10 Grounded Theory Examples (Qualitative Research Method)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Grounded theory is a qualitative research method that involves the construction of theory from data rather than testing theories through data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In other words, a grounded theory analysis doesn’t start with a hypothesis or theoretical framework, but instead generates a theory during the data analysis process .

This method has garnered a notable amount of attention since its inception in the 1960s by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

Grounded Theory Definition and Overview

A central feature of grounded theory is the continuous interplay between data collection and analysis (Bringer, Johnston, & Brackenridge, 2016).

Grounded theorists start with the data, coding and considering each piece of collected information (for instance, behaviors collected during a psychological study).

As more information is collected, the researcher can reflect upon the data in an ongoing cycle where data informs an ever-growing and evolving theory (Mills, Bonner & Francis, 2017).

As such, the researcher isn’t tied to testing a hypothesis, but instead, can allow surprising and intriguing insights to emerge from the data itself.

Applications of grounded theory are widespread within the field of social sciences . The method has been utilized to provide insight into complex social phenomena such as nursing, education, and business management (Atkinson, 2015).

Grounded theory offers a sound methodology to unearth the complexities of social phenomena that aren’t well-understood in existing theories (McGhee, Marland & Atkinson, 2017).

While the methods of grounded theory can be labor-intensive and time-consuming, the rich, robust theories this approach produces make it a valuable tool in many researchers’ repertoires.

Real-Life Grounded Theory Examples

Title: A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology

Citation: Weatherall, J. W. A. (2000). A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology. Educational Gerontology , 26 (4), 371-386.

Description: This study employed a grounded theory approach to investigate older adults’ use of information technology (IT). Six participants from a senior senior were interviewed about their experiences and opinions regarding computer technology. Consistent with a grounded theory angle, there was no hypothesis to be tested. Rather, themes emerged out of the analysis process. From this, the findings revealed that the participants recognized the importance of IT in modern life, which motivated them to explore its potential. Positive attitudes towards IT were developed and reinforced through direct experience and personal ownership of technology.

Title: A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study

Citation: Jacobson, N. (2009). A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study. BMC International health and human rights , 9 (1), 1-9.

Description: This study aims to develop a taxonomy of dignity by letting the data create the taxonomic categories, rather than imposing the categories upon the analysis. The theory emerged from the textual and thematic analysis of 64 interviews conducted with individuals marginalized by health or social status , as well as those providing services to such populations and professionals working in health and human rights. This approach identified two main forms of dignity that emerged out of the data: “ human dignity ” and “social dignity”.

Title: A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose

Citation: Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research , 27 (1), 78-109.

Description: This study explores the development of noble youth purpose over time using a grounded theory approach. Something notable about this study was that it returned to collect additional data two additional times, demonstrating how grounded theory can be an interactive process. The researchers conducted three waves of interviews with nine adolescents who demonstrated strong commitments to various noble purposes. The findings revealed that commitments grew slowly but steadily in response to positive feedback, with mentors and like-minded peers playing a crucial role in supporting noble purposes.

Title: A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users

Citation: Pace, S. (2004). A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users. International journal of human-computer studies , 60 (3), 327-363.

Description: This study attempted to understand the flow experiences of web users engaged in information-seeking activities, systematically gathering and analyzing data from semi-structured in-depth interviews with web users. By avoiding preconceptions and reviewing the literature only after the theory had emerged, the study aimed to develop a theory based on the data rather than testing preconceived ideas. The study identified key elements of flow experiences, such as the balance between challenges and skills, clear goals and feedback, concentration, a sense of control, a distorted sense of time, and the autotelic experience.

Title: Victimising of school bullying: a grounded theory

Citation: Thornberg, R., Halldin, K., Bolmsjö, N., & Petersson, A. (2013). Victimising of school bullying: A grounded theory. Research Papers in Education , 28 (3), 309-329.

Description: This study aimed to investigate the experiences of individuals who had been victims of school bullying and understand the effects of these experiences, using a grounded theory approach. Through iterative coding of interviews, the researchers identify themes from the data without a pre-conceived idea or hypothesis that they aim to test. The open-minded coding of the data led to the identification of a four-phase process in victimizing: initial attacks, double victimizing, bullying exit, and after-effects of bullying. The study highlighted the social processes involved in victimizing, including external victimizing through stigmatization and social exclusion, as well as internal victimizing through self-isolation, self-doubt, and lingering psychosocial issues.

Hypothetical Grounded Theory Examples

Suggested Title: “Understanding Interprofessional Collaboration in Emergency Medical Services”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Coding and constant comparative analysis

How to Do It: This hypothetical study might begin with conducting in-depth interviews and field observations within several emergency medical teams to collect detailed narratives and behaviors. Multiple rounds of coding and categorizing would be carried out on this raw data, consistently comparing new information with existing categories. As the categories saturate, relationships among them would be identified, with these relationships forming the basis of a new theory bettering our understanding of collaboration in emergency settings. This iterative process of data collection, analysis, and theory development, continually refined based on fresh insights, upholds the essence of a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “The Role of Social Media in Political Engagement Among Young Adults”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Open, axial, and selective coding

Explanation: The study would start by collecting interaction data on various social media platforms, focusing on political discussions engaged in by young adults. Through open, axial, and selective coding, the data would be broken down, compared, and conceptualized. New insights and patterns would gradually form the basis of a theory explaining the role of social media in shaping political engagement, with continuous refinement informed by the gathered data. This process embodies the recursive essence of the grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Transforming Workplace Cultures: An Exploration of Remote Work Trends”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Constant comparative analysis

Explanation: The theoretical study could leverage survey data and in-depth interviews of employees and bosses engaging in remote work to understand the shifts in workplace culture. Coding and constant comparative analysis would enable the identification of core categories and relationships among them. Sustainability and resilience through remote ways of working would be emergent themes. This constant back-and-forth interplay between data collection, analysis, and theory formation aligns strongly with a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Persistence Amidst Challenges: A Grounded Theory Approach to Understanding Resilience in Urban Educators”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Iterative Coding

How to Do It: This study would involve collecting data via interviews from educators in urban school systems. Through iterative coding, data would be constantly analyzed, compared, and categorized to derive meaningful theories about resilience. The researcher would constantly return to the data, refining the developing theory with every successive interaction. This procedure organically incorporates the grounded theory approach’s characteristic iterative nature.

Suggested Title: “Coping Strategies of Patients with Chronic Pain: A Grounded Theory Study”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Line-by-line inductive coding

How to Do It: The study might initiate with in-depth interviews of patients who’ve experienced chronic pain. Line-by-line coding, followed by memoing, helps to immerse oneself in the data, utilizing a grounded theory approach to map out the relationships between categories and their properties. New rounds of interviews would supplement and refine the emergent theory further. The subsequent theory would then be a detailed, data-grounded exploration of how patients cope with chronic pain.

Grounded theory is an innovative way to gather qualitative data that can help introduce new thoughts, theories, and ideas into academic literature. While it has its strength in allowing the “data to do the talking”, it also has some key limitations – namely, often, it leads to results that have already been found in the academic literature. Studies that try to build upon current knowledge by testing new hypotheses are, in general, more laser-focused on ensuring we push current knowledge forward. Nevertheless, a grounded theory approach is very useful in many circumstances, revealing important new information that may not be generated through other approaches. So, overall, this methodology has great value for qualitative researchers, and can be extremely useful, especially when exploring specific case study projects . I also find it to synthesize well with action research projects .

Atkinson, P. (2015). Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: Valid qualitative research strategies for educators. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 6 (1), 83-86.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . London: Sage.

Bringer, J. D., Johnston, L. H., & Brackenridge, C. H. (2016). Using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software to develop a grounded theory project. Field Methods, 18 (3), 245-266.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . Sage publications.

McGhee, G., Marland, G. R., & Atkinson, J. (2017). Grounded theory research: Literature reviewing and reflexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29 (3), 654-663.

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2017). Adopting a Constructivist Approach to Grounded Theory: Implications for Research Design. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 13 (2), 81-89.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Med

Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers

Ylona chun tie.

1 Nursing and Midwifery, College of Healthcare Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

Melanie Birks

Karen francis.

2 College of Health and Medicine, University of Tasmania, Australia, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Background:

Grounded theory is a well-known methodology employed in many research studies. Qualitative and quantitative data generation techniques can be used in a grounded theory study. Grounded theory sets out to discover or construct theory from data, systematically obtained and analysed using comparative analysis. While grounded theory is inherently flexible, it is a complex methodology. Thus, novice researchers strive to understand the discourse and the practical application of grounded theory concepts and processes.

The aim of this article is to provide a contemporary research framework suitable to inform a grounded theory study.

This article provides an overview of grounded theory illustrated through a graphic representation of the processes and methods employed in conducting research using this methodology. The framework is presented as a diagrammatic representation of a research design and acts as a visual guide for the novice grounded theory researcher.

Discussion:

As grounded theory is not a linear process, the framework illustrates the interplay between the essential grounded theory methods and iterative and comparative actions involved. Each of the essential methods and processes that underpin grounded theory are defined in this article.

Conclusion:

Rather than an engagement in philosophical discussion or a debate of the different genres that can be used in grounded theory, this article illustrates how a framework for a research study design can be used to guide and inform the novice nurse researcher undertaking a study using grounded theory. Research findings and recommendations can contribute to policy or knowledge development, service provision and can reform thinking to initiate change in the substantive area of inquiry.

Introduction

The aim of all research is to advance, refine and expand a body of knowledge, establish facts and/or reach new conclusions using systematic inquiry and disciplined methods. 1 The research design is the plan or strategy researchers use to answer the research question, which is underpinned by philosophy, methodology and methods. 2 Birks 3 defines philosophy as ‘a view of the world encompassing the questions and mechanisms for finding answers that inform that view’ (p. 18). Researchers reflect their philosophical beliefs and interpretations of the world prior to commencing research. Methodology is the research design that shapes the selection of, and use of, particular data generation and analysis methods to answer the research question. 4 While a distinction between positivist research and interpretivist research occurs at the paradigm level, each methodology has explicit criteria for the collection, analysis and interpretation of data. 2 Grounded theory (GT) is a structured, yet flexible methodology. This methodology is appropriate when little is known about a phenomenon; the aim being to produce or construct an explanatory theory that uncovers a process inherent to the substantive area of inquiry. 5 – 7 One of the defining characteristics of GT is that it aims to generate theory that is grounded in the data. The following section provides an overview of GT – the history, main genres and essential methods and processes employed in the conduct of a GT study. This summary provides a foundation for a framework to demonstrate the interplay between the methods and processes inherent in a GT study as presented in the sections that follow.

Glaser and Strauss are recognised as the founders of grounded theory. Strauss was conversant in symbolic interactionism and Glaser in descriptive statistics. 8 – 10 Glaser and Strauss originally worked together in a study examining the experience of terminally ill patients who had differing knowledge of their health status. Some of these suspected they were dying and tried to confirm or disconfirm their suspicions. Others tried to understand by interpreting treatment by care providers and family members. Glaser and Strauss examined how the patients dealt with the knowledge they were dying and the reactions of healthcare staff caring for these patients. Throughout this collaboration, Glaser and Strauss questioned the appropriateness of using a scientific method of verification for this study. During this investigation, they developed the constant comparative method, a key element of grounded theory, while generating a theory of dying first described in Awareness of Dying (1965). The constant comparative method is deemed an original way of organising and analysing qualitative data.

Glaser and Strauss subsequently went on to write The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (1967). This seminal work explained how theory could be generated from data inductively. This process challenged the traditional method of testing or refining theory through deductive testing. Grounded theory provided an outlook that questioned the view of the time that quantitative methodology is the only valid, unbiased way to determine truths about the world. 11 Glaser and Strauss 5 challenged the belief that qualitative research lacked rigour and detailed the method of comparative analysis that enables the generation of theory. After publishing The Discovery of Grounded Theory , Strauss and Glaser went on to write independently, expressing divergent viewpoints in the application of grounded theory methods.

Glaser produced his book Theoretical Sensitivity (1978) and Strauss went on to publish Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists (1987). Strauss and Corbin’s 12 publication Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques resulted in a rebuttal by Glaser 13 over their application of grounded theory methods. However, philosophical perspectives have changed since Glaser’s positivist version and Strauss and Corbin’s post-positivism stance. 14 Grounded theory has since seen the emergence of additional philosophical perspectives that have influenced a change in methodological development over time. 15

Subsequent generations of grounded theorists have positioned themselves along a philosophical continuum, from Strauss and Corbin’s 12 theoretical perspective of symbolic interactionism, through to Charmaz’s 16 constructivist perspective. However, understanding how to position oneself philosophically can challenge novice researchers. Birks and Mills 6 provide a contemporary understanding of GT in their book Grounded theory: A Practical Guide. These Australian researchers have written in a way that appeals to the novice researcher. It is the contemporary writing, the way Birks and Mills present a non-partisan approach to GT that support the novice researcher to understand the philosophical and methodological concepts integral in conducting research. The development of GT is important to understand prior to selecting an approach that aligns with the researcher’s philosophical position and the purpose of the research study. As the research progresses, seminal texts are referred back to time and again as understanding of concepts increases, much like the iterative processes inherent in the conduct of a GT study.

Genres: traditional, evolved and constructivist grounded theory

Grounded theory has several distinct methodological genres: traditional GT associated with Glaser; evolved GT associated with Strauss, Corbin and Clarke; and constructivist GT associated with Charmaz. 6 , 17 Each variant is an extension and development of the original GT by Glaser and Strauss. The first of these genres is known as traditional or classic GT. Glaser 18 acknowledged that the goal of traditional GT is to generate a conceptual theory that accounts for a pattern of behaviour that is relevant and problematic for those involved. The second genre, evolved GT, is founded on symbolic interactionism and stems from work associated with Strauss, Corbin and Clarke. Symbolic interactionism is a sociological perspective that relies on the symbolic meaning people ascribe to the processes of social interaction. Symbolic interactionism addresses the subjective meaning people place on objects, behaviours or events based on what they believe is true. 19 , 20 Constructivist GT, the third genre developed and explicated by Charmaz, a symbolic interactionist, has its roots in constructivism. 8 , 16 Constructivist GT’s methodological underpinnings focus on how participants’ construct meaning in relation to the area of inquiry. 16 A constructivist co-constructs experience and meanings with participants. 21 While there are commonalities across all genres of GT, there are factors that distinguish differences between the approaches including the philosophical position of the researcher; the use of literature; and the approach to coding, analysis and theory development. Following on from Glaser and Strauss, several versions of GT have ensued.

Grounded theory represents both a method of inquiry and a resultant product of that inquiry. 7 , 22 Glaser and Holton 23 define GT as ‘a set of integrated conceptual hypotheses systematically generated to produce an inductive theory about a substantive area’ (p. 43). Strauss and Corbin 24 define GT as ‘theory that was derived from data, systematically gathered and analysed through the research process’ (p. 12). The researcher ‘begins with an area of study and allows the theory to emerge from the data’ (p. 12). Charmaz 16 defines GT as ‘a method of conducting qualitative research that focuses on creating conceptual frameworks or theories through building inductive analysis from the data’ (p. 187). However, Birks and Mills 6 refer to GT as a process by which theory is generated from the analysis of data. Theory is not discovered; rather, theory is constructed by the researcher who views the world through their own particular lens.

Research process

Before commencing any research study, the researcher must have a solid understanding of the research process. A well-developed outline of the study and an understanding of the important considerations in designing and undertaking a GT study are essential if the goals of the research are to be achieved. While it is important to have an understanding of how a methodology has developed, in order to move forward with research, a novice can align with a grounded theorist and follow an approach to GT. Using a framework to inform a research design can be a useful modus operandi.

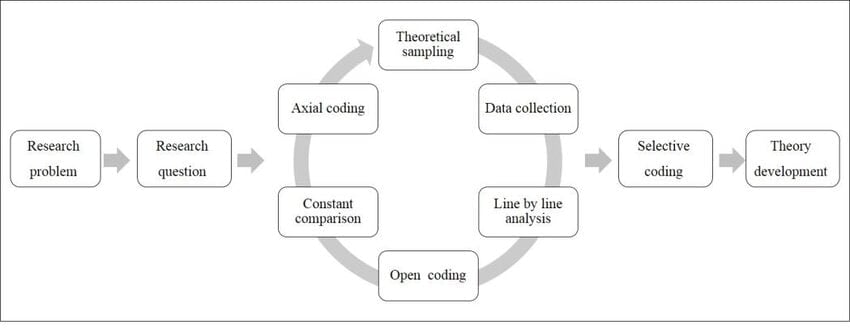

The following section provides insight into the process of undertaking a GT research study. Figure 1 is a framework that summarises the interplay and movement between methods and processes that underpin the generation of a GT. As can be seen from this framework, and as detailed in the discussion that follows, the process of doing a GT research study is not linear, rather it is iterative and recursive.

Research design framework: summary of the interplay between the essential grounded theory methods and processes.

Grounded theory research involves the meticulous application of specific methods and processes. Methods are ‘systematic modes, procedures or tools used for collection and analysis of data’. 25 While GT studies can commence with a variety of sampling techniques, many commence with purposive sampling, followed by concurrent data generation and/or collection and data analysis, through various stages of coding, undertaken in conjunction with constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling and memoing. Theoretical sampling is employed until theoretical saturation is reached. These methods and processes create an unfolding, iterative system of actions and interactions inherent in GT. 6 , 16 The methods interconnect and inform the recurrent elements in the research process as shown by the directional flow of the arrows and the encompassing brackets in Figure 1 . The framework denotes the process is both iterative and dynamic and is not one directional. Grounded theory methods are discussed in the following section.

Purposive sampling

As presented in Figure 1 , initial purposive sampling directs the collection and/or generation of data. Researchers purposively select participants and/or data sources that can answer the research question. 5 , 7 , 16 , 21 Concurrent data generation and/or data collection and analysis is fundamental to GT research design. 6 The researcher collects, codes and analyses this initial data before further data collection/generation is undertaken. Purposeful sampling provides the initial data that the researcher analyses. As will be discussed, theoretical sampling then commences from the codes and categories developed from the first data set. Theoretical sampling is used to identify and follow clues from the analysis, fill gaps, clarify uncertainties, check hunches and test interpretations as the study progresses.

Constant comparative analysis

Constant comparative analysis is an analytical process used in GT for coding and category development. This process commences with the first data generated or collected and pervades the research process as presented in Figure 1 . Incidents are identified in the data and coded. 6 The initial stage of analysis compares incident to incident in each code. Initial codes are then compared to other codes. Codes are then collapsed into categories. This process means the researcher will compare incidents in a category with previous incidents, in both the same and different categories. 5 Future codes are compared and categories are compared with other categories. New data is then compared with data obtained earlier during the analysis phases. This iterative process involves inductive and deductive thinking. 16 Inductive, deductive and abductive reasoning can also be used in data analysis. 26

Constant comparative analysis generates increasingly more abstract concepts and theories through inductive processes. 16 In addition, abduction, defined as ‘a form of reasoning that begins with an examination of the data and the formation of a number of hypotheses that are then proved or disproved during the process of analysis … aids inductive conceptualization’. 6 Theoretical sampling coupled with constant comparative analysis raises the conceptual levels of data analysis and directs ongoing data collection or generation. 6

The constant comparative technique is used to find consistencies and differences, with the aim of continually refining concepts and theoretically relevant categories. This continual comparative iterative process that encompasses GT research sets it apart from a purely descriptive analysis. 8

Memo writing is an analytic process considered essential ‘in ensuring quality in grounded theory’. 6 Stern 27 offers the analogy that if data are the building blocks of the developing theory, then memos are the ‘mortar’ (p. 119). Memos are the storehouse of ideas generated and documented through interacting with data. 28 Thus, memos are reflective interpretive pieces that build a historic audit trail to document ideas, events and the thought processes inherent in the research process and developing thinking of the analyst. 6 Memos provide detailed records of the researchers’ thoughts, feelings and intuitive contemplations. 6

Lempert 29 considers memo writing crucial as memos prompt researchers to analyse and code data and develop codes into categories early in the coding process. Memos detail why and how decisions made related to sampling, coding, collapsing of codes, making of new codes, separating codes, producing a category and identifying relationships abstracted to a higher level of analysis. 6 Thus, memos are informal analytic notes about the data and the theoretical connections between categories. 23 Memoing is an ongoing activity that builds intellectual assets, fosters analytic momentum and informs the GT findings. 6 , 10

Generating/collecting data

A hallmark of GT is concurrent data generation/collection and analysis. In GT, researchers may utilise both qualitative and quantitative data as espoused by Glaser’s dictum; ‘all is data’. 30 While interviews are a common method of generating data, data sources can include focus groups, questionnaires, surveys, transcripts, letters, government reports, documents, grey literature, music, artefacts, videos, blogs and memos. 9 Elicited data are produced by participants in response to, or directed by, the researcher whereas extant data includes data that is already available such as documents and published literature. 6 , 31 While this is one interpretation of how elicited data are generated, other approaches to grounded theory recognise the agency of participants in the co-construction of data with the researcher. The relationship the researcher has with the data, how it is generated and collected, will determine the value it contributes to the development of the final GT. 6 The significance of this relationship extends into data analysis conducted by the researcher through the various stages of coding.

Coding is an analytical process used to identify concepts, similarities and conceptual reoccurrences in data. Coding is the pivotal link between collecting or generating data and developing a theory that explains the data. Charmaz 10 posits,

codes rely on interaction between researchers and their data. Codes consist of short labels that we construct as we interact with the data. Something kinaesthetic occurs when we are coding; we are mentally and physically active in the process. (p. 5)

In GT, coding can be categorised into iterative phases. Traditional, evolved and constructivist GT genres use different terminology to explain each coding phase ( Table 1 ).

Comparison of coding terminology in traditional, evolved and constructivist grounded theory.

| Grounded theory genre | Coding terminology | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Intermediate | Advanced | |

| Traditional | Open coding | Selective coding | Theoretical coding |

| Evolved | Open coding | Axial coding | Selective coding |

| Constructivist | Initial coding | Focused coding | Theoretical coding |

Adapted from Birks and Mills. 6

Coding terminology in evolved GT refers to open (a procedure for developing categories of information), axial (an advanced procedure for interconnecting the categories) and selective coding (procedure for building a storyline from core codes that connects the categories), producing a discursive set of theoretical propositions. 6 , 12 , 32 Constructivist grounded theorists refer to initial, focused and theoretical coding. 9 Birks and Mills 6 use the terms initial, intermediate and advanced coding that link to low, medium and high-level conceptual analysis and development. The coding terms devised by Birks and Mills 6 were used for Figure 1 ; however, these can be altered to reflect the coding terminology used in the respective GT genres selected by the researcher.

Initial coding

Initial coding of data is the preliminary step in GT data analysis. 6 , 9 The purpose of initial coding is to start the process of fracturing the data to compare incident to incident and to look for similarities and differences in beginning patterns in the data. In initial coding, the researcher inductively generates as many codes as possible from early data. 16 Important words or groups of words are identified and labelled. In GT, codes identify social and psychological processes and actions as opposed to themes. Charmaz 16 emphasises keeping codes as similar to the data as possible and advocates embedding actions in the codes in an iterative coding process. Saldaña 33 agrees that codes that denote action, which he calls process codes, can be used interchangeably with gerunds (verbs ending in ing ). In vivo codes are often verbatim quotes from the participants’ words and are often used as the labels to capture the participant’s words as representative of a broader concept or process in the data. 6 Table 1 reflects variation in the terminology of codes used by grounded theorists.

Initial coding categorises and assigns meaning to the data, comparing incident-to-incident, labelling beginning patterns and beginning to look for comparisons between the codes. During initial coding, it is important to ask ‘what is this data a study of’. 18 What does the data assume, ‘suggest’ or ‘pronounce’ and ‘from whose point of view’ does this data come, whom does it represent or whose thoughts are they?. 16 What collectively might it represent? The process of documenting reactions, emotions and related actions enables researchers to explore, challenge and intensify their sensitivity to the data. 34 Early coding assists the researcher to identify the direction for further data gathering. After initial analysis, theoretical sampling is employed to direct collection of additional data that will inform the ‘developing theory’. 9 Initial coding advances into intermediate coding once categories begin to develop.

Theoretical sampling

The purpose of theoretical sampling is to allow the researcher to follow leads in the data by sampling new participants or material that provides relevant information. As depicted in Figure 1 , theoretical sampling is central to GT design, aids the evolving theory 5 , 7 , 16 and ensures the final developed theory is grounded in the data. 9 Theoretical sampling in GT is for the development of a theoretical category, as opposed to sampling for population representation. 10 Novice researchers need to acknowledge this difference if they are to achieve congruence within the methodology. Birks and Mills 6 define theoretical sampling as ‘the process of identifying and pursuing clues that arise during analysis in a grounded theory study’ (p. 68). During this process, additional information is sought to saturate categories under development. The analysis identifies relationships, highlights gaps in the existing data set and may reveal insight into what is not yet known. The exemplars in Box 1 highlight how theoretical sampling led to the inclusion of further data.

Examples of theoretical sampling.

| In Chamberlain-Salaun GT study, ‘the initial purposive round of concurrent data generation and analysis generated codes around concepts of physical disability and how a person’s health condition influences the way experts interact with consumers. Based on initial codes and concepts the researcher decided to theoretically sample people with disabilities and or carers/parents of children with disabilities to pursue the concepts further’ (p. 77). In Edwards grounded theory study, theoretical sampling led to the inclusion of the partners of women who had presented to the emergency department. ‘In one interview a woman spoke of being aware that the ED staff had not acknowledged her partner. This statement led me to ask other women during their interviews if they had similar experiences, and ultimately to interview the partners to gain their perspectives. The study originally intended to only focus on the women and the nursing staff who provided the care’ (p. 50). |

Thus, theoretical sampling is used to focus and generate data to feed the iterative process of continual comparative analysis of the data. 6

Intermediate coding

Intermediate coding, identifying a core category, theoretical data saturation, constant comparative analysis, theoretical sensitivity and memoing occur in the next phase of the GT process. 6 Intermediate coding builds on the initial coding phase. Where initial coding fractures the data, intermediate coding begins to transform basic data into more abstract concepts allowing the theory to emerge from the data. During this analytic stage, a process of reviewing categories and identifying which ones, if any, can be subsumed beneath other categories occurs and the properties or dimension of the developed categories are refined. Properties refer to the characteristics that are common to all the concepts in the category and dimensions are the variations of a property. 37

At this stage, a core category starts to become evident as developed categories form around a core concept; relationships are identified between categories and the analysis is refined. Birks and Mills 6 affirm that diagramming can aid analysis in the intermediate coding phase. Grounded theorists interact closely with the data during this phase, continually reassessing meaning to ascertain ‘what is really going on’ in the data. 30 Theoretical saturation ensues when new data analysis does not provide additional material to existing theoretical categories, and the categories are sufficiently explained. 6

Advanced coding

Birks and Mills 6 described advanced coding as the ‘techniques used to facilitate integration of the final grounded theory’ (p. 177). These authors promote storyline technique (described in the following section) and theoretical coding as strategies for advancing analysis and theoretical integration. Advanced coding is essential to produce a theory that is grounded in the data and has explanatory power. 6 During the advanced coding phase, concepts that reach the stage of categories will be abstract, representing stories of many, reduced into highly conceptual terms. The findings are presented as a set of interrelated concepts as opposed to presenting themes. 28 Explanatory statements detail the relationships between categories and the central core category. 28

Storyline is a tool that can be used for theoretical integration. Birks and Mills 6 define storyline as ‘a strategy for facilitating integration, construction, formulation, and presentation of research findings through the production of a coherent grounded theory’ (p. 180). Storyline technique is first proposed with limited attention in Basics of Qualitative Research by Strauss and Corbin 12 and further developed by Birks et al. 38 as a tool for theoretical integration. The storyline is the conceptualisation of the core category. 6 This procedure builds a story that connects the categories and produces a discursive set of theoretical propositions. 24 Birks and Mills 6 contend that storyline can be ‘used to produce a comprehensive rendering of your grounded theory’ (p. 118). Birks et al. 38 had earlier concluded, ‘storyline enhances the development, presentation and comprehension of the outcomes of grounded theory research’ (p. 405). Once the storyline is developed, the GT is finalised using theoretical codes that ‘provide a framework for enhancing the explanatory power of the storyline and its potential as theory’. 6 Thus, storyline is the explication of the theory.

Theoretical coding occurs as the final culminating stage towards achieving a GT. 39 , 40 The purpose of theoretical coding is to integrate the substantive theory. 41 Saldaña 40 states, ‘theoretical coding integrates and synthesises the categories derived from coding and analysis to now create a theory’ (p. 224). Initial coding fractures the data while theoretical codes ‘weave the fractured story back together again into an organized whole theory’. 18 Advanced coding that integrates extant theory adds further explanatory power to the findings. 6 The examples in Box 2 describe the use of storyline as a technique.

Writing the storyline.

| Baldwin describes in her GT study how ‘the process of writing the storyline allowed in-depth descriptions of the categories, and discussion of how the categories of (i) , (ii) and (iii) fit together to form the final theory: ’ (pp. 125–126). ‘The use of storyline as part of the finalisation of the theory from the data ensured that the final theory was grounded in the data’ (p. 201). In Chamberlain-Salaun GT study, writing the storyline enabled the identification of ‘gaps in the developing theory and to clarify categories and concepts. To address the gaps the researcher iteratively returned to the data and to the field and refine the storyline. Once the storyline was developed raw data was incorporated to support the story in much the same way as dialogue is included in a storybook or novel’. |

Theoretical sensitivity

As presented in Figure 1 , theoretical sensitivity encompasses the entire research process. Glaser and Strauss 5 initially described the term theoretical sensitivity in The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Theoretical sensitivity is the ability to know when you identify a data segment that is important to your theory. While Strauss and Corbin 12 describe theoretical sensitivity as the insight into what is meaningful and of significance in the data for theory development, Birks and Mills 6 define theoretical sensitivity as ‘the ability to recognise and extract from the data elements that have relevance for the emerging theory’ (p. 181). Conducting GT research requires a balance between keeping an open mind and the ability to identify elements of theoretical significance during data generation and/or collection and data analysis. 6

Several analytic tools and techniques can be used to enhance theoretical sensitivity and increase the grounded theorist’s sensitivity to theoretical constructs in the data. 28 Birks and Mills 6 state, ‘as a grounded theorist becomes immersed in the data, their level of theoretical sensitivity to analytic possibilities will increase’ (p. 12). Developing sensitivity as a grounded theorist and the application of theoretical sensitivity throughout the research process allows the analytical focus to be directed towards theory development and ultimately result in an integrated and abstract GT. 6 The example in Box 3 highlights how analytic tools are employed to increase theoretical sensitivity.

Theoretical sensitivity.

| Hoare et al. described how the lead author ‘ in pursuit of heightened theoretical sensitivity in a grounded theory study of information use by nurses working in general practice in New Zealand’. The article described the analytic tools the researcher used ‘to increase theoretical sensitivity’ which included ‘reading the literature, open coding, category building, reflecting in memos followed by doubling back on data collection once further lines of inquiry are opened up’. The article offers ‘an example of how analytical tools are employed to theoretically sample emerging concepts’ (pp. 240–241). |

The grounded theory

The meticulous application of essential GT methods refines the analysis resulting in the generation of an integrated, comprehensive GT that explains a process relating to a particular phenomenon. 6 The results of a GT study are communicated as a set of concepts, related to each other in an interrelated whole, and expressed in the production of a substantive theory. 5 , 7 , 16 A substantive theory is a theoretical interpretation or explanation of a studied phenomenon 6 , 17 Thus, the hallmark of grounded theory is the generation of theory ‘abstracted from, or grounded in, data generated and collected by the researcher’. 6 However, to ensure quality in research requires the application of rigour throughout the research process.

Quality and rigour

The quality of a grounded theory can be related to three distinct areas underpinned by (1) the researcher’s expertise, knowledge and research skills; (2) methodological congruence with the research question; and (3) procedural precision in the use of methods. 6 Methodological congruence is substantiated when the philosophical position of the researcher is congruent with the research question and the methodological approach selected. 6 Data collection or generation and analytical conceptualisation need to be rigorous throughout the research process to secure excellence in the final grounded theory. 44

Procedural precision requires careful attention to maintaining a detailed audit trail, data management strategies and demonstrable procedural logic recorded using memos. 6 Organisation and management of research data, memos and literature can be assisted using software programs such as NVivo. An audit trail of decision-making, changes in the direction of the research and the rationale for decisions made are essential to ensure rigour in the final grounded theory. 6

This article offers a framework to assist novice researchers visualise the iterative processes that underpin a GT study. The fundamental process and methods used to generate an integrated grounded theory have been described. Novice researchers can adapt the framework presented to inform and guide the design of a GT study. This framework provides a useful guide to visualise the interplay between the methods and processes inherent in conducting GT. Research conducted ethically and with meticulous attention to process will ensure quality research outcomes that have relevance at the practice level.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Grounded Theory

Definition:

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research methodology that aims to generate theories based on data that are grounded in the empirical reality of the research context. The method involves a systematic process of data collection, coding, categorization, and analysis to identify patterns and relationships in the data.

The ultimate goal is to develop a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, which is based on the data collected and analyzed rather than on preconceived notions or hypotheses. The resulting theory should be able to explain the phenomenon in a way that is consistent with the data and also accounts for variations and discrepancies in the data. Grounded Theory is widely used in sociology, psychology, management, and other social sciences to study a wide range of phenomena, such as organizational behavior, social interaction, and health care.

History of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory was first introduced by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s as a response to the limitations of traditional positivist approaches to social research. The approach was initially developed to study dying patients and their families in hospitals, but it was soon applied to other areas of sociology and beyond.

Glaser and Strauss published their seminal book “The Discovery of Grounded Theory” in 1967, in which they presented their approach to developing theory from empirical data. They argued that existing social theories often did not account for the complexity and diversity of social phenomena, and that the development of theory should be grounded in empirical data.

Since then, Grounded Theory has become a widely used methodology in the social sciences, and has been applied to a wide range of topics, including healthcare, education, business, and psychology. The approach has also evolved over time, with variations such as constructivist grounded theory and feminist grounded theory being developed to address specific criticisms and limitations of the original approach.

Types of Grounded Theory

There are two main types of Grounded Theory: Classic Grounded Theory and Constructivist Grounded Theory.

Classic Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Glaser and Strauss, and emphasizes the discovery of a theory that is grounded in data. The focus is on generating a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, without being influenced by preconceived notions or existing theories. The process involves a continuous cycle of data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories and subcategories that are grounded in the data. The categories and subcategories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that explains the phenomenon.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Charmaz, and emphasizes the role of the researcher in the process of theory development. The focus is on understanding how individuals construct meaning and interpret their experiences, rather than on discovering an objective truth. The process involves a reflexive and iterative approach to data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories that are grounded in the data and the researcher’s interpretations of the data. The categories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that accounts for the multiple perspectives and interpretations of the phenomenon being studied.

Grounded Theory Conducting Guide

Here are some general guidelines for conducting a Grounded Theory study:

- Choose a research question: Start by selecting a research question that is open-ended and focuses on a specific social phenomenon or problem.

- Select participants and collect data: Identify a diverse group of participants who have experienced the phenomenon being studied. Use a variety of data collection methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis to collect rich and diverse data.

- Analyze the data: Begin the process of analyzing the data using constant comparison. This involves comparing the data to each other and to existing categories and codes, in order to identify patterns and relationships. Use open coding to identify concepts and categories, and then use axial coding to organize them into a theoretical framework.

- Generate categories and codes: Generate categories and codes that describe the phenomenon being studied. Make sure that they are grounded in the data and that they accurately reflect the experiences of the participants.

- Refine and develop the theory: Use theoretical sampling to identify new data sources that are relevant to the developing theory. Use memoing to reflect on insights and ideas that emerge during the analysis process. Continue to refine and develop the theory until it provides a comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon.

- Validate the theory: Finally, seek to validate the theory by testing it against new data and seeking feedback from peers and other researchers. This process helps to refine and improve the theory, and to ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Write up and disseminate the findings: Once the theory is fully developed and validated, write up the findings and disseminate them through academic publications and presentations. Make sure to acknowledge the contributions of the participants and to provide a detailed account of the research methods used.

Data Collection Methods

Grounded Theory Data Collection Methods are as follows:

- Interviews : One of the most common data collection methods in Grounded Theory is the use of in-depth interviews. Interviews allow researchers to gather rich and detailed data about the experiences, perspectives, and attitudes of participants. Interviews can be conducted one-on-one or in a group setting.

- Observation : Observation is another data collection method used in Grounded Theory. Researchers may observe participants in their natural settings, such as in a workplace or community setting. This method can provide insights into the social interactions and behaviors of participants.

- Document analysis: Grounded Theory researchers also use document analysis as a data collection method. This involves analyzing existing documents such as reports, policies, or historical records that are relevant to the phenomenon being studied.

- Focus groups : Focus groups involve bringing together a group of participants to discuss a specific topic or issue. This method can provide insights into group dynamics and social interactions.

- Fieldwork : Fieldwork involves immersing oneself in the research setting and participating in the activities of the participants. This method can provide an in-depth understanding of the culture and social dynamics of the research setting.

- Multimedia data: Grounded Theory researchers may also use multimedia data such as photographs, videos, or audio recordings to capture the experiences and perspectives of participants.

Data Analysis Methods

Grounded Theory Data Analysis Methods are as follows:

- Open coding: Open coding is the process of identifying concepts and categories in the data. Researchers use open coding to assign codes to different pieces of data, and to identify similarities and differences between them.

- Axial coding: Axial coding is the process of organizing the codes into broader categories and subcategories. Researchers use axial coding to develop a theoretical framework that explains the phenomenon being studied.

- Constant comparison: Grounded Theory involves a process of constant comparison, in which data is compared to each other and to existing categories and codes in order to identify patterns and relationships.

- Theoretical sampling: Theoretical sampling involves selecting new data sources based on the emerging theory. Researchers use theoretical sampling to collect data that will help refine and validate the theory.

- Memoing : Memoing involves writing down reflections, insights, and ideas as the analysis progresses. This helps researchers to organize their thoughts and develop a deeper understanding of the data.

- Peer debriefing: Peer debriefing involves seeking feedback from peers and other researchers on the developing theory. This process helps to validate the theory and ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Member checking: Member checking involves sharing the emerging theory with the participants in the study and seeking their feedback. This process helps to ensure that the theory accurately reflects the experiences and perspectives of the participants.

- Triangulation: Triangulation involves using multiple sources of data to validate the emerging theory. Researchers may use different data collection methods, different data sources, or different analysts to ensure that the theory is grounded in the data.

Applications of Grounded Theory

Here are some of the key applications of Grounded Theory:

- Social sciences : Grounded Theory is widely used in social science research, particularly in fields such as sociology, psychology, and anthropology. It can be used to explore a wide range of social phenomena, such as social interactions, power dynamics, and cultural practices.

- Healthcare : Grounded Theory can be used in healthcare research to explore patient experiences, healthcare practices, and healthcare systems. It can provide insights into the factors that influence healthcare outcomes, and can inform the development of interventions and policies.

- Education : Grounded Theory can be used in education research to explore teaching and learning processes, student experiences, and educational policies. It can provide insights into the factors that influence educational outcomes, and can inform the development of educational interventions and policies.

- Business : Grounded Theory can be used in business research to explore organizational processes, management practices, and consumer behavior. It can provide insights into the factors that influence business outcomes, and can inform the development of business strategies and policies.

- Technology : Grounded Theory can be used in technology research to explore user experiences, technology adoption, and technology design. It can provide insights into the factors that influence technology outcomes, and can inform the development of technology interventions and policies.

Examples of Grounded Theory

Examples of Grounded Theory in different case studies are as follows:

- Glaser and Strauss (1965): This study, which is considered one of the foundational works of Grounded Theory, explored the experiences of dying patients in a hospital. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of dying, and that was grounded in the data.

- Charmaz (1983): This study explored the experiences of chronic illness among young adults. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained how individuals with chronic illness managed their illness, and how their illness impacted their sense of self.

- Strauss and Corbin (1990): This study explored the experiences of individuals with chronic pain. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the different strategies that individuals used to manage their pain, and that was grounded in the data.

- Glaser and Strauss (1967): This study explored the experiences of individuals who were undergoing a process of becoming disabled. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of becoming disabled, and that was grounded in the data.

- Clarke (2005): This study explored the experiences of patients with cancer who were receiving chemotherapy. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the factors that influenced patient adherence to chemotherapy, and that was grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory Research Example

A Grounded Theory Research Example Would be:

Research question : What is the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process?

Data collection : The researcher conducted interviews with first-generation college students who had recently gone through the college admission process. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis: The researcher used a constant comparative method to analyze the data. This involved coding the data, comparing codes, and constantly revising the codes to identify common themes and patterns. The researcher also used memoing, which involved writing notes and reflections on the data and analysis.

Findings : Through the analysis of the data, the researcher identified several themes related to the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process, such as feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of the process, lacking knowledge about the process, and facing financial barriers.

Theory development: Based on the findings, the researcher developed a theory about the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process. The theory suggested that first-generation college students faced unique challenges in the college admission process due to their lack of knowledge and resources, and that these challenges could be addressed through targeted support programs and resources.

In summary, grounded theory research involves collecting data, analyzing it through constant comparison and memoing, and developing a theory grounded in the data. The resulting theory can help to explain the phenomenon being studied and guide future research and interventions.

Purpose of Grounded Theory

The purpose of Grounded Theory is to develop a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, process, or interaction. This theoretical framework is developed through a rigorous process of data collection, coding, and analysis, and is grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory aims to uncover the social processes and patterns that underlie social phenomena, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these processes and patterns. It is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings, and is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

The ultimate goal of Grounded Theory is to generate a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, and that can be used to explain and predict social phenomena. This theoretical framework can then be used to inform policy and practice, and to guide future research in the field.

When to use Grounded Theory

Following are some situations in which Grounded Theory may be particularly useful:

- Exploring new areas of research: Grounded Theory is particularly useful when exploring new areas of research that have not been well-studied. By collecting and analyzing data, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the social processes and patterns underlying the phenomenon of interest.

- Studying complex social phenomena: Grounded Theory is well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that involve multiple social processes and interactions. By using an iterative process of data collection and analysis, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the complexity of the social phenomenon.

- Generating hypotheses: Grounded Theory can be used to generate hypotheses about social processes and interactions that can be tested in future research. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for further research and hypothesis testing.

- Informing policy and practice : Grounded Theory can provide insights into the factors that influence social phenomena, and can inform policy and practice in a variety of fields. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for intervention and policy development.

Characteristics of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research method that is characterized by several key features, including:

- Emergence : Grounded Theory emphasizes the emergence of theoretical categories and concepts from the data, rather than preconceived theoretical ideas. This means that the researcher does not start with a preconceived theory or hypothesis, but instead allows the theory to emerge from the data.

- Iteration : Grounded Theory is an iterative process that involves constant comparison of data and analysis, with each round of data collection and analysis refining the theoretical framework.

- Inductive : Grounded Theory is an inductive method of analysis, which means that it derives meaning from the data. The researcher starts with the raw data and systematically codes and categorizes it to identify patterns and themes, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these patterns.

- Reflexive : Grounded Theory requires the researcher to be reflexive and self-aware throughout the research process. The researcher’s personal biases and assumptions must be acknowledged and addressed in the analysis process.

- Holistic : Grounded Theory takes a holistic approach to data analysis, looking at the entire data set rather than focusing on individual data points. This allows the researcher to identify patterns and themes that may not be apparent when looking at individual data points.

- Contextual : Grounded Theory emphasizes the importance of understanding the context in which social phenomena occur. This means that the researcher must consider the social, cultural, and historical factors that may influence the phenomenon of interest.

Advantages of Grounded Theory

Advantages of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Flexibility : Grounded Theory is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings. It is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

- Validity : Grounded Theory aims to develop a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, which enhances the validity and reliability of the research findings. The iterative process of data collection and analysis also helps to ensure that the research findings are reliable and robust.

- Originality : Grounded Theory can generate new and original insights into social phenomena, as it is not constrained by preconceived theoretical ideas or hypotheses. This allows researchers to explore new areas of research and generate new theoretical frameworks.

- Real-world relevance: Grounded Theory can inform policy and practice, as it provides insights into the factors that influence social phenomena. The theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be used to inform policy development and intervention strategies.

- Ethical : Grounded Theory is an ethical research method, as it allows participants to have a voice in the research process. Participants’ perspectives are central to the data collection and analysis process, which ensures that their views are taken into account.

- Replication : Grounded Theory is a replicable method of research, as the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be tested and validated in future research.

Limitations of Grounded Theory

Limitations of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Grounded Theory can be a time-consuming method, as the iterative process of data collection and analysis requires significant time and effort. This can make it difficult to conduct research in a timely and cost-effective manner.

- Subjectivity : Grounded Theory is a subjective method, as the researcher’s personal biases and assumptions can influence the data analysis process. This can lead to potential issues with reliability and validity of the research findings.

- Generalizability : Grounded Theory is a context-specific method, which means that the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. This can limit the applicability of the research findings.

- Lack of structure : Grounded Theory is an exploratory method, which means that it lacks the structure of other research methods, such as surveys or experiments. This can make it difficult to compare findings across different studies.

- Data overload: Grounded Theory can generate a large amount of data, which can be overwhelming for researchers. This can make it difficult to manage and analyze the data effectively.

- Difficulty in publication: Grounded Theory can be challenging to publish in some academic journals, as some reviewers and editors may view it as less rigorous than other research methods.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Uniform Histogram – Purpose, Examples and Guide

Data Analysis – Process, Methods and Types

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

Factor Analysis – Steps, Methods and Examples

Multidimensional Scaling – Types, Formulas and...

- Correspondence

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2011

How to do a grounded theory study: a worked example of a study of dental practices

- Alexandra Sbaraini 1 , 2 ,

- Stacy M Carter 1 ,

- R Wendell Evans 2 &

- Anthony Blinkhorn 1 , 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 11 , Article number: 128 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

388k Accesses

209 Citations

42 Altmetric

Metrics details

Qualitative methodologies are increasingly popular in medical research. Grounded theory is the methodology most-often cited by authors of qualitative studies in medicine, but it has been suggested that many 'grounded theory' studies are not concordant with the methodology. In this paper we provide a worked example of a grounded theory project. Our aim is to provide a model for practice, to connect medical researchers with a useful methodology, and to increase the quality of 'grounded theory' research published in the medical literature.

We documented a worked example of using grounded theory methodology in practice.

We describe our sampling, data collection, data analysis and interpretation. We explain how these steps were consistent with grounded theory methodology, and show how they related to one another. Grounded theory methodology assisted us to develop a detailed model of the process of adapting preventive protocols into dental practice, and to analyse variation in this process in different dental practices.

Conclusions

By employing grounded theory methodology rigorously, medical researchers can better design and justify their methods, and produce high-quality findings that will be more useful to patients, professionals and the research community.

Peer Review reports

Qualitative research is increasingly popular in health and medicine. In recent decades, qualitative researchers in health and medicine have founded specialist journals, such as Qualitative Health Research , established 1991, and specialist conferences such as the Qualitative Health Research conference of the International Institute for Qualitative Methodology, established 1994, and the Global Congress for Qualitative Health Research, established 2011 [ 1 – 3 ]. Journals such as the British Medical Journal have published series about qualitative methodology (1995 and 2008) [ 4 , 5 ]. Bodies overseeing human research ethics, such as the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, and the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research [ 6 , 7 ], have included chapters or sections on the ethics of qualitative research. The increasing popularity of qualitative methodologies for medical research has led to an increasing awareness of formal qualitative methodologies. This is particularly so for grounded theory, one of the most-cited qualitative methodologies in medical research [[ 8 ], p47].

Grounded theory has a chequered history [ 9 ]. Many authors label their work 'grounded theory' but do not follow the basics of the methodology [ 10 , 11 ]. This may be in part because there are few practical examples of grounded theory in use in the literature. To address this problem, we will provide a brief outline of the history and diversity of grounded theory methodology, and a worked example of the methodology in practice. Our aim is to provide a model for practice, to connect medical researchers with a useful methodology, and to increase the quality of 'grounded theory' research published in the medical literature.

The history, diversity and basic components of 'grounded theory' methodology and method

Founded on the seminal 1967 book 'The Discovery of Grounded Theory' [ 12 ], the grounded theory tradition is now diverse and somewhat fractured, existing in four main types, with a fifth emerging. Types one and two are the work of the original authors: Barney Glaser's 'Classic Grounded Theory' [ 13 ] and Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin's 'Basics of Qualitative Research' [ 14 ]. Types three and four are Kathy Charmaz's 'Constructivist Grounded Theory' [ 15 ] and Adele Clarke's postmodern Situational Analysis [ 16 ]: Charmaz and Clarke were both students of Anselm Strauss. The fifth, emerging variant is 'Dimensional Analysis' [ 17 ] which is being developed from the work of Leonard Schaztman, who was a colleague of Strauss and Glaser in the 1960s and 1970s.

There has been some discussion in the literature about what characteristics a grounded theory study must have to be legitimately referred to as 'grounded theory' [ 18 ]. The fundamental components of a grounded theory study are set out in Table 1 . These components may appear in different combinations in other qualitative studies; a grounded theory study should have all of these. As noted, there are few examples of 'how to do' grounded theory in the literature [ 18 , 19 ]. Those that do exist have focused on Strauss and Corbin's methods [ 20 – 25 ]. An exception is Charmaz's own description of her study of chronic illness [ 26 ]; we applied this same variant in our study. In the remainder of this paper, we will show how each of the characteristics of grounded theory methodology worked in our study of dental practices.

Study background

We used grounded theory methodology to investigate social processes in private dental practices in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. This grounded theory study builds on a previous Australian Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) called the Monitor Dental Practice Program (MPP) [ 27 ]. We know that preventive techniques can arrest early tooth decay and thus reduce the need for fillings [ 28 – 32 ]. Unfortunately, most dentists worldwide who encounter early tooth decay continue to drill it out and fill the tooth [ 33 – 37 ]. The MPP tested whether dentists could increase their use of preventive techniques. In the intervention arm, dentists were provided with a set of evidence-based preventive protocols to apply [ 38 ]; control practices provided usual care. The MPP protocols used in the RCT guided dentists to systematically apply preventive techniques to prevent new tooth decay and to arrest early stages of tooth decay in their patients, therefore reducing the need for drilling and filling. The protocols focused on (1) primary prevention of new tooth decay (tooth brushing with high concentration fluoride toothpaste and dietary advice) and (2) intensive secondary prevention through professional treatment to arrest tooth decay progress (application of fluoride varnish, supervised monitoring of dental plaque control and clinical outcomes)[ 38 ].

As the RCT unfolded, it was discovered that practices in the intervention arm were not implementing the preventive protocols uniformly. Why had the outcomes of these systematically implemented protocols been so different? This question was the starting point for our grounded theory study. We aimed to understand how the protocols had been implemented, including the conditions and consequences of variation in the process. We hoped that such understanding would help us to see how the norms of Australian private dental practice as regards to tooth decay could be moved away from drilling and filling and towards evidence-based preventive care.

Designing this grounded theory study

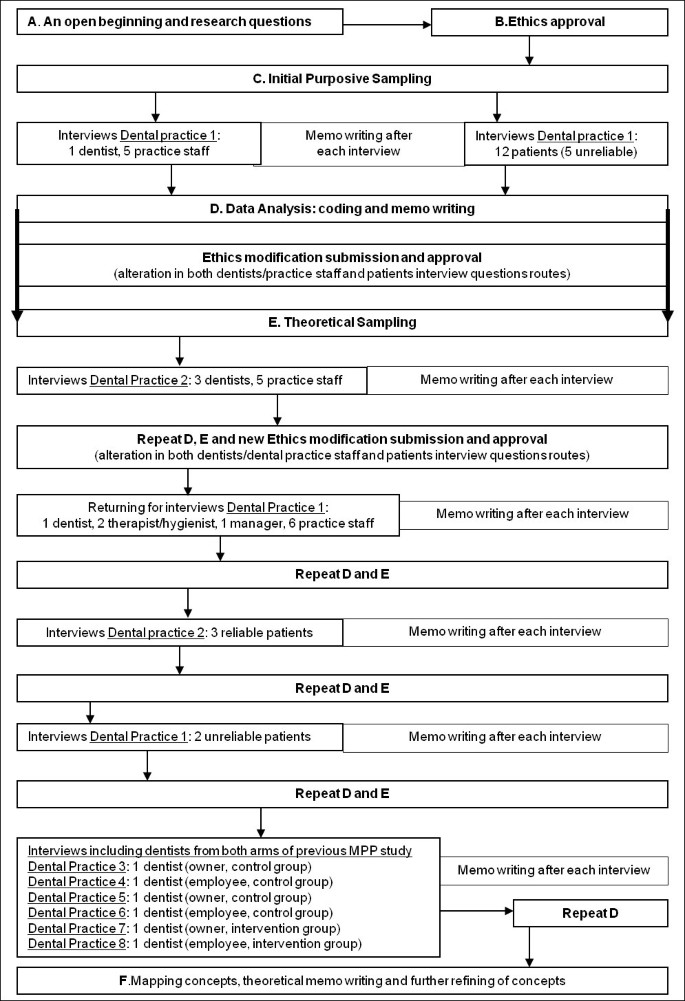

Figure 1 illustrates the steps taken during the project that will be described below from points A to F.

Study design . file containing a figure illustrating the study design.

A. An open beginning and research questions

Grounded theory studies are generally focused on social processes or actions: they ask about what happens and how people interact . This shows the influence of symbolic interactionism, a social psychological approach focused on the meaning of human actions [ 39 ]. Grounded theory studies begin with open questions, and researchers presume that they may know little about the meanings that drive the actions of their participants. Accordingly, we sought to learn from participants how the MPP process worked and how they made sense of it. We wanted to answer a practical social problem: how do dentists persist in drilling and filling early stages of tooth decay, when they could be applying preventive care?

We asked research questions that were open, and focused on social processes. Our initial research questions were:

What was the process of implementing (or not-implementing) the protocols (from the perspective of dentists, practice staff, and patients)?

How did this process vary?

B. Ethics approval and ethical issues

In our experience, medical researchers are often concerned about the ethics oversight process for such a flexible, unpredictable study design. We managed this process as follows. Initial ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Sydney. In our application, we explained grounded theory procedures, in particular the fact that they evolve. In our initial application we provided a long list of possible recruitment strategies and interview questions, as suggested by Charmaz [ 15 ]. We indicated that we would make future applications to modify our protocols. We did this as the study progressed - detailed below. Each time we reminded the committee that our study design was intended to evolve with ongoing modifications. Each modification was approved without difficulty. As in any ethical study, we ensured that participation was voluntary, that participants could withdraw at any time, and that confidentiality was protected. All responses were anonymised before analysis, and we took particular care not to reveal potentially identifying details of places, practices or clinicians.

C. Initial, Purposive Sampling (before theoretical sampling was possible)

Grounded theory studies are characterised by theoretical sampling, but this requires some data to be collected and analysed. Sampling must thus begin purposively, as in any qualitative study. Participants in the previous MPP study provided our population [ 27 ]. The MPP included 22 private dental practices in NSW, randomly allocated to either the intervention or control group. With permission of the ethics committee; we sent letters to the participants in the MPP, inviting them to participate in a further qualitative study. From those who agreed, we used the quantitative data from the MPP to select an initial sample.