- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Descriptive Research Design

Definition:

Descriptive research design is a type of research methodology that aims to describe or document the characteristics, behaviors, attitudes, opinions, or perceptions of a group or population being studied.

Descriptive research design does not attempt to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables or make predictions about future outcomes. Instead, it focuses on providing a detailed and accurate representation of the data collected, which can be useful for generating hypotheses, exploring trends, and identifying patterns in the data.

Types of Descriptive Research Design

Types of Descriptive Research Design are as follows:

Cross-sectional Study

This involves collecting data at a single point in time from a sample or population to describe their characteristics or behaviors. For example, a researcher may conduct a cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence of certain health conditions among a population, or to describe the attitudes and beliefs of a particular group.

Longitudinal Study

This involves collecting data over an extended period of time, often through repeated observations or surveys of the same group or population. Longitudinal studies can be used to track changes in attitudes, behaviors, or outcomes over time, or to investigate the effects of interventions or treatments.

This involves an in-depth examination of a single individual, group, or situation to gain a detailed understanding of its characteristics or dynamics. Case studies are often used in psychology, sociology, and business to explore complex phenomena or to generate hypotheses for further research.

Survey Research

This involves collecting data from a sample or population through standardized questionnaires or interviews. Surveys can be used to describe attitudes, opinions, behaviors, or demographic characteristics of a group, and can be conducted in person, by phone, or online.

Observational Research

This involves observing and documenting the behavior or interactions of individuals or groups in a natural or controlled setting. Observational studies can be used to describe social, cultural, or environmental phenomena, or to investigate the effects of interventions or treatments.

Correlational Research

This involves examining the relationships between two or more variables to describe their patterns or associations. Correlational studies can be used to identify potential causal relationships or to explore the strength and direction of relationships between variables.

Data Analysis Methods

Descriptive research design data analysis methods depend on the type of data collected and the research question being addressed. Here are some common methods of data analysis for descriptive research:

Descriptive Statistics

This method involves analyzing data to summarize and describe the key features of a sample or population. Descriptive statistics can include measures of central tendency (e.g., mean, median, mode) and measures of variability (e.g., range, standard deviation).

Cross-tabulation

This method involves analyzing data by creating a table that shows the frequency of two or more variables together. Cross-tabulation can help identify patterns or relationships between variables.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing qualitative data (e.g., text, images, audio) to identify themes, patterns, or trends. Content analysis can be used to describe the characteristics of a sample or population, or to identify factors that influence attitudes or behaviors.

Qualitative Coding

This method involves analyzing qualitative data by assigning codes to segments of data based on their meaning or content. Qualitative coding can be used to identify common themes, patterns, or categories within the data.

Visualization

This method involves creating graphs or charts to represent data visually. Visualization can help identify patterns or relationships between variables and make it easier to communicate findings to others.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing data across different groups or time periods to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can help describe changes in attitudes or behaviors over time or differences between subgroups within a population.

Applications of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has numerous applications in various fields. Some of the common applications of descriptive research design are:

- Market research: Descriptive research design is widely used in market research to understand consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes. This helps companies to develop new products and services, improve marketing strategies, and increase customer satisfaction.

- Health research: Descriptive research design is used in health research to describe the prevalence and distribution of a disease or health condition in a population. This helps healthcare providers to develop prevention and treatment strategies.

- Educational research: Descriptive research design is used in educational research to describe the performance of students, schools, or educational programs. This helps educators to improve teaching methods and develop effective educational programs.

- Social science research: Descriptive research design is used in social science research to describe social phenomena such as cultural norms, values, and beliefs. This helps researchers to understand social behavior and develop effective policies.

- Public opinion research: Descriptive research design is used in public opinion research to understand the opinions and attitudes of the general public on various issues. This helps policymakers to develop effective policies that are aligned with public opinion.

- Environmental research: Descriptive research design is used in environmental research to describe the environmental conditions of a particular region or ecosystem. This helps policymakers and environmentalists to develop effective conservation and preservation strategies.

Descriptive Research Design Examples

Here are some real-time examples of descriptive research designs:

- A restaurant chain wants to understand the demographics and attitudes of its customers. They conduct a survey asking customers about their age, gender, income, frequency of visits, favorite menu items, and overall satisfaction. The survey data is analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation to describe the characteristics of their customer base.

- A medical researcher wants to describe the prevalence and risk factors of a particular disease in a population. They conduct a cross-sectional study in which they collect data from a sample of individuals using a standardized questionnaire. The data is analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation to identify patterns in the prevalence and risk factors of the disease.

- An education researcher wants to describe the learning outcomes of students in a particular school district. They collect test scores from a representative sample of students in the district and use descriptive statistics to calculate the mean, median, and standard deviation of the scores. They also create visualizations such as histograms and box plots to show the distribution of scores.

- A marketing team wants to understand the attitudes and behaviors of consumers towards a new product. They conduct a series of focus groups and use qualitative coding to identify common themes and patterns in the data. They also create visualizations such as word clouds to show the most frequently mentioned topics.

- An environmental scientist wants to describe the biodiversity of a particular ecosystem. They conduct an observational study in which they collect data on the species and abundance of plants and animals in the ecosystem. The data is analyzed using descriptive statistics to describe the diversity and richness of the ecosystem.

How to Conduct Descriptive Research Design

To conduct a descriptive research design, you can follow these general steps:

- Define your research question: Clearly define the research question or problem that you want to address. Your research question should be specific and focused to guide your data collection and analysis.

- Choose your research method: Select the most appropriate research method for your research question. As discussed earlier, common research methods for descriptive research include surveys, case studies, observational studies, cross-sectional studies, and longitudinal studies.

- Design your study: Plan the details of your study, including the sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis plan. Determine the sample size and sampling method, decide on the data collection tools (such as questionnaires, interviews, or observations), and outline your data analysis plan.

- Collect data: Collect data from your sample or population using the data collection tools you have chosen. Ensure that you follow ethical guidelines for research and obtain informed consent from participants.

- Analyze data: Use appropriate statistical or qualitative analysis methods to analyze your data. As discussed earlier, common data analysis methods for descriptive research include descriptive statistics, cross-tabulation, content analysis, qualitative coding, visualization, and comparative analysis.

- I nterpret results: Interpret your findings in light of your research question and objectives. Identify patterns, trends, and relationships in the data, and describe the characteristics of your sample or population.

- Draw conclusions and report results: Draw conclusions based on your analysis and interpretation of the data. Report your results in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate tables, graphs, or figures to present your findings. Ensure that your report follows accepted research standards and guidelines.

When to Use Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design is used in situations where the researcher wants to describe a population or phenomenon in detail. It is used to gather information about the current status or condition of a group or phenomenon without making any causal inferences. Descriptive research design is useful in the following situations:

- Exploratory research: Descriptive research design is often used in exploratory research to gain an initial understanding of a phenomenon or population.

- Identifying trends: Descriptive research design can be used to identify trends or patterns in a population, such as changes in consumer behavior or attitudes over time.

- Market research: Descriptive research design is commonly used in market research to understand consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes.

- Health research: Descriptive research design is useful in health research to describe the prevalence and distribution of a disease or health condition in a population.

- Social science research: Descriptive research design is used in social science research to describe social phenomena such as cultural norms, values, and beliefs.

- Educational research: Descriptive research design is used in educational research to describe the performance of students, schools, or educational programs.

Purpose of Descriptive Research Design

The main purpose of descriptive research design is to describe and measure the characteristics of a population or phenomenon in a systematic and objective manner. It involves collecting data that describe the current status or condition of the population or phenomenon of interest, without manipulating or altering any variables.

The purpose of descriptive research design can be summarized as follows:

- To provide an accurate description of a population or phenomenon: Descriptive research design aims to provide a comprehensive and accurate description of a population or phenomenon of interest. This can help researchers to develop a better understanding of the characteristics of the population or phenomenon.

- To identify trends and patterns: Descriptive research design can help researchers to identify trends and patterns in the data, such as changes in behavior or attitudes over time. This can be useful for making predictions and developing strategies.

- To generate hypotheses: Descriptive research design can be used to generate hypotheses or research questions that can be tested in future studies. For example, if a descriptive study finds a correlation between two variables, this could lead to the development of a hypothesis about the causal relationship between the variables.

- To establish a baseline: Descriptive research design can establish a baseline or starting point for future research. This can be useful for comparing data from different time periods or populations.

Characteristics of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has several key characteristics that distinguish it from other research designs. Some of the main characteristics of descriptive research design are:

- Objective : Descriptive research design is objective in nature, which means that it focuses on collecting factual and accurate data without any personal bias. The researcher aims to report the data objectively without any personal interpretation.

- Non-experimental: Descriptive research design is non-experimental, which means that the researcher does not manipulate any variables. The researcher simply observes and records the behavior or characteristics of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Quantitative : Descriptive research design is quantitative in nature, which means that it involves collecting numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical techniques. This helps to provide a more precise and accurate description of the population or phenomenon.

- Cross-sectional: Descriptive research design is often cross-sectional, which means that the data is collected at a single point in time. This can be useful for understanding the current state of the population or phenomenon, but it may not provide information about changes over time.

- Large sample size: Descriptive research design typically involves a large sample size, which helps to ensure that the data is representative of the population of interest. A large sample size also helps to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

- Systematic and structured: Descriptive research design involves a systematic and structured approach to data collection, which helps to ensure that the data is accurate and reliable. This involves using standardized procedures for data collection, such as surveys, questionnaires, or observation checklists.

Advantages of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has several advantages that make it a popular choice for researchers. Some of the main advantages of descriptive research design are:

- Provides an accurate description: Descriptive research design is focused on accurately describing the characteristics of a population or phenomenon. This can help researchers to develop a better understanding of the subject of interest.

- Easy to conduct: Descriptive research design is relatively easy to conduct and requires minimal resources compared to other research designs. It can be conducted quickly and efficiently, and data can be collected through surveys, questionnaires, or observations.

- Useful for generating hypotheses: Descriptive research design can be used to generate hypotheses or research questions that can be tested in future studies. For example, if a descriptive study finds a correlation between two variables, this could lead to the development of a hypothesis about the causal relationship between the variables.

- Large sample size : Descriptive research design typically involves a large sample size, which helps to ensure that the data is representative of the population of interest. A large sample size also helps to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

- Can be used to monitor changes : Descriptive research design can be used to monitor changes over time in a population or phenomenon. This can be useful for identifying trends and patterns, and for making predictions about future behavior or attitudes.

- Can be used in a variety of fields : Descriptive research design can be used in a variety of fields, including social sciences, healthcare, business, and education.

Limitation of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design also has some limitations that researchers should consider before using this design. Some of the main limitations of descriptive research design are:

- Cannot establish cause and effect: Descriptive research design cannot establish cause and effect relationships between variables. It only provides a description of the characteristics of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Limited generalizability: The results of a descriptive study may not be generalizable to other populations or situations. This is because descriptive research design often involves a specific sample or situation, which may not be representative of the broader population.

- Potential for bias: Descriptive research design can be subject to bias, particularly if the researcher is not objective in their data collection or interpretation. This can lead to inaccurate or incomplete descriptions of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Limited depth: Descriptive research design may provide a superficial description of the population or phenomenon of interest. It does not delve into the underlying causes or mechanisms behind the observed behavior or characteristics.

- Limited utility for theory development: Descriptive research design may not be useful for developing theories about the relationship between variables. It only provides a description of the variables themselves.

- Relies on self-report data: Descriptive research design often relies on self-report data, such as surveys or questionnaires. This type of data may be subject to biases, such as social desirability bias or recall bias.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 14: Descriptive Research

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Introduction, developmental research.

- NORMATIVE STUDIES

- QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

- DESCRIPTIVE SURVEYS

- CASE STUDIES

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Descriptive research is designed to document the factors that describe characteristics, behaviors and conditions of individuals and groups. For example, researchers have used this approach to describe a sample of individuals with spinal cord injuries with respect to gender, age, and cause and severity of injury to see whether these properties were similar to those described in the past. 1 Descriptive studies have documented the biomechanical parameters of wheelchair propulsion, 2 and the clinical characteristics of stroke. 3 As our diagram of the continuum of research shows, descriptive and exploratory elements are commonly combined, depending on how the investigator conceptualizes the research question.

Descriptive studies document the nature of existing phenomena and describe how variables change over time. They will generally be structured around a set of guiding questions or research objectives to generate data or characterize a situation of interest. Often this information can be used as a basis for formulation of research hypotheses that can be tested using exploratory or experimental techniques. The descriptive data supply the foundation for classifying individuals, for identifying relevant variables, and for asking new research questions.

Descriptive studies may involve prospective or retrospective data collection, and may be designed using longitudinal or cross-sectional methods (see Chapter 13 ). Surveys and secondary analysis of clinical databases are often used as sources of data for descriptive analysis. Several types of research can be categorized as descriptive, including developmental research, normative research, qualitative research and case studies. The purpose of this chapter is to describe these approaches.

Concepts of human development, whether they are related to cognition, perceptual-motor control, communication, physiological change, or psychological processes, are important elements of a clinical knowledge base. Valid interpretation of clinical outcomes depends on our ability to develop a clear picture of those we treat, their characteristics and performance expectations under different conditions. Developmental research involves the description of developmental change and the sequencing of behaviors in people over time. Developmental studies have contributed to the theoretical foundations of clinical practice in many ways. For example, the classic descriptive studies of Gesell and Amatruda 4 and McGraw 5 provide the basis for much of the research on sequencing of motor development in infants and children. Erikson's studies of life span development have contributed to an understanding of psychological growth through old age. 6

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples

Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples

Published on May 15, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Descriptive research aims to accurately and systematically describe a population, situation or phenomenon. It can answer what , where , when and how questions , but not why questions.

A descriptive research design can use a wide variety of research methods to investigate one or more variables . Unlike in experimental research , the researcher does not control or manipulate any of the variables, but only observes and measures them.

Table of contents

When to use a descriptive research design, descriptive research methods, other interesting articles.

Descriptive research is an appropriate choice when the research aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories.

It is useful when not much is known yet about the topic or problem. Before you can research why something happens, you need to understand how, when and where it happens.

Descriptive research question examples

- How has the Amsterdam housing market changed over the past 20 years?

- Do customers of company X prefer product X or product Y?

- What are the main genetic, behavioural and morphological differences between European wildcats and domestic cats?

- What are the most popular online news sources among under-18s?

- How prevalent is disease A in population B?

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Descriptive research is usually defined as a type of quantitative research , though qualitative research can also be used for descriptive purposes. The research design should be carefully developed to ensure that the results are valid and reliable .

Survey research allows you to gather large volumes of data that can be analyzed for frequencies, averages and patterns. Common uses of surveys include:

- Describing the demographics of a country or region

- Gauging public opinion on political and social topics

- Evaluating satisfaction with a company’s products or an organization’s services

Observations

Observations allow you to gather data on behaviours and phenomena without having to rely on the honesty and accuracy of respondents. This method is often used by psychological, social and market researchers to understand how people act in real-life situations.

Observation of physical entities and phenomena is also an important part of research in the natural sciences. Before you can develop testable hypotheses , models or theories, it’s necessary to observe and systematically describe the subject under investigation.

Case studies

A case study can be used to describe the characteristics of a specific subject (such as a person, group, event or organization). Instead of gathering a large volume of data to identify patterns across time or location, case studies gather detailed data to identify the characteristics of a narrowly defined subject.

Rather than aiming to describe generalizable facts, case studies often focus on unusual or interesting cases that challenge assumptions, add complexity, or reveal something new about a research problem .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/descriptive-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is quantitative research | definition, uses & methods, correlational research | when & how to use, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 November 2009

A descriptive study of medical educators' views of problem-based learning

- Mohsen Tavakol 1 ,

- Reg Dennick 1 &

- Sina Tavakol 2

BMC Medical Education volume 9 , Article number: 66 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

13 Citations

Metrics details

There is a growing amount of literature on the benefits and drawbacks of Problem-Based Learning (PBL) compared to conventional curricula. However, it seems that PBL research studies do not provide information rigorously and formally that can contribute to making evidence-based medical education decisions. The authors performed an investigation aimed at medical education scholars around the question, "What are the views of medical educators concerning the PBL approach?"

After framing the question, the method of data collection relied on asking medical educators to report their views on PBL. Two methods were used for collecting data: the questionnaire survey and an online discussion forum.

The descriptive analysis of the study showed that many participants value the PBL approach in the practice and training of doctors. However, some participants hold contrasting views upon the importance of the PBL approach in basic medical education. For example, more than a third of participants (38.5%) had a neutral stance on PBL as a student-oriented educational approach. The same proportion of participants also had a neutral view of the efficiency of traditional learning compared to a PBL tutorial. The open-ended question explored the importance of faculty development in PBL. A few participants had negative perceptions of the epistemological assumptions of PBL. Two themes emerged from the analysis of the forum repliers: the importance of the faculty role and self-managed education.

Whilst many participants valued the importance of the PBL approach in the practice and training of doctors and agreed with most of the conventional descriptions of PBL, some participants held contrasting views on the importance of the PBL approach in undergraduate medical education. However there was a strong view concerning the importance of facilitator training. More research is needed to understand the process of PBL better.

Peer Review reports

PBL is possibly one of the most innovative themes in medical education; it has raised extreme debate and still continues to generate passionate discussions. There is a growing amount of literature on the benefits and drawbacks of PBL compared to conventional curricula. The experimental studies reported in the three reviews published in 1993 [ 1 – 3 ] showed that there is a dearth of good quality studies and evidence available regarding the hypothesis that PBL produces learners different to or superior to those derived from traditional methods [ 4 ]. This has led supporters and detractors to continue to investigate further the epistemological and ontological issues arising from the processes and outcomes of PBL. However, it has been asserted that the quality of medical education research is poor, repetitive, not informed by theory, methodologically weak and does not pay attention to validity threats in quasi-experimental designs [ 5 , 6 ]. A critical reading of studies on the methods and findings of PBL showed that they had not provided an evidence-base indicating the educational superiority of PBL despite the fact that such studies underpinned the effectiveness of PBL on attitudes, perceptions, self-rating and opinions [ 7 ]. It has also been argued that all forms of research involving subjectivity such as ethnography, grounded theory and phenomenology have been "unscientific" due to a lack of explicability, repeatability and replicability [ 8 ]. Therefore, qualitative studies, which explored the experiences and perceptions of students and tutors in programs that incorporated student-centred problem-based pedagogy, may not provide the best available evidence for the effectiveness of PBL curricula. Similarly, quantitative studies which compared the PBL approach with conventional teaching, might not illustrate the potential impact that it can have, if statistical effect size measures are not reported [ 9 ].

With respect to learning theories, PBL arose from the personal experiences and beliefs of a few medical educators [ 10 ] and it was arguably non-theoretical in its development. However, as PBL has evolved, some learning theories were claimed to support PBL [ 11 ]. In medical education, PBL has its roots in constructivist theories of learning [ 12 ]. However, Colliver has asserted that constructivism is not a theory of learning. "It provides a fleeting insight into the learning process, but it is not a theory of learning. It confuses epistemology and learning, and it would seem to offer little of value to medical education" [ 13 ]. Furthermore, when appraising some PBL quantitative papers, we noticed that the studies were not based on any learning theory or were not testing predictions from a learning theory. If a study tests a prediction or hypothesis based on a theory and the findings are consistent with the theory, then the findings are considered to support that theory [ 14 ]. Learning theory has not been used to design quantitative PBL studies and data from studies has not been used to support theory. Perhaps corruptions of quantitative inquiry approaches in recent years place the credibility of PBL at stake, and it may be argued that the findings generated are trivial or obvious.

Taken together, these ideas seem to indicate that PBL research studies do not provide information rigorously and formally that contribute to making evidence-based medical education decisions. Perhaps for this reason medical education scholars are still uncertain whether the PBL approach creates better physicians compared with traditional learning, or whether the PBL approach is superior to didactic basic and clinical teaching. Is "the glass half-full"? [ 15 ] or just "half empty?" [ 16 ]. While the benefits of curriculum reform are strongly cited, especially the increased use of PBL, there is a dearth of research assessing the effects of various curricula including PBL on preclinical and clinical measures of student performance. The exception to this is the longitudinal study on the impact of various curricula (including PBL) on student learning once they begin clinical practice. The authors concluded that changing curricula in medical education reform is not likely to have an impact on improvements in student achievement [ 17 ]. We do agree with Wood who stated that "performing outcomes based research in education is difficult because of the large range of confounding factors" [ 18 ]. Contrary to the conclusion of Wood, it seems that, for PBL, we do need to continue "arguing about the process and examine outcomes". This may bolster the promise of replication studies, which are necessary for the formation of a body of best evidence-based medical education practice, particularly for PBL.

We felt it important, therefore, to conduct a study, which is grounded in the benefits and drawbacks of current PBL research findings. We asked ourselves: What are the views of medical educators concerning the PBL approach? This study provides a new picture that may add to our overall understanding of PBL.

The study started in March 2006 in the UK, with a planned recruitment period of 18 months. The method of data collection relied on asking medical educators to report their views in a survey. Ethical approval was not sought as this was an opportunistic sample from volunteers at a one-day conference and web-based survey and by opting to reply to the questionnaire [see additional file 1 ], the participants automatically agreed to take part in this study, and consequently a consent form was not presented to them. The survey was an anonymous study. Two methods were used for collecting data. Firstly, questionnaires were distributed to a convenience sample of 65 medical educators, who participated in the 3 rd UK conference on Graduate Entry Medicine (GEM), 14 th July 2006. The number of completed, useable questionnaires was 33, giving a response rate of 51%. This low response rate led us to collect questionnaire data through the Internet in order to increase the sample size. For this, we embedded the same questionnaire in a web application that was only accessible through a confidential hyperlink. After a list of potential respondents was created (n = 27), an email including the hyperlink was sent out to the members of that list inviting them to participate in this study. The use of follow up reminders was ineffective in achieving higher response rate for the web-based survey. Six medical educators filled in the web-based survey. Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants.

The second method for collecting data was a discussion forum entitled "What have we learned from the PBL approach?" An email was forwarded to the members of the Evidence Based Medical Education (EBME) collaboration in order to ascertain their view on PBL. We asked medical educators who have experienced PBL to discuss their views on the PBL approach. Six members commented regarding the above question in a forum discussion. Therefore, in this study the purposive sample consisted of 39 medical education scholars and 6 forum repliers, with firsthand experience of PBL.

The design of the questionnaire was based on a thorough review of the literature relating to PBL studies. The PBL scale consists of 17 items about the conditions that hinder and support PBL. To reduce the bias of the questionnaire, some items were written negatively, so that not all questions reflected positive views towards PBL. Each item was accompanied by a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An open-ended question was provided to find out the medical educator's experience concerning the PBL approach. Medical educators also provided demographic information, which included items on their age, gender, and experience. A brief instruction for the completion of the study instrument was provided to ensure that it could be self-administered.

Prior to conducting the survey, the content validity of the instrument was established by subjecting it to review by two PBL experts. The experts were selected based on their deep experiences of PBL and their knowledge of the PBL process in their own school. We asked them to criticise the statements if they did not make sense or cover the purpose of the study. We took their comments on the questionnaire design into consideration, and we made appropriate modifications to clarifying meaning. We then tested the questionnaire for reliability with data from a group of individual participants (n = 20). The reliability of the tool was determined by computation of Chronbach's alpha using SPSS, which gave a value of 0.68, indicating an acceptable degree of internal consistency.

Because this study was primarily descriptive, descriptive information was presented for numerical data analysis. Words or sentences provided by participants in the open-ended questions have been reported in a table. The forum replies were also read and re-read in order to identify emerging themes as headings under which we can categorise most of the data.

The results of this study can best be treated under three headings: the PBL scale, open-ended question, and forum repliers.

The PBL scale

A sample of 39 medical educators from an accessible population was recruited (Table 1 ). The mean number of years work experience with facilitating was 7 years (SD 6.3, minimum 1 year, and maximum 30 years). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they perceived each of 17 items. Responses to agree and strongly agree were combined as "agree" and to disagree and strongly disagree were combined as "disagree". Most (69.2%) of respondents agreed that there is a difference between a PBL course and a conventional course. When asked to report whether they experienced PBL as a student- centred approach, more than a third of the respondents (36.2%) agreed. In response to the item, 'the facilitator needs to be expert in the subject matter of the case', the majority of respondents (61.6%) disagreed. More than a half of the respondents (51.3%) disagreed that 'Learning from a large group lecture is a more efficient way of learning than a PBL tutorial. Some respondents (35.9%) felt 'neutral' about increasing the number of doctors in the UK using graduate entry PBL. Most educators (62%) disagreed that the facilitator is not redundant in a PBL tutorial meeting. More than one fourth of respondents (25.7%) agreed that students are forced to participate in PBL by the facilitator. Few respondents (15.4%) had a neutral view on this. When asked to report if a lecture-based environment makes for better job satisfaction compared with a PBL course, more than a half of the respondents (51.3%) disagreed. The majority of participants (51.2%) disagreed that the students on a PBL course spend too much time elaborating their knowledge in comparison with a conventional course. As Table 2 shows, many participants valued the importance of the PBL approach in the practice and training of doctors. However, some participants held contrasting views upon the importance of the PBL approach in undergraduate medical education. For example, the scores showed that most participants had a neutral view of the efficiency of lecture-based learning compared to a PBL tutorial.

The open-ended question

Respondents were asked in an open ended question for their opinions on lessons they have learned or experienced during PBL tutorials. Of note was the low response to this question. For this reason, we analysed words and terms provided by the participants (Table 3 ). It is apparent from this table that the participants had concerns about issues relating to facilitators (items 3, 5, 6). The findings also indicated the importance that participants placed on student learning in PBL. One participant had concerns about the use of the PBL approach for Graduate Entry Medicine.

The forum repliers

Two general themes emerged from the forum repliers concerning medical educators' experiences of the PBL approach. They are: faculty role and self-managed education. We will now look at each of these in turn.

Faculty role

Participants in the forum had different views with respect to the PBL approach. One participant, who had graduated in medicine and experienced PBL, reflected that the PBL approach was useful in teaching 3 rd year medical students who are just entering their clinical training. This is because students integrate basic science with clinical application. Although one of the principal ideas behind PBL is that students aim their learning at the areas in which their knowledge is more deficient, one participant asserted that students sometimes " do not know what they don't know ". This finding may show that students are 'unconsciously incompetent', on the first stage of the conscious-competence framework in PBL. The participant described the facilitator role as crucial to effective learning in the PBL tutorial. He continued that students who had a process expert in discussion failed to catch key concepts and key pieces of information in their literature searching, or key insights in terms of understanding the questions they are addressing. The situation described below exemplifies this behaviour:

"...on the one hand clear objectives and faculty development are necessary so students are properly advised through the PBL exercise, such that they take ownership of their own learning and true self-directed learning can happen. Especially early in medical training, students cannot know what they need to learn in order to solve the problem. On the other hand, affirmation from a tutor that students are on the right track can very easily turn into direction from the tutor, and that can turn into teaching by the tutor."

A consultant stressed the importance of the faculty role in the PBL approach and strategies for successful facilitation. He found that the main barrier to implementation of PBL is the lack of preparation of faculty members to facilitate self-directed learning.

Self-managed education

In terms of the student-centred nature of the PBL approach, with its emphasis on self-directed learning, one respondent stated that the learning objectives of a PBL course do not provide the opportunity to encourage students to take greater ownership of their work, and hence greater responsibility for their learning. A participant replied:

"If clear learning objectives are prepared (not a list of subjects or objectives that use ambiguous words such as 'to understand'), and a series of concepts or principles are identified (those that the faculty think can be missed by the students), then the students can become truly a self-directed learner exerting a high degree of autonomy."

Another participant reflected on this situation:

"For me, the key question is, to what degree we believe in self-directed learning and convey to the students the message that they can take responsibility for their learning without our intervention?"

These perceptions indicate that the self-directed nature of PBL is still challenging. This may show that the participants interpreted self-directed learning as surface oriented self teaching. As such, this may indicate the students do not have control over all elements of the PBL process. Students, for example, have no control over the scenario, although the nature of self-directed learning of PBL is acknowledged.

This study has methodological limitations that must be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings. One cannot over-emphasise the limitations of self-report as this may limit the validity of findings. Respondents for various reasons may under, or overestimate their practice. A methodological problem frequently associated with the use of self-reports in questionnaires, which may have been evident in the present study, is the inability to determine the extent to which responses accurately reflect the respondents' experiences and expectations of their PBL tutorial sessions. This warrants further research to examine the actual PBL process. It is also possible that medical educators in this study were not representative of PBL educators.

The response rate was low, despite our efforts to maximise it and this means that the findings should be interpreted with caution. Reasons for non-response are not known. Non-respondents to the survey may also be less interested or involved in PBL, and therefore the reported extent of the PBL approach in this study may be higher than in reality.

Regarding forum repliers, this was a convenience sample consisting of only 6 medical educators. The online forum discussions were convenient and provided a transcribed record. Drawbacks to participation in online discussions may be the same as for online education in general, that is, the inability to capture the richness and depth of meaning without visual and verbal clues.

To overcome these methodological limitations we suggest, therefore, randomised experiments which focus on the performance of PBL graduates and non-PBL graduates in the clinical workplace. This may optimise the accuracy of inferences about the PBL approach. Clearly, an important task facing researchers is the identification and control of those factors that may give rise to alternative explanations for the effects of PBL compared to non-PBL methods. Factors such as the educational background of the students, methods of student selection and the learning culture of the institution are all potentially important. In addition perhaps more emphasis should be placed on researching the comparative learning processes that PBL and non-PBL students engage in. For example PBL students engage in considerably more verbal discourse, questioning and reasoning episodes than traditional students. Perhaps this develops additional cognitive and interpersonal skills not necessarily acquired to the same extent by more didactic and teacher-centred learning methods.

The descriptive analysis of this study showed that many participants valued the PBL approach in the practice and training of doctors. However, some medical education scholars held contrasting views upon on the importance of the PBL approach in undergraduate medical education. Among the medical educators surveyed, 38.5% had a neutral experience of PBL as a student-oriented educational approach. This finding is not consistent with the common characteristic of the PBL approach, indicating its student-centred nature [ 19 ]. Although 46.2% of participants valued PBL as a student-oriented approach, the question that comes to mind is why do a group of medical educators feel so uncertain about it? Further research should examine this. What is surprising is that more than 61% of medical educators disagreed that the facilitator needs to be an expert in the subject matter of the case despite the fact that the majority of participants had a medical health professional qualification. The issue of content knowledge compared to process expertise is still challenging. Some evidence shows differences in favour of content experts when compared with process expertise [ 20 ]. For example, Eagle et al . concluded that twice as many learning issues were identified by groups led by content experts [ 21 ]. Consistent with the results of these studies, Schmidt et al concluded that students guided by subject experts spent more time on self-directed learning and achieved somewhat better scores on high stakes tests than students guided by non-expert facilitators [ 22 ]. However, a study by Silver and Wilkerson indicated that content expertise resulted in more tutor-directed discussion in a PBL course [ 23 ]. Taken together, these studies may suggest that both subject and process expertise are required by facilitators.

The results of this study indicate that the participants had a neutral view of the efficiency of traditional learning compared to a PBL tutorial. As such, participants had a neutral view of the claim that knowledge is better acquired in PBL-based course rather than a lecture-based one. These findings add to most previous research studies by demonstrating that there is no difference between the knowledge that PBL students and non-PBL students acquire about medical sciences [ 24 ]. Although studies show that group learning in PBL may have positive effects, much more empirical evidence is needed to obtain deeper insight into the productive group learning of a PBL tutorial [ 25 ]. One may argue that the process of PBL needs to be rigorously investigated in order to offer reasons for believing that it is designed to help student construct an extensive knowledge base and to become doctors dedicated to lifelong-learning. It is therefore important to further explore the nature of the learning acquired from PBL courses compared to traditional instruction courses.

With respect to graduate entry PBL, this study did not show that the policy of admitting graduates versus school-leavers to medical programmes was perceived as effective in creating better doctors. Interestingly, no previous PBL studies have explored differences between graduate entry PBL and school leaver programmes, although this study revealed that graduate entry PBL is not perceived as a more effective way of increasing the number of doctors in the UK by the majority of responders. In addition, this study revealed that there was a majority perception that graduate entry PBL will produce doctors who have come from a greater variety of educational backgrounds. However, will graduate entry PBL create better doctors compared to school leaver programmes? Sophisticated methodological approaches are required to answer this question.

The descriptions of medical educators about the PBL approach focused on the process of PBL, the characteristics of a good PBL facilitator and the advantages and disadvantages of PBL. It has been well documented that the facilitator role is central to PBL. The adoption of the role requires an understanding of epistemological and ontological issues about teaching and learning in medicine. In the epistemological sense PBL students are novices and the knowledge facilitator should assist them in restructuring new knowledge based on their prior declarative and procedural knowledge. In the ontological sense perceiving a new reality by students is important and the role of the facilitator is to assist students to explore reality in different ways. As the importance of faculty development in PBL was valued by participants in the forum discussion this may suggest more facilitator development workshops to help achieve competence as skilled facilitators of the PBL process. Such workshops may uncover conflicting roles of tutors in the steps of the PBL process. As Irby indicated, identifying and practicing these roles (mediator, challenger, negotiator, director, evaluator and listener) is a key skill of effective facilitation [ 26 ].

In addition to this, one medical educator had a negative approach about PBL, and reflected: " PBL is still unclear in GEM ". It seems that some medical educators have negative perceptions of the ontological assumptions of PBL. For instance, a qualitative study was conducted to explore how a cohort of tutors made sense of PBL. In this study, one participant stated: " absolutely not, no views not really changed at all. I'm still not convinced that PBL, despite the fact that [I will tutor again] is the proper way of teaching" [ 27 ]. Altogether these findings concerning academic achievement are slightly in favour of non-PBL programmes.

When asked about their experience in a PBL tutorial course, medical educators indicated they had few negative feelings with respect to facilitating self-directed learning and student learning. There are several possible reasons for this. Firstly, in the beginning of the course, it seems that the students find adopting a self-directed problem-based approach to learning difficult as they "do not know what they do not know". This may be attributed to the fact that students may have a restricted personal knowledge of the complexity of the "case". Secondly, students may not have clear objectives for the behaviour that they have to achieve, particularly in clinical settings, as mentioned by one participant. Thirdly, learning styles, both deep, surface and 'strategic', are determined at secondary school, and it is also difficult to influence learning styles even with a PBL curriculum [ 28 , 29 ].

In this study, a few participants suggested combinations of pedagogical strategies, where several PBL courses are offered along with courses presented in a more traditional way. There is no evidence that indicates how a hybrid curriculum can make students better doctors compared to other approaches. However, a recent study concluded that changing curricula in medical education reform is not likely to have an impact in improvement in student achievement [ 17 ]. The authors suggested that further work ought to focus on student characteristics and teacher characteristics such as teaching competency.

Whilst many participants valued the importance of the PBL approach in the practice and training of doctors and agreed with most of the conventional descriptions of PBL, some participants held contrasting views upon the importance of the PBL approach in undergraduate medical education. For example, most participants had a neutral view of the efficiency of lecture-based learning compared to a PBL tutorial. However there was a strong view concerning the importance of facilitator training. We need to understand the process of PBL better.

Albanese MA, Mitchell S: Problem-based learning: a review of literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Acad Med. 1993, 68 (1): 52-81. 10.1097/00001888-199301000-00012.

Article Google Scholar

Vernon DT, Blake RL: Does problem-based learning work? A meta-analysis of evaluative research. Acad Med. 1993, 68 (7): 550-563. 10.1097/00001888-199307000-00015.

Berkson L: Problem-based learning: have the expectations been met?. Acad Med. 1993, 68 (10 Suppl): S79-88.

Wolf FM: Problem-based learning and meta-analysis: can we see the forest through the trees?. Acad Med. 1993, 68 (7): 542-544. 10.1097/00001888-199307000-00007.

Albert M, Hodges B, Regehr G: Research in medical education: Balancing services and science. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2006, 12: 103-115. 10.1007/s10459-006-9026-2.

Colliver JA: The reputation of medical education research: Quasi-experimentation and unsolved threats to validity. Teach Learn Med. 2008, 20: 101-103. 10.1080/10401330801989497.

Colliver JA, Markwell SJ: Research on problem-based learning: the need for critical analysis of methods and findings. Med Edu. 2007, 41: 533-535. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02762.x.

Watson R: Scientific methods are the only credible way forward for nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003, 43: 219-220. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02354.x.

Google Scholar

Colliver JA, Robbs SR: Evaluating the effectiveness of major educational interventions. Acad Med. 1999, 74: 859-860.

Barrows HS: Problem-based learning in medicine and byond. Bringing problem-based learning to higher education: Theory and practice. Edited by: Wilkerson L, Gijselaers WH. 1996, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Rideout E, Carpio B: The problem-based learning model of nursing education. Transformaing nursing education through problem-based learning. Edited by: Rideout E. 2001, Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers

Loyens SM, Rikers RM, Schmidt HG: Students' conceptions of constructivist learning: a comparison between a traditional and a problem-based learning curriculum. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2006, 11 (4): 365-379. 10.1007/s10459-006-9015-5.

Colliver JA: Constructivism: The view of knowledge that ended philosophy or a theory of learning and instruction. Teach Learn Med. 2002, 14: 49-51. 10.1207/S15328015TLM1401_11.

Macnee C, McCabe S: Understanding nursing research. 2008, London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Distlehorst LH, Dawson E, Robbs RS, Barrows HS: Problem-based learning outcomes: the glass half-full. Acad Med. 2005, 80 (3): 294-299. 10.1097/00001888-200503000-00020.

Shanley PF: Viewpoint: leaving the "empty glass" of problem-based learning behind: new assumptions and a revised model for case study in preclinical medical education. Acad Med. 2007, 82 (5): 479-485. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803eac4c.

Hecker K, Violato C: How much do differences in medical schools influnce student performance? A longitudinal study employing hierarchical linear modeling. Teach Learn Med. 2008, 20: 104-113. 10.1080/10401330801991915.

Wood DF: Problem-based learning. BMJ. 2008, 336: 971-10.1136/bmj.39546.716053.80.

Glasgow N: New curriculum for new times: A guide to student centred, problem-based learning. 1997, Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press

Davis WK, Narin R, Paine ME, Andrson RM, OH MS: Effects of expert and non-expert facilitators on the small-group process and on student performance. Acad Med. 1992, 67: 4780-4774. 10.1097/00001888-199207000-00013.

Eagle CJ, Harasym PH, Mandin H: Effects of tutors with case expertise on problem-based learning issues. Acad Med. 1992, 67 (7): 465-469. 10.1097/00001888-199207000-00012.

Schmidt HG, Arend van der A, Moust JH, Kokx I, Boon L: Influence of tutors' subject-matter expertise on student effort and achievement in problem-based learning. Acad Med. 1993, 68 (10): 784-791. 10.1097/00001888-199310000-00018.

Silver M, Wilkerson L: Effects of tutors with subject expertise on student effort and achievement in problem-based learning. Acad Med. 1991, 68: 748-791.

Major CH, Palmer B: Assessing the effectiveness of problem-based learning in higher education: Lessons from the literature. Academic exchange quarterly. 2001, 5: 134-140.

Dolmans DH, Schmidt HG: What do we know about cognitive and motivational effects of small group tutorials in problem-based learning?. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2006, 11 (4): 321-336. 10.1007/s10459-006-9012-8.

Irby DM: Models of faculty development for problem-based learning. Advances in health sciences. 1996, 1: 69-81. 10.1007/BF00596230.

Maudsley G: Making sense of trying not to teach: an interview study of tutors' ideas of problem-based learning. Acad Med. 2002, 77 (2): 162-172. 10.1097/00001888-200202000-00017.

Carter YH, Peile E: Graduated entry medicine: Curriculum considerations. Clinical Medicine. 2007, 7: 253-256.

Reid WA, Duvall E, Evans P: Can we influence medical students' approach to learning. Med Teach. 2005, 27: 401-407. 10.1080/01421590500136410.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/9/66/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the medical educators who participated in this study. Thanks also to the two reviewers whose comments allowed us to improve on our previous draft.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Medical Education Unit, The University of Nottingham, Queen's Medical Centre, UK

Mohsen Tavakol & Reg Dennick

School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Nottingham, Queen's Medical Centre, UK

Sina Tavakol

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohsen Tavakol .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. MT, RD and ST contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. MT and RD contributed to drafting of the paper. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the paper and approved the final paper for publication.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: the study instrument. (doc 37 kb), rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tavakol, M., Dennick, R. & Tavakol, S. A descriptive study of medical educators' views of problem-based learning. BMC Med Educ 9 , 66 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-66

Download citation

Received : 28 May 2009

Accepted : 04 November 2009

Published : 04 November 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-66

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical Educator

- Undergraduate Medical Education

- Neutral View

- Conventional Curriculum

- Medical Education Reform

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

For Julie Greenberg, a career of research, mentoring, and advocacy

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

For Julie E. Greenberg SM ’89, PhD ’94, what began with a middle-of-the-night phone call from overseas became a gratifying career of study, research, mentoring, advocacy, and guiding of the office of a unique program with a mission to educate the next generation of clinician-scientists and engineers.

In 1987, Greenberg was a computer engineering graduate of the University of Michigan, living in Tel Aviv, Israel, where she was working for Motorola — when she answered an early-morning call from Roger Mark , then the director of the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology (HST). A native of Detroit, Michigan, Greenberg had just been accepted into MIT’s electrical engineering and computer science (EECS) graduate program.

HST — one of the world’s oldest interdisciplinary educational programs based on translational medical science and engineering — had been offering the medical engineering and medical physics (MEMP) PhD program since 1978, but it was then still relatively unknown. Mark, an MIT distinguished professor of health sciences and technology and of EECS, and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, was calling to ask Greenberg if she might be interested in enrolling in HST’s MEMP program.

“At the time, I had applied to MIT not knowing that HST existed,” Greenberg recalls. “So, I was groggily answering the phone in the middle of the night and trying to be quiet, because my roommate was a co-worker at Motorola, and no one yet knew that I was planning to leave to go to grad school. Roger asked if I’d like to be considered for HST, but he also suggested that I could come to EECS in the fall, learn more about HST, and then apply the following year. That was the option I chose.”

For Greenberg, who retired March 15 from her role as senior lecturer and director of education — that early morning phone call was the first she would hear of the program where she would eventually spend the bulk of her 37-year career at MIT, first as a student, then as the director of HST’s academic office. During her first year as a graduate student, she enrolled in class HST.582/6.555 (Biomedical Signal and Image Processing), for which she later served as lecturer and eventually course director, teaching the class almost every year for three decades. But as a first-year graduate student, she says she found that “all the cool kids” were HST students. “It was a small class, so we all got to know each other,” Greenberg remembers. “EECS was a big program. The MEMP students were a tight, close-knit community, so in addition to my desire to work on biomedical applications, that made HST very appealing.”

Also piquing her interest in HST was meeting Martha L. Gray, the Whitaker Professor in Biomedical Engineering. Gray, who is also a professor of EECS and a core faculty member of the MIT Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES), was then a new member of the EECS faculty, and Greenberg met her at an orientation event for graduate student women, who were a smaller cohort then, compared to now. Gray SM ’81, PhD ’86 became Greenberg’s academic advisor when she joined HST. Greenberg’s SM and PhD research was on signal processing for hearing aids, in what was then the Sensory Communication Group in MIT’s Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE).

Gray later succeeded Mark as director of HST at MIT, and it was she who recruited Greenberg to join as HST director of education in 2004, after Greenberg had spent a decade as a researcher in RLE.

“Julie is amazing — one of my best decisions as HST director was to hire Julie. She is an exceptionally clear thinker, a superb collaborator, and wicked smart,” Gray says. “One of her superpowers is being able to take something that is incredibly complex and to break it down into logical chunks … And she is absolutely devoted to advocating for the students. She is no pushover, but she has a way of coming up with solutions to what look like unfixable problems, before they become even bigger.”

Greenberg’s experience as an HST graduate student herself has informed her leadership, giving her a unique perspective on the challenges for those who are studying and researching in a demanding program that flows between two powerful institutions. HST students have full access to classes and all academic and other opportunities at both MIT and Harvard University, while having a primary institution for administrative purposes, and ultimately to award their degree. HST’s home at Harvard is in the London Society at Harvard Medical School, while at MIT, it is IMES.

In looking back on her career in HST, Greenberg says the overarching theme is one of “doing everything possible to smooth the path. So that students can get to where they need to go, and learn what they need to learn, and do what they need to do, rather than getting caught up in the bureaucratic obstacles of maneuvering between institutions. Having been through it myself gives me a good sense of how to empower the students.”

Rachel Frances Bellisle, an HST MEMP student who is graduating in May and is studying bioastronautics, says that having Julie as her academic advisor was invaluable because of her eagerness to solve the thorniest of issues. “Whenever I was trying to navigate something and was having trouble finding a solution, Julie was someone I could always turn to,” she says. “I know many graduate students in other programs who haven’t had the important benefit of that sort of individualized support. She’s always had my back.”

And Xining Gao, a fourth-year MEMP student studying biological engineering, says that as a student who started during the Covid pandemic, having someone like Greenberg and the others in the HST academic office — who worked to overcome the challenges of interacting mostly over Zoom — made a crucial difference. “A lot of us who joined in 2020 felt pretty disconnected,” Gao says. “Julie being our touchstone and guide in the absence of face-to-face interactions was so key.” The pandemic challenges inspired Gao to take on student government positions, including as PhD co-chair of the HST Joint Council. “Working with Julie, I’ve seen firsthand how committed she is to our department,” Gao says. “She is truly a cornerstone of the HST community.”

During her time at MIT, Greenberg has been involved in many Institute-level initiatives, including as a member of the 2016 class of the Leader to Leader program. She lauded L2L as being “transformative” to her professional development, saying that there have been “countless occasions where I’ve been able to solve a problem quickly and efficiently by reaching out to a fellow L2L alum in another part of the Institute.”

Since Greenberg started leading HST operations, the program has steadily evolved. When Greenberg was a student, the MEMP class was relatively small, admitting 10 students annually, with roughly 30 percent of them being women. Now, approximately 20 new MEMP PhD students and 30 new MD or MD-PhD students join the HST community each year, and half of them are women. Since 2004, the average time-to-degree for HST MEMP PhD students dropped by almost a full year, and is now on par with the average for all graduate programs in MIT’s School of Engineering, despite the complications of taking classes at both Harvard and MIT.

A search is underway for Julie’s replacement. But in the meantime, those who have worked with her praise her impact on HST, and on MIT.

“Throughout the entire history of the HST ecosystem, you cannot find anyone who cares more about HST students than Julie,” says Collin Stultz, the Nina T. and Robert H. Rubin Professor in Medical Engineering and Science, and professor of EECS. Stultz is also the co-director of HST, as well as a 1997 HST MD graduate. “She is, and has always been, a formidable advocate for HST students and an oracle of information to me.”

Elazer Edelman ’78, SM ’79, PhD ’84, the Edward J. Poitras Professor in Medical Engineering and Science and director of IMES, says that Greenberg “has been a mentor to generations of students and leaders — she is a force of nature whose passion for learning and teaching is matched by love for our people and the spirit of our institutions. Her name is synonymous with many of our most innovative educational initiatives; indeed, she has touched every aspect of HST and IMES this very many decades. It is hard to imagine academic life here without her guiding hand.”

Greenberg says she is looking forward to spending more time on her hobbies, including baking, gardening, and travel, and that she may investigate getting involved in some way with working with STEM and underserved communities. She describes leaving now as “bittersweet. But I think that HST is in a strong, secure position, and I’m excited to see what will happen next, but from further away … and as long as they keep inviting alumni to the HST dinners, I will come.”

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Julie Greenberg

- Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology

- Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES)

- Research Laboratory of Electronics

Related Topics

- Biological engineering

- Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology

- Electrical Engineering & Computer Science (eecs)

Related Articles

A passion for innovation and education

Annie Liau: Infinite caring for the MIT community

Edward Crawley: A career of education, service, and exploration

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

Reevaluating an approach to functional brain imaging

Read full story →

Propelling atomically layered magnets toward green computers

Q&A: Tips for viewing the 2024 solar eclipse

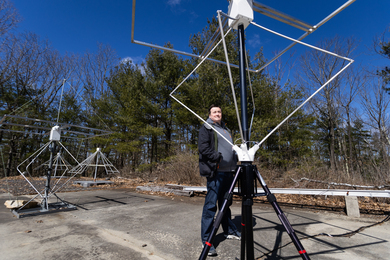

MIT Haystack scientists prepare a constellation of instruments to observe the solar eclipse’s effects

Drinking from a firehose — on stage

Researchers 3D print key components for a point-of-care mass spectrometer

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

This paper is in the following e-collection/theme issue:

Published on 3.4.2024 in Vol 26 (2024)

Public Discourse, User Reactions, and Conspiracy Theories on the X Platform About HIV Vaccines: Data Mining and Content Analysis

Authors of this article:

Original Paper

- Jueman M Zhang 1 , PhD ;

- Yi Wang 2 , PhD ;

- Magali Mouton 3 ;

- Jixuan Zhang 4 ;

- Molu Shi 5 , PhD

1 Harrington School of Communication and Media, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, United States

2 Department of Communication, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, United States

3 School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

4 Polk School of Communications, Long Island University, Brooklyn, NY, United States

5 College of Business, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, United States

Corresponding Author:

Jueman M Zhang, PhD

Harrington School of Communication and Media

University of Rhode Island

10 Ranger Road

Kingston, RI, 02881

United States

Phone: 1 401 874 2110

Email: [email protected]

Background: The initiation of clinical trials for messenger RNA (mRNA) HIV vaccines in early 2022 revived public discussion on HIV vaccines after 3 decades of unsuccessful research. These trials followed the success of mRNA technology in COVID-19 vaccines but unfolded amid intense vaccine debates during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is crucial to gain insights into public discourse and reactions about potential new vaccines, and social media platforms such as X (formerly known as Twitter) provide important channels.

Objective: Drawing from infodemiology and infoveillance research, this study investigated the patterns of public discourse and message-level drivers of user reactions on X regarding HIV vaccines by analyzing posts using machine learning algorithms. We examined how users used different post types to contribute to topics and valence and how these topics and valence influenced like and repost counts. In addition, the study identified salient aspects of HIV vaccines related to COVID-19 and prominent anti–HIV vaccine conspiracy theories through manual coding.

Methods: We collected 36,424 English-language original posts about HIV vaccines on the X platform from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022. We used topic modeling and sentiment analysis to uncover latent topics and valence, which were subsequently analyzed across post types in cross-tabulation analyses and integrated into linear regression models to predict user reactions, specifically likes and reposts. Furthermore, we manually coded the 1000 most engaged posts about HIV and COVID-19 to uncover salient aspects of HIV vaccines related to COVID-19 and the 1000 most engaged negative posts to identify prominent anti–HIV vaccine conspiracy theories.

Results: Topic modeling revealed 3 topics: HIV and COVID-19, mRNA HIV vaccine trials, and HIV vaccine and immunity. HIV and COVID-19 underscored the connections between HIV vaccines and COVID-19 vaccines, as evidenced by subtopics about their reciprocal impact on development and various comparisons. The overall valence of the posts was marginally positive. Compared to self-composed posts initiating new conversations, there was a higher proportion of HIV and COVID-19–related and negative posts among quote posts and replies, which contribute to existing conversations. The topic of mRNA HIV vaccine trials, most evident in self-composed posts, increased repost counts. Positive valence increased like and repost counts. Prominent anti–HIV vaccine conspiracy theories often falsely linked HIV vaccines to concurrent COVID-19 and other HIV-related events.

Conclusions: The results highlight COVID-19 as a significant context for public discourse and reactions regarding HIV vaccines from both positive and negative perspectives. The success of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines shed a positive light on HIV vaccines. However, COVID-19 also situated HIV vaccines in a negative context, as observed in some anti–HIV vaccine conspiracy theories misleadingly connecting HIV vaccines with COVID-19. These findings have implications for public health communication strategies concerning HIV vaccines.

Introduction

Vaccination has long been recognized as a crucial preventive measure against diseases and infections, but opposition to vaccines has endured [ 1 ]. HIV vaccination has been regarded as a potential preventive measure to help combat the HIV epidemic in the United States, with research and progress dating back to the mid-1980s but without success thus far [ 2 ]. An estimated 1.2 million people were living with HIV in the United States by the end of 2021, with 36,136 new HIV diagnoses reported in 2021 [ 3 ].