Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Stanford scholars examine systemic racism, how to advance racial justice in America

Black History Month is an opportunity to reflect on the Black experience in America and examine continuing systemic racism and discrimination in the U.S. – issues many Stanford scholars are tackling in their research and scholarship.

A pandemic that disproportionately affected communities of color, roadblocks that obstructed efforts to expand the franchise and protect voting discrimination, a growing movement to push anti-racist curricula out of schools – events over the past year have only underscored how prevalent systemic racism and bias is in America today.

What can be done to dismantle centuries of discrimination in the U.S.? How can a more equitable society be achieved? What makes racism such a complicated problem to solve? Black History Month is a time marked for honoring and reflecting on the experience of Black Americans, and it is also an opportunity to reexamine our nation’s deeply embedded racial problems and the possible solutions that could help build a more equitable society.

Stanford scholars are tackling these issues head-on in their research from the perspectives of history, education, law and other disciplines. For example, historian Clayborne Carson is working to preserve and promote the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and religious studies scholar Lerone A. Martin has joined Stanford to continue expanding access and opportunities to learn from King’s teachings; sociologist Matthew Clair is examining how the criminal justice system can end a vicious cycle involving the disparate treatment of Black men; and education scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students.

Learn more about these efforts and other projects examining racism and discrimination in areas like health and medicine, technology and the workplace below.

Update: Jan. 27, 2023: This story was originally published on Feb. 16, 2021, and has been updated on a number of occasions to include new content.

Understanding the impact of racism; advancing justice

One of the hardest elements of advancing racial justice is helping everyone understand the ways in which they are involved in a system or structure that perpetuates racism, according to Stanford legal scholar Ralph Richard Banks.

“The starting point for the center is the recognition that racial inequality and division have long been the fault line of American society. Thus, addressing racial inequity is essential to sustaining our nation, and furthering its democratic aspirations,” said Banks , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and co-founder of the Stanford Center for Racial Justice .

This sentiment was echoed by Stanford researcher Rebecca Hetey . One of the obstacles in solving inequality is people’s attitudes towards it, Hetey said. “One of the barriers of reducing inequality is how some people justify and rationalize it.”

How people talk about race and stereotypes matters. Here is some of that scholarship.

For Black Americans, COVID-19 is quickly reversing crucial economic gains

Research co-authored by SIEPR’s Peter Klenow and Chad Jones measures the welfare gap between Black and white Americans and provides a way to analyze policies to narrow the divide.

How an ‘impact mindset’ unites activists of different races

A new study finds that people’s involvement with Black Lives Matter stems from an impulse that goes beyond identity.

For democracy to work, racial inequalities must be addressed

The Stanford Center for Racial Justice is taking a hard look at the policies perpetuating systemic racism in America today and asking how we can imagine a more equitable society.

The psychological toll of George Floyd’s murder

As the nation mourned the death of George Floyd, more Black Americans than white Americans felt angry or sad – a finding that reveals the racial disparities of grief.

Seven factors contributing to American racism

Of the seven factors the researchers identified, perhaps the most insidious is passivism or passive racism, which includes an apathy toward systems of racial advantage or denial that those systems even exist.

Scholars reflect on Black history

Humanities and social sciences scholars reflect on “Black history as American history” and its impact on their personal and professional lives.

The history of Black History Month

It's February, so many teachers and schools are taking time to celebrate Black History Month. According to Stanford historian Michael Hines, there are still misunderstandings and misconceptions about the past, present, and future of the celebration.

Numbers about inequality don’t speak for themselves

In a new research paper, Stanford scholars Rebecca Hetey and Jennifer Eberhardt propose new ways to talk about racial disparities that exist across society, from education to health care and criminal justice systems.

Changing how people perceive problems

Drawing on an extensive body of research, Stanford psychologist Gregory Walton lays out a roadmap to positively influence the way people think about themselves and the world around them. These changes could improve society, too.

Welfare opposition linked to threats of racial standing

Research co-authored by sociologist Robb Willer finds that when white Americans perceive threats to their status as the dominant demographic group, their resentment of minorities increases. This resentment leads to opposing welfare programs they believe will mainly benefit minority groups.

Conversations about race between Black and white friends can feel risky, but are valuable

New research about how friends approach talking about their race-related experiences with each other reveals concerns but also the potential that these conversations have to strengthen relationships and further intergroup learning.

Defusing racial bias

Research shows why understanding the source of discrimination matters.

Many white parents aren’t having ‘the talk’ about race with their kids

After George Floyd’s murder, Black parents talked about race and racism with their kids more. White parents did not and were more likely to give their kids colorblind messages.

Stereotyping makes people more likely to act badly

Even slight cues, like reading a negative stereotype about your race or gender, can have an impact.

Why white people downplay their individual racial privileges

Research shows that white Americans, when faced with evidence of racial privilege, deny that they have benefited personally.

Clayborne Carson: Looking back at a legacy

Stanford historian Clayborne Carson reflects on a career dedicated to studying and preserving the legacy of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

How race influences, amplifies backlash against outspoken women

When women break gender norms, the most negative reactions may come from people of the same race.

Examining disparities in education

Scholar Subini Ancy Annamma is studying ways to make education more equitable for historically marginalized students. Annamma’s research examines how schools contribute to the criminalization of Black youths by creating a culture of punishment that penalizes Black children more harshly than their white peers for the same behavior. Her work shows that youth of color are more likely to be closely watched, over-represented in special education, and reported to and arrested by police.

“These are all ways in which schools criminalize Black youth,” she said. “Day after day, these things start to sediment.”

That’s why Annamma has identified opportunities for teachers and administrators to intervene in these unfair practices. Below is some of that research, from Annamma and others.

New ‘Segregation Index’ shows American schools remain highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and economic status

Researchers at Stanford and USC developed a new tool to track neighborhood and school segregation in the U.S.

New evidence shows that school poverty shapes racial achievement gaps

Racial segregation leads to growing achievement gaps – but it does so entirely through differences in school poverty, according to new research from education Professor Sean Reardon, who is launching a new tool to help educators, parents and policymakers examine education trends by race and poverty level nationwide.

School closures intensify gentrification in Black neighborhoods nationwide

An analysis of census and school closure data finds that shuttering schools increases gentrification – but only in predominantly Black communities.

Ninth-grade ethnic studies helped students for years, Stanford researchers find

A new study shows that students assigned to an ethnic studies course had longer-term improvements in attendance and graduation rates.

Teaching about racism

Stanford sociologist Matthew Snipp discusses ways to educate students about race and ethnic relations in America.

Stanford scholar uncovers an early activist’s fight to get Black history into schools

In a new book, Assistant Professor Michael Hines chronicles the efforts of a Chicago schoolteacher in the 1930s who wanted to remedy the portrayal of Black history in textbooks of the time.

How disability intersects with race

Professor Alfredo J. Artiles discusses the complexities in creating inclusive policies for students with disabilities.

Access to program for black male students lowered dropout rates

New research led by Stanford education professor Thomas S. Dee provides the first evidence of effectiveness for a district-wide initiative targeted at black male high school students.

How school systems make criminals of Black youth

Stanford education professor Subini Ancy Annamma talks about the role schools play in creating a culture of punishment against Black students.

Reducing racial disparities in school discipline

Stanford psychologists find that brief exercises early in middle school can improve students’ relationships with their teachers, increase their sense of belonging and reduce teachers’ reports of discipline issues among black and Latino boys.

Science lessons through a different lens

In his new book, Science in the City, Stanford education professor Bryan A. Brown helps bridge the gap between students’ culture and the science classroom.

Teachers more likely to label black students as troublemakers, Stanford research shows

Stanford psychologists Jennifer Eberhardt and Jason Okonofua experimentally examined the psychological processes involved when teachers discipline black students more harshly than white students.

Why we need Black teachers

Travis Bristol, MA '04, talks about what it takes for schools to hire and retain teachers of color.

Understanding racism in the criminal justice system

Research has shown that time and time again, inequality is embedded into all facets of the criminal justice system. From being arrested to being charged, convicted and sentenced, people of color – particularly Black men – are disproportionately targeted by the police.

“So many reforms are needed: police accountability, judicial intervention, reducing prosecutorial power and increasing resources for public defenders are places we can start,” said sociologist Matthew Clair . “But beyond piecemeal reforms, we need to continue having critical conversations about transformation and the role of the courts in bringing about the abolition of police and prisons.”

Clair is one of several Stanford scholars who have examined the intersection of race and the criminal process and offered solutions to end the vicious cycle of racism. Here is some of that work.

Police Facebook posts disproportionately highlight crimes involving Black suspects, study finds

Researchers examined crime-related posts from 14,000 Facebook pages maintained by U.S. law enforcement agencies and found that Facebook users are exposed to posts that overrepresent Black suspects by 25% relative to local arrest rates.

Supporting students involved in the justice system

New data show that a one-page letter asking a teacher to support a youth as they navigate the difficult transition from juvenile detention back to school can reduce the likelihood that the student re-offends.

Race and mass criminalization in the U.S.

Stanford sociologist discusses how race and class inequalities are embedded in the American criminal legal system.

New Stanford research lab explores incarcerated students’ educational paths

Associate Professor Subini Annamma examines the policies and practices that push marginalized students out of school and into prisons.

Derek Chauvin verdict important, but much remains to be done

Stanford scholars Hakeem Jefferson, Robert Weisberg and Matthew Clair weigh in on the Derek Chauvin verdict, emphasizing that while the outcome is important, much work remains to be done to bring about long-lasting justice.

A ‘veil of darkness’ reduces racial bias in traffic stops

After analyzing 95 million traffic stop records, filed by officers with 21 state patrol agencies and 35 municipal police forces from 2011 to 2018, researchers concluded that “police stops and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias.”

Stanford big data study finds racial disparities in Oakland, Calif., police behavior, offers solutions

Analyzing thousands of data points, the researchers found racial disparities in how Oakland officers treated African Americans on routine traffic and pedestrian stops. They suggest 50 measures to improve police-community relations.

Race and the death penalty

As questions about racial bias in the criminal justice system dominate the headlines, research by Stanford law Professor John J. Donohue III offers insight into one of the most fraught areas: the death penalty.

Diagnosing disparities in health, medicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted communities of color and has highlighted the health disparities between Black Americans, whites and other demographic groups.

As Iris Gibbs , professor of radiation oncology and associate dean of MD program admissions, pointed out at an event sponsored by Stanford Medicine: “We need more sustained attention and real action towards eliminating health inequities, educating our entire community and going beyond ‘allyship,’ because that one fizzles out. We really do need people who are truly there all the way.”

Below is some of that research as well as solutions that can address some of the disparities in the American healthcare system.

Stanford researchers testing ways to improve clinical trial diversity

The American Heart Association has provided funding to two Stanford Medicine professors to develop ways to diversify enrollment in heart disease clinical trials.

Striking inequalities in maternal and infant health

Research by SIEPR’s Petra Persson and Maya Rossin-Slater finds wealthy Black mothers and infants in the U.S. fare worse than the poorest white mothers and infants.

More racial diversity among physicians would lead to better health among black men

A clinical trial in Oakland by Stanford researchers found that black men are more likely to seek out preventive care after being seen by black doctors compared to non-black doctors.

A better measuring stick: Algorithmic approach to pain diagnosis could eliminate racial bias

Traditional approaches to pain management don’t treat all patients the same. AI could level the playing field.

5 questions: Alice Popejoy on race, ethnicity and ancestry in science

Alice Popejoy, a postdoctoral scholar who studies biomedical data sciences, speaks to the role – and pitfalls – of race, ethnicity and ancestry in research.

Stanford Medicine community calls for action against racial injustice, inequities

The event at Stanford provided a venue for health care workers and students to express their feelings about violence against African Americans and to voice their demands for change.

Racial disparity remains in heart-transplant mortality rates, Stanford study finds

African-American heart transplant patients have had persistently higher mortality rates than white patients, but exactly why still remains a mystery.

Finding the COVID-19 Victims that Big Data Misses

Widely used virus tracking data undercounts older people and people of color. Scholars propose a solution to this demographic bias.

Studying how racial stressors affect mental health

Farzana Saleem, an assistant professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education, is interested in the way Black youth and other young people of color navigate adolescence—and the racial stressors that can make the journey harder.

Infants’ race influences quality of hospital care in California

Disparities exist in how babies of different racial and ethnic origins are treated in California’s neonatal intensive care units, but this could be changed, say Stanford researchers.

Immigrants don’t move state-to-state in search of health benefits

When states expand public health insurance to include low-income, legal immigrants, it does not lead to out-of-state immigrants moving in search of benefits.

Excess mortality rates early in pandemic highest among Blacks

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been starkly uneven across race, ethnicity and geography, according to a new study led by SHP's Maria Polyakova.

Decoding bias in media, technology

Driving Artificial Intelligence are machine learning algorithms, sets of rules that tell a computer how to solve a problem, perform a task and in some cases, predict an outcome. These predictive models are based on massive datasets to recognize certain patterns, which according to communication scholar Angele Christin , sometimes come flawed with human bias .

“Technology changes things, but perhaps not always as much as we think,” Christin said. “Social context matters a lot in shaping the actual effects of the technological tools. […] So, it’s important to understand that connection between humans and machines.”

Below is some of that research, as well as other ways discrimination unfolds across technology, in the media, and ways to counteract it.

IRS disproportionately audits Black taxpayers

A Stanford collaboration with the Department of the Treasury yields the first direct evidence of differences in audit rates by race.

Automated speech recognition less accurate for blacks

The disparity likely occurs because such technologies are based on machine learning systems that rely heavily on databases of English as spoken by white Americans.

New algorithm trains AI to avoid bad behaviors

Robots, self-driving cars and other intelligent machines could become better-behaved thanks to a new way to help machine learning designers build AI applications with safeguards against specific, undesirable outcomes such as racial and gender bias.

Stanford scholar analyzes responses to algorithms in journalism, criminal justice

In a recent study, assistant professor of communication Angèle Christin finds a gap between intended and actual uses of algorithmic tools in journalism and criminal justice fields.

Move responsibly and think about things

In the course CS 181: Computers, Ethics and Public Policy , Stanford students become computer programmers, policymakers and philosophers to examine the ethical and social impacts of technological innovation.

Homicide victims from Black and Hispanic neighborhoods devalued

Social scientists found that homicide victims killed in Chicago’s predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods received less news coverage than those killed in mostly white neighborhoods.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

AI Index Diversity Report: An Unmoving Needle

Stanford HAI’s 2021 AI Index reveals stalled progress in diversifying AI and a scarcity of the data needed to fix it.

Identifying discrimination in the workplace and economy

From who moves forward in the hiring process to who receives funding from venture capitalists, research has revealed how Blacks and other minority groups are discriminated against in the workplace and economy-at-large.

“There is not one silver bullet here that you can walk away with. Hiring and retention with respect to employee diversity are complex problems,” said Adina Sterling , associate professor of organizational behavior at the Graduate School of Business (GSB).

Sterling has offered a few places where employers can expand employee diversity at their companies. For example, she suggests hiring managers track data about their recruitment methods and the pools that result from those efforts, as well as examining who they ultimately hire.

Here is some of that insight.

How To: Use a Scorecard to Evaluate People More Fairly

A written framework is an easy way to hold everyone to the same standard.

Archiving Black histories of Silicon Valley

A new collection at Stanford Libraries will highlight Black Americans who helped transform California’s Silicon Valley region into a hub for innovation, ideas.

Race influences professional investors’ judgments

In their evaluations of high-performing venture capital funds, professional investors rate white-led teams more favorably than they do black-led teams with identical credentials, a new Stanford study led by Jennifer L. Eberhardt finds.

Who moves forward in the hiring process?

People whose employment histories include part-time, temporary help agency or mismatched work can face challenges during the hiring process, according to new research by Stanford sociologist David Pedulla.

How emotions may result in hiring, workplace bias

Stanford study suggests that the emotions American employers are looking for in job candidates may not match up with emotions valued by jobseekers from some cultural backgrounds – potentially leading to hiring bias.

Do VCs really favor white male founders?

A field experiment used fake emails to measure gender and racial bias among startup investors.

Can you spot diversity? (Probably not)

New research shows a “spillover effect” that might be clouding your judgment.

Can job referrals improve employee diversity?

New research looks at how referrals impact promotions of minorities and women.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

For Black History Month, a look at what Black Americans say is needed to overcome racial inequality

Black History Month originated in 1926 as Negro History Week. Created by Carter G. Woodson, a Black historian and journalist, the week celebrated the achievements of Black Americans following their emancipation from slavery.

Since 1928, the organization that Woodson founded, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, has selected an annual theme for the celebration . The theme for 2023, “Black Resistance,” is intended to highlight how Black Americans have fought against racial inequality.

Black Americans’ resistance to racial inequality has deep roots in U.S. history and has taken many forms – from slave rebellions during the colonial era and through the Civil War to protest movements in the 1950s, ’60s and today. But Black Americans have also built institutions to support their communities such as churches, colleges and universities, printing presses, and fraternal organizations. These movements and institutions have stressed the importance of freedom, self-determination and equal protection under the law.

Black Americans have long articulated a clear vision for the kind of social change that would improve their lives. Here are key findings from Pew Research Center surveys that explore Black Americans’ views about how to overcome racial inequality.

This analysis examines how Black people view issues of racial inequality and social change in the U.S. It is part of a larger Pew Research Center project that aims to understand Americans’ views of racial inequity and social change in the United States.

For this analysis, we surveyed 3,912 Black U.S. adults from Oct. 4-17, 2021. Black U.S. adults include those who are single-race, non-Hispanic Black Americans; multiracial, non-Hispanic Black Americans; and adults who indicate they are Black and Hispanic. The survey includes 1,025 Black adults on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and 2,887 Black adults on Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Recruiting panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling).

Here are the questions used for the survey, along with responses, and its methodology .

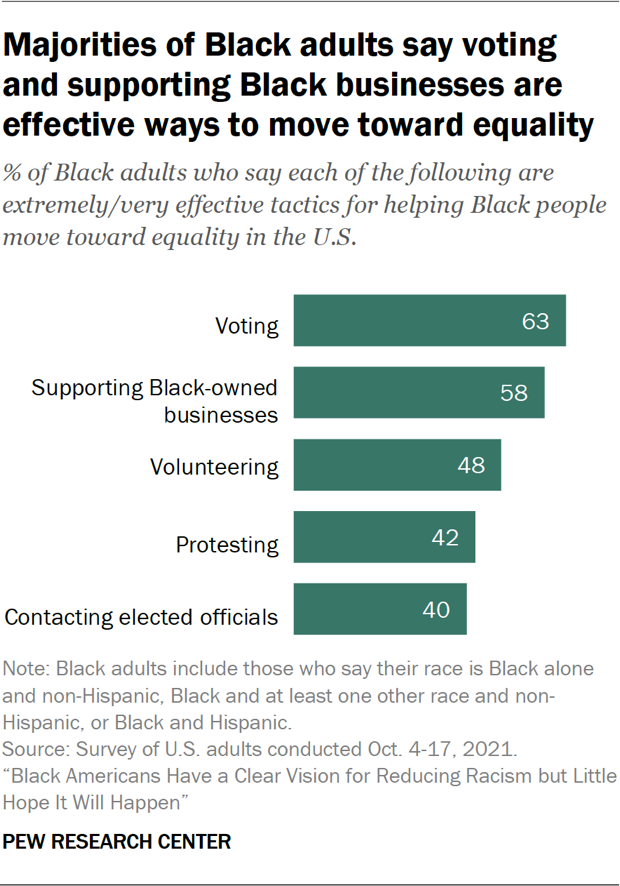

Most Black adults see voting as an extremely or very effective strategy for helping Black people move toward equality, but fewer than half say the same about protesting. More than six-in-ten Black adults (63%) say voting is an extremely or very effective strategy for Black progress. However, only around four-in-ten (42%) say the same about protesting.

There are notable differences in these views across political and demographic subgroups of the Black population.

Black Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are more likely than Black Republicans and Republican leaners to say voting is an extremely or very effective tactic for Black progress (68% vs. 46%). Black Democrats are also more likely to say the same about supporting Black businesses (63% vs. 41%) and protesting (46% vs. 32%).

Views also differ by age. For example, around half of Black adults ages 65 and older (48%) say protests are an extremely or very effective tactic, compared with 42% of those ages 50 to 64 and 38% of those 30 to 49.

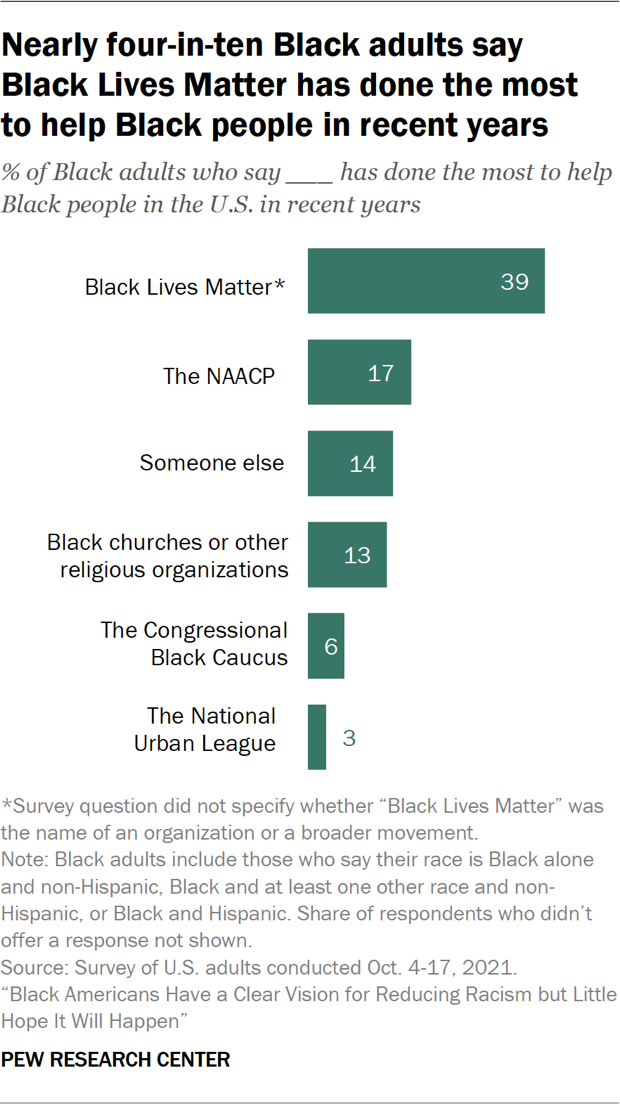

Black Americans say Black Lives Matter has done the most to help Black people in recent years. Around four-in-ten Black adults (39%) say this, exceeding the share who point to the NAACP (17%), Black churches or other religious organizations (13%), the Congressional Black Caucus (6%) and the National Urban League (3%).

Black Democrats are more likely than Black Republicans (44% vs. 26%) to say Black Lives Matter has done the most to help Black people in recent years. And Black adults with at least a college degree are more likely than those with less education (44% vs. 37%) to say Black Lives Matter has done the most.

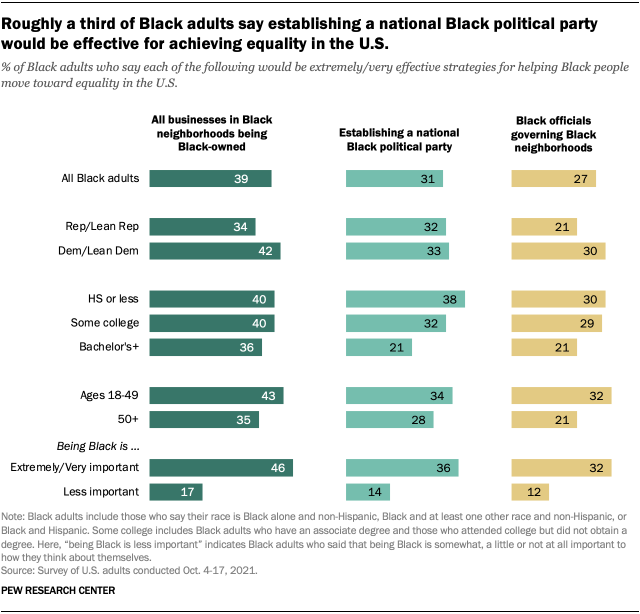

Some Black adults see Black-owned businesses and Black-led communities as effective remedies for inequality. When it comes to moving Black people toward equality, about four-in-ten Black adults (39%) say having all businesses in Black neighborhoods be owned by Black people would be an extremely or very effective strategy. Smaller shares say the same about establishing a national Black political party (31%) and having all the elected officials governing Black neighborhoods be Black (27%).

While none of these strategies have majority support among Black adults, certain groups are more likely than others to say they would be effective. Those who say being Black is at least very important to their identity are especially likely to say each of the three strategies are effective, for example.

Those with a high school education or less are more likely than college graduates to say establishing a national Black political party would be effective at achieving equality for Black people. Meanwhile, younger Black adults (ages 18 to 49) are more likely than older ones (50 and older) to say Black officials governing Black neighborhoods would help make progress toward equality.

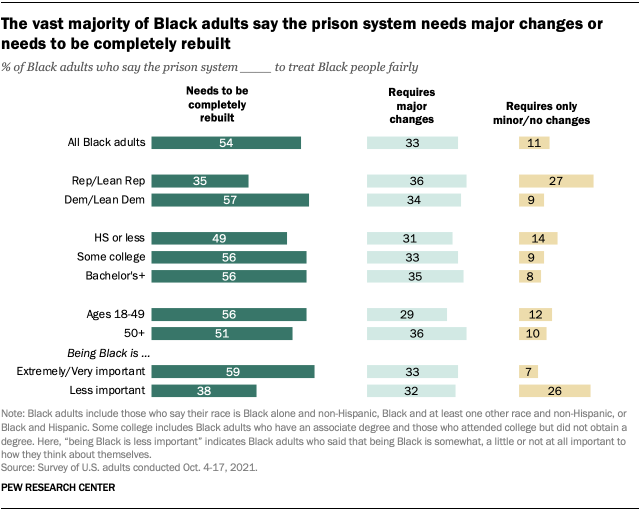

The vast majority of Black adults say the prison system needs significant changes for Black people to be treated fairly. That includes a majority of Black adults (54%) who say the prison system needs to be “completely rebuilt” in order to ensure fair treatment. Groups especially likely to say this include Black Democrats and those who say being Black is extremely or very important to how they see themselves.

Far smaller shares of Black adults say the prison system requires only minor or no changes, though this view is more common among Black Republicans and those who say being Black is somewhat, a little or not at all important to their identity.

Clear majorities of Black adults say people of other races or ethnicities could make good political allies for Black people. About four-in-ten Black adults (42%) say White people would make good political allies only if they experience the same hardships as Black people; another 35% say White people would make good political allies even if they don’t experience these same hardships. Around one-in-five Black adults (18%) say White people would not make good political allies.

About four-in-ten Black adults (37%) say Latinos would make good allies only if they experience the same hardships as Black people, while a similar share (40%) say Latino people would make for good allies even if they don’t experience the same hardships. Some 16% of Black adults say Latinos would not make good political allies.

The views of Black adults on this question are similar when it comes to Asian people, though a somewhat higher share (23%) say Asian Americans would not make good political allies.

Note: Here are the questions used for the survey, along with responses, and its methodology .

- Black Americans

- Criminal Justice

- Race, Ethnicity & Politics

- Racial Bias & Discrimination

Jens Manuel Krogstad is a senior writer and editor at Pew Research Center

Kiana Cox is a senior researcher focusing on race and ethnicity at Pew Research Center

A look at Black-owned businesses in the U.S.

8 facts about black americans and the news, black americans’ views on success in the u.s., among black adults, those with higher incomes are most likely to say they are happy, fewer than half of black americans say the news often covers the issues that are important to them, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

5 Essays to Learn More About Equality

“Equality” is one of those words that seems simple, but is more complicated upon closer inspection. At its core, equality can be defined as “the state of being equal.” When societies value equality, their goals include racial, economic, and gender equality . Do we really know what equality looks like in practice? Does it mean equal opportunities, equal outcomes, or both? To learn more about this concept, here are five essays focusing on equality:

“The Equality Effect” (2017) – Danny Dorling

In this essay, professor Danny Dorling lays out why equality is so beneficial to the world. What is equality? It’s living in a society where everyone gets the same freedoms, dignity, and rights. When equality is realized, a flood of benefits follows. Dorling describes the effect of equality as “magical.” Benefits include happier and healthier citizens, less crime, more productivity, and so on. Dorling believes the benefits of “economically equitable” living are so clear, change around the world is inevitable. Despite the obvious conclusion that equality creates a better world, progress has been slow. We’ve become numb to inequality. Raising awareness of equality’s benefits is essential.

Danny Dorling is the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford. He has co-authored and authored a handful of books, including Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration—and Why It’s Good for the Planet, the Economy, and Our Lives . “The Equality Effect” is excerpted from this book. Dorling’s work focuses on issues like health, education, wealth, poverty, and employment.

“The Equality Conundrum” (2020) – Joshua Rothman

Originally published as “Same Difference” in the New Yorker’s print edition, this essay opens with a story. A couple plans on dividing their money equally among their children. However, they realize that to ensure equal success for their children, they might need to start with unequal amounts. This essay digs into the complexity of “equality.” While inequality is a major concern for people, most struggle to truly define it. Citing lectures, studies, philosophy, religion, and more, Rothman sheds light on the fact that equality is not a simple – or easy – concept.

Joshua Rothman has worked as a writer and editor of The New Yorker since 2012. He is the ideas editor of newyorker.com.

“Why Understanding Equity vs Equality in Schools Can Help You Create an Inclusive Classroom” (2019) – Waterford.org

Equality in education is critical to society. Students that receive excellent education are more likely to succeed than students who don’t. This essay focuses on the importance of equity, which means giving support to students dealing with issues like poverty, discrimination and economic injustice. What is the difference between equality and equity? What are some strategies that can address barriers? This essay is a great introduction to the equity issues teachers face and why equity is so important.

Waterford.org is a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving equity and education in the United States. It believes that the educational experiences children receive are crucial for their future. Waterford.org was founded by Dr. Dustin Heuston.

“What does equality mean to me?” (2020) – Gabriela Vivacqua and Saddal Diab

While it seems simple, the concept of equality is complex. In this piece posted by WFP_Africa on the WFP’s Insight page, the authors ask women from South Sudan what equality means to them. Half of South Sudan’s population consists of women and girls. Unequal access to essentials like healthcare, education, and work opportunities hold them back. Complete with photographs, this short text gives readers a glimpse into interpretations of equality and what organizations like the World Food Programme are doing to tackle gender inequality.

As part of the UN, the World Food Programme is the world’s largest humanitarian organization focusing on hunger and food security . It provides food assistance to over 80 countries each year.

“Here’s How Gender Equality is Measured” (2020) – Catherine Caruso

Gender inequality is one of the most discussed areas of inequality. Sobering stats reveal that while progress has been made, the world is still far from realizing true gender equality. How is gender equality measured? This essay refers to the Global Gender Gap report ’s factors. This report is released each year by the World Economic Forum. The four factors are political empowerment, health and survival, economic participation and opportunity, and education. The author provides a brief explanation of each factor.

Catherine Caruso is the Editorial Intern at Global Citizen, a movement committed to ending extreme poverty by 2030. Previously, Caruso worked as a writer for Inquisitr. Her English degree is from Syracuse University. She writes stories on health, the environment, and citizenship.

You may also like

15 Examples of Gender Inequality in Everyday Life

11 Approaches to Alleviate World Hunger

15 Facts About Malala Yousafzai

12 Ways Poverty Affects Society

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

Top 20 Issues Women Are Facing Today

Top 20 Issues Children Are Facing Today

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Scott Atlas

- Thomas Sargent

- Stephen Kotkin

- Michael McConnell

- Morris P. Fiorina

- John F. Cogan

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- National Security, Technology & Law

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Pacific Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press, america’s struggle for racial equality.

Recapturing civil rights leaders’ commitment to ending discrimination

O n June 11, 1963, in the wake of Governor George Wallace’s stand against integration at the University of Alabama, President John F. Kennedy reported to the American people on the state of civil rights in the nation. He called on Congress to pass legislation dismantling the system of segregation and encouraged lawmakers to make a commitment "to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law."

Invoking the equality of all Americans before the law, Kennedy said: "We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and it is as clear as the American Constitution. The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated."

The American people are now beginning a great debate over the use of race and gender preferences by federal, state, and local governments. In 1996, a majority of voters in California, including 29 percent of blacks, approved the California Civil Rights Initiative prohibiting preferential treatment in public employment, education, and contracting. In a series of cases, the Supreme Court and federal courts of appeal have made it clear that the system of preference is built on an exceedingly shaky foundation. These cases--chiefly the Adarand decision of 1995--establish that racial classifications are presumptively unconstitutional and will be permitted only in extraordinary circumstances. In 1998, Congress is likely to consider legislation to end the use of race and gender preferences by the federal government.

As we enter this debate, Kennedy’s stirring words on civil rights are as important as they were in 1963. In the name of overcoming discrimination, our government for the past generation has been treating Americans of different races unequally. This is not the first time that American governments have intentionally discriminated. The institution of slavery and Jim Crow laws both violated the fundamental American tenet that "all men are created equal" and are "endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights." But racial preferences designed to compensate for prior discrimination are also inconsistent with our most deeply cherished principles.

Slavery was the single greatest injustice in American history. The conflict sparked by its existence and by efforts to expand it took 365,000 American lives. A system of ferocious violence that degraded human beings to the status of chattel, American slavery had at its core the belief that blacks were subhuman. It was an institution that systematically and wantonly trampled on the most basic of human relations: Husband was separated from wife, parent was separated from child. Liberty was denied to individuals solely by reason of race.

When this disgraceful chapter in our history came to an end, it left a legacy of racism that has afflicted America up to the present generation. Soon after the Civil War, that legacy found expression in the segregation statutes, also known as Jim Crow laws. Historian C. Vann Woodward describes segregation thus: "That code lent the sanction of law to a social ostracism that extended to churches and schools, to housing and jobs, to eating and drinking. Whether by law or by custom, that ostracism extended to virtually all forms of public transportation, to sports and recreations, to hospitals, orphanages, prisons, and asylums, and ultimately to funeral homes, morgues, and cemeteries."

Woodward continues, "The Jim Crow laws, unlike feudal laws, did not assign the subordinated group a fixed status in society. They were constantly pushing the Negro farther down." Woodward also documents the "total disfranchisement" of black voters in the South through the poll tax and the white primary. He quotes Edgar Gardner Murphy on the attitude of many southern whites that energized the system of segregation during the first half of the 20th century: "Its spirit is that of an all-absorbing autocracy of race, an animus of aggrandizement which makes, in the imagination of the white man, an absolute identification of the stronger race with the being of the state."

A Question of Dignity

The civil-rights movement of the 1950s and the early 1960s arose to combat racist laws, racist institutions, and racist practices wherever they existed. The story of that movement is a glorious chapter in the history of America. Sparked by the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) , the civil rights movement dealt a death blow to the system of segregation with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 soon followed, creating the basis for fully restoring the franchise to black Americans throughout the country.

The moral example of those who stood against the forces of racial injustice played a critical role in reshaping American attitudes toward race. The American people were moved by images of the terrible acts of violence and gross indignities visited on black Americans.

Moreover, the civil-rights movement embodied a fundamental message that touched the soul of the American people. It exemplified an ideal at the core of the American experience from the very beginning of our national life, an ideal that was never fully realized and sometimes tragically perverted, but always acknowledged by Americans.

The ideal of respect for the dignity of the individual was set forth in the Declaration of Independence: "[A]ll men are created equal" and are "endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights." At Independence Hall on the eve of the Civil War, Lincoln spoke of this ideal as "a great principle or idea" in the Declaration of Independence "which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance." This ideal undergirded the civil-rights movement and condemned the contradictions of America’s segregated society.

This ideal has never been more eloquently expressed than by Martin Luther King Jr., who said, the "image of God . . . is universally shared in equal portions by all men. There is no graded scale of essential worth. Every human being has etched in his personality the indelible stamp of the Creator. . . . The worth of an individual does not lie in the measure of his intellect, his racial origin, or his social position. Human worth lies in relatedness to God. Whenever this is recognized, ‘whiteness’ and ‘blackness’ pass away as determinants in a relationship and ‘son’ and ‘brother’ are substituted."

King explicitly linked this religious view of man to the philosophical foundation of the United States. America’s "pillars," King said, "were soundly grounded in the insights of our Judeo-Christian heritage: All men are made in the image of God; all men are brothers; all men are created equal; every man is heir to a legacy of dignity and worth; every man has rights that are neither conferred by nor derived from the state, they are God-given. What a marvelous foundation for any home! What a glorious place to inhabit!"

In light of King’s personal experiences and the contradiction of sanctioning slavery and segregation in a country committed to equality, this is a remarkably optimistic view of the American experience. It is a view that propelled the civil-rights movement to great victories.

An Animating Principle

This understanding of the dignity of the individual found concrete expression in a legal principle that was relentlessly pursued by the early civil-rights movement. If universally adopted, this principle would fulfill the promise of American ideals. It was eloquently stated by the first Justice Harlan in his dissent to the Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) . In words that would often be cited by those seeking to overthrow the odious Jim Crow system, Harlan pronounced, "Our Constitution is color blind. . . . The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the Supreme law of the land are involved."

The colorblind principle articulated by Harlan was the touchstone of the American civil-rights movement until the mid-1960s. Emory law professor Andrew Kull, in his admirable history The Color-Blind Constitution , identifies the centrality of the colorblind principle to the movement: "The undeniable fact is that over a period of some 125 years ending only in the late 1960s, the American civil-rights movement first elaborated, then held as its unvarying political objective, a rule of law requiring the color-blind treatment of individuals."

This fact is well illustrated by the example of Thurgood Marshall. In 1947, Marshall, representing the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Education Fund, in a brief for a black student denied admission to the University of Oklahoma’s segregated law school, stated the colorblind principle unequivocally: "Classifications and distinctions based on race or color have no moral or legal validity in our society. They are contrary to our constitution and laws."

Marshall’s support for the colorblind principle--which he later abandoned--is vividly described by Constance Baker Motley, senior U.S. district judge for the Southern District of New York, in an account included in Tinsley Yarbrough’s biography of Justice Harlan. Motley recalled her days working with Marshall at the NAACP: "Marshall had a ‘Bible’ to which he turned during his most depressed moments. . . . Marshall would read aloud passages from Harlan’s amazing dissent. I do not believe we ever filed a major brief in the pre-Brown days in which a portion of that opinion was not quoted. Marshall’s favorite quotation was, ‘Our Constitution is color-blind.’ It became our basic creed."

The principle of colorblind justice ultimately did find clear expression in the law of the United States. By passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress acted decisively against the Jim Crow system, and established a national policy against discrimination based on race and sex. It is the supreme irony of the modern civil-rights movement that this crowning achievement was soon followed by the creation of a system of preferences based first on race and then extended to gender.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was an unequivocal statement that Americans should be treated as individuals and not as members of racial and gender groups. Congress rejected the racism of America’s past. Under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, no American would be subject to discrimination. And there was no question about what discrimination meant. Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota--the chief Senate sponsor of the legislation--stated it as clearly as possible: Discrimination was any "distinction in treatment given to different individuals because of their different race."

Was This Enough?

As the Civil Rights Act was being considered, some voices questioned the adequacy of the principle of colorblind justice. The Urban League’s Whitney Young said that "300 years of deprivation" called for "a decade of discrimination in favor of Negro youth." James Farmer, a founder of the Congress of Racial Equality, called for "compensatory preferential treatment." Farmer said "it was impossible" for an "employer to be oblivious to color because we had all grown up in a racist society." But Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, in an encounter with Farmer, summed up the traditional view of the civil-rights movement: "I have a problem with that whole concept. What you’re asking for there is not equal treatment, but special treatment to make up for the unequal treatment of the past. I think that’s outside the American tradition and the country won’t buy it. I don’t feel at all comfortable asking for any special treatment; I just want to be treated like everyone else."

While considering the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress itself debated the issues of racial preferences and proportional representation. The result of that debate was the adoption of Section 703(j) of the Act, which states that nothing in Title VII of the Act "shall be interpreted to require any employer . . . to grant preferential treatment to any individual or group because of the race . . . of such individual or group" in order to maintain a racial balance. Senators Joseph Clark of Pennsylvania and Clifford Case of New Jersey, who steered that section of Title VII through the legislative process, left no doubt about Congress’s intent. "[A]ny deliberate attempt to maintain a racial balance," they said at the time, "whatever such a balance may be, would involve a violation of Title VII because maintaining such a balance would require an employer to hire or refuse to hire on the basis of race. It must be emphasized that discrimination is prohibited to any individual."

For a brief, shining moment, the principle of colorblind justice was recognized as the law of the land. But soon that principle was thrust aside to make way for a system of race-based entitlement. The critical events took place during the Nixon administration, when the so-called Philadelphia Plan was adopted. It became the prototypical program of racial preferences for federal contractors.

In February 1970, the U.S. Department of Labor issued an order that the affirmative-action programs adopted by all government contractors must include "goals and timetables to which the contractor’s good faith efforts must be directed to correct . . . deficiencies" in the "utilization of minority groups." This construct of goals and timetables to ensure the proper utilization of minority groups clearly envisioned a system of proportional representation in which group identity would be a factor--often the decisive factor--in hiring decisions. Embodied in this bureaucratic verbiage was a policy requiring that distinctions in treatment be made on the basis of race.

Discrimination of a most flagrant kind is now practiced at the federal, state, and local levels. A white teacher in Piscataway, New Jersey, is fired solely on account of her race. Asian students are denied admission to state universities to make room for students of other races with much weaker records. There are more than 160 federal laws, regulations, and executive orders explicitly requiring race- and sex-based preferences.

Now, as throughout the history of preferences, the key issue in the debate is how policies of preference can be reconciled with the fundamental American tenet that "all men are created equal" and are "endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights."

Evidence of racism can still be found in our country. American society is not yet colorblind. The issue for Americans today is how we can best transcend the divisions of the past. Is it through a policy of consistent nondiscrimination or through a system of preferences?

Racial preferences are frequently justified as a measure to help low-income blacks. But the evidence is compelling that the beneficiaries of preferential policies are overwhelmingly middle-class or wealthy. For the most part, the truly disadvantaged have been unable to participate in the programs that grant preferences. Furthermore, the emphasis on preferences has diverted attention from the task of addressing the root causes of black Americans’ disadvantage. The lagging educational achievement of disadvantaged blacks can be ameliorated not through preferences but through structural reform of the American elementary and secondary education system. Preferences do nothing to help develop the skills necessary for the economic and social advancement of the disadvantaged.

Dressed-Up Discrimination

Preferences must also be judged a moral failure. Although some individuals have benefited significantly from preferences and a case can be made that preferences have enhanced the economic position of the black middle class, these gains have come at a great moral cost. Put simply, preferences discriminate. They deny opportunities to individuals solely because they are members of a nonpreferred race, gender, or ethnic group. The ambitions and aspirations, the hopes and dreams of individual Americans for themselves and for their families are trampled underfoot not for any wrongs those individuals have committed but for the sake of a bureaucratic effort to counterbalance the supposedly pervasive racism of American society. The penalty for the sins of the society at large is imposed on individuals who themselves are guilty only of being born a member of a nonpreferred group. Individual American citizens who would otherwise enjoy jobs and other opportunities are told that they must be denied in order to tilt the scales of racial justice.

Although preferences are presented as a remedial measure, they in fact create a class of innocent victims of government-imposed discrimination. In our system of justice, the burden of a remedy is imposed on those responsible for the specific harm being remedied. In the case of racial preferences, however, this remedial model breaks down. Those who benefit from the remedy need not show that they have in fact suffered any harm, and those who bear the burden of the remedy do so not because of any conduct on their part but purely because of their identity as members of non-preferred groups. Americans of all descriptions are deprived of opportunities under the system of preferences. And some of these victims have themselves struggled to overcome a severely disadvantaged background.

The proponents of preferential policies must acknowledge the injuries done to innocent individuals. They must confront the consequences flowing daily from the system of preferences in awarding contracts, jobs, promotions, and other opportunities. Supporters of the status quo attempt to hide the reality of preferences beneath a facade of "plus factors," "goals and timetables," and other measures that are said merely to "open up access" to opportunities. Behind all these semantic games, individual Americans are denied opportunities by government simply because they are of the wrong color or sex. The names assigned to the policies that deprive them of opportunity are of little moment. What matters is that our government implements a wide range of programs with the purpose of granting favored treatment to some on the basis of their biological characteristics. How can such government-imposed distinctions be reconciled with Martin Luther King’s message that whenever the image of God is recognized as universally present in mankind, " ‘whiteness’ and ‘blackness’ pass away as determinants in a relationship"? The conflict is irreconcilable.

The moral failure of preferences extends beyond the injustice done to individuals who are denied opportunities because they belong to the wrong group. There are other victims of the system of preferences. The supposed beneficiaries are themselves victims.

Preferences attack the dignity of the preferred, and cast a pall of doubt over their competence and worth. Preferences send a message that those in the favored groups are deemed incapable of meeting the standards that others are required to meet. Simply because they are members of a preferred group, individuals are often deprived of the recognition and respect they have earned. The achievements gained through talent and hard work are attributed instead to the operation of the system of preferences. The abilities of the preferred are called into question not only in the eyes of society, but also in the eyes of the preferred themselves. Self-confidence erodes, standards drop, incentives to perform diminish, and pernicious stereotypes are reinforced.

All of this results from treating individuals differently on the basis of race. It is the inevitable consequence of reducing individuals to the status of racial entities. The lesson of our history as Americans is that racial distinctions are inherently cruel. There are no benign distinctions of race. Our history--and perhaps human nature itself--renders that impossible. Although the underlying purpose of preferences was to eliminate the vestiges of racism, the mechanism of redress was fundamentally flawed. Rather than breaking down racial barriers, preferential policies continually remind Americans of racial differences.

Scarring the Soul

Martin Luther King Jr. described the harm done to all Americans by the Jim Crow system: "Segregation scars the soul of both the segregator and the segregated." Similarly, every time our government prefers one individual over another on the basis of race, new scars are created, and the promise of the Declaration of Independence is deferred.

The way forward in American race relations is to embrace the vision of a colorblind legal order that was set forth 100 years ago by Justice Harlan, pursued devotedly by the civil-rights movement, articulated eloquently by President Kennedy, and enshrined in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The way to transcend our racial divisions is to first ensure that we, as a people acting through our government, respect every person as an individual created in the image of God and honor every American as an individual whose color will never be the basis for determining his opportunities.

This principle is consistent with the initial meaning of "affirmative action" in civil-rights law. On March 6, 1961, President Kennedy issued Executive Order 10925, establishing the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity, and creating a framework for "affirmative steps" designed "to realize more fully the national policy of nondiscrimination within the executive branch of the Government." The executive order also provided that government contracts contain the following provision: "The contractor will take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color or national origin."

The original concept of affirmative action excluded any notion of preference. Indeed, the concept of affirmative action was explicitly linked with the principle of nondiscrimination. It was to be affirmative action to ensure that individuals were treated "without regard to their race." There is no hint of group entitlement or proportional representation in the executive order. On the contrary, the exclusive focus is on the right of individuals to be treated as individuals. The "affirmative steps" were actions designed to ensure that individuals of all races would have an opportunity to compete on the basis of their individual merit.

William Van Alstyne, a law professor at Duke University, has stated it as well as anyone: "[O]ne gets beyond racism by getting beyond it now: by a complete, resolute, and credible commitment never to tolerate in one’s own life--or in the life or practices of one’s government--the differential treatment of other human beings by race. Indeed, that is the great lesson for government itself to teach: In all we do in life, whatever we do in life, to treat any person less well than another or to favor any more than another for being black or white or brown or red, is wrong. Let that be our fundamental law and we shall have a Constitution universally worth expounding."

The American people have embraced that commitment, and the courts have gone far toward making it our fundamental law. The only remaining question is whether the elected representatives of the people will do their part to rid our legal order of the odious distinctions of race.

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

14 influential essays from Black writers on America's problems with race

- Business leaders are calling for people to reflect on civil rights this Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

- Black literary experts shared their top nonfiction essay and article picks on race.

- The list includes "A Report from Occupied Territory" by James Baldwin.

For many, Martin Luther King Jr. Day is a time of reflection on the life of one of the nation's most prominent civil rights leaders. It's also an important time for people who support racial justice to educate themselves on the experiences of Black people in America.

Business leaders like TIAA CEO Thasunda Duckett Brown and others are encouraging people to reflect on King's life's work, and one way to do that is to read his essays and the work of others dedicated to the same mission he had: racial equity.

Insider asked Black literary and historical experts to share their favorite works of journalism on race by Black authors. Here are the top pieces they recommended everyone read to better understand the quest for Black liberation in America:

An earlier version of this article was published on June 14, 2020.

"Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases" and "The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States" by Ida B. Wells

In 1892, investigative journalist, activist, and NAACP founding member Ida B. Wells began to publish her research on lynching in a pamphlet titled "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases." Three years later, she followed up with more research and detail in "The Red Record."

Shirley Moody-Turner, associate Professor of English and African American Studies at Penn State University recommended everyone read these two texts, saying they hold "many parallels to our own moment."

"In these two pamphlets, Wells exposes the pervasive use of lynching and white mob violence against African American men and women. She discredits the myths used by white mobs to justify the killing of African Americans and exposes Northern and international audiences to the growing racial violence and terror perpetrated against Black people in the South in the years following the Civil War," Moody-Turner told Business Insider.

Read "Southern Horrors" here and "The Red Record" here >>

"On Juneteenth" by Annette Gordon-Reed

In this collection of essays, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Annette Gordon-Reed combines memoir and history to help readers understand the complexities out of which Juneteenth was born. She also argues how racial and ethnic hierarchies remain in society today, said Moody-Turner.

"Gordon-Reed invites readers to see Juneteenth as a time to grapple with the complexities of race and enslavement in the US, to re-think our origin stories about race and slavery's central role in the formation of both Texas and the US, and to consider how, as Gordon-Reed so eloquently puts it, 'echoes of the past remain, leaving their traces in the people and events of the present and future.'"

Purchase "On Juneteenth" here>>

"The Case for Reparations" by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates, best-selling author and national correspondent for The Atlantic, made waves when he published his 2014 article "The Case for Reparations," in which he called for "collective introspection" on reparations for Black Americans subjected to centuries of racism and violence.

"In his now famed essay for The Atlantic, journalist, author, and essayist, Ta-Nehisi Coates traces how slavery, segregation, and discriminatory racial policies underpin ongoing and systemic economic and racial disparities," Moody-Turner said.

"Coates provides deep historical context punctuated by individual and collective stories that compel us to reconsider the case for reparations," she added.

Read it here>>

"The Idea of America" by Nikole Hannah-Jones and the "1619 Project" by The New York Times

In "The Idea of America," Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones traces America's history from 1619 onward, the year slavery began in the US. She explores how the history of slavery is inseparable from the rise of America's democracy in her essay that's part of The New York Times' larger "1619 Project," which is the outlet's ongoing project created in 2019 to re-examine the impact of slavery in the US.

"In her unflinching look at the legacy of slavery and the underside of American democracy and capitalism, Hannah-Jones asks, 'what if America understood, finally, in this 400th year, that we [Black Americans] have never been the problem but the solution,'" said Moody-Turner, who recommended readers read the whole "1619 Project" as well.

Read "The Idea of America" here and the rest of the "1619 Project here>>

"Many Thousands Gone" by James Baldwin

In "Many Thousands Gone," James Arthur Baldwin, American novelist, playwright, essayist, poet, and activist lays out how white America is not ready to fully recognize Black people as people. It's a must read, according to Jimmy Worthy II, assistant professor of English at The University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

"Baldwin's essay reminds us that in America, the very idea of Black persons conjures an amalgamation of specters, fears, threats, anxieties, guilts, and memories that must be extinguished as part of the labor to forget histories deemed too uncomfortable to remember," Worthy said.

"Letter from a Birmingham Jail" by Martin Luther King Jr.

On April 13 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. and other Civil Rights activists were arrested after peaceful protest in Birmingham, Alabama. In jail, King penned an open letter about how people have a moral obligation to break unjust laws rather than waiting patiently for legal change. In his essay, he expresses criticism and disappointment in white moderates and white churches, something that's not often focused on in history textbooks, Worthy said.

"King revises the perception of white racists devoted to a vehement status quo to include white moderates whose theories of inevitable racial equality and silence pertaining to racial injustice prolong discriminatory practices," Worthy said.

"The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action" by Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde, African American writer, feminist, womanist, librarian, and civil rights activist asks readers to not be silent on important issues. This short, rousing read is crucial for everyone according to Thomonique Moore, a 2016 graduate of Howard University, founder of Books&Shit book club, and an incoming Masters' candidate at Columbia University's Teacher's College.

"In this essay, Lorde explains to readers the importance of overcoming our fears and speaking out about the injustices that are plaguing us and the people around us. She challenges us to not live our lives in silence, or we risk never changing the things around us," Moore said. Read it here>>

"The First White President" by Ta-Nehisi Coates

This essay from the award-winning journalist's book " We Were Eight Years in Power ," details how Trump, during his presidency, employed the notion of whiteness and white supremacy to pick apart the legacy of the nation's first Black president, Barack Obama.

Moore said it was crucial reading to understand the current political environment we're in.

"Just Walk on By" by Brent Staples

In this essay, Brent Staples, author and Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial writer for The New York Times, hones in on the experience of racism against Black people in public spaces, especially on the role of white women in contributing to the view that Black men are threatening figures.

For Crystal M. Fleming, associate professor of sociology and Africana Studies at SUNY Stony Brook, his essay is especially relevant right now.

"We see the relevance of his critique in the recent incident in New York City, wherein a white woman named Amy Cooper infamously called the police and lied, claiming that a Black man — Christian Cooper — threatened her life in Central Park. Although the experience that Staples describes took place decades ago, the social dynamics have largely remained the same," Fleming told Insider.

"I Was Pregnant and in Crisis. All the Doctors and Nurses Saw Was an Incompetent Black Woman" by Tressie McMillan Cottom

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an author, associate professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University and a faculty affiliate at Harvard University's Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. In this essay, Cottom shares her gut-wrenching experience of racism within the healthcare system.

Fleming called this piece an "excellent primer on intersectionality" between racism and sexism, calling Cottom one of the most influential sociologists and writers in the US today. Read it here>>

"A Report from Occupied Territory" by James Baldwin

Baldwin's "A Report from Occupied Territory" was originally published in The Nation in 1966. It takes a hard look at violence against Black people in the US, specifically police brutality.

"Baldwin's work remains essential to understanding the depth and breadth of anti-black racism in our society. This essay — which touches on issues of racialized violence, policing and the role of the law in reproducing inequality — is an absolute must-read for anyone who wants to understand just how much has not changed with regard to police violence and anti-Black racism in our country," Fleming told Insider. Read it here>>

"I'm From Philly. 30 Years Later, I'm Still Trying To Make Sense Of The MOVE Bombing" by Gene Demby

On May 13, 1985, a police helicopter dropped a bomb on the MOVE compound in Philadelphia, which housed members of the MOVE, a black liberation group founded in 1972 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Eleven people, including five children, died in the airstrike. In this essay, Gene Demby, co-host and correspondent for NPR's Code Switch team, tries to wrap his head around the shocking instance of police violence against Black people.

"I would argue that the fact that police were authorized to literally bomb Black citizens in their own homes, in their own country, is directly relevant to current conversations about militarized police and the growing movement to defund and abolish policing," Fleming said. Read it here>>

When you buy through our links, Insider may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more .

- Main content

- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

Breaking Through Barriers to Racial Equity

In this SSIR series, made possible with a grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, we sought to shake up contemporary discussions around diversity, equity, and inclusion, commonly referred to as its decorous, innocuous acronym, “DEI.”

The collection of 10 essays—by fresh new voices to SSIR —were selected from more than five dozen entries on the theme of analyzing DEI work through a global intersectional race lens.