Peer Review

About this Strategy Guide

This strategy guide explains how you can employ peer review in your classroom, guiding students as they offer each other constructive feedback to improve their writing and communication skills.

Research Basis

Strategy in practice, related resources.

Peer review refers to the many ways in which students can share their creative work with peers for constructive feedback and then use this feedback to revise and improve their work. For the writing process, revision is as important as drafting, but students often feel they cannot let go of their original words. By keeping an audience in mind and participating in focused peer review interactions, students can offer productive feedback, accept constructive criticism, and master revision. This is true of other creative projects, such as class presentations, podcasts, or blogs. Online tools can also help to broaden the concept of “peers.” Real literacy happens in a community of people who can make meaningful connections. Peer review facilitates the type of social interaction and collaboration that is vital for student learning.

Peer review can be used for different class projects in a variety of ways:

- Teach students to use these three steps to give peer feedback: Compliments, Suggestions, and Corrections (see the Peer Edit with Perfection! Handout ). Explain that starting with something positive makes the other person feel encouraged. You can also use Peer Edit With Perfection Tutorial to walk through the feedback process with your students.

- Provide students with sentence starter templates, such as, “My favorite part was _________ because __________,” to guide students in offering different types of feedback. After they start with something positive, have students point out areas that could be improved in terms of content, style, voice, and clarity by using another sentence starter (“A suggestion I can offer for improvement is ___________.”). The peer editor can mark spelling and grammar errors directly on the piece of writing.

- Teach students what constructive feedback means (providing feedback about areas that need improvement without criticizing the person). Feedback should be done in an analytical, kind way. Model this for students and ask them to try it. Show examples of vague feedback (“This should be more interesting.”) and clear feedback (“A description of the main character would help me to imagine him/her better.”), and have students point out which kind of feedback is most useful. The Peer Editing Guide offers general advice on how to listen to and receive feedback, as well as how to give it.

- For younger students, explain that you need helpers, so you will show them how to be writing teachers for each other. Model peer review by reading a student’s piece aloud, then have him/her leave the room while you discuss with the rest of the class what questions you will ask to elicit more detail. Have the student return, and ask those questions. Model active listening by repeating what the student says in different words. For very young students, encourage them to share personal stories with the class through drawings before gradually writing their stories.

- Create a chart and display it in the classroom so students can see the important steps of peer editing. For example, the steps might include: 1. Read the piece, 2. Say what you like about it, 3. Ask what the main idea is, 4. Listen, 5. Say “Add that, please” when you hear a good detail. For pre-writers, “Add that, please” might mean adding a detail to a picture. Make the chart gradually longer for subsequent sessions, and invite students to add dialogue to it based on what worked for them.

- Incorporate ways in which students will review each other’s work when you plan projects. Take note of which students work well together during peer review sessions for future pairings. Consider having two peer review sessions for the same project to encourage more thought and several rounds of revision.

- Have students review and comment on each other’s work online using Nicenet , a class blog, or class website.

- Have students write a class book, then take turns bringing it home to read. Encourage them to discuss the writing process with their parents or guardians and explain how they offered constructive feedback to help their peers.

Using peer review strategies, your students can learn to reflect on their own work, self-edit, listen to their peers, and assist others with constructive feedback. By guiding peer editing, you will ensure that your students’ work reflects thoughtful revision.

- Lesson Plans

- Strategy Guides

Using a collaborative story written by students, the teacher leads a shared-revising activity to help students consider content when revising, with students participating in the marking of text revisions.

After analyzing Family Pictures/Cuadros de Familia by Carmen Lomas Garza, students create a class book with artwork and information about their ancestry, traditions, and recipes, followed by a potluck lunch.

Students are encouraged to understand a book that the teacher reads aloud to create a new ending for it using the writing process.

While drafting a literary analysis essay (or another type of argument) of their own, students work in pairs to investigate advice for writing conclusions and to analyze conclusions of sample essays. They then draft two conclusions for their essay, select one, and reflect on what they have learned through the process.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Writers Workshop

Conducting Peer Review

Why include peer review in your course.

Writers need feedback on their writing in order to improve. While instructor feedback is valuable, asking students to respond to each other’s writing provides additional opportunities for before-the-deadline feedback without increasing the instructor’s workload.

There are other benefits to peer review, as well: Peer review fosters students’ awareness of their own and others’ writing processes and approaches to the writing task. It gives students practice assessing their own and others’ writing and can reinforce course-specific criteria for writing assignments. Moreover, by both giving and receiving critical feedback, peer review teaches valuable skills like listening, evaluating, responding, and reflecting. Incorporating peer review in your class allows students to gain multiple perspectives on their writing, mimicking the process of peer review in professional knowledge production. Finally, having students engage in active dialogue about their intentions and ideas contributes to a collaborative classroom community.

But Don’t Most Students Hate Peer Review?

Peer review sometimes has a bad reputation. Some students (and instructors) view peer review as unproductive because they’ve received advice that’s too nice or too vague to be helpful, too critical to be constructive, or too focused on surface-level editing issues rather than content. You can overcome these negative perceptions by effectively structuring peer review as a regular course component.

What are Best Practices for Peer Review?

To ensure that peer review benefits both the writer and the reader and leads to substantial revision, instructors need to set ground rules. First, the basics:

- Peer review can be conducted in or out of class, in-person or electronically

- Peer review can be conducted in pairs or groups (many writing scholars recommend groups of 3-4)

- Peer review can be conducted in any number of ways, from having students exchange papers in class to using peer review programs like SWoRD .

- Peer review will need to happen more than once for students to gain practice and fluency

- Peer review should be conducted at least several days before the final submission deadline, to give students enough time make large-scale revisions

- Provide clear parameters and require a deliverable, e.g., a form / handout or a letter to the writer

- Provide coaching and guidance to help students become better peer reviewers

Instructors should prepare students for peer review by discussing your expectations with the class: What makes feedback helpful or unhelpful? What meaningful feedback can writers take from their readers? What criteria should be used to review papers in this class? Consider providing examples or models of the kind of feedback you’d like students to provide.

Effective peer review is a guided, structured process. You’ll need to provide students with focused tasks or criteria. Encourage them to consider their drafts as “works-in-progress” and prompt them to use description rather than evaluative language. For example:

Instead of “Does the paper have a thesis statement” try “In just one to two sentences, state what position you think the writer is taking. Place stars around the sentence that you think presents the thesis.”

Instead of “Is the paper clearly organized?” try “On the back of this sheet, make an outline of the paper.”

Instead of “Is the paper clearly written” try “Highlight (in any color) any passages you had to read more than once to understand what the writer was saying.”

Students should also indicate at least one thing their peer’s writing is doing well. Students aren’t always aware of what’s working in their texts, so having peers provide positive feedback helps them gain insight into readers’ responses.

Instructors can foster metacognition and agency in the writing process by asking writers to prepare memos for their reviewers that contain a brief summary of the paper’s argument and questions pertaining to the current issues they’re struggling with, e.g., “How persuasive is my argument? What additional evidence could I incorporate? Does my paragraph on p. 2 seem too long?”

Finally, for peer review to work, instructors will need to teach revision and talk with students about how to handle constructive criticism. Often, students make changes related to “low-hanging fruit”—wrong words, missed citations—and avoid taking on larger revision challenges, like restructuring a paper or incorporating more persuasive evidence. Those larger changes can be daunting. Remind students that you care more about macro-level issues like content, structure, and genre conventions. You might ask students to write a memo or reflection summarizing their peer review feedback: What revision tasks will they prioritize? What will be most time-consuming? How will they take steps to address the most challenging or time-consuming revision tasks?

You might even share your own strategies for taking on large-scale revision tasks!

Additional Resources:

- Includes general guidelines and a model for structuring peer review

- Planning for peer review

- Helping students offer effective feedback

- Providing guidance on using feedback

- Sample peer review sheets

- Bean, J. (2011). Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom . 2 nd Ed., Chapter 15, “Coaching the Writing Process and Handling the Paper Load”

Related Links:

- Responding to Student Writing

- Incorporating Feedback

Copyright University of Illinois Board of Trustees Developed by ATLAS | Web Privacy Notice

- Majors & Minors

- About Southwestern

- Library & IT

- Develop Your Career

- Life at Southwestern

- Scholarships/Financial Aid

- Student Organizations

- Study Abroad

- Academic Advising

- Billing & Payments

- mySouthwestern

- Pirate Card

- Registrar & Records

- Resources & Tools

- Safety & Security

- Student Life

- For Current Parents

- Parent Council

- Parent Handbook/FAQ

- Rankings & Recognition

- Tactical Plan

- Academic Affairs

- Business Office

- Facilities Management

- Human Resources

- Notable Achievements

- Alumni Home

- Alumni Achievement

- Alumni Calendar

- Alumni Directory

- Class Years

- Local Chapters

- Make a Gift

- SU Ambassadors

Southwestern University announces its 2021–2026 Tactical Plan.

A team of our students ventured to Waco to compete alongside peers from some of the nation’s top universities.

Statewide organization recognizes Southwestern University’s Library staff with “Branding Iron Awards” for excellence in marketing and public relations.

A conversation with Assistant Professor of Sociology Amanda Hernandez.

Chef Daniel Miller II’s bold creation clinches Best Beefy Sandwich title, highlighting the University’s culinary excellence.

America’s largest bookseller to bring a new storefront, expanded textbook and merchandise selections, First Day® Complete program, and more to Southwestern.

Ortiz brings over 30 years of experience to new position at Southwestern.

Business major Abigail Bensman fulfills her Broadway dream while enrolled at Southwestern after being cast as “Brenda” in the North American tour of the Tony Award-winning musical Hairspray .

Southwestern’s inclusivity efforts for the military community recognized with Silver Award.

Learn more about Southwestern University’s Women’s Annex and view a fascinating film clip from over a century ago.

Student bridges theater and technology to create an automatic spotlight tracker.

Discover the thrill of exploration through the Outdoor Adventure Program.

Georgetown’s prime location in the path of totality led to a breathtaking experience for all who attended the Total Eclipse at Southwestern event.

Jaime Hotaling ’23 recounts her transformative journey from SU to Disney.

In May, Southwestern University will welcome Adam Winkler ’04 as the commencement speaker for the graduation ceremony celebrating the class of 2024.

On April 8, 2024, the University invites all to experience an astronomical event.

Explore Southwestern’s Distinctive Collections and Archives trove of love letters throughout history.

Peer Review

Benefits of peer review, how does devoting class time to peer review help student writing.

- Peer review builds student investment in writing and helps students understand the relationship between their writing and their coursework in ways that undergraduates sometimes overlook. It forces students to engage with writing and encourages the self-reflexivity that fosters critical thinking skills. Students become lifelong thinkers and writers who learn to question their own work, values, and engagement instead of simply responding well to a prompt.

- Making the writing process more collaborative through peer review gives students opportunities to learn from one another and to think carefully about the role of writing in the course at hand . The goals of the assignment are clarified. By assessing whether or not individual student examples meet the requirements, students are forced to focus on goals instead of getting distracted entirely by grammar and mechanics or by their own anxiety.

- Studies have shown that even strong writers benefit from the process of peer review : students report that they learn as much or more from identifying and articulating weaknesses in a peer’s paper as from incorporating peers’ feedback into their own work.

- Peer review provides students with contemporary models of disciplinary writing . Because students often learn writing skills in English class, at least in high school, their models for “good writing” might be entirely general or ill-suited to your class. Peer review gives them a communal space to explore writing in the disciplines.

- Peer review allows students to clarify their own ideas as they explain them to classmates and as they formulate questions about their classmates’ writing. This is helpful to writers at all skill levels, in all classes, and at all stages of the writing process.

- Peer review provides professional experience for students having their writing reviewed. Peer review is the process by which professionals in the field publish, it’s how managers and co-workers provide feedback in the workplace, and it’s a skill with practical application.

- Last but not least, peer review minimizes last minute drafting and may cut down on common lower-level writing errors.

Cho, Kwangsu, Christian D. Schunn, and Davida Charney. “Commenting on Writing: Typology and Perceived Helpfulness of Comments from Novice Peer Reviewers and Subject Matter Experts.” Written Communication 23.3 (2006): 260-294.

Graff, Nelson. “Approaching Authentic Peer Review.” The English Journal 95.5 (2009): 81-89.

Nilson, Linda B. “Improving Student Peer Feedback.” College Teaching 51.1 (2003): 34-38.

“Using Peer Review to Help Students Improve Writing.” The Teaching Center . Washington University in St. Louis. n.d. Web. 1 June 2014.

BOLDFACE 101: THE CREATIVE WRITING PEER REVIEW

Workshops are an integral and exciting part of the Boldface experience. At first, however, they can seem intimidating. Don’t worry! This week’s installment of Boldface 101 introduces you to the process of giving and receiving peer reviews.

First and foremost, we urge you to prepare in advance. Thinking deeply about your critiques and making meaningful comments is important. Your classmates are there for the same reasons you are—to improve their writing. Don’t dismiss your role as peer and colleague, what you say matters! We hope you’ll check out the following pointers on giving and receiving feedback.

Giving Feedback to Fellow Writers

The golden rule is universal. Treat your peers and their writing with care and respect. Take this part of the writers conference seriously. You wouldn’t like it if others were inconsiderate of you or your work, so be mindful of how you present your comments. Beyond that, requirements are flexible. Your workshop leader will provide guidance in advance regarding how they want you to approach the process, but here are a few best practices to consider in the meantime:

- Avoid saying what you did or didn’t “like.” These kinds of statements have more to do with opinion and less to do with what is or is not successful in a given piece of writing. You don’t always have to “like” something to see whether it’s worthwhile or whether it’s accomplishing its goal as technique or craft.

- Provide constructive criticism AND reinforcement. It’s always nice to hear what you ARE doing effectively as a writer. Remember to encourage your peers when you spot something you think is especially effective, rather than letting it go unsaid and focusing 100% of your critique on what still needs improvement.

- Be specific. Generic and vague comments aren’t very helpful in a creative writing workshop. Your peer review isn’t going to be useful unless it contains detailed analysis and examples of what is/isn’t working in a piece of writing. Make sure to be specific and elaborate on your ideas.

- Check for author notes. If your peer has asked for feedback on a specific issue, make sure to address their concerns!

Don’t forget—you’ll be receiving feedback, too! Here are some things to remember when receiving constructive criticism:

- It’s not personal. So, don’t take it personally. We understand this is easier said than done, especially when it comes to your writing. But that’s just it. It’s your writing, not you, that’s being critiqued.

- Listen actively and to understand. In other words, don’t just give in to your first reaction, which may be purely defensive. Let your peers complete their thoughts and explain what they mean. Take some time to consider things before deciding whether to incorporate or leave out suggestions.

- Stay open-minded. You might receive some radical insights, but sometimes it’s helpful to try unexpected ideas! Perhaps your short story is the beginning of a novel, or a plot twist reveals itself. Writing is a magical process that can lead you down new paths if you let it. So, try to remain open to possibilities!

- Ask questions! If you don’t understand something, don’t hesitate to ask your group to clarify. That is, after all, why they’re there!

“Imagine spending the day at a coffeeshop filled with unique, passionate, intelligent writers who want to share their knowledge—and listen to you in kind. Now imagine doing that for five days in a row. That’s Boldface.” -Boldface 2017 Participant

We think you’ll find that meeting with the same group multiple times throughout the week makes for a close-knit and supportive environment. Hopefully, this brief guide to the creative writing workshop eliminates any uncertainties you may have. If not, let us know! Reach out anytime to [email protected] , or better yet, get involved in the conversation on Facebook , Twitter , and Instagram !

Don’t forget to check out the rest of the Boldface blog for the scoop on our awesome visiting writers and other useful information. Happy writing (and reviewing)!

Theme: Illdy . Copyright 2021. © All Rights Reserved.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

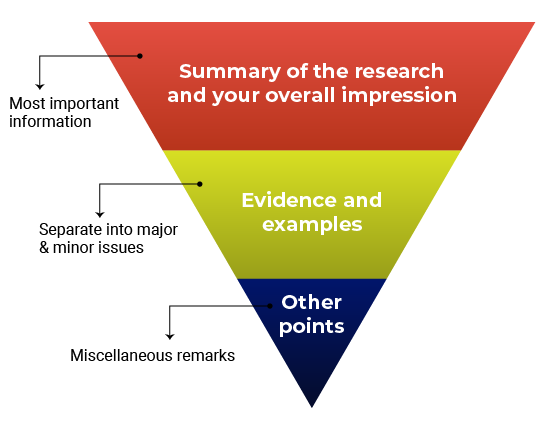

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Search This Blog

Why i write.

Jennifer Semple Siegel: Memoirist, Short Story Writer, Novelist, Occasional Poet

- Articles and Resources

- General Guidelines for Peer Reviewing Creative Works

- Non-fiction

- Non-fiction Review

- Peer Review

- Poetry review

- Short Story Review

Article: General Guidelines for Peer Reviewing Creative Works

Read through the story, poem, or essay once before making any comments on peer sheets or manuscript. For this first reading, you are simply reading as if you were picking up a magazine or short story or poetry collection – in short, a casual reading.

Take a few minutes to think about what you have just read.

On a separate piece of paper (not on the writer’s manuscript), jot down your preliminary impressions (which you may or may not be sharing with the author), e.g. “I don’t like stories or poems about baseball, so I didn’t like this one” or “I didn’t like the grandmother as a person” or “I just love the religious overtones of the piece.” The idea is to get past “personal biases” and “agendas” and get on with offering the author a fair critique based on craft, not personal tastes on the part of the reviewer.

Read the piece again, this time, as you read, jotting down comments on a separate piece of paper. If you discover that you don’t like the piece no matter how many times you read it, try to figure out why . For example, does the story or poem need technical work, or do you have a personal aversion to style, a character, theme, etc.? If so, let the writer know about your biases.

5. Answer Questions

Now look over your notes and answer the questions from the appropriate genre list, for example, Fiction: Peer or Self Reviewing a Short Story .

6. Write a Constructive Critique

Write a constructive critique of the piece. At this point, you may jot down notes on the author’s manuscript. Begin your critique by accentuating the positive. When discussing weaknesses, do so in a spirit of professional respect and a willingness to be helpful. Be honest, but write in a thoughtful and considerate manner – the way that you would want your work to be critiqued. And give the author your best shot!

7. Offer the Critique to the Writer.

When you are finished, distribute the critique, peer list, and manuscript to the author.

8. Offer the Writer the Opportunity to Ask Questions.

Offer the writer time to read over your critique, and be prepared for questions and requests for clarification.

__________________

A slightly different version of this article appears on the author’s academic website AcademicDesk.org

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated. Please... No spam, no links to irrelevant websites, no porn, and/or no hate speech.

For Literary Agents...

- Quick Links

Jennifer's Cloud

- Privacy and Copyright Notice

Photo Credit – NASA

The banner on this site has been created from one of the most iconic photos in modern history: Earthrise as viewed from the Moon. More

Copyright Notice

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, peer review – how to make the most of peer review.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Peer Review , the practice of receiving and providing critiques to improve documents , applications, and services, has been proven to be a valuable tool for writers and critics alike. As summarized below, research highlights the transformative impact of peer review on both the quality of work and the development of essential interpersonal competencies highly sought after in the business realm. Discover how engaging in peer review can enhance your writing prowess and foster valuable skills for professional success.

What is Peer Review?

Peer Review refers to the practice of giving and getting critiques from others in order to improve something–such as a text , application, service. Research, as summarized below, has found that peer review

Peer review not only minimizes bias and improves the quality of work, but also signals the authority of the evaluated text. This process, which involves having multiple people evaluate a piece of work, aims to provide different perspectives and counterbalance individual interpretations. Acknowledging that evaluations often rely on individual judgment, which is inherently subjective and susceptible to personal bias, the peer review process strives to diminish this subjectivity by incorporating multiple perspectives. These evaluators collectively challenge individual biases, providing a more comprehensive and objective assessment. The resulting peer-reviewed work, having stood up to rigorous scrutiny, thus gains a measure of authority in its respective field.

The peer review process manifests differently across various fields, each with its unique considerations. In academic research, for instance, it is used to validate the quality of scholarly articles before they’re published. Experts in the relevant field scrutinize the research methodologies and findings to ensure they are robust and reliable. In the corporate world, peer review might involve colleagues or superiors evaluating a project or proposal, offering feedback to improve the final output and ensure it aligns with company standards–and the needs and expectations of the client. Within the realm of software development, it takes the form of code review where fellow developers inspect code for errors or inefficiencies. In educational settings, students often engage in peer review to critique and learn from each other’s work. Despite the varying forms, the core of peer review remains consistent: using collective wisdom to counterbalance individual bias, improve quality, and convey authority.

Related Concepts: Authority; Collaboration ; Interpersonal Competency ; Collaborative Problem Solving; Teamwork

Types of Peer Reviews

The type of peer review, the number of people on a review panel, and the goals of the writer seeking the review are somewhat dependent on the importance of a decision.

In instances where the outcome will have significant implications, peer review tends to involve multiple anonymous reviewers. For example, when departments of admission at colleges and universities screen applications, they typically ask multiple individuals to review, rank, and vote on applications. Similarly, when undergraduates submit an honors thesis, it is common to have three reviews. At the graduate level, across academic disciplines, multiple reviewers are typically involved in critical milestones such as the thesis proposal or defense.

Collaborative Peer Review

Focuses on collaboration and constructive feedback from multiple critics to improve the work during the developmental stages–including prewriting and drafting .

Goal: Enhancing the quality and effectiveness of the project through collaboration and mutual learning.

Formative Peer Review

Provides feedback and guidance from one or more critics to support the writer’s growth and learning.

Goal: Facilitating skill development and improvement through constructive feedback.

Summative Peer Review

Evaluates the final product against predefined criteria or standards.

Goal: Making decisions regarding publication, grading, funding, or other significant outcomes based on the overall quality and alignment with standards.

Directed Peer Review

Reviewers follow specific guidelines or processes when providing feedback or assessing work.

Goal: Focusing on specific aspects or criteria as directed, such as revision , clarity , or brevity .

Examples of Directed Peer Reviews

- Guide to Structured Revision — this is an example of a structured approach to substantive revision . Teachers or managers could ask you to follow a structured approach like this one in order to take the emotion out of revision and editing .

- Edit for Clarity — this structured exercise focuses on checking texts for brevity .

Open Peer Review or Transparent Peer Review

Reviewers openly identify themselves when providing feedback or evaluating others’ work.

Goal: Promoting transparency, accountability, and direct engagement among peers in work settings.

Problems with Peer Review

Complaints from Students:

Bias and Inconsistency:

- Concerns about reviewers holding personal biases that can influence evaluations, potentially favoring or discriminating against certain methodologies, perspectives, or individuals.

- Frustration with the inconsistency in the quality and rigor of reviews, which hinders students’ ability to assess their work accurately.

Lack of Constructive Feedback:

- Complaints about the absence of actionable suggestions for improvement in peer reviews.

- Frustration when reviewers solely focus on pointing out flaws without providing clear guidance for enhancement.

- Perception that engaging with peer feedback might lead to going down a “rabbit hole” without significant improvement to their grades.

Desire for a Good Grade:

- Priority given to receiving a good grade on assignments.

- Concerns that engaging in peer review may consume time without directly contributing to improved grades.

- Questioning the value of peer review if it does not have a tangible impact on their overall academic performance.

Perception of Unfairness:

- Feeling that the peer review process may lack fairness, with higher expectations for certain institutions or individuals.

- Doubts about equal opportunities for all scholars due to potential biases in the evaluation process.

Feeling of Disparity for Better Writers:

- Better writers in the class may feel like they are contributing more than they are receiving in peer review.

- Concerns that their efforts are not equally matched by their peers’ contributions.

- Encouraging students to take a long-term view, understanding that engaging in peer review allows them to practice their reviewing skills, enhance their ability to provide constructive feedback, and develop important interpersonal competencies.

Complaints from Teachers:

Time Constraints:

- Challenges in managing the time-consuming nature of the peer review process within limited timeframes.

- Potential delays in providing timely feedback due to lengthy review timelines.

- Impediments to collaboration opportunities and the timely dissemination of research findings.

Workload Balancing:

- Difficulties in ensuring an equitable distribution of reviews among students.

- Balancing the workload, especially in larger classes or across multiple sections.

- Ensuring each student receives a fair number of reviews and feedback.

Training and Consistency:

- Concerns about varying levels of expertise among student reviewers.

- Inconsistencies in evaluations and insufficient feedback due to inadequate training or guidelines.

- Challenges in relying on peer reviews as a reliable assessment tool.

Complaints from Professional Writers:

Delays in Publication:

- Reliance on timely publication for reputation building and career advancement.

- Frustration with potential delays caused by lengthy peer review timelines.

- Negative impact on collaboration opportunities and the overall impact of the research.

Lack of Expertise:

- Doubts about the expertise of reviewers, particularly in specialized or niche fields.

- Concerns that evaluations may not accurately reflect the quality or significance of the work.

- Desire for knowledgeable reviewers who can provide insightful feedback.

Revision Fatigue:

- Mental and emotional exhaustion caused by repeated revisions requested by multiple reviewers.

- Overwhelm stemming from the iterative nature of the peer review process.

- Potential hindrance to progress on other projects due to extensive revisions.

Why Does Peer Review Matter?

Peer review is of paramount importance as it serves:

- Experts critically review research, methods, results, recommendations, and conclusions.

- Ensures meticulous vetting of new knowledge claims.

- Upholds integrity and credibility of scholarly discourse.

- Maintains standards of the scientific community.

- Learning is social, and peer responses enhance writers’ texts.

- Saves time and improves writing clarity .

- Early reviews aid invention and rhetorical reasoning .

- Fine-tunes writer’s sense of audience and transitions from writer-based to reader-based prose .

- Students conduct peer reviews in high school and college, especially in composition, creative writing, professional writing, and technical writing courses.

- Ensures alignment with readers’ expectations

- Validates scholarly rigor

- Contributes to knowledge advancement.

What should I do if the paper has loads and loads of errors?

When working on an article undergoing peer review, it’s important to prioritize addressing the bigger picture issues rather than focusing solely on editing for minor errors. Instead, direct your attention to revision concerns, such as the thesis , overall structure , voice , tone , and substance of the article. Consider the following steps:

- Examine the article’s organization and flow. Ensure that the sections and paragraphs are logically sequenced and connected. Make revisions to clarify the main points and enhance the overall coherence of the article.

- Pay attention to the consistency and appropriateness of the article’s voice and tone. Aim for a professional and engaging tone that aligns with the intended audience and purpose of the article. Revise sections where the voice may be inconsistent or where the tone needs adjustment to better convey the intended message.

- Review the central thesis or argument of the article. Make sure it is clearly stated and well-supported by evidence or research. Revise and refine the thesis or argument as needed to ensure its strength and relevance.

- Evaluate the substance and depth of the article’s content. Ensure that the arguments are well-developed, supported by credible evidence, and relevant to the topic. Add or strengthen supporting evidence where necessary to bolster the article’s overall substance.

- Seek Feedback from Peers or Mentors: Share the article with trusted colleagues, mentors, or experts in the field for feedback. Request their insights on the bigger picture issues, such as clarity, coherence, and the strength of the arguments. Use their feedback to guide further revisions and improvements.

Once you have addressed these broader concerns and have a well-structured and substantively strong article, you can then shift your focus to editing for grammar, punctuation, and other minor errors. Prioritizing revision and addressing the bigger picture issues will ensure that your article is compelling, coherent, and effectively conveys your ideas to readers.

What is a Peer Reviewed Article? Book? Website?

Typically, a peer reviewed article is an article that has been reviewed by at least two people who are subject matter experts on the topic the author is addressing.

Are Peer Reviewed Works More Authoritative Than Non Peer Reviewed Works?

Works that have been peer reviewed are generally more authoritative than works that are self published. In academic and scientific journals, journal editors give reviewers guidelines to follow when critiquing submissions. For instance, reviewers may be asked to give feedback

- on whether the document is informed by existing scholarship, especially past articles published in the journal

- on the research methodology

- on the style of writing .

It’s not uncommon for authors to need to revise articles multiple times before they pass peer review and the article is published.

That said, as addressed above, there are different types of feedback, and not all feedback is created equal. You cannot necessarily assume that a peer-reviewed text is authoritative. There are instances, for example, when reviewers may have had a conflict of interest or some sort of bias that interfered with their interpretation and critique . Over time, many peer-reviewed articles have been debunked so whereas peer review is a signal of authority , it’s not a guarantee.

Critical readers are always vigilant about questioning the currency , relevance , authority, accuracy , and purpose behind an author’s presentation of information .

When During Composing is Peer Reviewed Advised?

Traditionally, writers, speakers, knowledge workers wait to receive peer reviews once their texts are fairly well developed. However, when possible, you may find it strategic to seek feedback sooner rather than later. After all, peer review can inform rhetorical analysis (especially audience awareness) and rhetorical reasoning .

How Can I Get the Most from Peer Review as an Author?

- Approach peer review with an open mind and a willingness to learn and improve. Recognize that constructive criticism and diverse perspectives can help refine your work and elevate its quality.

- When submitting your manuscript, provide guidelines or a brief note to reviewers outlining specific aspects or areas you would like them to focus on. Clearly stating your expectations can guide reviewers and ensure their feedback aligns with your objectives.

- Recognize that peer review is meant to provide constructive feedback aimed at strengthening your work. Approach reviewer comments with a receptive attitude, even if they challenge your initial assumptions. Consider each suggestion carefully and evaluate how it can enhance your manuscript.

- When addressing reviewer comments, respond thoughtfully and respectfully. Provide detailed explanations for any revisions made and highlight how you have addressed their concerns. Clearly articulate the changes made to demonstrate your attentiveness to their feedback.

- If any reviewer comments are unclear or require further explanation, don’t hesitate to seek clarification. Engage in a respectful dialogue with reviewers to ensure you fully understand their suggestions and can implement them effectively.

- Maintain a professional demeanor throughout the peer review process. Avoid becoming defensive or dismissive of critical feedback. Remember that constructive criticism is intended to help you improve, and maintaining a professional approach will strengthen your reputation among reviewers and editors.

- Actively participate in peer review activities within your academic or professional community. By engaging in reciprocal peer review, you contribute to the development of a supportive environment and gain insights into the reviewing process from the perspective of a reviewer.

- Take the opportunity to learn from the reviews of others. Reading and analyzing peer reviews of similar manuscripts can provide valuable insights into common pitfalls, recurring feedback themes, and effective strategies for revision.

- Peer review is an iterative process. Use the feedback received to refine and enhance your work continually. Embrace the mindset of ongoing improvement, recognizing that each round of peer review offers an opportunity to strengthen your manuscript.

- Whether your manuscript is accepted or rejected, view each outcome as a learning experience. Celebrate successes, but also reflect on rejection to identify areas for improvement. Use the feedback provided to refine your work for future submissions.

Appendix – Empirical Studies on Peer Review

Below are some informal notes from research on peer review. (My apolgies this isnt up-to-date)

Meta-analyses of peer review

Related articles:.

Online Forums: Responding Thoughtfully

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Jennifer Janechek

Assigned a discussion post for a class? Follow these strategies to create a professional rhetorical stance in your posts.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Jason Roberts

Students, you are here because you have probably been assigned a peer review. You may also be looking at this title as an oxymoron. In this short video, however, I hope to give you some insight into what you can both give and receive in a peer review to make this a positive experience for your writing development. As you watch the short presentation, please keep an open mind and consider what you can use in your upcoming reviews that will allow you to change your perspective on getting and giving criticism.

[VIDEO TRANSCRIPT]

Ok, you have to do peer reviews. You know this is going to be a terrible waste of time, right? If your previous experiences with peer review were anything like mine, then it went something like this:

- I had to bring in three copies of my “polished” writing.

- I reluctantly moved into a small group and stared at the other members.

- The teacher made us trade our papers with the other members of my group.

- I was supposed to read them and find two things that were good and at least two that were bad.

- I quickly read the papers and marked some stuff that seemed wrong, then I got my papers back from all of the other students and they had given comments like “good introduction,” “I like your ideas,” “it’s great!” They marked a few spelling or grammar errors to fix.

- I went home and fixed those and then my stupid paper was done. ☺

Unfortunately, I hadn’t actually reconsidered how I had written anything. I wasn’t sure if it was important or meaningful, and my peers had not really commented on what I said, only what the teacher wanted. The feedback I had gotten from the other students and even the comments I made on my peers’ papers were meaningless and confused since I was just doing the requirement for the teacher, so I wasn’t interested in what they were saying and didn’t really know what I could possibly say. In fact, I didn’t feel like I even understood what we were supposed to be doing on the paper.

So frustrating!

But now, you have to do a peer review again. “Why?” you may ask. Well, as a long-time teacher of so many students at SLCC, I will try to explain the benefits of a peer review and then how you can actually have a positive experience with the review process.

- You can see other students’ work and how they interpreted the assignment.

- You can have another person see your work who has no authority to grade your work, so there is much less risk.

- You can use this opportunity to find questions and get them answered.

- You can learn valuable workforce skills of collaboration and learning to give effective feedback.

However, if you just give the same feedback that you always have before, then you will continue to find this to be a fruitless, frustrating, and time-wasting activity.

A lot of what makes any learning activity better is preparation. So before you begin reading their writing, there are some things to understand.

UNDERSTAND YOUR POSITION

As a peer: A peer is a person in the same power position. You have no authority to demand that a person has to change. You probably have about the same knowledge and abilities as the person whose paper you will review. You don’t have any special skills that allow you to give special feedback aside from being a person with a brain and an opinion. Your position is only to offer suggestions and recommendations.

As a reader: As a student, you may feel inadequate to review another student’s work. If you were supposed to grade their paper, you would be correct; however, you already give evaluations on so many other things that you are not an expert in. You discuss movies, give evaluations on restaurants, assess professional sports teams and how they are run. The only qualification you have in those regards is that you as a person know what you enjoy and what bores you. You know if you are confused or inspired. As a reader, you are not grading on if they did the assignment but more if what they produced works for an audience.

As a safeguard: Often we are worried about giving criticism to another person because we don’t want to hurt their feelings . Imagine then that your friend is about to give a speech to a large audience. They ask you how they look. Imagine that they have missed a button on their shirt, or their hair is out of place, or their zipper is down. What kind of friend would not tell them that they needed to fix their appearance?! Now consider that they are going to be publishing their writing; it is going to a teacher to be graded. Wouldn’t you want to give that person all the advice you could, so they would be as successful as possible?

UNDERSTAND THE ASSIGNMENT

Now that you understand your position, you need to make sure you understand the writing situation.

Requirements: What are the absolute requirements for the writing assignment? You should have them in front of you while you are reviewing the paper; also, if you don’t understand them yourself, make sure that you ask questions of the instructor.

Intentions: Besides understanding the specific requirements, you should have an idea of why the teacher is giving this assignment. What is the purpose of the writing and what is the instructor hoping for as a result? For example, is this supposed to be creative, or informative?

Learning outcomes: What is the assignment trying to teach? If you know what the purpose of the writing is, you can give better feedback, by helping your peer in their writing development. It happens often that we write to the requirements, but miss the point of the writing.

UNDERSTAND THE AUTHOR

Background : The better you understand who the author is, the better you will understand their writing.

Voice: When a person is writing, it is important to be able to hear their own style in the writing. If a person is faking a paper or if they are using terms or even copying texts, then being able to recognize their voice is important to make a paper more authentic and honest.

Purposes: Recognize what drives the author of the piece. It’s important as you give feedback to give it in a way that it will be received. If the person is just looking for some key points, then too much feedback can be overwhelming, but if they are lost, if you don’t give direction, they will be frustrated as well.

UNDERSTAND THE SITUATION OF THE PIECE

I know that we just discussed a lot of things that may seem like the situation of the writing, but in school the writing situation is often different than the assignment situation. The student is writing to the teacher, about a subject they don’t care about, to get a good grade, but the writing may be to write an opinion letter to a congressman on a recent law that was passed. Because school often puts us in hypothetical situations, it is important that you understand your peer’s writing situation.

Audience: Who is the writing supposed to be written for?

Purpose: What is the specific purpose of the writing: persuasive, informative, instructive, or entertaining?

Subject: What is the writing supposed to be about? Do they stay on that subject?

Context: Is it clear what, who, why, when, where, and how this writing is situated?

Ok, I know that’s a lot. It’s almost too much, you may say. I am not giving this to you as a list. These are just understandings. You have to remember that you are there to help. You can only give what you see, but if you realize how helpful you can be to your peer, you will be prepared to make a very positive impact on their writing.

Now that you have your own position firmly in your mind, you can read the paper. Make sure you have a place to write down ideas. If you can write on their paper or give online feedback or even if you are just discussing the ideas, if you have an idea or share a thought, but you don’t write it down, YOUR IDEA WILL BE FORGOTTEN!

PROVIDE FEEDBACK

Making positive comments: It’s important that the person you are reviewing hears what is going well. Discuss parts specifically that you liked. Considering the purpose of the paper, what informed, instructed, persuaded or entertained you in the text? Use “because” in every sentence.

EXAMPLE: I liked the introduction because …

If you only say you liked something or didn’t like something, it doesn’t help the writer to know what worked for them.

Giving constructive criticism: Constructive criticism is identifiable because it doesn’t just point out what’s wrong, but it gives suggestions on how it could be better.

- Focus on requirements : First of all, did they meet the requirements? If they missed something, be sure to point it out. Those are points they will miss for sure if you don’t help.

- Focus on meaning : After you know that you have covered the requirements, look at what they are saying. Is it clear what they are saying? Did they give enough evidence to support their ideas? Were there parts that you wanted to hear more, were there parts that you still had questions? Put those comments in to give ideas of how to revise their paper.

- Look for “speed bumps”: Something I like to explain is to look for speed bumps in the writing. When you are reading something, was there anything that seemed to stop your reading, that confused you, that bored you, that distracted you, that tied your tongue? Pay attention to what your brain is doing. It will usually tell you when something could be revised. Remember that when you give feedback, you don’t have to be right, just point out your thoughts and let the author decide if they want to take your advice or not.

Peer reviews can be some of the most rewarding parts of writing. Sharing with others can make us feel vulnerable, but getting feedback that encourages and directs us to be able to have a stronger message helps us to feel more confident about what we are writing and more likely to be excited to publish.

Open English @ SLCC Copyright © 2016 by Jason Roberts is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Engaging in Peer Review

There are times when we write in solitary and intend to keep our words private. However, in many cases, we use writing as a way of communicating. We send messages, present and explain ideas, share information, and make arguments. One way to improve the effectiveness of this written communication is through peer-review.

What is Peer-Review?

In the most general of terms, peer-review is the act of having another writer read what you have written and respond in terms of its effectiveness. This reader attempts to identify the writing's strengths and weaknesses, and then suggests strategies for revising it. The hope is that not only will the specific piece of writing be improved, but that future writing attempts will also be more successful. Peer-review happens with all types of writing, at any stage of the process, and with all levels of writers.

Sometimes peer-review is called a writing workshop.

What is a Writing Workshop?

Peer-review sessions are sometimes called writing workshops. For example, students in a writing class might bring a draft of some writing that they are working on to share with either a single classmate or a group, bringing as many copies of the draft as they will need. There is usually a worksheet to fill out or a set questions for each peer-review reader to answer about the piece of writing. The writer might also request that their readers pay special attention to places where he or she would like specific help. An entire class can get together after reading and responding to discuss the writing as a group, or a single writer and reader can privately discuss the response, or the response can be written and shared in that way only.

Whether peer-review happens in a classroom setting or not, there are some common guidelines to follow.

Common Guidelines for Peer-Review

While peer-review is used in multiple contexts, there are some common guidelines to follow in any peer-review situation.

If You are the Writer

If you are the writer, think of peer-review as a way to test how well your writing is working. Keep an open mind and be prepared for criticism. Even the best writers have room for improvement. Even so, it is still up to you whether or not to take the peer-review reader's advice. If more than one person reads for you, you might receive conflicting responses, but don't panic. Consider each response and decide for yourself if you should make changes and what those changes will be. Not all the advice you get will be good, but learning to make revision choices based on the response is part of becoming a better writer.

If You are the Reader

As a peer-review reader, you will have an opportunity to practice your critical reading skills while at the same time helping the writer improve their writing skills. Specifically, you will want to do as follows:

Read the draft through once

Start by reading the draft through once, beginning to end, to get a general sense of the essay as a whole. Don't write on the draft yet. Use a piece of scratch paper to make notes if needed.

Write a summary

After an initial reading, it is sometimes helpful to write a short summary. A well written essay should be easy to summarize, so if writing a summary is difficult, try to determine why and share that with the writer. Also, if your understanding of the writer's main idea(s) turns out to be different from what the writer intended, that will be a place they can focus their revision efforts.

Focus on large issues

Focus your review on the larger writing issues. For example, the misplacement of a few commas is less important than the reader's ability to understand the main point of the essay. And yet, if you do notice a recurring problem with grammar or spelling, especially to the extent that it interferes with your ability to follow the essay, make sure to mention it.

Be constructive

Be constructive with your criticisms. A comment such as "This paragraph was boring" isn't helpful. Remember, this writer is your peer, so treat him/her with the respect and care that they deserve. Explain your responses. "I liked this part" or "This section doesn't work" isn't enough. Keep in mind that you are trying to help the writer revise, so give him/her enough information to be able to understand your responses. Point to specific places that show what you mean. As much as possible, don't criticize something without also giving the writer some suggestion for a possible solution. Be specific and helpful.

Be positive

Don't focus only on the things that aren't working, but also point out the things that are.

With these common guidelines in mind, here are some specific questions that are useful when doing peer-review.

Questions to Use

When doing peer-review, there are different ways to focus a response. You can use questions that are about the qualities of an essay or the different parts of an essay.

Questions to Ask about the Qualities of an Essay

When doing a peer-review response to a piece of writing, one way to focus it is by answering a set of questions about the qualities of an essay. Such qualities would be:

Organization

- Is there a clearly stated purpose/objective?

- Are there effective transitions?

- Are the introduction and conclusion focused on the main point of the essay?

- As a reader, can you easily follow the writer's flow of ideas?

- Is each paragraph focused on a single idea?

- At any point in the essay, do you feel lost or confused?

- Do any of the ideas/paragraphs seem out of order, too early or too late to be as effective as they could?

Development and Support

- Is each main point/idea made by the writer clearly developed and explained?

- Is the support/evidence for each point/idea persuasive and appropriate?

- Is the connection between the support/evidence, main point/idea, and the overall point of the essay made clear?

- Is all evidence adequately cited?

- Are the topic and tone of the essay appropriate for the audience?

- Are the sentences and word choices varied?

Grammar and Mechanics

- Does the writer use proper grammar, punctuation, and spelling?

- Are there any issues with any of these elements that make the writing unreadable or confusing?

Revision Strategy Suggestions

- What are two or three main revision suggestions that you have for the writer?

Questions to Ask about the Parts of an Essay

When doing a peer-review response to a piece of writing, one way to focus it is by answering a set of questions about the parts of an essay. Such parts would be:

Introduction

- Is there an introduction?

- Is it effective?

- Is it concise?

- Is it interesting?

- Does the introduction give the reader a sense of the essay's objective and entice the reader to read on?

- Does it meet the objective stated in the introduction?

- Does it stay focused on this objective or are there places it strays?

- Is it organized logically?

- Is each idea thoroughly explained and supported with good evidence?

- Are there transitions and are they effective?

- Is there a conclusion?

- Does it work?

Peer-Review Online

Peer-review doesn't happen only in classrooms or in face-to-face situations. A writer can share a text with peer-review readers in the context of a Web classroom. In this context, the writer's text and the reader's response are shared electronically using file-sharing, e-mail attachments, or discussion forums/message boards.

When responding to a document in these ways, the specific method changes because the reader can't write directly on the document like they would if it were a paper copy. It is even more important in this context to make comments and suggestions clear by thoroughly explaining and citing specific examples from the text.

When working with an electronic version of a text, such as an e-mail attachment, the reader can open the document or copy/paste the text in Microsoft Word, or other word-processing software. In this way, the reader can add his or her comments, save and then send the revised document back to the writer, either through e-mail, file sharing, or posting in a discussion forum.

The reader's overall comments can be added either before or after the writer's section of text. If all the comments will be included at the end of the original text, it is still a good idea to make a note in the beginning directing the writer's attention to the end of the document. Specific comments can be inserted into appropriate places in the document, made clear by using all capital letters enclosed with parenthesis. Some word-processing software also has a highlighting feature that might be helpful.

Benefits of Peer Review

Peer-review has a reflexive benefit. Both the writer and the peer-review reader have something to gain. The writer profits from the feedback they get. In the act of reviewing, the peer-review reader further develops his/her own revision skills. Critically reading the work of another writer enables a reader to become more able to identify, diagnose, and solve some of their own writing issues.

Peer Review Worksheets

Here are a few worksheets that you can print out and use for a peer-review session.

Parts of an Essay

- My audience is:

- My purpose is:

- The main point I want to make in this text is:

- One or two things that I would appreciate your comments on are:

- After reading through the draft one time, write a summary of the text. Do you agree with the writer's assessment of the text's main idea?

- In the following sections, answer the questions that would be most helpful to the writer or that seem to address the most relevant revision concerns. Refer to specific places in their text, citing examples of what you mean. Use a separate piece of paper for your responses and comments. Also, write comments directly on the writer's draft where needed.

- Is it effective? Concise? Interesting?

- Is there a conclusion? Does it work?

Finally, what are two or three revision suggestions you have for the writer?

Qualities of an Essay

- After reading through the draft one time, write a summary of the text.

- In the following sections, answer the questions that would be most helpful to the writer or that seem to address the most relevant revision concerns. Use a separate piece of paper for your responses and comments. Also, write comments directly on the writer's draft where needed.

- Is the connection between the support/evidence, main point/idea, and the overall point of the essay made clear?Is all evidence adequately cited?

Salahub, Jill . (2007). Peer Review. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=43

- Our Mission

Centering Classroom Values in Peer Writing Workshops

By structuring peer feedback processes with intention, teachers can help students develop reflection and communication skills.

“What is more challenging for you—giving feedback or receiving feedback? Why do you think that is?”

I project this question on the board when students walk into our peer writing workshop. Along with helping them enter into the activity, it reveals the purpose driving our work: to become stronger at providing and receiving feedback—skills that translate beyond the classroom.

Peer workshops are some of the best days in our classroom. Below, I share practices I’ve found effective when facilitating these interactions in the writing classroom, transferable across units and contexts.

Teacher Preparation

There are many approaches to peer feedback, but over the years I’ve found two priorities key in the planning stage:

- Being intentional about the piece of writing students share. Less is more. Setting constraints for shorter pieces saves time on feedback day. And having the first peer workshop take place with creative or narrative writing allows students to get to know each other, as opposed to analytical or more standardized prompts.

- Establishing classroom values around growth and generosity. We introduce and reflect upon classroom core beliefs at the start of the year, centering these values. We circle back to them frequently; very intentionally, our classroom environment becomes a collaborative one—a critical precursor to peer workshops.

I also give students time in class to plan and write pieces they will workshop. Giving them time helps them feel confident and prepared and allows them to get support in person if needed.

Pre-Workshop Reflection

No matter how prepared students feel, they will likely also feel some anxiety on workshop day—a natural part of sharing work with others.

I begin by having students go through these four norms as a class, selecting one they want to prioritize and sharing their selection with their group members:

- Generosity: Assuming 100 percent in your peers and giving 100 percent as a result in terms of investment and feedback.

- Curiosity: Entering into the space with a willingness to learn from the writing and feedback of those around you .

- Growth: Prioritizing how you can grow, not only in your own writing but also in receiving and providing feedback.

- Perspective: Valuing and engaging with how your own way of seeing things may be different than others’.

By talking through these norms and sharing priorities, students feel a sense of ownership and intentionality entering into workshopping—and practice important real-life self-advocacy skills.

As we begin the workshop, I have students attach a template to their draft for peers to fill out, by hand or digitally, thereby structuring feedback. Our template is built around Marisa Thompson’s close-reading TQE method , with students recording thoughts and questions as they read, noting the most important line and describing why, then noting an epiphany or major takeaway.

Next, students write their own “driving question” at the top of the feedback template—what do they want those reading their piece to focus on, or what are they most curious about regarding others’ perspectives? Naming the focus area you’d most like feedback on is another element of self-advocacy.

Finally, students share digital drafts, asking reviewers to make copies so that writers can’t see the feedback process as it unfolds and are able to stay present with the draft they’re reviewing.

Silent Workshopping

I require the classroom to be 100 percent silent during the feedback stage. Students are typically in trios, which means they have two peer writing samples to review. We split the silent feedback time in half, and I tell them when to switch to the next draft. I ask them to hold clarifying questions and commentary to stay true to our norm of being 100 percent invested in the feedback being provided.

For shorter texts (e.g., 200-to-300-word flash fiction), they get approximately 10 minutes per piece for reading and feedback, doing their best to complete the template. This becomes a really cool space too, as you can almost feel students drifting away from initial anxieties while losing themselves in the reading of each other’s work and the offering of intentional, constructive feedback.

Collaborative Workshopping

When it comes time to share feedback, I ask students to listen to feedback aloud without opening up their own text that is now filled with written feedback. Instead, they listen silently as both of their partners explain their noticings and wonderings first—a process designed to prioritize listening and being a willing recipient of feedback.

A few tips I’ve acquired over the years make this a smoother process:

- Outline the process and project instructions early on. For example, “Partner A will receive feedback from Partner B and Partner C, and then….” Once students dive in, it’s hard to slow them down!

- Have feedback recipients take notes. This gives them a place to prepare follow-up questions and clarifications while actively listening to feedback—another “beyond the classroom” skill.

- Allow groups to move at their own pace. I used to have minute-by-minute plans, but I’ve realized it’s much better to give each group space to move on only when they’re ready. To accommodate this, I have an independent reflection activity ready for them—that way, space is there for some groups to take longer than others.

Significance