inquiry. By systematically reviewing all identifiable meta-analytic reviews linking sport psychology techniques with sport performance, we aimed to evaluate the strength of the evidence base underpinning sport psychology interventions.

Materials and methods

This systematic review of meta-analyses followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 20 ]. We did not register our systematic review protocol in a database. However, we specified our search strategy, inclusion criteria, data extraction, and data analyses in advance of writing our manuscript. All details of our work are available from the lead author. Concerning ethics, this systematic review received a waiver from Texas Tech University Human Subject Review Board as it concerned archival data (i.e., published meta-analyses).

Eligibility criteria

Published meta-analyses were retained for extensive examination if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) included meta-analytic data such as mean group, between or within-group differences or correlates; (b) published prior to January 31, 2021; (c) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (d) investigated a recognized sport psychology construct; and (e) meta-analyzed data concerned with sport performance. There was no language of publication restriction. To align with our systematic review objectives, we gave much consideration to study participants and performance outcomes. Across multiple checks, all authors confirmed study eligibility. Three authors (ML, AL, and PT) completed the final inclusion assessments.

Information sources

Authors searched electronic databases, personal meta-analysis history, and checked with personal research contacts. Electronic database searches occurred in EBSCOhost with the following individual databases selected: APA PsycINFO, ERIC, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and SPORTDiscus. An initial search concluded October 1, 2020. ML, AL, and PT rechecked the identified studies during the February–March, 2021 period, which resulted in the identification of two additional meta-analyses [ 21 , 22 ].

Search protocol

ML and ES initially conducted independent database searches. For the first search, ML used the following search terms: sport psychology with meta-analysis or quantitative review and sport and performance or sport* performance. For the second search, ES utilized a sport psychology textbook and used the chapter title terms (e.g., goal setting). In EBSCOhost, both searches used the advanced search option that provided three separate boxes for search terms such as box 1 (sport psychology), box 2 (meta-analysis), and box 3 (performance). Specific details of our search strategy were:

Search by ML:

- sport psychology, meta-analysis, sport and performance

- sport psychology, meta-analysis or quantitative review, sport* performance

- sport psychology, quantitative review, sport and performance

- sport psychology, quantitative review, sport* performance

Search by ES:

- mental practice or mental imagery or mental rehearsal and sports performance and meta-analysis

- goal setting and sports performance and meta-analysis

- anxiety and stress and sports performance and meta-analysis

- competition and sports performance and meta-analysis

- diversity and sports performance and meta-analysis

- cohesion and sports performance and meta-analysis

- imagery and sports performance and meta-analysis

- self-confidence and sports performance and meta-analysis

- concentration and sports performance and meta-analysis

- athletic injuries and sports performance and meta-analysis

- overtraining and sports performance and meta-analysis

- children and sports performance and meta-analysis

The following specific search of the EBSCOhost with SPORTDiscus, APA PsycINFO, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and ERIC databases, returned six results from 2002–2020, of which three were included [ 18 , 19 , 23 ] and three were excluded because they were not meta-analyses.

- Box 1 cohesion

- Box 2 sports performance

- Box 3 meta-analysis

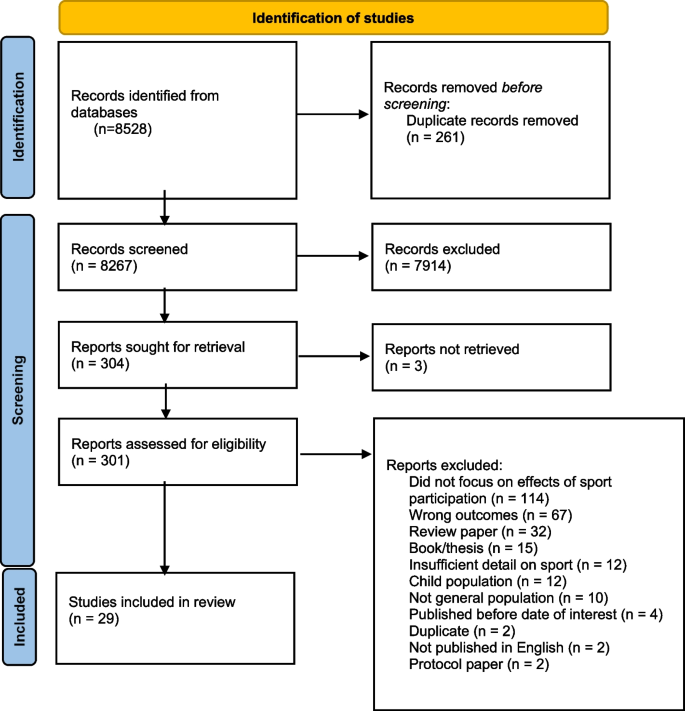

Study selection

As detailed in the PRISMA flow chart ( Fig 1 ) and the specified inclusion criteria, a thorough study selection process was used. As mentioned in the search protocol, two authors (ML and ES) engaged independently with two separate searches and then worked together to verify the selected studies. Next, AL and PT examined the selected study list for accuracy. ML, AL, and PT, whilst rating the quality of included meta-analyses, also re-examined all selected studies to verify that each met the predetermined study inclusion criteria. Throughout the study selection process, disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Data extraction process

Initially, ML, TH, and ES extracted data items 1, 2, 3 and 8 (see Data items). Subsequently, ML, AL, and PT extracted the remaining data (items 4–7, 9, 10). Checks occurred during the extraction process for potential discrepancies (e.g., checking the number of primary studies in a meta-analysis). It was unnecessary to contact any meta-analysis authors for missing information or clarification during the data extraction process because all studies reported the required information. Across the search for meta-analyses, all identified studies were reported in English. Thus, no translation software or searching out a native speaker occurred. All data extraction forms (e.g., data items and individual meta-analysis quality) are available from the first author.

To help address our main aim, we extracted the following information from each meta-analysis: (1) author(s); (2) publication year; (3) construct(s); (4) intervention based meta-analysis (yes, no, mix); (5) performance outcome(s) description; (6) number of studies for the performance outcomes; (7) participant description; (8) main findings; (9) bias correction method/results; and (10) author(s) stated conclusions. For all information sought, we coded missing information as not reported.

Individual meta-analysis quality

ML, AL, and PT independently rated the quality of individual meta-analysis on the following 25 points found in the PRISMA checklist [ 20 ]: title; abstract structured summary; introduction rationale, objectives, and protocol and registration; methods eligibility criteria, information sources, search, study selection, data collection process, data items, risk of bias of individual studies, summary measures, synthesis of results, and risk of bias across studies; results study selection, study characteristics, risk of bias within studies, results of individual studies, synthesis of results, and risk of bias across studies; discussion summary of evidence, limitations, and conclusions; and funding. All meta-analyses were rated for quality by two coders to facilitate inter-coder reliability checks, and the mean quality ratings were used in subsequent analyses. One author (PT), having completed his own ratings, received the incoming ratings from ML and AL and ran the inter-coder analysis. Two rounds of ratings occurred due to discrepancies for seven meta-analyses, mainly between ML and AL. As no objective quality categorizations (i.e., a point system for grouping meta-analyses as poor, medium, good) currently exist, each meta-analysis was allocated a quality score of up to a maximum of 25 points. All coding records are available upon request.

Planned methods of analysis

Several preplanned methods of analysis occurred. We first assessed the mean quality rating of each meta-analysis based on our 25-point PRISMA-based rating system. Next, we used a median split of quality ratings to determine whether standardized mean effects (SMDs) differed by the two formed categories, higher and lower quality meta-analyses. Meta-analysis authors reported either of two different effect size metrics (i.e., r and SMD); hence we converted all correlational effects to SMD (i.e., Cohen’s d ) values using an online effect size calculator ( www.polyu.edu.hk/mm/effectsizefaqs/calculator/calculator.html ). We interpreted the meaningfulness of effects based on Cohen’s interpretation [ 24 ] with 0.20 as small, 0.50 as medium, 0.80 as large, and 1.30 as very large. As some psychological variables associate negatively with performance (e.g., confusion [ 25 ], cognitive anxiety [ 26 ]) whereas others associate positively (e.g., cohesion [ 23 ], mental practice [ 14 ]), we grouped meta-analyses according to whether the hypothesized effect with performance was positive or negative, and summarized the overall effects separately. By doing so, we avoided a scenario whereby the demonstrated positive and negative effects canceled one another out when combined. The effect of somatic anxiety on performance, which is hypothesized to follow an inverted-U relationship, was categorized as neutral [ 35 ]. Last, we grouped the included meta-analyses according to whether the primary studies were correlational in nature or involved an intervention and summarized these two groups of meta-analyses separately.

Study characteristics

Table 1 contains extracted data from 30 meta-analyses meeting the inclusion criteria, dating from 1983 [ 14 ] to 2021 [ 21 ]. The number of primary studies within the meta-analyses ranged from three [ 27 ] to 109 [ 28 ]. In terms of the description of participants included in the meta-analyses, 13 included participants described simply as athletes, whereas other meta-analyses identified a mix of elite athletes (e.g., professional, Olympic), recreational athletes, college-aged volunteers (many from sport science departments), younger children to adolescents, and adult exercisers. Of the 30 included meta-analyses, the majority ( n = 18) were published since 2010. The decadal breakdown of meta-analyses was 1980–1989 ( n = 1 [ 14 ]), 1990–1999 ( n = 6 [ 29 – 34 ]), 2000–2009 ( n = 5 [ 23 , 25 , 26 , 35 , 36 ]), 2010–2019 ( n = 12 [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 27 , 37 – 43 , 48 ]), and 2020–2021 ( n = 6 [ 21 , 28 , 44 – 47 ]).

As for the constructs covered, we categorized the 30 meta-analyses into the following areas: mental practice/imagery [ 14 , 29 , 30 , 42 , 46 , 47 ], anxiety [ 26 , 31 , 32 , 35 ], confidence [ 26 , 35 , 36 ], cohesion [ 18 , 19 , 23 ], goal orientation [ 22 , 44 , 48 ], mood [ 21 , 25 , 34 ], emotional intelligence [ 40 ], goal setting [ 33 ], interventions [ 37 ], mindfulness [ 27 ], music [ 28 ], neurofeedback training [ 43 ], perfectionism [ 39 ], pressure training [ 45 ], quiet eye training [ 41 ], and self-talk [ 38 ]. Multiple effects were generated from meta-analyses that included more than one construct (e.g., tension, depression, etc. [ 21 ]; anxiety and confidence [ 26 ]). In relation to whether the meta-analyses included in our review assessed the effects of a sport psychology intervention on performance or relationships between psychological constructs and performance, 13 were intervention-based, 14 were correlational, two included a mix of study types, and one included a large majority of cross-sectional studies ( Table 1 ).

A wide variety of performance outcomes across many sports was evident, such as golf putting, dart throwing, maximal strength, and juggling; or categorical outcomes such as win/loss and Olympic team selection. Given the extensive list of performance outcomes and the incomplete descriptions provided in some meta-analyses, a clear categorization or count of performance types was not possible. Sufficient to conclude, researchers utilized many performance outcomes across a wide range of team and individual sports, motor skills, and strength and aerobic tasks.

Effect size data and bias correction

To best summarize the effects, we transformed all correlations to SMD values (i.e., Cohen’s d ). Across all included meta-analyses shown in Table 2 and depicted in Fig 2 , we identified 61 effects. Having corrected for bias, effect size values were assessed for meaningfulness [ 24 ], which resulted in 15 categorized as negligible (< ±0.20), 29 as small (±0.20 to < 0.50), 13 as moderate (±0.50 to < 0.80), 2 as large (±0.80 to < 1.30), and 1 as very large (≥ 1.30).

Study quality rating results and summary analyses

Following our PRISMA quality ratings, intercoder reliability coefficients were initially .83 (ML, AL), .95 (ML, PT), and .90 (AL, PT), with a mean intercoder reliability coefficient of .89. To achieve improved reliability (i.e., r mean > .90), ML and AL re-examined their ratings. As a result, intercoder reliability increased to .98 (ML, AL), .96 (ML, PT), and .92 (AL, PT); a mean intercoder reliability coefficient of .95. Final quality ratings (i.e., the mean of two coders) ranged from 13 to 25 ( M = 19.03 ± 4.15). Our median split into higher ( M = 22.83 ± 1.08, range 21.5–25, n = 15) and lower ( M = 15.47 ± 2.42, range 13–20.5, n = 15) quality groups produced significant between-group differences in quality ( F 1,28 = 115.62, p < .001); hence, the median split met our intended purpose. The higher quality group of meta-analyses were published from 2015–2021 (median 2018) and the lower quality group from 1983–2014 (median 2000). It appears that meta-analysis standards have risen over the years since the PRISMA criteria were first introduced in 2009. All data for our analyses are shown in Table 2 .

Table 3 contains summary statistics with bias-corrected values used in the analyses. The overall mean effect for sport psychology constructs hypothesized to have a positive impact on performance was of moderate magnitude ( d = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.42, 0.58, n = 36). The overall mean effect for sport psychology constructs hypothesized to have a negative impact on performance was small in magnitude ( d = -0.21, 95% CI -0.31, -0.11, n = 24). In both instances, effects were larger, although not significantly so, among meta-analyses of higher quality compared to those of lower quality. Similarly, mean effects were larger but not significantly so, where reported effects in the original studies were based on interventional rather than correlational designs. This trend only applied to hypothesized positive effects because none of the original studies in the meta-analyses related to hypothesized negative effects used interventional designs.

Note. k = number of effects, N.S. = non-significant, n/a = not applicable.

In this systematic review of meta-analyses, we synthesized the available evidence regarding effects of sport psychology interventions/constructs on sport performance. We aimed to consolidate the literature, evaluate the potential for meta-analysis quality to influence the results, and suggest recommendations for future research at both the single study and quantitative review stages. During the systematic review process, several meta-analysis characteristics came to light, such as the number of meta-analyses of sport psychology interventions (experimental designs) compared to those summarizing the effects of psychological constructs (correlation designs) on performance, the number of meta-analyses with exclusively athletes as participants, and constructs featuring in multiple meta-analyses, some of which (e.g., cohesion) produced very different effect size values. Thus, although our overall aim was to evaluate the strength of the evidence base for use of psychological interventions in sport, we also discuss the impact of these meta-analysis characteristics on the reliability of the evidence.

When seen collectively, results of our review are supportive of using sport psychology techniques to help improve performance and confirm that variations in psychological constructs relate to variations in performance. For constructs hypothesized to have a positive effect on performance, the mean effect strength was moderate ( d = 0.51) although there was substantial variation between constructs. For example, the beneficial effects on performance of task cohesion ( d = 1.00) and self-efficacy ( d = 0.82) are large, and the available evidence base for use of mindfulness interventions suggests a very large beneficial effect on performance ( d = 1.35). Conversely, some hypothetically beneficial effects (2 of 36; 5.6%) were in the negligible-to-small range (0.15–0.20) and most beneficial effects (19 of 36; 52.8%) were in the small-to-moderate range (0.22–0.49). It should be noted that in the world of sport, especially at the elite level, even a small beneficial effect on performance derived from a psychological intervention may prove the difference between success and failure and hence small effects may be of great practical value. To put the scale of the benefits into perspective, an authoritative and extensively cited review of healthy eating and physical activity interventions [ 49 ] produced an overall pooled effect size of 0.31 (compared to 0.51 for our study), suggesting sport psychology interventions designed to improve performance are generally more effective than interventions designed to promote healthy living.

Among hypothetically negative effects (e.g., ego climate, cognitive anxiety, depression), the mean detrimental effect was small ( d = -0.21) although again substantial variation among constructs was evident. Some hypothetically negative constructs (5 of 24; 20.8%) were found to actually provide benefits to performance, albeit in the negligible range (0.02–0.12) and only two constructs (8.3%), both from Lochbaum and colleagues’ POMS meta-analysis [ 21 ], were shown to negatively affect performance above a moderate level (depression: d = -0.64; total mood disturbance, which incorporates the depression subscale: d = -0.84). Readers should note that the POMS and its derivatives assess six specific mood dimensions rather than the mood construct more broadly, and therefore results should not be extrapolated to other dimensions of mood [ 50 ].

Mean effects were larger among higher quality than lower quality meta-analyses for both hypothetically positive ( d = 0.54 vs d = 0.45) and negative effects ( d = -0.25 vs d = 0.17), but in neither case were the differences significant. It is reasonable to assume that the true effects were derived from the higher quality meta-analyses, although our conclusions remain the same regardless of study quality. Overall, our findings provide a more rigorous evidence base for the use of sport psychology techniques by practitioners than was previously available, representing a significant contribution to knowledge. Moreover, our systematic scrutiny of 30 meta-analyses published between 1983 and 2021 has facilitated a series of recommendations to improve the quality of future investigations in the sport psychology area.

Recommendations

The development of sport psychology as an academic discipline and area of professional practice relies on using evidence and theory to guide practice. Hence, a strong evidence base for the applied work of sport psychologists is of paramount importance. Although the beneficial effects of some sport psychology techniques are small, it is important to note the larger performance benefits for other techniques, which may be extremely meaningful for applied practice. Overall, however, especially given the heterogeneity of the observed effects, it would be wise for applied practitioners to avoid overpromising the benefits of sport psychology services to clients and perhaps underdelivering as a result [ 1 ].

The results of our systematic review can be used to generate recommendations for how the profession might conduct improved research to better inform applied practice. Much of the early research in sport psychology was exploratory and potential moderating variables were not always sufficiently controlled. Terry [ 51 ] outlined this in relation to the study of mood-performance relationships, identifying that physical and skills factors will very likely exert a greater influence on performance than psychological factors. Further, type of sport (e.g., individual vs. team), duration of activity (e.g., short vs. long duration), level of competition (e.g., elite vs. recreational), and performance measure (e.g., norm-referenced vs. self-referenced) have all been implicated as potential moderators of the relationship between psychological variables and sport performance [ 51 ]. To detect the relatively subtle effects of psychological effects on performance, research designs need to be sufficiently sensitive to such potential confounds. Several specific methodological issues are worth discussing.

The first issue relates to measurement. Investigating the strength of a relationship requires the measured variables to be valid, accurate and reliable. Psychological variables in the meta-analyses we reviewed relied primarily on self-report outcome measures. The accuracy of self-report data requires detailed inner knowledge of thoughts, emotions, and behavior. Research shows that the accuracy of self-report information is subject to substantial individual differences [ 52 , 53 ]. Therefore, self-report data, at best, are an estimate of the measure. Measurement issues are especially relevant to the assessment of performance, and considerable measurement variation was evident between meta-analyses. Some performance measures were more sensitive, especially those assessing physical performance relative to what is normal for the individual performer (i.e., self-referenced performance). Hence, having multiple baseline indicators of performance increases the probability of identifying genuine performance enhancement derived from a psychological intervention [ 54 ].

A second issue relates to clarifying the rationale for how and why specific psychological variables might influence performance. A comprehensive review of prerequisites and precursors of athletic talent [ 55 ] concluded that the superiority of Olympic champions over other elite athletes is determined in part by a range of psychological variables, including high intrinsic motivation, determination, dedication, persistence, and creativity, thereby identifying performance-related variables that might benefit from a psychological intervention. Identifying variables that influence the effectiveness of interventions is a challenging but essential issue for researchers seeking to control and assess factors that might influence results [ 49 ]. A key part of this process is to use theory to propose the mechanism(s) by which an intervention might affect performance and to hypothesize how large the effect might be.

A third issue relates to the characteristics of the research participants involved. Out of convenience, it is not uncommon for researchers to use undergraduate student participants for research projects, which may bias results and restrict the generalization of findings to the population of primary interest, often elite athletes. The level of training and physical conditioning of participants will clearly influence their performance. Highly trained athletes will typically make smaller gains in performance over time than novice athletes, due to a ceiling effect (i.e., they have less room for improvement). For example, consider runner A, who takes 20 minutes to run 5km one week but 19 minutes the next week, and Runner B who takes 30 minutes one week and 25 minutes the next. If we compare the two, Runner A runs faster than Runner B on both occasions, but Runner B improved more, so whose performance was better? If we also consider Runner C, a highly trained athlete with a personal best of 14 minutes, to run 1 minute quicker the following week would almost require a world record time, which is clearly unlikely. For this runner, an improvement of a few seconds would represent an excellent performance. Evidence shows that trained, highly motivated athletes may reach performance plateaus and as such are good candidates for psychological skills training. They are less likely to make performance gains due to increased training volume and therefore the impact of psychological skills interventions may emerge more clearly. Therefore, both test-retest and cross-sectional research designs should account for individual difference variables. Further, the range of individual difference factors will be context specific; for example, individual differences in strength will be more important in a study that uses weightlifting as the performance measure than one that uses darts as the performance measure, where individual differences in skill would be more important.

A fourth factor that has not been investigated extensively relates to the variables involved in learning sport psychology techniques. Techniques such as imagery, self-talk and goal setting all require cognitive processing and as such some people will learn them faster than others [ 56 ]. Further, some people are intuitive self-taught users of, for example, mood regulation strategies such as abdominal breathing or listening to music who, if recruited to participate in a study investigating the effects of learning such techniques on performance, would respond differently to novice users. Hence, a major challenge when testing the effects of a psychological intervention is to establish suitable controls. A traditional non-treatment group offers one option, but such an approach does not consider the influence of belief effects (i.e., placebo/nocebo), which can either add or detract from the effectiveness of performance interventions [ 57 ]. If an individual believes that, an intervention will be effective, this provides a motivating effect for engagement and so performance may improve via increased effort rather than the effect of the intervention per se.

When there are positive beliefs that an intervention will work, it becomes important to distinguish belief effects from the proposed mechanism through which the intervention should be successful. Research has shown that field studies often report larger effects than laboratory studies, a finding attributed to higher motivation among participants in field studies [ 58 ]. If participants are motivated to improve, being part of an active training condition should be associated with improved performance regardless of any intervention. In a large online study of over 44,000 participants, active training in sport psychology interventions was associated with improved performance, but only marginally more than for an active control condition [ 59 ]. The study involved 4-time Olympic champion Michael Johnson narrating both the intervention and active control using motivational encouragement in both conditions. Researchers should establish not only the expected size of an effect but also to specify and assess why the intervention worked. Where researchers report performance improvement, it is fundamental to explain the proposed mechanism by which performance was enhanced and to test the extent to which the improvement can be explained by the proposed mechanism(s).

Limitations

Systematic reviews are inherently limited by the quality of the primary studies included. Our review was also limited by the quality of the meta-analyses that had summarized the primary studies. We identified the following specific limitations; (1) only 12 meta-analyses summarized primary studies that were exclusively intervention-based, (2) the lack of detail regarding control groups in the intervention meta-analyses, (3) cross-sectional and correlation-based meta-analyses by definition do not test causation, and therefore provide limited direct evidence of the efficacy of interventions, (4) the extensive array of performance measures even within a single meta-analysis, (5) the absence of mechanistic explanations for the observed effects, and (6) an absence of detail across intervention-based meta-analyses regarding number of sessions, participants’ motivation to participate, level of expertise, and how the intervention was delivered. To ameliorate these concerns, we included a quality rating for all included meta-analyses. Having created higher and lower quality groups using a median split of quality ratings, we showed that effects were larger, although not significantly so, in the higher quality group of meta-analyses, all of which were published since 2015.

Conclusions

Journals are full of studies that investigate relationships between psychological variables and sport performance. Since 1983, researchers have utilized meta-analytic methods to summarize these single studies, and the pace is accelerating, with six relevant meta-analyses published since 2020. Unquestionably, sport psychology and performance research is fraught with limitations related to unsophisticated experimental designs. In our aggregation of the effect size values, most were small-to-moderate in meaningfulness with a handful of large values. Whether these moderate and large values could be replicated using more sophisticated research designs is unknown. We encourage use of improved research designs, at the minimum the use of control conditions. Likewise, we encourage researchers to adhere to meta-analytic guidelines such as PRISMA and for journals to insist on such adherence as a prerequisite for the acceptance of reviews. Although such guidelines can appear as a ‘painting by numbers’ approach, while reviewing the meta-analyses, we encountered difficulty in assessing and finding pertinent information for our study characteristics and quality ratings. In conclusion, much research exists in the form of quantitative reviews of studies published since 1934, almost 100 years after the very first publication about sport psychology and performance [ 2 ]. Sport psychology is now truly global in terms of academic pursuits and professional practice and the need for best practice information plus a strong evidence base for the efficacy of interventions is paramount. We should strive as a profession to research and provide best practices to athletes and the general community of those seeking performance improvements.

Supporting information

S1 checklist, acknowledgments.

We acknowledge the work of all academics since Koch in 1830 [ 2 ] for their efforts to research and promote the practice of applied sport psychology.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability

- PLoS One. 2022; 17(2): e0263408.

Decision Letter 0

PONE-D-21-31186Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literaturePLOS ONE

Dear Dr. Lochbaum,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

Please submit your revised manuscript by Jan 21 2022 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

- A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

- A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

- An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols . Additionally, PLOS ONE offers an option for publishing peer-reviewed Lab Protocol articles, which describe protocols hosted on protocols.io. Read more information on sharing protocols at https://plos.org/protocols?utm_medium=editorial-email&utm_source=authorletters&utm_campaign=protocols .

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Claudio Imperatori, Ph.D

Academic Editor

Journal Requirements:

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=ba62/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_title_authors_affiliations.pdf

2. We noted in your submission details that a portion of your manuscript may have been presented or published elsewhere. [I believe our answer is no. In 2017, I spoke about meta-analyses and sport performance at the Kinesiology Conference in Croatia. This conference proceeding is appropriately referenced.] Please clarify whether this conference proceeding was peer-reviewed and formally published. If this work was previously peer-reviewed and published, in the cover letter please provide the reason that this work does not constitute dual publication and should be included in the current manuscript.

3. Please include your full ethics statement in the ‘Methods’ section of your manuscript file. In your statement, please include the full name of the IRB or ethics committee who approved or waived your study, as well as whether or not you obtained informed written or verbal consent. If consent was waived for your study, please include this information in your statement as well.

4. Please review your reference list to ensure that it is complete and correct. If you have cited papers that have been retracted, please include the rationale for doing so in the manuscript text, or remove these references and replace them with relevant current references. Any changes to the reference list should be mentioned in the rebuttal letter that accompanies your revised manuscript. If you need to cite a retracted article, indicate the article’s retracted status in the References list and also include a citation and full reference for the retraction notice.

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

The manuscript must describe a technically sound piece of scientific research with data that supports the conclusions. Experiments must have been conducted rigorously, with appropriate controls, replication, and sample sizes. The conclusions must be drawn appropriately based on the data presented.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Yes

2. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

3. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

The PLOS Data policy requires authors to make all data underlying the findings described in their manuscript fully available without restriction, with rare exception (please refer to the Data Availability Statement in the manuscript PDF file). The data should be provided as part of the manuscript or its supporting information, or deposited to a public repository. For example, in addition to summary statistics, the data points behind means, medians and variance measures should be available. If there are restrictions on publicly sharing data—e.g. participant privacy or use of data from a third party—those must be specified.

Reviewer #1: No

4. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

PLOS ONE does not copyedit accepted manuscripts, so the language in submitted articles must be clear, correct, and unambiguous. Any typographical or grammatical errors should be corrected at revision, so please note any specific errors here.

5. Review Comments to the Author

Please use the space provided to explain your answers to the questions above. You may also include additional comments for the author, including concerns about dual publication, research ethics, or publication ethics. (Please upload your review as an attachment if it exceeds 20,000 characters)

Reviewer #1: The paper entitled: “Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature” aimed to synthesize the extant literature to gain insights into the overall impact of sport psychology on athletic performance. The paper is well written and has a great and strong methodology. However, the introduction and discussion are not persuasive enough that the findings make a significant contribution to the literature and could therefore override these limitations. I include some comments below related to this summary for consideration.

1. In relation to the contribution of the study to the literature, I did not get a sense from the article that the findings revealed anything other than what we already know. Please clarified that;

2. The introduction of the paper was very descriptive, it did not situate the current study in literature or highlight what the gap in the literature is that this study is trying to address. At least, the authors should situate better the main purposes of this study;

3. The discussion is very descriptive and any statements about the contribution and conclusions of the study are not new. At least this moment. Please clarified better and justified your choices.

4. Overall, the paper has conditions for be accepted in PLOS ONE, however the authors should clarified the points above.

Reviewer #2: The submitted work presents a very interesting approach to summarize the results of systematic reviews/meta-analysis regarding sport psychology and performance. I must say that it is rare as a reviewer to find a so relevant and well developed study (particularly a review of literature) in which I can add and help so little. The authors are to be commended for the excellent work developed.

Given this, I can make 1 or 2 remarks in some sections, although I do not believe they are needed to ensure a final quality of the developed work. I believe this work can be published as it is, and my comments should only be considered if the authors feel they are noteworthy.

Lines 99 to 102. Given that several examples were presented before (e.g., journals), why the inclusion of only one book? Several examples could be given here, thus maintaining the line of reasoning presented before.

In method, why report PRISMA 2009, 2015 and 2020 guidelines? As stated in the Page et al (2020) reference used: "The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesis studies". Won't the 2020 reference be enough?

As a last remark, I wonder if a discussion (or a comment in the discussion/limitations) regarding mood, and particularly POMS, is needed. In this work and in some of the cited works (e.g., Lochbaum et al., 2021, EJIHPE) no discussion regarding the issues of POMS as an assessing tool for mood is presented. As mentioned by several researchers (e.g., Ekkekakis, 2013), POMS do not assess mood, at least not in a global domain. This do not impact directly this work, as generally only each of the six distinct states are explored. However, when interpreting figure 2 and extracting mood results, perhaps some clarification would frame the readers on this issues and respective interpretation of results.

Ekkekakis, P. (2013). The measurement of affect, mood and emotion. Cambridge University Press.

I am sorry I can not help any further with my comments. Thank you for your work.

Best regards

6. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article ( what does this mean? ). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

If you choose “no”, your identity will remain anonymous but your review may still be made public.

Do you want your identity to be public for this peer review? For information about this choice, including consent withdrawal, please see our Privacy Policy .

Reviewer #2: Yes: Diogo S. Teixeira

[NOTE: If reviewer comments were submitted as an attachment file, they will be attached to this email and accessible via the submission site. Please log into your account, locate the manuscript record, and check for the action link "View Attachments". If this link does not appear, there are no attachment files.]

While revising your submission, please upload your figure files to the Preflight Analysis and Conversion Engine (PACE) digital diagnostic tool, https://pacev2.apexcovantage.com/ . PACE helps ensure that figures meet PLOS requirements. To use PACE, you must first register as a user. Registration is free. Then, login and navigate to the UPLOAD tab, where you will find detailed instructions on how to use the tool. If you encounter any issues or have any questions when using PACE, please email PLOS at gro.solp@serugif . Please note that Supporting Information files do not need this step.

Author response to Decision Letter 0

13 Dec 2021

Response to Reviewers

Thank you to both reviewers for taking time to review and comment on our manuscript. We addressed all comments.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Yes

Author response: Thank you to the reviewers for their positive comments.

________________________________________

Reviewer #1: No

Author response: All pertinent data are found in Table 1 – 2 and in Figure 1.

Author response: Reviewer 1’s concerns have been addressed below.

Reviewer #1

The paper entitled: “Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature” aimed to synthesize the extant literature to gain insights into the overall impact of sport psychology on athletic performance. The paper is well written and has a great and strong methodology. However, the introduction and discussion are not persuasive enough that the findings make a significant contribution to the literature and could therefore override these limitations. I include some comments below related to this summary for consideration.

• Author response: We have amended the paper to address the three concerns below.

Comment 1. In relation to the contribution of the study to the literature, I did not get a sense from the article that the findings revealed anything other than what we already know. Please clarified that;

• Author response: We have expanded on the gap in the knowledge that we addressed on lines 115-121 on the revised manuscript.

Comment 2. The introduction of the paper was very descriptive, it did not situate the current study in literature or highlight what the gap in the literature is that this study is trying to address. At least, the authors should situate better the main purposes of this study;

• Author response: Currently, sport psychology practitioners wishing to use evidence-based strategies are faced with inconsistent evidence about the efficacy of sport psychology techniques. Our paper addresses this inconsistency by assessing the effectiveness of techniques collectively. This is explained on lines 115-121 and with some small modifications on lines 125-128.

Comment 3. The discussion is very descriptive and any statements about the contribution and conclusions of the study are not new. At least this moment. Please clarified better and justified your choices.

• Author response: As suggested, a stronger summary of the contribution of the paper is provided on lines 371-375. We would also argue that the recommendations section for improvements to future studies also represents a significant contribution to the body of knowledge. If the information provided is already well known, as the reviewer suggests, then we would question why previous investigators have not implemented it in their studies.

Comment 4. Overall, the paper has conditions for be accepted in PLOS ONE, however the authors should clarified the points above.

• Author response: We thank you for your comments, which have served to improve our paper.

Reviewer #2

The submitted work presents a very interesting approach to summarize the results of systematic reviews/meta-analysis regarding sport psychology and performance. I must say that it is rare as a reviewer to find a so relevant and well developed study (particularly a review of literature) in which I can add and help so little. The authors are to be commended for the excellent work developed.

• Author response: Many thanks for your extremely positive comments.

Comment 1. Given this, I can make 1 or 2 remarks in some sections, although I do not believe they are needed to ensure a final quality of the developed work. I believe this work can be published as it is, and my comments should only be considered if the authors feel they are noteworthy.

• Author response: As suggested, we have added some additional references to books on lines 99-104 and added them to the reference list on lines 523-524 and 527-529.

Comment 2. In method, why report PRISMA 2009, 2015 and 2020 guidelines? As stated in the Page et al (2020) reference used: "The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesis studies". Won't the 2020 reference be enough?

• Author response: As suggested, we have removed reference to the PRISMA guidelines published in 2009 and 2015.

Comment 3. As a last remark, I wonder if a discussion (or a comment in the discussion/limitations) regarding mood, and particularly POMS, is needed. In this work and in some of the cited works (e.g., Lochbaum et al., 2021, EJIHPE) no discussion regarding the issues of POMS as an assessing tool for mood is presented. As mentioned by several researchers (e.g., Ekkekakis, 2013), POMS do not assess mood, at least not in a global domain. This do not impact directly this work, as generally only each of the six distinct states are explored. However, when interpreting figure 2 and extracting mood results, perhaps some clarification would frame the readers on this issues and respective interpretation of results.

• Author response: It was not our intent to critique the construct validity of the measures used in the meta-analyses we reviewed. Nevertheless, as suggested, we have added a note that the POMS and its derivatives do not measure all aspects of the global domain of mood (see lines 364-366).

I am sorry I cannot help any further with my comments. Thank you for your work.

• Author response: We are delighted to know that you thought so highly of our paper.

Submitted filename: Response to Reviewers.docx

Decision Letter 1

19 Jan 2022

PONE-D-21-31186R1

We’re pleased to inform you that your manuscript has been judged scientifically suitable for publication and will be formally accepted for publication once it meets all outstanding technical requirements.

Within one week, you’ll receive an e-mail detailing the required amendments. When these have been addressed, you’ll receive a formal acceptance letter and your manuscript will be scheduled for publication.

An invoice for payment will follow shortly after the formal acceptance. To ensure an efficient process, please log into Editorial Manager at http://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ , click the 'Update My Information' link at the top of the page, and double check that your user information is up-to-date. If you have any billing related questions, please contact our Author Billing department directly at gro.solp@gnillibrohtua .

If your institution or institutions have a press office, please notify them about your upcoming paper to help maximize its impact. If they’ll be preparing press materials, please inform our press team as soon as possible -- no later than 48 hours after receiving the formal acceptance. Your manuscript will remain under strict press embargo until 2 pm Eastern Time on the date of publication. For more information, please contact gro.solp@sserpeno .

Additional Editor Comments (optional):

1. If the authors have adequately addressed your comments raised in a previous round of review and you feel that this manuscript is now acceptable for publication, you may indicate that here to bypass the “Comments to the Author” section, enter your conflict of interest statement in the “Confidential to Editor” section, and submit your "Accept" recommendation.

Reviewer #1: All comments have been addressed

Reviewer #2: All comments have been addressed

2. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

3. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

4. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

5. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

6. Review Comments to the Author

Reviewer #1: No more comments. The authors adressed all of my previous comments. Therefore, the manuscript must be accepted for publication. Congratulations.

Reviewer #2: (No Response)

7. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article ( what does this mean? ). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

Acceptance letter

25 Jan 2022

Dear Dr. Lochbaum:

I'm pleased to inform you that your manuscript has been deemed suitable for publication in PLOS ONE. Congratulations! Your manuscript is now with our production department.

If your institution or institutions have a press office, please let them know about your upcoming paper now to help maximize its impact. If they'll be preparing press materials, please inform our press team within the next 48 hours. Your manuscript will remain under strict press embargo until 2 pm Eastern Time on the date of publication. For more information please contact gro.solp@sserpeno .

If we can help with anything else, please email us at gro.solp@enosolp .

Thank you for submitting your work to PLOS ONE and supporting open access.

PLOS ONE Editorial Office Staff

on behalf of

Dr. Claudio Imperatori

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Athletes — Sports Psychology

Sports Psychology

- Categories: Athletes Motivation Social Psychology

About this sample

Words: 2762 |

14 min read

Published: Apr 11, 2019

Words: 2762 | Pages: 6 | 14 min read

Table of contents

Social learning theory, interactional theory, attribution theory.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Psychology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1651 words

2 pages / 717 words

6 pages / 2828 words

1 pages / 507 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Athletes

What makes a good athlete? This question has intrigued sports enthusiasts, coaches, and researchers alike for generations. The realm of sports is not only about physical prowess but also about mental strength, discipline, and [...]

Burns, C. (n.d.). Gay and Transgender People Face High Rates of Workplace Discrimination and Harassment. Center for American Progress. [...]

Moreau, Julie. 'No Link between Trans-inclusive Policies and Bathroom Safety, Study Finds.' NBC News, 2018.Radcliffe, Paula. Interview on BBC Radio 4. 2019.Rankin, Susan. 'Mind, Body, and Sport: Harassment and Discrimination – [...]

Jackie Robinson's life and legacy embody the values of courage, determination, and perseverance. Robinson's success in breaking the color barrier in baseball and advocating for social justice paved the way for future generations [...]

Cheerleading is in fact a sport, and claimed to be the hardest womens sport out there as they face many challenges. It pushes you to the limits and trains you everyday. Many people out there say that cheerleading is not a sport, [...]

Recently, doping in sports has become a huge problem. Doping is being used in sports in order to cheat the system and gain an unfair advantage against other competitors. Various careers were ruined in multiple sports as well as [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

What Is Sports Psychology? 9 Scientific Theories & Examples

And maintaining focus when your team is behind and heading into the final few minutes of the game requires mental toughness.

Sports are played by the body and won in the mind, says sports psychologist Aidan Moran (2012).

To provide an athlete with the mental support they need, a sports psychologist considers the individual’s feelings, thoughts, perceived obstacles, and behavior in training, competition, and their lives beyond.

This article introduces some of the key concepts, research, and theory behind sports psychology and its ability to optimize performance.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

What is sports psychology, 4 real-life examples, 5 theories and facts of sports psychology, why is sports psychology important, brief history of sports psychology, top 4 sports psychology podcasts, positivepsychology.com’s helpful resources, a take-home message.

“Sport psychology is about understanding the performance, mental processes, and wellbeing of people in sporting settings, taking into account psychological theory and methods.”

Meijen, 2019

Sports psychology is now widely accepted as offering a crucial edge over competitors. And while essential for continuing high performance in elite athletes, it also provides insights into optimizing functioning in areas of our lives beyond sports.

As a result, psychological processes and mental wellbeing have become increasingly recognized as vital to consistently high degrees of sporting performance for athletes at all levels where the individual is serious about pushing their limits.

Indeed, as cognitive scientist Massimiliano Cappuccio (2018) writes, “physical training and exercise are not sufficient to excel in competition.” Instead, key elements of the athlete’s mental preparation must be “perfectly tuned for the challenge.”

For example, in recent research attempting to understand endurance limits , psychological variables have been confirmed as the deciding factor in ceasing effort rather than muscular fatigue (Meijen, 2019). The brain literally limits the body.

Beyond endurance, mental processes are equally crucial in other aspects of sporting success, such as maintaining focus, overcoming injury, dealing with failure, and handling success.

As psychologists, we can help competitors enhance their performance by “providing advice on how to be their best when it matters most” (Moran, 2012).

Pushing from within

As long ago as 2008, Tiger Woods confirmed the importance of his mental strength and ability to push himself from within (Moran, 2012):

“It’s not about what other people think and what other people say. It’s about what you want to accomplish and do you want to go out there and be prepared to beat everyone you play or face?”

And golf experts agree. While Tiger Woods’s natural gifts are self-evident, you can never count him out when he is losing, because of his robust mindset. He is always prepared and always has a plan (Bastable, 2020).

Vision and the right mindset will overcome

When sports scientist and motivational expert Greg Whyte met Eddie Izzard, the British comedian didn’t even own a pair of running shoes. Yet Whyte had six weeks to prepare her for the monumental challenge of running 43 consecutive marathons.

Vision, belief, science-led training, psychological support, and Izzard’s epic degree of determination were the essential ingredients that resulted in success (Whyte, 2015).

Reframing arousal

When sports psychologist John Kremer was approached by an international sprinter complaining that pre-race anxiety was impacting his races, he took time to understand what he was experiencing and how it felt.

Kremer helped reframe the athlete’s perception of his pounding heart from stress negatively affecting his performance to being primed and ready for competition (Kremer, Moran, & Kearney, 2019).

Visualizing success

Diver Laura Wilkinson broke three bones in her foot in the lead-up to the U.S. trials for the 2000 Olympics.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Sports psychology is not one theory, but the combination of many overlapping ideas and concepts that attempt to understand what it takes to be a successful athlete.

Indeed, in many sports, endurance in particular, there has been a move toward more multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches, looking at the interactions between psychological, biomechanical, physiological, genetic, and training aspects of performance (Meijen, 2019).

With that in mind, and considering the many psychological constructs affecting performance in sports, the following areas are some of the most widely studied:

- Mental toughness

- Goal setting

- Anxiety and arousal

1. Mental toughness

Coaches and athletes recognize mental toughness as a psychological construct vital for performance success in training and competition (Gucciardi, Peeling, Ducker, & Dawson, 2016).

Mental toughness helps maintain consistency in determination, focus, and perceived control while under competitive pressure (Jones, Hanton, & Connaughton, 2002).

While much of the early work on mental toughness relied on the conceptual understanding of the related concepts of resilience and hardiness, reaching an agreed upon definition has proven difficult (Sutton, 2019).

Mentally tough athletes are highly competitive, committed, self-motivated , and able to cope effectively and maintain concentration in high-pressure situations. They retain a high degree of self-belief even after setbacks and persist when the going gets tough (Crust & Clough, 2005; Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

After interviewing sports professionals competing at an international level, Jones et al. (2002) found that being mentally tough takes an unshakeable self-belief in the ability to achieve goals and the capacity and determination to bounce back from performance setbacks.

Mental toughness determines “how people deal effectively with challenges, stressors, and pressure… irrespective of circumstances” (Crust & Clough, 2005). It is made up of four components, known to psychologists as the “four Cs”:

- Feeling in control when confronted with obstacles and difficult situations

- Commitment to goals

- Confidence in abilities and interpersonal skills

- Seeing challenges as opportunities

For athletes and sportspeople, mental toughness provides an advantage over opponents, enabling them to cope better with the demands of physical activity.

Beyond that, mental toughness allows individuals to manage stress better, overcome challenges, and perform optimally in everyday life.

2. Motivation

Motivation has been described as what maintains, sustains, directs, and channels behavior over an extended amount of time (Ryan & Deci, 2017). While it applies in all areas of life requiring commitment, it is particularly relevant in sports.

Not only does motivation impact an athlete’s ability to focus and achieve sporting excellence, but it is essential for the initial adoption and ongoing continuance of training (Sutton, 2019).

While there are several theories of motivation, the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) has proven one of the most popular (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Based on our inherent tendency toward growth, SDT suggests that activity is most likely when an individual feels intrinsically motivated, has a sense of volition over their behavior, and the activity feels inherently interesting and appealing.

Optimal performance in sports and elsewhere occurs when three basic needs are met: relatedness, competence, and autonomy (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

3. Goal setting and focus

Setting goals is an effective way to focus on the right activities, increase commitment, and energize the individual (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

Goal setting is also “associated with increased wellbeing and represents an individual’s striving to achieve personal self-change, enhanced meaning, and purpose in life” (Sheard, 2013).

A well-constructed goal can provide a mechanism to motivate the individual toward that goal. And something big can be broken down into a set of smaller, more manageable tasks that take us nearer to achieving the overall goal (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

Athletes can use goals to focus and direct attention toward actions that will lead to specific improvements; for example, a swimmer improves their kick to take 0.5 seconds off a 100-meter butterfly time or a runner increases their speed out of the blocks in a 100 meter sprint.

Goal setting can define challenging but achievable outcomes, whatever your sporting level or skills.

A specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound (SMART) goal should be clear, realistic, and possible. For example, a runner may set the following goal:

Next year, I want to run the New York City Marathon in three hours by completing a six-month training schedule provided by a coach .

4. Anxiety and arousal

Under extreme pressure and in situations perceived as important, athletes may perform worse than expected. This is known as choking and is typically caused by being overly anxious (Kremer et al., 2019).

Such anxiety can have cognitive (erratic thinking), physical (sweating, over-breathing), and behavioral (pacing, tensing, rapid speech) outcomes. It typically concerns something that is not currently happening, such as an upcoming race (Moran, 2012).

It is important to distinguish anxiety from arousal . The latter refers to a type of bodily energy that prepares us for action. It involves deep psychological and physiological activation, and is valuable in sports.

Therefore, if psychological and physiological activation is on a continuum from deep sleep to intense excitement , the sportsperson must aim for a perceived sweet spot to perform at their best. It will differ wildly between competitors; for one, it may be perceived as unpleasant anxiety, for another, nervous excitement.

The degree of anxiety is influenced by (Moran, 2012):

- Perceived importance of the event

- Trait anxiety

- Attributing outcomes to internal or external factors

- Perfectionism – setting impossibly high standards

- Fear of failure

- Lack of confidence

While the competitor needs a degree of pressure (or arousal) and nervous energy to perform at their best, too much may cause them to crumble. Sports psychologists work with sportspeople to better understand the pressure and help manage it through several techniques including:

- Visualization

- Breathing and slowing down

- Sticking to pre-performance routines

Ultimately, it may not be the amount of arousal that affects performance, but its interpretation.

5. Confidence

While lack of confidence is an essential factor in competition anxiety, it also plays a crucial role in mental toughness.

As Gaelic footballer Michael Nolan says, “it’s not who we are that holds us back; it’s who we think we’re not” (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

Confidence is ultimately a measure of how much self-belief we have to see through to the end something beset with setbacks.

Those with a high degree of self-confidence will recognize that obstacles are part of life and take them in stride. Those less confident may believe the world is set against them and feel defeated or prevented from completing their task (Clough & Strycharczyk, 2015).

Self-confidence also taps into other, similar self-regulatory beliefs such as staying positive and maintaining self-belief (Sheard, 2013). An athlete high in self-confidence will harness their degree of self-belief and meet the challenge head on.

However, there are risks associated with being too self-confident. Overconfidence in abilities can lead to taking on too much, intolerance, and the inability to see underdeveloped skills.

And yet, that can only ever be part of the success story.

Sports place tremendous pressure on the competitor’s mind in competition and in training, and that pressure must be supported by robust and reliable psychological constructs (Kumar & Shirotriya, 2010).

The abilities to maintain focus under such pressure and also control actions during extreme circumstances of uncertainty can be strengthened by the mental training and skills a sports psychologist provides.

Mental preparation helps ready the individual and team for competition and offers an edge over an adversary while optimizing performance.

Not only that, but the skills learned in sports psychology are transferable; we can take them to other domains such as education and the workplace.

Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz (2018) recognized the parallels between achieving “sustained high performance in the face of ever-increasing pressure and rapid change” in the workplace and on the sports field.

Perhaps the earliest known formal study of the mental processes involved in sports can be attributed to Triplett in 1898.