Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a research proposal

What is a research proposal?

What is the purpose of a research proposal , how long should a research proposal be, what should be included in a research proposal, 1. the title page, 2. introduction, 3. literature review, 4. research design, 5. implications, 6. reference list, frequently asked questions about writing a research proposal, related articles.

If you’re in higher education, the term “research proposal” is something you’re likely to be familiar with. But what is it, exactly? You’ll normally come across the need to prepare a research proposal when you’re looking to secure Ph.D. funding.

When you’re trying to find someone to fund your Ph.D. research, a research proposal is essentially your “pitch.”

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research.

You’ll need to set out the issues that are central to the topic area and how you intend to address them with your research. To do this, you’ll need to give the following:

- an outline of the general area of study within which your research falls

- an overview of how much is currently known about the topic

- a literature review that covers the recent scholarly debate or conversation around the topic

➡️ What is a literature review? Learn more in our guide.

Essentially, you are trying to persuade your institution that you and your project are worth investing their time and money into.

It is the opportunity for you to demonstrate that you have the aptitude for this level of research by showing that you can articulate complex ideas:

It also helps you to find the right supervisor to oversee your research. When you’re writing your research proposal, you should always have this in the back of your mind.

This is the document that potential supervisors will use in determining the legitimacy of your research and, consequently, whether they will invest in you or not. It is therefore incredibly important that you spend some time on getting it right.

Tip: While there may not always be length requirements for research proposals, you should strive to cover everything you need to in a concise way.

If your research proposal is for a bachelor’s or master’s degree, it may only be a few pages long. For a Ph.D., a proposal could be a pretty long document that spans a few dozen pages.

➡️ Research proposals are similar to grant proposals. Learn how to write a grant proposal in our guide.

When you’re writing your proposal, keep in mind its purpose and why you’re writing it. It, therefore, needs to clearly explain the relevance of your research and its context with other discussions on the topic. You need to then explain what approach you will take and why it is feasible.

Generally, your structure should look something like this:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Research Design

- Implications

If you follow this structure, you’ll have a comprehensive and coherent proposal that looks and feels professional, without missing out on anything important. We’ll take a deep dive into each of these areas one by one next.

The title page might vary slightly per your area of study but, as a general point, your title page should contain the following:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- The name of your institution and your particular department

Tip: Keep in mind any departmental or institutional guidelines for a research proposal title page. Also, your supervisor may ask for specific details to be added to the page.

The introduction is crucial to your research proposal as it is your first opportunity to hook the reader in. A good introduction section will introduce your project and its relevance to the field of study.

You’ll want to use this space to demonstrate that you have carefully thought about how to present your project as interesting, original, and important research. A good place to start is by introducing the context of your research problem.

Think about answering these questions:

- What is it you want to research and why?

- How does this research relate to the respective field?

- How much is already known about this area?

- Who might find this research interesting?

- What are the key questions you aim to answer with your research?

- What will the findings of this project add to the topic area?

Your introduction aims to set yourself off on a great footing and illustrate to the reader that you are an expert in your field and that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge and theory.

The literature review section answers the question who else is talking about your proposed research topic.

You want to demonstrate that your research will contribute to conversations around the topic and that it will sit happily amongst experts in the field.

➡️ Read more about how to write a literature review .

There are lots of ways you can find relevant information for your literature review, including:

- Research relevant academic sources such as books and journals to find similar conversations around the topic.

- Read through abstracts and bibliographies of your academic sources to look for relevance and further additional resources without delving too deep into articles that are possibly not relevant to you.

- Watch out for heavily-cited works . This should help you to identify authoritative work that you need to read and document.

- Look for any research gaps , trends and patterns, common themes, debates, and contradictions.

- Consider any seminal studies on the topic area as it is likely anticipated that you will address these in your research proposal.

This is where you get down to the real meat of your research proposal. It should be a discussion about the overall approach you plan on taking, and the practical steps you’ll follow in answering the research questions you’ve posed.

So what should you discuss here? Some of the key things you will need to discuss at this point are:

- What form will your research take? Is it qualitative/quantitative/mixed? Will your research be primary or secondary?

- What sources will you use? Who or what will you be studying as part of your research.

- Document your research method. How are you practically going to carry out your research? What tools will you need? What procedures will you use?

- Any practicality issues you foresee. Do you think there will be any obstacles to your anticipated timescale? What resources will you require in carrying out your research?

Your research design should also discuss the potential implications of your research. For example, are you looking to confirm an existing theory or develop a new one?

If you intend to create a basis for further research, you should describe this here.

It is important to explain fully what you want the outcome of your research to look like and what you want to achieve by it. This will help those reading your research proposal to decide if it’s something the field needs and wants, and ultimately whether they will support you with it.

When you reach the end of your research proposal, you’ll have to compile a list of references for everything you’ve cited above. Ideally, you should keep track of everything from the beginning. Otherwise, this could be a mammoth and pretty laborious task to do.

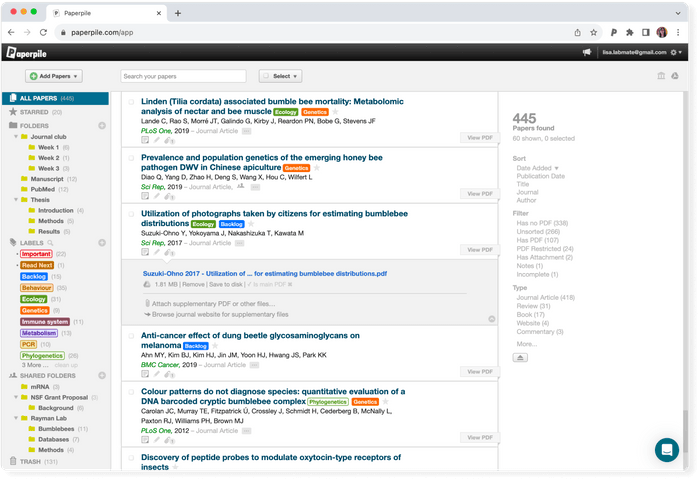

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to format and organize your citations. Paperpile allows you to organize and save your citations for later use and cite them in thousands of citation styles directly in Google Docs, Microsoft Word, or LaTeX.

Your project may also require you to have a timeline, depending on the budget you are requesting. If you need one, you should include it here and explain both the timeline and the budget you need, documenting what should be done at each stage of the research and how much of the budget this will use.

This is the final step, but not one to be missed. You should make sure that you edit and proofread your document so that you can be sure there are no mistakes.

A good idea is to have another person proofread the document for you so that you get a fresh pair of eyes on it. You can even have a professional proofreader do this for you.

This is an important document and you don’t want spelling or grammatical mistakes to get in the way of you and your reader.

➡️ Working on a research proposal for a thesis? Take a look at our guide on how to come up with a topic for your thesis .

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research. Generally, your research proposal will have a title page, introduction, literature review section, a section about research design and explaining the implications of your research, and a reference list.

A good research proposal is concise and coherent. It has a clear purpose, clearly explains the relevance of your research and its context with other discussions on the topic. A good research proposal explains what approach you will take and why it is feasible.

You need a research proposal to persuade your institution that you and your project are worth investing their time and money into. It is your opportunity to demonstrate your aptitude for this level or research by showing that you can articulate complex ideas clearly, concisely, and critically.

A research proposal is essentially your "pitch" when you're trying to find someone to fund your PhD. It is a clear and concise summary of your proposed research. It gives an outline of the general area of study within which your research falls, it elaborates how much is currently known about the topic, and it highlights any recent debate or conversation around the topic by other academics.

The general answer is: as long as it needs to be to cover everything. The length of your research proposal depends on the requirements from the institution that you are applying to. Make sure to carefully read all the instructions given, and if this specific information is not provided, you can always ask.

How to write a research proposal

Drafting your first research proposal can be intimidating if you’ve never written (or seen) one before. Our grad students and admissions staff have some advice on making a start.

Before you make a start

Is it a requirement for your course.

For some research courses in sciences you’ll join an existing research group so you don’t need to write a full research proposal, just a list of the groups and/or supervisors you want to work with. You might be asked to write a personal statement instead, giving your research interests and experience.

Still, for many of our research courses — especially in humanities and social sciences — your research proposal is one of the most significant parts of your application. Grades and other evidence of your academic ability and potential are important, but even if you’re academically outstanding you’ll need to show you’re a good match for the department’s staff expertise and research interests. Every course page on the University website has detailed information on what you’ll need to send with your application, so make sure that’s your first step before you continue:

There are many ways to start, I’ve heard stories about people approaching it totally differently. Yannis (DPhil in Computer Science)

How to begin?

There isn’t one right way to start writing a research proposal. First of all, make sure you’ve read your course page - it’ll have instructions for what to include in your research proposal (as well as anything to avoid), how your department will assess it, and the required word count.

Start small, think big

A research degree is a big undertaking, and it’s normal to feel a bit overwhelmed at first. One way to start writing is to look back at the work you’ve already done. How does your proposed research build on this, and the other research in the area? One of the most important things you’ll be showing through your research project is that your project is achievable in the time available for your course, and that you’ve got (or know how you’ll get) the right skills and experience to pull off your plan.

They don’t expect you to be the expert, you just have to have good ideas. Be willing to challenge things and do something new. Rebecca (DPhil in Medieval and Modern Languages)

However, you don’t have to know everything - after all, you haven’t started yet! When reading your proposal, your department will be looking at the potential and originality of your research, and whether you have a solid understanding of the topic you’ve chosen.

But why Oxford?

An Admissions Officer at one of our colleges says that it’s important to explain why you’re applying to Oxford, and to your department in particular:

“Really, this is all dependent on a department. Look at the department in depth, and look at what they offer — how is it in line with your interests?”

Think about what you need to successfully execute your research plans and explain how Oxford’s academic facilities and community will support your work. Should I email a potential supervisor? Got an idea? If your course page says it’s alright to contact a supervisor (check the top of the How to apply section), it’s a good idea to get in touch with potential supervisors when you come to write your proposal.

You’re allowed to reach out to academics that you might be interested in supervising you. They can tell you if your research is something that we can support here, and how, and give you ideas. Admissions Officer

You’ll find more information about the academics working in your area on your department’s website (follow the department links on your course page ). John (DPhil in Earth Sciences) emailed a professor who had the same research interests as he did.

“Luckily enough, he replied the next day and was keen to support me in the application.”

These discussions might help you to refine your ideas and your research proposal.

Layal says, “I discussed ideas with my supervisor — what’s feasible, what would be interesting. He supported me a lot with that, and I went away and wrote it.”

It’s also an opportunity to find out more about the programme and the department:

“Getting in touch with people who are here is a really good way to ask questions.”

Not sure how to find a potential supervisor for your research? Visit our How-to guide on finding a supervisor .

Asking for help

My supervisors helped me with my research proposal, which is great. You don’t expect that, but they were really helpful prior to my application. Nyree (DPhil in Archaeological Science)

Don’t be afraid to ask for advice and feedback as you go. For example, you could reach out to a supervisor from your current or previous degree, or to friends who are also studying and could give you some honest feedback.

More help with your application

You can find instructions for the supporting documents you’ll need to include in your application on your course page and in the Application Guide.

Applicant advice hub

This content was previously available through our Applicant advice hub . The hub contained links to articles hosted on our Graduate Study at Oxford Medium channel . We've moved the articles that support the application process into this new section of our website.

- Application Guide: Research proposal

Can't find what you're looking for?

If you have a query about graduate admissions at Oxford, we're here to help:

Ask a question

Privacy Policy

Postgraduate Applicant Privacy Policy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Steps in Developing a Research Proposal

Learning objectives.

- Identify the steps in developing a research proposal.

- Choose a topic and formulate a research question and working thesis.

- Develop a research proposal.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions, a working thesis, and a written research proposal. Set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Choosing a Topic

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. (For more information about purpose and audience, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .) Choosing a topic that interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask that you develop a topic on your own. In either case, try to identify topics that genuinely interest you.

After identifying potential topic ideas, you will need to evaluate your ideas and choose one topic to pursue. Will you be able to find enough information about the topic? Can you develop a paper about this topic that presents and supports your original ideas? Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify it so it is more manageable? You will ask these questions during this preliminary phase of the research process.

Identifying Potential Topics

Sometimes, your instructor may provide a list of suggested topics. If so, you may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. It is important to know how to narrow down your ideas into a concise, manageable thesis. You may also use the list as a starting point to help you identify additional, related topics. Discussing your ideas with your instructor will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment.

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying health care administration, as he prepares a research paper. You will also plan, research, and draft your own research paper.

Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on health and the media for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed a list of possibilities.

If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities. Identify reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue.

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in the news

- Sexual education programs

- Hollywood and eating disorders

- Americans’ access to public health information

- Media portrayal of health care reform bill

- Depictions of drugs on television

- The effect of the Internet on mental health

- Popularized diets (such as low-carbohydrate diets)

- Fear of pandemics (bird flu, HINI, SARS)

- Electronic entertainment and obesity

- Advertisements for prescription drugs

- Public education and disease prevention

Set a timer for five minutes. Use brainstorming or idea mapping to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Do you closely follow the media coverage of a particular website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

Narrowing Your Topic

Once you have a list of potential topics, you will need to choose one as the focus of your essay. You will also need to narrow your topic. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being too narrow to sustain an entire research paper.

A good research paper provides focused, in-depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. Narrowing your focus is essential to making your topic manageable. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing, conduct preliminary research, and discuss both the topic and the research with others.

Exploring Your Topic in Writing

“How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through freewriting. (For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .) Simply taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles.

Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment. He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s ideas.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Another way writers may focus a topic is to conduct preliminary research . Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web and browsing through newspaper and magazine articles are good ways to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic on blogs and online discussion groups. Discussing your topic with others can also inspire you. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, your friends, or your instructor.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of health and the media intersected with a few of his interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects.

Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of reliable sources and take notes on your findings.

The reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later. However, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea for your paper, be sure to check out other, more reliable sources as well to make sure the idea is worth pursuing.

Review the list of topics you created in Note 11.18 “Exercise 1” and identify two or three topics you would like to explore further. For each of these topics, spend five to ten minutes writing about the topic without stopping. Then review your writing to identify possible areas of focus.

Set aside time to conduct preliminary research about your potential topics. Then choose a topic to pursue for your research paper.

Collaboration

Please share your topic list with a classmate. Select one or two topics on his or her list that you would like to learn more about and return it to him or her. Discuss why you found the topics interesting, and learn which of your topics your classmate selected and why.

A Plan for Research

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and later, what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing a research question , a working thesis, and a research proposal.

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions. See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information about 5WH questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer your main question.

Here are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his subquestions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Using the topic you selected in Note 11.24 “Exercise 2” , write your main research question and at least four to five subquestions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

Constructing a Working ThesIs

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through additional research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason—it is subject to change. As you learn more about your topic, you may change your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not be afraid to modify it based on what you learn.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete sentences such as I believe or My opinion is . However, keep in mind that academic writing generally does not use first-person pronouns. These statements are useful starting points, but formal research papers use an objective voice.

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote in Note 11.27 “Exercise 3” . Check that your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

Creating a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a brief document—no more than one typed page—that summarizes the preliminary work you have completed. Your purpose in writing it is to formalize your plan for research and present it to your instructor for feedback. In your research proposal, you will present your main research question, related subquestions, and working thesis. You will also briefly discuss the value of researching this topic and indicate how you plan to gather information.

When Jorge began drafting his research proposal, he realized that he had already created most of the pieces he needed. However, he knew he also had to explain how his research would be relevant to other future health care professionals. In addition, he wanted to form a general plan for doing the research and identifying potentially useful sources. Read Jorge’s research proposal.

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal. Both documents define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

Writing Your Own Research Proposal

Now you may write your own research proposal, if you have not done so already. Follow the guidelines provided in this lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a research proposal involves the following preliminary steps: identifying potential ideas, choosing ideas to explore further, choosing and narrowing a topic, formulating a research question, and developing a working thesis.

- A good topic for a research paper interests the writer and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- Defining and narrowing a topic helps writers conduct focused, in-depth research.

- Writers conduct preliminary research to identify possible topics and research questions and to develop a working thesis.

- A good research question interests readers, is neither too broad nor too narrow, and has no obvious answer.

- A good working thesis expresses a debatable idea or claim that can be supported with evidence from research.

- Writers create a research proposal to present their topic, main research question, subquestions, and working thesis to an instructor for approval or feedback.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Write a Research Proposal – The Beginners Guide

Seeking guidance on crafting an effective research proposal? It’s a pivotal concern within academic circles today. Don’t worry though, we’ve got a simple solution for you.

Understanding the intricacies of composing a research proposal is fundamental. Much like its initial formulation, you should take care of its structure and other elements. Before digging into tips and tricks for writing a perfect research proposal, let’s understand what a research proposal is all about.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Proposal?

A research proposal is a key part of studying and exploring a topic academically. It’s like a blueprint for your project, outlining the main ideas and how you will approach it.

At the start of your academic exploration, a research proposal can act as a kind of map, laying out the intended journey, goals, and approaches you’ll use in your study. It’s a way of showing everyone involved a big-picture view of your project, including the scope, objectives, and methods you plan to use.

Getting a research proposal right is key to starting an academic inquiry. It’s a tricky process, so seeking paper writing help from professionals is worth considering as well. Anyways, let’s understand the importance of this academic activity which will serve as the first step for learning how to write a research proposal like a pro.

Importance of Writing a Research Proposal for Students

- To articulate and solidify research intentions.

- For skill development in research design and writing.

- As a precursor to future extensive research projects.

- To showcase academic competence and planning ability.

- To gain insights into different research methodologies.

- For feedback and refinement of research ideas.

- To cultivate effective time management skills.

- Identifying and managing required resources.

- For enhancing critical analysis and evaluation abilities.

- Preparing for careers valuing research skills.

How to Start Writing a Research Proposal – Quick Tips

Understand the guidelines.

Begin by thoroughly comprehending the specific guidelines provided by your institution or the target audience. Clarify expectations regarding format, length, and content.

Identify a Strong Research Question

Begin by coming up with a straightforward, to-the-point question or statement about a research topic. It must be focused, pertinent, and dealing with an unanswered question or challenge in the field.

Conduct a Comprehensive Literature Review

Take a look at what’s already been written about your topic. Check out the research that’s out there and put it together to get a better understanding of the context, figure out what hasn’t been looked at before, and make sure your study is important.

Outline Your Methodology

Lay out the ways and strategies you plan on using in your investigation. Explain why these techniques are appropriate and how they help to answer your research question.

Consider Feasibility and Resources

Analyze if you have enough resources, time, and access to the necessary data or materials to do the research you proposed. Make sure it’s doable within the limits you have.

Seek Feedback and Revise

Before you finish up, get advice from your teachers, profs, or friends. Revamp your plan based on what they tell you to make it more understandable, consistent, and better overall.

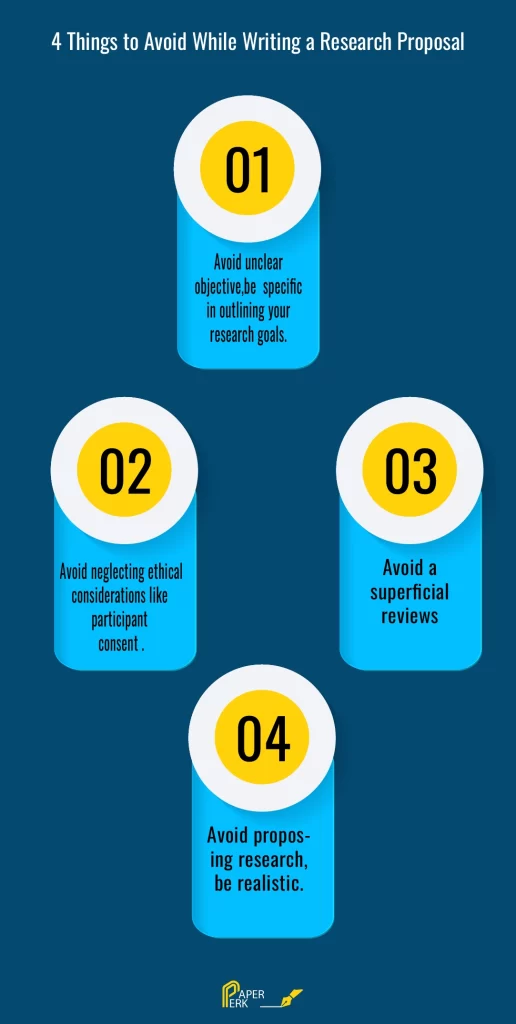

Title: 4 Things to Avoid While Writing a Research Proposal

- Avoid unclear objectives or methods; be specific in outlining your research goals.

- Avoid neglecting ethical considerations like participant consent and confidentiality.

- Avoid a superficial review; ensure a comprehensive understanding of existing research.

- Avoid proposing research beyond feasible timelines or resources; be realistic in your approach.

Steps to Write a Perfect Research Proposal

These are 11 steps from our writers for you to follow with some research proposal examples for perfecting your research proposal writing skills. These steps together can also be termed as the research proposal format.

Step 1: Title

Create a clear, concise, and descriptive title that encapsulates the essence of your proposed research.

The title of a research proposal serves as its initial point of engagement, offering a glimpse into the focus and significance of the study. Crafting a title requires precision to convey the essence of the research succinctly. Here’s a detailed breakdown with examples:

Clarity and Conciseness

The title should be clear and concise, providing a snapshot of the research’s primary focus without unnecessary wording or jargon. It should be easily comprehensible to both experts and non-experts in the field.

Original Title: “An Investigation into the Effects of Environmental Factors on Child Development in Urban Areas”

Revised Title: “Environmental Influences on Urban Child Development”

Specificity

The title should be specific enough to indicate the particular aspect or angle of the research being addressed. Vague or broad titles may fail to capture the uniqueness of the study.

Original Title: “Healthcare Challenges in Developing Countries”

Revised Title: “Access to Healthcare Services in Rural India: A Case Study”

Descriptive and Informative

The title should provide a glimpse of what the research aims to explore or uncover, giving readers an idea of the subject matter.

Original Title: “Social Media’s Impact on Society”

Revised Title: “Navigating Digital Spaces: Exploring the Social Impact of Instagram Influencers”

Keywords and Key Concepts

Incorporating relevant keywords and key concepts can enhance the discoverability of the research and its alignment with the field’s terminology.

Original Title: “Technology in Education”

Revised Title: “Integrating Virtual Reality: Enhancing STEM Education in High Schools”

Reflective of Research Scope

Ensure the title accurately reflects the scope and depth of the proposed research without overpromising or underrepresenting its objectives.

Original Title: “Solving Global Poverty”

Revised Title: “Microfinance Initiatives: Empowering Rural Communities in Sub-Saharan Africa”

Avoid Ambiguity

Steer clear of ambiguous or misleading titles that may lead to misconceptions about the research’s purpose or scope.

Original Title: “Uncovering Secrets of the Mind”

Revised Title: “Cognitive Psychology: Investigating Memory Retention in Alzheimer’s Patients”

Step 2: Introduction

The introduction of a research proposal is the foundation that sets the stage for the entire study. It aims to engage readers, provide necessary background information, and establish the rationale for the research. Here’s an in-depth explanation with examples:

Introducing the Research Problem or Question

This section should begin by highlighting the specific issue or question your research seeks to address. It serves as a hook to grab the reader’s attention and clarify the focus of your study.

In recent years, there has been a growing concern regarding the declining access to clean water in rural areas of Southeast Asia. This study aims to investigate the socio-economic factors contributing to this issue and propose sustainable solutions to improve water accessibility in these regions.

Providing Context and Background Information

Contextualizing the research problem involves discussing existing knowledge, theories, or previous studies relevant to your topic. This helps situate your research within the broader field and highlights the gaps or limitations in current understanding.

“Studies by Smith et al. (2018) and Johnson (2020) have shed light on the challenges faced by rural communities in accessing clean water. However, while these studies acknowledge the problem, a comprehensive analysis of the socio-economic factors influencing this issue remains lacking.”

Clearly Stating Objectives and Purpose

This part articulates the specific goals or aims of your research. It should clearly outline what you intend to achieve and why your study is significant in addressing the identified problem or gap.

This research endeavors to:

Identify the socio-economic barriers hindering access to clean water.

Assess the impact of community-based initiatives on water accessibility.

Propose sustainable strategies to improve water availability in rural Southeast Asian communities.

The purpose of this study is to contribute valuable insights and practical recommendations to alleviate the water scarcity crisis prevalent in these areas.

Step 3: Literature Review

The literature review section of a research proposal is a critical component that demonstrates your understanding of the existing scholarship related to your topic. Here’s a detailed breakdown with examples:

Conducting a Comprehensive Review

Begin by extensively exploring scholarly works, research papers, books, and other relevant sources that discuss your research topic. Summarize and synthesize this body of literature, organizing it in a coherent manner.