Survey vs. Research — What's the Difference?

Difference Between Survey and Research

Table of contents, key differences, comparison chart, compare with definitions, common curiosities, is research always based on surveys, what is the main goal of conducting a survey, can the results of a survey be used in research, how does research contribute to knowledge, can a survey be considered research, what makes research different from mere data collection, how important is methodology in research, can research be conducted without a survey, can a single survey answer complex research questions, what ethical considerations are important in surveys and research, is participant selection important in surveys and research, how do the outcomes of surveys and research differ, how is research validated, what role do surveys play in market research, can the findings from a survey be challenged, share your discovery.

Author Spotlight

Popular Comparisons

Trending Comparisons

New Comparisons

Trending Terms

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Adv Pract Oncol

- v.6(2); Mar-Apr 2015

Understanding and Evaluating Survey Research

A variety of methodologic approaches exist for individuals interested in conducting research. Selection of a research approach depends on a number of factors, including the purpose of the research, the type of research questions to be answered, and the availability of resources. The purpose of this article is to describe survey research as one approach to the conduct of research so that the reader can critically evaluate the appropriateness of the conclusions from studies employing survey research.

SURVEY RESEARCH

Survey research is defined as "the collection of information from a sample of individuals through their responses to questions" ( Check & Schutt, 2012, p. 160 ). This type of research allows for a variety of methods to recruit participants, collect data, and utilize various methods of instrumentation. Survey research can use quantitative research strategies (e.g., using questionnaires with numerically rated items), qualitative research strategies (e.g., using open-ended questions), or both strategies (i.e., mixed methods). As it is often used to describe and explore human behavior, surveys are therefore frequently used in social and psychological research ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ).

Information has been obtained from individuals and groups through the use of survey research for decades. It can range from asking a few targeted questions of individuals on a street corner to obtain information related to behaviors and preferences, to a more rigorous study using multiple valid and reliable instruments. Common examples of less rigorous surveys include marketing or political surveys of consumer patterns and public opinion polls.

Survey research has historically included large population-based data collection. The primary purpose of this type of survey research was to obtain information describing characteristics of a large sample of individuals of interest relatively quickly. Large census surveys obtaining information reflecting demographic and personal characteristics and consumer feedback surveys are prime examples. These surveys were often provided through the mail and were intended to describe demographic characteristics of individuals or obtain opinions on which to base programs or products for a population or group.

More recently, survey research has developed into a rigorous approach to research, with scientifically tested strategies detailing who to include (representative sample), what and how to distribute (survey method), and when to initiate the survey and follow up with nonresponders (reducing nonresponse error), in order to ensure a high-quality research process and outcome. Currently, the term "survey" can reflect a range of research aims, sampling and recruitment strategies, data collection instruments, and methods of survey administration.

Given this range of options in the conduct of survey research, it is imperative for the consumer/reader of survey research to understand the potential for bias in survey research as well as the tested techniques for reducing bias, in order to draw appropriate conclusions about the information reported in this manner. Common types of error in research, along with the sources of error and strategies for reducing error as described throughout this article, are summarized in the Table .

Sources of Error in Survey Research and Strategies to Reduce Error

The goal of sampling strategies in survey research is to obtain a sufficient sample that is representative of the population of interest. It is often not feasible to collect data from an entire population of interest (e.g., all individuals with lung cancer); therefore, a subset of the population or sample is used to estimate the population responses (e.g., individuals with lung cancer currently receiving treatment). A large random sample increases the likelihood that the responses from the sample will accurately reflect the entire population. In order to accurately draw conclusions about the population, the sample must include individuals with characteristics similar to the population.

It is therefore necessary to correctly identify the population of interest (e.g., individuals with lung cancer currently receiving treatment vs. all individuals with lung cancer). The sample will ideally include individuals who reflect the intended population in terms of all characteristics of the population (e.g., sex, socioeconomic characteristics, symptom experience) and contain a similar distribution of individuals with those characteristics. As discussed by Mady Stovall beginning on page 162, Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ), for example, were interested in the population of oncologists. The authors obtained a sample of oncologists from two hospitals in Japan. These participants may or may not have similar characteristics to all oncologists in Japan.

Participant recruitment strategies can affect the adequacy and representativeness of the sample obtained. Using diverse recruitment strategies can help improve the size of the sample and help ensure adequate coverage of the intended population. For example, if a survey researcher intends to obtain a sample of individuals with breast cancer representative of all individuals with breast cancer in the United States, the researcher would want to use recruitment strategies that would recruit both women and men, individuals from rural and urban settings, individuals receiving and not receiving active treatment, and so on. Because of the difficulty in obtaining samples representative of a large population, researchers may focus the population of interest to a subset of individuals (e.g., women with stage III or IV breast cancer). Large census surveys require extremely large samples to adequately represent the characteristics of the population because they are intended to represent the entire population.

DATA COLLECTION METHODS

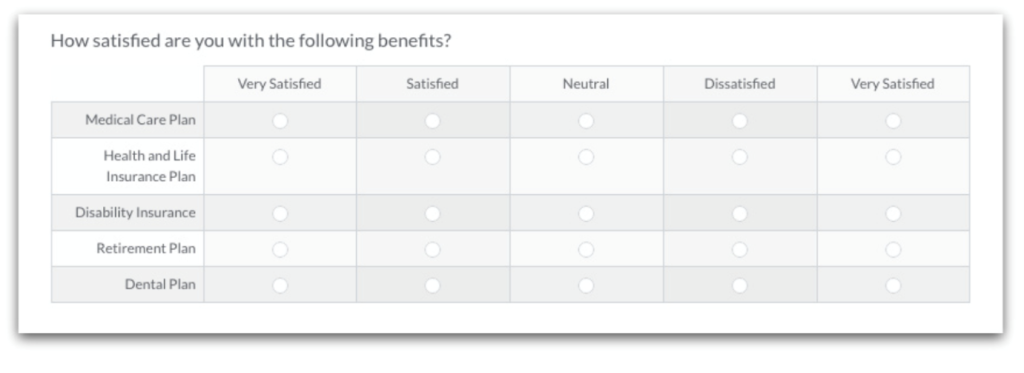

Survey research may use a variety of data collection methods with the most common being questionnaires and interviews. Questionnaires may be self-administered or administered by a professional, may be administered individually or in a group, and typically include a series of items reflecting the research aims. Questionnaires may include demographic questions in addition to valid and reliable research instruments ( Costanzo, Stawski, Ryff, Coe, & Almeida, 2012 ; DuBenske et al., 2014 ; Ponto, Ellington, Mellon, & Beck, 2010 ). It is helpful to the reader when authors describe the contents of the survey questionnaire so that the reader can interpret and evaluate the potential for errors of validity (e.g., items or instruments that do not measure what they are intended to measure) and reliability (e.g., items or instruments that do not measure a construct consistently). Helpful examples of articles that describe the survey instruments exist in the literature ( Buerhaus et al., 2012 ).

Questionnaires may be in paper form and mailed to participants, delivered in an electronic format via email or an Internet-based program such as SurveyMonkey, or a combination of both, giving the participant the option to choose which method is preferred ( Ponto et al., 2010 ). Using a combination of methods of survey administration can help to ensure better sample coverage (i.e., all individuals in the population having a chance of inclusion in the sample) therefore reducing coverage error ( Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014 ; Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). For example, if a researcher were to only use an Internet-delivered questionnaire, individuals without access to a computer would be excluded from participation. Self-administered mailed, group, or Internet-based questionnaires are relatively low cost and practical for a large sample ( Check & Schutt, 2012 ).

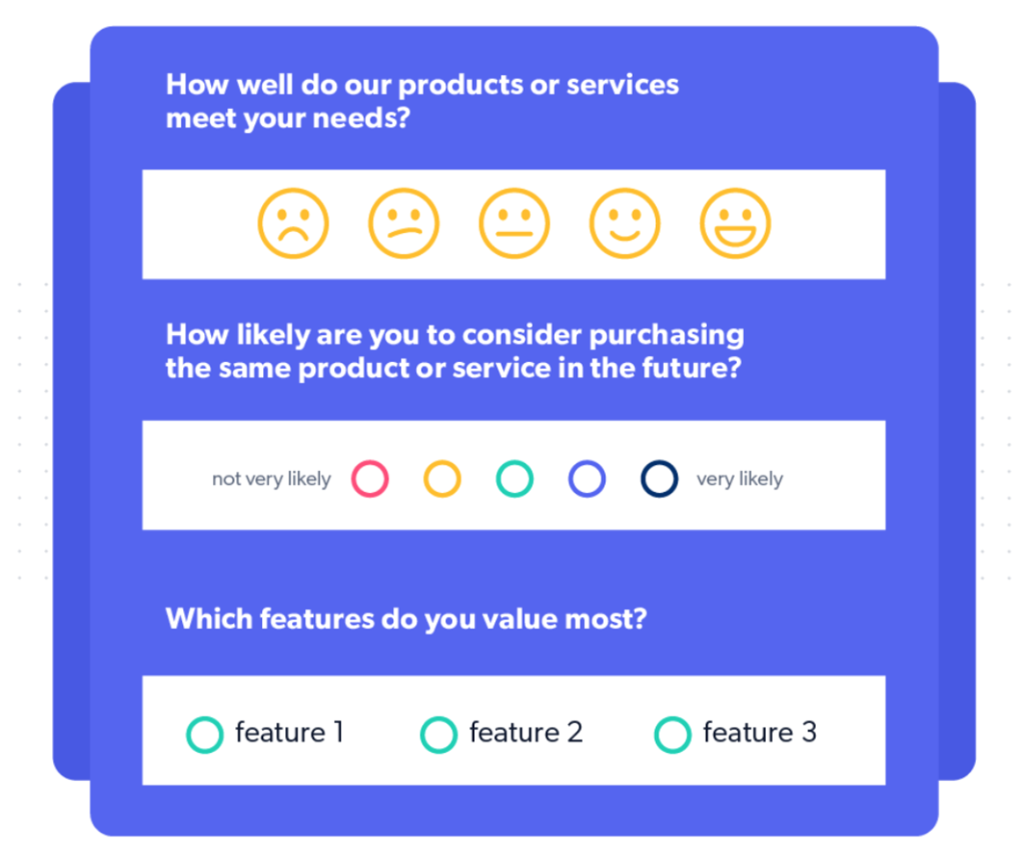

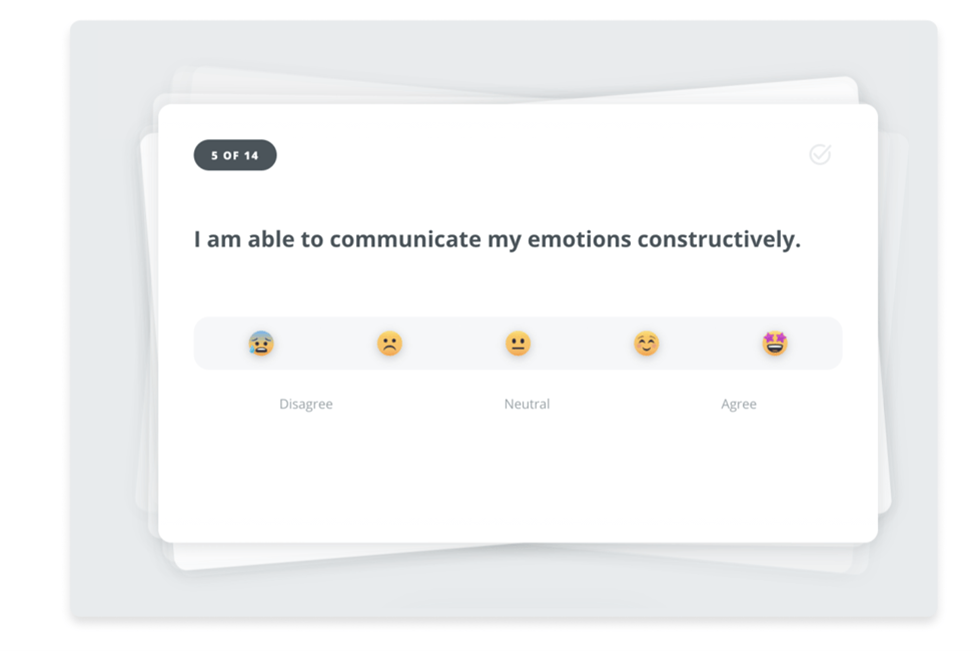

Dillman et al. ( 2014 ) have described and tested a tailored design method for survey research. Improving the visual appeal and graphics of surveys by using a font size appropriate for the respondents, ordering items logically without creating unintended response bias, and arranging items clearly on each page can increase the response rate to electronic questionnaires. Attending to these and other issues in electronic questionnaires can help reduce measurement error (i.e., lack of validity or reliability) and help ensure a better response rate.

Conducting interviews is another approach to data collection used in survey research. Interviews may be conducted by phone, computer, or in person and have the benefit of visually identifying the nonverbal response(s) of the interviewee and subsequently being able to clarify the intended question. An interviewer can use probing comments to obtain more information about a question or topic and can request clarification of an unclear response ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). Interviews can be costly and time intensive, and therefore are relatively impractical for large samples.

Some authors advocate for using mixed methods for survey research when no one method is adequate to address the planned research aims, to reduce the potential for measurement and non-response error, and to better tailor the study methods to the intended sample ( Dillman et al., 2014 ; Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). For example, a mixed methods survey research approach may begin with distributing a questionnaire and following up with telephone interviews to clarify unclear survey responses ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). Mixed methods might also be used when visual or auditory deficits preclude an individual from completing a questionnaire or participating in an interview.

FUJIMORI ET AL.: SURVEY RESEARCH

Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ) described the use of survey research in a study of the effect of communication skills training for oncologists on oncologist and patient outcomes (e.g., oncologist’s performance and confidence and patient’s distress, satisfaction, and trust). A sample of 30 oncologists from two hospitals was obtained and though the authors provided a power analysis concluding an adequate number of oncologist participants to detect differences between baseline and follow-up scores, the conclusions of the study may not be generalizable to a broader population of oncologists. Oncologists were randomized to either an intervention group (i.e., communication skills training) or a control group (i.e., no training).

Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ) chose a quantitative approach to collect data from oncologist and patient participants regarding the study outcome variables. Self-report numeric ratings were used to measure oncologist confidence and patient distress, satisfaction, and trust. Oncologist confidence was measured using two instruments each using 10-point Likert rating scales. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure patient distress and has demonstrated validity and reliability in a number of populations including individuals with cancer ( Bjelland, Dahl, Haug, & Neckelmann, 2002 ). Patient satisfaction and trust were measured using 0 to 10 numeric rating scales. Numeric observer ratings were used to measure oncologist performance of communication skills based on a videotaped interaction with a standardized patient. Participants completed the same questionnaires at baseline and follow-up.

The authors clearly describe what data were collected from all participants. Providing additional information about the manner in which questionnaires were distributed (i.e., electronic, mail), the setting in which data were collected (e.g., home, clinic), and the design of the survey instruments (e.g., visual appeal, format, content, arrangement of items) would assist the reader in drawing conclusions about the potential for measurement and nonresponse error. The authors describe conducting a follow-up phone call or mail inquiry for nonresponders, using the Dillman et al. ( 2014 ) tailored design for survey research follow-up may have reduced nonresponse error.

CONCLUSIONS

Survey research is a useful and legitimate approach to research that has clear benefits in helping to describe and explore variables and constructs of interest. Survey research, like all research, has the potential for a variety of sources of error, but several strategies exist to reduce the potential for error. Advanced practitioners aware of the potential sources of error and strategies to improve survey research can better determine how and whether the conclusions from a survey research study apply to practice.

The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Survey Research: Definition, Examples and Methods

Survey Research is a quantitative research method used for collecting data from a set of respondents. It has been perhaps one of the most used methodologies in the industry for several years due to the multiple benefits and advantages that it has when collecting and analyzing data.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

In this article, you will learn everything about survey research, such as types, methods, and examples.

Survey Research Definition

Survey Research is defined as the process of conducting research using surveys that researchers send to survey respondents. The data collected from surveys is then statistically analyzed to draw meaningful research conclusions. In the 21st century, every organization’s eager to understand what their customers think about their products or services and make better business decisions. Researchers can conduct research in multiple ways, but surveys are proven to be one of the most effective and trustworthy research methods. An online survey is a method for extracting information about a significant business matter from an individual or a group of individuals. It consists of structured survey questions that motivate the participants to respond. Creditable survey research can give these businesses access to a vast information bank. Organizations in media, other companies, and even governments rely on survey research to obtain accurate data.

The traditional definition of survey research is a quantitative method for collecting information from a pool of respondents by asking multiple survey questions. This research type includes the recruitment of individuals collection, and analysis of data. It’s useful for researchers who aim to communicate new features or trends to their respondents.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis Generally, it’s the primary step towards obtaining quick information about mainstream topics and conducting more rigorous and detailed quantitative research methods like surveys/polls or qualitative research methods like focus groups/on-call interviews can follow. There are many situations where researchers can conduct research using a blend of both qualitative and quantitative strategies.

LEARN ABOUT: Survey Sampling

Survey Research Methods

Survey research methods can be derived based on two critical factors: Survey research tool and time involved in conducting research. There are three main survey research methods, divided based on the medium of conducting survey research:

- Online/ Email: Online survey research is one of the most popular survey research methods today. The survey cost involved in online survey research is extremely minimal, and the responses gathered are highly accurate.

- Phone: Survey research conducted over the telephone ( CATI survey ) can be useful in collecting data from a more extensive section of the target population. There are chances that the money invested in phone surveys will be higher than other mediums, and the time required will be higher.

- Face-to-face: Researchers conduct face-to-face in-depth interviews in situations where there is a complicated problem to solve. The response rate for this method is the highest, but it can be costly.

Further, based on the time taken, survey research can be classified into two methods:

- Longitudinal survey research: Longitudinal survey research involves conducting survey research over a continuum of time and spread across years and decades. The data collected using this survey research method from one time period to another is qualitative or quantitative. Respondent behavior, preferences, and attitudes are continuously observed over time to analyze reasons for a change in behavior or preferences. For example, suppose a researcher intends to learn about the eating habits of teenagers. In that case, he/she will follow a sample of teenagers over a considerable period to ensure that the collected information is reliable. Often, cross-sectional survey research follows a longitudinal study .

- Cross-sectional survey research: Researchers conduct a cross-sectional survey to collect insights from a target audience at a particular time interval. This survey research method is implemented in various sectors such as retail, education, healthcare, SME businesses, etc. Cross-sectional studies can either be descriptive or analytical. It is quick and helps researchers collect information in a brief period. Researchers rely on the cross-sectional survey research method in situations where descriptive analysis of a subject is required.

Survey research also is bifurcated according to the sampling methods used to form samples for research: Probability and Non-probability sampling. Every individual in a population should be considered equally to be a part of the survey research sample. Probability sampling is a sampling method in which the researcher chooses the elements based on probability theory. The are various probability research methods, such as simple random sampling , systematic sampling, cluster sampling, stratified random sampling, etc. Non-probability sampling is a sampling method where the researcher uses his/her knowledge and experience to form samples.

LEARN ABOUT: Survey Sample Sizes

The various non-probability sampling techniques are :

- Convenience sampling

- Snowball sampling

- Consecutive sampling

- Judgemental sampling

- Quota sampling

Process of implementing survey research methods:

- Decide survey questions: Brainstorm and put together valid survey questions that are grammatically and logically appropriate. Understanding the objective and expected outcomes of the survey helps a lot. There are many surveys where details of responses are not as important as gaining insights about what customers prefer from the provided options. In such situations, a researcher can include multiple-choice questions or closed-ended questions . Whereas, if researchers need to obtain details about specific issues, they can consist of open-ended questions in the questionnaire. Ideally, the surveys should include a smart balance of open-ended and closed-ended questions. Use survey questions like Likert Scale , Semantic Scale, Net Promoter Score question, etc., to avoid fence-sitting.

LEARN ABOUT: System Usability Scale

- Finalize a target audience: Send out relevant surveys as per the target audience and filter out irrelevant questions as per the requirement. The survey research will be instrumental in case the target population decides on a sample. This way, results can be according to the desired market and be generalized to the entire population.

LEARN ABOUT: Testimonial Questions

- Send out surveys via decided mediums: Distribute the surveys to the target audience and patiently wait for the feedback and comments- this is the most crucial step of the survey research. The survey needs to be scheduled, keeping in mind the nature of the target audience and its regions. Surveys can be conducted via email, embedded in a website, shared via social media, etc., to gain maximum responses.

- Analyze survey results: Analyze the feedback in real-time and identify patterns in the responses which might lead to a much-needed breakthrough for your organization. GAP, TURF Analysis , Conjoint analysis, Cross tabulation, and many such survey feedback analysis methods can be used to spot and shed light on respondent behavior. Researchers can use the results to implement corrective measures to improve customer/employee satisfaction.

Reasons to conduct survey research

The most crucial and integral reason for conducting market research using surveys is that you can collect answers regarding specific, essential questions. You can ask these questions in multiple survey formats as per the target audience and the intent of the survey. Before designing a study, every organization must figure out the objective of carrying this out so that the study can be structured, planned, and executed to perfection.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

Questions that need to be on your mind while designing a survey are:

- What is the primary aim of conducting the survey?

- How do you plan to utilize the collected survey data?

- What type of decisions do you plan to take based on the points mentioned above?

There are three critical reasons why an organization must conduct survey research.

- Understand respondent behavior to get solutions to your queries: If you’ve carefully curated a survey, the respondents will provide insights about what they like about your organization as well as suggestions for improvement. To motivate them to respond, you must be very vocal about how secure their responses will be and how you will utilize the answers. This will push them to be 100% honest about their feedback, opinions, and comments. Online surveys or mobile surveys have proved their privacy, and due to this, more and more respondents feel free to put forth their feedback through these mediums.

- Present a medium for discussion: A survey can be the perfect platform for respondents to provide criticism or applause for an organization. Important topics like product quality or quality of customer service etc., can be put on the table for discussion. A way you can do it is by including open-ended questions where the respondents can write their thoughts. This will make it easy for you to correlate your survey to what you intend to do with your product or service.

- Strategy for never-ending improvements: An organization can establish the target audience’s attributes from the pilot phase of survey research . Researchers can use the criticism and feedback received from this survey to improve the product/services. Once the company successfully makes the improvements, it can send out another survey to measure the change in feedback keeping the pilot phase the benchmark. By doing this activity, the organization can track what was effectively improved and what still needs improvement.

Survey Research Scales

There are four main scales for the measurement of variables:

- Nominal Scale: A nominal scale associates numbers with variables for mere naming or labeling, and the numbers usually have no other relevance. It is the most basic of the four levels of measurement.

- Ordinal Scale: The ordinal scale has an innate order within the variables along with labels. It establishes the rank between the variables of a scale but not the difference value between the variables.

- Interval Scale: The interval scale is a step ahead in comparison to the other two scales. Along with establishing a rank and name of variables, the scale also makes known the difference between the two variables. The only drawback is that there is no fixed start point of the scale, i.e., the actual zero value is absent.

- Ratio Scale: The ratio scale is the most advanced measurement scale, which has variables that are labeled in order and have a calculated difference between variables. In addition to what interval scale orders, this scale has a fixed starting point, i.e., the actual zero value is present.

Benefits of survey research

In case survey research is used for all the right purposes and is implemented properly, marketers can benefit by gaining useful, trustworthy data that they can use to better the ROI of the organization.

Other benefits of survey research are:

- Minimum investment: Mobile surveys and online surveys have minimal finance invested per respondent. Even with the gifts and other incentives provided to the people who participate in the study, online surveys are extremely economical compared to paper-based surveys.

- Versatile sources for response collection: You can conduct surveys via various mediums like online and mobile surveys. You can further classify them into qualitative mediums like focus groups , and interviews and quantitative mediums like customer-centric surveys. Due to the offline survey response collection option, researchers can conduct surveys in remote areas with limited internet connectivity. This can make data collection and analysis more convenient and extensive.

- Reliable for respondents: Surveys are extremely secure as the respondent details and responses are kept safeguarded. This anonymity makes respondents answer the survey questions candidly and with absolute honesty. An organization seeking to receive explicit responses for its survey research must mention that it will be confidential.

Survey research design

Researchers implement a survey research design in cases where there is a limited cost involved and there is a need to access details easily. This method is often used by small and large organizations to understand and analyze new trends, market demands, and opinions. Collecting information through tactfully designed survey research can be much more effective and productive than a casually conducted survey.

There are five stages of survey research design:

- Decide an aim of the research: There can be multiple reasons for a researcher to conduct a survey, but they need to decide a purpose for the research. This is the primary stage of survey research as it can mold the entire path of a survey, impacting its results.

- Filter the sample from target population: Who to target? is an essential question that a researcher should answer and keep in mind while conducting research. The precision of the results is driven by who the members of a sample are and how useful their opinions are. The quality of respondents in a sample is essential for the results received for research and not the quantity. If a researcher seeks to understand whether a product feature will work well with their target market, he/she can conduct survey research with a group of market experts for that product or technology.

- Zero-in on a survey method: Many qualitative and quantitative research methods can be discussed and decided. Focus groups, online interviews, surveys, polls, questionnaires, etc. can be carried out with a pre-decided sample of individuals.

- Design the questionnaire: What will the content of the survey be? A researcher is required to answer this question to be able to design it effectively. What will the content of the cover letter be? Or what are the survey questions of this questionnaire? Understand the target market thoroughly to create a questionnaire that targets a sample to gain insights about a survey research topic.

- Send out surveys and analyze results: Once the researcher decides on which questions to include in a study, they can send it across to the selected sample . Answers obtained from this survey can be analyzed to make product-related or marketing-related decisions.

Survey examples: 10 tips to design the perfect research survey

Picking the right survey design can be the key to gaining the information you need to make crucial decisions for all your research. It is essential to choose the right topic, choose the right question types, and pick a corresponding design. If this is your first time creating a survey, it can seem like an intimidating task. But with QuestionPro, each step of the process is made simple and easy.

Below are 10 Tips To Design The Perfect Research Survey:

- Set your SMART goals: Before conducting any market research or creating a particular plan, set your SMART Goals . What is that you want to achieve with the survey? How will you measure it promptly, and what are the results you are expecting?

- Choose the right questions: Designing a survey can be a tricky task. Asking the right questions may help you get the answers you are looking for and ease the task of analyzing. So, always choose those specific questions – relevant to your research.

- Begin your survey with a generalized question: Preferably, start your survey with a general question to understand whether the respondent uses the product or not. That also provides an excellent base and intro for your survey.

- Enhance your survey: Choose the best, most relevant, 15-20 questions. Frame each question as a different question type based on the kind of answer you would like to gather from each. Create a survey using different types of questions such as multiple-choice, rating scale, open-ended, etc. Look at more survey examples and four measurement scales every researcher should remember.

- Prepare yes/no questions: You may also want to use yes/no questions to separate people or branch them into groups of those who “have purchased” and those who “have not yet purchased” your products or services. Once you separate them, you can ask them different questions.

- Test all electronic devices: It becomes effortless to distribute your surveys if respondents can answer them on different electronic devices like mobiles, tablets, etc. Once you have created your survey, it’s time to TEST. You can also make any corrections if needed at this stage.

- Distribute your survey: Once your survey is ready, it is time to share and distribute it to the right audience. You can share handouts and share them via email, social media, and other industry-related offline/online communities.

- Collect and analyze responses: After distributing your survey, it is time to gather all responses. Make sure you store your results in a particular document or an Excel sheet with all the necessary categories mentioned so that you don’t lose your data. Remember, this is the most crucial stage. Segregate your responses based on demographics, psychographics, and behavior. This is because, as a researcher, you must know where your responses are coming from. It will help you to analyze, predict decisions, and help write the summary report.

- Prepare your summary report: Now is the time to share your analysis. At this stage, you should mention all the responses gathered from a survey in a fixed format. Also, the reader/customer must get clarity about your goal, which you were trying to gain from the study. Questions such as – whether the product or service has been used/preferred or not. Do respondents prefer some other product to another? Any recommendations?

Having a tool that helps you carry out all the necessary steps to carry out this type of study is a vital part of any project. At QuestionPro, we have helped more than 10,000 clients around the world to carry out data collection in a simple and effective way, in addition to offering a wide range of solutions to take advantage of this data in the best possible way.

From dashboards, advanced analysis tools, automation, and dedicated functions, in QuestionPro, you will find everything you need to execute your research projects effectively. Uncover insights that matter the most!

MORE LIKE THIS

Government Customer Experience: Impact on Government Service

Apr 11, 2024

Employee Engagement App: Top 11 For Workforce Improvement

Apr 10, 2024

Top 15 Employee Evaluation Software to Enhance Performance

Event Feedback Software: Top 11 Best in 2024

Apr 9, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

A Comprehensive Guide to Survey Research Methodologies

For decades, researchers and businesses have used survey research to produce statistical data and explore ideas. The survey process is simple, ask questions and analyze the responses to make decisions. Data is what makes the difference between a valid and invalid statement and as the American statistician, W. Edwards Deming said:

“Without data, you’re just another person with an opinion.” - W. Edwards Deming

In this article, we will discuss what survey research is, its brief history, types, common uses, benefits, and the step-by-step process of designing a survey.

What is Survey Research

A survey is a research method that is used to collect data from a group of respondents in order to gain insights and information regarding a particular subject. It’s an excellent method to gather opinions and understand how and why people feel a certain way about different situations and contexts.

Brief History of Survey Research

Survey research may have its roots in the American and English “social surveys” conducted around the turn of the 20th century. The surveys were mainly conducted by researchers and reformers to document the extent of social issues such as poverty. ( 1 ) Despite being a relatively young field to many scientific domains, survey research has experienced three stages of development ( 2 ):

- First Era (1930-1960)

- Second Era (1960-1990)

- Third Era (1990 onwards)

Over the years, survey research adapted to the changing times and technologies. By exploiting the latest technologies, researchers can gain access to the right population from anywhere in the world, analyze the data like never before, and extract useful information.

Survey Research Methods & Types

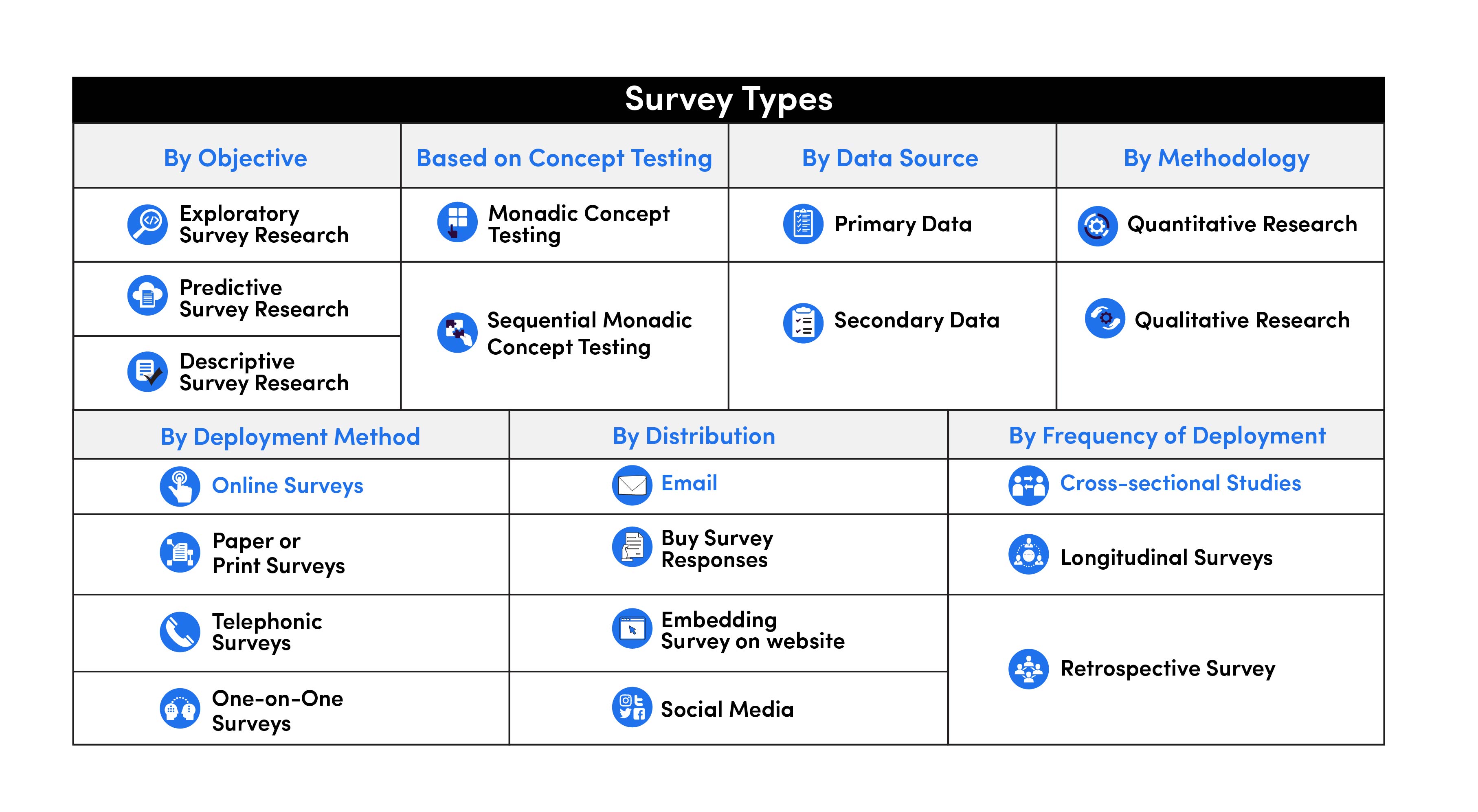

Survey research can be classified into seven categories based on objective, data sources, methodology, deployment method, and frequency of deployment.

Surveys based on Objective

Exploratory survey research.

Exploratory survey research is aimed at diving deeper into research subjects and finding out more about their context. It’s important for marketing or business strategy and the focus is to discover ideas and insights instead of gathering statistical data.

Generally, exploratory survey research is composed of open-ended questions that allow respondents to express their thoughts and perspectives. The final responses present information from various sources that can lead to fresh initiatives.

Predictive Survey Research

Predictive survey research is also called causal survey research. It’s preplanned, structured, and quantitative in nature. It’s often referred to as conclusive research as it tries to explain the cause-and-effect relationship between different variables. The objective is to understand which variables are causes and which are effects and the nature of the relationship between both variables.

Descriptive Survey Research

Descriptive survey research is largely observational and is ideal for gathering numeric data. Due to its quantitative nature, it’s often compared to exploratory survey research. The difference between the two is that descriptive research is structured and pre-planned.

The idea behind descriptive research is to describe the mindset and opinion of a particular group of people on a given subject. The questions are every day multiple choices and users must choose from predefined categories. With predefined choices, you don’t get unique insights, rather, statistically inferable data.

Survey Research Types based on Concept Testing

Monadic concept testing.

Monadic testing is a survey research methodology in which the respondents are split into multiple groups and ask each group questions about a separate concept in isolation. Generally, monadic surveys are hyper-focused on a particular concept and shorter in duration. The important thing in monadic surveys is to avoid getting off-topic or exhausting the respondents with too many questions.

Sequential Monadic Concept Testing

Another approach to monadic testing is sequential monadic testing. In sequential monadic surveys, groups of respondents are surveyed in isolation. However, instead of surveying three groups on three different concepts, the researchers survey the same groups of people on three distinct concepts one after another. In a sequential monadic survey, at least two topics are included (in random order), and the same questions are asked for each concept to eliminate bias.

Based on Data Source

Primary data.

Data obtained directly from the source or target population is referred to as primary survey data. When it comes to primary data collection, researchers usually devise a set of questions and invite people with knowledge of the subject to respond. The main sources of primary data are interviews, questionnaires, surveys, and observation methods.

Compared to secondary data, primary data is gathered from first-hand sources and is more reliable. However, the process of primary data collection is both costly and time-consuming.

Secondary Data

Survey research is generally used to collect first-hand information from a respondent. However, surveys can also be designed to collect and process secondary data. It’s collected from third-party sources or primary sources in the past.

This type of data is usually generic, readily available, and cheaper than primary data collection. Some common sources of secondary data are books, data collected from older surveys, online data, and data from government archives. Beware that you might compromise the validity of your findings if you end up with irrelevant or inflated data.

Based on Research Method

Quantitative research.

Quantitative research is a popular research methodology that is used to collect numeric data in a systematic investigation. It’s frequently used in research contexts where statistical data is required, such as sciences or social sciences. Quantitative research methods include polls, systematic observations, and face-to-face interviews.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a research methodology where you collect non-numeric data from research participants. In this context, the participants are not restricted to a specific system and provide open-ended information. Some common qualitative research methods include focus groups, one-on-one interviews, observations, and case studies.

Based on Deployment Method

Online surveys.

With technology advancing rapidly, the most popular method of survey research is an online survey. With the internet, you can not only reach a broader audience but also design and customize a survey and deploy it from anywhere. Online surveys have outperformed offline survey methods as they are less expensive and allow researchers to easily collect and analyze data from a large sample.

Paper or Print Surveys

As the name suggests, paper or print surveys use the traditional paper and pencil approach to collect data. Before the invention of computers, paper surveys were the survey method of choice.

Though many would assume that surveys are no longer conducted on paper, it's still a reliable method of collecting information during field research and data collection. However, unlike online surveys, paper surveys are expensive and require extra human resources.

Telephonic Surveys

Telephonic surveys are conducted over telephones where a researcher asks a series of questions to the respondent on the other end. Contacting respondents over a telephone requires less effort, human resources, and is less expensive.

What makes telephonic surveys debatable is that people are often reluctant in giving information over a phone call. Additionally, the success of such surveys depends largely on whether people are willing to invest their time on a phone call answering questions.

One-on-one Surveys

One-on-one surveys also known as face-to-face surveys are interviews where the researcher and respondent. Interacting directly with the respondent introduces the human factor into the survey.

Face-to-face interviews are useful when the researcher wants to discuss something personal with the respondent. The response rates in such surveys are always higher as the interview is being conducted in person. However, these surveys are quite expensive and the success of these depends on the knowledge and experience of the researcher.

Based on Distribution

The easiest and most common way of conducting online surveys is sending out an email. Sending out surveys via emails has a higher response rate as your target audience already knows about your brand and is likely to engage.

Buy Survey Responses

Purchasing survey responses also yields higher responses as the responders signed up for the survey. Businesses often purchase survey samples to conduct extensive research. Here, the target audience is often pre-screened to check if they're qualified to take part in the research.

Embedding Survey on a Website

Embedding surveys on a website is another excellent way to collect information. It allows your website visitors to take part in a survey without ever leaving the website and can be done while a person is entering or exiting the website.

Post the Survey on Social Media

Social media is an excellent medium to reach abroad range of audiences. You can publish your survey as a link on social media and people who are following the brand can take part and answer questions.

Based on Frequency of Deployment

Cross-sectional studies.

Cross-sectional studies are administered to a small sample from a large population within a short period of time. This provides researchers a peek into what the respondents are thinking at a given time. The surveys are usually short, precise, and specific to a particular situation.

Longitudinal Surveys

Longitudinal surveys are an extension of cross-sectional studies where researchers make an observation and collect data over extended periods of time. This type of survey can be further divided into three types:

- Trend surveys are employed to allow researchers to understand the change in the thought process of the respondents over some time.

- Panel surveys are administered to the same group of people over multiple years. These are usually expensive and researchers must stick to their panel to gather unbiased opinions.

- In cohort surveys, researchers identify a specific category of people and regularly survey them. Unlike panel surveys, the same people do not need to take part over the years, but each individual must fall into the researcher’s primary interest category.

Retrospective Survey

Retrospective surveys allow researchers to ask questions to gather data about past events and beliefs of the respondents. Since retrospective surveys also require years of data, they are similar to the longitudinal survey, except retrospective surveys are shorter and less expensive.

Why Should You Conduct Research Surveys?

“In God we trust. All others must bring data” - W. Edwards Deming

In the information age, survey research is of utmost importance and essential for understanding the opinion of your target population. Whether you’re launching a new product or conducting a social survey, the tool can be used to collect specific information from a defined set of respondents. The data collected via surveys can be further used by organizations to make informed decisions.

Furthermore, compared to other research methods, surveys are relatively inexpensive even if you’re giving out incentives. Compared to the older methods such as telephonic or paper surveys, online surveys have a smaller cost and the number of responses is higher.

What makes surveys useful is that they describe the characteristics of a large population. With a larger sample size , you can rely on getting more accurate results. However, you also need honest and open answers for accurate results. Since surveys are also anonymous and the responses remain confidential, respondents provide candid and accurate answers.

Common Uses of a Survey

Surveys are widely used in many sectors, but the most common uses of the survey research include:

- Market research : surveying a potential market to understand customer needs, preferences, and market demand.

- Customer Satisfaction: finding out your customer’s opinions about your services, products, or companies .

- Social research: investigating the characteristics and experiences of various social groups.

- Health research: collecting data about patients’ symptoms and treatments.

- Politics: evaluating public opinion regarding policies and political parties.

- Psychology: exploring personality traits, behaviors, and preferences.

6 Steps to Conduct Survey Research

An organization, person, or company conducts a survey when they need the information to make a decision but have insufficient data on hand. Following are six simple steps that can help you design a great survey.

Step 1: Objective of the Survey

The first step in survey research is defining an objective. The objective helps you define your target population and samples. The target population is the specific group of people you want to collect data from and since it’s rarely possible to survey the entire population, we target a specific sample from it. Defining a survey objective also benefits your respondents by helping them understand the reason behind the survey.

Step 2: Number of Questions

The number of questions or the size of the survey depends on the survey objective. However, it’s important to ensure that there are no redundant queries and the questions are in a logical order. Rephrased and repeated questions in a survey are almost as frustrating as in real life. For a higher completion rate, keep the questionnaire small so that the respondents stay engaged to the very end. The ideal length of an interview is less than 15 minutes. ( 2 )

Step 3: Language and Voice of Questions

While designing a survey, you may feel compelled to use fancy language. However, remember that difficult language is associated with higher survey dropout rates. You need to speak to the respondent in a clear, concise, and neutral manner, and ask simple questions. If your survey respondents are bilingual, then adding an option to translate your questions into another language can also prove beneficial.

Step 4: Type of Questions

In a survey, you can include any type of questions and even both closed-ended or open-ended questions. However, opt for the question types that are the easiest to understand for the respondents, and offer the most value. For example, compared to open-ended questions, people prefer to answer close-ended questions such as MCQs (multiple choice questions)and NPS (net promoter score) questions.

Step 5: User Experience

Designing a great survey is about more than just questions. A lot of researchers underestimate the importance of user experience and how it affects their response and completion rates. An inconsistent, difficult-to-navigate survey with technical errors and poor color choice is unappealing for the respondents. Make sure that your survey is easy to navigate for everyone and if you’re using rating scales, they remain consistent throughout the research study.

Additionally, don’t forget to design a good survey experience for both mobile and desktop users. According to Pew Research Center, nearly half of the smartphone users access the internet mainly from their mobile phones and 14 percent of American adults are smartphone-only internet users. ( 3 )

Step 6: Survey Logic

Last but not least, logic is another critical aspect of the survey design. If the survey logic is flawed, respondents may not continue in the right direction. Make sure to test the logic to ensure that selecting one answer leads to the next logical question instead of a series of unrelated queries.

How to Effectively Use Survey Research with Starlight Analytics

Designing and conducting a survey is almost as much science as it is an art. To craft great survey research, you need technical skills, consider the psychological elements, and have a broad understanding of marketing.

The ultimate goal of the survey is to ask the right questions in the right manner to acquire the right results.

Bringing a new product to the market is a long process and requires a lot of research and analysis. In your journey to gather information or ideas for your business, Starlight Analytics can be an excellent guide. Starlight Analytics' product concept testing helps you measure your product's market demand and refine product features and benefits so you can launch with confidence. The process starts with custom research to design the survey according to your needs, execute the survey, and deliver the key insights on time.

- Survey research in the United States: roots and emergence, 1890-1960 https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/10733873

- How to create a survey questionnaire that gets great responses https://luc.id/knowledgehub/how-to-create-a-survey-questionnaire-that-gets-great-responses/

- Internet/broadband fact sheet https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

Related Articles

A guide to competitive analysis & how to outperform your competitors.

Learn all about competitive analysis and its frameworks along with a step-by-step guide to conduct competitive analysis and outperform your competitors.

Fuel your innovation with data - Custom AI-powered Research

Need fresh innovation ideas? Read more about our custom AI-powered methods that generate + prioritize new product ideas for your innovation pipeline.

What is Product Positioning? (Examples and Strategies)

Launching a new product is a long and arduous process. Learn how to define and differentiate your product for maximum success with a product positioning strategy.

The Introduction Stage of Product Life Cycle | What to Know

The introduction stage in the product life cycle is meant to build product awareness. Click here to learn more about the introduction stage and how it works.

Product Life Cycle | What is it and What are the Stages?

The product life cycle outlines a product's journey from introduction to decline. Learn all about the product life cycle, its stages, and examples here.

The Growth Stage of Product Life Cycle | What to Know

All you need to know about the growth stage of the product life cycle and how you should make your product during this stage.

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

What is a survey?

- Survey vs Questionnaire

Try Qualtrics for free

Survey vs questionnaire: the differences for market research.

12 min read If you’re looking to gain valuable insight into markets, businesses, customer perceptions and general feelings towards events or products at scale, look no further than surveys and questionnaires. In this article, we’ll cover the differences between the two terms and how to use them to best effect.

People and businesses use and complete surveys and questionnaires all the time.

Whether it’s to plan marketing campaigns or identify areas of opportunity, surveys and questionnaires enable us to gain valuable insight into markets, businesses, customer perceptions and sentiment and much more at scale.

But more often than not, people and businesses use the terms survey and questionnaire interchangeably — when in reality, they are two different disciplines.

Especially when it comes to market research .

Now, it’s easy to see why: both ask questions and aim to gather useful insights.

However, there are several differences between the two, and the method you decide to use is ultimately determined by the information you are trying to gather. So, what are the differences?

Find out about Qualtrics CoreXM and how it can transform your research

What is a questionnaire?

A questionnaire uses a set of questions to gain answers from a set of respondents. Questionnaires are often used to understand information like customer feedback and usually include a series of closed (yes/no) questions, with the occasional open-ended question to gain qualitative insights.

You can also use a questionnaire to gather information on specific issues like customer preferences and behaviors. You can conduct questionnaires over the phone, online or in-person.

A survey can be a more in-depth form of data collection to gather data from a specific target audience and survey respondents. It’s also more complex than a questionnaire.

Researchers can use the data gathered from a survey for statistical analysis to evaluate the data and responses, and generate conclusions from the responses to the survey questions.

Now, while you can also use a questionnaire in a research project to gather information — and it still collects high-quality data — surveys have several layers to consider, including:

- The design of the survey

- What type of sampling to use to create an effective survey

- The method of data collection

- Aggregation of data

- How and what method you’ll apply to the data analysis to understand the results glean actionable insights.

Ultimately, while a questionnaire is a list of questions to gather certain information, a survey can help researchers understand the bigger picture of a topic or issue to drive business action. That is the key difference.

Survey vs questionnaire examples

Now that you understand the basics, how can we differentiate the two further? Here are few examples to give you a better understanding of what we mean:

A questionnaire is a logical list of questions that a business uses to gather specific information from many respondents (not necessarily a certain group) — we know that — but how might you use it in a business context?

For example, you might use a questionnaire to gather customer information when they need to make a payment (name, bank details etc), or you might use one to accept donations. If you’re building a brand-new marketing campaign, you might send out a questionnaire to capture new prospect names and then send out a survey — once they become customers — to determine their level of satisfaction or loyalty.

Here’s another example — doctors and nurses use questionnaires when gathering medical histories of patients. They would then use a survey to understand patient satisfaction and to determine how those patients feel about the standard of care.

To summarize: you use questionnaires to capture specific information about an individual.

So what if you wanted to use questionnaires for your recruitment process? Well, a typical recruitment questionnaire follows a logical step-by-step approach to get a ‘feel’ for a candidate — their aims and objectives, experience, what they can bring to the job and so on. It’s very much like an interview, just far less personal.

But if you wanted to understand the thoughts and feelings about your interview process as a whole, you could design a survey for candidates (and successful hires) to understand trends, including collecting personal accounts, which your hiring team can use in the future.

You could also create surveys for your own hiring team to fill out and use their responses to uncover any gaps in your process.

Remember: the main difference between a questionnaire and a survey is that a questionnaire is often used to get information from an individual, while a survey is a method of data collection targeted at a specific group.

What data can you collect using surveys?

Researchers use surveys to gather both qualitative and quantitative data. Note — qualitative surveys use open-ended questions or video response options to produce long-form written or typed responses.

The main data types you’ll gather from surveys are:

Qualitative data

Qualitative data is most typically gathered in the form of longer, more descriptive answers and responses from your target audience. It looks at the “Why” behind the “What”.

Qualitative data is gathered when you need information that’s difficult to count or measured statistically, or when you need specific insights.

The data is usually gathered through the use of open-ended questions, but there are plenty of other qualitative methods beyond open-ends in surveys, such as:

Ethnographic research

Ethnography is the study of direct observation of users in their natural environment. The objective of this type of research is to gain insights into how users normally interact. Methods include direct observation, diary studies, video recordings and much more.

Moderated focus groups

Focus groups allow researchers to generate guided discussion around topics of choice. The moderator starts the discussion, but allows respondents (or participants) to construct the conversation, providing real-time insight. The moderator’s role is to ensure the conversation stays on track and is relevant.

Moderated discussions

Similar to focus groups, discussion boards are useful for collecting dynamic data. Much like an online forum, researchers can prompt a topic for discussion. It’s a much more interactive way to generate qualitative data, and allows researchers to flex their level of input.

Video responses

Another great way to acquire good qualitative research is through video feedback. As our lives become increasingly digital and more brands and businesses move online, researchers need a way to capture qualitative feedback and at scale. Through video responses provided in surveys, researchers get more authentic, natural and insightful feedback from respondents.

Quantitative data

Quantitative data is more statistical data when research is based on numerical data. It’s more concerned with the “What”.

This type of data is used to understand “hard” facts. For example, it’s often used to assess a content strategy when you want to understand or find trends in consumer behavior, or how they’re interacting with your content.

Within the two camps of quantitative and qualitative data, there are several other types of research data that can be collected:

Nominal data is information that’s classified into specific categories, but you can’t order it or measure it in any meaningful way for data analysis.

For example, data that highlights someone’s favorite item of clothing — with the categories being t-shirts, jeans, shorts, etc.

Ordinal data is detailed data in which data values follow a natural order. It’s commonly used in surveys and questionnaires to uncover preferences or agreement levels towards certain statements.

The likert scale is an example of ordinal data in which a survey may ask a respondent to choose between “Strongly Agree”, “Agree” etc. You can use ordinal data with advanced analysis tools like hypothesis testing.

Discrete data is data that can only take particular values, but doesn’t necessarily use whole numbers. A prime example of discrete data is the amount of profit a business makes in a given month.

Continuous data is a type of numerical data that refers to the unspecified number of possible measurements (or points) between two realistic variables. Continuous data, as such, is often referred to as ‘infinite’ data. Generally, continuous data is measured using a scale. Typical examples of continuous data are temperature, distance or weight. Due to the infinite nature of continuous data, it can change over time.

Research methods for surveys and questionnaires

As well as having different data types, surveys and questionnaires also use several research methods to gather information — these include:

Qualitative research

Qualitative research is the process of obtaining non-numerical data for use in research and decision making.

Qualitative research usually involves in-depth questioning of respondents to gather detailed survey data. For example, a researcher might carry out interviews, focus groups and/or one-to-one discussions to capture data.

Quantitative research

Quantitative research is about gathering statistical (numerical) data that researchers can use to uncover trends that guide decision making and future planning. For example, customer satisfaction surveys (CSATs) or Net Promoter Score (NPS) surveys are both examples of quantitative research.

Descriptive research

Descriptive research helps researchers to understand the characteristics of a population, situation, or phenomenon that they are studying. It’s more concerned with questions that answer the who, what, where and when, rather than the why.

Analytical research

Analytical research helps researchers to understand why certain things happen and the order in which they happened. They can then apply critical thinking to get a grip on the situation. This type of research can be extremely useful for research used to lead strategic decision making.

Applied research

Applied research is a type of examination that focuses on finding practical solutions to solve real-life problems. For example, challenges in the workplace or improving employee productivity.

Exploratory research

Exploratory research uses a range of quantitative and qualitative methods to look into a topic that hasn’t already been widely investigated.

Questionnaire survey method

Ultimately, while surveys and questionnaires are often used interchangeably, for anyone looking for in-depth insights to guide decisions or improve processes, surveys are far superior.

The fact is, surveys offer far more opportunities to collect and analyze data at scale to uncover critical, business-changing insights. And with the right tools, you can create high-quality surveys that attract and engage target audiences, ensuring you get the responses you need to make changes and improve experiences.

And Qualtrics CoreXM is exactly what you need to do so.

With Qualtrics CoreXM, you can empower everyone in your organization to carry out research — at scale — and get insights faster than ever before.

Featuring a suite of best-in-class analytics tools and an intuitive drag-and-drop interface, carry out end-to-end market research projects and generate the insights you need to drive meaningful change.

And with machine learning and AI-powered analysis, you can turn everyday data into a goldmine and use our built-in tool for assessing survey methodology to ensure you get high-quality responses.

Related resources

Response bias 13 min read, double barreled question 11 min read, likert scales 14 min read, survey research 15 min read, survey bias types 24 min read, post event survey questions 10 min read, best survey software 16 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 8: Data Collection Methods: Survey Research

8.2 Understanding the Difference between a Survey and a Questionnaire

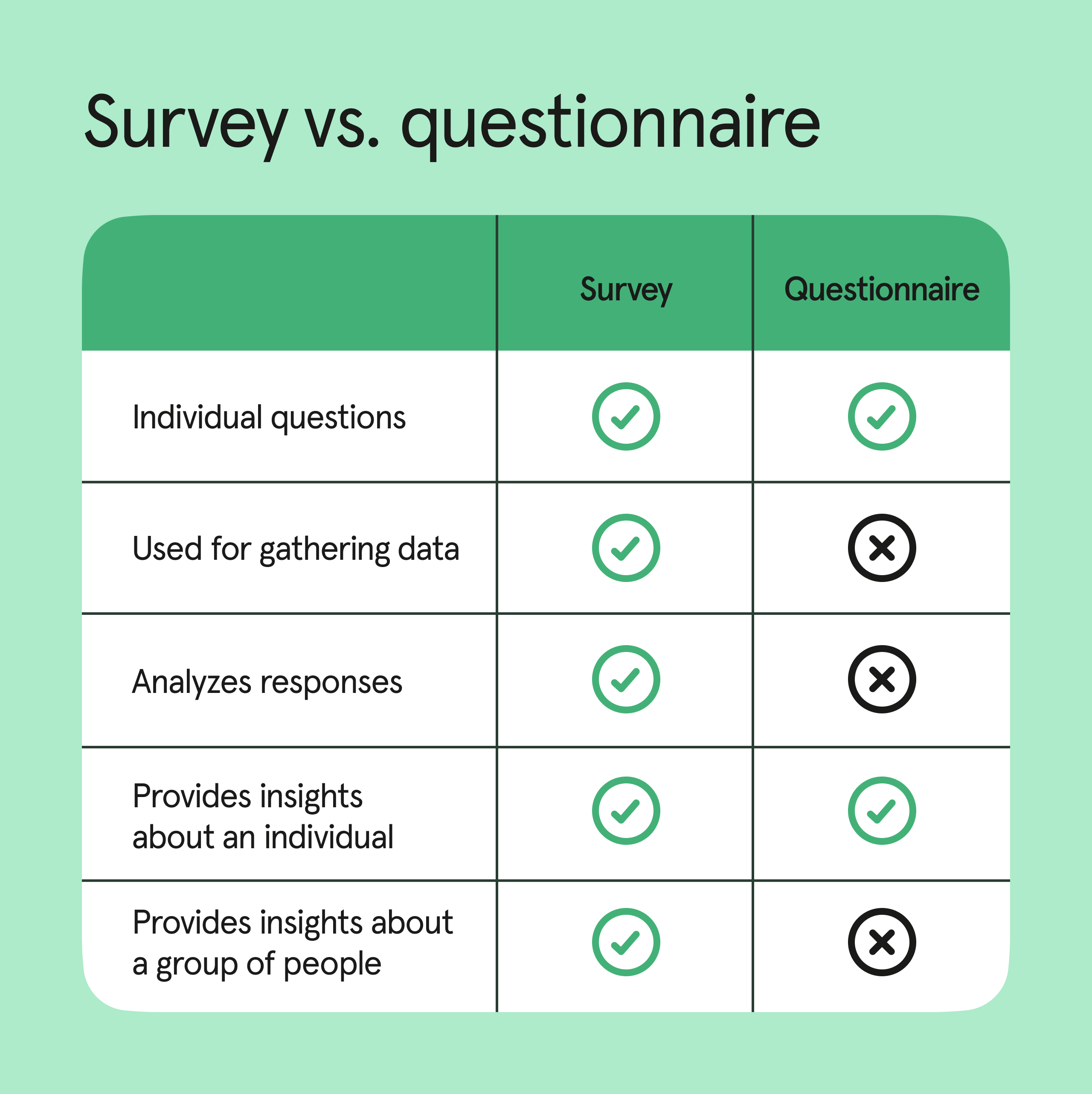

Before we move on to look at the strengths and weaknesses of survey research, we will take a step back to make sure you understand the difference between the concepts of surveys and questionnaires. Both surveys and questionnaires use a series of questions to gather information, however the purpose of the research and the treatment of the data after it is collected distinguish a questionnaire from a survey, e.g.:

- A questionnaire is a set of written questions used for collecting information for the benefit of one single individual.

- A survey is a process of gathering information for statistical analysis to the benefit of a group of individuals (a research method).

- A questionnaire does not aggregate data for statistical analysis after the data is collected, whereas survey responses are aggregated to draw conclusions.

A questionnaire is the set of questions that are used to gather the information, whereas a survey is a process of collecting and analyzing data. If the collected data will not be aggregated and is solely for the benefit of the respondent, then that is a questionnaire. If the data being collected with be aggregated and used for analytical purposes that is a survey (McKay, 2015). Sometimes questionnaire data is aggregated; it then becomes a survey, sometimes without the participant’s knowledge. For example, the bank where you filled in a loan application aggregates the data from all loan applications in the year 2017 and presents the information to shareholders in aggregated form at its 2018 annual general meeting. The bank has taken questionnaire data and aggregated it into survey data.

Understanding the difference between a survey and a questionnaire.

Adapted from Surbhi, S. (2016). Difference between survey and questionnaire. Retrieved from https://keydifferences.com/difference-between-survey-and-questionnaire.html

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Frequently asked questions

What’s the difference between questionnaires and surveys.

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analyzing data from people using questionnaires.

Frequently asked questions: Methodology

Attrition refers to participants leaving a study. It always happens to some extent—for example, in randomized controlled trials for medical research.

Differential attrition occurs when attrition or dropout rates differ systematically between the intervention and the control group . As a result, the characteristics of the participants who drop out differ from the characteristics of those who stay in the study. Because of this, study results may be biased .

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

To make quantitative observations , you need to use instruments that are capable of measuring the quantity you want to observe. For example, you might use a ruler to measure the length of an object or a thermometer to measure its temperature.

Criterion validity and construct validity are both types of measurement validity . In other words, they both show you how accurately a method measures something.

While construct validity is the degree to which a test or other measurement method measures what it claims to measure, criterion validity is the degree to which a test can predictively (in the future) or concurrently (in the present) measure something.

Construct validity is often considered the overarching type of measurement validity . You need to have face validity , content validity , and criterion validity in order to achieve construct validity.

Convergent validity and discriminant validity are both subtypes of construct validity . Together, they help you evaluate whether a test measures the concept it was designed to measure.

- Convergent validity indicates whether a test that is designed to measure a particular construct correlates with other tests that assess the same or similar construct.

- Discriminant validity indicates whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed not related. This type of validity is also called divergent validity .

You need to assess both in order to demonstrate construct validity. Neither one alone is sufficient for establishing construct validity.

- Discriminant validity indicates whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed not related

Content validity shows you how accurately a test or other measurement method taps into the various aspects of the specific construct you are researching.

In other words, it helps you answer the question: “does the test measure all aspects of the construct I want to measure?” If it does, then the test has high content validity.

The higher the content validity, the more accurate the measurement of the construct.

If the test fails to include parts of the construct, or irrelevant parts are included, the validity of the instrument is threatened, which brings your results into question.

Face validity and content validity are similar in that they both evaluate how suitable the content of a test is. The difference is that face validity is subjective, and assesses content at surface level.

When a test has strong face validity, anyone would agree that the test’s questions appear to measure what they are intended to measure.

For example, looking at a 4th grade math test consisting of problems in which students have to add and multiply, most people would agree that it has strong face validity (i.e., it looks like a math test).

On the other hand, content validity evaluates how well a test represents all the aspects of a topic. Assessing content validity is more systematic and relies on expert evaluation. of each question, analyzing whether each one covers the aspects that the test was designed to cover.

A 4th grade math test would have high content validity if it covered all the skills taught in that grade. Experts(in this case, math teachers), would have to evaluate the content validity by comparing the test to the learning objectives.

Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling method . Unlike probability sampling (which involves some form of random selection ), the initial individuals selected to be studied are the ones who recruit new participants.

Because not every member of the target population has an equal chance of being recruited into the sample, selection in snowball sampling is non-random.

Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling method , where there is not an equal chance for every member of the population to be included in the sample .

This means that you cannot use inferential statistics and make generalizations —often the goal of quantitative research . As such, a snowball sample is not representative of the target population and is usually a better fit for qualitative research .

Snowball sampling relies on the use of referrals. Here, the researcher recruits one or more initial participants, who then recruit the next ones.

Participants share similar characteristics and/or know each other. Because of this, not every member of the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample, giving rise to sampling bias .

Snowball sampling is best used in the following cases:

- If there is no sampling frame available (e.g., people with a rare disease)

- If the population of interest is hard to access or locate (e.g., people experiencing homelessness)

- If the research focuses on a sensitive topic (e.g., extramarital affairs)

The reproducibility and replicability of a study can be ensured by writing a transparent, detailed method section and using clear, unambiguous language.

Reproducibility and replicability are related terms.

- Reproducing research entails reanalyzing the existing data in the same manner.

- Replicating (or repeating ) the research entails reconducting the entire analysis, including the collection of new data .

- A successful reproduction shows that the data analyses were conducted in a fair and honest manner.

- A successful replication shows that the reliability of the results is high.

Stratified sampling and quota sampling both involve dividing the population into subgroups and selecting units from each subgroup. The purpose in both cases is to select a representative sample and/or to allow comparisons between subgroups.

The main difference is that in stratified sampling, you draw a random sample from each subgroup ( probability sampling ). In quota sampling you select a predetermined number or proportion of units, in a non-random manner ( non-probability sampling ).

Purposive and convenience sampling are both sampling methods that are typically used in qualitative data collection.

A convenience sample is drawn from a source that is conveniently accessible to the researcher. Convenience sampling does not distinguish characteristics among the participants. On the other hand, purposive sampling focuses on selecting participants possessing characteristics associated with the research study.

The findings of studies based on either convenience or purposive sampling can only be generalized to the (sub)population from which the sample is drawn, and not to the entire population.

Random sampling or probability sampling is based on random selection. This means that each unit has an equal chance (i.e., equal probability) of being included in the sample.

On the other hand, convenience sampling involves stopping people at random, which means that not everyone has an equal chance of being selected depending on the place, time, or day you are collecting your data.