- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

Neal Haddaway

October 19th, 2020, 8 common problems with literature reviews and how to fix them.

3 comments | 314 shares

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

Literature reviews are an integral part of the process and communication of scientific research. Whilst systematic reviews have become regarded as the highest standard of evidence synthesis, many literature reviews fall short of these standards and may end up presenting biased or incorrect conclusions. In this post, Neal Haddaway highlights 8 common problems with literature review methods, provides examples for each and provides practical solutions for ways to mitigate them.

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

Researchers regularly review the literature – it’s an integral part of day-to-day research: finding relevant research, reading and digesting the main findings, summarising across papers, and making conclusions about the evidence base as a whole. However, there is a fundamental difference between brief, narrative approaches to summarising a selection of studies and attempting to reliably and comprehensively summarise an evidence base to support decision-making in policy and practice.

So-called ‘evidence-informed decision-making’ (EIDM) relies on rigorous systematic approaches to synthesising the evidence. Systematic review has become the highest standard of evidence synthesis and is well established in the pipeline from research to practice in the field of health . Systematic reviews must include a suite of specifically designed methods for the conduct and reporting of all synthesis activities (planning, searching, screening, appraising, extracting data, qualitative/quantitative/mixed methods synthesis, writing; e.g. see the Cochrane Handbook ). The method has been widely adapted into other fields, including environment (the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence ) and social policy (the Campbell Collaboration ).

Despite the growing interest in systematic reviews, traditional approaches to reviewing the literature continue to persist in contemporary publications across disciplines. These reviews, some of which are incorrectly referred to as ‘systematic’ reviews, may be susceptible to bias and as a result, may end up providing incorrect conclusions. This is of particular concern when reviews address key policy- and practice- relevant questions, such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic or climate change.

These limitations with traditional literature review approaches could be improved relatively easily with a few key procedures; some of them not prohibitively costly in terms of skill, time or resources.

In our recent paper in Nature Ecology and Evolution , we highlight 8 common problems with traditional literature review methods, provide examples for each from the field of environmental management and ecology, and provide practical solutions for ways to mitigate them.

There is a lack of awareness and appreciation of the methods needed to ensure systematic reviews are as free from bias and as reliable as possible: demonstrated by recent, flawed, high-profile reviews. We call on review authors to conduct more rigorous reviews, on editors and peer-reviewers to gate-keep more strictly, and the community of methodologists to better support the broader research community. Only by working together can we build and maintain a strong system of rigorous, evidence-informed decision-making in conservation and environmental management.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below

Image credit: Jaeyoung Geoffrey Kang via unsplash

About the author

Neal Haddaway is a Senior Research Fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute, a Humboldt Research Fellow at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, and a Research Associate at the Africa Centre for Evidence. He researches evidence synthesis methodology and conducts systematic reviews and maps in the field of sustainability and environmental science. His main research interests focus on improving the transparency, efficiency and reliability of evidence synthesis as a methodology and supporting evidence synthesis in resource constrained contexts. He co-founded and coordinates the Evidence Synthesis Hackathon (www.eshackathon.org) and is the leader of the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence centre at SEI. @nealhaddaway

Why is mission creep a problem and not a legitimate response to an unexpected finding in the literature? Surely the crucial points are that the review’s scope is stated clearly and implemented rigorously, not when the scope was finalised.

- Pingback: Quick, but not dirty – Can rapid evidence reviews reliably inform policy? | Impact of Social Sciences

#9. Most of them are terribly boring. Which is why I teach students how to make them engaging…and useful.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Related Posts

“But I’m not ready!” Common barriers to writing and how to overcome them

November 16th, 2020.

“Remember a condition of academic writing is that we expose ourselves to critique” – 15 steps to revising journal articles

January 18th, 2017.

A simple guide to ethical co-authorship

March 29th, 2021.

How common is academic plagiarism?

February 8th, 2024.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

Eight problems with literature reviews and how to fix them

Affiliations.

- 1 Mercator Research Institute on Climate Change and Global Commons, Berlin, Germany. [email protected].

- 2 Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. [email protected].

- 3 Africa Centre for Evidence, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. [email protected].

- 4 College of Medicine and Health, Exeter University, Exeter, UK.

- 5 Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

- 6 School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK.

- 7 Department of Biological Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, UK.

- 8 Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

- 9 Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

- 10 Collaboration for Environmental Evidence, UK Centre, School of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, UK.

- 11 Liljus ltd, London, UK.

- 12 Department of Forest Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

- 13 Evidence Synthesis Lab, School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, University of Newcastle, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK.

- PMID: 33046871

- DOI: 10.1038/s41559-020-01295-x

Traditional approaches to reviewing literature may be susceptible to bias and result in incorrect decisions. This is of particular concern when reviews address policy- and practice-relevant questions. Systematic reviews have been introduced as a more rigorous approach to synthesizing evidence across studies; they rely on a suite of evidence-based methods aimed at maximizing rigour and minimizing susceptibility to bias. Despite the increasing popularity of systematic reviews in the environmental field, evidence synthesis methods continue to be poorly applied in practice, resulting in the publication of syntheses that are highly susceptible to bias. Recognizing the constraints that researchers can sometimes feel when attempting to plan, conduct and publish rigorous and comprehensive evidence syntheses, we aim here to identify major pitfalls in the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews, making use of recent examples from across the field. Adopting a 'critical friend' role in supporting would-be systematic reviews and avoiding individual responses to police use of the 'systematic review' label, we go on to identify methodological solutions to mitigate these pitfalls. We then highlight existing support available to avoid these issues and call on the entire community, including systematic review specialists, to work towards better evidence syntheses for better evidence and better decisions.

- Environment

- Research Design

- Systematic Reviews as Topic*

Eight common problems with science literature reviews and how to fix them

Research Fellow, Africa Centre for Evidence, University of Johannesburg

Disclosure statement

Neal Robert Haddaway works for the Stockholm Environment Institute and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change. He receives funding from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Mistra, Formas, and Vinnova. He is also an honorary Research Associate at the Africa Centre for Evidence at the University of Johannesburg.

University of Johannesburg provides support as an endorsing partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Researchers regularly review the literature that’s generated by others in their field. This is an integral part of day-to-day research: finding relevant research, reading and digesting the main findings, summarising across papers, and making conclusions about the evidence base as a whole.

However, there is a fundamental difference between brief, narrative approaches to summarising a selection of studies and attempting to reliably, comprehensively summarise an evidence base to support decision-making in policy and practice.

So-called “evidence-informed decision-making” relies on rigorous systematic approaches to synthesising the evidence. Systematic review has become the highest standard of evidence synthesis. It is well established in the pipeline from research to practice in several fields including health , the environment and social policy . Rigorous systematic reviews are vital for decision-making because they help to provide the strongest evidence that a policy is likely to work (or not). They also help to avoid expensive or dangerous mistakes in the choice of policies.

But systematic review has not yet entirely replaced traditional methods of literature review. These traditional reviews may be susceptible to bias and so may end up providing incorrect conclusions. This is especially worrying when reviews address key policy and practice questions.

The good news is that the limitations of traditional literature review approaches could be improved relatively easily with a few key procedures. Some of these are not prohibitively costly in terms of skill, time or resources. That’s particularly important in African contexts, where resource constraints are a daily reality, but should not compromise the continent’s need for rigorous, systematic and transparent evidence to inform policy.

In our recent paper in Nature Ecology and Evolution , we highlighted eight common problems with traditional literature review methods. We gave examples for each problem, drawing from the field of environmental management and ecology. Finally, we outlined practical solutions.

These are the eight problems we identified in our paper .

First, traditional literature reviews can lack relevance. This is because limited stakeholder engagement can lead to a review that is of limited practical use to decision-makers.

Second, reviews that don’t publish their methods in an a priori (meaning that it is published before the review work begins) protocol may suffer from mission creep. In our paper we give the example of a 2019 review that initially stated it was looking at all population trends among insects. Instead, it ended up focusing only on studies that showed insect population declines. This could have been prevented by publishing and sticking to methods outlined in a protocol.

Third, a lack of transparency and replicability in the review methods may mean that the review cannot be replicated . Replicability is a central tenet of the scientific method.

Selection bias is another common problem. Here, the studies that are included in a literature review are not representative of the evidence base. A lack of comprehensiveness, stemming from an inappropriate search method, can also mean that reviews end up with the wrong evidence for the question at hand.

Traditional reviews may also exclude grey literature . This is defined as any document

produced on all levels of government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats, but which is not controlled by commercial publishers, i.e., where publishing is not the primary activity of the producing body.

It includes organisational reports and unpublished theses or other studies . Traditional reviews may also fail to test for evidence of publication bias; both these issues can result in incorrect or misleading conclusions. Another common error is to treat all evidence as equally valid. The reality is that some research studies are more valid than others. This needs to be accounted for in the synthesis.

Inappropriate synthesis is another common issue. This involves methods like vote-counting, which refers to tallying studies based on their statistical significance. Finally, a lack of consistency and error checking (as would happen when a reviewer works alone) can introduce errors and biases if a single reviewer makes decisions without consensus .

All of these common problems can be solved, though. Here’s how.

Stakeholders can be identified, mapped and contacted for feedback and inclusion without the need for extensive budgets. Best-practice guidelines for this process already exist .

Researchers can carefully design and publish an a priori protocol that outlines planned methods for searching, screening, data extraction, critical appraisal and synthesis in detail. Organisations like the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence have existing protocols from which people can draw.

Researchers also need to be explicit and use high-quality guidance and standards for review conduct and reporting . Several such standards already exist .

Another useful approach is to carefully design a search strategy with an info specialist; to trial the search strategy against a benchmark list; and to use multiple bibliographic databases, languages and sources of grey literature. Researchers should then publish their search methods in an a priori protocol for peer review.

Researchers should consider carefully planning and trialling a critical appraisal tool before starting the process in full, learning from existing robust critical appraisal tools . Critical appraisal is the carefully planned assessment of all possible risks of bias and possible confounders in a research study. Researchers should select their synthesis method carefully, based on the data analysed. Vote-counting should never be used instead of meta-analysis. Formal methods for narrative synthesis should be used to summarise and describe the evidence base.

Finally, at least two reviewers should screen a subset of the evidence base to ensure consistency and shared understanding of the methods before proceeding. Ideally, reviewers should conduct all decisions separately and then consolidate.

Collaboration

Collaboration is crucial to address the problems with traditional review processes. Authors need to conduct more rigorous reviews. Editors and peer reviewers need to gate-keep more strictly. The community of methodologists needs to better support the broader research community.

Working together, the academic and research community can build and maintain a strong system of rigorous, evidence-informed decision-making in conservation and environmental management – and, ultimately, in other disciplines.

- Systematic reviews

- Evidence based policy

- Academic research

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 12 October 2020

Eight problems with literature reviews and how to fix them

- Neal R. Haddaway ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3902-2234 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Alison Bethel 4 ,

- Lynn V. Dicks 5 , 6 ,

- Julia Koricheva ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9033-0171 7 ,

- Biljana Macura ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4253-1390 2 ,

- Gillian Petrokofsky 8 ,

- Andrew S. Pullin 9 ,

- Sini Savilaakso ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8514-8105 10 , 11 &

- Gavin B. Stewart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5684-1544 12

Nature Ecology & Evolution volume 4 , pages 1582–1589 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

82 Citations

387 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Conservation biology

- Environmental impact

An Author Correction to this article was published on 19 October 2020

This article has been updated

Traditional approaches to reviewing literature may be susceptible to bias and result in incorrect decisions. This is of particular concern when reviews address policy- and practice-relevant questions. Systematic reviews have been introduced as a more rigorous approach to synthesizing evidence across studies; they rely on a suite of evidence-based methods aimed at maximizing rigour and minimizing susceptibility to bias. Despite the increasing popularity of systematic reviews in the environmental field, evidence synthesis methods continue to be poorly applied in practice, resulting in the publication of syntheses that are highly susceptible to bias. Recognizing the constraints that researchers can sometimes feel when attempting to plan, conduct and publish rigorous and comprehensive evidence syntheses, we aim here to identify major pitfalls in the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews, making use of recent examples from across the field. Adopting a ‘critical friend’ role in supporting would-be systematic reviews and avoiding individual responses to police use of the ‘systematic review’ label, we go on to identify methodological solutions to mitigate these pitfalls. We then highlight existing support available to avoid these issues and call on the entire community, including systematic review specialists, to work towards better evidence syntheses for better evidence and better decisions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

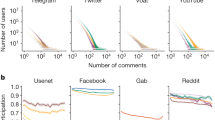

Persistent interaction patterns across social media platforms and over time

Michele Avalle, Niccolò Di Marco, … Walter Quattrociocchi

An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success

Reed T. Sutton, David Pincock, … Karen I. Kroeker

Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research

Lisa Messeri & M. J. Crockett

Change history

19 october 2020.

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Grant, M. J. & Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr. J. 26 , 91–108 (2009).

PubMed Google Scholar

Haddaway, N. R. & Macura, B. The role of reporting standards in producing robust literature reviews. Nat. Clim. Change 8 , 444–447 (2018).

Google Scholar

Pullin, A. S. & Knight, T. M. Science informing policy–a health warning for the environment. Environ. Evid. 1 , 15 (2012).

Haddaway, N., Woodcock, P., Macura, B. & Collins, A. Making literature reviews more reliable through application of lessons from systematic reviews. Conserv. Biol. 29 , 1596–1605 (2015).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pullin, A., Frampton, G., Livoreil, B. & Petrokofsky, G. Guidelines and Standards for Evidence Synthesis in Environmental Management (Collaboration for Environmental Evidence, 2018).

White, H. The twenty-first century experimenting society: the four waves of the evidence revolution. Palgrave Commun. 5 , 47 (2019).

O’Leary, B. C. et al. The reliability of evidence review methodology in environmental science and conservation. Environ. Sci. Policy 64 , 75–82 (2016).

Woodcock, P., Pullin, A. S. & Kaiser, M. J. Evaluating and improving the reliability of evidence syntheses in conservation and environmental science: a methodology. Biol. Conserv. 176 , 54–62 (2014).

Campbell Systematic Reviews: Policies and Guidelines (Campbell Collaboration, 2014).

Higgins, J. P. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (John Wiley & Sons, 2019).

Shea, B. J. et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 358 , j4008 (2017).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Haddaway, N. R., Land, M. & Macura, B. “A little learning is a dangerous thing”: a call for better understanding of the term ‘systematic review’. Environ. Int. 99 , 356–360 (2017).

Freeman, R. E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

Haddaway, N. R. et al. A framework for stakeholder engagement during systematic reviews and maps in environmental management. Environ. Evid. 6 , 11 (2017).

Land, M., Macura, B., Bernes, C. & Johansson, S. A five-step approach for stakeholder engagement in prioritisation and planning of environmental evidence syntheses. Environ. Evid. 6 , 25 (2017).

Oliver, S. & Dickson, K. Policy-relevant systematic reviews to strengthen health systems: models and mechanisms to support their production. Evid. Policy 12 , 235–259 (2016).

Savilaakso, S. et al. Systematic review of effects on biodiversity from oil palm production. Environ. Evid. 3 , 4 (2014).

Savilaakso, S., Laumonier, Y., Guariguata, M. R. & Nasi, R. Does production of oil palm, soybean, or jatropha change biodiversity and ecosystem functions in tropical forests. Environ. Evid. 2 , 17 (2013).

Haddaway, N. R. & Crowe, S. Experiences and lessons in stakeholder engagement in environmental evidence synthesis: a truly special series. Environ. Evid. 7 , 11 (2018).

Sánchez-Bayo, F. & Wyckhuys, K. A. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: a review of its drivers. Biol. Conserv. 232 , 8–27 (2019).

Agarwala, M. & Ginsberg, J. R. Untangling outcomes of de jure and de facto community-based management of natural resources. Conserv. Biol. 31 , 1232–1246 (2017).

Gurevitch, J., Curtis, P. S. & Jones, M. H. Meta-analysis in ecology. Adv. Ecol. Res. 32 , 199–247 (2001).

CAS Google Scholar

Haddaway, N. R., Macura, B., Whaley, P. & Pullin, A. S. ROSES RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses: pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ. Evid. 7 , 7 (2018).

Lwasa, S. et al. A meta-analysis of urban and peri-urban agriculture and forestry in mediating climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 13 , 68–73 (2015).

Pacifici, M. et al. Species’ traits influenced their response to recent climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 7 , 205–208 (2017).

Owen-Smith, N. Ramifying effects of the risk of predation on African multi-predator, multi-prey large-mammal assemblages and the conservation implications. Biol. Conserv. 232 , 51–58 (2019).

Prugh, L. R. et al. Designing studies of predation risk for improved inference in carnivore-ungulate systems. Biol. Conserv. 232 , 194–207 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Effects of biochar application in forest ecosystems on soil properties and greenhouse gas emissions: a review. J. Soil Sediment. 18 , 546–563 (2018).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G., The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6 , e1000097 (2009).

Bernes, C. et al. What is the influence of a reduction of planktivorous and benthivorous fish on water quality in temperate eutrophic lakes? A systematic review. Environ. Evid. 4 , 7 (2015).

McDonagh, M., Peterson, K., Raina, P., Chang, S. & Shekelle, P. Avoiding bias in selecting studies. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews [Internet] (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013).

Burivalova, Z., Hua, F., Koh, L. P., Garcia, C. & Putz, F. A critical comparison of conventional, certified, and community management of tropical forests for timber in terms of environmental, economic, and social variables. Conserv. Lett. 10 , 4–14 (2017).

Min-Venditti, A. A., Moore, G. W. & Fleischman, F. What policies improve forest cover? A systematic review of research from Mesoamerica. Glob. Environ. Change 47 , 21–27 (2017).

Bramer, W. M., Giustini, D. & Kramer, B. M. R. Comparing the coverage, recall, and precision of searches for 120 systematic reviews in Embase, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar: a prospective study. Syst. Rev. 5 , 39 (2016).

Bramer, W. M., Giustini, D., Kramer, B. M. R. & Anderson, P. F. The comparative recall of Google Scholar versus PubMed in identical searches for biomedical systematic reviews: a review of searches used in systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2 , 115 (2013).

Gusenbauer, M. & Haddaway, N. R. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta‐analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods 11 , 181–217 (2020).

Livoreil, B. et al. Systematic searching for environmental evidence using multiple tools and sources. Environ. Evid. 6 , 23 (2017).

Mlinarić, A., Horvat, M. & Šupak Smolčić, V. Dealing with the positive publication bias: why you should really publish your negative results. Biochem. Med. 27 , 447–452 (2017).

Lin, L. & Chu, H. Quantifying publication bias in meta‐analysis. Biometrics 74 , 785–794 (2018).

Haddaway, N. R. & Bayliss, H. R. Shades of grey: two forms of grey literature important for reviews in conservation. Biol. Conserv. 191 , 827–829 (2015).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36 , 1–48 (2010).

Bilotta, G. S., Milner, A. M. & Boyd, I. On the use of systematic reviews to inform environmental policies. Environ. Sci. Policy 42 , 67–77 (2014).

Englund, G., Sarnelle, O. & Cooper, S. D. The importance of data‐selection criteria: meta‐analyses of stream predation experiments. Ecology 80 , 1132–1141 (1999).

Burivalova, Z., Şekercioğlu, Ç. H. & Koh, L. P. Thresholds of logging intensity to maintain tropical forest biodiversity. Curr. Biol. 24 , 1893–1898 (2014).

Bicknell, J. E., Struebig, M. J., Edwards, D. P. & Davies, Z. G. Improved timber harvest techniques maintain biodiversity in tropical forests. Curr. Biol. 24 , R1119–R1120 (2014).

Damette, O. & Delacote, P. Unsustainable timber harvesting, deforestation and the role of certification. Ecol. Econ. 70 , 1211–1219 (2011).

Blomley, T. et al. Seeing the wood for the trees: an assessment of the impact of participatory forest management on forest condition in Tanzania. Oryx 42 , 380–391 (2008).

Haddaway, N. R. et al. How does tillage intensity affect soil organic carbon? A systematic review. Environ. Evid. 6 , 30 (2017).

Higgins, J. P. et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343 , d5928 (2011).

Stewart, G. Meta-analysis in applied ecology. Biol. Lett. 6 , 78–81 (2010).

Koricheva, J. & Gurevitch, J. Uses and misuses of meta‐analysis in plant ecology. J. Ecol. 102 , 828–844 (2014).

Vetter, D., Ruecker, G. & Storch, I. Meta‐analysis: a need for well‐defined usage in ecology and conservation biology. Ecosphere 4 , 1–24 (2013).

Stewart, G. B. & Schmid, C. H. Lessons from meta-analysis in ecology and evolution: the need for trans-disciplinary evidence synthesis methodologies. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 109–110 (2015).

Macura, B. et al. Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence for environmental policy and management: an overview of different methodological options. Environ. Evid. 8 , 24 (2019).

Koricheva, J. & Gurevitch, J. in Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J. et al.) Ch. 1 (Princeton Scholarship Online, 2013).

Britt, M., Haworth, S. E., Johnson, J. B., Martchenko, D. & Shafer, A. B. The importance of non-academic coauthors in bridging the conservation genetics gap. Biol. Conserv. 218 , 118–123 (2018).

Graham, L., Gaulton, R., Gerard, F. & Staley, J. T. The influence of hedgerow structural condition on wildlife habitat provision in farmed landscapes. Biol. Conserv. 220 , 122–131 (2018).

Delaquis, E., de Haan, S. & Wyckhuys, K. A. On-farm diversity offsets environmental pressures in tropical agro-ecosystems: a synthetic review for cassava-based systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 251 , 226–235 (2018).

Popay, J. et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version 1 (Lancaster Univ., 2006).

Pullin, A. S. et al. Human well-being impacts of terrestrial protected areas. Environ. Evid. 2 , 19 (2013).

Waffenschmidt, S., Knelangen, M., Sieben, W., Bühn, S. & Pieper, D. Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: a methodological systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 19 , 132 (2019).

Rallo, A. & García-Arberas, L. Differences in abiotic water conditions between fluvial reaches and crayfish fauna in some northern rivers of the Iberian Peninsula. Aquat. Living Resour. 15 , 119–128 (2002).

Glasziou, P. & Chalmers, I. Research waste is still a scandal—an essay by Paul Glasziou and Iain Chalmers. BMJ 363 , k4645 (2018).

Haddaway, N. R. Open Synthesis: on the need for evidence synthesis to embrace Open Science. Environ. Evid. 7 , 26 (2018).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Shortall from Rothamstead Research for useful discussions on the topic.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mercator Research Institute on Climate Change and Global Commons, Berlin, Germany

Neal R. Haddaway

Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

Neal R. Haddaway & Biljana Macura

Africa Centre for Evidence, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

College of Medicine and Health, Exeter University, Exeter, UK

Alison Bethel

Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

Lynn V. Dicks

School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK

Department of Biological Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, UK

Julia Koricheva

Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Gillian Petrokofsky

Collaboration for Environmental Evidence, UK Centre, School of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, UK

- Andrew S. Pullin

Liljus ltd, London, UK

Sini Savilaakso

Department of Forest Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Evidence Synthesis Lab, School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, University of Newcastle, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK

Gavin B. Stewart

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

N.R.H. developed the manuscript idea and a first draft. All authors contributed to examples and edited the text. All authors have read and approve of the final submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Neal R. Haddaway .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

S.S. is a co-founder of Liljus ltd, a firm that provides research services in sustainable finance as well as forest conservation and management. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary table.

Examples of literature reviews and common problems identified.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Haddaway, N.R., Bethel, A., Dicks, L.V. et al. Eight problems with literature reviews and how to fix them. Nat Ecol Evol 4 , 1582–1589 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-01295-x

Download citation

Received : 24 March 2020

Accepted : 31 July 2020

Published : 12 October 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-01295-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A review of the necessity of a multi-layer land-use planning.

- Hashem Dadashpoor

- Leyla Ghasempour

Landscape and Ecological Engineering (2024)

Synthesizing the relationships between environmental DNA concentration and freshwater macrophyte abundance: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Toshiaki S. Jo

Hydrobiologia (2024)

A Systematic Review of the Effects of Multi-purpose Forest Management Practices on the Breeding Success of Forest Birds

- João M. Cordeiro Pereira

- Grzegorz Mikusiński

- Ilse Storch

Current Forestry Reports (2024)

Parasitism in viviparous vertebrates: an overview

- Juan J. Palacios-Marquez

- Palestina Guevara-Fiore

Parasitology Research (2024)

Environmental evidence in action: on the science and practice of evidence synthesis and evidence-based decision-making

- Steven J. Cooke

- Carly N. Cook

Environmental Evidence (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Limitations of the Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The limitations of the study are those characteristics of design or methodology that impacted or influenced the interpretation of the findings from your research. Study limitations are the constraints placed on the ability to generalize from the results, to further describe applications to practice, and/or related to the utility of findings that are the result of the ways in which you initially chose to design the study or the method used to establish internal and external validity or the result of unanticipated challenges that emerged during the study.

Price, James H. and Judy Murnan. “Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them.” American Journal of Health Education 35 (2004): 66-67; Theofanidis, Dimitrios and Antigoni Fountouki. "Limitations and Delimitations in the Research Process." Perioperative Nursing 7 (September-December 2018): 155-163. .

Importance of...

Always acknowledge a study's limitations. It is far better that you identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor and have your grade lowered because you appeared to have ignored them or didn't realize they existed.

Keep in mind that acknowledgment of a study's limitations is an opportunity to make suggestions for further research. If you do connect your study's limitations to suggestions for further research, be sure to explain the ways in which these unanswered questions may become more focused because of your study.

Acknowledgment of a study's limitations also provides you with opportunities to demonstrate that you have thought critically about the research problem, understood the relevant literature published about it, and correctly assessed the methods chosen for studying the problem. A key objective of the research process is not only discovering new knowledge but also to confront assumptions and explore what we don't know.

Claiming limitations is a subjective process because you must evaluate the impact of those limitations . Don't just list key weaknesses and the magnitude of a study's limitations. To do so diminishes the validity of your research because it leaves the reader wondering whether, or in what ways, limitation(s) in your study may have impacted the results and conclusions. Limitations require a critical, overall appraisal and interpretation of their impact. You should answer the question: do these problems with errors, methods, validity, etc. eventually matter and, if so, to what extent?

Price, James H. and Judy Murnan. “Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them.” American Journal of Health Education 35 (2004): 66-67; Structure: How to Structure the Research Limitations Section of Your Dissertation. Dissertations and Theses: An Online Textbook. Laerd.com.

Descriptions of Possible Limitations

All studies have limitations . However, it is important that you restrict your discussion to limitations related to the research problem under investigation. For example, if a meta-analysis of existing literature is not a stated purpose of your research, it should not be discussed as a limitation. Do not apologize for not addressing issues that you did not promise to investigate in the introduction of your paper.

Here are examples of limitations related to methodology and the research process you may need to describe and discuss how they possibly impacted your results. Note that descriptions of limitations should be stated in the past tense because they were discovered after you completed your research.

Possible Methodological Limitations

- Sample size -- the number of the units of analysis you use in your study is dictated by the type of research problem you are investigating. Note that, if your sample size is too small, it will be difficult to find significant relationships from the data, as statistical tests normally require a larger sample size to ensure a representative distribution of the population and to be considered representative of groups of people to whom results will be generalized or transferred. Note that sample size is generally less relevant in qualitative research if explained in the context of the research problem.

- Lack of available and/or reliable data -- a lack of data or of reliable data will likely require you to limit the scope of your analysis, the size of your sample, or it can be a significant obstacle in finding a trend and a meaningful relationship. You need to not only describe these limitations but provide cogent reasons why you believe data is missing or is unreliable. However, don’t just throw up your hands in frustration; use this as an opportunity to describe a need for future research based on designing a different method for gathering data.

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic -- citing prior research studies forms the basis of your literature review and helps lay a foundation for understanding the research problem you are investigating. Depending on the currency or scope of your research topic, there may be little, if any, prior research on your topic. Before assuming this to be true, though, consult with a librarian! In cases when a librarian has confirmed that there is little or no prior research, you may be required to develop an entirely new research typology [for example, using an exploratory rather than an explanatory research design ]. Note again that discovering a limitation can serve as an important opportunity to identify new gaps in the literature and to describe the need for further research.

- Measure used to collect the data -- sometimes it is the case that, after completing your interpretation of the findings, you discover that the way in which you gathered data inhibited your ability to conduct a thorough analysis of the results. For example, you regret not including a specific question in a survey that, in retrospect, could have helped address a particular issue that emerged later in the study. Acknowledge the deficiency by stating a need for future researchers to revise the specific method for gathering data.

- Self-reported data -- whether you are relying on pre-existing data or you are conducting a qualitative research study and gathering the data yourself, self-reported data is limited by the fact that it rarely can be independently verified. In other words, you have to the accuracy of what people say, whether in interviews, focus groups, or on questionnaires, at face value. However, self-reported data can contain several potential sources of bias that you should be alert to and note as limitations. These biases become apparent if they are incongruent with data from other sources. These are: (1) selective memory [remembering or not remembering experiences or events that occurred at some point in the past]; (2) telescoping [recalling events that occurred at one time as if they occurred at another time]; (3) attribution [the act of attributing positive events and outcomes to one's own agency, but attributing negative events and outcomes to external forces]; and, (4) exaggeration [the act of representing outcomes or embellishing events as more significant than is actually suggested from other data].

Possible Limitations of the Researcher

- Access -- if your study depends on having access to people, organizations, data, or documents and, for whatever reason, access is denied or limited in some way, the reasons for this needs to be described. Also, include an explanation why being denied or limited access did not prevent you from following through on your study.

- Longitudinal effects -- unlike your professor, who can literally devote years [even a lifetime] to studying a single topic, the time available to investigate a research problem and to measure change or stability over time is constrained by the due date of your assignment. Be sure to choose a research problem that does not require an excessive amount of time to complete the literature review, apply the methodology, and gather and interpret the results. If you're unsure whether you can complete your research within the confines of the assignment's due date, talk to your professor.

- Cultural and other type of bias -- we all have biases, whether we are conscience of them or not. Bias is when a person, place, event, or thing is viewed or shown in a consistently inaccurate way. Bias is usually negative, though one can have a positive bias as well, especially if that bias reflects your reliance on research that only support your hypothesis. When proof-reading your paper, be especially critical in reviewing how you have stated a problem, selected the data to be studied, what may have been omitted, the manner in which you have ordered events, people, or places, how you have chosen to represent a person, place, or thing, to name a phenomenon, or to use possible words with a positive or negative connotation. NOTE : If you detect bias in prior research, it must be acknowledged and you should explain what measures were taken to avoid perpetuating that bias. For example, if a previous study only used boys to examine how music education supports effective math skills, describe how your research expands the study to include girls.

- Fluency in a language -- if your research focuses , for example, on measuring the perceived value of after-school tutoring among Mexican-American ESL [English as a Second Language] students and you are not fluent in Spanish, you are limited in being able to read and interpret Spanish language research studies on the topic or to speak with these students in their primary language. This deficiency should be acknowledged.

Aguinis, Hermam and Jeffrey R. Edwards. “Methodological Wishes for the Next Decade and How to Make Wishes Come True.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (January 2014): 143-174; Brutus, Stéphane et al. "Self-Reported Limitations and Future Directions in Scholarly Reports: Analysis and Recommendations." Journal of Management 39 (January 2013): 48-75; Senunyeme, Emmanuel K. Business Research Methods. Powerpoint Presentation. Regent University of Science and Technology; ter Riet, Gerben et al. “All That Glitters Isn't Gold: A Survey on Acknowledgment of Limitations in Biomedical Studies.” PLOS One 8 (November 2013): 1-6.

Structure and Writing Style

Information about the limitations of your study are generally placed either at the beginning of the discussion section of your paper so the reader knows and understands the limitations before reading the rest of your analysis of the findings, or, the limitations are outlined at the conclusion of the discussion section as an acknowledgement of the need for further study. Statements about a study's limitations should not be buried in the body [middle] of the discussion section unless a limitation is specific to something covered in that part of the paper. If this is the case, though, the limitation should be reiterated at the conclusion of the section.

If you determine that your study is seriously flawed due to important limitations , such as, an inability to acquire critical data, consider reframing it as an exploratory study intended to lay the groundwork for a more complete research study in the future. Be sure, though, to specifically explain the ways that these flaws can be successfully overcome in a new study.

But, do not use this as an excuse for not developing a thorough research paper! Review the tab in this guide for developing a research topic . If serious limitations exist, it generally indicates a likelihood that your research problem is too narrowly defined or that the issue or event under study is too recent and, thus, very little research has been written about it. If serious limitations do emerge, consult with your professor about possible ways to overcome them or how to revise your study.

When discussing the limitations of your research, be sure to:

- Describe each limitation in detailed but concise terms;

- Explain why each limitation exists;

- Provide the reasons why each limitation could not be overcome using the method(s) chosen to acquire or gather the data [cite to other studies that had similar problems when possible];

- Assess the impact of each limitation in relation to the overall findings and conclusions of your study; and,

- If appropriate, describe how these limitations could point to the need for further research.

Remember that the method you chose may be the source of a significant limitation that has emerged during your interpretation of the results [for example, you didn't interview a group of people that you later wish you had]. If this is the case, don't panic. Acknowledge it, and explain how applying a different or more robust methodology might address the research problem more effectively in a future study. A underlying goal of scholarly research is not only to show what works, but to demonstrate what doesn't work or what needs further clarification.

Aguinis, Hermam and Jeffrey R. Edwards. “Methodological Wishes for the Next Decade and How to Make Wishes Come True.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (January 2014): 143-174; Brutus, Stéphane et al. "Self-Reported Limitations and Future Directions in Scholarly Reports: Analysis and Recommendations." Journal of Management 39 (January 2013): 48-75; Ioannidis, John P.A. "Limitations are not Properly Acknowledged in the Scientific Literature." Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60 (2007): 324-329; Pasek, Josh. Writing the Empirical Social Science Research Paper: A Guide for the Perplexed. January 24, 2012. Academia.edu; Structure: How to Structure the Research Limitations Section of Your Dissertation. Dissertations and Theses: An Online Textbook. Laerd.com; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Writing Tip

Don't Inflate the Importance of Your Findings!

After all the hard work and long hours devoted to writing your research paper, it is easy to get carried away with attributing unwarranted importance to what you’ve done. We all want our academic work to be viewed as excellent and worthy of a good grade, but it is important that you understand and openly acknowledge the limitations of your study. Inflating the importance of your study's findings could be perceived by your readers as an attempt hide its flaws or encourage a biased interpretation of the results. A small measure of humility goes a long way!

Another Writing Tip

Negative Results are Not a Limitation!

Negative evidence refers to findings that unexpectedly challenge rather than support your hypothesis. If you didn't get the results you anticipated, it may mean your hypothesis was incorrect and needs to be reformulated. Or, perhaps you have stumbled onto something unexpected that warrants further study. Moreover, the absence of an effect may be very telling in many situations, particularly in experimental research designs. In any case, your results may very well be of importance to others even though they did not support your hypothesis. Do not fall into the trap of thinking that results contrary to what you expected is a limitation to your study. If you carried out the research well, they are simply your results and only require additional interpretation.

Lewis, George H. and Jonathan F. Lewis. “The Dog in the Night-Time: Negative Evidence in Social Research.” The British Journal of Sociology 31 (December 1980): 544-558.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Sample Size Limitations in Qualitative Research

Sample sizes are typically smaller in qualitative research because, as the study goes on, acquiring more data does not necessarily lead to more information. This is because one occurrence of a piece of data, or a code, is all that is necessary to ensure that it becomes part of the analysis framework. However, it remains true that sample sizes that are too small cannot adequately support claims of having achieved valid conclusions and sample sizes that are too large do not permit the deep, naturalistic, and inductive analysis that defines qualitative inquiry. Determining adequate sample size in qualitative research is ultimately a matter of judgment and experience in evaluating the quality of the information collected against the uses to which it will be applied and the particular research method and purposeful sampling strategy employed. If the sample size is found to be a limitation, it may reflect your judgment about the methodological technique chosen [e.g., single life history study versus focus group interviews] rather than the number of respondents used.

Boddy, Clive Roland. "Sample Size for Qualitative Research." Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 19 (2016): 426-432; Huberman, A. Michael and Matthew B. Miles. "Data Management and Analysis Methods." In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 428-444; Blaikie, Norman. "Confounding Issues Related to Determining Sample Size in Qualitative Research." International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21 (2018): 635-641; Oppong, Steward Harrison. "The Problem of Sampling in qualitative Research." Asian Journal of Management Sciences and Education 2 (2013): 202-210.

- << Previous: 8. The Discussion

- Next: 9. The Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Advantages and disadvantages of literature review

This comprehensive article explores some of the advantages and disadvantages of literature review in research. Reviewing relevant literature is a key area in research, and indeed, it is a research activity in itself. It helps researchers investigate a particular topic in detail. However, it has some limitations as well.

What is literature review?

In order to understand the advantages and disadvantages of literature review, it is important to understand what a literature review is and how it differs from other methods of research. According to Jones and Gratton (2009) a literature review essentially consists of critically reading, evaluating, and organising existing literature on a topic to assess the state of knowledge in the area. It is sometimes called critical review.

A literature review is a select analysis of existing research which is relevant to a researcher’s selected topic, showing how it relates to their investigation. It explains and justifies how their investigation may help answer some of the questions or gaps in the chosen area of study (University of Reading, 2022).

A literature review is a term used in the field of research to describe a systematic and methodical investigation of the relevant literature on a particular topic. In other words, it is an analysis of existing research on a topic in order to identify any relevant studies and draw conclusions about the topic.

A literature review is not the same as a bibliography or a database search. Rather than simply listing references to sources of information, a literature review involves critically evaluating and summarizing existing research on a topic. As such, it is a much more detailed and complex process than simply searching databases and websites, and it requires a lot of effort and skills.

Advantages of literature review

Information synthesis

A literature review is a very thorough and methodical exercise. It can be used to synthesize information and draw conclusions about a particular topic. Through a careful evaluation and critical summarization, researchers can draw a clear and comprehensive picture of the chosen topic.

Familiarity with the current knowledge

According to the University of Illinois (2022), literature reviews allow researchers to gain familiarity with the existing knowledge in their selected field, as well as the boundaries and limitations of that field.

Creation of new body of knowledge

One of the key advantages of literature review is that it creates new body of knowledge. Through careful evaluation and critical summarisation, researchers can create a new body of knowledge and enrich the field of study.

Answers to a range of questions

Literature reviews help researchers analyse the existing body of knowledge to determine the answers to a range of questions concerning a particular subject.

Disadvantages of literature review

Time consuming

As a literature review involves collecting and evaluating research and summarizing the findings, it requires a significant amount of time. To conduct a comprehensive review, researchers need to read many different articles and analyse a lot of data. This means that their review will take a long time to complete.

Lack of quality sources

Researchers are expected to use a wide variety of sources of information to present a comprehensive review. However, it may sometimes be challenging for them to identify the quality sources because of the availability of huge numbers in their chosen field. It may also happen because of the lack of past empirical work, particularly if the selected topic is an unpopular one.

Descriptive writing

One of the major disadvantages of literature review is that instead of critical appreciation, some researchers end up developing reviews that are mostly descriptive. Their reviews are often more like summaries of the work of other writers and lack in criticality. It is worth noting that they must go beyond describing the literature.

Key features of literature review

Clear organisation

A literature review is typically a very critical and thorough process. Universities usually recommend students a particular structure to develop their reviews. Like all other academic writings, a review starts with an introduction and ends with a conclusion. Between the beginning and the end, researchers present the main body of the review containing the critical discussion of sources.

No obvious bias

A key feature of a literature review is that it should be very unbiased and objective. However, it should be mentioned that researchers may sometimes be influenced by their own opinions of the world.

Proper citation

One of the key features of literature review is that it must be properly cited. Researchers should include all the sources that they have used for information. They must do citations and provide a reference list by the end in line with a recognized referencing system such as Harvard.

To conclude this article, it can be said that a literature review is a type of research that seeks to examine and summarise existing research on a particular topic. It is an essential part of a dissertation/thesis. However, it is not an easy thing to handle by an inexperienced person. It also requires a lot of time and patience.

Hope you like this ‘Advantages and disadvantages of literature review’. Please share this with others to support our research work.

Other useful articles:

How to evaluate website content

Advantages and disadvantages of primary and secondary research

Advantages and disadvantages of simple random sampling

Last update: 08 May 2022

References:

Jones, I., & Gratton, C. (2009) Research Methods for Sports Shttps://www.howandwhat.net/new/evaluate-website-content/tudies, 2 nd edition, London: Routledge

University of Illinois (2022) Literature review, available at: https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/literature-review (accessed 08 May 2022)

University of Reading (2022) Literature reviews, available at: https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/literaturereview/starting (accessed 07 May 2022)

Author: M Rahman