Announcing 50 New Case-Based Questions in NEJM Knowledge+ Internal Medicine Board Review

At NEJM Knowledge+, we’re committed to ensuring that our products cover the breadth of knowledge that clinicians need for both clinical practice and Internal Medicine Board Exam preparation. NEJM Knowledge+ Internal Medicine Board Review already contains more than 1600 case-based questions on the most relevant and important topics in medicine today. We’re adding another 50 case-based questions now (and 50 more in December 2016) to further expand that knowledge base.

Most of the 50 new questions we’ve added relate to the following topics:

- Infectious Disease

- Dermatology

Each year, we plan to add at least 100 new questions to NEJM Knowledge+ Internal Medicine Board Review — this is in addition to continually updating our content when guidelines change and in response to user feedback. Our goal is to become increasingly comprehensive in the learning we provide while remaining as clinically relevant and up-to-date as possible.

Covering the ABIM Blueprint with New Learning Objectives

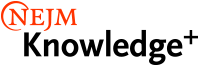

In June 2015, ABIM rolled out a revised blueprint for the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) exam that not only listed the topics and subtopics but also showed the likelihood of which aspects of the subtopic will be on the exam, such as diagnosis, testing, and treatment.

Our editorial team analyzed the new ABIM blueprint and are prioritizing development of new IM questions that map to topics in the blueprint that are highly likely to be on the MOC exam.

We have derived learning objectives from the topic/task combinations in the blueprint; for example, ABIM lists six subtopics under “ischemic heart disease”:

These subtopics mostly fall into the “highly likely to be on the exam” bucket (green), so we recruited physician experts to write case-based questions that test those learning objectives that we did not already have at least one question on in our question bank. Here are some examples of the learning objectives we just added to the IM question bank:

- Choose an optimal initial testing strategy for a patient with a prior acute anterior myocardial infarction who presents with a transient ischemic attack that has a suspected cardioembolic source.

- Choose an appropriate treatment for improving the likelihood of survival in a patient who has depressed left ventricular systolic function after an acute myocardial infarction.

- Choose appropriate evaluation for suspected heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

- Choose the most appropriate pharmacologic management for a patient who has a recent diagnosis of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and is already taking an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

- Recognize heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, secondary to ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Using this process for content development ensures that our question bank covers what you need to know for the board exam.

Case-Based Questions, Free from Outside Influence

All the questions we develop for NEJM Knowledge+ Internal Medicine Board Review meet the same high-quality standards you’ve come to expect from NEJM Group. The content was written by more than 300 clinicians from academic programs across the country and was subjected to a rigorous editorial process that included review by highly respected professional educators, leading specialists in their fields, generalists, PAs, and NEJM Group editors . You can be sure that what you’re learning in NEJM Knowledge+ is accurate, evidence-based, and relevant to your daily practice.

NEJM Knowledge+ offers a comprehensive question bank that reflects the breadth of primary care cases that physicians encounter in their practices today.

Personalized Learning, Tailored to You

NEJM Knowledge+ uses adaptive learning technology that tailors your learning to your needs. This adaptive learning technology continuously assesses the subjects you know and identifies the areas where you need reinforcement. It then delivers questions based on what you know already, what you need to study more, what you are struggling to master, what you think you know better than you do, and what you might be forgetting.

With the addition of these 50 new questions, NEJM Knowledge+ Internal Medicine Board Review now includes:

- more than 1680 case-based questions

- more than 4500 total questions tied to 2500 learning objectives

With the ability to earn:

- CME credits

- ABIM MOC points

All in all, we are strengthening one of the most comprehensive solutions available for continuous learning and board exam preparation.

More on NEJM Knowledge+ Content:

Roadmap to Great Content Work Less and Learn More: Here’s How in NEJM Knowledge+ Content Updates

Share This Post!

Having only a partial point of view of Cases Based Questins,I can see that you tried to do the best work in this section.I am totally sure, that the Clinical Cases presented will be carefully prepared.But, the problem that I see, in ER,Clinics-Hospitals-and in Home , it is that the patient, many times has not the Diagnostics written in his/her Chest.Many times, we have to do an intense work,trying to know what happen with the patients and trying to find(if we are in ER or Hospital) his/her medical record. Being agree with the way you prepared the questions,but I think that in Real Life,we have to face with patients, whose Diagnostics, we do not know,but we have to start with some measuresEx=relieving pain-giving IV solutions (if they are needed)-taking Exams, like Blood-Urina and others-XRay-CT Scan-Ultrasound and calling to others Physicians(Specialists=Cardiologists-Neurologists-Nephrologists etc-etc= so I suggest to add(if if is possible) some Complete Clinical Cases, where Students or Residents, must choose since the beginning the possible diagnostics-type of Blood-Urine -Bacteriologic Exams-Ultrasound-CT-Scan etcetcThis type of Questions(that NEJM sometimes present)are one of the best technique to know what the

Notify me by email with any comment

does anyone know of any journal/quis cme’s that are accepted for moc points in internal medicine? Also it seems like it varies from state to state. For example, JAMA articles/cme quizzes for some reason aren’t accepted in NY. I left my email if anyone should have any information. Thanks much

Comments are closed.

- McMaster University Health Sciences Library

Medicine - Undergraduate

- Case Scenarios

- Students from a Non-Science Background

- Anatomy & Physiology

- Clinical Skills

- Drugs & Natural Products

- EBM & JAMA Evidence

- PICO: writing a searchable question

- Black & Indigenous Health Resources

- Research Support - Book a Consult

- Landmark Papers

- Student Wellness

Case Studies & Scenarios

- Johns Hopkins Medicine- Case Studies

- Case Studies for Fellows (American Society of Hematology)

- LITFL Clinical Cases Dedicated to Emergency Medicine and Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine Cases Canadian medical education podcast

- NEJM Clinical Cases

- Springer Clinical Cases series A catalogue search

- << Previous: LMCC Prep

- Next: Anatomy & Physiology >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 11:09 AM

- URL: https://hslmcmaster.libguides.com/medicine_UGM

Address Information

McMaster University 1280 Main Street West HSC 2B Hamilton, Ontario Canada L8S 4K1

Contact Information

Phone: (905) 525-9140 Ext. 22327

Email: [email protected]

Make A Suggestion

Website Feedback

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

- Biochemistry

- Microbiology

- Neuroscience

- Pharmacology

- Anesthesiology

- Emergency Medicine

- Family Medicine

- Internal Medicine

- Clinical Neuroanatomy Cases

- Clinical Nutrition Cases

- Acid-Base Disturbance Cases

- Chest Imaging Cases

- Family Medicine Board Review

- Fluid/Electrolyte and Acid-Base Cases

- G&G Pharm Cases

- Harrison’s Visual Case Challenge

- Internal Medicine Cases

- Medical Microbiology Cases

- Pathophysiology Cases

- Principles of Rehabilitation Medicine Case-Based Board Review

- Browse by System

- Internal Medicine Med-Peds Pediatrics

- Browse by Curriculum

Case Files: Family Medicine, 5e

Author(s): Eugene C. Toy; Donald Briscoe; Bruce Britton; Joel J. Heidelbaugh

- 51 Diabetes Mellitus

- 59 Opioid Use Disorder and Chronic Pain Management

- 7 Tobacco Use and Cessation

- 20 Chest Pain

- 42 Palpitations

- 53 Acute Low Back Pain

- 3 Joint Pain

- 18 Geriatric Health Maintenance and End-of-Life Issues

- 49 Breast Diseases

- 47 Dyspepsia and Peptic Ulcer Disease

- 40 Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- 46 Jaundice

- 9 Anemia in the Geriatric Patient

- 45 HIV, AIDS, and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections

- 48 Fever and Rash

- 2 Dyspnea (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)

- 24 Pneumonia

- 56 Wheezing and Asthma

- 21 Chronic Kidney Disease

- Acute Low Back Pain

- Anemia in the Geriatric Patient

- Breast Diseases

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Dyspepsia and Peptic Ulcer Disease

- Dyspnea (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)

- Fever and Rash

- Geriatric Health Maintenance and End-of-Life Issues

- HIV, AIDS, and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Opioid Use Disorder and Chronic Pain Management

- Palpitations

- Tobacco Use and Cessation

- Wheezing and Asthma

PICO: Form a Focused Clinical Question

- 1. Ask: PICO(T) Question

- 2. Align: Levels of Evidence

- 3a. Acquire: Resource Types

- 3b. Acquire: Searching

- 4. Appraise

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Case Study Example

- Practice PICO

Formulate a Clinical Question from a Case Study

- Case: Hypertension

I: Intervention

C: comparison.

- PICO: Putting It Together

Clinical Scenario

A 68-year-old female patient has recently been diagnosed with high blood pressure. She is otherwise healthy and active. You need to decide whether to prescribe her a beta-blocker or an ACE inhibiter.

Image: "Blood pressure measuring. Doctor and patient. Health care." by agilemktg1 is marked with CC PDM 1.0

► Click on the P: Patient tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

(Case study from EBM Librarian: Teaching Tools: Scenarios .)

Consider when choosing your patient/problem:

- What are the most important characteristics?

- Relevant demographic factors

- The setting

Patient: adult hypertensive female

Image: "Nurse measuring blood pressure of senior woman at home. Looking at camera, smiling.?" by agilemktg1 is marked with CC PDM 1.0

► Click on the I: Intervention tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

Consider for your intervention:

- What is the main intervention, treatment, diagnostic test, procedure, or exposure?

- Think of dosage, frequency, duration, and mode of delivery

Intervention: beta-blocker

Image: "Atenolol Blood Pressure Tablets Image 4" by Doctor4U_UK is licensed under CC BY 2.0

► Click on the C: Comparison tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

Consider for your comparison:

- Inactive control intervention: Placebo, standard care, no treatment

- Active control intervention: A different drug, dose, or kind of therapy

Comparison: ACE inhibiter

Image: "Ramipril Blood Pressure Capsules Image 5" by Doctor4U_UK is licensed under CC BY 2.0

► Click on the O: Outcome tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

Consider for your outcome:

- Be specific and make it measurable

- It can be something objective or subjective

Outcome: relief of symptoms; controlled blood pressure

Image: "File:BP B6 Connect blood pressure monitor.png" by 百略醫學 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

► Click on the PICO: Putting It Together tab to proceed in developing a clinical question.

Formulate a PICO Question

Answerable PICO Question: In middle-aged adult females with hypertension, are beta blockers more effective than ACE inhibiters in controlling blood pressure?

Image: "Dagstuhl 2008-02-01 - 37" by Nic's events is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Suggested MeSH Terms: Adrenergic beta-Antagonists/therapeutic use; Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/therapeutic use; hypertension/drug therapy

Tip: Incorporating sex into the search may not be necessary unless there is a significant difference between males and females in relevant studies.

Click "Next" below to practice formulating clinical questions using PICO format.

- << Previous: Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Next: Practice PICO >>

- Last Updated: Oct 5, 2023 2:35 PM

- URL: https://med-fsu.libguides.com/pico

Maguire Medical Library Florida State University College of Medicine 1115 W. Call St., Tallahassee, FL 32306 Call 850-644-3883 (voicemail) or Text 850-724-4987 Questions? Ask us .

- Advanced Life Support

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Infectious disease

- Intensive care

- Palliative Care

- Respiratory

- Rheumatology

- Haematology

- Endocrine surgery

- General surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Plastic surgery

- Vascular surgery

- Abdo examination

- Cardio examination

- Neurolo examination

- Resp examination

- Rheum examination

- Vasc exacmination

- Other examinations

- Clinical Cases

- Communication skills

- Prescribing

ABG Examples (ABG exam questions for medical students and PACES)

ABG Examples (ABG exam questions for medical students OSCEs and MRCP PACES)

Below are some brief clinical scenarios with ABG results. Try to interpret each ABG and formulate a differential diagnosis before looking at the answer.

Question 1.

You are called to see a 54 year old lady on the ward. She is three days post-cholecystectomy and has been complaining of shortness of breath. Her ABG is as follows:

- pH: 7.49 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 7.5 (10–14)

- pCO2: 3.9 (4.5–6.0)

- HCO3: 22 (22-26)

- BE: -1 (-2 to +2)

- Other values within normal range

- This is type 1 respiratory failure. The PO2 is low with a low CO2.

- The accompanying alkalosis is a response, due to the patient blowing off CO2 due to her likely high respiratory rate.

What is the differential diagnosis?

- Pulmonary embolus (PE)

- Pulmonary oedema

- Pneumothorax

- Severe atelectasis

What would you do?

- Acutely unwell: ABCDE and call for help

- All of these conditions can may you tachypnoeic and tachycardic. Wheeze will predominate in asthma. Pyrexia points more towards pneumonia (but PE can give a mild pyrexia). Pulmonary embolus will be the only condition that will likely be normal on auscultation.

- Sudden onset: more likely PE

- Purulent cough: more likely pneumonia

- Raised JVP, ankle swelling, fine basal creps: more likely oedema

- Cultures if pyrexial

- PE : Heparinisation or thrombolysis if unstable. Remember this patient is post-op so it is a complex decision.

- Pneumonia : Antibiotics for hospital acquired pneumonia

- Asthma : Salbutamol, ipatropium and steroid in the first instance

- Pulmonary oedema : Sit patient up, furosemide, consider catheter

Question 2.

A 75 year old gentleman living in the community is being assessed for home oxygen. His ABG is as follows:

- pH: 7.36 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 8.0 (10–14)

- pCO2: 7.6 (4.5–6.0)

- HCO3: 31 (22-26)

- BE: +5 (-2 to +2)

- This does not represent acute pathology.

- Rather it reflects a compensation for a chronic respiratory acidosis secondary to chronic pulmonary disease.

- Note this is an acidosis, not an acidaemia (pH normal, but only due to compensatory mechanisms: the high bicarbonate).

- Lifestyle advice and smoking cessation of necessary.

- PaO 2 less than 7.3 kPa when stable.

- Secondary polycythaemia

- Peripheral oedema

- Nocturnal hypoxaemia

- Pulmonary hypertension

Question 3.

A 64 year old gentleman with a history of COPD presents with worsening shortness of breath and increased sputum production .

- pH: 7.21 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 7.2 (10–14)

- pCO2: 8.5 (4.5–6.0)

- HCO3: 29 (22-26)

- BE: +4 (-2 to +2)

- Note that the HCO3 is raised in this patient despite the abnormal pH.

- With the above history this is likely to represent an acute on chronic respiratory acidosis.

- This would indicate that the patient normally retains CO2 and has a chronically raised HCO3.

- The drop in pH represents the normal mechanisms of compensation being over whelmed.

- This is one of the cases where having an old ABG from a previous admission can be useful.

How much oxygen would you give this man?

- Oxygen administration in this group is a complicated issue. 100% oxygen makes subsets of COPD patients retain CO2, decreasing respiratory drive and worsening hypoxia and hypercapnia.

- More information can be found on this page: Prescribing oxygen in COPD patients

- The British Thoracic Society have produced guidelines which give a helpful overview and can be found here.

Question 4.

A 21 year-old woman presents feeling acutely lightheaded and short of breath. She has her final university exams next week.

- pH: 7.48 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 13.9 (10–14)

- pCO2: 3.5 (4.5–6.0)

- HCO3: 22 (22-26)

- BE: +2 (-2 to +2)

- This is a respiratory alkalaemia

- Pulmonary disease

- Hypermetabolic states (e.g. infection or fever)

- Anxiety hyperventilation

What's the most likely diagnosis?

- Based on the history, anxiety hyperventilation is the most likely cause here. However, it is very important to have considered the other options, in particular and to have ruled out a primary respiratory pathology or infection.

- In the anxious patient who is short of breath and persistently tachycardic have you thought of PE?

Question 5.

A 32 year-old man presents to the emergency department having been found collapsed by his girlfriend.

- pH: 7.25 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 11.1 (10–14)

- pCO2: 3.2 (4.5–6.0)

- HCO3: 11 (22-26)

- BE: -15 (-2 to +2)

- Potassium: 4.5

- Sodium: 135

- Chloride: 100

- Anion gap = ([Na + ] + [K + ]) − ([Cl − ] + [HCO 3 − ])

- Reference range usually 7–16 mEq/L (but varies between hospitals, some using 3-11)

- Anion gap = [Na + ] − ([Cl – ] + [HCO 3 − ])

What is the anion gap in this case?

- N.B. Some analysers won’t include potassium in their calculations therefore for them >15 constitutes a raised anion gap.

- Either way, this is a raised anion gap metabolic acidosis.

What is the differential diagnosis for a metabolic acidosis with raised anion gap? The traditional mnemonic for the causes of a metabolic acidosis with raised anion gap is ‘MUDPILES’:

- D iabetic ketoacidosis (and alcoholic/starvation ketoacidosis)

- P ropylene glycol

- E thylene glycol

- S alicylates

However, another way is to think about the mechanism of acidosis:

- DKA, lactic acidosis (produced by poorly perfused tissues)

- Methanol, ethanol, ethylene glycol

- Renal failure

[/toggle title="What is the differential diagnosis for a metabolic acidosis with normal or decreased anion gap?" active="false"]

- From the GI tract (diarrhoea or high-output stoma)

- From the kidneys ( renal tubular acidosis )

Question 6.

A 67 year-old man with a history of peptic ulcer disease presents with persistent vomiting.

- pH: 7.56 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 10.7 (10–14)

- pCO2: 5.0 (4.5–6.0)

- HCO3: 31 (22-26)

- BE: +5 (-2 to +2)

- This is metabolic alkalaemia

[/toggle title="What' s the differential diagnosis of this ABG picture?" active="false"]

Differential diagnosis of a metabolic alkalosis or alkalaemia:

- E.g. gastric outlet obstruction (the classic example is pyloric stenosis in a baby)

- Hyperaldosteronaemia

- Diuretic use

- Milk alkali syndrome

- Massive transfusion

Question 7.

A seventeen year-old girl presents to the emergency department after an argument with her boyfriend. He says that she took lots of tablets. She denies this. You persuade her to let you do an ABG:

- pH: 7.46 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 12.5 (10–14)

- BE: +1 (-2 to +2)

A few hours later she says she feels increasingly unwell and is complaining of ringing in her ears. A repeat gas shows:

- pH: 7.15 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 11.0 (10–14)

- HCO3: 9 (22-26)

- BE: -18 (-2 to +2)

- This is the classic picture of aspirin overdose.

- There is an initial respiratory alkalosis due to central respiratory centre stimulation causing increased respiratory drive.

- In the later stages a metabolic acidosis develops along side the respiratory alkalosis as a result of direct effect of the metabolite salicylic acid and more complex disruption of normal cellular metabolism.

How would you manage this patient?

How do you manage an aspirin overdose?

Presentation of aspirin overdose

- Hyperventilation

- Nausea & vomiting

- Epigastric pain

- ARDS (rare)

- Hypoglycaemia (children in particular)

Investigations in aspirin overdose

- Plasma salicylate concentration (initial and repeats)

- Paracetamol levels (always check in any case of poisoning by anything)

- Renal failure (rare) sometimes other electrolyte imbalances

- If dropping sats or any suspicion of ARDS (non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema)

Management of aspirin overdose

- ABCDE and supportive care

- Gastric lavage within 1h of ingestion (although no evidence for mortality reduction)

- Activated charcoal

- Correct electrolyte abnormalities

- Give 225ml of 8.4% bicarbonate solution over 1hr

- Bicarbonate will increase any pre-existing hypokalaemia – so don’t let it happen

- N.B. Acidosis increases salicylate transfer across the blood brain barrier

- Monitor U+Es regularly

- Haemodialysis

Prognosis in aspirin overdose

- Generally good with treatment.

Question 8.

A normally fit and well 11 year-old boy presents with diarrhoea and vomiting. He is complaining of non-specific abdominal pain. A venous blood gas shows :

- pH: 7.12 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 11.5 (10–14)

- BE: -17 (-2 to +2)

- Lactate: 4.0

- Potassium: 5.5

- Glucose: 22 mmol/L (395 mg/dL)

- This is diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) .

What are you going to do?

- Priorities for management include fluid resuscitation, insulin administration and careful management of potassium levels. Click here for a page detailing this, and click here for DKA questions

Question 9.

A 22 year-old lady with a known history of asthma presents to the emergency department with difficulty in breathing. Her initial ABG on 15 litres of oxygen shows:

- pH: 7.54 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 10.0 (10–14)

- HCO3: 24 (22-26)

- BE: +0 (-2 to +2)

After initial treatment the nurse in resus calls you to review the patient. The nurse says that although the patient’s respiratory rate has come down slightly she is looking more unwell. Her repeat gas shows:

- pO2: 9.8 (10–14)

- BE: -2 (-2 to +2)

- This patient has asthma, ongoing difficulty in breathing and a rising CO2 (the fact that it is in the normal range is irrelevant) .

- This is an extremely worrying sign as it shows that the patient is tiring.

- This patient should be managed in a high dependency area and closely monitored for further deterioration.

Question 10.

A 62 year-old woman with a history of diabetes and a long smoking history presents to the emergency department with worsening shortness of breath. On auscultation of the chest there are widespread crackles and you notice moderate ankle oedema. ABG shows:

- pH: 7.20 (7.35-7.45)

- pO2: 8.9 (10–14)

- pCO2: 6.3 (4.5–6.0)

- HCO3: 17 (22-26)

- BE: -8 (-2 to +2)

- Note that despite the low pH the pCO2 is also high.

- This is a picture of a mixed respiratory and metabolic acidosis.

- Given the history of diabetes and ankle swelling, renal failure is a unifying diagnosis with pulmonary oedema contributing to a respiratory acidosis whilst the failure to clear acids causes a metabolic acidosis.

Click here for further questions on ABGs

…and click here to learn the best way to interpret abgs.

Perfect revision for MRCP PACES, OSCES and medical student finals

- Off-Campus Access

- Find Resources

- Research Support

- Reserve Space

- --> X

- YouTube

- HSHSL Updates RSS Feed

- Connective Issues Newsletter

601 West Lombard Street Baltimore MD 21201-1512 Reference: 410-706-7996 Circulation: 410-706-7928

Evidence-Based Practice Tutorial: Asking Clinical Questions

- Asking Clinical Questions

- Acquiring the Evidence

- Appraising the Evidence

- Applying the Results

- Assessing the Outcome

- Practicing Evidence-Based Medicine

- Additional Resources

Using PICO to Create a Well-Built Clinical Question

It is important to be purposeful about creating a well-built clinical question so that you will be able to find the most relevant results possible. A well-built question will address four important items: P atient or Problem, I ntervention, C omparison, and O utcome. To help you remember this, you can use the mnemonic PICO. When you are designing your clinical question, here are some topics to take into consideration.

P= Patient or Problem:

How would you describe a group of patients similar to yours? What are the most important characteristics of the patient? This may include the primary problem, disease, or co-existing conditions. Sometimes the gender, age or race of a patient might be relevant to the diagnosis or treatment of a disease.

I= Intervention:

Which main intervention, prognostic factor, or exposure are you considering? What do you want to do for the patient? Prescribe a drug? Order a test? Order surgery? Or what factor may influence the prognosis of the patient - age, co-existing problems, or previous exposure?

C= Comparison:

What is the main alternative to compare with the intervention? Are you trying to decide between two drugs, a drug and no medication or placebo, or two diagnostic tests? Your clinical question may not always have a specific comparison.

O= Outcome:

What can you hope to accomplish, measure, improve or affect? What are you trying to do for the patient? Relieve or eliminate the symptoms? Reduce the number of adverse events? Improve function or test scores?

PICO Example

Using our clinical scenario, we will use PICO to develop a clinical question.

Question: In patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity, does bariatric surgery promote the management of diabetes and weight loss as compared to standard medical care?

Categories of Clinical Questions

Different types of clinical questions have certain kinds of studies that best answer them. The chart below lists the categories of clinical questions and the studies you should look for to answer them.

In our clinical scenario, we are want to determine whether or not bariatric surgery will benefit the patient, so this is a therapy question. As such, we will want to find randomized control trials to answer our question. If we found numerous RCTs on this topic, we might want to consider searching for a systematic review that synthesizes the results of these trials.

Hierarchy of Evidence

The strength of the evidence produced varies among the different types of studies. Filtered sources like systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide stronger evidence because they evaluate and compare a number of original studies. The image below demonstrates the relative strengths of the study types - generally, the higher up on the pyramid you go, the more rigorous the study design and the lesser likelihood of bias or systematic error.

Types of Studies

Types of studies we are going to cover all fall under one of two categories - primary sources or secondary sources. Primary sources are those that report original research and secondary sources are those that compile and evaluate original studies.

Primary Sources

Randomized Controlled Trials are studies in which subjects are randomly assigned to two or more groups; one group receives a particular treatment while the other receives an alternative treatment (or placebo). Patients and investigators are "blinded", that is, they do not know which patient has received which treatment. This is done in order to reduce bias.

Cohort Studies are cause-and-effect observational studies in which two or more populations are compared, often over time. These studies are not randomized.

Case Control Studies study a population of patients with a particular condition and compare it with a population that does not have the condition. It looks the exposures that those with the condition might have had that those in the other group did not.

Cross-Sectional Studies look at diseases and other factors at a particular point in time, instead of longitudinally. These are studies are descriptive only, not relational or causal. A particular type of cross-sectional study, called a Prospective, Blind Comparison to a Gold Standard, is a controlled trial that allows a research to compare a new test to the "gold standard" test to determine whether or not the new test will be useful.

Case Studies are usually single patient cases.

Secondary Sources

Systematic Reviews are studies in which the authors ask a specific clinical question, perform a comprehensive literature search, eliminate poorly done studies, and attempt to make practice recommendations based on the well-done studies.

Meta-Analyses are systematic reviews that combine the results of select studies into a single statistical analysis of the results.

Practice Guidelines are systematically developed statements used to assist practitioners and patients in making healthcare decisions.

- << Previous: Steps in the Evidence-Based Practice Process

- Next: Acquiring the Evidence >>

- Last Updated: Nov 22, 2022 3:19 PM

- URL: https://guides.hshsl.umaryland.edu/ebptutorial

Projects Maintained by the HSHSL

- Alumni & Associates

- Congenital Heart Disease

- Corporate Services

- Embracing mHealth

- Faith Community Nursing

- Project SHARE Curriculum

- Citizen Science: Gearing Up For Discovery (edX)

- UMB Digital Archive

- Weise Gallery

University of Maryland Schools

- School of Dentistry

- Graduate School

- School of Law

- School of Medicine

- School of Nursing

- School of Pharmacy

- School of Social Work

Connective Issues E-Newsletter

Read Our Latest Issue

Join our subscribers!

Contact Us | Hours | Directions | Privacy Policy | Disclaimers | Supporting the Library | Suggestion Box | HSHSL Building Work Order | Web Accessibility | Diversity Statement

601 W. Lombard Street | Baltimore, Maryland 21201-1512 | 410-706-7995

The Graduate Health & Life Sciences Research Library at Georgetown University Medical Center

Evidence-based medicine resource guide.

- Defining EBM

Types of Clinical Questions

Formulating a well built clinical question, type of clinical question and study design.

- Point-of-Care Tools

- Databases for Clinical Research

- Drug Information

- Books & eBooks

- EBM Journals

- EBM Organizations & Centers

- Health Sciences: The Research Process

Resources and Types of Clinical Question

Background questions are best answered by medical textbooks, point-of-care tools such as DynaMed Plus and Essential Evidence Plus, and narrative reviews.

Foreground questions are best answered by consulting medical databases such as MEDLINE (via PubMed or Ovid), Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and ACP Journal Club.

DML's Clinical Quick Reference page is a great place to locate EBM resources. Each resource has been labeled background and/or foreground, for you!

Clinical questions may be categorized as either background or foreground. Why is this important?

Determining the type of question will help you to select the best resource to consult for your answer.

Background questions ask for general knowledge about an illness, disease, condition, process or thing. These types of questions typically ask who, what, where, when, how & why about things like a disorder, test, or treatment, etc.

For example

- How overweight is a woman to be considered slightly obese?

- What are the clinical manifestations of menopause?

- What causes migraines?

Foreground questions ask for specific knowledge to inform clinical decisions. These questions typically concern a specific patient or particular population. Foreground questions tend to be more specific and complex compared to background questions. Quite often, foreground questions investigate comparisons, such as two drugs, two treatments, two diagnostic tests, etc. Foreground questions may be further categorized into one of 4 major types: treatment/therapy, diagnosis, prognosis, or etiology/harm.

- Is Crixivan effective when compared with placebo in slowing the rate of functional impairment in a 45 year old male patient with Lou Gehrig's Disease?

- In pediatric patients with Allergic Rhinitis, are Intranasal steroids more effective than antihistamines in the management of Allergic Rhinitis symptoms?

According to the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (CEBM) , "one of the fundamental skills required for practising EBM is the asking of well-built clinical questions. To benefit patients and clinicians, such questions need to be both directly relevant to patients' problems and phrased in ways that direct your search to relevant and precise answers."

A well-built clinical foreground question should have all four components. The PICO model is a helpful tool that assists you in organizing and focusing your foreground question into a searchable query. Dividing into the PICO elements helps identify search terms/concepts to use in your search of the literature.

P = Patient, Problem, Population (How would you describe a group of patients similar to you? What are the most important characteristics of the patient?)

I = Intervention, Prognostic Factor, Exposure (What main intervention are you considering? What do you want to do with this patient?)

C = Comparison (What are you hoping to compare with the intervention: another treatment, drug, placebo, a different diagnostic test, etc.? It's important to include this element and to be as specific as possible.)

O = Outcome (What are you trying to accomplish, measure, improve or affect? Outcomes may be disease-oriented or patient-oriented.)

Small collection. Updated monthly.

Two additional important elements of the well-built clinical question to consider are the type of foreground question and the type of study (methodology) . This information can be helpful in focusing the question and determining the most appropriate type of evidence.

Foreground questions can be further divided into questions that relate to therapy, diagnosis, prognosis, etiology/harm

- Therapy: Questions of treatment in order to achieve some outcome. May include drugs, surgical intervention, change in diet, counseling, etc.

- Diagnosis: Questions of identification of a disorder in a patient presenting with specific symptoms.

- Prognosis: Questions of progression of a disease or likelihood of a disease occurring.

- Etiology/Harm: Questions of negative impact from an intervention or other exposure.

Meta-analysis: A statistical technique that summarizes the results of several studies in a single weighted estimate, in which more weight is given to results of studies with more events and sometimes to studies of higher quality.

Systematic Review: a review in which specified and appropriate methods have been used to identify, appraise, and summarize studies addressing a defined question. (It can, but need not, involve meta-analysis). In Clinical Evidence, the term systematic review refers to a systematic review of RCTs unless specified otherwise.

Randomized Controlled Trial: a trial in which participants are randomly assigned to two or more groups: at least one (the experimental group) receiving an intervention that is being tested and another (the comparison or control group) receiving an alternative treatment or placebo. This design allows assessment of the relative effects of interventions.

Controlled Clinical Trial: a trial in which participants are assigned to two or more different treatment groups. In Clinical Evidence, we use the term to refer to controlled trials in which treatment is assigned by a method other than random allocation. When the method of allocation is by random selection, the study is referred to as a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Non-randomized controlled trials are more likely to suffer from bias than RCTs.

Cohort Study: a non-experimental study design that follows a group of people (a cohort), and then looks at how events differ among people within the group. A study that examines a cohort, which differs in respect to exposure to some suspected risk factor (e.g. smoking), is useful for trying to ascertain whether exposure is likely to cause specified events (e.g. lung cancer). Prospective cohort studies (which track participants forward in time) are more reliable than retrospective cohort studies.

Case control study: a study design that examines a group of people who have experienced an event (usually an adverse event) and a group of people who have not experienced the same event, and looks at how exposure to suspect (usually noxious) agents differed between the two groups. This type of study design is most useful for trying to ascertain the cause of rare events, such as rare cancers.

Case Series: analysis of series of people with the disease (there is no comparison group in case series).

- << Previous: Defining EBM

- Next: Point-of-Care Tools >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 8:45 AM

- URL: https://guides.dml.georgetown.edu/ebm

The Responsible Use of Electronic Resources policy governs the use of resources provided on these guides. © Dahlgren Memorial Library, Georgetown University Medical Center. Unless otherwise stated, these guides may be used for educational or academic purposes as long as proper attribution is given. Please seek permission for any modifications, adaptations, or for commercial purposes. Email [email protected] to request permission. Proper attribution includes: Written by or adapted from, Dahlgren Memorial Library, URL.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Case study: 33-year-old female presents with chronic sob and cough.

Sandeep Sharma ; Muhammad F. Hashmi ; Deepa Rawat .

Affiliations

Last Update: February 20, 2023 .

- Case Presentation

History of Present Illness: A 33-year-old white female presents after admission to the general medical/surgical hospital ward with a chief complaint of shortness of breath on exertion. She reports that she was seen for similar symptoms previously at her primary care physician’s office six months ago. At that time, she was diagnosed with acute bronchitis and treated with bronchodilators, empiric antibiotics, and a short course oral steroid taper. This management did not improve her symptoms, and she has gradually worsened over six months. She reports a 20-pound (9 kg) intentional weight loss over the past year. She denies camping, spelunking, or hunting activities. She denies any sick contacts. A brief review of systems is negative for fever, night sweats, palpitations, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, neural sensation changes, muscular changes, and increased bruising or bleeding. She admits a cough, shortness of breath, and shortness of breath on exertion.

Social History: Her tobacco use is 33 pack-years; however, she quit smoking shortly prior to the onset of symptoms, six months ago. She denies alcohol and illicit drug use. She is in a married, monogamous relationship and has three children aged 15 months to 5 years. She is employed in a cookie bakery. She has two pet doves. She traveled to Mexico for a one-week vacation one year ago.

Allergies: No known medicine, food, or environmental allergies.

Past Medical History: Hypertension

Past Surgical History: Cholecystectomy

Medications: Lisinopril 10 mg by mouth every day

Physical Exam:

Vitals: Temperature, 97.8 F; heart rate 88; respiratory rate, 22; blood pressure 130/86; body mass index, 28

General: She is well appearing but anxious, a pleasant female lying on a hospital stretcher. She is conversing freely, with respiratory distress causing her to stop mid-sentence.

Respiratory: She has diffuse rales and mild wheezing; tachypneic.

Cardiovascular: She has a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

Gastrointestinal: Bowel sounds X4. No bruits or pulsatile mass.

- Initial Evaluation

Laboratory Studies: Initial work-up from the emergency department revealed pancytopenia with a platelet count of 74,000 per mm3; hemoglobin, 8.3 g per and mild transaminase elevation, AST 90 and ALT 112. Blood cultures were drawn and currently negative for bacterial growth or Gram staining.

Chest X-ray

Impression: Mild interstitial pneumonitis

- Differential Diagnosis

- Aspiration pneumonitis and pneumonia

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Immunodeficiency state and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

- Carcinoid lung tumors

- Tuberculosis

- Viral pneumonia

- Chlamydial pneumonia

- Coccidioidomycosis and valley fever

- Recurrent Legionella pneumonia

- Mediastinal cysts

- Mediastinal lymphoma

- Recurrent mycoplasma infection

- Pancoast syndrome

- Pneumococcal infection

- Sarcoidosis

- Small cell lung cancer

- Aspergillosis

- Blastomycosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Actinomycosis

- Confirmatory Evaluation

CT of the chest was performed to further the pulmonary diagnosis; it showed a diffuse centrilobular micronodular pattern without focal consolidation.

On finding pulmonary consolidation on the CT of the chest, a pulmonary consultation was obtained. Further history was taken, which revealed that she has two pet doves. As this was her third day of broad-spectrum antibiotics for a bacterial infection and she was not getting better, it was decided to perform diagnostic bronchoscopy of the lungs with bronchoalveolar lavage to look for any atypical or rare infections and to rule out malignancy (Image 1).

Bronchoalveolar lavage returned with a fluid that was cloudy and muddy in appearance. There was no bleeding. Cytology showed Histoplasma capsulatum .

Based on the bronchoscopic findings, a diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent patient was made.

Pulmonary histoplasmosis in asymptomatic patients is self-resolving and requires no treatment. However, once symptoms develop, such as in our above patient, a decision to treat needs to be made. In mild, tolerable cases, no treatment other than close monitoring is necessary. However, once symptoms progress to moderate or severe, or if they are prolonged for greater than four weeks, treatment with itraconazole is indicated. The anticipated duration is 6 to 12 weeks total. The response should be monitored with a chest x-ray. Furthermore, observation for recurrence is necessary for several years following the diagnosis. If the illness is determined to be severe or does not respond to itraconazole, amphotericin B should be initiated for a minimum of 2 weeks, but up to 1 year. Cotreatment with methylprednisolone is indicated to improve pulmonary compliance and reduce inflammation, thus improving work of respiration. [1] [2] [3]

Histoplasmosis, also known as Darling disease, Ohio valley disease, reticuloendotheliosis, caver's disease, and spelunker's lung, is a disease caused by the dimorphic fungi Histoplasma capsulatum native to the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi River valleys of the United States. The two phases of Histoplasma are the mycelial phase and the yeast phase.

Etiology/Pathophysiology

Histoplasmosis is caused by inhaling the microconidia of Histoplasma spp. fungus into the lungs. The mycelial phase is present at ambient temperature in the environment, and upon exposure to 37 C, such as in a host’s lungs, it changes into budding yeast cells. This transition is an important determinant in the establishment of infection. Inhalation from soil is a major route of transmission leading to infection. Human-to-human transmission has not been reported. Infected individuals may harbor many yeast-forming colonies chronically, which remain viable for years after initial inoculation. The finding that individuals who have moved or traveled from endemic to non-endemic areas may exhibit a reactivated infection after many months to years supports this long-term viability. However, the precise mechanism of reactivation in chronic carriers remains unknown.

Infection ranges from an asymptomatic illness to a life-threatening disease, depending on the host’s immunological status, fungal inoculum size, and other factors. Histoplasma spp. have grown particularly well in organic matter enriched with bird or bat excrement, leading to the association that spelunking in bat-feces-rich caves increases the risk of infection. Likewise, ownership of pet birds increases the rate of inoculation. In our case, the patient did travel outside of Nebraska within the last year and owned two birds; these are her primary increased risk factors. [4]

Non-immunocompromised patients present with a self-limited respiratory infection. However, the infection in immunocompromised hosts disseminated histoplasmosis progresses very aggressively. Within a few days, histoplasmosis can reach a fatality rate of 100% if not treated aggressively and appropriately. Pulmonary histoplasmosis may progress to a systemic infection. Like its pulmonary counterpart, the disseminated infection is related to exposure to soil containing infectious yeast. The disseminated disease progresses more slowly in immunocompetent hosts compared to immunocompromised hosts. However, if the infection is not treated, fatality rates are similar. The pathophysiology for disseminated disease is that once inhaled, Histoplasma yeast are ingested by macrophages. The macrophages travel into the lymphatic system where the disease, if not contained, spreads to different organs in a linear fashion following the lymphatic system and ultimately into the systemic circulation. Once this occurs, a full spectrum of disease is possible. Inside the macrophage, this fungus is contained in a phagosome. It requires thiamine for continued development and growth and will consume systemic thiamine. In immunocompetent hosts, strong cellular immunity, including macrophages, epithelial, and lymphocytes, surround the yeast buds to keep infection localized. Eventually, it will become calcified as granulomatous tissue. In immunocompromised hosts, the organisms disseminate to the reticuloendothelial system, leading to progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. [5] [6]

Symptoms of infection typically begin to show within three to17 days. Immunocompetent individuals often have clinically silent manifestations with no apparent ill effects. The acute phase of infection presents as nonspecific respiratory symptoms, including cough and flu. A chest x-ray is read as normal in 40% to 70% of cases. Chronic infection can resemble tuberculosis with granulomatous changes or cavitation. The disseminated illness can lead to hepatosplenomegaly, adrenal enlargement, and lymphadenopathy. The infected sites usually calcify as they heal. Histoplasmosis is one of the most common causes of mediastinitis. Presentation of the disease may vary as any other organ in the body may be affected by the disseminated infection. [7]

The clinical presentation of the disease has a wide-spectrum presentation which makes diagnosis difficult. The mild pulmonary illness may appear as a flu-like illness. The severe form includes chronic pulmonary manifestation, which may occur in the presence of underlying lung disease. The disseminated form is characterized by the spread of the organism to extrapulmonary sites with proportional findings on imaging or laboratory studies. The Gold standard for establishing the diagnosis of histoplasmosis is through culturing the organism. However, diagnosis can be established by histological analysis of samples containing the organism taken from infected organs. It can be diagnosed by antigen detection in blood or urine, PCR, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The diagnosis also can be made by testing for antibodies again the fungus. [8]

Pulmonary histoplasmosis in asymptomatic patients is self-resolving and requires no treatment. However, once symptoms develop, such as in our above patient, a decision to treat needs to be made. In mild, tolerable cases, no treatment other than close monitoring is necessary. However, once symptoms progress to moderate or severe or if they are prolonged for greater than four weeks, treatment with itraconazole is indicated. The anticipated duration is 6 to 12 weeks. The patient's response should be monitored with a chest x-ray. Furthermore, observation for recurrence is necessary for several years following the diagnosis. If the illness is determined to be severe or does not respond to itraconazole, amphotericin B should be initiated for a minimum of 2 weeks, but up to 1 year. Cotreatment with methylprednisolone is indicated to improve pulmonary compliance and reduce inflammation, thus improving the work of respiration.

The disseminated disease requires similar systemic antifungal therapy to pulmonary infection. Additionally, procedural intervention may be necessary, depending on the site of dissemination, to include thoracentesis, pericardiocentesis, or abdominocentesis. Ocular involvement requires steroid treatment additions and necessitates ophthalmology consultation. In pericarditis patients, antifungals are contraindicated because the subsequent inflammatory reaction from therapy would worsen pericarditis.

Patients may necessitate intensive care unit placement dependent on their respiratory status, as they may pose a risk for rapid decompensation. Should this occur, respiratory support is necessary, including non-invasive BiPAP or invasive mechanical intubation. Surgical interventions are rarely warranted; however, bronchoscopy is useful as both a diagnostic measure to collect sputum samples from the lung and therapeutic to clear excess secretions from the alveoli. Patients are at risk for developing a coexistent bacterial infection, and appropriate antibiotics should be considered after 2 to 4 months of known infection if symptoms are still present. [9]

Prognosis

If not treated appropriately and in a timely fashion, the disease can be fatal, and complications will arise, such as recurrent pneumonia leading to respiratory failure, superior vena cava syndrome, fibrosing mediastinitis, pulmonary vessel obstruction leading to pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure, and progressive fibrosis of lymph nodes. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis usually has a good outcome on symptomatic therapy alone, with 90% of patients being asymptomatic. Disseminated histoplasmosis, if untreated, results in death within 2 to 24 months. Overall, there is a relapse rate of 50% in acute disseminated histoplasmosis. In chronic treatment, however, this relapse rate decreases to 10% to 20%. Death is imminent without treatment.

- Pearls of Wisdom

While illnesses such as pneumonia are more prevalent, it is important to keep in mind that more rare diseases are always possible. Keeping in mind that every infiltrates on a chest X-ray or chest CT is not guaranteed to be simple pneumonia. Key information to remember is that if the patient is not improving under optimal therapy for a condition, the working diagnosis is either wrong or the treatment modality chosen by the physician is wrong and should be adjusted. When this occurs, it is essential to collect a more detailed history and refer the patient for appropriate consultation with a pulmonologist or infectious disease specialist. Doing so, in this case, yielded workup with bronchoalveolar lavage and microscopic evaluation. Microscopy is invaluable for definitively diagnosing a pulmonary consolidation as exemplified here where the results showed small, budding, intracellular yeast in tissue sized 2 to 5 microns that were readily apparent on hematoxylin and eosin staining and minimal, normal flora bacterial growth.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

This case demonstrates how all interprofessional healthcare team members need to be involved in arriving at a correct diagnosis. Clinicians, specialists, nurses, pharmacists, laboratory technicians all bear responsibility for carrying out the duties pertaining to their particular discipline and sharing any findings with all team members. An incorrect diagnosis will almost inevitably lead to incorrect treatment, so coordinated activity, open communication, and empowerment to voice concerns are all part of the dynamic that needs to drive such cases so patients will attain the best possible outcomes.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Histoplasma Contributed by Sandeep Sharma, MD

Disclosure: Sandeep Sharma declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Muhammad Hashmi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Deepa Rawat declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Sharma S, Hashmi MF, Rawat D. Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough. [Updated 2023 Feb 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Palliative Chemotherapy: Does It Only Provide False Hope? The Role of Palliative Care in a Young Patient With Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Adenocarcinoma. [J Adv Pract Oncol. 2017] Review Palliative Chemotherapy: Does It Only Provide False Hope? The Role of Palliative Care in a Young Patient With Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Adenocarcinoma. Doverspike L, Kurtz S, Selvaggi K. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2017 May-Jun; 8(4):382-386. Epub 2017 May 1.

- Review Breathlessness with pulmonary metastases: a multimodal approach. [J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013] Review Breathlessness with pulmonary metastases: a multimodal approach. Brant JM. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013 Nov; 4(6):415-22.

- A 50-Year Old Woman With Recurrent Right-Sided Chest Pain. [Chest. 2022] A 50-Year Old Woman With Recurrent Right-Sided Chest Pain. Saha BK, Bonnier A, Chong WH, Chenna P. Chest. 2022 Feb; 161(2):e85-e89.

- Suicidal Ideation. [StatPearls. 2024] Suicidal Ideation. Harmer B, Lee S, Duong TVH, Saadabadi A. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Review Domperidone. [Drugs and Lactation Database (...] Review Domperidone. . Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

Recent Activity

- Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough - StatPearls Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Top 100 Ultrasound

Litfl 100+ ultrasound quiz.

Clinical cases and self assessment problems from the Ultrasound library to enhance interpretation skills through Ultrasound problems. Preparation for examinations.

Each case presents a clinical scenario; a series of questions; clinical images and finally some pearls to highlight the key learning points. We trust that you will find a few clinical pearls or reminders that you could apply to your patients that you care for in your emergency department or other health setting

Search by keywords; disease process; condition; eponym or clinical features…

LITFL Top 100 Self Assessment Quizzes

ULTRASOUND LIBRARY

POCUS, eFAST and basic principles

Privacy Overview

Medicine Cases Quiz

General level. Note that cases are simulated cases for learning purposes and not known patients. Just enter your name and enjoy the quiz.

A 70 years old man who has been smoking for 40 years was observed to be losing weight,having occasional seizures and coughing for 3 weeks. Three months to presentation he was noted during a clinic visit to be depressed and having memory impairment.Which is the most likely diagnosis?

Small cell Lung Cancer

Squamous Cell Cancer

Mesothelioma

Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Rate this question:

A 60 years old baker was diagnosed of a Primary Brain tumor. He was placed on oral dexamethasone 16 mg daily in divided dose by the managing Oncologist. The primary rationale for such action is

To reduce intracranial pressure from edema associated with the tumor

To aid the shrinking of tumor

To inhibit tumor markers produced by the tumor

To aid subsequent surgical resection of tumor

A 80 years old retired military man was diagnosed of glial tumor after recurrent episodes of seizures. Which is the most likely neuroimaging modality that was used?

Cranial MRI with gandolium contrast adminstration

Skull X-ray

Cranial MRI

Cranial CT scan

A patient presented to the hospital and was subsequently diagnosed of High grade glial malignant tumor. Which of the following is not likely to be a presenting feature?

Visual field deficit

Hemiparaesis

After extensive investigation a patient was diagnosed of Meningioma. Which is not likely to be presenting features when he presented to the hospital?

Quiz Review Timeline +

Our quizzes are rigorously reviewed, monitored and continuously updated by our expert board to maintain accuracy, relevance, and timeliness.

- Current Version

- Mar 21, 2023 Quiz Edited by ProProfs Editorial Team

- Dec 31, 2014 Quiz Created by Ceolado

Related Topics

- Health Care

- Herbal Medicine

Recent Quizzes

Featured Quizzes

Popular Topics

- Abdomen Quizzes

- Addiction Quizzes

- Aging Quizzes

- Arthritis Quizzes

- Beauty Quizzes

- Blood Quizzes

- Body Quizzes

- Bone Quizzes

- Brain Quizzes

- Child Health Quizzes

- Dermatology Quizzes

- Digestive System Quizzes

- Disease Quizzes

- Fertility Quizzes

- First Aid Quizzes

- Hair care Quizzes

- Health And Nutrition Quizzes

- Health And Wellness Quizzes

- Health Policy Quizzes

- Health Psychology Quizzes

- Health Worldwide Quizzes

- Hearing Quizzes

- Heart Quizzes

- Hospital Quizzes

- Illness Quizzes

- Injury Quizzes

- Kidney Quizzes

- Liver Quizzes

- Lung Quizzes

- Medical Quizzes

- Mental Health Quizzes

- Nose Quizzes

- Nutrition Quizzes

- Obesity Quizzes

- Ophthalmology Quizzes

- Patient Quizzes

- Patient care Quizzes

- Pharmacy Quizzes

- Pregnancy Quizzes

- Puberty Quizzes

- Public Health Quizzes

- Respiratory System Quizzes

- Sleep Quizzes

- Stress Quizzes

- Surgery Quizzes

- Surgical Instruments Quizzes

- Throat Quizzes

- Weight Quizzes

- Wellness Quizzes

Related Quizzes

Wait! Here's an interesting quiz for you.

- ACS Foundation

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- ACS Archives

- Careers at ACS

- Federal Legislation

- State Legislation

- Regulatory Issues

- Get Involved

- SurgeonsPAC

- About ACS Quality Programs

- Accreditation & Verification Programs

- Data & Registries

- Standards & Staging

- Membership & Community

- Practice Management

- Professional Growth

- News & Publications

- Information for Patients and Family

- Preparing for Your Surgery

- Recovering from Your Surgery

- Jobs for Surgeons

- Become a Member

- Media Center

Our top priority is providing value to members. Your Member Services team is here to ensure you maximize your ACS member benefits, participate in College activities, and engage with your ACS colleagues. It's all here.

- Membership Benefits

- Find a Surgeon

- Find a Hospital or Facility

- Quality Programs

- Education Programs

- Member Benefits

- April 2024 | Volume 109, I...

- Understanding Surgical CPT...

Understanding Surgical CPT Coding Essentials Will Help Ensure Proper Reimbursement

Megan McNally, MD, FACS, Jayme Lieberman, MD, FACS, and Jan Nagle, MS

April 10, 2024

Numerous Current Procedural Terminology (CPT)* coding questions raised during ACS coding courses and received via the ACS Coding Hotline underscore the need to explain key coding concepts in order to ensure accurate coding.

This article examines crucial coding concepts through fictional cases that should be familiar to general surgeons and related surgical specialties.

Laparoscopic Liver Biopsy

Case: While performing a laparoscopic appendectomy for appendiceal carcinoma, the surgeon also performs a liver biopsy of a suspicious lesion. Reportable codes include the following: 44970, Laparoscopy, surgical, appendectomy, and 47379, Unlisted laparoscopic procedure, liver.

Concept: It would not be appropriate to report add-on code 47001, Biopsy of liver, needle; when done for indicated purpose at time of other major procedure (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure), for the biopsy procedure. The intent of code 47001 has always been for a liver biopsy at the time of an open procedure as discussed in the AMA CPT Assistant 1992 Code Update (Winter 1991) after code 47001 was established. Additional CPT Assistant articles have reinforced that 47001 may only be reported for a liver biopsy via an open approach. Therefore, code 47379 should be reported when a liver biopsy is performed via a laparoscopic approach in addition to a laparoscopic primary procedure and add-on code 47001 should be used as a “proxy” for charges. This information supersedes guidance that was provided in the October 2018 ACS Bulletin column “CPT Coding for Hepatobiliary Surgery.”

Case: A patient with hepatocellular carcinoma underwent an exploratory laparoscopy to obtain a liver biopsy and assess the peritoneal cavity to exclude advance disease. The reportable code is 47379, Unlisted laparoscopic procedure, liver.

Concept: It would not be appropriate to report 49321, Laparoscopy, surgical; with biopsy (single or multiple) if the biopsy is the only laparoscopic procedure performed as this code is in the Abdomen, Peritoneum, and Omentum subsection of CPT and not the Liver subsection. For this clinical scenario, code 47379 should be reported and code 49321 should be used as a “proxy” for charges. This information supersedes guidance that was provided in the October 2018 ACS Bulletin column “CPT Coding for Hepatobiliary Surgery.”

Laparoscopic Appendectomy for Perforation

Case: A patient undergoes a laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis requiring significantly more work than a typical laparoscopic appendectomy. The reportable code is 44970, Laparoscopy, surgical, appendectomy.

Concept: Although there are separate codes to differentiate an open appendectomy without rupture (44950) and with rupture (44960), there is only one code for a laparoscopic appendectomy (44970), and it is used to report a laparoscopic appendectomy for either scenario; with rupture or without rupture. It would not be correct to report 44979, Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix for a laparoscopic appendectomy for perforation with abscess and peritonitis and use the open code 44960, Appendectomy; for ruptured appendix with abscess or generalized peritonitis as a “proxy” for charges. However, depending on the amount of extra time and/or work effort required when compared to a laparoscopic appendectomy without rupture, it may be appropriate to append modifier 22, Increased procedural services. Documentation must support the substantial additional work and the reason for the additional work (i.e., increased intensity, time, technical difficulty of procedure, severity of patient’s condition, physical and mental effort required).

Adjacent Tissue Transfer after Breast Surgery

Case: Immediately following a lumpectomy, the surgeon performs reconstructive tissue rearrangement including dissection through the breast parenchyma in order to create a pedicled flap of breast tissue that is then transposed into the defect to improve the contour of the breast. Reportable codes include the following: 19301, Mastectomy, partial (e.g., lumpectomy, tylectomy, quadrantectomy, segmentectomy) and code(s) for adjacent tissue transfer as appropriate (14000-14041, 14301-14302).

Concept: Reporting adjacent tissue transfer for immediate, partial breast reconstruction following lumpectomy is possible, although it requires the specific criteria for reporting adjacent tissue transfer. In addition to a description of the defect, it requires full documentation of the incisions required to create the pedicled flap of breast tissue, preservation of vascularity, the dimensions of the tissue mobilized, and the technique for transfer of the tissue into the defect. Undermining of the breast tissue off the pectoralis major muscle alone or undermining tissue within the breast parenchyma to advance tissue for primary repair is not considered adjacent tissue transfer and is bundled with the partial mastectomy code and not separately reportable.

Endocrine Surgery

Ca se: A patient underwent a right thyroid lobectomy years ago. It is now necessary to go back and remove the rest of the right lobe and also remove the left lobe (previously untouched). Reportable codes include the following: 60260-RT, Thyroidectomy, removal of all remaining thyroid tissue following previous removal of a portion of thyroid, and 60220-LT-59, Total thyroid lobectomy, unilateral; with or without isthmusectomy.

Concept: This reporting is based on the fact that 60260 is considered a bilateral procedure and since the left lobe was previously untouched, it would be incorrect to report a code for removal of remaining tissue when a total lobectomy is performed.

Case: A patient had a left lobectomy on March 1. On March 14, the patient is taken back to surgery by the same surgeon for a right thyroid lobectomy after pathology showed a malignancy in the right thyroid lobe. Reportable code for the first operation: 60220-LT, Total thyroid lobectomy, unilateral; with or without isthmusectomy. Reportable code for the subsequent operation: 60220-RT-58.

Concept: Modifier 58 is appended to the second operation because it was a “staged or related procedure or service by the same physician or other qualified healthcare professional during the postoperative period.”

The ACS collaborates with KZA, Inc. on courses that provide the tools necessary to increase revenue and decrease compliance risk. These courses are an opportunity to sharpen your coding skills. You also will be provided online access to the KZA alumni website, where you will find additional resources and other FAQs about correct coding. Information about the courses can be accessed on the KZA website .

In addition, as part of the College’s ongoing efforts to help members and their practices submit clean claims and receive proper reimbursement, a coding consultation service—the ACS Coding Hotline—has been established for coding and billing questions. ACS members are offered five free consultation units (CUs) per calendar year. One CU is a period of up to 10 minutes of coding services time. Access the ACS Coding Hotline website today .

Dr. Megan McNally is a surgical oncologist at Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Missouri, and assistant clinical professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine. She also is a member of the ACS General Surgery Coding and Reimbursement Committee and an ACS advisor to the AMA CPT Editorial Panel.

*All specific references to CPT codes and descriptions are ©2023 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association.

Related Pages

ACS Cancer Conference Highlights Quality Efforts, Current Complexities in Cancer Care

Sessions highlighted new information on standards and data collection, and offered insights into the new pediatric accreditation standards.

Trauma Meeting Spotlights New Image-Focused STOP THE BLEED Course

A Special Session at the COT Annual Meeting provided an overview of the new version of the STOP THE BLEED course.

ACS Statement Guides Surgeons in Telehealth Practices

The ACS Board of Regents approved a new policy statement on telehealth at its February 2023 meeting.

JACS Highlights

Read capsule summaries of articles appearing in the April 2024 issue of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Engineering Surgical Innovation Is a Joint Effort

The Annual Surgeons and Engineers meeting hosted its first DIY simulator/model competition and provided a platform for innovative collaboration.

In Memoriam: Dr. Edward (Ted) Copeland, ACS Past-President

Renowned breast cancer surgeon and ACS Past-President Dr. Edward Copeland passed away March 31, 2024, at the age of 86.

Member News April 2024

Learn more about ACS members who have been recognized for noteworthy achievements.

ACS’s Advocacy Achievements

Dr. Turner addresses the importance of surgeon advocacy and details some recent successes.

Are Antibiotics the Answer to Treating Appendicitis?

Discover new perspectives on operative versus nonoperative approaches to managing uncomplicated acute appendicitis.

For Optimal Outcomes, Surgeons Should Tap into “Collective Surgical Consciousness”

Learn about the role of AI in medical imaging and its potential impact on patient decision-making.

New Technologies, Approaches Help Surgeons Maximize the Use of Transplant Organs

Read about innovative advancements that help recover, preserve, and rehabilitate donor organs in an effort to streamline the allocation process.

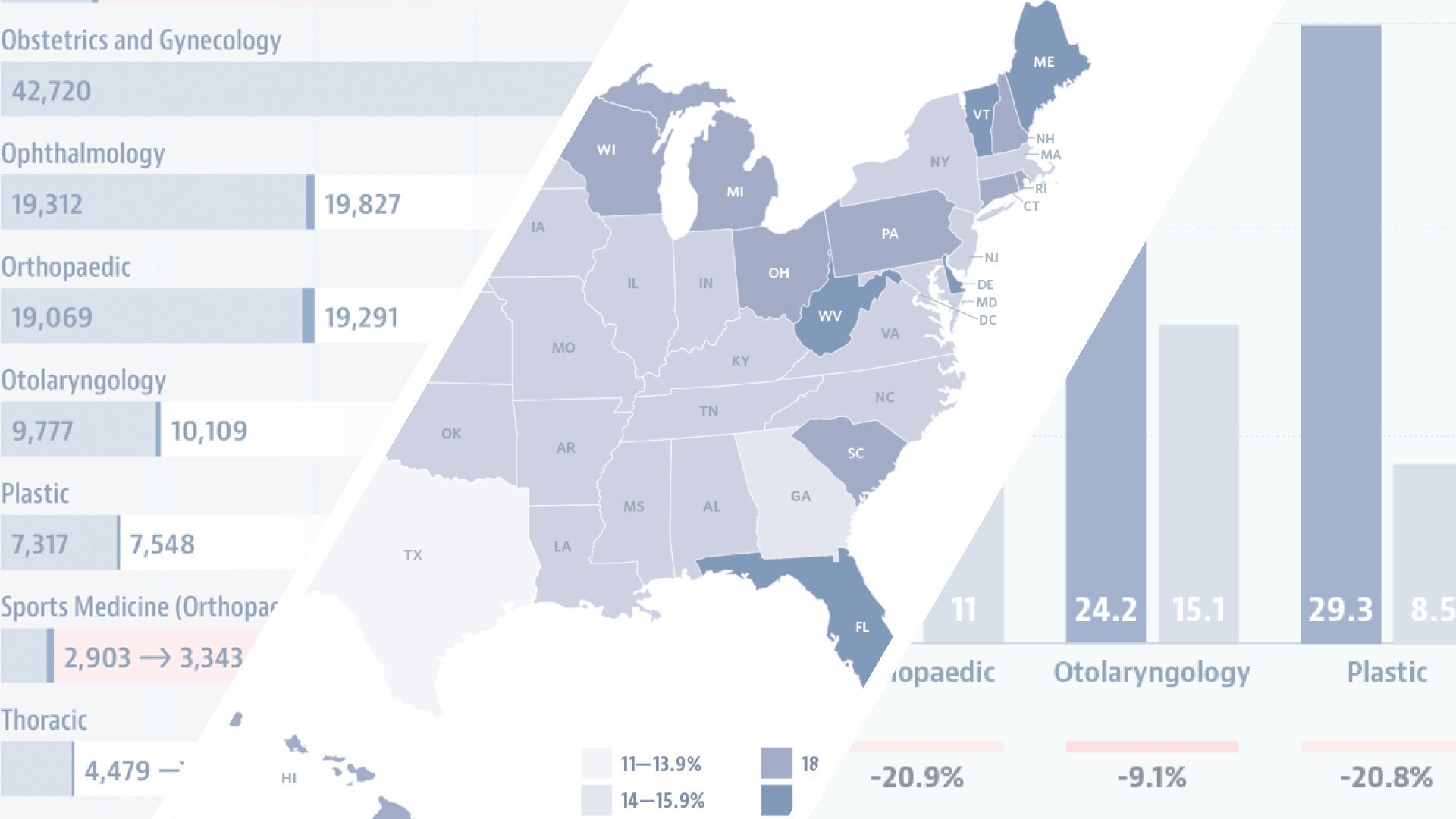

Physician Workforce Data Suggest Epochal Change

Gain new perspectives on current and future surgeon workforce supply culled from the AAMC’s US Physician Workforce Data Dashboard.

Artificial Intelligence: The Future Is Now

Surgeons are encouraged to take an active role in the adoption of AI to ensure the quality of care and safety of our patients.

Artificial Intelligence: The Future Is What We Make It

Members of the ACS Health Information Technology Committee respond to Dr. James Elsey's insights on AI in healthcare.

FDA Authorizes COVID Drug Pemgarda for High-Risk Patients

BY CARRIE MACMILLAN April 5, 2024

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted an emergency use authorization (EUA) to a medicine meant to protect certain immunocompromised people against COVID-19 .

The medicine, pemivibart (brand name Pemgarda™), is for people who are at least 12 years of age, weigh more than 88 pounds, and are moderately to severely immunocompromised.

An EUA is a tool the FDA uses to expedite the availability of drugs, vaccines , and other products during a public health emergency. While the public health emergency for COVID officially expired in May 2023, the FDA can still issue EUAs related to it.

“This medication provides important protection for the immunocompromised, a population that is more likely to have serious COVID illness and a higher mortality rate,” says Scott Roberts, MD , a Yale Medicine infectious diseases specialist.

Being immunocompromised means your immune system doesn’t work as well as it should to protect against infection because of a medical condition, such as cancer , that weakens immune function or because you receive medicines or treatments, such as immunotherapy , that suppress the immune system.

“The population identified as moderately to severely immunocompromised includes solid organ transplant recipients, stem cell transplant recipients, and those who are on chemotherapy for cancers such as lymphoma and leukemia, among many others,” Dr. Roberts explains. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides a more detailed list .) Approximately 3% of adults in the United States are immunocompromised.

“This group is also less likely to build enough protection against COVID after vaccination. For these patients, the pandemic is not over,” says Dr. Roberts. “Hopefully, this new treatment will help the vulnerable feel safer.”

Below, we talk more about Pemgarda with Dr. Roberts.

Why isn’t COVID vaccination as effective in immunocompromised individuals?

Those who are not immunocompromised most likely have a strong mix of “hybrid” immunity to COVID at this point, both from vaccination and natural infection, Dr. Roberts explains.

“Most people should not be concerned when a new COVID variant arises because even if it bypasses some of their protection, it's not going to bypass all of it,” Dr. Roberts says. “But some immunocompromised people do not have that luxury. Any COVID infection is going to hit them the hardest. And vaccination is still the best tool we have to offer for the prevention of severe COVID.”

However, this drug is a new tool that can help immunocompromised patients feel safe going about daily activities as many other people do at this phase of the pandemic, he adds.

How does Pemgarda work?

Pemgarda is a type of medicine called pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which is taken to prevent COVID infection. Anyone with COVID—or who has a known recent exposure to someone with a COVID infection—cannot take Pemgarda.

Paxlovid and Remdesivir, conversely, are meant to be taken after a known COVID infection and are for anyone deemed high-risk for serious illness, including those who are immunocompromised.

Pemgarda is a type of monoclonal antibody (mAb), a drug therapy that uses antibodies made in a laboratory. These antibodies attach to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and prevent the virus from entering the body’s cells.

“Despite vaccination, many immunocompromised patients are still unable to generate the antibodies necessary to block this entry; Pemgarda serves as a tool to increase SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies to levels seen in nonimmunocompromised individuals after vaccination,” says Dr. Roberts.

It is given as an infusion in a medical setting and takes about an hour to complete. Patients can get a dose of the medication as often as every three months.

Is this the first preventive drug for COVID?

A previous mAb treatment, Evusheld™, was authorized by the FDA in 2021 to prevent COVID in immunocompromised patients. However, the medication proved ineffective against newer COVID variants and was taken off the market in January 2023.

Pemgarda is the only COVID PrEP drug on the market.

How effective is Pemgarda against COVID?

Pemgarda was granted an EUA based on data from an ongoing Phase 3 CANOPY clinical trial, as well as efficacy data from previous clinical trials of adintrevimab, the parent mAb for pemivibart, and other monoclonal antibody products.

In trials, adintrevimab was associated with an approximate 70% risk reduction of developing symptomatic COVID-19 compared to a placebo, according to Invivyd , the company that makes the drug. The CANOPY studies were done when the JN.1 subvariant was circulating. JN.1 is still the predominant coronavirus subvariant.

Is Pemgarda safe?