An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Introduction to qualitative research methods – Part I

Shagufta bhangu, fabien provost, carlo caduff.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Prof. Carlo Caduf, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2022 Nov 28; Accepted 2022 Nov 29; Issue date 2023 Jan-Mar.

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Qualitative research methods are widely used in the social sciences and the humanities, but they can also complement quantitative approaches used in clinical research. In this article, we discuss the key features and contributions of qualitative research methods.

Keywords: Qualitative research, social sciences, sociology

INTRODUCTION

Qualitative research methods refer to techniques of investigation that rely on nonstatistical and nonnumerical methods of data collection, analysis, and evidence production. Qualitative research techniques provide a lens for learning about nonquantifiable phenomena such as people's experiences, languages, histories, and cultures. In this article, we describe the strengths and role of qualitative research methods and how these can be employed in clinical research.

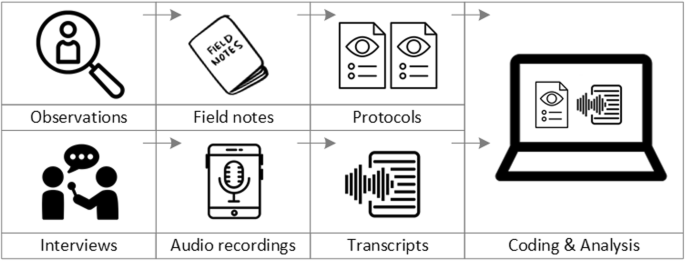

Although frequently employed in the social sciences and humanities, qualitative research methods can complement clinical research. These techniques can contribute to a better understanding of the social, cultural, political, and economic dimensions of health and illness. Social scientists and scholars in the humanities rely on a wide range of methods, including interviews, surveys, participant observation, focus groups, oral history, and archival research to examine both structural conditions and lived experience [ Figure 1 ]. Such research can not only provide robust and reliable data but can also humanize and add richness to our understanding of the ways in which people in different parts of the world perceive and experience illness and how they interact with medical institutions, systems, and therapeutics.

Examples of qualitative research techniques

Qualitative research methods should not be seen as tools that can be applied independently of theory. It is important for these tools to be based on more than just method. In their research, social scientists and scholars in the humanities emphasize social theory. Departing from a reductionist psychological model of individual behavior that often blames people for their illness, social theory focuses on relations – disease happens not simply in people but between people. This type of theoretically informed and empirically grounded research thus examines not just patients but interactions between a wide range of actors (e.g., patients, family members, friends, neighbors, local politicians, medical practitioners at all levels, and from many systems of medicine, researchers, policymakers) to give voice to the lived experiences, motivations, and constraints of all those who are touched by disease.

PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

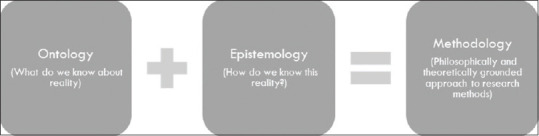

In identifying the factors that contribute to the occurrence and persistence of a phenomenon, it is paramount that we begin by asking the question: what do we know about this reality? How have we come to know this reality? These two processes, which we can refer to as the “what” question and the “how” question, are the two that all scientists (natural and social) grapple with in their research. We refer to these as the ontological and epistemological questions a research study must address. Together, they help us create a suitable methodology for any research study[ 1 ] [ Figure 2 ]. Therefore, as with quantitative methods, there must be a justifiable and logical method for understanding the world even for qualitative methods. By engaging with these two dimensions, the ontological and the epistemological, we open a path for learning that moves away from commonsensical understandings of the world, and the perpetuation of stereotypes and toward robust scientific knowledge production.

Developing a research methodology

Every discipline has a distinct research philosophy and way of viewing the world and conducting research. Philosophers and historians of science have extensively studied how these divisions and specializations have emerged over centuries.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] The most important distinction between quantitative and qualitative research techniques lies in the nature of the data they study and analyze. While the former focus on statistical, numerical, and quantitative aspects of phenomena and employ the same in data collection and analysis, qualitative techniques focus on humanistic, descriptive, and qualitative aspects of phenomena.[ 4 ]

For the findings of any research study to be reliable, they must employ the appropriate research techniques that are uniquely tailored to the phenomena under investigation. To do so, researchers must choose techniques based on their specific research questions and understand the strengths and limitations of the different tools available to them. Since clinical work lies at the intersection of both natural and social phenomena, it means that it must study both: biological and physiological phenomena (natural, quantitative, and objective phenomena) and behavioral and cultural phenomena (social, qualitative, and subjective phenomena). Therefore, clinical researchers can gain from both sets of techniques in their efforts to produce medical knowledge and bring forth scientifically informed change.

KEY FEATURES AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

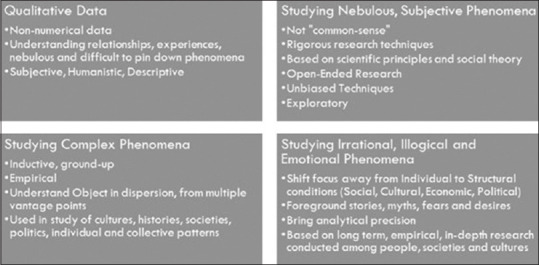

In this section, we discuss the key features and contributions of qualitative research methods [ Figure 3 ]. We describe the specific strengths and limitations of these techniques and discuss how they can be deployed in scientific investigations.

Key features of qualitative research methods

One of the most important contributions of qualitative research methods is that they provide rigorous, theoretically sound, and rational techniques for the analysis of subjective, nebulous, and difficult-to-pin-down phenomena. We are aware, for example, of the role that social factors play in health care but find it hard to qualify and quantify these in our research studies. Often, we find researchers basing their arguments on “common sense,” developing research studies based on assumptions about the people that are studied. Such commonsensical assumptions are perhaps among the greatest impediments to knowledge production. For example, in trying to understand stigma, surveys often make assumptions about its reasons and frequently associate it with vague and general common sense notions of “fear” and “lack of information.” While these may be at work, to make such assumptions based on commonsensical understandings, and without conducting research inhibit us from exploring the multiple social factors that are at work under the guise of stigma.

In unpacking commonsensical understandings and researching experiences, relationships, and other phenomena, qualitative researchers are assisted by their methodological commitment to open-ended research. By open-ended research, we mean that these techniques take on an unbiased and exploratory approach in which learnings from the field and from research participants, are recorded and analyzed to learn about the world.[ 5 ] This orientation is made possible by qualitative research techniques that are particularly effective in learning about specific social, cultural, economic, and political milieus.

Second, qualitative research methods equip us in studying complex phenomena. Qualitative research methods provide scientific tools for exploring and identifying the numerous contributing factors to an occurrence. Rather than establishing one or the other factor as more important, qualitative methods are open-ended, inductive (ground-up), and empirical. They allow us to understand the object of our analysis from multiple vantage points and in its dispersion and caution against predetermined notions of the object of inquiry. They encourage researchers instead to discover a reality that is not yet given, fixed, and predetermined by the methods that are used and the hypotheses that underlie the study.

Once the multiple factors at work in a phenomenon have been identified, we can employ quantitative techniques and embark on processes of measurement, establish patterns and regularities, and analyze the causal and correlated factors at work through statistical techniques. For example, a doctor may observe that there is a high patient drop-out in treatment. Before carrying out a study which relies on quantitative techniques, qualitative research methods such as conversation analysis, interviews, surveys, or even focus group discussions may prove more effective in learning about all the factors that are contributing to patient default. After identifying the multiple, intersecting factors, quantitative techniques can be deployed to measure each of these factors through techniques such as correlational or regression analyses. Here, the use of quantitative techniques without identifying the diverse factors influencing patient decisions would be premature. Qualitative techniques thus have a key role to play in investigations of complex realities and in conducting rich exploratory studies while embracing rigorous and philosophically grounded methodologies.

Third, apart from subjective, nebulous, and complex phenomena, qualitative research techniques are also effective in making sense of irrational, illogical, and emotional phenomena. These play an important role in understanding logics at work among patients, their families, and societies. Qualitative research techniques are aided by their ability to shift focus away from the individual as a unit of analysis to the larger social, cultural, political, economic, and structural forces at work in health. As health-care practitioners and researchers focused on biological, physiological, disease and therapeutic processes, sociocultural, political, and economic conditions are often peripheral or ignored in day-to-day clinical work. However, it is within these latter processes that both health-care practices and patient lives are entrenched. Qualitative researchers are particularly adept at identifying the structural conditions such as the social, cultural, political, local, and economic conditions which contribute to health care and experiences of disease and illness.

For example, the decision to delay treatment by a patient may be understood as an irrational choice impacting his/her chances of survival, but the same may be a result of the patient treating their child's education as a financial priority over his/her own health. While this appears as an “emotional” choice, qualitative researchers try to understand the social and cultural factors that structure, inform, and justify such choices. Rather than assuming that it is an irrational choice, qualitative researchers try to understand the norms and logical grounds on which the patient is making this decision. By foregrounding such logics, stories, fears, and desires, qualitative research expands our analytic precision in learning about complex social worlds, recognizing reasons for medical successes and failures, and interrogating our assumptions about human behavior. These in turn can prove useful in arriving at conclusive, actionable findings which can inform institutional and public health policies and have a very important role to play in any change and transformation we may wish to bring to the societies in which we work.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- 1. Shapin S, Schaffer S. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1985. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Uberoi JP. Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1978. Science and Culture. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Poovey M. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1998. A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Creswell JW. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Bhangu S, Bisshop A, Engelmann S, Meulemans G, Reinert H, Thibault-Picazo Y. Feeling/Following: Creative Experiments and Material Play, Anthropocene Curriculum, Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Max Planck Institute for the History of Science; The Anthropocene Issue. 2016 [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (583.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

What is Qualitative in Research

- Review Essay

- Open access

- Published: 28 October 2021

- Volume 44 , pages 599–608, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Patrik Aspers 1 &

- Ugo Corte 2

41k Accesses

7 Citations

Explore all metrics

In this text we respond and elaborate on the four comments addressing our original article. In that piece we define qualitative research as an “iterative process in which improved understanding to the scientific community is achieved by making new significant distinctions resulting from getting closer to the phenomenon studied.” In light of the comments, we identify three positions in relation to our contribution: (1) to not define qualitative research; (2) to work with one definition for each study or approach of “qualitative research” which is predominantly left implicit; (3) to systematically define qualitative research. This article elaborates on these positions and argues that a definition is a point of departure for researchers, including those reflecting on, or researching, the fields of qualitative and quantitative research. The proposed definition can be used both as a standard of evaluation as well as a catalyst for discussions on how to evaluate and innovate different styles of work.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

What is “qualitative” in qualitative research why the answer does not matter but the question is important, unsettling definitions of qualitative research.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The editors of Qualitative Sociology have given us the opportunity not only to receive comments by a group of particularly qualified scholars who engage with our text in a constructive fashion, but also to reply, and thereby to clarify our position. We have read the four essays that comment on our article What is qualitative in qualitative research (Aspers and Corte 2019 ) with great interest. Japonica Brown-Saracino, Paul Lichterman, Jennifer Reich, and Mario Luis Small agree that what we do is new. We are grateful for the engagement that the four commenters show with our text.

Our article is based on a standard approach: we pose a question drawing on our personal experiences and knowledge of the field, make systematic selections from existing literature, identify, collect and analyze data, read key texts closely, make interpretations, move between theory and evidence to connect them, and ultimately present a definition: “ qualitative research as an iterative process in which improved understanding to the scientific community is achieved by making new significant distinctions resulting from getting closer to the phenomenon studied” (Aspers and Corte 2019 , 139) . We acknowledge that there are different qualitative characteristics of research, meaning that we do not merely operate with a binary code of qualitative versus non-qualitative research. Our definition is an attempt to make a new distinction that clarifies what is qualitative in qualitative research and which is useful to the scientific community. Consequently, our work is in line with the definition that we have proposed.

Given the interest that our contribution has already generated, it is reasonable to argue that the new distinction we put forth is also significant . As researchers we make claims about significance, but it is always the audience—other scientists—who decide whether the contribution is significant or not. Iteration means that one goes back and forth between theory and evidence, and improved understanding refers to the epistemic gains of a study. To achieve this improved understanding by pursuing qualitative research, it is necessary that one gets close to the empirical material. When these four components are combined, we speak of qualitative research.

The four commentators welcome our text, which does not imply that they agree with all of the arguments we advance. In what follows, we single out some of the most important critiques we received and provide a reply aiming to push the conversation about qualitative research forward.

Why a Definition?

We appreciate that all critics have engaged closely with our definition. One main point of convergence between them is that one should not try to define qualitative research. Small ( Forthcoming ) asks rhetorically: “Is producing a single definition a good idea?” He justifies his concern by pointing out that the term is used to describe both different practices (different kinds of studies) and three elements (types of data; data collection, and analysis). Similarly, both Brown-Saracino ( Forthcoming ) and Lichterman, ( Forthcoming ) argue that not only there is no single entity called qualitative research—a view that we share, but instead, that definitions change over time. For Small, producing a single definition for a field as diverse as sociology, or the social sciences for that matter, is restrictive, a point which is also, albeit differently, shared by Brown-Saracino. Brown-Saracino asserts that our endeavor “might calcify boundaries, stifle innovation, and prevent recognition of areas of common ground across areas that many of us have long assumed to be disparate.” Hence, one should not define what is qualitative, because definitions may harm development. Both Small and Brown-Saracino say that we are drawing boundaries between qualitative and quantitative approaches and overstate differences between them. Yet, part of our intent was the opposite: to build bridges between different approaches by arguing that the ‘qualitative’ feature of research pertains both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, which may use and even combine different methods.

In light of these comments we need to elaborate our argument. Moreover, it is important not to maintain hard lines that may lead to scientific tribalism. Nonetheless, the critique of our—or any other definition of qualitative research—typically implies that there is something “there,” but that we have not captured it correctly with our definition. Thus, the critique that we should not define qualitative research comes with an implicit contradiction. If all agree that there is something called “qualitative research,” even if it is only something that is not quantitative, this still presumes that there is something called “qualitative.” Had we done research on any other topic it would probably have been requested by reviewers to define what we are talking about. The same criteria should apply also when we turn the researcher’s gaze on to our own practice.

Moreover, it is doubtful that our commentators would claim that qualitative research can be “anything,” as the more Dadaistic interpretation by Paul Feyerabend ( 1976 ) would have it. But without referring to the realist view of Karl Popper ( 1963 , 232–3) and his ideas of verisimilitude (i.e., that we get close to the truth) we have tried to spell out what we see as an account of the phenomenology of “qualitative.” We identify three positions in relation to the issue of definition of qualitative research:

We should not define qualitative research.

We can work with one definition for each study or approach of “qualitative research,” which is predominantly left implicit.

We can try to systematically define qualitative research.

Obviously, we have embraced and practiced position 3 in reaction to the current state of the field which is largely dominated by position 2--namely that what is qualitative research is open to a large variety of “definitions.” The critical points of our commentators explicitly or implicitly argue in favor of position 1, or perhaps position 2. Our claim that a definition can help researchers sort good from less good research has triggered criticism. Below, we elaborate on this issue.

We maintain that a definition is a valid starting point useful for junior scholars to learn more about what is qualitative and what is quantitative, and for more advanced researchers it may feature as a point of departure to make improvements, for instance, in clarifying their epistemological positions and goals. But we could have done a better job in clarifying our position. Nonetheless, we contend that change and improvement at this late stage of development in social sciences is partially related to and dependent upon pushing against or building upon clear benchmarks, such as the definition that we have formulated. We acknowledge that “definitions might evolve or diversify over time,” as Brown-Saracino suggests. Still, surely social scientists can keep two things in mind at the same time: an existing definition may be useful, but new research may change it. This becomes evident if one applies our definition to the definition itself: our definition is not immune to work that leads to new qualitative distinctions! Having said this, we are happy to see that all four comments profit from getting in close contact with the definition. This means that our definition and the article offer the reader an opportunity to think with (Fine and Corte 2022 ) or, as Small writes, “forces the reader to think.” We believe that both in principle and in practice, we all agree that clarity and definitions are scientific virtues.

What can a Definition Enable?

While we agree with several points in Small’s essay, we disagree on others. Our underlying assumption is that we can build on existing knowledge, albeit not in the way positivism envisioned it. It follows that work which is primarily descriptive, evocative, political, or generally aimed at social change may entail new knowledge, but it does not fit well within the frame within which we operate in this piece. The existence of different kinds of work, each of which relies on different standards of evaluation—which are often unclear and consequential, especially to graduate students and junior scholars (see Corte and Irwin 2017 )—brings us to another point highlighted by both Small and Lichterman: can the definition be used to differentiate good from lesser good kinds of work?

Small argues that while our article promises to develop a standard of evaluation, it fails to do so. We agree: our definition does not specify the exact criteria of what is good and what is poor research. Our definition demarcates qualitative research from non-qualitative by spelling out the qualitative elements of research, which advances a criterion of evaluation. In addition, there is definitely research that meets the characteristics of being qualitative, but that is uninteresting, irrelevant, or essentially useless (see Alvesson et al. 2017 on “gap spotting,” for instance). What is good or not good research is to be decided in an ongoing scientific discussion led by those who actively contribute to the development of a field. A definition, nonetheless, can serve as a point of reference to evaluate scholarly work, and it can also serve as a guideline to demarcate what is qualitative from what it is not.

A Good Definition?

Even if one accepts that there should be a definition of qualitative research, and thinks that such a definition could be useful, it does not follow that one must accept our definition. Small identifies what he sees a paradox in our text, namely that we both speak of qualitative research in general and of qualitative elements in different research activities. The term qualitative, as we note and as Small specifies, is used to describe different things: from small n studies to studies of organizations, states, or other units conceptualized as case studies and analyzed quantitatively as well as qualitatively. We are grateful for this observation, which is correct. We failed to properly address this issue in the original text.

As we discuss in the article, the elements used in our definitions (distinctions, process, closeness, and improved understanding) are present in all kinds of research, even quantitative. Perhaps the title of our article should have been: “What is Qualitative in Research?” Our position is that only when all the elements of the definition are applied can one speak of qualitative research. Hence, the first order constructs (i.e., the constructs the actors in the field have made) (Aspers 2009 ) of, for example, “qualitative observations,” may indeed refer to observations that make qualitative distinction in the Aristotelian sense on which we rely. Still, if these qualitative observations are commensurated with a ratio-scale (i.e., get reduced to numbers) this research can no longer be called “qualitative.” It is for this reason that we say that, to refer to first order constructs, “quantitative” research processes entail “qualitative” elements. This research is, as it were, partially qualitative, but it is not, taken together, qualitative research. Brown-Saracino raises a similar point in relation to her own and others works that combine “qualitative” and “quantitative” research. We do not think that one is inherently better, yet we agree with the general idea that qualitative research is particularly useful in identifying research questions and formulating theories (distinctions) that, at a later point should, when possible, be tested quantitatively on larger samples (cf. Small 2005 ). It is our hope that, with our clarification above, it will be easier for researchers to understand what one is and what one is not doing. We also hope that our study will stimulate further dialogue and collaboration between researchers who primarily work within different traditions.

Small wonders if a researcher who tries to replicate a “qualitative” study (according to our definition) is doing qualitative research. The person is certainly doing research, and some elements are likely conducted in a qualitative fashion according to our definition, for example if the method of in-depth fieldwork is employed. But regardless of the method used, and regardless of whether the person finds new things, if the result is binary coded as either confirming or disconfirming existing research, qualitative research is not being conducted because no new distinction is offered. Imagine the same study being replicated for the 20 th time. Surely the researcher must use the same “qualitative” methods (to use the first order construct). It may even excite a large academic audience, but it would not count as qualitative research according to our definition. Our definition requires both that the research process has made use of all its elements, but it also requires the acceptance by the audience. Having said this, in practice, it is more likely that such a study would also report new distinctions that are acknowledged by an audience. If such a study is reviewed and published, these are additional indicators that the new distinctions are considered significant, at least to some extent: how much research space it opens up, and how much it helps other researchers continue the discussion by formulating their own questions and making their own claims (Collins 1998 , 31), whether by agreeing with it by applying it, by refining it (Snow et al. 2003 ), or by disagreeing and identifying new ways forward. There are two key characteristics that make a contribution relevant: newness and usefulness (Csikszentmihalyi 1996 ), both of which are related to the established state of knowledge within a field. Relatedly, Small asks: “Is newness enough? What does a new distinction that does not improve understanding look like?” There are also other indicators that demarcate whether a contribution is significant and to what extent. Some of these indicators include the number of citations a piece of work generates, the reputation of the journal or press where the work is published, and how widely the contribution is used—for instance, across specializations within the same discipline, or across different fields (i.e., different ways of valuation and evaluation) (Aspers and Beckert 2011 ) of scientific output. In principle, if a contribution ends up being used in an area where it would have unlikely been used, then one may further argue for its significance.

As it is implicit in our work when we talk about distinctions, we refer to theory building, albeit appreciating different conceptualizations and uses of the term theory (Abend 2008 ) and ways to achieve it (e.g., Zerubavel 2020 ). Brown-Saracino writes that our project may hold “the unintended consequence of limiting exploratory research designs and methodological innovations.” While we cannot predict the impact of our research, we are certainly in favor of experimentation and different styles of work. In line with David Snow, Calvin Morrill and Leon Anderson ( 2003 , 184), we argue that many qualitative researchers start their projects being underprepared in theory and theory development, oftentimes with the goal of describing, and leaving alone the black box of theory, or postponing it to later phases of the project. Our definition, along with the work by those authors and others on theory development, can be one way to heighten the chances researchers can make distinctions and develop theory.

Lichterman argues that we are not giving enough weight to interpretation and that we should relate more strongly to the larger project of the Geistenwissenschaften . We agree that interpretation is a key element in qualitative research, and we draw on Hans-Georg Gadamer ( 1988 ) who refined the idea of the hermeneutic circle.

Another critique, raised by Reich ( Forthcoming ), is that positionality is a key element of qualitative research. That in working towards a definition, we have “overlooked much of the methodological writings and contributions of women, scholars of color, and queer scholars” that could have enriched our definition, especially regarding “getting closer to the phenomenon studied.” Surely, the way we have searched for and included references means that we have ‘excluded’ the vast majority of research and researchers who do qualitative work. However, we have not included texts by some authors in our sample based on any specific characteristics or according to any specific position. This critique is valid only if Reich shows more explicitly what this inclusion would add to our definition.

Though we agree with much of what Reich says, for example about the role of bodies and reflexivity in ethnographic work, the idea of positionality as a normative notion is problematic. At least since Gadamer wrote in the early 1960s (1988), it is clear that there are no interpretations ‘from nowhere.’ Who one is cannot be bracketed in an interpretation of what has occurred. The scientific value of this more identity- and positionality-oriented research that accounts also of the positionality of the interpreter, is essentially already well acknowledged. Reflection is not just something that qualitative researcher do; it is a general aspect of research. Ethnographic researchers may need certain skills to get close and understand the phenomenon they study, yet they also need to maintain distance. As Fine and Hallett write: “The ethnographic stranger is uniquely positioned to be a broker in connecting the field with the academy, bringing the site into theory and, perhaps, permitting the academy to consider joint action with previously distant actors” (Fine and Hallett 2014 , 195). Moreover, Brown-Saracino illustrates well what it means to get close, and we too see that ethnography, in various forms and ways, is useful as other qualitative activities. Though ethnographic research cannot be quantitative, qualitative work is broader than solely ethnographic research. Furthermore, reflexivity is not something that one has to do when doing qualitative research, but something one does as a researcher.

Reich’s second point is more important. The claim is that if the standpoint-oriented argument is completely accepted, it will most likely violate what we see as the essence of research. We warned in our article that qualitative research may be treated as less scientific than quantitative within academia, but also in the general public, if too many in academia claim to be doing “qualitative research” while they are in fact telling stories, engaging in activism, or writing like journalists. Such approaches are extra problematic if only some people with certain characteristics are viewed as the only legitimate producers of certain types of knowledge. If these tendencies are fueled, it is not merely the definition of “qualitative” that is at stake, but what the great majority see as research in general. Science cannot reach “The Truth,” but if one gives up the idea communal and universal nature of scientific knowledge production and even a pragmatic notion of truth, much of its value and rationale of science as an independent sphere in society is lost (Merton 1973 ; Weber 1985 ). Ralf Dahrendorf framed this form of publicness by writing that: “Science is always a concert, a contrapuntal chorus of the many who are engaged in it. Insofar as truth exists at all, it exists not as a possession of the individual scholar, but as the net result of scientific interchange” (1968, 242–3). The issue of knowledge is a serious matter, but it is also another debate which relates to social sciences being low consensus fields (Collins 1994 ; Fuchs 1992 ; Parker and Corte 2017 , 276) in which the proliferation of journals and lack of agreement about common definitions, research methods, and interpretations of data contributes to knowledge fragmentation. To abandon the idea of community may also cause confusion, and piecemeal contributions while affording academics a means to communicate with a restricted in-group who speak their own small language and share their views among others of the same tribe, but without neither the risk nor possibility of gaining general public recognition. In contrast, we see knowledge as something public, that, ideal-typically, “can be seen and heard by everybody” (Arendt 1988 , 50), reflecting a pragmatic consensual approach to knowledge, but with this argument we are way beyond the theme of our article.

Our concern with qualitative research was triggered by the external critique of what is qualitative research and current debates in social science. Our definition, which deliberately tries to avoid making the use of a specific method or technique the essence of qualitative, can be used as a point of reference. In all the replies by Brown-Saracino, Lichterman, Reich, and Small, several examples of practices that are in line with our definition are given. Thus, the definition can be used to understand the practice of research, but it would also allow researchers to deliberately deviate from it and develop it. We are happy to see that all commentators have used our definition to move further, and in this pragmatic way the definition has already proved its value.

New research should be devoted to delineating standards and measures of evaluation for different kinds of work such as the those we have identified above: theoretical, descriptive, evocative, political, or aimed at social change (see Brady and Collier 2004; Ragin et al. 2004 ; Van Maanen 2011 ). And those standards could respectively be based upon scientific or stylistic advancement and social and societal impact. Footnote 1 Different work should be evaluated in relation to their respective canons, goals, and audiences, and there is certainly much to gain from learning from other perspectives. Relatedly, being fully aware of the research logics of both qualitative and quantitative traditions (Small 2005 ) is also an advantage for improving both of them and to spur further collaboration. Bringing further clarity on these points will ultimately improve different traditions, foster creativity potentially leading to innovative projects, and be useful both to younger researchers and established scholars.

The last two terms refer to whether the impacts are more micro as related to agency, or macro, as related to structural changes. An example of the latter kind is Matthew Desmond’s Eviction (2016) having substantial societal impact on public policy discussions, raising and researching a broader range of housing issues in the US. A case of the former is Arlie Hochchild’s studies on emotional labor of women in the workplace (1983) and her more recent book on the alienation of white, working-class Americans (2016).

Abend, Gabriel. 2008. The meaning of “theory” . Sociological Theory 26 (2): 173–199.

Article Google Scholar

Alvesson, Mats, Yannis Gabriel, and Roland Paulsen. 2017. Return to meaning . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Arendt, Hannah. 1988. The human condition . Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Google Scholar

Aspers, Patrik. 2009. Empirical phenomenology: A qualitative research approach (the Cologne Seminars). Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 9 (2): 1–12.

Aspers, Patrik, and Ugo Corte. 2019. What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology 42 (2): 139–160.

Aspers, Patrik, and Jens Beckert. 2011. Introduction. In The worth of goods , eds. Jens Beckert and Patrik Aspers, 3–38. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brady, Henry E., and David Collier, eds. 2004. Rethinking social inquiry: Diverse tools, shared standards . Berkeley: Rowman & Littlefield and Berkeley Public Policy Press.

Brown-Saracino, Japonica. Forthcoming. Unsettling definitions of qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology.

Collins, Randall. 1994. Why the social sciences won’t become high-consensus, rapid-discovery science. Sociological Forum 9 (2): 155–177.

Collins, Randall. 1998. The sociology of philosophies: A global theory of intellectual change . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Corte, Ugo, and Katherine Irwin. 2017. The form and flow of teaching ethnographic knowledge: Hands-on approaches for learning epistemology. Teaching Sociology 45 (3): 209–219.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1996. Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and iinvention . New York: Harper/Collins.

Dahrendorf, Ralf. 1968. Essays in the theory of society . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Desmond, Matthew. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American City . New York: Crown Publishers.

Feyerabend, Paul. 1976. Against method . London: NLB.

Fine, Gary Alan and Ugo Corte. 2022. Dark fun: The cruelties of hedonic communities. Sociological Forum 37 (1).

Fine, Gary Alan, and Tim Hallett. 2014. Stranger and stranger: Creating theory through thnographic Distance and Authority. Journal of Organizational Ethnography 3 (2): 188–203.

Fuchs, Stephan. 1992. The professional quest for truth . New York: SUNY Press.

Gadamer, Hans Georg. 1988. On the circle of understanding. In Hermenutics versus science, three German views: Wolfgang Stegmüller, Hans Georg Gadamer, Ernst Konrad Specht , eds. John Connolly and Thomas Keutner, 68–78. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame.

Hochschild, Arlie. 1983. The managed heart: Comercialization of human feeling . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hochschild, Arlie. 2016. Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American right . New York: The New Press.

Lichterman, Paul. Forthcoming. “Qualitative research” is a moving target. Qualitative Sociology.

Merton, Robert K. 1973. Structure of science. In The sociology of science: Theoretical and empirical investigations , ed. Robert K. Merton, 267–278. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Parker, John N., and Ugo Corte. 2017. Placing collaborative circles in strategic action fields: Explaining differences between highly creative groups. Sociological Theory 35 (4): 261–287.

Popper, Karl. 1963. Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge . London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Ragin, Charles, Joane Nagel, and Patricia White. 2004. Workshop on scientific foundations of qualitative research. National Research Foundation. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2004/nsf04219/nsf04219.pdf . Acessed 29 September 2021.

Reich, Jennifer. Forthcoming. Power, positionality, and the ethic of care in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology.

Small, Mario Luis 2005. Lost in translation: How not to make qualitative research more scientific. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.497.4161&rep=rep1&type=pdf . Accessed 23 September 2021.

Small, Mario Luis. Forthcoming. What is “qualitative” in qualitative research? Why the answer does not matter but the question is important. Qualitative Sociology.

Snow, David A., Calvin Morrill, and Leon Anderson. 2003. Elaborating analytic ethnography: Linking fieldwork and theory. Ethnography 4 (2): 181–200.

Van Maanen, John. 2011. Tales of the field: On writing ethnography . Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Weber, Max. 1985. Gesammelte aufsätze zur wissenschaftslehre. Edited by J. Winckelmann. Tübingen: J.C.B.Mohr.

Zerubavel, Eviatar. 2020. Generally speaking: An invitation to concept-driven sociology . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for comments by Gary Alan Fine, Jukka Gronow, and John Parker.

Open access funding provided by University of St. Gallen. The research reported here is funded by University of St. Gallen, Switzerland and University of Stavanger, Norway.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of St., Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Patrik Aspers

University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Patrik Aspers .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Aspers, P., Corte, U. What is Qualitative in Research. Qual Sociol 44 , 599–608 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-021-09497-w

Download citation

Accepted : 12 October 2021

Published : 28 October 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-021-09497-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Epistemology

- Standards of valuation

- Research styles

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

803k Accesses

391 Citations

90 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

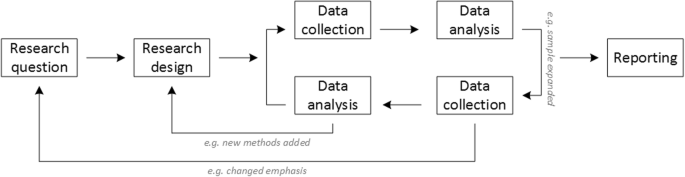

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

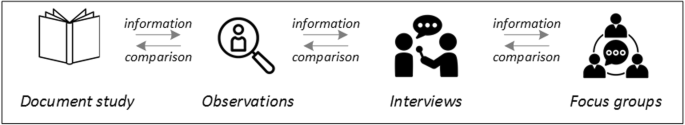

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

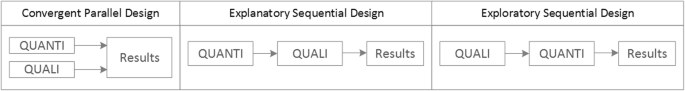

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research