- Darpan ID: DL/2023/0345881

- Regd No.: 403321

- 12 A: AALCB0039QE20221

- 80 G: AALCB0039QF20221

- CSR: CSR00056527

- PAN Card No.: AALCB0039Q

Overcoming challenges in daily life as a blind person

Living with visual impairment presents unique challenges, but it doesn’t mean a blind person cannot lead a fulfilling and independent life. Every day, individuals with visual impairments face various obstacles and work to overcome them with resilience, adaptability, and assistive technology. In this blog, we will explore some of the common challenges faced by blind people in their daily lives and discuss strategies and resources that can help them navigate these hurdles with confidence.

Accessible Technology:

In today’s digital age, technology plays a crucial role in empowering blind individuals. Accessible devices and software such as screen readers, braille displays, and voice assistants enable blind people to access information, communicate, and perform tasks independently. Embracing and mastering these technologies can significantly enhance daily life by providing access to education, employment opportunities, social connections, and entertainment.

Orientation and Mobility:

Navigating the physical world can be a major challenge for blind individuals. Developing effective orientation and mobility skills is essential for independence. Orientation techniques, such as using a white cane or guide dog, help blind individuals detect obstacles, locate landmarks, and navigate unfamiliar environments. Learning to use public transportation systems or utilizing ride-sharing apps with accessible features are also key skills for travel and commuting.

Household Tasks and Organization:

Performing household chores can be demanding for blind individuals, but with the right techniques and tools, they can maintain a well-organized and functional living space. Labeling items in braille or using tactile markers can help with identifying and distinguishing between different objects. Learning adaptive cooking techniques, organizing belongings with tactile systems, and utilizing assistive technologies like talking thermometers and talking clocks can greatly simplify daily tasks.

Employment and Education:

Blind individuals often face unique challenges in pursuing education and finding employment. However, with the right accommodations and support, they can excel in various fields. Accessible educational materials, such as braille textbooks or digital resources, and assistive technologies can facilitate learning. Workplace accommodations, including screen magnifiers, screen readers, and accessible formats of documents, enable blind individuals to thrive in professional environments.

Social Inclusion:

Blind individuals may encounter social barriers and misconceptions that can hinder their participation in social activities. Educating others about blindness and promoting inclusivity is crucial. Encouraging open communication, providing accessibility information about events or venues, and fostering inclusive attitudes can help blind individuals feel welcome and actively participate in social gatherings, sports, cultural events, and hobbies.

Conclusion:

While living with blindness presents unique challenges, individuals with visual impairments can overcome them and lead fulfilling lives. By embracing accessible technology, developing orientation and mobility skills, mastering household tasks, accessing education and employment opportunities, and promoting social inclusion, blind individuals can navigate daily challenges with confidence and independence. It is essential for society to recognize the abilities and potential of blind individuals and work towards creating inclusive environments that support their diverse needs.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How to Be Blind

By Andrew Leland

Andrew Leland reads.

I first noticed something wrong with my eyes in New Mexico. I was a freshman in high school, in the mid-nineties, and had recently been accepted into a clique of older kids whom I admired—the inner circle of Santa Fe Prep’s druggie bohemian scene. We hung out at Hank’s house; he was our charismatic leader, and his mom was maximally permissive. One night, in Hank’s room, our friend Chad sat on a beanbag chair, packing a pipe with weed. Nina danced alone in front of a boom box to Jane’s Addiction, throwing around her bleached hair. After dark, we hiked up the hill behind the house to get a view of the city. The moon was bright, but I found myself tripping on roots and stones and wandering off track. At one point, I walked right into a piñon tree with prickly branches. My friends laughed—“You’re stoned, aren’t you?” Chad said—and I played up my intoxication for effect. But, on the way down, I quietly put a hand on Hank’s shoulder.

This became common. At the movies, I got up to get a soda, and, when I returned, I couldn’t find my mother in the rows of featureless bodies. I complained about night blindness, but my mother assured me it was normal—it was dark out there! Eventually, though, she brought me to see an eye doctor. After a series of tests, he sat us down and said that I had retinitis pigmentosa, or R.P., a rare disease affecting about a hundred thousand people in the U.S. As the disease progressed, the rod cells around the edges of my retina would die, followed by the cones. My vision would contract, like looking through a paper-towel roll. By middle age, I’d be completely blind. The doctor asked if I could see stars, and I said that I hadn’t seen them in years. This was the detail that made it real for my mother. “You can’t see stars?” she asked.

I spent my teen-age years mostly in denial: my blindness seemed distant, like fatherhood, or death. But in my thirties the disease caught up with me. One morning, I swung my car into a crosswalk and heard—and felt—something slamming my hood: I had almost hit a pedestrian, and he was banging my car with his fist, shouting, “Open your fucking eyes!” Soon after, I almost hit a cyclist, and I gave up driving. One weekend, while living in Missouri, I found that I had lost my sunglasses. My wife, Lily, was out of town, so I decided to walk to a nearby LensCrafters. But what was normally a ten-minute drive became a harrowing ordeal on foot. There were few sidewalks, so I walked in the road, with cars speeding past. The sun and haze made it hard to see. I stood for a long time at a large intersection, trying to turn left without getting hit by a truck.

In 2011, I ordered an I.D. cane, used less for tapping around than to signal to the world that its bearer might not see well. It folded up, and mostly I hid it in my bag. But, after running into fire hydrants and hip-checking a toddler in a café, I began using it full time. Reading became difficult: the white of the page took on a wince-inducing glare, and the words frosted over, like the lowermost lines on the optometrist’s eye chart. It was only once I’d reached this stage that my diagnosis started to feel real. I frantically wondered whether I should use my last years to, say, visit Japan, or plow through the Criterion Collection, instead of spending my evenings watching “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” with Lily. One night, I lay awake in bed. I knew that, if Lily were awake, she’d be able to see the blankets, the window, the door, but, when I scanned the room, I saw nothing, just the flashers and floaters that oscillated in my eyes. Is this what it will be like? I wondered, casting my gaze around like a dead flashlight. I felt like I’d been buried alive.

In 2020, I heard about a residential training school called the Colorado Center for the Blind, in Littleton. The C.C.B. is part of the National Federation of the Blind, and is staffed almost entirely by blind people. Students live there for several months, wearing eye-covering shades and learning to navigate the world without sight. The N.F.B. takes a radical approach to cultivating blind independence. Students use power saws in a woodshop, take white-water-rafting trips, and go skiing. To graduate, they have to produce professional documents and cook a meal for sixty people. The most notorious test is the “independent drop”: a student is driven in circles, and then dropped off at a mystery location in Denver, without a smartphone. (Sometimes, advanced students are left in the middle of a park, or the upper level of a parking garage.) Then the student has to find her way back to the Colorado Center, and she is allowed to ask one person one question along the way. A member of an R.P. support group told me, “People come back from those programs loaded for bear ”—ready to hunt the big game of blindness. Katie Carmack, a social worker with R.P., told me, of her time there, “It was an epiphany.” That fall, I signed up.

In 1966, the sociologist Robert Scott spent three years visiting agencies for the blind for his book “ The Making of Blind Men .” Most of these agencies, whose methods were based on the training programs developed for veterans after the First World War, took an “accommodative approach”: they believed that clients could never be truly independent, and strove only to keep them safe and comfortable. The agencies installed automated bells over their front doors so that residents could easily find the entrance from the street, served pre-cut foods, and gave out only spoons. They celebrated clients for the tiniest accomplishments, with the result that, as Scott put it, “many of them come to believe that the underlying assumption must be that blindness makes them incompetent.”

Blind education already had a fraught history. The first secular institution for the blind—the Hospice des Quinze-Vingts, established by King Louis IX of France around 1260—housed residents, but required them to beg on the streets for bread. Blind people were popularly depicted as lecherous, duplicitous, and drunk. The first schools that actually tried to teach blind students were established in the eighteenth century. Catherine Kudlick, a disability historian, pointed out that this was during the height of the Enlightenment, when there were discussions about educating women and people from the lower classes. “The idea was to give them the tools so that they could become educated members of society,” she said. But, in their determination to prepare students for employment, many schools, like other institutions at the time, came to resemble sweatshops, making blind children spin wool and grind tobacco for subminimum wages.

The best institutions Scott visited were those that followed the philosophy of Father Thomas Carroll, a Catholic priest who worked at the Army’s rehabilitation centers during the Second World War, where many innovations—including the long white cane—were first developed. Carroll argued that the average blind person is capable of some independence. His students took fencing lessons, which he thought helped with balance. But Carroll took a surprisingly grim view of blindness. “Loss of sight is a dying,” he wrote. His students, he believed, would always be significantly impaired. One student who recently attended the Carroll Center, in Newton, Massachusetts, told me that he felt coddled there. “I didn’t feel a lot of independence,” he said. “We go to these places because we want to level up our independence, and be pushed to the edge. We need that.”

Carroll’s philosophy met its sharpest critic in Kenneth Jernigan, the president of the National Federation of the Blind. The N.F.B. was founded, in 1940, as an organization of and not for the blind: its constitution mandated that a majority of its chapter members had to be blind. Jernigan rejected Carroll’s Freudian sense of blindness—Carroll has described it in terms of castration—in favor of a civil-rights approach. Blindness, he insisted, was merely a characteristic, like hair color; it was an intolerant society that was disabling. He organized protests against airline policies that forced blind passengers to sit in handicap seats and give up their canes; his followers held sit-ins on planes, and were physically carried off by police.

In the fifties, Jernigan and his colleagues proposed an experiment: the N.F.B. would take control of a state agency for the blind in Iowa—which a federal study had rated one of the worst in the country—and reinvent it. At this center, and those which followed, blind teachers took students waterskiing and rock climbing. At traditional agencies, blind students (but not instructors) were addressed by their first names. Jernigan mandated that his students be addressed by “Mr.” and “Ms.” as a sign of respect. N.F.B. employees followed a strict dress code: ties and jackets for men, skirts for women. Bryan Bashin, the former C.E.O. of the San Francisco LightHouse for the Blind, one of the largest blindness agencies in the U.S., compared this to the suited brothers in the Nation of Islam: “We were not going to give our oppressors the right to say we’re sloppy or unprofessional.”

Blindness agencies traditionally taught students to travel by route memorization: walk down the block for fifty-five paces, and the entrance to the café is on your right. Jernigan pointed out the obvious flaw: you were at a loss as soon as you travelled or the coffee shop closed. The N.F.B. developed a method that came to be known as “structured discovery”: students learn to pay attention to their surroundings and use the information to orient themselves. Instructors were constantly asking Socratic questions, such as “What direction do you hear the traffic coming from?” and “Can you feel the sun warming one side of your face?” Bashin told me, of what he learned by spending a year at a center, “Confidence isn’t a deep enough word. It’s a faith in your ability to figure it out.” He added, “Until you get profoundly lost, and know it’s within you to get unlost, you’re not trained—until you know it’s not an emergency but a magnificent puzzle.”

Students were pushed out of their comfort zones. Gene Kim, a recent C.C.B. graduate, told me that, for his independent drop, he was let off at some place resembling a hospital. He spent hours crossing bridges, “weird islands and right-turn lanes, weirdly cut curbs.” He was on the verge of giving up when he heard a dinging sound, and followed it to a light-rail train that took him home. The experience, he said, helped him make peace with the “relentless uncertainty” of blind travel. The historian Zachary Shore, on the other hand, got so lost on his independent drop that he stubbornly picked a direction and just kept walking. Police officers stopped him when he was about to walk onto a highway, and gave him a ride back to the center, where the director told him, “You failed this time. But we’re gonna make you do it again—and you will do it. I know you can do it. And we’re going to give you an even harder route.” (On his second try, Shore found his way back.)

Sometimes teachers crossed a line. In 2020, dozens of students alleged that staff at N.F.B. centers had bullied them, sexually harassed or assaulted them, or made racist remarks. Many students at the centers had, in addition to blindness, a range of other disabilities: hearing loss, mobility impairments, cognitive disabilities. Some reported being mocked for having impairments that made the intense mental mapping required by blind-cane travel a challenge. Bashin ascribed this to the fact that blind people, like any collection of Americans, regrettably included their share of racists, abusers, and jerks. He said, of the N.F.B., “As a people’s movement, it looks like the U.S. It is a very big tent, and it is working to insure respect for all members.” But a group of “victims, survivors, and witnesses of sexual and psychological abuse” wrote an open letter in the wake of the allegations, blaming, in part, the N.F.B.’s tough methods. “What blind consumers want in the year 2020 is not what they may have wanted in previous decades,” they wrote. “We don’t want to be bullied or humiliated or have our boundaries pushed ‘for our own good.’ ”

The N.F.B. has since launched an internal investigation and formed committees dedicated to supporting survivors and minorities. Jernigan once mocked Carroll’s notion that blind people needed emotional support, but the N.F.B. now maintains a counselling fund for members who endured abuse at its centers or any of its affiliated programs or activities. Julie Deden, the director of the Colorado Center, told me, “I’m saddened for these people, and I’m sorry that there’s been sexual misconduct.” She is also sad that people felt like they were pushed so hard that it felt like abuse, she noted. “We don’t want anyone to ever feel that way,” she said. But, she added, “If people really felt that way, maybe this isn’t the program for them. We do challenge people.” Ultimately, she said, she had to defend her staff’s right to push the students: “Really, it’s the heart of what we do.”

The twenty-four units at the McGeorge Mountain Terrace apartments are all occupied—music often blasts from a window on the second floor, and laughter wafts up by the picnic tables—but there are no cars in the parking lot, because none of its residents have driver’s licenses. The apartments house students from the Colorado Center. At 7:24 A.M. every weekday, residents wait at the bus stop outside, holding long white canes decorated with trinkets and plush toys, to commute to class. I arrived at the center in March, 2021. When the receptionist greeted me, I saw her gaze stray past me. Nearly everyone in the building was blind. In the kitchen, students in eyeshades fried plantain chips, their white canes hanging on pegs in the hall. In the tech room, the computers had no monitors or mouses—they were just desktop towers attached to keyboards and good speakers. A teen-ager played an audio-only video game, which blasted gruesome sounds as he brutalized his enemies with a variety of weapons.

When I met the students and staff, I was impressed by blindness’s variety: there were people who had been blind from birth, and those who’d been blind for only a few months. There were the greatest hits of eye disease, as well as a few ultra-rare conditions I’d never heard of. Some people had traumatic brain injuries. Makhai, a self-described stoner from Colorado, had been in a head-on collision with a Ford F-250. Steve had been working in a diamond mine in the Arctic Circle when a rock the size of a two-story house fell on top of him, crushing his legs and blinding him. Alice, a woman in her forties, told me that her husband had shot her. She woke up from a coma and doctors informed her that she was permanently blind, and asked her permission to remove her eyeballs. “I never mourned the loss of my vision,” she told me. “I just woke up and started moving forward.” She said that she’d had a number of “shenanigans” at the center, her word for falls, including a visit to the emergency room after she slipped off a curb and slammed her head into a parked truck. At the E.R., she learned that she had hearing loss, too, which affected her balance; when she got hearing aids, her shenanigans decreased.

Soon after, my travel instructor, Charles, had me put on my shades: a hard-shell mask padded with foam. (Later, the center began using high-performance goggles that a staffer painstakingly painted black, which made me feel like a paratrooper.) I was surprised by how completely the shades blocked out the light—I saw only blackness. I left the office, following the sound of Charles’s voice and the knocking of his cane. “How are you with angles?” he said. “Make a forty-five-degree turn to the left here.” I turned. “That’s more like ninety degrees, but O.K.,” he said. Embarrassed, I corrected course. With shades on, angles felt abstract. On my way back to the lobby, I got lost in a foyer full of round tables. Later, another student, Cragar Gonzales, showed me around. He’d fully adopted the N.F.B.’s structured-discovery philosophy, and asked constant questions. “What do you notice about this wall?” he said. This was the only brick wall on this floor, he told me, so whenever I felt it I’d instantly know where I was. By the end of the day, though, I still wasn’t able to get around on my own. I felt a special shame when I had to ask Cragar, once again, to bring me to the bathroom.

That afternoon, I followed Cragar to lunch. He had compared the school’s social organization to high-school cliques, except that the wide age range made for some unlikely friendships; a few teen-agers became drinking buddies with people pushing fifty. A teen-ager named Sophia told me that so many people at the center hooked up that it reminded her of “ Love Island ”: “People come in and out of the ‘villa.’ People are with each other, and then not.” Within a few days, I started hearing gossip about students throughout the years who had sighted spouses back home but had started having affairs. Some of the students had lived very sheltered lives before coming to the program: classes brought together people with Ph.D.s and those who had never learned to tie their shoes. One staff member told me that some students arrive with no sex education, and there are those who become pregnant soon after arriving at the center.

I’d heard that some people find wearing the shades intolerable, and make it to Colorado only to quit after a few days. I found it a pain in the ass, but also fascinating—like solving Bashin’s “magnificent puzzles.” On the same day that I arrived, I’d met a student nicknamed Lewie who had a high voice, and I spent the day thinking he was a woman. But people kept calling him man and buddy , and, with some effort, I reworked my mental image. Lewie had cooked a meal of arroz con pollo . I felt nervous about eating with the shades on, but I found it less difficult than I expected. Only once did I raise an accidentally empty plastic fork to my lips. At one point, I bit into what I thought was a roll, meant to be dipped in sauce, and was sweetly surprised to find that it was an orange-flavored cookie.

I began to think of walking into the center each day as entering a kind of blind space. People gently knocked into one another without complaint; sometimes, they jokingly said, “Hey, man, what’d you bump into me for?”—as if mocking the idea that it might be a problem. Students announced themselves constantly, and I soon felt no shame greeting people with a casual “Who’s that?” Staff members were accustomed to students wandering into their offices accidentally, exchanging pleasantries, then wandering off. One day, I was having lunch, and my classmate Alice entered, then said, “Aw, man, why am I in here ?”

I learned an arsenal of blindness tricks. I wrapped rubber bands around my shampoo bottles to distinguish them from the conditioner. I learned to put safety pins on my bedsheets to keep track of which side was the bottom. I cleaned rooms in quadrants, sweeping, mopping, and wiping down each section before moving on. I had heard about a gizmo you could hang on the lip of a cup that would shriek when a liquid reached the top. But Cragar taught me just to listen: you could hear when a glass was almost full. In my home-management class, Delfina, one of the instructors, taught me to make a grilled-cheese. I used a spoon on the stove like a cane to make sure the pan was centered without torching my fingers. Before I flipped the sandwich, I slid my hand down the spatula to make sure the bread was centered. When I finished, I ate it hungrily; it was nice and hot.

One weekend, I went with a group of students to play blind ice hockey. The puck was three times the size of a normal puck, and filled with ball bearings that rattled loudly. On St. Patrick’s Day, we went to a pub and had Irish slammers. One day, Charles took me and a few other students to Target to go grocery shopping. This was my first time navigating the world on my own with shades, and every step—getting on the bus, listening to the stop announcements—was distressing. When we got to Target, we were assigned a young shopping assistant named Luke. He pulled a shopping cart through the store, as we hung on, travelling like a school of fish. Charles had invited me to his apartment for homemade taquitos , and I asked Luke to show us the tortilla chips. He started listing flavors of Doritos—Flamin’ Hot, Cool Ranch. “Do you have ‘Restaurant Style’?” I asked, with minor humiliation.

At the self-checkout station, I realized that I couldn’t distinguish between my credit and debit cards. “Is this one blue?” I asked, holding one up.

“It’s red,” Luke said.

I couldn’t bring myself to enter my PIN with shades on, so I cheated for my first and only time, and pulled them up. The fluorescent blast of Target’s interior made me dizzy. I found my card, and then quickly pulled the shades back down. We retraced our steps back to the bus stop. As we got closer, we heard the unmistakable squeal of bus brakes. “Go to that sound!” Charles shouted, and we ran. I wound up hugging the side of the bus and had to slide to the door. When I made it to my seat, I was proud and exhausted.

One day, after class, I headed back to the apartments with Ahmed, a student in his thirties. Ahmed has R.P., like me, but he had already lost most of his vision during his last year of law school. He’d managed to learn how to use a cane and a screen reader, which reads a computer’s text aloud, and still graduate on time. But his progression into blindness took a steep toll. After he passed the bar, he moved to Tulsa, where he had what he describes as a “lost year.” He deflected most of my questions about what he did during that time, only gesturing toward its bleakness. “But why Tulsa?” I asked.

“Because it was cheap,” he said. He knew no one in the city. He just needed a place to go and be alone with his blindness.

With apologies to a city that I’ve enjoyed visiting, after listening to Ahmed, I began to think of Tulsa as the depressing place you go when you confront the final loss of sight. When would I move to Tulsa?

The public perception of blindness is that of a waking nightmare. “Consider them, my soul, they are a fright!” Baudelaire wrote in his 1857 poem “The Blind.” “Like mannequins, vaguely ridiculous, / Peculiar, terrible somnambulists, / Beaming—who can say where—their eyes of night.” Literature teems with such descriptions. From Rilke’s “Blindman’s Song”: “It is a curse, / a contradiction, a tiresome farce, / and every day I despair.” In popular culture, Mr. Magoo is cheerfully oblivious to the mayhem that his bumbling creates. Al Pacino , in “Scent of a Woman,” is, beneath his swaggering machismo, deeply depressed. “I got no life,” he says. “I’m in the dark here!” Many blind people (including me) resist using the white cane precisely because of this stigma. One of the strangest parts of being legally blind, while still having enough vision to see somewhat, is that I can observe the way that people look at me with my cane. Their gaze—curious, troubled, averted—makes me feel like Baudelaire’s somnambulist, the walking dead.

In response to this, blind activists have pushed the idea that blindness is nothing to grieve—that it’s something to be celebrated. “Blindness is not a tragedy,” the writer and former C.C.B. counsellor Juliet Cody said. “It’s a positive opportunity to have faith and believe in yourself.” I find this notion appealing, even liberating. But I’ve also struggled to force myself into an epiphany. When I’m honest with myself, I find that I’m already mourning the loss of small things: the ability to drive my son to the mountains for a hike, or to browse the stacks in a library. Cragar told me that, when his vision loss began to accelerate, he told his family that he wasn’t scared—that he was ready. But he admitted to me that he wasn’t so sure: “I say that, but do I really know?” Tony, another student I met at C.C.B., told me that, when he realized he could no longer see the chalkboard in his college classes, he retreated to his dorm room, flunked out, moved back in with his father, and spent his disability money on weed, to numb out. “I hit some very dark chunks,” he told me. One night, in Colorado, I heard a student say, “When I lost my vision, I didn’t leave my bed for a month.”

In my weeks at the center, I began to suspect that consolation lies not in any moment of catharsis but in an acknowledgment of blindness’s ordinariness. The Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote that blindness “should not be seen in a pathetic way. It should be seen as a way of life: one of the styles of living.” Accepting blindness’s difficulty allows one to move on. “Life is never meant to be easy,” Erik Weihenmayer, the first blind person to climb Mt. Everest, wrote in his memoir, “ Touch the Top of the World .” “Ironically when I finally accepted this reality, that’s when life got easy.” Under sleep shades, I found that I could read, write, cook, travel. There was frustration, but this wasn’t unique to blind life. At one point, as I listened to the chatter of a cafeteria full of blind people, I thought, How strange that I’m still myself. I’d worried over stories of people unable to handle total occlusion, but, in the moment, it felt surprisingly normal.

I began to appreciate the novel experiences that blindness gave me. The notion that blind people have better hearing than the sighted is a myth, but relying on my ears did change my relationship with sound. Neuroscientists have found that the visual cortices of blind people are activated by such activities as reading Braille, listening to speech, and hearing auditory cues, such as the echo of a cane’s taps. At lunch, one day, Cragar’s wife, Meredith, who was visiting from Houston, came into the room carrying their fifteen-month-old daughter, Poppy. The sounds that she made—cooing, laughing—cut through the room like washes of color. I didn’t quite hallucinate these colors, but I came close. In the coming weeks, I had several mildly psychedelic experiences like this, a kind of blind synesthesia. The same thing happened with touch. I played blackjack with a Braille deck, and, after a few days, began to intuitively read the cards as if I were seeing them. In the art room, a teacher taught me to pull a wire through a mound of wet clay. Later, as I described the experience to Lily and our son, Oscar, on a video call, I had to remind myself that I’d never actually seen this tool or the clay. It was so clear in my mind’s eye.

My sense of space gradually transformed. Walking the carpeted halls of the center’s lower level, I could see a faint black-and-blue virtual-reality environment lit by some unseen light source. Sometimes my cane penetrated one of the velvety walls, and I had to redraw my mental map. When I was out in the city, Charles sometimes informed me that what I thought was Alamo Avenue was actually Prince Street, or that east was actually north, and I had to lift the landscape in my mind, rotate it ninety degrees, and set it back down. I could almost feel my brain trembling under the strain. But it was also kind of fun.

On your last day at the center, the staff presents you with a “freedom bell” emblazoned with the words “ TAKE CHARGE WITH CONFIDENCE AND SELF-RELIANCE !” (Students sometimes quote this when doing banal activities like trying to find the bathroom.) At Lewie’s graduation, a few weeks into my stay, Julie invited him to ring the bell, saying that it represented not just his independence but that of blind people everywhere. My time at the center was cut short by family demands, but this spring I returned to see how far I had come. On my second-to-last day, Charles told me that I would be doing an independent drop. This seemed extreme; most students do that test after being at the center for nine months; I had been there for a total of four weeks. I rode out in the center’s van with another instructor, Ernesto, feeling nervous. “I need some reassurance,” I told him. “Do you really think that I’m ready to do this on my own?”

“Actually, Andrew, it was two against one,” Ernesto said flatly. He had been outvoted.

When we arrived at my drop point, Josie, one of the center’s few sighted employees and its designated driver, seemed worried. “Don’t get out on that side!” she said. Stepping out of the van, I felt immediately disoriented. The sun was shining on my face, so I had to be facing east. My cane hit a wooden door, and a dog started barking. This must be a residential street. I’d learned, when lost, to find a bus stop. Most students used their one question to ask the driver where to go, and had memorized the bus routes and rail lines sufficiently to make it home from there. There wouldn’t be a bus stop on a residential block, so I set off toward the sound of traffic.

I soon arrived at a busy intersection. One of the hardest parts of blind travel is crossing the street. Once you leave the curb, there’s nothing guiding you to the other side, and you might walk in front of a car. Most corners have a dip for wheelchairs, but these sometimes point across the street, and sometimes point diagonally into the middle of the intersection. I learned to use my ears to find my way. I listened to the perpendicular traffic driving past my nose and calibrated my alignment so that the sound was equal in both ears—like balancing a stereo. When the light changed, I took off. I listened to the cars roaring past me, adjusting my trajectory to stay parallel to them. I felt the crown of the road (which rises and falls, to allow water to drain) beneath my feet, and that let me know that I was halfway. When my cane connected with the far curb, I could feel my heart pounding.

I must have often looked bewildered on my journey. At one point, I was trying to decide whether a dip was a corner or a driveway, and a driver slowed down and said, “You drop something, buddy?” I answered, with forced cheer, “Thanks! I’m just exploring.” At a big, four-lane intersection, I stood for a long time, listening. A worker from a hospital came out to check on me, and, when I told him I was looking for a bus stop—not technically a question, but a little sneaky nonetheless—he pointed me in the general direction. He went back to work, saying mournfully, as though leaving me to die, “Please take care.”

Blind travel requires you to think like an urban planner. Charles had taught me to swing my cane wide in search of a bus pole. On wide downtown blocks, bus stops are curbside, but on narrower streets they’re set back behind the grass line. Halfway up one block, I connected with a metal bench. I lifted my cane and hit a low roof. There was no pole, but what else could this be? When the bus arrived, I climbed aboard and let fly my official question: “How do I get to Littleton/Downtown station?” The driver told me to go to the end of the line, then take the light-rail. When we got to the rail station, I crossed the tracks, and boarded a train. In Littleton, I almost stepped on a person passed out on the ground. I walked back to the center, hearing the familiar sound of tapping canes as I arrived. An announcement went out that I had returned, and cheers rose up from the classrooms.

The next night, I did a cooking test, making lemon-garlic kale salad and red-lentil soup. It took me about twice as long as it would have without shades, and I burned a finger. Still, I was surprised by how good it tasted. The students gathered around the kitchen table, and one sat on the couch; this arrangement would have been visually odd, but, sonically, it felt perfectly natural. Ernest, a member of a Black Methodist church, said that he thought his blindness made him more holy. “I walk by faith, not by sight,” he said, quoting Scripture. My classmate Steve suggested, dubiously, that being blind made him less susceptible to racism. He told us that he’d been working with a physical therapist who came from Japan, and had accidentally touched her cornrows and realized that she was Black—she had been born in Congo. Michelle, a sound engineer from Mexico, disagreed, saying that she didn’t think blindness made her any more “pure.” I spilled a cold cup of coffee into a supermarket cake, but we were all full by then anyway.

The next morning, I flew home. As I exited the plane, sweeping my cane in front of me, a man asked if I needed help. I ignored him and headed toward the baggage claim, but he followed me, irritated, repeating, “Do you need any help ?” I shook my head. I didn’t. I followed the sound of roller bags, feeling the carpet of the gate area give way to the concourse’s linoleum. I was halfway to the escalators before I thought of using my eyes to look around for an exit sign. I already knew where I was going. ♦

This is drawn from “ The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight. ”

New Yorker Favorites

Searching for the cause of a catastrophic plane crash .

The man who spent forty-two years at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool .

Gloria Steinem’s life on the feminist frontier .

Where the Amish go on vacation .

How Colonel Sanders built his Kentucky-fried fortune .

What does procrastination tell us about ourselves ?

Fiction by Patricia Highsmith: “The Trouble with Mrs. Blynn, the Trouble with the World”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Zach Williams

By Christopher Fiorello

By Joseph O’Neill

By Mohammed Naseehu Ali

Daily Life Problems, Struggle and Challenges Faced by Blind People

Samyak Lalit is an author and disability rights activist. He is a polio survivor and the founder of projects like Kavita Kosh, Gadya Kosh, TechWelkin, WeCapable, Dashamlav and Viklangta Dot Com. Website: www.lalitkumar.in

Blindness is one of the most, if not the most, misunderstood type of disability . The general masses have their own pre-conceived notions about the blind people that they firmly believe to be true without even getting in touch with a blind person. Most of the members of the non-blind community believe that the blind people cannot do their work or live a normal life. ‘My Son will not be a Beggar Be’ by Ved Mehta is a perfect example of the contradiction of society’s perspective and the reality of a blind person’s life.

Blind people do lead a normal life with their own style of doing things. But, they definitely face troubles due to inaccessible infrastructure and social challenges. Let us have an empathetic look at some of the daily life problems, struggles and challenges faced by the blind people.

Navigating Around Places

The biggest challenge for a blind person, especially the one with the complete loss of vision, is to navigate around places. Obviously, blind people roam easily around their house without any help because they know the position of everything in the house. People living with and visiting blind people must make sure not to move things around without informing or asking the blind person.

Commercial places can be made easily accessible for the blinds with tactile tiles . But, unfortunately, this is not done in most of the places. This creates a big problem for blind people who might want to visit the place.

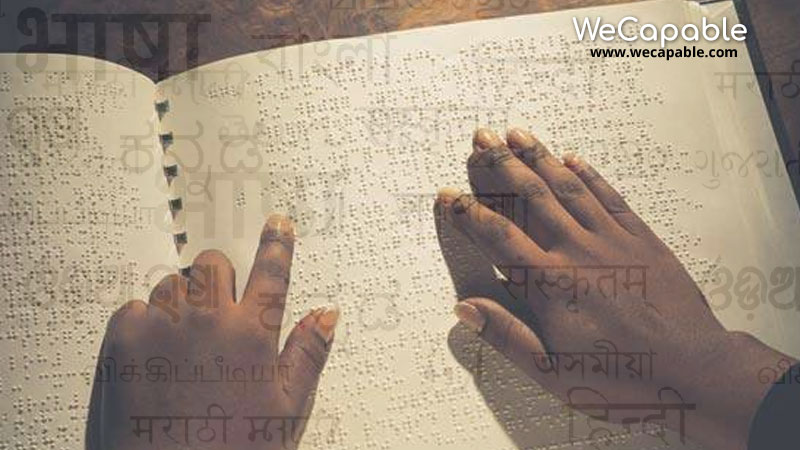

Finding Reading Material

Blind people have a tough time finding good reading materials in accessible formats. Millions of people in India are blind but we do not have even the proper textbooks in braille , leave alone the novels and other leisure reading materials. Internet, the treasure trove of information and reading materials, too is mostly inaccessible for the blind people. Even though a blind person can use screen reading software but it does not make the Internet surfing experience very smooth if the websites are not designed accordingly. Blind person depends on the image description for understanding whatever is represented through pictures. But most of the time, websites do not provide clear image description.

Arranging Clothes

As most of the blind people depend on the objects’ shape and texture to identify them — arranging the laundry becomes a challenging task. Although a majority of blind people device their own technique to recognize and arrange at least their own clothes but it still is a challenging chore. This becomes a daredevil task if it’s about pairing and arranging the socks. All this is because recognizing colors is almost impossible for the persons with total blindness.

Overly Helpful Individuals

It is good to be kind and help others. But overly helpful individuals often create problems for the blind person. There are lots of individuals who get so excited to help a disabled person that they forget even to ask the person whether she needs help or not. A blind person might be doing something painfully slow (from your perspective) but you should not hurry in doing the work without asking the person properly. You might end up creating some trouble for the blind person.

Getting Devices to Become Independent

The most valuable thing for a disabled person is gaining independence. A blind person can lead an independent life with some specifically designed adaptive things for them. There are lots of adaptive equipment that can enable a blind person to live their life independently but they are not easily available in the local shops or markets. Refreshable Braille Display is an example of such useful devices. A blind person needs to hunt and put much effort to get each equipment that can take them one step closer towards independence.

Everyone faces challenges in their life… blind people face a lot more. But, this certainly does not mean that you can show sympathy to blind persons. They too, just like any individual, take up life’s challenges and live a normal life, even if it does not seem normal to the sighted individuals.

Are you a person with visual impairment? Please share with us the problems that you face in your day-to-day life. Sharing information can show path to the solution of many problems! Thank you for connecting with WeCapable!

"Daily Life Problems, Struggle and Challenges Faced by Blind People." Wecapable.com . Web. April 7, 2024. < https://wecapable.com/problems-faced-by-blind-people/ >

Wecapable.com, "Daily Life Problems, Struggle and Challenges Faced by Blind People." Accessed April 7, 2024. https://wecapable.com/problems-faced-by-blind-people/

"Daily Life Problems, Struggle and Challenges Faced by Blind People." (n.d.). Wecapable.com . Retrieved April 7, 2024 from https://wecapable.com/problems-faced-by-blind-people/

5 responses to “Daily Life Problems, Struggle and Challenges Faced by Blind People”

I am totally blind, and can relate to this article. As a 65-year-old, I can honestly say things are easier now than when I was growing up. Mobility canes, phones and products with screen-readers, and educating the general public have helped a lot. But the challenges of everyday life are still many. Yet when one has lived as long as I, the blind person knows what his challenges are, and can either ask for sighted assistance, or find a product suitable for his needs.

can u tell what are your hardships

My husband has type 2 diabetes and is losing his eyesight. He is not totally blind but the prospect of the possibility of him going blind is very scary for me. He’s 63 years old and very independent. I’m afraid of what this will do to him. I know people who are blind can be very productive and independent but I also know that initially, it can be a challenge accepting life without vision. I know my husband is going through a lot of different emotions, right now he’s angry, and I’d like to know what I can do to help but not be too helpful as I want him to be as independent as he is now. Any resources you can provide are greatly appreciated.

I recently began living with an old friend who became totally blind 14 months ago. He connected with Lighthouse for the Blind. He was taught how to function being blind. One of his biggest challenges was using Uber to get to places. He experienced a lot of anxiety being picked up and taken to his destination. He’s afraid the driver will drop him off at the wrong place and abandon him. Recently he had to pick up a prescription and told the driver as such, when they arrived at Walgreens driver wanted to drop him off. He had to plead with the driver to go thru. the drive thru and take him home after. Bad experience. Also when ordering a ride you cant communicate your condition or wishes. Uber needs to become more blind user friendly.

This article sheds light on the daily challenges faced by individuals with blindness, and it’s important to recognize the impact of cataract-induced blindness, which is a prevalent and treatable condition. Initiatives like the Tej Kohli Eye Foundation, play a crucial role in addressing these challenges by providing accessible eye care and working towards a world where cataracts no longer hinder the daily lives of those affected. Let’s continue advocating for awareness and support for those navigating life with visual impairments.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Inside the incredible school where blind people learn to rock climb, cook, and live totally independently

The INSIDER Summary:

• Losing your vision doesn't mean losing your independence. • At the Colorado Center for the Blind, people with vision loss learn how to cook, use computers, travel with a cane, and tackle home repairs without any need for sight. • Students even try outdoor adventures, like whitewater rafting and rock climbing.

Most sighted people are terrified of blindness.

In one recent survey , a sample of Americans rated going blind as a worse fate than losing memory, speech, hearing, or a limb. In another , a majority of respondents believed that going blind leads to a loss of independence.

It's true that vision loss leads to some limitations — blind people can't drive cars or pilot airplanes, for instance. But that doesn't mean they can't live full, independent lives on par with their sighted peers.

That's the philosophy at the Colorado Center for the Blind (CCB), where blind people from all walks of life learn how to tackle everyday tasks and live on their own.

The CCB, a private nonprofit established in 1988 and located just outside Denver, is one of just three training programs of its kind in the country. Its flagship course is called the Independence Training Program , or ITP. It's for adults from all over the country who were born blind or lost vision later in life and want to learn independent living skills.

"Blindness is one of the most feared disabilities of anything, because I think people feel like it takes vision to do most things," CCB executive director Julie Deden, who's been blind since birth, told INSIDER. "But really, once people begin using their other senses, they realize you can easily do things without being able to see. "

It's true: Throughout the six- to nine-month program, ITP students learn to cook meals for 60, go shopping, read braille , use smartphones and computers, handle power tools, navigate public transit, and travel streets safely — all while living on site with fellow students.

Those who retain some residual vision are even required to wear black sleep shades like these:

This ensures they'll rely completely their other senses.

Related stories

"I found that kind of liberating," said recent CCB graduate Peter Slatin, 62, who's gradually losing his sight but still retains some visual perception. "The way I see can be very confusing. I think I know where I'm going and what I'm looking at, and my mind fools me. So by wearing sleep shades, I can't guess anymore."

All the instructors are blind, too — save one sighted wood-shop instructor who frequently wears a blindfold in class.

"H e actually had training for three months with a blindfold and learned how to do everything as a totally blind person," Deden said of the teacher. "And he stays in practice!"

A major part of the curriculum is learning hard skills.

Students practice crossing streets by listening to the flow of traffic, train on speech software that reads text messages and emails out loud, and learn to recognize the letters that make up the braille alphabet.

They also take class into the great outdoors with trips for whitewater rafting, skiing, and rock climbing.

"We weave a lot of challenge recreation into our program to challenge people, so that they know they can handle things that come up in life that might be daunting or kind of scary," Deden said.

But the most important thing students learn isn't a trick or an adaptation: It's confidence.

Some of the ITP coursework is challenging: Cane travel classes take place in the real world with traffic rushing by, and learning to read with your fingers (especially if you grew up doing it with your eyes) can be frustrating. But Deden said that the biggest struggle for most incoming ITP students is gaining confidence.

"With the students [who] have always been blind, we find that people have always said to them, 'you can’t.' So they have it kind of ingrained and we have to switch that whole mindset around for people," she said. " And then the other [students] have been losing their vision or have lost vision later on in life. And so they’ve had a lot of life experiences and all of a sudden they’re having to deal with the fact that they’re blind."

CCB cane travel instructor David Nietfeld agreed.

"A lot of people struggle with just having confidence that they can go and do things," he told INSIDER. "So w hen they first learn how to cross the street, just believing that they can go out and go do it is a lot of times challenging for people."

Slatin, who lives and works as a consultant in New York City, said attending CCB really did strengthen his belief in his own abilities.

"I'll say the biggest change is in confidence in approaching the world and representing myself as a blind person and inhabiting being blind," he said. "I used to cook, and for many years I haven't, and now I feel better able to cook. I have a guide dog, but I feel like my travel skills are better. And I learned braille, which I now see as incredibly important. I also I started out [...] as a painter, and one of the great things that happened at CCB was that I started doing artwork again, focusing on non-visual art, tactile art, in a serious way."

The ITP has grown considerably since its inception.

Back in 1988, the program had 5 students and three instructors. Today, Deden said, there are dozens of staff and as many as 35 students per session.

Each crop of students graduates with the skills to prove that blindness doesn't equal dependence on others — not by a long shot.

"People don't understand how much we can do and how much we want to do for ourselves," Slatin said. " I was standing at a bus stop one day fairly recently and a woman came up to me as I was getting on the bus and she said, 'I admire you so much. I could never do what you do.' And I said, 'Actually I beg to differ with you — I'm sure you could.'"

Read more about the programs offered at the Colorado Center for the Blind on their website .

Follow INSIDER on Facebook .

Watch: An eye surgeon explains how to tell if you’re color blind

- Main content

Lesson Plan Understanding Blindness

Society holds misconceptions about the visually impaired, yet the blind can communicate well and perform skills with independent mobility, becoming productive citizens.

The term blindness can be defined across a wide spectrum. A person who is visually impaired may have difficulty performing ordinary tasks, regardless of the use of glasses and contact lenses. Blurred vision, blind spots, or tunnel vision could be some characteristics of vision impairment. Eye diseases, such as glaucoma—which causes optic nerve damage—can also cause vision loss. In 2012, the World Health Organization estimated that of the 285 million visually impaired people in the world, 39 million were officially blind. In the U.S., The National Federation for the Blind estimates that around 6.6 million Americans are currently living with a visual disability. The total number of legally blind students, ages 16 and up, enrolled in high schools in the U.S. is over 60,000.*

This photo essay depicts lives of the sightless, including both the blind and visually impaired, in New York City. Some of the people highlighted in the photo essay include a blind employment lawyer, a computer teacher, a karate teacher for the visually impaired, and a waiter at a restaurant in midtown Manhattan. Some of the individuals face employer inequalities as well as various discriminations based on social misconceptions of blindness.

Connections to National Standards

Common Core English Language Arts. SL.11-12.1.c. Propel conversations by posing and responding to questions that probe reasoning and evidence; ensure a hearing for a full range of positions on a topic or issue; clarify, verify, or challenge ideas and conclusions; and promote divergent and creative perspectives.

College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies. D2.Civ.7.9-12. Apply civic virtues and democratic principles when working with others.

Next Generation Science Standards. HS-LS2-8. Evaluate the evidence for the role of group behavior on individual and species' chances to survive and reproduce.

Setting the Stage

Introduce the photo essay by asking students if anyone knows a blind person. Explain that students will be looking at a photo essay that shows the lives of the sightless and the visually impaired in New York City. Ask students what it could be like to navigate the world with disabilities, such as being blind, deaf, or a wheelchair user. What could be some qualities that a person with one of these disabilities could gain? What could be some qualities they could lose?

Introduce the following myths about blindness, asking these questions:

- Blind people see only darkness.* (False) Only 18 percent of people who are visually impaired are totally blind.

- People who are blind cannot read printed materials.* (False) Technology has enabled various kinds of print accessible. Screens and texts can become magnified and enlarged.

- People who are blind have special gifts, or a "sixth sense." * (False) Blind people rely on their senses of touch, hearing, taste, or smell, which become sharper to compensate for their loss of vision.

Engaging with the Story

Direct students to view the photo essay in pairs or groups of three. Invite them to look for specific details in the photos that reflect a blind person's perspective. You may want to share with students that this photo essay is an invitation to experience how a blind person might perceive the world. Some characteristics in the photographs include examples of depth perception, the ability to see light and dark, and fragmented images. Describe that some of the blind individuals highlighted in the photo essay include:

- A karate teacher

- A waiter at a restaurant in midtown Manhattan

- An employment lawyer

- A computer teacher

For most individuals, sight is how they interpret the world. People who are blind and visually impaired experience the world in different ways, relying more on their other senses such as hearing, touch, or smell.

Delving Deeper

Lead a discussion with such question as:

- Ask students what they noticed from the photo essay. What was their first impression of these photos? If there is a visually impaired student in the class, ask if he can share his experiences with the class.

- Some of the blind people featured in the photo essay include a computer teacher, an employment lawyer, a karate teacher, and a waiter. What do you think could be some physical or emotional challenges these individuals face daily at their jobs?

- One photograph features a blind waiter serving food in a pitch-black dining room at a restaurant. What could this experience provide for those who are blind and for those who are not?

- "People were scared of me," says a blind lawyer featured in the photo essay. "Many big companies refused me when their managers met me in person and realized that I was blind." Why do you think big companies are afraid to hire a sightless person? Do you think this is fair? Why or why not? What do you think could be some of society's misconceptions around blindness?

- What do you think the photographer wants us to know about people who are blind?

- If you could rename the title of this photo essay, what name would you give it?

Reflecting and Projecting

Give students one of the following reflective writing prompts to demonstrate their understanding of the story:

- Photographer Gaia Squarci said, "There is an invisible wall between the sighted and visually impaired. One of the women I interviewed has been blind since she was 4 years old. She told me sighted people are almost scared to deal with the blind. Being blind is like speaking a language. If sighted people don't find eye contact - which is the first hint of communication - they feel lost and they don't engage."* What do you think about this statement? Why might sunglasses, worn by a blind person, make a sighted person feel more comfortable? (CCSS.ELA.SL.11-12.1.c)

- The Verbal Description and Touch Tour of the 2012 Biennial at the Whitney museum, captured in the photo essay, as well as traffic lights provided with sound are ways society can enhance services for the blind. What could be some other innovative solutions to improve access to the world environment for the blind? (NGSS.HS-LS2-8)

- What are some ways the photo essay exemplifies how the blind experience the world around them? If you were a museum director creating an exhibit for the blind and visually impaired, how could you utilize these observations of the blind? What elements would you include in the exhibit? Include specifics in your design. For example, would you include an audio tour? Would there be buttons or no buttons? Do you think the exhibit is a civic responsibility—a service for blind citizens? Why or why not? (C3.D2.Civ.7.9-12)

Caroline Casey, " Caroline Casey: Looking past limits ." TED Talk, December 2010.

Rosemary Mahoney, " Why Do We Fear the Blind? " The New York Times , January 4, 2014.

Whitney Museum of American Art: Verbal Description and Touch Tours .

The Lighthouse International School .

Subject Areas

High school.

- English language arts

- Photography

National Standards

- C3.D2.Civ.7.9-12

- CCSS.ELA.SL.11-12.1.c

- NGSS.HS-LS2-8

- Social misconceptions

- Valuing diversity

- Access to the photo essay online (or printed copies of it)

Preparation

- How to use our lesson plans

- (Optional) Make copies of the photo essay

Related Lesson Plans

- What Does it Mean to Be Resilient?

- Quilting and Family Traditions in Gee’s Bend, Alabama

- Reclaiming Rivers

More to Explore

‘Curing blindness’: why we need a new perspective on sight rehabilitation

Research Fellow, University of Aberdeen

Disclosure statement

Meike Scheller's work has been carried out at the University of Bath with support from the University, the British Academy, and the NIHR.

View all partners

In a society focused on visual communication , being blind can have severe disadvantages. In fact, research shows blind people are at higher risk of unemployment , social isolation, and lower quality of life than sighted people. Given the huge impact blindness has on society and those without vision, the drive to find a “cure” for blindness has become a profitable market.

Many new, cutting-edge developments that “ cure blindness ” build on promises they often cannot keep , leaving many blind people and their families feeling disappointed and disillusioned. But what does “curing blindness” actually mean – and how can it be achieved in a way that it most benefits the blind person?

When we think of “curing blindness”, we often think about restoring the lost sense – for example, through vision-enhancing technology, bionic eyes, or gene therapy. This is because we typically treat an impaired sense by focusing on the damaged sensory organ. But while our eyes deliver the sensory input, by transforming light into electrical impulses that our brains can use, most visual perception happens in the brain .

The perception of a visual object, a coffee cup, say, is created across different hierarchical levels in the visual cortex of our brain. Simple two-dimensional features, such as edges and colours, are combined into more complex shapes, which are in turn combined into the perception of whole objects, like our coffee cup. Across these different levels, our previous visual and non-visual experiences strongly influence how we perceive the final object.

Because of the complex nature of visual perception, sight is incredibly difficult to restore, and achieving a satisfactory level of visual function is not easy. Despite significant advances in visual restoration technology , even the best visual implants typically only allow visual acuity of 1/60, which is technically still classed as blindness by the World Health Organization. While this minimal form of light perception is already great progress, it’s not enough to allow a person to live independently.

While every blind person has their own ideas of what sight rehabilitation should do for them, what resonates with most is the aim to increase independence by allowing blind people to gain more access to visual information.

But does the brain need vision for that? Not necessarily. This is why we need to adopt a different perspective on sensory rehabilitation – one that views vision as part of a greater multisensory experience. After all, perception is rarely based on one sense alone but on a combination of multisensory experiences in which our senses influence each other.

Multisensory perspective

The brain has the remarkable ability to compensate for sensory loss by reorganizing how it processes information. In fact, the brain learns to perceive through the sensory experiences it makes during childhood. If all sensory experience is non-visual, perception will develop around these experiences. So if a person was born without sight, or lost their sight early on in childhood, their perception will develop around the non-visual senses.

This is why, on some tasks, blind people perform better than sighted people, while, on other tasks, they may perform worse. This dichotomy seems to underlie a simple principle: is the sense that is typically used for this task the best suited for accessing this information? For example, we are well able to locate a buzzing phone using either our vision or hearing. In this case, more experience finding objects through sound will lead to superior performance in blind people when only hearing is used. However, given that our vision is much better suited to perceiving people’s faces, blind people usually perform worse than sighted people when recognising other’s faces through touch .

We know that the brain learns best about the environment when it can access the same information through multiple senses . This benefits our perception by enhancing accuracy and precision . But if we want to make use of this perceptual benefit in vision rehabilitation, we need to know whether the blind brain actually learned to generate it.

It turns out that this depends on the age a person goes blind. Blindness before the age of eight or nine years influences how touch and hearing are used together to estimate object size. But blindness after this age impairs the ability to enhance perception through multisensory combination.

So what does that mean for sensory rehabilitation? We know that there’s not one best solution for all, but we also know that the age of blindness-onset can provide important clues. If a person has been blind since birth or early childhood, the brain does not know how to process visual information, so vision restoration may not bring much benefit. If, however, sight was lost later in life, the brain is best wired to perceive its surroundings through vision.

But there’s still good news for the congenitally and early blind: the enhanced perceptual abilities in the remaining senses can be used to substitute vision . In fact, visual information does not have to be taken up through the eyes – it can also reach the brain through our other senses . In order for that to happen, it first needs to be translated into a different “sensory language”. For example, visual information can be directly translated into sound . Through training, the brain then learns to use this new sensory language , opening up the visual world through the use of another sense.

While sensory restoration advancements have come a long way, we are still far from an optimal solution that allows blind people to access visual information and equally partake in society. By realising that perception depends on individual experiences, we can better develop solutions that will most benefit each person – whether that aims to restore their sight, or seeks to use their other senses instead.

- Sensory perception

- Visual impairments

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Life Worlds and Social Experiences of the Blind: Lived Body, Senses and Emotion

Related Papers

Prachatip Kata

Professor David Bolt

Frames Cinema Journal

Slava Greenberg

Three short avant-garde animated films address the issues of vision disabilities and blindness: Many Happy Returns (Marjut Rimminen 1996), A Shift in Perception (Dan Monceaux 2006) and Ishihara (Yoav Brill 2010). Through the use of diverse animation techniques intensified by sound strategies all three films evoke a dream-intoxicated-like atmosphere. These shorts subvert – in form as well as content – former cinematic and cultural representations of people with vision disabilities. Thus, by providing a phenomenologically-sensual alternative, these works critique the able-bodied cinematic construction of spectatorship. I argue that these shorts offer an antidote to the social organization of vision, and above all, to the supremacy attributed to vision in the experience of spectatorship.

Stefan Sunandan Honisch

Rosie O'Connor

This dissertation advocates for the inclusivity of blind and partially sighted visitors in museum and gallery environments. Predicated on the notion that visual hegemony prevails in western culture and artistic practice, visually impaired members of society have been displaced within cultural institutions. However, identifying a sensory revolution in Western visual culture and artistic practice reconfigures art’s relationship to blindness. Drawing on two exhibitions that engage distinctly with the senses and de-value the authority of sight, this dissertation attempts to showcase how this de-centralisation of sight in favour of other sensory stimulation has the capacity to create a more inclusive environment for those that lack ocular abilities. Furthermore, this dissertation argues that sensory stimulation and blindness can enhance artistic experience for the sighted as well as the non-sighted. Thus constituting a cultural environment where disability is de-stigmatised.

Ethnography and Education

Dr Ceri Morris

Russell Shuttleworth

The Sociological Quarterly

Asia Friedman

Encyclopedia of medical anthropology

Kent Fitzsimons

Accessibility considerations tend to dominate discussions about disability and the built environment. While many architects object to the constraints of accessibility regulations, the shallow ramps, wide passages and spatial continuity typical of barrier-free design are not foreign to architectural discourse. They rather mesh effortlessly with architecture’s longstanding preoccupation with movement. Unfortunately, the proximity between architectural discourse’s focus on mobile experiences and the demands of disability activists distracts from considering other relationships between architecture and the human body. This article explores the similarities and differences between mobility disabilities and sensory disabilities and proposes the notion of “perceiving otherwise” in order to reconsider how architectural space may be conceptualized. It discusses that notion through readings of selected contemporary architectural works, including Rem Koolhaas’s Bordeaux House (1998) and Peter Eisenman’s Memorial to the Murdered European Jews in Berlin (2005).

RELATED PAPERS

Teodor Mladenov

Tanya Titchkosky

Tourism Management

Tanya Packer , Simon Darcy

Jennie Small

Annals of Tourism Research

Nigel Morgan

AIBR, Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana

Carlos García Grados

The Senses and Society

Elizabeth Davis

Sociology Compass

Jennifer C Mueller

Annelies Kusters

Catalin Brylla

Bruno Sena Martins

Word and Text: A Journal of Literary Studies and Linguistics

Arleen Ionescu , Anne-Marie Callus

Michael Schillmeier

Etnografia. Praktyki, Teorie, Doświadczenia

Kamil Pietrowiak

Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies 9.1

Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies

Jill Anderson

gammathetaupsilon.org

Joshua Inwood

JulianFernando TrujilloAmaya

Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology

Michele Friedner , Stefan Helmreich

sumonmarn singha

Mingshan Liu

Anthropology & Education Quarterly

Herve Varenne

Moritz Ingwersen , Anne Waldschmidt

D.A. Caeton

Alice Wexler

American Literary History, 2013

Erica Fretwell

Sites: a Journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies

Martha Bell

Studies in East European Thought

Irina Sandomirskaja

'Distress or Disability', based on symposium at Lancaster University, 15-16th November 2011.

China Mills

Bernhard Hadolt , Anita Hardon

Jason Throop

CITIZENSHIP STUDIES

Maja de Langen

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

My Experience as a Blind Child

By: Rocky Hart

(Editor’s Note: In this year’s essay contest, sponsored by our Metro Chapter, we had a tie for first place. This was one of our winning essays. It’s exciting to see teens participating in our contest. Since writing this piece, Rocky has joined the Federation!)

“So, what is it like to be blind or visually impaired, and how can you live a productive and independent life?” I know many blind people have probably been asked this question on numerous occasions. Or perhaps, “What has your experience been as a blind or visually impaired person?” As I am well aware, many people who are blind have different stories to tell. Some, like myself, have been blind from birth, while others became blind later in life. We all have had different experiences, and, as I look back on my own childhood, I have had both positive and negative encounters. I believe it is critically important to share our experiences not only with other blind people, but also with the general public, as there are many misconceptions, false assumptions, and superstitions among the sighted population about what blind people are capable of doing, what we can understand, and how we live our daily lives. Although consumer organizations like the National Federation of the Blind, American Council of the Blind, and American Foundation for the blind exist to promote a positive outlook on this disability as well as challenge common misconceptions and superstitions about it, not all of this has been eliminated. In my experience, blindness has been viewed as either something that makes me unique, or a disability that limits what I am capable of. As I reflect back on my childhood, I vividly remember at least one experience of both. This experience started with my parents.

When I was about 4 months old, I was diagnosed with Norries Disease, the condition that caused my blindness. My mother was determined to at least attempt to cure my blindness and restore my vision. I traveled to Michigan when I was about 6 months old to undergo a procedure that doctors hoped would restore my vision. When the operation was unsuccessful, my mother wondered why she had a blind child. She waited 10 years for a child, survived a very rigorous 31-week pregnancy, and now her child has a disability. How could this be? None of this, however, stopped her from providing the best life she could for me. She refused to feel sorry for me, and was frustrated by people of the general public who did. She always had high expectations for me and, despite my disabilities, was determined to raise a strong, competent, confident, independent child. In order to accomplish this, however, she knew she would need to make appropriate accommodations for me. For this reason, I began receiving special education services when I was an infant, and both my education team and mother have taken time to teach me basic life skills, as well as working on learning things like braille, orientation and mobility, and other instruction I would need to ensure I had a successful life and education. My father, however, had a very different approach.

Although he knew I could live a productive and independent life, he didn’t know exactly how to provide it. When he learned the operation on my eyes was not successful, he was disappointed because he says he wanted to raise me to become a good hunter and fisher, and then eventually start a father-son tree removal business, and now, in his mind, that plan wouldn’t work. I personally believe this plan not working had nothing to do with my blindness, and everything to do with God having a different plan for my life. Because of my blindness, he has always assumed that I need “special” treatment and was limited in what I could do. For example, when we would go to a restaurant, he would assume I needed special seating arrangements because I was blind, or that I need assistance with simple tasks, such as putting on my own seatbelt, nearly on the grounds that I was blind. Although I still need assistance, to this day, to complete certain daily tasks, what my father thought was helping me was actually hindering my chance to become independent. I thank God that my mother has been in my life and has raised me to be productive and independent. I believe that if my father had raised me, my life would have been significantly different because I may have been raised in a bubble, due to him not having the right ideas, approaches, and accommodations for my blindness in mind. This became more evident to me after my parents' divorce, because they would occasionally argue about how to raise me effectively. Fortunately, when my stepfather came into my life upon my parents' divorce at age 5, he accepted my blindness, and treats me like his own son, and has truly become a father figure for me over the past 9 years, and he and my mother have done everything they could to give me a successful life and education. These experiences also occurred at certain times in school.

As I advanced through elementary school, I had both positive and negative experiences. Some of my teachers and several other staff at the school automatically assumed that because I was blind, I was limited in what I could do. Some of my peers were afraid to socialize with me, because they didn’t think I could understand them or, perhaps, because I was blind, were concerned I wasn’t able to interact with them. Part of this problem was also due to me being more withdrawn than my peers. Despite this, many teachers and students treated me like any other student, allowing and encouraging me to participate in activities, and my special education team insured I had appropriate accommodations. I was receiving instruction in braille and audio formats, orientation and mobility services, learned how to use various kinds of adaptive technology, and even learned some daily living skills. It seemed as if I had what I needed to complete a quality education. Even so, it was thought that I couldn’t participate in certain educational and extracurricular activities, and in some cases, I was pulled out of certain classes because of my blindness. Art was one example.

I attended art classes up until fourth grade. At that point, my special Education team believed it was in my best interest to pull me out of art class because they didn’t think I could keep up with my peers, partly due to my blindness, because art involved a lot of drawing and painting, and there were concerns from both the art instructor and my education team that I would fall behind in the curriculum. We couldn’t find any other solutions, so I would have to be pulled out, and honestly, I didn’t mind at that time. As I reflect on it, However, I can use that as an example of a misconception, even though pulling me out of the class was in my best interest.

One positive experience I had in public school, however, was in physical education class. For the first few months of first grade physical education, it was clear that I couldn’t keep up physically and at the skill levels of my peers. Instead of pulling me out of phy. ed. completely, I was enrolled in Disability Adapted Physical Education, (DAPE). Although the curriculum was modified, it still allowed me to participate in the class. I even became a part of the Special Olympics team for about the last 4 years I was in public school.