Distance-Learning Modalities in Education Essay

Introduction.

Distance education relates to an instruction delivery modality where learning occurs between the educator and students who are geographically isolated from each other during the learning process. Distance learning modalities include off-site satellite classes, video conferencing and teleconferencing, web-based instruction, and faculty-supervised clinical experiences, including internships. This study focuses on satellite campuses and videoconferencing and teleconferencing modalities. It provides a comprehensive listing of these modalities’ benefits and drawbacks, as well as a detailed comparison between them, and describes outcomes related to distance learning’s efficacy.

Pros and Cons of Selected Modalities

Satellite campuses.

Satellite campuses relate to programs that provide the curriculum in part or whole on off-campus locations from the parent organization. Studies associate satellite campuses with several advantages; first, it promotes interpersonal communication between students and faculty and improves cultural diversity. Second, it enhances learners’ experiences and opportunities, including campus choices, small class sizes at off-site campuses, and flexibility in viewing lecturers (Keating, 2014). Third, it allows dual-degree options and the opportunity to utilize and adopt distance education technologies. Fourth, off-site campuses can help increase student enrolment in the program, especially those from underrepresented regions. Ultimately, this modality has been associated with cost-related efficiencies, including the need for fewer faculty members and resource sharing.

Researchers also associate this modality with several cons; first, locating qualified off-site faculty to teach a specific subject content since they should be oriented to the curricula to ensure integrity. Finding faculty with the necessary expertise is difficult; therefore, parent campuses need an additional course coordinator to ensure the course’s integrity. Second, additional resources are required to implement or develop distant satellite campuses. Third, satellite campuses frequently lose students to the parent campus (Keating, 2014). Fourth, this modality has been linked with probable incongruence between the courses’ implementation in the curriculum due to the lack of interaction amid faculty and staff within the home campus. Fifth, since it depends on part-time faculty, institutional commitment is low. Lastly, satellite campuses must limit program offerings to reduce the risks of the program’s cost becoming unsustainable.

Videoconferencing and Teleconferencing

Teleconferencing and videoconferencing demand the installation of dedicated classrooms capable of sending and receiving digital information both off-site and on-site. This modality has been linked with several benefits; first, it allows real-time interactions between faculty and students. Next, faculty members can introduce guest speakers and live events in class without taking them to those events (Keating, 2014). The curriculum can be delivered to a large audience, increasing the chances of the curriculum’s integrity is maintained. It also reduces travel expenses and the costs for program mounting and maintenance. Additionally, success rates are high for institutions with sufficient institutional capabilities and support (Keating, 2014). Lastly, partnerships are mutually beneficial for educational institutions and healthcare organizations aiming to increase professional development or continuing education.

There several drawbacks linked to videoconferencing and teleconferencing; first, it requires specialized equipment and tools for class delivery, making education expensive. Second, institutions with limited reception and connectivity may miss out on live interactions. Third, it requires close monitoring from an expert to enhance implementation and compliance to sponsoring agency’s priority rights. Ultimately, this modality requires faculty with specialized expertise in different teaching media to ensure its success as an instructional delivery methodology.

Analysis and Comparison

Satellite Campuses incorporate face-face interactions and videoconferencing, and web-based instruction to instruct students. However, videoconferencing and teleconferencing involve delivering curriculum content via classrooms that can receive and send digital data. Both modalities allow face-to-face interaction, although satellite campus interactions are physical while that videoconferencing is online. They emphasize interaction and didactic relationships between faculty and students (Keating, 2014). The parent campus plays an integral role in the seamless implementation of the program in both modalities. Moreover, in satellite campuses, part of the classes is conducted on-site at the parent campus. Similarly, videoconferencing can also be delivered in on-site classes. Both modalities’ parent campus is responsible for ensuring course integrity and that the curriculum satisfies their educational goals.

Outcome Description Related to Teaching and Learning Effectiveness and Student and Faculty Satisfaction

Distance learning (DL) is associated with positive learning outcomes and student and faculty satisfaction. Berndt et al. (2017) showed that rural health practitioners and class facilitators were highly satisfied with distance learning strategies in professional development. Al-Balas et al. (2020) also supported this notion that distance learning improves learning outcomes. The study showed the approach provides students with educational autonomy and facilitates access to a broader range of learning resources. Another survey by Tomaino et al. (2021) demonstrated that DL produced positive educational outcomes in students with severe developmental and behavioral needs. The study participants showed positive progress in achieving their academic goals when they were engaged in DL. Tomaino et al. (2021) revealed that using audio, video, computers, and the internet increased parental engagement in students’ education. The DL helped the parents assess their children’s academic ability and learn how to effectively manage their disabilities and challenging behaviors with the instructor’s help.

DL is also cost-effective and can lead to cost-savings related to travel time. Rotimi et al. (2017) report that web-based programs make learning cheaper and are viable alternatives to face-to-face classes. Berndt et al. (2017) revealed that DL reduced healthcare providers’ travel time and costs (learners). Therefore, it can be surmised that DL can reduce travel costs for learners. Another aspect that stood out in Berndt et al. (2017) study is that face-to-face learning does not result in better outcomes than DL. The study showed that distance education produces better learning outcomes irrespective of delivery modes (Berndt et al., 2018). Learning outcomes were measured using learners’ knowledge and satisfaction scores.

However, it is essential to note that distance learning does not always result in high satisfaction levels unless certain conditions are fulfilled. Al-Balas et al. (2020) showed that medical students have negative perceptions of distance learning and were unsatisfied with it. The participants’ negative perception and dissatisfaction with distance learning emanated from their past experiences with the program. The students revealed that most distance-learning faculty were uncooperative and generally preferred the traditional approach. This revelation confirms Keating’s (2017) assertion that a critical weakness of distance learning is the lack of faculty commitment. Approximately 55.2% of the students also believed that other medical students would not commit to DL programs (Al-Balas et al., 2020). Satisfaction with DL was strongly connected to student’s experiences and interactions with the program’s faculty. Therefore, institutions should implement strategies to enhance both faculty and students’ reception of the program. On a positive note, 75.5% of the study participants preferred the blended education approach (mix of distance learning and on-site classes) (Al-Balas et al., 2020). This preference should encourage the integration of distance learning modalities with the traditional learning style.

Technological advancements in the education sector allow both learners and faculty members to easily access, collect, evaluate, and disseminate knowledge and relevant data. Learning communities have currently evolved from conventional classrooms to e-learning settings. Students converge or connect in a virtual surrounding to solve issues, exchange ideas, develop new meanings, and explore alternatives. There are various distance learning modalities, including teleconferencing and videoconferencing and satellite campuses. These methodologies have been associated with significant benefits and drawbacks.

Al-Balas, M., Al-Balas, H. I., Jaber, H. M., Obeidat, K., Al-Balas, H., Aborajooh, E. A., Al-Taher, R., & Al-Balas, B. (2020). Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Current situation, challenges, and perspectives . BMC Medical Education , 20 , 1–7. Web.

Berndt, A., Murray, C. M., Kennedy, K., Stanley, M. J., & Gilbert-Hunt, S. (2017). Effectiveness of distance learning strategies for continuing professional development (CPD) for rural allied health practitioners: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education , 17 , 1–13. Web.

Keating, S. B. (2014). Curriculum development and evaluation in nursing (3 rd ed.). Springer Publishing.

Rotimi, O., Orah, N., Shaaban, A., Daramola, A. O., & Abdulkareem, F. B. (2017). Remote teaching of histopathology using scanned slides via skype between the United Kingdom and Nigeria . Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine , 141 (2), 298–300. Web.

Tomaino, M. A. E., Greenberg, A. L., Kagawa-Purohit, S. A., Doering, S. A., & Miguel, E. S. (2021). An assessment of the feasibility and effectiveness of distance learning for students with severe developmental disabilities and high behavioral needs. Behavior Analysis in Practice , 1 (1), 1–16. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, August 24). Distance-Learning Modalities in Education. https://ivypanda.com/essays/distance-learning-modalities-in-education/

"Distance-Learning Modalities in Education." IvyPanda , 24 Aug. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/distance-learning-modalities-in-education/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Distance-Learning Modalities in Education'. 24 August.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Distance-Learning Modalities in Education." August 24, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/distance-learning-modalities-in-education/.

1. IvyPanda . "Distance-Learning Modalities in Education." August 24, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/distance-learning-modalities-in-education/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Distance-Learning Modalities in Education." August 24, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/distance-learning-modalities-in-education/.

- Adult Education Graphic Organizer

- Field-Based School Community Relation

- DL Limited Company Business Plan

- The Publications on IRRODL: Review

- Videoconferencing Technology in Education

- E-Learning: Video, Television and Videoconferencing

- Women in Psychology: Karen Horney

- Communication and Its Role in Organization

- Controlling the Offsite Storage

- Social Interactions Through the Virtual Video Modality

- Hillgrove High School Data Profile

- Collective Efficacy Action Plan at Highschool X

- Purpose of Human Resource Management in the UAE Public School

- The Plight of Mexican American Students in US Public School System

- A Comparison of Colonial and Modern Institutions of Higher Education

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Teaching and learning modalities in higher education during the pandemic: responses to coronavirus disease 2019 from spain.

- 1 Faculty of Law and Social Sciences, King Juan Carlos University, Madrid, Spain

- 2 Faculty of Education, International University of La Rioja, Logroño, Spain

- 3 Faculty of Health Sciences, King Juan Carlos University, Madrid, Spain

- 4 Faculty of Education, Camilo José Cela University, Madrid, Spain

The effects of the pandemic have affected and continue to affect education methods every day. The education methods are not immune to the pandemic periods we are facing, so teachers must know how to adapt their methods in such a way that teaching, and its quality, is not negatively affected. This study provides an overview of different types of teaching methodology before, during, and after the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This study describes the different types of teaching (e.g., presence learning, blended learning, and distance education) used in two Spanish Universities (i.e., one private and one public) during the pandemic. A new teaching methodology is proposed. The purpose of this study report is to share what we learned about the response to COVID-19. Results provide a basis for reflection about the pros and cons of teaching and learning modalities in higher education. The current situation demands that we continue to rethink what is the best methodology for teaching so that the education of students is not affected in any way. This study is useful for learning about different teaching methods that exist and which ones may suit us best depending on the context, situation, and needs of our students.

Introduction

As a result of the situation caused by the State of Alarm driven by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the educational system has been forced to adapt to the new capacity requirements and, in many cases, cease their usual activity.

The Community of Madrid, Spain, forced the closure of educational centers on March 12, 2020. A few days later, on March 14, 2020, the State of Alarm was decreed for the entire Spanish territory for an initial period of 15 days with strict measures of confinement and with restrictions on the movement of people and on the economic activity. This confinement was extended until June 21, 2020. Thus, the longest State of Alarm in the history of Spain ended after 3 months of confinement to stop the spread of COVID-19, and the so-called “New Normal” began. The restrictions on the movement between the Spanish provinces ended, and the coexistence with the virus began.

One of the most important decisions made at the educational level took place on April 14, 2020. The Government and the Autonomous Communities of Spain agreed that the academic year of 2019–2020 Educational System would end in June, and repetition would be exceptional at primary and secondary levels. Face-to-face classes, in general, would resume in September. During the 2019–2020 course, only those students who needed reinforcement or changed their educational stage, as well as children from 0 to 6 years old whose parents did not do telework, voluntarily returned to the classrooms. This was a very important shock not only for University levels but also for all educational levels.

From March to September 2020, due to the declaration of a State of Alarm by the National Government, the educational centers could not be opened, and they had to optimally adapt to this fact. Each educational center had to base its teaching on the online mode and to adapt teachers and students to this new reality: videoconferencing software was used to avoid social disconnection, students were disoriented, ignorance of new tools had to be overcome to teach classes, and the evaluation systems need to be redesigned. The pandemic revealed the shortcomings of educational institutions, mainly about the infrastructures and the training of teachers in the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools. However, it also meant improvements. The teachers were trained in new online methodologies and showed interest in learning new teaching tools in the face of the new reality and challenges that arose.

As of the new academic year 2020–2021, which began in September 2020, this teaching modality became eligible again. Each University, therefore, chose the type of methodology that it would use to carry out in its classes. In the universities themselves, depending on the faculties and the studies, different teaching methodologies are currently used.

Effects of COVID-19 on the Education Performance of University Students in Classrooms

The Spanish University System (SUE) is made up of a total of 83 universities−50 public and 33 private ( Figure 1 ).

- Out of the 50 public universities, 47 offer presence learning, and 1 offers distance learning.

- Out of the 33 private universities, 28 offer presence learning, and 5 offer distance learning.

Figure 1 . Geographical distribution of the Spanish universities with activity in the academic year 2019–2020. Statistics report (2020–2021) from the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Universities. Universidades.gob.es . 2021. Available online at: https://www.universidades.gob.es/ .

In addition, there are two public universities with a special status that provide only specialized postgraduate programs (master's and PhD courses).

Factors considered in the following sections are the type of University, whether it is public or private, and the type of studies pursued, since there will be some in which an online model has already been implemented naturally, or vice versa, i.e., 100% face-to-face modality. As of September 2020, Spanish universities have used the teaching methods detailed in the following sections.

Presence Learning

Presence learning consists of both the students and the teacher sharing the same physical classroom. Previous studies have emphasized the educational benefits of the use of this teaching practice ( Bigg, 2003 ; Konopka et al., 2015 ; Crisol Moya, 2016 ; Anderton et al., 2021 ; García-Peñalvo et al., 2021 ). This type of teaching methodology could not be applied from March to September 2020 due to the declaration of a State of Alarm by the government of the nation. However, as of September 2020, this teaching modality became eligible, and the educational centers were reopened.

The non-face-to-face teaching model is becoming increasingly popular in the field of higher education. Universities traditionally oriented to face-to-face teaching, regardless of whether they are public or private, are embracing this model. Although they maintain their main face-to-face structure, they offer students some distance-based degrees and master's studies ( Ben-Chayim and Offir, 2019 ; Ali, 2020 ; Hodges et al., 2020 ).

A face-to-face University that decides to include non-face-to-face teachings in its degrees and master's studies must combine its traditional procedures with the new requirements of non-face-to-face teaching ( Chick et al., 2020 ). The universities that have already had this experience, even though they have been mostly presential, have been able to adapt more quickly to the suspension of in-person activity.

Distance Education

Distance education, also known as online learning, is a type of education developed using technology that allows students to attend classes in remote locations ( Dede, 1990 ; Hodges et al., 2020 ; Sandars et al., 2020 ). It can also be defined as a type of education that joins professors and students from different locations. Although they maintain their main face-to-face structure, they offer students some distance-based degrees and master's studies. On the one hand, several authors have recognized that online teaching can be synchronous when the students and the teacher connect to the classes at the same time and can have real-time interactions. On the other hand, in asynchronous teaching, the teacher and the students do not have to coincide in the class. Usually, the class is recorded, and the students can view it at any time ( Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020 ; Ali, 2020 ; Bao, 2020 ).

This type of teaching, which was already followed before the pandemic, was not affected by the pandemic ( Hwang, 2018 ; Daniel, 2020 ). Distance education is characterized by having an existing organizational infrastructure, which allows the educational objectives of online learning to be developed ( Singh and Hardaker, 2014 ).

We must not confuse this type of teaching, i.e., distance education, with the Emergency remote education . In exceptional situations that impede the normal functioning of institutions and face-to-face educational centers, teachers may be forced to quickly adapt their pedagogical activity to a virtual environment. This is known here as emergency non-face-to-face teaching. In Spain, from March to June 2020, all teaching methods were entirely online. The emergency remote teaching required by the pandemic was often quickly improvised, without guaranteed or adequate infrastructure support ( Evans et al., 2020 ; Hodges et al., 2020 ; Panisoara et al., 2020 ). Given this lack of infrastructure, the main source of advice and early support for non-expert distance teachers was focused on providing the technological tools available in each institution and was considered adequate to support the change.

Blended Learning

This model is based on a combination of classroom education and online education in various forms ( Lightner and Lightner-Laws, 2016 ; Nuruzzaman, 2016 ; Heilporn et al., 2021 ). There is no unanimity of criteria, since the meaning is ambiguous, causing confusion, and gives rise to a certain lack of rigor between the different types of blended learning ( Misseyanni et al., 2018 ; Bao, 2020 ). It is necessary to distinguish between hybrid teaching, mirror classrooms, blended teaching, and the new methodology proposed in this study, i.e., online guides in the classroom.

Hybrid Learning

Hybrid education assumes that half of the students in a class attend the classroom and the other half follow the class from home, partially online and partially face-to-face ( Misseyanni et al., 2018 ; Bao, 2020 ).

The use of the hybrid-flexible ( HyFlex ) instructional methodologies is relatively recent in higher education ( Beatty, 2019 ). As has been previously reported in descriptive case studies, the HyFlex techniques are implemented by an instructor. Previous research has shown efforts to include this methodology, although few studies report the impact on student learning and the associated metrics of interest, such as qualifications, retention, pass rate, and time to graduation ( Lightner and Lightner-Laws, 2016 ; Beatty, 2019 , Binnewies and Wang, 2019 ; Mumford and Dikilitaş, 2020 ).

From September 2020, in Spanish universities that followed this methodology, groups of face-to-face students and online students alternated to achieve social distance without having to modify the structure of the classrooms.

Mirror Rooms

With the accumulated incidence of COVID-19, one of the options used in Spanish University education was the so-called “ Mirror Rooms ,” which allows face-to-face classes but at a safe distance, ensuring a distance of at least 1.5 m between the chairs. To maintain the safety distance measures in the case of not having large enough classrooms, the group of students is divided into two subgroups. Half of the group is in a classroom, with the teacher, while the other half is in an adjoining classroom, watching the class by live videoconference. The advantage of this typology compared with hybrid education, in which half of the students follow the class from home, or compared with a blended education, in which the face-to-face education is alternated with online teaching, is that, in Mirror Rooms , the students do not depend on their resources or the connection in their homes, since the entire process is carried out in the educational center, including the online part. They have their classmates in class for support and motivation and are able to continue enjoying contact with classmates and a University environment ( Misseyanni et al., 2018 ).

The drawbacks of this type of methodology are the need to have enough classrooms, in addition to the technical resources necessary to broadcast the class live and personnel who can control these mirror classrooms. Another disadvantage supposes students do not have any engagement directly with the lecturer, who will be in standing in another classroom, being a similar situation to that in asynchronous online classes. In University studies, this methodology may be feasible, but not so much in other educational stages, in which it will not be easy for students to be alone in a class and pay attention.

A “Semi-Presential Learning” Blended System

The approach of the blended system is mostly carried out with the alternation between face-to-face classes and online education, either by videoconference or by independently following, i.e., individually or in groups, the tasks begun in class in person. A variety of this model is splitting up students and having those groups take turns going to class. According to the study by Cândido, in the semi-present context, students alternate online activities with face-to-face meetings ( Cândido et al., 2020 ). This means fewer contact hours for each subject, which will be compensated with work from home. For example, if we work on projects, students can take part in the classroom and stay at home when they cannot go to the school in person.

Online Guide in the Classroom

Another new approach to blended learning education that is proposed in this study is what we have called the “ Online guide classroom .” This new methodology has been made evident by the new reality of the pandemic. A person who has been in contact with another person who has tested positive for COVID-19 should take the contagion test and stay at their home until the results of the test are known. In this situation, teachers, who physically have no symptoms and are well, have noticed how their teaching has been interrupted, being a detriment to their students.

In an Online guide classroom , the teacher stays at home, or another location, and teaches through a computer, and the students physically travel to the campus to follow the video conference. The advantage of this type of teaching is that, if the teacher is in the previous situation, is in quarantine and might have been exposed to COVID-19, or is even unable to attend a class, e.g., for other activities, e.g., assisting a Congress in another country, students will not miss class. In addition, students will be able to continue enjoying University life and to carry out group work in person with their classmates. This option is particularly necessary for science students who need to work in the laboratories for their lessons ( Anderton et al., 2021 ). The classroom will need to meet certain technical requirements to be able to project the videoconference, e.g., microphones and cameras incorporated in the classroom, i.e., the same hybrid-learning technical resources that prior research suggests ( Hwang, 2018 ; Bao, 2020 ; Salikhova et al., 2020 ), as well as staff or students responsible for connecting these devices.

Methodology

An investigation was carried out with the purpose of analyzing whether the change in the teaching–learning methodology, due to COVID-19, diminished in any way the quality of the education and/or the satisfaction of the students.

The sample consisted of 307 University students who voluntarily decided to participate in the investigation and who were subdivided into two groups. The first group, surveyed in November 2020, was made up of 152 University students, 128 women and 24 men between 19 and 22 years of age. The second group, surveyed in February 2021, was made up of 155 University students, 57 women and 98 men between 19 and 22 years of age, so the sample consisted of a total of 185 women and 122 men. The students pursued different University studies as follows: Early Childhood Education, Primary Education, and Physical Activity and Science Sports + Physiotherapy (a double degree program). We were especially interested in the point of view of the former two groups because they will become teachers. We added students not directly related to education to the sample for more heterogeneity. In addition, the first group of students, surveyed in 2020, was composed of students from a private University, and the second group, surveyed in 2021, was composed of students from a public University. The percentage of women in the first group of students surveyed was much higher, but this was compensated with the incorporation of the second group of students surveyed, reaching a final proportion of 60% women and 40% men.

To conduct the study, the surveys were sent to each student through Google Forms to avoid paper processing and to facilitate their completion, each of them having been previously informed of the study objectives.

Before administering the questionnaire to the students, compliance with all the required ethical standards was ensured as follows: written informed consent, the right to information, confidentiality, anonymity, gratuity, and the option to abandon the study ( MacMillan and Schumacher, 2001 ).

This research was not approved by an ethics committee, since the data are not clinical or sensitive, although they were anonymized.

All questions used for our study referred to three possible classroom situations experienced by all students from 2020 to 2021. The study was carried out in the different modalities developed according to the governmental restrictions in Spain and around the world as follows:

• First: The pre-COVID-19 scenario, without any social restriction: a face-to-face environment. Location(s): University.

• Second: The COVID-19 scenario, with all social restrictions: a confinement situation, and the perimetral lockdowns of regions: an online environment. Location(s): Home.

• Third: The current scenario, the COVID-19 scenario with some restrictions, living with the virus: a combination of online, semi-presential, and online guide classrooms. Location(s): Home and University.

Throughout the academic year 2020–2021, no student was able to attend their classes in the same way they did at the beginning of the previous year, since the pandemic was still in force; however, in our study, all students surveyed had experienced all scenarios because they were all University students who were currently in their second year of University studies. Therefore, the two groups surveyed were able to answer the study questions based on their experience of classes without restrictions in the previous year, before the pandemic broke out, and to compare that with the current restrictions.

Students, as well as the teacher, had to adapt to the situation that was being experienced around the world and to change their teaching–learning methodology in order to continue learning. The main objective since the beginning of all these changes was to preserve the natural progress of the classes and ensure that the changes in methodology did not affect the quality of the education and the satisfaction of the students.

To analyze whether this objective was being achieved, students were analyzed in regard to their satisfaction, the quality of the education, and the feelings of the students during these new conditions and education modalities.

Two instruments were used to measure educational quality and student satisfaction in regard to the three educational modalities described earlier. Six main items were assessed, in addition to the academic quality and the satisfaction of the students, over the three phases listed earlier. In the case of the 6 items, students were given a questionnaire made up of 6 parameters to be assessed individually. Each participant responded using a 10-point Likert-type scale, 1 being “totally disagree” and 10 “totally agree.”

Items studied were as follows:

1. Accessibility

2. Satisfaction

3. Participation

4. Results obtained

5. Innovative value of teaching practice

6. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Knowledge.

In the case of academic satisfaction with the classes, the scale suggested by Lent et al., composed of seven items that assess the degree of the satisfaction of students with respect to academic activity, was used ( Lent et al., 2005 ). Each of the students who participated in the study responded using a 5-point Likert-type scale, 1 for “totally disagree” and 5 for “totally agree.”

Limitations

The approach utilized suffers from the limitation that the study only captured the sample of two Spanish universities, i.e., one private and one public. The degrees studied are related to the field of Education (75%) and Science (25%): a degree in Early Childhood Education, a degree in Primary Education, and a degree in Physical Activity and Sports + Physiotherapy.

Statistical Analysis

Using the SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics) statistical software, the missing values were evaluated, considering the items of each instrument to estimate whether it responded to a random distribution ( Tabachnick et al., 2011 ). The arithmetic mean, SD, asymmetry, and kurtosis were also calculated in each case. As a criterion to evaluate the asymmetry and kurtosis indices, values between −1.00 and 1.00 were considered excellent, and values within the range of −2.00 to 2.00 were considered adequate ( George and Mallery, 2011 ).

Compliance with the statistical assumptions was verified, the exploratory factor analysis was applied to demonstrate the underlying structure of the scale, and its internal consistency was estimated using the Cronbach's alpha statistic. First, the amount and pattern of the missing data were examined using the Missing Value Analysis Routine in SPSS. Since no variables that present more than 5% of the missing values were observed, no studies were conducted to evaluate the randomness pattern of the missing values. No outliers were observed ( Goodyear, 2020 ). Following the recommendations of Zabala, the t distribution was used to determine the statistical significance, and the favorable results were obtained without having any case that exceeded the threshold considered ( Zabala and Arnau, 2015 ).

The descriptive statistical values of the arithmetic mean and SD were calculated, and the asymmetry and kurtosis indices were obtained to analyze the normality of the distributions. Asymmetry and kurtosis indicated the shape of the distribution of our variables. These measurements allowed us to determine the characteristics of their asymmetry and homogeneity without the need to represent them graphically. All the variables presented indices between −1.5 and 1.5. Results were considered optimal for carrying out the planned statistical analyses ( George and Mallery, 2011 ).

Three studies were carried out with the sample collected: Study 1 corresponds to the first group surveyed in November 2020, Study 2 corresponds to the second group surveyed in February 2021, and Study 3 corresponds to the entire sample, i.e., the first and second groups.

The average evaluation of the presence learning was 7.2, with satisfaction and participation being the highest-valued items in this modality. Knowledge in ICT was the least necessary for performance.

In the case of the online modality , we observed the highest scores in accessibility and knowledge in ICT but the worst score in participation. In this case, an average of 7.8 was reached.

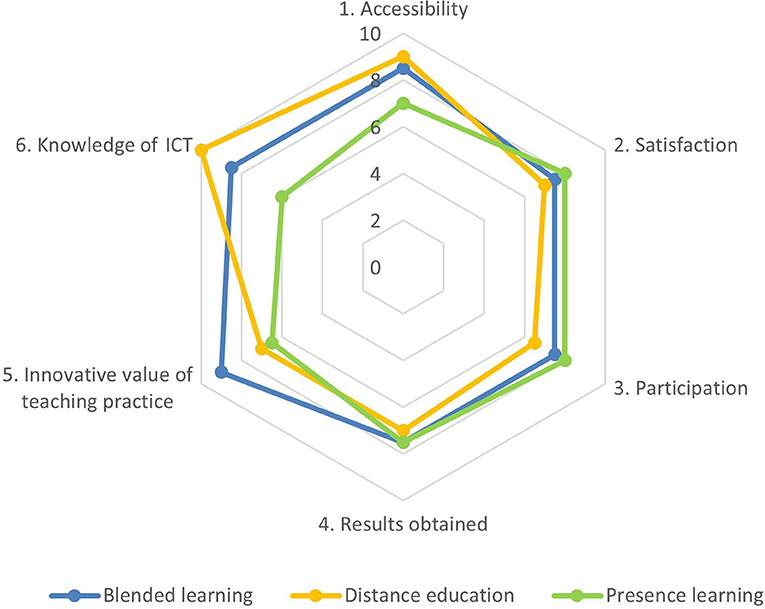

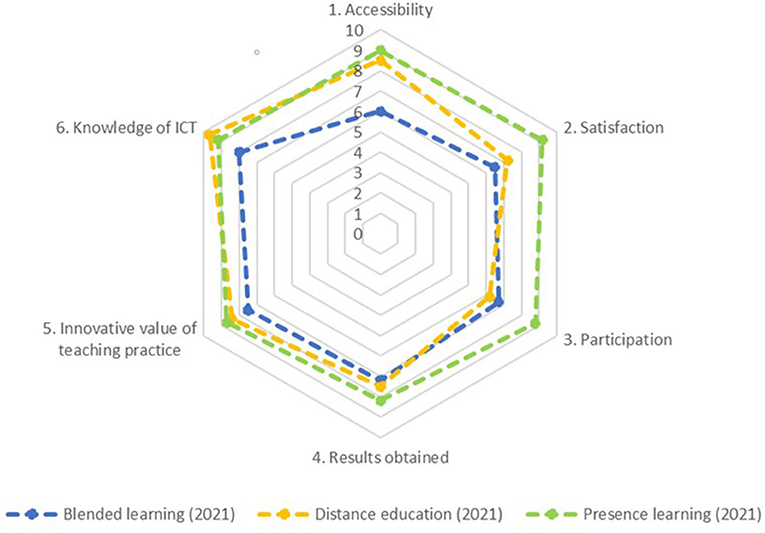

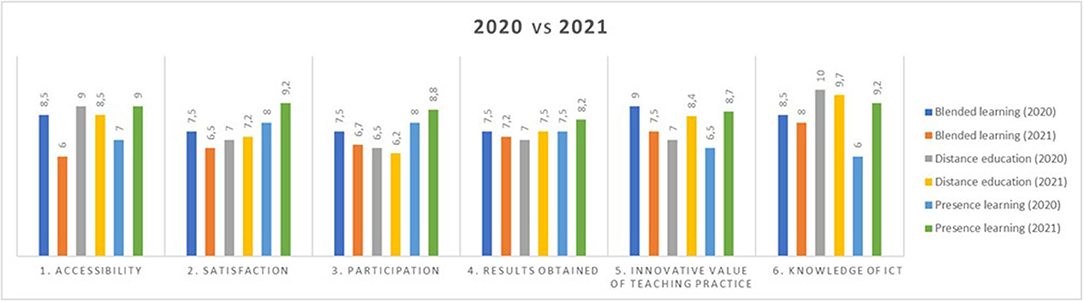

The blended learning modality reached an average of 8.1, obtaining scores around 7.5 and 9.3. The innovative aspects of this modality were most highly evaluated ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2 . Comparison of items in Study 1. Source: Own elaboration.

If we use the asymmetry and kurtosis values, it can be affirmed that, in all items, there is a high degree of concentration around the arithmetic mean. All participants agreed on the positivity of all the modalities of the teaching–learning classes of the study. That is, all students considered the practice carried out to be excellent and highly beneficial for their education, and their satisfaction was not affected by the fact of having to change modalities during the course, although the students of this group, in general terms, preferred blended learning.

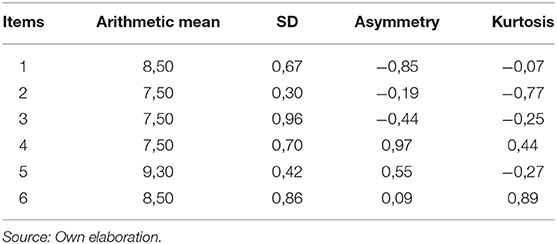

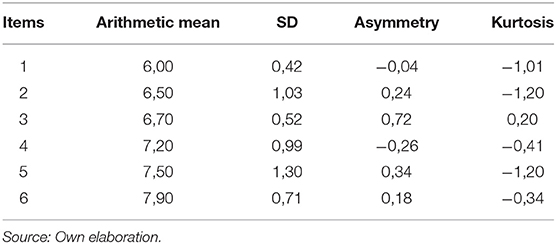

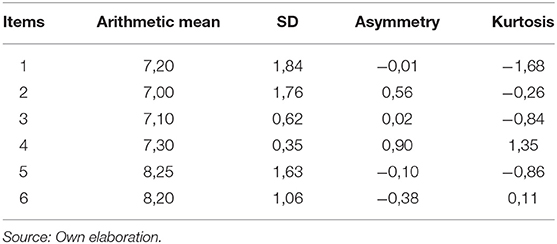

Regarding Table 1 on the blended learning from Study 1, the degree of satisfaction in the students was very high, which indicates an excellent degree of significance ( George and Mallery, 2011 ). In addition, all variables have a high SD and high asymmetry and kurtosis indices. The innovative value of teaching practice was scored with a 9.3, the highest score.

Table 1 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 1 with blended learning.

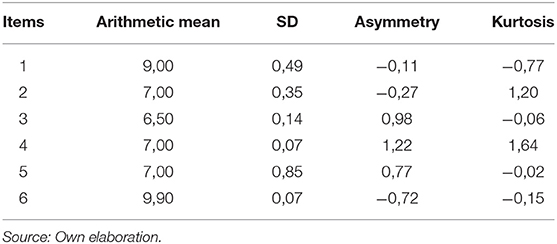

Table 2 represents the scores and indices of the statistical analysis of distance education . The best-scored item was Item 6, i.e., knowledge of ICTs reached 9.9 and had high asymmetry and kurtosis indices. The worst score was for the item that evaluated participation. Still, satisfaction reached a remarkable score.

Table 2 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 1 with distance education.

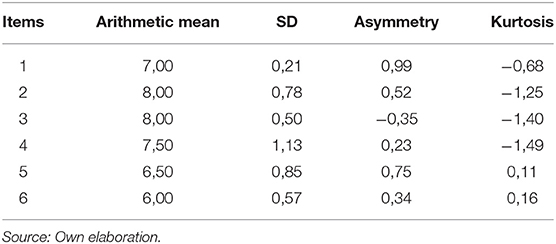

Finally, Table 3 represents the scores and indices of the statistical analysis of face-to-face education . Participation and satisfaction were the best-rated items here, i.e., the best in the entire Study 1, and the worst was for knowledge about ICT applications.

Table 3 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 1 with presence learning.

In this study, the mean scores of the three teaching modalities improved in most cases. The average evaluation of the presence learning is 8.8, with the second- and third-most valued items being satisfaction and accessibility.

In the case of the online modality , we again observed that the highest score was for knowledge of ICTs. The average evaluation in this case was 7.9.

The blended learning modality reached an average of 7.0, i.e., 1.1 percentage points lower than in the previous study. The best score was obtained for knowledge in ICTs, and the worst was for accessibility ( Figure 3 ).

Figure 3 . Comparison of items in Study 2. Source: Own elaboration.

As in the previous study, the statistical values of the arithmetic mean, SD, asymmetry, and kurtosis were recalculated. All items obtained excellent or adequate scores depending on the teaching modality, but all of them are ideal, between −1.5 and 1.5, for studying the three teaching modalities ( George and Mallery, 2011 ).

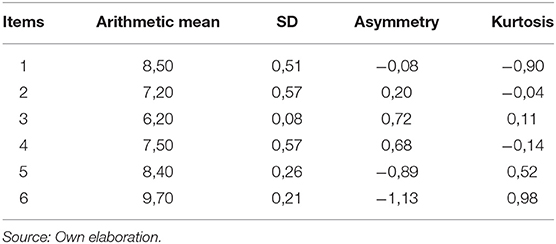

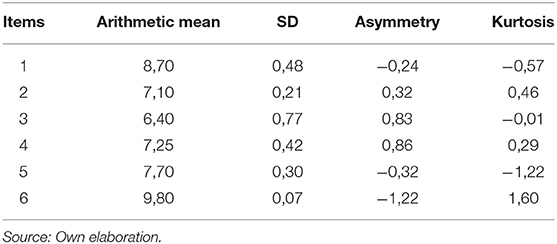

Regarding Table 4 on the blended learning from Study 2, the degree of ICT knowledge was high, but accessibility was scored with the worst value in this study for all learning modalities. Once again, it is remarkable that all the variables have ideal indices in terms of the arithmetic mean, SD, asymmetry, and kurtosis ( George and Mallery, 2011 ).

Table 4 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 2 with blended learning.

Table 5 represents distance learning and indicates once again that ICT knowledge has one of the best scores. The other scores are excellent, except for participation, which is once again the worst score for this teaching modality (6.2). There is great unanimity in this value due to the rest of the statistical indicators.

Table 5 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 2 with distance education.

Table 6 from Study 2 represents the presence learning , for which the scores of 9.2, 9.2, and 9.0 were obtained for satisfaction, ICT knowledge, and participation, respectively. The remaining scores for this modality were very high. The average score in this case, among all items, was 8.8, which means that it is the highest score achieved for any teaching modality among all of our studies.

Table 6 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 2 with presence learning.

In Study 3, a comparison was made between Study 1 and Study 2, and a summary of both is provided. The following graph shows a comparison, one by one, of all items evaluated in the three teaching modalities in both studies ( Figure 4 ).

Figure 4 . Result of the items studied “Comparative of teachings in bar diagram” in Study 3. Source: Own elaboration.

The most notable evolutions are the 3.2-pp increase in ICT knowledge, the 2.2-pp increase in the innovative value of teaching practice, the 1.8-pp increase in participation, and the 1.2-pp increase in satisfaction with the presence learning in Study 2 compared with Study 1. These increases in scores will be explained in detail in the “Conclusion” section.

On the contrary, the greatest decrease in Study 2 compared with Study 1 occurred in accessibility in the blended learning modality, reaching a 2.5-pp decrease. Changes also occurred in the rest of the scores, but they were not as significant as the previous ones.

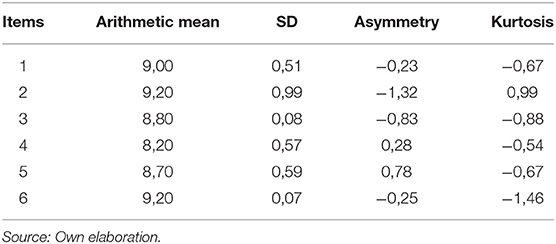

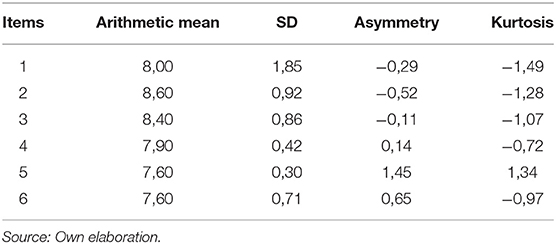

As shown in Tables 7 – 9 , the complete sample is analyzed, i.e., Study Sample 1 and Study Sample 2, which composes the complete sample of Study 3.

Table 7 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 3 with blended learning.

Table 7 shows the total scores for the entire sample for the blended learning . Its average score is 7.5, reaching its best scores in Items 5 and 6, where the innovative value is 8.25, and the value of ICT knowledge is 8.2, respectively. The worst score, i.e., the satisfaction of the students, is 7.0.

In Table 8 , the complete distance learning sample is analyzed. The best score, as in previous studies, is the knowledge of ICT, with a score of 9.8. However, the worst score is the participation of the students (6.4), and excellent statistical indicators were obtained in all the statistical items. The average value for this modality is 7.8.

Table 8 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 3 with distance education.

As shown in Table 9 of our analysis on the presence learning , all statistical values are excellent and optimal ( George and Mallery, 2011 ). The highest scores for satisfaction, participation, and accessibility stand out with 8.6, 8.4, and 8.0, respectively. In contrast, the values of innovation and ICT knowledge are each 7.6. Despite this, this modality obtains an average value of 8.0.

Table 9 . Descriptive statistical analysis of the Academic Activity Scale in Study 3 with presence learning.

The Pandemic, Teaching Methodologies, and Teaching Infrastructures

The pandemic has modified the vital context in which study plans are implemented for two reasons: First, the use of new platforms has been necessary, considering that the circumstances that have arisen require different methodologies from those used when the curriculum was originally designed. Second, both the knowledge and the professional competencies required to implement these methodologies are in the spotlight, requiring the training of professionals and students. The two universities studied, despite being face-to-face universities , have had different tools to quickly adapt to Emergency remote teaching . In both universities, while there are some online studies, professors who taught in the programs studied here had to become trained quickly because they were not professors in other online programs that continued to be taught without difficulty.

Presence learning involves contact with students, the elimination of technical difficulties, equal resources for all students, and the elimination of potential family conciliation problems for both teachers and students. In contrast, it has disadvantages as follows: the time needed to travel to the location of the class and the impossibility of connecting with students who live far from the educational center or even abroad. According to different authors, the change to online teaching has not meant a great change for many universities in the world ( Ali, 2020 ). However, the transition to the large-scale online learning is a very difficult and complex task for education systems. As a UNESCO report indicates, even under the best circumstances, it has become a necessity ( UNESCO, 2021 ).

Online classes are increasingly being held at prestigious International Universities both in America and Europe in which any subject can be carried out without face-to-face contact ( Hwang, 2018 ). The idea behind this study, echoing the proposals of Bigg, is the recognition that any discourse on change and transformations of the school and its teachers is not limited only to the school environment. The participation of the educational community and, in this specific case of the University, the process of change can be the determining factors in the success of any innovation initiative that is attempted and, in the guarantee, through innovation and the use of ICT, of high levels of satisfaction in our students ( Bigg, 2003 ; Tait, 2018 ; Bergdahl and Nouri, 2020 ; Reimers and Schleicher, 2020 ). The case of virtual teaching allows for more flexibility for learners who live in distant areas but also for teachers from different parts of the world. The platform used to broadcast classes live for the Emergency remote education (100% online or blended teaching) used in the private and public universities of this investigation was the same: Blackboard Collaborate. Blackboard Collaborate is a real-time video conferencing tool that allows one to add files, share applications, and use a virtual whiteboard to interact. One of the main advantages of Blackboard Collaborate is that one can run the application without having to install it on your computer. Blackboard opens directly in a browser without the need to install any software to join a session. The participation of the educational community and the involvement in the training of teachers in the two universities was evident. Both universities provided extensive help materials for the use of this tool, both written and in video format. In the case of the private University, a forum for interaction and the resolution of doubts was also set up. The private University provided an email to raise questions and gave live online courses for teachers.

The benefits of the blended education are for professors and students. With the potentiality of connection through the Internet, new learning possibilities arise, with added resources that help toward comfort, accessibility, effectiveness, and more options to access education. Classes in hybrid mode allow for optimization of the use of academic resources and grant control of the capacity and social distance, as there are fewer people in the classroom, such that the social distancing measures imposed by the state can be better complied with. In the case of mirror classrooms , they overcome many of the difficulties that the digital divide can cause ( Beatty, 2019 ; Binnewies and Wang, 2019 ). Although the interest of this cited study focuses on undergraduate teaching, it is necessary to carry out the same study with other University stages. Other investigators have shown that the blended learning training modality in postgraduate programs is currently in high demand in Spain, and for this reason, the academic institutions promote their programs through the Internet, intending to attract students and promote the quality of their programs and institutions ( López Catalán et al., 2018 ). According to Goodyear and other researchers, most studies highlight that hybrid learning modifies the role played by students. They take part not only as participants but also as protagonists in their learning, even becoming the co-configurators of learning environment/activities together with other apprentices ( Beatty, 2019 ; Goodyear, 2020 ; Raes et al., 2020 ).

However, we acknowledged that there is considerable discussion among researchers regarding the disadvantages of Hybrid learning . The results of blended education in 2021 are worse in the public University ( Figure 4 , Items 1–3) due to the technical problems experienced by students during their development. If the technical means are not very good, i.e., if there are failures in the cameras, the microphone, or the program used by students to connect at home, students will lose their attention and interest. If certain technical requirements are not met, it will not be an effective pedagogical method ( Hwang, 2018 ; Simpson, 2018 ; Traxler, 2018 ; Leoste et al., 2019 ; Goodyear, 2020 ; Hod and Katz, 2020 ).

In this study, we found differences between universities depending on the economic investment they had made in their facilities. In the case of the public University, the resources needed to broadcast the class from the University classroom for the blended methodology were scarce. There was no camera installed in the classroom, so the class had to be broadcast through the camera of a portable device, laptop, tablet, mobile, etc., in such a way that only one part of the class could be seen at one time, i.e., the face of the teacher or the blackboard. The private University installed high-quality cameras and microphones so that the classes could be broadcast live. The teacher just had to turn on the camera and connect to the Blackboard platform. The process was very simple. The students assessed that the quality of the media was adequate to fully follow the class from home.

There is no previous research using the Online guide classroom approach. To our knowledge, the Online guide classroom is an innovative methodology, appropriate for the times we live in, which potentially offers many advantages in the various situations studied in this research. It can be especially advantageous for confined situations, in science subjects where students need to use the laboratory, or under meteorological circumstances that make it impossible to travel to class. However, it also has shortcomings, as can occur with other blended methodologies, i.e., failures in technical infrastructure, image quality, audio, internet connection, etc., so universities need to make a stronger investment in technology. In addition, it will be necessary to have a person in charge of connecting devices and solving technical problems. This type of methodology, from our own experience, works very well in classes where students are autonomous and respectful, but it could be more complicated with less involved students.

One of the direct consequences of the pandemic has been the need, for both teachers and students, to modify teaching methodologies. During the periods in which the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 was at very high levels, it was necessary to engage in distance education or blended education, and teachers had to quickly readjust to these changes. This adaptation has meant a great enrichment of their knowledge in new didactic resources to teach their classes.

Thanks to training during the distance education and blended education classes, face-to-face teachers have learned new skills. As a result of the enrichment of their knowledge in new didactic resources, the innovation in teaching methodologies and the ICT knowledge of teachers improved due to the pandemic. In this study, Item 6, i.e., ICT Knowledge, improved 3.2 pp, and Item 5, i.e., Innovative value of teaching practice, was also better valued in 2021 because teachers learned new applications and methodologies for online and hybrid teaching that they later incorporated into face-to-face classes.

Other important aspects to consider are accessibility, participation, and satisfaction, i.e., Items 1, 2, and 3, which also improved substantially in Study 2. There was a 1.2-pp increase in satisfaction with the presence learning in Study 2 compared with Study 1. The students in Study 2, who had already experienced the restrictions and social distancing due to the pandemic, valued these items much more than the students in Study 1, which is very likely because they were able to enjoy face-to-face teaching again. Those aspects that one does not notice on a day-to-day basis may have begun to become more important once they were lost.

These results provide a basis to carefully consider this new era in higher education. We assumed that it is essential to change the paradigm of in-University education. Any subject—understood as an educational subject—should not be approached as a body of finished knowledge but as living knowledge that can be transmitted in person or not, depending on whether the context allows it. Similarly, it will be essential that teachers have enough ICT training to be able to use the most appropriate software and adapt to other pandemics that may befall society so that they can continue to provide quality education to students. It is not a problem of the satisfaction with different formats, be in-person, online, or a combination, as we have discussed previously, although most of the students state that they prefer a face-to-face format due to the interaction with their classmates, better participation in the classroom, and better understanding of the teacher. To be able to adequately follow daily teachings, there is indeed a need for the students themselves to have the necessary resources at their disposal, such as Internet connection and smart devices, so that they can connect to classes that today seem accessible to any University student of a developed country, but it will be important to provide the necessary resources for all students of any social context. Based on our experience, we supported the idea that, working together with educational centers, mixed teaching, or remote teaching are the best facilitators of learning, and neither COVID-19 nor any other pandemic can stop teaching if we have the knowledge, skills, and adequate resources.

The literature highlights deficiencies in the transition from face-to-face teaching to online teaching due to the weakness of the online teaching infrastructure, the inexperience of teachers, the digital divide, a complex home environment, etc. Although the advances in the use of educational technology support remote learning since the pandemic became a reality, the efforts to use this technology, and the large-scale advances in the distance and online education during the pandemic compel us to face an unprecedented technological revolution and take advantage of it. It is important to highlight the fact that, if the pandemic had not had this impact on education, the use of the technological evolution in educational environments might not have evolved so quickly in the last few months.

The results of the experiment show clear support for the presence learning from students in the public University, as they appeared to be more satisfied with it than with any of the other methodologies. The public University students preferred the online teaching as a second option since the quality of the class was also very high, and the blended learning was preferred the least. The satisfaction of the private University students was very similar with respect to these three teaching methods used in this University, with a slightly higher preference for face-to-face teaching.

This research provides new perspectives on a category of teaching education in the period of COVID-19. The results obtained corroborate conclusions reached by other studies ( Hwang, 2018 ; Leoste et al., 2019 ; Goodyear, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ), in which learning can be carried out in an efficient, high-quality, and satisfactory manner either through methods we choose or through methods to which the context forces us to adapt. We must choose a modality without affecting education.

Future investigations can validate the conclusions drawn from this study. In this study, we described preferences of teaching and learning modalities and showed that, although students value the possibilities of technology very positively, face-to-face communication with the teacher, to a larger degree, is believed to be required for success in their studies.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study in line with local legislation and institutional requirements. Before administering the questionnaire to the students, compliance with all the required ethical standards was ensured as follows: written informed consent, the right to information, confidentiality, anonymity, gratuity, and the option to abandon the study.

Author Contributions

AV and JMV conceptualized and wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adedoyin, O. B., and Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: a necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. High. Educ. Stud. 10, 16–25. doi: 10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

Anderton, R., Vitali, J., Blackmore, C., and Bakeberg, M. (2021). Flexible teaching and learning modalities in undergraduate science amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Educ . 5:609703. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.609703

Bao, W. (2020). COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: a case study of Peking University. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol . 2, 113–115. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.191

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Beatty, B. J. (2019). Hybrid- F lexible C ourse D esign. Implementing Student-Directed Hybrid Classes . Provo: EdTech Books.

Google Scholar

Ben-Chayim, A., and Offir, B. (2019). Model of the mediating teacher in distance learning environments: classes that combine asynchronous distance learning via videotaped lectures. J. Educ. 16:1. doi: 10.9743/jeo.2019.16.1.1

Bergdahl, N., and Nouri, J. (2020). Covid-19 and crisis-prompted distance education in Sweden. Technol. Know. Learn . 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10758-020-09470-6

Bigg, J. (2003). Teaching for Quality Learning at University . London: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Binnewies, S., and Wang, Z. (2019). “Challenges of student equity and engagement in a HyFlex course,” in Blended Learning Designs in STEM Higher Education , eds C. N. Allan, C. Campbell, and J. Crough (Singapore: Springer), 209–230. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-6982-7_12

Cândido, R. B., Yamamoto, I., and Zerbini, T. (2020). “Validating the learning strategies scale among business and management students in the semi-presential University context,” in Learning Styles and Strategies for Management Students , eds L. C. Carvalho, A. B. Noronha, and C. L. Souza (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 219–231. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-2124-3.ch013

Chick, R. C., Clifton, G. T., Peace, K. M., Propper, B. W., Hale, D. F., Alseidi, A. A., et al. (2020). Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Surg. Educ. 77, 729–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

Crisol Moya, E. (2016). Using active methodologies: the students' view. Procedia 237, 672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.040

Daniel, J. (2020). Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects 49, 91–96. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3

Dede, C. J. (1990). The evolution of distance learning. J. Res. Comput. Educ . 22, 247–264. doi: 10.1080/08886504.1990.10781919

Evans, D. J., Bay, B. H., Wilson, T. D., Smith, C. F., Lachman, N., and Pawlina, W. (2020). Going virtual to support anatomy education: a STOPGAP in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. Anat. Sci. Educ. 13, 279–283. doi: 10.1002/ase.1963

García-Peñalvo, F. J., Corell, A., Abella-García, V., and Grande-de-Prado, M. (2021). “Recommendations for mandatory online assessment in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic,” in Radical Solutions for Education in a Crisis Context , eds D. Burgos, A. Tlili, and A. Tabacco (Singapore: Springer), 85–98. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-7869-4_6

George, D., and Mallery, P. (2011). IBM SPSS Statistics 21 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference . Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Goodyear, P. (2020). Design and co-configuration for hybrid learning: theorising the practices of learning space design. Br. J. Educ. Technol . 51, 1045–1060. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12925

Heilporn, G., Lakhal, S., and Bélisle, M. (2021). An examination of teachers' strategies to foster student engagement in blended learning in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 18, 1–25. doi: 10.1186/s41239-021-00260-3

Hod, Y., and Katz, S. (2020). Fostering highly engaged knowledge building communities in socioemotional and sociocognitive hybrid learning spaces. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 51, 1117–1135. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12910

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., and Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review . Available online at: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed December 2, 2020).

Hwang, A. (2018). Online and hybrid learning. J. Manage. Educ . 42 557–563. doi: 10.1177/1052562918777550

Konopka, C. L., Adaime, M. B., and Mosele, P. H. (2015). Active teaching and learning methodologies: some considerations. Creat. Educ. 6:154. doi: 10.4236/ce.2015.614154

Lent, R., Brown, S., Sheu, H., Schmidt, J., Brenner, B., Gloster, C., et al. (2005). Social cognitive predictors of academic interests and goals in engineering: utility for women and students at historically black universities. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 84–92. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.84

Leoste, J., Tammets, K., and Ley, T. (2019). Co-creating learning designs in professional teacher education: knowledge appropriation in the teacher's innovation laboratory. IxDandA Interact. Design Arch. 42, 131–163. Available online at: http://www.mifav.uniroma2.it/inevent/events/idea2010/doc/42_7.pdf

Lightner, C. A., and Lightner-Laws, C. A. (2016). A blended model: simultaneously teaching a quantitative course traditionally, online, and remotely. Interact. Learn. Environ. 1, 224–238. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2013.841262

López Catalán, L., López Catalán, B., and Prieto Jiménez, E. (2018). Tendencias innovadoras en la formación on-line. La oferta web de postgrados e-learning y blended-learning en España. Píxel-Bit. Revista De Medios Y Educación 53, 93–107. doi: 10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i53.06

MacMillan, J. H., and Schumacher, S. (2001). Research in Education. A Conceptual Introduction . 5th Edn. Boston, MA: Longman.

Misseyanni, A., Papadopoulou, P., Marouli, C., and Lytras, M. D. (2018). Active Learning Strategies in Higher Education . Bradford: Emerald Publishing Limited. doi: 10.1108/9781787144873

Mumford, S., and Dikilitaş, K. (2020). Pre-service language teachers reflection development through online interaction in a hybrid learning course. Comput. Educ . 144:103706. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103706

Nuruzzaman, A. (2016). The pedagogy of blended learning: a brief review. IRA Int. J. Educ. Multidiscip. Stud. 4:14. doi: 10.21013/jems.v4.n1.p14

Panisoara, I. O., Lazar, I., Panisoara, G., Chirca, R., and Ursu, A. S. (2020). Motivation and continuance intention towards online instruction among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating effect of burnout and technostress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:8002. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218002

Raes, A., Detienne, L., Windey, I., and Depaepe, F. (2020). A systematic literature review on synchronous hybrid learning: gaps identified. Learn. Environ. Res. 23, 269–290. doi: 10.1007/s10984-019-09303-z

Reimers, F. M., and Schleicher, A. (2020). A framework to guide an education response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020 . OECD, Paris, 14.

Salikhova, N. R., Lynch, M. F., and Salikhova, A. B. (2020). Psychological aspects of digital learning: a self-determination theory perspective. Contemp. Educ. Technol . 12:ep280. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/8584

Sandars, J., Correia, R., Dankbaar, M., de Jong, P., Goh, P. S., Hege, I., et al. (2020). Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish 9:82. doi: 10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1

Simpson, O. (2018). Supporting Students in Online, Open and Distance Learning . London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203417003

Singh, G., and Hardaker, G. (2014). Barriers and enablers to adoption and diffusion of eLearning. Educ. Train. 56, 105–121. doi: 10.1108/ET-11-2012-0123

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., and Ullman, J. B. (2011). Using Multivariate Statistic. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Tait, A. (2018). Education for development: from distance to open education. J. Learn. Dev . 5, 101–115. Available online at: https://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/294 (accessed December 10, 2020).

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Traxler, J. (2018). Distance learning—predictions and possibilities. Educ. Sci. 8:35. doi: 10.3390/educsci8010035

UNESCO (2021). Education: From Disruption to Recovery . Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/ (accessed December 10, 2020).

Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., and Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet 395, 945–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X

Zabala, A., and Arnau, L. (2015). Métodos para la enseñanza de competencias . Barcelona: Graó.

Keywords: teaching and learning modalities, educational technology, COVID response, performance, satisfaction, ICT, teacher competencies, higher education

Citation: Verde A and Valero JM (2021) Teaching and Learning Modalities in Higher Education During the Pandemic: Responses to Coronavirus Disease 2019 From Spain. Front. Psychol. 12:648592. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648592

Received: 31 December 2020; Accepted: 16 July 2021; Published: 24 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Verde and Valero. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ana Verde, ana.verde@urjc.es

† ORCID: Ana Verde orcid.org/0000-0003-0339-0510 Jose Manuel Valero orcid.org/0000-0001-8670-8154

‡ These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Student's perspective on distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of Western Michigan University, United States

Wassnaa al-mawee.

a Department of Computer Science, Western Michigan University, 1903 W. Michigan Ave., Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5466, USA

Keneth Morgan Kwayu

b Department of Civil and Transportation Engineering, Western Michigan University, 1903 W. Michigan Ave., Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5466, USA

Tasnim Gharaibeh

As the distance learning process has become more prevalent in the USA due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to understand students’ experiences, perspectives, and preferences. Our study's purpose is to reveal students’ perspectives and preferences on distance learning due to the dramatic change that happened in the education process. Western Michigan University is used as the case study to achieve that purpose. Participants completed an online survey that investigated two measures: distance learning and instructional methods with a set of scales associated with each. Students reported negative experiences of distance learning such as lack of social interaction and positive experiences such as time and location flexibility. These findings may help WMU and higher educational institutions to improve distance learning education.

1. Introduction

The benefits and challenges of distance learning have been a subject of continuous discussion in the past. Of recent, the topic of distance learning has become more relevant and imminent due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 has compelled most of the higher education institutions to shift to either distance learning and/or some form of hybrid teaching model ( Smalley, 2020 ). This has disrupted the natural ecosystem of conventional learning environments where students live and study in close proximity. Challenges that have been raised in the previous studies about distance learning include variation in the quality of educational instructions, students’ unequal access to the essential technologies for distance learning, and technology readiness of students ( Ratliff, 2009 ). For example, one study found that 20% of students reported having issues in accessing essential technology for distance learning such as laptops and high-speed internet ( Gonzales, Calarco, & Lynch, 2018 ). Also, it has been found that students who were already suffering academically in face-to-face instruction are more likely to obtain lower grade points in distance learning ( Xu & Jaggars, 2014 ). Despite the challenges, this sudden and unexpected change in the learning environment offers opportunities for academic institutions to reimage innovative modes of learning that take advantage of the current technologies. Therefore, the challenges and opportunities of shifting from in-person instruction mode to remote/distance instruction mode need a thorough assessment. This study intends to explore the benefits and challenges of distance learning based on student's perspectives. The case study selected 5000 students randomly from all undergraduate and graduate students at Western Michigan University to participate in the survey and we got 420 responses.

2. Related work

Distance education, or remote learning, refers to technology-based teaching in which students during the entire course of learning are physically removed from teachers at a place. It is learning from outside the normal classroom and involves online education ( Lei & Gupta, 2010 ) A distance learning program can be completely distance learning, or a combination of distance learning and traditional classroom instruction (called hybrid) ( Tabor, 2007 ). This form of teaching helps teachers to access a considerably broader audience and facilitates greater versatility in the curriculum for students. Online education is a term under the distance education umbrella. It is education that takes place over the Internet. It is often referred to as “e-learning” in other terms. However, it is just one type of “distance learning”.

Many works and research were made to study the students’ perceptions of distance learning. In one of them, especially related to students’ perceived impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, Aristovnik, Keržič, Ravšelj, Tomaževič, and Umek (2020) introduced a comprehensive and large-scale study of students’ perceived impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on different aspects of their lives on a global level. Their study sample contains 30,383 students enrolled in higher education institutions, who were at least 18 years old from 62 countries, where a multi-lingual web-based comprehensive questionnaire composed of 39 predominantly closed-ended questions was used to collect the data. The questionnaire addressed socio-demographic, geographic, and other characteristics, in addition to the various features and elements of higher education student life, such as online academic work and life, emotional life, social life, personal situations, changing habits, responsibilities, as well as personal thoughts on COVID-19.

Under the online academic, as part of the distance learning, work, and life element, an ordinal logistic regression analysis was used to indicate which factors influence the students’ satisfaction with the role of the university. This logistic regression model implemented in Python programming language using libraries Pandas and Numpy which is the same language that they used to prepare, clean, and aggregate their data. The results emphasize that satisfaction with asynchronous online teaching methods such as recorded videos (p<0.001), information on exams oqr the procedure of examination in times of crisis (p<0.001), teaching staff (lecturers), and websites, social media information have a positive effect on students’ satisfaction with the role of the university during the COVID-19 pandemic. The result also showed that the students’ workload was larger or significantly larger in online teaching, in addition to some difficulty in using online teaching platforms ( Aristovnik et al., 2020 ).

On the other hand, to answer the question of how students experience distance learning, Blackmon and Major (2012) introduced an investigation using qualitative research synthesis to collect the data. They ended with 10 studies focusing on online learning. To analyze the data, they summarized the articles and extracted findings. The findings were grouped into student factors that influenced experience and instructor factors that influenced student experience. Students must combine work and families, handle time and devote themselves individually. In the absence of physical copresence, teachers can strive to develop academic relationships with students and to create a sense of community. The balance between student and teacher considerations affects the classroom and student interactions. According to their theoretical framework suggestion, the students are more abstract and understandingly observing their academic experiences. In some situations, students appeared to miss the physical markers and signals that make social interactions easier to discuss. In other situations, some students seemed to succeed in the new environment. Although the student must be responsible, the teacher also has a significant role to do to generate creative online environments that facilitate the delivery and use of new intellectual skills.

Another survey of professors, staff, and students was commissioned by Illinois Community Colleges Online in 2005 to determine the pressing concerns affecting quality, retention, and capacity building related to online learning. About one thousand people from seventeen Illinois community colleges presented data relating to these three problems over six months ( Hutti, 2007 ). Three separate methods were used in the data collection method: an electronic survey of faculty, employees, and students; a focus group including faculty, employees, and students; and interviews with select faculty, employees, and students. The findings of the review of the collected data showed that the consistency benchmarks that were most important and least important for distance learning, especially online learning, were decided by faculty, staff, and students. Using a four-point Likert Scale (Strongly Agree = 4, Agree = 3, Disagree = 2, and Strongly Disagree = 1), all three groups of respondents were asked to rate the importance of each quality benchmark. The top 5 quality benchmarks rated most important based on highest means where technical assistance in course development is available to faculty, a college-wide system (such as Blackboard or WebCT) supports and facilitates the online courses, faculty are encouraged to use technical assistance in course development, faculty give constructive feedback on student assignments and to their questions, and faculty are assisted in the transition from classroom teaching to online instruction ( Hutti, 2007 ).

To focus on a specific level college, Fedynich, Bradley and Bradley (2015) studied the graduate students’ perceptions regarding distance learning using the analysis of an online survey. Their findings indicate that the role of the teacher, the contact between students and with the teacher, and feedback and assessment were identified as being essential to the satisfaction of the students. Other difficulties found included technical support for learners connected to campus services, and the need for differing educational design and implementation to promote the ability of students to study. Students, on the other hand, were highly pleased with the consistency and organization of teaching using the right tools.